User login

Sotatercept Endorsed for PAH by ICER

In a new report, the Midwest Institute for Clinical and Economic Review’s (ICER) Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council concluded that the Merck drug sotatercept, currently under review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has a high certainty of at least a small net health benefit to patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) when added to background therapy. The limited availability of evidence means that the benefit could range from minimal to substantial, according to the authors.

Sotatercept, administered by injection every 3 weeks, is a first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor. It counters cell proliferation and decreases inflammation in vessel walls, which may lead to improved pulmonary blood flow. The US FDA is considering it for approval through a biologics license application, with a decision expected by March 26, 2024.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the long-term benefits of sotatercept. It’s possible that the drug is disease-modifying, but there isn’t yet any proof, according to Greg Curfman, MD, who attended a virtual ICER public meeting on December 1 that summarized the report and accepted public comments. “I’m still wondering the extent to which disease-modifying issue here is more aspirational at this point than really documented,” said Dr. Curfman, who is an associated professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and executive editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Current PAH treatment consists of vasodilators, including phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i), guanylate cyclase stimulators, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA), prostacyclin analogues (prostanoids), and a prostacyclin receptor agonist. The 2022 European Society of Cardiology and the European Respiratory Society clinical practice guideline recommends that low- and intermediate-risk patients should be started on ERA/PDE5i combination therapy, while high-risk patients should also be given an intravenous or subcutaneous prostacyclin analogue, referred to as triple therapy.

Sotatercept’s regulatory approval hinges on the phase 3 STELLAR trial, which included 323 patients with World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) II and III PAH who were randomized to 0.75 mg/kg sotatercept in addition to background double or triple therapy, or background therapy alone. The mean age was 48 years, and the mean time since diagnosis was 8.8 years. About 40% received infused prostacyclin therapy at baseline. At 24 weeks, the median change in 6-min walking distance (6mWD) was 40.8 m longer in the sotatercept group. More patients in the sotatercept group experienced WHO-FC improvement (29.4% vs 13.8%). Those in the sotatercept group also experienced an 84% reduction in risk for clinical worsening or death. PAH-specific quality of life scales did not show a difference between the two groups. Open-label extension trials have shown that benefits are maintained for up to 2 years. Adverse events likely related to sotatercept included telangiectasias, increased hemoglobin levels, and bleeding events.

Along with its benefits, the report authors suggest that the subcutaneous delivery of sotatercept may be less burdensome to patients than some other PAH treatments, especially inhaled and intravenous prostanoids. “However, uncertainty remains about sotatercept’s efficacy in sicker populations and in those with connective tissue disease, and about the durability of effect,” the authors wrote.

A lack of long-term data leaves open the question of its effect on mortality and unknown adverse effects.

Using a de novo decision analytic model, the authors estimated that sotatercept treatment would lead to a longer time without symptoms at rest and more quality-adjusted life years, life years, and equal value life years. They determined the health benefit price benchmark for sotatercept to be between $18,700 and $36,200 per year. “The long-term conventional cost-effectiveness of sotatercept is largely dependent on the long-term effect of sotatercept on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class; however, controlled trial evidence for sotatercept is limited to 24 weeks. Long-term data are necessary to reduce the uncertainty in sotatercept’s long-term effect on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class,” the authors wrote.

During the online meeting, Dr. Curfman took note of the fact that the STELLAR trial reported a median value of increase in 6mWD, rather than a mean, and the 40-m improvement is close to the value accepted as clinically meaningful. “So that tells us that half the patients had less than a clinically important improvement in the six-minute walk distance. We should be putting that in perspective,” said Dr. Curfman.

Another attendee pointed out that the open-label PULSAR extension trial showed that the proportion of patients in the sotatercept arm who were functional class I rose from 7.5% at the end of the trial to 20.6% at the end of the open-label period and wondered if that could be a sign of disease-modifying activity. “I think that’s a remarkable piece of data. I don’t recall seeing that in any other open label [trial of a PAH therapy] — that much of an improvement in getting to our best functional status,” said Marc Simon, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Pulmonary Hypertension Center at the University of California, San Francisco, who was a coauthor of the report.

