User login

Trends in the management of pulmonary embolism

One of the newest trends in pulmonary embolism management is treatment of cancer associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) which encompasses deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. Following the clinical management of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the hospital, direct oral anticoagulant therapy at discharge is your starting point, except in cases of intact luminal cancers, Scott Kaatz, DO, MSc, FACP, SFHM, said during SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Kaatz, of the division of hospital medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, based his remarks on emerging recommendations from leading medical societies on the topic, as well as a one-page algorithm from the Anticoagulation Forum that can be accessed at https://acforum-excellence.org/Resource-Center/resource_files/1638-2020-11-30-121425.pdf.

For the short-term treatment of VTE (3-6 months) for patients with active cancer, the American Society of Hematology guideline panel suggests direct oral anticoagulants, such as apixaban, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban, over low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) – a conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence of effects.

Dr. Kaatz also discussed the latest recommendations regarding length of VTE treatment. After completion of primary treatment for patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a chronic risk factor such as a surgery, pregnancy, or having a leg in a cast, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “On the other hand, patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a transient factor typically do not require antithrombotic therapy after completion of primary treatment,” said Dr. Kaatz, who is also a clinical professor of medicine at Wayne State University, Detroit.

After completion of primary treatment for patients with unprovoked DVT and/or PE, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “The recommendation does not apply to patients who have a high risk for bleeding complications,” he noted.

Transient or reversible risk factors should be also considered in length of VTE treatment. For example, according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology, the estimated risk for long-term VTE recurrence is high (defined as greater than 8% per year) for patients with active cancer, for patients with one or more previous episodes of VTE in the absence of a major transient or reversible factor, and for those with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Dr. Kaatz also highlighted recommendations for the acute treatment of intermediate risk, or submassive PE. The ESC guidelines state that if anticoagulation is initiated parenterally, LMWH or fondaparinux is recommended over unfractionated heparin (UFH) for most patients. “The reason for that is, one drug-use evaluation study found that, after 24 hours using UFH, only about 24% of patients had reached their therapeutic goal,” Dr. Kaatz said. Guidelines for intermediate risk patients from ASH recommend anticoagulation as your starting point, while thrombolysis is reasonable to consider for submassive PE and low risk for bleeding in selected younger patients or for patients at high risk for decompensation because of concomitant cardiopulmonary disease. “The bleeding rates get much higher in patients over age 65,” he said.

Another resource Dr. Kaatz mentioned is the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) Consortium, which was developed after initial efforts of a multidisciplinary team of physicians at Massachusetts General Hospital. The first PERT sought to coordinate and expedite the treatment of pulmonary embolus with a team of physicians from a variety of specialties. In 2019 the PERT Consortium published guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE. “It includes detailed algorithms that are a little different from the ASH and ESC guidelines,” Dr. Kaatz said.

Dr. Kaatz disclosed that he is a consultant for Janssen, Pfizer, Portola/Alexion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and CSL Behring. He has also received research funding from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Osmosis. He also holds board positions with the AC Forum and the National Blood Clot Alliance Medical and Scientific Advisory Board.

One of the newest trends in pulmonary embolism management is treatment of cancer associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) which encompasses deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. Following the clinical management of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the hospital, direct oral anticoagulant therapy at discharge is your starting point, except in cases of intact luminal cancers, Scott Kaatz, DO, MSc, FACP, SFHM, said during SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Kaatz, of the division of hospital medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, based his remarks on emerging recommendations from leading medical societies on the topic, as well as a one-page algorithm from the Anticoagulation Forum that can be accessed at https://acforum-excellence.org/Resource-Center/resource_files/1638-2020-11-30-121425.pdf.

For the short-term treatment of VTE (3-6 months) for patients with active cancer, the American Society of Hematology guideline panel suggests direct oral anticoagulants, such as apixaban, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban, over low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) – a conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence of effects.

Dr. Kaatz also discussed the latest recommendations regarding length of VTE treatment. After completion of primary treatment for patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a chronic risk factor such as a surgery, pregnancy, or having a leg in a cast, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “On the other hand, patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a transient factor typically do not require antithrombotic therapy after completion of primary treatment,” said Dr. Kaatz, who is also a clinical professor of medicine at Wayne State University, Detroit.

After completion of primary treatment for patients with unprovoked DVT and/or PE, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “The recommendation does not apply to patients who have a high risk for bleeding complications,” he noted.

Transient or reversible risk factors should be also considered in length of VTE treatment. For example, according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology, the estimated risk for long-term VTE recurrence is high (defined as greater than 8% per year) for patients with active cancer, for patients with one or more previous episodes of VTE in the absence of a major transient or reversible factor, and for those with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Dr. Kaatz also highlighted recommendations for the acute treatment of intermediate risk, or submassive PE. The ESC guidelines state that if anticoagulation is initiated parenterally, LMWH or fondaparinux is recommended over unfractionated heparin (UFH) for most patients. “The reason for that is, one drug-use evaluation study found that, after 24 hours using UFH, only about 24% of patients had reached their therapeutic goal,” Dr. Kaatz said. Guidelines for intermediate risk patients from ASH recommend anticoagulation as your starting point, while thrombolysis is reasonable to consider for submassive PE and low risk for bleeding in selected younger patients or for patients at high risk for decompensation because of concomitant cardiopulmonary disease. “The bleeding rates get much higher in patients over age 65,” he said.

Another resource Dr. Kaatz mentioned is the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) Consortium, which was developed after initial efforts of a multidisciplinary team of physicians at Massachusetts General Hospital. The first PERT sought to coordinate and expedite the treatment of pulmonary embolus with a team of physicians from a variety of specialties. In 2019 the PERT Consortium published guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE. “It includes detailed algorithms that are a little different from the ASH and ESC guidelines,” Dr. Kaatz said.

Dr. Kaatz disclosed that he is a consultant for Janssen, Pfizer, Portola/Alexion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and CSL Behring. He has also received research funding from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Osmosis. He also holds board positions with the AC Forum and the National Blood Clot Alliance Medical and Scientific Advisory Board.

One of the newest trends in pulmonary embolism management is treatment of cancer associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) which encompasses deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. Following the clinical management of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the hospital, direct oral anticoagulant therapy at discharge is your starting point, except in cases of intact luminal cancers, Scott Kaatz, DO, MSc, FACP, SFHM, said during SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Kaatz, of the division of hospital medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, based his remarks on emerging recommendations from leading medical societies on the topic, as well as a one-page algorithm from the Anticoagulation Forum that can be accessed at https://acforum-excellence.org/Resource-Center/resource_files/1638-2020-11-30-121425.pdf.

