User login

FDA okays drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in patients as young as age 2 years, the company has announced Vamorolone is a structurally unique steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that potently inhibits proinflammatory NFkB pathways via high-affinity binding to the glucocorticoid receptor.

“Corticosteroids have been a first line treatment for DMD for many years, but their utility has always been limited by the side effect profile, which includes weight gain, short stature, and decreased bone density, among others,” Sharon Hesterlee, PhD, chief research officer for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, said in a statement.

The approval of vamorolone “provides people living with Duchenne, and their families, a powerful tool to treat the disease, while limiting some negative side effects associated with corticosteroids,” Dr. Hesterlee added.

The approval was based on data from the phase 2b VISION-DMD study, supplemented with safety information collected from three open-label studies.

Vamorolone was administered at doses ranging from 2-6 mg/kg/d for a period of up to 48 months.

Vamorolone demonstrated efficacy similar to that of traditional corticosteroids, with data suggesting a reduction in adverse events – notably related to bone health, growth trajectory, and behavior.

Vamorolone had received orphan drug status for DMD, as well as fast track and rare pediatric disease designations. It will be made available in the United States by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in patients as young as age 2 years, the company has announced Vamorolone is a structurally unique steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that potently inhibits proinflammatory NFkB pathways via high-affinity binding to the glucocorticoid receptor.

“Corticosteroids have been a first line treatment for DMD for many years, but their utility has always been limited by the side effect profile, which includes weight gain, short stature, and decreased bone density, among others,” Sharon Hesterlee, PhD, chief research officer for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, said in a statement.

The approval of vamorolone “provides people living with Duchenne, and their families, a powerful tool to treat the disease, while limiting some negative side effects associated with corticosteroids,” Dr. Hesterlee added.

The approval was based on data from the phase 2b VISION-DMD study, supplemented with safety information collected from three open-label studies.

Vamorolone was administered at doses ranging from 2-6 mg/kg/d for a period of up to 48 months.

Vamorolone demonstrated efficacy similar to that of traditional corticosteroids, with data suggesting a reduction in adverse events – notably related to bone health, growth trajectory, and behavior.

Vamorolone had received orphan drug status for DMD, as well as fast track and rare pediatric disease designations. It will be made available in the United States by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in patients as young as age 2 years, the company has announced Vamorolone is a structurally unique steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that potently inhibits proinflammatory NFkB pathways via high-affinity binding to the glucocorticoid receptor.

“Corticosteroids have been a first line treatment for DMD for many years, but their utility has always been limited by the side effect profile, which includes weight gain, short stature, and decreased bone density, among others,” Sharon Hesterlee, PhD, chief research officer for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, said in a statement.

The approval of vamorolone “provides people living with Duchenne, and their families, a powerful tool to treat the disease, while limiting some negative side effects associated with corticosteroids,” Dr. Hesterlee added.

The approval was based on data from the phase 2b VISION-DMD study, supplemented with safety information collected from three open-label studies.

Vamorolone was administered at doses ranging from 2-6 mg/kg/d for a period of up to 48 months.

Vamorolone demonstrated efficacy similar to that of traditional corticosteroids, with data suggesting a reduction in adverse events – notably related to bone health, growth trajectory, and behavior.

Vamorolone had received orphan drug status for DMD, as well as fast track and rare pediatric disease designations. It will be made available in the United States by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Online nicotine toothpick vendors ignore age restrictions

WASHINGTON – according to a study of 77 stores and 16 online sites.

Online nicotine toothpick sales are “the Wild West” in terms of regulation, said Abhijeet Grewal, a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Nicotine toothpicks have become popular among teenagers as a relatively inconspicuous way to access the drug, Mr. Grewal said. The nicotine content of the toothpicks varies, but many contain as much as 2-3 mg per pick compared with the 1.1-1.8–mg amount inhaled per the average cigarette, he said. The cheap price and teen-friendly flavors like cherry and mocha add to the appeal of the picks. However, data on the marketplace and accessibility of these products are lacking, Mr. Grewal said.

To find out how easily youth can buy nicotine toothpicks through in-person and online channels, Mr. Grewal and colleagues identified and called 404 brick-and-mortar retailers across the United States by phone and asked whether they required ID for purchase of nicotine toothpicks; of the 77 locations that responded, only 1 said that they would sell nicotine toothpicks without asking for proof of age.

The researchers also collected data on 16 vendor websites that sold nicotine toothpicks with shipment to the United States (identified from pixotine.com).

Overall, 11 sites (69%) prompted users to confirm that they were aged 21 years or older to either view the site or place orders, but 12 sites (75%) required no formal method of verification.

Warnings or disclaimers, such as “nicotine is an addictive chemical,” appeared on 69% of sites. Marketing statements including terms such as “discreet” and “cost-effective” to describe the toothpicks, Mr. Grewal said, and online reviews endorsed the products as “convenient” and “rich in flavor.”

The sites in the study offered a total of 32 different flavors, Mr. Grewal said, and 44% of the sites offered some type of discount on prices, which land in the range of approximately $5 for a tube of 20 toothpicks.

Nicotine toothpicks and flavored toothpicks without nicotine were originally marketed as smoking cessation aids, said Mr. Grewal, but their low price point and ability to be consumed discreetly makes them appealing to teens for nicotine use in many environments.

More research is needed to characterize youth use of nicotine toothpick products, as well as purchasing patterns, he said. However, the results highlight the need for regulation of nicotine toothpick vendors to protect youth from accessing nicotine in this form, he said.

Ask adolescents about toothpicks

“While nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] products may be an effective way for people to quit smoking, these products have the potential to introduce minors to nicotine in a seemingly innocent way resulting in dependence,” senior author Ruth Milanaik, DO, also of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, said in an interview. “Many children are intrigued by these fun flavored products, and our team was interested in examining the availability of these products to minors.”

Overall, “our team was quite pleased with brick-and-mortar stores’ spoken requirements of age verification for purchase, and quite worried about the availability of nic picks through online vendors,” she continued.

Clinicians, educators, and parents should be aware of the existence of nicotine toothpicks and the ease with which minors can attain them through online vendors, Dr. Milanaik said. “While NRT is a part of smoking cessation programs, nicotine toothpicks should not be used by minors without clinical reasons,” she said. “The innocuous and innocent nature of these toothpicks may entice minors to try and regularly use these without regard to future dependence.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON – according to a study of 77 stores and 16 online sites.

Online nicotine toothpick sales are “the Wild West” in terms of regulation, said Abhijeet Grewal, a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Nicotine toothpicks have become popular among teenagers as a relatively inconspicuous way to access the drug, Mr. Grewal said. The nicotine content of the toothpicks varies, but many contain as much as 2-3 mg per pick compared with the 1.1-1.8–mg amount inhaled per the average cigarette, he said. The cheap price and teen-friendly flavors like cherry and mocha add to the appeal of the picks. However, data on the marketplace and accessibility of these products are lacking, Mr. Grewal said.

To find out how easily youth can buy nicotine toothpicks through in-person and online channels, Mr. Grewal and colleagues identified and called 404 brick-and-mortar retailers across the United States by phone and asked whether they required ID for purchase of nicotine toothpicks; of the 77 locations that responded, only 1 said that they would sell nicotine toothpicks without asking for proof of age.

The researchers also collected data on 16 vendor websites that sold nicotine toothpicks with shipment to the United States (identified from pixotine.com).

Overall, 11 sites (69%) prompted users to confirm that they were aged 21 years or older to either view the site or place orders, but 12 sites (75%) required no formal method of verification.

Warnings or disclaimers, such as “nicotine is an addictive chemical,” appeared on 69% of sites. Marketing statements including terms such as “discreet” and “cost-effective” to describe the toothpicks, Mr. Grewal said, and online reviews endorsed the products as “convenient” and “rich in flavor.”

The sites in the study offered a total of 32 different flavors, Mr. Grewal said, and 44% of the sites offered some type of discount on prices, which land in the range of approximately $5 for a tube of 20 toothpicks.

Nicotine toothpicks and flavored toothpicks without nicotine were originally marketed as smoking cessation aids, said Mr. Grewal, but their low price point and ability to be consumed discreetly makes them appealing to teens for nicotine use in many environments.

More research is needed to characterize youth use of nicotine toothpick products, as well as purchasing patterns, he said. However, the results highlight the need for regulation of nicotine toothpick vendors to protect youth from accessing nicotine in this form, he said.

Ask adolescents about toothpicks

“While nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] products may be an effective way for people to quit smoking, these products have the potential to introduce minors to nicotine in a seemingly innocent way resulting in dependence,” senior author Ruth Milanaik, DO, also of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, said in an interview. “Many children are intrigued by these fun flavored products, and our team was interested in examining the availability of these products to minors.”

Overall, “our team was quite pleased with brick-and-mortar stores’ spoken requirements of age verification for purchase, and quite worried about the availability of nic picks through online vendors,” she continued.

