User login

How best to address breast pain in nonbreastfeeding women

CASE 1

Robin S is a 40-year-old woman who has never had children or been pregnant. She is in a relationship with a woman so does not use contraception. She has no family history of cancer. She presents with worsening bilateral breast pain that starts 10 days before the onset of her period. The pain has been present for about 4 years, but it has worsened over the last 6 months such that she is unable to wear a bra during these 10 days, finds lying in bed on her side too painful for sleep, and is unable to exercise. She has tried to eliminate caffeine from her diet and takes ibuprofen, but neither of these interventions has controlled her pain. Her breast exam is normal except for diffuse tenderness over both breasts.

CASE 2

Meg R is a 50-year-old healthy woman. She is a G2P2 who breastfed each of her children for 1 year. She does not smoke. She has no family history of breast cancer or other malignancies. She presents with 2 months of deep, left-sided breast pain. She describes the pain as constant, progressive, dull, and achy. She points to a spot in the upper outer quadrant of her left breast and describes the pain as being close to her ribs. She had a screening mammogram 3 weeks earlier that was normal, with findings of dense breasts. She did not tell the technician that she was having pain. Clinical breast examination of both breasts reveals tenderness to deep palpation of the left breast. She has dense breasts but a focal mass is not palpated.

Mastalgia, or breast pain, is one of the most common breast symptoms seen in primary care and a common reason for referrals to breast surgeons. Up to 70% of women will experience breast pain during their lifetime—most in their premenopausal years.1,2

The most common type of breast pain is cyclic (ie, relating to the menstrual cycle); it accounts for up to 70% of all cases of breast pain in women.1,3 The other 2 types of breast pain are noncyclic and extramammary. The cause of cyclic breast pain is unclear, but it is likely hormonally mediated and multifactorial. In the vast majority of women with breast pain, no distinct etiology is found, and there is a very low incidence of breast cancer.2,4

In this review, we describe how to proceed when a woman who is not breastfeeding presents with cyclic or noncyclic breast pain.

Evaluation: Focus on the pain, medications, and history

Evaluation of breast pain should begin with the patient describing the pain, including its quality, location, radiation, and relationship to the menstrual cycle. It’s important to inquire about recent trauma or aggravating activities and to order a pregnancy test for women of childbearing age.1

Cyclic mastalgia is typically described as diffuse, either unilateral or bilateral, with an aching or heavy quality. The pain is often felt in the upper outer quadrant of the breast with radiation to the axilla. It most commonly occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, improves with the onset of menses, and is thought to be related to the increased water content in breast stroma caused by increasing hormone levels during the luteal phase.5-7

Continue to: Noncyclic mastalgia

Noncyclic mastalgia is typically unilateral and localized within 1 quadrant of the breast; however, women may report diffuse pain with radiation to the axilla. The pain is often described as burning, achy, or as soreness.5,6 There can be considerable overlap in the presentations of cyclic and noncyclic pain and differentiating between the 2 is often not necessary as management is similar.8

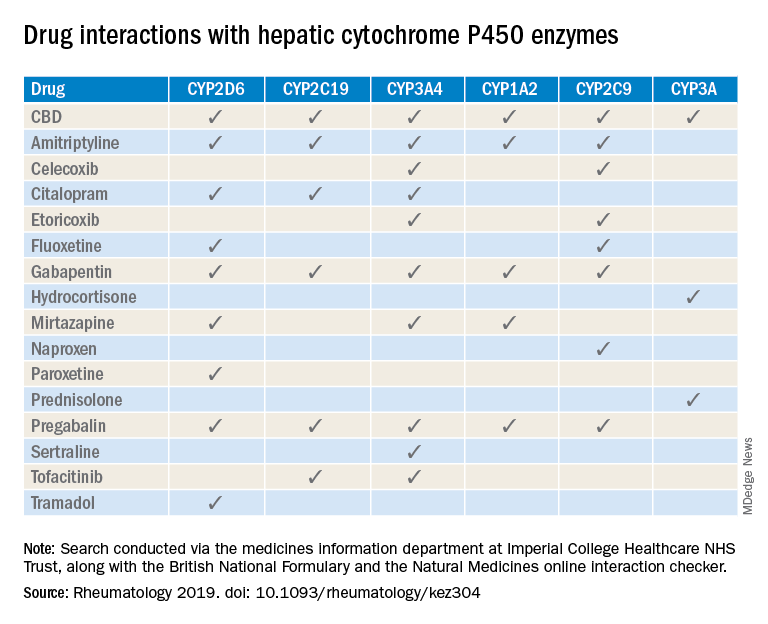

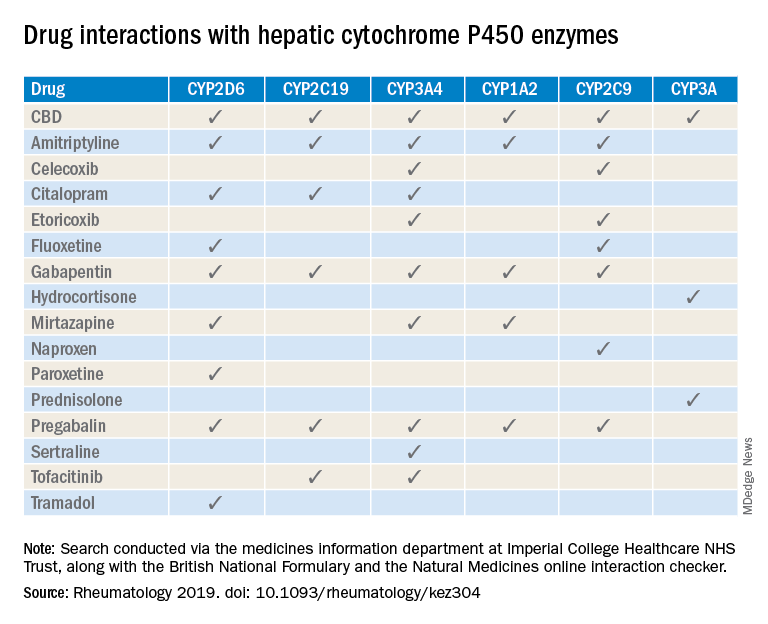

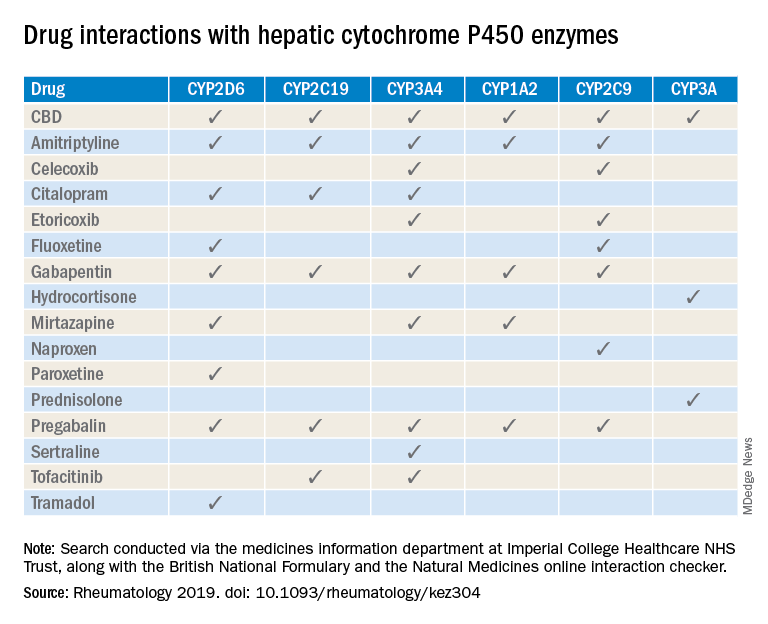

A thorough review of medications is important as several drugs have been associated with breast pain. These include oral contraceptives, hormone therapy, antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], venlafaxine, mirtazapine), antipsychotics (haloperidol), and some cardiovascular agents (spironolactone, digoxin).5