For the short-term treatment of VTE (3-6 months) for patients with active cancer, the American Society of Hematology guideline panel suggests direct oral anticoagulants, such as apixaban, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban, over low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) – a conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence of effects.

Dr. Kaatz also discussed the latest recommendations regarding length of VTE treatment. After completion of primary treatment for patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a chronic risk factor such as a surgery, pregnancy, or having a leg in a cast, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “On the other hand, patients with DVT and/or PE provoked by a transient factor typically do not require antithrombotic therapy after completion of primary treatment,” said Dr. Kaatz, who is also a clinical professor of medicine at Wayne State University, Detroit.

After completion of primary treatment for patients with unprovoked DVT and/or PE, the ASH guideline panel suggests indefinite antithrombotic therapy over stopping anticoagulation. “The recommendation does not apply to patients who have a high risk for bleeding complications,” he noted.

Transient or reversible risk factors should be also considered in length of VTE treatment. For example, according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology, the estimated risk for long-term VTE recurrence is high (defined as greater than 8% per year) for patients with active cancer, for patients with one or more previous episodes of VTE in the absence of a major transient or reversible factor, and for those with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Dr. Kaatz also highlighted recommendations for the acute treatment of intermediate risk, or submassive PE. The ESC guidelines state that if anticoagulation is initiated parenterally, LMWH or fondaparinux is recommended over unfractionated heparin (UFH) for most patients. “The reason for that is, one drug-use evaluation study found that, after 24 hours using UFH, only about 24% of patients had reached their therapeutic goal,” Dr. Kaatz said. Guidelines for intermediate risk patients from ASH recommend anticoagulation as your starting point, while thrombolysis is reasonable to consider for submassive PE and low risk for bleeding in selected younger patients or for patients at high risk for decompensation because of concomitant cardiopulmonary disease. “The bleeding rates get much higher in patients over age 65,” he said.

Another resource Dr. Kaatz mentioned is the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) Consortium, which was developed after initial efforts of a multidisciplinary team of physicians at Massachusetts General Hospital. The first PERT sought to coordinate and expedite the treatment of pulmonary embolus with a team of physicians from a variety of specialties. In 2019 the PERT Consortium published guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE. “It includes detailed algorithms that are a little different from the ASH and ESC guidelines,” Dr. Kaatz said.

Dr. Kaatz disclosed that he is a consultant for Janssen, Pfizer, Portola/Alexion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and CSL Behring. He has also received research funding from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Osmosis. He also holds board positions with the AC Forum and the National Blood Clot Alliance Medical and Scientific Advisory Board.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Expert emphasizes importance of screening for OSA prior to surgery

If you don’t have a standardized process for obstructive sleep apnea screening of all patients heading into the operating room at your hospital you should, because perioperative pulmonary complications can occur, according to Efren C. Manjarrez MD, SFHM, FACP.

If OSA is not documented in the patient’s chart, you may find yourself making a bedside assessment. “I usually don’t ask the patients this because they can’t necessarily answer the questions,” Dr. Manjarrez, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, said at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “So, I ask their partner: ‘Does your partner snore loudly? Are they sleepy during the daytime, or are they gasping or choking in the middle of the night?’”

The following factors have a relatively high specificity for OSA: a STOP-Bang score of 5 or greater, a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus male gender, and a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2. Clinicians can also check the Mallampati score on their patients by having them tilt their heads back and stick out their tongues.

“If the uvula is not touching the tongue, that’s a Mallampati score of 1; that’s a pretty wide-open airway,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “However, when you do not have any form of an airway and the palate is touching the tongue, that is a Mallampati score of 4, which indicates OSA.”

Other objective data suggestive of OSA include high blood pressure, a BMI over 35 kg/m2, a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, and male gender. In a study of patients who presented for surgery who did not have a diagnosis of sleep apnea, a high STOP-Bang score indicated a high probability of moderate to severe sleep apnea (Br J. Anaesth 2012;108[5]:768-75).

“If the STOP-Bang score is 0-2, your workup stops,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If your STOP-Bang score is 5 or above, there’s a high likelihood they have moderate or severe sleep apnea. Patients who have a STOP-Bang of 3-4, calculate their STOP score. If the STOP score is 2 or more and they’re male, obese, and have a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, there’s a pretty good chance they’ve got OSA.”

Screening for OSA prior to surgery matters, because the potential pulmonary complications are fairly high, “anywhere from postoperative respiratory failure to COPD exacerbation and hypoxia to pneumonia,” he continued. “These patients very commonly desaturate and are difficult for the anesthesiologists to intubate. Fortunately, we have not found significant cardiac complications in the medical literature, but we do know that patients with OSA commonly get postoperative atrial fibrillation. There are also combined complications like desaturation and AFib and difficult intubations. Patients with sleep apnea do have a higher resource utilization perioperatively. Fortunately, at this point in time the data does not show that patients with OSA going in for surgery have an increased mortality.”

To optimize the care of these patients prior to surgery, Dr. Manjarrez recommends that hospitalists document that a patient either has known OSA or suspected OSA. “If possible, obtain their sleep study results and recommended PAP settings,” he said. “Ask patients to bring their PAP device to the hospital or to assure the hospital has appropriate surrogate devices available. You also want to advise the patient and the perioperative care team of the increased risk of complications in patients at high risk for OSA and optimize other conditions that may impair cardiorespiratory function.”

Perioperative risk reduction strategies include planning for difficult intubation and mask ventilation, using regional anesthesia and analgesia, using sedatives with caution, minimizing the use of opioids and anticipating variable opioid responses. “When I have a patient with suspected sleep apnea and no red flags I write down ‘OSA precautions,’ in the chart, which means elevate the head of the bed, perform continuous pulse oximetry, and cautiously supply supplemental oxygen as needed,” he said.

Postoperatively, he continued, minimize sedative agents and opioids, use regional and nonopioid analgesics when possible, provide supplemental oxygen until the patient is able to maintain baseline SaO2 on room air in a monitored setting, maintain the patient in nonsupine position when feasible, and continuously monitor pulse oximetry.

