User login

Reattaching intercostals fails to squelch spinal cord ischemia in TAAA repairs

CHICAGO – Intercostal artery reimplantation fails to significantly reduce spinal cord injury following thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, results of a large retrospective study show.

“Although there was a small decrease in spinal cord ischemia with ICAR, reattaching the intercostals did not produce a statistically significant reduction in spinal cord ischemia, even in the highest risk patients,” Dr. Charles W. Acher of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Intercostal artery reimplantation (ICAR) is one of several strategies that have been used to prevent spinal cord ischemia (SCI), paraplegia, and paraparesis that occurs from the interruption of the blood supply to intercostal arteries (ICAs) during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair.

Surgeons at UW–Madison adopted the ICAR strategy in 2005and now reimplant open ICAs located at T7-L2 in all Type I, II, and III TAAAs, using a previously published technique (J Surg Res. 2009;154:99-104).

Using a prospectively maintained database, the current analysis sought to compare outcomes between 540 patients who had TAAA surgery during 1989-2004 when open ICAs were ligated and 265 patients who had surgery during 2005-2013 with ICAR.The surgical technique for both groups was cross clamp without assisted circulation. The anesthetic technique was also uniform during the study period and included moderate systemic hypothermia (32° - 33° C); spinal fluid drainage (spinal fluid pressure less than 5 mm Hg); naloxone 1 mcg/kg per hour; use of mannitol, methylprednisolone, and barbiturate burst suppression; goal-directed therapy for a mean arterial pressure of 90-100 mm Hg and cardiac index of 2.5 L per minute/meter2; and proactive component blood therapy to avoid anemia, hypovolemia, and hypertension.

Aneurysm extent, acuity, mortality, renal failure, and pulmonary failure were the same in both groups.

The incidence of SCI was similar in all TAAAs at 5.25% without ICAR and 3.4% with ICAR (P = .23) and in the subset of patients with Type I, II, and III aneurysms (8.8% vs. 5.1%; P = .152), Dr. Acher reported on behalf of lead author and his colleague, Dr. Martha M. Wynn.

Interestingly, ICAR patients had more dissections than did the open ICA ligation patients (18% vs. 15%; P = .0016), more previous aortic surgery (47% vs. 31%; P = .0004), and longer renal ischemia time (61 minutes vs. 53 minutes; P = .0001), but had a shorter length of stay (14 days vs. 22 days; P = .0001) and were younger (mean age, 66 years vs. 70 years; P = .0001).

In a multivariate model of all TAAAs, significant predictors of spinal cord ischemia/injury were type II TAAA (odds ratio, 7.59; P = .0001), dissection (OR, 4.25; P = .0015), age as a continuous variable (P = .0085), and acute TAAA (OR, 2.1; P = .0525), Dr. Acher said. Time period of surgery, and therefore ICAR, was not significant (OR, 0.78; P = .55).

ICAR also failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor in a subanalysis restricted to the highest-risk patients, defined as those having Type II TAAA, dissection, and acute surgery (OR, 0.67; P = .3387).

“Interrupting blood supply to the spinal cord causes spinal cord ischemia that can be mitigated almost entirely by physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord ischemic tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery,” Dr. Acher said. “Although the cause of SCI in TAAA surgery is anatomic, prevention of the injury is largely physiologic.”

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Acher surprised the audience by saying the findings have not changed current practice at the university. He cited several reasons, observing that there were more dissections in the ICAR group, and most of the ischemia in the ICAR group was delayed, suggesting that more patients could be rescued. In addition, there was a slight downward trend in spinal cord injury and immediate paraplegia with ICAR, however, these were not statistically significant.

“Because of those things, I still think it’s valuable, particularly in patients that are at highest risk, which are the dissections, with lots of open intercostals, but the emphasis should still be on physiologic parameters,” he said. “If you want to salvage patients, that’s the most important thing.

“Even if ICAR were ever shown to be statistically significant in a larger patient population, any role it has in reducing spinal cord injury would be extremely small,” he added in an interview.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Spinal cord ischemia is a rare but devastating complication of thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Crawford and his colleagues documented in 1993 an incidence of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) as high as 30% for extensive thoracoabdominal repairs. Efforts to diminish the risk of SCI were concentrated in identifying and preserving the direct arterial perfusion to the spinal cord from segmental arteries but continued experimental and clinical experience have suggested that multiple factors contribute to SCI.

|

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez |

Some generally accepted principles for minimizing SCI include hypothermia, distal aortic perfusion with atriofemoral bypass or partial cardiopulmonary bypass, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and avoidance of hemodynamic instability. Reimplantation of intercostal branches has been suggested as an adjunct to these techniques by some investigators with limited data to support its generalized application. More recently, a growing body of evidence supports the concept of a collateral network that can support the perfusion to the spinal cord after interruption of multiple intercostal arteries and the importance of the hypogastric and subclavian arteries as critical branches that perfuse the spinal collateral network.

The retrospective review of the extensive experience at the University of Wisconsin in Madison supports the concept that “physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery” are more important than the reimplantation of intercostal vessels during this complex procedure, even in patients considered at the highest risk for SCI. Intercostal artery reimplantation failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor when comparing two large cohorts of patients (540 vs. 265) treated with intercostal ligation vs. reimplantation. Increasingly, available data support the concept of a collateral network that maintains perfusion to the spinal cord after intercostal artery occlusion.

Additional new concepts and techniques including a two-stage approach for extensive thoracoabdominal repair, preliminary occlusion of some segmental arteries, and the use of hybrid and endovascular techniques may further decrease the incidence of SCI by taking advantage of the collateral network and allow some preconditioning of the spinal cord. Fortunately for these challenging patients, significant advances continue to be made to better understand and prevent spinal cord ischemia.

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez is Chief, Section of Vascular Surgery and the Gregorio A. Sicard Distinguished Professor of Surgery and Radiology, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

Spinal cord ischemia is a rare but devastating complication of thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Crawford and his colleagues documented in 1993 an incidence of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) as high as 30% for extensive thoracoabdominal repairs. Efforts to diminish the risk of SCI were concentrated in identifying and preserving the direct arterial perfusion to the spinal cord from segmental arteries but continued experimental and clinical experience have suggested that multiple factors contribute to SCI.

|

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez |

Some generally accepted principles for minimizing SCI include hypothermia, distal aortic perfusion with atriofemoral bypass or partial cardiopulmonary bypass, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and avoidance of hemodynamic instability. Reimplantation of intercostal branches has been suggested as an adjunct to these techniques by some investigators with limited data to support its generalized application. More recently, a growing body of evidence supports the concept of a collateral network that can support the perfusion to the spinal cord after interruption of multiple intercostal arteries and the importance of the hypogastric and subclavian arteries as critical branches that perfuse the spinal collateral network.

The retrospective review of the extensive experience at the University of Wisconsin in Madison supports the concept that “physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery” are more important than the reimplantation of intercostal vessels during this complex procedure, even in patients considered at the highest risk for SCI. Intercostal artery reimplantation failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor when comparing two large cohorts of patients (540 vs. 265) treated with intercostal ligation vs. reimplantation. Increasingly, available data support the concept of a collateral network that maintains perfusion to the spinal cord after intercostal artery occlusion.

Additional new concepts and techniques including a two-stage approach for extensive thoracoabdominal repair, preliminary occlusion of some segmental arteries, and the use of hybrid and endovascular techniques may further decrease the incidence of SCI by taking advantage of the collateral network and allow some preconditioning of the spinal cord. Fortunately for these challenging patients, significant advances continue to be made to better understand and prevent spinal cord ischemia.

