User login

Does stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improve outomes compared with medical therapy alone?

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

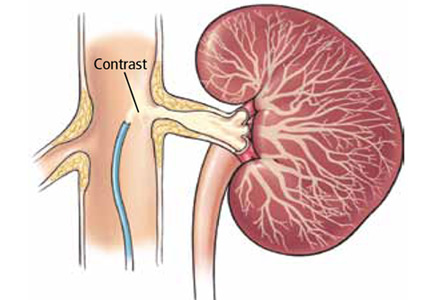

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

Stenting may benefit select patients with severe renal artery stenosis

In their article in this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Kabach et al answer no to the question of whether stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improves outcomes compared with medical therapy alone.1 They review the findings of four key studies2–5 published between 2003 and 2014 and conclude that, in patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting with medical therapy can improve blood pressure control but has no significant impact on cardiovascular or mortality outcomes.1

Furthermore, the authors state that in view of the risk of complications associated with stenting, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.1 Indeed, the ASTRAL study (Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions) investigators found substantial risks without evidence of a worthwhile clinical benefit from revascularization in patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease.3

Nevertheless, I believe that this procedure may benefit certain patients.

MAYO CLINIC COHORT STUDY

In 2008, our group at Mayo Clinic Health system in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, published the results of a prospective cohort study in 26 patients with renal artery stenosis and chronic kidney disease who presented with rapidly worsening renal failure (defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 25%) while receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB).6,7

These drugs—inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system—slow the progression of chronic kidney disease but can acutely worsen renal function, especially in patients with renal artery stenosis, and withdrawing them in this situation was the focus of our study.

The patients (10 men and 16 women) ranged in age from 63 to 87 (mean age 75.3).

At enrollment, the ACE inhibitors and ARBs were discontinued, standard nephrologic care was applied, and the glomerular filtration rate (estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) was monitored. After at least 2 weeks, percutaneous renal angioplasty with stent placement was considered if the patient met any of the following criteria:

- Persistence of renal failure

- Flash pulmonary edema

- Uncontrolled hypertension despite the use of at least three antihypertensive medications.

Nine patients underwent percutaneous angioplasty and stenting and 17 did not. The procedure was done on one renal artery in 8 patients and both renal arteries in 1. Indications for the procedure were recent worsening of renal failure in 8 patients and recent worsening renal failure together with symptomatic flash pulmonary edema in 1 patient. (Flash pulmonary edema is the only class I recommendation for percutaneous renal angioplasty in the 2006 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.8) As noted above, all the patients were experiencing acute exacerbation of chronic kidney disease at the time.

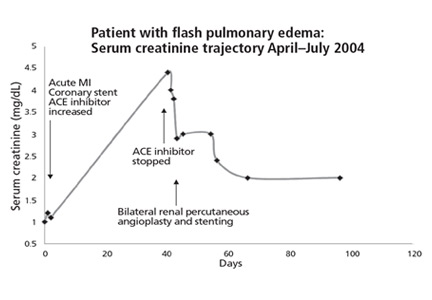

We found clear evidence of additional improved and sustained renal function in the patients who underwent percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting compared with the patients who did not (Figures 1 and 2).6,7

In an editorial9 following publication of the ASTRAL study, our group reported a subsequent 82-month analysis of our 26-patient cohort completed in June 2009. In the 7 surviving patients who had undergone percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting, the estimated glomerular filtration rate had increased from 27.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (± 12.7, range 11–47) at baseline to 50.3 (± 21.7, range 23–68) (P = .018) after 46.9 months.

PATIENT NUMBER 13

To illustrate how percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting can reverse recently worsening renal failure in renal artery stenosis, I would like to discuss in greater detail a patient from our two previous reports.6,7

Patient 13, a 67-year-old woman with hypertension, was referred to our nephrology service in September 2004 to consider starting hemodialysis for symptomatic renal failure. Her serum creatinine had increased to 3.4 mg/dL from a previous baseline level of 2.0 mg/dL, and she also had worsening anemia and hyperkalemia. She had been taking lisinopril 10 mg/day for the last 12 months. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed high-grade (> 95%) bilateral renal artery stenosis with an atrophic left kidney.

