User login

Plant-based foods could keep type 2 diabetes at bay

according to a new systematic review and meta-analysis of nine observational studies.

The findings aren’t conclusive, but the study authors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine that they suggest that “plant-based dietary patterns were associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, even after adjustment for [body mass index].”

According to 2015 figures provided by the American Diabetes Association, about 29 million people in the United States have type 2 diabetes. Overall, diabetes contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, which makes it the seventh-leading cause of death in the nation.

For the new analysis, researchers led by Frank Qian, MPH, of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health included nine studies that examined diet and type 2 diabetes. In all, the studies included 307,099 participants, and there were 23,544 cases of incident type 2 diabetes. They were conducted in five countries, including the United States, and tracked participants for 2-28 years; the studies were all published within the last 11 years. The mean ages of participants ranged from 36-65 years.

The meta-analysis linked higher consumption of plant-based foods to a 23% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with lower consumption (relative risk, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.84; P = .07 for heterogeneity). The risk dipped even further (down to 30%) when the researchers analyzed four studies that focused on healthy plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables, instead of foods such as refined grains, starches, and sugars (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62-0.79).

The researchers suggested that plant-based diets may lower the risk of diabetes type 2 by limiting weight gain. They also noted various limitations to their analysis, such as the reliance on self-reports and the observational nature of the studies.

Still, “in general populations that do not practice strict vegetarian or vegan diets, replacing animal products with healthful plant-based foods is likely to exert a significant reduction in the risk of diabetes,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and one author received support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest withing the scope of this study.

SOURCE: Qian F et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2195.

according to a new systematic review and meta-analysis of nine observational studies.

The findings aren’t conclusive, but the study authors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine that they suggest that “plant-based dietary patterns were associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, even after adjustment for [body mass index].”

According to 2015 figures provided by the American Diabetes Association, about 29 million people in the United States have type 2 diabetes. Overall, diabetes contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, which makes it the seventh-leading cause of death in the nation.

For the new analysis, researchers led by Frank Qian, MPH, of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health included nine studies that examined diet and type 2 diabetes. In all, the studies included 307,099 participants, and there were 23,544 cases of incident type 2 diabetes. They were conducted in five countries, including the United States, and tracked participants for 2-28 years; the studies were all published within the last 11 years. The mean ages of participants ranged from 36-65 years.

The meta-analysis linked higher consumption of plant-based foods to a 23% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with lower consumption (relative risk, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.84; P = .07 for heterogeneity). The risk dipped even further (down to 30%) when the researchers analyzed four studies that focused on healthy plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables, instead of foods such as refined grains, starches, and sugars (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62-0.79).

The researchers suggested that plant-based diets may lower the risk of diabetes type 2 by limiting weight gain. They also noted various limitations to their analysis, such as the reliance on self-reports and the observational nature of the studies.

Still, “in general populations that do not practice strict vegetarian or vegan diets, replacing animal products with healthful plant-based foods is likely to exert a significant reduction in the risk of diabetes,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and one author received support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest withing the scope of this study.

SOURCE: Qian F et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2195.

according to a new systematic review and meta-analysis of nine observational studies.

The findings aren’t conclusive, but the study authors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine that they suggest that “plant-based dietary patterns were associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, even after adjustment for [body mass index].”

According to 2015 figures provided by the American Diabetes Association, about 29 million people in the United States have type 2 diabetes. Overall, diabetes contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, which makes it the seventh-leading cause of death in the nation.

For the new analysis, researchers led by Frank Qian, MPH, of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health included nine studies that examined diet and type 2 diabetes. In all, the studies included 307,099 participants, and there were 23,544 cases of incident type 2 diabetes. They were conducted in five countries, including the United States, and tracked participants for 2-28 years; the studies were all published within the last 11 years. The mean ages of participants ranged from 36-65 years.

The meta-analysis linked higher consumption of plant-based foods to a 23% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with lower consumption (relative risk, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.84; P = .07 for heterogeneity). The risk dipped even further (down to 30%) when the researchers analyzed four studies that focused on healthy plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables, instead of foods such as refined grains, starches, and sugars (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62-0.79).

The researchers suggested that plant-based diets may lower the risk of diabetes type 2 by limiting weight gain. They also noted various limitations to their analysis, such as the reliance on self-reports and the observational nature of the studies.

Still, “in general populations that do not practice strict vegetarian or vegan diets, replacing animal products with healthful plant-based foods is likely to exert a significant reduction in the risk of diabetes,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and one author received support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest withing the scope of this study.

SOURCE: Qian F et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2195.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

FDA declines dapagliflozin indication as adjunct for type 1 diabetes

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected AstraZeneca’s supplemental New Drug Application for the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) as an adjunct treatment to insulin in adult patients with type 1 diabetes.

The company said in a press statement that the FDA had issued a complete response letter regarding the application. No reason was given for the decision, but the company said it would work with the agency to discuss the next steps.

The once-daily therapy has been approved as both a monotherapy and combination therapy, as an adjunct to diet and exercise, for improving glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes who cannot achieve control with insulin alone. It also has additional demonstrated benefits of weight loss and reduction in blood pressure.

On March 25, 2019, the drug received its first approval for treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes when the European Commission gave it the green light for use in patients with a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or more when insulin alone does not provide adequate glycemic control. Japan followed a few days later with its approval of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, also for type 1 disease in adults.

The approvals for type 1 diabetes in the European Union and Japan were based on data from the phase 3 DEPICT (Dapagliflozin Evaluation in Patients With Inadequately Controlled Type 1 Diabetes) trial program (DEPICT-1 and DEPICT-2), which showed that 5 mg dapagliflozin, taken daily as an oral adjunct to insulin in patients with hard-to-control type 1 disease, reduced blood glucose levels from baseline (the primary endpoint). Secondary endpoints – reductions in weight and total daily insulin use – were also achieved.

Dapagliflozin’s safety profile in the trials in patients with type 1 diabetes was consistent with that established in patients with type 2 disease. However, there was a higher number of cases of diabetic ketoacidosis events in patients who received dapagliflozin. Diabetic ketoacidosis is a known complication for adults with type 1 diabetes and is more prevalent in patients with type 1 disease than in those with type 2.

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected AstraZeneca’s supplemental New Drug Application for the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) as an adjunct treatment to insulin in adult patients with type 1 diabetes.

The company said in a press statement that the FDA had issued a complete response letter regarding the application. No reason was given for the decision, but the company said it would work with the agency to discuss the next steps.

The once-daily therapy has been approved as both a monotherapy and combination therapy, as an adjunct to diet and exercise, for improving glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes who cannot achieve control with insulin alone. It also has additional demonstrated benefits of weight loss and reduction in blood pressure.

On March 25, 2019, the drug received its first approval for treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes when the European Commission gave it the green light for use in patients with a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or more when insulin alone does not provide adequate glycemic control. Japan followed a few days later with its approval of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, also for type 1 disease in adults.

The approvals for type 1 diabetes in the European Union and Japan were based on data from the phase 3 DEPICT (Dapagliflozin Evaluation in Patients With Inadequately Controlled Type 1 Diabetes) trial program (DEPICT-1 and DEPICT-2), which showed that 5 mg dapagliflozin, taken daily as an oral adjunct to insulin in patients with hard-to-control type 1 disease, reduced blood glucose levels from baseline (the primary endpoint). Secondary endpoints – reductions in weight and total daily insulin use – were also achieved.

Dapagliflozin’s safety profile in the trials in patients with type 1 diabetes was consistent with that established in patients with type 2 disease. However, there was a higher number of cases of diabetic ketoacidosis events in patients who received dapagliflozin. Diabetic ketoacidosis is a known complication for adults with type 1 diabetes and is more prevalent in patients with type 1 disease than in those with type 2.

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected AstraZeneca’s supplemental New Drug Application for the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) as an adjunct treatment to insulin in adult patients with type 1 diabetes.

