User login

62-year-old woman • dysuria • dyspareunia • urinary incontinence • Dx?

THE CASE

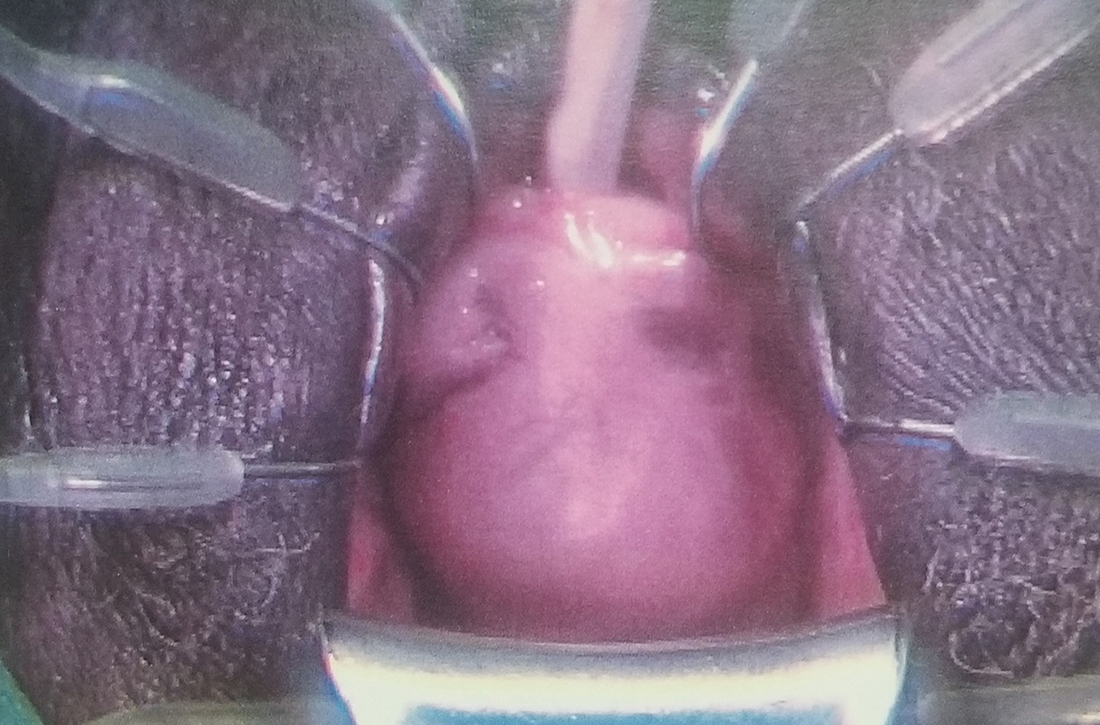

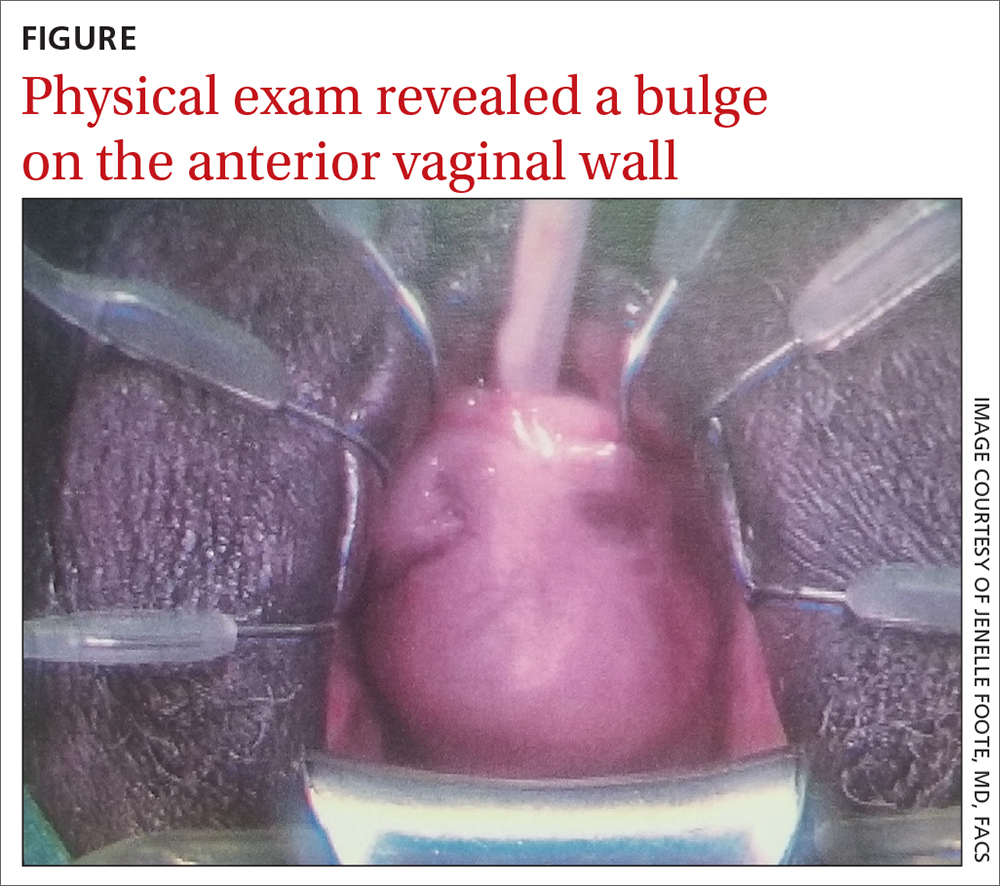

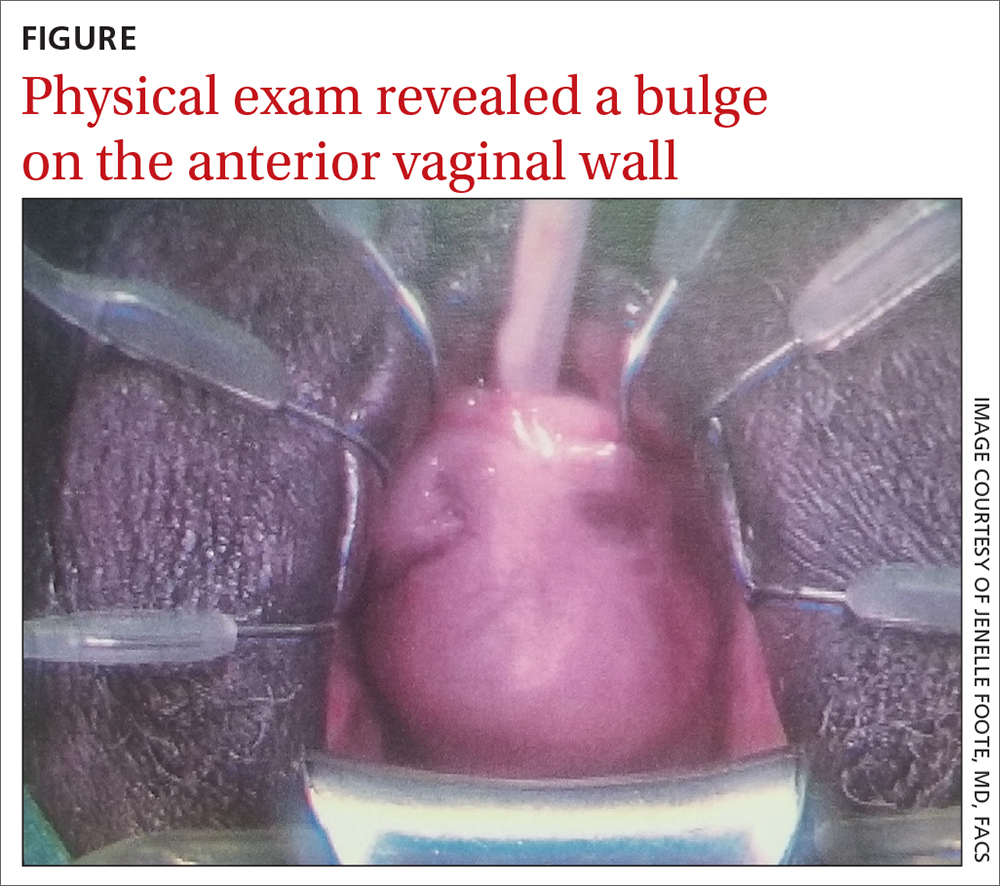

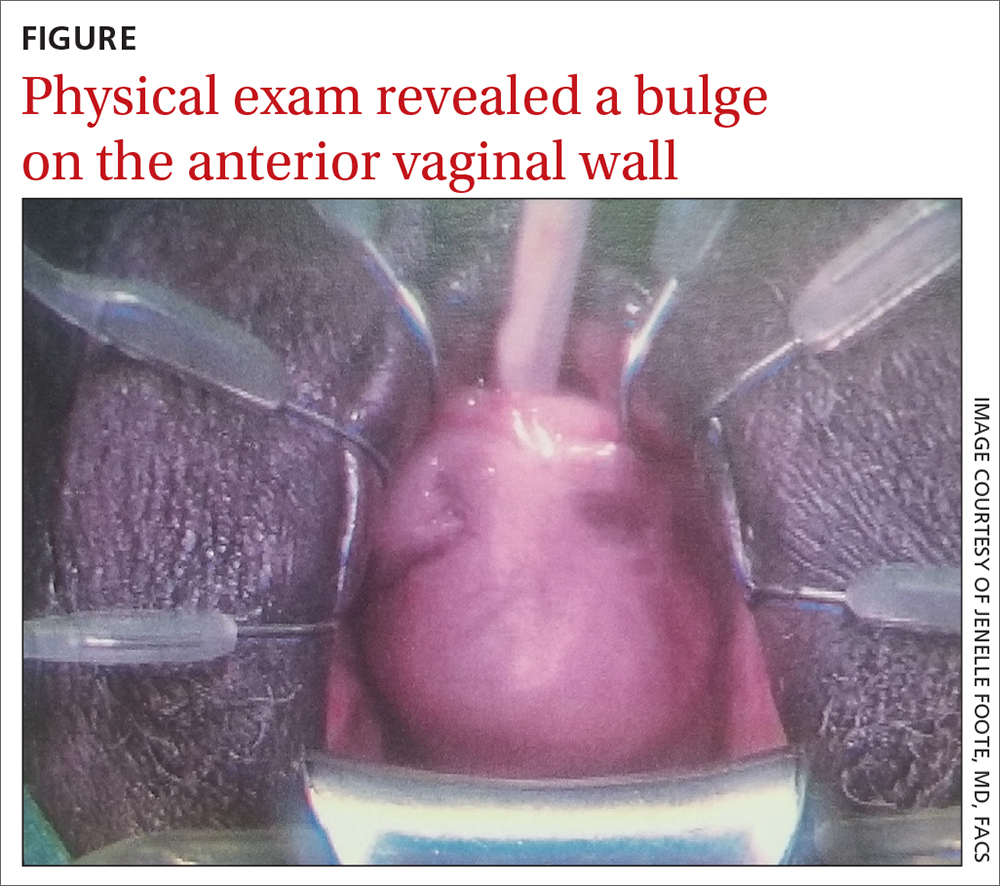

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

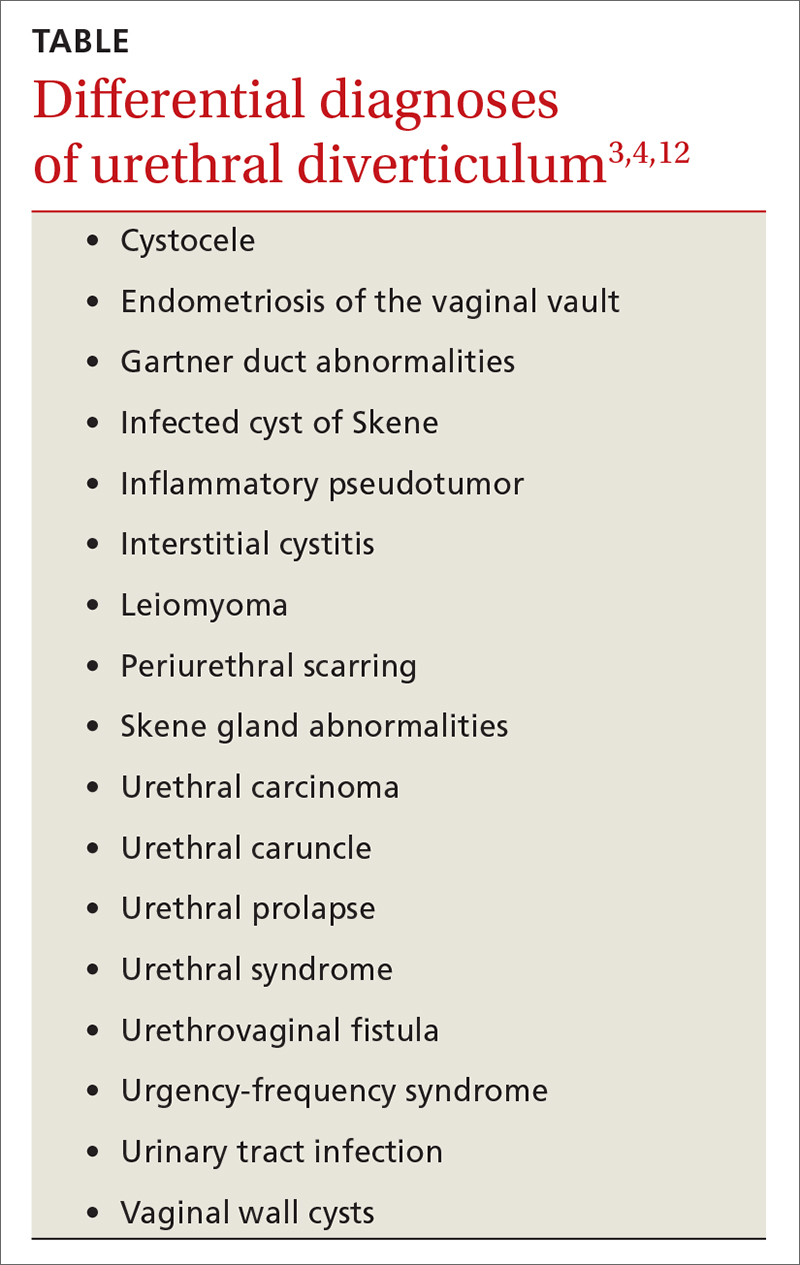

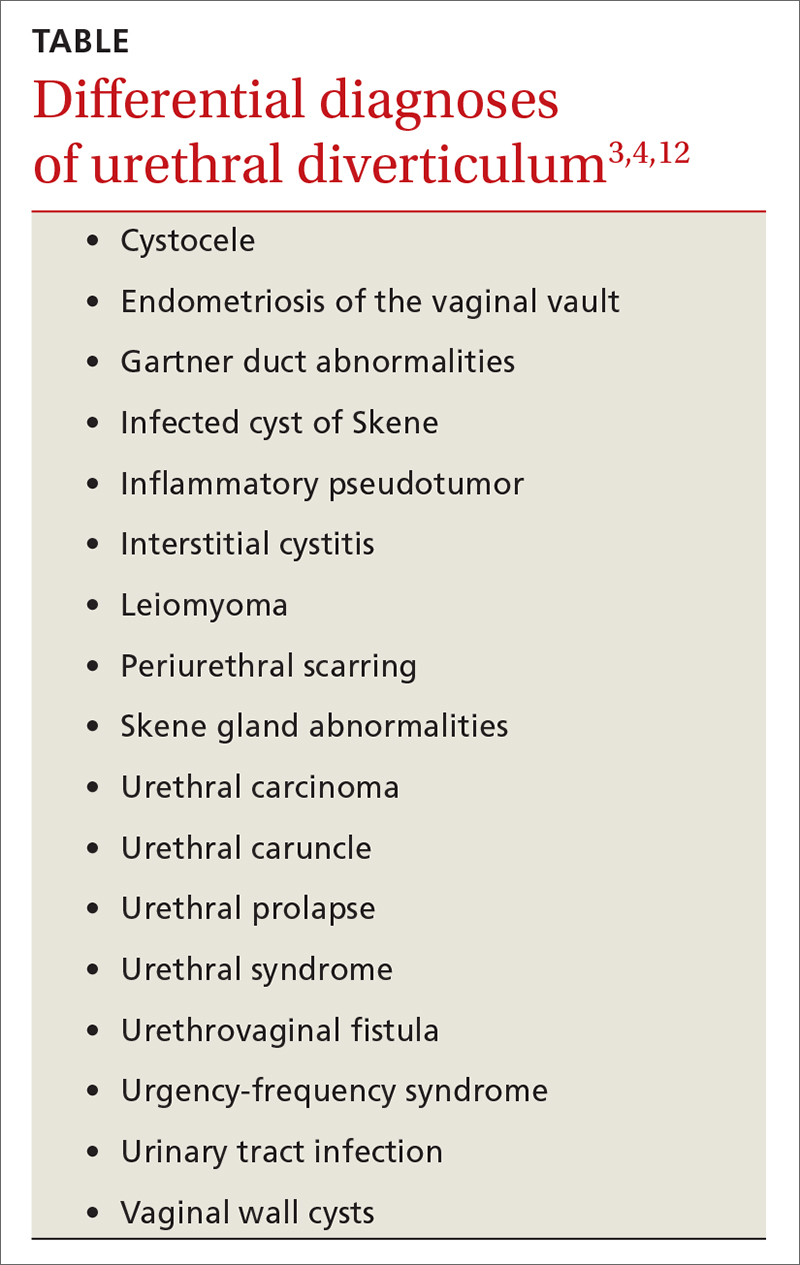

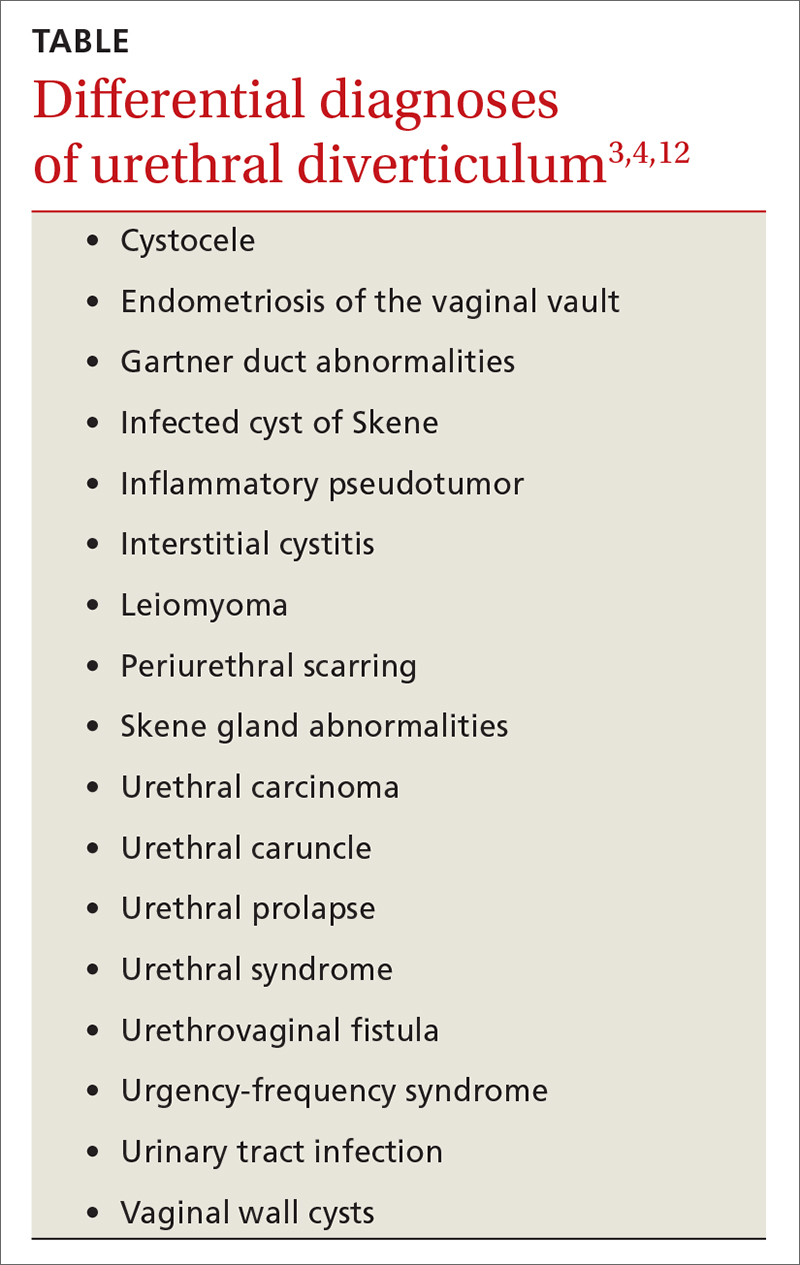

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; [email protected]

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

THE CASE

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman presented to the clinic as a new patient for her annual physical examination. She reported a 9-year history of symptoms including dysuria, post-void dribbling, dyspareunia, and urinary incontinence on review of systems. Her physical examination revealed an anterior vaginal wall bulge (FIGURE). Results of a urinalysis were negative. The patient was referred to Urology for further evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large periurethral diverticulum with a horseshoe shape.

DISCUSSION

Women are more likely than men to develop urethral diverticulum, and it can manifest at any age, usually in the third through seventh decade.4,5 It was once thought to be more common in Black women, although the literature does not support this.6 Black women are 3 times more likely to be operated on than White women to treat urethral diverticula.7

Unknown origin. Most cases of urethral diverticulum are acquired; the etiology is uncertain.8,9 The assumption is that urethral diverticulum occurs as a result of repeated infection of the periurethral glands with subsequent obstruction, abscess formation, and chronic inflammation.1,2,4 Childbirth trauma, iatrogenic causes, and urethral instrumentation have also been implicated.3,4 In rare cases of congenital urethral diverticula, the diverticula are thought to be remnants of Gartner duct cysts, and yet, incidence in the pediatric population is low.8

Diagnosis is confirmed through physical exam and imaging

The urethral diverticulum manifests anteriorly and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall may reveal a painful mass.10 A split-speculum is used for careful inspection and palpation of the anterior vaginal wall.9 If the diverticulum is found to be firm on palpation, or there is bloody urethral drainage, malignancy (although rare) must be ruled out.4,5 Refer such patients to a urologist or urogynecologist.

Radiologic imaging (eg, ultrasound,

Continue to: Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis

Nonspecific symptoms may lead to misdiagnosis. The symptoms associated with urethral diverticulum are diverse and linked to several differential diagnoses (TABLE).3,4,12 The most common signs and symptoms are pelvic pain, urethral mass, dyspareunia, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and post-void dribbling—all of which are considered nonspecific.3,10,11 These nonspecific symptoms (or even an absence of symptoms), along with a physician’s lack of familiarity with urethral diverticulum, can result in a misdiagnosis or even a delayed diagnosis (up to 5.2 years).3,10

