User login

When Your First Job Isn’t Forever: Lessons from My Journey and What Early-Career GIs Need to Know

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Developing the Next Generation of GI Leaders

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

Physician Compensation: Gains Small, Gaps Large

Few would deny that physicians today face many challenges: a growing and aging patient population, personnel shortages, mounting paperwork, regulatory and reimbursement pressures, and personal burnout. Collectively these could work to worsen patient access to care. Yet despite these headwinds, Doximity’s survey-based Physician Compensation Report 2025 found that more than three-quarters of physicians polled would still choose to enter their profession.

“Physician burnout isn’t new. It’s been a persistent problem over the past decade,” said Amit Phull, MD, chief clinical experience officer at Doximity. “In a Doximity poll of nearly 2,000 physicians conducted in May 2025, 85% reported they feel overworked, up from 73% just four years ago. As a result, about 68% of physicians said they are looking for an employment change or considering early retirement.”

Greater awareness of contemporary trends may help physicians make more-informed career decisions and more effectively advocate for both themselves and the patients who need them, the report’s authors stated.

Compensation Lag May Impact Care

A small overall average compensation increase of 3.7% from 2023 to 2024 – a slightly lower increase than the 5.9% in the prior year – has done little to close existing pay gaps across the profession.

In 2024, average compensation for men rose 5.7% over 2023, compared with just 1.7% for women – widening the gender pay gap to 26% vs 23% in 2023 and matching the gender gap seen in 2022. And significant disparities persist between physicians caring for adults vs children. In some specialties, the pay gap between pediatric and adult specialists exceeded 80% despite practitioners’ similar levels of training and clinical complexity.

Nearly 60% of respondents said reimbursement pressures could affect their ability to serve Medicare or Medicaid patients in the next year. Additionally, 81% reported that reimbursement policies have significantly contributed to the decline of private practices, and more than a third said they could stifle practice growth with compensation concerns forcing them to delay or cancel hiring or expansion plans. Almost 90% reported an adverse impact from physician shortages, with more citing an inability or limited ability to accept new patients.

Narrowing the Gap for Primary Care?

Over the past three years, the percent pay gap between primary care and specialist medicine declined modestly, the report noted. In 2024, surgical specialists earned 87% more than primary care physicians, down from 100% in 2022. Non-surgical specialists, emergency medicine physicians, and Ob/Gyns also continued to earn significantly more than primary care physicians, though the gaps have narrowed slightly.

“These trends come at a time when primary care remains critical to meeting high patient demand, especially amid ongoing physician shortages,” the report stated. “Primary care physicians continue to earn considerably less than many of their medical colleagues despite their essential role in the healthcare system.”

Significantly, many physicians believe that current reimbursement policies have contributed to the steady decline of independent practices in their fields. According to the American Medical Association, the share of physicians working in private practices dropped by 18 percentage points from 60.1% to 42.2% from 2012 to 2024.

The Specialties

This year’s review found that among 20 specialties, the highest average compensation occurred in surgical and procedural specialties, while the lowest paid were, as mentioned, pediatric medicine and primary care. Pediatric nephrology saw the largest average compensation growth in 2024 at 15.6%, yet compensation still lagged behind adult nephrology with a 40% pay gap.

By medical discipline, gastroenterologists ranked 13th overall in average annual compensation. Gastroenterology remained in the top 20 compensated specialties, with average annual compensation of $537,870 – an increase from $514,208 in 2024, representing a 4.5% growth rate over 2023. Neurosurgeons topped the list at $749,140, followed by thoracic surgeons at $689,969 and orthopedic surgeons at $679,517.

The three lowest-paid branches were all pediatric: endocrinology at $230,426, rheumatology at $231,574, and infectious diseases at $248,322. Pediatric gastroenterology paid somewhat higher at $298,457.

The largest disparities were seen in hematology and oncology, where adult specialists earned 93% more than their pediatric peers. Pediatric gastroenterology showed an 80% pay gap. There were also substantial pay differences across cardiology, pulmonology, and rheumatology. “These gaps appear to reflect a systemic lag in pay for pediatric specialty care, even as demand for pediatric subspecialists continues to rise,” the report stated.

Practice Setting and Location

Where a doctor practices impacts the bottom line, too: in 2024 the highest compensation reported for a metro area was in Rochester, Minnesota (the Mayo Clinic effect?), at $495,532, while the lowest reported was in Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina, at $368,782. St. Louis, Missouri ($484,883) and Los Angeles, California ($470,198) were 2nd and 3rd at the top of the list. Rochester, Minnesota, also emerged as best for annual compensation after cost-of-living adjustment, while Boston, Massachusetts, occupied the bottom rung.

The Gender Effect

With a women’s pay increase in 2024 of just 1.7%, the gender gap returned to its 2022-level disparity of 26%, with women physicians earning an average of $120,917 less than men after adjusting for specialty, location, and years of experience.

