User login

Poor outcomes seen after carotid intervention non-ST-elevation MI

HONOLULU – Just 1% of patients experienced a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction following carotid-artery stenting or endarterectomy in a retrospective, nationally representative analysis of more than 1 million patients.

When it did occur, however, NSTEMI significantly increased periprocedural neurologic and cardiac complications, inpatient mortality, disability, and resource utilization – adding on average a full 10 days to hospital length of stay and nearly $85,000 in hospital charges, Dr. Amir Khan said during a plenary session at the International Stroke Conference. Dr. Khan is scheduled to present the study results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in San Diego on March 20.

He observed that postoperative evaluation for MI varied in the data set, as it does nationally, but that post hoc analyses from the POISE (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation) trial revealed that 65% of patients with an MI after noncardiac surgery did not have ischemic symptoms (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:523-8).

"So, we know that hospitals that don’t have active surveillance regimens for non-STEMI will miss a fair amount of this," said Dr. Khan, an endovascular surgical neuroradiology fellow at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The majority of perioperative MI is NSTEMI. While few studies have parsed out MI types, the SAPPHIRE (Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy) trial showed that 80% of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) patients with periprocedural MI and all carotid angioplasty or stenting (CAS) patients with periprocedural MI were NSTEMI (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1493-1501).

In an effort to assess the frequency of periprocedural NSTEMI following CEA or CAS in practice and its relationship with outcomes, the researchers used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all adult patients who underwent CEA or CAS from 2002 to 2009. From this, hospital-weighted national estimates were generated using Healthcare Utilization Project algorithms.

Overall, 11,341 patients (1%) experienced an NSTEMI and 1,072,347 did not; 92% of all patients underwent endarterectomy.

Age, gender, and racial distribution were roughly similar between groups, although patients with NSTEMI had significantly higher baseline rates of atrial fibrillation (24% vs. 8%), heart failure (24% vs. 6.5%) and chronic renal insufficiency (16% vs. 5%), Dr. Khan noted.

In terms of health care usage, rates were slightly higher among NSTEMI patients for inpatient diagnostic cerebral angiography (19% vs. 13.5%), gastrostomy (3% vs. 0.4%), and postprocedure mechanical ventilation (0.5% vs. 0.3%; all P less than .0001).

Blood transfusions were conspicuously higher in those with NSTEMI at 20% vs. 3% in those without, he said. The average length of stay also jumped with NSTEMI from 2.8 days to 12.2 days, pushing hospital charges from an average of $29,160 to $113,317 (all P less than .0001).

Neurologic complications were seen in 6% of patients with NSTEMI vs. 1.4% without, while cardiac complications occurred in 31% vs. 1.5%. In addition, 31% of NSTEMI patients were moderately or severely disabled at discharge vs. just 6% without NSTEMI (all P less than .0001), Dr. Khan reported at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In-hospital mortality was 6% in the NSTEMI group and 0.5% in the group without. The composite endpoint of cardiac or neurologic complication and/or death was reached by 38% vs. 3% (both P less than .0001).

When these numbers were plugged into a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, gender, and comorbidities, the odds ratios for patients with NSTEMI were 3.6 for neurologic complications, 23.2 for cardiac complications, 8.6 for in-hospital mortality, 14.6 for the composite end point, and 5.5 for moderate to severe disability (all P less than .0001), he said.

During a discussion following the presentation, an audience member expressed concern about the complication rates, rising to say, "Often we make decisions about stroke treatment based only on what’s good for the brain. Well there’s no point in making the brain better if the person can have a heart attack and die of some other complications, and I really think this [study] emphasizes that."

Dr. Khan replied, "I totally agree and I think that is one of the take-home messages here ... "

Dr. Khan and his coauthors reported no disclosures.

HONOLULU – Just 1% of patients experienced a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction following carotid-artery stenting or endarterectomy in a retrospective, nationally representative analysis of more than 1 million patients.

When it did occur, however, NSTEMI significantly increased periprocedural neurologic and cardiac complications, inpatient mortality, disability, and resource utilization – adding on average a full 10 days to hospital length of stay and nearly $85,000 in hospital charges, Dr. Amir Khan said during a plenary session at the International Stroke Conference. Dr. Khan is scheduled to present the study results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in San Diego on March 20.

He observed that postoperative evaluation for MI varied in the data set, as it does nationally, but that post hoc analyses from the POISE (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation) trial revealed that 65% of patients with an MI after noncardiac surgery did not have ischemic symptoms (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:523-8).

"So, we know that hospitals that don’t have active surveillance regimens for non-STEMI will miss a fair amount of this," said Dr. Khan, an endovascular surgical neuroradiology fellow at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The majority of perioperative MI is NSTEMI. While few studies have parsed out MI types, the SAPPHIRE (Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy) trial showed that 80% of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) patients with periprocedural MI and all carotid angioplasty or stenting (CAS) patients with periprocedural MI were NSTEMI (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1493-1501).

In an effort to assess the frequency of periprocedural NSTEMI following CEA or CAS in practice and its relationship with outcomes, the researchers used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all adult patients who underwent CEA or CAS from 2002 to 2009. From this, hospital-weighted national estimates were generated using Healthcare Utilization Project algorithms.

Overall, 11,341 patients (1%) experienced an NSTEMI and 1,072,347 did not; 92% of all patients underwent endarterectomy.

Age, gender, and racial distribution were roughly similar between groups, although patients with NSTEMI had significantly higher baseline rates of atrial fibrillation (24% vs. 8%), heart failure (24% vs. 6.5%) and chronic renal insufficiency (16% vs. 5%), Dr. Khan noted.

In terms of health care usage, rates were slightly higher among NSTEMI patients for inpatient diagnostic cerebral angiography (19% vs. 13.5%), gastrostomy (3% vs. 0.4%), and postprocedure mechanical ventilation (0.5% vs. 0.3%; all P less than .0001).

Blood transfusions were conspicuously higher in those with NSTEMI at 20% vs. 3% in those without, he said. The average length of stay also jumped with NSTEMI from 2.8 days to 12.2 days, pushing hospital charges from an average of $29,160 to $113,317 (all P less than .0001).

Neurologic complications were seen in 6% of patients with NSTEMI vs. 1.4% without, while cardiac complications occurred in 31% vs. 1.5%. In addition, 31% of NSTEMI patients were moderately or severely disabled at discharge vs. just 6% without NSTEMI (all P less than .0001), Dr. Khan reported at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In-hospital mortality was 6% in the NSTEMI group and 0.5% in the group without. The composite endpoint of cardiac or neurologic complication and/or death was reached by 38% vs. 3% (both P less than .0001).

