User login

Over 20 Years, Pain Is on the Rise

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

Criteria-based fibromyalgia diagnosis and rheumatologists’ clinical diagnosis often disagree

particularly the most recent revision of criteria from 2011 that rely on patients’ self-report of symptoms.

Frederick Wolfe, MD, of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases and the University of Kansas, Wichita, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research that clinicians failed to identify almost half of cases that met the 2011 modification of the American College of Rheumatology’s self-report criteria for fibromyalgia during a 3-month period at Rush Medical College, Chicago. This led them to conclude that the “overall agreement between clinicians’ diagnosis of fibromyalgia and diagnosis by fibromyalgia criteria is only fair.”

The findings call into question studies of fibromyalgia based on ICD-10 diagnosis, according to the authors.

Several widely accepted criteria sets have provided definitions and methods of diagnosis, but a number of studies have suggested that fibromyalgia is overdiagnosed, the authors wrote.

“In the current study, we consider underdiagnosis as well as the form of overdiagnosis that lead to diagnosis when fibromyalgia criteria are not satisfied and symptoms are insufficient for diagnosis,” they added.

The research included 497 consecutive patients attending the Rush Medical College rheumatology clinic who completed a questionnaire assessing fibromyalgia diagnostic variables used in the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and its 2011 modification for self-report immediately prior to being seen at the clinic. Clinicians were not given instructions on how any diseases were to be diagnosed, including no instructions on using 2011 fibromyalgia criteria.

The results showed that 121 (24.3%) of the patients satisfied the 2011 fibromyalgia criteria. The agreement between clinicians and criteria was 79.2%, but agreement beyond chance was considered “fair” based on a kappa score of 0.41 and a probabilistic benchmark interval of 0.21-0.40. The researchers wrote that this benchmark represents “the probability for each coefficient of falling into the selected benchmark interval along with the cumulative probability of exceeding the predetermined threshold associated with the interval.”

A total of 104 (20.9%) received a clinician ICD-10 diagnosis of fibromyalgia, but only 61 (58.7%) actually satisfied criteria. Physicians failed to identify 60 (49.6%) criteria-positive patients and incorrectly identified 43 (11.4%) criteria-negative patients.

In a subset of 88 patients with RA, agreement was 84.1%, and the kappa score was 0.32, indicating “slight to fair” agreement (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.00-0.20). Among 13 RA patients with criteria-positive fibromyalgia, 5 were identified by clinicians; among those who were criteria negative, 6 were deemed positive by clinicians.

The authors noted than “even worse” results were obtained in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, where the agreement between criteria and clinician ICD diagnosis yielded a kappa value of 0.08. In patients with osteoarthritis, the kappa score was 0.51 (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.21-0.40).

Overall, the results showed that women and patients with more symptoms but fewer pain areas were more likely to receive a clinician’s diagnosis than to satisfy fibromyalgia criteria. “Clinicians gave greater weight in making a diagnosis to being a woman and having increased symptoms and were willing to diagnose patients with lower WPI [Widespread Pain Index] and PSD [polysymptomatic distress] scores,” the researchers noted.

Dr. Wolfe and his associates wrote that it is unclear why the physicians in the study who misclassified fibromyalgia and missed patients with the diagnosis did not do better. “They may have simply misdiagnosed the condition or not accepted the use of the formal diagnostic system as necessary or clinically useful for identifying fibromyalgia in routine care.”

The researchers noted that it is likely that diagnosis in the community by general physicians, for whom the criteria are not as well known, is even more inaccurate. “It is likely that misdiagnosis is a public health problem and one that can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment as well as to inappropriate treatment of individuals not recognized to have fibromyalgia symptoms.”

No disclosures or funding were reported.

SOURCE: Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23731.

Despite voicing concern regarding the “self-report nature of fibromyalgia,” Wolfe et al. selected the 2011 self-report fibromyalgia criteria as their “gold standard” for fibromyalgia diagnosis. Their findings therefore should not be surprising.

The authors’ conclusion that expert physicians often misdiagnose fibromyalgia implies that published criteria are superior to expert clinical judgment for individual patient diagnosis.

However, this view fails to take into account the myriad variables seen by the clinician in the clinic. Until biomarkers or genetic testing allows for more objective disease markers, common conditions like fibromyalgia will continue to be symptom-based diagnoses. Therefore, the gold standard diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and other common illnesses is expert opinion.

Rheumatologists are the go-to experts for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, whether or not we readily accept that role.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial by Don Goldenberg, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and Tufts University, Boston (Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23727).

Despite voicing concern regarding the “self-report nature of fibromyalgia,” Wolfe et al. selected the 2011 self-report fibromyalgia criteria as their “gold standard” for fibromyalgia diagnosis. Their findings therefore should not be surprising.

The authors’ conclusion that expert physicians often misdiagnose fibromyalgia implies that published criteria are superior to expert clinical judgment for individual patient diagnosis.

However, this view fails to take into account the myriad variables seen by the clinician in the clinic. Until biomarkers or genetic testing allows for more objective disease markers, common conditions like fibromyalgia will continue to be symptom-based diagnoses. Therefore, the gold standard diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and other common illnesses is expert opinion.

Rheumatologists are the go-to experts for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, whether or not we readily accept that role.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial by Don Goldenberg, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and Tufts University, Boston (Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23727).