The company said in a press statement that the FDA had issued a complete response letter regarding the application. No reason was given for the decision, but the company said it would work with the agency to discuss the next steps.

The once-daily therapy has been approved as both a monotherapy and combination therapy, as an adjunct to diet and exercise, for improving glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes who cannot achieve control with insulin alone. It also has additional demonstrated benefits of weight loss and reduction in blood pressure.

On March 25, 2019, the drug received its first approval for treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes when the European Commission gave it the green light for use in patients with a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or more when insulin alone does not provide adequate glycemic control. Japan followed a few days later with its approval of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, also for type 1 disease in adults.

The approvals for type 1 diabetes in the European Union and Japan were based on data from the phase 3 DEPICT (Dapagliflozin Evaluation in Patients With Inadequately Controlled Type 1 Diabetes) trial program (DEPICT-1 and DEPICT-2), which showed that 5 mg dapagliflozin, taken daily as an oral adjunct to insulin in patients with hard-to-control type 1 disease, reduced blood glucose levels from baseline (the primary endpoint). Secondary endpoints – reductions in weight and total daily insulin use – were also achieved.

Dapagliflozin’s safety profile in the trials in patients with type 1 diabetes was consistent with that established in patients with type 2 disease. However, there was a higher number of cases of diabetic ketoacidosis events in patients who received dapagliflozin. Diabetic ketoacidosis is a known complication for adults with type 1 diabetes and is more prevalent in patients with type 1 disease than in those with type 2.

CARMELINA confirms linagliptin’s renal, CV safety, but it’s still third-line for type 2 diabetes

SAN FRANCISCO – The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin (Tradjenta) is safe on the kidneys, the cardiovascular system, and in older people with type 2 diabetes, according to findings presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Investigators in the international Cardiovascular and Renal Microvascular Outcome Study with Linagliptin (CARMELINA) randomized 6,979 patients with type 2 diabetes who also had cardiovascular and/or kidney disease 1:1 to daily oral linagliptin 5 mg or placebo on top of standard of care, and they followed them for a median of 2.2 years. The mean age was 65.9 years, baseline hemoglobin A1c was 8.0%, and disease duration was about 15 years. Almost 63% of the patients were men, and about a quarter had a history of heart failure at baseline (JAMA. 2019;321[1]:69-79).

The study was unusual among other DPP-4 trials in that almost 60% of the patients were older than 65 years and 62.3% had impaired renal function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

There was no increased risk with linagliptin, compared with placebo, in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal myocardial infarction (12.4% vs. 12.1%, respectively; hazard ratio, 1.02; P = .74), and there was no difference between the individual components even when broken down by age (younger than 65, 65-75, or older than 75 years) or by renal function (eGFR 60 or more, 45 to less than 60, 30 to less than 45, or less than 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), according to investigator Mark Cooper, MBBS, PhD, of the department of diabetes at Monash University, Melbourne, who presented the findings.

There was no increase in the number of hospitalizations for heart failure with linagliptin, compared with placebo (6% vs. 6.5%, respectively; HR, 0.90; P = .26) – a concern with some DPP-4 inhibitors – and no increase in hypoglycemia (just over a quarter in both groups), even when broken down by age and renal function.

A decrease in albuminuria with linagliptin held across all renal subgroups. It is not known if that was because of glucose lowering or some other effect, but Dr. Cooper said he believed there was “a modest renal protective effect, [although] not at the level one would expect to translate into hard renal outcomes.”

Robert Eckel, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who moderated the session, said the results were reassuring. “Ultimately, linagliptin seems safe,” even in older people with reduced eGFR. “It does not improve cardiovascular outcomes, but based on many DPP-4 trials, we didn’t expect it to,” he said.

“I don’t think DPP-4s are going to fall into any different place in the [treatment] algorithm” based on these results, he added. The class is currently third-line after metformin or insulin, followed by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists for cardiovascular protection.

“When we look at [cardiovascular outcomes], ultimately, the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 receptor agonists win,” he said. In addition, the blood glucose effects of linagliptin are “pretty modest, so if lowering hemoglobin A1c is the focus, this drug would be lower down on the list.”

Overall, linagliptin “falls into a lesser class, but a safe class for certain circumstances,” said Dr. Eckel, who gave the example of a woman in her late 70s with moderate to severe kidney function, an HbA1c level of 7.9%, and no cardiovascular disease. Her HbA1c might get down to 7.6% or so with linagliptin, he said, “but I’m not sure we have absolute proof of the benefit” of such a modest decline.

Boehringer Ingelheim, the maker of linagliptin, funded the study. The presenter disclosed honoraria, speaking fees, and grants from the company. A number of the investigators were employees of the company.

SAN FRANCISCO – The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin (Tradjenta) is safe on the kidneys, the cardiovascular system, and in older people with type 2 diabetes, according to findings presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Investigators in the international Cardiovascular and Renal Microvascular Outcome Study with Linagliptin (CARMELINA) randomized 6,979 patients with type 2 diabetes who also had cardiovascular and/or kidney disease 1:1 to daily oral linagliptin 5 mg or placebo on top of standard of care, and they followed them for a median of 2.2 years. The mean age was 65.9 years, baseline hemoglobin A1c was 8.0%, and disease duration was about 15 years. Almost 63% of the patients were men, and about a quarter had a history of heart failure at baseline (JAMA. 2019;321[1]:69-79).

The study was unusual among other DPP-4 trials in that almost 60% of the patients were older than 65 years and 62.3% had impaired renal function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

There was no increased risk with linagliptin, compared with placebo, in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal myocardial infarction (12.4% vs. 12.1%, respectively; hazard ratio, 1.02; P = .74), and there was no difference between the individual components even when broken down by age (younger than 65, 65-75, or older than 75 years) or by renal function (eGFR 60 or more, 45 to less than 60, 30 to less than 45, or less than 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), according to investigator Mark Cooper, MBBS, PhD, of the department of diabetes at Monash University, Melbourne, who presented the findings.

There was no increase in the number of hospitalizations for heart failure with linagliptin, compared with placebo (6% vs. 6.5%, respectively; HR, 0.90; P = .26) – a concern with some DPP-4 inhibitors – and no increase in hypoglycemia (just over a quarter in both groups), even when broken down by age and renal function.

A decrease in albuminuria with linagliptin held across all renal subgroups. It is not known if that was because of glucose lowering or some other effect, but Dr. Cooper said he believed there was “a modest renal protective effect, [although] not at the level one would expect to translate into hard renal outcomes.”

Robert Eckel, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who moderated the session, said the results were reassuring. “Ultimately, linagliptin seems safe,” even in older people with reduced eGFR. “It does not improve cardiovascular outcomes, but based on many DPP-4 trials, we didn’t expect it to,” he said.

“I don’t think DPP-4s are going to fall into any different place in the [treatment] algorithm” based on these results, he added. The class is currently third-line after metformin or insulin, followed by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists for cardiovascular protection.

“When we look at [cardiovascular outcomes], ultimately, the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 receptor agonists win,” he said. In addition, the blood glucose effects of linagliptin are “pretty modest, so if lowering hemoglobin A1c is the focus, this drug would be lower down on the list.”

Overall, linagliptin “falls into a lesser class, but a safe class for certain circumstances,” said Dr. Eckel, who gave the example of a woman in her late 70s with moderate to severe kidney function, an HbA1c level of 7.9%, and no cardiovascular disease. Her HbA1c might get down to 7.6% or so with linagliptin, he said, “but I’m not sure we have absolute proof of the benefit” of such a modest decline.

Boehringer Ingelheim, the maker of linagliptin, funded the study. The presenter disclosed honoraria, speaking fees, and grants from the company. A number of the investigators were employees of the company.