Consider delay of elective surgery and referral to a sleep medicine specialist in cases of uncontrolled systemic conditions or impaired gas exchange, including hypoventilation syndromes (a clue being a serum HC03 of 28 or higher), severe pulmonary hypertension (a clue being right ventricular systolic blood pressure or pulmonary systolic pressure of 70 mm Hg or above, or right ventricular dilatation/dysfunction), and hypoxemia not explained by cardiac disease.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of six studies that included 904 patients with sleep apnea found that there was no significant difference in the postoperative adverse events between CPAP and no-CPAP treatment (Anesth Analg 2015;120:1013-23). However, there was a significant reduction in the Apnea-Hypopnea Index postoperatively among those who used CPAP (37 vs. 12 events per hour; P less than .001), as well as a significant reduction in hospital length of stay 4 vs. 4.4 days; P = .05).

Dr. Manjarrez reported having no financial disclosures.

If you don’t have a standardized process for obstructive sleep apnea screening of all patients heading into the operating room at your hospital you should, because perioperative pulmonary complications can occur, according to Efren C. Manjarrez MD, SFHM, FACP.

If OSA is not documented in the patient’s chart, you may find yourself making a bedside assessment. “I usually don’t ask the patients this because they can’t necessarily answer the questions,” Dr. Manjarrez, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, said at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “So, I ask their partner: ‘Does your partner snore loudly? Are they sleepy during the daytime, or are they gasping or choking in the middle of the night?’”

The following factors have a relatively high specificity for OSA: a STOP-Bang score of 5 or greater, a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus male gender, and a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2. Clinicians can also check the Mallampati score on their patients by having them tilt their heads back and stick out their tongues.

“If the uvula is not touching the tongue, that’s a Mallampati score of 1; that’s a pretty wide-open airway,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “However, when you do not have any form of an airway and the palate is touching the tongue, that is a Mallampati score of 4, which indicates OSA.”

Other objective data suggestive of OSA include high blood pressure, a BMI over 35 kg/m2, a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, and male gender. In a study of patients who presented for surgery who did not have a diagnosis of sleep apnea, a high STOP-Bang score indicated a high probability of moderate to severe sleep apnea (Br J. Anaesth 2012;108[5]:768-75).

“If the STOP-Bang score is 0-2, your workup stops,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If your STOP-Bang score is 5 or above, there’s a high likelihood they have moderate or severe sleep apnea. Patients who have a STOP-Bang of 3-4, calculate their STOP score. If the STOP score is 2 or more and they’re male, obese, and have a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, there’s a pretty good chance they’ve got OSA.”

Screening for OSA prior to surgery matters, because the potential pulmonary complications are fairly high, “anywhere from postoperative respiratory failure to COPD exacerbation and hypoxia to pneumonia,” he continued. “These patients very commonly desaturate and are difficult for the anesthesiologists to intubate. Fortunately, we have not found significant cardiac complications in the medical literature, but we do know that patients with OSA commonly get postoperative atrial fibrillation. There are also combined complications like desaturation and AFib and difficult intubations. Patients with sleep apnea do have a higher resource utilization perioperatively. Fortunately, at this point in time the data does not show that patients with OSA going in for surgery have an increased mortality.”

To optimize the care of these patients prior to surgery, Dr. Manjarrez recommends that hospitalists document that a patient either has known OSA or suspected OSA. “If possible, obtain their sleep study results and recommended PAP settings,” he said. “Ask patients to bring their PAP device to the hospital or to assure the hospital has appropriate surrogate devices available. You also want to advise the patient and the perioperative care team of the increased risk of complications in patients at high risk for OSA and optimize other conditions that may impair cardiorespiratory function.”

Perioperative risk reduction strategies include planning for difficult intubation and mask ventilation, using regional anesthesia and analgesia, using sedatives with caution, minimizing the use of opioids and anticipating variable opioid responses. “When I have a patient with suspected sleep apnea and no red flags I write down ‘OSA precautions,’ in the chart, which means elevate the head of the bed, perform continuous pulse oximetry, and cautiously supply supplemental oxygen as needed,” he said.

Postoperatively, he continued, minimize sedative agents and opioids, use regional and nonopioid analgesics when possible, provide supplemental oxygen until the patient is able to maintain baseline SaO2 on room air in a monitored setting, maintain the patient in nonsupine position when feasible, and continuously monitor pulse oximetry.

Consider delay of elective surgery and referral to a sleep medicine specialist in cases of uncontrolled systemic conditions or impaired gas exchange, including hypoventilation syndromes (a clue being a serum HC03 of 28 or higher), severe pulmonary hypertension (a clue being right ventricular systolic blood pressure or pulmonary systolic pressure of 70 mm Hg or above, or right ventricular dilatation/dysfunction), and hypoxemia not explained by cardiac disease.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of six studies that included 904 patients with sleep apnea found that there was no significant difference in the postoperative adverse events between CPAP and no-CPAP treatment (Anesth Analg 2015;120:1013-23). However, there was a significant reduction in the Apnea-Hypopnea Index postoperatively among those who used CPAP (37 vs. 12 events per hour; P less than .001), as well as a significant reduction in hospital length of stay 4 vs. 4.4 days; P = .05).

Dr. Manjarrez reported having no financial disclosures.

If you don’t have a standardized process for obstructive sleep apnea screening of all patients heading into the operating room at your hospital you should, because perioperative pulmonary complications can occur, according to Efren C. Manjarrez MD, SFHM, FACP.

If OSA is not documented in the patient’s chart, you may find yourself making a bedside assessment. “I usually don’t ask the patients this because they can’t necessarily answer the questions,” Dr. Manjarrez, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, said at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine. “So, I ask their partner: ‘Does your partner snore loudly? Are they sleepy during the daytime, or are they gasping or choking in the middle of the night?’”

The following factors have a relatively high specificity for OSA: a STOP-Bang score of 5 or greater, a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus male gender, and a STOP-Bang score of 2 or greater plus a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2. Clinicians can also check the Mallampati score on their patients by having them tilt their heads back and stick out their tongues.

“If the uvula is not touching the tongue, that’s a Mallampati score of 1; that’s a pretty wide-open airway,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “However, when you do not have any form of an airway and the palate is touching the tongue, that is a Mallampati score of 4, which indicates OSA.”

Other objective data suggestive of OSA include high blood pressure, a BMI over 35 kg/m2, a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, and male gender. In a study of patients who presented for surgery who did not have a diagnosis of sleep apnea, a high STOP-Bang score indicated a high probability of moderate to severe sleep apnea (Br J. Anaesth 2012;108[5]:768-75).