Despite voicing concern regarding the “self-report nature of fibromyalgia,” Wolfe et al. selected the 2011 self-report fibromyalgia criteria as their “gold standard” for fibromyalgia diagnosis. Their findings therefore should not be surprising.

The authors’ conclusion that expert physicians often misdiagnose fibromyalgia implies that published criteria are superior to expert clinical judgment for individual patient diagnosis.

However, this view fails to take into account the myriad variables seen by the clinician in the clinic. Until biomarkers or genetic testing allows for more objective disease markers, common conditions like fibromyalgia will continue to be symptom-based diagnoses. Therefore, the gold standard diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and other common illnesses is expert opinion.

Rheumatologists are the go-to experts for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, whether or not we readily accept that role.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial by Don Goldenberg, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and Tufts University, Boston (Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23727).

particularly the most recent revision of criteria from 2011 that rely on patients’ self-report of symptoms.

Frederick Wolfe, MD, of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases and the University of Kansas, Wichita, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research that clinicians failed to identify almost half of cases that met the 2011 modification of the American College of Rheumatology’s self-report criteria for fibromyalgia during a 3-month period at Rush Medical College, Chicago. This led them to conclude that the “overall agreement between clinicians’ diagnosis of fibromyalgia and diagnosis by fibromyalgia criteria is only fair.”

The findings call into question studies of fibromyalgia based on ICD-10 diagnosis, according to the authors.

Several widely accepted criteria sets have provided definitions and methods of diagnosis, but a number of studies have suggested that fibromyalgia is overdiagnosed, the authors wrote.

“In the current study, we consider underdiagnosis as well as the form of overdiagnosis that lead to diagnosis when fibromyalgia criteria are not satisfied and symptoms are insufficient for diagnosis,” they added.

The research included 497 consecutive patients attending the Rush Medical College rheumatology clinic who completed a questionnaire assessing fibromyalgia diagnostic variables used in the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and its 2011 modification for self-report immediately prior to being seen at the clinic. Clinicians were not given instructions on how any diseases were to be diagnosed, including no instructions on using 2011 fibromyalgia criteria.

The results showed that 121 (24.3%) of the patients satisfied the 2011 fibromyalgia criteria. The agreement between clinicians and criteria was 79.2%, but agreement beyond chance was considered “fair” based on a kappa score of 0.41 and a probabilistic benchmark interval of 0.21-0.40. The researchers wrote that this benchmark represents “the probability for each coefficient of falling into the selected benchmark interval along with the cumulative probability of exceeding the predetermined threshold associated with the interval.”

A total of 104 (20.9%) received a clinician ICD-10 diagnosis of fibromyalgia, but only 61 (58.7%) actually satisfied criteria. Physicians failed to identify 60 (49.6%) criteria-positive patients and incorrectly identified 43 (11.4%) criteria-negative patients.

In a subset of 88 patients with RA, agreement was 84.1%, and the kappa score was 0.32, indicating “slight to fair” agreement (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.00-0.20). Among 13 RA patients with criteria-positive fibromyalgia, 5 were identified by clinicians; among those who were criteria negative, 6 were deemed positive by clinicians.

The authors noted than “even worse” results were obtained in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, where the agreement between criteria and clinician ICD diagnosis yielded a kappa value of 0.08. In patients with osteoarthritis, the kappa score was 0.51 (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.21-0.40).

Overall, the results showed that women and patients with more symptoms but fewer pain areas were more likely to receive a clinician’s diagnosis than to satisfy fibromyalgia criteria. “Clinicians gave greater weight in making a diagnosis to being a woman and having increased symptoms and were willing to diagnose patients with lower WPI [Widespread Pain Index] and PSD [polysymptomatic distress] scores,” the researchers noted.

Dr. Wolfe and his associates wrote that it is unclear why the physicians in the study who misclassified fibromyalgia and missed patients with the diagnosis did not do better. “They may have simply misdiagnosed the condition or not accepted the use of the formal diagnostic system as necessary or clinically useful for identifying fibromyalgia in routine care.”

The researchers noted that it is likely that diagnosis in the community by general physicians, for whom the criteria are not as well known, is even more inaccurate. “It is likely that misdiagnosis is a public health problem and one that can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment as well as to inappropriate treatment of individuals not recognized to have fibromyalgia symptoms.”

No disclosures or funding were reported.

SOURCE: Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23731.

particularly the most recent revision of criteria from 2011 that rely on patients’ self-report of symptoms.

Frederick Wolfe, MD, of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases and the University of Kansas, Wichita, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research that clinicians failed to identify almost half of cases that met the 2011 modification of the American College of Rheumatology’s self-report criteria for fibromyalgia during a 3-month period at Rush Medical College, Chicago. This led them to conclude that the “overall agreement between clinicians’ diagnosis of fibromyalgia and diagnosis by fibromyalgia criteria is only fair.”

The findings call into question studies of fibromyalgia based on ICD-10 diagnosis, according to the authors.

Several widely accepted criteria sets have provided definitions and methods of diagnosis, but a number of studies have suggested that fibromyalgia is overdiagnosed, the authors wrote.