Managing symptoms vs preventing recurrence

Conservative management with antibiotics, anticholinergics, and/or observation is acceptable for patients with mild symptoms and those who are pregnant or who have a current infection or serious comorbidities that preclude surgery.3,9 Complete excision of the urethral diverticulum with reconstruction is considered the most effective surgical management for symptom relief and recurrence prevention.3,4,11,14

Our patient underwent a successful transvaginal suburethral diverticulectomy.

THE TAKEAWAY

The diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum is often delayed or misdiagnosed because symptoms are diverse and nonspecific. One should have a high degree of suspicion for urethral diverticulum in patients with dysuria, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and irritative voiding symptoms who are not responding to conservative management. Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality. However, a pelvic MRI is the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing urethral diverticulum.12

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 720 Westview Drive, Atlanta, GA 30310; [email protected]

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

1. Billow M, James R, Resnick K, et al. An unusual presentation of a urethral diverticulum as a vaginal wall mass: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-171

2. El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:73-79. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2155-2

3. Cameron AP. Urethral diverticulum in the female: a meta-analysis of modern series. Minerva Ginecol. 2016;68:186-210.

4. Greiman AK, Rolef J, Rovner ES. Urethral diverticulum: a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2019;17:49-57. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1589748

5. Allen D, Mishra V, Pepper W, et al. A single-center experience of symptomatic male urethral diverticula. Urology. 2007;70:650-653. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1111

6. O’Connor E, Iatropoulou D, Hashimoto S, et al. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:703-729. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.07.08

7. Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Meyn L, et al. Surgical procedures for urethral diverticula in women in the United States, 1979-1997. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:158-161. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1145-9

8. Riyach O, Ahsaini M, Tazi MF, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: cases report and literature. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-8-1

9. Antosh DD, Gutman RE. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:264-271. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318234a242

10. Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000;164:428-433.