“If the STOP-Bang score is 0-2, your workup stops,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If your STOP-Bang score is 5 or above, there’s a high likelihood they have moderate or severe sleep apnea. Patients who have a STOP-Bang of 3-4, calculate their STOP score. If the STOP score is 2 or more and they’re male, obese, and have a neck circumference of greater than 40 cm, there’s a pretty good chance they’ve got OSA.”

Screening for OSA prior to surgery matters, because the potential pulmonary complications are fairly high, “anywhere from postoperative respiratory failure to COPD exacerbation and hypoxia to pneumonia,” he continued. “These patients very commonly desaturate and are difficult for the anesthesiologists to intubate. Fortunately, we have not found significant cardiac complications in the medical literature, but we do know that patients with OSA commonly get postoperative atrial fibrillation. There are also combined complications like desaturation and AFib and difficult intubations. Patients with sleep apnea do have a higher resource utilization perioperatively. Fortunately, at this point in time the data does not show that patients with OSA going in for surgery have an increased mortality.”

To optimize the care of these patients prior to surgery, Dr. Manjarrez recommends that hospitalists document that a patient either has known OSA or suspected OSA. “If possible, obtain their sleep study results and recommended PAP settings,” he said. “Ask patients to bring their PAP device to the hospital or to assure the hospital has appropriate surrogate devices available. You also want to advise the patient and the perioperative care team of the increased risk of complications in patients at high risk for OSA and optimize other conditions that may impair cardiorespiratory function.”

Perioperative risk reduction strategies include planning for difficult intubation and mask ventilation, using regional anesthesia and analgesia, using sedatives with caution, minimizing the use of opioids and anticipating variable opioid responses. “When I have a patient with suspected sleep apnea and no red flags I write down ‘OSA precautions,’ in the chart, which means elevate the head of the bed, perform continuous pulse oximetry, and cautiously supply supplemental oxygen as needed,” he said.

Postoperatively, he continued, minimize sedative agents and opioids, use regional and nonopioid analgesics when possible, provide supplemental oxygen until the patient is able to maintain baseline SaO2 on room air in a monitored setting, maintain the patient in nonsupine position when feasible, and continuously monitor pulse oximetry.

Consider delay of elective surgery and referral to a sleep medicine specialist in cases of uncontrolled systemic conditions or impaired gas exchange, including hypoventilation syndromes (a clue being a serum HC03 of 28 or higher), severe pulmonary hypertension (a clue being right ventricular systolic blood pressure or pulmonary systolic pressure of 70 mm Hg or above, or right ventricular dilatation/dysfunction), and hypoxemia not explained by cardiac disease.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of six studies that included 904 patients with sleep apnea found that there was no significant difference in the postoperative adverse events between CPAP and no-CPAP treatment (Anesth Analg 2015;120:1013-23). However, there was a significant reduction in the Apnea-Hypopnea Index postoperatively among those who used CPAP (37 vs. 12 events per hour; P less than .001), as well as a significant reduction in hospital length of stay 4 vs. 4.4 days; P = .05).

Dr. Manjarrez reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Evidence or anecdote: Clinical judgment in COVID care

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and evidence evolves, clinical judgment is the bottom line for clinical care, according to Adarsh Bhimraj, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and James Walter, MD, of Northwestern Medicine, Chicago.

In a debate/discussion presented at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter took sides in a friendly debate on the value of remdesivir and tocilizumab for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Dr. Bhimraj argued for the use of remdesivir or tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia, and Dr. Walter presented the case against their use.

Referendum on remdesivir

The main sources referenced by the presenters regarding remdesivir were the WHO Solidarity Trial (N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184) and the Adaptive Covid-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT) final report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764).

“The ‘debate’ is partly artificial,” and meant to illustrate how clinicians can use their own clinical faculties and reasoning to make an informed decision when treating COVID-19 patients, Dr. Bhimraj said.

The ACCT trial compared remdesivir with placebo in patients with severe enough COVID-19 to require supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The primary outcome in the study was time to recovery, and “the devil is in the details,” Dr. Bhimraj said. The outcomes clinicians should look for in studies are those that matter to patients, such as death, disability, and discomfort, he noted. Disease-oriented endpoints are easier to measure, but not always meaningful for patients, he said. The study showed an average 5-day decrease in illness, “but the fact is that it did not show a mortality benefit,” he noted.

Another large, open-label study of remdesivir across 30 countries showed no survival benefit associated with the drug, compared with standard of care, said Dr. Bhimraj. Patients treated with remdesivir remained in the hospital longer, but Dr. Bhimraj said he believed that was a bias. “I think the physicians kept the patients in the hospital longer to give the treatment rather than the treatments themselves prolonging the treatment duration,” he said.

In conclusion for remdesivir, “the solid data show that there is an early recovery,” he said. “At least for severe disease, even if there is no mortality benefit, there is a role. I argue that, if someone asks if you want to use remdesivir in severe COVID-19 patients, say yes, especially if you value people getting out of the hospital sooner. In a crisis situation, there is a role for remdesivir.”

Dr. Walter discussed the “con” side of using remdesivir. “We can start with a predata hypothesis, but integrate new data about the efficacy into a postdata hypothesis,” he said.

Dr. Walter made several points against the use of remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. First, it has not shown any improvement in mortality and may increase the length of hospital stay, he noted.

Data from the ACCT-1 trial and the WHO solidarity trial, showed “no signal of mortality benefit at all,” he said. In addition, the World Health Organization, American College of Physicians, and National Institutes of Health all recommend against remdesivir for patients who require mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, he said. The efficacy when used with steroids remains unclear, and long-term safety data are lacking, he added.

Taking on tocilizumab

Tocilizumab, an anti-inflammatory agent, has demonstrated an impact on several surrogate markers, notably C-reactive protein, temperature, and oxygenation. Dr. Bhimraj said. He reviewed data from eight published studies on the use of tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients.

Arguably, some trials may not have been powered adequately, and in combination, some trials show an effect on clinical deterioration, if not a mortality benefit, he said.

Consequently, in the context of COVID-19, tocilizumab “should be used early in the disease process, especially if steroids are not working,” said Dr. Bhimraj. Despite the limited evidence, “there is a niche population where this might be beneficial,” he said.

By contrast, Dr. Walter took the position of skepticism about the value of tocilizumab for COVID-19 patients.