When these numbers were plugged into a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, gender, and comorbidities, the odds ratios for patients with NSTEMI were 3.6 for neurologic complications, 23.2 for cardiac complications, 8.6 for in-hospital mortality, 14.6 for the composite end point, and 5.5 for moderate to severe disability (all P less than .0001), he said.

During a discussion following the presentation, an audience member expressed concern about the complication rates, rising to say, "Often we make decisions about stroke treatment based only on what’s good for the brain. Well there’s no point in making the brain better if the person can have a heart attack and die of some other complications, and I really think this [study] emphasizes that."

Dr. Khan replied, "I totally agree and I think that is one of the take-home messages here ... "

Dr. Khan and his coauthors reported no disclosures.

HONOLULU – Just 1% of patients experienced a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction following carotid-artery stenting or endarterectomy in a retrospective, nationally representative analysis of more than 1 million patients.

When it did occur, however, NSTEMI significantly increased periprocedural neurologic and cardiac complications, inpatient mortality, disability, and resource utilization – adding on average a full 10 days to hospital length of stay and nearly $85,000 in hospital charges, Dr. Amir Khan said during a plenary session at the International Stroke Conference. Dr. Khan is scheduled to present the study results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in San Diego on March 20.

He observed that postoperative evaluation for MI varied in the data set, as it does nationally, but that post hoc analyses from the POISE (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation) trial revealed that 65% of patients with an MI after noncardiac surgery did not have ischemic symptoms (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:523-8).

"So, we know that hospitals that don’t have active surveillance regimens for non-STEMI will miss a fair amount of this," said Dr. Khan, an endovascular surgical neuroradiology fellow at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The majority of perioperative MI is NSTEMI. While few studies have parsed out MI types, the SAPPHIRE (Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy) trial showed that 80% of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) patients with periprocedural MI and all carotid angioplasty or stenting (CAS) patients with periprocedural MI were NSTEMI (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1493-1501).

In an effort to assess the frequency of periprocedural NSTEMI following CEA or CAS in practice and its relationship with outcomes, the researchers used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all adult patients who underwent CEA or CAS from 2002 to 2009. From this, hospital-weighted national estimates were generated using Healthcare Utilization Project algorithms.

Overall, 11,341 patients (1%) experienced an NSTEMI and 1,072,347 did not; 92% of all patients underwent endarterectomy.

Age, gender, and racial distribution were roughly similar between groups, although patients with NSTEMI had significantly higher baseline rates of atrial fibrillation (24% vs. 8%), heart failure (24% vs. 6.5%) and chronic renal insufficiency (16% vs. 5%), Dr. Khan noted.

In terms of health care usage, rates were slightly higher among NSTEMI patients for inpatient diagnostic cerebral angiography (19% vs. 13.5%), gastrostomy (3% vs. 0.4%), and postprocedure mechanical ventilation (0.5% vs. 0.3%; all P less than .0001).

Blood transfusions were conspicuously higher in those with NSTEMI at 20% vs. 3% in those without, he said. The average length of stay also jumped with NSTEMI from 2.8 days to 12.2 days, pushing hospital charges from an average of $29,160 to $113,317 (all P less than .0001).

Neurologic complications were seen in 6% of patients with NSTEMI vs. 1.4% without, while cardiac complications occurred in 31% vs. 1.5%. In addition, 31% of NSTEMI patients were moderately or severely disabled at discharge vs. just 6% without NSTEMI (all P less than .0001), Dr. Khan reported at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In-hospital mortality was 6% in the NSTEMI group and 0.5% in the group without. The composite endpoint of cardiac or neurologic complication and/or death was reached by 38% vs. 3% (both P less than .0001).

When these numbers were plugged into a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, gender, and comorbidities, the odds ratios for patients with NSTEMI were 3.6 for neurologic complications, 23.2 for cardiac complications, 8.6 for in-hospital mortality, 14.6 for the composite end point, and 5.5 for moderate to severe disability (all P less than .0001), he said.

During a discussion following the presentation, an audience member expressed concern about the complication rates, rising to say, "Often we make decisions about stroke treatment based only on what’s good for the brain. Well there’s no point in making the brain better if the person can have a heart attack and die of some other complications, and I really think this [study] emphasizes that."

Dr. Khan replied, "I totally agree and I think that is one of the take-home messages here ... "

Dr. Khan and his coauthors reported no disclosures.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: The composite endpoint of cardiac or neurologic complication and/or death was reached by 38% of patients with NSTEMI vs. 3% of those without (P less than .0001).

Data Source: Retrospective cohort analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample of 2002-2009.

Disclosures: Dr. Khan and his coauthors reported no disclosures.

Sandwich technique bests coil embolization for complex AAA

MIAMI BEACH – Hypogastric artery endorevascularization using the sandwich technique was associated with fewer complications than was hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm with concomitant bilateral common iliac artery aneurysm in a series of 79 patients.

A total of 158 common iliac artery aneurysms were treated using either the same technique bilaterally or a different technique in each side. In the first group, 40 hypogastric artery endorevascularization procedures were performed using the sandwich technique, including 6 bilateral procedures. In the second group, 118 hypogastric artery exclusion procedures were performed using coil embolization followed by positioning of a limb extension to the external iliac artery, including 45 bilateral procedures, Dr. Armando C. Lobato reported at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy 2013.

At a mean of 37 months’ follow-up, permanent buttock claudication rates were significantly higher in group two (12.7% vs. 2.5%), as were late type II endoleak rates (15.5% vs. 2.5%), said Dr. Lobato of the Sao Paulo Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Institute, Beneficencia Portuguesa Hospital, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The technical success rate was 100% in both groups, and related mortality and postoperative aneurysm rupture rates did not differ significantly between the groups. Early mortality was 0% and 1.4% in groups one and two, respectively; late mortality was 0% and 2.8% in the groups, respectively; and the postoperative aneurysm rupture rate was 0% and 1.4% in the groups, respectively, he said.

Rates of iliac limb migration, late type IB endoleak, type III endoleak, iliac limb occlusion, and reintervention also were similar in the two groups.

On multivariate regression analysis, bilateral hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization was significantly associated with permanent buttock claudication and late type II endoleak, he noted.

The findings provide further validation of the sandwich technique, which was developed by Dr. Lobato to overcome anatomical and device-related constraints encountered during endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). The technique has shown promise in prior studies and earlier reports from Dr. Lobato’s case series.

Dr. Lobato reported having no disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Hypogastric artery endorevascularization using the sandwich technique was associated with fewer complications than was hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm with concomitant bilateral common iliac artery aneurysm in a series of 79 patients.

A total of 158 common iliac artery aneurysms were treated using either the same technique bilaterally or a different technique in each side. In the first group, 40 hypogastric artery endorevascularization procedures were performed using the sandwich technique, including 6 bilateral procedures. In the second group, 118 hypogastric artery exclusion procedures were performed using coil embolization followed by positioning of a limb extension to the external iliac artery, including 45 bilateral procedures, Dr. Armando C. Lobato reported at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy 2013.