SAN FRANCISCO – The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin (Tradjenta) is safe on the kidneys, the cardiovascular system, and in older people with type 2 diabetes, according to findings presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Investigators in the international Cardiovascular and Renal Microvascular Outcome Study with Linagliptin (CARMELINA) randomized 6,979 patients with type 2 diabetes who also had cardiovascular and/or kidney disease 1:1 to daily oral linagliptin 5 mg or placebo on top of standard of care, and they followed them for a median of 2.2 years. The mean age was 65.9 years, baseline hemoglobin A1c was 8.0%, and disease duration was about 15 years. Almost 63% of the patients were men, and about a quarter had a history of heart failure at baseline (JAMA. 2019;321[1]:69-79).

The study was unusual among other DPP-4 trials in that almost 60% of the patients were older than 65 years and 62.3% had impaired renal function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

There was no increased risk with linagliptin, compared with placebo, in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal myocardial infarction (12.4% vs. 12.1%, respectively; hazard ratio, 1.02; P = .74), and there was no difference between the individual components even when broken down by age (younger than 65, 65-75, or older than 75 years) or by renal function (eGFR 60 or more, 45 to less than 60, 30 to less than 45, or less than 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), according to investigator Mark Cooper, MBBS, PhD, of the department of diabetes at Monash University, Melbourne, who presented the findings.

There was no increase in the number of hospitalizations for heart failure with linagliptin, compared with placebo (6% vs. 6.5%, respectively; HR, 0.90; P = .26) – a concern with some DPP-4 inhibitors – and no increase in hypoglycemia (just over a quarter in both groups), even when broken down by age and renal function.

A decrease in albuminuria with linagliptin held across all renal subgroups. It is not known if that was because of glucose lowering or some other effect, but Dr. Cooper said he believed there was “a modest renal protective effect, [although] not at the level one would expect to translate into hard renal outcomes.”

Robert Eckel, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who moderated the session, said the results were reassuring. “Ultimately, linagliptin seems safe,” even in older people with reduced eGFR. “It does not improve cardiovascular outcomes, but based on many DPP-4 trials, we didn’t expect it to,” he said.

“I don’t think DPP-4s are going to fall into any different place in the [treatment] algorithm” based on these results, he added. The class is currently third-line after metformin or insulin, followed by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists for cardiovascular protection.

“When we look at [cardiovascular outcomes], ultimately, the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 receptor agonists win,” he said. In addition, the blood glucose effects of linagliptin are “pretty modest, so if lowering hemoglobin A1c is the focus, this drug would be lower down on the list.”

Overall, linagliptin “falls into a lesser class, but a safe class for certain circumstances,” said Dr. Eckel, who gave the example of a woman in her late 70s with moderate to severe kidney function, an HbA1c level of 7.9%, and no cardiovascular disease. Her HbA1c might get down to 7.6% or so with linagliptin, he said, “but I’m not sure we have absolute proof of the benefit” of such a modest decline.

Boehringer Ingelheim, the maker of linagliptin, funded the study. The presenter disclosed honoraria, speaking fees, and grants from the company. A number of the investigators were employees of the company.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2019