Notably, decades of research show that tocilizumab has shown no benefit in patients with sepsis or septic shock, or those with acute respiratory distress syndrome, which have similarities to COVID-19 (JAMA. 2020 Sep 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17052).

He cited a research letter published in JAMA in September 2020, which showed that cytokine levels were in fact lower in critically ill patients with COVID-19, compared with those who had conditions including sepsis with and without ARDS.

Dr. Walter also cited data on the questionable benefit of tocilizumab when used with steroids and the negligible impact on mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients seen in the RECOVERY trial.

Limited data mean that therapeutic decisions related to COVID-19 are more nuanced, but they can be made, the presenters agreed.

Ultimately, when trying to decide whether a drug is efficacious, futile, or harmful, “What we have to do is consider the grand totality of the evidence,” Dr. Bhimraj emphasized.

Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and evidence evolves, clinical judgment is the bottom line for clinical care, according to Adarsh Bhimraj, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and James Walter, MD, of Northwestern Medicine, Chicago.

In a debate/discussion presented at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter took sides in a friendly debate on the value of remdesivir and tocilizumab for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Dr. Bhimraj argued for the use of remdesivir or tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia, and Dr. Walter presented the case against their use.

Referendum on remdesivir

The main sources referenced by the presenters regarding remdesivir were the WHO Solidarity Trial (N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184) and the Adaptive Covid-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT) final report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764).

“The ‘debate’ is partly artificial,” and meant to illustrate how clinicians can use their own clinical faculties and reasoning to make an informed decision when treating COVID-19 patients, Dr. Bhimraj said.

The ACCT trial compared remdesivir with placebo in patients with severe enough COVID-19 to require supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The primary outcome in the study was time to recovery, and “the devil is in the details,” Dr. Bhimraj said. The outcomes clinicians should look for in studies are those that matter to patients, such as death, disability, and discomfort, he noted. Disease-oriented endpoints are easier to measure, but not always meaningful for patients, he said. The study showed an average 5-day decrease in illness, “but the fact is that it did not show a mortality benefit,” he noted.

Another large, open-label study of remdesivir across 30 countries showed no survival benefit associated with the drug, compared with standard of care, said Dr. Bhimraj. Patients treated with remdesivir remained in the hospital longer, but Dr. Bhimraj said he believed that was a bias. “I think the physicians kept the patients in the hospital longer to give the treatment rather than the treatments themselves prolonging the treatment duration,” he said.

In conclusion for remdesivir, “the solid data show that there is an early recovery,” he said. “At least for severe disease, even if there is no mortality benefit, there is a role. I argue that, if someone asks if you want to use remdesivir in severe COVID-19 patients, say yes, especially if you value people getting out of the hospital sooner. In a crisis situation, there is a role for remdesivir.”

Dr. Walter discussed the “con” side of using remdesivir. “We can start with a predata hypothesis, but integrate new data about the efficacy into a postdata hypothesis,” he said.

Dr. Walter made several points against the use of remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. First, it has not shown any improvement in mortality and may increase the length of hospital stay, he noted.

Data from the ACCT-1 trial and the WHO solidarity trial, showed “no signal of mortality benefit at all,” he said. In addition, the World Health Organization, American College of Physicians, and National Institutes of Health all recommend against remdesivir for patients who require mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, he said. The efficacy when used with steroids remains unclear, and long-term safety data are lacking, he added.

Taking on tocilizumab

Tocilizumab, an anti-inflammatory agent, has demonstrated an impact on several surrogate markers, notably C-reactive protein, temperature, and oxygenation. Dr. Bhimraj said. He reviewed data from eight published studies on the use of tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients.

Arguably, some trials may not have been powered adequately, and in combination, some trials show an effect on clinical deterioration, if not a mortality benefit, he said.

Consequently, in the context of COVID-19, tocilizumab “should be used early in the disease process, especially if steroids are not working,” said Dr. Bhimraj. Despite the limited evidence, “there is a niche population where this might be beneficial,” he said.

By contrast, Dr. Walter took the position of skepticism about the value of tocilizumab for COVID-19 patients.

Notably, decades of research show that tocilizumab has shown no benefit in patients with sepsis or septic shock, or those with acute respiratory distress syndrome, which have similarities to COVID-19 (JAMA. 2020 Sep 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17052).

He cited a research letter published in JAMA in September 2020, which showed that cytokine levels were in fact lower in critically ill patients with COVID-19, compared with those who had conditions including sepsis with and without ARDS.

Dr. Walter also cited data on the questionable benefit of tocilizumab when used with steroids and the negligible impact on mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients seen in the RECOVERY trial.

Limited data mean that therapeutic decisions related to COVID-19 are more nuanced, but they can be made, the presenters agreed.

Ultimately, when trying to decide whether a drug is efficacious, futile, or harmful, “What we have to do is consider the grand totality of the evidence,” Dr. Bhimraj emphasized.

Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and evidence evolves, clinical judgment is the bottom line for clinical care, according to Adarsh Bhimraj, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and James Walter, MD, of Northwestern Medicine, Chicago.

In a debate/discussion presented at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter took sides in a friendly debate on the value of remdesivir and tocilizumab for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Dr. Bhimraj argued for the use of remdesivir or tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia, and Dr. Walter presented the case against their use.

Referendum on remdesivir

The main sources referenced by the presenters regarding remdesivir were the WHO Solidarity Trial (N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184) and the Adaptive Covid-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT) final report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764).

“The ‘debate’ is partly artificial,” and meant to illustrate how clinicians can use their own clinical faculties and reasoning to make an informed decision when treating COVID-19 patients, Dr. Bhimraj said.

The ACCT trial compared remdesivir with placebo in patients with severe enough COVID-19 to require supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The primary outcome in the study was time to recovery, and “the devil is in the details,” Dr. Bhimraj said. The outcomes clinicians should look for in studies are those that matter to patients, such as death, disability, and discomfort, he noted. Disease-oriented endpoints are easier to measure, but not always meaningful for patients, he said. The study showed an average 5-day decrease in illness, “but the fact is that it did not show a mortality benefit,” he noted.

Another large, open-label study of remdesivir across 30 countries showed no survival benefit associated with the drug, compared with standard of care, said Dr. Bhimraj. Patients treated with remdesivir remained in the hospital longer, but Dr. Bhimraj said he believed that was a bias. “I think the physicians kept the patients in the hospital longer to give the treatment rather than the treatments themselves prolonging the treatment duration,” he said.

