User login

How prevalent is pediatric melanoma?

SAN DIEGO – When parents bring their children to Caroline Piggott, MD, to evaluate a suspicious mole on the scalp or other body location, the vast majority turn out to be benign, because the incidence of melanoma is rare, especially before puberty.

“Only 1%-2% of all melanomas in the world are in children, so most of my job is to provide reassurance,” Dr. Piggott, a pediatric dermatologist at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “

To help parents identify melanoma, clinicians typically recommend the “ABCDE” rule, for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation (especially dark or multiple colors), Diameter greater than 6 mm, and Evolving (is it changing, bleeding or painful?).

While Dr. Piggott considers the standard ABCDE rules as important – especially in older children and teenagers – researchers led by Kelly M. Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, proposed a modified ABCD criteria based on evaluating a cohort of 60 children who were diagnosed with melanoma and 10 who were diagnosed with ambiguous melanocytic tumors treated as melanoma before age 20 years at UCSF from 1984 to 2009.

The researchers divided patients into two groups: those aged 0-10 years (19; group A) and those aged 11-19 years (51; group B), and found that 60% of children in group A and 40% of those in group B did not present with conventional ABCDE criteria for children. Of the 60 melanoma patients, 10 died. Of these, 9 were older than age 10, and 70% had amelanotic lesions. Based on their analysis of clinical, histopathologic, and outcomes data, Dr. Cordoro and colleagues proposed additional ABCD criteria in which A stands for stands Amelanotic; B for Bleeding or Bump; C for Color uniformity, and D for De novo or any Diameter.

“This doesn’t mean you throw the old ABCDE criteria out the window,” Dr. Piggott said. “It means that you use this modified criteria in conjunction with the conventional ABCDE rules.”

Risk factors for melanoma in children are like those in adults, and include a family history of melanoma, large/giant congenital nevi, the presence of many atypical appearing nevi, having Fitzpatrick skin types I or II, a history of blistering sunburns, and the presence of genetic anomalies such as xeroderma pigmentosum.

According to an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, melanoma incidence increased in all individuals in the United States aged 0-19 years from 1973 to 2009. Key risk factors included White race, female sex, and living in a SEER registry categorized as low UVB exposure. Over the study period, boys experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the face and trunk, while girls experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the lower limbs and hip.

More recently, researchers extracted data from 988,103 cases of invasive melanoma in the 2001-2015 SEER database to determine the age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. In 2015, 83,362 cases of invasive melanoma were reported for all ages. Of these, only 67 cases were younger than age 10, while 251 were between the ages of 10 and 19 and 1,973 were young adults between the ages of 20 and 29.

In other findings, between 2006 and 2015, the overall incidence of invasive melanoma for all ages increased from 200 million to 229 cases per million person-years. “However, there were statistically significant decreases in melanoma incidence for individuals aged 10-19 years and for those aged 10-29 years,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved with the study. “The hypothesis is that public health efforts encouraging against sun exposure and tanning bed use may be influencing melanoma incidence in younger populations. What is interesting, though, is that young adult women have twice the melanoma risk as young adult men.”

In a separate study, researchers prospectively followed 60 melanoma-prone families for up to 40 years to evaluate the risk of pediatric melanoma in those with and without cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) mutations. Regardless of their CDKN2A status, the percentage of pediatric melanoma cases was 6- to 28-fold higher among melanoma-prone families, compared with the general population. In addition, families who were CDKN2A positive had a significantly higher rate of pediatric melanoma cases compared with those who were CDKN2A negative (11.1% vs. 2.5%; P = .004).

As for treating pediatric melanoma, the standard of care is similar to that for adults: usually wide local surgical excision of the primary lesion, depending on depth. Clinicians typically follow adult parameters for sentinel lymph node biopsy, such as lesion depth and ulceration.

“We know that a positive sentinel node does have prognostic value, but there is great debate on whether to do a lymph node dissection if the sentinel lymph node is positive,” Dr. Piggott said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “This is determined on a case-by-case basis. We consider factors such as, are the nodes palpable? Is there evidence on ultrasound? But there are no formal guidelines.”

Limited studies of systemic therapy in children exist because this population is excluded from most melanoma clinical trials. “In the past, interferon was sometimes used,” she said. “But in recent years, as with adults, we have started to use targeted immunologic therapy. This is usually managed by a tertiary academic oncology center.”

The chance of surviving pediatric melanoma is good if caught early. As in adults, the stage correlates strongly with survival, and distant metastases carry a poor prognosis.

In 2020, researchers published a retrospective, multicenter review of 38 cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 1994 and 2017. The analysis was limited to individuals 20 years of age and younger who were cared for at 12 academic medical centers. Of the 38 patients, 42% were male, 58% were female, and 57% were White. In addition, 19% were Hispanic, “which is a larger percentage than fatalities in adult [Hispanic] populations with melanoma,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved in the study.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, the mean age at death was 15.6 , and the mean survival time after diagnosis was about 35 months. Of the 16 cases with known identifiable subtypes, 50% were nodular, 31% were superficial spreading, and 19% were spitzoid melanoma. In addition, one-quarter of melanomas arose in association with congenital melanocytic nevi.