Clinicians, educators, and parents should be aware of the existence of nicotine toothpicks and the ease with which minors can attain them through online vendors, Dr. Milanaik said. “While NRT is a part of smoking cessation programs, nicotine toothpicks should not be used by minors without clinical reasons,” she said. “The innocuous and innocent nature of these toothpicks may entice minors to try and regularly use these without regard to future dependence.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON – according to a study of 77 stores and 16 online sites.

Online nicotine toothpick sales are “the Wild West” in terms of regulation, said Abhijeet Grewal, a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Nicotine toothpicks have become popular among teenagers as a relatively inconspicuous way to access the drug, Mr. Grewal said. The nicotine content of the toothpicks varies, but many contain as much as 2-3 mg per pick compared with the 1.1-1.8–mg amount inhaled per the average cigarette, he said. The cheap price and teen-friendly flavors like cherry and mocha add to the appeal of the picks. However, data on the marketplace and accessibility of these products are lacking, Mr. Grewal said.

To find out how easily youth can buy nicotine toothpicks through in-person and online channels, Mr. Grewal and colleagues identified and called 404 brick-and-mortar retailers across the United States by phone and asked whether they required ID for purchase of nicotine toothpicks; of the 77 locations that responded, only 1 said that they would sell nicotine toothpicks without asking for proof of age.

The researchers also collected data on 16 vendor websites that sold nicotine toothpicks with shipment to the United States (identified from pixotine.com).

Overall, 11 sites (69%) prompted users to confirm that they were aged 21 years or older to either view the site or place orders, but 12 sites (75%) required no formal method of verification.

Warnings or disclaimers, such as “nicotine is an addictive chemical,” appeared on 69% of sites. Marketing statements including terms such as “discreet” and “cost-effective” to describe the toothpicks, Mr. Grewal said, and online reviews endorsed the products as “convenient” and “rich in flavor.”

The sites in the study offered a total of 32 different flavors, Mr. Grewal said, and 44% of the sites offered some type of discount on prices, which land in the range of approximately $5 for a tube of 20 toothpicks.

Nicotine toothpicks and flavored toothpicks without nicotine were originally marketed as smoking cessation aids, said Mr. Grewal, but their low price point and ability to be consumed discreetly makes them appealing to teens for nicotine use in many environments.

More research is needed to characterize youth use of nicotine toothpick products, as well as purchasing patterns, he said. However, the results highlight the need for regulation of nicotine toothpick vendors to protect youth from accessing nicotine in this form, he said.

Ask adolescents about toothpicks

“While nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] products may be an effective way for people to quit smoking, these products have the potential to introduce minors to nicotine in a seemingly innocent way resulting in dependence,” senior author Ruth Milanaik, DO, also of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, said in an interview. “Many children are intrigued by these fun flavored products, and our team was interested in examining the availability of these products to minors.”

Overall, “our team was quite pleased with brick-and-mortar stores’ spoken requirements of age verification for purchase, and quite worried about the availability of nic picks through online vendors,” she continued.

Clinicians, educators, and parents should be aware of the existence of nicotine toothpicks and the ease with which minors can attain them through online vendors, Dr. Milanaik said. “While NRT is a part of smoking cessation programs, nicotine toothpicks should not be used by minors without clinical reasons,” she said. “The innocuous and innocent nature of these toothpicks may entice minors to try and regularly use these without regard to future dependence.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAP 2023

Potential Uses of Nonthermal Atmospheric Pressure Technology for Dermatologic Conditions in Children

Nonthermal atmospheric plasma (NTAP)(or cold atmospheric plasma [CAP]) is a rapidly developing treatment modality for a wide range of dermatologic conditions. Plasma (or ionized gas) refers to a state of matter composed of electrons, protons, and neutral atoms that generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.1 Plasma previously was created using thermal energy, but recent advances have allowed the creation of plasma using atmospheric pressure and room temperature; thus, NTAP can be used without causing damage to living tissue through heat.1 Plasma technology varies greatly, but it generally can be classified as either direct or indirect therapy; direct therapy uses the human body as an electrode, whereas indirect therapy creates plasma through the interaction between 2 electrode devices.1,2 When used on the skin, important dose-dependent relationships have been observed, with CAP application longer than 2 minutes being associated with increased keratinocyte and fibroblast apoptosis.2 Thus, CAP can cause diverse changes to the skin depending on application time and methodology. At adequate yet low concentrations, plasma can promote fibroblast proliferation and upregulate genes involved in collagen and transforming growth factor synthesis.1 Additionally, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species created by NTAP have been shown to inactivate microorganisms through the destruction of biofilms, lead to diminished immune cell infiltration and cytokine release in autoimmune dermatologic conditions, and exert antitumor properties through cellular DNA damage.1-3 In dermatology, these properties can be harvested to promote wound healing at low doses and the treatment of proliferative skin conditions at high doses.1

Because of its novelty, the safety profile of NTAP is still under investigation, but preliminary studies are promising and show no damage to the skin barrier when excessive plasma exposure is avoided.4 However, dose- and time-dependent damage to cells has been shown. As a result, the exact dose of plasma considered safe is highly variable depending on the vessel, technique, and user, and future clinical research is needed to guide this methodology.4 Additionally, CAP has been shown to cause little pain at the skin surface and may lead to decreased levels of pain in healing wound sites.5 Given this promising safety profile and minimal discomfort to patients, NTAP technology remains promising for use in pediatric dermatology, but there are limited data to characterize its potential use in this population. In this systematic review, we aimed to elucidate reported applications of NTAP for skin conditions in children and discuss the trajectory of this technology in the future of pediatric dermatology.

Methodology

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify studies evaluating NTAP technology in pediatric populations using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. A search of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science articles was conducted in April 2023 using the terms nonthermal atmospheric plasma or cold atmospheric plasma. All English-language articles that described the use of NTAP as a treatment in pediatric populations or articles that described NTAP use in the treatment of common conditions in this patient group were included based on a review of the article titles and abstracts by 2 independent reviewers, followed by full-text review of relevant articles (M.G., C.L.). Any discrepancies in eligible articles were settled by a third independent researcher (M.V.). One hundred twenty studies were identified, and 95 were screened for inclusion; 9 studies met inclusion criteria and were summarized in this review.