Lisinopril was promptly discontinued, and within 2 weeks her serum creatinine level had decreased by more than 0.5 mg/dL. In mid-November 2004, she underwent right renal artery angioplasty with stent placement. After that, her serum creatinine decreased further, and 3 months later it had dropped to 1.6 mg/dL. The value continued to improve, with the lowest measurement of 1.1 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 51 mL/min/1.73 m2. This was in May 2006, 19 months after stopping lisinopril and 17 months after angioplasty and stenting. The last available serum creatinine level (August 2006) was 1.2 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the patient died of metastatic lung cancer in December of that year.

Also of note, the patient who underwent angioplasty because of recurrent flash pulmonary edema had no recurrences of it afterward.

We concluded that, in patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis presenting with acutely worsening renal failure, renal angioplasty with stenting has the potential to reverse renal failure, improve blood pressure control, and stop flash pulmonary edema.6–8

Notably, all patients in our study who underwent renal angioplasty with stenting had new-onset acute renal injury as defined by an increase in the baseline serum creatinine of more than 25% during the 3 months before stent placement.6–8 Patients in the STAR,2 HERCULES,4 and CORAL5 studies had renal artery stenosis but otherwise stable chronic kidney disease at the time of enrollment. In the ASTRAL study,3 12% of the patients had acute kidney injury on study enrollment, defined as an increase in the serum creatinine level of more than 20% or of more than 1.13 mg/dL.3

While we strongly agree with aggressive yet monitored medical therapy for patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis, I posit that selected patients do indeed derive significant clinical benefits from renal angioplasty and stenting. Our group’s prospective individual-patient-level data support the paradigm that angioplasty with stenting is useful in patients with renal artery stenosis who experience “acute-on-chronic” kidney disease.

The pathophysiology of renal artery stenosis and the progression of chronic kidney disease are complex, and many factors affect patient outcomes and response to treatment. Thus, the message is that treatment of severe renal artery stenosis must be individualized.9–11 No one treatment fits all.10,11

- Kabach A, Agha OQ, Baibars M, Alraiyes AH, Alraies MC. Does stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improve outcomes compared with medical therapy alone? Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:491–494.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of STent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by Atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the Renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Jaff MR, Bates M, Sullivan T, et al; HERCULES Investigators. Significant reduction in systolic blood pressure following renal artery stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results from the HERCULES trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80:343–350.

- Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, et al; CORAL Investigators. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:13–22.

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo NTC. Worsening renal failure in older chronic kidney disease patients with renal artery stenosis concurrently on renin angiotensin aldosterone system blockade: a prospective 50-month Mayo Health System clinic analysis. QJM 2008; 101:519–527.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo NT. Renal failure and concurrent RAAS blockade in older CKD patients with renal artery stenosis: an extended Mayo Clinic prospective 63-month experience. Ren Fail 2008; 30:363–371.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

- Onuigbo M, Frenandes R, Nijhawan V. The ASTRAL trial results revisited—to stent or not to stent in renal artery stenosis? QJM 2010; 103:357.

- Singh M, Kovacs DF, Singh A, Dhaliwal P, Khosla S. ACE inhibition and renal artery stenosis: what lessons have we learnt? A 21st century perspective. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 2. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013:203–218.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo C, Onuigbo V, et al. The CKD enigma, reengineering CKD care, narrowing asymmetric information and confronting ethicomedicinomics in CKD care: the introduction of the new 'CKD express©' IT software program. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE Inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 1. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013: 41–56.

