User login

Addressing anxiety helps youth with functional abdominal pain disorders

MILWAUKEE – A stepped-care approach to youth with functional abdominal pain disorders may be effective in targeting those with comorbid anxiety, according to ongoing research.

A study of 79 pediatric patients with a functional abdominal pain disorder (FAPD) and co-occurring anxiety found that those who received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that included a component to address anxiety had less functional disability and anxiety than those who received treatment as usual. Pain scores also dropped, though the difference was not statistically significant.

The patients, aged 9-14 years and mostly white and female, were randomized to treatment allocation. Functional disability scores were significantly lower post-treatment for those who received the stepped therapy compared with the treatment as usual group (P less than .05, Cohen’s D = .49). This indicates a moderate effect size, said Natoshia Cunningham, PhD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Mean scores on an anxiety rating scale also dropped below the threshold for clinical anxiety for those receiving the stepped therapy; on average, the treatment as usual group still scored above the clinical anxiety threshold after treatment (P for difference = .05).

The study, part of ongoing research, tests a hybrid online intervention, dubbed Aim to Decrease Anxiety and Pain Treatment, or ADAPT. The ADAPT program includes some common elements of CBT for anxiety that were not previously included in the pediatric pain CBT in use for the FAPD patients, she said.

The hybrid program began with two in-person sessions, each lasting one hour. These were followed by up to four web-based sessions. Patients viewed videos, read some material online, and complete activities with follow-up assessments. The web-based component was structured so that providers can see how patients fare on assessments – and even see which activities had been opened or completed. This, said Dr. Cunningham, allowed the treating provider to tailor what’s addressed in the associated weekly phone checks that accompany the online content.

Parents were also given practical, evidence-based advice to help manage their child’s FAPD. These include encouraging children to be independent in pain management, stopping “status checks,” encouraging normal school and social activities, and avoiding special privileges when pain interferes with activities.

Overall, up to 40% of pediatric functional abdominal pain patients may not respond to CBT, the most efficacious treatment known, said Dr. Cunningham, a pediatric psychologist at the University of Cincinnati. Her research indicates that comorbid anxiety may predict poor response, and that addressing anxiety improves pain and disability in this complex, common disorder.

With a brief psychosocial screening that identifies patients with anxiety, Dr. Cunningham and her colleagues can implement the targeted, partially web-based therapy strategy that tackles anxiety along with CBT for functional abdominal pain.

“Anxiety is common and related to poor outcomes,” noted Dr. Cunningham, She added that overall, half or more of individuals with chronic pain also have anxiety. Among children with FAPD, “Clinical anxiety predicts disability and poor treatment response.”

The first step, she said, was identifying the patients with FAPD who had anxiety, including those with subclinical anxiety.

At intake, children coming to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s gastroenterology clinic complete anxiety screening via the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) (Depress Anxiety. 2000;12[2]:85-91). Disability and pain are assessed by the Functional Disability Inventory and the Numeric Rating Scale (J Pediatr Psychol. 1991 Feb;16[1]:39-58).

In earlier research, Dr. Cunningham and her collaborators found a significant association between anxiety and both higher pain levels and more disability. And, clinically significant anxiety was more likely among the FAPD patients with persistent disability after six months of treatment.

A surprising finding from the screenings, said Dr. Cunningham, is that youth endorsed more anxiety symptoms in self-assessment than their parents observed. “Children are often their own best informants of their internalizing symptoms,” she said. “Not only do their parents not notice it, it may not be obvious to their providers, either.”

Since many children with FAPD have anxiety, the next question was “How do we better enhance their treatments?” she continued. To answer that question, she took one step back: “How do these youth respond to our current best practice?”

Looking at Cincinnati Children’s patients with FAPD who did – or did not – have anxiety, Dr. Cunningham found that “those who have clinical levels of anxiety don’t respond as well to CBT.” Pain-directed therapy alone, she said, “is insufficient to treat these patients.”

Together with brief screening, stepped therapy delivered via ADAPT offers promise to boost the efficacy of FAPD treatment, perhaps even in a primary care setting, said Dr. Cunningham. She and her collaborators are continuing to study comorbid anxiety and pain in youth; current work is using functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine cognitive and affective changes in patients receiving the ADAPT intervention.

The study was funded by the American Pain Society Sharon S. Keller Chronic Pain Research Grant, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cunningham N. et al. APS 2019.

MILWAUKEE – A stepped-care approach to youth with functional abdominal pain disorders may be effective in targeting those with comorbid anxiety, according to ongoing research.

A study of 79 pediatric patients with a functional abdominal pain disorder (FAPD) and co-occurring anxiety found that those who received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that included a component to address anxiety had less functional disability and anxiety than those who received treatment as usual. Pain scores also dropped, though the difference was not statistically significant.

The patients, aged 9-14 years and mostly white and female, were randomized to treatment allocation. Functional disability scores were significantly lower post-treatment for those who received the stepped therapy compared with the treatment as usual group (P less than .05, Cohen’s D = .49). This indicates a moderate effect size, said Natoshia Cunningham, PhD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Mean scores on an anxiety rating scale also dropped below the threshold for clinical anxiety for those receiving the stepped therapy; on average, the treatment as usual group still scored above the clinical anxiety threshold after treatment (P for difference = .05).

The study, part of ongoing research, tests a hybrid online intervention, dubbed Aim to Decrease Anxiety and Pain Treatment, or ADAPT. The ADAPT program includes some common elements of CBT for anxiety that were not previously included in the pediatric pain CBT in use for the FAPD patients, she said.

The hybrid program began with two in-person sessions, each lasting one hour. These were followed by up to four web-based sessions. Patients viewed videos, read some material online, and complete activities with follow-up assessments. The web-based component was structured so that providers can see how patients fare on assessments – and even see which activities had been opened or completed. This, said Dr. Cunningham, allowed the treating provider to tailor what’s addressed in the associated weekly phone checks that accompany the online content.

Parents were also given practical, evidence-based advice to help manage their child’s FAPD. These include encouraging children to be independent in pain management, stopping “status checks,” encouraging normal school and social activities, and avoiding special privileges when pain interferes with activities.

Overall, up to 40% of pediatric functional abdominal pain patients may not respond to CBT, the most efficacious treatment known, said Dr. Cunningham, a pediatric psychologist at the University of Cincinnati. Her research indicates that comorbid anxiety may predict poor response, and that addressing anxiety improves pain and disability in this complex, common disorder.

With a brief psychosocial screening that identifies patients with anxiety, Dr. Cunningham and her colleagues can implement the targeted, partially web-based therapy strategy that tackles anxiety along with CBT for functional abdominal pain.

“Anxiety is common and related to poor outcomes,” noted Dr. Cunningham, She added that overall, half or more of individuals with chronic pain also have anxiety. Among children with FAPD, “Clinical anxiety predicts disability and poor treatment response.”

The first step, she said, was identifying the patients with FAPD who had anxiety, including those with subclinical anxiety.

At intake, children coming to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s gastroenterology clinic complete anxiety screening via the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) (Depress Anxiety. 2000;12[2]:85-91). Disability and pain are assessed by the Functional Disability Inventory and the Numeric Rating Scale (J Pediatr Psychol. 1991 Feb;16[1]:39-58).

In earlier research, Dr. Cunningham and her collaborators found a significant association between anxiety and both higher pain levels and more disability. And, clinically significant anxiety was more likely among the FAPD patients with persistent disability after six months of treatment.

A surprising finding from the screenings, said Dr. Cunningham, is that youth endorsed more anxiety symptoms in self-assessment than their parents observed. “Children are often their own best informants of their internalizing symptoms,” she said. “Not only do their parents not notice it, it may not be obvious to their providers, either.”

Since many children with FAPD have anxiety, the next question was “How do we better enhance their treatments?” she continued. To answer that question, she took one step back: “How do these youth respond to our current best practice?”

Looking at Cincinnati Children’s patients with FAPD who did – or did not – have anxiety, Dr. Cunningham found that “those who have clinical levels of anxiety don’t respond as well to CBT.” Pain-directed therapy alone, she said, “is insufficient to treat these patients.”

Together with brief screening, stepped therapy delivered via ADAPT offers promise to boost the efficacy of FAPD treatment, perhaps even in a primary care setting, said Dr. Cunningham. She and her collaborators are continuing to study comorbid anxiety and pain in youth; current work is using functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine cognitive and affective changes in patients receiving the ADAPT intervention.

The study was funded by the American Pain Society Sharon S. Keller Chronic Pain Research Grant, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cunningham N. et al. APS 2019.

MILWAUKEE – A stepped-care approach to youth with functional abdominal pain disorders may be effective in targeting those with comorbid anxiety, according to ongoing research.

A study of 79 pediatric patients with a functional abdominal pain disorder (FAPD) and co-occurring anxiety found that those who received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that included a component to address anxiety had less functional disability and anxiety than those who received treatment as usual. Pain scores also dropped, though the difference was not statistically significant.

The patients, aged 9-14 years and mostly white and female, were randomized to treatment allocation. Functional disability scores were significantly lower post-treatment for those who received the stepped therapy compared with the treatment as usual group (P less than .05, Cohen’s D = .49). This indicates a moderate effect size, said Natoshia Cunningham, PhD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Mean scores on an anxiety rating scale also dropped below the threshold for clinical anxiety for those receiving the stepped therapy; on average, the treatment as usual group still scored above the clinical anxiety threshold after treatment (P for difference = .05).

The study, part of ongoing research, tests a hybrid online intervention, dubbed Aim to Decrease Anxiety and Pain Treatment, or ADAPT. The ADAPT program includes some common elements of CBT for anxiety that were not previously included in the pediatric pain CBT in use for the FAPD patients, she said.

The hybrid program began with two in-person sessions, each lasting one hour. These were followed by up to four web-based sessions. Patients viewed videos, read some material online, and complete activities with follow-up assessments. The web-based component was structured so that providers can see how patients fare on assessments – and even see which activities had been opened or completed. This, said Dr. Cunningham, allowed the treating provider to tailor what’s addressed in the associated weekly phone checks that accompany the online content.

Parents were also given practical, evidence-based advice to help manage their child’s FAPD. These include encouraging children to be independent in pain management, stopping “status checks,” encouraging normal school and social activities, and avoiding special privileges when pain interferes with activities.

Overall, up to 40% of pediatric functional abdominal pain patients may not respond to CBT, the most efficacious treatment known, said Dr. Cunningham, a pediatric psychologist at the University of Cincinnati. Her research indicates that comorbid anxiety may predict poor response, and that addressing anxiety improves pain and disability in this complex, common disorder.

With a brief psychosocial screening that identifies patients with anxiety, Dr. Cunningham and her colleagues can implement the targeted, partially web-based therapy strategy that tackles anxiety along with CBT for functional abdominal pain.

“Anxiety is common and related to poor outcomes,” noted Dr. Cunningham, She added that overall, half or more of individuals with chronic pain also have anxiety. Among children with FAPD, “Clinical anxiety predicts disability and poor treatment response.”

The first step, she said, was identifying the patients with FAPD who had anxiety, including those with subclinical anxiety.

At intake, children coming to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s gastroenterology clinic complete anxiety screening via the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) (Depress Anxiety. 2000;12[2]:85-91). Disability and pain are assessed by the Functional Disability Inventory and the Numeric Rating Scale (J Pediatr Psychol. 1991 Feb;16[1]:39-58).

In earlier research, Dr. Cunningham and her collaborators found a significant association between anxiety and both higher pain levels and more disability. And, clinically significant anxiety was more likely among the FAPD patients with persistent disability after six months of treatment.

A surprising finding from the screenings, said Dr. Cunningham, is that youth endorsed more anxiety symptoms in self-assessment than their parents observed. “Children are often their own best informants of their internalizing symptoms,” she said. “Not only do their parents not notice it, it may not be obvious to their providers, either.”

Since many children with FAPD have anxiety, the next question was “How do we better enhance their treatments?” she continued. To answer that question, she took one step back: “How do these youth respond to our current best practice?”

Looking at Cincinnati Children’s patients with FAPD who did – or did not – have anxiety, Dr. Cunningham found that “those who have clinical levels of anxiety don’t respond as well to CBT.” Pain-directed therapy alone, she said, “is insufficient to treat these patients.”

Together with brief screening, stepped therapy delivered via ADAPT offers promise to boost the efficacy of FAPD treatment, perhaps even in a primary care setting, said Dr. Cunningham. She and her collaborators are continuing to study comorbid anxiety and pain in youth; current work is using functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine cognitive and affective changes in patients receiving the ADAPT intervention.

The study was funded by the American Pain Society Sharon S. Keller Chronic Pain Research Grant, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cunningham N. et al. APS 2019.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

High ankle sprains: Easy to miss, so follow these tips

CASE

A 19-year-old college football player presents to your outpatient family practice clinic after suffering a right ankle injury during a football game over the weekend. He reports having his right ankle planted on the turf with his foot externally rotated when an opponent fell onto his posterior right lower extremity. He reports having felt immediate pain in the area of the right ankle and requiring assistance off of the field, as he had difficulty walking. The patient was taken to the emergency department where x-rays of the right foot and ankle did not show any signs of acute fracture or dislocation. The patient was diagnosed with a lateral ankle sprain, placed in a pneumatic ankle walking brace, and given crutches.

A high ankle sprain, or distal tibiofibular syndesmotic injury, can be an elusive diagnosis and is often mistaken for the more common lateral ankle sprain. Syndesmotic injuries have been documented to occur in approximately 1% to 10% of all ankle sprains.1-3 The highest number of these injuries occurs between the ages of 18 and 34 years, and they are more frequently seen in athletes than in nonathletes, particularly those who play collision sports, such as football, ice hockey, rugby, wrestling, and lacrosse.1-9 In one study by Hunt et al,10 syndesmotic injuries accounted for 24.6% of all ankle injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football players. Incidence continues to grow as recognition of high ankle sprains increases among medical professionals.1,5 Identification of syndesmotic injury is critical, as lack of detection can lead to extensive time missed from athletic participation and chronic ankle dysfunction, including pain and instability.2,4,6,11

Back to basics: A brief anatomy review

Stability in the distal tibiofibular joint is maintained by the syndesmotic ligaments, which include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), the transverse ligament, and the interosseous ligament.3-6,8 This complex of ligaments stabilizes the fibula within the incisura of the tibia and maintains a stable ankle mortise.1,4,5,11 The deep portion of the deltoid ligament also adds stability to the syndesmosis and may be disrupted by a syndesmotic injury.2,5-7,11

Mechanisms of injury: From most common to less likely

The distal tibiofibular syndesmosis is disrupted when an injury forces apart the distal tibiofibular joint. The most commonly reported means of injury is external rotation with hyper-dorsiflexion of the ankle.1-3,5,6,11 With excessive external rotation of the forefoot, the talus is forced against the medial aspect of the fibula, resulting in separation of the distal tibia and fibula and injury to the syndesmotic ligaments.2,3,5,6 Injuries associated with external rotation are commonly seen in sports that immobilize the ankle within a rigid boot, such as skiing and ice hockey.1,2,5 Some authors have suggested that a planovalgus foot alignment may place athletes at inherent risk for an external rotation ankle injury.5,6

Syndesmotic injury may also occur with hyper-dorsiflexion, as the anterior, widest portion of the talus rotates into the ankle mortise, wedging the tibia and fibula apart.2,3,5 There have also been reports of syndesmotic injuries associated with internal rotation, plantar flexion, inversion, and eversion.3,5,11 Therefore, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for injury to the distal tibiofibular joint, regardless of the mechanism of injury.