Results

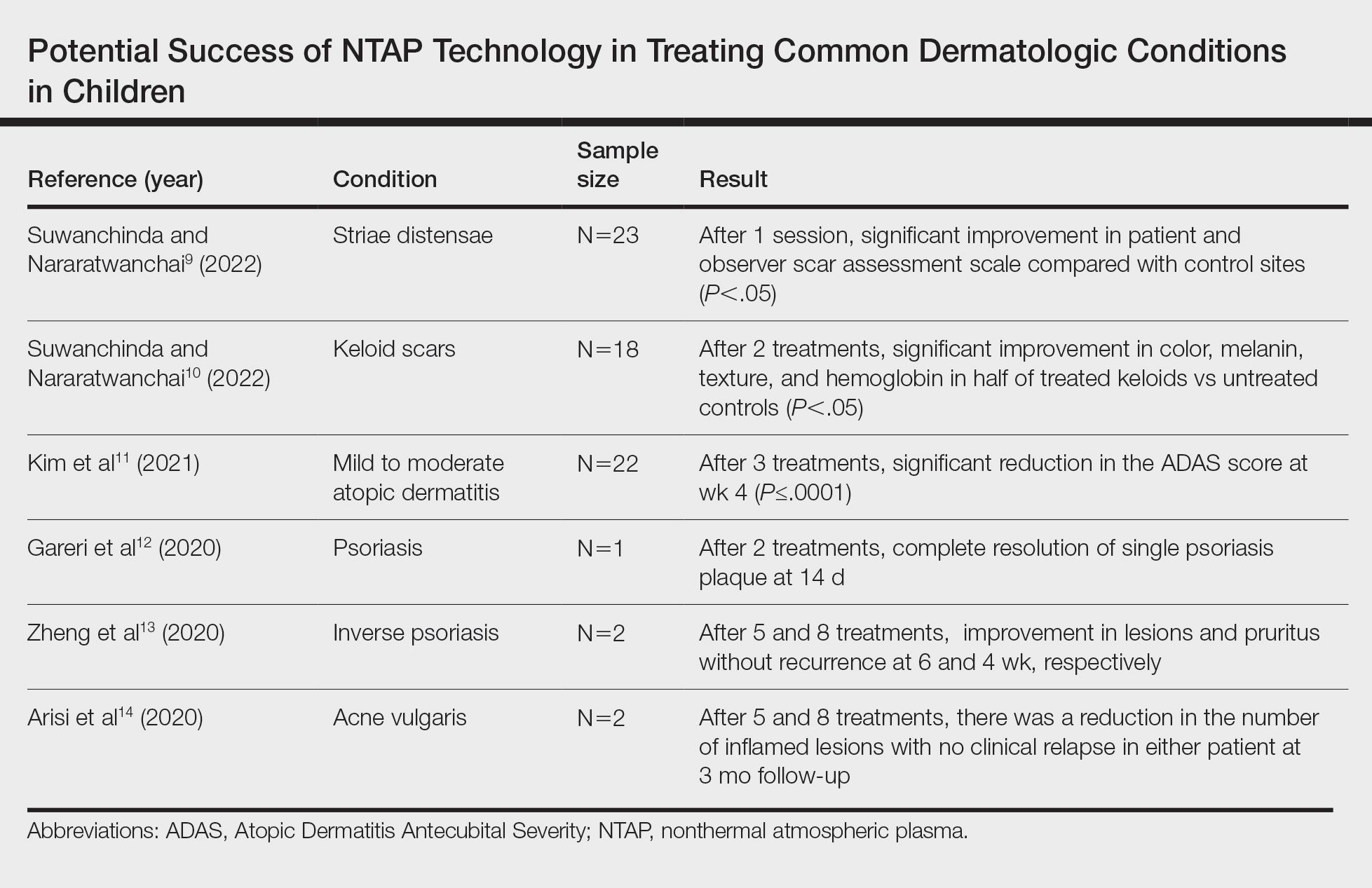

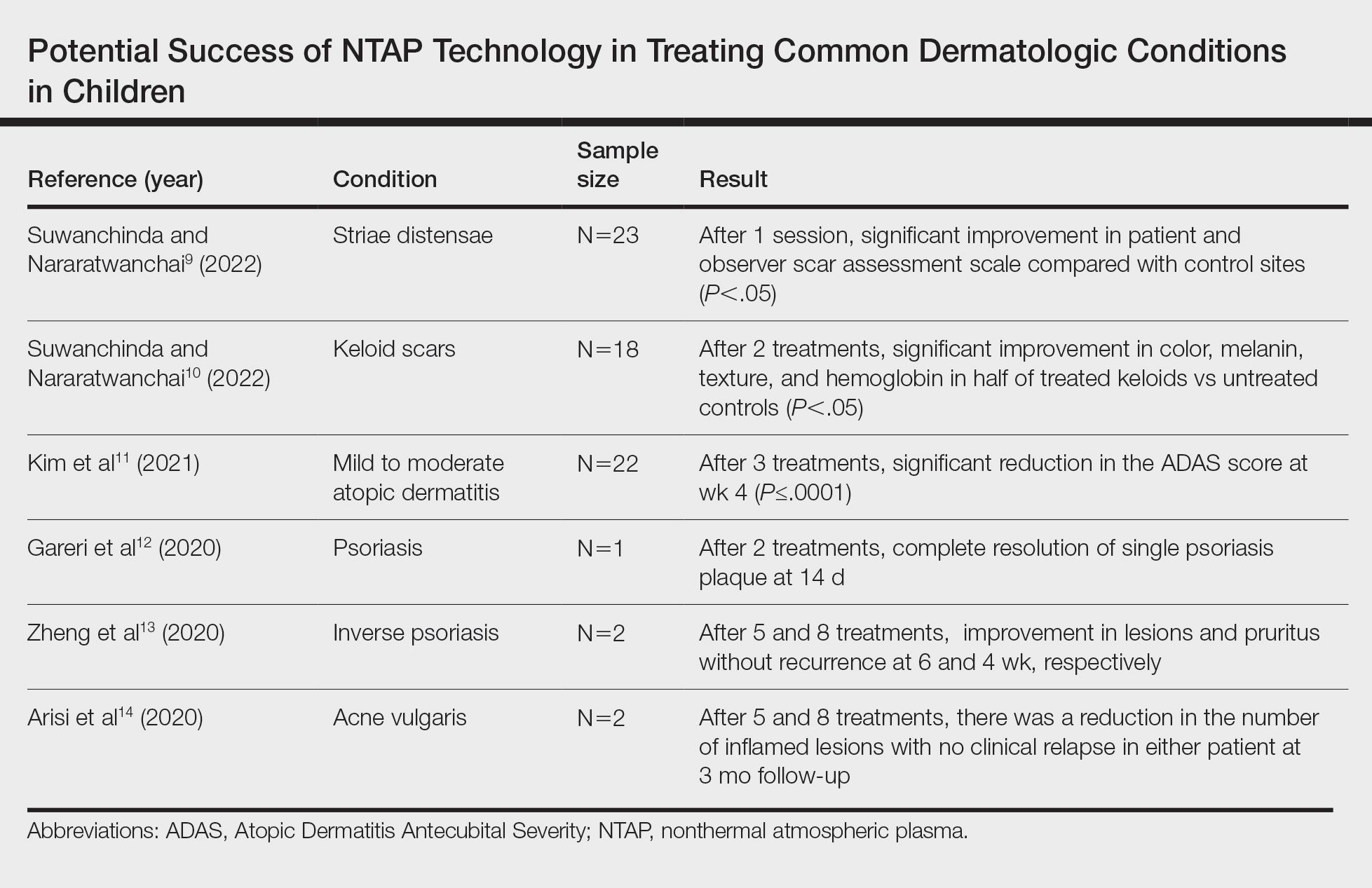

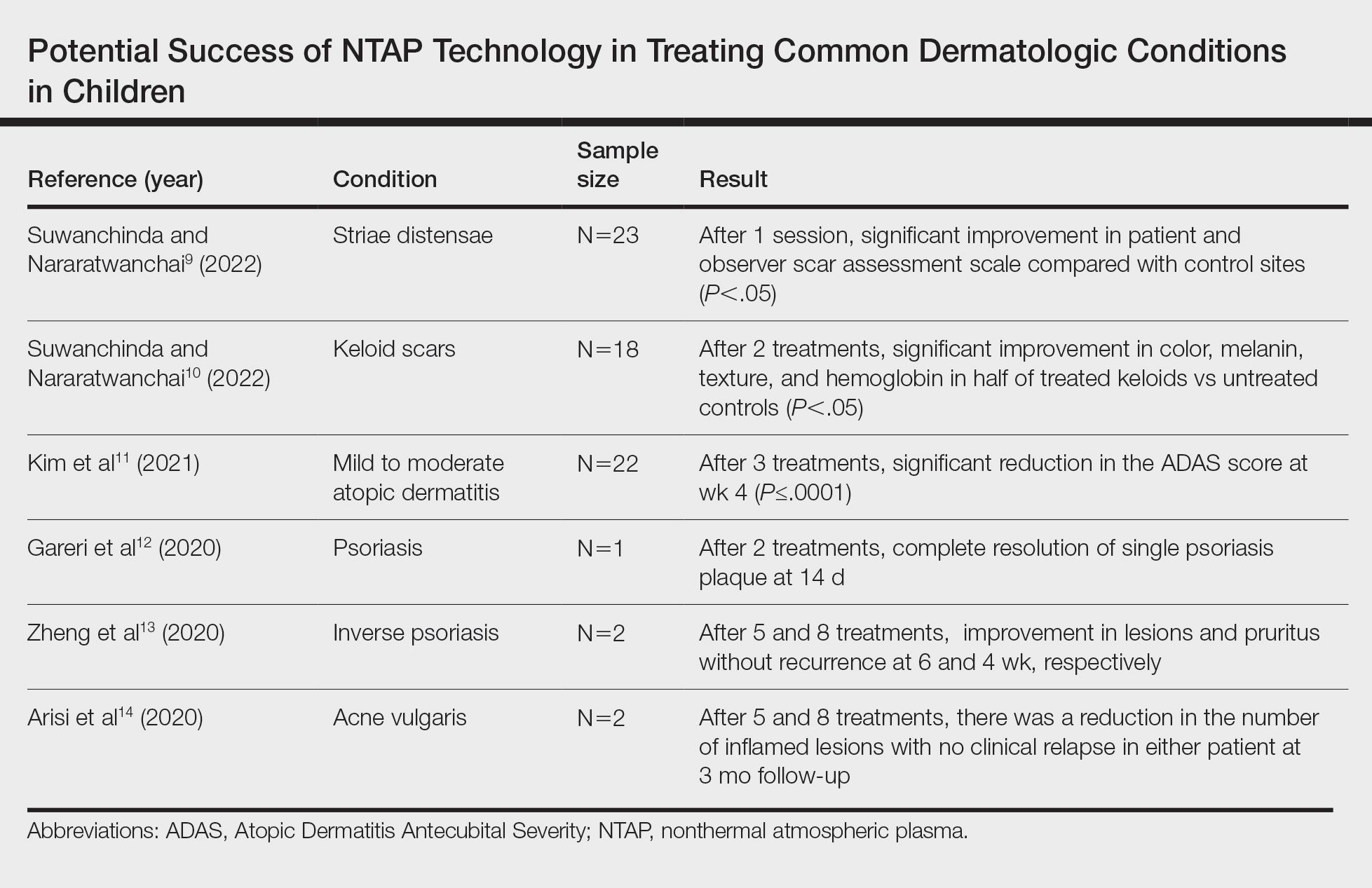

A total of 9 studies were included in this review: 3 describing the success of NTAP in pediatric populations6-8 and 6 describing the potential success of NTAP for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children (Table).9-14

