User login

Focus on lifestyle to manage menopause symptoms after breast cancer

Lifestyle modification, rather than hormone therapy, should form the basis for managing estrogen-depletion symptoms and associated clinical problems in breast cancer survivors, according to a review of available evidence.

The review, conducted by the writing group for the Endocrine Society’s guidelines on management of menopausal symptoms, was prompted by the paucity of both randomized controlled trials in breast cancer survivors with estrogen deficiency issues and guidelines that sufficiently focus on treatment of this subgroup of women.

“A large proportion of women experience menopausal symptoms or clinical manifestations of estrogen deficiency during treatment of their breast cancer or after completion of therapy. The specific symptoms and clinical challenges differ based on menopausal status prior to initiation of cancer treatment and therapeutic agents used,” the researchers wrote in a report published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2017 Aug 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01138).

For instance, among premenopausal women treated with chemotherapy, ovarian insufficiency, severe menopausal symptoms, and infertility can result. Postmenopasual women treated with aromatase inhibitors may experience arthralgia, accelerated bone loss, and osteoporotic fractures, as well as severe vulvovaginal atrophy, they explained, noting that both premenopausal and postmenopausal survivors can experience moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbance with related fatigue, depressive symptoms, and mood changes.

“Less common problems include weight gain, symptomatic osteoarthritis and intervertebral disk degeneration, degenerative skin changes, radiation and chemotherapy-related cardiovascular disease, and reduced quality of life,” the researchers wrote.

Based on a review of randomized controlled clinical trials, observational studies, evidence-based guidelines, and expert opinion from professional societies, the writing group concluded that individualized lifestyle modifications and nonpharmacologic therapies are recommended for the treatment of these symptoms.

Specifically, the writing group recommended smoking cessation, weight loss when indicated, limited alcohol intake, maintenance of adequate vitamin D and calcium levels, a healthy diet, and regular physical activity for all women with prior breast cancer.

They also recommended nonpharmacologic therapies for vasomotor symptoms, and noted that cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, and acupuncture are among the approaches that may be helpful.

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers can also be helpful for mild vulvovaginal atrophy, they wrote. For women with more severe symptoms or signs of estrogen deficiency, pharmacologic agents are available to relieve vasomotor symptoms and vulvovaginal atrophy, and to prevent and treat fractures, they wrote, adding that “therapy must be individualized based on each woman’s needs and goals for therapy.”

Among emerging approaches to treatment of symptoms are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) therapy, estetrol, and neurokinin B inhibitors, which show promise for expanding options for symptom relief with less breast cancer risk. However, these have not yet been tested in women with prior breast cancer, the researchers noted.

Dr. Santen reported receiving research funding from Panterhei Bioscience. Other authors received research funding from Therapeutics MD and Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and honoraria from Abbott, Besins Health Care, and Pfizer.

Lifestyle modification, rather than hormone therapy, should form the basis for managing estrogen-depletion symptoms and associated clinical problems in breast cancer survivors, according to a review of available evidence.

The review, conducted by the writing group for the Endocrine Society’s guidelines on management of menopausal symptoms, was prompted by the paucity of both randomized controlled trials in breast cancer survivors with estrogen deficiency issues and guidelines that sufficiently focus on treatment of this subgroup of women.

“A large proportion of women experience menopausal symptoms or clinical manifestations of estrogen deficiency during treatment of their breast cancer or after completion of therapy. The specific symptoms and clinical challenges differ based on menopausal status prior to initiation of cancer treatment and therapeutic agents used,” the researchers wrote in a report published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2017 Aug 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01138).

For instance, among premenopausal women treated with chemotherapy, ovarian insufficiency, severe menopausal symptoms, and infertility can result. Postmenopasual women treated with aromatase inhibitors may experience arthralgia, accelerated bone loss, and osteoporotic fractures, as well as severe vulvovaginal atrophy, they explained, noting that both premenopausal and postmenopausal survivors can experience moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbance with related fatigue, depressive symptoms, and mood changes.

“Less common problems include weight gain, symptomatic osteoarthritis and intervertebral disk degeneration, degenerative skin changes, radiation and chemotherapy-related cardiovascular disease, and reduced quality of life,” the researchers wrote.

Based on a review of randomized controlled clinical trials, observational studies, evidence-based guidelines, and expert opinion from professional societies, the writing group concluded that individualized lifestyle modifications and nonpharmacologic therapies are recommended for the treatment of these symptoms.

Specifically, the writing group recommended smoking cessation, weight loss when indicated, limited alcohol intake, maintenance of adequate vitamin D and calcium levels, a healthy diet, and regular physical activity for all women with prior breast cancer.

They also recommended nonpharmacologic therapies for vasomotor symptoms, and noted that cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, and acupuncture are among the approaches that may be helpful.

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers can also be helpful for mild vulvovaginal atrophy, they wrote. For women with more severe symptoms or signs of estrogen deficiency, pharmacologic agents are available to relieve vasomotor symptoms and vulvovaginal atrophy, and to prevent and treat fractures, they wrote, adding that “therapy must be individualized based on each woman’s needs and goals for therapy.”

Among emerging approaches to treatment of symptoms are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) therapy, estetrol, and neurokinin B inhibitors, which show promise for expanding options for symptom relief with less breast cancer risk. However, these have not yet been tested in women with prior breast cancer, the researchers noted.

Dr. Santen reported receiving research funding from Panterhei Bioscience. Other authors received research funding from Therapeutics MD and Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and honoraria from Abbott, Besins Health Care, and Pfizer.

Lifestyle modification, rather than hormone therapy, should form the basis for managing estrogen-depletion symptoms and associated clinical problems in breast cancer survivors, according to a review of available evidence.

The review, conducted by the writing group for the Endocrine Society’s guidelines on management of menopausal symptoms, was prompted by the paucity of both randomized controlled trials in breast cancer survivors with estrogen deficiency issues and guidelines that sufficiently focus on treatment of this subgroup of women.

“A large proportion of women experience menopausal symptoms or clinical manifestations of estrogen deficiency during treatment of their breast cancer or after completion of therapy. The specific symptoms and clinical challenges differ based on menopausal status prior to initiation of cancer treatment and therapeutic agents used,” the researchers wrote in a report published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2017 Aug 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01138).

For instance, among premenopausal women treated with chemotherapy, ovarian insufficiency, severe menopausal symptoms, and infertility can result. Postmenopasual women treated with aromatase inhibitors may experience arthralgia, accelerated bone loss, and osteoporotic fractures, as well as severe vulvovaginal atrophy, they explained, noting that both premenopausal and postmenopausal survivors can experience moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbance with related fatigue, depressive symptoms, and mood changes.

“Less common problems include weight gain, symptomatic osteoarthritis and intervertebral disk degeneration, degenerative skin changes, radiation and chemotherapy-related cardiovascular disease, and reduced quality of life,” the researchers wrote.

Based on a review of randomized controlled clinical trials, observational studies, evidence-based guidelines, and expert opinion from professional societies, the writing group concluded that individualized lifestyle modifications and nonpharmacologic therapies are recommended for the treatment of these symptoms.

Specifically, the writing group recommended smoking cessation, weight loss when indicated, limited alcohol intake, maintenance of adequate vitamin D and calcium levels, a healthy diet, and regular physical activity for all women with prior breast cancer.

They also recommended nonpharmacologic therapies for vasomotor symptoms, and noted that cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, and acupuncture are among the approaches that may be helpful.