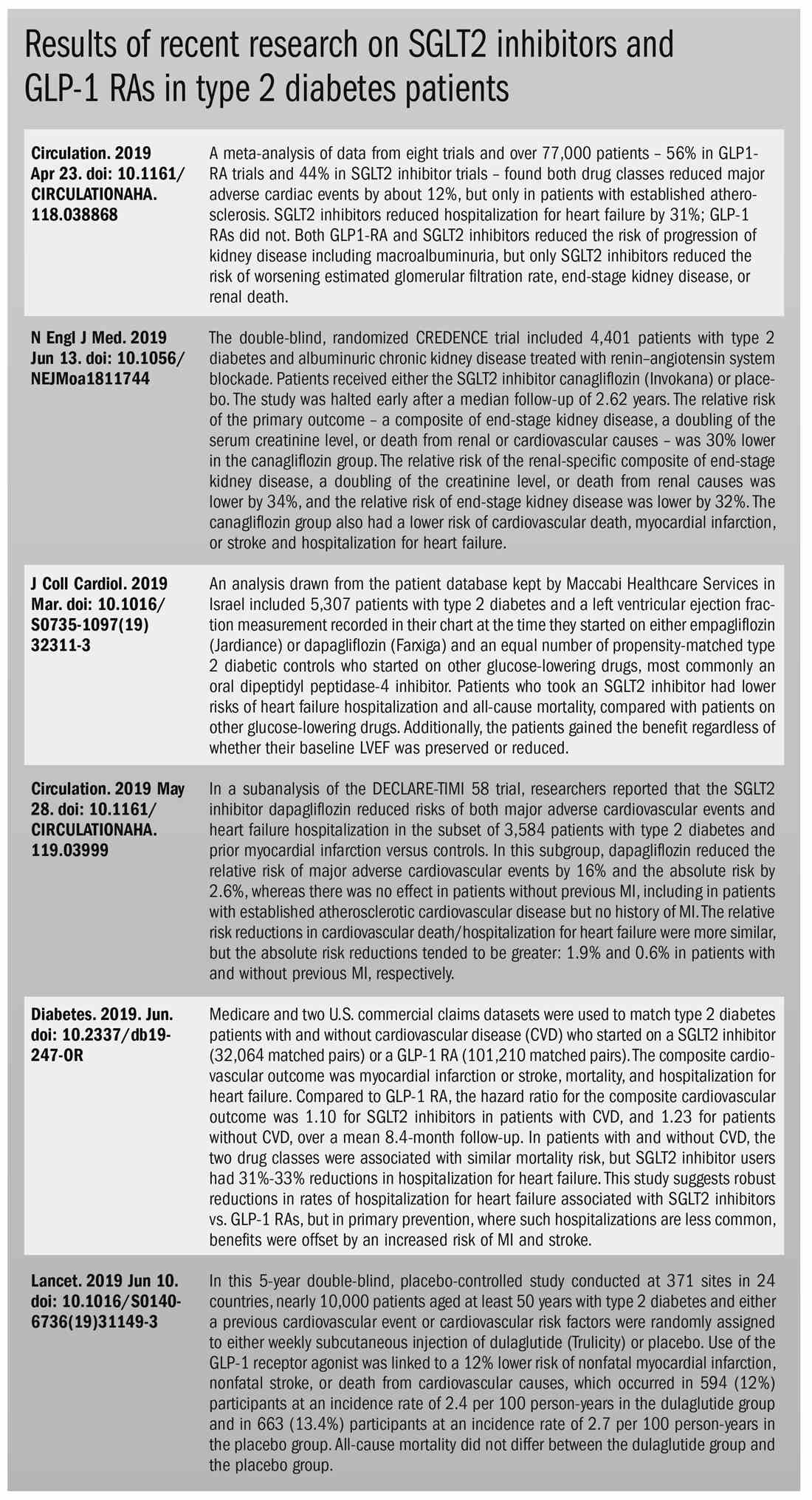

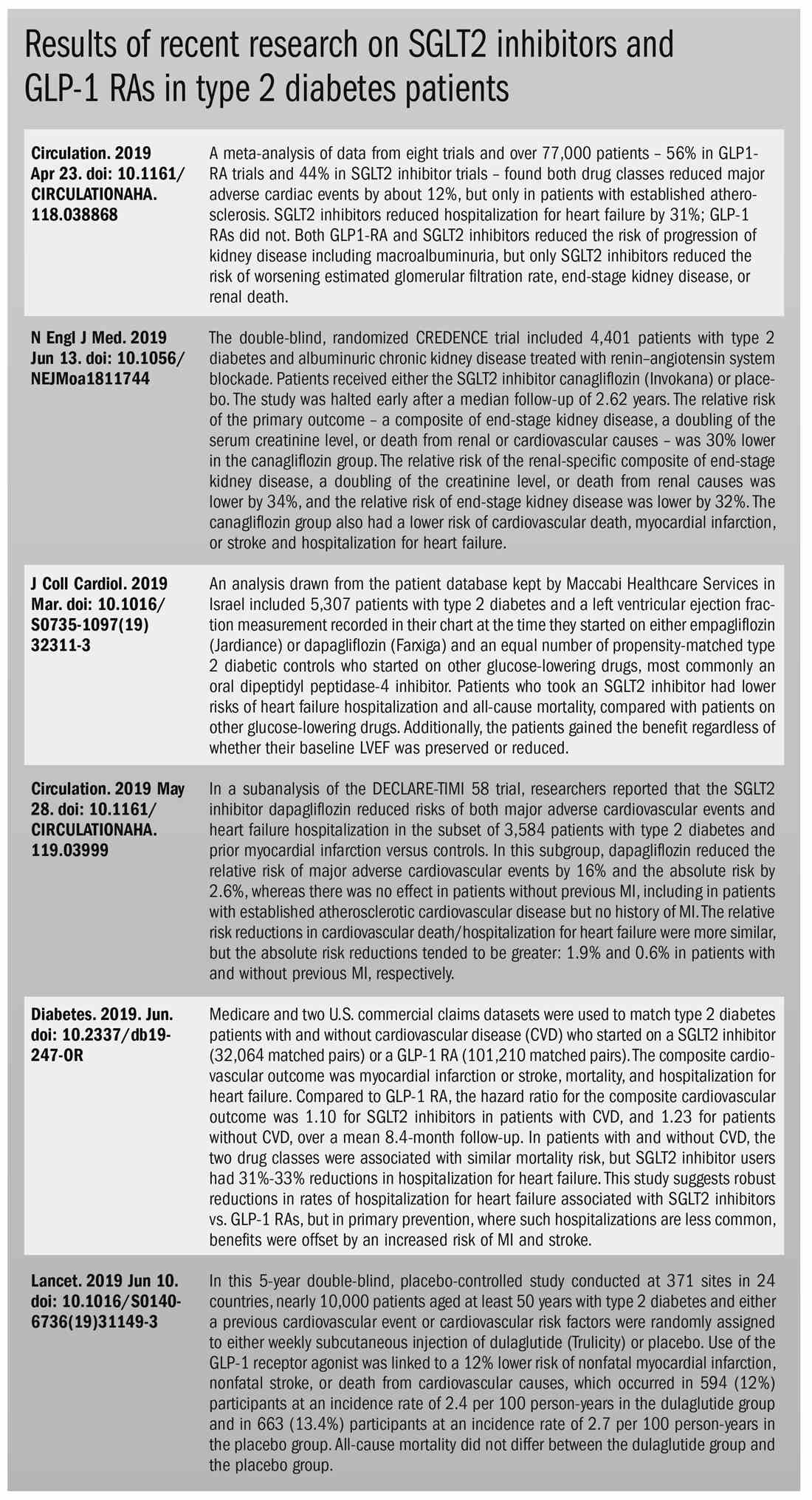

The costs and benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors & GLP-1 RAs

The options for treating type 2 diabetes without insulin have grown beyond metformin to include a long list of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists that can be taken with or without metformin. These new drugs have cardiovascular and kidney benefits and help with weight loss, but they also carry risks and, according to some experts, their costs can be prohibitively expensive.

Given the medical community’s long-term experience with treating patients with metformin, and metformin’s lower cost, most of the physicians interviewed for this article advise using SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists as second-line treatments. Others said that they would prefer to use the newer drugs as first-line therapies in select high-risk patients, but prior authorization hurdles created by insurance companies make that approach too burdensome.

“The economics of U.S. health care is stacked against many of our patients with diabetes in the current era,” Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, said in an interview.

Even when their insurance approves the drugs, patients still may not be able to afford the copay, explained Dr. Hopkins, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and director of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. “Sometimes patients can purchase drugs at a lower cost than the copay to purchase with the ‘drug coverage’ in their insurance plan – unfortunately, this is not the case with the newer diabetes medications we are discussing here.”

“SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists can cost several hundred dollars a month, and insurers often balk at paying for them. They’ll say, ‘Have you tried metformin?’ ” explained endocrinologist Victor Lawrence Roberts, MD, in a interview. “We have to work with insurance companies the best we can in a stepwise fashion.”

According to Dr. Roberts, 80% of his patients with diabetes struggle with the cost of medicine in general. “They’re either underinsured or not insured or their formulary is limited.

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, agreed in an interview that the newer drugs can be problematic on the insurance front.

“For some patients they aren’t affordable, especially for the uninsured if you can’t get them on an assistance program,” said Dr. Paauw, who is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university.

Dr. Hopkins, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted that “unfortunately, the treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients who cannot achieve control with metformin, diet, weight control, and exercise is a story of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ The ‘haves’ are those who have pharmacy benefits which make access to newer agents like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists a possibility.”

“I have had very few of the ‘have nots’ who have been able to even consider these newer agents, which carry price tags of $600-$1,300 a month even with the availability of discounting coupons in the marketplace,” he added. “Most of these patients end up requiring a sulfonylurea or TZD [thiazolidinedione] as a second agent to achieve glycemic control. This makes it very difficult to achieve sufficient weight and metabolic control to avoid an eventual switch to insulin.”

Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an endocrine-trained general internist at DukeHealth in Durham, N.C., said she prescribes SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in combination with metformin. “I prescribe them frequently, but they are not first-line treatments,” she explained.

“Nothing replaces diet and exercise” as therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes, she added.

Neil S. Skolnik, MD, said that insurance companies were not preventing patients from using these drugs in his experience. He also provided an optimistic take on the accessibility of these drugs in the near future.

“Most insurance companies are now covering select SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for appropriate patients and those companies that currently do not will soon have to,” said Dr. Skolnik, who is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

“The outcomes [associated with use of the new drugs] are robust, the benefits are large, and are well worth the cost,” he added.

The side effects

While others praised these drugs for their beneficial effects, they also noted that the side effects of these drugs are serious and must be discussed with patients.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are linked to gastrointestinal symptoms, especially nausea, while SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to kidney failure, ketoacidosis, and more. The Food and Drug Administration warned in 2018 that the SGLT2 inhibitors can cause a rare serious infection known as Fournier’s gangrene – necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum.

“We have to tell our patients to let us know right away if they get pain or swelling in the genital area,” Dr. Paauw, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted. “The chance that an infection could explode quickly is higher in those who take these drugs.”

Amputation risks also are associated with taking the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin (Invokana). The FDA requires the manufacturer of this drug to include a black-box warning about the risk of “lower-limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot,” but also the leg. In approval trials, the risk doubled versus placebo.

These amputation risks “put a damper on some of the enthusiasm on behalf of physicians and patients ... for taking this drug,” noted Dr. Roberts, who is a professor of internal medicine at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

While a manufacturer-funded study released last year found no link to amputations, the results weren’t powerful enough to rule out a moderately increased risk.

“[If] you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously,” said John B. Buse, MD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a presentation about the study at the 2018 annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The benefits

Despite these risks of adverse events, most interviewed agreed that the many benefits observed in those taking SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists make them worth prescribing, at least to those who are able to afford them.

Both SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists appear to have significant cardiovascular benefits. A 2019 meta-analysis and systematic review found that both drugs reduced major adverse cardiac events by about 12% (Circulation. 2019 Apr 23;139[17]:2022-31).

“They don’t cause hypoglycemia, they lower blood pressure, they don’t cause weight gain, and they might promote weight loss,” noted Dr. Paauw.

SGLT2 inhibitors also have shown signs of kidney benefits. The CREDENCE trial linked canagliflozin to a lowering of kidney disorders versus placebo (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380[24]:2295-306). “The relative risk of the renal-specific composite of end-stage kidney disease, a doubling of the creatinine level, or death from renal causes was lower by 34% (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.81; P less than .001), and the relative risk of end-stage kidney disease was lower by 32% (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.86; P = .002),” the trial investigators wrote.

