User login

U.S. cancer centers embroiled in Chinese research thefts

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician groups push back on Medicaid block grant plan

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

A Comparison of 4 Single-Question Measures of Patient Satisfaction

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures

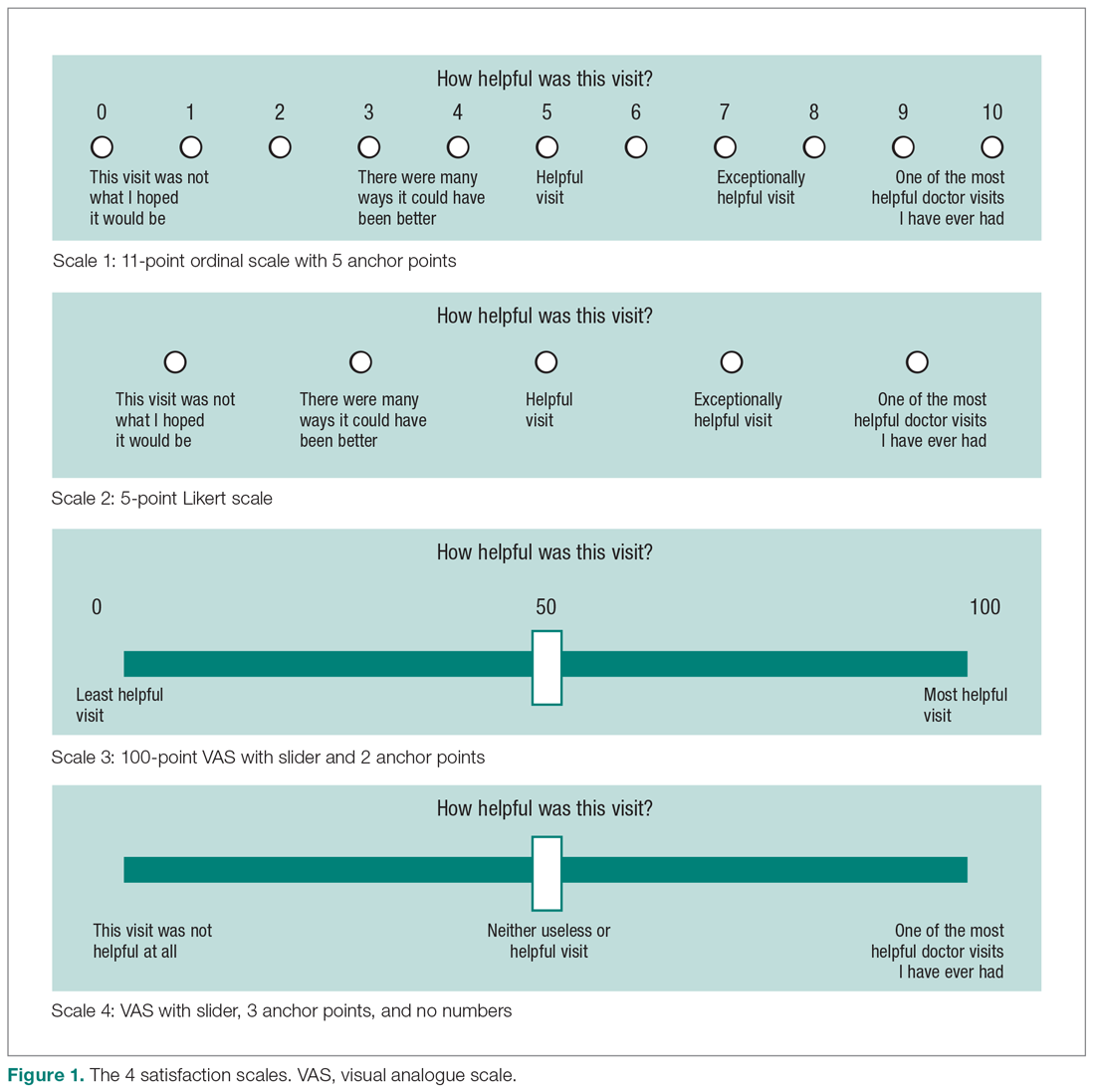

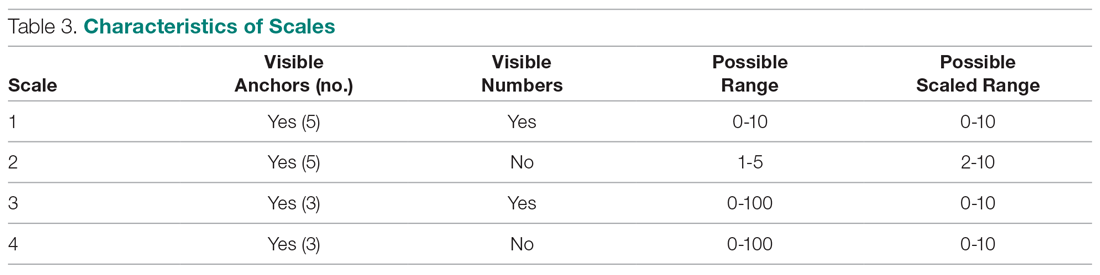

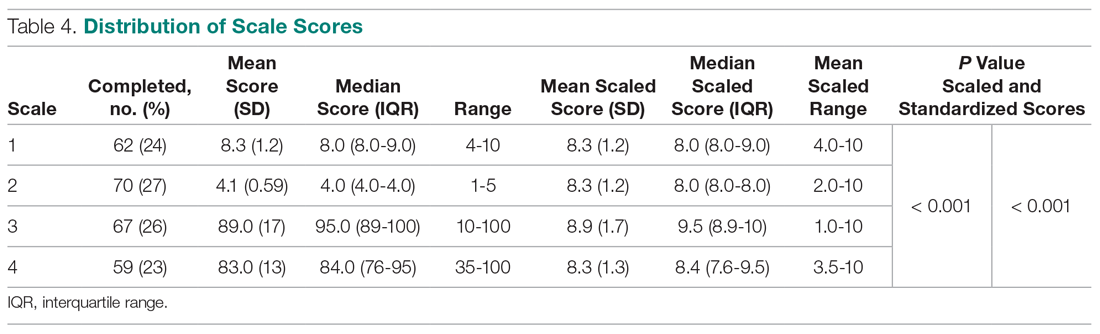

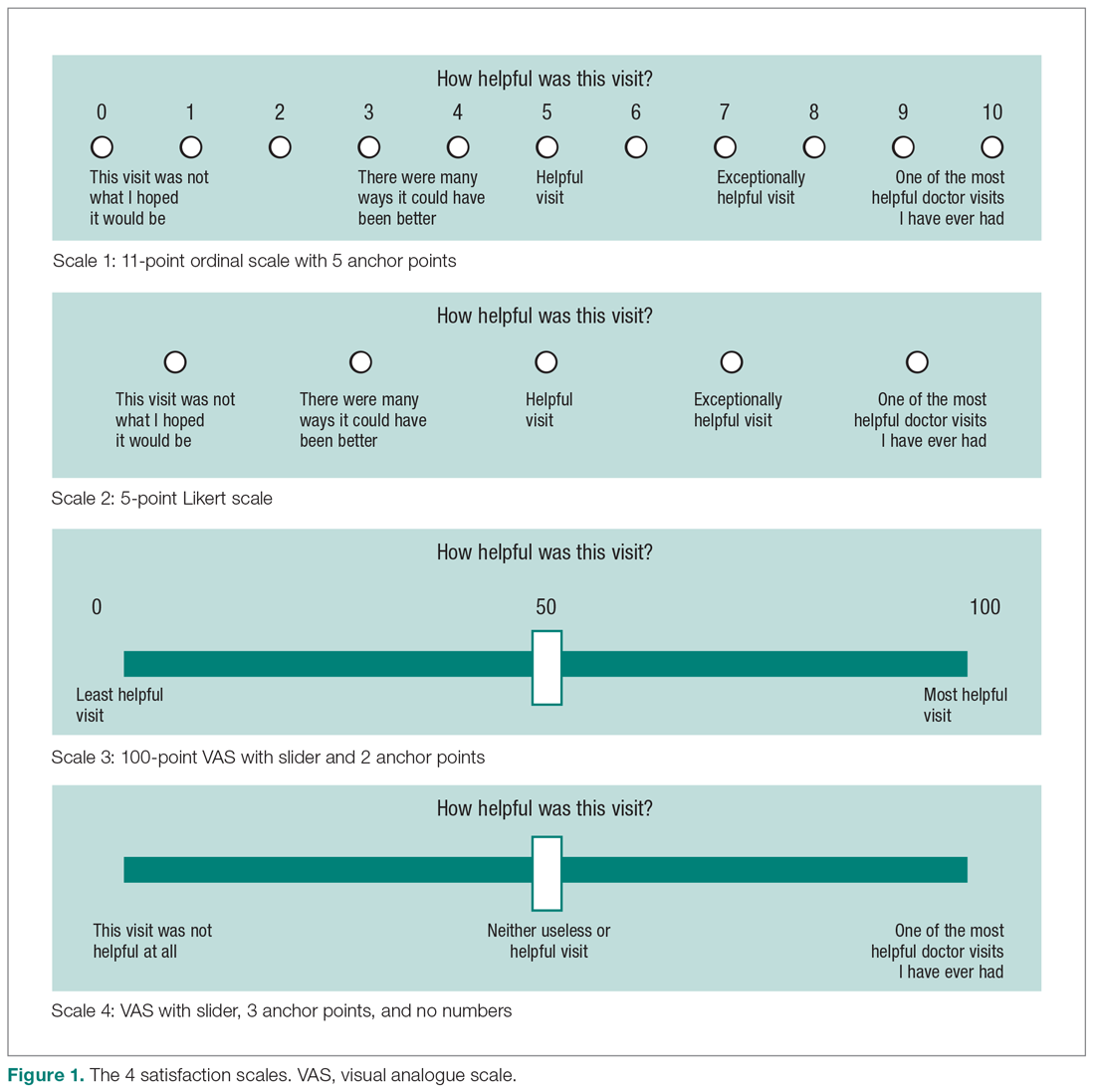

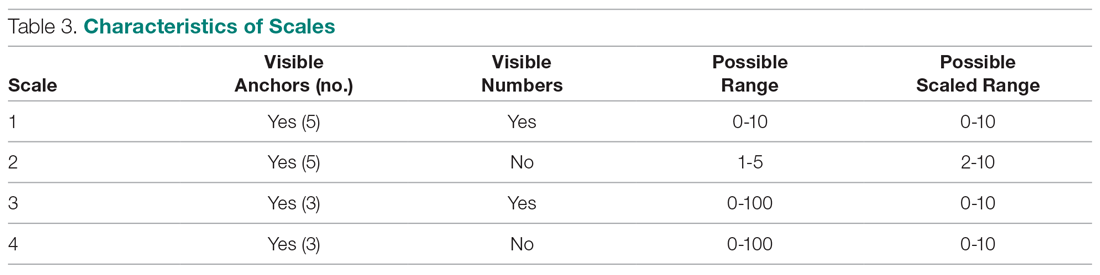

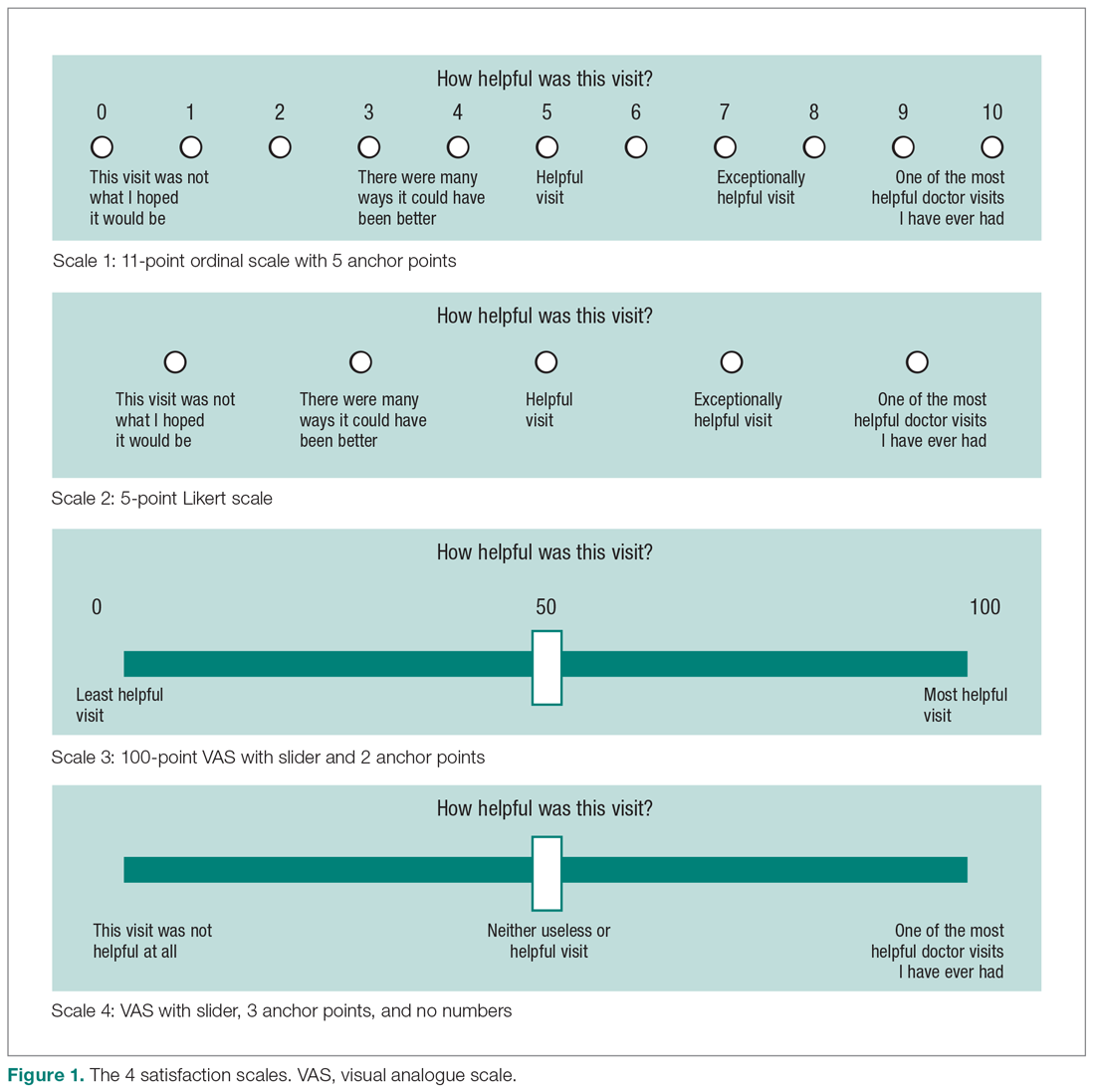

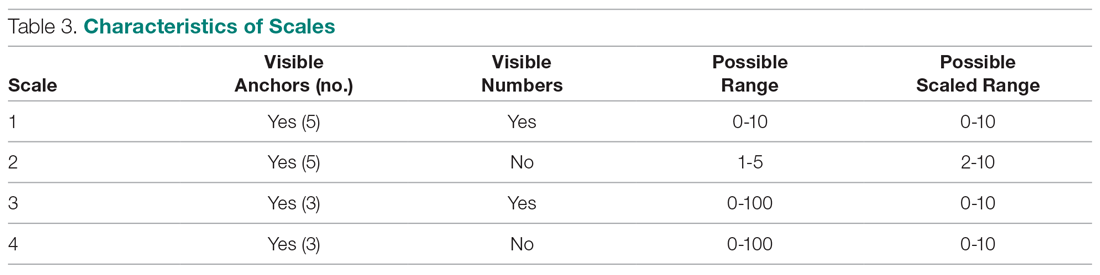

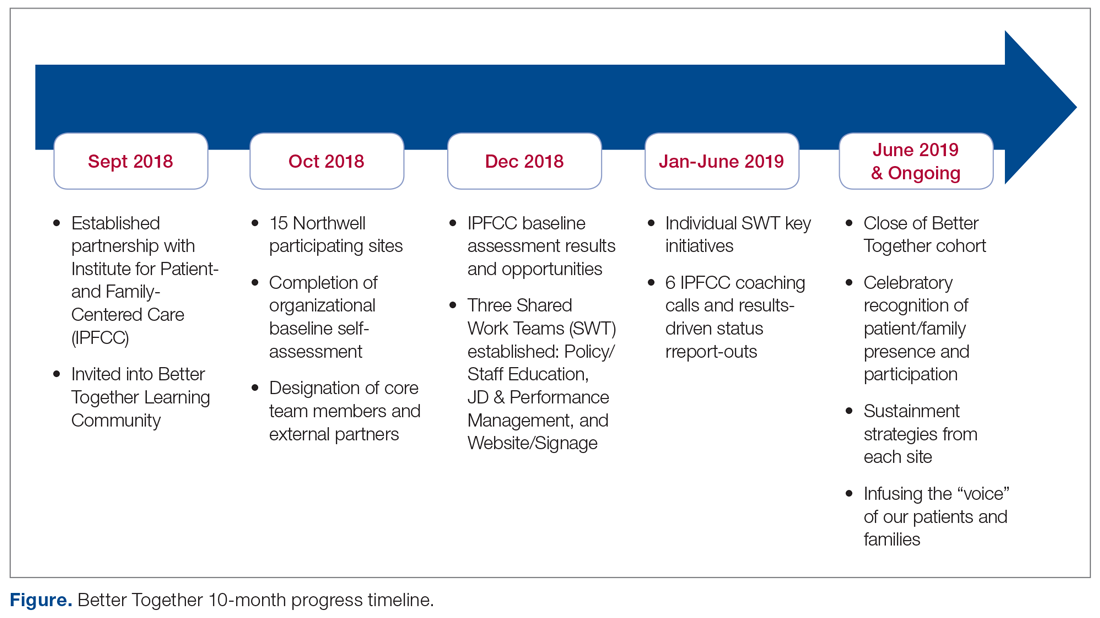

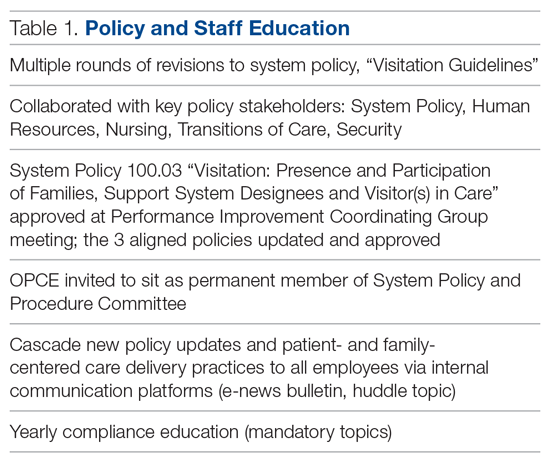

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, work status, insurance status, comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2) a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ in time needed to complete them; however, we did not explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also completed measures of psychological aspects of illness. The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping strategy for pain.8 Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health anxiety.9 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to measure symptoms of depression.10 Finally, the diagnosis was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satisfaction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to compare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects are present when patients select the lowest value in a similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an independent variable no longer influences the dependent variable being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, having a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents more peaked distribution.11,12 If skewness is 0 and kurtosis is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promoters (people who scored 9 or 10).13 NPS are widely used in the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale, with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

