User login

In pain treatment, racial bias common among physician trainees

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Alvogen issues recall for mislabeled fentanyl patches

Alvogen has issued a voluntary recall of two lots of its Fentanyl Transdermal System 12-mcg/h transdermal patches because of a product mislabeling, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall was issued because a small number of cartons labeled as containing 12-mcg/h patches contained 50-mcg/h patches. The 50-mcg/h patches were labeled as such within the package.

Application of a 50-mcg/h patch instead of a 12-mcg/h patch could result in serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression. Groups at potential risk for such adverse events include first-time users of the patch, children, and the elderly. No reports of serious adverse events have yet been reported.

“Pharmacies are requested not to dispense any product subject to this recall,” the FDA said in a press release. Patients who “have product subject to this recall should immediately remove any patch currently in use and contact their health care provider. Patients with unused product should return it to point of purchase for replacement.”

Find more information on the recall at the FDA website.

Alvogen has issued a voluntary recall of two lots of its Fentanyl Transdermal System 12-mcg/h transdermal patches because of a product mislabeling, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall was issued because a small number of cartons labeled as containing 12-mcg/h patches contained 50-mcg/h patches. The 50-mcg/h patches were labeled as such within the package.

Application of a 50-mcg/h patch instead of a 12-mcg/h patch could result in serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression. Groups at potential risk for such adverse events include first-time users of the patch, children, and the elderly. No reports of serious adverse events have yet been reported.

“Pharmacies are requested not to dispense any product subject to this recall,” the FDA said in a press release. Patients who “have product subject to this recall should immediately remove any patch currently in use and contact their health care provider. Patients with unused product should return it to point of purchase for replacement.”

Find more information on the recall at the FDA website.

Alvogen has issued a voluntary recall of two lots of its Fentanyl Transdermal System 12-mcg/h transdermal patches because of a product mislabeling, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall was issued because a small number of cartons labeled as containing 12-mcg/h patches contained 50-mcg/h patches. The 50-mcg/h patches were labeled as such within the package.

Application of a 50-mcg/h patch instead of a 12-mcg/h patch could result in serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression. Groups at potential risk for such adverse events include first-time users of the patch, children, and the elderly. No reports of serious adverse events have yet been reported.

“Pharmacies are requested not to dispense any product subject to this recall,” the FDA said in a press release. Patients who “have product subject to this recall should immediately remove any patch currently in use and contact their health care provider. Patients with unused product should return it to point of purchase for replacement.”

Find more information on the recall at the FDA website.

What is medical marijuana actually useful for?

PHILADELPHIA – , some insights into adverse effects, and “a lot of the Wild West,” Ellie Grossman, MD, MPH, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The opioid-sparing effects of medical marijuana have been highlighted in recent reports suggesting that cannabis users may use less opioids, and that states with medical marijuana laws have seen drops in opioid overdose mortality, Dr. Grossman said.

“That’s kind of a story on pain and cannabinoids, and that’s really the biggest story there is in terms of medical evidence and effectiveness for this agent,” said Dr. Grossman, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and Primary Care Lead for Behavioral Health Integration, Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass.

However, being the top story in medical marijuana may not be a very high bar in 2019, given current issues with research in this area, including inconsistencies in medical marijuana formulations, relatively small numbers of patients enrolled in studies, and meta-analyses that have produced equivocal results.

“Unfortunately, this is an area where there’s a lot of, shall I say, ‘squishiness’ in the data, through no fault of the researchers involved – it’s just an area that’s really hard to study,” Dr. Goodman said in her update on medical marijuana use at the meeting.

Most studies of cannabinoids for chronic pain have compared these agents to placebo, rather than the long list of other medications that might be used to treat pain, Dr. Grossman said.

There are several meta-analyses available, including a recently published Cochrane review in which authors concluded that, for neuropathic pain, the potential benefits of cannabis-based medicines may outweigh their potential harms.

“The upshot here is that there may be some evidence for neuropathic pain, but the evidence is generally of poor quality and kind of mixed,” said Dr. Grossman.

State-level medical cannabis laws were linked to significantly lower opioid overdose mortality rates in a 2014 study (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[10]:1668-73). In more recent studies, states with medical cannabis laws were found to have lower Medicare Part D opioid-prescribing rates, and in another study, legalization of medical marijuana was linked to lower rates of chronic and high-risk opioid use.

“It certainly seems like maybe we as prescribers are prescribing [fewer] opioids if there’s medical cannabis around,” Dr. Grossman said. “What this means for our patients in the short term and long term, we don’t totally know. But clearly, fewer opioid overdoses is a way better thing than more, so there could be something here.”

The cannabinoids approved by the Food and Drug Administration include nabilone (Cesamet) and dronabinol (Marinol), both synthetic cannabinoids indicated for cancer chemotherapy–related nausea and vomiting, along with cannabidiol (Epidiolex), just approved in June 2018 for treatment of some rare pediatric refractory epilepsy syndromes, Dr. Grossman said.

For chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, evidence suggests oral cannabinoids are more effective than placebo, but there’s mixed evidence as to whether they are better than other antiemetics, Dr. Grossman said, while in terms of spasticity related to multiple sclerosis, research has shown small improvements in patient-reported symptoms.

Long-term adverse event data specific to medical marijuana are scant, with much of the evidence coming from studies of recreational marijuana users, Dr. Grossman said.

Those long-term effects include increased risk of pulmonary effects such as cough, wheeze, and phlegm that improve with discontinuation; case reports of unintentional pediatric ingestions; and lower neonatal birth weight, which should be discussed with women of reproductive age who are using or considering medical marijuana, Dr. Grossman said.

Motor vehicle accidents, development of psychiatric symptoms, and psychosis relapse also have been linked to use, she said.

Some real-world adverse event data specific to medical marijuana data are available through the Minnesota medical cannabis program. They found 16% of surveyed users reported an adverse event within the first 4 months, including dry mouth, fatigue, mental clouding, and drowsiness, Dr. Grossman told attendees.