In conclusion for remdesivir, “the solid data show that there is an early recovery,” he said. “At least for severe disease, even if there is no mortality benefit, there is a role. I argue that, if someone asks if you want to use remdesivir in severe COVID-19 patients, say yes, especially if you value people getting out of the hospital sooner. In a crisis situation, there is a role for remdesivir.”

Dr. Walter discussed the “con” side of using remdesivir. “We can start with a predata hypothesis, but integrate new data about the efficacy into a postdata hypothesis,” he said.

Dr. Walter made several points against the use of remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. First, it has not shown any improvement in mortality and may increase the length of hospital stay, he noted.

Data from the ACCT-1 trial and the WHO solidarity trial, showed “no signal of mortality benefit at all,” he said. In addition, the World Health Organization, American College of Physicians, and National Institutes of Health all recommend against remdesivir for patients who require mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, he said. The efficacy when used with steroids remains unclear, and long-term safety data are lacking, he added.

Taking on tocilizumab

Tocilizumab, an anti-inflammatory agent, has demonstrated an impact on several surrogate markers, notably C-reactive protein, temperature, and oxygenation. Dr. Bhimraj said. He reviewed data from eight published studies on the use of tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients.

Arguably, some trials may not have been powered adequately, and in combination, some trials show an effect on clinical deterioration, if not a mortality benefit, he said.

Consequently, in the context of COVID-19, tocilizumab “should be used early in the disease process, especially if steroids are not working,” said Dr. Bhimraj. Despite the limited evidence, “there is a niche population where this might be beneficial,” he said.

By contrast, Dr. Walter took the position of skepticism about the value of tocilizumab for COVID-19 patients.

Notably, decades of research show that tocilizumab has shown no benefit in patients with sepsis or septic shock, or those with acute respiratory distress syndrome, which have similarities to COVID-19 (JAMA. 2020 Sep 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17052).

He cited a research letter published in JAMA in September 2020, which showed that cytokine levels were in fact lower in critically ill patients with COVID-19, compared with those who had conditions including sepsis with and without ARDS.

Dr. Walter also cited data on the questionable benefit of tocilizumab when used with steroids and the negligible impact on mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients seen in the RECOVERY trial.

Limited data mean that therapeutic decisions related to COVID-19 are more nuanced, but they can be made, the presenters agreed.

Ultimately, when trying to decide whether a drug is efficacious, futile, or harmful, “What we have to do is consider the grand totality of the evidence,” Dr. Bhimraj emphasized.

Dr. Bhimraj and Dr. Walter had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Weight-related COVID-19 severity starts in normal BMI range, especially in young

The risk of severe outcomes with COVID-19 increases with excess weight in a linear manner beginning in normal body mass index ranges, with the effect apparently independent of obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, and stronger among younger people and Black persons, new research shows.

“Even a small increase in body mass index above 23 kg/m² is a risk factor for adverse outcomes after infection with SARS-CoV-2,” the authors reported.

“Excess weight is a modifiable risk factor and investment in the treatment of overweight and obesity, and long-term preventive strategies could help reduce the severity of COVID-19 disease,” they wrote.

The findings shed important new light in the ongoing efforts to understand COVID-19 effects, Krishnan Bhaskaran, PhD, said in an interview.

“These results confirm and add detail to the established links between overweight and obesity and COVID-19, and also add new information on risks among people with low BMI levels,” said Dr. Bhaskaran, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who authored an accompanying editorial.

Obesity has been well established as a major risk factor for poor outcomes among people with COVID-19; however, less is known about the risk of severe outcomes over the broader spectrum of excess weight, and its relationship with other factors.

For the prospective, community-based study, Carmen Piernas, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues evaluated data on nearly 7 million individuals registered in the U.K. QResearch database during Jan. 24–April 30, 2020.

Overall, patients had a mean BMI of 27 kg/m². Among them, 13,503 (.20%) were admitted to the hospital during the study period, 1,601 (.02%) were admitted to an ICU and 5,479 (.08%) died after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Risk rises from BMI of 23 kg/m²

In looking at the risk of hospital admission with COVID-19, the authors found a J-shaped relationship with BMI, with the risk increased with a BMI of 20 kg/m² or lower, as well as an increased risk beginning with a BMI of 23 kg/m² – considered normal weight – or higher (hazard ratio, 1.05).

The risk of death from COVID-19 was also J-shaped, however the association with increases in BMI started higher – at 28 kg/m² (adjusted HR 1.04).

In terms of the risk of ICU admission with COVID-19, the curve was not J-shaped, with just a linear association of admission with increasing BMI beginning at 23 kg/m2 (adjusted HR 1.10).

“It was surprising to see that the lowest risk of severe COVID-19 was found at a BMI of 23, and each extra BMI unit was associated with significantly higher risk, but we don’t really know yet what the reason is for this,” Dr. Piernas said in an interview.

The association between increasing BMI and risk of hospital admission for COVID-19 beginning at a BMI of 23 kg/m² was more significant among younger people aged 20-39 years than in those aged 80-100 years, with an adjusted HR for hospital admission per BMI unit above 23 kg/m² of 1.09 versus 1.01 (P < .0001).

In addition, the risk associated with BMI and hospital admission was stronger in people who were Black, compared with those who were White (1.07 vs. 1.04), as was the risk of death due to COVID-19 (1.08 vs. 1.04; P < .0001 for both).

“For the risk of death, Blacks have an 8% higher risk with each extra BMI unit, whereas Whites have a 4% increase, which is half the risk,” Dr. Piernas said.

Notably, the increased risks of hospital admission and ICU due to COVID-19 seen with increases in BMI were slightly lower among people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease compared with patients who did not have those comorbidities, suggesting the association with BMI is not explained by those risk factors.

Dr. Piernas speculated that the effect could reflect that people with diabetes or cardiovascular disease already have a preexisting condition which makes them more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2.

Hence, “the association with BMI in this group may not be as strong as the association found among those without those conditions, in which BMI explains a higher proportion of this increased risk, given the absence of these preexisting conditions.”

Similarly, the effect of BMI on COVID-19 outcomes in younger patients may appear stronger because their rates of other comorbidities are much lower than in older patients.

“Among older people, preexisting conditions and perhaps a weaker immune system may explain their much higher rates of severe COVID outcomes,” Dr. Piernas noted.

Furthermore, older patients may have frailty and high comorbidities that could explain their lower rates of ICU admission with COVID-19, Dr. Bhaskaran added in further comments.

The findings overall underscore that excess weight can represent a risk in COVID-19 outcomes that is, importantly, modifiable, and “suggest that supporting people to reach and maintain a healthy weight is likely to help people reduce their risk of experiencing severe outcomes from this disease, now or in any future waves,” he concluded.

Dr. Piernas and Dr. Bhaskaran had no disclosures to report. Coauthors’ disclosures are detailed in the published study.

The risk of severe outcomes with COVID-19 increases with excess weight in a linear manner beginning in normal body mass index ranges, with the effect apparently independent of obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, and stronger among younger people and Black persons, new research shows.

“Even a small increase in body mass index above 23 kg/m² is a risk factor for adverse outcomes after infection with SARS-CoV-2,” the authors reported.

“Excess weight is a modifiable risk factor and investment in the treatment of overweight and obesity, and long-term preventive strategies could help reduce the severity of COVID-19 disease,” they wrote.

The findings shed important new light in the ongoing efforts to understand COVID-19 effects, Krishnan Bhaskaran, PhD, said in an interview.

“These results confirm and add detail to the established links between overweight and obesity and COVID-19, and also add new information on risks among people with low BMI levels,” said Dr. Bhaskaran, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who authored an accompanying editorial.

Obesity has been well established as a major risk factor for poor outcomes among people with COVID-19; however, less is known about the risk of severe outcomes over the broader spectrum of excess weight, and its relationship with other factors.

For the prospective, community-based study, Carmen Piernas, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues evaluated data on nearly 7 million individuals registered in the U.K. QResearch database during Jan. 24–April 30, 2020.

Overall, patients had a mean BMI of 27 kg/m². Among them, 13,503 (.20%) were admitted to the hospital during the study period, 1,601 (.02%) were admitted to an ICU and 5,479 (.08%) died after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Risk rises from BMI of 23 kg/m²

In looking at the risk of hospital admission with COVID-19, the authors found a J-shaped relationship with BMI, with the risk increased with a BMI of 20 kg/m² or lower, as well as an increased risk beginning with a BMI of 23 kg/m² – considered normal weight – or higher (hazard ratio, 1.05).

The risk of death from COVID-19 was also J-shaped, however the association with increases in BMI started higher – at 28 kg/m² (adjusted HR 1.04).

In terms of the risk of ICU admission with COVID-19, the curve was not J-shaped, with just a linear association of admission with increasing BMI beginning at 23 kg/m2 (adjusted HR 1.10).

“It was surprising to see that the lowest risk of severe COVID-19 was found at a BMI of 23, and each extra BMI unit was associated with significantly higher risk, but we don’t really know yet what the reason is for this,” Dr. Piernas said in an interview.

The association between increasing BMI and risk of hospital admission for COVID-19 beginning at a BMI of 23 kg/m² was more significant among younger people aged 20-39 years than in those aged 80-100 years, with an adjusted HR for hospital admission per BMI unit above 23 kg/m² of 1.09 versus 1.01 (P < .0001).

In addition, the risk associated with BMI and hospital admission was stronger in people who were Black, compared with those who were White (1.07 vs. 1.04), as was the risk of death due to COVID-19 (1.08 vs. 1.04; P < .0001 for both).

“For the risk of death, Blacks have an 8% higher risk with each extra BMI unit, whereas Whites have a 4% increase, which is half the risk,” Dr. Piernas said.

Notably, the increased risks of hospital admission and ICU due to COVID-19 seen with increases in BMI were slightly lower among people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease compared with patients who did not have those comorbidities, suggesting the association with BMI is not explained by those risk factors.

Dr. Piernas speculated that the effect could reflect that people with diabetes or cardiovascular disease already have a preexisting condition which makes them more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2.

Hence, “the association with BMI in this group may not be as strong as the association found among those without those conditions, in which BMI explains a higher proportion of this increased risk, given the absence of these preexisting conditions.”

Similarly, the effect of BMI on COVID-19 outcomes in younger patients may appear stronger because their rates of other comorbidities are much lower than in older patients.

“Among older people, preexisting conditions and perhaps a weaker immune system may explain their much higher rates of severe COVID outcomes,” Dr. Piernas noted.

Furthermore, older patients may have frailty and high comorbidities that could explain their lower rates of ICU admission with COVID-19, Dr. Bhaskaran added in further comments.

The findings overall underscore that excess weight can represent a risk in COVID-19 outcomes that is, importantly, modifiable, and “suggest that supporting people to reach and maintain a healthy weight is likely to help people reduce their risk of experiencing severe outcomes from this disease, now or in any future waves,” he concluded.

Dr. Piernas and Dr. Bhaskaran had no disclosures to report. Coauthors’ disclosures are detailed in the published study.

The risk of severe outcomes with COVID-19 increases with excess weight in a linear manner beginning in normal body mass index ranges, with the effect apparently independent of obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, and stronger among younger people and Black persons, new research shows.

“Even a small increase in body mass index above 23 kg/m² is a risk factor for adverse outcomes after infection with SARS-CoV-2,” the authors reported.

“Excess weight is a modifiable risk factor and investment in the treatment of overweight and obesity, and long-term preventive strategies could help reduce the severity of COVID-19 disease,” they wrote.

The findings shed important new light in the ongoing efforts to understand COVID-19 effects, Krishnan Bhaskaran, PhD, said in an interview.

“These results confirm and add detail to the established links between overweight and obesity and COVID-19, and also add new information on risks among people with low BMI levels,” said Dr. Bhaskaran, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who authored an accompanying editorial.

Obesity has been well established as a major risk factor for poor outcomes among people with COVID-19; however, less is known about the risk of severe outcomes over the broader spectrum of excess weight, and its relationship with other factors.

For the prospective, community-based study, Carmen Piernas, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues evaluated data on nearly 7 million individuals registered in the U.K. QResearch database during Jan. 24–April 30, 2020.

Overall, patients had a mean BMI of 27 kg/m². Among them, 13,503 (.20%) were admitted to the hospital during the study period, 1,601 (.02%) were admitted to an ICU and 5,479 (.08%) died after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Risk rises from BMI of 23 kg/m²

In looking at the risk of hospital admission with COVID-19, the authors found a J-shaped relationship with BMI, with the risk increased with a BMI of 20 kg/m² or lower, as well as an increased risk beginning with a BMI of 23 kg/m² – considered normal weight – or higher (hazard ratio, 1.05).

The risk of death from COVID-19 was also J-shaped, however the association with increases in BMI started higher – at 28 kg/m² (adjusted HR 1.04).