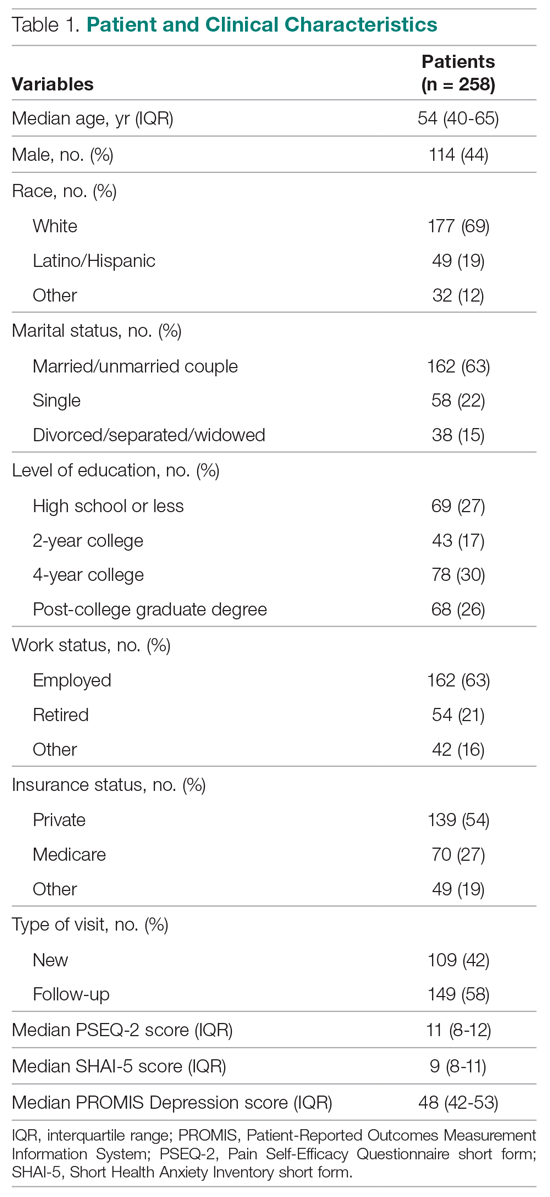

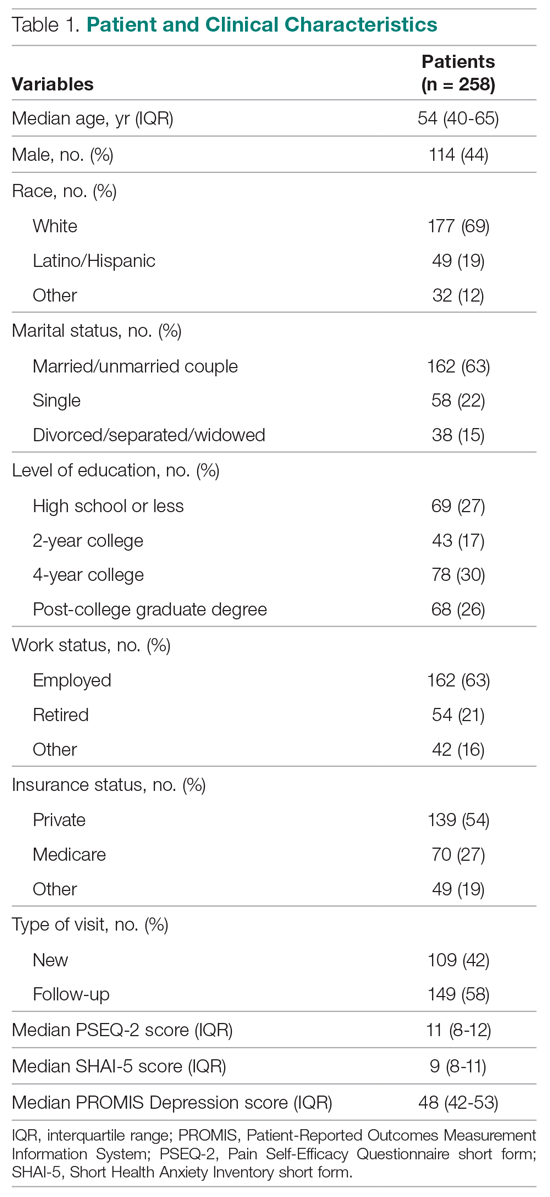

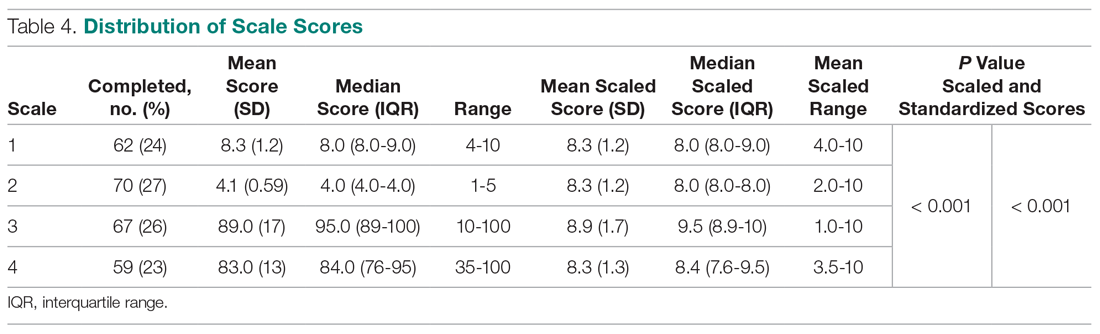

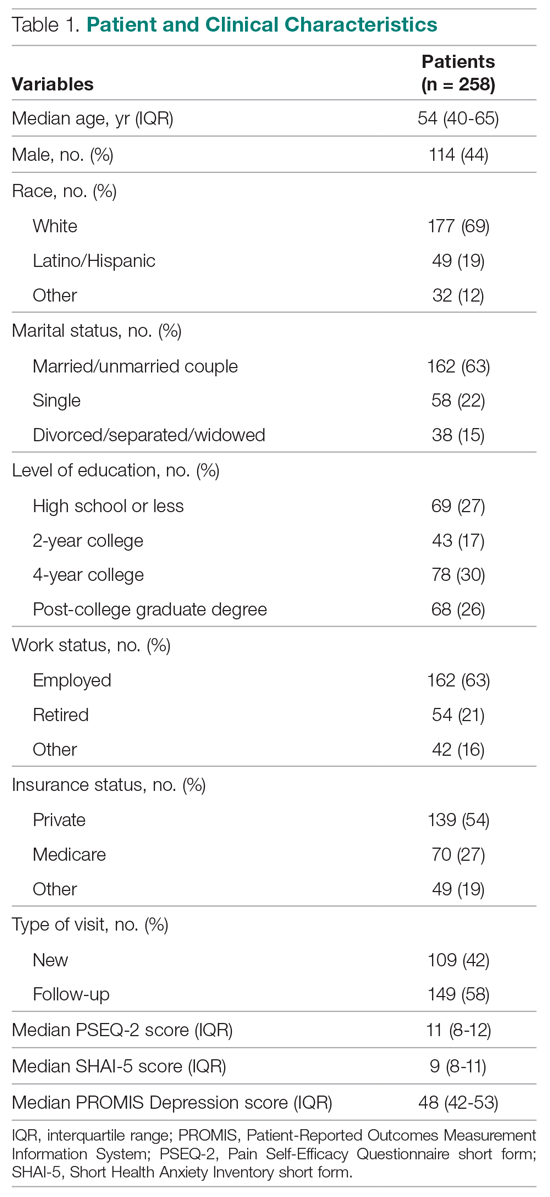

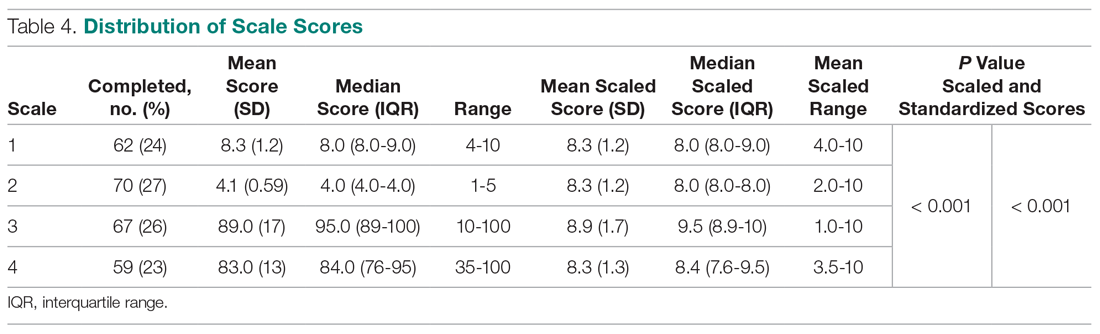

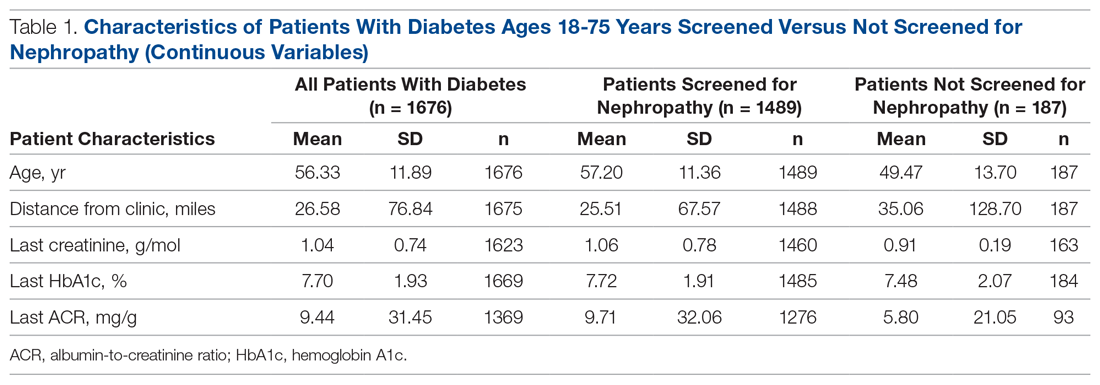

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed, and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled. The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65 years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%), and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

