User login

A 17-year-old male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a year-long rash

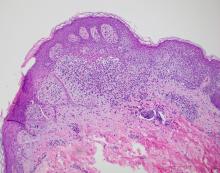

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A 17-year-old healthy male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on the skin which has been present on and off for a year. During the initial presentation, the lesions were clustered on the back, were slightly itchy, and resolved after 3 months. Several new lesions have developed on the neck, torso, and extremities, leaving hypopigmented marks on the skin. He has previously been treated with topical antifungal creams, oral fluconazole, and triamcinolone ointment without resolution of the lesions.

He is not involved in any contact sports, he has not traveled outside the country, and is not taking any other medications. He is not sexually active. He also has a diagnosis of mild acne that he is currently treating with over-the-counter medications.

On physical exam he had several annular plaques with central atrophic centers and no scale. He also had some hypo- and hyperpigmented macules at the sites of prior skin lesions

‘Striking’ rate of mental health comorbidities in epilepsy

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , new research reveals.

“We hope these results inspire epileptologists and neurologists to both recognize and screen for suicide ideation and behaviors in their adolescent patients,” said study investigator Hadley Greenwood, a third-year medical student at New York University.

The new data should also encourage providers “to become more comfortable” providing support to patients, “be that by increasing their familiarity with prescribing different antidepressants or by being well versed in how to connect patients to resources within their community,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The findings were presented here at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Little research

Previous studies have reported on the prevalence of suicidality as well as depression and anxiety among adults with epilepsy. “We wanted to look at adolescents because there’s much less in the literature out there about psychiatric comorbidity, and specifically suicidality, in this population,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers used data from the Human Epilepsy Project, a study that collected data from 34 sites in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia from 2012 to 2017.

From a cohort of more than 400 participants, researchers identified 67 patients aged 11-17 years who were enrolled within 4 months of starting treatment for focal epilepsy.

Participants completed the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) at enrollment and at follow-ups over 36 months. The C-SSRS measures suicidal ideation and severity, said Mr. Greenwood.

“It’s scaled from passive suicide ideation, such as thoughts of ‘I wish I were dead’ without active intent, all the way up to active suicidal ideation with a plan and intent.”

Researchers were able to distinguish individuals with passive suicide ideation from those with more serious intentions, said Mr. Greenwood. They used medical records to evaluate the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior.

The investigators found that more than one in five (20.9%) teens endorsed any lifetime suicide ideation. This, said Mr. Greenwood, is “roughly equivalent” to the prevalence reported earlier in the adult cohort of the Human Epilepsy Project (21.6%).

‘Striking’ rate

The fact that one in five adolescents had any lifetime suicide ideation is “definitely a striking number,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers found that 15% of patients experienced active suicide ideation, 7.5% exhibited preparatory or suicidal behaviors, and 3% had made a prior suicide attempt.

All of these percentages increased at 3 years: Thirty-one percent for suicide ideation; 25% for active suicide behavior, 15% for preparatory or suicide behaviors, and 5% for prior suicide attempt.

The fact that nearly one in three adolescents endorsed suicide ideation at 3 years is another “striking” finding, said Mr. Greenwood.

Of the 53 adolescents who had never had suicide ideation at the time of enrollment, 7 endorsed new-onset suicide ideation in the follow-up period. Five of 14 who had had suicide ideation at some point prior to enrollment continued to endorse it.

“The value of the study is identifying the prevalence and identifying the significant number of adolescents with epilepsy who are endorsing either suicide ideation or suicidal behaviors,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The researchers found that among younger teens (aged 11–14 years) rates of suicide ideation were higher than among their older counterparts (aged 15–17 years).

The study does not shed light on the biological connection between epilepsy and suicidality, but Mr. Greenwood noted that prior research has suggested a bidirectional relationship.

“Depression and other psychiatric comorbidities might exist prior to epileptic activity and actually predispose to epileptic activity.”

Mr. Greenwood noted that suicide ideation has “spiked” recently across the general population, and so it’s difficult to compare the prevalence in her study with “today’s prevalence.”