Dr. Curfman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Simon has consulted for Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new report, the Midwest Institute for Clinical and Economic Review’s (ICER) Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council concluded that the Merck drug sotatercept, currently under review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has a high certainty of at least a small net health benefit to patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) when added to background therapy. The limited availability of evidence means that the benefit could range from minimal to substantial, according to the authors.

Sotatercept, administered by injection every 3 weeks, is a first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor. It counters cell proliferation and decreases inflammation in vessel walls, which may lead to improved pulmonary blood flow. The US FDA is considering it for approval through a biologics license application, with a decision expected by March 26, 2024.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the long-term benefits of sotatercept. It’s possible that the drug is disease-modifying, but there isn’t yet any proof, according to Greg Curfman, MD, who attended a virtual ICER public meeting on December 1 that summarized the report and accepted public comments. “I’m still wondering the extent to which disease-modifying issue here is more aspirational at this point than really documented,” said Dr. Curfman, who is an associated professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and executive editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Current PAH treatment consists of vasodilators, including phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i), guanylate cyclase stimulators, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA), prostacyclin analogues (prostanoids), and a prostacyclin receptor agonist. The 2022 European Society of Cardiology and the European Respiratory Society clinical practice guideline recommends that low- and intermediate-risk patients should be started on ERA/PDE5i combination therapy, while high-risk patients should also be given an intravenous or subcutaneous prostacyclin analogue, referred to as triple therapy.

Sotatercept’s regulatory approval hinges on the phase 3 STELLAR trial, which included 323 patients with World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) II and III PAH who were randomized to 0.75 mg/kg sotatercept in addition to background double or triple therapy, or background therapy alone. The mean age was 48 years, and the mean time since diagnosis was 8.8 years. About 40% received infused prostacyclin therapy at baseline. At 24 weeks, the median change in 6-min walking distance (6mWD) was 40.8 m longer in the sotatercept group. More patients in the sotatercept group experienced WHO-FC improvement (29.4% vs 13.8%). Those in the sotatercept group also experienced an 84% reduction in risk for clinical worsening or death. PAH-specific quality of life scales did not show a difference between the two groups. Open-label extension trials have shown that benefits are maintained for up to 2 years. Adverse events likely related to sotatercept included telangiectasias, increased hemoglobin levels, and bleeding events.

Along with its benefits, the report authors suggest that the subcutaneous delivery of sotatercept may be less burdensome to patients than some other PAH treatments, especially inhaled and intravenous prostanoids. “However, uncertainty remains about sotatercept’s efficacy in sicker populations and in those with connective tissue disease, and about the durability of effect,” the authors wrote.

A lack of long-term data leaves open the question of its effect on mortality and unknown adverse effects.

Using a de novo decision analytic model, the authors estimated that sotatercept treatment would lead to a longer time without symptoms at rest and more quality-adjusted life years, life years, and equal value life years. They determined the health benefit price benchmark for sotatercept to be between $18,700 and $36,200 per year. “The long-term conventional cost-effectiveness of sotatercept is largely dependent on the long-term effect of sotatercept on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class; however, controlled trial evidence for sotatercept is limited to 24 weeks. Long-term data are necessary to reduce the uncertainty in sotatercept’s long-term effect on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class,” the authors wrote.

During the online meeting, Dr. Curfman took note of the fact that the STELLAR trial reported a median value of increase in 6mWD, rather than a mean, and the 40-m improvement is close to the value accepted as clinically meaningful. “So that tells us that half the patients had less than a clinically important improvement in the six-minute walk distance. We should be putting that in perspective,” said Dr. Curfman.

Another attendee pointed out that the open-label PULSAR extension trial showed that the proportion of patients in the sotatercept arm who were functional class I rose from 7.5% at the end of the trial to 20.6% at the end of the open-label period and wondered if that could be a sign of disease-modifying activity. “I think that’s a remarkable piece of data. I don’t recall seeing that in any other open label [trial of a PAH therapy] — that much of an improvement in getting to our best functional status,” said Marc Simon, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Pulmonary Hypertension Center at the University of California, San Francisco, who was a coauthor of the report.