Doximity’s analysis of data from 2014 to 2019 estimated that on average men make at least $2 million more than women over the course of a 40-year career. This gap is often attributed to the fewer hours worked by female physician with their generally heavier familial responsibilities, “but Doximity’s gender wage gap analysis controls for the number of hours worked and career stage, along with specialty, work type, employment status, region, and credentials,” Phull said.

Women physicians had lower average earnings than men physicians across all specialties, a trend consistent with prior years. As a percentage of pay, the largest gender disparity was seen in pediatric nephrology (16.5%), a specialty that in fact saw the largest annual growth in physician pay. Neurosurgery had the smallest gender gap at 11.3%, while infectious diseases came in at 11.5% and oncology at 12%.

According to Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, executive director of the F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and past president of AGA, the remuneration gender gap in gastroenterology is being taken seriously by AGA and several other GI societies. “The discrepancies in pay start from the beginning and therefore are magnified over time. We are helping to empower women to negotiate better as well as to gather data on the roots of inequity, she told GI & Hepatology News.

The AGA Women’s Committee has developed a project to support the advancement of women in gastroenterology, Abreu said. The initiative, which includes the AGA Gender Equity Framework and Gender Equity Road Map. focuses attention on disparities in the workplace and promotes opportunities for women’s leadership, career advancement, mentorship and physician health and wellness, she added.

Are these disparities due mainly to the “motherhood penalty,” with career interruption and time lost to maternity leave and fewer hours worked owing to the greater parenting burden of physician mothers? Or are they due to the systemic effects of gender expectations around compensation?

Hours worked appear to be a factor. A 2017 study of dual physician couples found that among childless respondents men worked an average of 57 hours and women 52 hours weekly. Compared with childless men, men with children worked similar numbers of hours weekly. However, compared with childless physicians, mothers worked significantly fewer hours – roughly 40 to 43 hours weekly – depending on the age of their youngest child.

Abreu pushed back on this stereotype. “Most women physicians, including gastroenterologists, do not take the maternity leave they are allowed because they are concerned about burdening their colleagues,” she said. “Thus, it is unlikely to explain the disparities. Many systemic issues remain challenging, but we want women to be empowered to advocate for themselves at the time of hiring and along the arc of their career paths.”

In Abreu’s view, having women assume more leadership roles in the field of gastroenterology provides an opportunity to focus on reducing the disparities in compensation.

Regardless of gender, among all physicians surveyed, autonomy and work-life balance appeared to be a high priority: 77% of doctors said they would be willing to accept or have already accepted lower pay for more autonomy or work-life balance. “Overwork appears to be especially prevalent among women physicians,” said Phull, noting that 91% of women respondents reported being overworked compared with 80% of men. “This overwork has compelled 74% of women to consider making a career change, compared with 62% of men.” Differences emerged among specialties as well: 90% of primary care physicians said they are overworked compared with 84% of surgeons and 83% of non-surgical specialists.

Looking ahead, the report raised an important question. Are we relying too heavily on physicians rather than addressing the underlying need for policies that support a healthier, more sustainable future for all? “Building that future will take more than physician dedication alone,” Phull said. “It will require meaningful collaboration across the entire health care ecosystem – including health systems, hospitals, payors, and policymakers. And physicians must not only have a voice in shaping the path forward; they must have a seat at the table.”

Abreu reported no conflicts of interest in regard to her comments.

Few would deny that physicians today face many challenges: a growing and aging patient population, personnel shortages, mounting paperwork, regulatory and reimbursement pressures, and personal burnout. Collectively these could work to worsen patient access to care. Yet despite these headwinds, Doximity’s survey-based Physician Compensation Report 2025 found that more than three-quarters of physicians polled would still choose to enter their profession.

“Physician burnout isn’t new. It’s been a persistent problem over the past decade,” said Amit Phull, MD, chief clinical experience officer at Doximity. “In a Doximity poll of nearly 2,000 physicians conducted in May 2025, 85% reported they feel overworked, up from 73% just four years ago. As a result, about 68% of physicians said they are looking for an employment change or considering early retirement.”

Greater awareness of contemporary trends may help physicians make more-informed career decisions and more effectively advocate for both themselves and the patients who need them, the report’s authors stated.

Compensation Lag May Impact Care

A small overall average compensation increase of 3.7% from 2023 to 2024 – a slightly lower increase than the 5.9% in the prior year – has done little to close existing pay gaps across the profession.

In 2024, average compensation for men rose 5.7% over 2023, compared with just 1.7% for women – widening the gender pay gap to 26% vs 23% in 2023 and matching the gender gap seen in 2022. And significant disparities persist between physicians caring for adults vs children. In some specialties, the pay gap between pediatric and adult specialists exceeded 80% despite practitioners’ similar levels of training and clinical complexity.