Dr. Grossman reported that she has no relationship with entities producing, marketing, reselling, or distributing health care goods or services consumed by, or used on, patients.

SOURCE: Grossman E. ACP 2019, Presentation MTP 010.

PHILADELPHIA – , some insights into adverse effects, and “a lot of the Wild West,” Ellie Grossman, MD, MPH, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The opioid-sparing effects of medical marijuana have been highlighted in recent reports suggesting that cannabis users may use less opioids, and that states with medical marijuana laws have seen drops in opioid overdose mortality, Dr. Grossman said.

“That’s kind of a story on pain and cannabinoids, and that’s really the biggest story there is in terms of medical evidence and effectiveness for this agent,” said Dr. Grossman, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and Primary Care Lead for Behavioral Health Integration, Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass.

However, being the top story in medical marijuana may not be a very high bar in 2019, given current issues with research in this area, including inconsistencies in medical marijuana formulations, relatively small numbers of patients enrolled in studies, and meta-analyses that have produced equivocal results.

“Unfortunately, this is an area where there’s a lot of, shall I say, ‘squishiness’ in the data, through no fault of the researchers involved – it’s just an area that’s really hard to study,” Dr. Goodman said in her update on medical marijuana use at the meeting.

Most studies of cannabinoids for chronic pain have compared these agents to placebo, rather than the long list of other medications that might be used to treat pain, Dr. Grossman said.

There are several meta-analyses available, including a recently published Cochrane review in which authors concluded that, for neuropathic pain, the potential benefits of cannabis-based medicines may outweigh their potential harms.

“The upshot here is that there may be some evidence for neuropathic pain, but the evidence is generally of poor quality and kind of mixed,” said Dr. Grossman.

State-level medical cannabis laws were linked to significantly lower opioid overdose mortality rates in a 2014 study (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[10]:1668-73). In more recent studies, states with medical cannabis laws were found to have lower Medicare Part D opioid-prescribing rates, and in another study, legalization of medical marijuana was linked to lower rates of chronic and high-risk opioid use.

“It certainly seems like maybe we as prescribers are prescribing [fewer] opioids if there’s medical cannabis around,” Dr. Grossman said. “What this means for our patients in the short term and long term, we don’t totally know. But clearly, fewer opioid overdoses is a way better thing than more, so there could be something here.”

The cannabinoids approved by the Food and Drug Administration include nabilone (Cesamet) and dronabinol (Marinol), both synthetic cannabinoids indicated for cancer chemotherapy–related nausea and vomiting, along with cannabidiol (Epidiolex), just approved in June 2018 for treatment of some rare pediatric refractory epilepsy syndromes, Dr. Grossman said.

For chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, evidence suggests oral cannabinoids are more effective than placebo, but there’s mixed evidence as to whether they are better than other antiemetics, Dr. Grossman said, while in terms of spasticity related to multiple sclerosis, research has shown small improvements in patient-reported symptoms.

Long-term adverse event data specific to medical marijuana are scant, with much of the evidence coming from studies of recreational marijuana users, Dr. Grossman said.

Those long-term effects include increased risk of pulmonary effects such as cough, wheeze, and phlegm that improve with discontinuation; case reports of unintentional pediatric ingestions; and lower neonatal birth weight, which should be discussed with women of reproductive age who are using or considering medical marijuana, Dr. Grossman said.

Motor vehicle accidents, development of psychiatric symptoms, and psychosis relapse also have been linked to use, she said.

Some real-world adverse event data specific to medical marijuana data are available through the Minnesota medical cannabis program. They found 16% of surveyed users reported an adverse event within the first 4 months, including dry mouth, fatigue, mental clouding, and drowsiness, Dr. Grossman told attendees.

Dr. Grossman reported that she has no relationship with entities producing, marketing, reselling, or distributing health care goods or services consumed by, or used on, patients.

SOURCE: Grossman E. ACP 2019, Presentation MTP 010.

PHILADELPHIA – , some insights into adverse effects, and “a lot of the Wild West,” Ellie Grossman, MD, MPH, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The opioid-sparing effects of medical marijuana have been highlighted in recent reports suggesting that cannabis users may use less opioids, and that states with medical marijuana laws have seen drops in opioid overdose mortality, Dr. Grossman said.

“That’s kind of a story on pain and cannabinoids, and that’s really the biggest story there is in terms of medical evidence and effectiveness for this agent,” said Dr. Grossman, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and Primary Care Lead for Behavioral Health Integration, Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass.

However, being the top story in medical marijuana may not be a very high bar in 2019, given current issues with research in this area, including inconsistencies in medical marijuana formulations, relatively small numbers of patients enrolled in studies, and meta-analyses that have produced equivocal results.

“Unfortunately, this is an area where there’s a lot of, shall I say, ‘squishiness’ in the data, through no fault of the researchers involved – it’s just an area that’s really hard to study,” Dr. Goodman said in her update on medical marijuana use at the meeting.

Most studies of cannabinoids for chronic pain have compared these agents to placebo, rather than the long list of other medications that might be used to treat pain, Dr. Grossman said.

There are several meta-analyses available, including a recently published Cochrane review in which authors concluded that, for neuropathic pain, the potential benefits of cannabis-based medicines may outweigh their potential harms.

“The upshot here is that there may be some evidence for neuropathic pain, but the evidence is generally of poor quality and kind of mixed,” said Dr. Grossman.

State-level medical cannabis laws were linked to significantly lower opioid overdose mortality rates in a 2014 study (JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174[10]:1668-73). In more recent studies, states with medical cannabis laws were found to have lower Medicare Part D opioid-prescribing rates, and in another study, legalization of medical marijuana was linked to lower rates of chronic and high-risk opioid use.

