User login

20-year-old male college basketball prospect • wrist pain after falling on wrist • normal ROM • pain with active/passive wrist extension • Dx?

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our family medicine clinic with right wrist pain 4 days after falling on his wrist and hand while playing basketball. He denied any other previous injury or trauma. The pain was unchanged since the injury occurred.

Examination demonstrated mild edema over the palmar and ulnar aspect of the patient’s right wrist with no apparent ecchymosis. He had normal range of motion of his right wrist and hand. However, he experienced pain with active and passive wrist extension and ulnar deviation. There was significant tenderness in the palmar and ulnar aspects of his right wrist just distal to the ulnar styloid process.

THE DIAGNOSIS

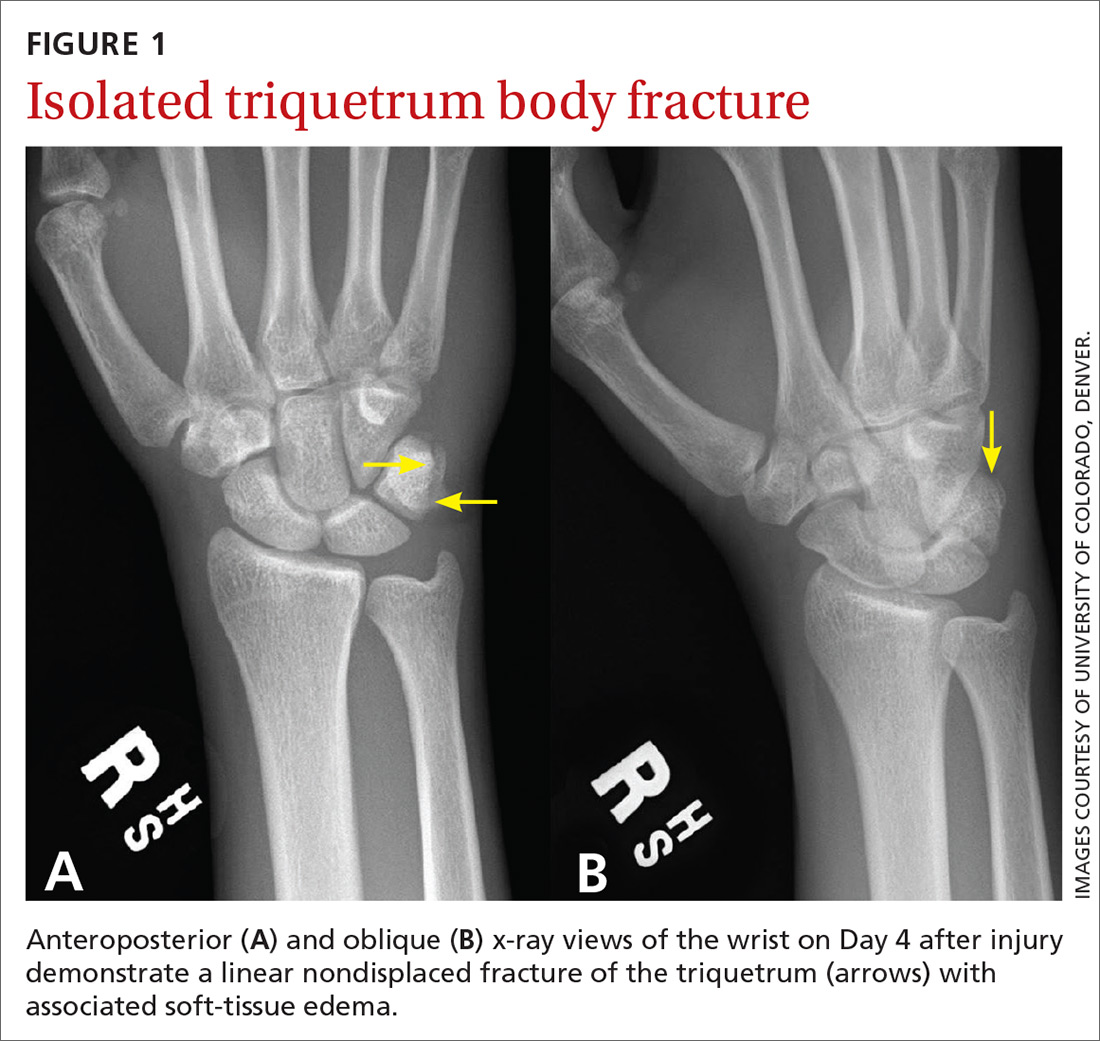

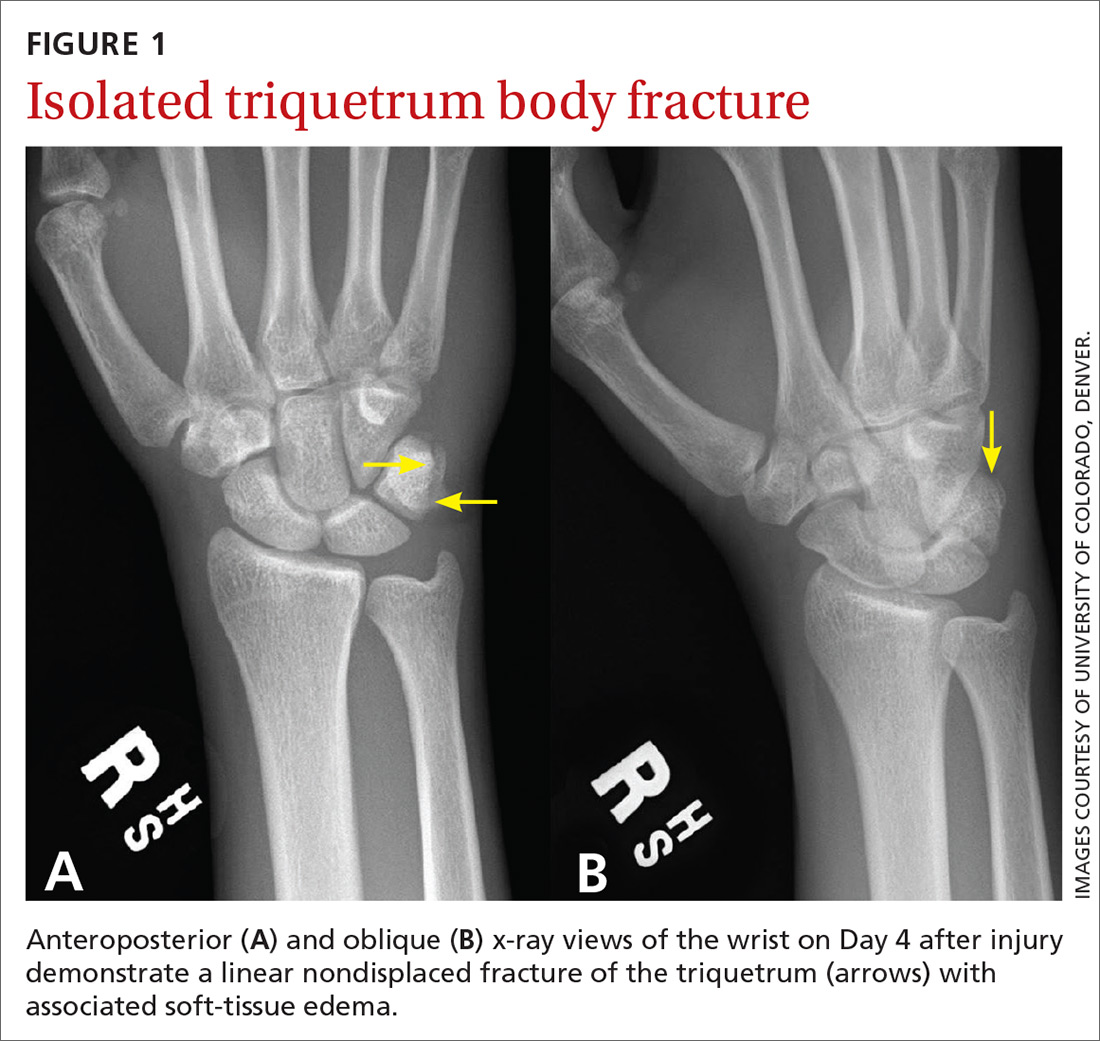

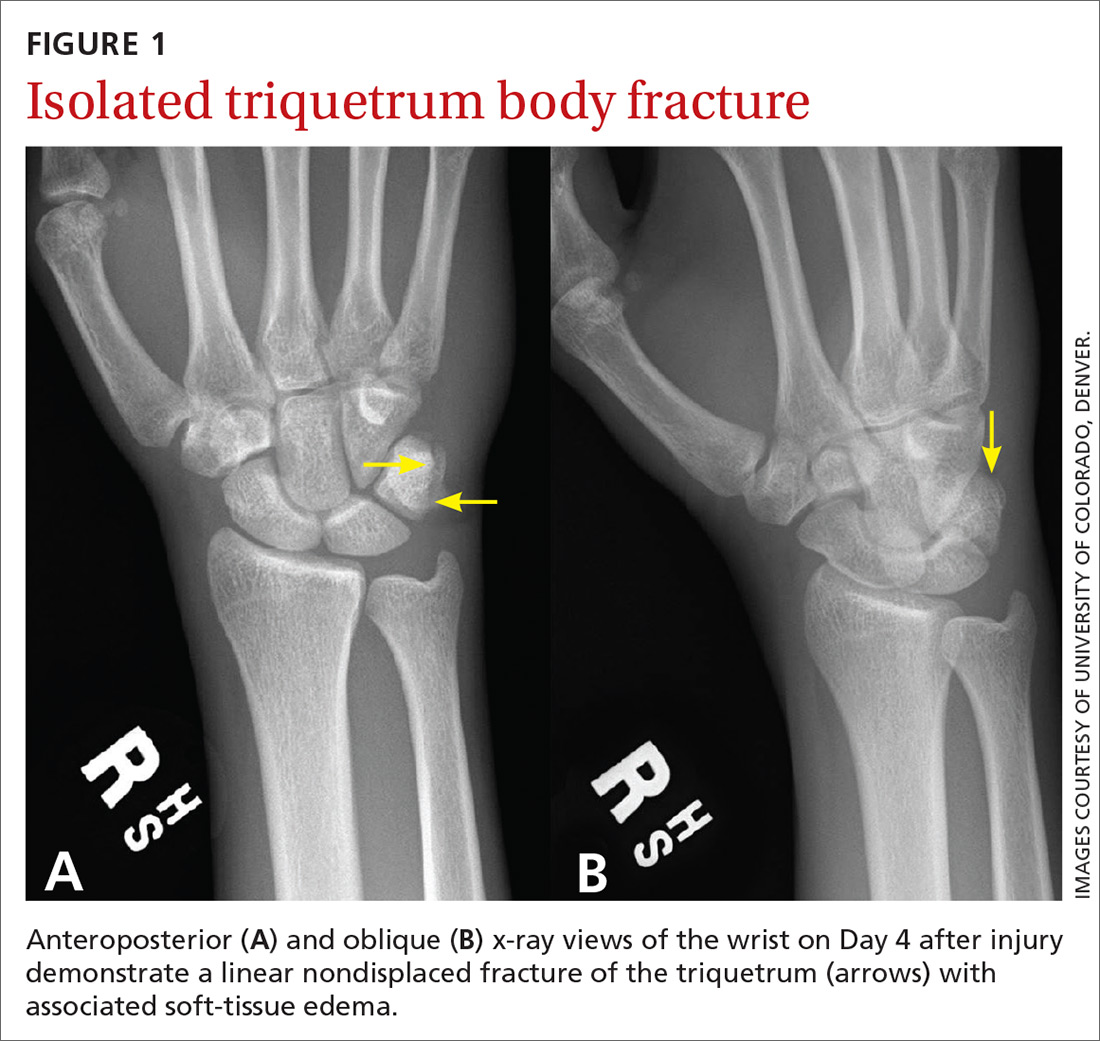

Standard plain x-rays of the right wrist revealed an isolated fracture of the body of the triquetrum (FIGURE 1). Since the patient refused to have a cast placed, his wrist was immobilized with a wrist brace. By Day 16 post injury, the pain and edema had improved significantly. After talking with the patient about the potential risks and benefits of continuing to play basketball—and despite our recommendation that he not play—he decided to continue playing since he was a college basketball prospect.