“The good news is that there are only 38 total cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 12 academic centers over a 23-year period,” Dr. Piggott said. “Thanks goodness the number is that low.”

Dr. Piggott reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – When parents bring their children to Caroline Piggott, MD, to evaluate a suspicious mole on the scalp or other body location, the vast majority turn out to be benign, because the incidence of melanoma is rare, especially before puberty.

“Only 1%-2% of all melanomas in the world are in children, so most of my job is to provide reassurance,” Dr. Piggott, a pediatric dermatologist at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “

To help parents identify melanoma, clinicians typically recommend the “ABCDE” rule, for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation (especially dark or multiple colors), Diameter greater than 6 mm, and Evolving (is it changing, bleeding or painful?).

While Dr. Piggott considers the standard ABCDE rules as important – especially in older children and teenagers – researchers led by Kelly M. Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, proposed a modified ABCD criteria based on evaluating a cohort of 60 children who were diagnosed with melanoma and 10 who were diagnosed with ambiguous melanocytic tumors treated as melanoma before age 20 years at UCSF from 1984 to 2009.

The researchers divided patients into two groups: those aged 0-10 years (19; group A) and those aged 11-19 years (51; group B), and found that 60% of children in group A and 40% of those in group B did not present with conventional ABCDE criteria for children. Of the 60 melanoma patients, 10 died. Of these, 9 were older than age 10, and 70% had amelanotic lesions. Based on their analysis of clinical, histopathologic, and outcomes data, Dr. Cordoro and colleagues proposed additional ABCD criteria in which A stands for stands Amelanotic; B for Bleeding or Bump; C for Color uniformity, and D for De novo or any Diameter.

“This doesn’t mean you throw the old ABCDE criteria out the window,” Dr. Piggott said. “It means that you use this modified criteria in conjunction with the conventional ABCDE rules.”

Risk factors for melanoma in children are like those in adults, and include a family history of melanoma, large/giant congenital nevi, the presence of many atypical appearing nevi, having Fitzpatrick skin types I or II, a history of blistering sunburns, and the presence of genetic anomalies such as xeroderma pigmentosum.

According to an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, melanoma incidence increased in all individuals in the United States aged 0-19 years from 1973 to 2009. Key risk factors included White race, female sex, and living in a SEER registry categorized as low UVB exposure. Over the study period, boys experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the face and trunk, while girls experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the lower limbs and hip.

More recently, researchers extracted data from 988,103 cases of invasive melanoma in the 2001-2015 SEER database to determine the age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. In 2015, 83,362 cases of invasive melanoma were reported for all ages. Of these, only 67 cases were younger than age 10, while 251 were between the ages of 10 and 19 and 1,973 were young adults between the ages of 20 and 29.

In other findings, between 2006 and 2015, the overall incidence of invasive melanoma for all ages increased from 200 million to 229 cases per million person-years. “However, there were statistically significant decreases in melanoma incidence for individuals aged 10-19 years and for those aged 10-29 years,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved with the study. “The hypothesis is that public health efforts encouraging against sun exposure and tanning bed use may be influencing melanoma incidence in younger populations. What is interesting, though, is that young adult women have twice the melanoma risk as young adult men.”

In a separate study, researchers prospectively followed 60 melanoma-prone families for up to 40 years to evaluate the risk of pediatric melanoma in those with and without cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) mutations. Regardless of their CDKN2A status, the percentage of pediatric melanoma cases was 6- to 28-fold higher among melanoma-prone families, compared with the general population. In addition, families who were CDKN2A positive had a significantly higher rate of pediatric melanoma cases compared with those who were CDKN2A negative (11.1% vs. 2.5%; P = .004).

As for treating pediatric melanoma, the standard of care is similar to that for adults: usually wide local surgical excision of the primary lesion, depending on depth. Clinicians typically follow adult parameters for sentinel lymph node biopsy, such as lesion depth and ulceration.

“We know that a positive sentinel node does have prognostic value, but there is great debate on whether to do a lymph node dissection if the sentinel lymph node is positive,” Dr. Piggott said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “This is determined on a case-by-case basis. We consider factors such as, are the nodes palpable? Is there evidence on ultrasound? But there are no formal guidelines.”

Limited studies of systemic therapy in children exist because this population is excluded from most melanoma clinical trials. “In the past, interferon was sometimes used,” she said. “But in recent years, as with adults, we have started to use targeted immunologic therapy. This is usually managed by a tertiary academic oncology center.”

The chance of surviving pediatric melanoma is good if caught early. As in adults, the stage correlates strongly with survival, and distant metastases carry a poor prognosis.

In 2020, researchers published a retrospective, multicenter review of 38 cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 1994 and 2017. The analysis was limited to individuals 20 years of age and younger who were cared for at 12 academic medical centers. Of the 38 patients, 42% were male, 58% were female, and 57% were White. In addition, 19% were Hispanic, “which is a larger percentage than fatalities in adult [Hispanic] populations with melanoma,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved in the study.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, the mean age at death was 15.6 , and the mean survival time after diagnosis was about 35 months. Of the 16 cases with known identifiable subtypes, 50% were nodular, 31% were superficial spreading, and 19% were spitzoid melanoma. In addition, one-quarter of melanomas arose in association with congenital melanocytic nevi.