“It certainly seems like maybe we as prescribers are prescribing [fewer] opioids if there’s medical cannabis around,” Dr. Grossman said. “What this means for our patients in the short term and long term, we don’t totally know. But clearly, fewer opioid overdoses is a way better thing than more, so there could be something here.”

The cannabinoids approved by the Food and Drug Administration include nabilone (Cesamet) and dronabinol (Marinol), both synthetic cannabinoids indicated for cancer chemotherapy–related nausea and vomiting, along with cannabidiol (Epidiolex), just approved in June 2018 for treatment of some rare pediatric refractory epilepsy syndromes, Dr. Grossman said.

For chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, evidence suggests oral cannabinoids are more effective than placebo, but there’s mixed evidence as to whether they are better than other antiemetics, Dr. Grossman said, while in terms of spasticity related to multiple sclerosis, research has shown small improvements in patient-reported symptoms.

Long-term adverse event data specific to medical marijuana are scant, with much of the evidence coming from studies of recreational marijuana users, Dr. Grossman said.

Those long-term effects include increased risk of pulmonary effects such as cough, wheeze, and phlegm that improve with discontinuation; case reports of unintentional pediatric ingestions; and lower neonatal birth weight, which should be discussed with women of reproductive age who are using or considering medical marijuana, Dr. Grossman said.

Motor vehicle accidents, development of psychiatric symptoms, and psychosis relapse also have been linked to use, she said.

Some real-world adverse event data specific to medical marijuana data are available through the Minnesota medical cannabis program. They found 16% of surveyed users reported an adverse event within the first 4 months, including dry mouth, fatigue, mental clouding, and drowsiness, Dr. Grossman told attendees.

Dr. Grossman reported that she has no relationship with entities producing, marketing, reselling, or distributing health care goods or services consumed by, or used on, patients.

SOURCE: Grossman E. ACP 2019, Presentation MTP 010.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

No clear winner for treating neuropathic pain

PHILADELPHIA – Nearly 7%-10% of the general population experiences neuropathic pain, but studies on treatments have not found a clear winner for reducing this “burning or electriclike pain,” explained Raymond Price, MD, during a presentation.

“It isn’t that exciting,” said Dr. Price, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in reference to his review of level 1-2 evidence for treatment of neuropathic pain that was presented in a study published in JAMA (2015 Nov 24;314[20]:2172-81). a few years ago. “On a scale of 1 to 10, you can reduce their pain scale by 1-2 points more than placebo,” he told his audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

There are very limited head-to-head data as to which one is actually better,” he explained.

Given the absence of robust head-to-head trial data, Dr. Price tends to start a lot of patients on old, cheap medications like nortriptyline.

While there aren’t many head-to-head trials to guide treatment choice, the results of one prospective, randomized, open-label study of 333 patients with cryptogenic sensory polyneuropathy was presented by Barohn and colleagues at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, he said. In that study, somewhat higher efficacy rates were seen with duloxetine, a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, and nortriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, compared with pregabalin, Dr. Price noted. Duloxetine and nortriptyline also had slightly better tolerability, as evidenced by a lower quit rate, compared with pregabalin, he added.

There was also a systematic review and meta-analysis (Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb; 14[2]:162-73) conducted that determined the number needed to treat for neuropathic pain treatments, Dr. Price noted. In that paper, tricyclic antidepressants had a number needed to treat of 3.6, comparing favorably to 7.7 for pregabalin, 7.2 for gabapentin, and 6.4 for serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, mainly including duloxetine, said Dr. Price.

Regardless of the cause of neuropathic pain, the same general approach to treatment is taken, though most of the evidence comes from studies of patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia, he added.

For these patients, an adequate trial of a neuropathic pain treatment should be 6-12 weeks, reflecting the length of the intervention needed to demonstrate the efficacy of these agents, he said.

If that first drug doesn’t work, another can be tried, or multiple drugs can be tried together to see if the patient’s condition improves, he said.

Dr. Price reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Price R Internal Medicine 2019, Presentation MSFM 002.

PHILADELPHIA – Nearly 7%-10% of the general population experiences neuropathic pain, but studies on treatments have not found a clear winner for reducing this “burning or electriclike pain,” explained Raymond Price, MD, during a presentation.

“It isn’t that exciting,” said Dr. Price, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in reference to his review of level 1-2 evidence for treatment of neuropathic pain that was presented in a study published in JAMA (2015 Nov 24;314[20]:2172-81). a few years ago. “On a scale of 1 to 10, you can reduce their pain scale by 1-2 points more than placebo,” he told his audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

There are very limited head-to-head data as to which one is actually better,” he explained.

Given the absence of robust head-to-head trial data, Dr. Price tends to start a lot of patients on old, cheap medications like nortriptyline.

While there aren’t many head-to-head trials to guide treatment choice, the results of one prospective, randomized, open-label study of 333 patients with cryptogenic sensory polyneuropathy was presented by Barohn and colleagues at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, he said. In that study, somewhat higher efficacy rates were seen with duloxetine, a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, and nortriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, compared with pregabalin, Dr. Price noted. Duloxetine and nortriptyline also had slightly better tolerability, as evidenced by a lower quit rate, compared with pregabalin, he added.

There was also a systematic review and meta-analysis (Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb; 14[2]:162-73) conducted that determined the number needed to treat for neuropathic pain treatments, Dr. Price noted. In that paper, tricyclic antidepressants had a number needed to treat of 3.6, comparing favorably to 7.7 for pregabalin, 7.2 for gabapentin, and 6.4 for serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, mainly including duloxetine, said Dr. Price.

Regardless of the cause of neuropathic pain, the same general approach to treatment is taken, though most of the evidence comes from studies of patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia, he added.

For these patients, an adequate trial of a neuropathic pain treatment should be 6-12 weeks, reflecting the length of the intervention needed to demonstrate the efficacy of these agents, he said.

If that first drug doesn’t work, another can be tried, or multiple drugs can be tried together to see if the patient’s condition improves, he said.