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez is Chief, Section of Vascular Surgery and the Gregorio A. Sicard Distinguished Professor of Surgery and Radiology, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

Spinal cord ischemia is a rare but devastating complication of thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Crawford and his colleagues documented in 1993 an incidence of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) as high as 30% for extensive thoracoabdominal repairs. Efforts to diminish the risk of SCI were concentrated in identifying and preserving the direct arterial perfusion to the spinal cord from segmental arteries but continued experimental and clinical experience have suggested that multiple factors contribute to SCI.

|

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez |

Some generally accepted principles for minimizing SCI include hypothermia, distal aortic perfusion with atriofemoral bypass or partial cardiopulmonary bypass, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and avoidance of hemodynamic instability. Reimplantation of intercostal branches has been suggested as an adjunct to these techniques by some investigators with limited data to support its generalized application. More recently, a growing body of evidence supports the concept of a collateral network that can support the perfusion to the spinal cord after interruption of multiple intercostal arteries and the importance of the hypogastric and subclavian arteries as critical branches that perfuse the spinal collateral network.

The retrospective review of the extensive experience at the University of Wisconsin in Madison supports the concept that “physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery” are more important than the reimplantation of intercostal vessels during this complex procedure, even in patients considered at the highest risk for SCI. Intercostal artery reimplantation failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor when comparing two large cohorts of patients (540 vs. 265) treated with intercostal ligation vs. reimplantation. Increasingly, available data support the concept of a collateral network that maintains perfusion to the spinal cord after intercostal artery occlusion.

Additional new concepts and techniques including a two-stage approach for extensive thoracoabdominal repair, preliminary occlusion of some segmental arteries, and the use of hybrid and endovascular techniques may further decrease the incidence of SCI by taking advantage of the collateral network and allow some preconditioning of the spinal cord. Fortunately for these challenging patients, significant advances continue to be made to better understand and prevent spinal cord ischemia.

Dr. Luis A. Sanchez is Chief, Section of Vascular Surgery and the Gregorio A. Sicard Distinguished Professor of Surgery and Radiology, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

CHICAGO – Intercostal artery reimplantation fails to significantly reduce spinal cord injury following thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, results of a large retrospective study show.

“Although there was a small decrease in spinal cord ischemia with ICAR, reattaching the intercostals did not produce a statistically significant reduction in spinal cord ischemia, even in the highest risk patients,” Dr. Charles W. Acher of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Intercostal artery reimplantation (ICAR) is one of several strategies that have been used to prevent spinal cord ischemia (SCI), paraplegia, and paraparesis that occurs from the interruption of the blood supply to intercostal arteries (ICAs) during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair.

Surgeons at UW–Madison adopted the ICAR strategy in 2005and now reimplant open ICAs located at T7-L2 in all Type I, II, and III TAAAs, using a previously published technique (J Surg Res. 2009;154:99-104).

Using a prospectively maintained database, the current analysis sought to compare outcomes between 540 patients who had TAAA surgery during 1989-2004 when open ICAs were ligated and 265 patients who had surgery during 2005-2013 with ICAR.The surgical technique for both groups was cross clamp without assisted circulation. The anesthetic technique was also uniform during the study period and included moderate systemic hypothermia (32° - 33° C); spinal fluid drainage (spinal fluid pressure less than 5 mm Hg); naloxone 1 mcg/kg per hour; use of mannitol, methylprednisolone, and barbiturate burst suppression; goal-directed therapy for a mean arterial pressure of 90-100 mm Hg and cardiac index of 2.5 L per minute/meter2; and proactive component blood therapy to avoid anemia, hypovolemia, and hypertension.

Aneurysm extent, acuity, mortality, renal failure, and pulmonary failure were the same in both groups.

The incidence of SCI was similar in all TAAAs at 5.25% without ICAR and 3.4% with ICAR (P = .23) and in the subset of patients with Type I, II, and III aneurysms (8.8% vs. 5.1%; P = .152), Dr. Acher reported on behalf of lead author and his colleague, Dr. Martha M. Wynn.

Interestingly, ICAR patients had more dissections than did the open ICA ligation patients (18% vs. 15%; P = .0016), more previous aortic surgery (47% vs. 31%; P = .0004), and longer renal ischemia time (61 minutes vs. 53 minutes; P = .0001), but had a shorter length of stay (14 days vs. 22 days; P = .0001) and were younger (mean age, 66 years vs. 70 years; P = .0001).

In a multivariate model of all TAAAs, significant predictors of spinal cord ischemia/injury were type II TAAA (odds ratio, 7.59; P = .0001), dissection (OR, 4.25; P = .0015), age as a continuous variable (P = .0085), and acute TAAA (OR, 2.1; P = .0525), Dr. Acher said. Time period of surgery, and therefore ICAR, was not significant (OR, 0.78; P = .55).

ICAR also failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor in a subanalysis restricted to the highest-risk patients, defined as those having Type II TAAA, dissection, and acute surgery (OR, 0.67; P = .3387).

“Interrupting blood supply to the spinal cord causes spinal cord ischemia that can be mitigated almost entirely by physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord ischemic tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery,” Dr. Acher said. “Although the cause of SCI in TAAA surgery is anatomic, prevention of the injury is largely physiologic.”

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Acher surprised the audience by saying the findings have not changed current practice at the university. He cited several reasons, observing that there were more dissections in the ICAR group, and most of the ischemia in the ICAR group was delayed, suggesting that more patients could be rescued. In addition, there was a slight downward trend in spinal cord injury and immediate paraplegia with ICAR, however, these were not statistically significant.

“Because of those things, I still think it’s valuable, particularly in patients that are at highest risk, which are the dissections, with lots of open intercostals, but the emphasis should still be on physiologic parameters,” he said. “If you want to salvage patients, that’s the most important thing.

“Even if ICAR were ever shown to be statistically significant in a larger patient population, any role it has in reducing spinal cord injury would be extremely small,” he added in an interview.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Intercostal artery reimplantation fails to significantly reduce spinal cord injury following thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, results of a large retrospective study show.

“Although there was a small decrease in spinal cord ischemia with ICAR, reattaching the intercostals did not produce a statistically significant reduction in spinal cord ischemia, even in the highest risk patients,” Dr. Charles W. Acher of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Intercostal artery reimplantation (ICAR) is one of several strategies that have been used to prevent spinal cord ischemia (SCI), paraplegia, and paraparesis that occurs from the interruption of the blood supply to intercostal arteries (ICAs) during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair.

Surgeons at UW–Madison adopted the ICAR strategy in 2005and now reimplant open ICAs located at T7-L2 in all Type I, II, and III TAAAs, using a previously published technique (J Surg Res. 2009;154:99-104).

Using a prospectively maintained database, the current analysis sought to compare outcomes between 540 patients who had TAAA surgery during 1989-2004 when open ICAs were ligated and 265 patients who had surgery during 2005-2013 with ICAR.The surgical technique for both groups was cross clamp without assisted circulation. The anesthetic technique was also uniform during the study period and included moderate systemic hypothermia (32° - 33° C); spinal fluid drainage (spinal fluid pressure less than 5 mm Hg); naloxone 1 mcg/kg per hour; use of mannitol, methylprednisolone, and barbiturate burst suppression; goal-directed therapy for a mean arterial pressure of 90-100 mm Hg and cardiac index of 2.5 L per minute/meter2; and proactive component blood therapy to avoid anemia, hypovolemia, and hypertension.

Aneurysm extent, acuity, mortality, renal failure, and pulmonary failure were the same in both groups.

The incidence of SCI was similar in all TAAAs at 5.25% without ICAR and 3.4% with ICAR (P = .23) and in the subset of patients with Type I, II, and III aneurysms (8.8% vs. 5.1%; P = .152), Dr. Acher reported on behalf of lead author and his colleague, Dr. Martha M. Wynn.