Studies Describing Success of NTAP—Three clinical reports described the efficacy of NTAP in pediatric dermatology. A case series from 2020 showed full clearance of warts in 100% of patients (n=5) with a 0% recurrence rate when NTAP treatment was applied for 2 minutes to each lesion during each treatment session with the electrode held 1 mm from the lesional surface.6 Each patient was followed up at 3 to 4 weeks, and treatment was repeated if lesions persisted. Patients reported no pain during the procedure, and no adverse effects were noted over the course of treatment.6 Second, a case report described full clearance of diaper dermatitis with no recurrence after 6 months following 6 treatments with NTAP in a 14-month-old girl.7 After treatment with econazole nitrate cream, oral antibiotics, and prednisone failed, CAP treatment was initiated. Each treatment lasted 15 minutes with 3-day time intervals between each of the 6 treatments. There were no adverse events or recurrence of rash at 6-month follow-up.7 A final case report described full clearance of molluscum contagiosum (MC), with no recurrence after 2 months following 4 treatments with NTAP in a 12-year-old boy.8 The patient had untreated MC on the face, neck, shoulder, and thighs. Lesions of the face were treated with CAP, while the other sites were treated with cantharidin using a 0.7% collodion-based solution. Four CAP treatments were performed at 1-month intervals, with CAP applied 1 mm from the lesional surfaces in a circular pattern for 2 minutes. At follow-up 2 months after the final treatment, the patient had no adverse effects and showed no pigmentary changes or scarring.8

Studies Describing the Potential Success of NTAP—Beyond these studies, limited research has been done on NTAP in pediatric populations. The Table summarizes 6 additional studies completed with promising treatment results for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children: striae distensae, keloids, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, and acne vulgaris. Across all reports and studies, patients showed significant improvement in their dermatologic conditions following the use of NTAP technology with limited adverse effects reported (P<.05). Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai9 studied the use of CAP for the treatment of striae distensae. They recruited 23 patients and treated half the body with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions; the other half was left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, striae distensae had improved for both patient and observer assessment scores.9 Another study performed by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 looked at the efficacy of CAP in treating keloids. They recruited 18 patients, and keloid scars were treated in halves—one half treated with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions and the other left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, keloids significantly improved in color, melanin, texture, and hemoglobin based on assessment by the Antera 3D imaging system (Miravex Limited)(P<.05).10

Kim et al11 studied the efficacy of CAP for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in 22 patients. Each patient had mild to moderate atopic dermatitis that had not been treated with topical agents or antibiotics for at least 2 weeks prior to beginning the study. Additionally, only patients with symmetric lesions—meaning only patients with lesions on both sides of the anatomical extremities—were included. Each patient then received CAP on 1 symmetric lesion and placebo on the other. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment was done 5 mm away from the lesion, and each treatment lasted for 5 minutes. Treatments were done at weeks 0, 1, and 2, with follow-up 4 weeks after the final treatment. The clinical severity of disease was assessed at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 4. Results showed that at week 4, the mean (SD) modified Atopic Dermatitis Antecubital Severity score decreased from 33.73 (21.21) at week 0 to 13.12 (15.92). Additionally, the pruritic visual analog scale showed significant improvement with treatment vs baseline (P≤.0001).11

Two studies examined how NTAP can be used in the treatment of psoriasis. First, Gareri et al12 used CAP to treat a psoriatic plaque in a 20-year-old woman. These plaques on the left hand previously had been unresponsive to topical psoriasis treatments. The patient received 2 treatments with CAP on days 0 and 3; at 14 days, the plaque completely resolved with an itch score of 0.12 Next, Zheng et al13 treated 2 patients with NTAP for inverse psoriasis. The first patient was a 26-year-old woman with plaques in the axilla and buttocks as well as inframammary lesions that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and vitamin D analogues. She received CAP treatments 2 to 3 times weekly for 5 total treatments with application to each region occurring 1 mm from the skin surface. The lesions completely resolved with no recurrence at 6 weeks. The second patient was a 38-year-old woman with inverse psoriasis in the axilla and groin; she received treatment every 3 days for 8 total treatments, which led to complete remission, with no recurrence noted at 1 month.13

Arisi et al14 used NTAP to treat acne vulgaris in 2 patients. The first patient was a 24-year-old man with moderate acne on the face that did not improve with topicals or oral antibiotics. The patient received 5 CAP treatments with no adverse events noted. The patient discontinued treatment on his own, but the number of lesions decreased after the fifth treatment. The second patient was a 21-year-old woman with moderate facial acne that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and oral tetracycline. The patient received 8 CAP treatments and experienced a reduction in the number of lesions during treatment. There were no adverse events, and improvement was maintained at 3-month follow-up.14

Comment

Although the use of NTAP in pediatric dermatology is scarcely described in the literature, the technology will certainly have applications in the future treatment of a wide variety of pediatric disorders. In addition to the clinical success shown in several studies,6-14 this technology has been shown to cause minimal damage to skin when application time is minimized. One study conducted on ex vivo skin showed that NTAP technology can safely be used for up to 2 minutes without major DNA damage.15 Through its diverse mechanisms of action, NTAP can induce modification of proteins and cell membranes in a noninvasive manner.2 In conditions with impaired barrier function, such as atopic and diaper dermatitis, studies in mouse models have shown improvement in lesions via upregulation of mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor that contributes to decreased inflammation and cell apoptosis.16 Additionally, the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species has been shown to decrease Staphylococcus aureus colonization to improve atopic dermatitis lesions in patients.11

Many other proposed benefits of NTAP in dermatologic disease also have been proposed. Nonthermal atmospheric plasma has been shown to increase messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6) and upregulate type III collagen production in early stages of wound healing.17 Furthermore, NTAP has been shown to stimulate nuclear factor erythroid 2–related pathways involved in antioxidant production in keratinocytes, further promoting wound healing.18 Additionally, CAP has been shown to increase expression of caspases and induce mitochondrial dysfunction that promotes cell death in different cancer cell lines.19 It is clear that the exact breadth of NTAP’s biochemical effects are unknown, but the current literature shows promise for its use in cutaneous healing and cancer treatment.

Beyond its diverse applications, treatment with NTAP yields a unique advantage to pharmacologic therapies in that there is no risk for medication interactions or risk for pharmacologic adverse effects. Cantharidin is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but commonly is used to treat MC. It is a blister beetle extract that causes a blister to form when applied to the skin. When orally ingested, the drug is toxic to the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys because of its phosphodiesterase inhibition, a feared complication in pediatric patients who may inadvertently ingest it during treatment.20 This utility extends beyond MC, such as the beneficial outcomes described by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 in using NTAP for keloid scars. Treatment with NTAP may replace triamcinolone injections, which are commonly associated with skin atrophy and ulceration. In addition, NTAP application to the skin has been reported to be relatively painless.5 Thus, NTAP maintains a distinct advantage over other commonly used nonpharmacologic treatment options, including curettage and cryosurgery. Curettage has widely been noted to be traumatic for the patient, may be more likely to leave a mark, and is prone to user error.20 Cryosurgery is a common form of treatment for MC because it is cost-effective and has good cosmetic results; however, it is more painful than cantharidin or anesthetized curettage.21 Treatment with NTAP is an emerging therapeutic tool with an expanding role in the treatment of dermatologic patients because it provides advantages over many standard therapies due to its minimal side-effect profile involving pain and nonpharmacologic nature.

Limitations of this report include exclusion of non–English-language articles and lack of control or comparison groups to standard therapies across studies. Additionally, reports of NTAP success occurred in many conditions that are self-limited and may have resolved on their own. Regardless, we aimed to summarize how NTAP currently is being used in pediatric populations and highlight its potential uses moving forward. Given its promising safety profile and painless nature, future clinical trials should prioritize the investigation of NTAP use in common pediatric dermatologic conditions to determine if they are equal or superior to current standards of care.

- Gan L, Zhang S, Poorun D, et al. Medical applications of nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:7-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13373

- Gay-Mimbrera J, García MC, Isla-Tejera B, et al. Clinical and biological principles of cold atmospheric plasma application in skin cancer. Adv Ther. 2016;33:894-909. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0338-1. Published correction appears in Adv Ther. 2017;34:280. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0437-z

- Zhai SY, Kong MG, Xia YM. Cold atmospheric plasma ameliorates skin diseases involving reactive oxygen/nitrogen species-mediated functions. Front Immunol. 2022;13:868386. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.868386

- Tan F, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. Plasma dermatology: skin therapy using cold atmospheric plasma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:918484. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.918484

- van Welzen A, Hoch M, Wahl P, et al. The response and tolerability of a novel cold atmospheric plasma wound dressing for the healing of split skin graft donor sites: a controlled pilot study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;34:328-336. doi:10.1159/000517524

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Using cold plasma to treat warts in children: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:706-709. doi:10.1111/pde.14180

- Zhang C, Zhao J, Gao Y, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment for diaper dermatitis: a case report [published online January 27, 2021]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14739. doi:10.1111/dth.14739

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma clears molluscum contagiosum. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:562-563. doi:10.1111/exd.14695

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. The efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of striae distensae: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6805-6814. doi:10.1111/jocd.15458

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. Efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of keloid: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6788-6797. doi:10.1111/jocd.15397

- Kim YJ, Lim DJ, Lee MY, et al. Prospective, comparative clinical pilot study of cold atmospheric plasma device in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14461. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93941-y

- Gareri C, Bennardo L, De Masi G. Use of a new cold plasma tool for psoriasis treatment: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20922709. doi:10.1177/2050313X20922709

- Zheng L, Gao J, Cao Y, et al. Two case reports of inverse psoriasis treated with cold atmospheric plasma. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14257. doi:10.1111/dth.14257

- Arisi M, Venturuzzo A, Gelmetti A, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) as a promising therapeutic option for mild to moderate acne vulgaris: clinical and non-invasive evaluation of two cases. Clin Plasma Med. 2020;19-20:100110.