However, other research generally shows that the suicide ideation rate in the general adolescent population is much lower than in teens with epilepsy.

Unique aspects of the current study are that it reports suicide ideation and behaviors at around the time of an epilepsy diagnosis and documents how suicidality progresses or resolves over time, said Mr. Greenwood.

Underdiagnosed, undertreated

Commenting on the research, Elizabeth Donner, MD, director of the comprehensive epilepsy program, Hospital for Sick Children, and associate professor, department of pediatrics, University of Toronto, said a “key point” from the study is that the suicidality rate among teens with epilepsy exceeds that of children not living with epilepsy.

“We are significantly underdiagnosing and undertreating the mental health comorbidities in epilepsy,” said Dr. Donner. “Epilepsy is a brain disease and so are mental health disorders, so it shouldn’t come as any surprise that they coexist in individuals with epilepsy.”

The new results contribute to what is already known about the significant mortality rates among persons with epilepsy, said Dr. Donner. She referred to a 2018 study that showed that people with epilepsy were 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide.

Other research has shown that people with epilepsy are 10 times more likely to die by drowning, mostly in the bathtub, said Dr. Donner.

“You would think that we’re educating these people about risks related to their epilepsy, but either the messages don’t get through, or they don’t know how to keep themselves safe,” she said.

“This needs to be seen in a bigger picture, and the bigger picture is we need to recognize comorbid mental health issues; we need to address them once recognized; and then we need to counsel and support people to live safely with their epilepsy.

The study received funding from the Epilepsy Study Consortium, Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures (FACES) and other related foundations, UCB, Pfizer, Eisai, Lundbeck, and Sunovion. Mr. Greenwood and Dr. Donner report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , new research reveals.

“We hope these results inspire epileptologists and neurologists to both recognize and screen for suicide ideation and behaviors in their adolescent patients,” said study investigator Hadley Greenwood, a third-year medical student at New York University.

The new data should also encourage providers “to become more comfortable” providing support to patients, “be that by increasing their familiarity with prescribing different antidepressants or by being well versed in how to connect patients to resources within their community,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The findings were presented here at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Little research

Previous studies have reported on the prevalence of suicidality as well as depression and anxiety among adults with epilepsy. “We wanted to look at adolescents because there’s much less in the literature out there about psychiatric comorbidity, and specifically suicidality, in this population,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers used data from the Human Epilepsy Project, a study that collected data from 34 sites in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia from 2012 to 2017.

From a cohort of more than 400 participants, researchers identified 67 patients aged 11-17 years who were enrolled within 4 months of starting treatment for focal epilepsy.

Participants completed the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) at enrollment and at follow-ups over 36 months. The C-SSRS measures suicidal ideation and severity, said Mr. Greenwood.

“It’s scaled from passive suicide ideation, such as thoughts of ‘I wish I were dead’ without active intent, all the way up to active suicidal ideation with a plan and intent.”

Researchers were able to distinguish individuals with passive suicide ideation from those with more serious intentions, said Mr. Greenwood. They used medical records to evaluate the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior.

The investigators found that more than one in five (20.9%) teens endorsed any lifetime suicide ideation. This, said Mr. Greenwood, is “roughly equivalent” to the prevalence reported earlier in the adult cohort of the Human Epilepsy Project (21.6%).

‘Striking’ rate

The fact that one in five adolescents had any lifetime suicide ideation is “definitely a striking number,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers found that 15% of patients experienced active suicide ideation, 7.5% exhibited preparatory or suicidal behaviors, and 3% had made a prior suicide attempt.

All of these percentages increased at 3 years: Thirty-one percent for suicide ideation; 25% for active suicide behavior, 15% for preparatory or suicide behaviors, and 5% for prior suicide attempt.

The fact that nearly one in three adolescents endorsed suicide ideation at 3 years is another “striking” finding, said Mr. Greenwood.

Of the 53 adolescents who had never had suicide ideation at the time of enrollment, 7 endorsed new-onset suicide ideation in the follow-up period. Five of 14 who had had suicide ideation at some point prior to enrollment continued to endorse it.