“They showed very nicely that the drug improved the kidney function of those patients and reduced the kidney deterioration,” said Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist in Tarzana, Calif., who chaired the 2011 and 2015 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Guidelines. The study was especially impressive, he added, because it included patients with low kidney function.

SGLT2 inhibitors’ “diuretic mechanism explains why there is a substantial reduction in heart failure hospitalizations in patients who take these drugs,” said cardiologist Marc E. Goldschmidt, MD, director of the Heart Success Program at Atlantic Health System’s Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center, in an interview. “Both the EMPA-REG Outcome and the CREDENCE trials demonstrated substantial benefit of this class of medications by showing a lower risk of cardiovascular death as well as death from any cause and a lower risk of hospitalization for heart failure."

Overall, the SGLT2 trial data have been very consistent with a benefit for cardiovascular risk reduction, particularly in regard to heart failure hospitalizations and even in potentially preventing heart failure in diabetics,” he added.

Dr. Skolnik, a columnist for Family Practice News, cited SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists’ ability to slow renal disease progression, promote weight loss, and prevent poor cardiac outcomes.“These drugs should be used, in addition to metformin, in all patients with diabetes and vascular disease. These proven outcomes are far better than we ever were able to achieve previously and the strength of the evidence at this point is very strong,” said Dr. Skolnik. “In addition to the benefits of decreasing the development of cardiovascular disease, serious heart failure, and slowing progression of renal disease, these two classes of medication have additional benefits. Both classes help patients lose weight, which is very different from what was found with either sulfonylureas or insulin, which cause patients to gain weight. Also both the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 RAs [receptor agonists] have a low incidence of hypoglycemia. For all these reasons, these have become important medications for us to use in primary care.”

Other recent trials offer “very powerful data” about SGLT2 inhibitors, Dr. Roberts said. That’s good news, since “our approach needs to be toward cardiovascular protection and preservation as well as managing blood sugar.”An Israeli trial, whose results were released in May 2019 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, found that, compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, taking an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.65; P less than .001). This trial also offered a new detail: The patients gained the benefit regardless of whether their baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved or reduced (J Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:suppl 1). The SGLT2 inhibitors used in this trial included dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance).

In another study released this year, a subanalysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, researchers reported that the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced risks of both major adverse cardiovascular events and heart failure hospitalization in the subset of patients with type 2 diabetes and prior myocardial infarction versus controls (Circulation. 2019 May 28;139[22]:2516-27). The absolute risk reduction for major adverse cardiovascular events was 1.9% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.65-1.00; P = .046), while it was 0.6% for heart failure hospitalization (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.72-1.00; P = .055).

These and other studies “speak volumes about the efficacy of managing blood sugar and addressing our biggest nemesis, which is cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Roberts said. “It’s irrefutable. The data [are] very good.”

Dr. Paauw said an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist is best reserved for use in select patients with cardiovascular risks and type 2 diabetes that need management beyond metformin.

For example, they might fit a 70-year-old with persistent hypertension who’s already taking a couple of blood pressure medications. “If they have another cardiovascular risk factor, the cardiovascular protection piece will be a bigger deal,” he said. Also, “it will probably help lower their blood pressure so they can avoid taking another blood pressure medicine.”

Trials of both GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors have shown benefits “in improving [major adverse cardiac events], with the SGLT2 class showing substantial benefit in improving both heart failure and renal outcomes as well,” noted Dr. Skolnik. “It is in this context that one must address the question of whether the price of the medications are worthwhile. With such substantial benefit, there is no question in my mind that – for patients who have underlying cardiovascular illness, which includes patients with existent coronary disease, history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease – it is far and away worth it to prescribe these classes of medications.”

Indeed, the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes’ most recent guidelines now call for a GLP-1 receptor agonist – instead of insulin – to be the first injectable used to treat type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care 2018 Dec; 41[12]:2669-701).

“For the relatively small number of my patients who have been able to access and use these medications for months or longer, more have tolerated the GLP-1 agonists than SGLT2 inhibitors primarily due to urinary issues,” noted Dr. Hopkins.

Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors are another option in patients with type 2 diabetes, but research suggests they may not be a top option for patients with cardiovascular risk. A 2018 review noted that cardiovascular outcome trials for alogliptin (Nesina), saxagliptin (Onglyza), and sitagliptin (Januvia) showed noninferiority but failed to demonstrate any superiority, compared with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high cardiovascular risk (Circ Res. 2018 May 11;122[10]:1439-59).

The combination therapies

Many of the newer drugs are available as combinations with other types of diabetes drugs. In some cases, physicians create their own form of combination therapy by separately prescribing two or more diabetes drugs. Earlier this year, a study suggested the benefits of this kind of add-on therapy: Diabetes outcomes improved in patients who took the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide and an SGLT2 inhibitor (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30066-X).

Dr. Roberts suggested caution, however, when prescribing combination therapies. “My recommendation is always to begin with the individual medications to see if the patient tolerates the drugs and then decide which component needs to be titrated. It’s hard to titrate a combination drug, and it doesn’t leave a lot of flexibility. You never know which drug is doing what.

Dr. Handelsman said some patients may need to take three medications such as metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, and a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

“I don’t recommend using the combinations if you’re not familiar with the drugs ... These are relatively new pharmaceuticals, and most of us are on a learning curve as to how they fit into the armamentarium. If a drug is tolerated with a good response, you can certainly consider going to the combination tablets,” he added.

There is at least one drug that combines these three classes: The newly FDA-approved Qternmet XR, which combines dapagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor), saxagliptin (a GLP-1 receptor agonist), and metformin. As of mid-June 2019, it was not yet available in the United States. Its sister drug Qtern, which combines dapagliflozin and saxagliptin, costs more than $500 a month with a free coupon, according to goodrx.com. In contrast, metformin is extremely inexpensive, costing just a few dollars a month for a common starting dose.

What about adding insulin?

“Both [SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists] work very well with insulin,” Dr. Handelsman said. “There is a nice additive effect on the reduction of [hemoglobin] A1c. The only caution is that, although neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 receptor agonists cause hypoglycemia, in combination with insulin they do increase the risk of hypoglycemia. You may have to adjust the dose of insulin.”

Dr. Hopkins warned that cost becomes an even bigger issue when you add insulin into the mix.

“When insulin comes into the discussion, we are again stuck with astronomical costs which many struggle to afford,” he explained.

Indeed, the price tag on these drugs seems to be the biggest problem physicians have with them.

“The challenges in managing patients with diabetes aren’t the risks associated with the drugs. It’s dealing with their insurers,” noted Dr. Roberts.

Dr. Hopkins, Dr. Paauw, Dr. Roberts, and Dr. Syed reported no disclosures. Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Goldschmidt is paid to speak by Novartis. Dr. Handelsman reported research grants, consulting work, and speaker honoraria from Amgen, Gilead, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr Skolnik reported nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly. He also serves on the advisory boards of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Intarcia, Mylan, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Paauw and Dr. Skolnik are columnists for Family Practice News and Internal Medicine News.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this report.

The options for treating type 2 diabetes without insulin have grown beyond metformin to include a long list of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists that can be taken with or without metformin. These new drugs have cardiovascular and kidney benefits and help with weight loss, but they also carry risks and, according to some experts, their costs can be prohibitively expensive.

Given the medical community’s long-term experience with treating patients with metformin, and metformin’s lower cost, most of the physicians interviewed for this article advise using SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists as second-line treatments. Others said that they would prefer to use the newer drugs as first-line therapies in select high-risk patients, but prior authorization hurdles created by insurance companies make that approach too burdensome.

“The economics of U.S. health care is stacked against many of our patients with diabetes in the current era,” Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, said in an interview.

Even when their insurance approves the drugs, patients still may not be able to afford the copay, explained Dr. Hopkins, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and director of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. “Sometimes patients can purchase drugs at a lower cost than the copay to purchase with the ‘drug coverage’ in their insurance plan – unfortunately, this is not the case with the newer diabetes medications we are discussing here.”

“SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists can cost several hundred dollars a month, and insurers often balk at paying for them. They’ll say, ‘Have you tried metformin?’ ” explained endocrinologist Victor Lawrence Roberts, MD, in a interview. “We have to work with insurance companies the best we can in a stepwise fashion.”

According to Dr. Roberts, 80% of his patients with diabetes struggle with the cost of medicine in general. “They’re either underinsured or not insured or their formulary is limited.

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, agreed in an interview that the newer drugs can be problematic on the insurance front.

“For some patients they aren’t affordable, especially for the uninsured if you can’t get them on an assistance program,” said Dr. Paauw, who is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university.

Dr. Hopkins, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted that “unfortunately, the treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients who cannot achieve control with metformin, diet, weight control, and exercise is a story of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ The ‘haves’ are those who have pharmacy benefits which make access to newer agents like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists a possibility.”

“I have had very few of the ‘have nots’ who have been able to even consider these newer agents, which carry price tags of $600-$1,300 a month even with the availability of discounting coupons in the marketplace,” he added. “Most of these patients end up requiring a sulfonylurea or TZD [thiazolidinedione] as a second agent to achieve glycemic control. This makes it very difficult to achieve sufficient weight and metabolic control to avoid an eventual switch to insulin.”

Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an endocrine-trained general internist at DukeHealth in Durham, N.C., said she prescribes SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in combination with metformin. “I prescribe them frequently, but they are not first-line treatments,” she explained.

“Nothing replaces diet and exercise” as therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes, she added.

Neil S. Skolnik, MD, said that insurance companies were not preventing patients from using these drugs in his experience. He also provided an optimistic take on the accessibility of these drugs in the near future.

“Most insurance companies are now covering select SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for appropriate patients and those companies that currently do not will soon have to,” said Dr. Skolnik, who is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

“The outcomes [associated with use of the new drugs] are robust, the benefits are large, and are well worth the cost,” he added.

The side effects

While others praised these drugs for their beneficial effects, they also noted that the side effects of these drugs are serious and must be discussed with patients.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are linked to gastrointestinal symptoms, especially nausea, while SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to kidney failure, ketoacidosis, and more. The Food and Drug Administration warned in 2018 that the SGLT2 inhibitors can cause a rare serious infection known as Fournier’s gangrene – necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum.

“We have to tell our patients to let us know right away if they get pain or swelling in the genital area,” Dr. Paauw, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted. “The chance that an infection could explode quickly is higher in those who take these drugs.”

Amputation risks also are associated with taking the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin (Invokana). The FDA requires the manufacturer of this drug to include a black-box warning about the risk of “lower-limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot,” but also the leg. In approval trials, the risk doubled versus placebo.

These amputation risks “put a damper on some of the enthusiasm on behalf of physicians and patients ... for taking this drug,” noted Dr. Roberts, who is a professor of internal medicine at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

While a manufacturer-funded study released last year found no link to amputations, the results weren’t powerful enough to rule out a moderately increased risk.

“[If] you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously,” said John B. Buse, MD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a presentation about the study at the 2018 annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The benefits

Despite these risks of adverse events, most interviewed agreed that the many benefits observed in those taking SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists make them worth prescribing, at least to those who are able to afford them.

Both SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists appear to have significant cardiovascular benefits. A 2019 meta-analysis and systematic review found that both drugs reduced major adverse cardiac events by about 12% (Circulation. 2019 Apr 23;139[17]:2022-31).

“They don’t cause hypoglycemia, they lower blood pressure, they don’t cause weight gain, and they might promote weight loss,” noted Dr. Paauw.

SGLT2 inhibitors also have shown signs of kidney benefits. The CREDENCE trial linked canagliflozin to a lowering of kidney disorders versus placebo (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380[24]:2295-306). “The relative risk of the renal-specific composite of end-stage kidney disease, a doubling of the creatinine level, or death from renal causes was lower by 34% (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.81; P less than .001), and the relative risk of end-stage kidney disease was lower by 32% (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.86; P = .002),” the trial investigators wrote.

“They showed very nicely that the drug improved the kidney function of those patients and reduced the kidney deterioration,” said Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist in Tarzana, Calif., who chaired the 2011 and 2015 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Guidelines. The study was especially impressive, he added, because it included patients with low kidney function.

SGLT2 inhibitors’ “diuretic mechanism explains why there is a substantial reduction in heart failure hospitalizations in patients who take these drugs,” said cardiologist Marc E. Goldschmidt, MD, director of the Heart Success Program at Atlantic Health System’s Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center, in an interview. “Both the EMPA-REG Outcome and the CREDENCE trials demonstrated substantial benefit of this class of medications by showing a lower risk of cardiovascular death as well as death from any cause and a lower risk of hospitalization for heart failure."

Overall, the SGLT2 trial data have been very consistent with a benefit for cardiovascular risk reduction, particularly in regard to heart failure hospitalizations and even in potentially preventing heart failure in diabetics,” he added.

Dr. Skolnik, a columnist for Family Practice News, cited SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists’ ability to slow renal disease progression, promote weight loss, and prevent poor cardiac outcomes.“These drugs should be used, in addition to metformin, in all patients with diabetes and vascular disease. These proven outcomes are far better than we ever were able to achieve previously and the strength of the evidence at this point is very strong,” said Dr. Skolnik. “In addition to the benefits of decreasing the development of cardiovascular disease, serious heart failure, and slowing progression of renal disease, these two classes of medication have additional benefits. Both classes help patients lose weight, which is very different from what was found with either sulfonylureas or insulin, which cause patients to gain weight. Also both the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 RAs [receptor agonists] have a low incidence of hypoglycemia. For all these reasons, these have become important medications for us to use in primary care.”

Other recent trials offer “very powerful data” about SGLT2 inhibitors, Dr. Roberts said. That’s good news, since “our approach needs to be toward cardiovascular protection and preservation as well as managing blood sugar.”An Israeli trial, whose results were released in May 2019 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, found that, compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, taking an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.65; P less than .001). This trial also offered a new detail: The patients gained the benefit regardless of whether their baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved or reduced (J Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:suppl 1). The SGLT2 inhibitors used in this trial included dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance).

In another study released this year, a subanalysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, researchers reported that the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced risks of both major adverse cardiovascular events and heart failure hospitalization in the subset of patients with type 2 diabetes and prior myocardial infarction versus controls (Circulation. 2019 May 28;139[22]:2516-27). The absolute risk reduction for major adverse cardiovascular events was 1.9% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.65-1.00; P = .046), while it was 0.6% for heart failure hospitalization (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.72-1.00; P = .055).

These and other studies “speak volumes about the efficacy of managing blood sugar and addressing our biggest nemesis, which is cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Roberts said. “It’s irrefutable. The data [are] very good.”

Dr. Paauw said an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist is best reserved for use in select patients with cardiovascular risks and type 2 diabetes that need management beyond metformin.

For example, they might fit a 70-year-old with persistent hypertension who’s already taking a couple of blood pressure medications. “If they have another cardiovascular risk factor, the cardiovascular protection piece will be a bigger deal,” he said. Also, “it will probably help lower their blood pressure so they can avoid taking another blood pressure medicine.”

Trials of both GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors have shown benefits “in improving [major adverse cardiac events], with the SGLT2 class showing substantial benefit in improving both heart failure and renal outcomes as well,” noted Dr. Skolnik. “It is in this context that one must address the question of whether the price of the medications are worthwhile. With such substantial benefit, there is no question in my mind that – for patients who have underlying cardiovascular illness, which includes patients with existent coronary disease, history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease – it is far and away worth it to prescribe these classes of medications.”

Indeed, the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes’ most recent guidelines now call for a GLP-1 receptor agonist – instead of insulin – to be the first injectable used to treat type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care 2018 Dec; 41[12]:2669-701).