Nearly 60% of respondents said reimbursement pressures could affect their ability to serve Medicare or Medicaid patients in the next year. Additionally, 81% reported that reimbursement policies have significantly contributed to the decline of private practices, and more than a third said they could stifle practice growth with compensation concerns forcing them to delay or cancel hiring or expansion plans. Almost 90% reported an adverse impact from physician shortages, with more citing an inability or limited ability to accept new patients.

Narrowing the Gap for Primary Care?

Over the past three years, the percent pay gap between primary care and specialist medicine declined modestly, the report noted. In 2024, surgical specialists earned 87% more than primary care physicians, down from 100% in 2022. Non-surgical specialists, emergency medicine physicians, and Ob/Gyns also continued to earn significantly more than primary care physicians, though the gaps have narrowed slightly.

“These trends come at a time when primary care remains critical to meeting high patient demand, especially amid ongoing physician shortages,” the report stated. “Primary care physicians continue to earn considerably less than many of their medical colleagues despite their essential role in the healthcare system.”

Significantly, many physicians believe that current reimbursement policies have contributed to the steady decline of independent practices in their fields. According to the American Medical Association, the share of physicians working in private practices dropped by 18 percentage points from 60.1% to 42.2% from 2012 to 2024.

The Specialties

This year’s review found that among 20 specialties, the highest average compensation occurred in surgical and procedural specialties, while the lowest paid were, as mentioned, pediatric medicine and primary care. Pediatric nephrology saw the largest average compensation growth in 2024 at 15.6%, yet compensation still lagged behind adult nephrology with a 40% pay gap.

By medical discipline, gastroenterologists ranked 13th overall in average annual compensation. Gastroenterology remained in the top 20 compensated specialties, with average annual compensation of $537,870 – an increase from $514,208 in 2024, representing a 4.5% growth rate over 2023. Neurosurgeons topped the list at $749,140, followed by thoracic surgeons at $689,969 and orthopedic surgeons at $679,517.

The three lowest-paid branches were all pediatric: endocrinology at $230,426, rheumatology at $231,574, and infectious diseases at $248,322. Pediatric gastroenterology paid somewhat higher at $298,457.

The largest disparities were seen in hematology and oncology, where adult specialists earned 93% more than their pediatric peers. Pediatric gastroenterology showed an 80% pay gap. There were also substantial pay differences across cardiology, pulmonology, and rheumatology. “These gaps appear to reflect a systemic lag in pay for pediatric specialty care, even as demand for pediatric subspecialists continues to rise,” the report stated.

Practice Setting and Location

Where a doctor practices impacts the bottom line, too: in 2024 the highest compensation reported for a metro area was in Rochester, Minnesota (the Mayo Clinic effect?), at $495,532, while the lowest reported was in Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina, at $368,782. St. Louis, Missouri ($484,883) and Los Angeles, California ($470,198) were 2nd and 3rd at the top of the list. Rochester, Minnesota, also emerged as best for annual compensation after cost-of-living adjustment, while Boston, Massachusetts, occupied the bottom rung.

The Gender Effect

With a women’s pay increase in 2024 of just 1.7%, the gender gap returned to its 2022-level disparity of 26%, with women physicians earning an average of $120,917 less than men after adjusting for specialty, location, and years of experience.

Doximity’s analysis of data from 2014 to 2019 estimated that on average men make at least $2 million more than women over the course of a 40-year career. This gap is often attributed to the fewer hours worked by female physician with their generally heavier familial responsibilities, “but Doximity’s gender wage gap analysis controls for the number of hours worked and career stage, along with specialty, work type, employment status, region, and credentials,” Phull said.

Women physicians had lower average earnings than men physicians across all specialties, a trend consistent with prior years. As a percentage of pay, the largest gender disparity was seen in pediatric nephrology (16.5%), a specialty that in fact saw the largest annual growth in physician pay. Neurosurgery had the smallest gender gap at 11.3%, while infectious diseases came in at 11.5% and oncology at 12%.

According to Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, executive director of the F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and past president of AGA, the remuneration gender gap in gastroenterology is being taken seriously by AGA and several other GI societies. “The discrepancies in pay start from the beginning and therefore are magnified over time. We are helping to empower women to negotiate better as well as to gather data on the roots of inequity, she told GI & Hepatology News.

The AGA Women’s Committee has developed a project to support the advancement of women in gastroenterology, Abreu said. The initiative, which includes the AGA Gender Equity Framework and Gender Equity Road Map. focuses attention on disparities in the workplace and promotes opportunities for women’s leadership, career advancement, mentorship and physician health and wellness, she added.

Are these disparities due mainly to the “motherhood penalty,” with career interruption and time lost to maternity leave and fewer hours worked owing to the greater parenting burden of physician mothers? Or are they due to the systemic effects of gender expectations around compensation?