At a mean of 37 months’ follow-up, permanent buttock claudication rates were significantly higher in group two (12.7% vs. 2.5%), as were late type II endoleak rates (15.5% vs. 2.5%), said Dr. Lobato of the Sao Paulo Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Institute, Beneficencia Portuguesa Hospital, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The technical success rate was 100% in both groups, and related mortality and postoperative aneurysm rupture rates did not differ significantly between the groups. Early mortality was 0% and 1.4% in groups one and two, respectively; late mortality was 0% and 2.8% in the groups, respectively; and the postoperative aneurysm rupture rate was 0% and 1.4% in the groups, respectively, he said.

Rates of iliac limb migration, late type IB endoleak, type III endoleak, iliac limb occlusion, and reintervention also were similar in the two groups.

On multivariate regression analysis, bilateral hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization was significantly associated with permanent buttock claudication and late type II endoleak, he noted.

The findings provide further validation of the sandwich technique, which was developed by Dr. Lobato to overcome anatomical and device-related constraints encountered during endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). The technique has shown promise in prior studies and earlier reports from Dr. Lobato’s case series.

Dr. Lobato reported having no disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Hypogastric artery endorevascularization using the sandwich technique was associated with fewer complications than was hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm with concomitant bilateral common iliac artery aneurysm in a series of 79 patients.

A total of 158 common iliac artery aneurysms were treated using either the same technique bilaterally or a different technique in each side. In the first group, 40 hypogastric artery endorevascularization procedures were performed using the sandwich technique, including 6 bilateral procedures. In the second group, 118 hypogastric artery exclusion procedures were performed using coil embolization followed by positioning of a limb extension to the external iliac artery, including 45 bilateral procedures, Dr. Armando C. Lobato reported at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy 2013.

At a mean of 37 months’ follow-up, permanent buttock claudication rates were significantly higher in group two (12.7% vs. 2.5%), as were late type II endoleak rates (15.5% vs. 2.5%), said Dr. Lobato of the Sao Paulo Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Institute, Beneficencia Portuguesa Hospital, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The technical success rate was 100% in both groups, and related mortality and postoperative aneurysm rupture rates did not differ significantly between the groups. Early mortality was 0% and 1.4% in groups one and two, respectively; late mortality was 0% and 2.8% in the groups, respectively; and the postoperative aneurysm rupture rate was 0% and 1.4% in the groups, respectively, he said.

Rates of iliac limb migration, late type IB endoleak, type III endoleak, iliac limb occlusion, and reintervention also were similar in the two groups.

On multivariate regression analysis, bilateral hypogastric artery exclusion by coil embolization was significantly associated with permanent buttock claudication and late type II endoleak, he noted.

The findings provide further validation of the sandwich technique, which was developed by Dr. Lobato to overcome anatomical and device-related constraints encountered during endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). The technique has shown promise in prior studies and earlier reports from Dr. Lobato’s case series.

Dr. Lobato reported having no disclosures.

AT ISET 2013

Major finding: Permanent buttock claudication rates were significantly higher in the coil group, compared with the sandwich group (12.7% vs. 2.5%), as were late type II endoleak rates (15.5% vs. 2.5%).

Data source: A case series involving 79 patients with a total of 158 common iliac artery aneurysms.

Disclosures: Dr. Lobato reported having no disclosures.

Hybrid CFV endovenectomy promising, but not for the faint at heart

CHICAGO – Common femoral endovenectomy with endoluminal iliac recanalization should be considered in patients with chronic post-thrombotic iliofemoral venous obstruction.

The procedure substantially reduces post-thrombotic syndrome morbidity and improves quality of life, although it "is not a procedure for the faint of heart," acknowledged Dr. Anthony Comerota, director of the Jobst Vascular Center at ProMedica Toledo (Ohio) Hospital.

Postthrombotic syndrome occurs in 30%-40% of all patients with a lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at 2 years, despite the use of anticoagulation. Postthrombotic syndrome can be particularly debilitating following an iliofemoral DVT if the common femoral vein (CFV) is badly obstructed or occluded, resulting in such poor quality of life that Dr. Comerota compared it with angina, cancer, and congestive heart failure.

Stenting and angioplasty are often successful in treating postthrombotic iliac vein occlusion, although the risk of stent occlusion is at least 3.8-fold higher in postthrombotic limbs if the stent is extended below the inguinal ligament, he noted.

Relative obstruction of the CFV also can persist after percutaneous intervention and compromise drainage from the profunda femoris vein. This mitigates the benefits of iliac vein recanalization and can actually worsen the patient’s post-thrombotic symptoms, Dr. Comerota said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

"It is crucial to open up the orifice of the profunda," he said. "One of the problems we’ve seen in patients referred to us is that, when the common femoral was stented and the stent takes that fibrous tissue and plasters it up against the orifice of the profunda, if there was any minimal drainage from the profunda, it will obliterate it and those patients got worse."

Having previously detailed the technical aspects of the procedure (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:129-35), Dr. Comerota highlighted outcomes of 14 patients and 16 limbs treated to date for severe post-thrombotic, iliofemoral/caval venous obstruction with CEAP (clinical severity, etiology, anatomy, pathophysiology) classification of C3-C6. The median duration of obstruction was nearly 7 years (range, 7 months to 25 years) and median follow-up 3 years (range, 5 months to 6 years). Two patients were lost to follow-up.

To date, one death occurred in a 52-year-old woman with multiple cardiovascular risk factors 9 days after discharge because of an acute myocardial infarction, Dr. Comerota said.

Three patients required surgical evacuation of wound hematomas and three developed early postoperative thrombosis treated with lysis in two cases and thrombectomy in one. All three patients were discharged with patency restored.

One segmental occlusion of the CFV has occurred, and a recent patient with longstanding sickle cell disease developed significant acute lymphedema "that we are still at a loss to explain," he said.

At 6 months, significant improvements were observed in preoperative scores on the Villalta scale (mean, 14 vs. 6; P = .002), Venous Clinical Severity Score (mean, 17 vs. 10; P = .02), CEAP (mean, 4.8 vs. 3.8; P less than .05) and Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study-Quality of Life/Sym questionnaire (data not provided; P = .01).

In some patients, the turnaround was quite dramatic, observed Dr. Comerota, who described a patient who suffered severe trauma and was unable to be anticoagulated. He subsequently had chronic iliofemoral and caval obstruction causing a swollen limb and a painful ulcer for 4 years. The day after surgery, there was remarkable change in the color of the ulcer and leg, and within 3 months the ulcer was completely healed, most of the edema was controlled, and his legs were no longer painful to compression, he said. The patient is back to full activity and has lost 30 pounds.