Presentation and evaluation

Observation of the patient and visualization of the affected ankle can provide many clues. Many patients will have difficulty walking after suffering a syndesmotic injury and may require the use of an assistive device.5 The inability to bear weight after an ankle injury points to a more severe diagnosis, such as an ankle fracture or syndesmotic injury, as opposed to a simple lateral ankle sprain. Patients may report anterior ankle pain, a sensation of instability with weight bearing on the affected ankle, or have persistent symptoms despite a course of conservative treatment. Also, they can have a variable amount of edema and ecchymosis associated with their injury; a minimal extent of swelling or ecchymosis does not exclude syndesmotic injury.3

A large percentage of patients will present with a concomitant sprain of the lateral ligaments associated with lateral swelling and bruising. One study found that 91% of syndesmotic injuries involved at least 1 of the lateral collateral ligaments (anterior talofibular ligament [ATFL], calcaneofibular ligament [CFL], or posterior talofibular ligament [PTFL]).12 Patients may have pain or a sensation of instability when pushing off with the toes,5 and patients with syndesmotic injuries often have tenderness to palpation over the distal anterolateral ankle or syndesmotic ligaments.7

Continue to: A thorough examination...

A thorough examination of the ankle, including palpation of common fracture sites, is important. Employ the Ottawa Ankle Rules (see http://www.theottawarules.ca/ankle_rules) to investigate for: tenderness to palpation over the posterior 6 cm of the posterior aspects of the distal medial and lateral malleoli; tenderness over the navicular; tenderness over the base of the fifth metatarsal; and/or the inability to bear weight on the affected lower extremity immediately after injury or upon evaluation in the physician’s office. Any of these findings should raise concern for a possible fracture (see “Adult foot fractures: A guide”) and require an x-ray(s) for further evaluation.13

Perform range-of-motion and strength testing with regard to ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, abduction, adduction, inversion, and eversion. Palpate the ATFL, CFL, and PTFL for tenderness, as these structures may be involved to varying degrees in lateral ankle sprains. An anterior drawer test (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAcBEYZKcto) may be positive with injury to the ATFL. This test is performed by stabilizing the distal tibia with one hand and using the other hand to grasp the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and apply an anterior force. The test is positive if the talus translates forward, which correlates with laxity or rupture of the ATFL.13 The examiner should also palpate the Achilles tendon, peroneal tendons just posterior to the lateral malleolus, and the tibialis posterior tendon just posterior to the medial malleolus to inspect for tenderness or defects that may be signs of injury to these tendons.

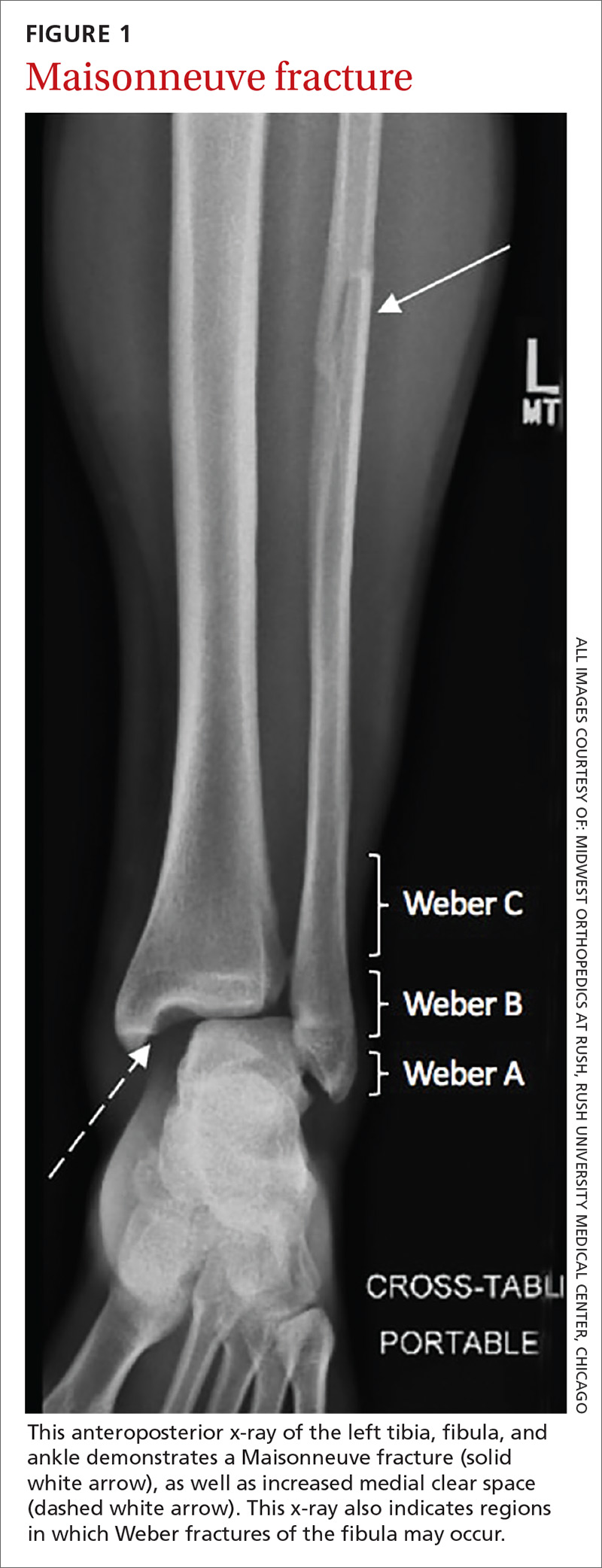

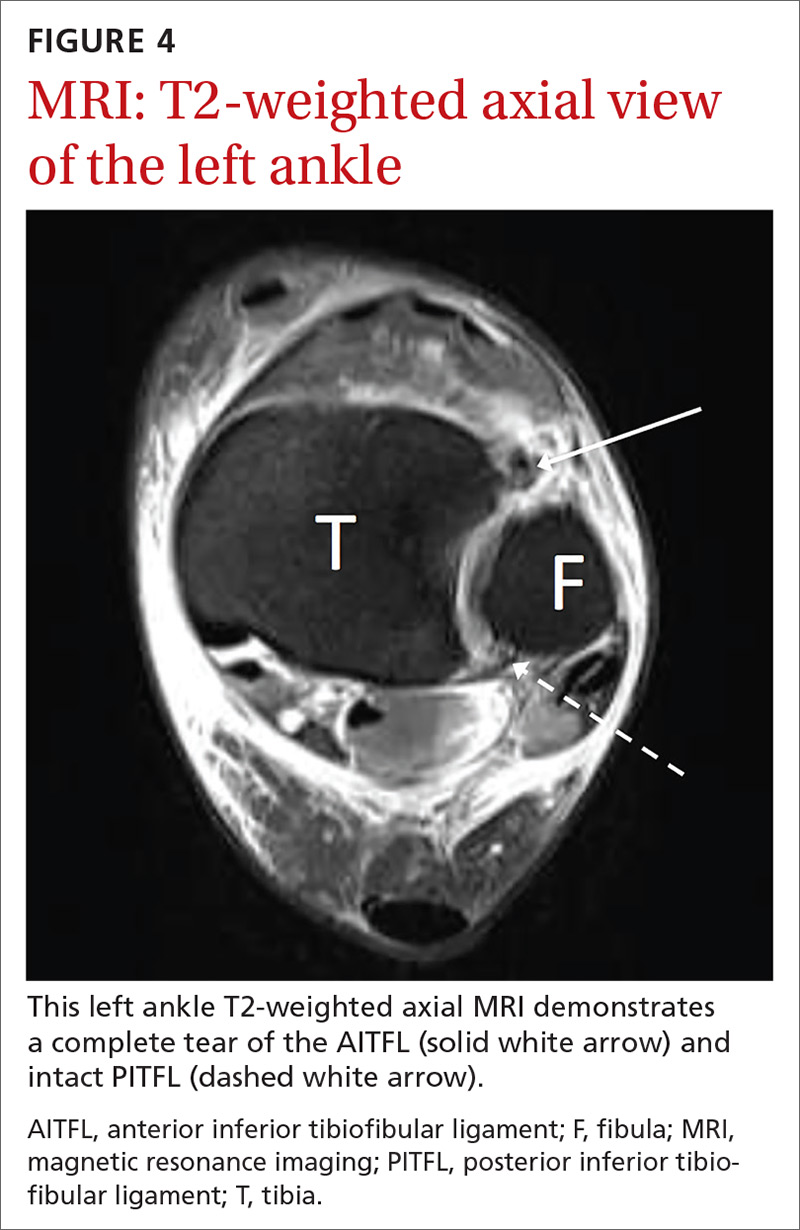

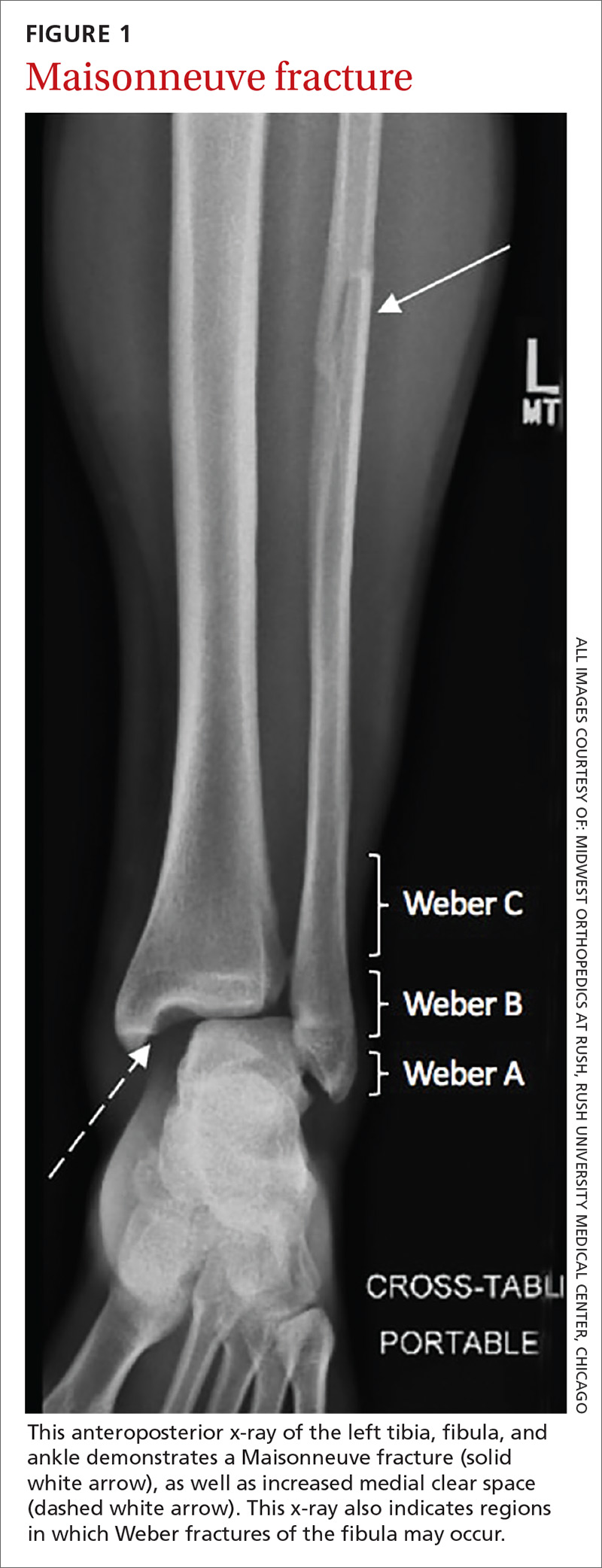

An associated Weber B or C fracture? Trauma causing ankle syndesmosis injuries may be associated with Weber B or Weber C distal fibula fractures.7 Weber B fractures occur in the distal fibula at the level of the ankle joint (see FIGURE 1). These types of fractures are typically associated with external rotation injuries and are usually not associated with disruption of the interosseous membrane.

Weber C fractures are distal fibular fractures occurring above the level of the ankle joint. These fractures are also typically associated with external ankle rotation injuries and include disruption of the syndesmosis and deltoid ligament.14

Also pay special attention to the proximal fibula, as syndesmotic injuries are commonly associated with a Maisonneuve fracture, which is a proximal fibula fracture associated with external rotation forces of the ankle (see FIGURE 1).1,2,4,11,14,15 Further workup should occur in any patient with the possibility of a Weber- or Maisonneuve-type fracture.

Continue to: Multiple tests...