Inquiring about stress, caffeine intake, smoking status, and bra usage may also yield useful information. Increased stress and caffeine intake have been associated with mastalgia,7 and women who are heavy smokers are more likely to have noncyclic hypersensitive breast pain.9 In addition, women with large breasts often have noncyclic breast pain, particularly if they don’t wear a sufficiently supportive bra.3

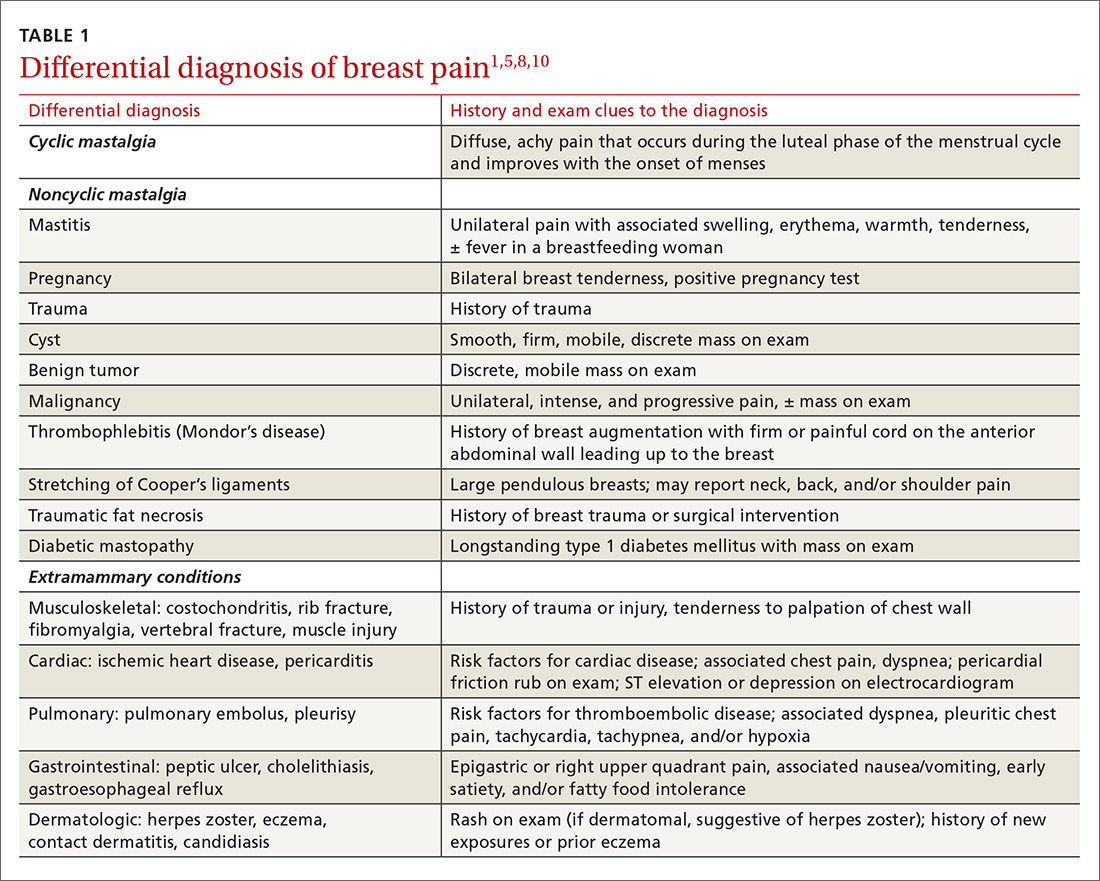

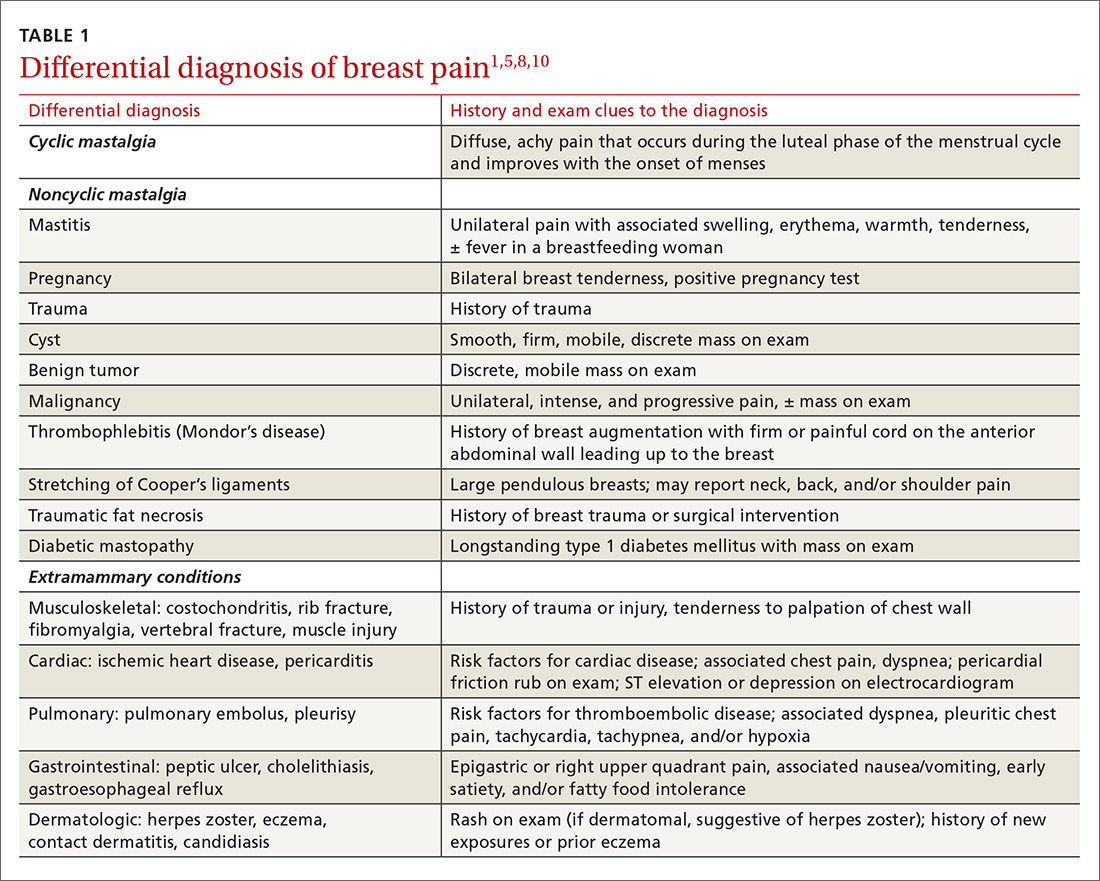

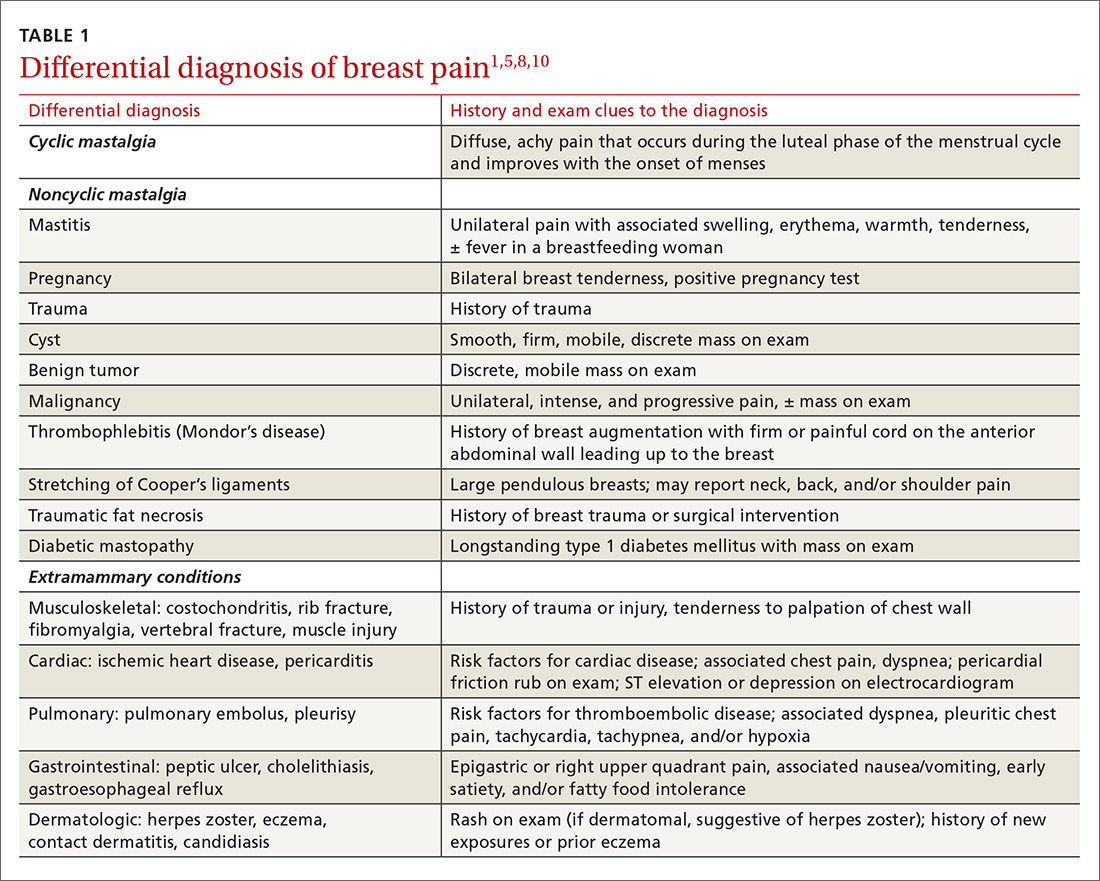

Medical, surgical, family history. Relevant aspects of a woman’s past medical, surgical, and family history include prior breast mass or biopsy, breast surgery, and risk factors associated with breast cancer (menarche age < 12 years, menopause age > 55 years, nulliparity, exposure to ionizing radiation, and family history of breast or ovarian cancer).1 A thorough history should include questions to evaluate for extra-mammary etiologies of breast pain such as those that are musculoskeletal or dermatologic in nature (TABLE 11,5,8,10).

Using an objective measure of pain is not only helpful for evaluating the pain itself, but also for determining the effectiveness of treatment strategies. When using the Cardiff Breast Pain Chart, for example, menstrual cycle and level of pain are recorded on a calendar (see www.breastcancercare.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/breast_pain_chart.pdf).11 If the pain is determined to be cyclic, the concern for malignancy is significantly lower.2

Continue to: Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Women presenting with breast pain should undergo a clinical breast exam in both the upright and supine positions. Inspect for asymmetry, erythema, rashes, skin dimpling, nipple discharge, and retraction/inversion. Palpate the breasts for any suspicious masses, asymmetry, or tenderness, as well as for axillary and/or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and chest wall tenderness. This is facilitated by having the patient lie in the lateral decubitus position, allowing the breast to fall away from the chest wall.5,12,13