Hours worked appear to be a factor. A 2017 study of dual physician couples found that among childless respondents men worked an average of 57 hours and women 52 hours weekly. Compared with childless men, men with children worked similar numbers of hours weekly. However, compared with childless physicians, mothers worked significantly fewer hours – roughly 40 to 43 hours weekly – depending on the age of their youngest child.

Abreu pushed back on this stereotype. “Most women physicians, including gastroenterologists, do not take the maternity leave they are allowed because they are concerned about burdening their colleagues,” she said. “Thus, it is unlikely to explain the disparities. Many systemic issues remain challenging, but we want women to be empowered to advocate for themselves at the time of hiring and along the arc of their career paths.”

In Abreu’s view, having women assume more leadership roles in the field of gastroenterology provides an opportunity to focus on reducing the disparities in compensation.

Regardless of gender, among all physicians surveyed, autonomy and work-life balance appeared to be a high priority: 77% of doctors said they would be willing to accept or have already accepted lower pay for more autonomy or work-life balance. “Overwork appears to be especially prevalent among women physicians,” said Phull, noting that 91% of women respondents reported being overworked compared with 80% of men. “This overwork has compelled 74% of women to consider making a career change, compared with 62% of men.” Differences emerged among specialties as well: 90% of primary care physicians said they are overworked compared with 84% of surgeons and 83% of non-surgical specialists.

Looking ahead, the report raised an important question. Are we relying too heavily on physicians rather than addressing the underlying need for policies that support a healthier, more sustainable future for all? “Building that future will take more than physician dedication alone,” Phull said. “It will require meaningful collaboration across the entire health care ecosystem – including health systems, hospitals, payors, and policymakers. And physicians must not only have a voice in shaping the path forward; they must have a seat at the table.”

Abreu reported no conflicts of interest in regard to her comments.

Few would deny that physicians today face many challenges: a growing and aging patient population, personnel shortages, mounting paperwork, regulatory and reimbursement pressures, and personal burnout. Collectively these could work to worsen patient access to care. Yet despite these headwinds, Doximity’s survey-based Physician Compensation Report 2025 found that more than three-quarters of physicians polled would still choose to enter their profession.

“Physician burnout isn’t new. It’s been a persistent problem over the past decade,” said Amit Phull, MD, chief clinical experience officer at Doximity. “In a Doximity poll of nearly 2,000 physicians conducted in May 2025, 85% reported they feel overworked, up from 73% just four years ago. As a result, about 68% of physicians said they are looking for an employment change or considering early retirement.”

Greater awareness of contemporary trends may help physicians make more-informed career decisions and more effectively advocate for both themselves and the patients who need them, the report’s authors stated.

Compensation Lag May Impact Care

A small overall average compensation increase of 3.7% from 2023 to 2024 – a slightly lower increase than the 5.9% in the prior year – has done little to close existing pay gaps across the profession.

In 2024, average compensation for men rose 5.7% over 2023, compared with just 1.7% for women – widening the gender pay gap to 26% vs 23% in 2023 and matching the gender gap seen in 2022. And significant disparities persist between physicians caring for adults vs children. In some specialties, the pay gap between pediatric and adult specialists exceeded 80% despite practitioners’ similar levels of training and clinical complexity.

Nearly 60% of respondents said reimbursement pressures could affect their ability to serve Medicare or Medicaid patients in the next year. Additionally, 81% reported that reimbursement policies have significantly contributed to the decline of private practices, and more than a third said they could stifle practice growth with compensation concerns forcing them to delay or cancel hiring or expansion plans. Almost 90% reported an adverse impact from physician shortages, with more citing an inability or limited ability to accept new patients.

Narrowing the Gap for Primary Care?

Over the past three years, the percent pay gap between primary care and specialist medicine declined modestly, the report noted. In 2024, surgical specialists earned 87% more than primary care physicians, down from 100% in 2022. Non-surgical specialists, emergency medicine physicians, and Ob/Gyns also continued to earn significantly more than primary care physicians, though the gaps have narrowed slightly.

“These trends come at a time when primary care remains critical to meeting high patient demand, especially amid ongoing physician shortages,” the report stated. “Primary care physicians continue to earn considerably less than many of their medical colleagues despite their essential role in the healthcare system.”

Significantly, many physicians believe that current reimbursement policies have contributed to the steady decline of independent practices in their fields. According to the American Medical Association, the share of physicians working in private practices dropped by 18 percentage points from 60.1% to 42.2% from 2012 to 2024.

The Specialties

This year’s review found that among 20 specialties, the highest average compensation occurred in surgical and procedural specialties, while the lowest paid were, as mentioned, pediatric medicine and primary care. Pediatric nephrology saw the largest average compensation growth in 2024 at 15.6%, yet compensation still lagged behind adult nephrology with a 40% pay gap.

By medical discipline, gastroenterologists ranked 13th overall in average annual compensation. Gastroenterology remained in the top 20 compensated specialties, with average annual compensation of $537,870 – an increase from $514,208 in 2024, representing a 4.5% growth rate over 2023. Neurosurgeons topped the list at $749,140, followed by thoracic surgeons at $689,969 and orthopedic surgeons at $679,517.