Dr. Price reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Price R Internal Medicine 2019, Presentation MSFM 002.

PHILADELPHIA – Nearly 7%-10% of the general population experiences neuropathic pain, but studies on treatments have not found a clear winner for reducing this “burning or electriclike pain,” explained Raymond Price, MD, during a presentation.

“It isn’t that exciting,” said Dr. Price, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in reference to his review of level 1-2 evidence for treatment of neuropathic pain that was presented in a study published in JAMA (2015 Nov 24;314[20]:2172-81). a few years ago. “On a scale of 1 to 10, you can reduce their pain scale by 1-2 points more than placebo,” he told his audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

There are very limited head-to-head data as to which one is actually better,” he explained.

Given the absence of robust head-to-head trial data, Dr. Price tends to start a lot of patients on old, cheap medications like nortriptyline.

While there aren’t many head-to-head trials to guide treatment choice, the results of one prospective, randomized, open-label study of 333 patients with cryptogenic sensory polyneuropathy was presented by Barohn and colleagues at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, he said. In that study, somewhat higher efficacy rates were seen with duloxetine, a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, and nortriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, compared with pregabalin, Dr. Price noted. Duloxetine and nortriptyline also had slightly better tolerability, as evidenced by a lower quit rate, compared with pregabalin, he added.

There was also a systematic review and meta-analysis (Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb; 14[2]:162-73) conducted that determined the number needed to treat for neuropathic pain treatments, Dr. Price noted. In that paper, tricyclic antidepressants had a number needed to treat of 3.6, comparing favorably to 7.7 for pregabalin, 7.2 for gabapentin, and 6.4 for serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, mainly including duloxetine, said Dr. Price.

Regardless of the cause of neuropathic pain, the same general approach to treatment is taken, though most of the evidence comes from studies of patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia, he added.

For these patients, an adequate trial of a neuropathic pain treatment should be 6-12 weeks, reflecting the length of the intervention needed to demonstrate the efficacy of these agents, he said.

If that first drug doesn’t work, another can be tried, or multiple drugs can be tried together to see if the patient’s condition improves, he said.

Dr. Price reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Price R Internal Medicine 2019, Presentation MSFM 002.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

‘Fibro-fog’ confirmed with objective ambulatory testing

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with fibromyalgia had worse cognitive functioning than did a control group without fibromyalgia, according to both subjective and objective ambulatory measures.

For study participants with fibromyalgia, aggregate self-reported cognitive function over an 8-day period was poorer than for their matched controls without fibromyalgia. Objective measures of working memory, including mean and maximum error scores on a dot memory test, also were worse for the fibromyalgia group (P less than .001 for all).

Objective measures of processing speed also were slower for those with fibromyalgia, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

These findings are “generally consistent with findings from lab-based studies of people living with [fibromyalgia], Anna Kratz, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in a poster at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. by using smartphone-based capture of momentary subjective and objective cognitive functioning.

In a study of 50 adults with fibromyalgia and 50 matched controls, Dr. Kratz and her colleagues at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, had participants complete baseline self-report and objective measures of cognitive functioning in an in-person laboratory session. Then, participants were sent home with a wrist accelerometer and a smartphone; apps on the smartphone administered objective cognitive tests as well as subjective questions about cognitive function.

Both the subjective and objective portions of the ambulatory study were completed five times daily (on waking, and on a “quasi-random” schedule throughout the day), for at least 8 days. Day 1 was considered a “training day,” and data from that day were excluded from analysis.

To assess subjective cognitive function, patients were asked to give a momentary assessment of how slow, and how foggy, their thinking was, using a 0-100 scale. These two questions were drawn from the PROMIS Applied Cognition – General Concerns item bank. Objective measures included processing speed, captured by a 16-trial exercise of matching symbol pairs. Also, working memory was tested by completing four trials of remembering the placement of three dots in a 5x5 dot matrix.

Among the participants, 88% were female. The mean age was 45 years, and about 80% of the subjects were white. Fibromyalgia patients had more pain than did their matched controls and had poorer baseline performance on four neurocognitive tasks drawn from the National Institutes of Health Toolbox. For a flanker test, a list sorting task, a dimensional change card sort test, and a pattern comparison task, mean scores for participants with fibromyalgia ranged from 39.08 to 49.76; for the control group, mean scores ranged from 43.78 to 57.36 (P less than .05 for all).

Some people with fibromyalgia report subjective diurnal variation in cognitive function, so Dr. Kratz and her coauthors were interested in tracking performance on the ambulatory cognitive tasks over the course of the day. “Diurnal patterns and associations between objective/subjective functioning were similar across the groups,” said the authors, with no hallmark diurnal pattern for the participants with fibromyalgia. Generally, participants in both groups had the highest subjective and objective levels of performance in the morning, a dip at the first reporting time, and a gradual recovery to a level somewhat below the first morning test point by the end of the day.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues found that in both groups, “significant associations were observed between within-person momentary changes in subjective cognitive functioning and processing speed.” This association did not hold true for working memory, however.

The findings were overall generally consistent with lab-based testing of cognitive function in individuals living with fibromyalgia, the authors said.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues reported no outside sources of funding, and reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kratz A et al. APS 2019, Poster 117.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with fibromyalgia had worse cognitive functioning than did a control group without fibromyalgia, according to both subjective and objective ambulatory measures.

For study participants with fibromyalgia, aggregate self-reported cognitive function over an 8-day period was poorer than for their matched controls without fibromyalgia. Objective measures of working memory, including mean and maximum error scores on a dot memory test, also were worse for the fibromyalgia group (P less than .001 for all).

Objective measures of processing speed also were slower for those with fibromyalgia, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

These findings are “generally consistent with findings from lab-based studies of people living with [fibromyalgia], Anna Kratz, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in a poster at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. by using smartphone-based capture of momentary subjective and objective cognitive functioning.