Dr. Curfman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Simon has consulted for Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new report, the Midwest Institute for Clinical and Economic Review’s (ICER) Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council concluded that the Merck drug sotatercept, currently under review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has a high certainty of at least a small net health benefit to patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) when added to background therapy. The limited availability of evidence means that the benefit could range from minimal to substantial, according to the authors.

Sotatercept, administered by injection every 3 weeks, is a first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor. It counters cell proliferation and decreases inflammation in vessel walls, which may lead to improved pulmonary blood flow. The US FDA is considering it for approval through a biologics license application, with a decision expected by March 26, 2024.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the long-term benefits of sotatercept. It’s possible that the drug is disease-modifying, but there isn’t yet any proof, according to Greg Curfman, MD, who attended a virtual ICER public meeting on December 1 that summarized the report and accepted public comments. “I’m still wondering the extent to which disease-modifying issue here is more aspirational at this point than really documented,” said Dr. Curfman, who is an associated professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and executive editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Current PAH treatment consists of vasodilators, including phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i), guanylate cyclase stimulators, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA), prostacyclin analogues (prostanoids), and a prostacyclin receptor agonist. The 2022 European Society of Cardiology and the European Respiratory Society clinical practice guideline recommends that low- and intermediate-risk patients should be started on ERA/PDE5i combination therapy, while high-risk patients should also be given an intravenous or subcutaneous prostacyclin analogue, referred to as triple therapy.

Sotatercept’s regulatory approval hinges on the phase 3 STELLAR trial, which included 323 patients with World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) II and III PAH who were randomized to 0.75 mg/kg sotatercept in addition to background double or triple therapy, or background therapy alone. The mean age was 48 years, and the mean time since diagnosis was 8.8 years. About 40% received infused prostacyclin therapy at baseline. At 24 weeks, the median change in 6-min walking distance (6mWD) was 40.8 m longer in the sotatercept group. More patients in the sotatercept group experienced WHO-FC improvement (29.4% vs 13.8%). Those in the sotatercept group also experienced an 84% reduction in risk for clinical worsening or death. PAH-specific quality of life scales did not show a difference between the two groups. Open-label extension trials have shown that benefits are maintained for up to 2 years. Adverse events likely related to sotatercept included telangiectasias, increased hemoglobin levels, and bleeding events.

Along with its benefits, the report authors suggest that the subcutaneous delivery of sotatercept may be less burdensome to patients than some other PAH treatments, especially inhaled and intravenous prostanoids. “However, uncertainty remains about sotatercept’s efficacy in sicker populations and in those with connective tissue disease, and about the durability of effect,” the authors wrote.

A lack of long-term data leaves open the question of its effect on mortality and unknown adverse effects.

Using a de novo decision analytic model, the authors estimated that sotatercept treatment would lead to a longer time without symptoms at rest and more quality-adjusted life years, life years, and equal value life years. They determined the health benefit price benchmark for sotatercept to be between $18,700 and $36,200 per year. “The long-term conventional cost-effectiveness of sotatercept is largely dependent on the long-term effect of sotatercept on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class; however, controlled trial evidence for sotatercept is limited to 24 weeks. Long-term data are necessary to reduce the uncertainty in sotatercept’s long-term effect on improving functional class and slowing the worsening in functional class,” the authors wrote.

During the online meeting, Dr. Curfman took note of the fact that the STELLAR trial reported a median value of increase in 6mWD, rather than a mean, and the 40-m improvement is close to the value accepted as clinically meaningful. “So that tells us that half the patients had less than a clinically important improvement in the six-minute walk distance. We should be putting that in perspective,” said Dr. Curfman.

Another attendee pointed out that the open-label PULSAR extension trial showed that the proportion of patients in the sotatercept arm who were functional class I rose from 7.5% at the end of the trial to 20.6% at the end of the open-label period and wondered if that could be a sign of disease-modifying activity. “I think that’s a remarkable piece of data. I don’t recall seeing that in any other open label [trial of a PAH therapy] — that much of an improvement in getting to our best functional status,” said Marc Simon, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Pulmonary Hypertension Center at the University of California, San Francisco, who was a coauthor of the report.