11. Reeves FA, Inman RD, Chapple CR. Management of symptomatic urethral diverticula in women: a single-centre experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:164-172. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.041

12. Dwarkasing RS, Dinkelaar W, Hop WCJ, et al. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticula and differential diagnosis in symptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:676-682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6144

13. Porten S, Kielb S. Diagnosis of female diverticula using magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Urol. 2008;2008:213516. doi: 10.1155/2008/213516

14. Ockrim JL, Allen DJ, Shah PJ, et al. A tertiary experience of urethral diverticulectomy: diagnosis, imaging and surgical outcomes. BJU Int. 2009;103:1550-1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08348.x

How to better identify and manage women with elevated breast cancer risk

Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer in women in the United States; it is estimated that there will be 287,850 new cases of breast cancer in the United States during 2022 with 43,250 deaths.1 Lives are extended and saved every day because of a robust arsenal of treatments and interventions available to those who have been given a diagnosis of breast cancer. And, of course, lives are also extended and saved when we identify women at risk and provide early interventions. But in busy offices where time is short and there are competing demands on our time, proper assessment of a woman’s risk of breast cancer does not always happen. As a result, women with a higher risk of breast cancer may not be getting appropriate management.2,3

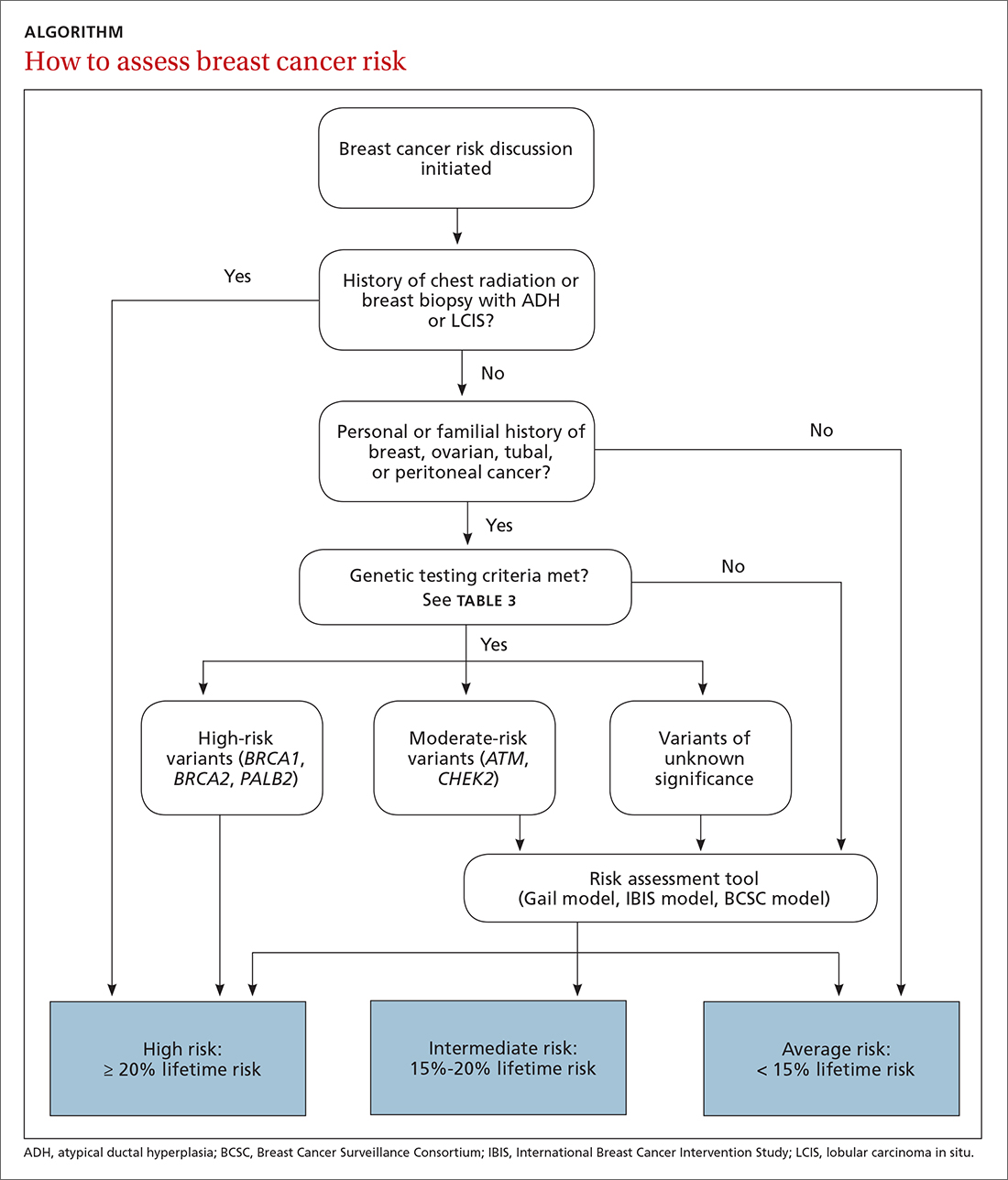

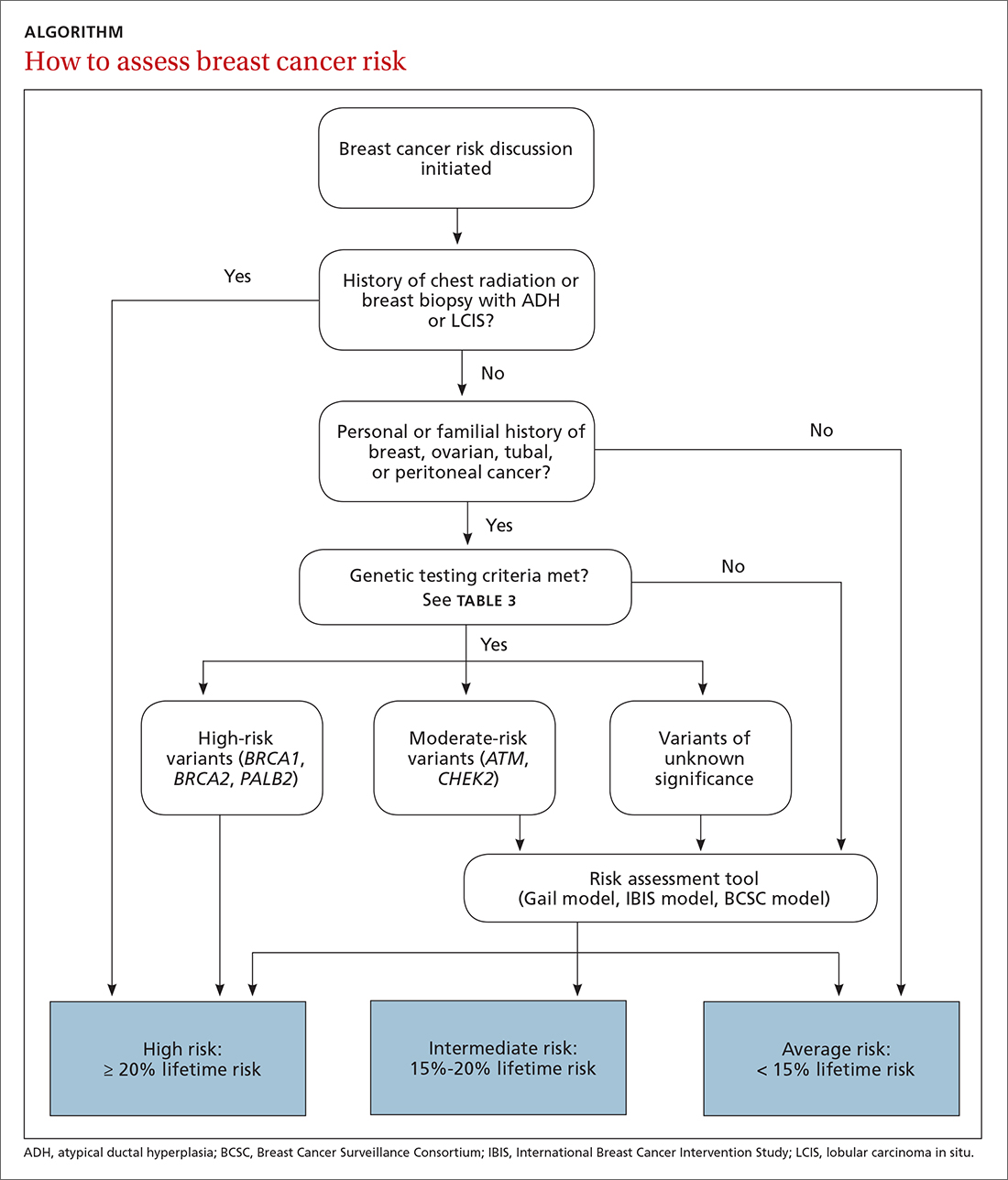

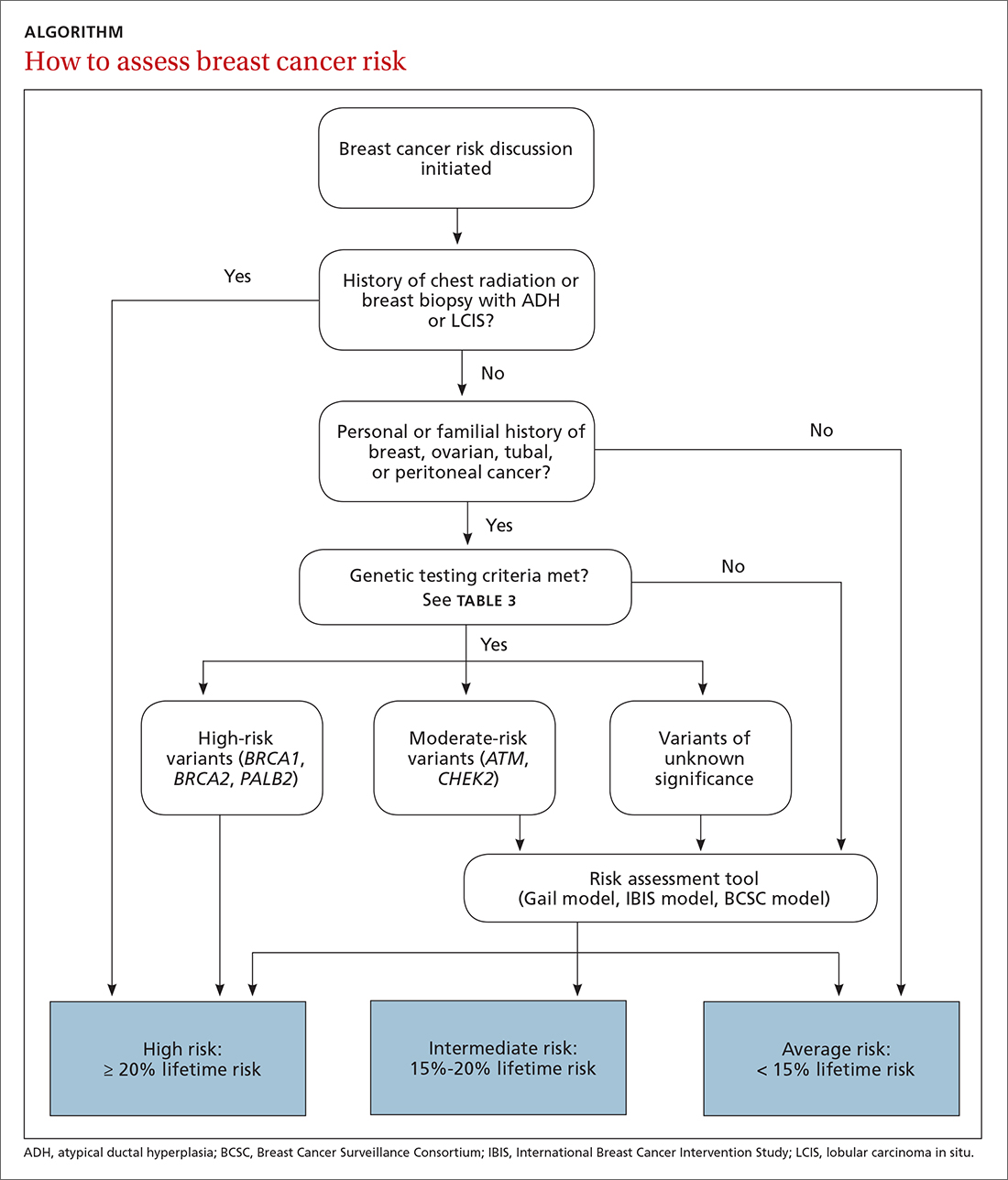

Familiarizing yourself with several risk-assessment tools and knowing when genetic testing is needed can make a big difference. Knowing the timing of mammograms and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for women deemed to be at high risk is also key. The following review employs a case-based approach (with an accompanying ALGORITHM) to illustrate how best to identify women who are at heightened risk of breast cancer and maximize their care. We also discuss the chemoprophylaxis regimens that may be used for those at increased risk.

CASE

Rachel P, age 37, presents to establish care. She has an Ashkenazi Jewish background and wonders if she should start doing breast cancer screening before age 40. She has 2 children, ages 4 years and 2 years. Her maternal aunt had unilateral breast cancer at age 54, and her maternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer at age 65.

Risk assessment

The risk assessment process (see ALGORITHM) must start with either the clinician or the patient initiating the discussion about breast cancer risk. The clinician may initiate the discussion with a new patient or at an annual physical examination. The patient may start the discussion because they are experiencing new breast symptoms, have anxiety about developing breast cancer, or have a family member with a new cancer diagnosis.