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers can also be helpful for mild vulvovaginal atrophy, they wrote. For women with more severe symptoms or signs of estrogen deficiency, pharmacologic agents are available to relieve vasomotor symptoms and vulvovaginal atrophy, and to prevent and treat fractures, they wrote, adding that “therapy must be individualized based on each woman’s needs and goals for therapy.”

Among emerging approaches to treatment of symptoms are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) therapy, estetrol, and neurokinin B inhibitors, which show promise for expanding options for symptom relief with less breast cancer risk. However, these have not yet been tested in women with prior breast cancer, the researchers noted.

Dr. Santen reported receiving research funding from Panterhei Bioscience. Other authors received research funding from Therapeutics MD and Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and honoraria from Abbott, Besins Health Care, and Pfizer.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Off-the-shelf T cells used to treat viral infections after HSCT

One-size-fits-all T cells designed to recognize and mount an immune response against five common viral pathogens may help to reduce the incidence of severe viral infections and treatment-related deaths in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), investigators reported.

Among 37 evaluable patients who had undergone an allogeneic HSCT, a single infusion of banked virus-specific T cells (VSTs) directed against adenovirus, BK virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was associated with a 92% cumulative complete or partial response rate, reported Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, and her colleagues from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Although a randomized trial will be required to definitively assess the value of banked VSTs, this study strongly suggests that off-the-shelf, multiple-virus–directed VSTs are a safe and effective broad-spectrum approach to treat severe viral infections after HSCT. These VSTs can be rapidly and cost effectively produced in scalable quantities with excellent long-term stability, which facilitates the broad implementation of this therapy,” they wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0655).

Although adoptive transfer of VSTs derived from donor stem cells has been shown to protect patients against viral pathogens, the technique is hampered by costs, complexity, the time-consuming manufacturing process, and the need for seropositive donors, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues pointed out.

“One way to overcome these limitations and to supply antiviral protection to recipients of allogeneic HSCT would be to prepare and cryopreserve banks of VST lines from healthy seropositive donors, which would be available for immediate use as an off-the-shelf product,” they wrote.

They tested this concept in a phase 2 clinical trial in 38 patients with a total of 45 infections.

A single infusion was associated with cumulative complete and partial responses rates of 71% in 7 patients with adenoviral infections, 100% in 16 patients with BK virus infections, 94% in 17 patients with CMV infections, 100% for 2 patients with EBV infections, and 67% for 3 patients with HHV-6 infections.

Seven of the 38 patients received VSTs for two viral infections, and all patients had viral control after a single infusion. All cases of CMV, adenovirus, and EBV infections were cleared from serum. One patient with HHV-6 encephalitis had complete resolution of encephalitis after one infusion and resolution of hemorrhagic cystitis after a second infusion; 14 patients with BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis had clinical improvement or resolution of disease.

The infusions were delivered safely. After infusion, one patient developed recurrent grade 3 gastrointestinal graft versus host disease (GVHD) after a rapid corticosteroid taper, three patients had recurrent grade 1 or 2 skin GVHD, and two patients had de novo skin GVHD. Of the five cases of skin GVHD, four resolved with the administration of topical treatments and one with the reinstitution of corticosteroids after a taper.

“More widespread and earlier use of this modality could minimize both drug-related and virus-associated complications and thereby decrease treatment-related mortality in recipients of allogeneic HSCT,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Conquer Cancer Foundation; and Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Tzannou disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with ViraCyte, and several coauthors reported financial ties with various companies.

One-size-fits-all T cells designed to recognize and mount an immune response against five common viral pathogens may help to reduce the incidence of severe viral infections and treatment-related deaths in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), investigators reported.

Among 37 evaluable patients who had undergone an allogeneic HSCT, a single infusion of banked virus-specific T cells (VSTs) directed against adenovirus, BK virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was associated with a 92% cumulative complete or partial response rate, reported Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, and her colleagues from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Although a randomized trial will be required to definitively assess the value of banked VSTs, this study strongly suggests that off-the-shelf, multiple-virus–directed VSTs are a safe and effective broad-spectrum approach to treat severe viral infections after HSCT. These VSTs can be rapidly and cost effectively produced in scalable quantities with excellent long-term stability, which facilitates the broad implementation of this therapy,” they wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0655).

Although adoptive transfer of VSTs derived from donor stem cells has been shown to protect patients against viral pathogens, the technique is hampered by costs, complexity, the time-consuming manufacturing process, and the need for seropositive donors, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues pointed out.

“One way to overcome these limitations and to supply antiviral protection to recipients of allogeneic HSCT would be to prepare and cryopreserve banks of VST lines from healthy seropositive donors, which would be available for immediate use as an off-the-shelf product,” they wrote.

They tested this concept in a phase 2 clinical trial in 38 patients with a total of 45 infections.

A single infusion was associated with cumulative complete and partial responses rates of 71% in 7 patients with adenoviral infections, 100% in 16 patients with BK virus infections, 94% in 17 patients with CMV infections, 100% for 2 patients with EBV infections, and 67% for 3 patients with HHV-6 infections.

Seven of the 38 patients received VSTs for two viral infections, and all patients had viral control after a single infusion. All cases of CMV, adenovirus, and EBV infections were cleared from serum. One patient with HHV-6 encephalitis had complete resolution of encephalitis after one infusion and resolution of hemorrhagic cystitis after a second infusion; 14 patients with BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis had clinical improvement or resolution of disease.

The infusions were delivered safely. After infusion, one patient developed recurrent grade 3 gastrointestinal graft versus host disease (GVHD) after a rapid corticosteroid taper, three patients had recurrent grade 1 or 2 skin GVHD, and two patients had de novo skin GVHD. Of the five cases of skin GVHD, four resolved with the administration of topical treatments and one with the reinstitution of corticosteroids after a taper.

“More widespread and earlier use of this modality could minimize both drug-related and virus-associated complications and thereby decrease treatment-related mortality in recipients of allogeneic HSCT,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Conquer Cancer Foundation; and Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Tzannou disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with ViraCyte, and several coauthors reported financial ties with various companies.

One-size-fits-all T cells designed to recognize and mount an immune response against five common viral pathogens may help to reduce the incidence of severe viral infections and treatment-related deaths in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), investigators reported.

Among 37 evaluable patients who had undergone an allogeneic HSCT, a single infusion of banked virus-specific T cells (VSTs) directed against adenovirus, BK virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was associated with a 92% cumulative complete or partial response rate, reported Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, and her colleagues from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Although a randomized trial will be required to definitively assess the value of banked VSTs, this study strongly suggests that off-the-shelf, multiple-virus–directed VSTs are a safe and effective broad-spectrum approach to treat severe viral infections after HSCT. These VSTs can be rapidly and cost effectively produced in scalable quantities with excellent long-term stability, which facilitates the broad implementation of this therapy,” they wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0655).

Although adoptive transfer of VSTs derived from donor stem cells has been shown to protect patients against viral pathogens, the technique is hampered by costs, complexity, the time-consuming manufacturing process, and the need for seropositive donors, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues pointed out.

“One way to overcome these limitations and to supply antiviral protection to recipients of allogeneic HSCT would be to prepare and cryopreserve banks of VST lines from healthy seropositive donors, which would be available for immediate use as an off-the-shelf product,” they wrote.

They tested this concept in a phase 2 clinical trial in 38 patients with a total of 45 infections.

A single infusion was associated with cumulative complete and partial responses rates of 71% in 7 patients with adenoviral infections, 100% in 16 patients with BK virus infections, 94% in 17 patients with CMV infections, 100% for 2 patients with EBV infections, and 67% for 3 patients with HHV-6 infections.