Dr. Curfman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Simon has consulted for Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New COVID variant JN.1 could disrupt holiday plans

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

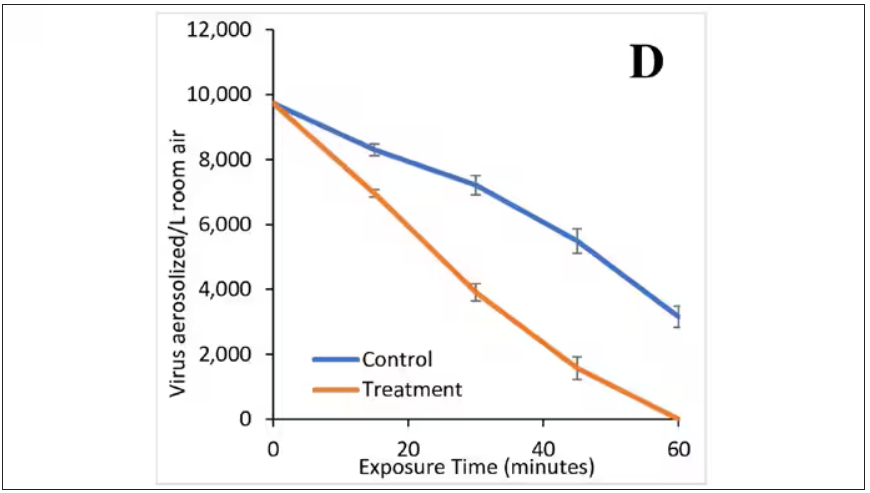

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Promising results for investigational agents and catheter-based denervation

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

FROM AHA 2023

Smoking alters salivary microbiota in potential path to disease risk

TOPLINE:

Salivary microbiota changes caused by cigarette smoking may affect metabolic pathways and increase disease risk.

METHODOLOGY:

The researchers analyzed health information and data on the composition of salivary microbiota from 1601 adult participants in the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) microbiome study (CHRISMB); CHRIS is an ongoing study in Italy.

The average age of the study population was 45 years; 53% were female, and 45% were current or former smokers.

The researchers hypothesized that changes in salivary microbial composition would be associated with smoking, with more nitrate-reducing bacteria present, and that nitrate reduction pathways would be reduced in smokers.

TAKEAWAY:

The researchers identified 44 genera that differed in the salivary microbiota of current smokers and nonsmokers. In smokers, seven genera in the phylum Proteobacteria were decreased and six in the phylum Actinobacteria were increased compared with nonsmokers; these phyla contain primarily aerobic and anaerobic taxa, respectively.

Some microbiota changes were significantly associated with daily smoking intensity; genera from the classes Betaproteobacteria (Lautropia or Neisseria), Gammaproteobacteria (Cardiobacterium), and Flavobacteriia (Capnocytophaga) decreased significantly with increased grams of tobacco smoked per day, measured in 5-g increments.

Smoking was associated with changes in the salivary microbiota; the nitrate reduction pathway was significantly lower in smokers compared with nonsmokers, and these decreases were consistent with previous studies of decreased cardiovascular events in former smokers.

However, the salivary microbiota of smokers who had quit for at least 5 years resembled that of individuals who had never smoked.

IN PRACTICE:

“Decreased microbial nitrate reduction pathway abundance in smokers may provide an additional explanation for the effect of smoking on cardiovascular and periodontal diseases risk, a hypothesis which should be tested in future studies,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Giacomo Antonello, MD, of Eurac Research, Affiliated Institute of the University of Lübeck, Bolzano, Italy. The study was published online in Scientific Reports (a Nature journal) on November 2, 2023.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design and lack of professional assessment of tooth and gum health were limiting factors, as were potential confounding factors including medication use, diet, and alcohol intake.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol and by the European Regional Development Fund. The CHRISMB microbiota data generation was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Salivary microbiota changes caused by cigarette smoking may affect metabolic pathways and increase disease risk.