Interestingly, ICAR patients had more dissections than did the open ICA ligation patients (18% vs. 15%; P = .0016), more previous aortic surgery (47% vs. 31%; P = .0004), and longer renal ischemia time (61 minutes vs. 53 minutes; P = .0001), but had a shorter length of stay (14 days vs. 22 days; P = .0001) and were younger (mean age, 66 years vs. 70 years; P = .0001).

In a multivariate model of all TAAAs, significant predictors of spinal cord ischemia/injury were type II TAAA (odds ratio, 7.59; P = .0001), dissection (OR, 4.25; P = .0015), age as a continuous variable (P = .0085), and acute TAAA (OR, 2.1; P = .0525), Dr. Acher said. Time period of surgery, and therefore ICAR, was not significant (OR, 0.78; P = .55).

ICAR also failed to achieve significance as an SCI predictor in a subanalysis restricted to the highest-risk patients, defined as those having Type II TAAA, dissection, and acute surgery (OR, 0.67; P = .3387).

“Interrupting blood supply to the spinal cord causes spinal cord ischemia that can be mitigated almost entirely by physiologic interventions that increase spinal cord ischemic tolerance and collateral network perfusion during and after surgery,” Dr. Acher said. “Although the cause of SCI in TAAA surgery is anatomic, prevention of the injury is largely physiologic.”

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Acher surprised the audience by saying the findings have not changed current practice at the university. He cited several reasons, observing that there were more dissections in the ICAR group, and most of the ischemia in the ICAR group was delayed, suggesting that more patients could be rescued. In addition, there was a slight downward trend in spinal cord injury and immediate paraplegia with ICAR, however, these were not statistically significant.

“Because of those things, I still think it’s valuable, particularly in patients that are at highest risk, which are the dissections, with lots of open intercostals, but the emphasis should still be on physiologic parameters,” he said. “If you want to salvage patients, that’s the most important thing.

“Even if ICAR were ever shown to be statistically significant in a larger patient population, any role it has in reducing spinal cord injury would be extremely small,” he added in an interview.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2015

Key clinical point: Intercostal artery reimplantation (ICAR) did not produce a significant reduction in spinal cord ischemia following thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, even in the highest risk patients.

Major finding: ICAR was not a significant predictor of spinal cord ischemia (OR, 0.78; P = .55).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 805 patients undergoing TAAA with or without ICAR.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Genitourinary manifestations of sickle cell disease

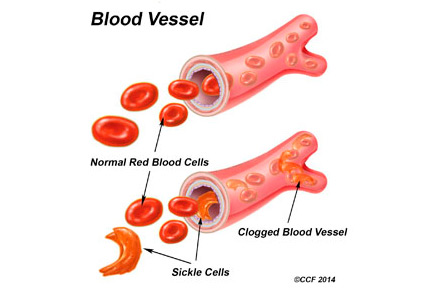

Sickle cell disease is a common genetic disorder in the United States that disproportionately affects people of African ancestry. The characteristic sickling of red blood cells under conditions of reduced oxygen tension leads to intravascular hemolysis and vaso-occlusive events, which in turn cause tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury affecting multiple organs, including the genitourinary system.1–3

In this paper, we review the genitourinary effects of sickle cell disease, focusing on sickle cell nephropathy, priapism, and renal medullary carcinoma.

THE WIDE-RANGING EFFECTS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

In the United States, sickle cell disease affects 1 of every 500 blacks and 1 of every 36,000 Hispanics.1 The term describes hemoglobinopathies associated with sickling of red blood cells.

Sickling of red blood cells results from a single base-pair change in the beta-globin gene from glutamic acid to valine at position 6, causing abnormal hemoglobin (hemoglobin S), which polymerizes under conditions of reduced oxygen tension and alters the biconcave disk shape into a rigid, irregular, unstable cell. The sickle-shaped cells are prone to intravascular hemolysis,2 causing intermittent vaso-occlusive events that result in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Genitourinary problems include impaired ability to concentrate urine, hematuria, renal medullary carcinoma, and increased frequency of urinary tract infection.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The kidney is one of the most frequently affected organs in sickle cell disease. Renal manifestations begin to appear in early childhood, with impaired medullary concentrating ability and ischemic damage to the tubular cells caused by sickling within the vasa recta renis precipitated by the acidic, hypoxic, and hypertonic environment in the renal medulla.

As in early diabetic nephropathy, renal blood flow is enhanced and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased. Increased cardiac output as a result of anemia, localized release of prostaglandins, and a hypoxia-induced increase in nitric oxide synthesis all play a role in the increase in GFR.4,5

Oxidative stress, an increase in markers of inflammation, and local activation of the renin-angiotensin system contribute to renal damage in sickle cell disease.5–7 The resulting hyperfiltration injury leads to microalbuminuria, which occurs in 20% to 40% of children with sickle cell anemia8,9 and in as many as 60% of adults.

The glomerular lesions associated with sickle cell disease vary from glomerulopathy in the early stages to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Clinical presentations and workup

Clinical presentations are not limited to glomerular disease but include hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from defects in potassium secretion and renal acidification.

Hyperphosphatemia—a result of increased reabsorption of phosphorus, increased secretion of uric acid, and increased creatinine clearance—is seen in patients with sickle cell disease.11,12 About 10% of patients can develop an acute kidney injury as a result of volume depletion, rhabdomyolysis, renal vein thrombosis, papillary necrosis, and urinary tract obstruction secondary to blood clots.11,13

Up to 30% of adult patients with sickle cell disease develop chronic kidney disease. Predictors include severe anemia, hypertension, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic hematuria.14 From 4% to 12% of patients go on to develop end-stage renal disease, but with a 1-year mortality rate three times higher than in patients without sickle cell disease.15

In general, patients with sickle cell anemia have blood pressures below those of age- and sex-matched individuals, but elevated blood pressure and low GFR are not uncommon in affected children. In a cohort of 48 children ages 3 to 18, 8.3% had an estimated GFR less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 16.7% had elevated blood pressure (prehypertension and hypertension).16

In patients with sickle cell disease, evaluation of proteinuria, hematuria, hypertension, and renal failure should take into consideration the unique renal physiologic and pathologic processes involved. Recent evidence17,18 suggests that the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation provides a better estimate of GFR than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations, although all three creatinine-based methods overestimate GFR in patients with sickle cell disease when compared with GFR measured with technetium-99m-labeled diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renal scanning.

Treatment options

Treatment of sickle cell nephropathy includes adequate fluid intake (given the loss of concentrating ability), adequate blood pressure control, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have microalbuminuria or proteinuria (or both)9,11,19 and hydroxyurea. Treatment with enalapril has been shown to decrease proteinuria in patients with sickle cell nephropathy.9 In a cohort of children with sickle cell disease, four of nine patients treated with an ACE inhibitor developed hyperkalemia, leading to discontinuation of the drug in three patients.9

ACE inhibitors and ARBs must be used cautiously in these patients because they have defects in potassium secretion. Hydroxyurea has also been shown to decrease hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in recent studies,20,21 and this could protect against the development of overt nephropathy.

Higher mortality rates have been reported in patients with sickle cell disease who developed end-stage renal disease than in patients with end-stage renal disease without sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease also increases the risk of pulmonary hypertension and the vaso-occlusive complication known as acute chest syndrome, contributing to increased mortality rates. Of note, in a study that looked at the association between mortality rates and pre-end-stage care of renal disease using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, patients with sickle cell disease who had had predialysis nephrology care had lower mortality rates.15

Treatments for end-stage renal disease are also effective in patients with sickle cell disease and include hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplantation. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing show that from 2000 to 2011, African American kidney recipients with sickle cell disease had better survival rates than patients who had undergone transplantation from 1988 to 1999, although rates of long-term survival and graft survival were lower than in transplant recipients with other diagnoses.22

It is important to note that complications as a result of vaso-occlusive events and thrombosis can lead to graft loss; therefore, sickle cell crisis after transplantation requires careful management.