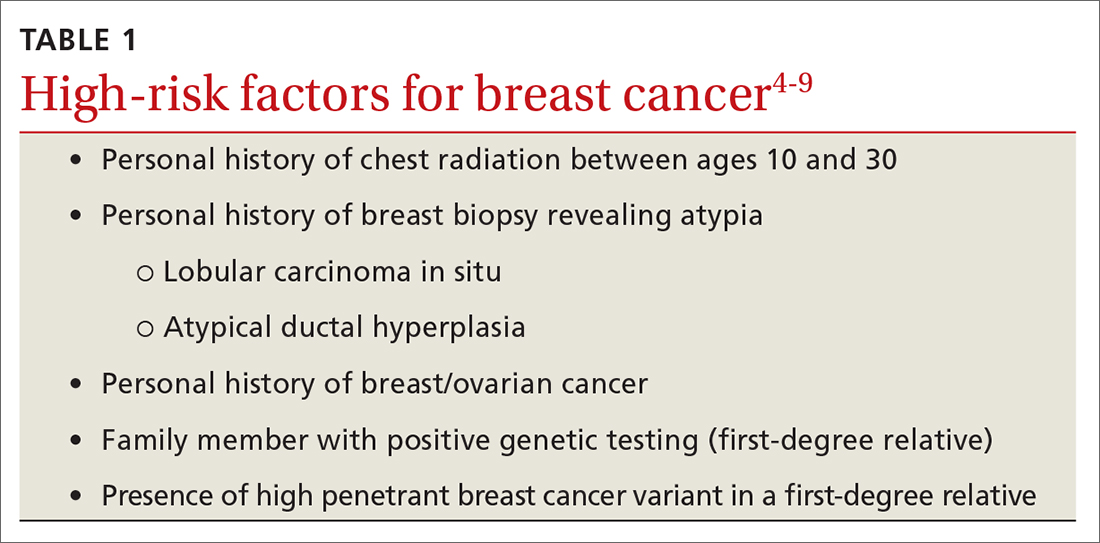

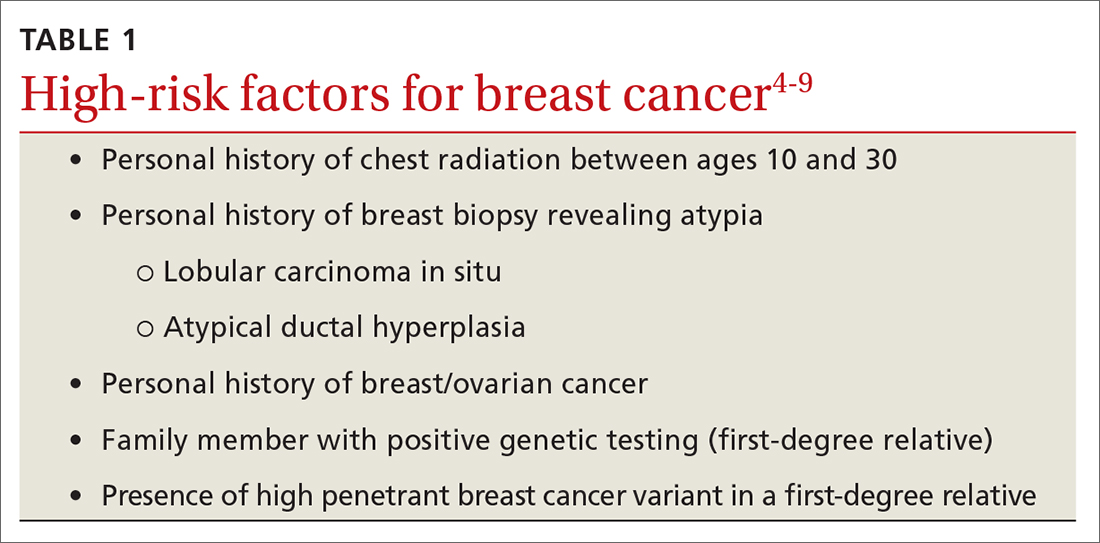

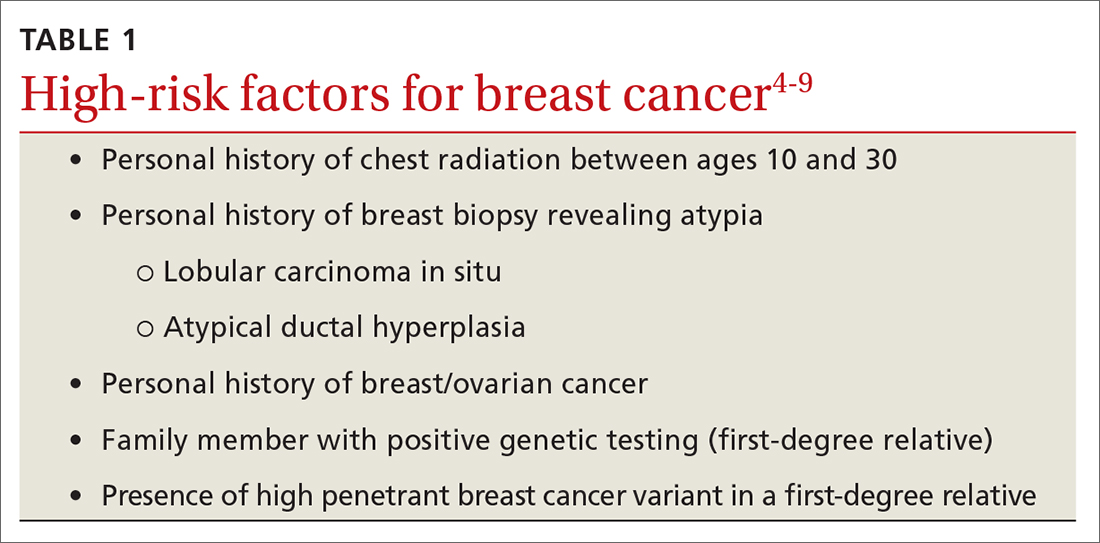

Risk factors. There are single factors that convey enough risk to automatically designate the patient as high risk (see TABLE 14-9). These factors include having a history of chest radiation between the ages of 10 and 30, a history of breast biopsy with either lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), past breast and/or ovarian cancer, and either a family or personal history of a high penetrant genetic variant for breast cancer.4-9

In women with previous chest radiation, breast cancer risk correlates with the total dose of radiation.5 For women with a personal history of breast cancer, the younger the age at diagnosis, the higher the risk of contralateral breast cancer.5 Precancerous changes such as ADH, LCIS, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) also confer moderate increases in risk. Women with these diagnoses will commonly have follow-up with specialists.

Risk assessment tools. There are several models available to assess a woman’s breast cancer risk (see TABLE 210-12). The Gail model (https://bcrisktool.cancer.gov/) is the oldest, quickest, and most widely known. However, the Gail model only accounts for first-degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer, may underpredict risk in women with a more extensive family history, and has not been studied in women younger than 35. The International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) Risk Evaluation Tool (https://ibis-risk-calculator.magview.com/), commonly referred to as the Tyrer-Cuzick model, incorporates second-degree relatives into the prediction model—although women may not know their full family history. Both the IBIS and the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model (https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/intro.htm) include breast density in the prediction algorithm. The choice of tool depends on clinician comfort and individual patient risk factors. There is no evidence that one model is better than another.10-12

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Ms. P’s clinician starts with an assessment using the Gail model. However, when the result comes back with average risk, the clinician decides to follow up with the Tyrer-Cuzick model in order to incorporate Ms. P’s multiple second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer. (The BCSC model was not used because it only includes first-degree relatives.)

Genetic testing

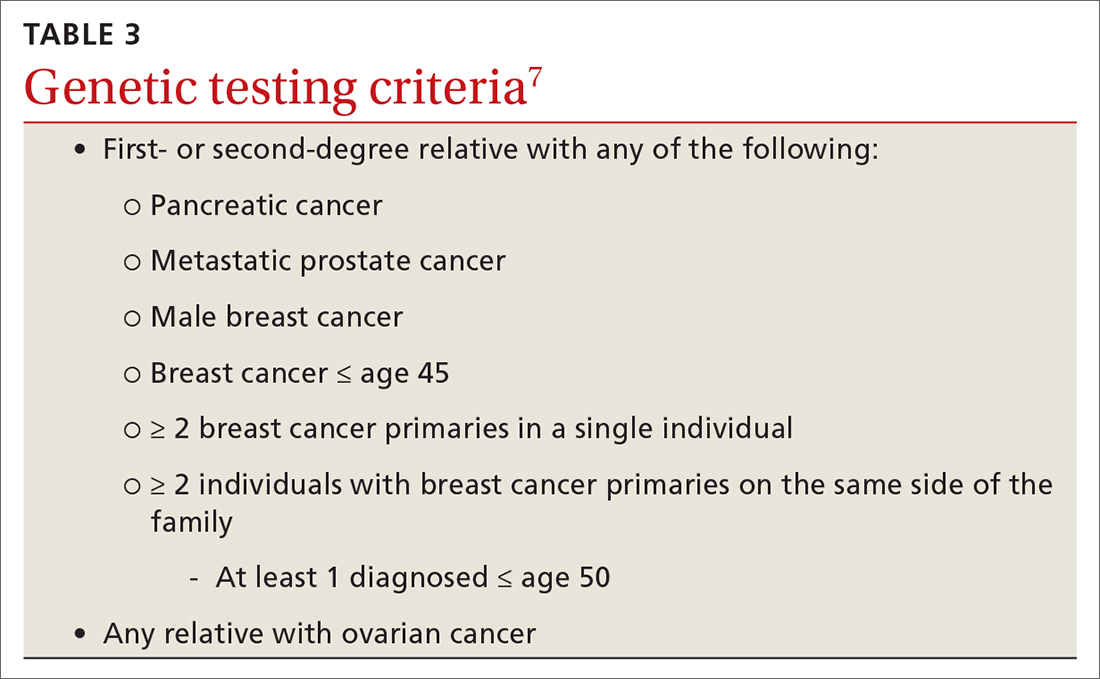

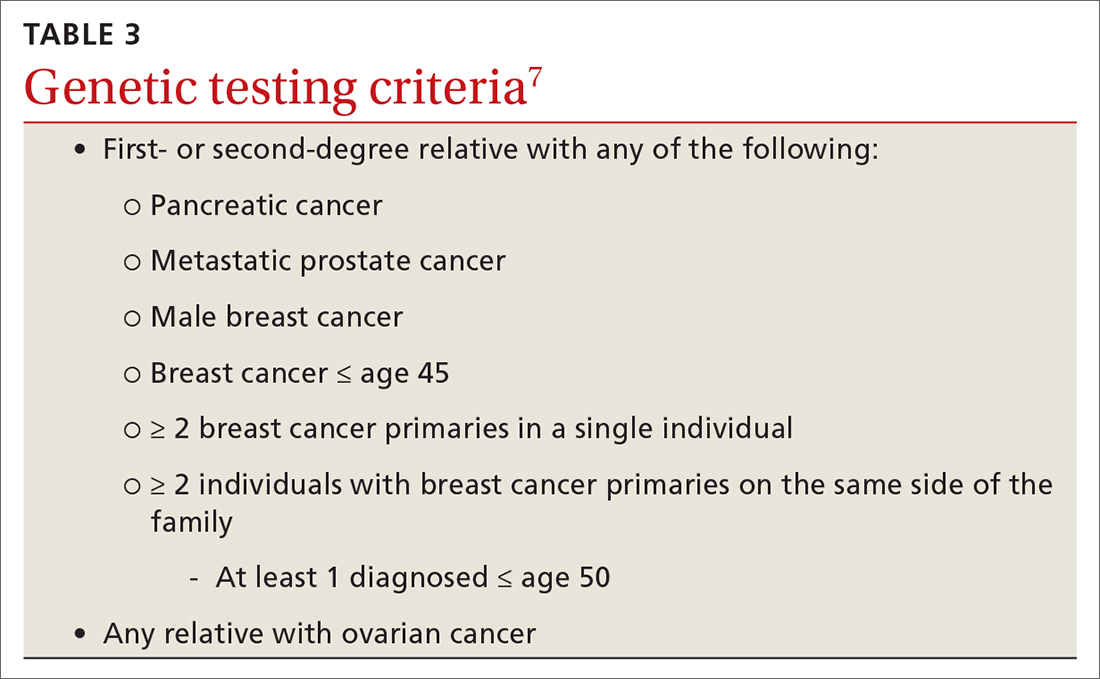

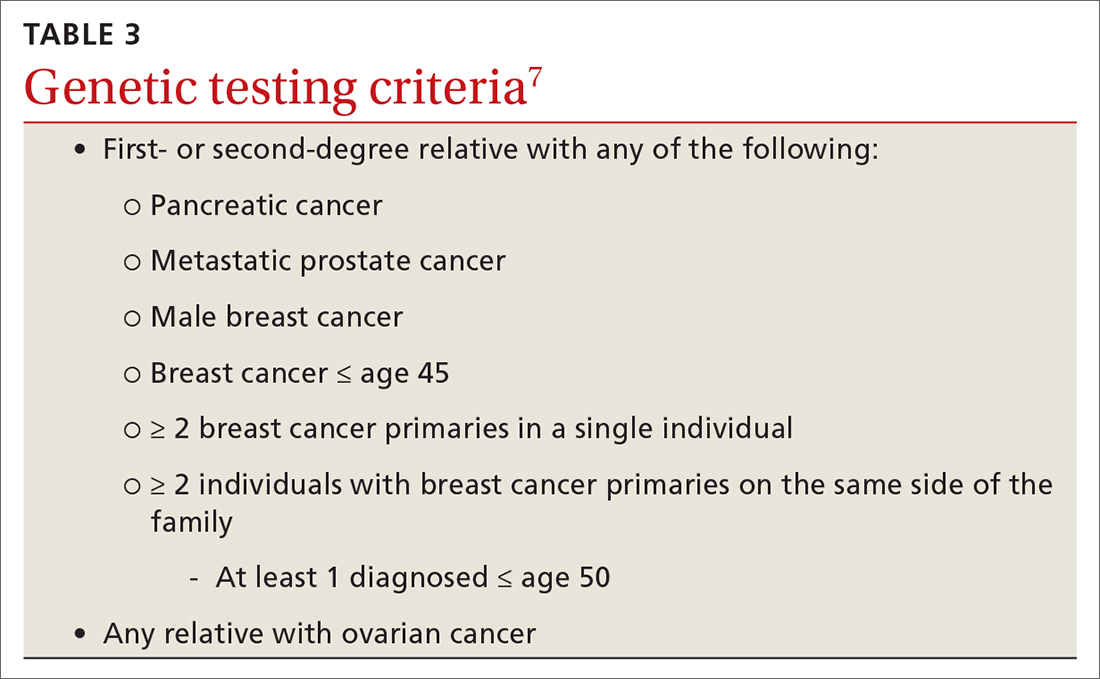

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend genetic testing if a woman has a first- or second-degree relative with pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, male breast cancer, breast cancer at age 45 or younger, 2 or more breast cancers in a single person, 2 or more people on the same side of the family with at least 1 diagnosed at age 50 or younger, or any relative with ovarian cancer (see TABLE 3).7 Before ordering genetic testing, it is useful to refer the patient to a genetic counselor for a thorough discussion of options.