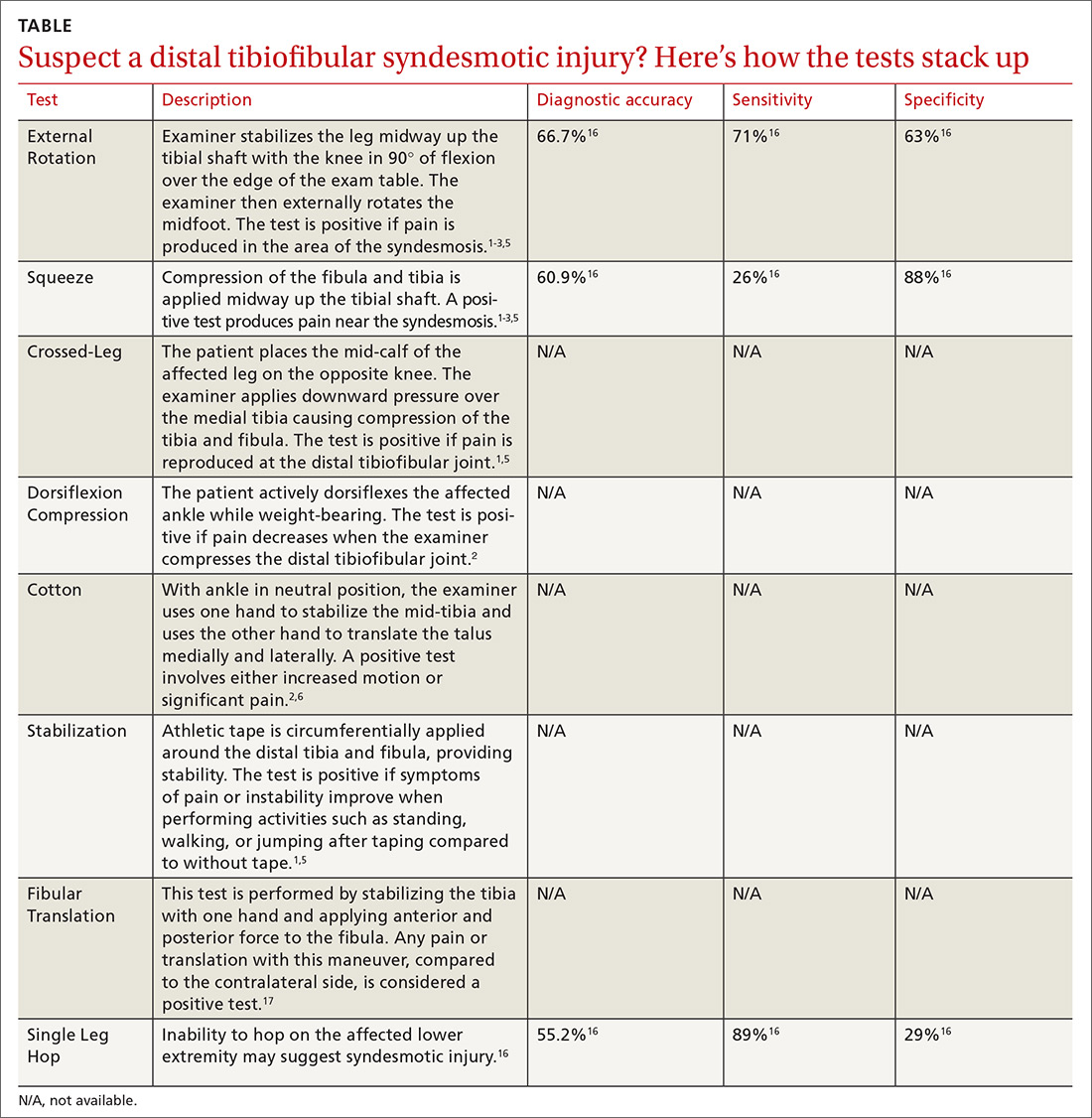

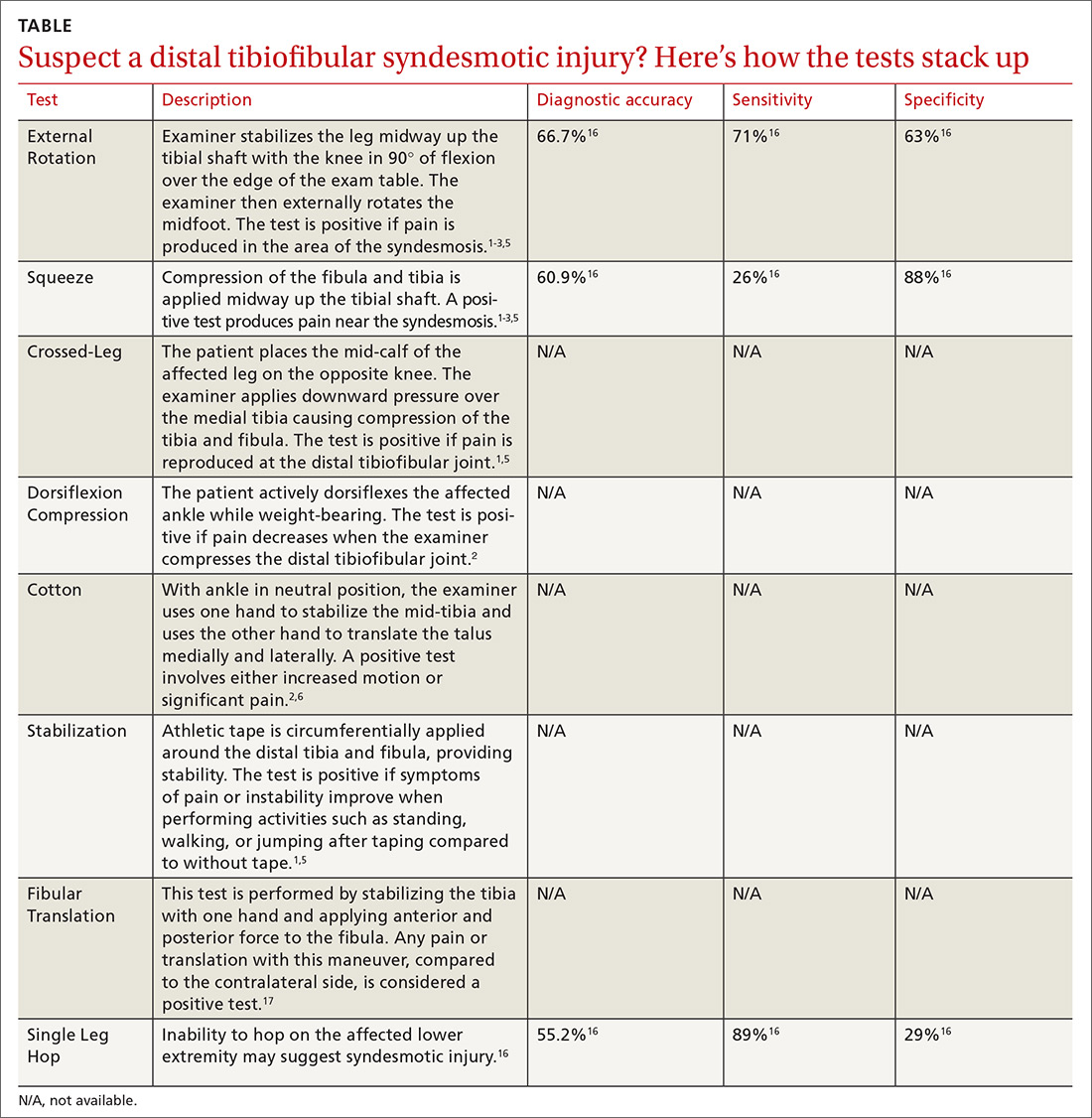

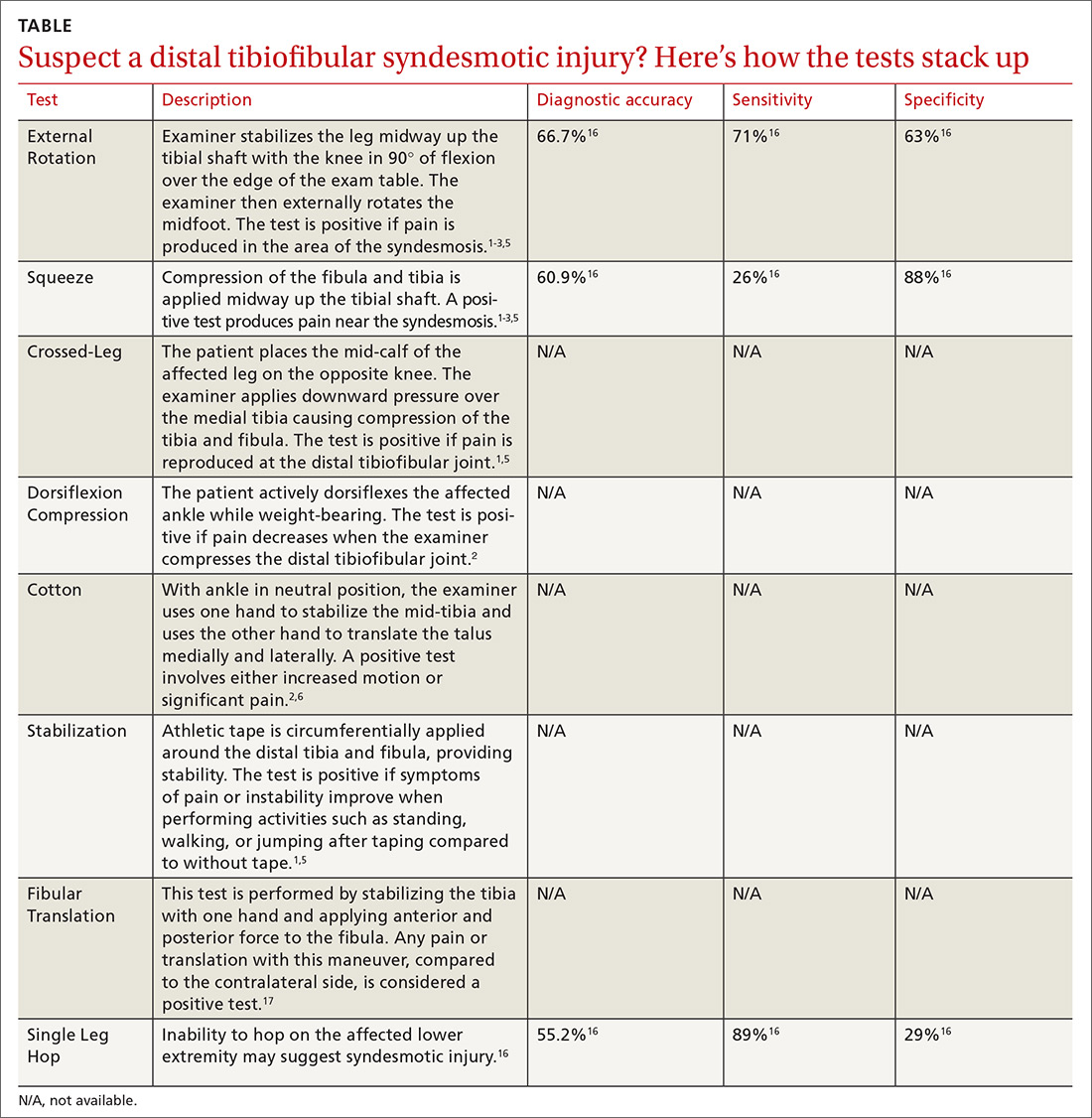

Multiple tests are available to investigate the possibility of a syndesmotic injury and to assess return-to-sport readiness, including the External Rotation Test, the Squeeze Test, the Crossed-Leg Test, the Dorsiflexion Compression Test, the Cotton Test, the Stabilization Test, the Fibular Translation Test, and the Single Leg Hop Test (see TABLE1-3,5,6,16,17). The External Rotation Test is noted by some authors to have the highest interobserver reliability, and is our preferred test.2 The Squeeze Test also has moderate interobserver reliability.2 There is a significant degree of variation among the sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic tests, and no single test is sufficiently reliable or accurate to diagnose a syndesmotic ankle injury. Therefore, it is recommended to use multiple physical exam maneuvers, the history and mechanism of injury, and findings on imaging studies in conjunction to make the diagnosis of a syndesmotic injury.1,16

Imaging: Which modes and when?

The initial workup should include ankle x-rays when evaluating for the possibility of a distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury. While the Ottawa Ankle Rules are helpful in providing guidance with regard to x-rays, suspicion of a syndesmotic injury mandates x-rays to determine the stability of the joint and rule out fracture. The European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy–European Foot and Ankle Associates (ESSKA-AFAS) recommend, at a minimum, obtaining anteroposterior (AP)- and mortise-view ankle x-rays to investigate the tibiofibular clear space, medial clear space, and tibiofibular overlap.7 Most physicians also include a lateral ankle x-ray.