Take-home messages

- Loss of urine-concentrating ability and hyperfiltration are the earliest pathologic changes in sickle cell disease.

- Microalbuminuria as seen in diabetic nephropathy is the earliest manifestation of sickle cell nephropathy, and the prevalence increases as these patients get older and live longer.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be used with caution, given the heightened risk of hyperkalemia in sickle cell disease.

- Recent results with hydroxyurea in decreasing hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria are encouraging.

- Early referral for predialysis nephrologic care is needed in sickle cell patients with chronic kidney disease.

PRIAPISM IN SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Priapism was formerly defined as a full, painful erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm. But priapism is now recognized as two separate disorders—ischemic (veno-occlusive, low-flow) priapism and nonischemic (arterial, high-flow) priapism. The new definition includes both disorders: ie, a full or partial erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm.

Ischemic priapism

Hematologic disorders are major contributors to ischemic priapism and include sickle cell disease, multiple myeloma, fat emboli (hyperalimentation),23 glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and hemoglobin Olmsted variant.24

Ischemic priapism is often seen in sickle cell disease and is considered an emergency. It is characterized by an abnormally rigid erection not involving the glans penis. Entrapment of blood in the corpora cavernosa leads to hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis, which in turn leads to a painful compartment syndrome that, if untreated, results in smooth muscle necrosis and subsequent fibrosis. The results are a smaller penis and erectile dysfunction that is unresponsive to any treatment other than implantation of a penile prosthesis. However, scarring of the corpora cavernosa can make this procedure exceedingly difficult, requiring advanced techniques such as corporeal excavation.25

Men with a subtype of ischemic priapism called “stuttering” priapism26 suffer recurrent prolonged erections during sleep. The patient awakens with a painful erection that usually subsides, but sometimes only after several hours. Patients with this disorder suffer from sleep deprivation. Stuttering priapism may lead to full-blown ischemic priapism that does not resolve without intervention.

Nonischemic priapism

In nonischemic priapism, the corpora are engorged but not rigid. The condition results from unregulated arterial inflow and thus is not painful and does not result in damage to the corporeal smooth muscle.

Most cases of nonischemic priapism follow blunt perineal trauma or trauma associated with needle insertion into the corpora. This form of priapism is not associated with sickle cell disease. Because tissue damage does not occur, nonischemic or arterial priapism is not considered an emergency.

Treatment guidelines

Differentiating ischemic from nonischemic priapism is usually straightforward, based on the history, physical examination, corporeal blood gases, and duplex ultrasonography.27

Ischemic priapism is an emergency. After needle aspiration of blood from the corpora cavernosa, phenylephrine is diluted with normal saline to a concentration of 100 to 500 µg/mL and is injected in 1-mL amounts repeatedly at 3- to 5-minute intervals until the erection subsides or until a 1-hour time limit is reached. Blood pressure and pulse are monitored during these injections. If aspiration and phenylephrine irrigation fail, surgical shunting is performed.27

Measures to treat sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions) may be employed simultaneously but should never delay aspiration and phenylephrine injections.25

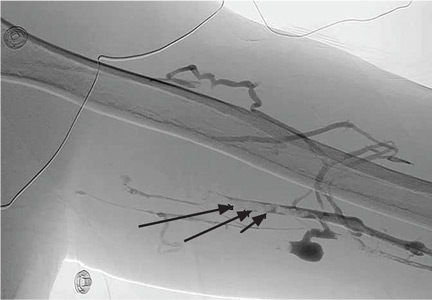

As nonischemic priapism is not considered an emergency, management begins with observation. Patients eventually become dissatisfied with their constant partial erection, and they then present for treatment. Most cases resolve after selective catheterization of the internal pudendal artery and embolization of the fistula with absorbable material. If this fails, surgical exploration with ligation of the vessels leading to the fistula is indicated.

Prevalence in sickle cell trait vs sickle cell disease

Ischemic priapism is uncommon in men with sickle cell trait, but prevalence rates in men with sickle cell disease are as high as 42%.28 In a study of 130 men with sickle cell disease, 35% had a history of prolonged ischemic priapism, 72% had a history of stuttering priapism, and 75% of men with stuttering priapism had their first episode before age 20.29

Rates of erectile dysfunction increase with the duration of ischemic episodes and range from 20% to 90%.28,30 In childhood, sickle cell disease accounts for 63% of the cases of ischemic priapism, and in adults it accounts for 23% of cases.31

Take-home messages

- Sickle cell disease accounts for two-thirds of cases of ischemic priapism in children, and one-fourth of adult cases.

- Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency.

- Treatment with aspiration and phenylephrine injections should begin immediately and should not await treatment measures for sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions).

OTHER UROLOGIC COMPLICATIONS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Other urologic complications of sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease include microscopic hematuria, gross hematuria, and renal colic. A formal evaluation of any patient with persistent microscopic hematuria or gross hematuria should consist of urinalysis, computed tomography, and cystoscopy. This approach assesses the upper and lower genitourinary system for treatable causes. Renal ultrasonography can be used instead of computed tomography but tends to provide less information.

Special considerations

In patients with sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease, chronic hypoxia and subsequent sickling of erythrocytes in the renal medulla can lead to papillary hypertrophy and papillary necrosis. In papillary hypertrophy, friable blood vessels can rupture, resulting in microscopic and gross hematuria. In papillary necrosis, the papilla can slough off and become lodged in the ureter.

Nevertheless, hematuria and renal colic in patients with sickle cell disease or trait are most often attributable to common causes such as infection and stones. A finding of hydronephrosis in the absence of a stone, however, suggests obstruction due to a clot or a sloughed papilla. Ureteroscopy, fulguration, and ureteral stent placement can stop the bleeding and alleviate obstruction in these cases.

Renal medullary carcinoma

Another important reason to order imaging in patients with sickle cell disease or trait who present with urologic symptoms is to rule out renal medullary carcinoma, a rare but aggressive cancer that arises from the collecting duct epithelium. This cancer is twice as likely to occur in males than in females; it has been reported in patients ranging in age from 10 to 40, with a median age at presentation of 26.32

When patients present with symptomatic renal medullary cancer, in most cases the cancer has already metastasized.

On computed tomography, the tumor tends to occupy a central location in the kidney and appears to infiltrate and replace adjacent kidney tissue. Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and metastasis are common.

Treatment typically entails radical nephrectomy, chemotherapy, and in some circumstances, radiotherapy. Case reports have shown promising tumor responses to carboplatin and paclitaxel regimens.33,34 Also, a low threshold for imaging in patients with sickle cell disease and trait may increase the odds of early detection of this aggressive cancer.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sickle cell disease (SCD). Data and statistics. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- Paulin L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science 1949; 110:543–548.

- Powars DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005; 84:363–376.

- Haymann JP, Stankovic K, Levy P, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in adult sickle cell anemia: a frequent hemolysis associated feature. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:756–761.

- da Silva GB Jr, Libório AB, Daher Ede F. New insights on pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Hematol 2011; 90:1371–1379.

- Emokpae MA, Uadia PO, Gadzama AA. Correlation of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers with the severity of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Afr Med 2010; 9:141–146.

- Chirico EN, Pialoux V. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. IUBMB Life 2012; 64:72–80.

- Datta V, Ayengar JR, Karpate S, Chaturvedi P. Microalbuminuria as a predictor of early glomerular injury in children with sickle cell disease. Indian J Pediatr 2003; 70:307–309.

- Falk RJ, Scheinman J, Phillips G, Orringer E, Johnson A, Jennette JC. Prevalence and pathologic features of sickle cell nephropathy and response to inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:910–915.