Results of genetic testing may include high-risk variants, moderate-risk variants, and variants of unknown significance (VUS), or be negative for any variants. High-risk variants for breast cancer include BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and cancer syndrome variants such as TP53, PTEN, STK11, and CDH1.5,6,9,13-15 These high-risk variants confer sufficient risk that women with these mutations are automatically categorized in the high-risk group. It is estimated that high-risk variants account for only 25% of the genetic risk for breast cancer.16

BRCA1/2 and PTEN mutations confer greater than 80% lifetime risk, while other high-risk variants such as TP53, CDH1, and STK11 confer risks between 25% and 40%. These variants are also associated with cancers of other organs, depending on the mutation.17

Moderate-risk variants—ATM and CHEK2—do not confer sufficient risk to elevate women into the high-risk group. However, they do qualify these intermediate-risk women to participate in a specialized management strategy.5,9,13,18

VUS are those for which the associated risk is unclear, but more research may be done to categorize the risk.9 The clinical management of women with VUS usually entails close monitoring.

In an effort to better characterize breast cancer risk using a combination of pathogenic variants found in broad multi-gene cancer predisposition panels, researchers have developed a method to combine risks in a “polygenic risk score” (PRS) that can be used to counsel women (see “What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?” on page 203).19-21PRS predicts an additional 18% of genetic risk in women of European descent.21

SIDEBAR

What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?

- A polygenic risk score (PRS) is a mathematical method to combine results from a variety of different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; ie, single base pair variants) into a prediction tool that can estimate a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer.

- A PRS may be most accurate in determining risk for women with intermediate pathogenic variants, such as ATM and CHEK2. 19,20

- PRS has not been studied in non-White women.21

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Using the assessment results, the clinician talks to Ms. P about her lifetime risk for breast cancer. The Gail model indicates her lifetime risk is 13.3%, just slightly higher than the average (12.5%), and her 5-year risk is 0.5% (average, 0.4%). The IBIS or Tyrer-Cuzick model, which takes into account her second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer and her Ashkenazi ethnicity (which confers increased risk due to elevated risk of BRCA mutations), predicts her lifetime risk of breast cancer to be 20.4%. This categorizes Ms. P as high risk.

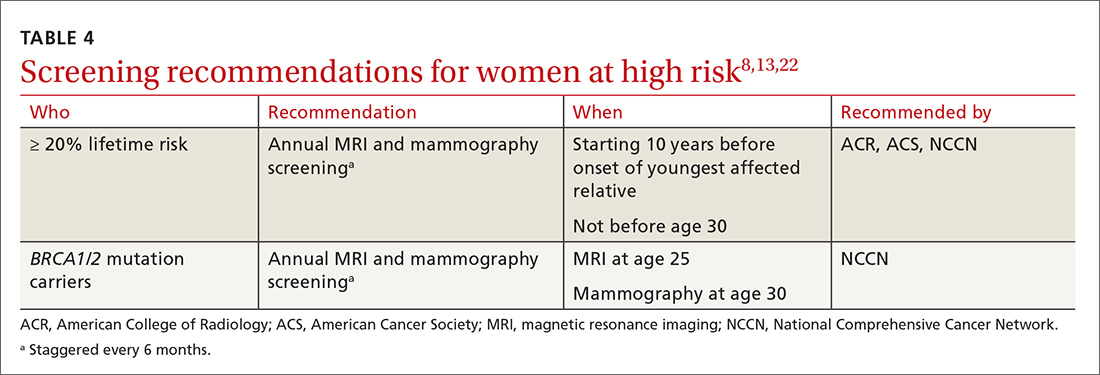

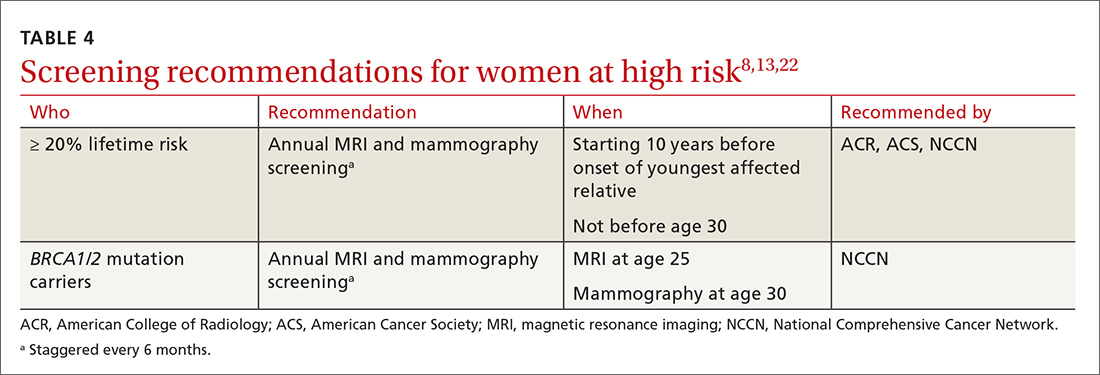

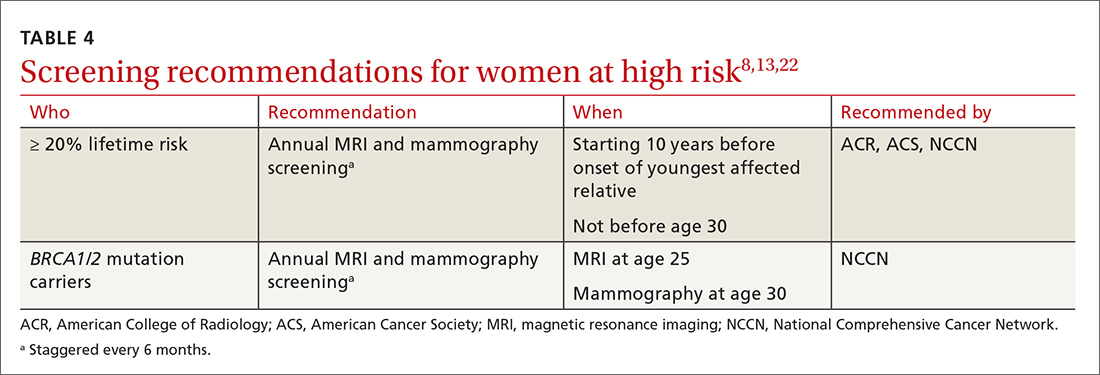

Enhanced screening recommendations for women at high risk

TABLE 48,13,22 summarizes screening recommendations for women deemed to be at high risk for breast cancer. The American Cancer Society (ACS), NCCN, and the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommend that women with at least a 20% lifetime risk have yearly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mammography (staggered so that the patient has 1 test every 6 months) starting 10 years before the age of onset for the youngest affected relative but not before age 30.8 For carriers of high-risk (as well as intermediate-risk) genes, NCCN recommends annual MRI screening starting at age 40.13BRCA1/2 screening includes annual MRI starting at age 25 and annual mammography every 6 months starting at age 30.22 Clinicians should counsel women with moderate risk factors (elevated breast density; personal history of ADH, LCIS, or DCIS) about the potential risks and benefits of enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis.

Risk-reduction strategies

Chemoprophylaxis

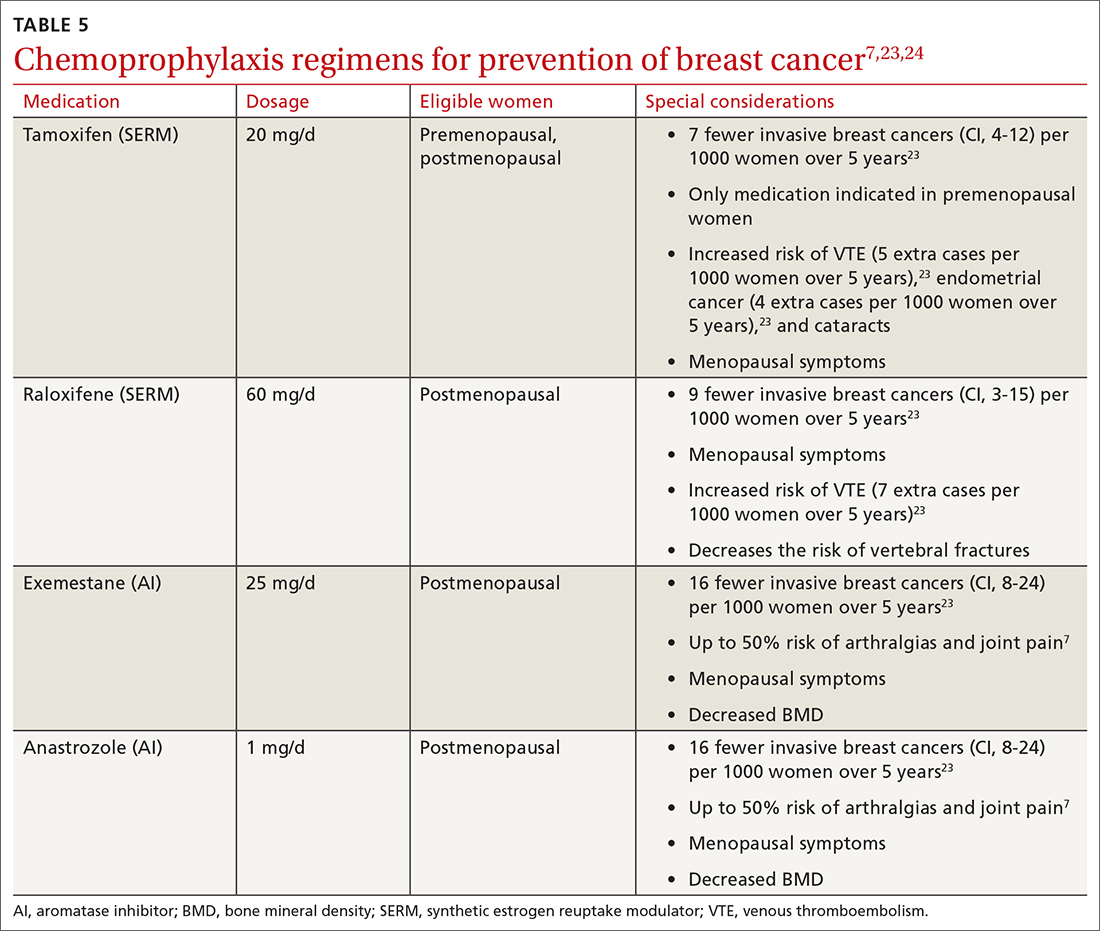

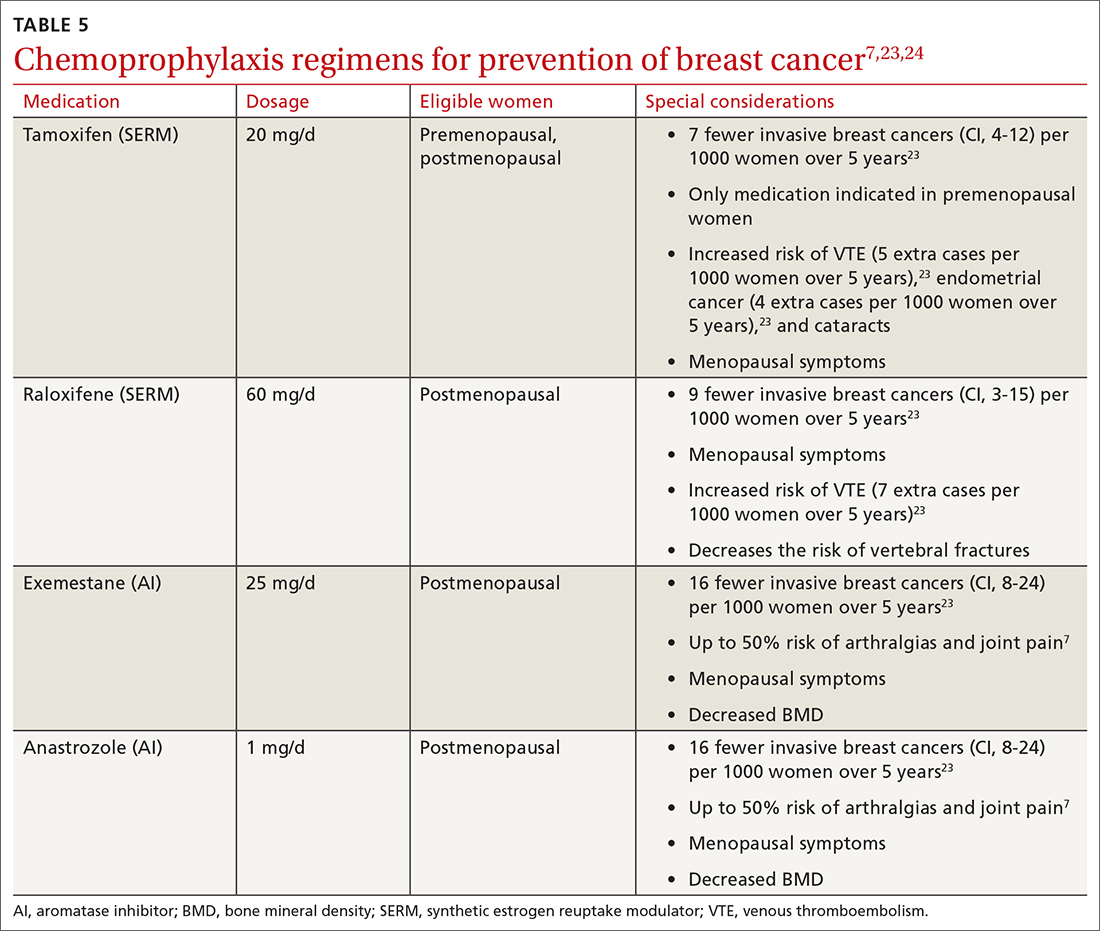

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women at increased risk for breast cancer consider chemoprophylaxis (B recommendation)23 based on convincing evidence that 5 years of treatment with either a synthetic estrogen reuptake modulator (SERM) or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) decreases the incidence of estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. (See TABLE 57,23,24 for absolute risk reduction.) There is no benefit for chemoprophylaxis in women at average risk (D recommendation).23 It is unclear whether chemoprophylaxis is indicated in women with moderate increased risk (ie, who do not meet the 20% lifetime risk criteria). Chemoprophylaxis may not be effective in women with BRCA1 mutations, as they often develop triple-negative breast cancers.