In their article in this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Kabach et al answer no to the question of whether stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improves outcomes compared with medical therapy alone.1 They review the findings of four key studies2–5 published between 2003 and 2014 and conclude that, in patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting with medical therapy can improve blood pressure control but has no significant impact on cardiovascular or mortality outcomes.1

Furthermore, the authors state that in view of the risk of complications associated with stenting, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.1 Indeed, the ASTRAL study (Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions) investigators found substantial risks without evidence of a worthwhile clinical benefit from revascularization in patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease.3

Nevertheless, I believe that this procedure may benefit certain patients.

MAYO CLINIC COHORT STUDY

In 2008, our group at Mayo Clinic Health system in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, published the results of a prospective cohort study in 26 patients with renal artery stenosis and chronic kidney disease who presented with rapidly worsening renal failure (defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 25%) while receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB).6,7

These drugs—inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system—slow the progression of chronic kidney disease but can acutely worsen renal function, especially in patients with renal artery stenosis, and withdrawing them in this situation was the focus of our study.

The patients (10 men and 16 women) ranged in age from 63 to 87 (mean age 75.3).

At enrollment, the ACE inhibitors and ARBs were discontinued, standard nephrologic care was applied, and the glomerular filtration rate (estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) was monitored. After at least 2 weeks, percutaneous renal angioplasty with stent placement was considered if the patient met any of the following criteria:

- Persistence of renal failure

- Flash pulmonary edema

- Uncontrolled hypertension despite the use of at least three antihypertensive medications.

Nine patients underwent percutaneous angioplasty and stenting and 17 did not. The procedure was done on one renal artery in 8 patients and both renal arteries in 1. Indications for the procedure were recent worsening of renal failure in 8 patients and recent worsening renal failure together with symptomatic flash pulmonary edema in 1 patient. (Flash pulmonary edema is the only class I recommendation for percutaneous renal angioplasty in the 2006 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.8) As noted above, all the patients were experiencing acute exacerbation of chronic kidney disease at the time.

We found clear evidence of additional improved and sustained renal function in the patients who underwent percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting compared with the patients who did not (Figures 1 and 2).6,7

In an editorial9 following publication of the ASTRAL study, our group reported a subsequent 82-month analysis of our 26-patient cohort completed in June 2009. In the 7 surviving patients who had undergone percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting, the estimated glomerular filtration rate had increased from 27.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (± 12.7, range 11–47) at baseline to 50.3 (± 21.7, range 23–68) (P = .018) after 46.9 months.

PATIENT NUMBER 13

To illustrate how percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting can reverse recently worsening renal failure in renal artery stenosis, I would like to discuss in greater detail a patient from our two previous reports.6,7

Patient 13, a 67-year-old woman with hypertension, was referred to our nephrology service in September 2004 to consider starting hemodialysis for symptomatic renal failure. Her serum creatinine had increased to 3.4 mg/dL from a previous baseline level of 2.0 mg/dL, and she also had worsening anemia and hyperkalemia. She had been taking lisinopril 10 mg/day for the last 12 months. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed high-grade (> 95%) bilateral renal artery stenosis with an atrophic left kidney.

Lisinopril was promptly discontinued, and within 2 weeks her serum creatinine level had decreased by more than 0.5 mg/dL. In mid-November 2004, she underwent right renal artery angioplasty with stent placement. After that, her serum creatinine decreased further, and 3 months later it had dropped to 1.6 mg/dL. The value continued to improve, with the lowest measurement of 1.1 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 51 mL/min/1.73 m2. This was in May 2006, 19 months after stopping lisinopril and 17 months after angioplasty and stenting. The last available serum creatinine level (August 2006) was 1.2 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the patient died of metastatic lung cancer in December of that year.

Also of note, the patient who underwent angioplasty because of recurrent flash pulmonary edema had no recurrences of it afterward.