“The value of the study is identifying the prevalence and identifying the significant number of adolescents with epilepsy who are endorsing either suicide ideation or suicidal behaviors,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The researchers found that among younger teens (aged 11–14 years) rates of suicide ideation were higher than among their older counterparts (aged 15–17 years).

The study does not shed light on the biological connection between epilepsy and suicidality, but Mr. Greenwood noted that prior research has suggested a bidirectional relationship.

“Depression and other psychiatric comorbidities might exist prior to epileptic activity and actually predispose to epileptic activity.”

Mr. Greenwood noted that suicide ideation has “spiked” recently across the general population, and so it’s difficult to compare the prevalence in her study with “today’s prevalence.”

However, other research generally shows that the suicide ideation rate in the general adolescent population is much lower than in teens with epilepsy.

Unique aspects of the current study are that it reports suicide ideation and behaviors at around the time of an epilepsy diagnosis and documents how suicidality progresses or resolves over time, said Mr. Greenwood.

Underdiagnosed, undertreated

Commenting on the research, Elizabeth Donner, MD, director of the comprehensive epilepsy program, Hospital for Sick Children, and associate professor, department of pediatrics, University of Toronto, said a “key point” from the study is that the suicidality rate among teens with epilepsy exceeds that of children not living with epilepsy.

“We are significantly underdiagnosing and undertreating the mental health comorbidities in epilepsy,” said Dr. Donner. “Epilepsy is a brain disease and so are mental health disorders, so it shouldn’t come as any surprise that they coexist in individuals with epilepsy.”

The new results contribute to what is already known about the significant mortality rates among persons with epilepsy, said Dr. Donner. She referred to a 2018 study that showed that people with epilepsy were 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide.

Other research has shown that people with epilepsy are 10 times more likely to die by drowning, mostly in the bathtub, said Dr. Donner.

“You would think that we’re educating these people about risks related to their epilepsy, but either the messages don’t get through, or they don’t know how to keep themselves safe,” she said.

“This needs to be seen in a bigger picture, and the bigger picture is we need to recognize comorbid mental health issues; we need to address them once recognized; and then we need to counsel and support people to live safely with their epilepsy.

The study received funding from the Epilepsy Study Consortium, Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures (FACES) and other related foundations, UCB, Pfizer, Eisai, Lundbeck, and Sunovion. Mr. Greenwood and Dr. Donner report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , new research reveals.

“We hope these results inspire epileptologists and neurologists to both recognize and screen for suicide ideation and behaviors in their adolescent patients,” said study investigator Hadley Greenwood, a third-year medical student at New York University.

The new data should also encourage providers “to become more comfortable” providing support to patients, “be that by increasing their familiarity with prescribing different antidepressants or by being well versed in how to connect patients to resources within their community,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The findings were presented here at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Little research

Previous studies have reported on the prevalence of suicidality as well as depression and anxiety among adults with epilepsy. “We wanted to look at adolescents because there’s much less in the literature out there about psychiatric comorbidity, and specifically suicidality, in this population,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers used data from the Human Epilepsy Project, a study that collected data from 34 sites in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia from 2012 to 2017.

From a cohort of more than 400 participants, researchers identified 67 patients aged 11-17 years who were enrolled within 4 months of starting treatment for focal epilepsy.

Participants completed the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) at enrollment and at follow-ups over 36 months. The C-SSRS measures suicidal ideation and severity, said Mr. Greenwood.

“It’s scaled from passive suicide ideation, such as thoughts of ‘I wish I were dead’ without active intent, all the way up to active suicidal ideation with a plan and intent.”

Researchers were able to distinguish individuals with passive suicide ideation from those with more serious intentions, said Mr. Greenwood. They used medical records to evaluate the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior.

The investigators found that more than one in five (20.9%) teens endorsed any lifetime suicide ideation. This, said Mr. Greenwood, is “roughly equivalent” to the prevalence reported earlier in the adult cohort of the Human Epilepsy Project (21.6%).

‘Striking’ rate

The fact that one in five adolescents had any lifetime suicide ideation is “definitely a striking number,” said Mr. Greenwood.