- Maigne G, Ferlicot S, Galacteros F, et al. Glomerular lesions in patients with sickle cell disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010; 89:18–27.

- Sharpe CC, Thein SL. Sickle cell nephropathy—a practical approach. Br J Haematol 2011; 155:287–297.

- Batlle D, Itsarayoungyuen K, Arruda JA, Kurtzman NA. Hyperkalemic hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis in sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Am J Med 1982; 72:188–192.

- Sklar AH, Perez JC, Harp RJ, Caruana RJ. Acute renal failure in sickle cell anemia. Int J Artif Organs 1990; 13:347–351.

- Powars DR, Elliott-Mills DD, Chan L, et al. Chronic renal failure in sickle cell disease: risk factors, clinical course, and mortality. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:614–620.

- McClellan AC, Luthi JC, Lynch JR, et al. High one year mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and end-stage renal disease. Br J Haematol 2012; 159:360–367.

- Bodas P, Huang A, O Riordan MA, Sedor JR, Dell KM. The prevalence of hypertension and abnormal kidney function in children with sickle cell disease—a cross sectional review. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:237.

- Asnani MR, Lynch O, Reid ME. Determining glomerular filtration rate in homozygous sickle cell disease: utility of serum creatinine based estimating equations. PLoS One 2013; 8:e69922.

- Arlet JB, Ribeil JA, Chatellier G, et al. Determination of the best method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine in adult patients with sickle cell disease: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13:83.

- McKie KT, Hanevold CD, Hernandez C, Waller JL, Ortiz L, McKie KM. Prevalence, prevention, and treatment of microalbuminuria and proteinuria in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2007; 29:140–144.

- Laurin LP, Nachman PH, Desai PC, Ataga KI, Derebail VK. Hydroxyurea is associated with lower prevalence of albuminuria in adults with sickle cell disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29:1211–1218.

- Aygun B, Mortier NA, Smeltzer MP, Shulkin BL, Hankins JS, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea treatment decreases glomerular hyperfiltration in children with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 2013; 88:116–119.

- Huang E, Parke C, Mehrnia A, et al. Improved survival among sickle cell kidney transplant recipients in the recent era. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28:1039–1046.

- Klein EA, Montague DK, Steiger E. Priapism associated with the use of intravenous fat emulsion: case reports and postulated pathogenesis. J Urol May 1985; 133:857–859.

- Thuret I, Bardakdjian J, Badens C, et al. Priapism following splenectomy in an unstable hemoglobin: hemoglobin Olmsted beta 141 (H19) Leu-->Arg. Am J Hematol 1996; 51:133–136.

- Montague DK, Angermeier KW. Corporeal excavation: new technique for penile prosthesis implantation in men with severe corporeal fibrosis. Urology 2006; 67:1072–1075.

- Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian J Androl 2012; 14:156–163.

- Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al; Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel; American Urological Association. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol 2003; 170:1318–1324.

- Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140:1434–1437.

- Adeyoju AB, Olujohungbe AB, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications—an international multicentre study. BJU Int 2002; 90:898–902.

- Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med 2004; 1:116–120.

- Nelson JH, 3rd, Winter CC. Priapism: evolution of management in 48 patients in a 22-year series. J Urol 1977; 117:455–458.

- Liu Q, Galli S, Srinivasan R, Linehan WM, Tsokos M, Merino MJ. Renal medullary carcinoma: molecular, immunohistochemistry, and morphologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37:368–374.

- Gangireddy VG, Liles GB, Sostre GD, Coleman T. Response of metastatic renal medullary carcinoma to carboplatinum and Paclitaxel chemotherapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2012; 10:134–139.

- Walsh AM, Fiveash JB, Reddy AT, Friedman GK. Response to radiation in renal medullary carcinoma. Rare Tumors 2011; 3:e32.

Sickle cell disease is a common genetic disorder in the United States that disproportionately affects people of African ancestry. The characteristic sickling of red blood cells under conditions of reduced oxygen tension leads to intravascular hemolysis and vaso-occlusive events, which in turn cause tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury affecting multiple organs, including the genitourinary system.1–3

In this paper, we review the genitourinary effects of sickle cell disease, focusing on sickle cell nephropathy, priapism, and renal medullary carcinoma.

THE WIDE-RANGING EFFECTS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

In the United States, sickle cell disease affects 1 of every 500 blacks and 1 of every 36,000 Hispanics.1 The term describes hemoglobinopathies associated with sickling of red blood cells.

Sickling of red blood cells results from a single base-pair change in the beta-globin gene from glutamic acid to valine at position 6, causing abnormal hemoglobin (hemoglobin S), which polymerizes under conditions of reduced oxygen tension and alters the biconcave disk shape into a rigid, irregular, unstable cell. The sickle-shaped cells are prone to intravascular hemolysis,2 causing intermittent vaso-occlusive events that result in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Genitourinary problems include impaired ability to concentrate urine, hematuria, renal medullary carcinoma, and increased frequency of urinary tract infection.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The kidney is one of the most frequently affected organs in sickle cell disease. Renal manifestations begin to appear in early childhood, with impaired medullary concentrating ability and ischemic damage to the tubular cells caused by sickling within the vasa recta renis precipitated by the acidic, hypoxic, and hypertonic environment in the renal medulla.

As in early diabetic nephropathy, renal blood flow is enhanced and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased. Increased cardiac output as a result of anemia, localized release of prostaglandins, and a hypoxia-induced increase in nitric oxide synthesis all play a role in the increase in GFR.4,5

Oxidative stress, an increase in markers of inflammation, and local activation of the renin-angiotensin system contribute to renal damage in sickle cell disease.5–7 The resulting hyperfiltration injury leads to microalbuminuria, which occurs in 20% to 40% of children with sickle cell anemia8,9 and in as many as 60% of adults.

The glomerular lesions associated with sickle cell disease vary from glomerulopathy in the early stages to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Clinical presentations and workup

Clinical presentations are not limited to glomerular disease but include hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from defects in potassium secretion and renal acidification.

Hyperphosphatemia—a result of increased reabsorption of phosphorus, increased secretion of uric acid, and increased creatinine clearance—is seen in patients with sickle cell disease.11,12 About 10% of patients can develop an acute kidney injury as a result of volume depletion, rhabdomyolysis, renal vein thrombosis, papillary necrosis, and urinary tract obstruction secondary to blood clots.11,13

Up to 30% of adult patients with sickle cell disease develop chronic kidney disease. Predictors include severe anemia, hypertension, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic hematuria.14 From 4% to 12% of patients go on to develop end-stage renal disease, but with a 1-year mortality rate three times higher than in patients without sickle cell disease.15

In general, patients with sickle cell anemia have blood pressures below those of age- and sex-matched individuals, but elevated blood pressure and low GFR are not uncommon in affected children. In a cohort of 48 children ages 3 to 18, 8.3% had an estimated GFR less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 16.7% had elevated blood pressure (prehypertension and hypertension).16

In patients with sickle cell disease, evaluation of proteinuria, hematuria, hypertension, and renal failure should take into consideration the unique renal physiologic and pathologic processes involved. Recent evidence17,18 suggests that the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation provides a better estimate of GFR than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations, although all three creatinine-based methods overestimate GFR in patients with sickle cell disease when compared with GFR measured with technetium-99m-labeled diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renal scanning.

Treatment options

Treatment of sickle cell nephropathy includes adequate fluid intake (given the loss of concentrating ability), adequate blood pressure control, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have microalbuminuria or proteinuria (or both)9,11,19 and hydroxyurea. Treatment with enalapril has been shown to decrease proteinuria in patients with sickle cell nephropathy.9 In a cohort of children with sickle cell disease, four of nine patients treated with an ACE inhibitor developed hyperkalemia, leading to discontinuation of the drug in three patients.9

ACE inhibitors and ARBs must be used cautiously in these patients because they have defects in potassium secretion. Hydroxyurea has also been shown to decrease hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in recent studies,20,21 and this could protect against the development of overt nephropathy.