We concluded that, in patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis presenting with acutely worsening renal failure, renal angioplasty with stenting has the potential to reverse renal failure, improve blood pressure control, and stop flash pulmonary edema.6–8

Notably, all patients in our study who underwent renal angioplasty with stenting had new-onset acute renal injury as defined by an increase in the baseline serum creatinine of more than 25% during the 3 months before stent placement.6–8 Patients in the STAR,2 HERCULES,4 and CORAL5 studies had renal artery stenosis but otherwise stable chronic kidney disease at the time of enrollment. In the ASTRAL study,3 12% of the patients had acute kidney injury on study enrollment, defined as an increase in the serum creatinine level of more than 20% or of more than 1.13 mg/dL.3

While we strongly agree with aggressive yet monitored medical therapy for patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis, I posit that selected patients do indeed derive significant clinical benefits from renal angioplasty and stenting. Our group’s prospective individual-patient-level data support the paradigm that angioplasty with stenting is useful in patients with renal artery stenosis who experience “acute-on-chronic” kidney disease.

The pathophysiology of renal artery stenosis and the progression of chronic kidney disease are complex, and many factors affect patient outcomes and response to treatment. Thus, the message is that treatment of severe renal artery stenosis must be individualized.9–11 No one treatment fits all.10,11

In their article in this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Kabach et al answer no to the question of whether stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improves outcomes compared with medical therapy alone.1 They review the findings of four key studies2–5 published between 2003 and 2014 and conclude that, in patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting with medical therapy can improve blood pressure control but has no significant impact on cardiovascular or mortality outcomes.1

Furthermore, the authors state that in view of the risk of complications associated with stenting, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.1 Indeed, the ASTRAL study (Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions) investigators found substantial risks without evidence of a worthwhile clinical benefit from revascularization in patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease.3

Nevertheless, I believe that this procedure may benefit certain patients.

MAYO CLINIC COHORT STUDY

In 2008, our group at Mayo Clinic Health system in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, published the results of a prospective cohort study in 26 patients with renal artery stenosis and chronic kidney disease who presented with rapidly worsening renal failure (defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 25%) while receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB).6,7

These drugs—inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system—slow the progression of chronic kidney disease but can acutely worsen renal function, especially in patients with renal artery stenosis, and withdrawing them in this situation was the focus of our study.

The patients (10 men and 16 women) ranged in age from 63 to 87 (mean age 75.3).

At enrollment, the ACE inhibitors and ARBs were discontinued, standard nephrologic care was applied, and the glomerular filtration rate (estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) was monitored. After at least 2 weeks, percutaneous renal angioplasty with stent placement was considered if the patient met any of the following criteria:

- Persistence of renal failure

- Flash pulmonary edema

- Uncontrolled hypertension despite the use of at least three antihypertensive medications.

Nine patients underwent percutaneous angioplasty and stenting and 17 did not. The procedure was done on one renal artery in 8 patients and both renal arteries in 1. Indications for the procedure were recent worsening of renal failure in 8 patients and recent worsening renal failure together with symptomatic flash pulmonary edema in 1 patient. (Flash pulmonary edema is the only class I recommendation for percutaneous renal angioplasty in the 2006 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.8) As noted above, all the patients were experiencing acute exacerbation of chronic kidney disease at the time.

We found clear evidence of additional improved and sustained renal function in the patients who underwent percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting compared with the patients who did not (Figures 1 and 2).6,7

In an editorial9 following publication of the ASTRAL study, our group reported a subsequent 82-month analysis of our 26-patient cohort completed in June 2009. In the 7 surviving patients who had undergone percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting, the estimated glomerular filtration rate had increased from 27.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (± 12.7, range 11–47) at baseline to 50.3 (± 21.7, range 23–68) (P = .018) after 46.9 months.

PATIENT NUMBER 13

To illustrate how percutaneous renal angioplasty and stenting can reverse recently worsening renal failure in renal artery stenosis, I would like to discuss in greater detail a patient from our two previous reports.6,7

Patient 13, a 67-year-old woman with hypertension, was referred to our nephrology service in September 2004 to consider starting hemodialysis for symptomatic renal failure. Her serum creatinine had increased to 3.4 mg/dL from a previous baseline level of 2.0 mg/dL, and she also had worsening anemia and hyperkalemia. She had been taking lisinopril 10 mg/day for the last 12 months. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed high-grade (> 95%) bilateral renal artery stenosis with an atrophic left kidney.