In a study of 50 adults with fibromyalgia and 50 matched controls, Dr. Kratz and her colleagues at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, had participants complete baseline self-report and objective measures of cognitive functioning in an in-person laboratory session. Then, participants were sent home with a wrist accelerometer and a smartphone; apps on the smartphone administered objective cognitive tests as well as subjective questions about cognitive function.

Both the subjective and objective portions of the ambulatory study were completed five times daily (on waking, and on a “quasi-random” schedule throughout the day), for at least 8 days. Day 1 was considered a “training day,” and data from that day were excluded from analysis.

To assess subjective cognitive function, patients were asked to give a momentary assessment of how slow, and how foggy, their thinking was, using a 0-100 scale. These two questions were drawn from the PROMIS Applied Cognition – General Concerns item bank. Objective measures included processing speed, captured by a 16-trial exercise of matching symbol pairs. Also, working memory was tested by completing four trials of remembering the placement of three dots in a 5x5 dot matrix.

Among the participants, 88% were female. The mean age was 45 years, and about 80% of the subjects were white. Fibromyalgia patients had more pain than did their matched controls and had poorer baseline performance on four neurocognitive tasks drawn from the National Institutes of Health Toolbox. For a flanker test, a list sorting task, a dimensional change card sort test, and a pattern comparison task, mean scores for participants with fibromyalgia ranged from 39.08 to 49.76; for the control group, mean scores ranged from 43.78 to 57.36 (P less than .05 for all).

Some people with fibromyalgia report subjective diurnal variation in cognitive function, so Dr. Kratz and her coauthors were interested in tracking performance on the ambulatory cognitive tasks over the course of the day. “Diurnal patterns and associations between objective/subjective functioning were similar across the groups,” said the authors, with no hallmark diurnal pattern for the participants with fibromyalgia. Generally, participants in both groups had the highest subjective and objective levels of performance in the morning, a dip at the first reporting time, and a gradual recovery to a level somewhat below the first morning test point by the end of the day.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues found that in both groups, “significant associations were observed between within-person momentary changes in subjective cognitive functioning and processing speed.” This association did not hold true for working memory, however.

The findings were overall generally consistent with lab-based testing of cognitive function in individuals living with fibromyalgia, the authors said.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues reported no outside sources of funding, and reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kratz A et al. APS 2019, Poster 117.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with fibromyalgia had worse cognitive functioning than did a control group without fibromyalgia, according to both subjective and objective ambulatory measures.

For study participants with fibromyalgia, aggregate self-reported cognitive function over an 8-day period was poorer than for their matched controls without fibromyalgia. Objective measures of working memory, including mean and maximum error scores on a dot memory test, also were worse for the fibromyalgia group (P less than .001 for all).

Objective measures of processing speed also were slower for those with fibromyalgia, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

These findings are “generally consistent with findings from lab-based studies of people living with [fibromyalgia], Anna Kratz, PhD, and her coauthors wrote in a poster at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. by using smartphone-based capture of momentary subjective and objective cognitive functioning.

In a study of 50 adults with fibromyalgia and 50 matched controls, Dr. Kratz and her colleagues at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, had participants complete baseline self-report and objective measures of cognitive functioning in an in-person laboratory session. Then, participants were sent home with a wrist accelerometer and a smartphone; apps on the smartphone administered objective cognitive tests as well as subjective questions about cognitive function.

Both the subjective and objective portions of the ambulatory study were completed five times daily (on waking, and on a “quasi-random” schedule throughout the day), for at least 8 days. Day 1 was considered a “training day,” and data from that day were excluded from analysis.

To assess subjective cognitive function, patients were asked to give a momentary assessment of how slow, and how foggy, their thinking was, using a 0-100 scale. These two questions were drawn from the PROMIS Applied Cognition – General Concerns item bank. Objective measures included processing speed, captured by a 16-trial exercise of matching symbol pairs. Also, working memory was tested by completing four trials of remembering the placement of three dots in a 5x5 dot matrix.

Among the participants, 88% were female. The mean age was 45 years, and about 80% of the subjects were white. Fibromyalgia patients had more pain than did their matched controls and had poorer baseline performance on four neurocognitive tasks drawn from the National Institutes of Health Toolbox. For a flanker test, a list sorting task, a dimensional change card sort test, and a pattern comparison task, mean scores for participants with fibromyalgia ranged from 39.08 to 49.76; for the control group, mean scores ranged from 43.78 to 57.36 (P less than .05 for all).

Some people with fibromyalgia report subjective diurnal variation in cognitive function, so Dr. Kratz and her coauthors were interested in tracking performance on the ambulatory cognitive tasks over the course of the day. “Diurnal patterns and associations between objective/subjective functioning were similar across the groups,” said the authors, with no hallmark diurnal pattern for the participants with fibromyalgia. Generally, participants in both groups had the highest subjective and objective levels of performance in the morning, a dip at the first reporting time, and a gradual recovery to a level somewhat below the first morning test point by the end of the day.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues found that in both groups, “significant associations were observed between within-person momentary changes in subjective cognitive functioning and processing speed.” This association did not hold true for working memory, however.

The findings were overall generally consistent with lab-based testing of cognitive function in individuals living with fibromyalgia, the authors said.

Dr. Kratz and her colleagues reported no outside sources of funding, and reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kratz A et al. APS 2019, Poster 117.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

FDA to expand opioid labeling with instructions on proper tapering

The Food and Drug Administration is making changes to opioid analgesic labeling to give better information to clinicians on how to properly taper patients dependent on opioid use, according to Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

, such as withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, and suicide. Both the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer guidelines on how to properly taper opioids, Dr. Throckmorton said, but more needs to be done to ensure that patients are being provided with the correct advice and care.

The changes to the labels will include expanded information to health care clinicians and are intended to be used when both the clinician and patient have agreed to reduce the opioid dosage. When this is discussed, factors that should be considered include the dose of the drug, the duration of treatment, the type of pain being treated, and the physical and psychological attributes of the patient.