Imaging: Preferred method depends on the age of the patient

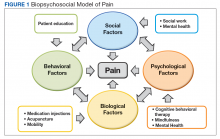

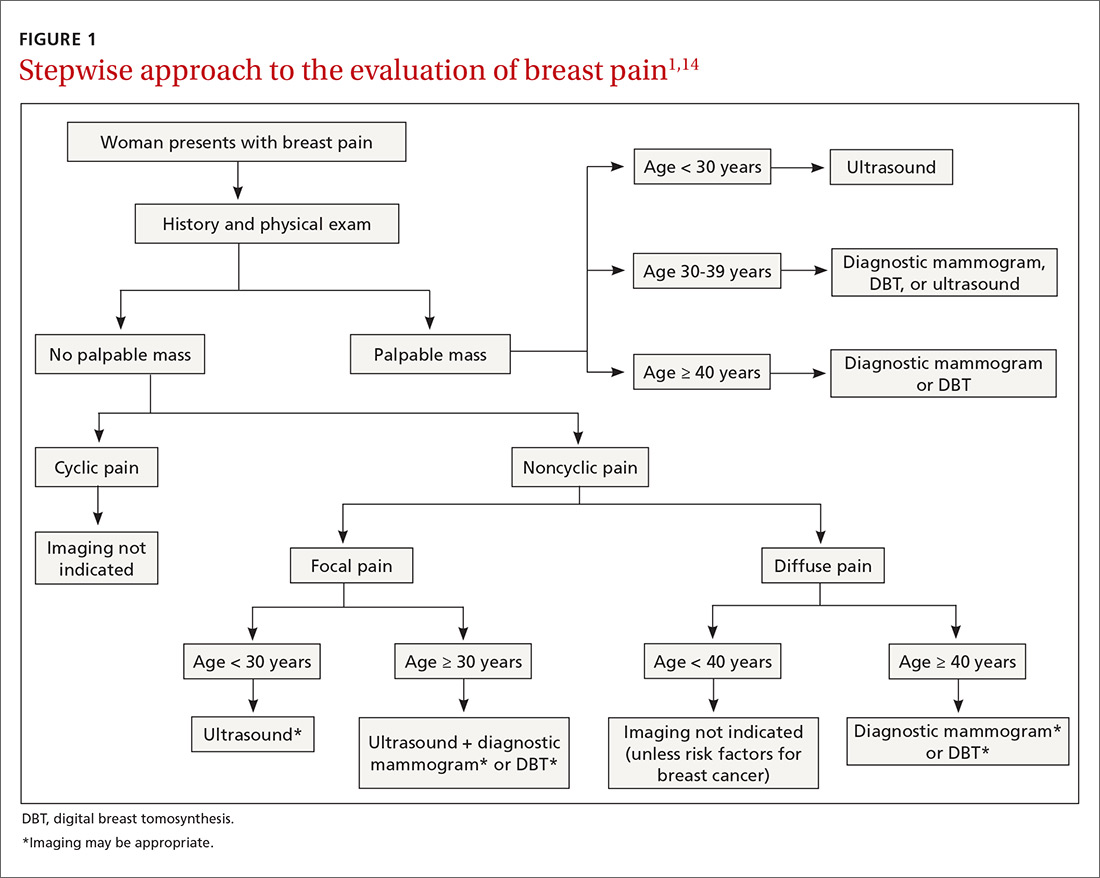

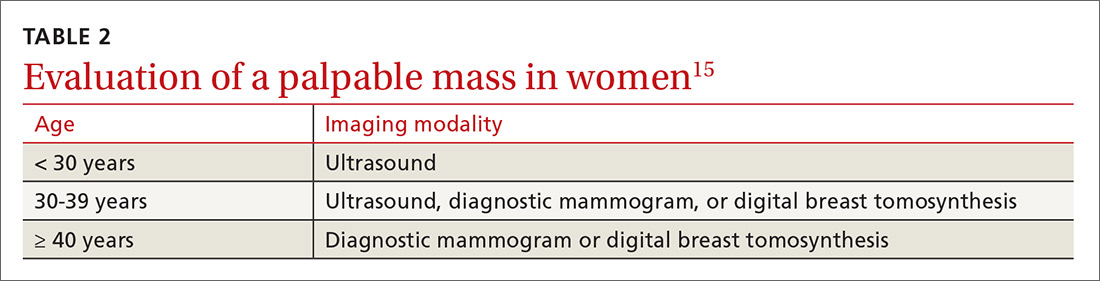

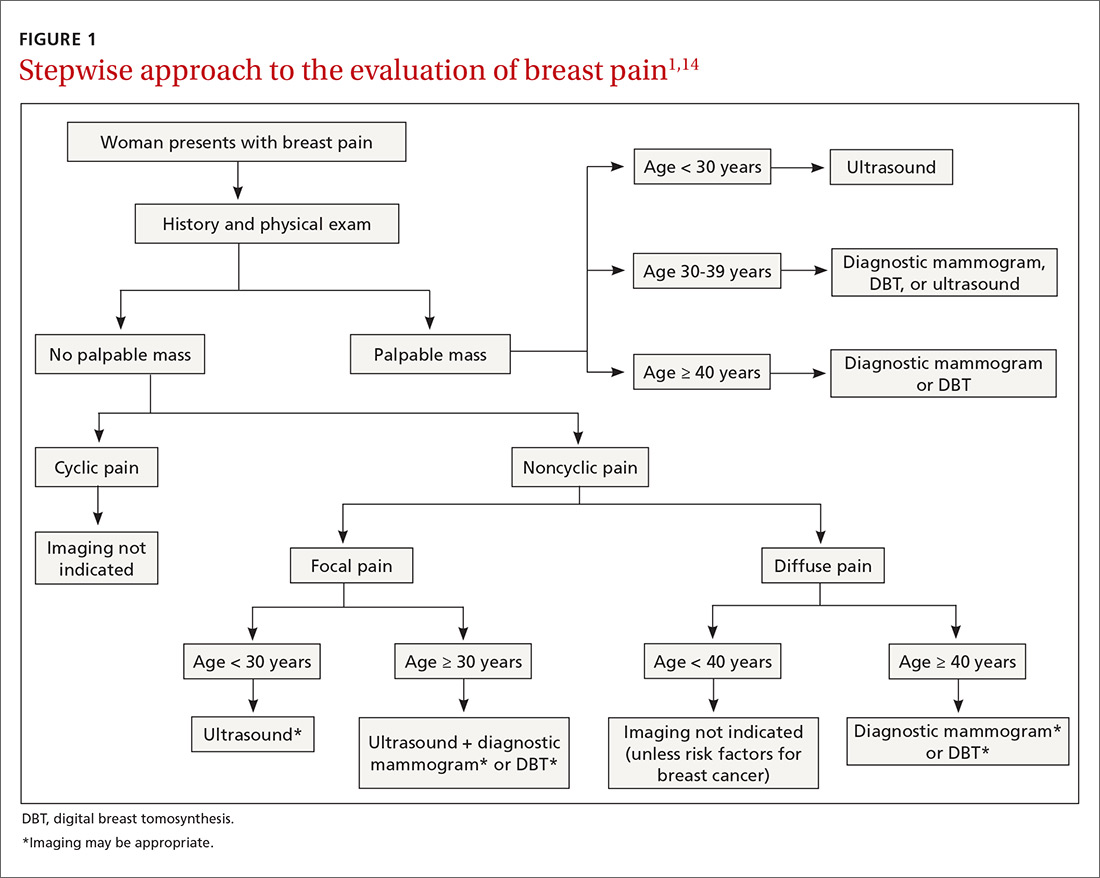

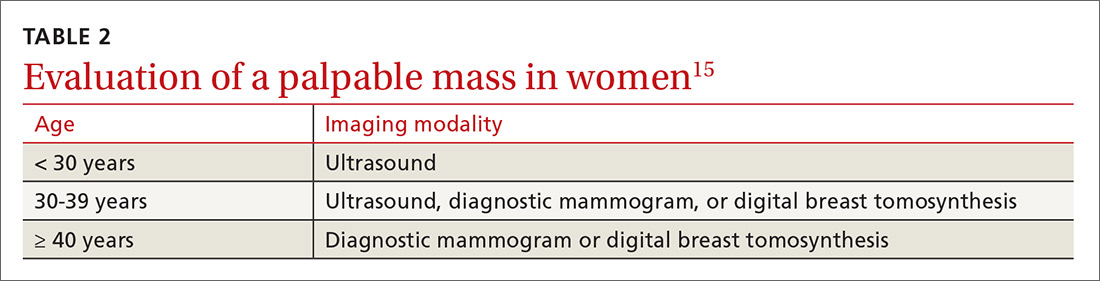

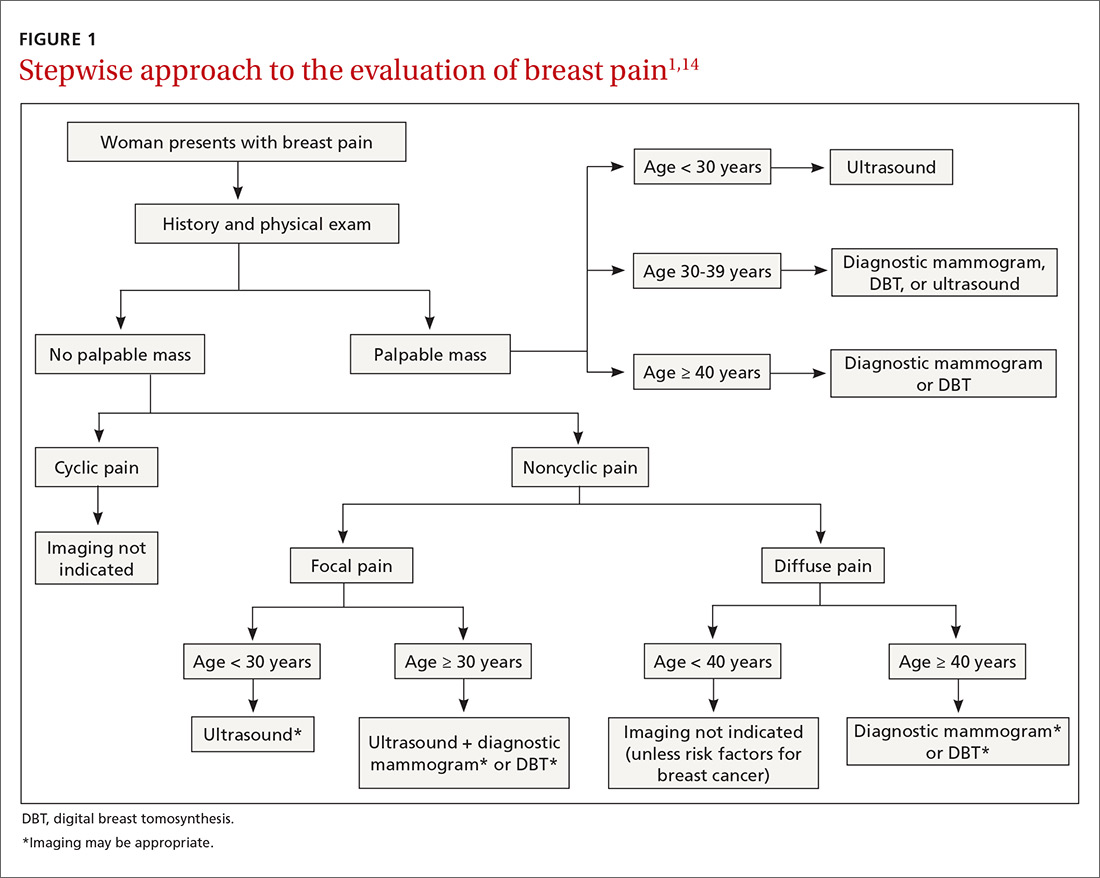

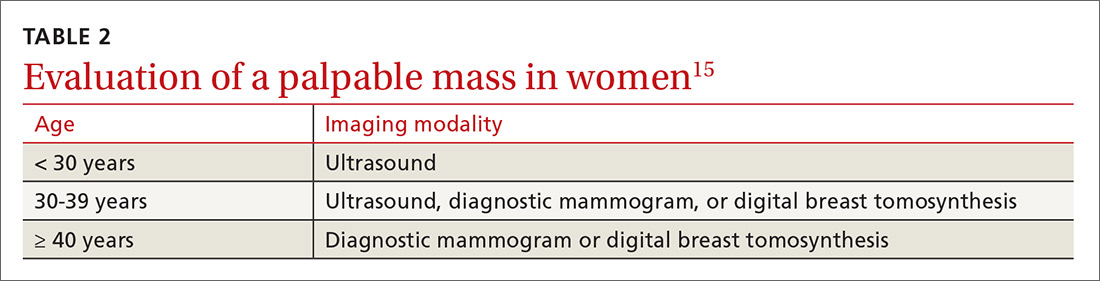

Women with a palpable mass should be referred for diagnostic imaging (FIGURE 11,14). Ultrasonography is the recommended modality for women < 30 years of age (TABLE 215). For women between the ages of 30 and 39 years, appropriate initial imaging includes ultrasound, diagnostic mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). For women ≥ 40 years of age, diagnostic mammography or DBT is recommended.15

Cyclic breast pain. Women with cyclic breast pain do not require further evaluation with imaging. Reassurance and symptomatic treatment is appropriate in most cases, as the risk of malignancy is very low in the absence of other concerning signs or symptoms. A screening mammogram may be appropriate for women > 40 years of age who have not had one in the preceding 12 months.1-3,10,12,15

Noncyclic breast pain. In contrast, imaging may be appropriate in women who present with noncyclic breast pain depending on the woman’s age and whether the pain is focal (≤ 25% of the breast and axillary tissue) or diffuse (> 25% of the breast and axillary tissue). Although evidence suggests that the risk of malignancy in women with noncyclic breast pain is low, the American College of Radiology advises that imaging may be useful in some patients to provide reassurance and to exclude a treatable cause of breast pain.3,14 In women with focal pain, ultrasound alone is the preferred modality for women < 30 years of age and ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography is recommended for women ≥ 30 years of age.3,14

In one small study, the use of ultrasonography in women ages < 30 years with focal breast pain had a sensitivity of 100% and a negative predictive value of 100%.16 Similarly, another small retrospective study in older women (average age 56 years) with focal breast pain and no palpable mass showed that ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography had a negative predictive value of 100%.4 DBT may be used in place of mammography to rule out malignancy in this setting.

Continue to: In general...

In general, routine imaging is not indicated for women with noncyclic diffuse breast pain, although diagnostic mammography or DBT may be considered in women ≥ 40 years of age 14 (see “Less common diagnoses with breast pain”4,5,17-21).

SIDEBAR

Less common diagnoses with breast pain

Many women presenting with breast pain are concerned about malignancy. Breast cancer is an uncommon cause of breast pain; only 0.5% of patients presenting with mastalgia without other clinical findings have a malignancy.4 Mastalgia is not a risk factor for breast cancer.