“In the current study, we consider underdiagnosis as well as the form of overdiagnosis that lead to diagnosis when fibromyalgia criteria are not satisfied and symptoms are insufficient for diagnosis,” they added.

The research included 497 consecutive patients attending the Rush Medical College rheumatology clinic who completed a questionnaire assessing fibromyalgia diagnostic variables used in the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and its 2011 modification for self-report immediately prior to being seen at the clinic. Clinicians were not given instructions on how any diseases were to be diagnosed, including no instructions on using 2011 fibromyalgia criteria.

The results showed that 121 (24.3%) of the patients satisfied the 2011 fibromyalgia criteria. The agreement between clinicians and criteria was 79.2%, but agreement beyond chance was considered “fair” based on a kappa score of 0.41 and a probabilistic benchmark interval of 0.21-0.40. The researchers wrote that this benchmark represents “the probability for each coefficient of falling into the selected benchmark interval along with the cumulative probability of exceeding the predetermined threshold associated with the interval.”

A total of 104 (20.9%) received a clinician ICD-10 diagnosis of fibromyalgia, but only 61 (58.7%) actually satisfied criteria. Physicians failed to identify 60 (49.6%) criteria-positive patients and incorrectly identified 43 (11.4%) criteria-negative patients.

In a subset of 88 patients with RA, agreement was 84.1%, and the kappa score was 0.32, indicating “slight to fair” agreement (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.00-0.20). Among 13 RA patients with criteria-positive fibromyalgia, 5 were identified by clinicians; among those who were criteria negative, 6 were deemed positive by clinicians.

The authors noted than “even worse” results were obtained in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, where the agreement between criteria and clinician ICD diagnosis yielded a kappa value of 0.08. In patients with osteoarthritis, the kappa score was 0.51 (probabilistic benchmark interval, 0.21-0.40).

Overall, the results showed that women and patients with more symptoms but fewer pain areas were more likely to receive a clinician’s diagnosis than to satisfy fibromyalgia criteria. “Clinicians gave greater weight in making a diagnosis to being a woman and having increased symptoms and were willing to diagnose patients with lower WPI [Widespread Pain Index] and PSD [polysymptomatic distress] scores,” the researchers noted.

Dr. Wolfe and his associates wrote that it is unclear why the physicians in the study who misclassified fibromyalgia and missed patients with the diagnosis did not do better. “They may have simply misdiagnosed the condition or not accepted the use of the formal diagnostic system as necessary or clinically useful for identifying fibromyalgia in routine care.”

The researchers noted that it is likely that diagnosis in the community by general physicians, for whom the criteria are not as well known, is even more inaccurate. “It is likely that misdiagnosis is a public health problem and one that can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment as well as to inappropriate treatment of individuals not recognized to have fibromyalgia symptoms.”

No disclosures or funding were reported.

SOURCE: Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23731.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Clinicians failed to identify nearly 50% of criteria-positive cases

Major finding: Physicians failed to identify 60 (49.6%) criteria-positive patients and incorrectly identified 43 (11.4%) criteria-negative patients.

Study details: A group of 497 consecutive unselected rheumatology clinic attendees who completed a questionnaire assessing fibromyalgia diagnostic variables used in the American College of Rheumatology 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and its 2011 modification for self-report.

Disclosures: No disclosures or funding were reported.

Source: Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.23731.

International survey probes oxygen’s efficacy for cluster headache

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

FROM HEADACHE

Key clinical point: Oxygen is a highly effective treatment for cluster headache with few complications.

Major finding: More than half of respondents (54%) reported that triptans and oxygen were completely or very effective.

Study details: Analysis of data from 1,604 people with cluster headache who completed the online Cluster Headache Questionnaire.

Disclosures: The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

Source: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

In California, opioids most often prescribed in low-income, mostly white areas

There is a higher prevalence of opioid prescribing and opioid-related overdose deaths concentrated in regions with mostly low-income, white residents, compared with regions with high income and the lowest proportion of white residents, according to a new analysis of data on people living in California.

The findings of this study provide further evidence that the opioid epidemic affects a large proportion of low-income white communities (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721).

“Whereas most epidemics predominate within social minority groups and previous US drug epidemics have typically been concentrated in nonwhite communities, Joseph Friedman, MPH, from the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in their study. “Our analysis suggests that, at least in California, an important determinant of this phenomenon may be that white individuals have a higher level of exposure than nonwhite individuals to opioid prescriptions on a per capita basis through the health care system.”

Mr. Friedman and his colleagues analyzed 29.7 million prescription drug records from California’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System in and examined the prevalence of opioids, benzodiazepines, and stimulants by race, ethnicity, and income level in 1,760 zip codes during 2011-2015. The researchers estimated the prevalence of opioid prescriptions in each zip code by calculating the number of people per zip code receiving an opioid prescription divided by the population of the zip code during each year.

Overall, 23.6% of California residents received at least one opioid prescription each year of the study. The researchers found 44.2% of individuals in zip codes with the lowest income but highest proportion of white residents and 16.1% of individuals in areas with the highest income and lowest proportion of white residents had received a minimum of one opioid prescription each year. The prevalence of stimulant prescriptions was 3.8% in zip codes with high income, and a high proportion of white population, compared with a prevalence of 0.6% in areas with low income and a low proportion of white residents. The researchers noted there was no association between income and benzodiazepine prescription, but the prevalence of benzodiazepine prescriptions was 15.7% in zip codes with the highest proportion of white residents, compared with 7.0% in zip codes with a low proportion of white residents.