Lisinopril was promptly discontinued, and within 2 weeks her serum creatinine level had decreased by more than 0.5 mg/dL. In mid-November 2004, she underwent right renal artery angioplasty with stent placement. After that, her serum creatinine decreased further, and 3 months later it had dropped to 1.6 mg/dL. The value continued to improve, with the lowest measurement of 1.1 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 51 mL/min/1.73 m2. This was in May 2006, 19 months after stopping lisinopril and 17 months after angioplasty and stenting. The last available serum creatinine level (August 2006) was 1.2 mg/dL, equivalent to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the patient died of metastatic lung cancer in December of that year.

Also of note, the patient who underwent angioplasty because of recurrent flash pulmonary edema had no recurrences of it afterward.

We concluded that, in patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis presenting with acutely worsening renal failure, renal angioplasty with stenting has the potential to reverse renal failure, improve blood pressure control, and stop flash pulmonary edema.6–8

Notably, all patients in our study who underwent renal angioplasty with stenting had new-onset acute renal injury as defined by an increase in the baseline serum creatinine of more than 25% during the 3 months before stent placement.6–8 Patients in the STAR,2 HERCULES,4 and CORAL5 studies had renal artery stenosis but otherwise stable chronic kidney disease at the time of enrollment. In the ASTRAL study,3 12% of the patients had acute kidney injury on study enrollment, defined as an increase in the serum creatinine level of more than 20% or of more than 1.13 mg/dL.3

While we strongly agree with aggressive yet monitored medical therapy for patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis, I posit that selected patients do indeed derive significant clinical benefits from renal angioplasty and stenting. Our group’s prospective individual-patient-level data support the paradigm that angioplasty with stenting is useful in patients with renal artery stenosis who experience “acute-on-chronic” kidney disease.

The pathophysiology of renal artery stenosis and the progression of chronic kidney disease are complex, and many factors affect patient outcomes and response to treatment. Thus, the message is that treatment of severe renal artery stenosis must be individualized.9–11 No one treatment fits all.10,11

- Kabach A, Agha OQ, Baibars M, Alraiyes AH, Alraies MC. Does stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improve outcomes compared with medical therapy alone? Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:491–494.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of STent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by Atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the Renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Jaff MR, Bates M, Sullivan T, et al; HERCULES Investigators. Significant reduction in systolic blood pressure following renal artery stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results from the HERCULES trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80:343–350.

- Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, et al; CORAL Investigators. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:13–22.

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo NTC. Worsening renal failure in older chronic kidney disease patients with renal artery stenosis concurrently on renin angiotensin aldosterone system blockade: a prospective 50-month Mayo Health System clinic analysis. QJM 2008; 101:519–527.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo NT. Renal failure and concurrent RAAS blockade in older CKD patients with renal artery stenosis: an extended Mayo Clinic prospective 63-month experience. Ren Fail 2008; 30:363–371.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

- Onuigbo M, Frenandes R, Nijhawan V. The ASTRAL trial results revisited—to stent or not to stent in renal artery stenosis? QJM 2010; 103:357.

- Singh M, Kovacs DF, Singh A, Dhaliwal P, Khosla S. ACE inhibition and renal artery stenosis: what lessons have we learnt? A 21st century perspective. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 2. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013:203–218.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo C, Onuigbo V, et al. The CKD enigma, reengineering CKD care, narrowing asymmetric information and confronting ethicomedicinomics in CKD care: the introduction of the new 'CKD express©' IT software program. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE Inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 1. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013: 41–56.