In terms of the risk of ICU admission with COVID-19, the curve was not J-shaped, with just a linear association of admission with increasing BMI beginning at 23 kg/m2 (adjusted HR 1.10).

“It was surprising to see that the lowest risk of severe COVID-19 was found at a BMI of 23, and each extra BMI unit was associated with significantly higher risk, but we don’t really know yet what the reason is for this,” Dr. Piernas said in an interview.

The association between increasing BMI and risk of hospital admission for COVID-19 beginning at a BMI of 23 kg/m² was more significant among younger people aged 20-39 years than in those aged 80-100 years, with an adjusted HR for hospital admission per BMI unit above 23 kg/m² of 1.09 versus 1.01 (P < .0001).

In addition, the risk associated with BMI and hospital admission was stronger in people who were Black, compared with those who were White (1.07 vs. 1.04), as was the risk of death due to COVID-19 (1.08 vs. 1.04; P < .0001 for both).

“For the risk of death, Blacks have an 8% higher risk with each extra BMI unit, whereas Whites have a 4% increase, which is half the risk,” Dr. Piernas said.

Notably, the increased risks of hospital admission and ICU due to COVID-19 seen with increases in BMI were slightly lower among people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease compared with patients who did not have those comorbidities, suggesting the association with BMI is not explained by those risk factors.

Dr. Piernas speculated that the effect could reflect that people with diabetes or cardiovascular disease already have a preexisting condition which makes them more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2.

Hence, “the association with BMI in this group may not be as strong as the association found among those without those conditions, in which BMI explains a higher proportion of this increased risk, given the absence of these preexisting conditions.”

Similarly, the effect of BMI on COVID-19 outcomes in younger patients may appear stronger because their rates of other comorbidities are much lower than in older patients.

“Among older people, preexisting conditions and perhaps a weaker immune system may explain their much higher rates of severe COVID outcomes,” Dr. Piernas noted.

Furthermore, older patients may have frailty and high comorbidities that could explain their lower rates of ICU admission with COVID-19, Dr. Bhaskaran added in further comments.

The findings overall underscore that excess weight can represent a risk in COVID-19 outcomes that is, importantly, modifiable, and “suggest that supporting people to reach and maintain a healthy weight is likely to help people reduce their risk of experiencing severe outcomes from this disease, now or in any future waves,” he concluded.

Dr. Piernas and Dr. Bhaskaran had no disclosures to report. Coauthors’ disclosures are detailed in the published study.

FROM LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

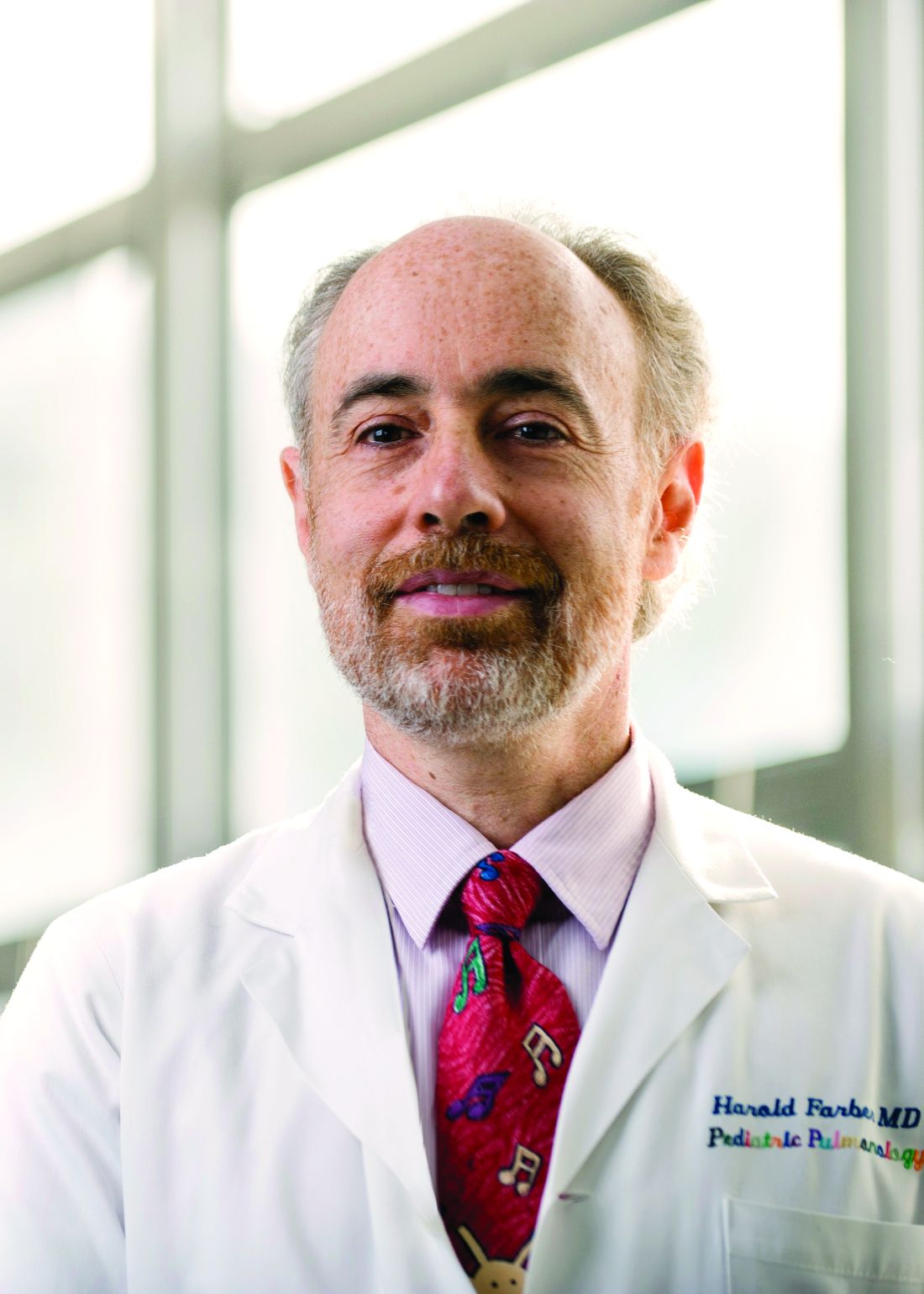

School-based asthma program improves asthma care coordination for children

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.