“The good news is that there are only 38 total cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 12 academic centers over a 23-year period,” Dr. Piggott said. “Thanks goodness the number is that low.”

Dr. Piggott reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – When parents bring their children to Caroline Piggott, MD, to evaluate a suspicious mole on the scalp or other body location, the vast majority turn out to be benign, because the incidence of melanoma is rare, especially before puberty.

“Only 1%-2% of all melanomas in the world are in children, so most of my job is to provide reassurance,” Dr. Piggott, a pediatric dermatologist at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Diego, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “

To help parents identify melanoma, clinicians typically recommend the “ABCDE” rule, for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation (especially dark or multiple colors), Diameter greater than 6 mm, and Evolving (is it changing, bleeding or painful?).

While Dr. Piggott considers the standard ABCDE rules as important – especially in older children and teenagers – researchers led by Kelly M. Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, proposed a modified ABCD criteria based on evaluating a cohort of 60 children who were diagnosed with melanoma and 10 who were diagnosed with ambiguous melanocytic tumors treated as melanoma before age 20 years at UCSF from 1984 to 2009.

The researchers divided patients into two groups: those aged 0-10 years (19; group A) and those aged 11-19 years (51; group B), and found that 60% of children in group A and 40% of those in group B did not present with conventional ABCDE criteria for children. Of the 60 melanoma patients, 10 died. Of these, 9 were older than age 10, and 70% had amelanotic lesions. Based on their analysis of clinical, histopathologic, and outcomes data, Dr. Cordoro and colleagues proposed additional ABCD criteria in which A stands for stands Amelanotic; B for Bleeding or Bump; C for Color uniformity, and D for De novo or any Diameter.

“This doesn’t mean you throw the old ABCDE criteria out the window,” Dr. Piggott said. “It means that you use this modified criteria in conjunction with the conventional ABCDE rules.”

Risk factors for melanoma in children are like those in adults, and include a family history of melanoma, large/giant congenital nevi, the presence of many atypical appearing nevi, having Fitzpatrick skin types I or II, a history of blistering sunburns, and the presence of genetic anomalies such as xeroderma pigmentosum.

According to an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, melanoma incidence increased in all individuals in the United States aged 0-19 years from 1973 to 2009. Key risk factors included White race, female sex, and living in a SEER registry categorized as low UVB exposure. Over the study period, boys experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the face and trunk, while girls experienced increased incidence rates of melanoma on the lower limbs and hip.

More recently, researchers extracted data from 988,103 cases of invasive melanoma in the 2001-2015 SEER database to determine the age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. In 2015, 83,362 cases of invasive melanoma were reported for all ages. Of these, only 67 cases were younger than age 10, while 251 were between the ages of 10 and 19 and 1,973 were young adults between the ages of 20 and 29.

In other findings, between 2006 and 2015, the overall incidence of invasive melanoma for all ages increased from 200 million to 229 cases per million person-years. “However, there were statistically significant decreases in melanoma incidence for individuals aged 10-19 years and for those aged 10-29 years,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved with the study. “The hypothesis is that public health efforts encouraging against sun exposure and tanning bed use may be influencing melanoma incidence in younger populations. What is interesting, though, is that young adult women have twice the melanoma risk as young adult men.”

In a separate study, researchers prospectively followed 60 melanoma-prone families for up to 40 years to evaluate the risk of pediatric melanoma in those with and without cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) mutations. Regardless of their CDKN2A status, the percentage of pediatric melanoma cases was 6- to 28-fold higher among melanoma-prone families, compared with the general population. In addition, families who were CDKN2A positive had a significantly higher rate of pediatric melanoma cases compared with those who were CDKN2A negative (11.1% vs. 2.5%; P = .004).

As for treating pediatric melanoma, the standard of care is similar to that for adults: usually wide local surgical excision of the primary lesion, depending on depth. Clinicians typically follow adult parameters for sentinel lymph node biopsy, such as lesion depth and ulceration.

“We know that a positive sentinel node does have prognostic value, but there is great debate on whether to do a lymph node dissection if the sentinel lymph node is positive,” Dr. Piggott said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “This is determined on a case-by-case basis. We consider factors such as, are the nodes palpable? Is there evidence on ultrasound? But there are no formal guidelines.”

Limited studies of systemic therapy in children exist because this population is excluded from most melanoma clinical trials. “In the past, interferon was sometimes used,” she said. “But in recent years, as with adults, we have started to use targeted immunologic therapy. This is usually managed by a tertiary academic oncology center.”

The chance of surviving pediatric melanoma is good if caught early. As in adults, the stage correlates strongly with survival, and distant metastases carry a poor prognosis.

In 2020, researchers published a retrospective, multicenter review of 38 cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 1994 and 2017. The analysis was limited to individuals 20 years of age and younger who were cared for at 12 academic medical centers. Of the 38 patients, 42% were male, 58% were female, and 57% were White. In addition, 19% were Hispanic, “which is a larger percentage than fatalities in adult [Hispanic] populations with melanoma,” said Dr. Piggott, who was not involved in the study.