“For the relatively small number of my patients who have been able to access and use these medications for months or longer, more have tolerated the GLP-1 agonists than SGLT2 inhibitors primarily due to urinary issues,” noted Dr. Hopkins.

Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors are another option in patients with type 2 diabetes, but research suggests they may not be a top option for patients with cardiovascular risk. A 2018 review noted that cardiovascular outcome trials for alogliptin (Nesina), saxagliptin (Onglyza), and sitagliptin (Januvia) showed noninferiority but failed to demonstrate any superiority, compared with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high cardiovascular risk (Circ Res. 2018 May 11;122[10]:1439-59).

The combination therapies

Many of the newer drugs are available as combinations with other types of diabetes drugs. In some cases, physicians create their own form of combination therapy by separately prescribing two or more diabetes drugs. Earlier this year, a study suggested the benefits of this kind of add-on therapy: Diabetes outcomes improved in patients who took the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide and an SGLT2 inhibitor (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30066-X).

Dr. Roberts suggested caution, however, when prescribing combination therapies. “My recommendation is always to begin with the individual medications to see if the patient tolerates the drugs and then decide which component needs to be titrated. It’s hard to titrate a combination drug, and it doesn’t leave a lot of flexibility. You never know which drug is doing what.

Dr. Handelsman said some patients may need to take three medications such as metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, and a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

“I don’t recommend using the combinations if you’re not familiar with the drugs ... These are relatively new pharmaceuticals, and most of us are on a learning curve as to how they fit into the armamentarium. If a drug is tolerated with a good response, you can certainly consider going to the combination tablets,” he added.

There is at least one drug that combines these three classes: The newly FDA-approved Qternmet XR, which combines dapagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor), saxagliptin (a GLP-1 receptor agonist), and metformin. As of mid-June 2019, it was not yet available in the United States. Its sister drug Qtern, which combines dapagliflozin and saxagliptin, costs more than $500 a month with a free coupon, according to goodrx.com. In contrast, metformin is extremely inexpensive, costing just a few dollars a month for a common starting dose.

What about adding insulin?

“Both [SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists] work very well with insulin,” Dr. Handelsman said. “There is a nice additive effect on the reduction of [hemoglobin] A1c. The only caution is that, although neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 receptor agonists cause hypoglycemia, in combination with insulin they do increase the risk of hypoglycemia. You may have to adjust the dose of insulin.”

Dr. Hopkins warned that cost becomes an even bigger issue when you add insulin into the mix.

“When insulin comes into the discussion, we are again stuck with astronomical costs which many struggle to afford,” he explained.

Indeed, the price tag on these drugs seems to be the biggest problem physicians have with them.

“The challenges in managing patients with diabetes aren’t the risks associated with the drugs. It’s dealing with their insurers,” noted Dr. Roberts.

Dr. Hopkins, Dr. Paauw, Dr. Roberts, and Dr. Syed reported no disclosures. Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Goldschmidt is paid to speak by Novartis. Dr. Handelsman reported research grants, consulting work, and speaker honoraria from Amgen, Gilead, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr Skolnik reported nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly. He also serves on the advisory boards of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Intarcia, Mylan, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Paauw and Dr. Skolnik are columnists for Family Practice News and Internal Medicine News.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this report.

The options for treating type 2 diabetes without insulin have grown beyond metformin to include a long list of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists that can be taken with or without metformin. These new drugs have cardiovascular and kidney benefits and help with weight loss, but they also carry risks and, according to some experts, their costs can be prohibitively expensive.

Given the medical community’s long-term experience with treating patients with metformin, and metformin’s lower cost, most of the physicians interviewed for this article advise using SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists as second-line treatments. Others said that they would prefer to use the newer drugs as first-line therapies in select high-risk patients, but prior authorization hurdles created by insurance companies make that approach too burdensome.

“The economics of U.S. health care is stacked against many of our patients with diabetes in the current era,” Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, said in an interview.

Even when their insurance approves the drugs, patients still may not be able to afford the copay, explained Dr. Hopkins, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and director of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. “Sometimes patients can purchase drugs at a lower cost than the copay to purchase with the ‘drug coverage’ in their insurance plan – unfortunately, this is not the case with the newer diabetes medications we are discussing here.”

“SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists can cost several hundred dollars a month, and insurers often balk at paying for them. They’ll say, ‘Have you tried metformin?’ ” explained endocrinologist Victor Lawrence Roberts, MD, in a interview. “We have to work with insurance companies the best we can in a stepwise fashion.”

According to Dr. Roberts, 80% of his patients with diabetes struggle with the cost of medicine in general. “They’re either underinsured or not insured or their formulary is limited.

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, agreed in an interview that the newer drugs can be problematic on the insurance front.

“For some patients they aren’t affordable, especially for the uninsured if you can’t get them on an assistance program,” said Dr. Paauw, who is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university.

Dr. Hopkins, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted that “unfortunately, the treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients who cannot achieve control with metformin, diet, weight control, and exercise is a story of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ The ‘haves’ are those who have pharmacy benefits which make access to newer agents like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists a possibility.”

“I have had very few of the ‘have nots’ who have been able to even consider these newer agents, which carry price tags of $600-$1,300 a month even with the availability of discounting coupons in the marketplace,” he added. “Most of these patients end up requiring a sulfonylurea or TZD [thiazolidinedione] as a second agent to achieve glycemic control. This makes it very difficult to achieve sufficient weight and metabolic control to avoid an eventual switch to insulin.”

Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an endocrine-trained general internist at DukeHealth in Durham, N.C., said she prescribes SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in combination with metformin. “I prescribe them frequently, but they are not first-line treatments,” she explained.

“Nothing replaces diet and exercise” as therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes, she added.

Neil S. Skolnik, MD, said that insurance companies were not preventing patients from using these drugs in his experience. He also provided an optimistic take on the accessibility of these drugs in the near future.

“Most insurance companies are now covering select SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for appropriate patients and those companies that currently do not will soon have to,” said Dr. Skolnik, who is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

“The outcomes [associated with use of the new drugs] are robust, the benefits are large, and are well worth the cost,” he added.

The side effects

While others praised these drugs for their beneficial effects, they also noted that the side effects of these drugs are serious and must be discussed with patients.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are linked to gastrointestinal symptoms, especially nausea, while SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to kidney failure, ketoacidosis, and more. The Food and Drug Administration warned in 2018 that the SGLT2 inhibitors can cause a rare serious infection known as Fournier’s gangrene – necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum.

“We have to tell our patients to let us know right away if they get pain or swelling in the genital area,” Dr. Paauw, who is on the Internal Medicine News board, noted. “The chance that an infection could explode quickly is higher in those who take these drugs.”

Amputation risks also are associated with taking the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin (Invokana). The FDA requires the manufacturer of this drug to include a black-box warning about the risk of “lower-limb amputations, most frequently of the toe and midfoot,” but also the leg. In approval trials, the risk doubled versus placebo.

These amputation risks “put a damper on some of the enthusiasm on behalf of physicians and patients ... for taking this drug,” noted Dr. Roberts, who is a professor of internal medicine at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

While a manufacturer-funded study released last year found no link to amputations, the results weren’t powerful enough to rule out a moderately increased risk.

“[If] you are at high risk for having an amputation, we really have to take this risk very seriously,” said John B. Buse, MD, chief of the division of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a presentation about the study at the 2018 annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The benefits

Despite these risks of adverse events, most interviewed agreed that the many benefits observed in those taking SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists make them worth prescribing, at least to those who are able to afford them.

Both SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists appear to have significant cardiovascular benefits. A 2019 meta-analysis and systematic review found that both drugs reduced major adverse cardiac events by about 12% (Circulation. 2019 Apr 23;139[17]:2022-31).

“They don’t cause hypoglycemia, they lower blood pressure, they don’t cause weight gain, and they might promote weight loss,” noted Dr. Paauw.