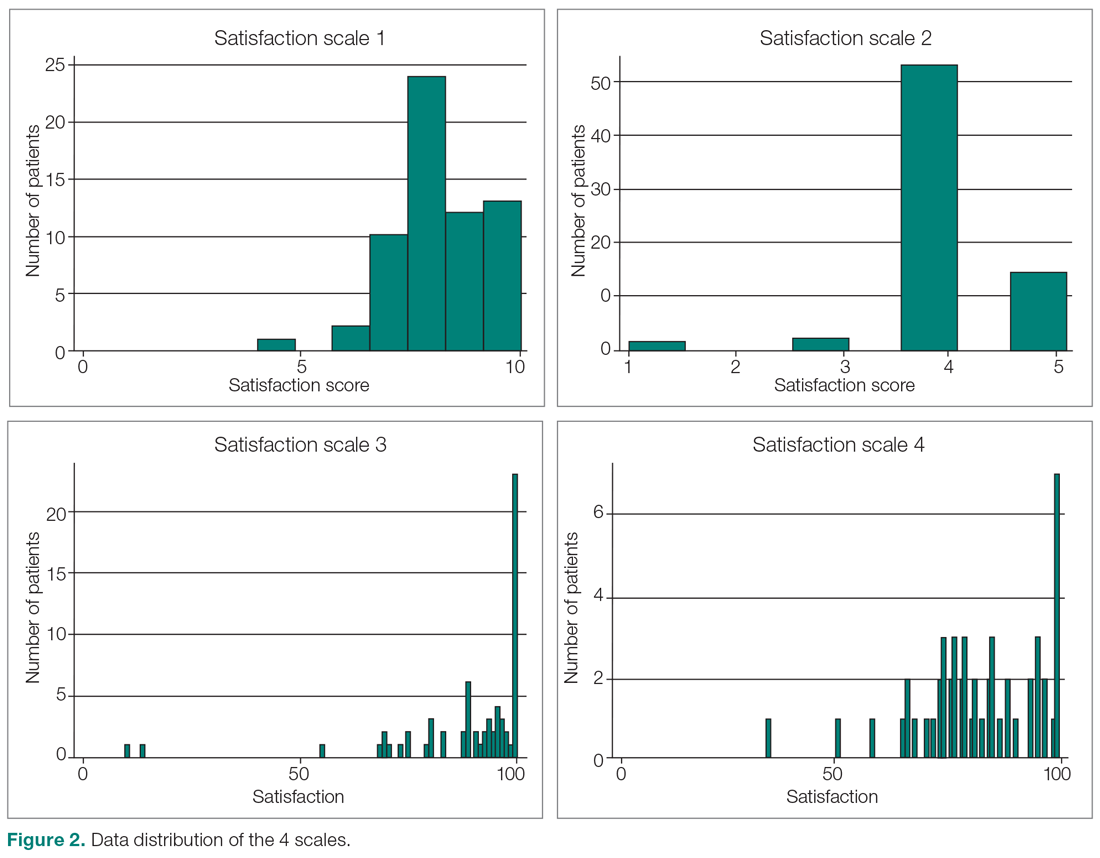

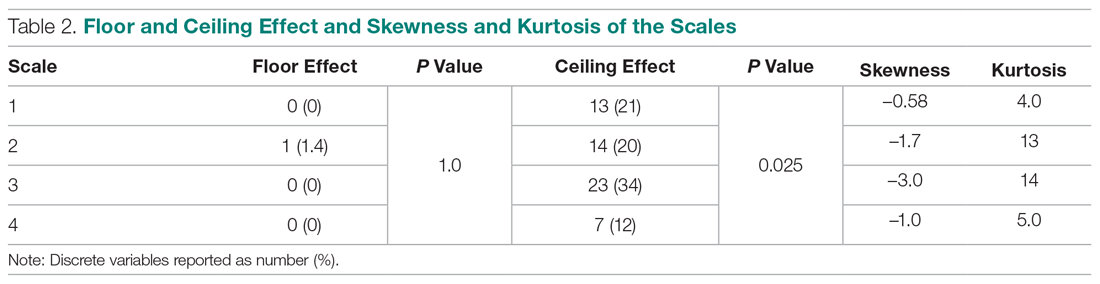

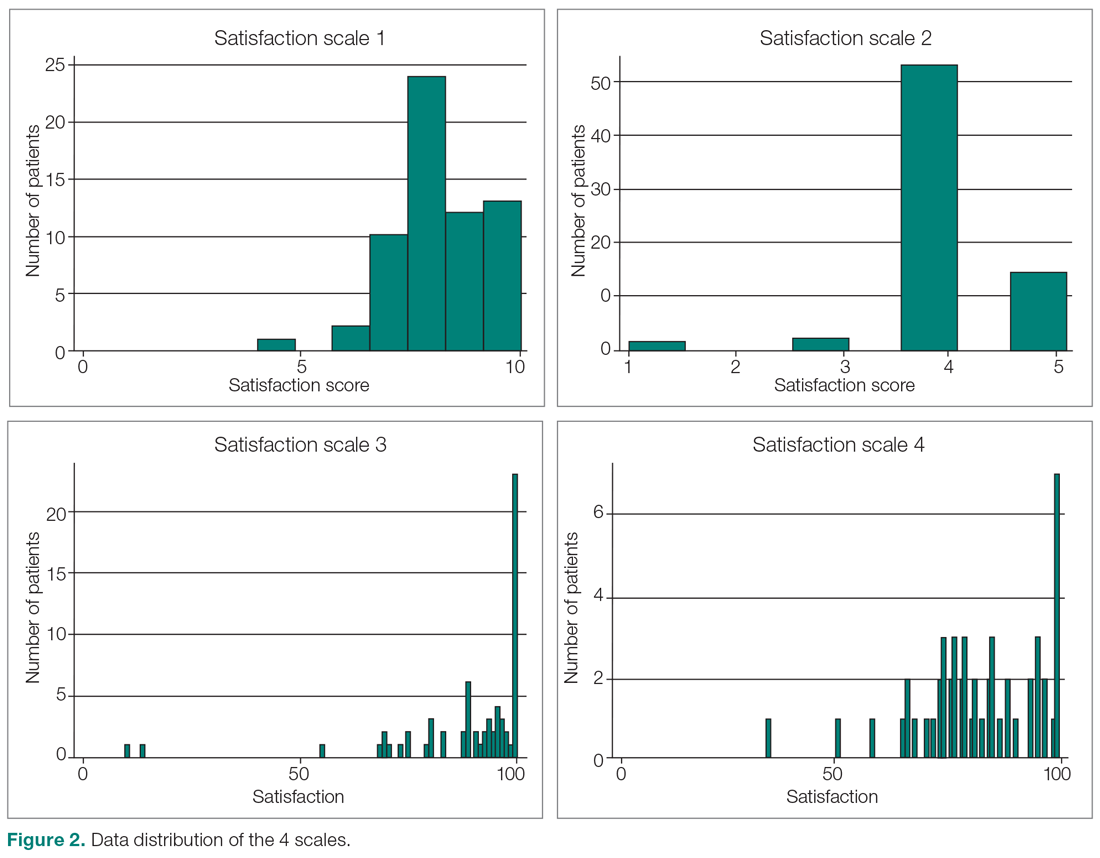

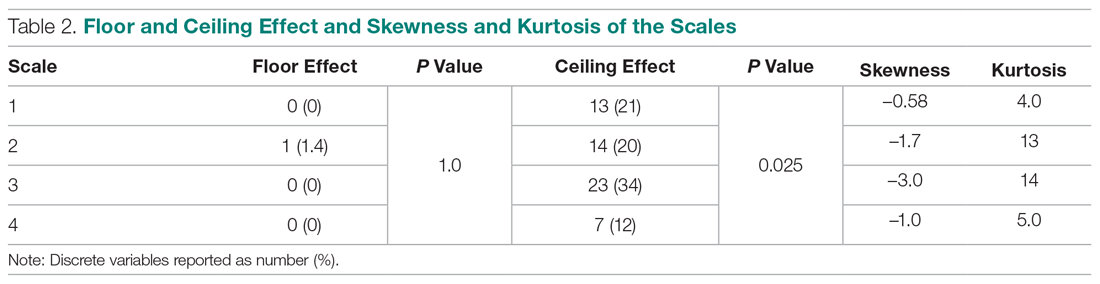