The three lowest-paid branches were all pediatric: endocrinology at $230,426, rheumatology at $231,574, and infectious diseases at $248,322. Pediatric gastroenterology paid somewhat higher at $298,457.

The largest disparities were seen in hematology and oncology, where adult specialists earned 93% more than their pediatric peers. Pediatric gastroenterology showed an 80% pay gap. There were also substantial pay differences across cardiology, pulmonology, and rheumatology. “These gaps appear to reflect a systemic lag in pay for pediatric specialty care, even as demand for pediatric subspecialists continues to rise,” the report stated.

Practice Setting and Location

Where a doctor practices impacts the bottom line, too: in 2024 the highest compensation reported for a metro area was in Rochester, Minnesota (the Mayo Clinic effect?), at $495,532, while the lowest reported was in Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina, at $368,782. St. Louis, Missouri ($484,883) and Los Angeles, California ($470,198) were 2nd and 3rd at the top of the list. Rochester, Minnesota, also emerged as best for annual compensation after cost-of-living adjustment, while Boston, Massachusetts, occupied the bottom rung.

The Gender Effect

With a women’s pay increase in 2024 of just 1.7%, the gender gap returned to its 2022-level disparity of 26%, with women physicians earning an average of $120,917 less than men after adjusting for specialty, location, and years of experience.

Doximity’s analysis of data from 2014 to 2019 estimated that on average men make at least $2 million more than women over the course of a 40-year career. This gap is often attributed to the fewer hours worked by female physician with their generally heavier familial responsibilities, “but Doximity’s gender wage gap analysis controls for the number of hours worked and career stage, along with specialty, work type, employment status, region, and credentials,” Phull said.

Women physicians had lower average earnings than men physicians across all specialties, a trend consistent with prior years. As a percentage of pay, the largest gender disparity was seen in pediatric nephrology (16.5%), a specialty that in fact saw the largest annual growth in physician pay. Neurosurgery had the smallest gender gap at 11.3%, while infectious diseases came in at 11.5% and oncology at 12%.

According to Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, executive director of the F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and past president of AGA, the remuneration gender gap in gastroenterology is being taken seriously by AGA and several other GI societies. “The discrepancies in pay start from the beginning and therefore are magnified over time. We are helping to empower women to negotiate better as well as to gather data on the roots of inequity, she told GI & Hepatology News.

The AGA Women’s Committee has developed a project to support the advancement of women in gastroenterology, Abreu said. The initiative, which includes the AGA Gender Equity Framework and Gender Equity Road Map. focuses attention on disparities in the workplace and promotes opportunities for women’s leadership, career advancement, mentorship and physician health and wellness, she added.

Are these disparities due mainly to the “motherhood penalty,” with career interruption and time lost to maternity leave and fewer hours worked owing to the greater parenting burden of physician mothers? Or are they due to the systemic effects of gender expectations around compensation?

Hours worked appear to be a factor. A 2017 study of dual physician couples found that among childless respondents men worked an average of 57 hours and women 52 hours weekly. Compared with childless men, men with children worked similar numbers of hours weekly. However, compared with childless physicians, mothers worked significantly fewer hours – roughly 40 to 43 hours weekly – depending on the age of their youngest child.

Abreu pushed back on this stereotype. “Most women physicians, including gastroenterologists, do not take the maternity leave they are allowed because they are concerned about burdening their colleagues,” she said. “Thus, it is unlikely to explain the disparities. Many systemic issues remain challenging, but we want women to be empowered to advocate for themselves at the time of hiring and along the arc of their career paths.”

In Abreu’s view, having women assume more leadership roles in the field of gastroenterology provides an opportunity to focus on reducing the disparities in compensation.

Regardless of gender, among all physicians surveyed, autonomy and work-life balance appeared to be a high priority: 77% of doctors said they would be willing to accept or have already accepted lower pay for more autonomy or work-life balance. “Overwork appears to be especially prevalent among women physicians,” said Phull, noting that 91% of women respondents reported being overworked compared with 80% of men. “This overwork has compelled 74% of women to consider making a career change, compared with 62% of men.” Differences emerged among specialties as well: 90% of primary care physicians said they are overworked compared with 84% of surgeons and 83% of non-surgical specialists.

Looking ahead, the report raised an important question. Are we relying too heavily on physicians rather than addressing the underlying need for policies that support a healthier, more sustainable future for all? “Building that future will take more than physician dedication alone,” Phull said. “It will require meaningful collaboration across the entire health care ecosystem – including health systems, hospitals, payors, and policymakers. And physicians must not only have a voice in shaping the path forward; they must have a seat at the table.”

Abreu reported no conflicts of interest in regard to her comments.