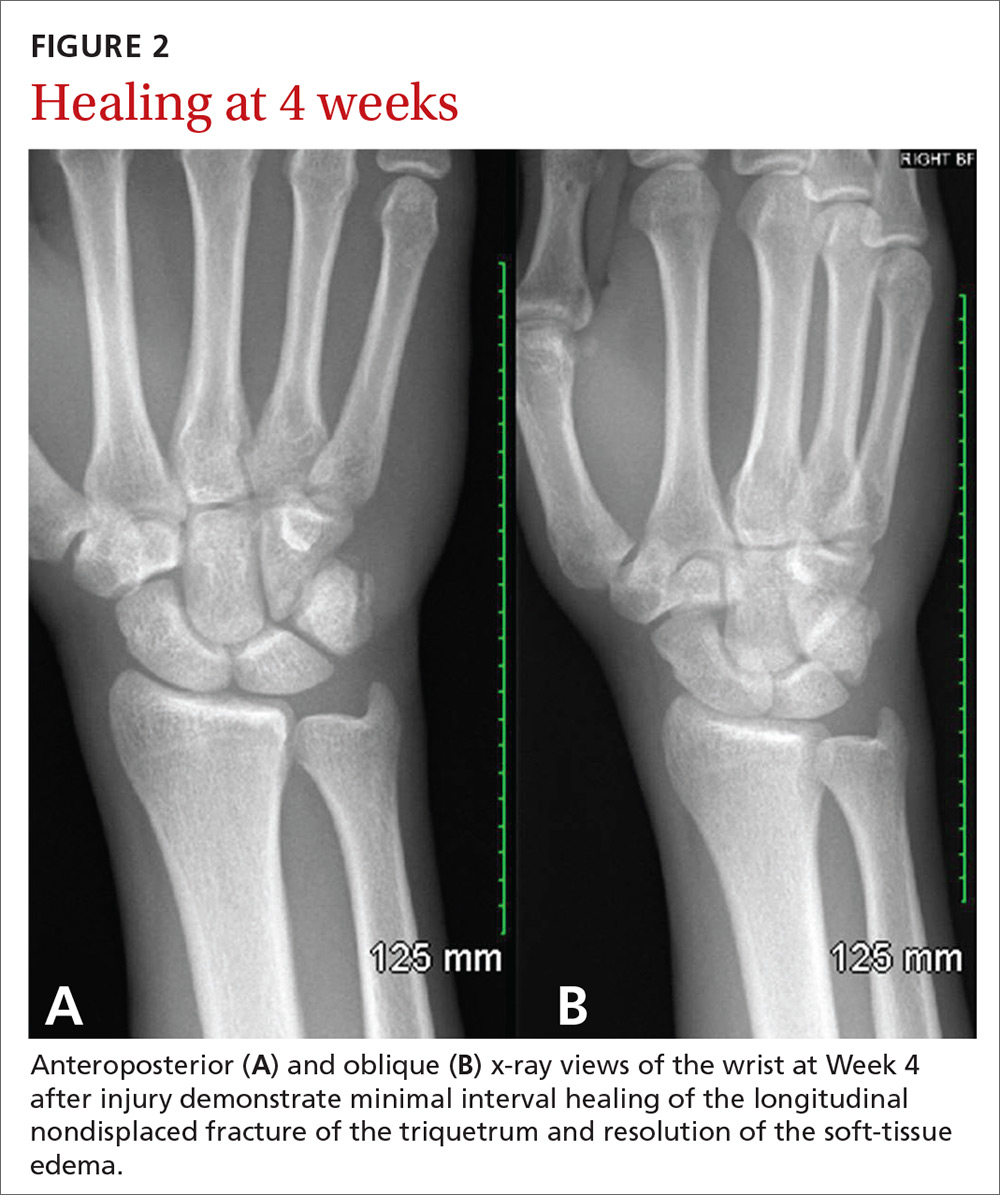

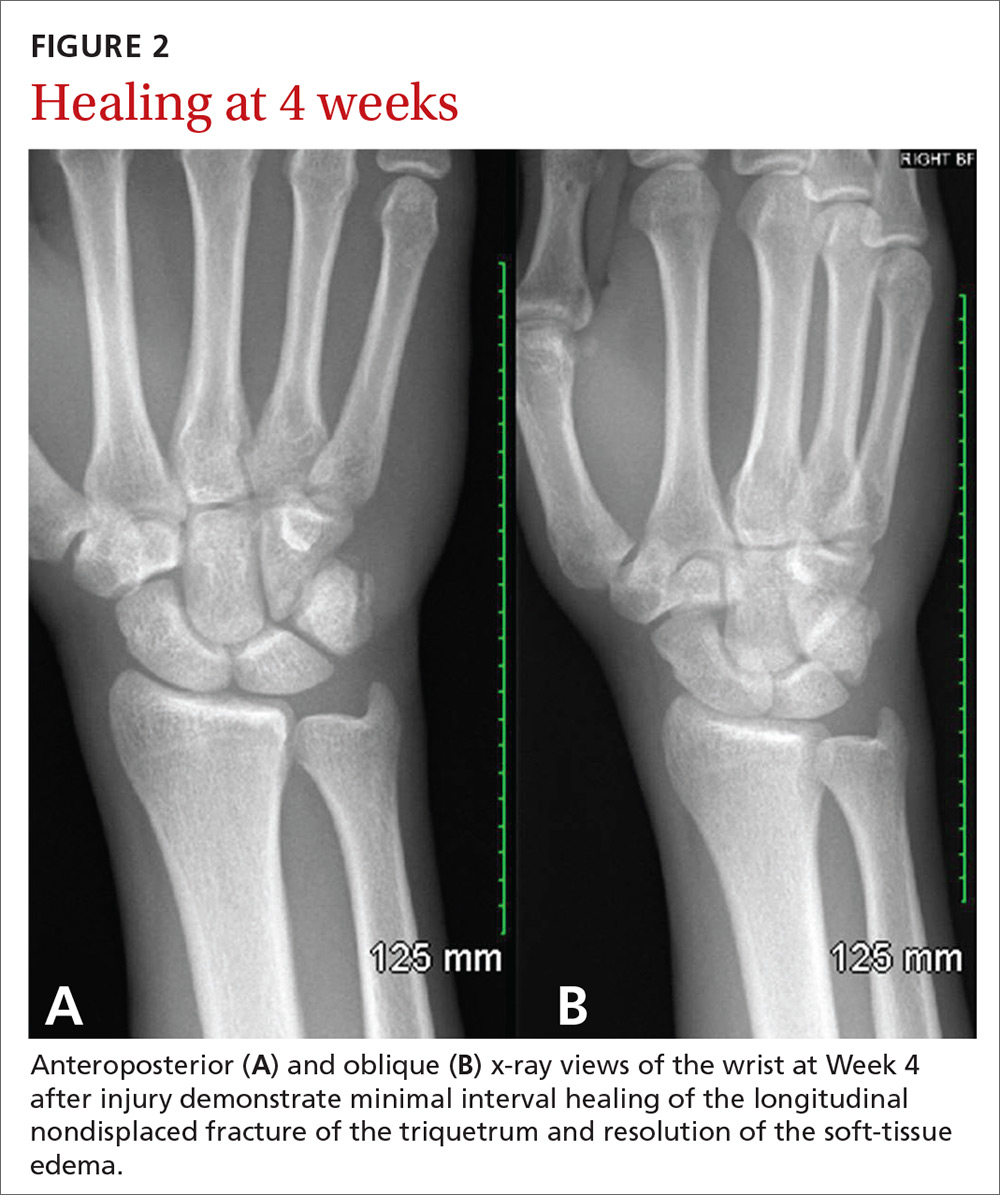

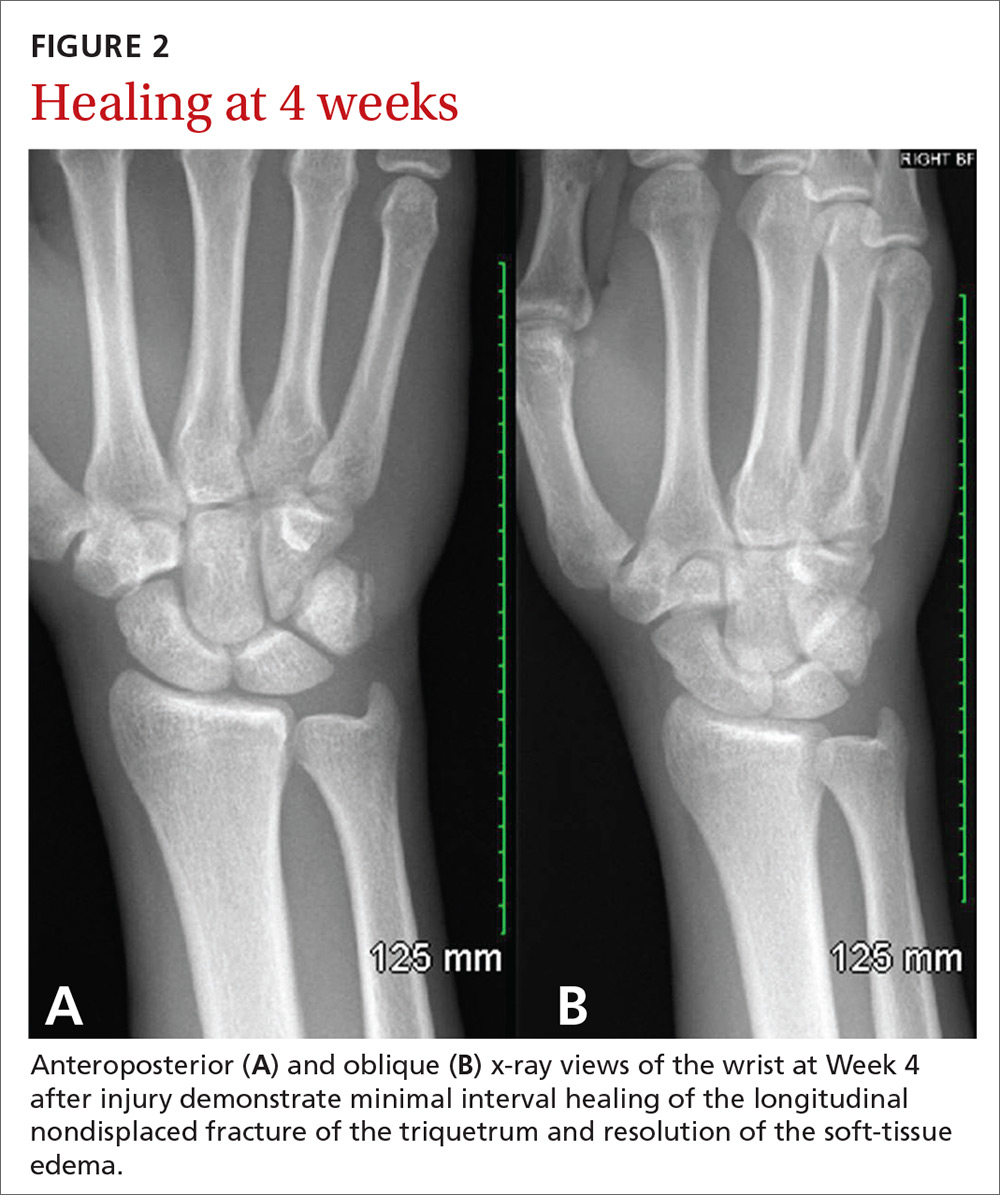

At 4 weeks post injury, x-rays demonstrated mild interval healing (FIGURE 2). At the 8-week visit, the patient had only very mild pain and tenderness, and x-ray images showed improvement (FIGURE 3). Within a few months, his symptoms resolved completely. No further imaging was performed.

DISCUSSION

In general, carpal fractures are uncommon.1 The triquetrum is the second most commonly injured carpal bone, involved in up to 18% of all carpal fractures.2,3 Triquetrum fractures most commonly occur as isolated injuries and are typically classified in 2 general categories: avulsion fractures (dorsal cortex or volar cortex) and fractures of the triquetrum body.4-8 Isolated avulsion fractures of the triquetral dorsal cortex are relatively common, occurring in about 95% of triquetrum injuries.4-9 Isolated fractures of the triquetrum body are less common, occurring in about 4% of triquetrum injuries, and can go unnoticed on conventional x-rays.4-9

Basketball presents a unique risk for hand or wrist fracture due to its high-impact nature, hard playing surfaces, and frequent use of the hands for dribbling, shooting, rebounding, and passing the ball.

In a retrospective study of sports-related fractures conducted at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, basketball had the highest incidence of carpal injuries compared with other sports, including football, rugby, skiing, snowboarding, and ice-skating.4 Similarly, a retrospective study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that of all Division 1 collegiate athletes at the school, basketball players had the highest incidence of primary fractures, and the most common fracture location was the hand.10

Continue to: An injury that's easy to miss

An injury that’s easy to miss

Because the incidence of hand and wrist injuries is high among basketball players, it is imperative that triquetrum body fractures are not missed or misdiagnosed as more common hand and wrist injuries, such as triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures.

Our patient, who had an isolated triquetrum body fracture, presented with focal tenderness on the palmar and ulnar aspects of his wrist and pain with ulnar deviation. Since triquetral body fractures often have a clinical presentation quite similar to that of triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures, patients presenting with symptoms of wrist tenderness and pain should be treated with a high degree of clinical suspicion.

With our patient, anteroposterior and lateral x-rays were sufficient to demonstrate an isolated triquetrum body fracture; however, triquetral fractures can be missed in up to 20% of x-rays.4 Both magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography are useful in diagnosing occult triquetrum fractures and should be used to confirm clinical suspicion when traditional x-rays are inconclusive.11,12

Management varies

Management of isolated triquetrum body fractures varies depending on the fracture pattern and the status of bone consolidation. Triquetral body fractures typically heal well; it’s very rare that there is a nonunion. As our patient’s fracture was nondisplaced and stable, brace immobilization for 4 weeks was sufficient to facilitate healing and restore long-term hand and wrist functionality. This course of treatment is consistent with other cases of nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures reported in the literature.13

Long-term outcomes. The literature is sparse regarding the long-term functional outcome of nonsurgical treatment for nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures. Multiple carpal fractures, displaced triquetrum body fractures, and persistent pain for multiple months after nonsurgical management all indicate the need for referral to orthopedic surgery. In instances of fracture displacement or nonunion, management tends to be surgical, with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) used in multiple cases of nonunion for isolated triquetrum body fractures.3,14 Any diagnostic imaging that reveals displacement, malunion, or nonunion of the fracture is an indication for referral to an orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Return to play

Return to play. There is no evidence-based return-to-play recommendation for patients with a triquetrum fracture. However, our patient continued to play basketball through the early stages of injury management because he was a collegiate prospect. While medical, social, and economic factors should be considered when discussing treatment options with athletes, injuries should be managed so that there is no long-term loss of function or risk of injury exacerbation. When discussing early return from injury with athletes who have outside pressure to return to play, it’s important to make them aware of the associated long- and short-term risks.15

THE TAKEAWAY

Management of an isolated triquetrum body fracture is typically straightforward; however, if the fracture is displaced, refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon as ORIF may be required. For this reason, it’s important to be able to promptly identify isolated triquetrum body fractures and to avoid confusing them with triquetrum dorsal avulsion fractures.