- Isbary G, Köritzer J, Mitra A, et al. Ex vivo human skin experiments for the evaluation of safety of new cold atmospheric plasma devices. Clin Plasma Med. 2013;1:36-44.

- Sun T, Zhang X, Hou C, et al. Cold plasma irradiation attenuates atopic dermatitis via enhancing HIF-1α-induced MANF transcription expression. Front Immunol. 2022;13:941219. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.941219

- Eggers B, Marciniak J, Memmert S, et al. The beneficial effect of cold atmospheric plasma on parameters of molecules and cell function involved in wound healing in human osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Odontology. 2020;108:607-616. doi:10.1007/s10266-020-00487-y

- Conway GE, He Z, Hutanu AL, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma induces accumulation of lysosomes and caspase-independent cell death in U373MG glioblastoma multiforme cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12891. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49013-3

- Schmidt A, Dietrich S, Steuer A, et al. Non-thermal plasma activates human keratinocytes by stimulation of antioxidant and phase II pathways. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:6731-6750. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.603555

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:505-511. doi:10.2165/00148581-200305080-00001

- Cotton DW, Cooper C, Barrett DF, et al. Severe atypical molluscum contagiosum infection in an immunocompromised host. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:871-876. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04908.x

Nonthermal atmospheric plasma (NTAP)(or cold atmospheric plasma [CAP]) is a rapidly developing treatment modality for a wide range of dermatologic conditions. Plasma (or ionized gas) refers to a state of matter composed of electrons, protons, and neutral atoms that generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.1 Plasma previously was created using thermal energy, but recent advances have allowed the creation of plasma using atmospheric pressure and room temperature; thus, NTAP can be used without causing damage to living tissue through heat.1 Plasma technology varies greatly, but it generally can be classified as either direct or indirect therapy; direct therapy uses the human body as an electrode, whereas indirect therapy creates plasma through the interaction between 2 electrode devices.1,2 When used on the skin, important dose-dependent relationships have been observed, with CAP application longer than 2 minutes being associated with increased keratinocyte and fibroblast apoptosis.2 Thus, CAP can cause diverse changes to the skin depending on application time and methodology. At adequate yet low concentrations, plasma can promote fibroblast proliferation and upregulate genes involved in collagen and transforming growth factor synthesis.1 Additionally, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species created by NTAP have been shown to inactivate microorganisms through the destruction of biofilms, lead to diminished immune cell infiltration and cytokine release in autoimmune dermatologic conditions, and exert antitumor properties through cellular DNA damage.1-3 In dermatology, these properties can be harvested to promote wound healing at low doses and the treatment of proliferative skin conditions at high doses.1

Because of its novelty, the safety profile of NTAP is still under investigation, but preliminary studies are promising and show no damage to the skin barrier when excessive plasma exposure is avoided.4 However, dose- and time-dependent damage to cells has been shown. As a result, the exact dose of plasma considered safe is highly variable depending on the vessel, technique, and user, and future clinical research is needed to guide this methodology.4 Additionally, CAP has been shown to cause little pain at the skin surface and may lead to decreased levels of pain in healing wound sites.5 Given this promising safety profile and minimal discomfort to patients, NTAP technology remains promising for use in pediatric dermatology, but there are limited data to characterize its potential use in this population. In this systematic review, we aimed to elucidate reported applications of NTAP for skin conditions in children and discuss the trajectory of this technology in the future of pediatric dermatology.

Methodology

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify studies evaluating NTAP technology in pediatric populations using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. A search of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science articles was conducted in April 2023 using the terms nonthermal atmospheric plasma or cold atmospheric plasma. All English-language articles that described the use of NTAP as a treatment in pediatric populations or articles that described NTAP use in the treatment of common conditions in this patient group were included based on a review of the article titles and abstracts by 2 independent reviewers, followed by full-text review of relevant articles (M.G., C.L.). Any discrepancies in eligible articles were settled by a third independent researcher (M.V.). One hundred twenty studies were identified, and 95 were screened for inclusion; 9 studies met inclusion criteria and were summarized in this review.

Results

A total of 9 studies were included in this review: 3 describing the success of NTAP in pediatric populations6-8 and 6 describing the potential success of NTAP for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children (Table).9-14

Studies Describing Success of NTAP—Three clinical reports described the efficacy of NTAP in pediatric dermatology. A case series from 2020 showed full clearance of warts in 100% of patients (n=5) with a 0% recurrence rate when NTAP treatment was applied for 2 minutes to each lesion during each treatment session with the electrode held 1 mm from the lesional surface.6 Each patient was followed up at 3 to 4 weeks, and treatment was repeated if lesions persisted. Patients reported no pain during the procedure, and no adverse effects were noted over the course of treatment.6 Second, a case report described full clearance of diaper dermatitis with no recurrence after 6 months following 6 treatments with NTAP in a 14-month-old girl.7 After treatment with econazole nitrate cream, oral antibiotics, and prednisone failed, CAP treatment was initiated. Each treatment lasted 15 minutes with 3-day time intervals between each of the 6 treatments. There were no adverse events or recurrence of rash at 6-month follow-up.7 A final case report described full clearance of molluscum contagiosum (MC), with no recurrence after 2 months following 4 treatments with NTAP in a 12-year-old boy.8 The patient had untreated MC on the face, neck, shoulder, and thighs. Lesions of the face were treated with CAP, while the other sites were treated with cantharidin using a 0.7% collodion-based solution. Four CAP treatments were performed at 1-month intervals, with CAP applied 1 mm from the lesional surfaces in a circular pattern for 2 minutes. At follow-up 2 months after the final treatment, the patient had no adverse effects and showed no pigmentary changes or scarring.8

Studies Describing the Potential Success of NTAP—Beyond these studies, limited research has been done on NTAP in pediatric populations. The Table summarizes 6 additional studies completed with promising treatment results for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children: striae distensae, keloids, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, and acne vulgaris. Across all reports and studies, patients showed significant improvement in their dermatologic conditions following the use of NTAP technology with limited adverse effects reported (P<.05). Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai9 studied the use of CAP for the treatment of striae distensae. They recruited 23 patients and treated half the body with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions; the other half was left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, striae distensae had improved for both patient and observer assessment scores.9 Another study performed by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 looked at the efficacy of CAP in treating keloids. They recruited 18 patients, and keloid scars were treated in halves—one half treated with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions and the other left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, keloids significantly improved in color, melanin, texture, and hemoglobin based on assessment by the Antera 3D imaging system (Miravex Limited)(P<.05).10

Kim et al11 studied the efficacy of CAP for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in 22 patients. Each patient had mild to moderate atopic dermatitis that had not been treated with topical agents or antibiotics for at least 2 weeks prior to beginning the study. Additionally, only patients with symmetric lesions—meaning only patients with lesions on both sides of the anatomical extremities—were included. Each patient then received CAP on 1 symmetric lesion and placebo on the other. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment was done 5 mm away from the lesion, and each treatment lasted for 5 minutes. Treatments were done at weeks 0, 1, and 2, with follow-up 4 weeks after the final treatment. The clinical severity of disease was assessed at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 4. Results showed that at week 4, the mean (SD) modified Atopic Dermatitis Antecubital Severity score decreased from 33.73 (21.21) at week 0 to 13.12 (15.92). Additionally, the pruritic visual analog scale showed significant improvement with treatment vs baseline (P≤.0001).11

Two studies examined how NTAP can be used in the treatment of psoriasis. First, Gareri et al12 used CAP to treat a psoriatic plaque in a 20-year-old woman. These plaques on the left hand previously had been unresponsive to topical psoriasis treatments. The patient received 2 treatments with CAP on days 0 and 3; at 14 days, the plaque completely resolved with an itch score of 0.12 Next, Zheng et al13 treated 2 patients with NTAP for inverse psoriasis. The first patient was a 26-year-old woman with plaques in the axilla and buttocks as well as inframammary lesions that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and vitamin D analogues. She received CAP treatments 2 to 3 times weekly for 5 total treatments with application to each region occurring 1 mm from the skin surface. The lesions completely resolved with no recurrence at 6 weeks. The second patient was a 38-year-old woman with inverse psoriasis in the axilla and groin; she received treatment every 3 days for 8 total treatments, which led to complete remission, with no recurrence noted at 1 month.13