Other actions the FDA is pursuing to combat opioid use disorder include working with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on guidelines for the proper opioid analgesic prescribing for acute pain resulting from specific conditions or procedures, and advancing policies that make immediate-release opioid formulations available in fixed-quantity packaging for 1 or 2 days.

“The FDA remains committed to addressing the opioid crisis on all fronts, with a significant focus on decreasing unnecessary exposure to opioids and preventing new addiction; supporting the treatment of those with opioid use disorder; fostering the development of novel pain treatment therapies and opioids more resistant to abuse and misuse; and taking action against those involved in the illegal importation and sale of opioids,” Dr. Throckmorton said.

Find the full statement by Dr. Throckmorton on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration is making changes to opioid analgesic labeling to give better information to clinicians on how to properly taper patients dependent on opioid use, according to Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

, such as withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, and suicide. Both the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer guidelines on how to properly taper opioids, Dr. Throckmorton said, but more needs to be done to ensure that patients are being provided with the correct advice and care.

The changes to the labels will include expanded information to health care clinicians and are intended to be used when both the clinician and patient have agreed to reduce the opioid dosage. When this is discussed, factors that should be considered include the dose of the drug, the duration of treatment, the type of pain being treated, and the physical and psychological attributes of the patient.

Other actions the FDA is pursuing to combat opioid use disorder include working with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on guidelines for the proper opioid analgesic prescribing for acute pain resulting from specific conditions or procedures, and advancing policies that make immediate-release opioid formulations available in fixed-quantity packaging for 1 or 2 days.

“The FDA remains committed to addressing the opioid crisis on all fronts, with a significant focus on decreasing unnecessary exposure to opioids and preventing new addiction; supporting the treatment of those with opioid use disorder; fostering the development of novel pain treatment therapies and opioids more resistant to abuse and misuse; and taking action against those involved in the illegal importation and sale of opioids,” Dr. Throckmorton said.

Find the full statement by Dr. Throckmorton on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration is making changes to opioid analgesic labeling to give better information to clinicians on how to properly taper patients dependent on opioid use, according to Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

, such as withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, and suicide. Both the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer guidelines on how to properly taper opioids, Dr. Throckmorton said, but more needs to be done to ensure that patients are being provided with the correct advice and care.

The changes to the labels will include expanded information to health care clinicians and are intended to be used when both the clinician and patient have agreed to reduce the opioid dosage. When this is discussed, factors that should be considered include the dose of the drug, the duration of treatment, the type of pain being treated, and the physical and psychological attributes of the patient.

Other actions the FDA is pursuing to combat opioid use disorder include working with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on guidelines for the proper opioid analgesic prescribing for acute pain resulting from specific conditions or procedures, and advancing policies that make immediate-release opioid formulations available in fixed-quantity packaging for 1 or 2 days.

“The FDA remains committed to addressing the opioid crisis on all fronts, with a significant focus on decreasing unnecessary exposure to opioids and preventing new addiction; supporting the treatment of those with opioid use disorder; fostering the development of novel pain treatment therapies and opioids more resistant to abuse and misuse; and taking action against those involved in the illegal importation and sale of opioids,” Dr. Throckmorton said.

Find the full statement by Dr. Throckmorton on the FDA website.

Romosozumab gets FDA approval for treating osteoporosis

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

NIH’s HEAL initiative seeks coordinated effort to tackle pain, addiction

MILWAUKEE – Congress has allocated a half billion dollars annually to the National Institutes of Health for a program that seeks to end America’s opioid crisis. The agency is putting in place over two-dozen projects spanning basic and translational research, clinical trials, and implementation of new strategies to address pain and fight addiction.

The , said Walter Koroshetz, MD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. This represents carryover from 2018, a planning year for the initiative, along with the 2019 $500 million annual supplement to the NIH’s base appropriation.

In 2018, NIH and other federal agencies successfully convinced Congress that funding a coordinated use of resources was necessary to overcome the country’s dual opioid and chronic pain crises. “Luck happens to the prepared,” said Dr. Koroshetz, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Bethesda, Md., adding that many hours went into putting together a national pain strategy that is multidisciplinary and multi-layered, and involves multiple players.

The two aims of research under the initiative are to improve treatments for misuse and addiction, and to enhance pain management. Focusing on this latter aim, Dr. Koroshetz said that the initiative has several research priorities to enhance pain management.

First, the biological basis for chronic pain needs to be understood in order to formulate effective therapies and interventions. “We need to understand the transition from acute to chronic pain,” he commented. “We need to see if we can learn about the risk factors for developing chronic pain; if we get really lucky, we might identify some biological markers” that identify who is at risk for this transition “in a high-risk acute pain situation.”

Next, a key request of industry and academia will be development of more drugs that avoid the dual-target program of opioids, which affect reward circuitry along with pain circuitry. “Drugs affecting the pain circuit and the reward circuit will always result in addiction” potential, said Dr. Koroshetz. “We’re still using drugs for pain from the poppy plant that were discovered 8,000 years ago.”

The hope with the HEAL initiative is to bring together academic centers with patient populations and research capabilities with industry, to accelerate moving nonaddictive treatments through to phase 3 trials.

The initiative also aims to promote discovery of new biologic targets for safe and effective pain treatment. New understanding of the physiology of pain has led to a multitude of candidate targets, said Dr. Koroshetz: “The good news is that there are so many potential targets. When I started in neurology in the ‘90s, I wouldn’t have said there were many, but now I’d say the list is long.”

Support for this work will require the development of human cell and tissue models, such as induced pluripotent stem cells, 3D printed organoids, and tissue chips. Several HEAL-funded grant mechanisms also seek research-industry collaboration to move investigational drugs for new targets through the pipeline quickly. The agency is hoping to see grantees apply new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, which can help identify new chemical structures and pinpoint new therapeutic targets for drug repurposing.