Accurate risk assessment and shared decision-making enable the clinician and patient to discuss the potential risks and benefits of chemoprophylaxis.7,24 The USPSTF did not find that any 1 risk prediction tool was better than another to identify women who should be counseled about chemoprophylaxis. Clinicians should counsel all women taking AIs about optimizing bone health with adequate calcium and vitamin D intake and routine bone density tests.

Surgical risk reduction

The NCCN guidelines state that risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy is reserved for individuals with high-risk gene variants and individuals with prior chest radiation between ages 10 and 30.25 NCCN also recommends discussing risk-reducing mastectomy with all women with BRCA mutations.22

Bilateral mastectomy is the most effective method to reduce breast cancer risk and should be discussed after age 25 in women with BRCA mutations and at least 8 years after chest radiation is completed.26 There is a reduction in breast cancer incidence of 90%.25 Breast imaging for screening (mammography or MRI) is not indicated after risk-reducing mastectomy. However, clinical breast examinations of the surgical site are important, because there is a small risk of developing breast cancer in that area.26

Risk-reducing oophorectomy is the standard of care for women with BRCA mutations to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. It can also reduce the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations.27

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Based on her risk assessment results, family history, and genetic heritage, Ms. P qualifies for referral to a genetic counselor for discussion of BRCA testing. The clinician discusses adding annual MRI to Ms. P’s breast cancer screening regimen, based on ACS, NCCN, and ACR recommendations, due to her 20.4% lifetime risk. Discussion of whether and when to start chemoprophylaxis is typically based on breast cancer risk, projected benefit, and the potential impact of medication adverse effects. A high-risk woman is eligible for 5 years of chemoprophylaxis (tamoxifen if premenopausal) based on her lifetime risk. The clinician discusses timing with Ms. P, and even though she is finished with childbearing, she would like to wait until she is age 45, which is before the age at which her aunt was given a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Conclusion

Primary care clinicians are well positioned to identify women with an elevated risk of breast cancer and refer them for enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis (see ALGORITHM). Shared decision-making with the inclusion of patient decision aids (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsearch.php?criteria=breast+cancer) about genetic testing, chemoprophylaxis, and prophylactic mastectomy or oophorectomy may help women at intermediate or high risk of breast cancer feel empowered to make decisions about their breast—and overall—health.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

2. Guerra CE, Sherman M, Armstrong K. Diffusion of breast cancer risk assessment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:272-279. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.03.080153

3. Hamilton JG, Abdiwahab E, Edwards HM, et al. Primary care providers’ cancer genetic testing-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication behaviors: a systematic review and research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:315-324. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4

4. Eden KB, Ivlev I, Bensching KL, et al. Use of an online breast cancer risk assessment and patient decision aid in primary care practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:763-769. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8143

5. Kleibl Z, Kristensen VN. Women at high risk of breast cancer: molecular characteristics, clinical presentation and management. Breast. 2016;28:136-44. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.05.006

6. Sciaraffa T, Guido B, Khan SA, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment and management programs: a practical guide. Breast J. 2020;26:1556-1564. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13967

7. Farkas A, Vanderberg R, Merriam S, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention: a practical guide for the primary care provider. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:46-56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7643

8. McClintock AH, Golob AL, Laya MB. Breast cancer risk assessment: a step-wise approach for primary care providers on the front lines of shared decision making. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1268-1275. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.017

9. Catana A, Apostu AP, Antemie RG. Multi gene panel testing for hereditary breast cancer - is it ready to be used? Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:220-225. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1083

10. Barke LD, Freivogel ME. Breast cancer risk assessment models and high-risk screening. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55:457-474. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.12.013

11. Amir E, Freedman OC, Seruga B, et al. Assessing women at high risk of breast cancer: a review of risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:680-91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq088

12. Kim G, Bahl M. Assessing risk of breast cancer: a review of risk prediction models. J Breast Imaging. 2021;3:144-155. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbab001

13. Narod SA. Which genes for hereditary breast cancer? N Engl J Med. 2021;384:471-473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2035083

14. Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1190-1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424

15. Obeid EI, Hall MJ, Daly MB. Multigene panel testing and breast cancer risk: is it time to scale down? JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1176-1177. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0342

16. Michailidou K, Lindström S, Dennis J, et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551:92-94. doi: 10.1038/nature24284

17. Shiovitz S, Korde LA. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1291-1299. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv022

18. Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:440-451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005936

19. Gao C, Polley EC, Hart SN, et al. Risk of breast cancer among carriers of pathogenic variants in breast cancer predisposition genes varies by polygenic risk score. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2564-2573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01992

20. Gallagher S, Hughes E, Wagner S, et al. Association of a polygenic risk score with breast cancer among women carriers of high- and moderate-risk breast cancer genes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208501. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8501

21. Yanes T, Young MA, Meiser B, et al. Clinical applications of polygenic breast cancer risk: a critical review and perspectives of an emerging field. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01260-3

22. Schrager S, Torell E, Ledford K, et al. Managing a woman with BRCA mutations? Shared decision-making is key. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:237-243

23. US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11885

24. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3230-3235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

25. Britt KL, Cuzick J, Phillips KA. Key steps for effective breast cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:417-436. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0266-x

26. Jatoi I, Kemp Z. Risk-reducing mastectomy. JAMA. 2021;325:1781-1782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22414

27. Choi Y, Terry MB, Daly MB, et al. Association of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy with breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:585-592. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7995

Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer in women in the United States; it is estimated that there will be 287,850 new cases of breast cancer in the United States during 2022 with 43,250 deaths.1 Lives are extended and saved every day because of a robust arsenal of treatments and interventions available to those who have been given a diagnosis of breast cancer. And, of course, lives are also extended and saved when we identify women at risk and provide early interventions. But in busy offices where time is short and there are competing demands on our time, proper assessment of a woman’s risk of breast cancer does not always happen. As a result, women with a higher risk of breast cancer may not be getting appropriate management.2,3

Familiarizing yourself with several risk-assessment tools and knowing when genetic testing is needed can make a big difference. Knowing the timing of mammograms and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for women deemed to be at high risk is also key. The following review employs a case-based approach (with an accompanying ALGORITHM) to illustrate how best to identify women who are at heightened risk of breast cancer and maximize their care. We also discuss the chemoprophylaxis regimens that may be used for those at increased risk.

CASE

Rachel P, age 37, presents to establish care. She has an Ashkenazi Jewish background and wonders if she should start doing breast cancer screening before age 40. She has 2 children, ages 4 years and 2 years. Her maternal aunt had unilateral breast cancer at age 54, and her maternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer at age 65.

Risk assessment

The risk assessment process (see ALGORITHM) must start with either the clinician or the patient initiating the discussion about breast cancer risk. The clinician may initiate the discussion with a new patient or at an annual physical examination. The patient may start the discussion because they are experiencing new breast symptoms, have anxiety about developing breast cancer, or have a family member with a new cancer diagnosis.

Risk factors. There are single factors that convey enough risk to automatically designate the patient as high risk (see TABLE 14-9). These factors include having a history of chest radiation between the ages of 10 and 30, a history of breast biopsy with either lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), past breast and/or ovarian cancer, and either a family or personal history of a high penetrant genetic variant for breast cancer.4-9

In women with previous chest radiation, breast cancer risk correlates with the total dose of radiation.5 For women with a personal history of breast cancer, the younger the age at diagnosis, the higher the risk of contralateral breast cancer.5 Precancerous changes such as ADH, LCIS, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) also confer moderate increases in risk. Women with these diagnoses will commonly have follow-up with specialists.

Risk assessment tools. There are several models available to assess a woman’s breast cancer risk (see TABLE 210-12). The Gail model (https://bcrisktool.cancer.gov/) is the oldest, quickest, and most widely known. However, the Gail model only accounts for first-degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer, may underpredict risk in women with a more extensive family history, and has not been studied in women younger than 35. The International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) Risk Evaluation Tool (https://ibis-risk-calculator.magview.com/), commonly referred to as the Tyrer-Cuzick model, incorporates second-degree relatives into the prediction model—although women may not know their full family history. Both the IBIS and the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model (https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/intro.htm) include breast density in the prediction algorithm. The choice of tool depends on clinician comfort and individual patient risk factors. There is no evidence that one model is better than another.10-12

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Ms. P’s clinician starts with an assessment using the Gail model. However, when the result comes back with average risk, the clinician decides to follow up with the Tyrer-Cuzick model in order to incorporate Ms. P’s multiple second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer. (The BCSC model was not used because it only includes first-degree relatives.)

Genetic testing

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend genetic testing if a woman has a first- or second-degree relative with pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, male breast cancer, breast cancer at age 45 or younger, 2 or more breast cancers in a single person, 2 or more people on the same side of the family with at least 1 diagnosed at age 50 or younger, or any relative with ovarian cancer (see TABLE 3).7 Before ordering genetic testing, it is useful to refer the patient to a genetic counselor for a thorough discussion of options.

Results of genetic testing may include high-risk variants, moderate-risk variants, and variants of unknown significance (VUS), or be negative for any variants. High-risk variants for breast cancer include BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and cancer syndrome variants such as TP53, PTEN, STK11, and CDH1.5,6,9,13-15 These high-risk variants confer sufficient risk that women with these mutations are automatically categorized in the high-risk group. It is estimated that high-risk variants account for only 25% of the genetic risk for breast cancer.16

BRCA1/2 and PTEN mutations confer greater than 80% lifetime risk, while other high-risk variants such as TP53, CDH1, and STK11 confer risks between 25% and 40%. These variants are also associated with cancers of other organs, depending on the mutation.17

Moderate-risk variants—ATM and CHEK2—do not confer sufficient risk to elevate women into the high-risk group. However, they do qualify these intermediate-risk women to participate in a specialized management strategy.5,9,13,18

VUS are those for which the associated risk is unclear, but more research may be done to categorize the risk.9 The clinical management of women with VUS usually entails close monitoring.

In an effort to better characterize breast cancer risk using a combination of pathogenic variants found in broad multi-gene cancer predisposition panels, researchers have developed a method to combine risks in a “polygenic risk score” (PRS) that can be used to counsel women (see “What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?” on page 203).19-21PRS predicts an additional 18% of genetic risk in women of European descent.21

SIDEBAR

What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?

- A polygenic risk score (PRS) is a mathematical method to combine results from a variety of different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; ie, single base pair variants) into a prediction tool that can estimate a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer.

- A PRS may be most accurate in determining risk for women with intermediate pathogenic variants, such as ATM and CHEK2. 19,20

- PRS has not been studied in non-White women.21

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Using the assessment results, the clinician talks to Ms. P about her lifetime risk for breast cancer. The Gail model indicates her lifetime risk is 13.3%, just slightly higher than the average (12.5%), and her 5-year risk is 0.5% (average, 0.4%). The IBIS or Tyrer-Cuzick model, which takes into account her second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer and her Ashkenazi ethnicity (which confers increased risk due to elevated risk of BRCA mutations), predicts her lifetime risk of breast cancer to be 20.4%. This categorizes Ms. P as high risk.

Enhanced screening recommendations for women at high risk

TABLE 48,13,22 summarizes screening recommendations for women deemed to be at high risk for breast cancer. The American Cancer Society (ACS), NCCN, and the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommend that women with at least a 20% lifetime risk have yearly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mammography (staggered so that the patient has 1 test every 6 months) starting 10 years before the age of onset for the youngest affected relative but not before age 30.8 For carriers of high-risk (as well as intermediate-risk) genes, NCCN recommends annual MRI screening starting at age 40.13BRCA1/2 screening includes annual MRI starting at age 25 and annual mammography every 6 months starting at age 30.22 Clinicians should counsel women with moderate risk factors (elevated breast density; personal history of ADH, LCIS, or DCIS) about the potential risks and benefits of enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis.