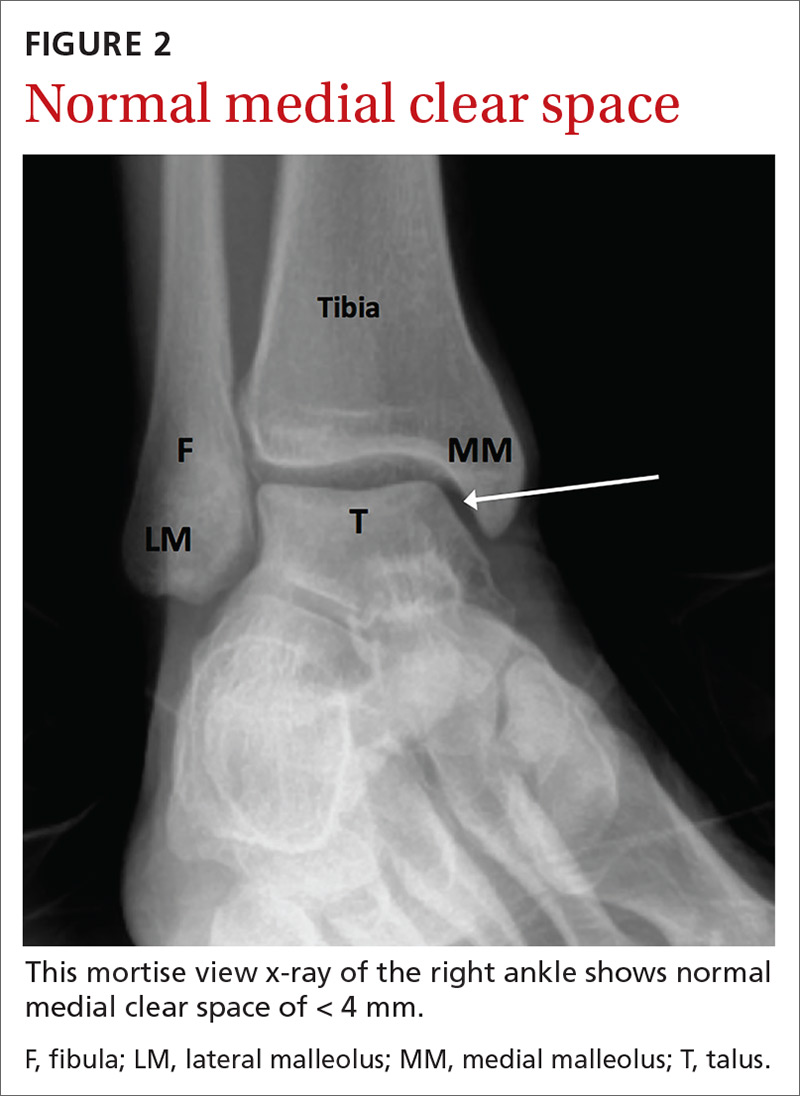

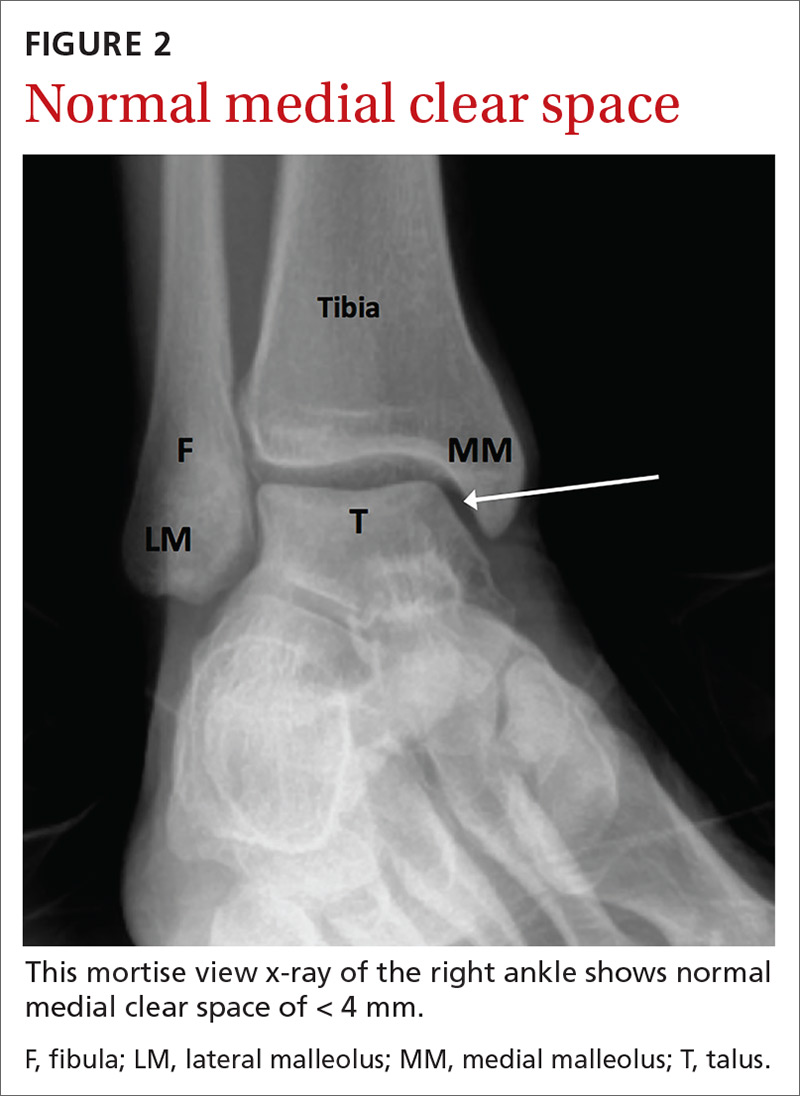

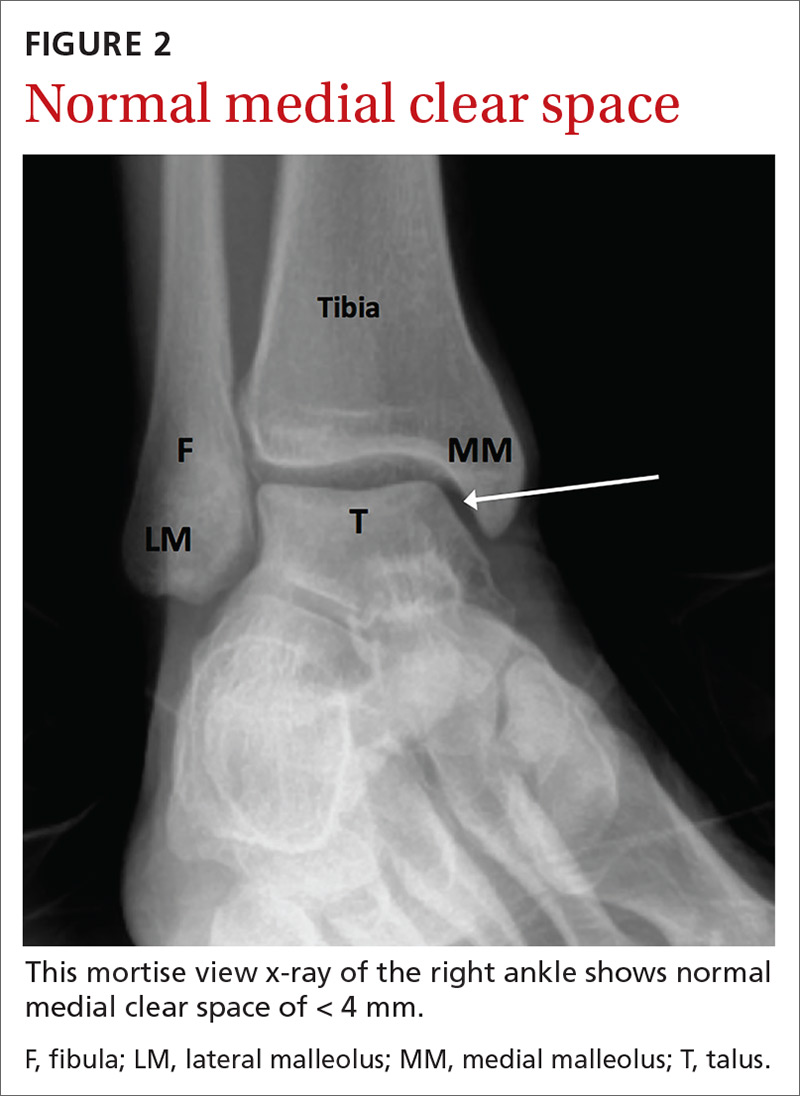

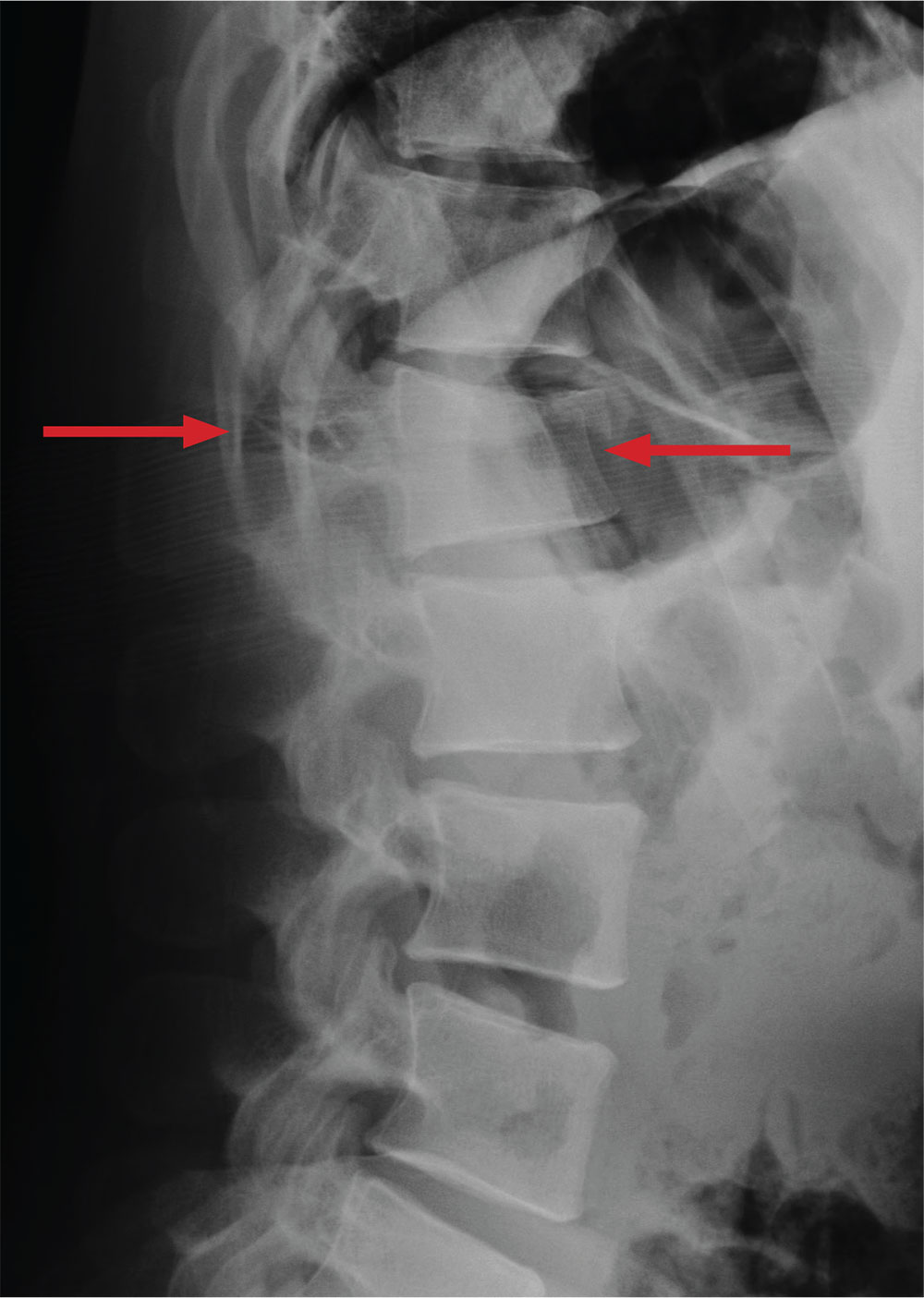

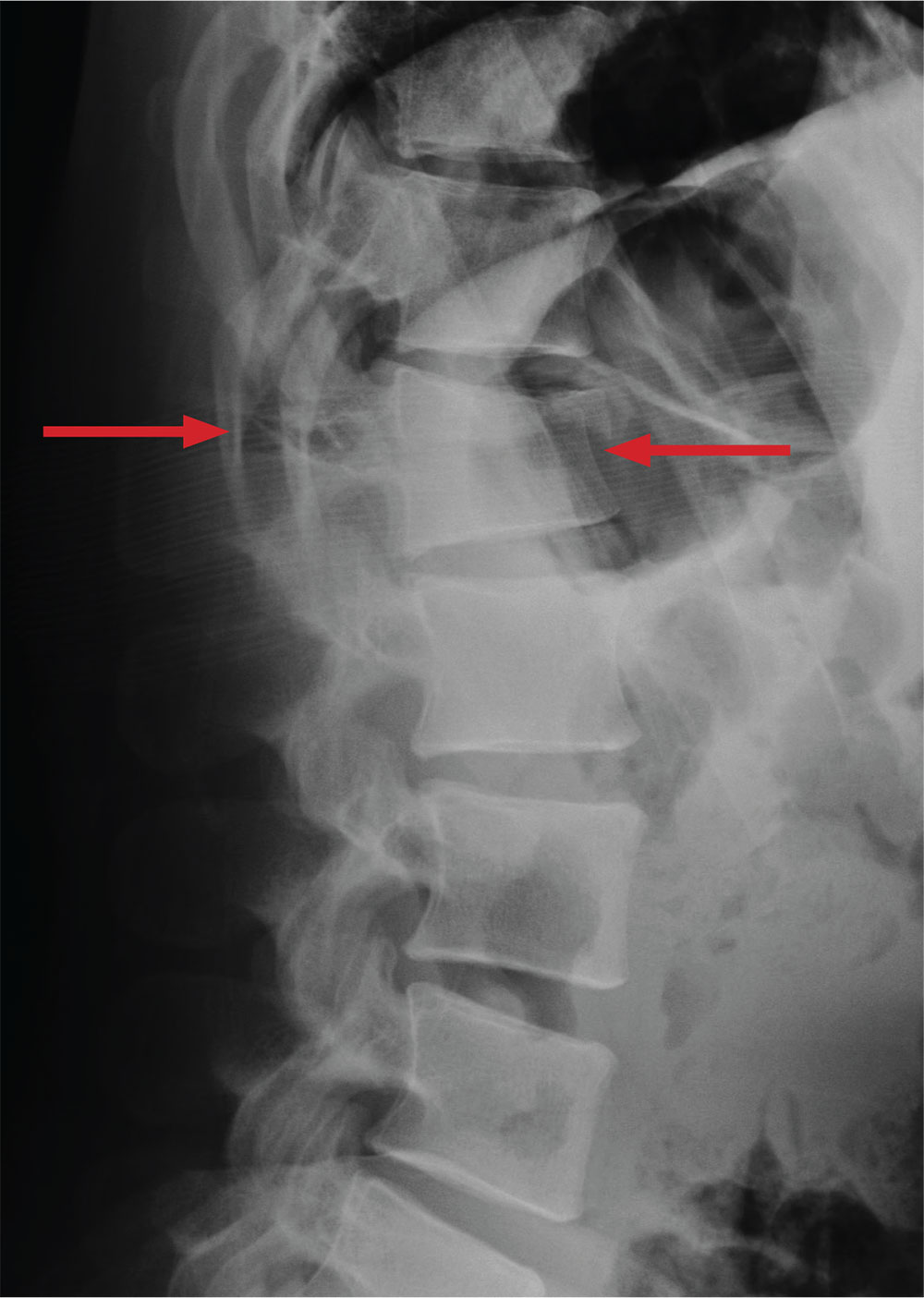

If possible, images should be performed while the patient is bearing weight to further evaluate stability. Radiographic findings that support the diagnosis of syndesmotic injury include a tibiofibular clear space > 6 mm on AP view, medial clear space > 4 mm on mortise view, or tibiofibular overlap < 6 mm on AP view or < 1 mm on mortise view (see FIGURES 2 and 3).1,3,5,8 Additionally, if you suspect a proximal fibular fracture, obtain an x-ray series of the proximal tibia and fibula to investigate the possibility of a Maisonneuve injury.1,2,4,11

If you continue to suspect a syndesmotic injury despite normal x-rays, obtain stress x-rays, in addition to the AP and mortise views, to ensure stability. These x-rays include AP and mortise ankle views with manual external rotation of the ankle joint, which may demonstrate abnormalities not seen on standard x-rays. Bilateral imaging can also be useful to further assess when mild abnormalities vs symmetric anatomic variants are in question.1,7