As a result of inactivity, many of the patients had gained a significant amount of weight, thereby requiring a large incision.

"It is a big procedure," said Dr. Comerota, adding that "it is certainly a procedure in evolution."

Some of the issues requiring further study include the risk/benefit of combined preoperative platelet inhibition and the optimal postoperative anticoagulation; location of an arteriovenous (AV) fistula; and size of the wound drain, currently a 7F closed suction drain.

Three days prior to the procedure, patients receive platelet inhibition with aspirin 81 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day and twice-daily chlorhexidine showers.

On the day of surgery, patients are fully anticoagulated with 100 IU/kg of unfractionated heparin. It is not reversed with protamine after the surgery is complete, but rather followed with a standard intravenous therapeutic heparin infusion, he said. To reduce the need for supratherapeutic systemic anticoagulation in some patients, a silastic intravenous catheter was placed in a dorsal foot vein to infuse the postoperative heparin.

A small AV fistula of 3.5-4 mm has been required in about half of procedures after continuous wave Doppler failed to identify robust venous velocity signals. The goal of the AV fistula is to increase velocity but not venous pressure, and it has typically been constructed with a wrap around the greater saphenous vein to ensure that it will not enlarge over time, Dr. Comerota said.

"I’ve never been sorry I did an AV fistula. I certainly have been sorry that I have not, so now it’s a routine part of the procedure," he added.

If an iliac venous stenosis or occlusion needs to be stented, Dr. Comerota said that he prefers Wallstents.

"I’m not sure if radial strength is the best term, but Wallstents have the best compression to pressure," he explained. "We’ve used Nitinol [stents] earlier on in our experience, but we had to go back in and reline 50% to 60% of them because they just didn’t hold up the vein properly."

Initially, the team also attempted to keep the stents above the inguinal ligament, but it now takes the approach that the iliac venous occlusion can be stented into the endovenectomized portion of the external iliac vein or CFV, with the caveat that the distal end of the stent must stay above the saphenofemoral junction to preserve profunda femoris venous drainage. Stenting avoids skip lesions that might lead to recurrent thrombosis or continued functional compromise, Dr. Comerota noted.

During a discussion of the procedure, he said that symptomatic presentation and degree of disability are used to determine whether patients should undergo the rigorous procedure.

Surgeons at the Mayo Clinic reported far less promising results in 12 patients who underwent CFV endovenectomy, patch angioplasty, and stenting for chronic iliofemoral venous obstruction, with a 30% 2-year patency and 50% of ulcers with patent grafts recurring (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53:383-93).

Dr. Comerata presents an aggressive approach to venous obstructive disease, with operative resection of the fibrotic tissue within the common femoral vein, coupled with endovascular stenting of the iliac segment. He reports relatively good results for these complex patients with a large operative procedure. Other groups have yet to replicate his results and the study population is still relatively small. Certainly, this technique is worth further prospective assessment, as this patient population does experience fairly debilitating symptoms. Whether open surgical treatment coupled with endovascular intervention is the best option remains to be seen.

Dr. Linda Harris is chief of the division of vascular surgery at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris stated that she had no disclosures.

Dr. Comerata presents an aggressive approach to venous obstructive disease, with operative resection of the fibrotic tissue within the common femoral vein, coupled with endovascular stenting of the iliac segment. He reports relatively good results for these complex patients with a large operative procedure. Other groups have yet to replicate his results and the study population is still relatively small. Certainly, this technique is worth further prospective assessment, as this patient population does experience fairly debilitating symptoms. Whether open surgical treatment coupled with endovascular intervention is the best option remains to be seen.

Dr. Linda Harris is chief of the division of vascular surgery at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris stated that she had no disclosures.

Dr. Comerata presents an aggressive approach to venous obstructive disease, with operative resection of the fibrotic tissue within the common femoral vein, coupled with endovascular stenting of the iliac segment. He reports relatively good results for these complex patients with a large operative procedure. Other groups have yet to replicate his results and the study population is still relatively small. Certainly, this technique is worth further prospective assessment, as this patient population does experience fairly debilitating symptoms. Whether open surgical treatment coupled with endovascular intervention is the best option remains to be seen.

Dr. Linda Harris is chief of the division of vascular surgery at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris stated that she had no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Common femoral endovenectomy with endoluminal iliac recanalization should be considered in patients with chronic post-thrombotic iliofemoral venous obstruction.

The procedure substantially reduces post-thrombotic syndrome morbidity and improves quality of life, although it "is not a procedure for the faint of heart," acknowledged Dr. Anthony Comerota, director of the Jobst Vascular Center at ProMedica Toledo (Ohio) Hospital.

Postthrombotic syndrome occurs in 30%-40% of all patients with a lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at 2 years, despite the use of anticoagulation. Postthrombotic syndrome can be particularly debilitating following an iliofemoral DVT if the common femoral vein (CFV) is badly obstructed or occluded, resulting in such poor quality of life that Dr. Comerota compared it with angina, cancer, and congestive heart failure.

Stenting and angioplasty are often successful in treating postthrombotic iliac vein occlusion, although the risk of stent occlusion is at least 3.8-fold higher in postthrombotic limbs if the stent is extended below the inguinal ligament, he noted.

Relative obstruction of the CFV also can persist after percutaneous intervention and compromise drainage from the profunda femoris vein. This mitigates the benefits of iliac vein recanalization and can actually worsen the patient’s post-thrombotic symptoms, Dr. Comerota said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

"It is crucial to open up the orifice of the profunda," he said. "One of the problems we’ve seen in patients referred to us is that, when the common femoral was stented and the stent takes that fibrous tissue and plasters it up against the orifice of the profunda, if there was any minimal drainage from the profunda, it will obliterate it and those patients got worse."

Having previously detailed the technical aspects of the procedure (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:129-35), Dr. Comerota highlighted outcomes of 14 patients and 16 limbs treated to date for severe post-thrombotic, iliofemoral/caval venous obstruction with CEAP (clinical severity, etiology, anatomy, pathophysiology) classification of C3-C6. The median duration of obstruction was nearly 7 years (range, 7 months to 25 years) and median follow-up 3 years (range, 5 months to 6 years). Two patients were lost to follow-up.

To date, one death occurred in a 52-year-old woman with multiple cardiovascular risk factors 9 days after discharge because of an acute myocardial infarction, Dr. Comerota said.

Three patients required surgical evacuation of wound hematomas and three developed early postoperative thrombosis treated with lysis in two cases and thrombectomy in one. All three patients were discharged with patency restored.

One segmental occlusion of the CFV has occurred, and a recent patient with longstanding sickle cell disease developed significant acute lymphedema "that we are still at a loss to explain," he said.