Arisi et al14 used NTAP to treat acne vulgaris in 2 patients. The first patient was a 24-year-old man with moderate acne on the face that did not improve with topicals or oral antibiotics. The patient received 5 CAP treatments with no adverse events noted. The patient discontinued treatment on his own, but the number of lesions decreased after the fifth treatment. The second patient was a 21-year-old woman with moderate facial acne that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and oral tetracycline. The patient received 8 CAP treatments and experienced a reduction in the number of lesions during treatment. There were no adverse events, and improvement was maintained at 3-month follow-up.14

Comment

Although the use of NTAP in pediatric dermatology is scarcely described in the literature, the technology will certainly have applications in the future treatment of a wide variety of pediatric disorders. In addition to the clinical success shown in several studies,6-14 this technology has been shown to cause minimal damage to skin when application time is minimized. One study conducted on ex vivo skin showed that NTAP technology can safely be used for up to 2 minutes without major DNA damage.15 Through its diverse mechanisms of action, NTAP can induce modification of proteins and cell membranes in a noninvasive manner.2 In conditions with impaired barrier function, such as atopic and diaper dermatitis, studies in mouse models have shown improvement in lesions via upregulation of mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor that contributes to decreased inflammation and cell apoptosis.16 Additionally, the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species has been shown to decrease Staphylococcus aureus colonization to improve atopic dermatitis lesions in patients.11

Many other proposed benefits of NTAP in dermatologic disease also have been proposed. Nonthermal atmospheric plasma has been shown to increase messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6) and upregulate type III collagen production in early stages of wound healing.17 Furthermore, NTAP has been shown to stimulate nuclear factor erythroid 2–related pathways involved in antioxidant production in keratinocytes, further promoting wound healing.18 Additionally, CAP has been shown to increase expression of caspases and induce mitochondrial dysfunction that promotes cell death in different cancer cell lines.19 It is clear that the exact breadth of NTAP’s biochemical effects are unknown, but the current literature shows promise for its use in cutaneous healing and cancer treatment.

Beyond its diverse applications, treatment with NTAP yields a unique advantage to pharmacologic therapies in that there is no risk for medication interactions or risk for pharmacologic adverse effects. Cantharidin is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but commonly is used to treat MC. It is a blister beetle extract that causes a blister to form when applied to the skin. When orally ingested, the drug is toxic to the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys because of its phosphodiesterase inhibition, a feared complication in pediatric patients who may inadvertently ingest it during treatment.20 This utility extends beyond MC, such as the beneficial outcomes described by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 in using NTAP for keloid scars. Treatment with NTAP may replace triamcinolone injections, which are commonly associated with skin atrophy and ulceration. In addition, NTAP application to the skin has been reported to be relatively painless.5 Thus, NTAP maintains a distinct advantage over other commonly used nonpharmacologic treatment options, including curettage and cryosurgery. Curettage has widely been noted to be traumatic for the patient, may be more likely to leave a mark, and is prone to user error.20 Cryosurgery is a common form of treatment for MC because it is cost-effective and has good cosmetic results; however, it is more painful than cantharidin or anesthetized curettage.21 Treatment with NTAP is an emerging therapeutic tool with an expanding role in the treatment of dermatologic patients because it provides advantages over many standard therapies due to its minimal side-effect profile involving pain and nonpharmacologic nature.

Limitations of this report include exclusion of non–English-language articles and lack of control or comparison groups to standard therapies across studies. Additionally, reports of NTAP success occurred in many conditions that are self-limited and may have resolved on their own. Regardless, we aimed to summarize how NTAP currently is being used in pediatric populations and highlight its potential uses moving forward. Given its promising safety profile and painless nature, future clinical trials should prioritize the investigation of NTAP use in common pediatric dermatologic conditions to determine if they are equal or superior to current standards of care.

Nonthermal atmospheric plasma (NTAP)(or cold atmospheric plasma [CAP]) is a rapidly developing treatment modality for a wide range of dermatologic conditions. Plasma (or ionized gas) refers to a state of matter composed of electrons, protons, and neutral atoms that generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.1 Plasma previously was created using thermal energy, but recent advances have allowed the creation of plasma using atmospheric pressure and room temperature; thus, NTAP can be used without causing damage to living tissue through heat.1 Plasma technology varies greatly, but it generally can be classified as either direct or indirect therapy; direct therapy uses the human body as an electrode, whereas indirect therapy creates plasma through the interaction between 2 electrode devices.1,2 When used on the skin, important dose-dependent relationships have been observed, with CAP application longer than 2 minutes being associated with increased keratinocyte and fibroblast apoptosis.2 Thus, CAP can cause diverse changes to the skin depending on application time and methodology. At adequate yet low concentrations, plasma can promote fibroblast proliferation and upregulate genes involved in collagen and transforming growth factor synthesis.1 Additionally, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species created by NTAP have been shown to inactivate microorganisms through the destruction of biofilms, lead to diminished immune cell infiltration and cytokine release in autoimmune dermatologic conditions, and exert antitumor properties through cellular DNA damage.1-3 In dermatology, these properties can be harvested to promote wound healing at low doses and the treatment of proliferative skin conditions at high doses.1

Because of its novelty, the safety profile of NTAP is still under investigation, but preliminary studies are promising and show no damage to the skin barrier when excessive plasma exposure is avoided.4 However, dose- and time-dependent damage to cells has been shown. As a result, the exact dose of plasma considered safe is highly variable depending on the vessel, technique, and user, and future clinical research is needed to guide this methodology.4 Additionally, CAP has been shown to cause little pain at the skin surface and may lead to decreased levels of pain in healing wound sites.5 Given this promising safety profile and minimal discomfort to patients, NTAP technology remains promising for use in pediatric dermatology, but there are limited data to characterize its potential use in this population. In this systematic review, we aimed to elucidate reported applications of NTAP for skin conditions in children and discuss the trajectory of this technology in the future of pediatric dermatology.

Methodology

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify studies evaluating NTAP technology in pediatric populations using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. A search of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science articles was conducted in April 2023 using the terms nonthermal atmospheric plasma or cold atmospheric plasma. All English-language articles that described the use of NTAP as a treatment in pediatric populations or articles that described NTAP use in the treatment of common conditions in this patient group were included based on a review of the article titles and abstracts by 2 independent reviewers, followed by full-text review of relevant articles (M.G., C.L.). Any discrepancies in eligible articles were settled by a third independent researcher (M.V.). One hundred twenty studies were identified, and 95 were screened for inclusion; 9 studies met inclusion criteria and were summarized in this review.

Results

A total of 9 studies were included in this review: 3 describing the success of NTAP in pediatric populations6-8 and 6 describing the potential success of NTAP for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children (Table).9-14

Studies Describing Success of NTAP—Three clinical reports described the efficacy of NTAP in pediatric dermatology. A case series from 2020 showed full clearance of warts in 100% of patients (n=5) with a 0% recurrence rate when NTAP treatment was applied for 2 minutes to each lesion during each treatment session with the electrode held 1 mm from the lesional surface.6 Each patient was followed up at 3 to 4 weeks, and treatment was repeated if lesions persisted. Patients reported no pain during the procedure, and no adverse effects were noted over the course of treatment.6 Second, a case report described full clearance of diaper dermatitis with no recurrence after 6 months following 6 treatments with NTAP in a 14-month-old girl.7 After treatment with econazole nitrate cream, oral antibiotics, and prednisone failed, CAP treatment was initiated. Each treatment lasted 15 minutes with 3-day time intervals between each of the 6 treatments. There were no adverse events or recurrence of rash at 6-month follow-up.7 A final case report described full clearance of molluscum contagiosum (MC), with no recurrence after 2 months following 4 treatments with NTAP in a 12-year-old boy.8 The patient had untreated MC on the face, neck, shoulder, and thighs. Lesions of the face were treated with CAP, while the other sites were treated with cantharidin using a 0.7% collodion-based solution. Four CAP treatments were performed at 1-month intervals, with CAP applied 1 mm from the lesional surfaces in a circular pattern for 2 minutes. At follow-up 2 months after the final treatment, the patient had no adverse effects and showed no pigmentary changes or scarring.8

Studies Describing the Potential Success of NTAP—Beyond these studies, limited research has been done on NTAP in pediatric populations. The Table summarizes 6 additional studies completed with promising treatment results for dermatologic conditions commonly seen in children: striae distensae, keloids, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, and acne vulgaris. Across all reports and studies, patients showed significant improvement in their dermatologic conditions following the use of NTAP technology with limited adverse effects reported (P<.05). Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai9 studied the use of CAP for the treatment of striae distensae. They recruited 23 patients and treated half the body with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions; the other half was left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, striae distensae had improved for both patient and observer assessment scores.9 Another study performed by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 looked at the efficacy of CAP in treating keloids. They recruited 18 patients, and keloid scars were treated in halves—one half treated with CAP biweekly for 5 sessions and the other left untreated. At follow-up 30 days after the final treatment, keloids significantly improved in color, melanin, texture, and hemoglobin based on assessment by the Antera 3D imaging system (Miravex Limited)(P<.05).10