METHODOLOGY:

The researchers analyzed health information and data on the composition of salivary microbiota from 1601 adult participants in the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) microbiome study (CHRISMB); CHRIS is an ongoing study in Italy.

The average age of the study population was 45 years; 53% were female, and 45% were current or former smokers.

The researchers hypothesized that changes in salivary microbial composition would be associated with smoking, with more nitrate-reducing bacteria present, and that nitrate reduction pathways would be reduced in smokers.

TAKEAWAY:

The researchers identified 44 genera that differed in the salivary microbiota of current smokers and nonsmokers. In smokers, seven genera in the phylum Proteobacteria were decreased and six in the phylum Actinobacteria were increased compared with nonsmokers; these phyla contain primarily aerobic and anaerobic taxa, respectively.

Some microbiota changes were significantly associated with daily smoking intensity; genera from the classes Betaproteobacteria (Lautropia or Neisseria), Gammaproteobacteria (Cardiobacterium), and Flavobacteriia (Capnocytophaga) decreased significantly with increased grams of tobacco smoked per day, measured in 5-g increments.

Smoking was associated with changes in the salivary microbiota; the nitrate reduction pathway was significantly lower in smokers compared with nonsmokers, and these decreases were consistent with previous studies of decreased cardiovascular events in former smokers.

However, the salivary microbiota of smokers who had quit for at least 5 years resembled that of individuals who had never smoked.

IN PRACTICE:

“Decreased microbial nitrate reduction pathway abundance in smokers may provide an additional explanation for the effect of smoking on cardiovascular and periodontal diseases risk, a hypothesis which should be tested in future studies,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Giacomo Antonello, MD, of Eurac Research, Affiliated Institute of the University of Lübeck, Bolzano, Italy. The study was published online in Scientific Reports (a Nature journal) on November 2, 2023.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design and lack of professional assessment of tooth and gum health were limiting factors, as were potential confounding factors including medication use, diet, and alcohol intake.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol and by the European Regional Development Fund. The CHRISMB microbiota data generation was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Salivary microbiota changes caused by cigarette smoking may affect metabolic pathways and increase disease risk.

METHODOLOGY:

The researchers analyzed health information and data on the composition of salivary microbiota from 1601 adult participants in the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) microbiome study (CHRISMB); CHRIS is an ongoing study in Italy.

The average age of the study population was 45 years; 53% were female, and 45% were current or former smokers.

The researchers hypothesized that changes in salivary microbial composition would be associated with smoking, with more nitrate-reducing bacteria present, and that nitrate reduction pathways would be reduced in smokers.

TAKEAWAY:

The researchers identified 44 genera that differed in the salivary microbiota of current smokers and nonsmokers. In smokers, seven genera in the phylum Proteobacteria were decreased and six in the phylum Actinobacteria were increased compared with nonsmokers; these phyla contain primarily aerobic and anaerobic taxa, respectively.

Some microbiota changes were significantly associated with daily smoking intensity; genera from the classes Betaproteobacteria (Lautropia or Neisseria), Gammaproteobacteria (Cardiobacterium), and Flavobacteriia (Capnocytophaga) decreased significantly with increased grams of tobacco smoked per day, measured in 5-g increments.

Smoking was associated with changes in the salivary microbiota; the nitrate reduction pathway was significantly lower in smokers compared with nonsmokers, and these decreases were consistent with previous studies of decreased cardiovascular events in former smokers.

However, the salivary microbiota of smokers who had quit for at least 5 years resembled that of individuals who had never smoked.