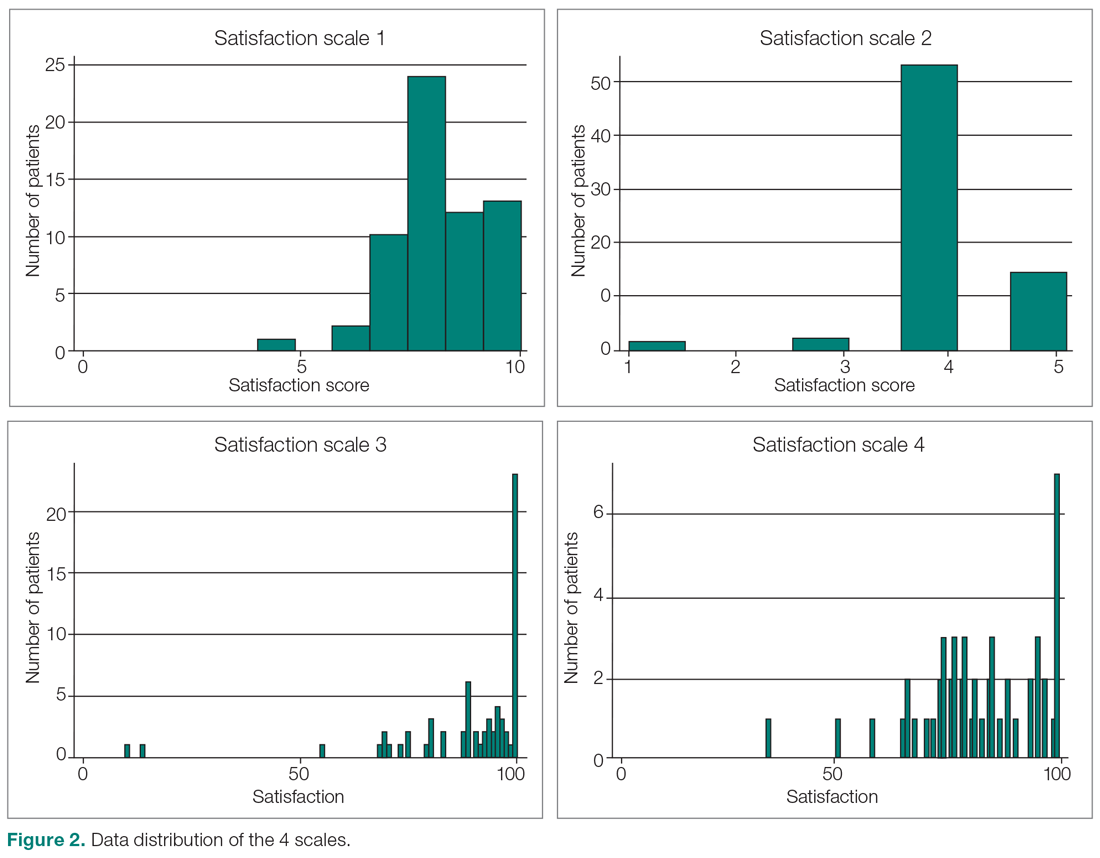

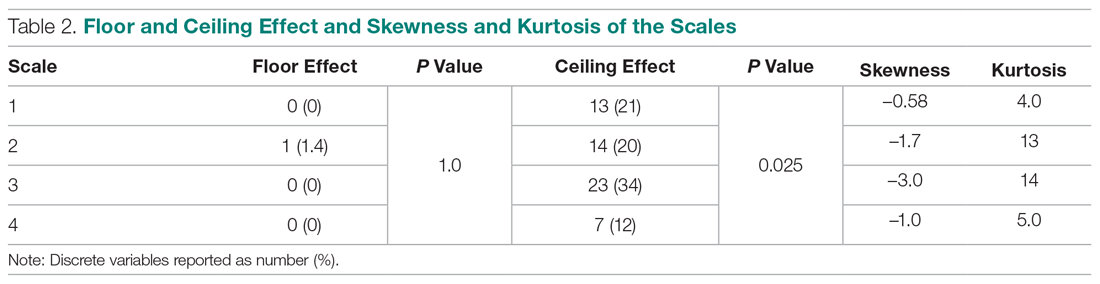

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of the scales was normally distributed.