The mean age at diagnosis was 12.7 years, the mean age at death was 15.6 , and the mean survival time after diagnosis was about 35 months. Of the 16 cases with known identifiable subtypes, 50% were nodular, 31% were superficial spreading, and 19% were spitzoid melanoma. In addition, one-quarter of melanomas arose in association with congenital melanocytic nevi.

“The good news is that there are only 38 total cases of fatal pediatric melanoma between 12 academic centers over a 23-year period,” Dr. Piggott said. “Thanks goodness the number is that low.”

Dr. Piggott reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT MELANOMA 2023

Immunodeficiencies tied to psychiatric disorders in offspring

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

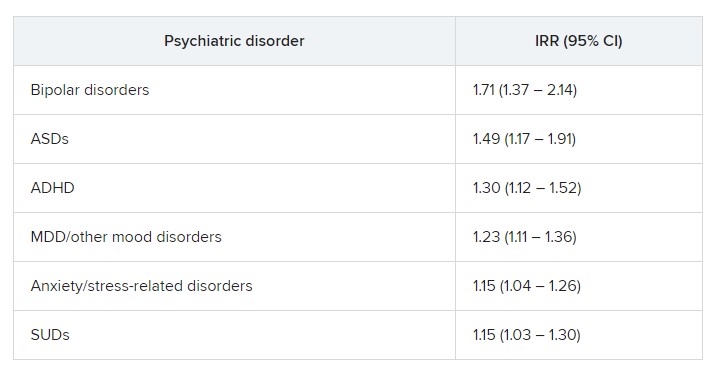

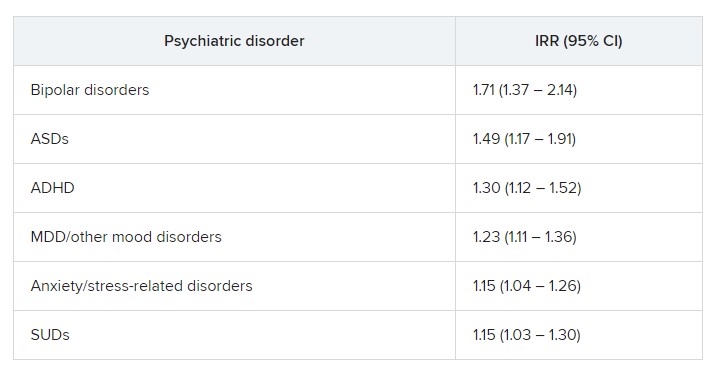

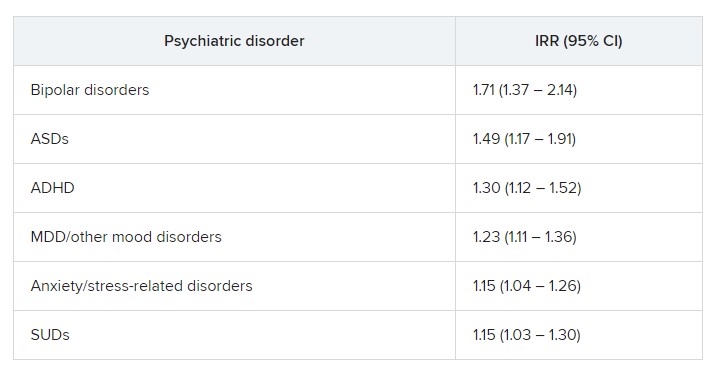

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Eye drops delay, may even prevent, nearsightedness

Dilating eye drops may delay – and perhaps even prevent – the onset of myopia in children, according to findings from a study published in JAMA. The study was conducted by researchers in Hong Kong.

Myopia is irreversible once it takes root and can contribute to other vision problems, such as macular degeneration, retinal detachment, glaucoma, and cataracts. The incidence of nearsightedness has nearly doubled since the 1970s, rising from 25% of the U.S. population to nearly 42%. Children have been particularly affected by the increase; reasons may include spending more time indoors looking at screens, experts say.

“Myopia is an ongoing and growing worldwide concern. This is of particular importance because of the change in children’s lifestyle, such as decreased outdoor time and increased screen time during and after the COVID-19 pandemic,” Jason C. Yam, MPH, of the department of ophthalmology and visual services at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said in an interview.

Mr. Yam said that, while encouraging children to engage more in outdoor activity and spend less time using screens would help delay myopia, pharmaceutical interventions are needed, given myopia’s potential lifelong effects.

Putting eye drops to the test

In 2020, Mr. Yam and colleagues reported results of the Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study, which showed that eye drops containing a solution of 0.05% atropine worked best at slowing the progression of myopia in 4- to 12-year-olds who already had the condition. Atropine relaxes eye muscles, causing dilation.

In that study, Mr. Yam and colleagues measured the rate of change in the eye’s ability to see at a great distance using a unit of measure known as the diopter. The higher the diopter, the more myopic a person’s vision. The 0.05% atropine solution was better at slowing this decline than placebo or solutions that contained a lower concentration of the substance.

The new study enrolled 474 children who were evenly divided by sex. None of the children had myopia when the trial began. Of that starting group, 353 children (age, 4-9 years) completed the study, which involved receiving eye drops once nightly in both eyes for 2 years.