Higher mortality rates have been reported in patients with sickle cell disease who developed end-stage renal disease than in patients with end-stage renal disease without sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease also increases the risk of pulmonary hypertension and the vaso-occlusive complication known as acute chest syndrome, contributing to increased mortality rates. Of note, in a study that looked at the association between mortality rates and pre-end-stage care of renal disease using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, patients with sickle cell disease who had had predialysis nephrology care had lower mortality rates.15

Treatments for end-stage renal disease are also effective in patients with sickle cell disease and include hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplantation. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing show that from 2000 to 2011, African American kidney recipients with sickle cell disease had better survival rates than patients who had undergone transplantation from 1988 to 1999, although rates of long-term survival and graft survival were lower than in transplant recipients with other diagnoses.22

It is important to note that complications as a result of vaso-occlusive events and thrombosis can lead to graft loss; therefore, sickle cell crisis after transplantation requires careful management.

Take-home messages

- Loss of urine-concentrating ability and hyperfiltration are the earliest pathologic changes in sickle cell disease.

- Microalbuminuria as seen in diabetic nephropathy is the earliest manifestation of sickle cell nephropathy, and the prevalence increases as these patients get older and live longer.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be used with caution, given the heightened risk of hyperkalemia in sickle cell disease.

- Recent results with hydroxyurea in decreasing hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria are encouraging.

- Early referral for predialysis nephrologic care is needed in sickle cell patients with chronic kidney disease.

PRIAPISM IN SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Priapism was formerly defined as a full, painful erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm. But priapism is now recognized as two separate disorders—ischemic (veno-occlusive, low-flow) priapism and nonischemic (arterial, high-flow) priapism. The new definition includes both disorders: ie, a full or partial erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm.

Ischemic priapism

Hematologic disorders are major contributors to ischemic priapism and include sickle cell disease, multiple myeloma, fat emboli (hyperalimentation),23 glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and hemoglobin Olmsted variant.24

Ischemic priapism is often seen in sickle cell disease and is considered an emergency. It is characterized by an abnormally rigid erection not involving the glans penis. Entrapment of blood in the corpora cavernosa leads to hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis, which in turn leads to a painful compartment syndrome that, if untreated, results in smooth muscle necrosis and subsequent fibrosis. The results are a smaller penis and erectile dysfunction that is unresponsive to any treatment other than implantation of a penile prosthesis. However, scarring of the corpora cavernosa can make this procedure exceedingly difficult, requiring advanced techniques such as corporeal excavation.25

Men with a subtype of ischemic priapism called “stuttering” priapism26 suffer recurrent prolonged erections during sleep. The patient awakens with a painful erection that usually subsides, but sometimes only after several hours. Patients with this disorder suffer from sleep deprivation. Stuttering priapism may lead to full-blown ischemic priapism that does not resolve without intervention.

Nonischemic priapism

In nonischemic priapism, the corpora are engorged but not rigid. The condition results from unregulated arterial inflow and thus is not painful and does not result in damage to the corporeal smooth muscle.

Most cases of nonischemic priapism follow blunt perineal trauma or trauma associated with needle insertion into the corpora. This form of priapism is not associated with sickle cell disease. Because tissue damage does not occur, nonischemic or arterial priapism is not considered an emergency.

Treatment guidelines

Differentiating ischemic from nonischemic priapism is usually straightforward, based on the history, physical examination, corporeal blood gases, and duplex ultrasonography.27

Ischemic priapism is an emergency. After needle aspiration of blood from the corpora cavernosa, phenylephrine is diluted with normal saline to a concentration of 100 to 500 µg/mL and is injected in 1-mL amounts repeatedly at 3- to 5-minute intervals until the erection subsides or until a 1-hour time limit is reached. Blood pressure and pulse are monitored during these injections. If aspiration and phenylephrine irrigation fail, surgical shunting is performed.27

Measures to treat sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions) may be employed simultaneously but should never delay aspiration and phenylephrine injections.25

As nonischemic priapism is not considered an emergency, management begins with observation. Patients eventually become dissatisfied with their constant partial erection, and they then present for treatment. Most cases resolve after selective catheterization of the internal pudendal artery and embolization of the fistula with absorbable material. If this fails, surgical exploration with ligation of the vessels leading to the fistula is indicated.

Prevalence in sickle cell trait vs sickle cell disease

Ischemic priapism is uncommon in men with sickle cell trait, but prevalence rates in men with sickle cell disease are as high as 42%.28 In a study of 130 men with sickle cell disease, 35% had a history of prolonged ischemic priapism, 72% had a history of stuttering priapism, and 75% of men with stuttering priapism had their first episode before age 20.29

Rates of erectile dysfunction increase with the duration of ischemic episodes and range from 20% to 90%.28,30 In childhood, sickle cell disease accounts for 63% of the cases of ischemic priapism, and in adults it accounts for 23% of cases.31

Take-home messages

- Sickle cell disease accounts for two-thirds of cases of ischemic priapism in children, and one-fourth of adult cases.

- Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency.

- Treatment with aspiration and phenylephrine injections should begin immediately and should not await treatment measures for sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions).

OTHER UROLOGIC COMPLICATIONS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Other urologic complications of sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease include microscopic hematuria, gross hematuria, and renal colic. A formal evaluation of any patient with persistent microscopic hematuria or gross hematuria should consist of urinalysis, computed tomography, and cystoscopy. This approach assesses the upper and lower genitourinary system for treatable causes. Renal ultrasonography can be used instead of computed tomography but tends to provide less information.

Special considerations

In patients with sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease, chronic hypoxia and subsequent sickling of erythrocytes in the renal medulla can lead to papillary hypertrophy and papillary necrosis. In papillary hypertrophy, friable blood vessels can rupture, resulting in microscopic and gross hematuria. In papillary necrosis, the papilla can slough off and become lodged in the ureter.

Nevertheless, hematuria and renal colic in patients with sickle cell disease or trait are most often attributable to common causes such as infection and stones. A finding of hydronephrosis in the absence of a stone, however, suggests obstruction due to a clot or a sloughed papilla. Ureteroscopy, fulguration, and ureteral stent placement can stop the bleeding and alleviate obstruction in these cases.

Renal medullary carcinoma

Another important reason to order imaging in patients with sickle cell disease or trait who present with urologic symptoms is to rule out renal medullary carcinoma, a rare but aggressive cancer that arises from the collecting duct epithelium. This cancer is twice as likely to occur in males than in females; it has been reported in patients ranging in age from 10 to 40, with a median age at presentation of 26.32

When patients present with symptomatic renal medullary cancer, in most cases the cancer has already metastasized.

On computed tomography, the tumor tends to occupy a central location in the kidney and appears to infiltrate and replace adjacent kidney tissue. Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and metastasis are common.

Treatment typically entails radical nephrectomy, chemotherapy, and in some circumstances, radiotherapy. Case reports have shown promising tumor responses to carboplatin and paclitaxel regimens.33,34 Also, a low threshold for imaging in patients with sickle cell disease and trait may increase the odds of early detection of this aggressive cancer.

Sickle cell disease is a common genetic disorder in the United States that disproportionately affects people of African ancestry. The characteristic sickling of red blood cells under conditions of reduced oxygen tension leads to intravascular hemolysis and vaso-occlusive events, which in turn cause tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury affecting multiple organs, including the genitourinary system.1–3

In this paper, we review the genitourinary effects of sickle cell disease, focusing on sickle cell nephropathy, priapism, and renal medullary carcinoma.