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were 8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the 5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS, and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3 and Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the different scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%; Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the 5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and 20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease patient burden and limit overlap with measures of communication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect. We compared 4 different measures for overall scores, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. We found that scale type influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaningful information and identify areas for improvement, there must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of 15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.14 This scale with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0). However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks patients to use their own judgement in making the rating. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data distribution, and this might be explained by the presence of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might have allowed people to pick a number that represents their actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are conflicting,15 with some preferring Likert scales for their responsiveness16 and ease of use in practice,17 and others preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous, subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliability.18 Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase, the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal. This finding is in line with other study results.19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correlation with satisfaction.20-24 Given the effect that priming has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of future study.

The NPS varied substantially based on scale structure. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in the past to measure patient satisfaction with common hand surgery techniques and with community mental health services.25,26 These studies suggest that NPS could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical measures of satisfaction, after more research has been done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead to different results. More work is needed to determine the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.1 In addition, the majority of our patient population was white, employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizability to other populations with different demographics. Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon, and our results might not apply to other populations or clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study, we suspect that the findings can be generalized to specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceiling effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and structures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a medical visit so that we can better study what factors contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores, because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street, Austin, TX, 78712; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hospitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

1. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, Gucciardi DF. Identification of factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient clinic consultation: A qualitative study. Man Ther. 2016;25:48-55.

2. Kortlever JTP, Ottenhoff JSE, Vagner GA, et al. Visit duration does not correlate with perceived physician empathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:296-301.

3. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to influence response to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(3):CD003227.

4. Salisbury C, Burgess A, Lattimer V, et al. Developing a standard short questionnaire for the assessment of patient satisfaction with out-of-hours primary care. Fam Pract. 2005;22:560-569.

5. Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392-406.

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

7. Medicine USNLo. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16:153-163.

9. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843-853.

10. Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119-127.

11. Ho AD, Yu CC. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ Psychol Meas. 2015;75:365-388.

12. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52-54.

13. NICE Satmetrix. What is net promoter? https://www.netpromoter.com/know/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

14. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42.

15. Hasson D, Arnetz BB. Validation and findings comparing VAS vs. Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. Int Electronic J Health Educ. 2005;8:178-192.

16. Vickers AJ. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome measure of muscle soreness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999;15:709-716.

17. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales: data from a randomized trial. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:43-51.

18. Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:946-957.

19. Brunelli C, Zecca E, Martini C, et al. Comparison of numerical and verbal rating scales to measure pain exacerbations in patients with chronic cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:42.

20. Hageman MG, Briet JP, Bossen JK, et al. Do previsit expectations correlate with satisfaction of new patients presenting for evaluation with an orthopaedic surgical practice? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:716-721.

21. Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Vagner GA, et al. The effect of the content of patient-reported outcome measures on patient perceived empathy and satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:1141.e1-e9.

22. Mellema JJ, O’Connor CM, Overbeek CL, et al. The effect of feedback regarding coping strategies and illness behavior on hand surgery patient satisfaction and communication: a randomized controlled trial. Hand. 2015;10:503-511.

23. Tyser AR, Gaffney CJ, Zhang C, Presson AP. The association of patient satisfaction with pain, anxiety, and self-reported physical function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1811-1818.

24. Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1504-1508.

25. Stirling P, Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, et al. The Net Promoter Scores with Friends and Family Test after four hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Eur. 2019;44:290-295.

26. Wilberforce M, Poll S, Langham H, et al. Measuring the patient experience in community mental health services for older people: A study of the Net Promoter Score using the Friends and Family Test in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:31-37.

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, work status, insurance status, comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2) a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ in time needed to complete them; however, we did not explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also completed measures of psychological aspects of illness. The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping strategy for pain.8 Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health anxiety.9 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to measure symptoms of depression.10 Finally, the diagnosis was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satisfaction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to compare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects are present when patients select the lowest value in a similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an independent variable no longer influences the dependent variable being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, having a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents more peaked distribution.11,12 If skewness is 0 and kurtosis is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promoters (people who scored 9 or 10).13 NPS are widely used in the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale, with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed, and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled. The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65 years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%), and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of the scales was normally distributed.

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were 8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the 5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS, and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3 and Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the different scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%; Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the 5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and 20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease patient burden and limit overlap with measures of communication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect. We compared 4 different measures for overall scores, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. We found that scale type influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaningful information and identify areas for improvement, there must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of 15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.14 This scale with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0). However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks patients to use their own judgement in making the rating. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data distribution, and this might be explained by the presence of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might have allowed people to pick a number that represents their actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are conflicting,15 with some preferring Likert scales for their responsiveness16 and ease of use in practice,17 and others preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous, subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliability.18 Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase, the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal. This finding is in line with other study results.19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correlation with satisfaction.20-24 Given the effect that priming has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of future study.

The NPS varied substantially based on scale structure. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in the past to measure patient satisfaction with common hand surgery techniques and with community mental health services.25,26 These studies suggest that NPS could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical measures of satisfaction, after more research has been done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead to different results. More work is needed to determine the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.1 In addition, the majority of our patient population was white, employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizability to other populations with different demographics. Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon, and our results might not apply to other populations or clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study, we suspect that the findings can be generalized to specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceiling effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and structures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a medical visit so that we can better study what factors contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores, because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street, Austin, TX, 78712; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hospitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.