IN PRACTICE:

“Decreased microbial nitrate reduction pathway abundance in smokers may provide an additional explanation for the effect of smoking on cardiovascular and periodontal diseases risk, a hypothesis which should be tested in future studies,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Giacomo Antonello, MD, of Eurac Research, Affiliated Institute of the University of Lübeck, Bolzano, Italy. The study was published online in Scientific Reports (a Nature journal) on November 2, 2023.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design and lack of professional assessment of tooth and gum health were limiting factors, as were potential confounding factors including medication use, diet, and alcohol intake.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol and by the European Regional Development Fund. The CHRISMB microbiota data generation was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Discontinuation Schedule of Inhaled Corticosteroids in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are frequently prescribed for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to reduce exacerbations in a specific subset of patients. The long-term use of ICSs, however, is associated with several potential systemic adverse effects, including adrenal suppression, decreased bone mineral density, and immunosuppression.1 The concern for immunosuppression is particularly notable and leads to a known increased risk for developing pneumonia in patients with COPD. These patients frequently have other concurrent risk factors for pneumonia (eg, history of tobacco use, older age, and severe airway limitations) and are at higher risk for more severe outcomes in the setting of pneumonia.2,3

Primarily due to the concern of pneumonia risks, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines have recommended ICS discontinuation in patients who are less likely to receive significant benefits from therapy.4 Likely due to an anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, ICSs have been shown to reduce COPD exacerbation rates in patients with comorbid asthma or who have evidence of a strong inflammatory component to their COPD. The strongest indicator of an inflammatory component is an elevated blood eosinophil (EOS) count; those with EOS > 300 cells/µL are most likely to benefit from ICSs, whereas those with a count < 100 cells/µL are unlikely to have a significant response. In addition to the inflammatory component consideration, prior studies have shown improvements in lung function and reduction of exacerbations with ICS use in patients with frequent moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbations.5 Although the GOLD guidelines provide recommendations about who is appropriate to discontinue ICS use, clinicians have no clear guidance on the risks or the best discontinuation strategy.

Based primarily on data from a prior randomized controlled trial, the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 17, which includes the Veterans Affairs North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) in Dallas, established a recommended ICS de-escalation strategy.6,7 The strategy included a 12-week stepwise taper using a mometasone inhaler for all patients discontinuing a moderate or high dose ICS. The lack of substantial clinical trial data or expert consensus guideline recommendations has left open the question of whether a taper is necessary. To answer that question, this study was conducted to evaluate whether there is a difference in the rate of COPD exacerbations following abrupt discontinuation vs gradual taper of ICS therapy.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective cohort study was conducted at VANTHCS. Patient electronic health records between January 10, 2021, and September 1, 2021, were reviewed for the last documented fill date of any inhaler containing a steroid component. This time frame was chosen to coincide with a VANTHCS initiative to follow GOLD guidelines for ICS discontinuation. Patients were followed for outcomes until November 1, 2022.

To be included in this study, patients had to have active prescriptions at VANTHCS, have a documented diagnosis of COPD in their chart, and be prescribed a stable dose of ICS for ≥ 1 year prior to their latest refill. The inhaler used could contain an ICS as monotherapy, in combination with a long-acting β-agonist (LABA), or as part of triple therapy with an additional long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA). The inhaler needed to be discontinued during the study period of interest.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of asthma, were aged < 40 years, had active prescriptions for multiple ICS inhalers or nebulizers, or had significant oral steroid use (≥ 5 mg/d prednisone or an equivalent steroid for > 6 weeks) within 1 year of their ICS discontinuation date. In addition, to reduce the risk of future events being misclassified as COPD exacerbations, patients were excluded if they had a congestive heart failure exacerbation up to 2 years before ICS discontinuation or a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection up to 1 year before or 6 months after ICS discontinuation. Patients with a COPD exacerbation requiring an emergency department or hospital visit within 2 years prior to ICS discontinuation were also excluded, as de-escalation of ICS therapy was likely inappropriate in these cases. Finally, patients were excluded if they were started on a different ICS immediately following the discontinuation of their first ICS.