During the same time period, there were 9,534 opioid overdose deaths in California from causes such as fentanyl, synthetic opioids, and prescription opioids. “Overdose deaths were highly concentrated in lower-income and mostly white areas,” Mr. Friedman and his colleagues wrote. “We observed an approximate 10-fold difference in overdose rates across the race/ethnicity–income gradient in California.”

Although the number of opioids prescribed each year has decreased since 2012, in a research letter published in the same issue noted that the rate of prescribing is still higher than it was in 1999 (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6989). The authors also pointed out increases in the duration of opioid prescriptions and wide regional variations in opioid prescribing rates.

In their study, Gery P. Guy Jr., PhD, and his colleagues used data from the IQVIA Xponent database from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies and discovered the average morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per capita had decreased from 641.4 MME per capita in 2015 to 512.6 MME per capita in 2017 (20.1%). The number of opioid prescriptions also decreased from 6.7 per 100 persons in 2015 to 5.0 per 100 persons in 2017 (25.3%). However, during 2015-2017, the average duration of opioid prescriptions increased from 17.7 days to 18.3 days (3.4%), while the median duration increased during the same time from 15.0 days to 20.0 days (33.3%).

While 74.7% of counties reduced the number of opioids prescribed during 2015-2017 and there also were reductions in the rate of high-dose prescribing (76.6%) and overall prescribing rates (74.7%), Dr. Guy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues found “substantial variation” in 2017 prescription rates at the county level, with opioids prescribed at 1,061.0 MME per capita at the highest quartile, compared with 182.8 MME per capita at the lowest quartile.

“Recent reductions could be related to policies and strategies aimed at reducing inappropriate prescribing, increased awareness of the risks associated with opioids, and release of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain–United States, 2016,” Dr. Guy and his colleagues noted.

In an additional article published in the same JAMA Internal Medicine issue, Bennett Allen, a research associate at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and his colleagues examined the rate of opioid overdose deaths for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and undefined other races in New York (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7700). They identified 1,487 deaths in 2017, which included 556 white (37.0%), 421 black (28.0%), 455 Hispanic (31.0%), and 55 undefined (4.0%) opioid overdose deaths. There was a higher rate of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose deaths from younger (aged 15-34 years) white New Yorkers (22.2/100,000 persons; 95% confidence interval, 19.0-25.5), compared with younger black New Yorkers (5.8/100,000; 95% CI, 4.0-8.2) and Hispanic (9.7/100,000; 95% CI, 7.6-12.1).

Among older residents (aged 55-84 years), Mr. Allen and his colleagues found higher rates of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose for black New Yorkers (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with older white New Yorkers (9.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 7.3-11.8), as well as significantly higher rates of cocaine overdose (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with white (5.1/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 3.6-7.0) and Hispanic residents (11.8/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 8.9-15.4).

“The distinct age distribution and drug involvement of overdose deaths among New York City blacks, Latinos, and whites, along with complementary evidence about drug use trajectories, highlight the need for heterogeneous approaches to treatment and the equitable allocation of treatment and health care resources to reach diverse populations at risk of overdose,” Mr. Allen and his colleagues wrote.

Dr. Schriger reported support from Korein Foundation for his time working on the study by Friedman et al. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The results published by Friedman et al. are a reminder that we can use regional prescribing trends to identify communities most susceptible to the opioid epidemic and give them the resources they need to combat opioid addiction, Vice Adm. Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, and Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Discussion of overdose risks and coprescribing of naloxone must become routine if we are to make opioid prescribing safer,” the authors wrote.

Physicians also can help respond to the opioid epidemic outside of prescribing by promoting evidence-based nonopioid and nonpharmaceutical pain treatments, screening their patients for OUD and OUD risks, and acknowledging “that the problem cannot be solved by medical interventions alone.” Individual, environmental, and societal factors also contribute to the opioid epidemic, and physicians are uniquely suited to spearhead efforts aimed at addressing comprehensive opioid misuse.

“Physicians stand out as natural leaders to help solve the crises because of the depth of their knowledge, immediacy of their contact with patients, and relatively high level of respect their profession enjoys,” Dr. Adams and Dr. Giroir wrote. “We thereby call on our nation’s doctors to embrace their roles in the clinic and beyond to help educate communities, bring together stakeholders, and be part of the cultural change to support people living free from addiction.”

Dr. Adams is the 20th surgeon general of the United States at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS; Dr. Giroir is the 16th U.S. assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Their invited commentary accompanied the three related articles in the publication (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7934 ).

The results published by Friedman et al. are a reminder that we can use regional prescribing trends to identify communities most susceptible to the opioid epidemic and give them the resources they need to combat opioid addiction, Vice Adm. Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, and Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Discussion of overdose risks and coprescribing of naloxone must become routine if we are to make opioid prescribing safer,” the authors wrote.

Physicians also can help respond to the opioid epidemic outside of prescribing by promoting evidence-based nonopioid and nonpharmaceutical pain treatments, screening their patients for OUD and OUD risks, and acknowledging “that the problem cannot be solved by medical interventions alone.” Individual, environmental, and societal factors also contribute to the opioid epidemic, and physicians are uniquely suited to spearhead efforts aimed at addressing comprehensive opioid misuse.