Kim et al11 studied the efficacy of CAP for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in 22 patients. Each patient had mild to moderate atopic dermatitis that had not been treated with topical agents or antibiotics for at least 2 weeks prior to beginning the study. Additionally, only patients with symmetric lesions—meaning only patients with lesions on both sides of the anatomical extremities—were included. Each patient then received CAP on 1 symmetric lesion and placebo on the other. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment was done 5 mm away from the lesion, and each treatment lasted for 5 minutes. Treatments were done at weeks 0, 1, and 2, with follow-up 4 weeks after the final treatment. The clinical severity of disease was assessed at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 4. Results showed that at week 4, the mean (SD) modified Atopic Dermatitis Antecubital Severity score decreased from 33.73 (21.21) at week 0 to 13.12 (15.92). Additionally, the pruritic visual analog scale showed significant improvement with treatment vs baseline (P≤.0001).11

Two studies examined how NTAP can be used in the treatment of psoriasis. First, Gareri et al12 used CAP to treat a psoriatic plaque in a 20-year-old woman. These plaques on the left hand previously had been unresponsive to topical psoriasis treatments. The patient received 2 treatments with CAP on days 0 and 3; at 14 days, the plaque completely resolved with an itch score of 0.12 Next, Zheng et al13 treated 2 patients with NTAP for inverse psoriasis. The first patient was a 26-year-old woman with plaques in the axilla and buttocks as well as inframammary lesions that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and vitamin D analogues. She received CAP treatments 2 to 3 times weekly for 5 total treatments with application to each region occurring 1 mm from the skin surface. The lesions completely resolved with no recurrence at 6 weeks. The second patient was a 38-year-old woman with inverse psoriasis in the axilla and groin; she received treatment every 3 days for 8 total treatments, which led to complete remission, with no recurrence noted at 1 month.13

Arisi et al14 used NTAP to treat acne vulgaris in 2 patients. The first patient was a 24-year-old man with moderate acne on the face that did not improve with topicals or oral antibiotics. The patient received 5 CAP treatments with no adverse events noted. The patient discontinued treatment on his own, but the number of lesions decreased after the fifth treatment. The second patient was a 21-year-old woman with moderate facial acne that failed to respond to treatment with topicals and oral tetracycline. The patient received 8 CAP treatments and experienced a reduction in the number of lesions during treatment. There were no adverse events, and improvement was maintained at 3-month follow-up.14

Comment

Although the use of NTAP in pediatric dermatology is scarcely described in the literature, the technology will certainly have applications in the future treatment of a wide variety of pediatric disorders. In addition to the clinical success shown in several studies,6-14 this technology has been shown to cause minimal damage to skin when application time is minimized. One study conducted on ex vivo skin showed that NTAP technology can safely be used for up to 2 minutes without major DNA damage.15 Through its diverse mechanisms of action, NTAP can induce modification of proteins and cell membranes in a noninvasive manner.2 In conditions with impaired barrier function, such as atopic and diaper dermatitis, studies in mouse models have shown improvement in lesions via upregulation of mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor that contributes to decreased inflammation and cell apoptosis.16 Additionally, the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species has been shown to decrease Staphylococcus aureus colonization to improve atopic dermatitis lesions in patients.11

Many other proposed benefits of NTAP in dermatologic disease also have been proposed. Nonthermal atmospheric plasma has been shown to increase messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6) and upregulate type III collagen production in early stages of wound healing.17 Furthermore, NTAP has been shown to stimulate nuclear factor erythroid 2–related pathways involved in antioxidant production in keratinocytes, further promoting wound healing.18 Additionally, CAP has been shown to increase expression of caspases and induce mitochondrial dysfunction that promotes cell death in different cancer cell lines.19 It is clear that the exact breadth of NTAP’s biochemical effects are unknown, but the current literature shows promise for its use in cutaneous healing and cancer treatment.

Beyond its diverse applications, treatment with NTAP yields a unique advantage to pharmacologic therapies in that there is no risk for medication interactions or risk for pharmacologic adverse effects. Cantharidin is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but commonly is used to treat MC. It is a blister beetle extract that causes a blister to form when applied to the skin. When orally ingested, the drug is toxic to the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys because of its phosphodiesterase inhibition, a feared complication in pediatric patients who may inadvertently ingest it during treatment.20 This utility extends beyond MC, such as the beneficial outcomes described by Suwanchinda and Nararatwanchai10 in using NTAP for keloid scars. Treatment with NTAP may replace triamcinolone injections, which are commonly associated with skin atrophy and ulceration. In addition, NTAP application to the skin has been reported to be relatively painless.5 Thus, NTAP maintains a distinct advantage over other commonly used nonpharmacologic treatment options, including curettage and cryosurgery. Curettage has widely been noted to be traumatic for the patient, may be more likely to leave a mark, and is prone to user error.20 Cryosurgery is a common form of treatment for MC because it is cost-effective and has good cosmetic results; however, it is more painful than cantharidin or anesthetized curettage.21 Treatment with NTAP is an emerging therapeutic tool with an expanding role in the treatment of dermatologic patients because it provides advantages over many standard therapies due to its minimal side-effect profile involving pain and nonpharmacologic nature.

Limitations of this report include exclusion of non–English-language articles and lack of control or comparison groups to standard therapies across studies. Additionally, reports of NTAP success occurred in many conditions that are self-limited and may have resolved on their own. Regardless, we aimed to summarize how NTAP currently is being used in pediatric populations and highlight its potential uses moving forward. Given its promising safety profile and painless nature, future clinical trials should prioritize the investigation of NTAP use in common pediatric dermatologic conditions to determine if they are equal or superior to current standards of care.

- Gan L, Zhang S, Poorun D, et al. Medical applications of nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:7-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13373

- Gay-Mimbrera J, García MC, Isla-Tejera B, et al. Clinical and biological principles of cold atmospheric plasma application in skin cancer. Adv Ther. 2016;33:894-909. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0338-1. Published correction appears in Adv Ther. 2017;34:280. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0437-z

- Zhai SY, Kong MG, Xia YM. Cold atmospheric plasma ameliorates skin diseases involving reactive oxygen/nitrogen species-mediated functions. Front Immunol. 2022;13:868386. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.868386

- Tan F, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. Plasma dermatology: skin therapy using cold atmospheric plasma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:918484. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.918484

- van Welzen A, Hoch M, Wahl P, et al. The response and tolerability of a novel cold atmospheric plasma wound dressing for the healing of split skin graft donor sites: a controlled pilot study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;34:328-336. doi:10.1159/000517524

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Using cold plasma to treat warts in children: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:706-709. doi:10.1111/pde.14180

- Zhang C, Zhao J, Gao Y, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment for diaper dermatitis: a case report [published online January 27, 2021]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14739. doi:10.1111/dth.14739

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma clears molluscum contagiosum. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:562-563. doi:10.1111/exd.14695

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. The efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of striae distensae: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6805-6814. doi:10.1111/jocd.15458

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. Efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of keloid: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6788-6797. doi:10.1111/jocd.15397

- Kim YJ, Lim DJ, Lee MY, et al. Prospective, comparative clinical pilot study of cold atmospheric plasma device in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14461. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93941-y

- Gareri C, Bennardo L, De Masi G. Use of a new cold plasma tool for psoriasis treatment: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20922709. doi:10.1177/2050313X20922709

- Zheng L, Gao J, Cao Y, et al. Two case reports of inverse psoriasis treated with cold atmospheric plasma. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14257. doi:10.1111/dth.14257

- Arisi M, Venturuzzo A, Gelmetti A, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) as a promising therapeutic option for mild to moderate acne vulgaris: clinical and non-invasive evaluation of two cases. Clin Plasma Med. 2020;19-20:100110.

- Isbary G, Köritzer J, Mitra A, et al. Ex vivo human skin experiments for the evaluation of safety of new cold atmospheric plasma devices. Clin Plasma Med. 2013;1:36-44.