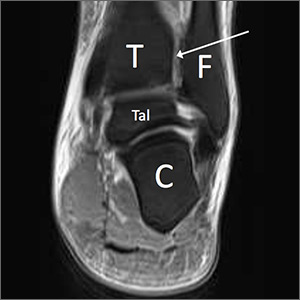

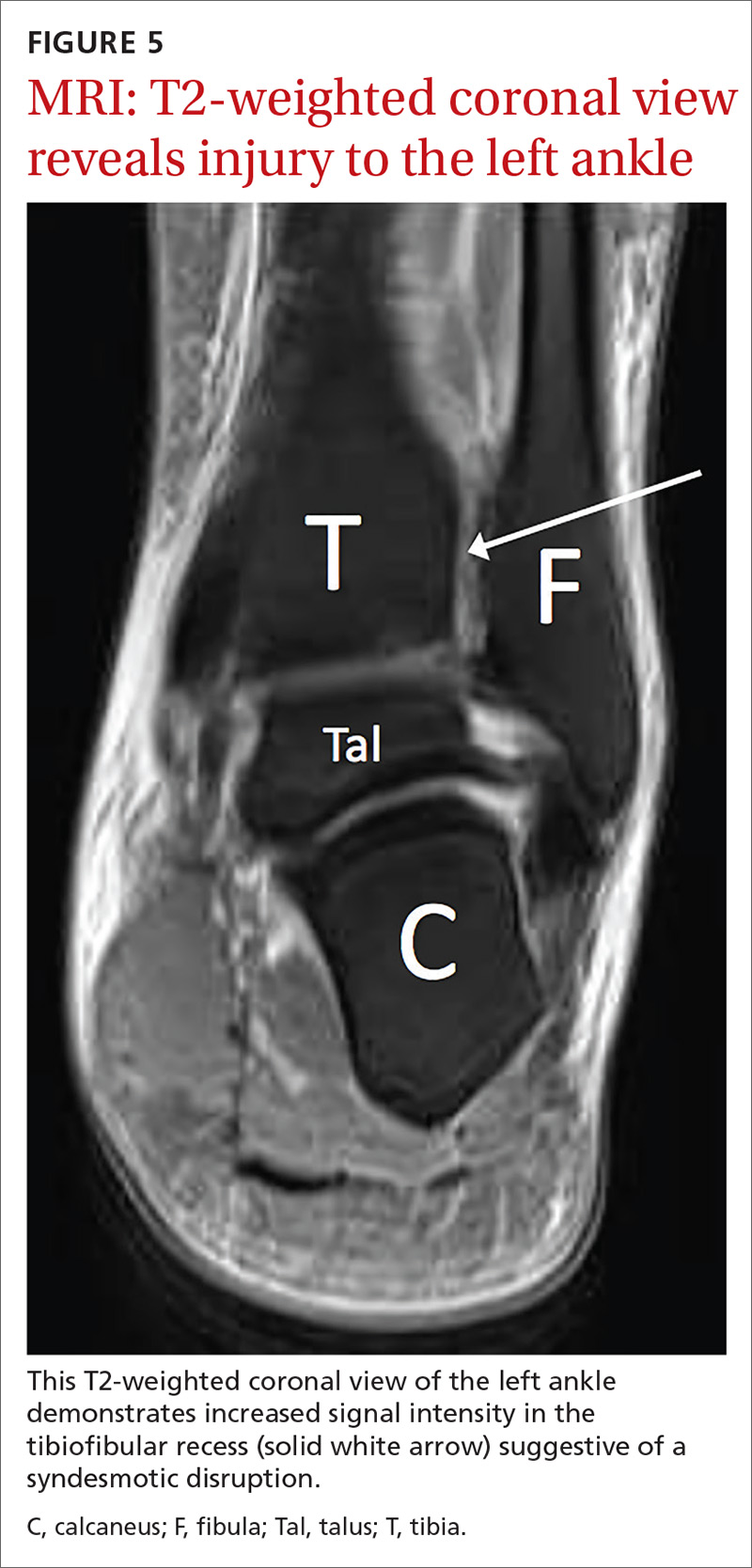

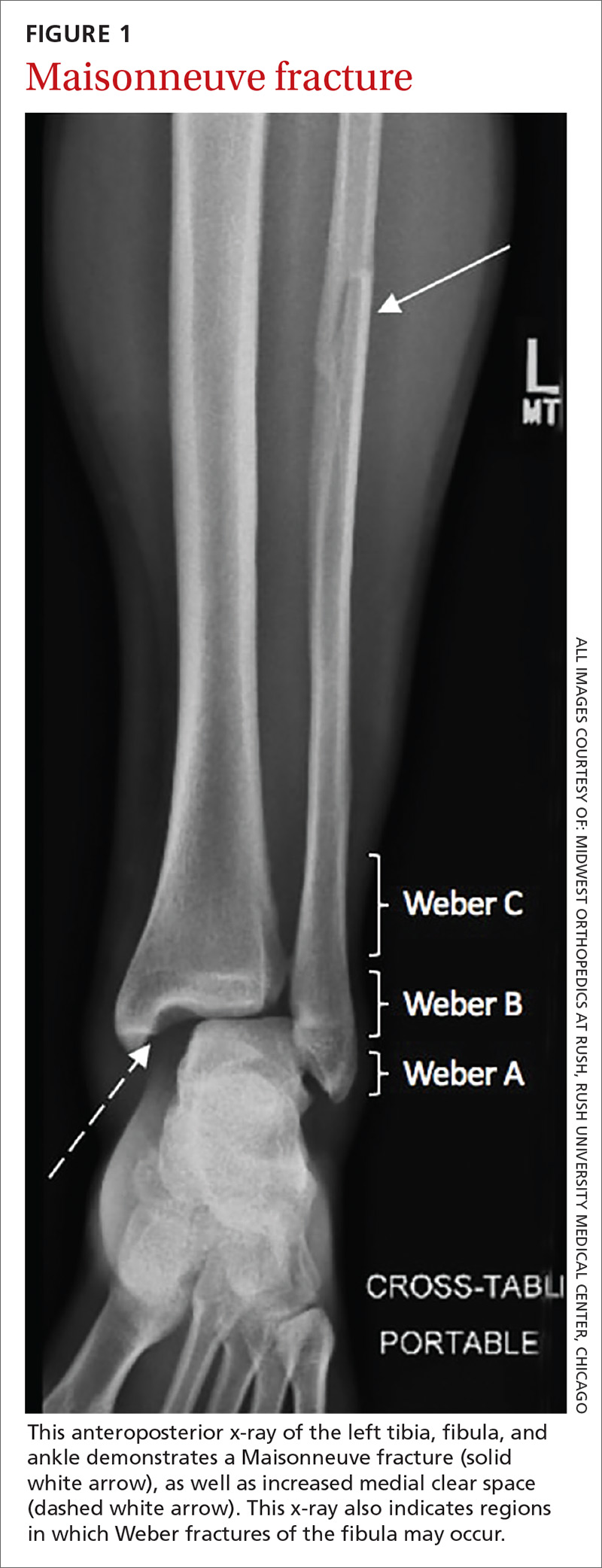

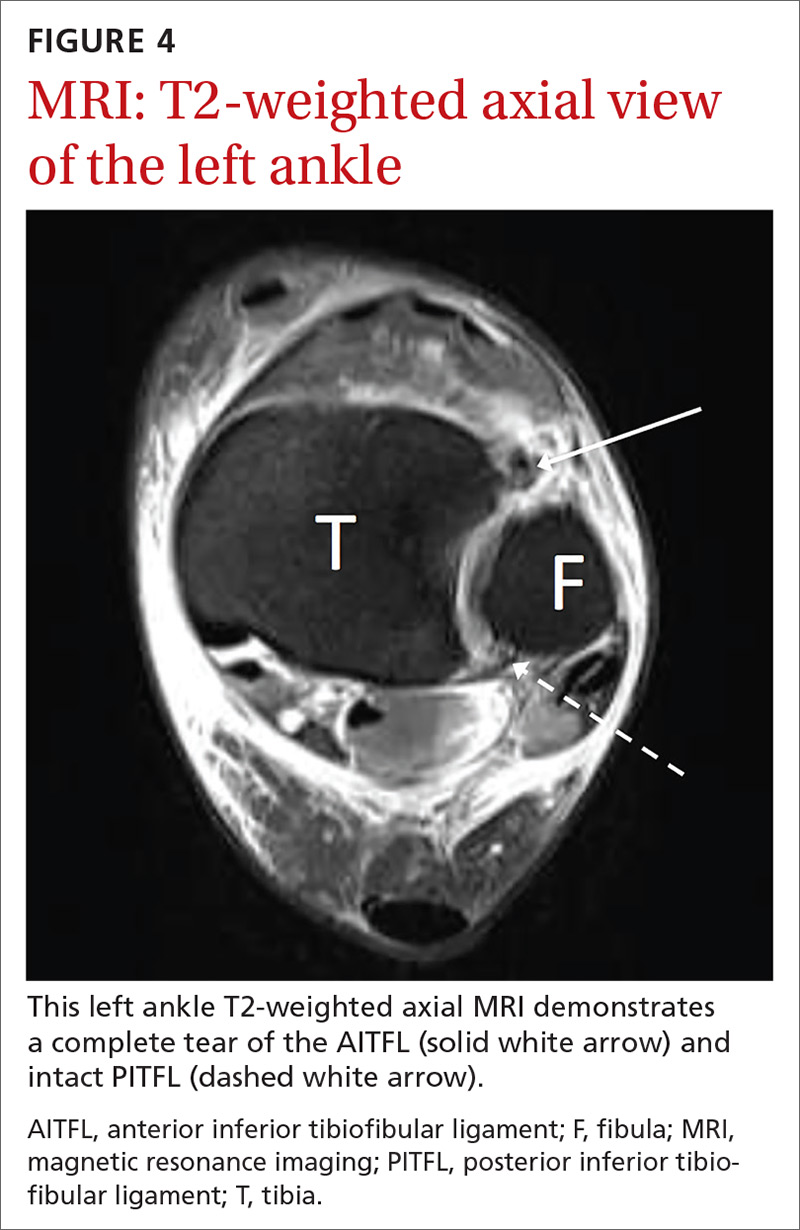

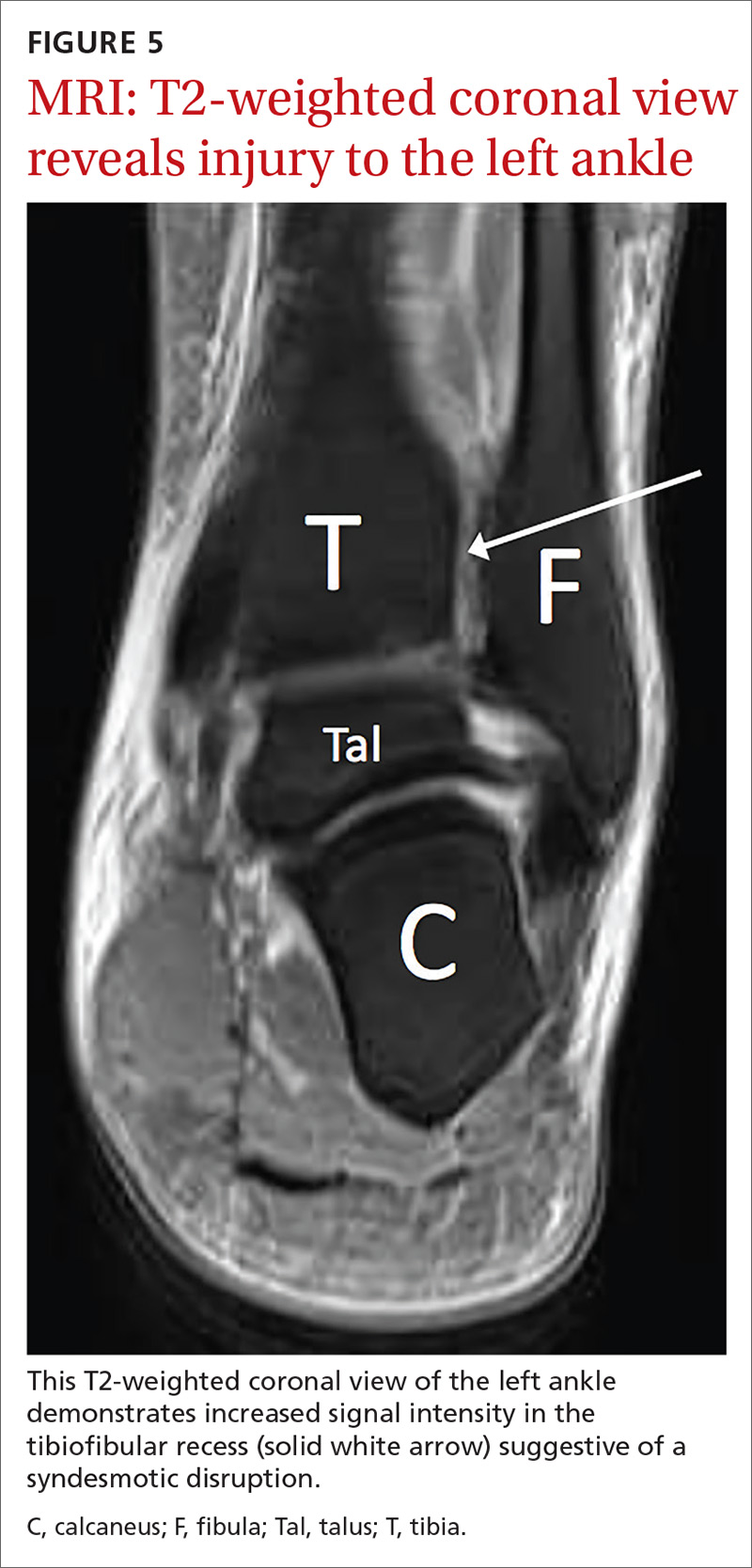

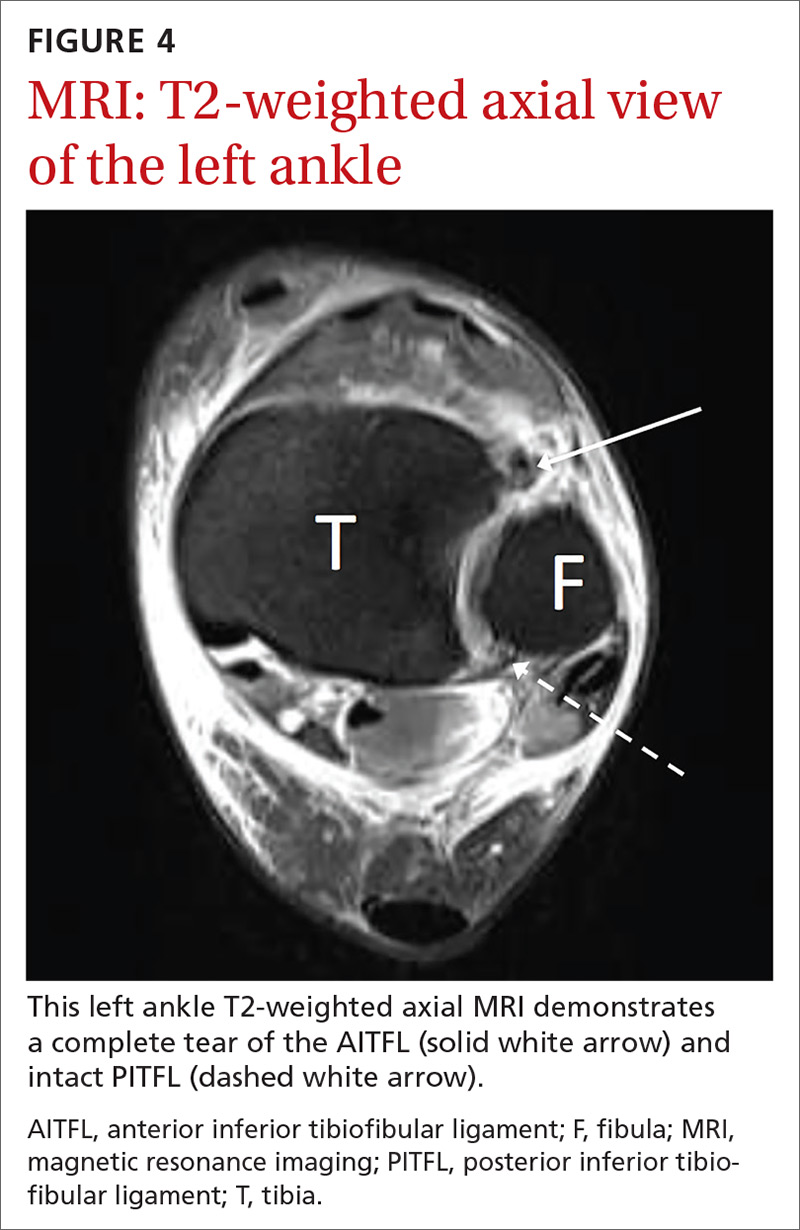

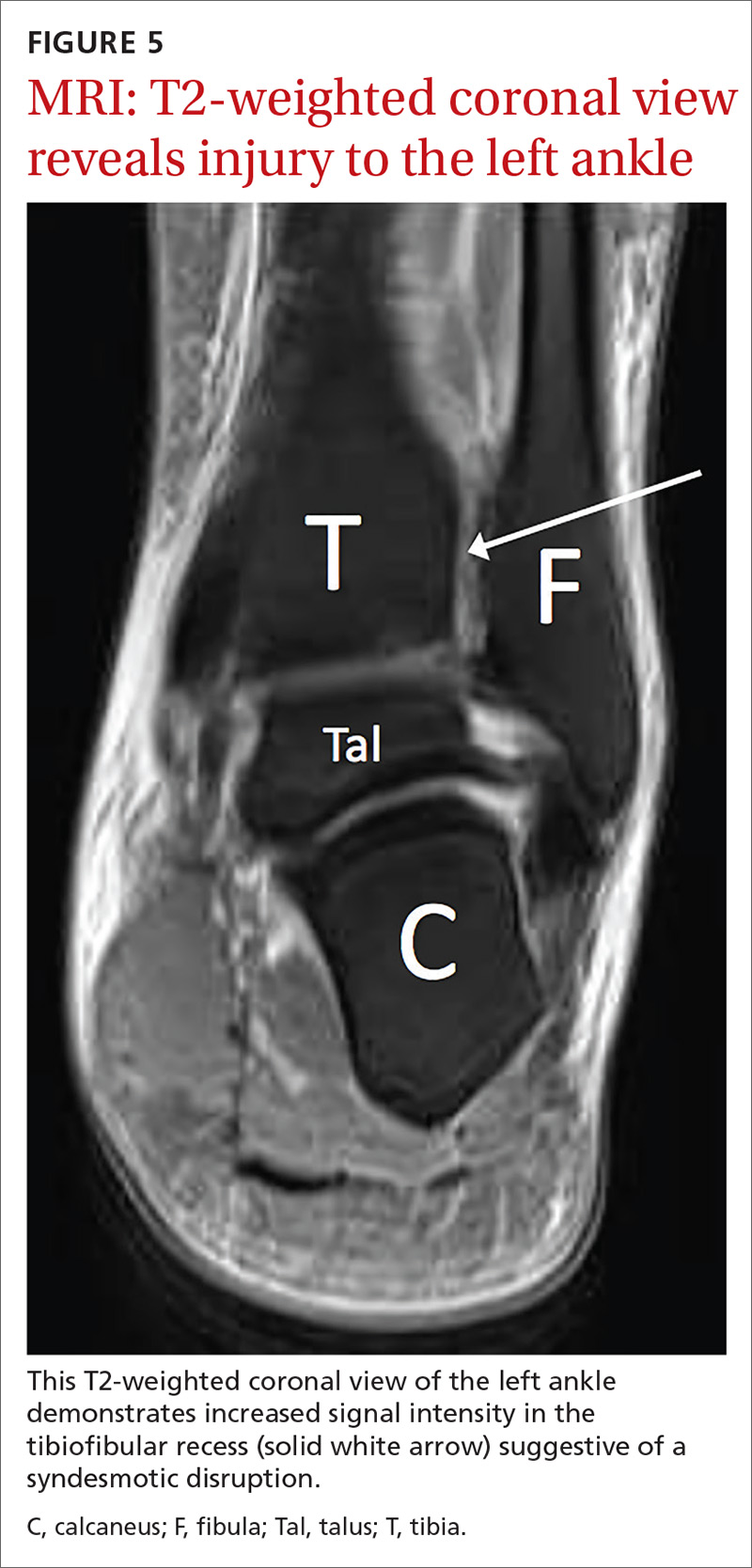

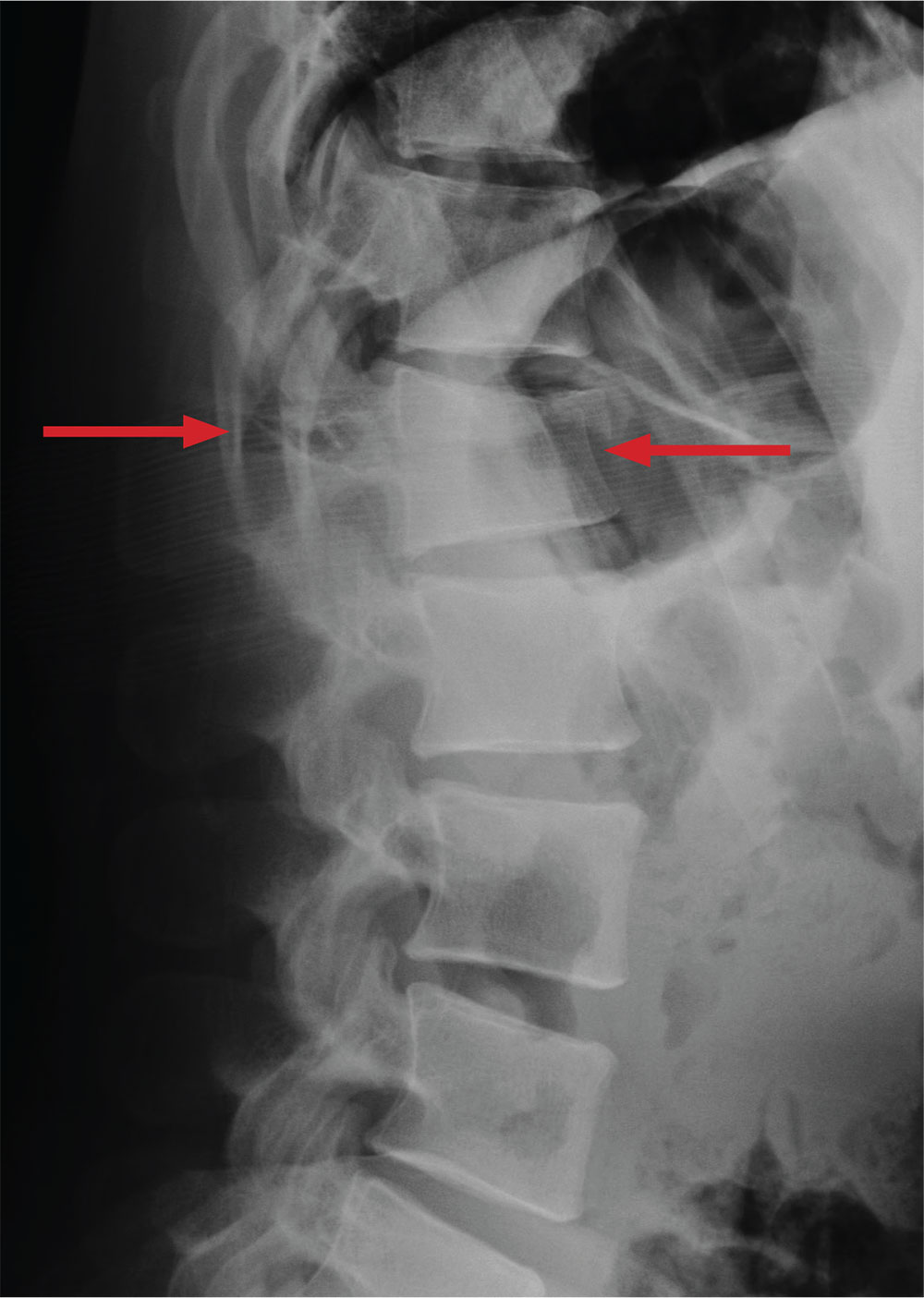

If there is concern for an unstable injury, refer the patient to a foot and ankle surgeon, who may pursue magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or standing computed tomography (CT).1,2,5,7 MRI is the recommended choice for further evaluation of a syndesmotic injury, as it is proven to be accurate in evaluating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments (see FIGURES 4 and 5).18 MRI has demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detecting AITFL and PITFL injuries, as well as 93% and 100% specificity for AITFL and PITFL tears, respectively.8 A weight-bearing CT scan, particularly axial views, can also be a useful adjunct, as it is more sensitive than standard x-rays for assessing for mild diastasis. Although CT can provide an assessment of bony structures, it is not able to evaluate soft tissue structures, limiting its utility in evaluation of syndesmotic injuries.1,7

Continue to: Although not the standard of care...

Although not the standard of care, ultrasonography (US) is gaining traction as a means of investigating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments. US is inexpensive, readily available in many clinics, allows for dynamic testing, and avoids radiation exposure.7 However, US requires a skilled sonographer with experience in the ankle joint for an accurate diagnosis. If the workup with advanced imaging is inconclusive, but a high degree of suspicion remains for an unstable syndesmotic injury, consider arthroscopy to directly visualize and assess the syndesmotic structures.1,2,5,7,8

Grading the severity of the injury and pursuing appropriate Tx

Typically, the severity of a syndesmotic injury is classified as fitting into 1 of 3 categories: Grade I and II injuries are the most common, each accounting for 40% of syndesmotic injuries, while 20% of high ankle sprains are classified as Grade III.12

A Grade I injury consists of a stable syndesmotic joint without abnormal radiographic findings. There may be associated tenderness to palpation over the distal tibiofibular joint, and provocative testing may be subtle or normal. These injuries are often minor and able to be treated conservatively.

A Grade II injury is associated with a partial syndesmotic disruption, typically with partial tearing of the AITFL and interosseous ligament. These injuries may be stable or accompanied by mild instability, and provocative testing is usually positive. X-rays are typically normal with Grade II injuries, but may display subtle radiographic findings suggestive of a syndesmotic injury. Treatment of Grade II injuries is somewhat controversial and should be an individualized decision based upon the patient’s age, activity level, clinical exam, and imaging findings. Therefore, treatment of Grade II syndesmotic injuries may include a trial of conservative management or surgical intervention.

A Grade III injury represents inherent instability of the distal tibiofibular joint with complete disruption of all syndesmotic ligaments, with or without involvement of the deltoid ligament. X-rays will be positive in Grade III syndesmotic injuries because of the complete disruption of syndesmotic ligaments. All Grade III injuries require surgical intervention with a syndesmotic screw or other stabilization procedure.1,6-8,15

Continue to: A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

When conservative management is deemed appropriate for a stable syndesmotic sprain, a 3-stage rehabilitation protocol is typically utilized.

The acute phase focuses on protection, pain control, and decreasing inflammation. The patient’s ankle is often immobilized in a cast or controlled ankle movement (CAM) boot. The patient is typically allowed to bear weight in the immobilizer during this phase as long as he/she is pain-free. If pain is present with weight bearing despite immobilization, non-weight bearing is recommended. The patient is instructed to elevate the lower extremity, take anti-inflammatory medication, and ice the affected ankle. Additionally, physical therapy modalities may be utilized to help with edema and pain. Joint immobilization is typically employed for 1 to 3 weeks post-injury. In the acute phase, the patient may also work with a physical therapist or athletic trainer on passive range of motion (ROM), progressing to active ROM as tolerated.1,5,7,8,19

The patient can transition from the CAM boot to a lace-up ankle brace when he/she is able to bear full weight and can navigate stairs without pain, which typically occurs around 3 to 6 weeks post-injury.1,5,7 A pneumatic walking brace may also be used as a transition device to provide added stabilization.

In the sub-acute phase, rehabilitation may progress to increase ankle mobility, strengthening, neuromuscular control, and to allow the patient to perform activities of daily living.5-7

The advanced training phase includes continued neuromuscular control, increased strengthening, plyometrics, agility, and sports-specific drills.5 Athletes are allowed to return to full participation when they have regained full ROM, are able to perform sport-specific agility drills without pain or instability, and have near-normal strength.5-7 Some authors also advocate that a Single Leg Hop Test should be included in the physical exam, and that it should be pain free prior to allowing an athlete to return to competition.20 Both progression in physical rehabilitation and return to sport should be individualized based upon injury severity, patient functionality, and physical exam findings.

Continue to: Outcomes forecast

Outcomes forecast: Variable

The resolution of symptoms and return to competition after a syndesmotic injury is variable. In one cohort study of cadets (N = 614) at the United States Military Academy, the average time lost from a syndesmotic ankle sprain was 9.82 days (range 3-21 days).9 In a retrospective review of National Hockey League players, average time to return to competition after a syndesmotic ankle injury sprain (n = 14) was 45 days (range 6-137 days) vs 1.4 days (range 0-6 days) for lateral ankle sprains (n = 5).21 In another study, National Football League players with syndesmotic sprains (n = 36) had a mean time loss from play of 15.4 days (± 11.1 days) vs 6.5 days (± 6.5 days) of time loss from play in those with lateral ankle sprains (n = 53).22