The primary outcome for this study was COPD exacerbations requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization within 6 months of ICS discontinuation. A secondary outcome examining the rates of COPD exacerbations within 12 months also was used. The original study design called for the use of inferential statistics to compare the rates of primary and secondary outcomes in patients whose ICS was abruptly discontinued with those who were tapered slowly. After data collection, however, the small sample size and low event rate meant that the planned statistical tests were no longer appropriate. Instead, we decided to analyze the planned outcomes using descriptive statistics and look at an additional number of post hoc outcomes to provide deeper insight into clinical practice. We examined the association between relevant demographic factors, such as age, comorbidity burden, ICS potency, duration of ICS therapy, and EOS count and the clinician decision whether to taper the ICS. These same factors were also evaluated for potential association with the increased risk of COPD exacerbations following ICS discontinuation.

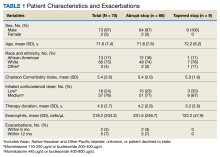

Results

A total of 75 patients were included. Most patients were White race and male with a mean (SD) age of 71.6 (7.4) years. Charlson Comorbidity Index scores were calculated for all included patients with a mean (SD) score of 5.4 (2.0). Of note, scores > 5 are considered a severe comorbidity burden and have an estimated mean 10-year survival rate < 21%. The overwhelming majority of patients were receiving budesonide/formoterol as their ICS inhaler with 1 receiving mometasone monotherapy. When evaluating the steroid dose, 18 (24%) patients received a low dose ICS (200-400 µg of budesonide or 110-220 µg of mometasone), while 57 (76%) received a medium dose (400-800 µg of budesonide or 440 µg of mometasone). No patients received a high ICS dose. The mean (SD) duration of therapy before discontinuation was 4.0 (2.7) years (Table 1).

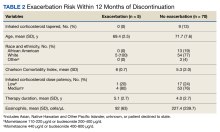

Nine (12%) patients had their ICS slowly tapered, while therapy was abruptly discontinued in the other 66 (88%) patients. A variety of taper types were used (Figure) without a strong preference for a particular dosing strategy. The primary outcome of COPD exacerbation requiring emergency department visit or hospitalization within 6 months occurred in 2 patients. When the time frame was extended to 12 months for the secondary outcome, an additional 3 patients experienced an event. The mean time to event was 172 days following ICS discontinuation. All the events occurred in patients whose ICS was discontinued without any type of taper.

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the relationship between specific variables and the clinician choice whether to taper an ICS. There was no discernable impact of age, race and ethnicity, comorbidity score, or ICS dose on whether an ICS was tapered. We observed a slight association between shorter duration of therapy and lower EOS count and use of a taper. When evaluating the relationship between these same factors and exacerbation occurrence, we saw comparable trends (Table 2). Patients with an exacerbation had a slightly longer mean duration of ICS therapy and lower mean EOS count.

Discussion

Despite facility guidance recommending tapering of therapy when discontinuing a moderate- or high-dose ICS, most patients in this study discontinued the ICS abruptly. The clinician may have been concerned with patients being able to adhere to a taper regimen, skeptical of the actual need to taper, or unaware of the VANTHCS recommendations for a specific taper method. Shared decision making with patients may have also played a role in prescribing patterns. Currently, there is not sufficient data to support the use of any one particular type of taper over another, which accounts for the variability seen in practice.

The decision to taper ICSs did not seem to be strongly associated with any specific demographic factor, although the ability to examine the impact of factors (eg, race and ethnicity) was limited due to the largely homogenous population. One may have expected a taper to be more common in older patients or in those with more comorbidities; however, this was not observed in this study. The only discernible trends seen were a lower frequency of tapering in patients who had a shorter duration of ICS therapy and those with lower EOS counts. These patients were at lower risk of repeat COPD exacerbations compared with those with longer ICS therapy duration and higher EOS counts; therefore, this finding was unexpected. This suggests that patient-specific factors may not be the primary driving force in the ICS tapering decision; instead it may be based on general clinician preferences or shared decision making with individual patients.

Overall, we noted very low rates of COPD exacerbations. As ICS discontinuation was occurring in stable patients without any recent exacerbations, lower rates of future exacerbations were expected compared with the population of patients with COPD as a whole. This suggests that ICS therapy can be safely stopped in stable patients with COPD who are not likely to receive significant benefits as defined in the GOLD guidelines. All of the exacerbations that occurred were in patients whose ICS was abruptly discontinued; however, given the small number of patients who had a taper, it is difficult to draw conclusions. The low overall rate of exacerbations suggests that a taper may not be necessary to ensure safety while stopping a low- or moderate-intensity ICS.