“Physicians stand out as natural leaders to help solve the crises because of the depth of their knowledge, immediacy of their contact with patients, and relatively high level of respect their profession enjoys,” Dr. Adams and Dr. Giroir wrote. “We thereby call on our nation’s doctors to embrace their roles in the clinic and beyond to help educate communities, bring together stakeholders, and be part of the cultural change to support people living free from addiction.”

Dr. Adams is the 20th surgeon general of the United States at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS; Dr. Giroir is the 16th U.S. assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Their invited commentary accompanied the three related articles in the publication (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7934 ).

The results published by Friedman et al. are a reminder that we can use regional prescribing trends to identify communities most susceptible to the opioid epidemic and give them the resources they need to combat opioid addiction, Vice Adm. Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, and Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Discussion of overdose risks and coprescribing of naloxone must become routine if we are to make opioid prescribing safer,” the authors wrote.

Physicians also can help respond to the opioid epidemic outside of prescribing by promoting evidence-based nonopioid and nonpharmaceutical pain treatments, screening their patients for OUD and OUD risks, and acknowledging “that the problem cannot be solved by medical interventions alone.” Individual, environmental, and societal factors also contribute to the opioid epidemic, and physicians are uniquely suited to spearhead efforts aimed at addressing comprehensive opioid misuse.

“Physicians stand out as natural leaders to help solve the crises because of the depth of their knowledge, immediacy of their contact with patients, and relatively high level of respect their profession enjoys,” Dr. Adams and Dr. Giroir wrote. “We thereby call on our nation’s doctors to embrace their roles in the clinic and beyond to help educate communities, bring together stakeholders, and be part of the cultural change to support people living free from addiction.”

Dr. Adams is the 20th surgeon general of the United States at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS; Dr. Giroir is the 16th U.S. assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Public Health Service and HHS. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Their invited commentary accompanied the three related articles in the publication (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7934 ).

There is a higher prevalence of opioid prescribing and opioid-related overdose deaths concentrated in regions with mostly low-income, white residents, compared with regions with high income and the lowest proportion of white residents, according to a new analysis of data on people living in California.

The findings of this study provide further evidence that the opioid epidemic affects a large proportion of low-income white communities (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721).

“Whereas most epidemics predominate within social minority groups and previous US drug epidemics have typically been concentrated in nonwhite communities, Joseph Friedman, MPH, from the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in their study. “Our analysis suggests that, at least in California, an important determinant of this phenomenon may be that white individuals have a higher level of exposure than nonwhite individuals to opioid prescriptions on a per capita basis through the health care system.”

Mr. Friedman and his colleagues analyzed 29.7 million prescription drug records from California’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System in and examined the prevalence of opioids, benzodiazepines, and stimulants by race, ethnicity, and income level in 1,760 zip codes during 2011-2015. The researchers estimated the prevalence of opioid prescriptions in each zip code by calculating the number of people per zip code receiving an opioid prescription divided by the population of the zip code during each year.

Overall, 23.6% of California residents received at least one opioid prescription each year of the study. The researchers found 44.2% of individuals in zip codes with the lowest income but highest proportion of white residents and 16.1% of individuals in areas with the highest income and lowest proportion of white residents had received a minimum of one opioid prescription each year. The prevalence of stimulant prescriptions was 3.8% in zip codes with high income, and a high proportion of white population, compared with a prevalence of 0.6% in areas with low income and a low proportion of white residents. The researchers noted there was no association between income and benzodiazepine prescription, but the prevalence of benzodiazepine prescriptions was 15.7% in zip codes with the highest proportion of white residents, compared with 7.0% in zip codes with a low proportion of white residents.

During the same time period, there were 9,534 opioid overdose deaths in California from causes such as fentanyl, synthetic opioids, and prescription opioids. “Overdose deaths were highly concentrated in lower-income and mostly white areas,” Mr. Friedman and his colleagues wrote. “We observed an approximate 10-fold difference in overdose rates across the race/ethnicity–income gradient in California.”

Although the number of opioids prescribed each year has decreased since 2012, in a research letter published in the same issue noted that the rate of prescribing is still higher than it was in 1999 (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6989). The authors also pointed out increases in the duration of opioid prescriptions and wide regional variations in opioid prescribing rates.

In their study, Gery P. Guy Jr., PhD, and his colleagues used data from the IQVIA Xponent database from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies and discovered the average morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per capita had decreased from 641.4 MME per capita in 2015 to 512.6 MME per capita in 2017 (20.1%). The number of opioid prescriptions also decreased from 6.7 per 100 persons in 2015 to 5.0 per 100 persons in 2017 (25.3%). However, during 2015-2017, the average duration of opioid prescriptions increased from 17.7 days to 18.3 days (3.4%), while the median duration increased during the same time from 15.0 days to 20.0 days (33.3%).

While 74.7% of counties reduced the number of opioids prescribed during 2015-2017 and there also were reductions in the rate of high-dose prescribing (76.6%) and overall prescribing rates (74.7%), Dr. Guy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues found “substantial variation” in 2017 prescription rates at the county level, with opioids prescribed at 1,061.0 MME per capita at the highest quartile, compared with 182.8 MME per capita at the lowest quartile.