Researchers found that 15% of patients experienced active suicide ideation, 7.5% exhibited preparatory or suicidal behaviors, and 3% had made a prior suicide attempt.

All of these percentages increased at 3 years: Thirty-one percent for suicide ideation; 25% for active suicide behavior, 15% for preparatory or suicide behaviors, and 5% for prior suicide attempt.

The fact that nearly one in three adolescents endorsed suicide ideation at 3 years is another “striking” finding, said Mr. Greenwood.

Of the 53 adolescents who had never had suicide ideation at the time of enrollment, 7 endorsed new-onset suicide ideation in the follow-up period. Five of 14 who had had suicide ideation at some point prior to enrollment continued to endorse it.

“The value of the study is identifying the prevalence and identifying the significant number of adolescents with epilepsy who are endorsing either suicide ideation or suicidal behaviors,” said Mr. Greenwood.

The researchers found that among younger teens (aged 11–14 years) rates of suicide ideation were higher than among their older counterparts (aged 15–17 years).

The study does not shed light on the biological connection between epilepsy and suicidality, but Mr. Greenwood noted that prior research has suggested a bidirectional relationship.

“Depression and other psychiatric comorbidities might exist prior to epileptic activity and actually predispose to epileptic activity.”

Mr. Greenwood noted that suicide ideation has “spiked” recently across the general population, and so it’s difficult to compare the prevalence in her study with “today’s prevalence.”

However, other research generally shows that the suicide ideation rate in the general adolescent population is much lower than in teens with epilepsy.

Unique aspects of the current study are that it reports suicide ideation and behaviors at around the time of an epilepsy diagnosis and documents how suicidality progresses or resolves over time, said Mr. Greenwood.

Underdiagnosed, undertreated

Commenting on the research, Elizabeth Donner, MD, director of the comprehensive epilepsy program, Hospital for Sick Children, and associate professor, department of pediatrics, University of Toronto, said a “key point” from the study is that the suicidality rate among teens with epilepsy exceeds that of children not living with epilepsy.

“We are significantly underdiagnosing and undertreating the mental health comorbidities in epilepsy,” said Dr. Donner. “Epilepsy is a brain disease and so are mental health disorders, so it shouldn’t come as any surprise that they coexist in individuals with epilepsy.”

The new results contribute to what is already known about the significant mortality rates among persons with epilepsy, said Dr. Donner. She referred to a 2018 study that showed that people with epilepsy were 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide.

Other research has shown that people with epilepsy are 10 times more likely to die by drowning, mostly in the bathtub, said Dr. Donner.

“You would think that we’re educating these people about risks related to their epilepsy, but either the messages don’t get through, or they don’t know how to keep themselves safe,” she said.

“This needs to be seen in a bigger picture, and the bigger picture is we need to recognize comorbid mental health issues; we need to address them once recognized; and then we need to counsel and support people to live safely with their epilepsy.

The study received funding from the Epilepsy Study Consortium, Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures (FACES) and other related foundations, UCB, Pfizer, Eisai, Lundbeck, and Sunovion. Mr. Greenwood and Dr. Donner report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AES 2022

Hospital financial decisions play a role in the critical shortage of pediatric beds for RSV patients

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

A single pediatric CT scan raises brain cancer risk

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”

The study was funded through the Belgian Cancer Registry; La Ligue contre le Cancer, L’Institut National du Cancer, France; the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Worldwide Cancer Research; the Dutch Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway; Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, Generalitat deCatalunya, Spain; the U.S. National Cancer Institute; the U.K. National Institute for Health Research; and Public Health England. Dr. Hauptmann has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Other investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. Hamada and Dr. Zablotska disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”

The study was funded through the Belgian Cancer Registry; La Ligue contre le Cancer, L’Institut National du Cancer, France; the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Worldwide Cancer Research; the Dutch Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway; Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, Generalitat deCatalunya, Spain; the U.S. National Cancer Institute; the U.K. National Institute for Health Research; and Public Health England. Dr. Hauptmann has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Other investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. Hamada and Dr. Zablotska disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”