At 6 months, significant improvements were observed in preoperative scores on the Villalta scale (mean, 14 vs. 6; P = .002), Venous Clinical Severity Score (mean, 17 vs. 10; P = .02), CEAP (mean, 4.8 vs. 3.8; P less than .05) and Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study-Quality of Life/Sym questionnaire (data not provided; P = .01).

In some patients, the turnaround was quite dramatic, observed Dr. Comerota, who described a patient who suffered severe trauma and was unable to be anticoagulated. He subsequently had chronic iliofemoral and caval obstruction causing a swollen limb and a painful ulcer for 4 years. The day after surgery, there was remarkable change in the color of the ulcer and leg, and within 3 months the ulcer was completely healed, most of the edema was controlled, and his legs were no longer painful to compression, he said. The patient is back to full activity and has lost 30 pounds.

As a result of inactivity, many of the patients had gained a significant amount of weight, thereby requiring a large incision.

"It is a big procedure," said Dr. Comerota, adding that "it is certainly a procedure in evolution."

Some of the issues requiring further study include the risk/benefit of combined preoperative platelet inhibition and the optimal postoperative anticoagulation; location of an arteriovenous (AV) fistula; and size of the wound drain, currently a 7F closed suction drain.

Three days prior to the procedure, patients receive platelet inhibition with aspirin 81 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day and twice-daily chlorhexidine showers.

On the day of surgery, patients are fully anticoagulated with 100 IU/kg of unfractionated heparin. It is not reversed with protamine after the surgery is complete, but rather followed with a standard intravenous therapeutic heparin infusion, he said. To reduce the need for supratherapeutic systemic anticoagulation in some patients, a silastic intravenous catheter was placed in a dorsal foot vein to infuse the postoperative heparin.

A small AV fistula of 3.5-4 mm has been required in about half of procedures after continuous wave Doppler failed to identify robust venous velocity signals. The goal of the AV fistula is to increase velocity but not venous pressure, and it has typically been constructed with a wrap around the greater saphenous vein to ensure that it will not enlarge over time, Dr. Comerota said.

"I’ve never been sorry I did an AV fistula. I certainly have been sorry that I have not, so now it’s a routine part of the procedure," he added.

If an iliac venous stenosis or occlusion needs to be stented, Dr. Comerota said that he prefers Wallstents.

"I’m not sure if radial strength is the best term, but Wallstents have the best compression to pressure," he explained. "We’ve used Nitinol [stents] earlier on in our experience, but we had to go back in and reline 50% to 60% of them because they just didn’t hold up the vein properly."

Initially, the team also attempted to keep the stents above the inguinal ligament, but it now takes the approach that the iliac venous occlusion can be stented into the endovenectomized portion of the external iliac vein or CFV, with the caveat that the distal end of the stent must stay above the saphenofemoral junction to preserve profunda femoris venous drainage. Stenting avoids skip lesions that might lead to recurrent thrombosis or continued functional compromise, Dr. Comerota noted.

During a discussion of the procedure, he said that symptomatic presentation and degree of disability are used to determine whether patients should undergo the rigorous procedure.

Surgeons at the Mayo Clinic reported far less promising results in 12 patients who underwent CFV endovenectomy, patch angioplasty, and stenting for chronic iliofemoral venous obstruction, with a 30% 2-year patency and 50% of ulcers with patent grafts recurring (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53:383-93).

CHICAGO – Common femoral endovenectomy with endoluminal iliac recanalization should be considered in patients with chronic post-thrombotic iliofemoral venous obstruction.

The procedure substantially reduces post-thrombotic syndrome morbidity and improves quality of life, although it "is not a procedure for the faint of heart," acknowledged Dr. Anthony Comerota, director of the Jobst Vascular Center at ProMedica Toledo (Ohio) Hospital.

Postthrombotic syndrome occurs in 30%-40% of all patients with a lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at 2 years, despite the use of anticoagulation. Postthrombotic syndrome can be particularly debilitating following an iliofemoral DVT if the common femoral vein (CFV) is badly obstructed or occluded, resulting in such poor quality of life that Dr. Comerota compared it with angina, cancer, and congestive heart failure.

Stenting and angioplasty are often successful in treating postthrombotic iliac vein occlusion, although the risk of stent occlusion is at least 3.8-fold higher in postthrombotic limbs if the stent is extended below the inguinal ligament, he noted.

Relative obstruction of the CFV also can persist after percutaneous intervention and compromise drainage from the profunda femoris vein. This mitigates the benefits of iliac vein recanalization and can actually worsen the patient’s post-thrombotic symptoms, Dr. Comerota said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

"It is crucial to open up the orifice of the profunda," he said. "One of the problems we’ve seen in patients referred to us is that, when the common femoral was stented and the stent takes that fibrous tissue and plasters it up against the orifice of the profunda, if there was any minimal drainage from the profunda, it will obliterate it and those patients got worse."

Having previously detailed the technical aspects of the procedure (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:129-35), Dr. Comerota highlighted outcomes of 14 patients and 16 limbs treated to date for severe post-thrombotic, iliofemoral/caval venous obstruction with CEAP (clinical severity, etiology, anatomy, pathophysiology) classification of C3-C6. The median duration of obstruction was nearly 7 years (range, 7 months to 25 years) and median follow-up 3 years (range, 5 months to 6 years). Two patients were lost to follow-up.

To date, one death occurred in a 52-year-old woman with multiple cardiovascular risk factors 9 days after discharge because of an acute myocardial infarction, Dr. Comerota said.

Three patients required surgical evacuation of wound hematomas and three developed early postoperative thrombosis treated with lysis in two cases and thrombectomy in one. All three patients were discharged with patency restored.

One segmental occlusion of the CFV has occurred, and a recent patient with longstanding sickle cell disease developed significant acute lymphedema "that we are still at a loss to explain," he said.

At 6 months, significant improvements were observed in preoperative scores on the Villalta scale (mean, 14 vs. 6; P = .002), Venous Clinical Severity Score (mean, 17 vs. 10; P = .02), CEAP (mean, 4.8 vs. 3.8; P less than .05) and Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study-Quality of Life/Sym questionnaire (data not provided; P = .01).

In some patients, the turnaround was quite dramatic, observed Dr. Comerota, who described a patient who suffered severe trauma and was unable to be anticoagulated. He subsequently had chronic iliofemoral and caval obstruction causing a swollen limb and a painful ulcer for 4 years. The day after surgery, there was remarkable change in the color of the ulcer and leg, and within 3 months the ulcer was completely healed, most of the edema was controlled, and his legs were no longer painful to compression, he said. The patient is back to full activity and has lost 30 pounds.

As a result of inactivity, many of the patients had gained a significant amount of weight, thereby requiring a large incision.

"It is a big procedure," said Dr. Comerota, adding that "it is certainly a procedure in evolution."