Risk-reduction strategies

Chemoprophylaxis

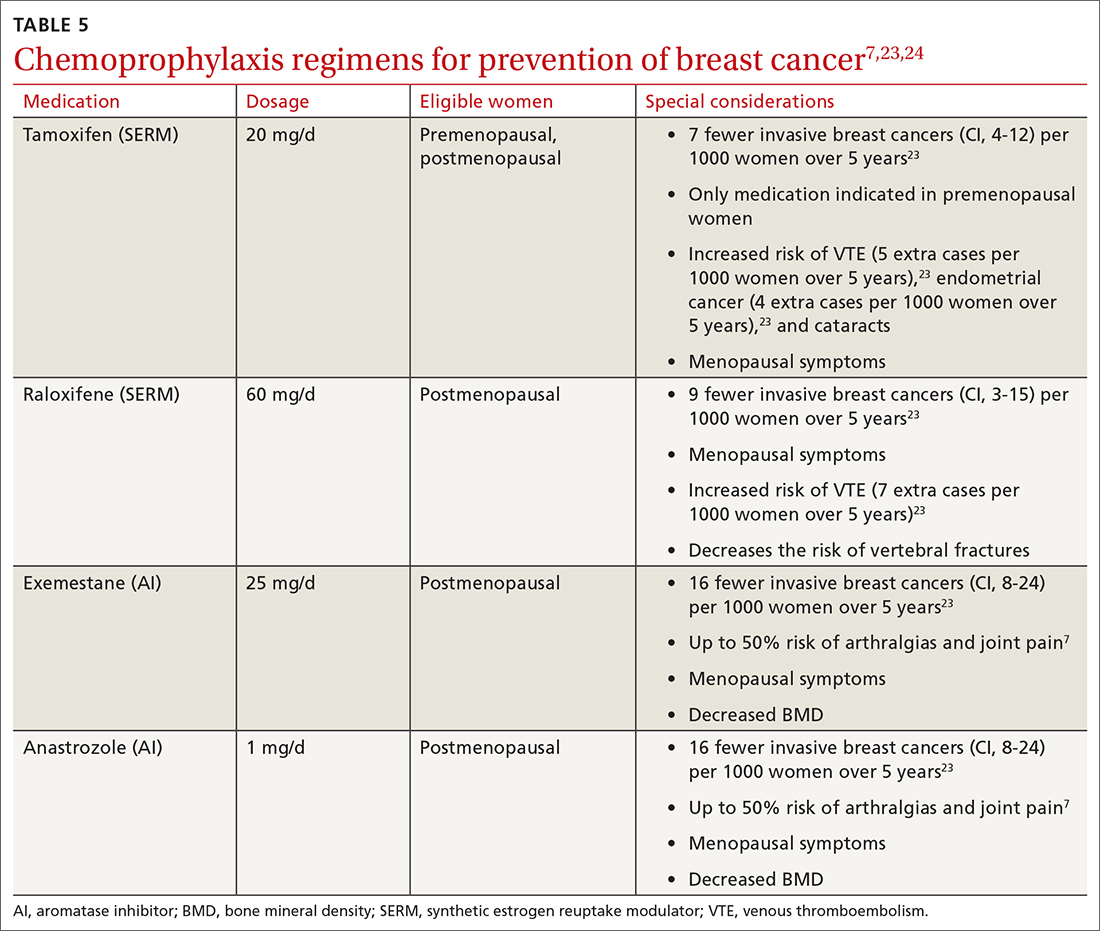

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women at increased risk for breast cancer consider chemoprophylaxis (B recommendation)23 based on convincing evidence that 5 years of treatment with either a synthetic estrogen reuptake modulator (SERM) or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) decreases the incidence of estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. (See TABLE 57,23,24 for absolute risk reduction.) There is no benefit for chemoprophylaxis in women at average risk (D recommendation).23 It is unclear whether chemoprophylaxis is indicated in women with moderate increased risk (ie, who do not meet the 20% lifetime risk criteria). Chemoprophylaxis may not be effective in women with BRCA1 mutations, as they often develop triple-negative breast cancers.

Accurate risk assessment and shared decision-making enable the clinician and patient to discuss the potential risks and benefits of chemoprophylaxis.7,24 The USPSTF did not find that any 1 risk prediction tool was better than another to identify women who should be counseled about chemoprophylaxis. Clinicians should counsel all women taking AIs about optimizing bone health with adequate calcium and vitamin D intake and routine bone density tests.

Surgical risk reduction

The NCCN guidelines state that risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy is reserved for individuals with high-risk gene variants and individuals with prior chest radiation between ages 10 and 30.25 NCCN also recommends discussing risk-reducing mastectomy with all women with BRCA mutations.22

Bilateral mastectomy is the most effective method to reduce breast cancer risk and should be discussed after age 25 in women with BRCA mutations and at least 8 years after chest radiation is completed.26 There is a reduction in breast cancer incidence of 90%.25 Breast imaging for screening (mammography or MRI) is not indicated after risk-reducing mastectomy. However, clinical breast examinations of the surgical site are important, because there is a small risk of developing breast cancer in that area.26

Risk-reducing oophorectomy is the standard of care for women with BRCA mutations to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. It can also reduce the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations.27

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Based on her risk assessment results, family history, and genetic heritage, Ms. P qualifies for referral to a genetic counselor for discussion of BRCA testing. The clinician discusses adding annual MRI to Ms. P’s breast cancer screening regimen, based on ACS, NCCN, and ACR recommendations, due to her 20.4% lifetime risk. Discussion of whether and when to start chemoprophylaxis is typically based on breast cancer risk, projected benefit, and the potential impact of medication adverse effects. A high-risk woman is eligible for 5 years of chemoprophylaxis (tamoxifen if premenopausal) based on her lifetime risk. The clinician discusses timing with Ms. P, and even though she is finished with childbearing, she would like to wait until she is age 45, which is before the age at which her aunt was given a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Conclusion

Primary care clinicians are well positioned to identify women with an elevated risk of breast cancer and refer them for enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis (see ALGORITHM). Shared decision-making with the inclusion of patient decision aids (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsearch.php?criteria=breast+cancer) about genetic testing, chemoprophylaxis, and prophylactic mastectomy or oophorectomy may help women at intermediate or high risk of breast cancer feel empowered to make decisions about their breast—and overall—health.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected]

Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer in women in the United States; it is estimated that there will be 287,850 new cases of breast cancer in the United States during 2022 with 43,250 deaths.1 Lives are extended and saved every day because of a robust arsenal of treatments and interventions available to those who have been given a diagnosis of breast cancer. And, of course, lives are also extended and saved when we identify women at risk and provide early interventions. But in busy offices where time is short and there are competing demands on our time, proper assessment of a woman’s risk of breast cancer does not always happen. As a result, women with a higher risk of breast cancer may not be getting appropriate management.2,3

Familiarizing yourself with several risk-assessment tools and knowing when genetic testing is needed can make a big difference. Knowing the timing of mammograms and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for women deemed to be at high risk is also key. The following review employs a case-based approach (with an accompanying ALGORITHM) to illustrate how best to identify women who are at heightened risk of breast cancer and maximize their care. We also discuss the chemoprophylaxis regimens that may be used for those at increased risk.

CASE

Rachel P, age 37, presents to establish care. She has an Ashkenazi Jewish background and wonders if she should start doing breast cancer screening before age 40. She has 2 children, ages 4 years and 2 years. Her maternal aunt had unilateral breast cancer at age 54, and her maternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer at age 65.

Risk assessment

The risk assessment process (see ALGORITHM) must start with either the clinician or the patient initiating the discussion about breast cancer risk. The clinician may initiate the discussion with a new patient or at an annual physical examination. The patient may start the discussion because they are experiencing new breast symptoms, have anxiety about developing breast cancer, or have a family member with a new cancer diagnosis.

Risk factors. There are single factors that convey enough risk to automatically designate the patient as high risk (see TABLE 14-9). These factors include having a history of chest radiation between the ages of 10 and 30, a history of breast biopsy with either lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), past breast and/or ovarian cancer, and either a family or personal history of a high penetrant genetic variant for breast cancer.4-9

In women with previous chest radiation, breast cancer risk correlates with the total dose of radiation.5 For women with a personal history of breast cancer, the younger the age at diagnosis, the higher the risk of contralateral breast cancer.5 Precancerous changes such as ADH, LCIS, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) also confer moderate increases in risk. Women with these diagnoses will commonly have follow-up with specialists.

Risk assessment tools. There are several models available to assess a woman’s breast cancer risk (see TABLE 210-12). The Gail model (https://bcrisktool.cancer.gov/) is the oldest, quickest, and most widely known. However, the Gail model only accounts for first-degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer, may underpredict risk in women with a more extensive family history, and has not been studied in women younger than 35. The International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) Risk Evaluation Tool (https://ibis-risk-calculator.magview.com/), commonly referred to as the Tyrer-Cuzick model, incorporates second-degree relatives into the prediction model—although women may not know their full family history. Both the IBIS and the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model (https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/intro.htm) include breast density in the prediction algorithm. The choice of tool depends on clinician comfort and individual patient risk factors. There is no evidence that one model is better than another.10-12

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Ms. P’s clinician starts with an assessment using the Gail model. However, when the result comes back with average risk, the clinician decides to follow up with the Tyrer-Cuzick model in order to incorporate Ms. P’s multiple second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer. (The BCSC model was not used because it only includes first-degree relatives.)

Genetic testing

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend genetic testing if a woman has a first- or second-degree relative with pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, male breast cancer, breast cancer at age 45 or younger, 2 or more breast cancers in a single person, 2 or more people on the same side of the family with at least 1 diagnosed at age 50 or younger, or any relative with ovarian cancer (see TABLE 3).7 Before ordering genetic testing, it is useful to refer the patient to a genetic counselor for a thorough discussion of options.

Results of genetic testing may include high-risk variants, moderate-risk variants, and variants of unknown significance (VUS), or be negative for any variants. High-risk variants for breast cancer include BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and cancer syndrome variants such as TP53, PTEN, STK11, and CDH1.5,6,9,13-15 These high-risk variants confer sufficient risk that women with these mutations are automatically categorized in the high-risk group. It is estimated that high-risk variants account for only 25% of the genetic risk for breast cancer.16

BRCA1/2 and PTEN mutations confer greater than 80% lifetime risk, while other high-risk variants such as TP53, CDH1, and STK11 confer risks between 25% and 40%. These variants are also associated with cancers of other organs, depending on the mutation.17

Moderate-risk variants—ATM and CHEK2—do not confer sufficient risk to elevate women into the high-risk group. However, they do qualify these intermediate-risk women to participate in a specialized management strategy.5,9,13,18

VUS are those for which the associated risk is unclear, but more research may be done to categorize the risk.9 The clinical management of women with VUS usually entails close monitoring.

In an effort to better characterize breast cancer risk using a combination of pathogenic variants found in broad multi-gene cancer predisposition panels, researchers have developed a method to combine risks in a “polygenic risk score” (PRS) that can be used to counsel women (see “What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?” on page 203).19-21PRS predicts an additional 18% of genetic risk in women of European descent.21

SIDEBAR

What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?

- A polygenic risk score (PRS) is a mathematical method to combine results from a variety of different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; ie, single base pair variants) into a prediction tool that can estimate a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer.

- A PRS may be most accurate in determining risk for women with intermediate pathogenic variants, such as ATM and CHEK2. 19,20

- PRS has not been studied in non-White women.21

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Using the assessment results, the clinician talks to Ms. P about her lifetime risk for breast cancer. The Gail model indicates her lifetime risk is 13.3%, just slightly higher than the average (12.5%), and her 5-year risk is 0.5% (average, 0.4%). The IBIS or Tyrer-Cuzick model, which takes into account her second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer and her Ashkenazi ethnicity (which confers increased risk due to elevated risk of BRCA mutations), predicts her lifetime risk of breast cancer to be 20.4%. This categorizes Ms. P as high risk.

Enhanced screening recommendations for women at high risk

TABLE 48,13,22 summarizes screening recommendations for women deemed to be at high risk for breast cancer. The American Cancer Society (ACS), NCCN, and the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommend that women with at least a 20% lifetime risk have yearly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mammography (staggered so that the patient has 1 test every 6 months) starting 10 years before the age of onset for the youngest affected relative but not before age 30.8 For carriers of high-risk (as well as intermediate-risk) genes, NCCN recommends annual MRI screening starting at age 40.13BRCA1/2 screening includes annual MRI starting at age 25 and annual mammography every 6 months starting at age 30.22 Clinicians should counsel women with moderate risk factors (elevated breast density; personal history of ADH, LCIS, or DCIS) about the potential risks and benefits of enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis.

Risk-reduction strategies

Chemoprophylaxis

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women at increased risk for breast cancer consider chemoprophylaxis (B recommendation)23 based on convincing evidence that 5 years of treatment with either a synthetic estrogen reuptake modulator (SERM) or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) decreases the incidence of estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. (See TABLE 57,23,24 for absolute risk reduction.) There is no benefit for chemoprophylaxis in women at average risk (D recommendation).23 It is unclear whether chemoprophylaxis is indicated in women with moderate increased risk (ie, who do not meet the 20% lifetime risk criteria). Chemoprophylaxis may not be effective in women with BRCA1 mutations, as they often develop triple-negative breast cancers.