Some children (n = 116) received 0.05% atropine, others (n = 122) received 0.01% atropine, and the rest (n = 115) received placebo drops. Mr. Yam and colleagues assessed how many children in each group had myopia after 2 years, as measured by a decline of at least a half diopter in one eye.

At the 2-year mark, more than half of children who received the placebo drops (61/115) had developed myopia, as had nearly half of those given 0.01% atropine (56/122). But fewer than one-third of children (33/116, 28.4%) who had received the drops with 0.05% atropine developed myopia during that period, the researchers reported.

The percentage of children with myopia in the placebo group (39/128, 30.5%) was larger by the end of the first year of the study than was the share of children in the 0.05% atropine group by the end of the trial. (Between 12 months and 24 months, 13 children in the placebo group left the study.) The main adverse event, in all treatment groups, was discomfort when exposed to bright light, according to the researchers.

“We are continuing the current study with the total intended follow-up duration of at least 6years,” added Mr. Yam, who hopes to determine whether the 0.05% atropine solution not only delays myopia but also prevents it altogether. While myopia is a concern worldwide, the condition is particularly prevalent in East Asia.

Mark A. Bullimore, MCOptom, PhD, FAAO, an adjunct professor at the University of Houston, and a consultant to ophthalmologic companies, called the trial “a landmark study. Finding children who are eligible and parents who are willing to deal with 2 years of drops is no small feat.

“The 0.05% atropine, on average, delays onset of myopia by a year,” Dr. Bullimore noted. He pointed to the similar percentages of myopia with placebo at 12 months, compared with 0.05% atropine 1 year later. He added that few clinicians in the United States use higher than 0.05% atropine for control of myopia because doing so can lead to excessive dilation and difficulty focusing.

While preventing myopia altogether would be ideal, simply delaying its onset can also be of tangible benefit, Bullimore said. In an article published in January, Dr. Bullimore and Noel A. Brennan of Johnson & Johnson Vision showed that delaying the onset of myopia reduces its severity.

“Optometrists prescribe low-concentration atropine already for myopia control, and there’s no reason now – in the light of this study – that they wouldn’t also do it to delay onset,” Dr. Bullimore said.

But in an editorial accompanying the journal article David A. Berntsen, OD, PhD, and Jeffrey J. Walline, OD, PhD, both of the University of Houston, wrote that a change in practice would be premature.

“The evidence presented does not yet warrant a change in the standard care of children because we do not yet know the long-term effects of delaying the onset of myopia with low-concentration atropine,” they wrote.

Identifying which children to consider for treatment is “a challenge,” they noted, because those who are not nearsighted typically do not undergo routine examination unless they have failed a vision test.

“Ultimately, the implementation of vision screenings that include determining a child’s prescription will likely be needed to identify children most likely to become myopic who may benefit from low-concentration atropine,” Dr. Berntsen and Dr. Walline wrote.

Mr. Yam and coinvestigators have applied for a patent on a 0.05% atropine solution. Dr. Bullimore reported relationships with Alcon Research,CooperVision, CorneaGen, EssilorLuxottica, Eyenovia, Genentech, Johnson & Johnson Vision, Lentechs, Novartis, and Vyluma, and is the sole owner of Ridgevue Publishing and Ridgevue Vision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dilating eye drops may delay – and perhaps even prevent – the onset of myopia in children, according to findings from a study published in JAMA. The study was conducted by researchers in Hong Kong.

Myopia is irreversible once it takes root and can contribute to other vision problems, such as macular degeneration, retinal detachment, glaucoma, and cataracts. The incidence of nearsightedness has nearly doubled since the 1970s, rising from 25% of the U.S. population to nearly 42%. Children have been particularly affected by the increase; reasons may include spending more time indoors looking at screens, experts say.

“Myopia is an ongoing and growing worldwide concern. This is of particular importance because of the change in children’s lifestyle, such as decreased outdoor time and increased screen time during and after the COVID-19 pandemic,” Jason C. Yam, MPH, of the department of ophthalmology and visual services at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said in an interview.

Mr. Yam said that, while encouraging children to engage more in outdoor activity and spend less time using screens would help delay myopia, pharmaceutical interventions are needed, given myopia’s potential lifelong effects.

Putting eye drops to the test

In 2020, Mr. Yam and colleagues reported results of the Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study, which showed that eye drops containing a solution of 0.05% atropine worked best at slowing the progression of myopia in 4- to 12-year-olds who already had the condition. Atropine relaxes eye muscles, causing dilation.

In that study, Mr. Yam and colleagues measured the rate of change in the eye’s ability to see at a great distance using a unit of measure known as the diopter. The higher the diopter, the more myopic a person’s vision. The 0.05% atropine solution was better at slowing this decline than placebo or solutions that contained a lower concentration of the substance.

The new study enrolled 474 children who were evenly divided by sex. None of the children had myopia when the trial began. Of that starting group, 353 children (age, 4-9 years) completed the study, which involved receiving eye drops once nightly in both eyes for 2 years.