Some of the issues requiring further study include the risk/benefit of combined preoperative platelet inhibition and the optimal postoperative anticoagulation; location of an arteriovenous (AV) fistula; and size of the wound drain, currently a 7F closed suction drain.

Three days prior to the procedure, patients receive platelet inhibition with aspirin 81 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day and twice-daily chlorhexidine showers.

On the day of surgery, patients are fully anticoagulated with 100 IU/kg of unfractionated heparin. It is not reversed with protamine after the surgery is complete, but rather followed with a standard intravenous therapeutic heparin infusion, he said. To reduce the need for supratherapeutic systemic anticoagulation in some patients, a silastic intravenous catheter was placed in a dorsal foot vein to infuse the postoperative heparin.

A small AV fistula of 3.5-4 mm has been required in about half of procedures after continuous wave Doppler failed to identify robust venous velocity signals. The goal of the AV fistula is to increase velocity but not venous pressure, and it has typically been constructed with a wrap around the greater saphenous vein to ensure that it will not enlarge over time, Dr. Comerota said.

"I’ve never been sorry I did an AV fistula. I certainly have been sorry that I have not, so now it’s a routine part of the procedure," he added.

If an iliac venous stenosis or occlusion needs to be stented, Dr. Comerota said that he prefers Wallstents.

"I’m not sure if radial strength is the best term, but Wallstents have the best compression to pressure," he explained. "We’ve used Nitinol [stents] earlier on in our experience, but we had to go back in and reline 50% to 60% of them because they just didn’t hold up the vein properly."

Initially, the team also attempted to keep the stents above the inguinal ligament, but it now takes the approach that the iliac venous occlusion can be stented into the endovenectomized portion of the external iliac vein or CFV, with the caveat that the distal end of the stent must stay above the saphenofemoral junction to preserve profunda femoris venous drainage. Stenting avoids skip lesions that might lead to recurrent thrombosis or continued functional compromise, Dr. Comerota noted.

During a discussion of the procedure, he said that symptomatic presentation and degree of disability are used to determine whether patients should undergo the rigorous procedure.

Surgeons at the Mayo Clinic reported far less promising results in 12 patients who underwent CFV endovenectomy, patch angioplasty, and stenting for chronic iliofemoral venous obstruction, with a 30% 2-year patency and 50% of ulcers with patent grafts recurring (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53:383-93).

AT A SYMPOSIUM ON VASCULAR SURGERY SPONSORED BY NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

Major Finding: At 6 months, significant improvements were observed in preoperative scores on the Villalta scale (mean 14 vs. 6; P = .002), Venous Clinical Severity Score (mean 17 vs. 10; P = .02), and CEAP (mean 4.8 vs. 3.8; P less than .05).

Data Source: Outcomes of 14 patients and 16 limbs treated to date for severe post-thrombotic, iliofemoral/caval venous obstruction with CEAP classification of C3-C6.

Disclosures: Dr. Comerota reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Locoregional anesthesia boosts amputation success

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Locoregional anesthesia boosts the success rate of lower-extremity amputations, while time-saving shortcuts and relying too heavily on surgical residents to perform the surgery raise the risk that an amputation patient will run into problems following surgery, according to a review of nearly 9,000 U.S. patients.

Based on these findings, "we use locoregional anesthesia when possible," and focus on "careful and meticulous handling of tissue," Dr. P. Joshua O’Brien said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. "This is the first paper to suggest that locoregional anesthesia may have a protective effect and improve outcomes."

The study results also made Dr. O’Brien and his colleagues at Duke University in Durham, N.C., more aware that amputations "are an important procedure" even though they are often a "junior-level case frequently overseen by a senior resident." The study results prompted Duke attending surgeons to maintain "careful observation of the residents until they feel comfortable that they [the residents] adequately understand the art of performing an amputation," said Dr. O’Brien, a vascular surgeon at Duke.

The analysis he and his associates performed used data collected during 2005-2010 by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons. The study included patients who underwent an above-the-knee amputation (3,415 patients – 38%), a below-the-knee amputation (4,258 patients – 48%), or a transmetatarsal amputation (1,205 patients – 14%), but excluded patients who had another surgical procedure with their amputation, prior surgery within 30 days of the amputation, a preoperative do-not-resuscitate order, or missing data; 63% of all the amputation patients had diabetes.

During 30-day postsurgical follow-up, the overall rate of amputation failure was 13%, death occurred in 7%, wound complications affected 9%, and nonwound complications affected 21%. The patients averaged a 6-day postsurgical hospital length of stay.

Early amputation failure showed a statistically significant link with the type of amputation. Patients with a transmetatarsal amputation had a 26% early failure rate, those who underwent a below-the-knee procedure had a 13% failure rate, while above-the-knee amputations failed 8% of the time.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for patient- and procedure-related factors, several variables linked with statistically significant increases or decreases in the rate of amputation failure. Notable among the factors that increased failure rates were emergency surgery, which boosted the failure rate 2.2-fold compared with nonemergency surgery, and participation of a surgical trainee, which raised the rate 37% compared with the rate when no trainee participated. Trainee participation was common, occurring in 59% of the 8,878 amputations included in the analysis.

Among the factors significantly linked with a reduced rate of amputation failures were use of locoregional anesthesia, which cut the failure rate by 25% compared with general anesthesia, and operative times of at least 40 minutes, which cut failure rates compared with surgery times of less than 40 minutes. The lowest failure rates occurred when the duration of amputation surgery lasted at least 60 minutes. Among patients included in the study, 20% received locoregional anesthesia.

The results also highlighted the important association of amputation failure with other measures of poor surgical outcomes in these amputation patients. Patients who developed amputation failure within 30 days of their surgery also had a nearly sevenfold increased rate of wound complications, and a twofold increased rate of nonwound complications; the average hospital length of stay was 10 days compared with 5 days among patients without amputation. Amputation failure had no significant impact on postoperative mortality, Dr. O’Brien said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Locoregional anesthesia boosts the success rate of lower-extremity amputations, while time-saving shortcuts and relying too heavily on surgical residents to perform the surgery raise the risk that an amputation patient will run into problems following surgery, according to a review of nearly 9,000 U.S. patients.

Based on these findings, "we use locoregional anesthesia when possible," and focus on "careful and meticulous handling of tissue," Dr. P. Joshua O’Brien said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. "This is the first paper to suggest that locoregional anesthesia may have a protective effect and improve outcomes."

The study results also made Dr. O’Brien and his colleagues at Duke University in Durham, N.C., more aware that amputations "are an important procedure" even though they are often a "junior-level case frequently overseen by a senior resident." The study results prompted Duke attending surgeons to maintain "careful observation of the residents until they feel comfortable that they [the residents] adequately understand the art of performing an amputation," said Dr. O’Brien, a vascular surgeon at Duke.