Several randomized controlled trials have attempted to evaluate the need for an ICS taper; however, results remain mixed. The COSMIC study showed a decline in lung function following ICS discontinuation in patients with ≥ 2 COPD exacerbations in the previous year.8 Similar results were seen in the SUNSET study with increased exacerbation rates after ICS discontinuation in patients with elevated EOS counts.9 However, these studies included patients for whom ICS discontinuation is currently not recommended. Alternatively, the INSTEAD trial looked at patients without frequent recent exacerbations and found no difference in lung function, exacerbation rates, or rescue inhaler use in patients that continued combination ICS plus bronchodilator use vs those de-escalated to bronchodilator monotherapy.10

All 3 studies chose to abruptly stop the ICS when discontinuing therapy; however, using a slow, stepwise taper similar to that used after long periods of oral steroid use may reduce the risk of worsening exacerbations. The WISDOM trial is the only major randomized trial to date that stopped ICS therapy using a stepwise withdrawal of therapy.7 In patients who were continued on triple inhaled therapy (2 bronchodilators plus ICS) vs those who were de-escalated to dual bronchodilator therapy, de-escalation was noninferior to continuation of therapy in time to first COPD exacerbation. Both the WISDOM and INSTEAD trials were consistent with the results found in our real-world retrospective evaluation.

There did not seem to be an increased exacerbation risk following ICS discontinuation in any patient subpopulation based on sex, age, race and ethnicity, or comorbidity burden. We noted a trend toward more exacerbations in patients with a longer duration of ICS therapy, suggesting that additional caution may be needed when stopping ICS therapy for these patients. We also noted a trend toward more exacerbations in patients with a lower mean EOS count; however, given the low event rate and wide variability in observed patient EOS counts, this is likely a spurious finding.

Limitations

The small sample size, resulting from the strict exclusion criteria, limits the generalizability of the results. Although the low number of events seen in this study supports safety in ICS discontinuation, there may have been higher rates observed in a larger population. The most common reason for patient exclusion was the initiation of another ICS immediately following discontinuation of the original ICS. During the study period, VANTHCS underwent a change to its formulary: Fluticasone/salmeterol replaced budesonide/formoterol as the preferred ICS/LABA combination. As a result, many patients had their budesonide/formoterol discontinued during the study period solely to initiate fluticasone/salmeterol therapy. As these patients did not truly have their ICS discontinued or have a significant period without ICS therapy, they were not included in the results, and the total patient population available to analyze was relatively limited.

The low event rate also limits the ability to compare various factors influencing exacerbation risk, particularly taper vs abrupt ICS discontinuation. This is further compounded by the small number of patients who had a taper performed and the lack of consistency in the method of tapering used. Statistical significance could not be determined for any outcome, and all findings were purely hypothesis generating. Finally, data were only collected for moderate or severe COPD exacerbations that resulted in an emergency department visit or hospitalization, so there may have been mild exacerbations treated in the outpatient setting that were not captured.

Despite these limitations, this study adds data to an area of COPD management that currently lacks strong clinical guidance. Since investigators had access to clinician notes, we were able to capture ICS tapers even if patients did not receive a prescription with specific taper instructions. The extended follow-up period of 12 months evaluated a longer potential time to impact of ICS discontinuation than is done in most COPD clinical trials.

Conclusions

Overall, very low rates of COPD exacerbations occurred following ICS discontinuation, regardless of whether a taper

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7(7):CD002991. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002991.pub3

2. Crim C, Dransfield MT, Bourbeau J, et al. Pneumonia risk with inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol compared with vilanterol alone in patients with COPD. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(1):27-34. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-413OC

3. Crim C, Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, et al. Pneumonia risk with inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol in COPD patients with moderate airflow limitation: The SUMMIT trial. Respir Med. 2017;131:27-34. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.060

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2023 Report). Accessed November 3, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf