User login

Mechanical ventilation in children tied to slightly lower IQ

Children who survive an episode of acute respiratory failure that requires invasive mechanical ventilation may be at risk for slightly lower long-term neurocognitive function, new research suggests.

Investigators found lower IQs in children without previous neurocognitive problems who survived pediatric intensive care unit admission for acute respiratory failure, compared with their biological siblings.

Although this magnitude of difference was small on average, more than twice as many patients as siblings had an IQ of ≤85, and children hospitalized at the youngest ages did worse than their siblings.

“Children surviving acute respiratory failure may benefit from routine evaluation of neurocognitive function after hospital discharge and may require serial evaluation to identify deficits that emerge over the course of child’s continued development to facilitate early intervention to prevent disability and optimize school performance,” study investigator R. Scott Watson, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA.

Unknown long-term effects

“Approximately 23,700 U.S. children undergo invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure annually, with unknown long-term effects on neurocognitive function,” the authors write.

“With improvements in pediatric critical care over the past several decades, critical illness–associated mortality has improved dramatically [but] as survivorship has increased, we are starting to learn that many patients and their families suffer from long-term morbidity associated with the illness and its treatment,” said Dr. Watson, who is the associate division chief, pediatric critical care medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development.

Animal studies “have found that some sedative medications commonly used to keep children safe during mechanical ventilation may have detrimental neurologic effects, particularly in the developing brain,” Dr. Watson added.

To gain a better understanding of this potential association, the researchers turned to a subset of participants in the previously conducted Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) trial of pediatric patients receiving mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure.

For the current study (RESTORE-Cognition), multiple domains of neurocognitive function were assessed 3-8 years after hospital discharge in trial patients who did not have a history of neurocognitive dysfunction, as well as matched, healthy siblings.

To be included in the study, the children had to be ≤8 years old at trial enrollment, have a Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score of 1 (normal) prior to PICU admission, and have no worse than moderate neurocognitive dysfunction at PICU discharge.

Siblings of enrolled patients were required to be between 4 and 16 years old at the time of neurocognitive testing, have a PCPC score of 1, have the same biological parents as the patient, and live with the patient.

The primary outcome was IQ, estimated by the age-appropriate Vocabulary and Block Design subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale. Secondary outcomes included attention, processing speed, learning and memory, visuospatial skills, motor skills, language, and executive function. Enough time was allowed after hospitalization “for transient deficits to resolve and longer-lasting neurocognitive sequelae to manifest.”

‘Uncertain’ clinical importance

Of the 121 sibling pairs (67% non-Hispanic White, 47% from families in which one or both parents worked full-time), 116 were included in the primary outcome analysis, and 66-19 were included in analyses of secondary outcomes.

Patients had been in the PICU at a median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of 1.0 (0.2-3.2) years and had received a median of 5.5 (3.1-7.7) days of invasive mechanical ventilation.

The median age at testing for patients and matched siblings was 6.6 (5.4-9.1) and 8.4 (7.0-10.2) years, respectively. Interviews with parents and testing of patients were conducted a median (IQR) of 3.8 (3.2-5.2) and 5.2 (4.3-6.1) years, respectively, after hospitalization.

The most common etiologies of respiratory failure were bronchiolitis and asthma and pneumonia (44% and 37%, respectively). Beyond respiratory failure, most patients (72%) also had experienced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Patients had a lower mean estimated IQ, compared with the matched siblings (101.5 vs. 104.3; mean difference, –2.8 [95% confidence interval, –5.4 to –0.2]), and more patients than siblings had an estimated IQ of ≤5 but not of ≤70.

Patients also had significantly lower scores on nonverbal memory, visuospatial skills, and fine motor control (mean differences, –0.9 [–1.6 to –0.3]; –0.9 [–1.8 to –.1]; and –-3.1 [–4.9 to –1.4], respectively), compared with matched siblings. They also had significantly higher scores on processing speed (mean difference, 4.4 [0.2-8.5]). There were no significant differences in the other secondary outcomes.

Differences in scores between patients and siblings varied significantly by age at hospitalization in several tests – for example, Block Design scores in patients were lower than those of siblings for patients hospitalized at <1 year old, versus those hospitalized between ages 4 and 8 years.

“When adjusting for patient age at PICU admission, patient age at testing, sibling age at testing, and duration between hospital discharge and testing, the difference in estimated IQ between patients and siblings remained statistically significantly different,” the authors note.

The investigators point out several limitations, including the fact that “little is known about sibling outcomes after critical illness, nor about whether parenting of siblings or child development differs based on birth order or on relationship between patient critical illness and the birth of siblings. ... If siblings also incur negative effects related to the critical illness, differences between critically ill children and the control siblings would be blunted.”

Despite the statistical significance of the difference between the patients and the matched controls, ultimately, the magnitude of the difference was “small and of uncertain clinical importance,” the authors conclude.

Filling a research gap

Commenting on the findings, Alexandre T. Rotta, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of the division of pediatric critical care medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said the study “addresses an important yet vastly understudied gap: long-term neurocognitive morbidity in children exposed to critical care.”

Dr. Rotta, who is also a coauthor of an accompanying editorial, noted that the fact that the “vast majority of children with an IQ significantly lower than their siblings were under the age of 4 years suggests that the developing immature brain may be particularly susceptible to the effects of critical illness and therapies required to treat it.”

The study “underscores the need to include assessments of long-term morbidity as part of any future trial evaluating interventions in pediatric critical care,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for RESTORE-Cognition and by grants for the RESTORE trial from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Watson and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rotta has received personal fees from Vapotherm for lecturing and development of educational materials and from Breas US for participation in a scientific advisory board, as well as royalties from Elsevier for editorial work outside the submitted work. His coauthor reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who survive an episode of acute respiratory failure that requires invasive mechanical ventilation may be at risk for slightly lower long-term neurocognitive function, new research suggests.

Investigators found lower IQs in children without previous neurocognitive problems who survived pediatric intensive care unit admission for acute respiratory failure, compared with their biological siblings.

Although this magnitude of difference was small on average, more than twice as many patients as siblings had an IQ of ≤85, and children hospitalized at the youngest ages did worse than their siblings.

“Children surviving acute respiratory failure may benefit from routine evaluation of neurocognitive function after hospital discharge and may require serial evaluation to identify deficits that emerge over the course of child’s continued development to facilitate early intervention to prevent disability and optimize school performance,” study investigator R. Scott Watson, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA.

Unknown long-term effects

“Approximately 23,700 U.S. children undergo invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure annually, with unknown long-term effects on neurocognitive function,” the authors write.

“With improvements in pediatric critical care over the past several decades, critical illness–associated mortality has improved dramatically [but] as survivorship has increased, we are starting to learn that many patients and their families suffer from long-term morbidity associated with the illness and its treatment,” said Dr. Watson, who is the associate division chief, pediatric critical care medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development.

Animal studies “have found that some sedative medications commonly used to keep children safe during mechanical ventilation may have detrimental neurologic effects, particularly in the developing brain,” Dr. Watson added.

To gain a better understanding of this potential association, the researchers turned to a subset of participants in the previously conducted Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) trial of pediatric patients receiving mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure.

For the current study (RESTORE-Cognition), multiple domains of neurocognitive function were assessed 3-8 years after hospital discharge in trial patients who did not have a history of neurocognitive dysfunction, as well as matched, healthy siblings.

To be included in the study, the children had to be ≤8 years old at trial enrollment, have a Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score of 1 (normal) prior to PICU admission, and have no worse than moderate neurocognitive dysfunction at PICU discharge.

Siblings of enrolled patients were required to be between 4 and 16 years old at the time of neurocognitive testing, have a PCPC score of 1, have the same biological parents as the patient, and live with the patient.

The primary outcome was IQ, estimated by the age-appropriate Vocabulary and Block Design subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale. Secondary outcomes included attention, processing speed, learning and memory, visuospatial skills, motor skills, language, and executive function. Enough time was allowed after hospitalization “for transient deficits to resolve and longer-lasting neurocognitive sequelae to manifest.”

‘Uncertain’ clinical importance

Of the 121 sibling pairs (67% non-Hispanic White, 47% from families in which one or both parents worked full-time), 116 were included in the primary outcome analysis, and 66-19 were included in analyses of secondary outcomes.

Patients had been in the PICU at a median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of 1.0 (0.2-3.2) years and had received a median of 5.5 (3.1-7.7) days of invasive mechanical ventilation.

The median age at testing for patients and matched siblings was 6.6 (5.4-9.1) and 8.4 (7.0-10.2) years, respectively. Interviews with parents and testing of patients were conducted a median (IQR) of 3.8 (3.2-5.2) and 5.2 (4.3-6.1) years, respectively, after hospitalization.

The most common etiologies of respiratory failure were bronchiolitis and asthma and pneumonia (44% and 37%, respectively). Beyond respiratory failure, most patients (72%) also had experienced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Patients had a lower mean estimated IQ, compared with the matched siblings (101.5 vs. 104.3; mean difference, –2.8 [95% confidence interval, –5.4 to –0.2]), and more patients than siblings had an estimated IQ of ≤5 but not of ≤70.

Patients also had significantly lower scores on nonverbal memory, visuospatial skills, and fine motor control (mean differences, –0.9 [–1.6 to –0.3]; –0.9 [–1.8 to –.1]; and –-3.1 [–4.9 to –1.4], respectively), compared with matched siblings. They also had significantly higher scores on processing speed (mean difference, 4.4 [0.2-8.5]). There were no significant differences in the other secondary outcomes.

Differences in scores between patients and siblings varied significantly by age at hospitalization in several tests – for example, Block Design scores in patients were lower than those of siblings for patients hospitalized at <1 year old, versus those hospitalized between ages 4 and 8 years.

“When adjusting for patient age at PICU admission, patient age at testing, sibling age at testing, and duration between hospital discharge and testing, the difference in estimated IQ between patients and siblings remained statistically significantly different,” the authors note.

The investigators point out several limitations, including the fact that “little is known about sibling outcomes after critical illness, nor about whether parenting of siblings or child development differs based on birth order or on relationship between patient critical illness and the birth of siblings. ... If siblings also incur negative effects related to the critical illness, differences between critically ill children and the control siblings would be blunted.”

Despite the statistical significance of the difference between the patients and the matched controls, ultimately, the magnitude of the difference was “small and of uncertain clinical importance,” the authors conclude.

Filling a research gap

Commenting on the findings, Alexandre T. Rotta, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of the division of pediatric critical care medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said the study “addresses an important yet vastly understudied gap: long-term neurocognitive morbidity in children exposed to critical care.”

Dr. Rotta, who is also a coauthor of an accompanying editorial, noted that the fact that the “vast majority of children with an IQ significantly lower than their siblings were under the age of 4 years suggests that the developing immature brain may be particularly susceptible to the effects of critical illness and therapies required to treat it.”

The study “underscores the need to include assessments of long-term morbidity as part of any future trial evaluating interventions in pediatric critical care,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for RESTORE-Cognition and by grants for the RESTORE trial from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Watson and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rotta has received personal fees from Vapotherm for lecturing and development of educational materials and from Breas US for participation in a scientific advisory board, as well as royalties from Elsevier for editorial work outside the submitted work. His coauthor reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who survive an episode of acute respiratory failure that requires invasive mechanical ventilation may be at risk for slightly lower long-term neurocognitive function, new research suggests.

Investigators found lower IQs in children without previous neurocognitive problems who survived pediatric intensive care unit admission for acute respiratory failure, compared with their biological siblings.

Although this magnitude of difference was small on average, more than twice as many patients as siblings had an IQ of ≤85, and children hospitalized at the youngest ages did worse than their siblings.

“Children surviving acute respiratory failure may benefit from routine evaluation of neurocognitive function after hospital discharge and may require serial evaluation to identify deficits that emerge over the course of child’s continued development to facilitate early intervention to prevent disability and optimize school performance,” study investigator R. Scott Watson, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA.

Unknown long-term effects

“Approximately 23,700 U.S. children undergo invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure annually, with unknown long-term effects on neurocognitive function,” the authors write.

“With improvements in pediatric critical care over the past several decades, critical illness–associated mortality has improved dramatically [but] as survivorship has increased, we are starting to learn that many patients and their families suffer from long-term morbidity associated with the illness and its treatment,” said Dr. Watson, who is the associate division chief, pediatric critical care medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development.

Animal studies “have found that some sedative medications commonly used to keep children safe during mechanical ventilation may have detrimental neurologic effects, particularly in the developing brain,” Dr. Watson added.

To gain a better understanding of this potential association, the researchers turned to a subset of participants in the previously conducted Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) trial of pediatric patients receiving mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure.

For the current study (RESTORE-Cognition), multiple domains of neurocognitive function were assessed 3-8 years after hospital discharge in trial patients who did not have a history of neurocognitive dysfunction, as well as matched, healthy siblings.

To be included in the study, the children had to be ≤8 years old at trial enrollment, have a Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score of 1 (normal) prior to PICU admission, and have no worse than moderate neurocognitive dysfunction at PICU discharge.

Siblings of enrolled patients were required to be between 4 and 16 years old at the time of neurocognitive testing, have a PCPC score of 1, have the same biological parents as the patient, and live with the patient.

The primary outcome was IQ, estimated by the age-appropriate Vocabulary and Block Design subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale. Secondary outcomes included attention, processing speed, learning and memory, visuospatial skills, motor skills, language, and executive function. Enough time was allowed after hospitalization “for transient deficits to resolve and longer-lasting neurocognitive sequelae to manifest.”

‘Uncertain’ clinical importance

Of the 121 sibling pairs (67% non-Hispanic White, 47% from families in which one or both parents worked full-time), 116 were included in the primary outcome analysis, and 66-19 were included in analyses of secondary outcomes.

Patients had been in the PICU at a median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of 1.0 (0.2-3.2) years and had received a median of 5.5 (3.1-7.7) days of invasive mechanical ventilation.

The median age at testing for patients and matched siblings was 6.6 (5.4-9.1) and 8.4 (7.0-10.2) years, respectively. Interviews with parents and testing of patients were conducted a median (IQR) of 3.8 (3.2-5.2) and 5.2 (4.3-6.1) years, respectively, after hospitalization.

The most common etiologies of respiratory failure were bronchiolitis and asthma and pneumonia (44% and 37%, respectively). Beyond respiratory failure, most patients (72%) also had experienced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Patients had a lower mean estimated IQ, compared with the matched siblings (101.5 vs. 104.3; mean difference, –2.8 [95% confidence interval, –5.4 to –0.2]), and more patients than siblings had an estimated IQ of ≤5 but not of ≤70.

Patients also had significantly lower scores on nonverbal memory, visuospatial skills, and fine motor control (mean differences, –0.9 [–1.6 to –0.3]; –0.9 [–1.8 to –.1]; and –-3.1 [–4.9 to –1.4], respectively), compared with matched siblings. They also had significantly higher scores on processing speed (mean difference, 4.4 [0.2-8.5]). There were no significant differences in the other secondary outcomes.

Differences in scores between patients and siblings varied significantly by age at hospitalization in several tests – for example, Block Design scores in patients were lower than those of siblings for patients hospitalized at <1 year old, versus those hospitalized between ages 4 and 8 years.

“When adjusting for patient age at PICU admission, patient age at testing, sibling age at testing, and duration between hospital discharge and testing, the difference in estimated IQ between patients and siblings remained statistically significantly different,” the authors note.

The investigators point out several limitations, including the fact that “little is known about sibling outcomes after critical illness, nor about whether parenting of siblings or child development differs based on birth order or on relationship between patient critical illness and the birth of siblings. ... If siblings also incur negative effects related to the critical illness, differences between critically ill children and the control siblings would be blunted.”

Despite the statistical significance of the difference between the patients and the matched controls, ultimately, the magnitude of the difference was “small and of uncertain clinical importance,” the authors conclude.

Filling a research gap

Commenting on the findings, Alexandre T. Rotta, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of the division of pediatric critical care medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said the study “addresses an important yet vastly understudied gap: long-term neurocognitive morbidity in children exposed to critical care.”

Dr. Rotta, who is also a coauthor of an accompanying editorial, noted that the fact that the “vast majority of children with an IQ significantly lower than their siblings were under the age of 4 years suggests that the developing immature brain may be particularly susceptible to the effects of critical illness and therapies required to treat it.”

The study “underscores the need to include assessments of long-term morbidity as part of any future trial evaluating interventions in pediatric critical care,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for RESTORE-Cognition and by grants for the RESTORE trial from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Watson and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rotta has received personal fees from Vapotherm for lecturing and development of educational materials and from Breas US for participation in a scientific advisory board, as well as royalties from Elsevier for editorial work outside the submitted work. His coauthor reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Nirsevimab protects healthy infants from RSV

A single injection of the experimental agent nirsevimab ahead of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) season protects healthy infants from lower respiratory tract infections associated with the pathogen, according to the results of a phase 3 study.

A previously published trial showed that a single dose of nirsevimab was effective in preterm infants. The ability to protect all babies from RSV, which causes bronchiolitis and pneumonia and is a leading cause of hospitalization for this age group, “would be a paradigm shift in the approach to this disease,” William Muller, MD, PhD, of the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and a coauthor of the study, said in a statement.

The primary endpoint of the study was medically attended lower respiratory tract infections linked to RSV. The single injection of nirsevimab was associated with a 74.5% reduction in such infections (P < .001), according to Dr. Muller’s group, who published their findings March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Nirsevimab, a monoclonal antibody to the RSV fusion protein being developed by AstraZeneca and Sanofi, has an extended half-life, which may allow one dose to confer protection throughout a season. The only approved option to prevent RSV, palivizumab (Synagis), is used for high-risk infants, and five injections are needed to cover a viral season.

Nearly 1,500 infants in more than 20 countries studied

To assess the effectiveness of nirsevimab in late-preterm and term infants, investigators at 160 sites randomly assigned 1,490 babies born at a gestational age of at least 35 weeks to receive an intramuscular injection of nirsevimab or placebo.

During the 150 days after injection, medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections occurred in 12 of 994 infants who received nirsevimab, compared with 25 of 496 babies who received placebo (1.2% vs. 5%).

Six of 994 infants who received nirsevimab were hospitalized for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections, compared with 8 of 496 infants in the placebo group (0.6% vs. 1.6%; P = .07). The proportion of children hospitalized for any respiratory illness as a result of RSV was 0.9% among those who received nirsevimab, compared with 2.2% among those who received placebo.

Serious adverse events occurred in 6.8% of the nirsevimab group and 7.3% of the placebo group. None of these events, including three deaths in the nirsevimab group, was considered related to nirsevimab or placebo, according to the researchers. One infant who received nirsevimab had a generalized macular rash without systemic features that did not require treatment and resolved in 20 days, they said.

Antidrug antibodies were detected in 6.1% of the nirsevimab group and in 1.1% of the placebo group. These antidrug antibodies tended to develop later and did not affect nirsevimab pharmacokinetics during the RSV season, the researchers reported. How they might affect subsequent doses of nirsevimab is not known, they added.

In a separate report in the journal, researcher Joseph Domachowske, MD, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, and colleagues described safety results from an ongoing study of nirsevimab that includes infants with congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, and prematurity.

In this trial, infants received nirsevimab or palivizumab, and the treatments appeared to have similar safety profiles, the authors reported.

Other approaches to RSV protection include passive antibodies acquired from maternal vaccination in pregnancy and active vaccination of infants.

The publication follows news last month that GlaxoSmithKline is pausing a maternal RSV vaccine trial, which “had the same goal of protecting babies against severe RSV infection,” said Louis Bont, MD, PhD, with University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands.

RSV infection is one of the deadliest diseases during infancy, and the nirsevimab trial, conducted in more than 20 countries, is “gamechanging,” Dr. Bont told this news organization. Still, researchers will need to monitor for RSV resistance to this treatment, he said.

Whether nirsevimab prevents the development of reactive airway disease and asthma is another open question, he said.

“Finally, we need to keep in mind that RSV mortality is almost limited to the developing world, and it is unlikely that this novel drug will become available to these countries in the coming years,” Dr. Bont said. “Nevertheless, nirsevimab has the potential to seriously decrease the annual overwhelming number of RSV infected babies.”

Nirsevimab may have advantages in low- and middle-income countries, including its potential to be incorporated into established immunization programs and to be given seasonally, said Amy Sarah Ginsburg, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle. “However, cost remains a significant factor, as does susceptibility to pathogen escape,” she said.

MedImmune/AstraZeneca and Sanofi funded the nirsevimab studies. UMC Utrecht has received research grants and fees for advisory work from AstraZeneca for RSV-related work by Bont.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single injection of the experimental agent nirsevimab ahead of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) season protects healthy infants from lower respiratory tract infections associated with the pathogen, according to the results of a phase 3 study.

A previously published trial showed that a single dose of nirsevimab was effective in preterm infants. The ability to protect all babies from RSV, which causes bronchiolitis and pneumonia and is a leading cause of hospitalization for this age group, “would be a paradigm shift in the approach to this disease,” William Muller, MD, PhD, of the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and a coauthor of the study, said in a statement.

The primary endpoint of the study was medically attended lower respiratory tract infections linked to RSV. The single injection of nirsevimab was associated with a 74.5% reduction in such infections (P < .001), according to Dr. Muller’s group, who published their findings March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Nirsevimab, a monoclonal antibody to the RSV fusion protein being developed by AstraZeneca and Sanofi, has an extended half-life, which may allow one dose to confer protection throughout a season. The only approved option to prevent RSV, palivizumab (Synagis), is used for high-risk infants, and five injections are needed to cover a viral season.

Nearly 1,500 infants in more than 20 countries studied

To assess the effectiveness of nirsevimab in late-preterm and term infants, investigators at 160 sites randomly assigned 1,490 babies born at a gestational age of at least 35 weeks to receive an intramuscular injection of nirsevimab or placebo.

During the 150 days after injection, medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections occurred in 12 of 994 infants who received nirsevimab, compared with 25 of 496 babies who received placebo (1.2% vs. 5%).

Six of 994 infants who received nirsevimab were hospitalized for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections, compared with 8 of 496 infants in the placebo group (0.6% vs. 1.6%; P = .07). The proportion of children hospitalized for any respiratory illness as a result of RSV was 0.9% among those who received nirsevimab, compared with 2.2% among those who received placebo.

Serious adverse events occurred in 6.8% of the nirsevimab group and 7.3% of the placebo group. None of these events, including three deaths in the nirsevimab group, was considered related to nirsevimab or placebo, according to the researchers. One infant who received nirsevimab had a generalized macular rash without systemic features that did not require treatment and resolved in 20 days, they said.

Antidrug antibodies were detected in 6.1% of the nirsevimab group and in 1.1% of the placebo group. These antidrug antibodies tended to develop later and did not affect nirsevimab pharmacokinetics during the RSV season, the researchers reported. How they might affect subsequent doses of nirsevimab is not known, they added.

In a separate report in the journal, researcher Joseph Domachowske, MD, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, and colleagues described safety results from an ongoing study of nirsevimab that includes infants with congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, and prematurity.

In this trial, infants received nirsevimab or palivizumab, and the treatments appeared to have similar safety profiles, the authors reported.

Other approaches to RSV protection include passive antibodies acquired from maternal vaccination in pregnancy and active vaccination of infants.

The publication follows news last month that GlaxoSmithKline is pausing a maternal RSV vaccine trial, which “had the same goal of protecting babies against severe RSV infection,” said Louis Bont, MD, PhD, with University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands.

RSV infection is one of the deadliest diseases during infancy, and the nirsevimab trial, conducted in more than 20 countries, is “gamechanging,” Dr. Bont told this news organization. Still, researchers will need to monitor for RSV resistance to this treatment, he said.

Whether nirsevimab prevents the development of reactive airway disease and asthma is another open question, he said.

“Finally, we need to keep in mind that RSV mortality is almost limited to the developing world, and it is unlikely that this novel drug will become available to these countries in the coming years,” Dr. Bont said. “Nevertheless, nirsevimab has the potential to seriously decrease the annual overwhelming number of RSV infected babies.”

Nirsevimab may have advantages in low- and middle-income countries, including its potential to be incorporated into established immunization programs and to be given seasonally, said Amy Sarah Ginsburg, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle. “However, cost remains a significant factor, as does susceptibility to pathogen escape,” she said.

MedImmune/AstraZeneca and Sanofi funded the nirsevimab studies. UMC Utrecht has received research grants and fees for advisory work from AstraZeneca for RSV-related work by Bont.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single injection of the experimental agent nirsevimab ahead of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) season protects healthy infants from lower respiratory tract infections associated with the pathogen, according to the results of a phase 3 study.

A previously published trial showed that a single dose of nirsevimab was effective in preterm infants. The ability to protect all babies from RSV, which causes bronchiolitis and pneumonia and is a leading cause of hospitalization for this age group, “would be a paradigm shift in the approach to this disease,” William Muller, MD, PhD, of the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and a coauthor of the study, said in a statement.

The primary endpoint of the study was medically attended lower respiratory tract infections linked to RSV. The single injection of nirsevimab was associated with a 74.5% reduction in such infections (P < .001), according to Dr. Muller’s group, who published their findings March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Nirsevimab, a monoclonal antibody to the RSV fusion protein being developed by AstraZeneca and Sanofi, has an extended half-life, which may allow one dose to confer protection throughout a season. The only approved option to prevent RSV, palivizumab (Synagis), is used for high-risk infants, and five injections are needed to cover a viral season.

Nearly 1,500 infants in more than 20 countries studied

To assess the effectiveness of nirsevimab in late-preterm and term infants, investigators at 160 sites randomly assigned 1,490 babies born at a gestational age of at least 35 weeks to receive an intramuscular injection of nirsevimab or placebo.

During the 150 days after injection, medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections occurred in 12 of 994 infants who received nirsevimab, compared with 25 of 496 babies who received placebo (1.2% vs. 5%).

Six of 994 infants who received nirsevimab were hospitalized for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections, compared with 8 of 496 infants in the placebo group (0.6% vs. 1.6%; P = .07). The proportion of children hospitalized for any respiratory illness as a result of RSV was 0.9% among those who received nirsevimab, compared with 2.2% among those who received placebo.

Serious adverse events occurred in 6.8% of the nirsevimab group and 7.3% of the placebo group. None of these events, including three deaths in the nirsevimab group, was considered related to nirsevimab or placebo, according to the researchers. One infant who received nirsevimab had a generalized macular rash without systemic features that did not require treatment and resolved in 20 days, they said.

Antidrug antibodies were detected in 6.1% of the nirsevimab group and in 1.1% of the placebo group. These antidrug antibodies tended to develop later and did not affect nirsevimab pharmacokinetics during the RSV season, the researchers reported. How they might affect subsequent doses of nirsevimab is not known, they added.

In a separate report in the journal, researcher Joseph Domachowske, MD, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, and colleagues described safety results from an ongoing study of nirsevimab that includes infants with congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, and prematurity.

In this trial, infants received nirsevimab or palivizumab, and the treatments appeared to have similar safety profiles, the authors reported.

Other approaches to RSV protection include passive antibodies acquired from maternal vaccination in pregnancy and active vaccination of infants.

The publication follows news last month that GlaxoSmithKline is pausing a maternal RSV vaccine trial, which “had the same goal of protecting babies against severe RSV infection,” said Louis Bont, MD, PhD, with University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands.

RSV infection is one of the deadliest diseases during infancy, and the nirsevimab trial, conducted in more than 20 countries, is “gamechanging,” Dr. Bont told this news organization. Still, researchers will need to monitor for RSV resistance to this treatment, he said.

Whether nirsevimab prevents the development of reactive airway disease and asthma is another open question, he said.

“Finally, we need to keep in mind that RSV mortality is almost limited to the developing world, and it is unlikely that this novel drug will become available to these countries in the coming years,” Dr. Bont said. “Nevertheless, nirsevimab has the potential to seriously decrease the annual overwhelming number of RSV infected babies.”

Nirsevimab may have advantages in low- and middle-income countries, including its potential to be incorporated into established immunization programs and to be given seasonally, said Amy Sarah Ginsburg, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle. “However, cost remains a significant factor, as does susceptibility to pathogen escape,” she said.

MedImmune/AstraZeneca and Sanofi funded the nirsevimab studies. UMC Utrecht has received research grants and fees for advisory work from AstraZeneca for RSV-related work by Bont.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Preliminary Observations of Veterans Without HIV Who Have Mycobacterium avium Complex Pulmonary Disease

Nontuberculous Mycobacterium (NTM) is a ubiquitous organism known to cause a variety of infections in susceptible hosts; however, pulmonary infection is the most common. Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is the most prevalent cause of NTM-related pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) and is associated with underlying structural lung disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.1-3

Diagnosis of NTM-PD requires (1) symptoms or radiographic abnormality; and (2) at least 2 sputum cultures positive with the same organism or at least 1 positive culture result on bronchoscopy (wash, lavage, or biopsy).1 Notably, the natural history of untreated NTM-PD varies, though even mild disease may progress substantially.4-6 Progressive disease is more likely to occur in those with a positive smear or more extensive radiographic findings at the initial diagnosis.7 A nationwide Medicare-based study showed that patients with NTM-PD had a higher rate of all-cause mortality than did patients without NTM-PD.8 In a study of 123 patients from Taiwan with MAC-PD, lack of treatment was an independent predictor of mortality.9 Given the risk of progressive morbidity and mortality, recent guidelines recommend initiation of a susceptibility driven, macrolide-based, 3-drug treatment regimen over watchful waiting.10

MAC-PD is increasingly recognized among US veterans.11,12 The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in south/west Chicago serves a large, predominantly Black male population of veterans many of whom are socioeconomically underresourced, and half are aged ≥ 65 years. We observed that initiation of guideline-directed therapy in veterans with MAC-PD at JBVAMC varied among health care professionals (HCPs) in the pulmonary clinic. Therefore, the purpose of this retrospective study was to describe and compare the characteristics of veterans without HIV were diagnosed with MAC-PD and managed at JBVAMC.

Methods

The hospital microbiology department identified veterans diagnosed with NTM at JBVAMC between October 2008 and July 2019. Veterans included in the study were considered to have MAC-PD per American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ISDA) guidelines and those diagnosed with HIV were excluded from analysis. The electronic health record (EHR) was queried for pertinent demographics, smoking history, comorbidities, and symptoms at the time of a positive mycobacterial culture. Computed tomography (CT) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) performed within 1 year of diagnosis were included. PFTs were assessed in accordance with Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, with normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) values defined as ≥ 80% and a normal FEV1/FVC ratio defined as ≥ 70. The diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was assessed per 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS) technical standards and was considered reduced if below the lower limit of normal.13 Information regarding treatment decisions, initiation, and cessation were collected. All-cause mortality was recorded if available in the EHR at the time of data collection.

Statistical analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney U and Fisher exact tests where appropriate. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the JBVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 43 veterans who had a positive culture for MAC; however, only 19 veterans met the diagnostic criteria for MAC-PD and were included in the study (Table). The cohort included predominantly Black and male veterans with a median age of 74 years at time of diagnosis (range, 45-92). Sixteen veterans had underlying lung disease (84.2%), and 16 (84.2%) were current or former smokers. Common comorbidities included COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and lung cancer. Respiratory symptoms were reported in 17 veterans (89.5%), 15 (78.9%) had a chronic cough, and 10 (52.6%) had dyspnea. Fifteen veterans had a chest CT scan within 1 year of diagnosis: A nodular and tree-in-bud pattern was most commonly found in 13 (86.7%) of veterans. Thirteen veterans had PFTs within 1 year of MAC-PD diagnosis, of whom 6 had a restrictive pattern with percent predicted FVC < 80%, and 9 had evidence of obstruction with FEV1/FVC < 70. DLCO was below the lower limit of normal in 18 veterans. Finally, 6 veterans were deceased at the time of the study.

Of the 19 veterans, guideline-directed, combination antimycobacterial therapy for MAC-PD was initiated in only 10 (52.6%) patients due to presence of symptoms and/or imaging abnormalities. Treatment was deferred due to improved symptoms, concern for adverse events (AEs), or lost to follow-up. Five veterans stopped treatment prematurely due to AEs, lost to follow-up, or all-cause mortality. Assessment of differences between treated and untreated groups revealed no significant difference in race, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), symptom presence, or chest CT abnormalities. There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality (40% and 22.2% in treated and untreated group, respectively).

To further understand the differences of this cohort, the 13 veterans alive at time of the study were compared with the 6 who had since died of all-cause mortality. No statistically significant differences were found.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports in the literature, veterans in our cohort were predominantly current or former smoking males with underlying COPD and bronchiectasis.1-3,11,12 Chest CT findings varied: Most veterans presented not only with nodules and tree-in-bud opacities, but also a high frequency of fibrosis and emphysema. PFTs revealed a variety of obstruction and restrictive patterns, and most veterans had a reduced DLCO, though it is unclear whether this is reflective of underlying emphysema, fibrosis, or an alternative cardiopulmonary disease.13,14

While underlying structural lung disease may have been a risk factor for MAC-PD in this cohort, the contribution of environmental and domiciliary factors in metropolitan Chicago neighborhoods is unknown. JBVAMC serves an underresourced population who live in the west and south Chicago neighborhoods. Household factors, ambient and indoor air pollution, and potential contamination of the water supply and surface soil may contribute to the prevalence of MAC-PD in this group.15-19 Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.

Recent ATS, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, and IDSA guidelines recommend combination antimycobacterial therapy for patients who meet clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria for the diagnosis of MAC-PD.10 Patients who meet these diagnostic criteria, particularly patients with smear positivity or fibrocavitary disease, should be treated because of risk of unfavorable outcomes.15,20-22 However, we found that the initiation of guideline-recommended antimycobacterial therapy in veterans without HIV with MAC-PD were inconsistent among HCPs. The reasons underlying this phenomenon were not apparent beyond cited reasons for treatment initiation or deference. Despite this inconsistency, there was no clear difference in age, BMI, symptom burden, radiographic abnormality, or all-cause mortality between treatment groups. Existing studies support slow but substantial progression of untreated MAC-PD, and while treatment prevents deterioration of the disease, it does not prevent progression of bronchiectasis.6 The natural history of MAC-PD in this veteran cohort has yet to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, the 50% treatment dropout rate was higher than previously reported rates (11-33%).5 However, the small number of veterans in this study precludes meaningful comparison with similar reports in the literature.

Limitations

The limitations of this small, single-center, retrospective study prevent a robust, generalizable comparison between groups. Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.24-26

Conclusions

These data suggest that clinical, imaging, and treatment attributes of MAC-PD in veterans without HIV who reside in metropolitan Chicago are heterogeneous and are associated with a relatively high mortality rate. Although there was no difference in the attributes or outcomes of veterans who did and did not initiate treatment despite current recommendations, further studies are needed to better explore these relationships.

1. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/ IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Apr 1;175(7):744-5. Dosage error in article text]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

2. Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):970-976. doi:10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC

3. Winthrop KL, Marras TK, Adjemian J, Zhang H, Wang P, Zhang Q. Incidence and prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in a large U.S. managed care health plan, 2008-2015. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(2):178-185. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-236OC

4. Field SK, Fisher D, Cowie RL. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2004;126(2):566-581. doi:10.1378/chest.126.2.566

5. Kimizuka Y, Hoshino Y, Nishimura T, et al. Retrospective evaluation of natural course in mild cases of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216034. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216034

6. Kotilainen H, Valtonen V, Tukiainen P, Poussa T, Eskola J, Järvinen A. Clinical findings in relation to mortality in nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: patients with Mycobacterium avium complex have better survival than patients with other mycobacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(9):1909-1918. doi:10.1007/s10096-015-2432-8.

7. Hwang JA, Kim S, Jo KW, Shim TS. Natural history of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease in untreated patients with stable course. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1600537. Published 2017 Mar 8. doi:10.1183/13993003.00537-2016

8. Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):881-886. doi:10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC

9. Wang PH, Pan SW, Shu CC, et al. Clinical course and risk factors of mortality in Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease without initial treatment. Respir Med. 2020;171:106070. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106070

10. Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ ERS/ESCMID/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Dec 31;71(11):3023]. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(4):e1-e36. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa241

11. Mirsaeidi M, Hadid W, Ericsoussi B, Rodgers D, Sadikot RT. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease is common in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(11):e1000-e1004. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.03.018

12. Oda G, Winters MA, Pacheco SM, et al. Clusters of nontuberculous mycobacteria linked to water sources at three Veterans Affairs medical centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(3):320-330. doi:10.1017/ice.2019.342

13. Stanojevic S, Graham BL, Cooper BG, et al. Official ERS technical standards: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for the carbon monoxide transfer factor for Caucasians [published correction appears in Eur Respir J. 2020 Oct 15;56(4):]. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700010. Published 2017 Sep 11. doi:10.1183/13993003.00010-2017

14. Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):720-735. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00034905

15. Chalmers JD, Balavoine C, Castellotti PF, et al. European Respiratory Society International Congress, Madrid, 2019: nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease highlights. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00317-2020. Published 2020 Oct 19. doi:10.1183/23120541.00317-2020

16. Hamilton LA, Falkinham JO. Aerosolization of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus from a household ultrasonic humidifier. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67(10):1491-1495. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.000822

17. Hannah CE, Ford BA, Chung J, Ince D, Wanat KA. Characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections at a midwestern tertiary hospital: a retrospective study of 365 patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(6):ofaa173. Published 2020 May 25. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa173

18. Rautiala S, Torvinen E, Torkko P, et al. Potentially pathogenic, slow-growing mycobacteria released into workplace air during the remediation of buildings. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1(1):1-6. doi:10.1080/15459620490250008

19. Tzou CL, Dirac MA, Becker AL, et al. Association between Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease and mycobacteria in home water and soil. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(1):57-62. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-915OC

20. Daley CL, Winthrop KL. Mycobacterium avium complex: addressing gaps in diagnosis and management. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(suppl 4):S199-S211. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa354 21. Kwon BS, Lee JH, Koh Y, et al. The natural history of noncavitary nodular bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Respir Med. 2019;150:45-50. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.007

22. Nasiri MJ, Ebrahimi G, Arefzadeh S, Zamani S, Nikpor Z, Mirsaeidi M. Antibiotic therapy success rate in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020;18(3):263- 273. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1720650

23. Diel R, Lipman M, Hoefsloot W. High mortality in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):206. Published 2018 May 3. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3113-x

24. Marras TK, Prevots DR, Jamieson FB, Winthrop KL; Pulmonary MAC Outcomes Group. Opinions differ by expertise in Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):17-22. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-136OC

25. Plotinsky RN, Talbot EA, von Reyn CF. Proposed definitions for epidemiologic and clinical studies of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e77385. Published 2013 Nov 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077385

26. Swenson C, Zerbe CS, Fennelly K. Host variability in NTM disease: implications for research needs. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2901. Published 2018 Dec 3. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02901

Nontuberculous Mycobacterium (NTM) is a ubiquitous organism known to cause a variety of infections in susceptible hosts; however, pulmonary infection is the most common. Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is the most prevalent cause of NTM-related pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) and is associated with underlying structural lung disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.1-3

Diagnosis of NTM-PD requires (1) symptoms or radiographic abnormality; and (2) at least 2 sputum cultures positive with the same organism or at least 1 positive culture result on bronchoscopy (wash, lavage, or biopsy).1 Notably, the natural history of untreated NTM-PD varies, though even mild disease may progress substantially.4-6 Progressive disease is more likely to occur in those with a positive smear or more extensive radiographic findings at the initial diagnosis.7 A nationwide Medicare-based study showed that patients with NTM-PD had a higher rate of all-cause mortality than did patients without NTM-PD.8 In a study of 123 patients from Taiwan with MAC-PD, lack of treatment was an independent predictor of mortality.9 Given the risk of progressive morbidity and mortality, recent guidelines recommend initiation of a susceptibility driven, macrolide-based, 3-drug treatment regimen over watchful waiting.10

MAC-PD is increasingly recognized among US veterans.11,12 The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in south/west Chicago serves a large, predominantly Black male population of veterans many of whom are socioeconomically underresourced, and half are aged ≥ 65 years. We observed that initiation of guideline-directed therapy in veterans with MAC-PD at JBVAMC varied among health care professionals (HCPs) in the pulmonary clinic. Therefore, the purpose of this retrospective study was to describe and compare the characteristics of veterans without HIV were diagnosed with MAC-PD and managed at JBVAMC.

Methods

The hospital microbiology department identified veterans diagnosed with NTM at JBVAMC between October 2008 and July 2019. Veterans included in the study were considered to have MAC-PD per American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ISDA) guidelines and those diagnosed with HIV were excluded from analysis. The electronic health record (EHR) was queried for pertinent demographics, smoking history, comorbidities, and symptoms at the time of a positive mycobacterial culture. Computed tomography (CT) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) performed within 1 year of diagnosis were included. PFTs were assessed in accordance with Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, with normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) values defined as ≥ 80% and a normal FEV1/FVC ratio defined as ≥ 70. The diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was assessed per 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS) technical standards and was considered reduced if below the lower limit of normal.13 Information regarding treatment decisions, initiation, and cessation were collected. All-cause mortality was recorded if available in the EHR at the time of data collection.

Statistical analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney U and Fisher exact tests where appropriate. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the JBVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

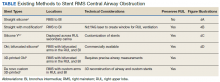

We identified 43 veterans who had a positive culture for MAC; however, only 19 veterans met the diagnostic criteria for MAC-PD and were included in the study (Table). The cohort included predominantly Black and male veterans with a median age of 74 years at time of diagnosis (range, 45-92). Sixteen veterans had underlying lung disease (84.2%), and 16 (84.2%) were current or former smokers. Common comorbidities included COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and lung cancer. Respiratory symptoms were reported in 17 veterans (89.5%), 15 (78.9%) had a chronic cough, and 10 (52.6%) had dyspnea. Fifteen veterans had a chest CT scan within 1 year of diagnosis: A nodular and tree-in-bud pattern was most commonly found in 13 (86.7%) of veterans. Thirteen veterans had PFTs within 1 year of MAC-PD diagnosis, of whom 6 had a restrictive pattern with percent predicted FVC < 80%, and 9 had evidence of obstruction with FEV1/FVC < 70. DLCO was below the lower limit of normal in 18 veterans. Finally, 6 veterans were deceased at the time of the study.

Of the 19 veterans, guideline-directed, combination antimycobacterial therapy for MAC-PD was initiated in only 10 (52.6%) patients due to presence of symptoms and/or imaging abnormalities. Treatment was deferred due to improved symptoms, concern for adverse events (AEs), or lost to follow-up. Five veterans stopped treatment prematurely due to AEs, lost to follow-up, or all-cause mortality. Assessment of differences between treated and untreated groups revealed no significant difference in race, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), symptom presence, or chest CT abnormalities. There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality (40% and 22.2% in treated and untreated group, respectively).

To further understand the differences of this cohort, the 13 veterans alive at time of the study were compared with the 6 who had since died of all-cause mortality. No statistically significant differences were found.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports in the literature, veterans in our cohort were predominantly current or former smoking males with underlying COPD and bronchiectasis.1-3,11,12 Chest CT findings varied: Most veterans presented not only with nodules and tree-in-bud opacities, but also a high frequency of fibrosis and emphysema. PFTs revealed a variety of obstruction and restrictive patterns, and most veterans had a reduced DLCO, though it is unclear whether this is reflective of underlying emphysema, fibrosis, or an alternative cardiopulmonary disease.13,14

While underlying structural lung disease may have been a risk factor for MAC-PD in this cohort, the contribution of environmental and domiciliary factors in metropolitan Chicago neighborhoods is unknown. JBVAMC serves an underresourced population who live in the west and south Chicago neighborhoods. Household factors, ambient and indoor air pollution, and potential contamination of the water supply and surface soil may contribute to the prevalence of MAC-PD in this group.15-19 Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.

Recent ATS, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, and IDSA guidelines recommend combination antimycobacterial therapy for patients who meet clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria for the diagnosis of MAC-PD.10 Patients who meet these diagnostic criteria, particularly patients with smear positivity or fibrocavitary disease, should be treated because of risk of unfavorable outcomes.15,20-22 However, we found that the initiation of guideline-recommended antimycobacterial therapy in veterans without HIV with MAC-PD were inconsistent among HCPs. The reasons underlying this phenomenon were not apparent beyond cited reasons for treatment initiation or deference. Despite this inconsistency, there was no clear difference in age, BMI, symptom burden, radiographic abnormality, or all-cause mortality between treatment groups. Existing studies support slow but substantial progression of untreated MAC-PD, and while treatment prevents deterioration of the disease, it does not prevent progression of bronchiectasis.6 The natural history of MAC-PD in this veteran cohort has yet to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, the 50% treatment dropout rate was higher than previously reported rates (11-33%).5 However, the small number of veterans in this study precludes meaningful comparison with similar reports in the literature.

Limitations

The limitations of this small, single-center, retrospective study prevent a robust, generalizable comparison between groups. Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.24-26

Conclusions

These data suggest that clinical, imaging, and treatment attributes of MAC-PD in veterans without HIV who reside in metropolitan Chicago are heterogeneous and are associated with a relatively high mortality rate. Although there was no difference in the attributes or outcomes of veterans who did and did not initiate treatment despite current recommendations, further studies are needed to better explore these relationships.

Nontuberculous Mycobacterium (NTM) is a ubiquitous organism known to cause a variety of infections in susceptible hosts; however, pulmonary infection is the most common. Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is the most prevalent cause of NTM-related pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) and is associated with underlying structural lung disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.1-3

Diagnosis of NTM-PD requires (1) symptoms or radiographic abnormality; and (2) at least 2 sputum cultures positive with the same organism or at least 1 positive culture result on bronchoscopy (wash, lavage, or biopsy).1 Notably, the natural history of untreated NTM-PD varies, though even mild disease may progress substantially.4-6 Progressive disease is more likely to occur in those with a positive smear or more extensive radiographic findings at the initial diagnosis.7 A nationwide Medicare-based study showed that patients with NTM-PD had a higher rate of all-cause mortality than did patients without NTM-PD.8 In a study of 123 patients from Taiwan with MAC-PD, lack of treatment was an independent predictor of mortality.9 Given the risk of progressive morbidity and mortality, recent guidelines recommend initiation of a susceptibility driven, macrolide-based, 3-drug treatment regimen over watchful waiting.10

MAC-PD is increasingly recognized among US veterans.11,12 The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in south/west Chicago serves a large, predominantly Black male population of veterans many of whom are socioeconomically underresourced, and half are aged ≥ 65 years. We observed that initiation of guideline-directed therapy in veterans with MAC-PD at JBVAMC varied among health care professionals (HCPs) in the pulmonary clinic. Therefore, the purpose of this retrospective study was to describe and compare the characteristics of veterans without HIV were diagnosed with MAC-PD and managed at JBVAMC.

Methods

The hospital microbiology department identified veterans diagnosed with NTM at JBVAMC between October 2008 and July 2019. Veterans included in the study were considered to have MAC-PD per American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ISDA) guidelines and those diagnosed with HIV were excluded from analysis. The electronic health record (EHR) was queried for pertinent demographics, smoking history, comorbidities, and symptoms at the time of a positive mycobacterial culture. Computed tomography (CT) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) performed within 1 year of diagnosis were included. PFTs were assessed in accordance with Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, with normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) values defined as ≥ 80% and a normal FEV1/FVC ratio defined as ≥ 70. The diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was assessed per 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS) technical standards and was considered reduced if below the lower limit of normal.13 Information regarding treatment decisions, initiation, and cessation were collected. All-cause mortality was recorded if available in the EHR at the time of data collection.

Statistical analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney U and Fisher exact tests where appropriate. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the JBVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 43 veterans who had a positive culture for MAC; however, only 19 veterans met the diagnostic criteria for MAC-PD and were included in the study (Table). The cohort included predominantly Black and male veterans with a median age of 74 years at time of diagnosis (range, 45-92). Sixteen veterans had underlying lung disease (84.2%), and 16 (84.2%) were current or former smokers. Common comorbidities included COPD, obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and lung cancer. Respiratory symptoms were reported in 17 veterans (89.5%), 15 (78.9%) had a chronic cough, and 10 (52.6%) had dyspnea. Fifteen veterans had a chest CT scan within 1 year of diagnosis: A nodular and tree-in-bud pattern was most commonly found in 13 (86.7%) of veterans. Thirteen veterans had PFTs within 1 year of MAC-PD diagnosis, of whom 6 had a restrictive pattern with percent predicted FVC < 80%, and 9 had evidence of obstruction with FEV1/FVC < 70. DLCO was below the lower limit of normal in 18 veterans. Finally, 6 veterans were deceased at the time of the study.