Seven of the 38 patients received VSTs for two viral infections, and all patients had viral control after a single infusion. All cases of CMV, adenovirus, and EBV infections were cleared from serum. One patient with HHV-6 encephalitis had complete resolution of encephalitis after one infusion and resolution of hemorrhagic cystitis after a second infusion; 14 patients with BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis had clinical improvement or resolution of disease.

The infusions were delivered safely. After infusion, one patient developed recurrent grade 3 gastrointestinal graft versus host disease (GVHD) after a rapid corticosteroid taper, three patients had recurrent grade 1 or 2 skin GVHD, and two patients had de novo skin GVHD. Of the five cases of skin GVHD, four resolved with the administration of topical treatments and one with the reinstitution of corticosteroids after a taper.

“More widespread and earlier use of this modality could minimize both drug-related and virus-associated complications and thereby decrease treatment-related mortality in recipients of allogeneic HSCT,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Conquer Cancer Foundation; and Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Tzannou disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with ViraCyte, and several coauthors reported financial ties with various companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Off-the-shelf virus-specific T-cell preparations can effectively treat infections following HSCT.

Major finding: Banked T cells directed against five common viruses were associated with a 92% cumulative partial or complete response rate.

Data source: Phase 2 clinical trial in 38 patients with viral infections following HSCT.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Conquer Cancer Foundation; and Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Tzannou disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with ViraCyte, and several coauthors reported financial ties with various companies.

Hospice care underused in older patients with de novo AML

Although adults older than 65 newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have a generally poor prognosis and short life expectancy, fewer than half were enrolled in hospice, and of those patients who were enrolled, two-thirds entered hospice within the last week of life, results of a retrospective cohort study show.

The findings suggest that there is substantial room for improvement in the care of older patients with AML in their last days of life, said investigators led by Rong Wang, PhD, and colleagues from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

“[We] found that the current end-of-life care for older patients with AML is suboptimal, as reflected by low hospice enrollment and high use of potentially aggressive treatment. Transfer in and out of hospice was associated with the receipt of transfusions. Changes to current hospice services, such as enabling the provision of transfusion support, and improvements in physician-patient communications, may help facilitate better end-of-life care in this patient population,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7149)

Patients aged 65 and over with AML have a median overall survival (OS) of only about 2 months, and the older the patient, the worse the survival, with patients 85 and older having a median OS of just 1 month, the investigators noted.

“Hence, end-of-life care is particularly relevant for this patient population,” they wrote.

To get a better idea of how clinicians prescribe hospice and palliative care for older patients with AML, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of patients with AML who were 66 or older at diagnosis, received a diagnosis from 1999 through 2011, and died before the end of 2012.

They reviewed Medicare claims data on 13,156 patients to see whether patients were receiving aggressive care such as chemotherapy and whether and when they were enrolled in hospice.

The investigators found that the proportion of patients who were enrolled in hospice after an AML diagnosis increased from 31.3% in 1999 to 56.4% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

They also discovered, however, that most of the increase was attributable to patients who were enrolled within the last week of life.

When they compared patients who died within 30 days of diagnosis to those who lived longer than 30 days after diagnosis, they found that the longer-lived patients were significantly more likely to have been enrolled in hospice (48.1% vs. 30.7%, P less than .01). Additionally, of those patients who were enrolled in hospice, 51.2% of those who died within 30 days of entering hospice had been enrolled in the last 3 days of life, compared with 24.9% of those who survived for more than a month after entering hospice (P value not shown).

Over the course of the study 1,528 patients (11.6%) had chemotherapy within their last two weeks of life. The proportion of patients undergoing chemotherapy within their last 14 days increased from 7.7% in 1999 to 18.8% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

Patients who had end-of-life chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have had an ICU stay in the last month of life (43.0% vs. 28.4%; P less than .01) and were significantly more likely to be enrolled in hospice (22.1% vs. 47.4%, P less than .01) than patients who did not get chemotherapy with the last 14 days of life.

Predictors for end-of-life chemotherapy were male sex, being married, and dying in more recent years. Patients who were older, had state Medicaid buy-in (an optional program for workers with disabilities), or who lived outside the Northeast or major metropolitan areas were less likely to be subjected to chemotherapy in their final days.

Overall, 3,956 patients (30.1%) were admitted to the ICU within 30 days of their deaths. The percentage of ICU admissions just before death increased from 25.2% in 1999 to 31.3% in 2012 (P for trend .01).

Predictors for late-life ICU admission were similar to those for chemotherapy, except that patients with state Medicaid buy-in had 19% greater odds of being admitted to an ICU within 30 days of death (P less than .01).

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Wang reported no relevant conflicts of interests. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies.

Although adults older than 65 newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have a generally poor prognosis and short life expectancy, fewer than half were enrolled in hospice, and of those patients who were enrolled, two-thirds entered hospice within the last week of life, results of a retrospective cohort study show.

The findings suggest that there is substantial room for improvement in the care of older patients with AML in their last days of life, said investigators led by Rong Wang, PhD, and colleagues from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

“[We] found that the current end-of-life care for older patients with AML is suboptimal, as reflected by low hospice enrollment and high use of potentially aggressive treatment. Transfer in and out of hospice was associated with the receipt of transfusions. Changes to current hospice services, such as enabling the provision of transfusion support, and improvements in physician-patient communications, may help facilitate better end-of-life care in this patient population,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7149)

Patients aged 65 and over with AML have a median overall survival (OS) of only about 2 months, and the older the patient, the worse the survival, with patients 85 and older having a median OS of just 1 month, the investigators noted.

“Hence, end-of-life care is particularly relevant for this patient population,” they wrote.

To get a better idea of how clinicians prescribe hospice and palliative care for older patients with AML, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of patients with AML who were 66 or older at diagnosis, received a diagnosis from 1999 through 2011, and died before the end of 2012.

They reviewed Medicare claims data on 13,156 patients to see whether patients were receiving aggressive care such as chemotherapy and whether and when they were enrolled in hospice.

The investigators found that the proportion of patients who were enrolled in hospice after an AML diagnosis increased from 31.3% in 1999 to 56.4% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

They also discovered, however, that most of the increase was attributable to patients who were enrolled within the last week of life.

When they compared patients who died within 30 days of diagnosis to those who lived longer than 30 days after diagnosis, they found that the longer-lived patients were significantly more likely to have been enrolled in hospice (48.1% vs. 30.7%, P less than .01). Additionally, of those patients who were enrolled in hospice, 51.2% of those who died within 30 days of entering hospice had been enrolled in the last 3 days of life, compared with 24.9% of those who survived for more than a month after entering hospice (P value not shown).

Over the course of the study 1,528 patients (11.6%) had chemotherapy within their last two weeks of life. The proportion of patients undergoing chemotherapy within their last 14 days increased from 7.7% in 1999 to 18.8% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

Patients who had end-of-life chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have had an ICU stay in the last month of life (43.0% vs. 28.4%; P less than .01) and were significantly more likely to be enrolled in hospice (22.1% vs. 47.4%, P less than .01) than patients who did not get chemotherapy with the last 14 days of life.

Predictors for end-of-life chemotherapy were male sex, being married, and dying in more recent years. Patients who were older, had state Medicaid buy-in (an optional program for workers with disabilities), or who lived outside the Northeast or major metropolitan areas were less likely to be subjected to chemotherapy in their final days.

Overall, 3,956 patients (30.1%) were admitted to the ICU within 30 days of their deaths. The percentage of ICU admissions just before death increased from 25.2% in 1999 to 31.3% in 2012 (P for trend .01).

Predictors for late-life ICU admission were similar to those for chemotherapy, except that patients with state Medicaid buy-in had 19% greater odds of being admitted to an ICU within 30 days of death (P less than .01).