Some children (n = 116) received 0.05% atropine, others (n = 122) received 0.01% atropine, and the rest (n = 115) received placebo drops. Mr. Yam and colleagues assessed how many children in each group had myopia after 2 years, as measured by a decline of at least a half diopter in one eye.

At the 2-year mark, more than half of children who received the placebo drops (61/115) had developed myopia, as had nearly half of those given 0.01% atropine (56/122). But fewer than one-third of children (33/116, 28.4%) who had received the drops with 0.05% atropine developed myopia during that period, the researchers reported.

The percentage of children with myopia in the placebo group (39/128, 30.5%) was larger by the end of the first year of the study than was the share of children in the 0.05% atropine group by the end of the trial. (Between 12 months and 24 months, 13 children in the placebo group left the study.) The main adverse event, in all treatment groups, was discomfort when exposed to bright light, according to the researchers.

“We are continuing the current study with the total intended follow-up duration of at least 6years,” added Mr. Yam, who hopes to determine whether the 0.05% atropine solution not only delays myopia but also prevents it altogether. While myopia is a concern worldwide, the condition is particularly prevalent in East Asia.

Mark A. Bullimore, MCOptom, PhD, FAAO, an adjunct professor at the University of Houston, and a consultant to ophthalmologic companies, called the trial “a landmark study. Finding children who are eligible and parents who are willing to deal with 2 years of drops is no small feat.

“The 0.05% atropine, on average, delays onset of myopia by a year,” Dr. Bullimore noted. He pointed to the similar percentages of myopia with placebo at 12 months, compared with 0.05% atropine 1 year later. He added that few clinicians in the United States use higher than 0.05% atropine for control of myopia because doing so can lead to excessive dilation and difficulty focusing.

While preventing myopia altogether would be ideal, simply delaying its onset can also be of tangible benefit, Bullimore said. In an article published in January, Dr. Bullimore and Noel A. Brennan of Johnson & Johnson Vision showed that delaying the onset of myopia reduces its severity.

“Optometrists prescribe low-concentration atropine already for myopia control, and there’s no reason now – in the light of this study – that they wouldn’t also do it to delay onset,” Dr. Bullimore said.

But in an editorial accompanying the journal article David A. Berntsen, OD, PhD, and Jeffrey J. Walline, OD, PhD, both of the University of Houston, wrote that a change in practice would be premature.

“The evidence presented does not yet warrant a change in the standard care of children because we do not yet know the long-term effects of delaying the onset of myopia with low-concentration atropine,” they wrote.

Identifying which children to consider for treatment is “a challenge,” they noted, because those who are not nearsighted typically do not undergo routine examination unless they have failed a vision test.

“Ultimately, the implementation of vision screenings that include determining a child’s prescription will likely be needed to identify children most likely to become myopic who may benefit from low-concentration atropine,” Dr. Berntsen and Dr. Walline wrote.

Mr. Yam and coinvestigators have applied for a patent on a 0.05% atropine solution. Dr. Bullimore reported relationships with Alcon Research,CooperVision, CorneaGen, EssilorLuxottica, Eyenovia, Genentech, Johnson & Johnson Vision, Lentechs, Novartis, and Vyluma, and is the sole owner of Ridgevue Publishing and Ridgevue Vision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dilating eye drops may delay – and perhaps even prevent – the onset of myopia in children, according to findings from a study published in JAMA. The study was conducted by researchers in Hong Kong.

Myopia is irreversible once it takes root and can contribute to other vision problems, such as macular degeneration, retinal detachment, glaucoma, and cataracts. The incidence of nearsightedness has nearly doubled since the 1970s, rising from 25% of the U.S. population to nearly 42%. Children have been particularly affected by the increase; reasons may include spending more time indoors looking at screens, experts say.

“Myopia is an ongoing and growing worldwide concern. This is of particular importance because of the change in children’s lifestyle, such as decreased outdoor time and increased screen time during and after the COVID-19 pandemic,” Jason C. Yam, MPH, of the department of ophthalmology and visual services at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said in an interview.

Mr. Yam said that, while encouraging children to engage more in outdoor activity and spend less time using screens would help delay myopia, pharmaceutical interventions are needed, given myopia’s potential lifelong effects.

Putting eye drops to the test

In 2020, Mr. Yam and colleagues reported results of the Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study, which showed that eye drops containing a solution of 0.05% atropine worked best at slowing the progression of myopia in 4- to 12-year-olds who already had the condition. Atropine relaxes eye muscles, causing dilation.

In that study, Mr. Yam and colleagues measured the rate of change in the eye’s ability to see at a great distance using a unit of measure known as the diopter. The higher the diopter, the more myopic a person’s vision. The 0.05% atropine solution was better at slowing this decline than placebo or solutions that contained a lower concentration of the substance.

The new study enrolled 474 children who were evenly divided by sex. None of the children had myopia when the trial began. Of that starting group, 353 children (age, 4-9 years) completed the study, which involved receiving eye drops once nightly in both eyes for 2 years.

Some children (n = 116) received 0.05% atropine, others (n = 122) received 0.01% atropine, and the rest (n = 115) received placebo drops. Mr. Yam and colleagues assessed how many children in each group had myopia after 2 years, as measured by a decline of at least a half diopter in one eye.