Although there is a fair amount of variability among studies, most authors agree that the average athlete can expect to return to sport 4 to 8 weeks post-injury with conservative management.19 At least 1 study suggests that the average time to return to sport in patients with Grade III syndesmotic injuries who undergo surgical treatment with a syndesmotic screw is 41 days (range 32-48).23 The differences in return to sport may be related to severity of injury and/or type of activity.

Persistent symptoms are relatively common after conservative management of syndesmotic injuries. One case series found that 36% of patients treated conservatively had complaints of persistent mild-to-moderate ankle stiffness, 23% had mild-to-moderate pain, and 18% had mild-to-moderate ankle swelling.24 Despite these symptoms, 86% of the patients rated their ankle function as good after conservative treatment.24 In patients with persistent symptoms, other possible etiologies should be considered including neurologic injury, complex regional pain syndrome, osteochondral defect, loose body, or other sources that may be contributing to pain, swelling, or delayed recovery.

At least 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigated the utility of platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections around the injured AITFL in the setting of an acute syndesmotic injury. The study showed promising results, including quicker return to play, restabilization of the syndesmotic joint, and less residual pain;25 however, the study population was relatively small (N = 16), and the authors believed that more research is required on the benefits of PRP therapy in syndesmotic injuries before recommendations can be made.

An ounce of preventionis worth a pound of cure

Although injury is not always avoidable, there are measures that can help prevent ankle sprains and facilitate return to play after injury. As previously mentioned, athletes should be able to demonstrate the ability to run, cut, jump, and perform sport-specific activities without limitations prior to being allowed to return to sport after injury.5-7,26 Additionally, issues with biomechanics and functional deficits should be analyzed and addressed. By targeting specific strength deficits, focusing on proprioceptive awareness, and working on neuromuscular control, injury rates and recurrent injuries can be minimized. One RCT showed a 35% reduction in the recurrence rate of lateral ankle sprains with the use of an unsupervised home-based proprioceptive training program.27

Continue to: Strength training...

Strength training, proprioceptive and neuromuscular control activities, and low-risk activities such as jogging, biking, and swimming do not necessarily require the use of prophylactic bracing. However, because syndesmotic injuries are associated with recurrent ankle injuries, prophylactic bracing should be used during high-risk activities that involve agility maneuvers and jumping. Substantial evidence demonstrates that the use of ankle taping or ankle bracing decreases the incidence of ankle injuries, particularly in those who have had previous ankle injuries.26 In one study (N = 450), only 3% of athletes with a history of prior ankle injuries suffered a recurrent ankle sprain when using an ankle orthosis compared with a 17% injury rate in the control group.28

More recently, 2 separate studies by McGuine et al demonstrated that the use of lace-up ankle braces led to a reduction in the incidence of acute ankle injuries by 61% among 2081 high-school football players, and resulted in a significant reduction in acute ankle injuries in a study of 1460 male and female high-school basketball players, compared with the control groups.29,30

CASE

Ten days after injuring himself, the patient returns for a follow-up exam. Despite using the walking brace and crutches, he is still having significant difficulty bearing weight. He reports a sensation of instability in the right ankle. On exam, you note visible edema of the right ankle and ecchymosis over the lateral ankle, as well as moderate tenderness to palpation over the area of the ATFL and deltoid ligament. Tenderness over the medial malleolus, lateral malleolus, fifth metatarsal, and navicular is absent. Pain is reproducible with external rotation, and a Squeeze Test is positive. There is no tenderness over the proximal tibia or fibula. The patient is neurovascularly intact.

You order stress x-rays, which show widening of the medial clear space. The patient is placed in a CAM boot, instructed to continue non–weight-bearing on the ankle, and referred to a local foot and ankle surgeon for consideration of surgical fixation.

CORRESPONDENCE

John T. Nickless, MD, Division of Primary Care Sports Medicine, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, 1611 W. Harrison Street, Suite 200, Chicago, IL, 60612; [email protected].

1. Switaj PJ, Mendoza M, Kadakia AR. Acute and chronic Injuries to the syndesmosis. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:643-677.

2. Scheyerer MJ, Helfet DL, Wirth S, et al. Diagnostics in suspicion of ankle syndesmotic injury. Am J Orthop. 2011;40:192-197.

3. Smith KM, Kovacich-Smith KJ, Witt M. Evaluation and management of high ankle sprains. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2001;18:443-456.

4. Reissig J, Bitterman A, Lee S. Common foot and ankle injuries: what not to miss and how best to manage. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2017;117:98-104.

5. Williams GN, Allen EJ. Rehabilitation of syndesmotic (high) ankle sprains. Sports Health. 2010;2:460-470.

6. Williams GN, Jones MH, Amendola A. Syndesmotic ankle sprains in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1197-1207.

7. Vopat ML, Vopat BG, Lubberts B, et al. Current trends in the diagnosis and management of syndesmotic injury. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:94-103.

8. Mak MF, Gartner L, Pearce CJ. Management of syndesmosis injuries in the elite athlete. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18:195-214.

9. Waterman BR, Belmont PJ, Cameron KL, et al. Epidemiology of ankle sprain at the United States Military Academy. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:797-803.

10. Hunt KJ, George E, Harris AHS, et al. Epidemiology of syndesmosis injuries in intercollegiate football: incidence and risk factors from National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system data from 2004-2005 to 2008-2009. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:278-282.

11. Schnetzke M, Vetter SY, Beisemann N, et al. Management of syndesmotic injuries: what is the evidence? World J Orthop. 2016;7:718-725.

12. de César PC, Ávila EM, de Abreu MR. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging to physical examination for syndesmotic injury after lateral ankle sprain. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32:1110-1114.