- Kabach A, Agha OQ, Baibars M, Alraiyes AH, Alraies MC. Does stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improve outcomes compared with medical therapy alone? Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:491–494.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of STent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by Atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the Renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Jaff MR, Bates M, Sullivan T, et al; HERCULES Investigators. Significant reduction in systolic blood pressure following renal artery stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results from the HERCULES trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80:343–350.

- Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, et al; CORAL Investigators. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:13–22.

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo NTC. Worsening renal failure in older chronic kidney disease patients with renal artery stenosis concurrently on renin angiotensin aldosterone system blockade: a prospective 50-month Mayo Health System clinic analysis. QJM 2008; 101:519–527.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo NT. Renal failure and concurrent RAAS blockade in older CKD patients with renal artery stenosis: an extended Mayo Clinic prospective 63-month experience. Ren Fail 2008; 30:363–371.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

- Onuigbo M, Frenandes R, Nijhawan V. The ASTRAL trial results revisited—to stent or not to stent in renal artery stenosis? QJM 2010; 103:357.

- Singh M, Kovacs DF, Singh A, Dhaliwal P, Khosla S. ACE inhibition and renal artery stenosis: what lessons have we learnt? A 21st century perspective. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 2. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013:203–218.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo C, Onuigbo V, et al. The CKD enigma, reengineering CKD care, narrowing asymmetric information and confronting ethicomedicinomics in CKD care: the introduction of the new 'CKD express©' IT software program. In: Onuigbo MAC, ed. ACE Inhibitors: Medical Uses, Mechanisms of Action, Potential Adverse Effects and Related Topics. Volume 1. New York, NY: NOVA Publishers; 2013: 41–56.

SVS: AAA reimbursement needs to take anatomic complexity into account

CHICAGO – Anatomic complexity should be factored into reimbursements for abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs, University of Rochester (N.Y.) investigators concluded after they compared costs to complexity in 33 open and 107 endovascular repairs during 2007-2010.

They found that complex aneurysms – especially ones with Anatomic Severity Grade (ASG) scores above 15 – need more adjunctive procedures and cost more to repair, although at the moment, payers don’t usually take complexity directly into account.

It’s the first study to show a direct relationship between anatomic complexity and hospital cost. “Preoperative assessment with ASG scores can delineate patients at greater risk for increased resource utilization. A critical examination of the relationship between anatomic complexity and finances is required within the context of aggressive endovascular treatment strategies and shifts towards value-based reimbursement. Anatomy is related to cost. [Complexity] should be considered as a factor when calculating limited bundle reimbursements,” said investigator Dr. Khurram Rasheed, a vascular surgery resident in Rochester.

Developed by the Society for Vascular Surgery, the ASG is an assessment of the aortic neck, aneurysm body, iliac arteries, and pelvic perfusion for 16 parameters, including angles, calcifications, and tortuosity. Each parameter is scored from 0-3. Higher scores mean greater complexity, with 48 being the highest possible score (J. Vasc. Surg. 2002;35:1061-6).

An ASG of 15 proved to be a handy marker for when complexity starts to affect the bottom line. A score of 15 or higher correlated with increased costs and increased propensity for requiring intraoperative adjuncts such as renal artery stenting (odds ratio, 5.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.82-18.19). It also correlated with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease, meaning that sicker patients were likely to have worse anatomy and cost more to repair, Dr. Rasheed reported at the meeting hosted by the Society for Special Surgery.

All the cases in the study were elective, and the majority of the patients were elderly white men.

The mean total-cost of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) was $24,701, mean length of stay (LOS) of 3.0 days, and mean ASG score of 15.9. Cases below an ASG score of 15 cost a mean of $22,020 and had a mean LOS of 2.93 days. Above 15, the mean cost was $26,574 and mean LOS was 3.07 days.

About a quarter of EVAR patients required intraoperative adjuncts, most above an ASG score of 15; their cases cost a mean of $31,509, with a mean ASG score of 18.48 and LOS of 3.85 days.