Depending on the sport played and the severity of the injury, athletes with conservatively managed nondisplaced triquetral body fractures may be candidates for early return to play. Nonetheless, athletes should understand both the short- and the long-term risks of playing with an injury, and they should never be advised to continue playing with an injury if it jeopardizes their well-being or the long-term functionality of the affected body part.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Suh N, Ek ET, Wolfe SW. Carpal fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:785-791.

2. Hey HW, Chong AK, Murphy D. Prevalence of carpal fracture in Singapore. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:278-283.

3. Al Rashid M, Rasoli S, Khan WS. Non-union of isolated displaced triquetral body fracture—a case report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14:71-74.

4. Becce F, Theumann N, Bollmann C, et al. Dorsal fractures of the triquetrum: MRI findings with an emphasis on dorsal carpal ligament injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:608-617.

5. Court-Brown CM, Wood AM, Aitken S. The epidemiology of acute sports-related fractures in adults. Injury. 2008;39:1365-1372.

6. Urch EY, Lee SK. Carpal fractures other than scaphoid. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:51-67.

7. deWeber K. Triquetrum fractures. UpToDate. 2016. www.uptodate.com/contents/triquetrum-fractures. Accessed September 3, 2019.

8. Höcker K, Menschik A. Chip fractures of the triquetrum. Mechanism, classification and results. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:584-588.

9. Jarraya M, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, et al. Radiographically occult and subtle fractures: a pictorial review. Radiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:370169.

10. Hame SL, LaFemina JM, McAllister DR, et al. Fractures in the collegiate athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:446-451.

11. Hindman BW, Kulik WJ, Lee G, et al. Occult fractures of the carpals and metacarpals: demonstration by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:529-532.

12. Pierre-Jerome C, Moncayo V, Albastaki U, et al. Multiple occult wrist bone injuries and joint effusions: prevalence and distribution on MRI. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:179-184.

13. Yildirim C, Akmaz I, Keklikçi K, et al. An unusual combined fracture pattern of the triquetrum. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:385-386.

14. Rasoli S, Ricks M, Packer G. Isolated displaced non-union of a triquetral body fracture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:54.

15. Strickland JW. Considerations for the treatment of the injured athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:397-400.

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our family medicine clinic with right wrist pain 4 days after falling on his wrist and hand while playing basketball. He denied any other previous injury or trauma. The pain was unchanged since the injury occurred.

Examination demonstrated mild edema over the palmar and ulnar aspect of the patient’s right wrist with no apparent ecchymosis. He had normal range of motion of his right wrist and hand. However, he experienced pain with active and passive wrist extension and ulnar deviation. There was significant tenderness in the palmar and ulnar aspects of his right wrist just distal to the ulnar styloid process.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Standard plain x-rays of the right wrist revealed an isolated fracture of the body of the triquetrum (FIGURE 1). Since the patient refused to have a cast placed, his wrist was immobilized with a wrist brace. By Day 16 post injury, the pain and edema had improved significantly. After talking with the patient about the potential risks and benefits of continuing to play basketball—and despite our recommendation that he not play—he decided to continue playing since he was a college basketball prospect.

At 4 weeks post injury, x-rays demonstrated mild interval healing (FIGURE 2). At the 8-week visit, the patient had only very mild pain and tenderness, and x-ray images showed improvement (FIGURE 3). Within a few months, his symptoms resolved completely. No further imaging was performed.

DISCUSSION

In general, carpal fractures are uncommon.1 The triquetrum is the second most commonly injured carpal bone, involved in up to 18% of all carpal fractures.2,3 Triquetrum fractures most commonly occur as isolated injuries and are typically classified in 2 general categories: avulsion fractures (dorsal cortex or volar cortex) and fractures of the triquetrum body.4-8 Isolated avulsion fractures of the triquetral dorsal cortex are relatively common, occurring in about 95% of triquetrum injuries.4-9 Isolated fractures of the triquetrum body are less common, occurring in about 4% of triquetrum injuries, and can go unnoticed on conventional x-rays.4-9

Basketball presents a unique risk for hand or wrist fracture due to its high-impact nature, hard playing surfaces, and frequent use of the hands for dribbling, shooting, rebounding, and passing the ball.

In a retrospective study of sports-related fractures conducted at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, basketball had the highest incidence of carpal injuries compared with other sports, including football, rugby, skiing, snowboarding, and ice-skating.4 Similarly, a retrospective study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that of all Division 1 collegiate athletes at the school, basketball players had the highest incidence of primary fractures, and the most common fracture location was the hand.10

Continue to: An injury that's easy to miss

An injury that’s easy to miss

Because the incidence of hand and wrist injuries is high among basketball players, it is imperative that triquetrum body fractures are not missed or misdiagnosed as more common hand and wrist injuries, such as triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures.

Our patient, who had an isolated triquetrum body fracture, presented with focal tenderness on the palmar and ulnar aspects of his wrist and pain with ulnar deviation. Since triquetral body fractures often have a clinical presentation quite similar to that of triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures, patients presenting with symptoms of wrist tenderness and pain should be treated with a high degree of clinical suspicion.

With our patient, anteroposterior and lateral x-rays were sufficient to demonstrate an isolated triquetrum body fracture; however, triquetral fractures can be missed in up to 20% of x-rays.4 Both magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography are useful in diagnosing occult triquetrum fractures and should be used to confirm clinical suspicion when traditional x-rays are inconclusive.11,12

Management varies

Management of isolated triquetrum body fractures varies depending on the fracture pattern and the status of bone consolidation. Triquetral body fractures typically heal well; it’s very rare that there is a nonunion. As our patient’s fracture was nondisplaced and stable, brace immobilization for 4 weeks was sufficient to facilitate healing and restore long-term hand and wrist functionality. This course of treatment is consistent with other cases of nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures reported in the literature.13

Long-term outcomes. The literature is sparse regarding the long-term functional outcome of nonsurgical treatment for nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures. Multiple carpal fractures, displaced triquetrum body fractures, and persistent pain for multiple months after nonsurgical management all indicate the need for referral to orthopedic surgery. In instances of fracture displacement or nonunion, management tends to be surgical, with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) used in multiple cases of nonunion for isolated triquetrum body fractures.3,14 Any diagnostic imaging that reveals displacement, malunion, or nonunion of the fracture is an indication for referral to an orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Return to play

Return to play. There is no evidence-based return-to-play recommendation for patients with a triquetrum fracture. However, our patient continued to play basketball through the early stages of injury management because he was a collegiate prospect. While medical, social, and economic factors should be considered when discussing treatment options with athletes, injuries should be managed so that there is no long-term loss of function or risk of injury exacerbation. When discussing early return from injury with athletes who have outside pressure to return to play, it’s important to make them aware of the associated long- and short-term risks.15

THE TAKEAWAY

Management of an isolated triquetrum body fracture is typically straightforward; however, if the fracture is displaced, refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon as ORIF may be required. For this reason, it’s important to be able to promptly identify isolated triquetrum body fractures and to avoid confusing them with triquetrum dorsal avulsion fractures.

Depending on the sport played and the severity of the injury, athletes with conservatively managed nondisplaced triquetral body fractures may be candidates for early return to play. Nonetheless, athletes should understand both the short- and the long-term risks of playing with an injury, and they should never be advised to continue playing with an injury if it jeopardizes their well-being or the long-term functionality of the affected body part.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our family medicine clinic with right wrist pain 4 days after falling on his wrist and hand while playing basketball. He denied any other previous injury or trauma. The pain was unchanged since the injury occurred.

Examination demonstrated mild edema over the palmar and ulnar aspect of the patient’s right wrist with no apparent ecchymosis. He had normal range of motion of his right wrist and hand. However, he experienced pain with active and passive wrist extension and ulnar deviation. There was significant tenderness in the palmar and ulnar aspects of his right wrist just distal to the ulnar styloid process.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Standard plain x-rays of the right wrist revealed an isolated fracture of the body of the triquetrum (FIGURE 1). Since the patient refused to have a cast placed, his wrist was immobilized with a wrist brace. By Day 16 post injury, the pain and edema had improved significantly. After talking with the patient about the potential risks and benefits of continuing to play basketball—and despite our recommendation that he not play—he decided to continue playing since he was a college basketball prospect.

At 4 weeks post injury, x-rays demonstrated mild interval healing (FIGURE 2). At the 8-week visit, the patient had only very mild pain and tenderness, and x-ray images showed improvement (FIGURE 3). Within a few months, his symptoms resolved completely. No further imaging was performed.

DISCUSSION

In general, carpal fractures are uncommon.1 The triquetrum is the second most commonly injured carpal bone, involved in up to 18% of all carpal fractures.2,3 Triquetrum fractures most commonly occur as isolated injuries and are typically classified in 2 general categories: avulsion fractures (dorsal cortex or volar cortex) and fractures of the triquetrum body.4-8 Isolated avulsion fractures of the triquetral dorsal cortex are relatively common, occurring in about 95% of triquetrum injuries.4-9 Isolated fractures of the triquetrum body are less common, occurring in about 4% of triquetrum injuries, and can go unnoticed on conventional x-rays.4-9

Basketball presents a unique risk for hand or wrist fracture due to its high-impact nature, hard playing surfaces, and frequent use of the hands for dribbling, shooting, rebounding, and passing the ball.

In a retrospective study of sports-related fractures conducted at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, basketball had the highest incidence of carpal injuries compared with other sports, including football, rugby, skiing, snowboarding, and ice-skating.4 Similarly, a retrospective study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that of all Division 1 collegiate athletes at the school, basketball players had the highest incidence of primary fractures, and the most common fracture location was the hand.10

Continue to: An injury that's easy to miss

An injury that’s easy to miss

Because the incidence of hand and wrist injuries is high among basketball players, it is imperative that triquetrum body fractures are not missed or misdiagnosed as more common hand and wrist injuries, such as triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures.

Our patient, who had an isolated triquetrum body fracture, presented with focal tenderness on the palmar and ulnar aspects of his wrist and pain with ulnar deviation. Since triquetral body fractures often have a clinical presentation quite similar to that of triquetral dorsal avulsion fractures, patients presenting with symptoms of wrist tenderness and pain should be treated with a high degree of clinical suspicion.

With our patient, anteroposterior and lateral x-rays were sufficient to demonstrate an isolated triquetrum body fracture; however, triquetral fractures can be missed in up to 20% of x-rays.4 Both magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography are useful in diagnosing occult triquetrum fractures and should be used to confirm clinical suspicion when traditional x-rays are inconclusive.11,12

Management varies

Management of isolated triquetrum body fractures varies depending on the fracture pattern and the status of bone consolidation. Triquetral body fractures typically heal well; it’s very rare that there is a nonunion. As our patient’s fracture was nondisplaced and stable, brace immobilization for 4 weeks was sufficient to facilitate healing and restore long-term hand and wrist functionality. This course of treatment is consistent with other cases of nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures reported in the literature.13

Long-term outcomes. The literature is sparse regarding the long-term functional outcome of nonsurgical treatment for nondisplaced triquetrum body fractures. Multiple carpal fractures, displaced triquetrum body fractures, and persistent pain for multiple months after nonsurgical management all indicate the need for referral to orthopedic surgery. In instances of fracture displacement or nonunion, management tends to be surgical, with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) used in multiple cases of nonunion for isolated triquetrum body fractures.3,14 Any diagnostic imaging that reveals displacement, malunion, or nonunion of the fracture is an indication for referral to an orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Return to play

Return to play. There is no evidence-based return-to-play recommendation for patients with a triquetrum fracture. However, our patient continued to play basketball through the early stages of injury management because he was a collegiate prospect. While medical, social, and economic factors should be considered when discussing treatment options with athletes, injuries should be managed so that there is no long-term loss of function or risk of injury exacerbation. When discussing early return from injury with athletes who have outside pressure to return to play, it’s important to make them aware of the associated long- and short-term risks.15

THE TAKEAWAY

Management of an isolated triquetrum body fracture is typically straightforward; however, if the fracture is displaced, refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon as ORIF may be required. For this reason, it’s important to be able to promptly identify isolated triquetrum body fractures and to avoid confusing them with triquetrum dorsal avulsion fractures.

Depending on the sport played and the severity of the injury, athletes with conservatively managed nondisplaced triquetral body fractures may be candidates for early return to play. Nonetheless, athletes should understand both the short- and the long-term risks of playing with an injury, and they should never be advised to continue playing with an injury if it jeopardizes their well-being or the long-term functionality of the affected body part.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Suh N, Ek ET, Wolfe SW. Carpal fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:785-791.

2. Hey HW, Chong AK, Murphy D. Prevalence of carpal fracture in Singapore. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:278-283.

3. Al Rashid M, Rasoli S, Khan WS. Non-union of isolated displaced triquetral body fracture—a case report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14:71-74.

4. Becce F, Theumann N, Bollmann C, et al. Dorsal fractures of the triquetrum: MRI findings with an emphasis on dorsal carpal ligament injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:608-617.

5. Court-Brown CM, Wood AM, Aitken S. The epidemiology of acute sports-related fractures in adults. Injury. 2008;39:1365-1372.

6. Urch EY, Lee SK. Carpal fractures other than scaphoid. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:51-67.

7. deWeber K. Triquetrum fractures. UpToDate. 2016. www.uptodate.com/contents/triquetrum-fractures. Accessed September 3, 2019.

8. Höcker K, Menschik A. Chip fractures of the triquetrum. Mechanism, classification and results. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:584-588.

9. Jarraya M, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, et al. Radiographically occult and subtle fractures: a pictorial review. Radiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:370169.

10. Hame SL, LaFemina JM, McAllister DR, et al. Fractures in the collegiate athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:446-451.

11. Hindman BW, Kulik WJ, Lee G, et al. Occult fractures of the carpals and metacarpals: demonstration by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:529-532.

12. Pierre-Jerome C, Moncayo V, Albastaki U, et al. Multiple occult wrist bone injuries and joint effusions: prevalence and distribution on MRI. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:179-184.

13. Yildirim C, Akmaz I, Keklikçi K, et al. An unusual combined fracture pattern of the triquetrum. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:385-386.

14. Rasoli S, Ricks M, Packer G. Isolated displaced non-union of a triquetral body fracture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:54.

15. Strickland JW. Considerations for the treatment of the injured athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:397-400.

1. Suh N, Ek ET, Wolfe SW. Carpal fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:785-791.

2. Hey HW, Chong AK, Murphy D. Prevalence of carpal fracture in Singapore. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:278-283.

3. Al Rashid M, Rasoli S, Khan WS. Non-union of isolated displaced triquetral body fracture—a case report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14:71-74.

4. Becce F, Theumann N, Bollmann C, et al. Dorsal fractures of the triquetrum: MRI findings with an emphasis on dorsal carpal ligament injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:608-617.

5. Court-Brown CM, Wood AM, Aitken S. The epidemiology of acute sports-related fractures in adults. Injury. 2008;39:1365-1372.

6. Urch EY, Lee SK. Carpal fractures other than scaphoid. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:51-67.

7. deWeber K. Triquetrum fractures. UpToDate. 2016. www.uptodate.com/contents/triquetrum-fractures. Accessed September 3, 2019.

8. Höcker K, Menschik A. Chip fractures of the triquetrum. Mechanism, classification and results. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:584-588.

9. Jarraya M, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, et al. Radiographically occult and subtle fractures: a pictorial review. Radiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:370169.

10. Hame SL, LaFemina JM, McAllister DR, et al. Fractures in the collegiate athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:446-451.

11. Hindman BW, Kulik WJ, Lee G, et al. Occult fractures of the carpals and metacarpals: demonstration by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:529-532.

12. Pierre-Jerome C, Moncayo V, Albastaki U, et al. Multiple occult wrist bone injuries and joint effusions: prevalence and distribution on MRI. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:179-184.

13. Yildirim C, Akmaz I, Keklikçi K, et al. An unusual combined fracture pattern of the triquetrum. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:385-386.

14. Rasoli S, Ricks M, Packer G. Isolated displaced non-union of a triquetral body fracture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:54.

15. Strickland JW. Considerations for the treatment of the injured athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:397-400.

Novel research aims to improve ED care in sickle cell disease

Several initiatives are in the works to improve the management of patients with sickle cell disease in the ED, experts said at a recent webinar held by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In 2014, the NHLBI released evidence-based guidelines for the management of patients with sickle cell disease. The expert panel provided recommendations on the treatment of acute complications of sickle cell disease, many of which are common reasons for ED visits.

Optimizing the treatment of acute complications, namely vasoocclusive crisis, is essential to ensure improved long-term outcomes, explained Paula Tanabe, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Pain management

While the majority of pain-related ED visits in sickle cell are the result of vasoocclusive crisis, other causes, such as acute chest syndrome, abdominal catastrophes, and splenic sequestration, are also important.

The hallmark of pain management in this population is rapid and aggressive treatment with intravenous opioids. The use of individualized doses is also important, but if not available, an sickle cell disease–specific pain protocol can be used, she explained.

Recent evidence has confirmed the benefit of using an individualized (patient-specific) dosing protocol. Dr. Tanabe reported the results of a randomized pilot study that compared two pain protocols for patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode in the ED.

“The reason we pursued this project is to generate additional evidence beyond the expert panel,” she said.

The primary outcome of the study was the difference in pain scores from arrival to discharge between patients receiving an individualized or weight-based dosing protocol. Secondary outcomes included safety, pain experience, and side effects, among others.

The researchers found that patients who received an individualized protocol had significantly lower pain scores, compared with a standard weight-based protocol (between-protocol pain score difference, 15.6 plus or minus 5.0; P = .002).

Additionally, patients in the individualized dosing arm were admitted less often than those in the weight-based arm (P = .03), Dr. Tanabe reported.

The findings from the previous study formed the basis for an ongoing study that is further examining the impact of patient-specific dosing in patients who present with a vasoocclusive episode. The COMPARE VOE study is currently enrolling patients and is being funded by NHLBI.

The NHLBI also provides funding to eight Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium sites throughout the United States. The objective of this grant funding is to help implement NHLBI recommendations in the emergency setting.

Quality improvement

“One area [that] we want to improve is how quickly we administer [analgesic therapy] to patients when they are experiencing a vasoocclusive episode,” said Caroline Freiermuth, MD, of the University of Cincinnati.

Some common barriers to delivering rapid analgesia in this setting include difficulties in obtaining intravenous access, high patient volumes, lack of education, and provider biases, she explained.

With respect to high patient volumes, one strategy that may help overcome this barrier is to triage patients as Emergency Severity Index level 2, allowing for accelerated room placement.

Sickle cell patients undergoing vasoocclusive crisis meet the criteria for level 2 based on morbidity, degree of pain, and the level of resources often required.

Another important strategy is improving education related to sickle cell disease, particularly the high morbidity and mortality seen in these patients, Dr. Freiermuth said.

“The median lifespan for patients with HbSS disease is in the 40s, basically half of the lifespan of a typical American,” she said.

At present, acute chest syndrome is the principal cause of death in patients with sickle cell disease, and most frequently occurs during a vasoocclusive episode. As a result, screening for this complication is essential to reduce mortality in the emergency setting.

Dr. Freiermuth explained that one of the best ways to prevent acute chest syndrome is to encourage the use of incentive spirometry in patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode.

In order to increase the likelihood of obtaining intravenous access, the use of ultrasound may help guide placement. Educating nurses on the proper use of ultrasound-guided placement of intravenous catheters is one practical approach, she said.

Alternatively, opioid analgesia can be administered subcutaneously. Benefits of subcutaneous delivery include comparable pharmacokinetics, less pain, and a reduced likelihood of sterile abscesses that are often seen with intramuscular administration.

Dr. Freiermuth outlined the quality-improvement initiative being tested at her institution, which involves the administration of parenteral opioid therapy during triage for sickle cell patients undergoing a suspected vasoocclusive crisis. The initiative was developed with input from both the emergency and hematology departments at the site.

Early results have shown no significant changes using this approach, but the data is still preliminary. Initial feedback has revealed that time to room placement has been the greatest barrier, she reported.

Dr. Tanabe reported grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Freiermuth reported research support from Pfizer.

Several initiatives are in the works to improve the management of patients with sickle cell disease in the ED, experts said at a recent webinar held by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In 2014, the NHLBI released evidence-based guidelines for the management of patients with sickle cell disease. The expert panel provided recommendations on the treatment of acute complications of sickle cell disease, many of which are common reasons for ED visits.

Optimizing the treatment of acute complications, namely vasoocclusive crisis, is essential to ensure improved long-term outcomes, explained Paula Tanabe, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Pain management

While the majority of pain-related ED visits in sickle cell are the result of vasoocclusive crisis, other causes, such as acute chest syndrome, abdominal catastrophes, and splenic sequestration, are also important.

The hallmark of pain management in this population is rapid and aggressive treatment with intravenous opioids. The use of individualized doses is also important, but if not available, an sickle cell disease–specific pain protocol can be used, she explained.

Recent evidence has confirmed the benefit of using an individualized (patient-specific) dosing protocol. Dr. Tanabe reported the results of a randomized pilot study that compared two pain protocols for patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode in the ED.

“The reason we pursued this project is to generate additional evidence beyond the expert panel,” she said.

The primary outcome of the study was the difference in pain scores from arrival to discharge between patients receiving an individualized or weight-based dosing protocol. Secondary outcomes included safety, pain experience, and side effects, among others.

The researchers found that patients who received an individualized protocol had significantly lower pain scores, compared with a standard weight-based protocol (between-protocol pain score difference, 15.6 plus or minus 5.0; P = .002).

Additionally, patients in the individualized dosing arm were admitted less often than those in the weight-based arm (P = .03), Dr. Tanabe reported.

The findings from the previous study formed the basis for an ongoing study that is further examining the impact of patient-specific dosing in patients who present with a vasoocclusive episode. The COMPARE VOE study is currently enrolling patients and is being funded by NHLBI.

The NHLBI also provides funding to eight Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium sites throughout the United States. The objective of this grant funding is to help implement NHLBI recommendations in the emergency setting.

Quality improvement

“One area [that] we want to improve is how quickly we administer [analgesic therapy] to patients when they are experiencing a vasoocclusive episode,” said Caroline Freiermuth, MD, of the University of Cincinnati.

Some common barriers to delivering rapid analgesia in this setting include difficulties in obtaining intravenous access, high patient volumes, lack of education, and provider biases, she explained.

With respect to high patient volumes, one strategy that may help overcome this barrier is to triage patients as Emergency Severity Index level 2, allowing for accelerated room placement.

Sickle cell patients undergoing vasoocclusive crisis meet the criteria for level 2 based on morbidity, degree of pain, and the level of resources often required.

Another important strategy is improving education related to sickle cell disease, particularly the high morbidity and mortality seen in these patients, Dr. Freiermuth said.

“The median lifespan for patients with HbSS disease is in the 40s, basically half of the lifespan of a typical American,” she said.

At present, acute chest syndrome is the principal cause of death in patients with sickle cell disease, and most frequently occurs during a vasoocclusive episode. As a result, screening for this complication is essential to reduce mortality in the emergency setting.

Dr. Freiermuth explained that one of the best ways to prevent acute chest syndrome is to encourage the use of incentive spirometry in patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode.

In order to increase the likelihood of obtaining intravenous access, the use of ultrasound may help guide placement. Educating nurses on the proper use of ultrasound-guided placement of intravenous catheters is one practical approach, she said.

Alternatively, opioid analgesia can be administered subcutaneously. Benefits of subcutaneous delivery include comparable pharmacokinetics, less pain, and a reduced likelihood of sterile abscesses that are often seen with intramuscular administration.

Dr. Freiermuth outlined the quality-improvement initiative being tested at her institution, which involves the administration of parenteral opioid therapy during triage for sickle cell patients undergoing a suspected vasoocclusive crisis. The initiative was developed with input from both the emergency and hematology departments at the site.

Early results have shown no significant changes using this approach, but the data is still preliminary. Initial feedback has revealed that time to room placement has been the greatest barrier, she reported.

Dr. Tanabe reported grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Freiermuth reported research support from Pfizer.

Several initiatives are in the works to improve the management of patients with sickle cell disease in the ED, experts said at a recent webinar held by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In 2014, the NHLBI released evidence-based guidelines for the management of patients with sickle cell disease. The expert panel provided recommendations on the treatment of acute complications of sickle cell disease, many of which are common reasons for ED visits.

Optimizing the treatment of acute complications, namely vasoocclusive crisis, is essential to ensure improved long-term outcomes, explained Paula Tanabe, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Pain management

While the majority of pain-related ED visits in sickle cell are the result of vasoocclusive crisis, other causes, such as acute chest syndrome, abdominal catastrophes, and splenic sequestration, are also important.

The hallmark of pain management in this population is rapid and aggressive treatment with intravenous opioids. The use of individualized doses is also important, but if not available, an sickle cell disease–specific pain protocol can be used, she explained.

Recent evidence has confirmed the benefit of using an individualized (patient-specific) dosing protocol. Dr. Tanabe reported the results of a randomized pilot study that compared two pain protocols for patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode in the ED.

“The reason we pursued this project is to generate additional evidence beyond the expert panel,” she said.

The primary outcome of the study was the difference in pain scores from arrival to discharge between patients receiving an individualized or weight-based dosing protocol. Secondary outcomes included safety, pain experience, and side effects, among others.

The researchers found that patients who received an individualized protocol had significantly lower pain scores, compared with a standard weight-based protocol (between-protocol pain score difference, 15.6 plus or minus 5.0; P = .002).

Additionally, patients in the individualized dosing arm were admitted less often than those in the weight-based arm (P = .03), Dr. Tanabe reported.

The findings from the previous study formed the basis for an ongoing study that is further examining the impact of patient-specific dosing in patients who present with a vasoocclusive episode. The COMPARE VOE study is currently enrolling patients and is being funded by NHLBI.

The NHLBI also provides funding to eight Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium sites throughout the United States. The objective of this grant funding is to help implement NHLBI recommendations in the emergency setting.

Quality improvement

“One area [that] we want to improve is how quickly we administer [analgesic therapy] to patients when they are experiencing a vasoocclusive episode,” said Caroline Freiermuth, MD, of the University of Cincinnati.

Some common barriers to delivering rapid analgesia in this setting include difficulties in obtaining intravenous access, high patient volumes, lack of education, and provider biases, she explained.

With respect to high patient volumes, one strategy that may help overcome this barrier is to triage patients as Emergency Severity Index level 2, allowing for accelerated room placement.

Sickle cell patients undergoing vasoocclusive crisis meet the criteria for level 2 based on morbidity, degree of pain, and the level of resources often required.

Another important strategy is improving education related to sickle cell disease, particularly the high morbidity and mortality seen in these patients, Dr. Freiermuth said.

“The median lifespan for patients with HbSS disease is in the 40s, basically half of the lifespan of a typical American,” she said.

At present, acute chest syndrome is the principal cause of death in patients with sickle cell disease, and most frequently occurs during a vasoocclusive episode. As a result, screening for this complication is essential to reduce mortality in the emergency setting.

Dr. Freiermuth explained that one of the best ways to prevent acute chest syndrome is to encourage the use of incentive spirometry in patients undergoing a vasoocclusive episode.

In order to increase the likelihood of obtaining intravenous access, the use of ultrasound may help guide placement. Educating nurses on the proper use of ultrasound-guided placement of intravenous catheters is one practical approach, she said.

Alternatively, opioid analgesia can be administered subcutaneously. Benefits of subcutaneous delivery include comparable pharmacokinetics, less pain, and a reduced likelihood of sterile abscesses that are often seen with intramuscular administration.

Dr. Freiermuth outlined the quality-improvement initiative being tested at her institution, which involves the administration of parenteral opioid therapy during triage for sickle cell patients undergoing a suspected vasoocclusive crisis. The initiative was developed with input from both the emergency and hematology departments at the site.

Early results have shown no significant changes using this approach, but the data is still preliminary. Initial feedback has revealed that time to room placement has been the greatest barrier, she reported.

Dr. Tanabe reported grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Freiermuth reported research support from Pfizer.

REPORTING FROM AN NIH WEBINAR

A few pearls can help prepare the mind

We need to recognize the diverse problems that patients with potential multisystem disease can develop, lobby when necessary for them to be seen promptly by the relevant specialists, and initiate appropriate diagnostic testing and management in less-urgent scenarios. Most of us need frequent refreshers on the clinical manifestations of these disorders so that we can recognize them when they appear unannounced in our exam rooms.

The caregiver with a prepared mind is more likely to experience the diagnostic epiphany, and then use point-of-care references to hone in on the details. With many patients and clinical conundrums, the basics matter.

Dr. Chester Oddis, in this issue of the Journal, reviews the basics of several primary muscle disorders. He discusses, in a case-based format extracted from his recent Medicine Grand Rounds presentation at Cleveland Clinic, nuances of specific diagnoses and the clinical progression of diseases that are critical to be aware of in order to recognize and manage them, and expeditiously refer the patient to our appropriate subspecialty colleagues.

Major challenges exist in recognizing the inflammatory myopathies and their mimics early in their course. These are serious but uncommon entities, and in part because patients and physicians often attribute their early symptoms to more-common causes, diagnosis can be elusive—until the possibility is considered. We hope that Dr. Oddis’s article will make it easier to rapidly recognize these muscle disorders.

Patients often struggle to explain their symptoms of early muscle dysfunction. Since patients often verbalize their fatigue as “feeling weak,” we often misconstrue complaints of true muscle weakness (like difficulty walking up steps) as being due to fatigue. Add in some anemia from chronic inflammation and some “liver test” abnormalities, and it is easy to see how the recognition of true muscle weakness can be delayed.

We can tease muscle weakness from fatigue or dyspnea by asking the patient to specifically and functionally describe their “weakness,” and then by asking pointed questions: “Do you have difficulty getting up from the toilet without using your arms? Do you have trouble brushing your hair or teeth?” Physical examination can clearly help here, but without routine examination of muscle strength in normal fragile elderly patients, the degree of muscle weakness can be difficult to assess. Likewise challenging is detecting the early onset of weakness by examination in a 280-lb power-lifter.

Obtaining an accurate functional and behavioral history is often critical to the early recognition of muscle disease. Muscle pain, as Dr. Oddis notes, is not a characteristic feature of many myopathies, whereas, paradoxically, the coexistence of new-onset symmetrical small-joint pain (especially with arthritis) along with muscle weakness can be a powerful clue to the diagnosis of an inflammatory myopathy.

An elevated creatine kinase (CK) level generally points directly to a muscle disease, although some neurologic disorders are associated with elevations in CK, and the entity of benign “hyperCKemia” must be recognized and not overmanaged. The latter becomes a problem when laboratory tests are allowed to drive the diagnostic evaluation in a vacuum of clinical details.

A more common scenario is the misinterpretation of common laboratory test abnormalities in the setting of a patient with “fatigue” or generalized weakness who has elevations in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Although AST and ALT are often called “liver function tests,” these enzymes are also abundant in skeletal muscle, and since they are included on routine biochemical panels, their elevation often leads to liver imaging and sometimes even biopsy before anyone recognizes muscle disease as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and laboratory test abnormalities. Hence, a muscle source (or hemolysis) should at least be considered when AST and ALT are elevated in the absence of elevated alkaline phosphatase or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

When evaluating innumerable clinical scenarios, experienced clinicians can most certainly generate similar principles of diagnostic reasoning, based on having a few fundamental facts at their fingertips. Increasing the chances of having a prepared mind when confronted with a patient with a less-than-straightforward set of symptoms is one of my major arguments in support of continuing to read and generate internal medicine teaching literature and to attend and participate in clinical teaching conferences such as Medicine Grand Rounds. It is also why we will continue to appreciate and publish presentations like this one in the Journal.

I don’t expect to retain all the details from these and similar papers, and I know we all carry virtually infinite databases in our pockets. But keeping a few clinical pearls outside of my specialty in my head comes in handy. Having a prepared mind makes it much easier to converse with patients, to promptly initiate appropriate testing, plans, and consultations, and to then decide what to search for on my smartphone between patients.

We need to recognize the diverse problems that patients with potential multisystem disease can develop, lobby when necessary for them to be seen promptly by the relevant specialists, and initiate appropriate diagnostic testing and management in less-urgent scenarios. Most of us need frequent refreshers on the clinical manifestations of these disorders so that we can recognize them when they appear unannounced in our exam rooms.

The caregiver with a prepared mind is more likely to experience the diagnostic epiphany, and then use point-of-care references to hone in on the details. With many patients and clinical conundrums, the basics matter.

Dr. Chester Oddis, in this issue of the Journal, reviews the basics of several primary muscle disorders. He discusses, in a case-based format extracted from his recent Medicine Grand Rounds presentation at Cleveland Clinic, nuances of specific diagnoses and the clinical progression of diseases that are critical to be aware of in order to recognize and manage them, and expeditiously refer the patient to our appropriate subspecialty colleagues.

Major challenges exist in recognizing the inflammatory myopathies and their mimics early in their course. These are serious but uncommon entities, and in part because patients and physicians often attribute their early symptoms to more-common causes, diagnosis can be elusive—until the possibility is considered. We hope that Dr. Oddis’s article will make it easier to rapidly recognize these muscle disorders.

Patients often struggle to explain their symptoms of early muscle dysfunction. Since patients often verbalize their fatigue as “feeling weak,” we often misconstrue complaints of true muscle weakness (like difficulty walking up steps) as being due to fatigue. Add in some anemia from chronic inflammation and some “liver test” abnormalities, and it is easy to see how the recognition of true muscle weakness can be delayed.

We can tease muscle weakness from fatigue or dyspnea by asking the patient to specifically and functionally describe their “weakness,” and then by asking pointed questions: “Do you have difficulty getting up from the toilet without using your arms? Do you have trouble brushing your hair or teeth?” Physical examination can clearly help here, but without routine examination of muscle strength in normal fragile elderly patients, the degree of muscle weakness can be difficult to assess. Likewise challenging is detecting the early onset of weakness by examination in a 280-lb power-lifter.

Obtaining an accurate functional and behavioral history is often critical to the early recognition of muscle disease. Muscle pain, as Dr. Oddis notes, is not a characteristic feature of many myopathies, whereas, paradoxically, the coexistence of new-onset symmetrical small-joint pain (especially with arthritis) along with muscle weakness can be a powerful clue to the diagnosis of an inflammatory myopathy.

An elevated creatine kinase (CK) level generally points directly to a muscle disease, although some neurologic disorders are associated with elevations in CK, and the entity of benign “hyperCKemia” must be recognized and not overmanaged. The latter becomes a problem when laboratory tests are allowed to drive the diagnostic evaluation in a vacuum of clinical details.

A more common scenario is the misinterpretation of common laboratory test abnormalities in the setting of a patient with “fatigue” or generalized weakness who has elevations in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Although AST and ALT are often called “liver function tests,” these enzymes are also abundant in skeletal muscle, and since they are included on routine biochemical panels, their elevation often leads to liver imaging and sometimes even biopsy before anyone recognizes muscle disease as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and laboratory test abnormalities. Hence, a muscle source (or hemolysis) should at least be considered when AST and ALT are elevated in the absence of elevated alkaline phosphatase or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

When evaluating innumerable clinical scenarios, experienced clinicians can most certainly generate similar principles of diagnostic reasoning, based on having a few fundamental facts at their fingertips. Increasing the chances of having a prepared mind when confronted with a patient with a less-than-straightforward set of symptoms is one of my major arguments in support of continuing to read and generate internal medicine teaching literature and to attend and participate in clinical teaching conferences such as Medicine Grand Rounds. It is also why we will continue to appreciate and publish presentations like this one in the Journal.

I don’t expect to retain all the details from these and similar papers, and I know we all carry virtually infinite databases in our pockets. But keeping a few clinical pearls outside of my specialty in my head comes in handy. Having a prepared mind makes it much easier to converse with patients, to promptly initiate appropriate testing, plans, and consultations, and to then decide what to search for on my smartphone between patients.

We need to recognize the diverse problems that patients with potential multisystem disease can develop, lobby when necessary for them to be seen promptly by the relevant specialists, and initiate appropriate diagnostic testing and management in less-urgent scenarios. Most of us need frequent refreshers on the clinical manifestations of these disorders so that we can recognize them when they appear unannounced in our exam rooms.

The caregiver with a prepared mind is more likely to experience the diagnostic epiphany, and then use point-of-care references to hone in on the details. With many patients and clinical conundrums, the basics matter.

Dr. Chester Oddis, in this issue of the Journal, reviews the basics of several primary muscle disorders. He discusses, in a case-based format extracted from his recent Medicine Grand Rounds presentation at Cleveland Clinic, nuances of specific diagnoses and the clinical progression of diseases that are critical to be aware of in order to recognize and manage them, and expeditiously refer the patient to our appropriate subspecialty colleagues.

Major challenges exist in recognizing the inflammatory myopathies and their mimics early in their course. These are serious but uncommon entities, and in part because patients and physicians often attribute their early symptoms to more-common causes, diagnosis can be elusive—until the possibility is considered. We hope that Dr. Oddis’s article will make it easier to rapidly recognize these muscle disorders.

Patients often struggle to explain their symptoms of early muscle dysfunction. Since patients often verbalize their fatigue as “feeling weak,” we often misconstrue complaints of true muscle weakness (like difficulty walking up steps) as being due to fatigue. Add in some anemia from chronic inflammation and some “liver test” abnormalities, and it is easy to see how the recognition of true muscle weakness can be delayed.

We can tease muscle weakness from fatigue or dyspnea by asking the patient to specifically and functionally describe their “weakness,” and then by asking pointed questions: “Do you have difficulty getting up from the toilet without using your arms? Do you have trouble brushing your hair or teeth?” Physical examination can clearly help here, but without routine examination of muscle strength in normal fragile elderly patients, the degree of muscle weakness can be difficult to assess. Likewise challenging is detecting the early onset of weakness by examination in a 280-lb power-lifter.

Obtaining an accurate functional and behavioral history is often critical to the early recognition of muscle disease. Muscle pain, as Dr. Oddis notes, is not a characteristic feature of many myopathies, whereas, paradoxically, the coexistence of new-onset symmetrical small-joint pain (especially with arthritis) along with muscle weakness can be a powerful clue to the diagnosis of an inflammatory myopathy.

An elevated creatine kinase (CK) level generally points directly to a muscle disease, although some neurologic disorders are associated with elevations in CK, and the entity of benign “hyperCKemia” must be recognized and not overmanaged. The latter becomes a problem when laboratory tests are allowed to drive the diagnostic evaluation in a vacuum of clinical details.

A more common scenario is the misinterpretation of common laboratory test abnormalities in the setting of a patient with “fatigue” or generalized weakness who has elevations in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Although AST and ALT are often called “liver function tests,” these enzymes are also abundant in skeletal muscle, and since they are included on routine biochemical panels, their elevation often leads to liver imaging and sometimes even biopsy before anyone recognizes muscle disease as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and laboratory test abnormalities. Hence, a muscle source (or hemolysis) should at least be considered when AST and ALT are elevated in the absence of elevated alkaline phosphatase or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

When evaluating innumerable clinical scenarios, experienced clinicians can most certainly generate similar principles of diagnostic reasoning, based on having a few fundamental facts at their fingertips. Increasing the chances of having a prepared mind when confronted with a patient with a less-than-straightforward set of symptoms is one of my major arguments in support of continuing to read and generate internal medicine teaching literature and to attend and participate in clinical teaching conferences such as Medicine Grand Rounds. It is also why we will continue to appreciate and publish presentations like this one in the Journal.

I don’t expect to retain all the details from these and similar papers, and I know we all carry virtually infinite databases in our pockets. But keeping a few clinical pearls outside of my specialty in my head comes in handy. Having a prepared mind makes it much easier to converse with patients, to promptly initiate appropriate testing, plans, and consultations, and to then decide what to search for on my smartphone between patients.

Myopathy for the general internist: Statins and much more

Myopathies can present with a wide variety of symptoms, so patients with muscle weakness are often seen initially by a general practitioner. Nonrheumatologists should be able to evaluate a patient presenting with muscle weakness or myalgia and be aware of red flags indicating potentially dangerous syndromes that require a prompt, thorough investigation.

This article reviews selected causes of muscle weakness, such as statin-induced and autoimmune disorders, and systemic features of inflammatory myopathies beyond myositis, such as dermatologic and pulmonary manifestations.

FOCUSING THE EVALUATION

The evaluation of a patient presenting with muscle weakness should include several assessments:

Temporal progression. Was the onset of symptoms rapid or insidious? Patterns of onset may give clues to etiology, including the possibility of an associated autoimmune condition.

Location of muscle weakness. Are symptoms global or localized? And if localized, are they proximal or distal? Proximal weakness can be manifested by difficulty rising from a chair (hip muscles) or combing one’s hair (shoulder muscles), whereas distal weakness can involve difficulty standing on toes (gastrocnemius and soleus muscles) or performing fine motor activities (intrinsic hand muscles).

Symmetry. A focal or asymmetric pattern often has a neurologic etiology, but this could also be consistent with inclusion body myositis.

Other symptoms. Arthritis, rash, and swallowing problems point to a possible underlying rheumatologic disease. Weight gain or loss may indicate a thyroid disorder.

Family history. Some patients report that others in their family have this pattern of weakness, indicating a likely genetic myopathy. If the patient reports a relative with multiple sclerosis, lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, or another autoimmune disease, then an immune-mediated myopathy should be considered.

Medications should be reviewed, particularly statins.

CASE 1: SLOWLY PROGRESSIVE WEAKNESS

A 65-year-old man presented with the insidious onset of muscle weakness and episodes of falling. On review of his medical record, his serum creatine kinase (CK) levels were elevated at various periods at 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal. Electromyography (EMG) previously showed a myopathic pattern, and a muscle biopsy was abnormal, consistent with endomysial inflammation (term is consistent with “polymyositis”). He was treated for polymyositis for several years with prednisone alone, with steroids plus methotrexate, and with combined immunosuppression including methotrexate and azathioprine, but with no improvement. Eventually, another muscle biopsy revealed inclusion bodies with rimmed vacuoles, consistent with inclusion body myositis.

Inclusion body myositis

Inclusion body myositis is the most common myopathy in middle-aged to elderly people, especially men. These patients are often told “You are just getting old,” but they have a defined condition. It should also be considered in patients failing to respond to treatment or with those with “refractory” polymyositis.

The onset of muscle weakness is insidious and painless, and the weakness progresses slowly. The pattern is distal and asymmetric (eg, foot drop), and muscle atrophy typically affects the forearm flexors, quadriceps, and intrinsic muscles of the hands.1

Magnetic resonance imaging may show marked muscle atrophy. Unfortunately, no treatment has shown efficacy, and most neuromuscular and rheumatology experts do not treat inclusion body myositis with immunosuppressive drugs.

CASE 2: MILD MYALGIA WITHOUT WEAKNESS

A black 52-year-old man was referred because of myalgia and a CK level of 862 U/L (reference range < 200). His physician wanted to start him on a statin but was hesitant to do so without first consulting a rheumatologist.

The patient had a long history of mild arthralgias and myalgias without muscle weakness. He had dyslipidemia and hypertension. He reported no family history of myopathy and no illicit drug use. He was formerly an athlete. Medications included a thiazide diuretic and a beta-blocker. On examination, his muscles were strong (rated 5 on a scale of 5) in the upper and lower extremities, without atrophy.

His records showed that his CK levels had risen and fallen repeatedly over the past few years, ranging from 600 to 1,100 U/L. On further questioning, he reported that when he had joined the army 30 years previously, a physician had recommended he undergo a liver biopsy in view of elevated liver function tests, but that he had refused because he felt fine.

Currently, his gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels were normal.

Idiopathic ‘hyperCKemia’

So-called idiopathic hyperCKemia is not a form of myositis but merely a laboratory result outside the “normal” range. Reference ranges are based predominantly on measurements in white people and on an assumption that the distribution is Gaussian (bell-shaped). A normal CK level is usually defined as less than 200 U/L. Using this standard, up to 20% of men and 5% of women have hyperCKemia.2

However, CK levels vary by sex and ethnicity, with mean levels highest in black men, followed by black women, white men, and white women. The mean level in black men is higher than the standard cutoff point for normal, and especially in this population, there is wide fluctuation around the mean, leading to hyperCKemia quite frequently in black men. Exercise and manual labor also drive up CK levels.3–5

Idiopathic hyperCKemia is benign. D’Adda et al6 followed 55 patients for a mean of 7.5 years. CK levels normalized in 12 patients or at least decreased in 24. Most remained symptom-free or had minimal symptoms.

Idiopathic hyperCKemia: Bottom line

Before prescribing a statin, determine the baseline CK level. If slightly elevated (ie, up to 3 to 5 times the upper limit of normal, or even higher) in the setting of normal muscle strength, there is no need for electromyography or muscle biopsy, and the patient can certainly receive a statin. Most of these patients do not need to see a rheumatologist but can simply have their CK and muscle strength monitored.

CLASSIFYING MYOSITIS

Myositis (idiopathic inflammatory myopathy) is a heterogeneous group of autoimmune syndromes of unknown cause characterized by chronic muscle weakness and inflammation of striated muscle. These syndromes likely arise as a result of genetic predisposition and an environmental or infectious “hit.”

Myositis is rare, with an incidence of 5 to 10 cases per million per year and an estimated prevalence of 50 to 90 cases per million. It has 2 incidence peaks: 1 in childhood (age 5–15) and another in adult midlife (age 30–50). Women are affected 2 to 3 times more often than men, with black women most commonly affected.

Myositis is traditionally classified as follows:

- Adult polymyositis

- Adult dermatomyositis

- Juvenile myositis (dermatomyositis much more frequent than polymyositis)

- Malignancy-associated myositis (usually dermatomyositis)

- Myositis overlapping with another autoimmune disease

- Inclusion body myositis.

However, polymyositis is less common than we originally thought, and the term necrotizing myopathy is now used in many patients, as noted in the case studies below. Further, myositis overlap syndromes are being increasingly diagnosed, likely related to the emergence of autoantibodies and clinical “syndromes” associated with these autoantibody subsets (discussed in cases below).

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is characterized by muscle weakness and a rash that can be obvious or subtle. Classic skin lesions are Gottron papules, which are raised, flat-topped red or purplish lesions over the knuckles, elbows, or knees.

Lesions may be confused with those of psoriasis. There can also be a V-neck rash over the anterior chest or upper back (“shawl sign”) or a rash over the lateral thigh (“holster sign”). A facial rash may occur, but unlike lupus, dermatomyositis does not spare the nasolabial area. However, the V-neck rash can be similar to that seen in lupus.

Dermatomyositis may cause muscle pain, perhaps related to muscle ischemia, whereas polymyositis and necrotizing myopathy are often painless. However, pain is also associated with fibromyalgia, which may be seen in many autoimmune conditions. It is important not to overtreat rheumatologic diseases with immunosuppression to try to control pain if the pain is actually caused by fibromyalgia.

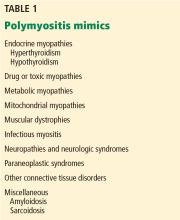

Polymyositis mimics

Hypothyroid myopathy can present as classic polymyositis. The serum CK may be elevated, and there may be myalgias, muscle hypertrophy with stiffness, weakness, cramps, and even features of a proximal myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis. The electromyogram can be normal or myopathic. Results of muscle biopsy are often normal but may show focal necrosis and mild inflammatory infiltrates, thus mimicking that seen with inflammatory myopathy.7

Drug-induced or toxic myopathies can also mimic polymyositis. Statins are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States, with more than 35 million people taking them. Statins are generally well tolerated but have a broad spectrum of toxicity, ranging from myalgias to life-threatening rhabdomyolysis. Myalgias lead to about 5% to 10% of patients refusing to take a statin or stopping it on their own.

Myalgias affect up to 20% of statin users in clinical practice.8,9 A small cross-sectional study10 of 1,000 patients in a primary care setting found that the risk of muscle complaints in statin users was 1.5 times higher than in nonstatin users, similar to findings in other studies.

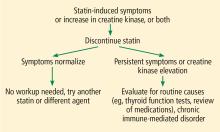

My strategy for managing a patient with possible statin-induced myopathy is illustrated in Figure 1.

CASE 3: WEAKNESS, VERY HIGH CK ON A STATIN

In March 2010, a 67-year-old woman presented with muscle weakness. She had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and, more than 10 years previously, uterine cancer. In 2004, she was given atorvastatin for dyslipidemia. Four years later, she developed lower-extremity weakness, which her doctor attributed to normal aging. A year after that, she found it difficult to walk up steps and lift her arms overhead. In June 2009, she stopped taking the atorvastatin on her own, but the weakness did not improve.

In September 2009, she returned to her doctor, who found her CK level was 6,473 U/L but believed it to be an error, so the test was repeated, with a result of 9,375 U/L. She had no rash or joint involvement.

She was admitted to the hospital and underwent muscle biopsy, which showed myonecrosis with no inflammation or vasculitis. She was treated with prednisone 60 mg/day, and her elevated CK level and weakness improved.

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins

The hallmark of necrotizing myopathy is myonecrosis without significant inflammation.12 This pattern contrasts with that of polymyositis, which is characterized by lymphocytic inflammation.

Although statins became available in the United States in 1987, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins was first described only in 2010. In that report, Grable-Esposito et al13 described 25 patients from 2 neuromuscular centers seen between 2000 and 2008 who had elevated CK and proximal weakness during or after statin use, both of which persisted despite stopping the statin. Patients improved with immunosuppressive agents but had a relapse when steroids were stopped or tapered, a pattern typical in autoimmune disease.

Autoantibody defines subgroup of necrotizing myopathy

Also in 2010, Christopher-Stine et al14 reported an antibody associated with necrotizing myopathy. Of 38 patients with the condition, 16 were found to have an abnormal “doublet” autoantibody recognizing 200- and 100-kDa proteins. All patients had weakness and a high CK level, and 63% had statin exposure before the weakness (this percentage increased to 83% in patients older than 50). All responded to immunosuppressive therapy, and many had a relapse when it was withdrawn.

Statins lower cholesterol by inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Co A reductase (HMGCR), and paradoxically, they also upregulate it. HMGCR has a molecular weight of 97 kDa. Mammen et al15 identified HMGCR as the 100-kDa target of the identified antibody and developed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for it. Of 750 patients presenting to one center, only 45 (6%) had anti-HMGCR autoantibodies, but all 16 patients who had the abnormal doublet antibody tested positive for anti-HMGCR. Regenerating muscle cells express high levels of HMGCR, which may sustain the immune response after statins are discontinued.

Case 3 continued: Intravenous immunoglobulin brings improvement

In March 2010, when the 67-year-old patient presented to our myositis center, her CK level was 5,800 U/L, which increased as prednisone was tapered. She still felt weak. On examination, her muscle strength findings were deltoids 4+/5, neck flexors 4/5, and iliopsoas 3+/5. She was treated with methotrexate and azathioprine without benefit. She was next treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, and after 3 months, her strength normalized for the first time in years. Her CK level decreased but did not normalize. Testing showed that she was positive for anti-HMGCR autoantibody, as this test had become commercially available.

In 2015, Mammen and Tiniakou16 suggested using intravenous immunoglobulin as first-line therapy for statin-associated autoimmune necrotizing myopathy, based on experience at a single center with 3 patients who declined glucocorticoid treatment.

Necrotizing myopathy: Bottom line

Myositis overlap syndromes

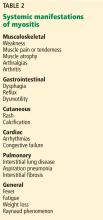

Heterogeneity is the rule in myositis, and it can present with a wide variety of signs and symptoms as outlined in Table 2.

CASE 4: FEVER, NEW ‘RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS,’ AND LUNG DISEASE

A 52-year-old woman with knee osteoarthritis saw her primary care physician in November 2013 for dyspnea and low-grade fever. The next month, she presented with polyarthritis, muscle weakness, and Raynaud phenomenon.

In January 2014, she developed acrocyanosis of her fingers. Examination revealed hyperkeratotic, cracked areas of her fingers. Her oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry was low. She was admitted to the hospital. Her doctor suspected new onset of rheumatoid arthritis, but blood tests revealed a negative antinuclear antibody, so an autoimmune condition was deemed unlikely. Her CK was mildly elevated at 350 U/L.

Because of her dyspnea, an open-lung biopsy was performed. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) revealed infiltrates and ground-glass opacities, leading to the diagnosis of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. A rheumatologist was consulted and recommended pulse methylprednisolone, followed by prednisone 60 mg/day and mycophenolate mofetil. Testing for Jo-1 antibodies was positive.

Antisynthetase syndrome

The antisynthetase syndrome is a clinically heterogeneous condition that can occur with any or all of the following:

- Fever

- Myositis

- Arthritis (often misdiagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis)

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Mechanic’s hands (hyperkeratotic roughness with fissures on the lateral aspects of the fingers and finger pads)

- Interstitial lung disease.

The skin rashes and myositis may be subtle, making the presentation “lung-dominant,” and nonrheumatologists should be aware of this syndrome. Although in our patient the condition developed in a classic manner, with all of the aforementioned features of the antisynthetase syndrome, some patients will manifest one or a few of the features.

Clinically, patients with the Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome often present differently than those with non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies. When we compared 122 patients with Jo-1 vs 80 patients with a non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibody, patients with Jo-1 antibodies were more likely to have initially received a diagnosis of myositis (83%), while myositis was the original diagnosis in only 17% of those possessing non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies. In fact, many patients (approximately 50%) were diagnosed as having undifferentiated connective tissue disease or an overlap syndrome, and 13% had scleroderma as their first diagnosis.17

We also found that the survival rate was higher in patients with Jo-1 syndrome compared with patients with non-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndromes. We attributed the difference in survival rates to a delayed diagnosis in the non-Jo-1 group, perhaps due to their “nonclassic” presentations of the antisynthetase syndrome, delaying appropriate treatment. Patients received a diagnosis of Jo-1 antibody syndrome after a mean of 0.4 year (range 0.2–0.8), while those with a non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibody had a delay in diagnosis of 1.0 year (range 0.4–5.1) (P < .01).17

In nearly half the cases in this cohort, pulmonary fibrosis was the cause of death, with primary pulmonary hypertension being the second leading cause (11%).

Antisynthetase syndrome: Bottom line

Antisynthetase syndrome is an often fatal disease that does not always present in a typical fashion with symptoms of myositis, as lung disease may be the predominant feature. A negative antinuclear antibody test result does not imply antibody negativity, as the autoantigen in these diseases is not located in the nucleus. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate immunosuppressive therapy are critical to improving outcomes.

CASE 5: FEVER, UNDIAGNOSED LUNG DISEASE, NO MYOSITIS

In January 2001, a 39-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital after 5 weeks of fever (temperatures 103°–104°F) and myalgias. An extensive workup was negative except for low-titer antinuclear antibody and for mild basilar fibrosis noted on chest radiography. She left the hospital against medical advice because of frustration with a lack of a specific diagnosis (“fever of unknown origin”).

Two months later, at a follow-up rheumatology consult, she reported more myalgias and arthralgias, as well as fever. Chest radiography now showed pleural effusions. Her fingers had color changes consistent with Raynaud phenomenon. At that time, I diagnosed an undifferentiated connective tissue disease and told her that I suspected an autoimmune condition that would need time to reveal itself. In the meantime, I treated her empirically with prednisone.

In April, she returned, much more short of breath and with more prominent diffuse pulmonary infiltrates. Physical examination revealed subtle Gottron changes. Testing revealed poor pulmonary function: forced vital capacity (FVC) 56%, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) 52%, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (Dlco) 40%. Blood testing was positive for anti-PL-12 antibody, one of the non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies. At this time, we treated her with glucocorticoids and tacrolimus.

More than 15 years later, this patient is doing well. Her skin rash, joint symptoms, and fever have not returned, and interestingly, she never developed myositis. Her Raynaud symptoms are mild. Her most recent pulmonary function test results (January 2018) were FVC 75%, FEV1 87%, and Dlco 78%. Although these results are not normal, they are much improved and allow her to be completely functional without supplemental oxygen. Echocardiography showed normal pulmonary artery systolic pressure (25 mm Hg). She was still taking tacrolimus and prednisone. When we tried to stop tacrolimus after she had done well for many years, her condition flared.

Non-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome: Bottom line