13. Ivins D. Acute ankle sprain: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1714-1720.

14. Porter D, Rund A, Barnes AF, et al. Optimal management of ankle syndesmosis injuries. Open Access J Sports Med. 2014;5:173-182.

15. Press CM, Gupta A, Hutchinson MR. Management of ankle syndesmosis injuries in the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8:228-233.

16. Sman AD, Hiller CE, Rae K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for ankle syndesmosis injury. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:323-329.

17. Amendola A, Williams G, Foster D. Evidence-based approach to treatment of acute traumatic syndesmosis (high ankle) sprains. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2006;14:232-236.

18. Hunt KJ. Syndesmosis injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6:304-312.

19. Miller TL, Skalak T. Evaluation and treatment recommendations for acute injuries to the ankle syndesmosis without associated fracture. Sports Med. 2014;44:179-188.

20. Miller BS, Downie BK, Johnson PD, et al. Time to return to play after high ankle sprains in collegiate football players: a prediction model. Sports Health. 2012;4:504-509.

21. Wright RW, Barile RJ, Surprenant DA, et al. Ankle syndesmosis sprains in National Hockey League players. Am J Sports Med. 2016;32:1941-1945.

22. Osbahr DC, Drakos MC, O’Loughlin PF, et al. Syndesmosis and lateral ankle sprains in the National Football League. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e1378-e1384.

23. Taylor DC, Tenuta JJ, Uhorchak JM, et al. Aggressive surgical treatment and early return to sports in athletes with grade III syndesmosis sprains. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1133-1138.

24. Taylor DC, Englehardt DL, Bassett FH. Syndesmosis sprains of the ankle: the influence of heterotopic ossification. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:146-150.

25. Laver L, Carmont MR, McConkey MO, et al. Plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) as a treatment for high ankle sprain in elite athletes: a randomized control trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;23:3383-3392.

26. Kaminski TW, Hertel J, Amendola N, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: conservative management and prevention of ankle sprains in athletes. J Athl Train. 2013;48:528-545.

27. Hupperets MDW, Verhagen EALM, van Mechelen W. Effect of unsupervised home based proprioceptive training on recurrences of ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2684.

28. Tropp H, Askling C, Gillquist J. Prevention of ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:259-262.

29. McGuine TA, Brooks A, Hetzel S. The effect of lace-up ankle braces on injury rates in high school basketball players. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1840-1848.

30. McGuine TA, Hetzel S, Wilson J, et al. The effect of lace-up ankle braces on injury rates in high school football players. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:49-57.

CASE

A 19-year-old college football player presents to your outpatient family practice clinic after suffering a right ankle injury during a football game over the weekend. He reports having his right ankle planted on the turf with his foot externally rotated when an opponent fell onto his posterior right lower extremity. He reports having felt immediate pain in the area of the right ankle and requiring assistance off of the field, as he had difficulty walking. The patient was taken to the emergency department where x-rays of the right foot and ankle did not show any signs of acute fracture or dislocation. The patient was diagnosed with a lateral ankle sprain, placed in a pneumatic ankle walking brace, and given crutches.

A high ankle sprain, or distal tibiofibular syndesmotic injury, can be an elusive diagnosis and is often mistaken for the more common lateral ankle sprain. Syndesmotic injuries have been documented to occur in approximately 1% to 10% of all ankle sprains.1-3 The highest number of these injuries occurs between the ages of 18 and 34 years, and they are more frequently seen in athletes than in nonathletes, particularly those who play collision sports, such as football, ice hockey, rugby, wrestling, and lacrosse.1-9 In one study by Hunt et al,10 syndesmotic injuries accounted for 24.6% of all ankle injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football players. Incidence continues to grow as recognition of high ankle sprains increases among medical professionals.1,5 Identification of syndesmotic injury is critical, as lack of detection can lead to extensive time missed from athletic participation and chronic ankle dysfunction, including pain and instability.2,4,6,11

Back to basics: A brief anatomy review

Stability in the distal tibiofibular joint is maintained by the syndesmotic ligaments, which include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), the transverse ligament, and the interosseous ligament.3-6,8 This complex of ligaments stabilizes the fibula within the incisura of the tibia and maintains a stable ankle mortise.1,4,5,11 The deep portion of the deltoid ligament also adds stability to the syndesmosis and may be disrupted by a syndesmotic injury.2,5-7,11

Mechanisms of injury: From most common to less likely

The distal tibiofibular syndesmosis is disrupted when an injury forces apart the distal tibiofibular joint. The most commonly reported means of injury is external rotation with hyper-dorsiflexion of the ankle.1-3,5,6,11 With excessive external rotation of the forefoot, the talus is forced against the medial aspect of the fibula, resulting in separation of the distal tibia and fibula and injury to the syndesmotic ligaments.2,3,5,6 Injuries associated with external rotation are commonly seen in sports that immobilize the ankle within a rigid boot, such as skiing and ice hockey.1,2,5 Some authors have suggested that a planovalgus foot alignment may place athletes at inherent risk for an external rotation ankle injury.5,6

Syndesmotic injury may also occur with hyper-dorsiflexion, as the anterior, widest portion of the talus rotates into the ankle mortise, wedging the tibia and fibula apart.2,3,5 There have also been reports of syndesmotic injuries associated with internal rotation, plantar flexion, inversion, and eversion.3,5,11 Therefore, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for injury to the distal tibiofibular joint, regardless of the mechanism of injury.

Presentation and evaluation

Observation of the patient and visualization of the affected ankle can provide many clues. Many patients will have difficulty walking after suffering a syndesmotic injury and may require the use of an assistive device.5 The inability to bear weight after an ankle injury points to a more severe diagnosis, such as an ankle fracture or syndesmotic injury, as opposed to a simple lateral ankle sprain. Patients may report anterior ankle pain, a sensation of instability with weight bearing on the affected ankle, or have persistent symptoms despite a course of conservative treatment. Also, they can have a variable amount of edema and ecchymosis associated with their injury; a minimal extent of swelling or ecchymosis does not exclude syndesmotic injury.3

A large percentage of patients will present with a concomitant sprain of the lateral ligaments associated with lateral swelling and bruising. One study found that 91% of syndesmotic injuries involved at least 1 of the lateral collateral ligaments (anterior talofibular ligament [ATFL], calcaneofibular ligament [CFL], or posterior talofibular ligament [PTFL]).12 Patients may have pain or a sensation of instability when pushing off with the toes,5 and patients with syndesmotic injuries often have tenderness to palpation over the distal anterolateral ankle or syndesmotic ligaments.7

Continue to: A thorough examination...

A thorough examination of the ankle, including palpation of common fracture sites, is important. Employ the Ottawa Ankle Rules (see http://www.theottawarules.ca/ankle_rules) to investigate for: tenderness to palpation over the posterior 6 cm of the posterior aspects of the distal medial and lateral malleoli; tenderness over the navicular; tenderness over the base of the fifth metatarsal; and/or the inability to bear weight on the affected lower extremity immediately after injury or upon evaluation in the physician’s office. Any of these findings should raise concern for a possible fracture (see “Adult foot fractures: A guide”) and require an x-ray(s) for further evaluation.13

Perform range-of-motion and strength testing with regard to ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, abduction, adduction, inversion, and eversion. Palpate the ATFL, CFL, and PTFL for tenderness, as these structures may be involved to varying degrees in lateral ankle sprains. An anterior drawer test (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAcBEYZKcto) may be positive with injury to the ATFL. This test is performed by stabilizing the distal tibia with one hand and using the other hand to grasp the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and apply an anterior force. The test is positive if the talus translates forward, which correlates with laxity or rupture of the ATFL.13 The examiner should also palpate the Achilles tendon, peroneal tendons just posterior to the lateral malleolus, and the tibialis posterior tendon just posterior to the medial malleolus to inspect for tenderness or defects that may be signs of injury to these tendons.

An associated Weber B or C fracture? Trauma causing ankle syndesmosis injuries may be associated with Weber B or Weber C distal fibula fractures.7 Weber B fractures occur in the distal fibula at the level of the ankle joint (see FIGURE 1). These types of fractures are typically associated with external rotation injuries and are usually not associated with disruption of the interosseous membrane.

Weber C fractures are distal fibular fractures occurring above the level of the ankle joint. These fractures are also typically associated with external ankle rotation injuries and include disruption of the syndesmosis and deltoid ligament.14

Also pay special attention to the proximal fibula, as syndesmotic injuries are commonly associated with a Maisonneuve fracture, which is a proximal fibula fracture associated with external rotation forces of the ankle (see FIGURE 1).1,2,4,11,14,15 Further workup should occur in any patient with the possibility of a Weber- or Maisonneuve-type fracture.

Continue to: Multiple tests...

Multiple tests are available to investigate the possibility of a syndesmotic injury and to assess return-to-sport readiness, including the External Rotation Test, the Squeeze Test, the Crossed-Leg Test, the Dorsiflexion Compression Test, the Cotton Test, the Stabilization Test, the Fibular Translation Test, and the Single Leg Hop Test (see TABLE1-3,5,6,16,17). The External Rotation Test is noted by some authors to have the highest interobserver reliability, and is our preferred test.2 The Squeeze Test also has moderate interobserver reliability.2 There is a significant degree of variation among the sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic tests, and no single test is sufficiently reliable or accurate to diagnose a syndesmotic ankle injury. Therefore, it is recommended to use multiple physical exam maneuvers, the history and mechanism of injury, and findings on imaging studies in conjunction to make the diagnosis of a syndesmotic injury.1,16

Imaging: Which modes and when?

The initial workup should include ankle x-rays when evaluating for the possibility of a distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury. While the Ottawa Ankle Rules are helpful in providing guidance with regard to x-rays, suspicion of a syndesmotic injury mandates x-rays to determine the stability of the joint and rule out fracture. The European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy–European Foot and Ankle Associates (ESSKA-AFAS) recommend, at a minimum, obtaining anteroposterior (AP)- and mortise-view ankle x-rays to investigate the tibiofibular clear space, medial clear space, and tibiofibular overlap.7 Most physicians also include a lateral ankle x-ray.

If possible, images should be performed while the patient is bearing weight to further evaluate stability. Radiographic findings that support the diagnosis of syndesmotic injury include a tibiofibular clear space > 6 mm on AP view, medial clear space > 4 mm on mortise view, or tibiofibular overlap < 6 mm on AP view or < 1 mm on mortise view (see FIGURES 2 and 3).1,3,5,8 Additionally, if you suspect a proximal fibular fracture, obtain an x-ray series of the proximal tibia and fibula to investigate the possibility of a Maisonneuve injury.1,2,4,11

If you continue to suspect a syndesmotic injury despite normal x-rays, obtain stress x-rays, in addition to the AP and mortise views, to ensure stability. These x-rays include AP and mortise ankle views with manual external rotation of the ankle joint, which may demonstrate abnormalities not seen on standard x-rays. Bilateral imaging can also be useful to further assess when mild abnormalities vs symmetric anatomic variants are in question.1,7

If there is concern for an unstable injury, refer the patient to a foot and ankle surgeon, who may pursue magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or standing computed tomography (CT).1,2,5,7 MRI is the recommended choice for further evaluation of a syndesmotic injury, as it is proven to be accurate in evaluating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments (see FIGURES 4 and 5).18 MRI has demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detecting AITFL and PITFL injuries, as well as 93% and 100% specificity for AITFL and PITFL tears, respectively.8 A weight-bearing CT scan, particularly axial views, can also be a useful adjunct, as it is more sensitive than standard x-rays for assessing for mild diastasis. Although CT can provide an assessment of bony structures, it is not able to evaluate soft tissue structures, limiting its utility in evaluation of syndesmotic injuries.1,7

Continue to: Although not the standard of care...

Although not the standard of care, ultrasonography (US) is gaining traction as a means of investigating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments. US is inexpensive, readily available in many clinics, allows for dynamic testing, and avoids radiation exposure.7 However, US requires a skilled sonographer with experience in the ankle joint for an accurate diagnosis. If the workup with advanced imaging is inconclusive, but a high degree of suspicion remains for an unstable syndesmotic injury, consider arthroscopy to directly visualize and assess the syndesmotic structures.1,2,5,7,8

Grading the severity of the injury and pursuing appropriate Tx

Typically, the severity of a syndesmotic injury is classified as fitting into 1 of 3 categories: Grade I and II injuries are the most common, each accounting for 40% of syndesmotic injuries, while 20% of high ankle sprains are classified as Grade III.12

A Grade I injury consists of a stable syndesmotic joint without abnormal radiographic findings. There may be associated tenderness to palpation over the distal tibiofibular joint, and provocative testing may be subtle or normal. These injuries are often minor and able to be treated conservatively.

A Grade II injury is associated with a partial syndesmotic disruption, typically with partial tearing of the AITFL and interosseous ligament. These injuries may be stable or accompanied by mild instability, and provocative testing is usually positive. X-rays are typically normal with Grade II injuries, but may display subtle radiographic findings suggestive of a syndesmotic injury. Treatment of Grade II injuries is somewhat controversial and should be an individualized decision based upon the patient’s age, activity level, clinical exam, and imaging findings. Therefore, treatment of Grade II syndesmotic injuries may include a trial of conservative management or surgical intervention.

A Grade III injury represents inherent instability of the distal tibiofibular joint with complete disruption of all syndesmotic ligaments, with or without involvement of the deltoid ligament. X-rays will be positive in Grade III syndesmotic injuries because of the complete disruption of syndesmotic ligaments. All Grade III injuries require surgical intervention with a syndesmotic screw or other stabilization procedure.1,6-8,15

Continue to: A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

When conservative management is deemed appropriate for a stable syndesmotic sprain, a 3-stage rehabilitation protocol is typically utilized.

The acute phase focuses on protection, pain control, and decreasing inflammation. The patient’s ankle is often immobilized in a cast or controlled ankle movement (CAM) boot. The patient is typically allowed to bear weight in the immobilizer during this phase as long as he/she is pain-free. If pain is present with weight bearing despite immobilization, non-weight bearing is recommended. The patient is instructed to elevate the lower extremity, take anti-inflammatory medication, and ice the affected ankle. Additionally, physical therapy modalities may be utilized to help with edema and pain. Joint immobilization is typically employed for 1 to 3 weeks post-injury. In the acute phase, the patient may also work with a physical therapist or athletic trainer on passive range of motion (ROM), progressing to active ROM as tolerated.1,5,7,8,19

The patient can transition from the CAM boot to a lace-up ankle brace when he/she is able to bear full weight and can navigate stairs without pain, which typically occurs around 3 to 6 weeks post-injury.1,5,7 A pneumatic walking brace may also be used as a transition device to provide added stabilization.

In the sub-acute phase, rehabilitation may progress to increase ankle mobility, strengthening, neuromuscular control, and to allow the patient to perform activities of daily living.5-7

The advanced training phase includes continued neuromuscular control, increased strengthening, plyometrics, agility, and sports-specific drills.5 Athletes are allowed to return to full participation when they have regained full ROM, are able to perform sport-specific agility drills without pain or instability, and have near-normal strength.5-7 Some authors also advocate that a Single Leg Hop Test should be included in the physical exam, and that it should be pain free prior to allowing an athlete to return to competition.20 Both progression in physical rehabilitation and return to sport should be individualized based upon injury severity, patient functionality, and physical exam findings.