“Recent reductions could be related to policies and strategies aimed at reducing inappropriate prescribing, increased awareness of the risks associated with opioids, and release of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain–United States, 2016,” Dr. Guy and his colleagues noted.

In an additional article published in the same JAMA Internal Medicine issue, Bennett Allen, a research associate at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and his colleagues examined the rate of opioid overdose deaths for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and undefined other races in New York (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7700). They identified 1,487 deaths in 2017, which included 556 white (37.0%), 421 black (28.0%), 455 Hispanic (31.0%), and 55 undefined (4.0%) opioid overdose deaths. There was a higher rate of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose deaths from younger (aged 15-34 years) white New Yorkers (22.2/100,000 persons; 95% confidence interval, 19.0-25.5), compared with younger black New Yorkers (5.8/100,000; 95% CI, 4.0-8.2) and Hispanic (9.7/100,000; 95% CI, 7.6-12.1).

Among older residents (aged 55-84 years), Mr. Allen and his colleagues found higher rates of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose for black New Yorkers (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with older white New Yorkers (9.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 7.3-11.8), as well as significantly higher rates of cocaine overdose (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with white (5.1/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 3.6-7.0) and Hispanic residents (11.8/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 8.9-15.4).

“The distinct age distribution and drug involvement of overdose deaths among New York City blacks, Latinos, and whites, along with complementary evidence about drug use trajectories, highlight the need for heterogeneous approaches to treatment and the equitable allocation of treatment and health care resources to reach diverse populations at risk of overdose,” Mr. Allen and his colleagues wrote.

Dr. Schriger reported support from Korein Foundation for his time working on the study by Friedman et al. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

There is a higher prevalence of opioid prescribing and opioid-related overdose deaths concentrated in regions with mostly low-income, white residents, compared with regions with high income and the lowest proportion of white residents, according to a new analysis of data on people living in California.

The findings of this study provide further evidence that the opioid epidemic affects a large proportion of low-income white communities (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721).

“Whereas most epidemics predominate within social minority groups and previous US drug epidemics have typically been concentrated in nonwhite communities, Joseph Friedman, MPH, from the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in their study. “Our analysis suggests that, at least in California, an important determinant of this phenomenon may be that white individuals have a higher level of exposure than nonwhite individuals to opioid prescriptions on a per capita basis through the health care system.”

Mr. Friedman and his colleagues analyzed 29.7 million prescription drug records from California’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System in and examined the prevalence of opioids, benzodiazepines, and stimulants by race, ethnicity, and income level in 1,760 zip codes during 2011-2015. The researchers estimated the prevalence of opioid prescriptions in each zip code by calculating the number of people per zip code receiving an opioid prescription divided by the population of the zip code during each year.

Overall, 23.6% of California residents received at least one opioid prescription each year of the study. The researchers found 44.2% of individuals in zip codes with the lowest income but highest proportion of white residents and 16.1% of individuals in areas with the highest income and lowest proportion of white residents had received a minimum of one opioid prescription each year. The prevalence of stimulant prescriptions was 3.8% in zip codes with high income, and a high proportion of white population, compared with a prevalence of 0.6% in areas with low income and a low proportion of white residents. The researchers noted there was no association between income and benzodiazepine prescription, but the prevalence of benzodiazepine prescriptions was 15.7% in zip codes with the highest proportion of white residents, compared with 7.0% in zip codes with a low proportion of white residents.

During the same time period, there were 9,534 opioid overdose deaths in California from causes such as fentanyl, synthetic opioids, and prescription opioids. “Overdose deaths were highly concentrated in lower-income and mostly white areas,” Mr. Friedman and his colleagues wrote. “We observed an approximate 10-fold difference in overdose rates across the race/ethnicity–income gradient in California.”

Although the number of opioids prescribed each year has decreased since 2012, in a research letter published in the same issue noted that the rate of prescribing is still higher than it was in 1999 (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6989). The authors also pointed out increases in the duration of opioid prescriptions and wide regional variations in opioid prescribing rates.

In their study, Gery P. Guy Jr., PhD, and his colleagues used data from the IQVIA Xponent database from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies and discovered the average morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per capita had decreased from 641.4 MME per capita in 2015 to 512.6 MME per capita in 2017 (20.1%). The number of opioid prescriptions also decreased from 6.7 per 100 persons in 2015 to 5.0 per 100 persons in 2017 (25.3%). However, during 2015-2017, the average duration of opioid prescriptions increased from 17.7 days to 18.3 days (3.4%), while the median duration increased during the same time from 15.0 days to 20.0 days (33.3%).

While 74.7% of counties reduced the number of opioids prescribed during 2015-2017 and there also were reductions in the rate of high-dose prescribing (76.6%) and overall prescribing rates (74.7%), Dr. Guy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues found “substantial variation” in 2017 prescription rates at the county level, with opioids prescribed at 1,061.0 MME per capita at the highest quartile, compared with 182.8 MME per capita at the lowest quartile.

“Recent reductions could be related to policies and strategies aimed at reducing inappropriate prescribing, increased awareness of the risks associated with opioids, and release of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain–United States, 2016,” Dr. Guy and his colleagues noted.