For open repair, the mean total cost was $38,310, LOS of 13.5 days, and ASG score of 18.1. When five patients with unusually long hospital stays were excluded, open repair cost less than EVAR, which is consistent with previous reports. Just two open-repair patients (6%) needed adjunct procedures.

Open-repair cases with an ASG score below 15 cost a mean of $24,508 and had a mean LOS of 10 days. Cases with a higher score cost a mean of $41,071 and stayed in the hospital an average of 14.2 days. Despite trends, the ASG score differences in cost and LOS for open-repair cases did not reach statistical significance; type II error was probably to blame, Dr. Rasheed said.

The investigators have no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Anatomic complexity should be factored into reimbursements for abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs, University of Rochester (N.Y.) investigators concluded after they compared costs to complexity in 33 open and 107 endovascular repairs during 2007-2010.

They found that complex aneurysms – especially ones with Anatomic Severity Grade (ASG) scores above 15 – need more adjunctive procedures and cost more to repair, although at the moment, payers don’t usually take complexity directly into account.

It’s the first study to show a direct relationship between anatomic complexity and hospital cost. “Preoperative assessment with ASG scores can delineate patients at greater risk for increased resource utilization. A critical examination of the relationship between anatomic complexity and finances is required within the context of aggressive endovascular treatment strategies and shifts towards value-based reimbursement. Anatomy is related to cost. [Complexity] should be considered as a factor when calculating limited bundle reimbursements,” said investigator Dr. Khurram Rasheed, a vascular surgery resident in Rochester.

Developed by the Society for Vascular Surgery, the ASG is an assessment of the aortic neck, aneurysm body, iliac arteries, and pelvic perfusion for 16 parameters, including angles, calcifications, and tortuosity. Each parameter is scored from 0-3. Higher scores mean greater complexity, with 48 being the highest possible score (J. Vasc. Surg. 2002;35:1061-6).

An ASG of 15 proved to be a handy marker for when complexity starts to affect the bottom line. A score of 15 or higher correlated with increased costs and increased propensity for requiring intraoperative adjuncts such as renal artery stenting (odds ratio, 5.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.82-18.19). It also correlated with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease, meaning that sicker patients were likely to have worse anatomy and cost more to repair, Dr. Rasheed reported at the meeting hosted by the Society for Special Surgery.

All the cases in the study were elective, and the majority of the patients were elderly white men.

The mean total-cost of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) was $24,701, mean length of stay (LOS) of 3.0 days, and mean ASG score of 15.9. Cases below an ASG score of 15 cost a mean of $22,020 and had a mean LOS of 2.93 days. Above 15, the mean cost was $26,574 and mean LOS was 3.07 days.

About a quarter of EVAR patients required intraoperative adjuncts, most above an ASG score of 15; their cases cost a mean of $31,509, with a mean ASG score of 18.48 and LOS of 3.85 days.

For open repair, the mean total cost was $38,310, LOS of 13.5 days, and ASG score of 18.1. When five patients with unusually long hospital stays were excluded, open repair cost less than EVAR, which is consistent with previous reports. Just two open-repair patients (6%) needed adjunct procedures.

Open-repair cases with an ASG score below 15 cost a mean of $24,508 and had a mean LOS of 10 days. Cases with a higher score cost a mean of $41,071 and stayed in the hospital an average of 14.2 days. Despite trends, the ASG score differences in cost and LOS for open-repair cases did not reach statistical significance; type II error was probably to blame, Dr. Rasheed said.

The investigators have no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Anatomic complexity should be factored into reimbursements for abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs, University of Rochester (N.Y.) investigators concluded after they compared costs to complexity in 33 open and 107 endovascular repairs during 2007-2010.

They found that complex aneurysms – especially ones with Anatomic Severity Grade (ASG) scores above 15 – need more adjunctive procedures and cost more to repair, although at the moment, payers don’t usually take complexity directly into account.