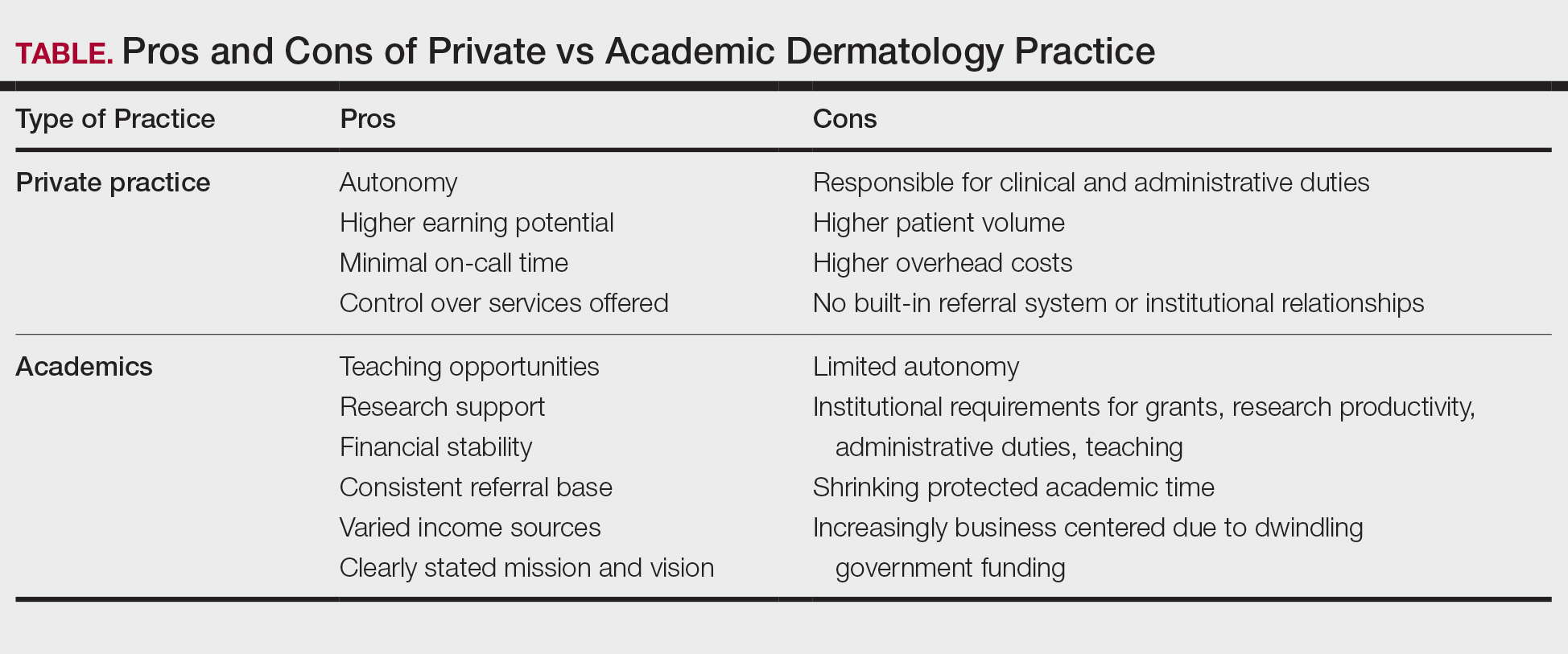

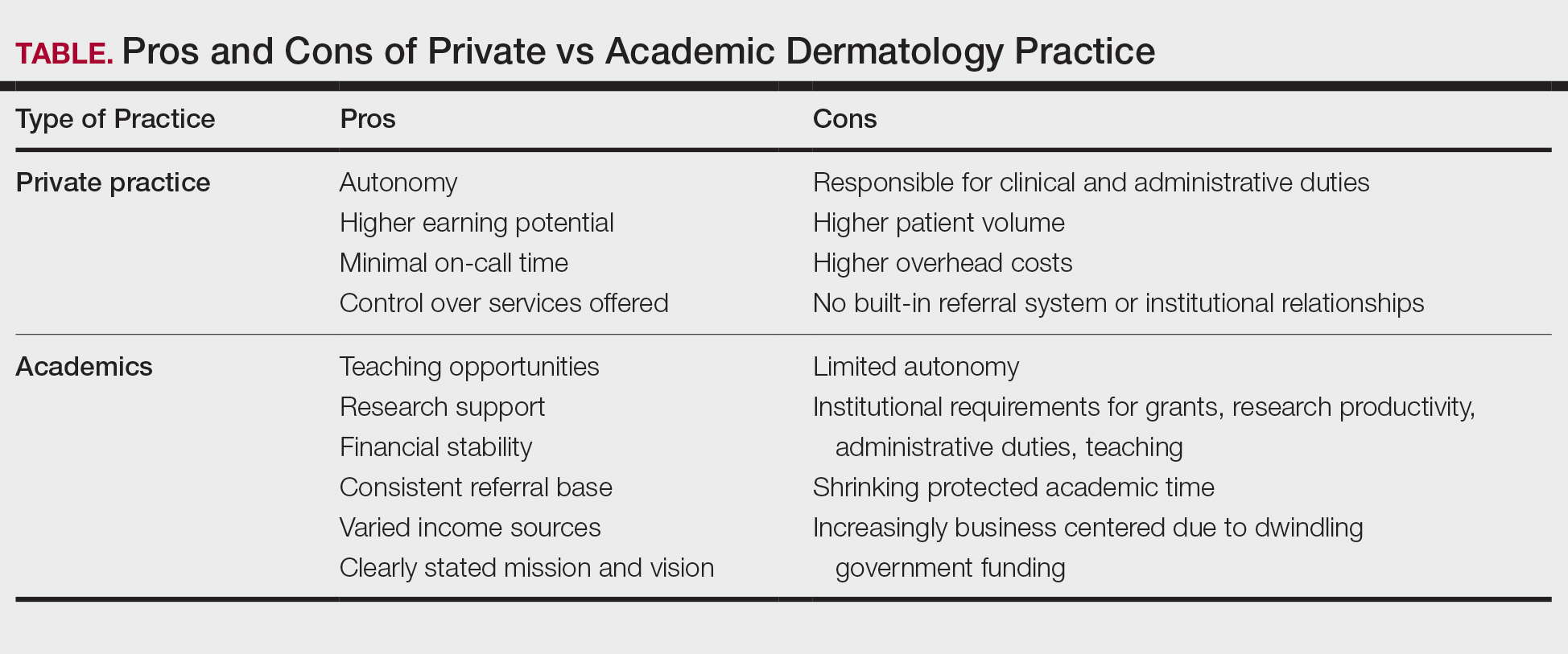

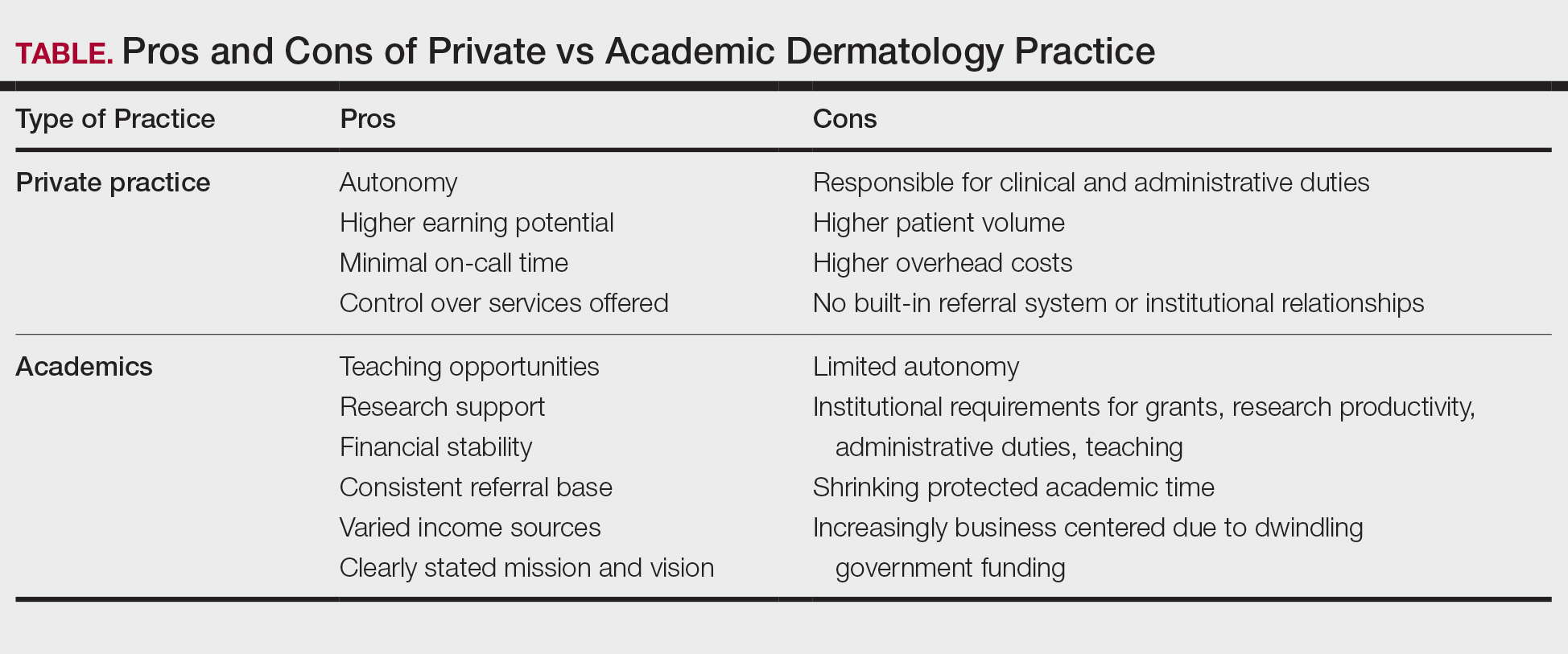

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

PRACTICE POINTS

- Direct care practices may be the new horizon of health care.