Of the 19 veterans, guideline-directed, combination antimycobacterial therapy for MAC-PD was initiated in only 10 (52.6%) patients due to presence of symptoms and/or imaging abnormalities. Treatment was deferred due to improved symptoms, concern for adverse events (AEs), or lost to follow-up. Five veterans stopped treatment prematurely due to AEs, lost to follow-up, or all-cause mortality. Assessment of differences between treated and untreated groups revealed no significant difference in race, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), symptom presence, or chest CT abnormalities. There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality (40% and 22.2% in treated and untreated group, respectively).

To further understand the differences of this cohort, the 13 veterans alive at time of the study were compared with the 6 who had since died of all-cause mortality. No statistically significant differences were found.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports in the literature, veterans in our cohort were predominantly current or former smoking males with underlying COPD and bronchiectasis.1-3,11,12 Chest CT findings varied: Most veterans presented not only with nodules and tree-in-bud opacities, but also a high frequency of fibrosis and emphysema. PFTs revealed a variety of obstruction and restrictive patterns, and most veterans had a reduced DLCO, though it is unclear whether this is reflective of underlying emphysema, fibrosis, or an alternative cardiopulmonary disease.13,14

While underlying structural lung disease may have been a risk factor for MAC-PD in this cohort, the contribution of environmental and domiciliary factors in metropolitan Chicago neighborhoods is unknown. JBVAMC serves an underresourced population who live in the west and south Chicago neighborhoods. Household factors, ambient and indoor air pollution, and potential contamination of the water supply and surface soil may contribute to the prevalence of MAC-PD in this group.15-19 Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.

Recent ATS, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, and IDSA guidelines recommend combination antimycobacterial therapy for patients who meet clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria for the diagnosis of MAC-PD.10 Patients who meet these diagnostic criteria, particularly patients with smear positivity or fibrocavitary disease, should be treated because of risk of unfavorable outcomes.15,20-22 However, we found that the initiation of guideline-recommended antimycobacterial therapy in veterans without HIV with MAC-PD were inconsistent among HCPs. The reasons underlying this phenomenon were not apparent beyond cited reasons for treatment initiation or deference. Despite this inconsistency, there was no clear difference in age, BMI, symptom burden, radiographic abnormality, or all-cause mortality between treatment groups. Existing studies support slow but substantial progression of untreated MAC-PD, and while treatment prevents deterioration of the disease, it does not prevent progression of bronchiectasis.6 The natural history of MAC-PD in this veteran cohort has yet to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, the 50% treatment dropout rate was higher than previously reported rates (11-33%).5 However, the small number of veterans in this study precludes meaningful comparison with similar reports in the literature.

Limitations

The limitations of this small, single-center, retrospective study prevent a robust, generalizable comparison between groups. Further studies are warranted to characterize MAC-PD and its treatment in veterans without HIV who reside in underresourced urban communities in the US.24-26

Conclusions

These data suggest that clinical, imaging, and treatment attributes of MAC-PD in veterans without HIV who reside in metropolitan Chicago are heterogeneous and are associated with a relatively high mortality rate. Although there was no difference in the attributes or outcomes of veterans who did and did not initiate treatment despite current recommendations, further studies are needed to better explore these relationships.

1. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/ IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Apr 1;175(7):744-5. Dosage error in article text]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

2. Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):970-976. doi:10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC

3. Winthrop KL, Marras TK, Adjemian J, Zhang H, Wang P, Zhang Q. Incidence and prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in a large U.S. managed care health plan, 2008-2015. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(2):178-185. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-236OC

4. Field SK, Fisher D, Cowie RL. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2004;126(2):566-581. doi:10.1378/chest.126.2.566

5. Kimizuka Y, Hoshino Y, Nishimura T, et al. Retrospective evaluation of natural course in mild cases of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216034. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216034

6. Kotilainen H, Valtonen V, Tukiainen P, Poussa T, Eskola J, Järvinen A. Clinical findings in relation to mortality in nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: patients with Mycobacterium avium complex have better survival than patients with other mycobacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(9):1909-1918. doi:10.1007/s10096-015-2432-8.

7. Hwang JA, Kim S, Jo KW, Shim TS. Natural history of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease in untreated patients with stable course. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1600537. Published 2017 Mar 8. doi:10.1183/13993003.00537-2016

8. Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):881-886. doi:10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC

9. Wang PH, Pan SW, Shu CC, et al. Clinical course and risk factors of mortality in Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease without initial treatment. Respir Med. 2020;171:106070. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106070

10. Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ ERS/ESCMID/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Dec 31;71(11):3023]. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(4):e1-e36. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa241

11. Mirsaeidi M, Hadid W, Ericsoussi B, Rodgers D, Sadikot RT. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease is common in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(11):e1000-e1004. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.03.018

12. Oda G, Winters MA, Pacheco SM, et al. Clusters of nontuberculous mycobacteria linked to water sources at three Veterans Affairs medical centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(3):320-330. doi:10.1017/ice.2019.342

13. Stanojevic S, Graham BL, Cooper BG, et al. Official ERS technical standards: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for the carbon monoxide transfer factor for Caucasians [published correction appears in Eur Respir J. 2020 Oct 15;56(4):]. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700010. Published 2017 Sep 11. doi:10.1183/13993003.00010-2017

14. Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):720-735. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00034905

15. Chalmers JD, Balavoine C, Castellotti PF, et al. European Respiratory Society International Congress, Madrid, 2019: nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease highlights. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00317-2020. Published 2020 Oct 19. doi:10.1183/23120541.00317-2020

16. Hamilton LA, Falkinham JO. Aerosolization of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus from a household ultrasonic humidifier. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67(10):1491-1495. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.000822

17. Hannah CE, Ford BA, Chung J, Ince D, Wanat KA. Characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections at a midwestern tertiary hospital: a retrospective study of 365 patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(6):ofaa173. Published 2020 May 25. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa173

18. Rautiala S, Torvinen E, Torkko P, et al. Potentially pathogenic, slow-growing mycobacteria released into workplace air during the remediation of buildings. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1(1):1-6. doi:10.1080/15459620490250008

19. Tzou CL, Dirac MA, Becker AL, et al. Association between Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease and mycobacteria in home water and soil. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(1):57-62. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-915OC

20. Daley CL, Winthrop KL. Mycobacterium avium complex: addressing gaps in diagnosis and management. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(suppl 4):S199-S211. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa354 21. Kwon BS, Lee JH, Koh Y, et al. The natural history of noncavitary nodular bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Respir Med. 2019;150:45-50. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.007

22. Nasiri MJ, Ebrahimi G, Arefzadeh S, Zamani S, Nikpor Z, Mirsaeidi M. Antibiotic therapy success rate in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020;18(3):263- 273. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1720650

23. Diel R, Lipman M, Hoefsloot W. High mortality in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):206. Published 2018 May 3. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3113-x

24. Marras TK, Prevots DR, Jamieson FB, Winthrop KL; Pulmonary MAC Outcomes Group. Opinions differ by expertise in Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(1):17-22. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-136OC

25. Plotinsky RN, Talbot EA, von Reyn CF. Proposed definitions for epidemiologic and clinical studies of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e77385. Published 2013 Nov 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077385

26. Swenson C, Zerbe CS, Fennelly K. Host variability in NTM disease: implications for research needs. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2901. Published 2018 Dec 3. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02901