At the 2-year mark, more than half of children who received the placebo drops (61/115) had developed myopia, as had nearly half of those given 0.01% atropine (56/122). But fewer than one-third of children (33/116, 28.4%) who had received the drops with 0.05% atropine developed myopia during that period, the researchers reported.

The percentage of children with myopia in the placebo group (39/128, 30.5%) was larger by the end of the first year of the study than was the share of children in the 0.05% atropine group by the end of the trial. (Between 12 months and 24 months, 13 children in the placebo group left the study.) The main adverse event, in all treatment groups, was discomfort when exposed to bright light, according to the researchers.

“We are continuing the current study with the total intended follow-up duration of at least 6years,” added Mr. Yam, who hopes to determine whether the 0.05% atropine solution not only delays myopia but also prevents it altogether. While myopia is a concern worldwide, the condition is particularly prevalent in East Asia.

Mark A. Bullimore, MCOptom, PhD, FAAO, an adjunct professor at the University of Houston, and a consultant to ophthalmologic companies, called the trial “a landmark study. Finding children who are eligible and parents who are willing to deal with 2 years of drops is no small feat.

“The 0.05% atropine, on average, delays onset of myopia by a year,” Dr. Bullimore noted. He pointed to the similar percentages of myopia with placebo at 12 months, compared with 0.05% atropine 1 year later. He added that few clinicians in the United States use higher than 0.05% atropine for control of myopia because doing so can lead to excessive dilation and difficulty focusing.

While preventing myopia altogether would be ideal, simply delaying its onset can also be of tangible benefit, Bullimore said. In an article published in January, Dr. Bullimore and Noel A. Brennan of Johnson & Johnson Vision showed that delaying the onset of myopia reduces its severity.

“Optometrists prescribe low-concentration atropine already for myopia control, and there’s no reason now – in the light of this study – that they wouldn’t also do it to delay onset,” Dr. Bullimore said.

But in an editorial accompanying the journal article David A. Berntsen, OD, PhD, and Jeffrey J. Walline, OD, PhD, both of the University of Houston, wrote that a change in practice would be premature.

“The evidence presented does not yet warrant a change in the standard care of children because we do not yet know the long-term effects of delaying the onset of myopia with low-concentration atropine,” they wrote.

Identifying which children to consider for treatment is “a challenge,” they noted, because those who are not nearsighted typically do not undergo routine examination unless they have failed a vision test.

“Ultimately, the implementation of vision screenings that include determining a child’s prescription will likely be needed to identify children most likely to become myopic who may benefit from low-concentration atropine,” Dr. Berntsen and Dr. Walline wrote.

Mr. Yam and coinvestigators have applied for a patent on a 0.05% atropine solution. Dr. Bullimore reported relationships with Alcon Research,CooperVision, CorneaGen, EssilorLuxottica, Eyenovia, Genentech, Johnson & Johnson Vision, Lentechs, Novartis, and Vyluma, and is the sole owner of Ridgevue Publishing and Ridgevue Vision.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Using devices to calm children can backfire long term

according to developmental behavioral pediatricians at University of Michigan Health C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor.

What to know

- Using a mobile device to distract children from how they are feeling may displace opportunities for them to develop independent, alternative methods to self-regulate, especially in early childhood.

- Signs of increased dysregulation could include rapid shifts between sadness and excitement, a sudden change in mood or feelings, and heightened impulsivity.

- The association between device-calming and emotional consequences may be particularly high among young boys and children who are already experiencing hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and a strong temperament that makes them more likely to react intensely to feelings such as anger, frustration, and sadness.

- While occasional use of media to occupy children is expected and understandable, it is important that it not become a primary or regular soothing tool, and children should be given clear expectations of when and where devices can be used.

- The preschool-to-kindergarten period is a developmental stage in which children may be more likely to exhibit difficult behaviors, such as tantrums, defiance, and intense emotions, but parents should resist using devices as a parenting strategy.

This is a summary of the article, “Longitudinal Association Between Use of Mobile Devices for Calming and Emotional Reactivity and Executive Functioning in Children Aged 3 to 5 Years,” published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 20, 2022. The full article can be found on jamanetwork.com. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to developmental behavioral pediatricians at University of Michigan Health C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor.

What to know

- Using a mobile device to distract children from how they are feeling may displace opportunities for them to develop independent, alternative methods to self-regulate, especially in early childhood.

- Signs of increased dysregulation could include rapid shifts between sadness and excitement, a sudden change in mood or feelings, and heightened impulsivity.

- The association between device-calming and emotional consequences may be particularly high among young boys and children who are already experiencing hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and a strong temperament that makes them more likely to react intensely to feelings such as anger, frustration, and sadness.

- While occasional use of media to occupy children is expected and understandable, it is important that it not become a primary or regular soothing tool, and children should be given clear expectations of when and where devices can be used.

- The preschool-to-kindergarten period is a developmental stage in which children may be more likely to exhibit difficult behaviors, such as tantrums, defiance, and intense emotions, but parents should resist using devices as a parenting strategy.

This is a summary of the article, “Longitudinal Association Between Use of Mobile Devices for Calming and Emotional Reactivity and Executive Functioning in Children Aged 3 to 5 Years,” published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 20, 2022. The full article can be found on jamanetwork.com. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to developmental behavioral pediatricians at University of Michigan Health C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor.