SGLT2 inhibitors also have shown signs of kidney benefits. The CREDENCE trial linked canagliflozin to a lowering of kidney disorders versus placebo (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380[24]:2295-306). “The relative risk of the renal-specific composite of end-stage kidney disease, a doubling of the creatinine level, or death from renal causes was lower by 34% (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.81; P less than .001), and the relative risk of end-stage kidney disease was lower by 32% (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.86; P = .002),” the trial investigators wrote.

“They showed very nicely that the drug improved the kidney function of those patients and reduced the kidney deterioration,” said Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist in Tarzana, Calif., who chaired the 2011 and 2015 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Guidelines. The study was especially impressive, he added, because it included patients with low kidney function.

SGLT2 inhibitors’ “diuretic mechanism explains why there is a substantial reduction in heart failure hospitalizations in patients who take these drugs,” said cardiologist Marc E. Goldschmidt, MD, director of the Heart Success Program at Atlantic Health System’s Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center, in an interview. “Both the EMPA-REG Outcome and the CREDENCE trials demonstrated substantial benefit of this class of medications by showing a lower risk of cardiovascular death as well as death from any cause and a lower risk of hospitalization for heart failure."

Overall, the SGLT2 trial data have been very consistent with a benefit for cardiovascular risk reduction, particularly in regard to heart failure hospitalizations and even in potentially preventing heart failure in diabetics,” he added.

Dr. Skolnik, a columnist for Family Practice News, cited SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists’ ability to slow renal disease progression, promote weight loss, and prevent poor cardiac outcomes.“These drugs should be used, in addition to metformin, in all patients with diabetes and vascular disease. These proven outcomes are far better than we ever were able to achieve previously and the strength of the evidence at this point is very strong,” said Dr. Skolnik. “In addition to the benefits of decreasing the development of cardiovascular disease, serious heart failure, and slowing progression of renal disease, these two classes of medication have additional benefits. Both classes help patients lose weight, which is very different from what was found with either sulfonylureas or insulin, which cause patients to gain weight. Also both the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP-1 RAs [receptor agonists] have a low incidence of hypoglycemia. For all these reasons, these have become important medications for us to use in primary care.”

Other recent trials offer “very powerful data” about SGLT2 inhibitors, Dr. Roberts said. That’s good news, since “our approach needs to be toward cardiovascular protection and preservation as well as managing blood sugar.”An Israeli trial, whose results were released in May 2019 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, found that, compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, taking an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.65; P less than .001). This trial also offered a new detail: The patients gained the benefit regardless of whether their baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved or reduced (J Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73[9]:suppl 1). The SGLT2 inhibitors used in this trial included dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance).

In another study released this year, a subanalysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, researchers reported that the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced risks of both major adverse cardiovascular events and heart failure hospitalization in the subset of patients with type 2 diabetes and prior myocardial infarction versus controls (Circulation. 2019 May 28;139[22]:2516-27). The absolute risk reduction for major adverse cardiovascular events was 1.9% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.65-1.00; P = .046), while it was 0.6% for heart failure hospitalization (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.72-1.00; P = .055).

These and other studies “speak volumes about the efficacy of managing blood sugar and addressing our biggest nemesis, which is cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Roberts said. “It’s irrefutable. The data [are] very good.”

Dr. Paauw said an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist is best reserved for use in select patients with cardiovascular risks and type 2 diabetes that need management beyond metformin.

For example, they might fit a 70-year-old with persistent hypertension who’s already taking a couple of blood pressure medications. “If they have another cardiovascular risk factor, the cardiovascular protection piece will be a bigger deal,” he said. Also, “it will probably help lower their blood pressure so they can avoid taking another blood pressure medicine.”

Trials of both GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors have shown benefits “in improving [major adverse cardiac events], with the SGLT2 class showing substantial benefit in improving both heart failure and renal outcomes as well,” noted Dr. Skolnik. “It is in this context that one must address the question of whether the price of the medications are worthwhile. With such substantial benefit, there is no question in my mind that – for patients who have underlying cardiovascular illness, which includes patients with existent coronary disease, history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease – it is far and away worth it to prescribe these classes of medications.”

Indeed, the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes’ most recent guidelines now call for a GLP-1 receptor agonist – instead of insulin – to be the first injectable used to treat type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care 2018 Dec; 41[12]:2669-701).

“For the relatively small number of my patients who have been able to access and use these medications for months or longer, more have tolerated the GLP-1 agonists than SGLT2 inhibitors primarily due to urinary issues,” noted Dr. Hopkins.

Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors are another option in patients with type 2 diabetes, but research suggests they may not be a top option for patients with cardiovascular risk. A 2018 review noted that cardiovascular outcome trials for alogliptin (Nesina), saxagliptin (Onglyza), and sitagliptin (Januvia) showed noninferiority but failed to demonstrate any superiority, compared with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and high cardiovascular risk (Circ Res. 2018 May 11;122[10]:1439-59).

The combination therapies

Many of the newer drugs are available as combinations with other types of diabetes drugs. In some cases, physicians create their own form of combination therapy by separately prescribing two or more diabetes drugs. Earlier this year, a study suggested the benefits of this kind of add-on therapy: Diabetes outcomes improved in patients who took the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide and an SGLT2 inhibitor (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30066-X).

Dr. Roberts suggested caution, however, when prescribing combination therapies. “My recommendation is always to begin with the individual medications to see if the patient tolerates the drugs and then decide which component needs to be titrated. It’s hard to titrate a combination drug, and it doesn’t leave a lot of flexibility. You never know which drug is doing what.

Dr. Handelsman said some patients may need to take three medications such as metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, and a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

“I don’t recommend using the combinations if you’re not familiar with the drugs ... These are relatively new pharmaceuticals, and most of us are on a learning curve as to how they fit into the armamentarium. If a drug is tolerated with a good response, you can certainly consider going to the combination tablets,” he added.

There is at least one drug that combines these three classes: The newly FDA-approved Qternmet XR, which combines dapagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor), saxagliptin (a GLP-1 receptor agonist), and metformin. As of mid-June 2019, it was not yet available in the United States. Its sister drug Qtern, which combines dapagliflozin and saxagliptin, costs more than $500 a month with a free coupon, according to goodrx.com. In contrast, metformin is extremely inexpensive, costing just a few dollars a month for a common starting dose.

What about adding insulin?

“Both [SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists] work very well with insulin,” Dr. Handelsman said. “There is a nice additive effect on the reduction of [hemoglobin] A1c. The only caution is that, although neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 receptor agonists cause hypoglycemia, in combination with insulin they do increase the risk of hypoglycemia. You may have to adjust the dose of insulin.”

Dr. Hopkins warned that cost becomes an even bigger issue when you add insulin into the mix.

“When insulin comes into the discussion, we are again stuck with astronomical costs which many struggle to afford,” he explained.

Indeed, the price tag on these drugs seems to be the biggest problem physicians have with them.

“The challenges in managing patients with diabetes aren’t the risks associated with the drugs. It’s dealing with their insurers,” noted Dr. Roberts.

Dr. Hopkins, Dr. Paauw, Dr. Roberts, and Dr. Syed reported no disclosures. Dr. Buse is an investigator for Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Goldschmidt is paid to speak by Novartis. Dr. Handelsman reported research grants, consulting work, and speaker honoraria from Amgen, Gilead, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr Skolnik reported nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly. He also serves on the advisory boards of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Intarcia, Mylan, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Paauw and Dr. Skolnik are columnists for Family Practice News and Internal Medicine News.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this report.

BMI screening trigger for type 2 diabetes is unreliable for at-risk black, Hispanic adults

SAN FRANCISCO – according to findings presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The conclusions come from a review of 5,656 participants aged 45-84 years in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), an ongoing prospective cohort study. The participants had no signs of cardiovascular disease at enrollment.