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Wang reported no relevant conflicts of interests. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies.

Although adults older than 65 newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have a generally poor prognosis and short life expectancy, fewer than half were enrolled in hospice, and of those patients who were enrolled, two-thirds entered hospice within the last week of life, results of a retrospective cohort study show.

The findings suggest that there is substantial room for improvement in the care of older patients with AML in their last days of life, said investigators led by Rong Wang, PhD, and colleagues from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

“[We] found that the current end-of-life care for older patients with AML is suboptimal, as reflected by low hospice enrollment and high use of potentially aggressive treatment. Transfer in and out of hospice was associated with the receipt of transfusions. Changes to current hospice services, such as enabling the provision of transfusion support, and improvements in physician-patient communications, may help facilitate better end-of-life care in this patient population,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7149)

Patients aged 65 and over with AML have a median overall survival (OS) of only about 2 months, and the older the patient, the worse the survival, with patients 85 and older having a median OS of just 1 month, the investigators noted.

“Hence, end-of-life care is particularly relevant for this patient population,” they wrote.

To get a better idea of how clinicians prescribe hospice and palliative care for older patients with AML, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of patients with AML who were 66 or older at diagnosis, received a diagnosis from 1999 through 2011, and died before the end of 2012.

They reviewed Medicare claims data on 13,156 patients to see whether patients were receiving aggressive care such as chemotherapy and whether and when they were enrolled in hospice.

The investigators found that the proportion of patients who were enrolled in hospice after an AML diagnosis increased from 31.3% in 1999 to 56.4% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

They also discovered, however, that most of the increase was attributable to patients who were enrolled within the last week of life.

When they compared patients who died within 30 days of diagnosis to those who lived longer than 30 days after diagnosis, they found that the longer-lived patients were significantly more likely to have been enrolled in hospice (48.1% vs. 30.7%, P less than .01). Additionally, of those patients who were enrolled in hospice, 51.2% of those who died within 30 days of entering hospice had been enrolled in the last 3 days of life, compared with 24.9% of those who survived for more than a month after entering hospice (P value not shown).

Over the course of the study 1,528 patients (11.6%) had chemotherapy within their last two weeks of life. The proportion of patients undergoing chemotherapy within their last 14 days increased from 7.7% in 1999 to 18.8% in 2012 (P for trend less than .01).

Patients who had end-of-life chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have had an ICU stay in the last month of life (43.0% vs. 28.4%; P less than .01) and were significantly more likely to be enrolled in hospice (22.1% vs. 47.4%, P less than .01) than patients who did not get chemotherapy with the last 14 days of life.

Predictors for end-of-life chemotherapy were male sex, being married, and dying in more recent years. Patients who were older, had state Medicaid buy-in (an optional program for workers with disabilities), or who lived outside the Northeast or major metropolitan areas were less likely to be subjected to chemotherapy in their final days.

Overall, 3,956 patients (30.1%) were admitted to the ICU within 30 days of their deaths. The percentage of ICU admissions just before death increased from 25.2% in 1999 to 31.3% in 2012 (P for trend .01).

Predictors for late-life ICU admission were similar to those for chemotherapy, except that patients with state Medicaid buy-in had 19% greater odds of being admitted to an ICU within 30 days of death (P less than .01).

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Wang reported no relevant conflicts of interests. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: End-of-life care for patients 65 and older with acute myeloid leukemia is suboptimal.

Major finding: Patients who lived more than 30 days after an AML diagnosis were significantly more likely to have been enrolled in hospice than those who died within 30 days of diagnosis.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 13,156 patients diagnosed with AML at age 66 or older from 1999 through 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Wang reported no relevant conflicts of interests. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies.

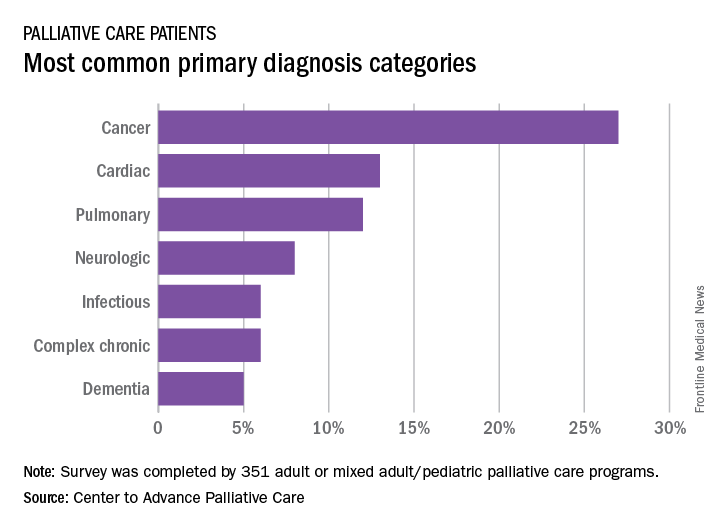

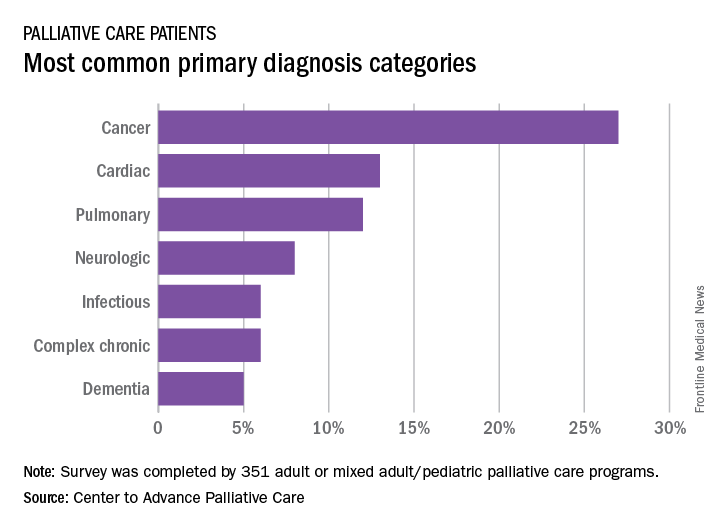

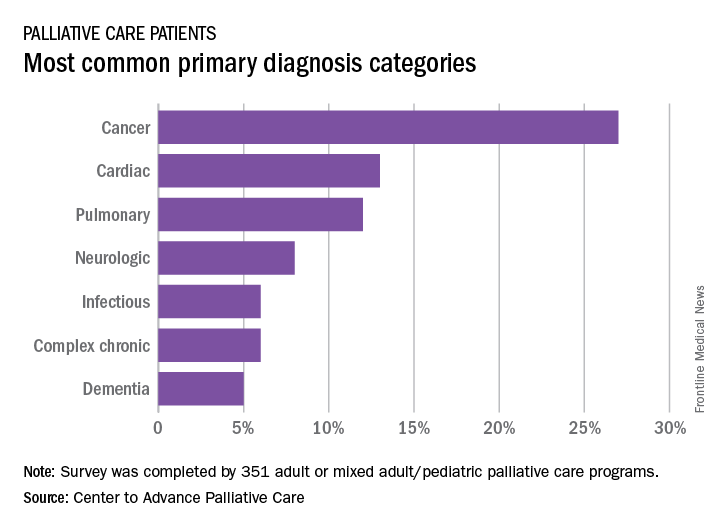

Cancer the most common diagnosis in palliative care patients

More than a quarter of the patients in palliative care have a primary diagnosis of cancer, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

A survey of 351 palliative care programs showed that 27% of their patients had been diagnosed with cancer in 2016, more than twice as many patients who had a cardiac (13%) or pulmonary (12%) diagnosis. The next most common primary diagnosis category in 2016 was neurologic at 8%, with a tie at 6% between diagnoses classified as infectious or complex chronic, followed by patients with dementia at 5%, Maggie Rogers and Tamara Dumanovsky, PhD, of the CAPC reported.