In an additional article published in the same JAMA Internal Medicine issue, Bennett Allen, a research associate at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and his colleagues examined the rate of opioid overdose deaths for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and undefined other races in New York (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7700). They identified 1,487 deaths in 2017, which included 556 white (37.0%), 421 black (28.0%), 455 Hispanic (31.0%), and 55 undefined (4.0%) opioid overdose deaths. There was a higher rate of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose deaths from younger (aged 15-34 years) white New Yorkers (22.2/100,000 persons; 95% confidence interval, 19.0-25.5), compared with younger black New Yorkers (5.8/100,000; 95% CI, 4.0-8.2) and Hispanic (9.7/100,000; 95% CI, 7.6-12.1).

Among older residents (aged 55-84 years), Mr. Allen and his colleagues found higher rates of fentanyl and/or heroin overdose for black New Yorkers (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with older white New Yorkers (9.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 7.3-11.8), as well as significantly higher rates of cocaine overdose (25.4/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 20.9-30.0), compared with white (5.1/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 3.6-7.0) and Hispanic residents (11.8/100,000 persons; 95% CI, 8.9-15.4).

“The distinct age distribution and drug involvement of overdose deaths among New York City blacks, Latinos, and whites, along with complementary evidence about drug use trajectories, highlight the need for heterogeneous approaches to treatment and the equitable allocation of treatment and health care resources to reach diverse populations at risk of overdose,” Mr. Allen and his colleagues wrote.

Dr. Schriger reported support from Korein Foundation for his time working on the study by Friedman et al. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The most common users of opioids according to prescription drug records are residents of mostly low-income, white neighborhoods.

Major finding: Compared with 23.6% of all Californians, 44.2% of individuals in zip codes containing mostly low-income, white residents had at least one opioid prescription each year, compared with 16.1% of individuals in high-income zip codes with the lowest population of white residents.

Study details: An analysis of 29.7 million opioid prescription drug records by race and income in California during 2011-2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Schriger reported support from the Korein Foundation for his time working on the study by Friedman et al. The other authors from Friedman et al. reported no conflicts of interest.

The Underrecognized Risk for Drug Overdose Deaths

The numbers are stunning: 1,643% increase in rates of deaths involving synthetic opioids. A 915% increase for heroin, 830% for benzodiazepines. Even more stunning: Those are the increases only in overdose death rates for women aged 30 to 64 years.

According to CDC data, between 1999 and 2010, the largest percentage change in the rates of overall drug overdose deaths was among women aged between 45 and 64 years. But that research did not account for trends in specific drugs or consider changes in age group distributions, say researchers from the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

They examined overdose death rates among women aged 30 to 64 years between 1999 and 2017. The unadjusted death rate jumped 260%, from 4,314 deaths to 18,110 deaths. Among women aged 55 to 59 years, the number of deaths involving antidepressants increased approximately 300%; among women aged 60 to 64 years, nearly 400%. The crude rate of deaths involving prescription opioids skyrocketed > 1,000%.

The drug epidemic is “evolving,” the researchers note. In 1999, overdose death rates were highest among women aged 40 to 44 years. In 2017, they were highest among women aged 50 to 54 years. And as demographics shift, prevention programs need to shift as well. As women age, the researchers say, individual experiences can change the type of substance used or misused and in the experiences of pain that might result in an opioid prescription.

The researchers note that “substantial work” has focused on informing women of childbearing age about the risks and benefits of certain drugs. The current analysis demonstrates “the remaining need” to consider middle-aged women who are at risk.

Targeted efforts are needed, and the researchers suggest interventions: Medicaid and other health insurance programs can review records of controlled substance prescribing. States and local communities can expand capacity of drug use disorder treatments and links to care, particularly adding “gender-responsive” substance use disorder treatment centers.

A “multifaceted approach involving the full spectrum of care services is likely necessary,” the researchers say. Health care practitioners who treat women for pain, depression, or anxiety can discuss treatment options that consider the unique biopsychosocial needs of women.

Health care practitioners also can consider implementing the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, which says “Opioids are not first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain.” The guideline also says before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients the “known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy.” In other words, listen to the women and prescribe carefully.

The numbers are stunning: 1,643% increase in rates of deaths involving synthetic opioids. A 915% increase for heroin, 830% for benzodiazepines. Even more stunning: Those are the increases only in overdose death rates for women aged 30 to 64 years.

According to CDC data, between 1999 and 2010, the largest percentage change in the rates of overall drug overdose deaths was among women aged between 45 and 64 years. But that research did not account for trends in specific drugs or consider changes in age group distributions, say researchers from the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

They examined overdose death rates among women aged 30 to 64 years between 1999 and 2017. The unadjusted death rate jumped 260%, from 4,314 deaths to 18,110 deaths. Among women aged 55 to 59 years, the number of deaths involving antidepressants increased approximately 300%; among women aged 60 to 64 years, nearly 400%. The crude rate of deaths involving prescription opioids skyrocketed > 1,000%.

The drug epidemic is “evolving,” the researchers note. In 1999, overdose death rates were highest among women aged 40 to 44 years. In 2017, they were highest among women aged 50 to 54 years. And as demographics shift, prevention programs need to shift as well. As women age, the researchers say, individual experiences can change the type of substance used or misused and in the experiences of pain that might result in an opioid prescription.