THE WIDE-RANGING EFFECTS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

In the United States, sickle cell disease affects 1 of every 500 blacks and 1 of every 36,000 Hispanics.1 The term describes hemoglobinopathies associated with sickling of red blood cells.

Sickling of red blood cells results from a single base-pair change in the beta-globin gene from glutamic acid to valine at position 6, causing abnormal hemoglobin (hemoglobin S), which polymerizes under conditions of reduced oxygen tension and alters the biconcave disk shape into a rigid, irregular, unstable cell. The sickle-shaped cells are prone to intravascular hemolysis,2 causing intermittent vaso-occlusive events that result in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Genitourinary problems include impaired ability to concentrate urine, hematuria, renal medullary carcinoma, and increased frequency of urinary tract infection.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The kidney is one of the most frequently affected organs in sickle cell disease. Renal manifestations begin to appear in early childhood, with impaired medullary concentrating ability and ischemic damage to the tubular cells caused by sickling within the vasa recta renis precipitated by the acidic, hypoxic, and hypertonic environment in the renal medulla.

As in early diabetic nephropathy, renal blood flow is enhanced and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased. Increased cardiac output as a result of anemia, localized release of prostaglandins, and a hypoxia-induced increase in nitric oxide synthesis all play a role in the increase in GFR.4,5

Oxidative stress, an increase in markers of inflammation, and local activation of the renin-angiotensin system contribute to renal damage in sickle cell disease.5–7 The resulting hyperfiltration injury leads to microalbuminuria, which occurs in 20% to 40% of children with sickle cell anemia8,9 and in as many as 60% of adults.

The glomerular lesions associated with sickle cell disease vary from glomerulopathy in the early stages to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Clinical presentations and workup

Clinical presentations are not limited to glomerular disease but include hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from defects in potassium secretion and renal acidification.

Hyperphosphatemia—a result of increased reabsorption of phosphorus, increased secretion of uric acid, and increased creatinine clearance—is seen in patients with sickle cell disease.11,12 About 10% of patients can develop an acute kidney injury as a result of volume depletion, rhabdomyolysis, renal vein thrombosis, papillary necrosis, and urinary tract obstruction secondary to blood clots.11,13

Up to 30% of adult patients with sickle cell disease develop chronic kidney disease. Predictors include severe anemia, hypertension, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic hematuria.14 From 4% to 12% of patients go on to develop end-stage renal disease, but with a 1-year mortality rate three times higher than in patients without sickle cell disease.15

In general, patients with sickle cell anemia have blood pressures below those of age- and sex-matched individuals, but elevated blood pressure and low GFR are not uncommon in affected children. In a cohort of 48 children ages 3 to 18, 8.3% had an estimated GFR less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 16.7% had elevated blood pressure (prehypertension and hypertension).16

In patients with sickle cell disease, evaluation of proteinuria, hematuria, hypertension, and renal failure should take into consideration the unique renal physiologic and pathologic processes involved. Recent evidence17,18 suggests that the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation provides a better estimate of GFR than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations, although all three creatinine-based methods overestimate GFR in patients with sickle cell disease when compared with GFR measured with technetium-99m-labeled diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renal scanning.

Treatment options

Treatment of sickle cell nephropathy includes adequate fluid intake (given the loss of concentrating ability), adequate blood pressure control, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have microalbuminuria or proteinuria (or both)9,11,19 and hydroxyurea. Treatment with enalapril has been shown to decrease proteinuria in patients with sickle cell nephropathy.9 In a cohort of children with sickle cell disease, four of nine patients treated with an ACE inhibitor developed hyperkalemia, leading to discontinuation of the drug in three patients.9

ACE inhibitors and ARBs must be used cautiously in these patients because they have defects in potassium secretion. Hydroxyurea has also been shown to decrease hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in recent studies,20,21 and this could protect against the development of overt nephropathy.

Higher mortality rates have been reported in patients with sickle cell disease who developed end-stage renal disease than in patients with end-stage renal disease without sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease also increases the risk of pulmonary hypertension and the vaso-occlusive complication known as acute chest syndrome, contributing to increased mortality rates. Of note, in a study that looked at the association between mortality rates and pre-end-stage care of renal disease using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, patients with sickle cell disease who had had predialysis nephrology care had lower mortality rates.15

Treatments for end-stage renal disease are also effective in patients with sickle cell disease and include hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplantation. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing show that from 2000 to 2011, African American kidney recipients with sickle cell disease had better survival rates than patients who had undergone transplantation from 1988 to 1999, although rates of long-term survival and graft survival were lower than in transplant recipients with other diagnoses.22

It is important to note that complications as a result of vaso-occlusive events and thrombosis can lead to graft loss; therefore, sickle cell crisis after transplantation requires careful management.

Take-home messages

- Loss of urine-concentrating ability and hyperfiltration are the earliest pathologic changes in sickle cell disease.

- Microalbuminuria as seen in diabetic nephropathy is the earliest manifestation of sickle cell nephropathy, and the prevalence increases as these patients get older and live longer.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be used with caution, given the heightened risk of hyperkalemia in sickle cell disease.

- Recent results with hydroxyurea in decreasing hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria are encouraging.

- Early referral for predialysis nephrologic care is needed in sickle cell patients with chronic kidney disease.

PRIAPISM IN SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Priapism was formerly defined as a full, painful erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm. But priapism is now recognized as two separate disorders—ischemic (veno-occlusive, low-flow) priapism and nonischemic (arterial, high-flow) priapism. The new definition includes both disorders: ie, a full or partial erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm.

Ischemic priapism

Hematologic disorders are major contributors to ischemic priapism and include sickle cell disease, multiple myeloma, fat emboli (hyperalimentation),23 glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and hemoglobin Olmsted variant.24

Ischemic priapism is often seen in sickle cell disease and is considered an emergency. It is characterized by an abnormally rigid erection not involving the glans penis. Entrapment of blood in the corpora cavernosa leads to hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis, which in turn leads to a painful compartment syndrome that, if untreated, results in smooth muscle necrosis and subsequent fibrosis. The results are a smaller penis and erectile dysfunction that is unresponsive to any treatment other than implantation of a penile prosthesis. However, scarring of the corpora cavernosa can make this procedure exceedingly difficult, requiring advanced techniques such as corporeal excavation.25

Men with a subtype of ischemic priapism called “stuttering” priapism26 suffer recurrent prolonged erections during sleep. The patient awakens with a painful erection that usually subsides, but sometimes only after several hours. Patients with this disorder suffer from sleep deprivation. Stuttering priapism may lead to full-blown ischemic priapism that does not resolve without intervention.

Nonischemic priapism

In nonischemic priapism, the corpora are engorged but not rigid. The condition results from unregulated arterial inflow and thus is not painful and does not result in damage to the corporeal smooth muscle.

Most cases of nonischemic priapism follow blunt perineal trauma or trauma associated with needle insertion into the corpora. This form of priapism is not associated with sickle cell disease. Because tissue damage does not occur, nonischemic or arterial priapism is not considered an emergency.

Treatment guidelines

Differentiating ischemic from nonischemic priapism is usually straightforward, based on the history, physical examination, corporeal blood gases, and duplex ultrasonography.27

Ischemic priapism is an emergency. After needle aspiration of blood from the corpora cavernosa, phenylephrine is diluted with normal saline to a concentration of 100 to 500 µg/mL and is injected in 1-mL amounts repeatedly at 3- to 5-minute intervals until the erection subsides or until a 1-hour time limit is reached. Blood pressure and pulse are monitored during these injections. If aspiration and phenylephrine irrigation fail, surgical shunting is performed.27

Measures to treat sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions) may be employed simultaneously but should never delay aspiration and phenylephrine injections.25

As nonischemic priapism is not considered an emergency, management begins with observation. Patients eventually become dissatisfied with their constant partial erection, and they then present for treatment. Most cases resolve after selective catheterization of the internal pudendal artery and embolization of the fistula with absorbable material. If this fails, surgical exploration with ligation of the vessels leading to the fistula is indicated.