A medical/surgical unit was the referring site for 43% of palliative care referrals in 2016, with 26% of patients coming from an intensive care unit, 13% from a step-down unit, and 8% from an oncology unit, they noted.

More than a quarter of the patients in palliative care have a primary diagnosis of cancer, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

A survey of 351 palliative care programs showed that 27% of their patients had been diagnosed with cancer in 2016, more than twice as many patients who had a cardiac (13%) or pulmonary (12%) diagnosis. The next most common primary diagnosis category in 2016 was neurologic at 8%, with a tie at 6% between diagnoses classified as infectious or complex chronic, followed by patients with dementia at 5%, Maggie Rogers and Tamara Dumanovsky, PhD, of the CAPC reported.

A medical/surgical unit was the referring site for 43% of palliative care referrals in 2016, with 26% of patients coming from an intensive care unit, 13% from a step-down unit, and 8% from an oncology unit, they noted.

More than a quarter of the patients in palliative care have a primary diagnosis of cancer, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

A survey of 351 palliative care programs showed that 27% of their patients had been diagnosed with cancer in 2016, more than twice as many patients who had a cardiac (13%) or pulmonary (12%) diagnosis. The next most common primary diagnosis category in 2016 was neurologic at 8%, with a tie at 6% between diagnoses classified as infectious or complex chronic, followed by patients with dementia at 5%, Maggie Rogers and Tamara Dumanovsky, PhD, of the CAPC reported.

A medical/surgical unit was the referring site for 43% of palliative care referrals in 2016, with 26% of patients coming from an intensive care unit, 13% from a step-down unit, and 8% from an oncology unit, they noted.

VHA warns California clinicians on assisted suicide

SAN DIEGO – The Veterans Health Administration has issued strict rules forbidding clinicians from doing anything to help patients kill themselves via physician-assisted suicide, which is now legal in certain cases in California, according to a psychiatrist who updated colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The VHA says clinicians may not make referrals to physicians who help patients commit suicide, said Kristin Beizai, MD, who is affiliated with the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Nor can they provide information about patient diagnoses outside of medical records or complete forms to support physician aid-in-dying (PAD), she said.

The VA San Diego system received queries from patients about assisted suicide even before the law in mid-2016 allowed physicians to provide deadly medications to some patients, said Dr. Beizai, who’s also with the University of California, San Diego.

“There was a lot of attention coming before the law was active,” she said, and more questions from patients arose after that time.

In addition to California, four other states (Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) – and the District of Columbia – allow terminally ill people who meet certain conditions to commit suicide with the assistance of physicians. In addition, a court ruling in Montana appears to allow PAD there.

California’s law allowing PAD took effect after Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015 signed a bill passed by the legislature.

According to a recent report from the state of California, 111 people killed themselves during June-December 2016 by taking deadly medication prescribed by physicians. The patients must self-administer the medications. Of those 111 people, 90% were white, and most had college degrees. The majority had cancer.

The report also said 173 physicians had written 191 total lethal prescriptions, suggesting some patients – perhaps dozens – had not taken the drugs by the end of 2016.

In response to a query from Dr. Beizai about policies regarding PAD, VHA ethics officials sent word that clinicians must butt out when it comes to assisted suicide: “No practitioner functioning within his or her scope of duty may participate in fulfilling requests for euthanasia or PAD,” they said, regardless of what state law allows.

According to the VHA:

- Clinicians may not support PAD through any means, including referrals and evaluations, and federal funds may not be used for PAD.

- Clinicians cannot fill out forms supporting PAD. However, they must not hinder the release of medical records when requested by an outside provider.

- Patients can seek PAD outside of the VHA system if they wish. Patients who ask about PAD must be told that the VHA doesn’t offer the service. “We need to inform them very directly that we do not provide it and are not allowed to participate,” Dr. Beizai said.

- If a patient makes a request regarding PAD, the VHA clinician “must explore the source of the patient’s request and respond with the best possible, medically appropriate care that is consistent with legal standards and is legally permissible.”

Clinicians are encouraged to explore issues like pain, depression, fears, and anxiety, Dr. Beizai said. The VHA has set up a six-step protocol on this front.

But the VHA is making it clear that patients who seek PAD elsewhere must not be abandoned. “Don’t disconnect from the patients if they determine they want to go that route,” said Dr. Beizai, who gave that message to VA San Diego staffers during an educational outreach program regarding PAD.

Dr. Beizai reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The Veterans Health Administration has issued strict rules forbidding clinicians from doing anything to help patients kill themselves via physician-assisted suicide, which is now legal in certain cases in California, according to a psychiatrist who updated colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The VHA says clinicians may not make referrals to physicians who help patients commit suicide, said Kristin Beizai, MD, who is affiliated with the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Nor can they provide information about patient diagnoses outside of medical records or complete forms to support physician aid-in-dying (PAD), she said.

The VA San Diego system received queries from patients about assisted suicide even before the law in mid-2016 allowed physicians to provide deadly medications to some patients, said Dr. Beizai, who’s also with the University of California, San Diego.

“There was a lot of attention coming before the law was active,” she said, and more questions from patients arose after that time.

In addition to California, four other states (Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) – and the District of Columbia – allow terminally ill people who meet certain conditions to commit suicide with the assistance of physicians. In addition, a court ruling in Montana appears to allow PAD there.

California’s law allowing PAD took effect after Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015 signed a bill passed by the legislature.

According to a recent report from the state of California, 111 people killed themselves during June-December 2016 by taking deadly medication prescribed by physicians. The patients must self-administer the medications. Of those 111 people, 90% were white, and most had college degrees. The majority had cancer.

The report also said 173 physicians had written 191 total lethal prescriptions, suggesting some patients – perhaps dozens – had not taken the drugs by the end of 2016.

In response to a query from Dr. Beizai about policies regarding PAD, VHA ethics officials sent word that clinicians must butt out when it comes to assisted suicide: “No practitioner functioning within his or her scope of duty may participate in fulfilling requests for euthanasia or PAD,” they said, regardless of what state law allows.

According to the VHA:

- Clinicians may not support PAD through any means, including referrals and evaluations, and federal funds may not be used for PAD.

- Clinicians cannot fill out forms supporting PAD. However, they must not hinder the release of medical records when requested by an outside provider.

- Patients can seek PAD outside of the VHA system if they wish. Patients who ask about PAD must be told that the VHA doesn’t offer the service. “We need to inform them very directly that we do not provide it and are not allowed to participate,” Dr. Beizai said.

- If a patient makes a request regarding PAD, the VHA clinician “must explore the source of the patient’s request and respond with the best possible, medically appropriate care that is consistent with legal standards and is legally permissible.”

Clinicians are encouraged to explore issues like pain, depression, fears, and anxiety, Dr. Beizai said. The VHA has set up a six-step protocol on this front.

But the VHA is making it clear that patients who seek PAD elsewhere must not be abandoned. “Don’t disconnect from the patients if they determine they want to go that route,” said Dr. Beizai, who gave that message to VA San Diego staffers during an educational outreach program regarding PAD.