It’s the first study to show a direct relationship between anatomic complexity and hospital cost. “Preoperative assessment with ASG scores can delineate patients at greater risk for increased resource utilization. A critical examination of the relationship between anatomic complexity and finances is required within the context of aggressive endovascular treatment strategies and shifts towards value-based reimbursement. Anatomy is related to cost. [Complexity] should be considered as a factor when calculating limited bundle reimbursements,” said investigator Dr. Khurram Rasheed, a vascular surgery resident in Rochester.

Developed by the Society for Vascular Surgery, the ASG is an assessment of the aortic neck, aneurysm body, iliac arteries, and pelvic perfusion for 16 parameters, including angles, calcifications, and tortuosity. Each parameter is scored from 0-3. Higher scores mean greater complexity, with 48 being the highest possible score (J. Vasc. Surg. 2002;35:1061-6).

An ASG of 15 proved to be a handy marker for when complexity starts to affect the bottom line. A score of 15 or higher correlated with increased costs and increased propensity for requiring intraoperative adjuncts such as renal artery stenting (odds ratio, 5.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.82-18.19). It also correlated with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease, meaning that sicker patients were likely to have worse anatomy and cost more to repair, Dr. Rasheed reported at the meeting hosted by the Society for Special Surgery.

All the cases in the study were elective, and the majority of the patients were elderly white men.

The mean total-cost of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) was $24,701, mean length of stay (LOS) of 3.0 days, and mean ASG score of 15.9. Cases below an ASG score of 15 cost a mean of $22,020 and had a mean LOS of 2.93 days. Above 15, the mean cost was $26,574 and mean LOS was 3.07 days.

About a quarter of EVAR patients required intraoperative adjuncts, most above an ASG score of 15; their cases cost a mean of $31,509, with a mean ASG score of 18.48 and LOS of 3.85 days.

For open repair, the mean total cost was $38,310, LOS of 13.5 days, and ASG score of 18.1. When five patients with unusually long hospital stays were excluded, open repair cost less than EVAR, which is consistent with previous reports. Just two open-repair patients (6%) needed adjunct procedures.

Open-repair cases with an ASG score below 15 cost a mean of $24,508 and had a mean LOS of 10 days. Cases with a higher score cost a mean of $41,071 and stayed in the hospital an average of 14.2 days. Despite trends, the ASG score differences in cost and LOS for open-repair cases did not reach statistical significance; type II error was probably to blame, Dr. Rasheed said.

The investigators have no disclosures.

AT THE 2015 VASCULAR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Get the hang of calculating Anatomic Severity Grade scores on your triple A cases; it might one day increase your reimbursements.

Major finding: EVAR cases below an ASG score of 15 cost a mean of $22,020 and had a length of stay of 2.93 days. Above 15, the cost was $26,574 and mean LOS was 3.07 days.

Data source: Review of 33 open and 107 endovascular repairs at the University of Rochester in New York.

Disclosures: The investigators have no disclosures.

SVS: Beta-blockers cut stroke, death risk in carotid stenting

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to non-users, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005]. Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with post-procedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think” the benefits are due to “up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days. There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average age in the study was about 70 years old.

Overall, the 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.4% (minor stroke 1.5%, major 0.9%, and death 1.2%).

Predictors of postoperative stroke or death at 30 days included symptomatic status, age, diabetes, and perioperative hypotension and hypertension. Prior carotid endarterectomy and distal embolic protection were both protective.

The investigators have no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to non-users, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005]. Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with post-procedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think” the benefits are due to “up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days. There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average age in the study was about 70 years old.

Overall, the 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.4% (minor stroke 1.5%, major 0.9%, and death 1.2%).

Predictors of postoperative stroke or death at 30 days included symptomatic status, age, diabetes, and perioperative hypotension and hypertension. Prior carotid endarterectomy and distal embolic protection were both protective.

The investigators have no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to non-users, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005]. Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with post-procedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think” the benefits are due to “up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days. There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average age in the study was about 70 years old.