The analysis he and his associates performed used data collected during 2005-2010 by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons. The study included patients who underwent an above-the-knee amputation (3,415 patients – 38%), a below-the-knee amputation (4,258 patients – 48%), or a transmetatarsal amputation (1,205 patients – 14%), but excluded patients who had another surgical procedure with their amputation, prior surgery within 30 days of the amputation, a preoperative do-not-resuscitate order, or missing data; 63% of all the amputation patients had diabetes.

During 30-day postsurgical follow-up, the overall rate of amputation failure was 13%, death occurred in 7%, wound complications affected 9%, and nonwound complications affected 21%. The patients averaged a 6-day postsurgical hospital length of stay.

Early amputation failure showed a statistically significant link with the type of amputation. Patients with a transmetatarsal amputation had a 26% early failure rate, those who underwent a below-the-knee procedure had a 13% failure rate, while above-the-knee amputations failed 8% of the time.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for patient- and procedure-related factors, several variables linked with statistically significant increases or decreases in the rate of amputation failure. Notable among the factors that increased failure rates were emergency surgery, which boosted the failure rate 2.2-fold compared with nonemergency surgery, and participation of a surgical trainee, which raised the rate 37% compared with the rate when no trainee participated. Trainee participation was common, occurring in 59% of the 8,878 amputations included in the analysis.

Among the factors significantly linked with a reduced rate of amputation failures were use of locoregional anesthesia, which cut the failure rate by 25% compared with general anesthesia, and operative times of at least 40 minutes, which cut failure rates compared with surgery times of less than 40 minutes. The lowest failure rates occurred when the duration of amputation surgery lasted at least 60 minutes. Among patients included in the study, 20% received locoregional anesthesia.

The results also highlighted the important association of amputation failure with other measures of poor surgical outcomes in these amputation patients. Patients who developed amputation failure within 30 days of their surgery also had a nearly sevenfold increased rate of wound complications, and a twofold increased rate of nonwound complications; the average hospital length of stay was 10 days compared with 5 days among patients without amputation. Amputation failure had no significant impact on postoperative mortality, Dr. O’Brien said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Locoregional anesthesia boosts the success rate of lower-extremity amputations, while time-saving shortcuts and relying too heavily on surgical residents to perform the surgery raise the risk that an amputation patient will run into problems following surgery, according to a review of nearly 9,000 U.S. patients.

Based on these findings, "we use locoregional anesthesia when possible," and focus on "careful and meticulous handling of tissue," Dr. P. Joshua O’Brien said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. "This is the first paper to suggest that locoregional anesthesia may have a protective effect and improve outcomes."

The study results also made Dr. O’Brien and his colleagues at Duke University in Durham, N.C., more aware that amputations "are an important procedure" even though they are often a "junior-level case frequently overseen by a senior resident." The study results prompted Duke attending surgeons to maintain "careful observation of the residents until they feel comfortable that they [the residents] adequately understand the art of performing an amputation," said Dr. O’Brien, a vascular surgeon at Duke.

The analysis he and his associates performed used data collected during 2005-2010 by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons. The study included patients who underwent an above-the-knee amputation (3,415 patients – 38%), a below-the-knee amputation (4,258 patients – 48%), or a transmetatarsal amputation (1,205 patients – 14%), but excluded patients who had another surgical procedure with their amputation, prior surgery within 30 days of the amputation, a preoperative do-not-resuscitate order, or missing data; 63% of all the amputation patients had diabetes.

During 30-day postsurgical follow-up, the overall rate of amputation failure was 13%, death occurred in 7%, wound complications affected 9%, and nonwound complications affected 21%. The patients averaged a 6-day postsurgical hospital length of stay.

Early amputation failure showed a statistically significant link with the type of amputation. Patients with a transmetatarsal amputation had a 26% early failure rate, those who underwent a below-the-knee procedure had a 13% failure rate, while above-the-knee amputations failed 8% of the time.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for patient- and procedure-related factors, several variables linked with statistically significant increases or decreases in the rate of amputation failure. Notable among the factors that increased failure rates were emergency surgery, which boosted the failure rate 2.2-fold compared with nonemergency surgery, and participation of a surgical trainee, which raised the rate 37% compared with the rate when no trainee participated. Trainee participation was common, occurring in 59% of the 8,878 amputations included in the analysis.

Among the factors significantly linked with a reduced rate of amputation failures were use of locoregional anesthesia, which cut the failure rate by 25% compared with general anesthesia, and operative times of at least 40 minutes, which cut failure rates compared with surgery times of less than 40 minutes. The lowest failure rates occurred when the duration of amputation surgery lasted at least 60 minutes. Among patients included in the study, 20% received locoregional anesthesia.

The results also highlighted the important association of amputation failure with other measures of poor surgical outcomes in these amputation patients. Patients who developed amputation failure within 30 days of their surgery also had a nearly sevenfold increased rate of wound complications, and a twofold increased rate of nonwound complications; the average hospital length of stay was 10 days compared with 5 days among patients without amputation. Amputation failure had no significant impact on postoperative mortality, Dr. O’Brien said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Use of locoregional anesthesia cut the rate of amputation failure within 30 days after surgery 25% compared with general anesthesia.

Data Source: Data came from a review of 8,878 U.S. patients who underwent a lower-extremity amputation during 2005-2010.

Disclosures: Dr. O’Brien said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Ruptured AAA triage to EVAR centers proposed

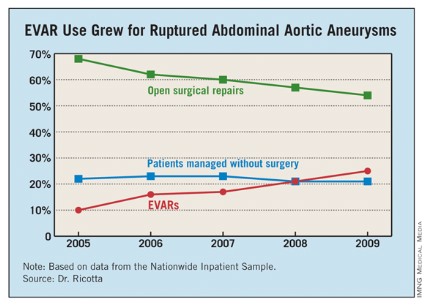

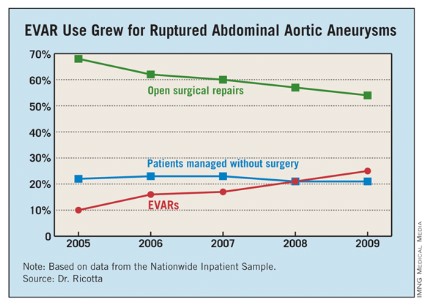

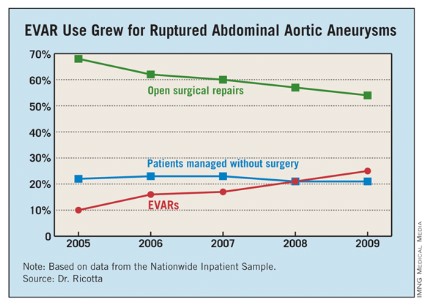

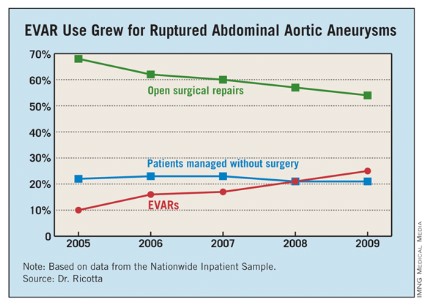

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: From 2005 to 2009, the percentage of hospitalized U.S. patients with a ruptured AAA who underwent EVAR grew from 10% to 25%.