In addition to rapid drug discovery and accelerated clinical trials, Dr. Koroshetz said that HEAL leaders are hoping to see cross-pollination from two other NIH initiatives to boost pain-targeted medical device development. Both the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) and the Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) initiatives have already shown promise in identifying targets for effective, noninvasive pain relief devices, he said. Technologies being developed from these programs are “truly amazing,” he added.

A new focus on data and asset sharing among industry, academia, and NIH will “improve the quality, consistency, and efficiency of early-phase pain clinical trials,” Dr. Koroshetz continued. The Early Phase Pain Investigation Clinical Network (EPPIC-Net) will coordinate data and biosample hosting.

Through a competitive submission process, EPPIC-net will review dossiers from institutions or consortia that can serve as assets around which clinical trials can be designed and executed. These early-phase trials will focus on well-defined pain conditions with unmet need, such as chronic regional pain syndrome and tic douloureux, he said.

“We want to find patients who have well-defined conditions. We know the phenotypes, we know the natural history. We’re looking for clinical sites to work on these projects as part of one large team to bring new therapies to patients,” noted Dr. Koroshetz.

Further along the spectrum of research, comparative effectiveness research networks will provide a reality check to compare both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions all along the spectrum from acute to chronic pain. Here, data elements and storage will also be coordinated through EPPIC-Net.

Implementation science research will fine-tune the practicalities of bringing research to practice as the final piece of the puzzle, said Dr. Koroshetz.

Under NIH director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, Dr. Koroshetz is co-leading the HEAL initiative, along with Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. They wrote about the initiative in JAMA last year (JAMA. 2018 Jul 10;320[2]:129-30).

Dr. Koroshetz reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – Congress has allocated a half billion dollars annually to the National Institutes of Health for a program that seeks to end America’s opioid crisis. The agency is putting in place over two-dozen projects spanning basic and translational research, clinical trials, and implementation of new strategies to address pain and fight addiction.

The , said Walter Koroshetz, MD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. This represents carryover from 2018, a planning year for the initiative, along with the 2019 $500 million annual supplement to the NIH’s base appropriation.

In 2018, NIH and other federal agencies successfully convinced Congress that funding a coordinated use of resources was necessary to overcome the country’s dual opioid and chronic pain crises. “Luck happens to the prepared,” said Dr. Koroshetz, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Bethesda, Md., adding that many hours went into putting together a national pain strategy that is multidisciplinary and multi-layered, and involves multiple players.

The two aims of research under the initiative are to improve treatments for misuse and addiction, and to enhance pain management. Focusing on this latter aim, Dr. Koroshetz said that the initiative has several research priorities to enhance pain management.

First, the biological basis for chronic pain needs to be understood in order to formulate effective therapies and interventions. “We need to understand the transition from acute to chronic pain,” he commented. “We need to see if we can learn about the risk factors for developing chronic pain; if we get really lucky, we might identify some biological markers” that identify who is at risk for this transition “in a high-risk acute pain situation.”

Next, a key request of industry and academia will be development of more drugs that avoid the dual-target program of opioids, which affect reward circuitry along with pain circuitry. “Drugs affecting the pain circuit and the reward circuit will always result in addiction” potential, said Dr. Koroshetz. “We’re still using drugs for pain from the poppy plant that were discovered 8,000 years ago.”

The hope with the HEAL initiative is to bring together academic centers with patient populations and research capabilities with industry, to accelerate moving nonaddictive treatments through to phase 3 trials.

The initiative also aims to promote discovery of new biologic targets for safe and effective pain treatment. New understanding of the physiology of pain has led to a multitude of candidate targets, said Dr. Koroshetz: “The good news is that there are so many potential targets. When I started in neurology in the ‘90s, I wouldn’t have said there were many, but now I’d say the list is long.”

Support for this work will require the development of human cell and tissue models, such as induced pluripotent stem cells, 3D printed organoids, and tissue chips. Several HEAL-funded grant mechanisms also seek research-industry collaboration to move investigational drugs for new targets through the pipeline quickly. The agency is hoping to see grantees apply new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, which can help identify new chemical structures and pinpoint new therapeutic targets for drug repurposing.

In addition to rapid drug discovery and accelerated clinical trials, Dr. Koroshetz said that HEAL leaders are hoping to see cross-pollination from two other NIH initiatives to boost pain-targeted medical device development. Both the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) and the Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) initiatives have already shown promise in identifying targets for effective, noninvasive pain relief devices, he said. Technologies being developed from these programs are “truly amazing,” he added.

A new focus on data and asset sharing among industry, academia, and NIH will “improve the quality, consistency, and efficiency of early-phase pain clinical trials,” Dr. Koroshetz continued. The Early Phase Pain Investigation Clinical Network (EPPIC-Net) will coordinate data and biosample hosting.

Through a competitive submission process, EPPIC-net will review dossiers from institutions or consortia that can serve as assets around which clinical trials can be designed and executed. These early-phase trials will focus on well-defined pain conditions with unmet need, such as chronic regional pain syndrome and tic douloureux, he said.

“We want to find patients who have well-defined conditions. We know the phenotypes, we know the natural history. We’re looking for clinical sites to work on these projects as part of one large team to bring new therapies to patients,” noted Dr. Koroshetz.

Further along the spectrum of research, comparative effectiveness research networks will provide a reality check to compare both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions all along the spectrum from acute to chronic pain. Here, data elements and storage will also be coordinated through EPPIC-Net.

Implementation science research will fine-tune the practicalities of bringing research to practice as the final piece of the puzzle, said Dr. Koroshetz.

Under NIH director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, Dr. Koroshetz is co-leading the HEAL initiative, along with Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. They wrote about the initiative in JAMA last year (JAMA. 2018 Jul 10;320[2]:129-30).