Dr. Beizai reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The Veterans Health Administration has issued strict rules forbidding clinicians from doing anything to help patients kill themselves via physician-assisted suicide, which is now legal in certain cases in California, according to a psychiatrist who updated colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The VHA says clinicians may not make referrals to physicians who help patients commit suicide, said Kristin Beizai, MD, who is affiliated with the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Nor can they provide information about patient diagnoses outside of medical records or complete forms to support physician aid-in-dying (PAD), she said.

The VA San Diego system received queries from patients about assisted suicide even before the law in mid-2016 allowed physicians to provide deadly medications to some patients, said Dr. Beizai, who’s also with the University of California, San Diego.

“There was a lot of attention coming before the law was active,” she said, and more questions from patients arose after that time.

In addition to California, four other states (Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) – and the District of Columbia – allow terminally ill people who meet certain conditions to commit suicide with the assistance of physicians. In addition, a court ruling in Montana appears to allow PAD there.

California’s law allowing PAD took effect after Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015 signed a bill passed by the legislature.

According to a recent report from the state of California, 111 people killed themselves during June-December 2016 by taking deadly medication prescribed by physicians. The patients must self-administer the medications. Of those 111 people, 90% were white, and most had college degrees. The majority had cancer.

The report also said 173 physicians had written 191 total lethal prescriptions, suggesting some patients – perhaps dozens – had not taken the drugs by the end of 2016.

In response to a query from Dr. Beizai about policies regarding PAD, VHA ethics officials sent word that clinicians must butt out when it comes to assisted suicide: “No practitioner functioning within his or her scope of duty may participate in fulfilling requests for euthanasia or PAD,” they said, regardless of what state law allows.

According to the VHA:

- Clinicians may not support PAD through any means, including referrals and evaluations, and federal funds may not be used for PAD.

- Clinicians cannot fill out forms supporting PAD. However, they must not hinder the release of medical records when requested by an outside provider.

- Patients can seek PAD outside of the VHA system if they wish. Patients who ask about PAD must be told that the VHA doesn’t offer the service. “We need to inform them very directly that we do not provide it and are not allowed to participate,” Dr. Beizai said.

- If a patient makes a request regarding PAD, the VHA clinician “must explore the source of the patient’s request and respond with the best possible, medically appropriate care that is consistent with legal standards and is legally permissible.”

Clinicians are encouraged to explore issues like pain, depression, fears, and anxiety, Dr. Beizai said. The VHA has set up a six-step protocol on this front.

But the VHA is making it clear that patients who seek PAD elsewhere must not be abandoned. “Don’t disconnect from the patients if they determine they want to go that route,” said Dr. Beizai, who gave that message to VA San Diego staffers during an educational outreach program regarding PAD.

Dr. Beizai reported no relevant disclosures.

AT APA

Perceived financial hardship among patients with advanced cancer

The American Cancer Society has identified a disparity in cancer death rates, noting that persons with lower socioeconomic status have higher rates of mortality.1 This is attributed to many factors, but it is largely owing to the higher burden of disease among lower-income individuals.1 A component of this disease burden is measured by assessing the patient-reported outcome of cancer-related distress. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Management Guidelines have defined distress as “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope with cancer, its physical symptoms and its treatment.”2

Financial hardship related to cancer diagnosis and treatment is increasingly being recognized as an important component of disease burden and distress. The advancements in costly cancer treatments have produced burdensome direct medical costs as well as numerous indirect costs that contribute to perceived financial hardship.3,4 These indirect costs include nonmedical expenses such as increased transportation needs or childcare, loss of earnings, or loss of household income due to caregiving needs.3 Moreover, indirect costs are often managed by patients and families through their use of savings, borrowing, reducing leisure activities, and selling possessions.3 Even though efforts to increase health coverage, such as the Affordable Care Act, have reduced the rates of individuals who are uninsured, persons with cancer who have insurance also face challenges because they cannot afford copays, monthly premiums, deductibles, and other high out-of-pocket expenses related to cancer treatment that are not covered by their insurance such as out-of-network services or providers.5-7

Thus, financial hardship may have an impact on several areas of a patient’s life and well-being, but the effects are commonly undetected.8-10 Research has established that financial strain can influence treatment choices and adherence to therapy.11 Furthermore, the effects of financial strain have been identified across the cancer care continuum, from diagnosis through survivorship, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between financial strain and well-being.11 Financial strain may reduce patient quality of life and worsen symptom burden because of the patient’s inability to access needed care, poor social supports, and/or increased stress.11-12 These worsening outcomes may also increase the use of financial reserves and affect their ability to work.7,11 Financial difficulties may also be associated with anxiety and depression, leading to worse quality of life and greater distress and symptom burden.12 Identifying groups at high risk for financial strain is crucial to ensure that resources are available to assist these populations.13 This burden can be even more pronounced in minority and underserved patients with cancer.7 Patients with advanced cancer are especially vulnerable to the burden of increased costs because of the use of expensive targeted therapies; their improved survival, which extends the time of expenditure; and increased use of financial reserves.9 Financial hardship in patients with advanced cancer is not well understood or characterized,9 which is why this study aimed to better quantify distress in advanced stage cancers by describing :

▪ A cohort of patients with advanced cancer and their levels of quality of life, symptom distress, cancer-related distress and perceived financial hardship;

▪ The relationship between perceived financial hardship, quality of life, symptom distress and overall cancer-related distress; and

▪ Quality of life, symptom distress, and overall cancer-related distress according to level of perceived financial hardship.

Methods

This study is a cross-sectional, descriptive, comparative study of distress, including perceived financial hardship, among patients with advanced cancer who were receiving palliative care treatment in two outpatient medical oncology clinics in Western Pennsylvania. The data were collected during May 2013-November 2014. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. Eligible participants had to be 18 years or older and have an advanced solid tumor of any kind, with a prognosis of 1 year or less confirmed by a physician or clinic nurse practitioner/physician assistant, and be able to read and understand English at the fourth-grade level. The sample was recruited from two clinics at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Program.

Measurements

Sociodemographic factors. These were measured using an investigator-derived Sociodemographic Questionnaire, a 12-item form that includes variables such as age, race, marital status, cancer type, religion and spirituality, employment status, years of education, health insurance status, and income level.

Cancer-related distress. The NCCN Distress Thermometer is a self-report visual analog scale (0, no distress; 10, great distress) formed in the shape of a thermometer combined with a problem list that is often used in outpatient cancer settings for reporting of cancer-related distress.14-16 The sensitivity, specificity and convergent validity with the Brief Symptom Inventory and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale have been established and appropriate cut-off score of the distress thermometer identified.14-16 A score of 4 or above indicates a clinically significant level of distress.14-16

Symptom distress. The McCorkle Symptom Distress Scale was developed in 1977 based on interviews that focused on the symptom experiences of patients. Psychometric testing among patients with cancer using the modified Symptom Distress Scale revealed high reliability (Cronbach alpha, 0.97).17 The instrument is a 13-item Likert scale (1-5) assessing the severity of distress experienced by a symptom. Total scores range from 13 to 65, where a higher score indicates greater distress. Moderate distress is indicated with a score of 25-33, and a score above 33 indicates severe distress, identifying the need for immediate intervention.17

Quality of life and spiritual well-being. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) is used to assess general cancer-related quality of life. It has four subscales: physical, emotional, social and family, and functional well-being, with a total score that ranges from 0-112, where higher scores show higher quality of life. The Spiritual Distress Well-Being questionnaire was used alongside the valid FACT-G assessment.18,19 The Spiritual Well-Being Short Form was developed with an ethnically diverse population and adds 12 items to the FACT-G. The items do not necessarily assume a faith in God, allowing a wide flexibility in application and tapping into issues such as faith, meaning, and finding peace and comfort despite advanced illness. Higher scores on the Spiritual Well-Being subscore (range, 0-48) are correlated with higher scores of quality of life. The possible scores for the combined FACT-G and Spiritual Well-Being assessment range from 0-160, with higher scores showing higher quality of life.

Economic hardship. Perceived financial hardship was measured using Barrera and colleagues’ Psychological Sense of Economic Hardship Scale. 20 The scale consists of 20-items broken down into 4 subscales: financial strain, inability to make ends meet, not enough money for necessities, and economic adjustments.20 Economic adjustments in the 3 months before administration of the questionnaire were assessed with 9 Yes or No items, such as added another job, received government assistance, or sold possessions to increase income. The subscale of not enough money for necessities was assessed with seven 5-point scale items in which respondents noted whether they felt they had enough money for housing, clothing, home furnishings, and a car over the previous 3 months. Inability to make ends meet included two 5-point scale items that assessed the difficulty in meeting financial demands in the previous 3 months. Financial strain consisted of two 5-point scale items concerned with expecting financial hardships in the coming 3 months. Scores can range from 20-73, with a higher score indicating worse economic hardship.

Data collection and analysis

In-person data collection occurred in the clinical waiting area before the clinician visit or in the treatment room with the patient using a consecutive, convenience sample. The nursing staff checked the clinic lists daily for possible patient participants. Patients with metastatic cancer were identified and then approached for consent. After we had received the patient’s consent, the administration of the instruments took about 20 minutes to complete. The data were then entered and verified in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), which is hosted at the University of Pittsburgh.21The levels of symptom distress, quality of life, perceived financial hardship, and cancer-related distress were described through continuously measured variables. Descriptive statistics, measures of central tendency (mean and median), and dispersion (standard deviation and range), were obtained for the subscales and total scores. Correlation analysis was used to describe the relationship between perceived financial hardship and quality of life, symptom distress, and cancer-related distress. These primary outcome variables were further explored according to the level of dichotomized perceived financial hardship using mean score as the cut point. Independent sample t tests were used to compare patients experiencing high perceived financial hardship with those experiencing low perceived financial hardship.

Results

In all, 100 patients participated in the study. Any missing data points were replaced with the mean score for that variable, although this was minimal in this study. Most of the participants were women (67%), and the average age of the participants was 63.43 years (SD, 13.05; Table 1). Of the total number of participants, 73% were white, 26% were black, and 1% were Asian. Most of the participants were either retired and not working (39%) or disabled or unable to work (34%). Almost all of the participants had some form of insurance, with 99% having either private or public health insurance. A variety of cancer types were represented in this patient population, with higher percentages of breast (25%), gynecologic (10%), lung (19%), and colon/rectal cancer (15%). Of the total number of participants, 35% had annual household incomes below $20,000, and 50% had annual household incomes of more than $20,000. On average, participants had 13.48 years (SD, 2.78) of formal education.

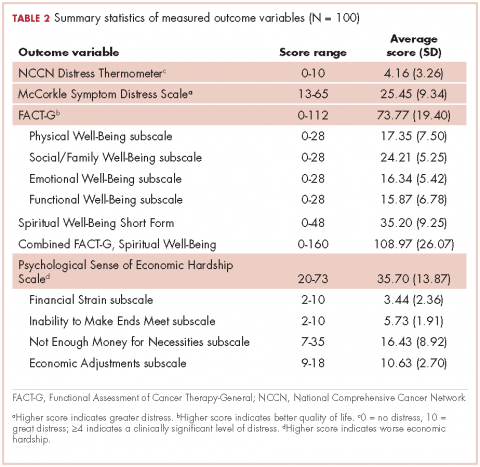

Descriptive statistics for the primary outcome variables can be found in Table 2. The average score for cancer-related distress based on the NCCN Distress Thermometer tool was 4.16 (SD, 3.26). The average score for the McCorkle Symptom Distress measurement was 25.45 (SD, 9.34). For quality of life, the average FACT-G total score was 73.77 (SD, 19.40). Of the FACT-G subscale average scores, physical well-being was 17.35 (SD, 7.50), social/family well-being 24.21 (SD, 5.25), emotional well-being 16.34 (SD, 5.42), and functional well-being 15.87 (SD, 6.78). Participants’ average score for the spiritual well-being measure was 35.20 (SD, 9.25) and the combined FACT-G and spiritual well-being average score was 108.97 (SD, 26.07). The total average score for perceived financial hardship was 35.70 (SD, 13.87), with subscale average scores of 3.44 (SD, 2.36) for financial strain, 5.73 (SD, 1.91) for inability to make ends meet, 16.43 (SD, 8.92) for not enough money for necessities, and 10.63 (SD, 2.70) for economic adjustments.

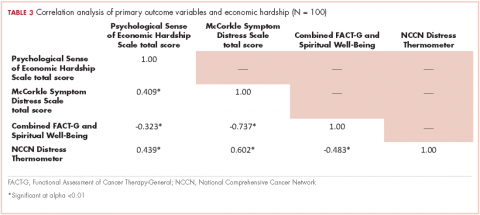

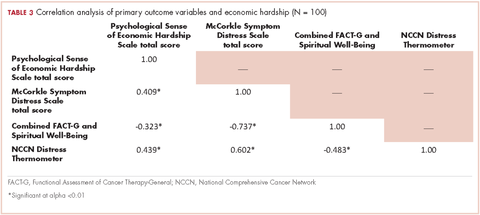

We conducted a bivariate correlation analysis to assess the relationship between perceived financial hardship and three other primary outcome variables (Table 3). These analyses showed significant low to moderate correlations with overall cancer-related distress (r, 0.439; P < .001), symptom distress (r, 0.409; P < .001) and overall quality of life scores (FACT-G and spiritual well-being combined score: r, -0.323; P < .001).

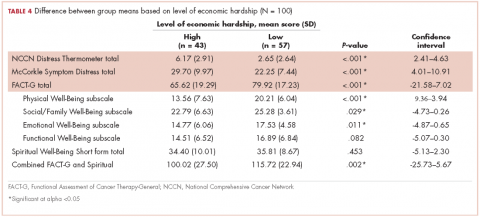

Forty-three participants reporting high perceived financial hardship experienced worse quality of life overall (FACT-G and spiritual well-being; P = .002), worse FACT-G total scores (P < .001), worse physical well-being (P < .001), worse social/family well-being (P = .029), worse emotional well-being, and no significant difference for functional (P = .082) or spiritual well-being (P = .453), compared with those with lower economic hardship. In overall cancer-related distress, participants with higher perceived financial hardship reported higher levels of cancer-related distress (P < .001) than those with lower perceived financial hardship. For those participants reporting higher perceived financial hardship there was also worse symptom distress (P < .001), compared with those with lower economic hardship (Table 4).

Discussion

Overall, this report provides data to illuminate our understanding of disparities in well-being that may be present in patients with advanced cancer. Our analysis found that patients with advanced cancer who have higher perceived financial hardship have significantly higher overall cancer-related distress, symptom distress, and poorer overall quality of life. In this study’s population of patients with advanced cancer, the most notable areas of economic hardship identified by participants were: not having enough money for necessities in the 3 months before the survey and the inability to make ends meet during the same time span, with difficulty paying bills and not having enough money left at the end of the month being most noteworthy among this study’s patient population. Financial strain and making economic adjustment were not as notable in the category of perceived financial hardship.

In regard to not having enough money, participants most commonly cited not being able to afford everyday necessities such as food, clothing, medical care, or a home, as well as leisure and recreational activities. These findings are further supported with the positive, moderate associations between perceived financial hardship and symptom distress and overall cancer-related distress found in this cohort of patients with advanced cancer and the negative, moderately associated relationship between perceived financial hardship and overall quality of life in this study’s sample.

Although these findings have been confirmed in the literature on cancer-related distress, our findings add to our knowledge on both economic and cancer-related distress exclusively in patients with advanced cancer.9,22 The broader cancer-related distress literature has also found an association between being younger and having a lower household income as risk factors for increased financial hardship; however, the perception of financial strain and magnitude was a more significant predictor of quality of life and perception of overall well-being.6,8-9,12,22-23 Furthermore, patients with cancer who noted having higher financial distress typically reported decreased satisfaction with cancer care which also influenced their adherence to treatment and quality of life.24

Our work now adds the important element of perceived financial hardship to the advanced cancer-related distress puzzle. We should consider integrating a financial distress assessment into routine cancer care, particularly with patients and families with advanced cancer, to proactively and routinely assess and intervene with available distress mitigating resources. Therefore, understanding the patients most likely to experience financial distress will help personalize supportive therapy.

This study’s results as well as the existing literature describing financial distress support the use of comprehensive screening instruments to capture elements of financial burden beyond out-of-pocket costs.8,25 This screening is particularly relevant because we are increasingly recognizing that gross annual household income does not always reflect financial hardship or distress. The instrument we used for this analysis, the Psychological Sense of Economic Hardship, provides a broad view of financial toxicity including the specific components of financial strain, the inability to make ends meet, not having enough money for necessities, and economic adjustments experienced by patients with advanced cancer.20 Another measure to evaluate financial toxicity among patients with cancer includes the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST), which is a widely used patient-reported outcome measure. It was developed with input from both patients and oncology experts.25 Use of a financial toxicity assessment tool adds to our understanding of the economic financial burden experienced by patients with cancer, specifically those with advanced cancer.

Tucker-Seeley and Yabroff have identified several areas in which the research agenda for financial toxicity should focus, including: documentation of the socioeconomic context among patients across all areas of the cancer care continuum, further identification and characterization of at risk populations to address health disparities, and the inclusion of cost discussions in the health care context.26 Furthermore, research is needed to identify key areas to target for interventions addressing financial toxicity, such as addressing lack of financial resources to cover the cost of cancer care, focusing on managing or preventing the distress that results from a lack of financial resources, or addressing coping behaviors used by families to manage the financial burden of cancer care.26 Although cost discussions between health care providers and patients have been identified as important in reducing the financial burden of cancer care, the content, timing, and goals of those discussions still need to be better articulated for different patient populations, including patients with advanced cancer.3,27-28 In addition, resources such as social workers, patient navigators, or financial counselors have been identified as effective in assisting patients with financial planning and accessing community resources to address financial burden and assistance.4

Design considerations

This study has limitations that need to be noted. Its cross-sectional design does not allow for the analysis of causal inferences. In addition, certain groups were underrepresented in this study’s sample, including uninsured patients, men, and some minority groups, which may have underestimated the amount of financial burden experienced by patients with advanced cancer. The lack of representativeness of uninsured individuals may be a result of the eligibility of persons with advanced cancer for Medicaid. However, a strength of this study is its ability to increase the representativeness of African American/black patients in the study of advanced cancer and financial hardship. In our study, just over a quarter of the participants (26 of 100; 26%) were black/African American, compared with the US Census Bureau’s national census level of 13.3% and 13.4% in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania .29

The lack of employed participants in this study could be because many were not able to work because of the advanced stage of their disease. The low level of partnered status is a limitation, although one study site was a low-income hospital where one generally tends to see higher levels of unpartnered status. This study did not control for demographic information such as gender or age, thus, the relationships between the primary outcome variables and financial hardship may be overestimated. Moreover, this analysis of financial distress is limited to the context of the United States due to our lack of universal health care and unique payment system. Although we included only patients who were in the palliative phase of cancer treatment, no medical record review was conducted to determine previous cancer history and treatments, which might have provided more insight into other financial loss or cost of cancer treatment. Furthermore, we note that it can be difficult to prognosticate with accuracy and identify that some patients with advanced cancer may have been excluded from the study due to the inclusion criteria of less than 1 year of survival.

Conclusion

Perceived financial hardship is an important assessment of the burden placed on patients due to the cost of disease; and is a good start in assessing indirect costs that patients take on when coping with advanced stages of cancer and can shed light on an aspect of distress experienced by this patient population that is not commonly addressed. Subjective measures of perceived financial hardship complement objective measures that are commonly indicative of economic resources and can further our understanding of the impact of financial distress experienced by patients with cancer. Further study of financial impacts of advanced cancer as well as predictors of financial distress are essential to the early identification of financial hardship and the development of interventions to support those at high risk or experiencing financial distress.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients and staff at the UPMC Mercy Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who made this study possible, and Peggy Tate for her role in data collection. They also recognize the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Future Nursing Scholars program. They would also like to acknowledge that permission was granted for the use of the Psychological Sense of Economic Hardship study instrument.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. 2015. Accessed January 16, 2016.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology distress management version 1.2014. http://williams.medicine.wisc.edu/distress.pdf. Updated May 2014. Accessed January 16, 2016.

3. de Souza JA, Wong Y-N. Financial distress in cancer patients. J Med Person. 2014;11(2):13-15.

4. Mcdougall JA, Ramsey SD, Hutchinson F, Shih Y-CT. Financial toxicity: a growing concern among cancer patients in the United States. ISPOR Connect. 2014;20(2):10-11.

5. Sharpe K, Shaw B, Seiler MB. Practical solutions when facing cost sharing: the American Cancer Society’s health insurance assistance service. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(4):92-94.

6. Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer : a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608-1614.

7. Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, Mcnees P, Pisu M. Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):437-443.

8. Catt S, Starkings R, Shilling V, Fallowfield L. Patient-reported outcome measures of the impact of cancer on patients’ everyday lives: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(2):211-232.

9. Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Oncologist. 2015;20:1092-1098.

10. Kale HP, Carroll N V. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122:1283-1289.

11. Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732-1740.

12. Fenn KM, Evans SB, Mccorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Onocol Pract. 2014;10(5):332-339.

13. Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT. The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: a systematic review. Support Cancer Care. 2015;23:889-898.

14. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients a multicenter evaluation of the distress thermometer. Cancer. 2005;103:1494-1502.

15. Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the distress thermometer with bone marrow. Psychooncology. 2006;15:604-612.

16. Vodermaier A, Linden W, Siu C. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: a systematic review of assessment instruments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1464-1488.

17. McCorkle R, Quint-Benoliel J. Symptom distress, current concerns and mood disturbance after diagnosis of life-threatening disease. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(7):431–8.

18. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570-579.

19. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58.

20. Barrera M, Caples H, Tein J. The psychological sense of economic hardship: measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. Am J Community Psychol. 2001;29:493-517.

21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

22. Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):145-152.

23. Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710-3717.

24. Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor Jr. DH, et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:414-420.

25. De Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:3245-3253.

26. Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care : advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):1-3.

27. Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):162-168.

28. Irwin B, Kimmick G, Altomare I, et al. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. Oncologist. 2014;19:1135-1140.

29. US Census Bureau. United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/. 2015.

The American Cancer Society has identified a disparity in cancer death rates, noting that persons with lower socioeconomic status have higher rates of mortality.1 This is attributed to many factors, but it is largely owing to the higher burden of disease among lower-income individuals.1 A component of this disease burden is measured by assessing the patient-reported outcome of cancer-related distress. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Management Guidelines have defined distress as “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope with cancer, its physical symptoms and its treatment.”2