Data Source: The data came from an analysis of 21,218 U.S. patients hospitalized for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm during 2005-2009 and included in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

Long-Term Mortality Similar After Endovascular vs. Open Repair of AAA

For patients who undergo elective repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm, long-term mortality is not significantly different between those who have endovascular surgery and those who have open surgery, according to a report published online Nov. 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Perioperative survival was superior with the endovascular approach, and that advantage lasted for up to 3 years. But from that point on, survival was similar between patients who had undergone endovascular repair and those who had undergone open repair, said Dr. Frank A. Lederle of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minn., and his associates.

Three large, randomized clinical trials compared the two surgical approaches: the United Kingdom Endovascular Repair 1 (EVAR 1) trial, the Dutch Randomized Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) trial, and the Open versus Endovascular Repair (OVER) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study in the United States. All three studies initially showed a survival advantage with the endovascular procedure in the perioperative period. But longer follow-up in the EVAR 1 and DREAM studies suggested that this advantage was lost at approximately 2 years, due to an excess in late deaths among patients who had undergone endovascular repair.

Dr. Lederle and his colleagues now report the long-term findings of the OVER trial, and they also found that at approximately 3 years, the survival curves between the two study groups converged.

The OVER trial was conducted at 42 VA medical centers across the country and involved 881 patients. The mean patient age was 70 years, and, as is typical in VA cohorts, 99% of the subjects were male.

All patients had abdominal aortic aneurysms with a maximal external diameter of at least 5 cm, an associated iliac-artery aneurysm with a maximum diameter of at least 3 cm, or a maximal diameter of at least 4.5 cm plus either rapid enlargement or a saccular appearance on radiography and CT examination.

A total of 444 study subjects were randomly assigned to endovascular repair and 437 to open repair. They were followed for up to 9 years (mean follow-up, 5.2 years). During that time, there were 146 deaths in each group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in the endovascular group at 2 years, but that difference was only of borderline significance at 3 years and disappeared completely thereafter. Similarly, the restricted mean survival was no different between the two groups at 5 years and at 9 years (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1988-97 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1207481]).

The time to a second therapeutic procedure or death was similar between the two groups, as were the number of hospitalizations after the initial repair, the number of secondary therapeutic procedures needed, and postoperative quality of life.

The most likely explanation for the convergence of the survival curves over time is that the frailest patients in the open-repair group died soon after that rigorous procedure, while the frailest patients in the endovascular-repair group survived that less invasive surgery but succumbed within a year or two, Dr. Lederle and his associates said.

When the data were analyzed according to patient age, an interesting result emerged: Patients younger than age 70 had better survival with endovascular than with open repair, while patients older than age 70 had better survival with open than with endovascular repair. This was surprising, given that "much of the early enthusiasm for endovascular repair focused on the expected advantage among old or infirm patients who were not good candidates for open repair," they noted.

Even though the rate of late ruptures was higher for the endovascular approach, it was still a very low rate, "with only six ruptures during 4,576 patient-years of follow-up." Moreover, four of these six late ruptures occurred in elderly patients, three of whom didn’t adhere to the recommended follow-up.

"We therefore consider endovascular repair to be a reasonable option in patients younger than 70 years of age who are likely to adhere to medical advice," Dr. Lederle and his colleagues said.

Nevertheless, endovascular repair "does not yet offer a long-term advantage over open repair, particularly among older patients, for whom such an advantage was originally expected," they noted.

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development. Dr. Lederle reported no financial conflicts of interest; one of his associates reported ties to Abbott, Cook, Covidien, Gore, and Endologix.

Now that all three large randomized clinical trials confirm that long-term outcomes are similar between endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms, patient preferences can become a larger part of the decision as to which surgery to pursue, said Dr. Joshua A. Beckman.

Now "patients can weight the value of open repair, a major operation with greater up-front morbidity and mortality, against that of endovascular repair, with its lower early-event rate but the need for indefinite radiologic surveillance," he said.

"The results of the OVER study confirm that the patient population that should undergo AAA repair remains the same as it has been for the past 15 years. Thus, endovascular repair has neither expanded AAA repair to new populations nor reduced long-term mortality when compared with open repair," he added.

"The dream of improving long-term survival and expanding the population that will benefit from AAA repair [using EVAR] is seemingly over, but the reality of better procedural recovery for patients today is certainly a step forward," Dr. Beckman concluded.

Joshua A. Beckman, M.D., is with the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. He reported ties to Novartis, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, BMS, and Lupin. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying Dr. Lederle’s report (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 Nov. 22 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1211163]).

Now that all three large randomized clinical trials confirm that long-term outcomes are similar between endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms, patient preferences can become a larger part of the decision as to which surgery to pursue, said Dr. Joshua A. Beckman.

Now "patients can weight the value of open repair, a major operation with greater up-front morbidity and mortality, against that of endovascular repair, with its lower early-event rate but the need for indefinite radiologic surveillance," he said.

"The results of the OVER study confirm that the patient population that should undergo AAA repair remains the same as it has been for the past 15 years. Thus, endovascular repair has neither expanded AAA repair to new populations nor reduced long-term mortality when compared with open repair," he added.

"The dream of improving long-term survival and expanding the population that will benefit from AAA repair [using EVAR] is seemingly over, but the reality of better procedural recovery for patients today is certainly a step forward," Dr. Beckman concluded.

Joshua A. Beckman, M.D., is with the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. He reported ties to Novartis, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, BMS, and Lupin. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying Dr. Lederle’s report (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 Nov. 22 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1211163]).

Now that all three large randomized clinical trials confirm that long-term outcomes are similar between endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms, patient preferences can become a larger part of the decision as to which surgery to pursue, said Dr. Joshua A. Beckman.

Now "patients can weight the value of open repair, a major operation with greater up-front morbidity and mortality, against that of endovascular repair, with its lower early-event rate but the need for indefinite radiologic surveillance," he said.

"The results of the OVER study confirm that the patient population that should undergo AAA repair remains the same as it has been for the past 15 years. Thus, endovascular repair has neither expanded AAA repair to new populations nor reduced long-term mortality when compared with open repair," he added.