Dr. Koroshetz reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – Congress has allocated a half billion dollars annually to the National Institutes of Health for a program that seeks to end America’s opioid crisis. The agency is putting in place over two-dozen projects spanning basic and translational research, clinical trials, and implementation of new strategies to address pain and fight addiction.

The , said Walter Koroshetz, MD, speaking at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. This represents carryover from 2018, a planning year for the initiative, along with the 2019 $500 million annual supplement to the NIH’s base appropriation.

In 2018, NIH and other federal agencies successfully convinced Congress that funding a coordinated use of resources was necessary to overcome the country’s dual opioid and chronic pain crises. “Luck happens to the prepared,” said Dr. Koroshetz, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Bethesda, Md., adding that many hours went into putting together a national pain strategy that is multidisciplinary and multi-layered, and involves multiple players.

The two aims of research under the initiative are to improve treatments for misuse and addiction, and to enhance pain management. Focusing on this latter aim, Dr. Koroshetz said that the initiative has several research priorities to enhance pain management.

First, the biological basis for chronic pain needs to be understood in order to formulate effective therapies and interventions. “We need to understand the transition from acute to chronic pain,” he commented. “We need to see if we can learn about the risk factors for developing chronic pain; if we get really lucky, we might identify some biological markers” that identify who is at risk for this transition “in a high-risk acute pain situation.”

Next, a key request of industry and academia will be development of more drugs that avoid the dual-target program of opioids, which affect reward circuitry along with pain circuitry. “Drugs affecting the pain circuit and the reward circuit will always result in addiction” potential, said Dr. Koroshetz. “We’re still using drugs for pain from the poppy plant that were discovered 8,000 years ago.”

The hope with the HEAL initiative is to bring together academic centers with patient populations and research capabilities with industry, to accelerate moving nonaddictive treatments through to phase 3 trials.

The initiative also aims to promote discovery of new biologic targets for safe and effective pain treatment. New understanding of the physiology of pain has led to a multitude of candidate targets, said Dr. Koroshetz: “The good news is that there are so many potential targets. When I started in neurology in the ‘90s, I wouldn’t have said there were many, but now I’d say the list is long.”

Support for this work will require the development of human cell and tissue models, such as induced pluripotent stem cells, 3D printed organoids, and tissue chips. Several HEAL-funded grant mechanisms also seek research-industry collaboration to move investigational drugs for new targets through the pipeline quickly. The agency is hoping to see grantees apply new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, which can help identify new chemical structures and pinpoint new therapeutic targets for drug repurposing.

In addition to rapid drug discovery and accelerated clinical trials, Dr. Koroshetz said that HEAL leaders are hoping to see cross-pollination from two other NIH initiatives to boost pain-targeted medical device development. Both the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) and the Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) initiatives have already shown promise in identifying targets for effective, noninvasive pain relief devices, he said. Technologies being developed from these programs are “truly amazing,” he added.

A new focus on data and asset sharing among industry, academia, and NIH will “improve the quality, consistency, and efficiency of early-phase pain clinical trials,” Dr. Koroshetz continued. The Early Phase Pain Investigation Clinical Network (EPPIC-Net) will coordinate data and biosample hosting.

Through a competitive submission process, EPPIC-net will review dossiers from institutions or consortia that can serve as assets around which clinical trials can be designed and executed. These early-phase trials will focus on well-defined pain conditions with unmet need, such as chronic regional pain syndrome and tic douloureux, he said.

“We want to find patients who have well-defined conditions. We know the phenotypes, we know the natural history. We’re looking for clinical sites to work on these projects as part of one large team to bring new therapies to patients,” noted Dr. Koroshetz.

Further along the spectrum of research, comparative effectiveness research networks will provide a reality check to compare both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions all along the spectrum from acute to chronic pain. Here, data elements and storage will also be coordinated through EPPIC-Net.

Implementation science research will fine-tune the practicalities of bringing research to practice as the final piece of the puzzle, said Dr. Koroshetz.

Under NIH director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, Dr. Koroshetz is co-leading the HEAL initiative, along with Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. They wrote about the initiative in JAMA last year (JAMA. 2018 Jul 10;320[2]:129-30).

Dr. Koroshetz reported no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Nonopioid Alternatives to Addressing Pain Intensity: A Retrospective Look at 2 Noninvasive Pain Treatment Devices

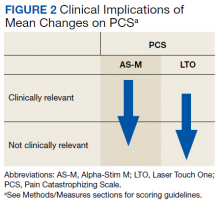

Chronic pain is common among veterans treated in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities, and optimal management remains challenging in the context of the national opioid misuse epidemic. The Eastern Oklahoma VA Health Care System (EOVAHCS) Pain Program offers a range of services that allow clinicians to tailor multimodal treatment strategies to a veteran’s needs. In 2014, a Modality Clinic was established to assess the utility of adding noninvasive treatment devices to the pain program’s armamentarium. This article addresses the context for introducing these devices and describes the EOVAHCS Pain Program and Modality Clinic. Also discussed are procedures and findings from an initial quality improvement evaluation designed to inform decision making regarding retention, expansion, or elimination of the EOVAHCS noninvasive, pain treatment device program.

Opioid prescriptions increased from 76 million in 1991 to 219 million in 2011. In 2011, the annual cost of chronic pain in the US was estimated at $635 billion.1-6 The confluence of an increasing concern about undertreatment of pain and overconfidence for the safety of opioids led to what former US Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, MD, called the opioid crisis.7 As awareness of its unintended consequences of opioid prescribing increased, the VHA began looking for nonopioid treatments that would decrease pain intensity. The 1993 article by Kehlet and Dahl was one of the first discussions of a multimodal nonpharmacologic strategy for addressing acute postoperative pain.8 Their pivotal literature review concluded that nonpharmacologic modalities, such as acupuncture, cranial manipulation, cranial electrostimulation treatment (CES), and low-level light technologies (LLLT), carried less risk and produced equal or greater clinical effects than those of drug therapies.8