- Starting a direct care practice offers autonomy but demands entrepreneurial readiness.

- New dermatologists can enjoy control over scheduling, pricing, and patient care, but success requires business acumen, financial planning, and comfort with risk.

Letter: Another View on Private Equity in GI

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

What are the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD’s) top advocacy priorities related to Medicare physician reimbursement?

Dr. Taylor: Medicare physician payment has failed to keep up with inflation, threatening the viability of medical practices. The AAD urges Congress to stabilize the Medicare payment system to ensure continued patient access to essential health care by

What is the AAD’s stance on transitioning from traditional fee-for-service to value-based care models in dermatology under Medicare?

Dr. Taylor: Current value-based programs are extremely burdensome, have not demonstrated improved patient care, and are not clinically relevant to physicians or patients. The AAD has serious concerns about the viability and effectiveness of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), especially the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Numerous studies have highlighted persistent challenges associated with MIPS, including practices serving high-risk patients and those that are small or in rural areas. For instance, researchers examined whether MIPS disproportionately penalized surgeons who care for these patients and found a connection between caring for these patients, lower MIPS scores, and a higher likelihood of facing negative payment adjustments.

Additionally, the US Government Accountability Office was tasked with reviewing several aspects concerning small and rural practices in relation to Medicare payment incentive programs, including MIPS. Findings indicated that physician practices with 15 or fewer providers, whether located in rural or nonrural areas, had a higher likelihood of receiving negative payment adjustments in Medicare incentive programs compared to larger practices. To maximize participation and facilitate the best possible outcomes for dermatologists within the MIPS program, the AAD maintains that we must continue to develop and advocate that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approve dermatology-specific measures for MIPS reporting.

Does the AAD have plans to develop or expand dermatology-specific quality measures that are more clinically relevant and less administratively taxing?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is committed to ensuring that dermatologists can be successful in the QPP and its MIPS Value Pathways and Advanced Alternative Payment Model programs. These payment pathways for QPP-eligible participants allow physicians to increase their future Medicare reimbursements but also penalize those who do not meet performance objectives. The AAD is constantly reviewing and proposing new dermatology-specific quality measures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services based on member feedback to reduce administrative burdens of MIPS reporting. All of our quality measures are developed by dermatologists for dermatologists.

How is the AAD supporting practices dealing with insurer-mandated switch policies that disrupt continuity of care and increase documentation burden?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD works with private payers to alleviate administrative burdens for dermatologists, maintain appropriate reimbursement for services provided, and ensure patients can access covered quality care by building and maintaining relationships with public and private payers. This critical collaboration addresses immediate needs affecting our members’ ability to deliver care, such as when policy changes affect claims and formulary coverage or payment. Our coordinated strategy ensures payer policies align with everyday practice for dermatologists so they can focus on treating patients. The AAD has resources and tools to guide dermatology practices in appropriate documentation and coding.

What initiatives is the AAD pursuing to specifically support independent or small dermatology practices in coping with administrative overload?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is continuously advocating for our small and independent dermatology practices. In every comment letter we submit on proposed medical practice reporting regulation, we demand small practice exemptions. Moreover, the AAD has resources and practical tools for all types of practices to cope with administrative burdens, including MIPS reporting requirements. These resources and tools were created by dermatologists for dermatologists to take the guesswork out of administrative compliance. DataDerm is the AAD’s clinical data registry used for MIPS reporting. Since its launch in 2016, DataDerm has become dermatology’s largest clinical data registry, capturing information on more than 16 million unique patients and 69 million encounters. It supports the advancement of skin disease diagnosis and treatment, informs clinical practice, streamlines MIPS reporting, and drives clinically relevant research using real-world data.

What are the biggest contributors to physician burnout right now? What resources does AAD offer to support dermatologists in managing burnout?

Dr. Taylor: The biggest contributors to burnout that dermatologists are facing are demanding workloads, administrative burdens, and loss of autonomy. Dermatologists welcome medical challenges, but they face growing administrative and regulatory burdens that take time away from patient care and contribute to burnout. Taking a wellness-centered approach can help, which is why the AAD includes both practical tools to reduce burdens and strategies to sustain your practice in its online resources. The burnout and wellness section of the AAD website can help with administrative burdens, building a supportive work culture, recognizing drivers of burnout, reconnecting with your purpose, and more.

How is the AAD working to ensure that the expanding scope of practice does not compromise patient safety, particularly when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of complex skin cancers or prescribing systemic medications?