What to know

- Using a mobile device to distract children from how they are feeling may displace opportunities for them to develop independent, alternative methods to self-regulate, especially in early childhood.

- Signs of increased dysregulation could include rapid shifts between sadness and excitement, a sudden change in mood or feelings, and heightened impulsivity.

- The association between device-calming and emotional consequences may be particularly high among young boys and children who are already experiencing hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and a strong temperament that makes them more likely to react intensely to feelings such as anger, frustration, and sadness.

- While occasional use of media to occupy children is expected and understandable, it is important that it not become a primary or regular soothing tool, and children should be given clear expectations of when and where devices can be used.

- The preschool-to-kindergarten period is a developmental stage in which children may be more likely to exhibit difficult behaviors, such as tantrums, defiance, and intense emotions, but parents should resist using devices as a parenting strategy.

This is a summary of the article, “Longitudinal Association Between Use of Mobile Devices for Calming and Emotional Reactivity and Executive Functioning in Children Aged 3 to 5 Years,” published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 20, 2022. The full article can be found on jamanetwork.com. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Teen girls report record levels of sadness, sexual violence: CDC

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)

The survey also found an alarming spike in sexual violence toward teenage girls. Nearly one in five females (18%) experienced sexual violence in the past year, a 20% increase from 2017. More than 1 in 10 teen girls (14%) said they had been forced to have sex, according to the researchers.

Rates of sexual violence was even higher in LGBQ+ teens. Nearly two in five teens with a partner of the same sex (39%) experienced sexual violence, and 37% reported being sexually assaulted. More than one in five LGBQ+ teens (22%) had experienced sexual violence, and 20% said they had been forced to have sex, the report found.

Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaskan Native and multiracial students were more likely to experience sexual violence. The percentage of White students reporting sexual violence increased from 2017 to 2021, but that trend was not observed in other racial and ethnic groups.

Delaney Ruston, MD, an internal medicine specialist in Seattle and creator of “Screenagers,” a 2016 documentary about how technology affects youth, said excessive exposure to social media can compound feelings of depression in teens – particularly, but not only, girls. “They can scroll and consume media for hours, and rather than do activities and have interactions that would help heal from depression symptoms, they stay stuck,” Ruston said in an interview. “As a primary care physician working with teens, this is an extremely common problem I see in my clinic.”

One approach that can help, Dr. Ruston added, is behavioral activation. “This is a strategy where you get them, usually with the support of other people, to do small activities that help to reset brain reward pathways so they start to experience doses of well-being and hope that eventually reverses the depression. Being stuck on screens prevents these healing actions from happening.”

The report also emphasized the importance of school-based services to support students and combat these troubling trends in worsening mental health. “Schools are the gateway to needed services for many young people,” the report stated. “Schools can provide health, behavioral, and mental health services directly or establish referral systems to connect to community sources of care.”

“Young people are experiencing a level of distress that calls on us to act with urgency and compassion,” Kathleen Ethier, PhD, director of the CDC’s division of adolescent and school health, added in a statement. “With the right programs and services in place, schools have the unique ability to help our youth flourish.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)

The survey also found an alarming spike in sexual violence toward teenage girls. Nearly one in five females (18%) experienced sexual violence in the past year, a 20% increase from 2017. More than 1 in 10 teen girls (14%) said they had been forced to have sex, according to the researchers.

Rates of sexual violence was even higher in LGBQ+ teens. Nearly two in five teens with a partner of the same sex (39%) experienced sexual violence, and 37% reported being sexually assaulted. More than one in five LGBQ+ teens (22%) had experienced sexual violence, and 20% said they had been forced to have sex, the report found.

Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaskan Native and multiracial students were more likely to experience sexual violence. The percentage of White students reporting sexual violence increased from 2017 to 2021, but that trend was not observed in other racial and ethnic groups.

Delaney Ruston, MD, an internal medicine specialist in Seattle and creator of “Screenagers,” a 2016 documentary about how technology affects youth, said excessive exposure to social media can compound feelings of depression in teens – particularly, but not only, girls. “They can scroll and consume media for hours, and rather than do activities and have interactions that would help heal from depression symptoms, they stay stuck,” Ruston said in an interview. “As a primary care physician working with teens, this is an extremely common problem I see in my clinic.”

One approach that can help, Dr. Ruston added, is behavioral activation. “This is a strategy where you get them, usually with the support of other people, to do small activities that help to reset brain reward pathways so they start to experience doses of well-being and hope that eventually reverses the depression. Being stuck on screens prevents these healing actions from happening.”

The report also emphasized the importance of school-based services to support students and combat these troubling trends in worsening mental health. “Schools are the gateway to needed services for many young people,” the report stated. “Schools can provide health, behavioral, and mental health services directly or establish referral systems to connect to community sources of care.”

“Young people are experiencing a level of distress that calls on us to act with urgency and compassion,” Kathleen Ethier, PhD, director of the CDC’s division of adolescent and school health, added in a statement. “With the right programs and services in place, schools have the unique ability to help our youth flourish.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)