Continue to: Outcomes forecast

Outcomes forecast: Variable

The resolution of symptoms and return to competition after a syndesmotic injury is variable. In one cohort study of cadets (N = 614) at the United States Military Academy, the average time lost from a syndesmotic ankle sprain was 9.82 days (range 3-21 days).9 In a retrospective review of National Hockey League players, average time to return to competition after a syndesmotic ankle injury sprain (n = 14) was 45 days (range 6-137 days) vs 1.4 days (range 0-6 days) for lateral ankle sprains (n = 5).21 In another study, National Football League players with syndesmotic sprains (n = 36) had a mean time loss from play of 15.4 days (± 11.1 days) vs 6.5 days (± 6.5 days) of time loss from play in those with lateral ankle sprains (n = 53).22

Although there is a fair amount of variability among studies, most authors agree that the average athlete can expect to return to sport 4 to 8 weeks post-injury with conservative management.19 At least 1 study suggests that the average time to return to sport in patients with Grade III syndesmotic injuries who undergo surgical treatment with a syndesmotic screw is 41 days (range 32-48).23 The differences in return to sport may be related to severity of injury and/or type of activity.

Persistent symptoms are relatively common after conservative management of syndesmotic injuries. One case series found that 36% of patients treated conservatively had complaints of persistent mild-to-moderate ankle stiffness, 23% had mild-to-moderate pain, and 18% had mild-to-moderate ankle swelling.24 Despite these symptoms, 86% of the patients rated their ankle function as good after conservative treatment.24 In patients with persistent symptoms, other possible etiologies should be considered including neurologic injury, complex regional pain syndrome, osteochondral defect, loose body, or other sources that may be contributing to pain, swelling, or delayed recovery.

At least 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigated the utility of platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections around the injured AITFL in the setting of an acute syndesmotic injury. The study showed promising results, including quicker return to play, restabilization of the syndesmotic joint, and less residual pain;25 however, the study population was relatively small (N = 16), and the authors believed that more research is required on the benefits of PRP therapy in syndesmotic injuries before recommendations can be made.

An ounce of preventionis worth a pound of cure

Although injury is not always avoidable, there are measures that can help prevent ankle sprains and facilitate return to play after injury. As previously mentioned, athletes should be able to demonstrate the ability to run, cut, jump, and perform sport-specific activities without limitations prior to being allowed to return to sport after injury.5-7,26 Additionally, issues with biomechanics and functional deficits should be analyzed and addressed. By targeting specific strength deficits, focusing on proprioceptive awareness, and working on neuromuscular control, injury rates and recurrent injuries can be minimized. One RCT showed a 35% reduction in the recurrence rate of lateral ankle sprains with the use of an unsupervised home-based proprioceptive training program.27

Continue to: Strength training...

Strength training, proprioceptive and neuromuscular control activities, and low-risk activities such as jogging, biking, and swimming do not necessarily require the use of prophylactic bracing. However, because syndesmotic injuries are associated with recurrent ankle injuries, prophylactic bracing should be used during high-risk activities that involve agility maneuvers and jumping. Substantial evidence demonstrates that the use of ankle taping or ankle bracing decreases the incidence of ankle injuries, particularly in those who have had previous ankle injuries.26 In one study (N = 450), only 3% of athletes with a history of prior ankle injuries suffered a recurrent ankle sprain when using an ankle orthosis compared with a 17% injury rate in the control group.28

More recently, 2 separate studies by McGuine et al demonstrated that the use of lace-up ankle braces led to a reduction in the incidence of acute ankle injuries by 61% among 2081 high-school football players, and resulted in a significant reduction in acute ankle injuries in a study of 1460 male and female high-school basketball players, compared with the control groups.29,30

CASE

Ten days after injuring himself, the patient returns for a follow-up exam. Despite using the walking brace and crutches, he is still having significant difficulty bearing weight. He reports a sensation of instability in the right ankle. On exam, you note visible edema of the right ankle and ecchymosis over the lateral ankle, as well as moderate tenderness to palpation over the area of the ATFL and deltoid ligament. Tenderness over the medial malleolus, lateral malleolus, fifth metatarsal, and navicular is absent. Pain is reproducible with external rotation, and a Squeeze Test is positive. There is no tenderness over the proximal tibia or fibula. The patient is neurovascularly intact.

You order stress x-rays, which show widening of the medial clear space. The patient is placed in a CAM boot, instructed to continue non–weight-bearing on the ankle, and referred to a local foot and ankle surgeon for consideration of surgical fixation.

CORRESPONDENCE

John T. Nickless, MD, Division of Primary Care Sports Medicine, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, 1611 W. Harrison Street, Suite 200, Chicago, IL, 60612; [email protected].

CASE

A 19-year-old college football player presents to your outpatient family practice clinic after suffering a right ankle injury during a football game over the weekend. He reports having his right ankle planted on the turf with his foot externally rotated when an opponent fell onto his posterior right lower extremity. He reports having felt immediate pain in the area of the right ankle and requiring assistance off of the field, as he had difficulty walking. The patient was taken to the emergency department where x-rays of the right foot and ankle did not show any signs of acute fracture or dislocation. The patient was diagnosed with a lateral ankle sprain, placed in a pneumatic ankle walking brace, and given crutches.

A high ankle sprain, or distal tibiofibular syndesmotic injury, can be an elusive diagnosis and is often mistaken for the more common lateral ankle sprain. Syndesmotic injuries have been documented to occur in approximately 1% to 10% of all ankle sprains.1-3 The highest number of these injuries occurs between the ages of 18 and 34 years, and they are more frequently seen in athletes than in nonathletes, particularly those who play collision sports, such as football, ice hockey, rugby, wrestling, and lacrosse.1-9 In one study by Hunt et al,10 syndesmotic injuries accounted for 24.6% of all ankle injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football players. Incidence continues to grow as recognition of high ankle sprains increases among medical professionals.1,5 Identification of syndesmotic injury is critical, as lack of detection can lead to extensive time missed from athletic participation and chronic ankle dysfunction, including pain and instability.2,4,6,11

Back to basics: A brief anatomy review

Stability in the distal tibiofibular joint is maintained by the syndesmotic ligaments, which include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), the transverse ligament, and the interosseous ligament.3-6,8 This complex of ligaments stabilizes the fibula within the incisura of the tibia and maintains a stable ankle mortise.1,4,5,11 The deep portion of the deltoid ligament also adds stability to the syndesmosis and may be disrupted by a syndesmotic injury.2,5-7,11

Mechanisms of injury: From most common to less likely

The distal tibiofibular syndesmosis is disrupted when an injury forces apart the distal tibiofibular joint. The most commonly reported means of injury is external rotation with hyper-dorsiflexion of the ankle.1-3,5,6,11 With excessive external rotation of the forefoot, the talus is forced against the medial aspect of the fibula, resulting in separation of the distal tibia and fibula and injury to the syndesmotic ligaments.2,3,5,6 Injuries associated with external rotation are commonly seen in sports that immobilize the ankle within a rigid boot, such as skiing and ice hockey.1,2,5 Some authors have suggested that a planovalgus foot alignment may place athletes at inherent risk for an external rotation ankle injury.5,6

Syndesmotic injury may also occur with hyper-dorsiflexion, as the anterior, widest portion of the talus rotates into the ankle mortise, wedging the tibia and fibula apart.2,3,5 There have also been reports of syndesmotic injuries associated with internal rotation, plantar flexion, inversion, and eversion.3,5,11 Therefore, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for injury to the distal tibiofibular joint, regardless of the mechanism of injury.

Presentation and evaluation

Observation of the patient and visualization of the affected ankle can provide many clues. Many patients will have difficulty walking after suffering a syndesmotic injury and may require the use of an assistive device.5 The inability to bear weight after an ankle injury points to a more severe diagnosis, such as an ankle fracture or syndesmotic injury, as opposed to a simple lateral ankle sprain. Patients may report anterior ankle pain, a sensation of instability with weight bearing on the affected ankle, or have persistent symptoms despite a course of conservative treatment. Also, they can have a variable amount of edema and ecchymosis associated with their injury; a minimal extent of swelling or ecchymosis does not exclude syndesmotic injury.3

A large percentage of patients will present with a concomitant sprain of the lateral ligaments associated with lateral swelling and bruising. One study found that 91% of syndesmotic injuries involved at least 1 of the lateral collateral ligaments (anterior talofibular ligament [ATFL], calcaneofibular ligament [CFL], or posterior talofibular ligament [PTFL]).12 Patients may have pain or a sensation of instability when pushing off with the toes,5 and patients with syndesmotic injuries often have tenderness to palpation over the distal anterolateral ankle or syndesmotic ligaments.7

Continue to: A thorough examination...

A thorough examination of the ankle, including palpation of common fracture sites, is important. Employ the Ottawa Ankle Rules (see http://www.theottawarules.ca/ankle_rules) to investigate for: tenderness to palpation over the posterior 6 cm of the posterior aspects of the distal medial and lateral malleoli; tenderness over the navicular; tenderness over the base of the fifth metatarsal; and/or the inability to bear weight on the affected lower extremity immediately after injury or upon evaluation in the physician’s office. Any of these findings should raise concern for a possible fracture (see “Adult foot fractures: A guide”) and require an x-ray(s) for further evaluation.13

Perform range-of-motion and strength testing with regard to ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, abduction, adduction, inversion, and eversion. Palpate the ATFL, CFL, and PTFL for tenderness, as these structures may be involved to varying degrees in lateral ankle sprains. An anterior drawer test (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAcBEYZKcto) may be positive with injury to the ATFL. This test is performed by stabilizing the distal tibia with one hand and using the other hand to grasp the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and apply an anterior force. The test is positive if the talus translates forward, which correlates with laxity or rupture of the ATFL.13 The examiner should also palpate the Achilles tendon, peroneal tendons just posterior to the lateral malleolus, and the tibialis posterior tendon just posterior to the medial malleolus to inspect for tenderness or defects that may be signs of injury to these tendons.

An associated Weber B or C fracture? Trauma causing ankle syndesmosis injuries may be associated with Weber B or Weber C distal fibula fractures.7 Weber B fractures occur in the distal fibula at the level of the ankle joint (see FIGURE 1). These types of fractures are typically associated with external rotation injuries and are usually not associated with disruption of the interosseous membrane.

Weber C fractures are distal fibular fractures occurring above the level of the ankle joint. These fractures are also typically associated with external ankle rotation injuries and include disruption of the syndesmosis and deltoid ligament.14

Also pay special attention to the proximal fibula, as syndesmotic injuries are commonly associated with a Maisonneuve fracture, which is a proximal fibula fracture associated with external rotation forces of the ankle (see FIGURE 1).1,2,4,11,14,15 Further workup should occur in any patient with the possibility of a Weber- or Maisonneuve-type fracture.

Continue to: Multiple tests...

Multiple tests are available to investigate the possibility of a syndesmotic injury and to assess return-to-sport readiness, including the External Rotation Test, the Squeeze Test, the Crossed-Leg Test, the Dorsiflexion Compression Test, the Cotton Test, the Stabilization Test, the Fibular Translation Test, and the Single Leg Hop Test (see TABLE1-3,5,6,16,17). The External Rotation Test is noted by some authors to have the highest interobserver reliability, and is our preferred test.2 The Squeeze Test also has moderate interobserver reliability.2 There is a significant degree of variation among the sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic tests, and no single test is sufficiently reliable or accurate to diagnose a syndesmotic ankle injury. Therefore, it is recommended to use multiple physical exam maneuvers, the history and mechanism of injury, and findings on imaging studies in conjunction to make the diagnosis of a syndesmotic injury.1,16

Imaging: Which modes and when?

The initial workup should include ankle x-rays when evaluating for the possibility of a distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury. While the Ottawa Ankle Rules are helpful in providing guidance with regard to x-rays, suspicion of a syndesmotic injury mandates x-rays to determine the stability of the joint and rule out fracture. The European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy–European Foot and Ankle Associates (ESSKA-AFAS) recommend, at a minimum, obtaining anteroposterior (AP)- and mortise-view ankle x-rays to investigate the tibiofibular clear space, medial clear space, and tibiofibular overlap.7 Most physicians also include a lateral ankle x-ray.

If possible, images should be performed while the patient is bearing weight to further evaluate stability. Radiographic findings that support the diagnosis of syndesmotic injury include a tibiofibular clear space > 6 mm on AP view, medial clear space > 4 mm on mortise view, or tibiofibular overlap < 6 mm on AP view or < 1 mm on mortise view (see FIGURES 2 and 3).1,3,5,8 Additionally, if you suspect a proximal fibular fracture, obtain an x-ray series of the proximal tibia and fibula to investigate the possibility of a Maisonneuve injury.1,2,4,11

If you continue to suspect a syndesmotic injury despite normal x-rays, obtain stress x-rays, in addition to the AP and mortise views, to ensure stability. These x-rays include AP and mortise ankle views with manual external rotation of the ankle joint, which may demonstrate abnormalities not seen on standard x-rays. Bilateral imaging can also be useful to further assess when mild abnormalities vs symmetric anatomic variants are in question.1,7

If there is concern for an unstable injury, refer the patient to a foot and ankle surgeon, who may pursue magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or standing computed tomography (CT).1,2,5,7 MRI is the recommended choice for further evaluation of a syndesmotic injury, as it is proven to be accurate in evaluating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments (see FIGURES 4 and 5).18 MRI has demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detecting AITFL and PITFL injuries, as well as 93% and 100% specificity for AITFL and PITFL tears, respectively.8 A weight-bearing CT scan, particularly axial views, can also be a useful adjunct, as it is more sensitive than standard x-rays for assessing for mild diastasis. Although CT can provide an assessment of bony structures, it is not able to evaluate soft tissue structures, limiting its utility in evaluation of syndesmotic injuries.1,7

Continue to: Although not the standard of care...

Although not the standard of care, ultrasonography (US) is gaining traction as a means of investigating the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments. US is inexpensive, readily available in many clinics, allows for dynamic testing, and avoids radiation exposure.7 However, US requires a skilled sonographer with experience in the ankle joint for an accurate diagnosis. If the workup with advanced imaging is inconclusive, but a high degree of suspicion remains for an unstable syndesmotic injury, consider arthroscopy to directly visualize and assess the syndesmotic structures.1,2,5,7,8

Grading the severity of the injury and pursuing appropriate Tx

Typically, the severity of a syndesmotic injury is classified as fitting into 1 of 3 categories: Grade I and II injuries are the most common, each accounting for 40% of syndesmotic injuries, while 20% of high ankle sprains are classified as Grade III.12

A Grade I injury consists of a stable syndesmotic joint without abnormal radiographic findings. There may be associated tenderness to palpation over the distal tibiofibular joint, and provocative testing may be subtle or normal. These injuries are often minor and able to be treated conservatively.

A Grade II injury is associated with a partial syndesmotic disruption, typically with partial tearing of the AITFL and interosseous ligament. These injuries may be stable or accompanied by mild instability, and provocative testing is usually positive. X-rays are typically normal with Grade II injuries, but may display subtle radiographic findings suggestive of a syndesmotic injury. Treatment of Grade II injuries is somewhat controversial and should be an individualized decision based upon the patient’s age, activity level, clinical exam, and imaging findings. Therefore, treatment of Grade II syndesmotic injuries may include a trial of conservative management or surgical intervention.

A Grade III injury represents inherent instability of the distal tibiofibular joint with complete disruption of all syndesmotic ligaments, with or without involvement of the deltoid ligament. X-rays will be positive in Grade III syndesmotic injuries because of the complete disruption of syndesmotic ligaments. All Grade III injuries require surgical intervention with a syndesmotic screw or other stabilization procedure.1,6-8,15

Continue to: A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

A 3-stage rehabilitation protocol

When conservative management is deemed appropriate for a stable syndesmotic sprain, a 3-stage rehabilitation protocol is typically utilized.