When mastalgia is associated with breast cancer, it is more likely to be unilateral, intense, noncyclic, and progressive.5 Concerning features that warrant further evaluation include new onset focal pain with or without an abnormal exam. If symptoms cannot be explained by an obvious cause (such as trauma, costochondritis, radicular back or intercostal pain, herpes zoster, or superficial thrombophlebitis that does not resolve), diagnostic breast imaging is indicated.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is an aggressive form of breast cancer that initially presents with breast pain and rapidly enlarging diffuse erythema of the breast in the absence of a discrete breast lump. The initial presentation is similar to that seen with benign inflammatory etiologies of the breast tissue like cellulitis or abscess, duct ectasia, mastitis, phlebitis of the thoracoepigastric vein (Mondor’s disease), or fat necrosis.17 Benign breast conditions due to these causes will generally resolve with appropriate treatment for those conditions within 7 days and will generally not present with the warning signs of IBC, which include a personal history of breast cancer, nonlactational status, and palpable axillary adenopathy. Although uncommon (accounting for 1%-6% of all breast cancer diagnoses), IBC spreads rapidly over a few weeks; thus, urgent imaging is warranted.17

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissue that may or may not be associated with a bacterial infection and uncommonly occurs in nonbreastfeeding women. Periductal mastitis is characterized by inflammation of the subareolar ducts and can present with pain, periareolar inflammation, and purulent nipple discharge.18 The condition is typically chronic, and the inflamed ducts may become secondarily infected leading to duct damage and abscess formation. Treatment generally includes antibiotics along with incision and drainage of any associated abscesses or duct excision.18,19

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a rare inflammatory breast disease that typically affects young parous women. The presentation can vary from a single peripheral breast mass to multiple areas of infection with abscesses and skin ulceration. The etiology is unknown. Diagnosis requires a core needle biopsy to rule out malignancy or other causes of granulomatous disease. IGM is a benign condition and typically resolves without treatment over the course of several months, although antibiotics and/or drainage may be required for secondary infections.20,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment: When reassurance isn’t enough

Nonrandomized studies suggest that reassurance that mastalgia is benign is enough to treat up to 70% of women.8,22,23 Cyclic breast pain is usually treated symptomatically since the likelihood of breast cancer is extremely low in absence of clinical breast examination abnormalities.2 Because treatment for cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia overlaps, available treatments are discussed together on the following pages.

Lifestyle factors associated with breast pain include stress, caffeine consumption, smoking, and having breastfed 3 or more children (P < .05).9 Although restriction of caffeine, fat, and salt intake may be attempted to address breast pain, no randomized control trials (RCTs) of these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing mastalgia.8,10

Although not supported by RCTs, first-line treatment of mastalgia includes a recommendation that women, particularly those with large, heavy breasts, wear a well-fitted and supportive bra.8,10

Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for mastalgia

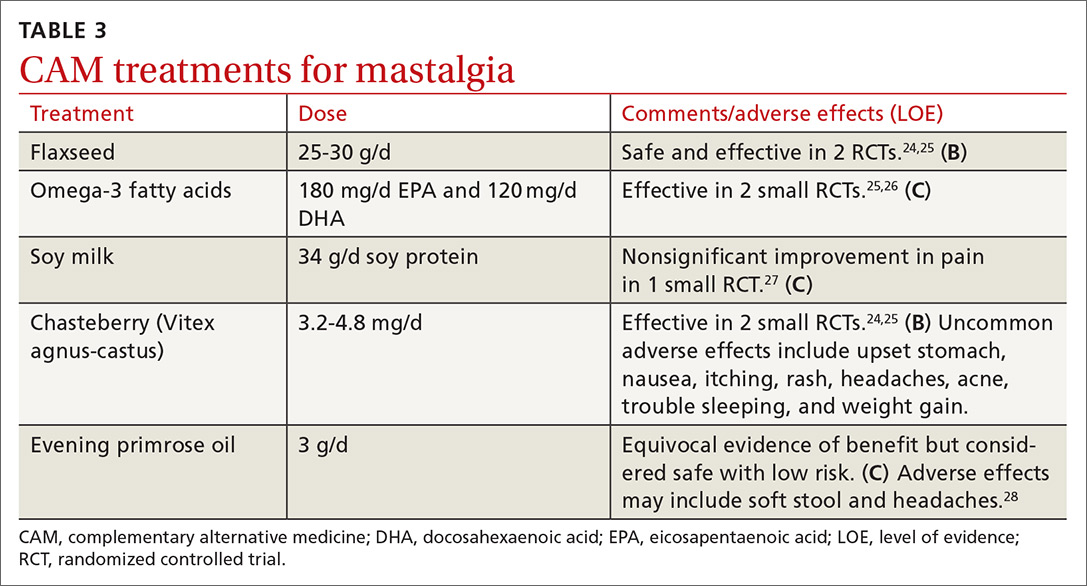

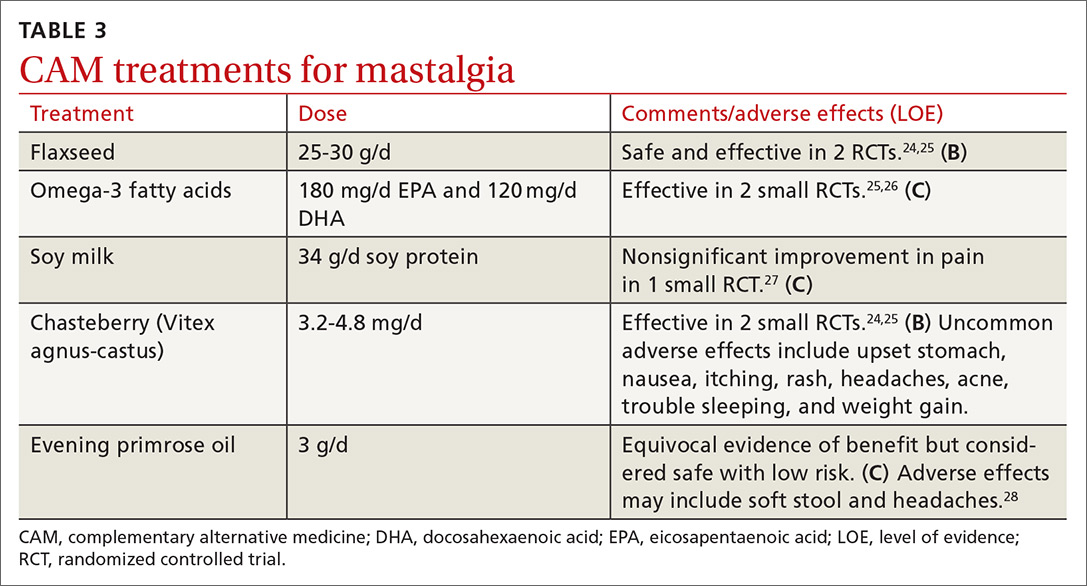

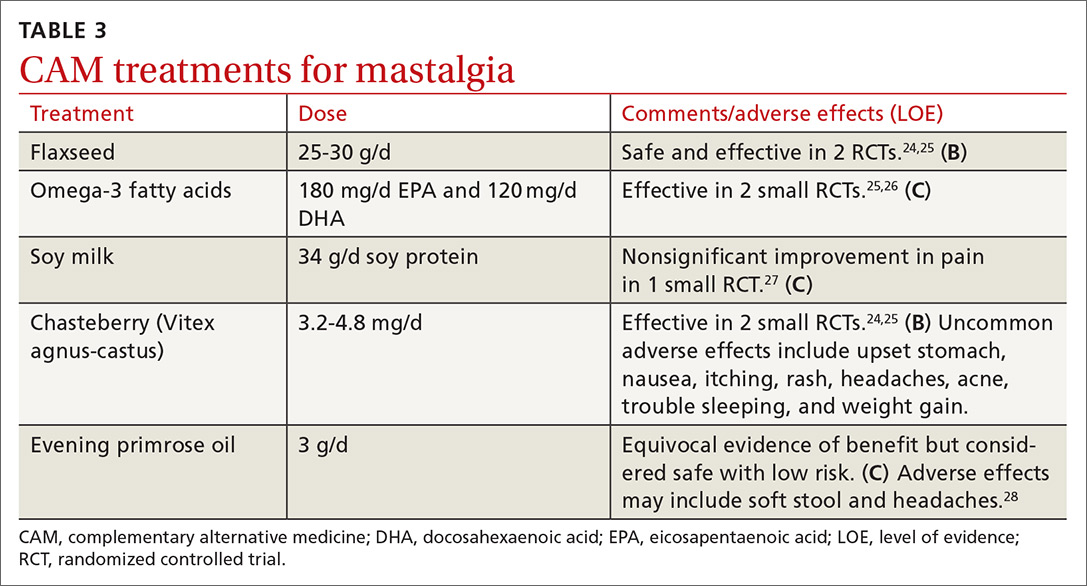

A number of complementary and alternative medicine treatments have demonstrated benefit in treating mastalgia and are often tried before pharmacologic agents (TABLE 324-28). Keep in mind, though, that these therapies are not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). So it’s wise to review particular products with your patient before she buys them (or ask her to bring in any bottles of product for you to review).

Flaxseed, omega-3 fatty acids, and soy milk. Flaxseed, a source of phytoestrogens and omega-3 fatty acids, has been shown to reduce cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.24,25 Breast pain scores were significantly lower for patients ingesting 25 g/d of flaxseed powder compared with placebo.24,25 Omega-3 fatty acids were also more effective than placebo for relief of cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.25,26 Another small RCT demonstrated that women who drank soy milk had a nonsignificant improvement in breast pain compared with those who drank cow’s milk.27

Continue to: Chasteberry

Chasteberry. One RCT demonstrated that Vitex agnus-castus, a chasteberry fruit extract, produced significant and clinically meaningful improvement in visual analogue pain scores for mastalgia, with few adverse effects.29 Another RCT assessing breast fullness as part of the premenstrual syndrome showed significant improvement in breast discomfort for women treated with Vitex agnus-castus.30

Evening primrose oil (EPO). In at least one small study, EPO was effective in controlling breast pain.28 A more recent meta-analysis of all of the EPO trials including gamolenic acid (the active ingredient of EPO) showed no significant difference in mastalgia compared with placebo.31

Pharmacologic Tx options: Start with NSAIDs

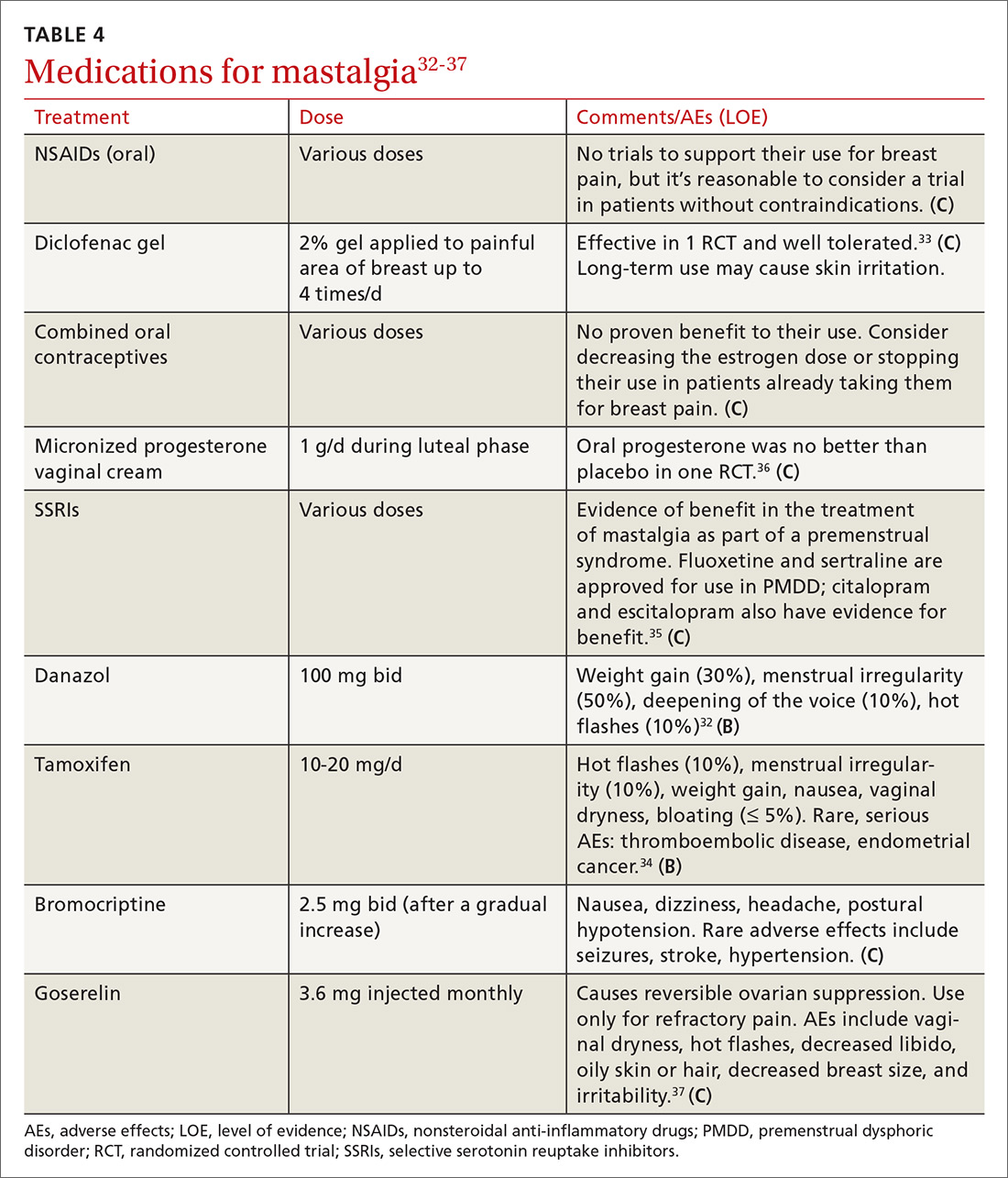