- Sun T, Zhang X, Hou C, et al. Cold plasma irradiation attenuates atopic dermatitis via enhancing HIF-1α-induced MANF transcription expression. Front Immunol. 2022;13:941219. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.941219

- Eggers B, Marciniak J, Memmert S, et al. The beneficial effect of cold atmospheric plasma on parameters of molecules and cell function involved in wound healing in human osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Odontology. 2020;108:607-616. doi:10.1007/s10266-020-00487-y

- Conway GE, He Z, Hutanu AL, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma induces accumulation of lysosomes and caspase-independent cell death in U373MG glioblastoma multiforme cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12891. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49013-3

- Schmidt A, Dietrich S, Steuer A, et al. Non-thermal plasma activates human keratinocytes by stimulation of antioxidant and phase II pathways. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:6731-6750. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.603555

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:505-511. doi:10.2165/00148581-200305080-00001

- Cotton DW, Cooper C, Barrett DF, et al. Severe atypical molluscum contagiosum infection in an immunocompromised host. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:871-876. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04908.x

- Gan L, Zhang S, Poorun D, et al. Medical applications of nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:7-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13373

- Gay-Mimbrera J, García MC, Isla-Tejera B, et al. Clinical and biological principles of cold atmospheric plasma application in skin cancer. Adv Ther. 2016;33:894-909. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0338-1. Published correction appears in Adv Ther. 2017;34:280. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0437-z

- Zhai SY, Kong MG, Xia YM. Cold atmospheric plasma ameliorates skin diseases involving reactive oxygen/nitrogen species-mediated functions. Front Immunol. 2022;13:868386. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.868386

- Tan F, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. Plasma dermatology: skin therapy using cold atmospheric plasma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:918484. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.918484

- van Welzen A, Hoch M, Wahl P, et al. The response and tolerability of a novel cold atmospheric plasma wound dressing for the healing of split skin graft donor sites: a controlled pilot study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;34:328-336. doi:10.1159/000517524

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Using cold plasma to treat warts in children: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:706-709. doi:10.1111/pde.14180

- Zhang C, Zhao J, Gao Y, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment for diaper dermatitis: a case report [published online January 27, 2021]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14739. doi:10.1111/dth.14739

- Friedman PC, Fridman G, Fridman A. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma clears molluscum contagiosum. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:562-563. doi:10.1111/exd.14695

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. The efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of striae distensae: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6805-6814. doi:10.1111/jocd.15458

- Suwanchinda A, Nararatwanchai T. Efficacy and safety of the innovative cold atmospheric-pressure plasma technology in the treatment of keloid: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6788-6797. doi:10.1111/jocd.15397

- Kim YJ, Lim DJ, Lee MY, et al. Prospective, comparative clinical pilot study of cold atmospheric plasma device in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14461. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93941-y

- Gareri C, Bennardo L, De Masi G. Use of a new cold plasma tool for psoriasis treatment: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20922709. doi:10.1177/2050313X20922709

- Zheng L, Gao J, Cao Y, et al. Two case reports of inverse psoriasis treated with cold atmospheric plasma. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14257. doi:10.1111/dth.14257

- Arisi M, Venturuzzo A, Gelmetti A, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) as a promising therapeutic option for mild to moderate acne vulgaris: clinical and non-invasive evaluation of two cases. Clin Plasma Med. 2020;19-20:100110.

- Isbary G, Köritzer J, Mitra A, et al. Ex vivo human skin experiments for the evaluation of safety of new cold atmospheric plasma devices. Clin Plasma Med. 2013;1:36-44.

- Sun T, Zhang X, Hou C, et al. Cold plasma irradiation attenuates atopic dermatitis via enhancing HIF-1α-induced MANF transcription expression. Front Immunol. 2022;13:941219. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.941219

- Eggers B, Marciniak J, Memmert S, et al. The beneficial effect of cold atmospheric plasma on parameters of molecules and cell function involved in wound healing in human osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Odontology. 2020;108:607-616. doi:10.1007/s10266-020-00487-y

- Conway GE, He Z, Hutanu AL, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma induces accumulation of lysosomes and caspase-independent cell death in U373MG glioblastoma multiforme cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12891. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49013-3

- Schmidt A, Dietrich S, Steuer A, et al. Non-thermal plasma activates human keratinocytes by stimulation of antioxidant and phase II pathways. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:6731-6750. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.603555

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:505-511. doi:10.2165/00148581-200305080-00001

- Cotton DW, Cooper C, Barrett DF, et al. Severe atypical molluscum contagiosum infection in an immunocompromised host. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:871-876. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04908.x

Practice Points

- Nonthermal atmospheric plasma (NTAP)(also known as cold atmospheric plasma) has been shown to cause minimal damage to skin when application time is minimized.

- Beyond its diverse applications, treatment with NTAP yields a unique advantage to pharmacologic therapies in that there is no risk for medication interactions or pharmacologic adverse effects.

- Although the use of NTAP in pediatric dermatology is scarcely described in the literature, the technology will certainly have applications in the future treatment of a wide variety of pediatric disorders.

Dupilumab promising for children aged 1-11 with EoE

VANCOUVER –

High exposure to dupilumab was associated with significantly improved histologic, endoscopic, and transcriptomic improvements, compared with placebo at week 16. Sustained response or improvements continued to week 52 with continued treatment in the high-exposure dupilumab group. Children in the high-exposure dupilumab group also gained more weight during the study than those initially assigned to placebo.

“Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic, aggressive, type 2 inflammatory disease that has a substantial impact on quality of life,” said Mirna Chehade, MD, MPH, of the Mount Sinai Center for Eosinophilic Disorders, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. And the incidence and prevalence of the disease is increasing.

Dupilumab is already indicated for treating EoE in adolescents aged 12 or older as well as adults, but “there are no approved treatments for EoE in children under 12,” said Dr. Chehade, who presented the results of the late-breaking abstract at the ACG: American College of Gastroenterology 2023 annual scientific meeting.

She and her colleagues randomly assigned 102 children aged 1-11 years with active EoE to three groups for the first 16 weeks of the study: 37 to high-exposure dupilumab; 31 to low-exposure dupilumab; and 34 others to placebo, followed by either high- or low-dose dupilumab. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were comparable between groups.

During an active 36-week extension period, the 37 participants who were initially assigned to receive high-exposure dupilumab continued the same treatment up to week 52. A total of 29 participants initially assigned to receive low-exposure dupilumab continues their regimen as well. Those initially assigned to receive placebo switched to a preassigned active treatment group; 18 children started to take high-exposure dupilumab, and 14 began to take low-exposure dupilumab.

The children in the study had a high burden of disease, as reflected by the duration of EoE as well as histologic, endoscopic, and clinical scores. The mean age was 7.2 years in the placebo group and 6.8 years in the dupilumab group. They were mostly White boys, Dr. Chehade said.

Key outcomes

At week 16, the high-exposure dupilumab group met the primary study endpoint with a peak esophageal intraepithelial eosinophil count ≤ 6 on high-power field assessment. This was significantly different from the placebo group (least squares mean difference, 64.5; 95% confidence interval, 48.19-80.85; P < .0001).

At week 52, 63% of children who remained on high-exposure dupilumab and 53% of those who switched from placebo to high-exposure dupilumab achieved a peak eosinophil count ≤ 6.

The study included multiple secondary outcomes. For example, at week 16, the following measures improved from baseline with high-exposure dupilumab, compared with placebo:

- EoE-Histologic Scoring System grade and stage scores (–0.88 and –0.84 vs. +0.02 and +0.05; both P < .0001).

- EoE-Endoscopic Reference Score (–3.5 vs. +0.3; P < .0001).

- Change in body weight for age percentile (+3.09 vs. +0.29).

- Numeric improvement in caregiver-reported proportion of days experiencing one or more EoE sign (–0.28 vs. –0.17).

At week 52, these outcomes were sustained or improved with continued high-exposure dupilumab. The researchers also saw improvements among the placebo recipients who switched to high-exposure dupilumab.

The reason the children were randomly assigned to high-exposure or low-exposure groups instead of high-dose and low-dose cohorts is because the children grew during the study, Dr. Chehade explained. “As you can see, there was a nice change in weight, and at specific time periods the doses were adjusted to match.”

‘Good safety profile’

Dupilumab was well tolerated. “The safety profile is very similar to what has been so far described and published for dupilumab in adults,” said Dr. Chehade. At week 16, adverse events that were more frequent with dupilumab vs. placebo included COVID-19, rash, headache, and injection-site erythema, for example. Similar safety results were seen up to week 52.

“I think it’s promising as we wait for the actual study to be published,” said Asmeen Bhatt, MD, PhD, co-moderator of the session and assistant professor of medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. “The drug was recently approved for adult EOE use, just last year, and it has been shown to be effective.”

“There are a lot of adult drugs that are now being tested in the pediatric population, and this is one of them,” Dr. Bhatt added. “It has a very good safety profile. I’m not a pediatric gastroenterologist but I expect that it will have a lot of utility.”

The study was funded by Regeneron and Sanofi. Dr. Chehade is a consultant for Sanofi and Regeneron and receives research funding from Regeneron. Dr. Bhatt had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER –

High exposure to dupilumab was associated with significantly improved histologic, endoscopic, and transcriptomic improvements, compared with placebo at week 16. Sustained response or improvements continued to week 52 with continued treatment in the high-exposure dupilumab group. Children in the high-exposure dupilumab group also gained more weight during the study than those initially assigned to placebo.

“Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic, aggressive, type 2 inflammatory disease that has a substantial impact on quality of life,” said Mirna Chehade, MD, MPH, of the Mount Sinai Center for Eosinophilic Disorders, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. And the incidence and prevalence of the disease is increasing.

Dupilumab is already indicated for treating EoE in adolescents aged 12 or older as well as adults, but “there are no approved treatments for EoE in children under 12,” said Dr. Chehade, who presented the results of the late-breaking abstract at the ACG: American College of Gastroenterology 2023 annual scientific meeting.

She and her colleagues randomly assigned 102 children aged 1-11 years with active EoE to three groups for the first 16 weeks of the study: 37 to high-exposure dupilumab; 31 to low-exposure dupilumab; and 34 others to placebo, followed by either high- or low-dose dupilumab. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were comparable between groups.