The researchers note that “substantial work” has focused on informing women of childbearing age about the risks and benefits of certain drugs. The current analysis demonstrates “the remaining need” to consider middle-aged women who are at risk.

Targeted efforts are needed, and the researchers suggest interventions: Medicaid and other health insurance programs can review records of controlled substance prescribing. States and local communities can expand capacity of drug use disorder treatments and links to care, particularly adding “gender-responsive” substance use disorder treatment centers.

A “multifaceted approach involving the full spectrum of care services is likely necessary,” the researchers say. Health care practitioners who treat women for pain, depression, or anxiety can discuss treatment options that consider the unique biopsychosocial needs of women.

Health care practitioners also can consider implementing the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, which says “Opioids are not first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain.” The guideline also says before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients the “known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy.” In other words, listen to the women and prescribe carefully.

The numbers are stunning: 1,643% increase in rates of deaths involving synthetic opioids. A 915% increase for heroin, 830% for benzodiazepines. Even more stunning: Those are the increases only in overdose death rates for women aged 30 to 64 years.

According to CDC data, between 1999 and 2010, the largest percentage change in the rates of overall drug overdose deaths was among women aged between 45 and 64 years. But that research did not account for trends in specific drugs or consider changes in age group distributions, say researchers from the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

They examined overdose death rates among women aged 30 to 64 years between 1999 and 2017. The unadjusted death rate jumped 260%, from 4,314 deaths to 18,110 deaths. Among women aged 55 to 59 years, the number of deaths involving antidepressants increased approximately 300%; among women aged 60 to 64 years, nearly 400%. The crude rate of deaths involving prescription opioids skyrocketed > 1,000%.

The drug epidemic is “evolving,” the researchers note. In 1999, overdose death rates were highest among women aged 40 to 44 years. In 2017, they were highest among women aged 50 to 54 years. And as demographics shift, prevention programs need to shift as well. As women age, the researchers say, individual experiences can change the type of substance used or misused and in the experiences of pain that might result in an opioid prescription.

The researchers note that “substantial work” has focused on informing women of childbearing age about the risks and benefits of certain drugs. The current analysis demonstrates “the remaining need” to consider middle-aged women who are at risk.

Targeted efforts are needed, and the researchers suggest interventions: Medicaid and other health insurance programs can review records of controlled substance prescribing. States and local communities can expand capacity of drug use disorder treatments and links to care, particularly adding “gender-responsive” substance use disorder treatment centers.

A “multifaceted approach involving the full spectrum of care services is likely necessary,” the researchers say. Health care practitioners who treat women for pain, depression, or anxiety can discuss treatment options that consider the unique biopsychosocial needs of women.

Health care practitioners also can consider implementing the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, which says “Opioids are not first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain.” The guideline also says before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients the “known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy.” In other words, listen to the women and prescribe carefully.

Cloud of inconsistency hangs over cannabis data

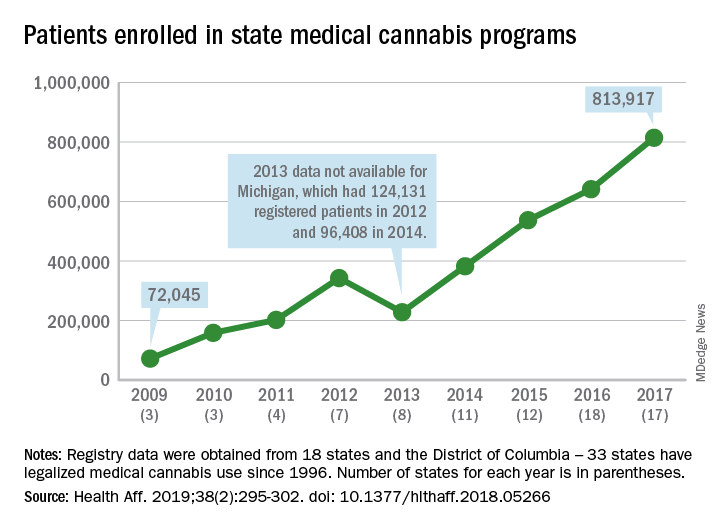

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Psoriatic arthritis eludes early diagnosis

Most patients with psoriatic arthritis first present with psoriasis only. Their skin disorder precedes any joint involvement, often by several years. That suggests targeting interventions to patients with psoriasis to prevent or slow their progression to psoriatic arthritis, as well as following psoriatic patients closely to diagnose psoriatic arthritis quickly when it first appears. It’s a simple and attractive management premise that’s been challenging to apply in practice.

It’s not that clinicians aren’t motivated to diagnose psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in patients early, hopefully as soon as it appears. The susceptibility of patients with psoriasis to develop PsA is well described, with an annual progression rate of about 3%, and adverse consequences result from even a 6-month delay in diagnosis.

“Some physicians still don’t ask psoriasis patients about joint pain, or their symptoms are misinterpreted as something else,” said Lihi Eder, MD, a rheumatologist at Women’s College Research Institute, Toronto, and the University of Toronto. “Although there is increased awareness about PsA, there are still delays in diagnosis,” she said in an interview.