Accurate risk assessment and shared decision-making enable the clinician and patient to discuss the potential risks and benefits of chemoprophylaxis.7,24 The USPSTF did not find that any 1 risk prediction tool was better than another to identify women who should be counseled about chemoprophylaxis. Clinicians should counsel all women taking AIs about optimizing bone health with adequate calcium and vitamin D intake and routine bone density tests.

Surgical risk reduction

The NCCN guidelines state that risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy is reserved for individuals with high-risk gene variants and individuals with prior chest radiation between ages 10 and 30.25 NCCN also recommends discussing risk-reducing mastectomy with all women with BRCA mutations.22

Bilateral mastectomy is the most effective method to reduce breast cancer risk and should be discussed after age 25 in women with BRCA mutations and at least 8 years after chest radiation is completed.26 There is a reduction in breast cancer incidence of 90%.25 Breast imaging for screening (mammography or MRI) is not indicated after risk-reducing mastectomy. However, clinical breast examinations of the surgical site are important, because there is a small risk of developing breast cancer in that area.26

Risk-reducing oophorectomy is the standard of care for women with BRCA mutations to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. It can also reduce the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations.27

Continue to: CASE

CASE

Based on her risk assessment results, family history, and genetic heritage, Ms. P qualifies for referral to a genetic counselor for discussion of BRCA testing. The clinician discusses adding annual MRI to Ms. P’s breast cancer screening regimen, based on ACS, NCCN, and ACR recommendations, due to her 20.4% lifetime risk. Discussion of whether and when to start chemoprophylaxis is typically based on breast cancer risk, projected benefit, and the potential impact of medication adverse effects. A high-risk woman is eligible for 5 years of chemoprophylaxis (tamoxifen if premenopausal) based on her lifetime risk. The clinician discusses timing with Ms. P, and even though she is finished with childbearing, she would like to wait until she is age 45, which is before the age at which her aunt was given a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Conclusion

Primary care clinicians are well positioned to identify women with an elevated risk of breast cancer and refer them for enhanced screening and chemoprophylaxis (see ALGORITHM). Shared decision-making with the inclusion of patient decision aids (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsearch.php?criteria=breast+cancer) about genetic testing, chemoprophylaxis, and prophylactic mastectomy or oophorectomy may help women at intermediate or high risk of breast cancer feel empowered to make decisions about their breast—and overall—health.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

2. Guerra CE, Sherman M, Armstrong K. Diffusion of breast cancer risk assessment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:272-279. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.03.080153

3. Hamilton JG, Abdiwahab E, Edwards HM, et al. Primary care providers’ cancer genetic testing-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication behaviors: a systematic review and research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:315-324. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4

4. Eden KB, Ivlev I, Bensching KL, et al. Use of an online breast cancer risk assessment and patient decision aid in primary care practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:763-769. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8143

5. Kleibl Z, Kristensen VN. Women at high risk of breast cancer: molecular characteristics, clinical presentation and management. Breast. 2016;28:136-44. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.05.006

6. Sciaraffa T, Guido B, Khan SA, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment and management programs: a practical guide. Breast J. 2020;26:1556-1564. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13967

7. Farkas A, Vanderberg R, Merriam S, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention: a practical guide for the primary care provider. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:46-56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7643

8. McClintock AH, Golob AL, Laya MB. Breast cancer risk assessment: a step-wise approach for primary care providers on the front lines of shared decision making. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1268-1275. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.017

9. Catana A, Apostu AP, Antemie RG. Multi gene panel testing for hereditary breast cancer - is it ready to be used? Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:220-225. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1083

10. Barke LD, Freivogel ME. Breast cancer risk assessment models and high-risk screening. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55:457-474. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.12.013

11. Amir E, Freedman OC, Seruga B, et al. Assessing women at high risk of breast cancer: a review of risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:680-91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq088

12. Kim G, Bahl M. Assessing risk of breast cancer: a review of risk prediction models. J Breast Imaging. 2021;3:144-155. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbab001

13. Narod SA. Which genes for hereditary breast cancer? N Engl J Med. 2021;384:471-473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2035083

14. Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1190-1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424

15. Obeid EI, Hall MJ, Daly MB. Multigene panel testing and breast cancer risk: is it time to scale down? JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1176-1177. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0342

16. Michailidou K, Lindström S, Dennis J, et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551:92-94. doi: 10.1038/nature24284

17. Shiovitz S, Korde LA. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1291-1299. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv022

18. Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:440-451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005936

19. Gao C, Polley EC, Hart SN, et al. Risk of breast cancer among carriers of pathogenic variants in breast cancer predisposition genes varies by polygenic risk score. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2564-2573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01992

20. Gallagher S, Hughes E, Wagner S, et al. Association of a polygenic risk score with breast cancer among women carriers of high- and moderate-risk breast cancer genes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208501. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8501

21. Yanes T, Young MA, Meiser B, et al. Clinical applications of polygenic breast cancer risk: a critical review and perspectives of an emerging field. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01260-3

22. Schrager S, Torell E, Ledford K, et al. Managing a woman with BRCA mutations? Shared decision-making is key. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:237-243

23. US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11885

24. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3230-3235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

25. Britt KL, Cuzick J, Phillips KA. Key steps for effective breast cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:417-436. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0266-x

26. Jatoi I, Kemp Z. Risk-reducing mastectomy. JAMA. 2021;325:1781-1782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22414

27. Choi Y, Terry MB, Daly MB, et al. Association of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy with breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:585-592. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7995

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

2. Guerra CE, Sherman M, Armstrong K. Diffusion of breast cancer risk assessment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:272-279. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.03.080153

3. Hamilton JG, Abdiwahab E, Edwards HM, et al. Primary care providers’ cancer genetic testing-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication behaviors: a systematic review and research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:315-324. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4

4. Eden KB, Ivlev I, Bensching KL, et al. Use of an online breast cancer risk assessment and patient decision aid in primary care practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:763-769. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8143

5. Kleibl Z, Kristensen VN. Women at high risk of breast cancer: molecular characteristics, clinical presentation and management. Breast. 2016;28:136-44. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.05.006

6. Sciaraffa T, Guido B, Khan SA, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment and management programs: a practical guide. Breast J. 2020;26:1556-1564. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13967

7. Farkas A, Vanderberg R, Merriam S, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention: a practical guide for the primary care provider. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29:46-56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7643

8. McClintock AH, Golob AL, Laya MB. Breast cancer risk assessment: a step-wise approach for primary care providers on the front lines of shared decision making. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1268-1275. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.017

9. Catana A, Apostu AP, Antemie RG. Multi gene panel testing for hereditary breast cancer - is it ready to be used? Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:220-225. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1083

10. Barke LD, Freivogel ME. Breast cancer risk assessment models and high-risk screening. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55:457-474. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.12.013

11. Amir E, Freedman OC, Seruga B, et al. Assessing women at high risk of breast cancer: a review of risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:680-91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq088

12. Kim G, Bahl M. Assessing risk of breast cancer: a review of risk prediction models. J Breast Imaging. 2021;3:144-155. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbab001

13. Narod SA. Which genes for hereditary breast cancer? N Engl J Med. 2021;384:471-473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2035083

14. Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1190-1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424

15. Obeid EI, Hall MJ, Daly MB. Multigene panel testing and breast cancer risk: is it time to scale down? JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1176-1177. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0342

16. Michailidou K, Lindström S, Dennis J, et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551:92-94. doi: 10.1038/nature24284

17. Shiovitz S, Korde LA. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1291-1299. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv022

18. Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:440-451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005936

19. Gao C, Polley EC, Hart SN, et al. Risk of breast cancer among carriers of pathogenic variants in breast cancer predisposition genes varies by polygenic risk score. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2564-2573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01992

20. Gallagher S, Hughes E, Wagner S, et al. Association of a polygenic risk score with breast cancer among women carriers of high- and moderate-risk breast cancer genes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208501. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8501

21. Yanes T, Young MA, Meiser B, et al. Clinical applications of polygenic breast cancer risk: a critical review and perspectives of an emerging field. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01260-3

22. Schrager S, Torell E, Ledford K, et al. Managing a woman with BRCA mutations? Shared decision-making is key. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:237-243

23. US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11885

24. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3230-3235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

25. Britt KL, Cuzick J, Phillips KA. Key steps for effective breast cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:417-436. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0266-x

26. Jatoi I, Kemp Z. Risk-reducing mastectomy. JAMA. 2021;325:1781-1782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22414

27. Choi Y, Terry MB, Daly MB, et al. Association of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy with breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:585-592. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7995

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Assess breast cancer risk in all women starting at age 35. C

› Perform enhanced screening in all women with a lifetime risk of breast cancer > 20%. A

› Discuss chemoprevention for all women at elevated risk for breast cancer. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Double morning-after pill dose for women with obesity not effective

Emergency contraception is more likely to fail in women with obesity, but simply doubling the dose of levonorgestrel (LNG)-based contraception does not appear to be effective according to the results of a randomized, controlled trial.

Alison B. Edelman, MD, MPH, of the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, led the study published online in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers included healthy women ages 18-35 with regular menstrual cycles, body mass index (BMI) higher than 30 kg/m2, and weight at least 176 pounds in a randomized study.

After confirming ovulation, researchers monitored participants with transvaginal ultrasonography and blood sampling for progesterone, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol every other day until a dominant follicle 15 mm or greater was seen.

At that point the women received either LNG 1.5 mg or 3 mg and returned for daily monitoring up to 7 days.

Emergency contraception with LNG works by preventing the luteinizing hormone surge, blocking follicle rupture. The researchers had hypothesized that women with obesity might not be getting enough LNG to block the surge after oral dosing.

Previous trials had shown women with obesity had a fourfold higher risk of pregnancy, compared with women with normal BMI taking emergency contraception.

The primary outcome in this trial was whether women had follicle rupture 5 days after dosing.

The authors wrote: “The study had 80% power to detect a 30% difference in the proportion of cycles with at least a 5-day delay in follicle rupture (50% decrease).”

A total of 70 women completed study procedures. The two groups (35 women in each) had similar demographics (mean age, 28 years; BMI, 38).

No differences found between groups

“We found no difference between groups in the proportion of participants without follicle rupture,” the researchers wrote.

More than 5 days after dosing, 51.4% in the lower-dose group did not experience follicle rupture. In the double-dose group 68.6% did not experience rupture but the difference was not significant (P = .14).

Among participants with follicle rupture before 5 days, the time to rupture – the secondary endpoint – also did not differ between groups.

The researchers concluded that more research on the failures of hormonal emergency contraception in women with obesity is needed.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, distinguished professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview that the study was well designed and the results “form a strong basis for clinical recommendations.”

“Providers should not recommend a higher dose of LNG emergency contraception for patients who are overweight or obese, but rather should counsel patients on the superior effectiveness of ulipristal acetate for those seeking oral emergency contraception as well as the longer time period after unprotected sex – 5 days – that ulipristal maintains its effectiveness.”

“Providers should also counsel patients on the most effective emergency contraception methods, the copper or LNG intrauterine device,” she said.

She said the unique study design of a pharmacodynamic randomized controlled trial adds weight to the findings.

She and the authors noted a limitation is the use of a surrogate outcome, ovulation delay, for ethical and feasibility reasons, instead of the outcome of interest, pregnancy.

The trial was conducted at Oregon Health & Science University and Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, from June 2017 to February 2021.

Study enrollees were compensated for their time. They were required not to be at risk for pregnancy (abstinent or using a nonhormonal method of contraception).

Dr. Edelman reported receiving honoraria and travel reimbursement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the World Health Organization, and Gynuity for committee activities and honoraria for peer review from the Karolinska Institute. She receives royalties from UpToDate. Several coauthors have received payments for consulting from multiple pharmaceutical companies. These companies and organizations may have a commercial or financial interest in the results of this research and technology. Another was involved in this study as a private consultant and is employed by Gilead Sciences, which was not involved in this research.

Emergency contraception is more likely to fail in women with obesity, but simply doubling the dose of levonorgestrel (LNG)-based contraception does not appear to be effective according to the results of a randomized, controlled trial.

Alison B. Edelman, MD, MPH, of the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, led the study published online in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers included healthy women ages 18-35 with regular menstrual cycles, body mass index (BMI) higher than 30 kg/m2, and weight at least 176 pounds in a randomized study.

After confirming ovulation, researchers monitored participants with transvaginal ultrasonography and blood sampling for progesterone, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol every other day until a dominant follicle 15 mm or greater was seen.

At that point the women received either LNG 1.5 mg or 3 mg and returned for daily monitoring up to 7 days.

Emergency contraception with LNG works by preventing the luteinizing hormone surge, blocking follicle rupture. The researchers had hypothesized that women with obesity might not be getting enough LNG to block the surge after oral dosing.

Previous trials had shown women with obesity had a fourfold higher risk of pregnancy, compared with women with normal BMI taking emergency contraception.

The primary outcome in this trial was whether women had follicle rupture 5 days after dosing.

The authors wrote: “The study had 80% power to detect a 30% difference in the proportion of cycles with at least a 5-day delay in follicle rupture (50% decrease).”

A total of 70 women completed study procedures. The two groups (35 women in each) had similar demographics (mean age, 28 years; BMI, 38).

No differences found between groups

“We found no difference between groups in the proportion of participants without follicle rupture,” the researchers wrote.