Prevalence in sickle cell trait vs sickle cell disease

Ischemic priapism is uncommon in men with sickle cell trait, but prevalence rates in men with sickle cell disease are as high as 42%.28 In a study of 130 men with sickle cell disease, 35% had a history of prolonged ischemic priapism, 72% had a history of stuttering priapism, and 75% of men with stuttering priapism had their first episode before age 20.29

Rates of erectile dysfunction increase with the duration of ischemic episodes and range from 20% to 90%.28,30 In childhood, sickle cell disease accounts for 63% of the cases of ischemic priapism, and in adults it accounts for 23% of cases.31

Take-home messages

- Sickle cell disease accounts for two-thirds of cases of ischemic priapism in children, and one-fourth of adult cases.

- Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency.

- Treatment with aspiration and phenylephrine injections should begin immediately and should not await treatment measures for sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions).

OTHER UROLOGIC COMPLICATIONS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Other urologic complications of sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease include microscopic hematuria, gross hematuria, and renal colic. A formal evaluation of any patient with persistent microscopic hematuria or gross hematuria should consist of urinalysis, computed tomography, and cystoscopy. This approach assesses the upper and lower genitourinary system for treatable causes. Renal ultrasonography can be used instead of computed tomography but tends to provide less information.

Special considerations

In patients with sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease, chronic hypoxia and subsequent sickling of erythrocytes in the renal medulla can lead to papillary hypertrophy and papillary necrosis. In papillary hypertrophy, friable blood vessels can rupture, resulting in microscopic and gross hematuria. In papillary necrosis, the papilla can slough off and become lodged in the ureter.

Nevertheless, hematuria and renal colic in patients with sickle cell disease or trait are most often attributable to common causes such as infection and stones. A finding of hydronephrosis in the absence of a stone, however, suggests obstruction due to a clot or a sloughed papilla. Ureteroscopy, fulguration, and ureteral stent placement can stop the bleeding and alleviate obstruction in these cases.

Renal medullary carcinoma

Another important reason to order imaging in patients with sickle cell disease or trait who present with urologic symptoms is to rule out renal medullary carcinoma, a rare but aggressive cancer that arises from the collecting duct epithelium. This cancer is twice as likely to occur in males than in females; it has been reported in patients ranging in age from 10 to 40, with a median age at presentation of 26.32

When patients present with symptomatic renal medullary cancer, in most cases the cancer has already metastasized.

On computed tomography, the tumor tends to occupy a central location in the kidney and appears to infiltrate and replace adjacent kidney tissue. Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and metastasis are common.

Treatment typically entails radical nephrectomy, chemotherapy, and in some circumstances, radiotherapy. Case reports have shown promising tumor responses to carboplatin and paclitaxel regimens.33,34 Also, a low threshold for imaging in patients with sickle cell disease and trait may increase the odds of early detection of this aggressive cancer.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sickle cell disease (SCD). Data and statistics. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- Paulin L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science 1949; 110:543–548.

- Powars DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005; 84:363–376.

- Haymann JP, Stankovic K, Levy P, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in adult sickle cell anemia: a frequent hemolysis associated feature. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:756–761.

- da Silva GB Jr, Libório AB, Daher Ede F. New insights on pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Hematol 2011; 90:1371–1379.

- Emokpae MA, Uadia PO, Gadzama AA. Correlation of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers with the severity of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Afr Med 2010; 9:141–146.

- Chirico EN, Pialoux V. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. IUBMB Life 2012; 64:72–80.

- Datta V, Ayengar JR, Karpate S, Chaturvedi P. Microalbuminuria as a predictor of early glomerular injury in children with sickle cell disease. Indian J Pediatr 2003; 70:307–309.

- Falk RJ, Scheinman J, Phillips G, Orringer E, Johnson A, Jennette JC. Prevalence and pathologic features of sickle cell nephropathy and response to inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:910–915.

- Maigne G, Ferlicot S, Galacteros F, et al. Glomerular lesions in patients with sickle cell disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010; 89:18–27.

- Sharpe CC, Thein SL. Sickle cell nephropathy—a practical approach. Br J Haematol 2011; 155:287–297.

- Batlle D, Itsarayoungyuen K, Arruda JA, Kurtzman NA. Hyperkalemic hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis in sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Am J Med 1982; 72:188–192.

- Sklar AH, Perez JC, Harp RJ, Caruana RJ. Acute renal failure in sickle cell anemia. Int J Artif Organs 1990; 13:347–351.

- Powars DR, Elliott-Mills DD, Chan L, et al. Chronic renal failure in sickle cell disease: risk factors, clinical course, and mortality. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:614–620.

- McClellan AC, Luthi JC, Lynch JR, et al. High one year mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and end-stage renal disease. Br J Haematol 2012; 159:360–367.

- Bodas P, Huang A, O Riordan MA, Sedor JR, Dell KM. The prevalence of hypertension and abnormal kidney function in children with sickle cell disease—a cross sectional review. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:237.

- Asnani MR, Lynch O, Reid ME. Determining glomerular filtration rate in homozygous sickle cell disease: utility of serum creatinine based estimating equations. PLoS One 2013; 8:e69922.

- Arlet JB, Ribeil JA, Chatellier G, et al. Determination of the best method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine in adult patients with sickle cell disease: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13:83.

- McKie KT, Hanevold CD, Hernandez C, Waller JL, Ortiz L, McKie KM. Prevalence, prevention, and treatment of microalbuminuria and proteinuria in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2007; 29:140–144.

- Laurin LP, Nachman PH, Desai PC, Ataga KI, Derebail VK. Hydroxyurea is associated with lower prevalence of albuminuria in adults with sickle cell disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29:1211–1218.

- Aygun B, Mortier NA, Smeltzer MP, Shulkin BL, Hankins JS, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea treatment decreases glomerular hyperfiltration in children with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 2013; 88:116–119.

- Huang E, Parke C, Mehrnia A, et al. Improved survival among sickle cell kidney transplant recipients in the recent era. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28:1039–1046.

- Klein EA, Montague DK, Steiger E. Priapism associated with the use of intravenous fat emulsion: case reports and postulated pathogenesis. J Urol May 1985; 133:857–859.

- Thuret I, Bardakdjian J, Badens C, et al. Priapism following splenectomy in an unstable hemoglobin: hemoglobin Olmsted beta 141 (H19) Leu-->Arg. Am J Hematol 1996; 51:133–136.

- Montague DK, Angermeier KW. Corporeal excavation: new technique for penile prosthesis implantation in men with severe corporeal fibrosis. Urology 2006; 67:1072–1075.

- Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian J Androl 2012; 14:156–163.

- Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al; Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel; American Urological Association. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol 2003; 170:1318–1324.

- Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140:1434–1437.

- Adeyoju AB, Olujohungbe AB, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications—an international multicentre study. BJU Int 2002; 90:898–902.

- Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med 2004; 1:116–120.

- Nelson JH, 3rd, Winter CC. Priapism: evolution of management in 48 patients in a 22-year series. J Urol 1977; 117:455–458.

- Liu Q, Galli S, Srinivasan R, Linehan WM, Tsokos M, Merino MJ. Renal medullary carcinoma: molecular, immunohistochemistry, and morphologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37:368–374.

- Gangireddy VG, Liles GB, Sostre GD, Coleman T. Response of metastatic renal medullary carcinoma to carboplatinum and Paclitaxel chemotherapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2012; 10:134–139.

- Walsh AM, Fiveash JB, Reddy AT, Friedman GK. Response to radiation in renal medullary carcinoma. Rare Tumors 2011; 3:e32.