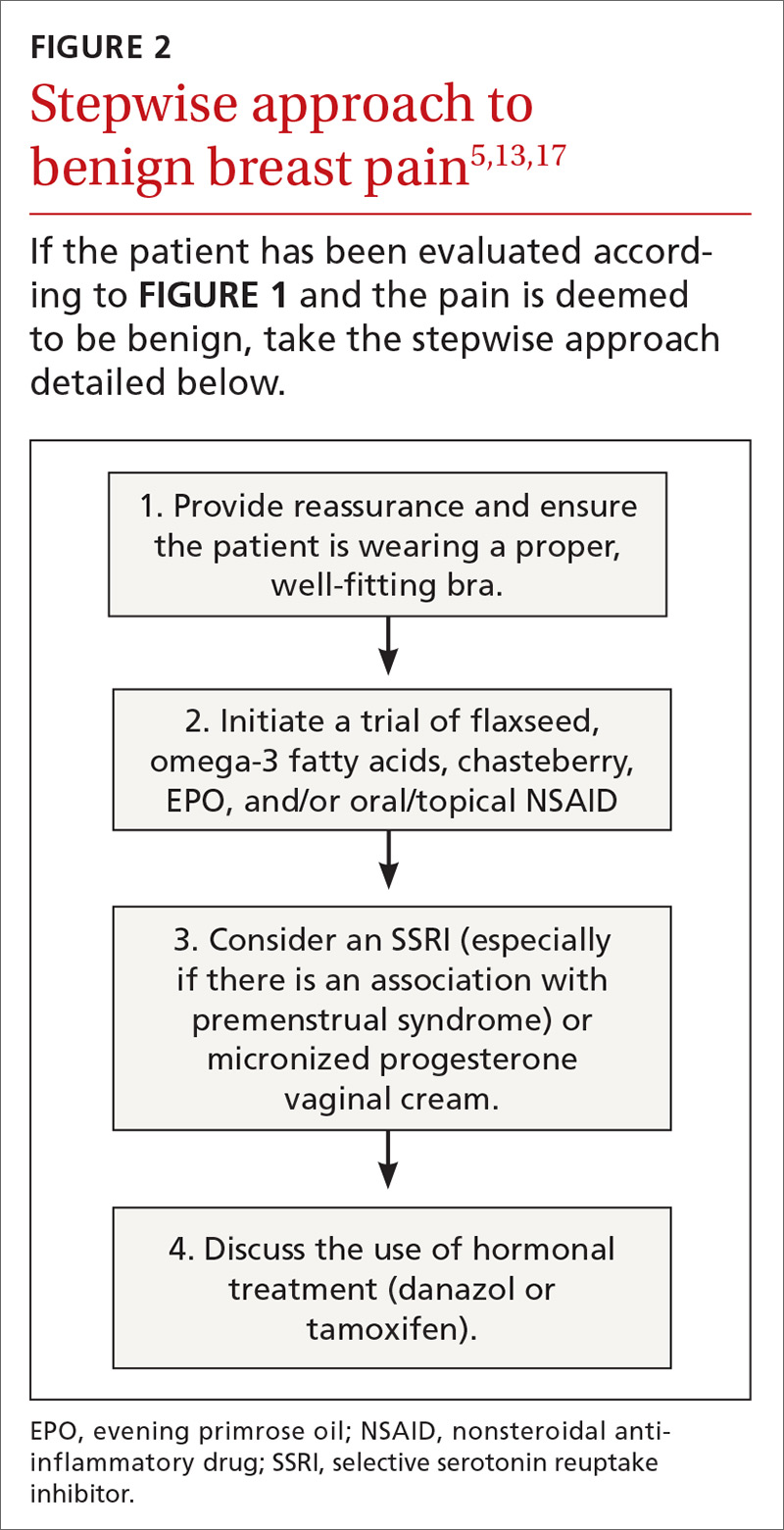

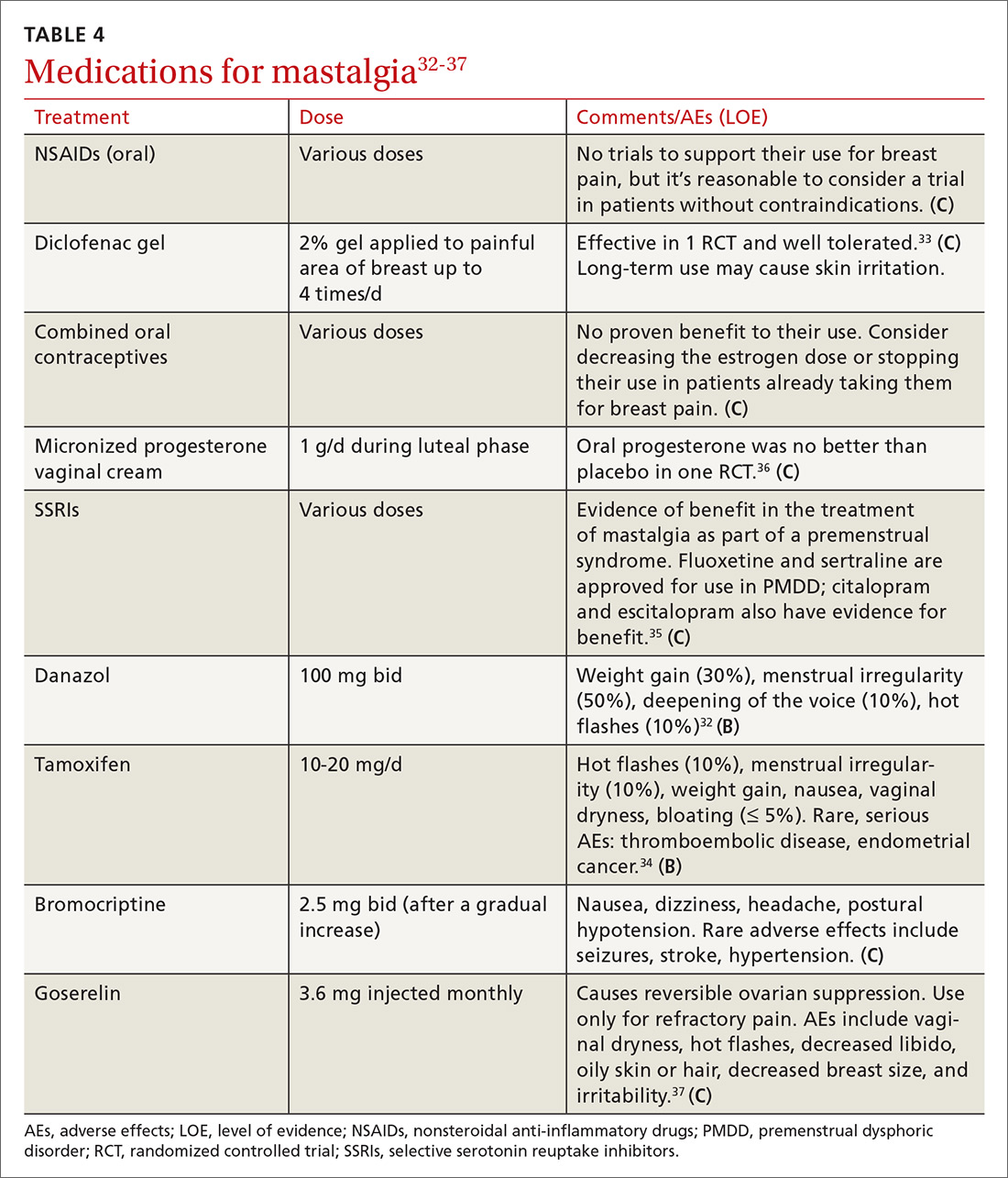

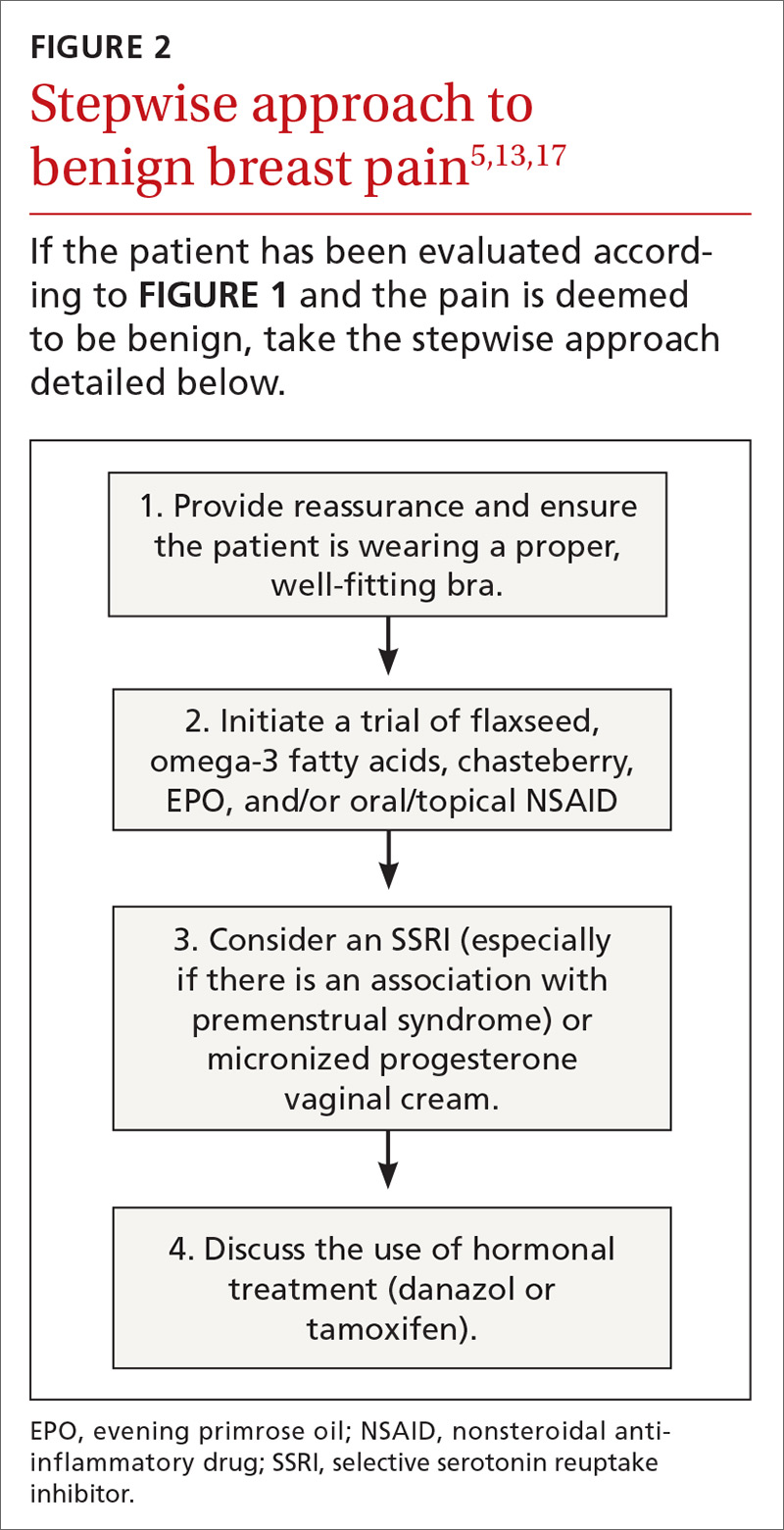

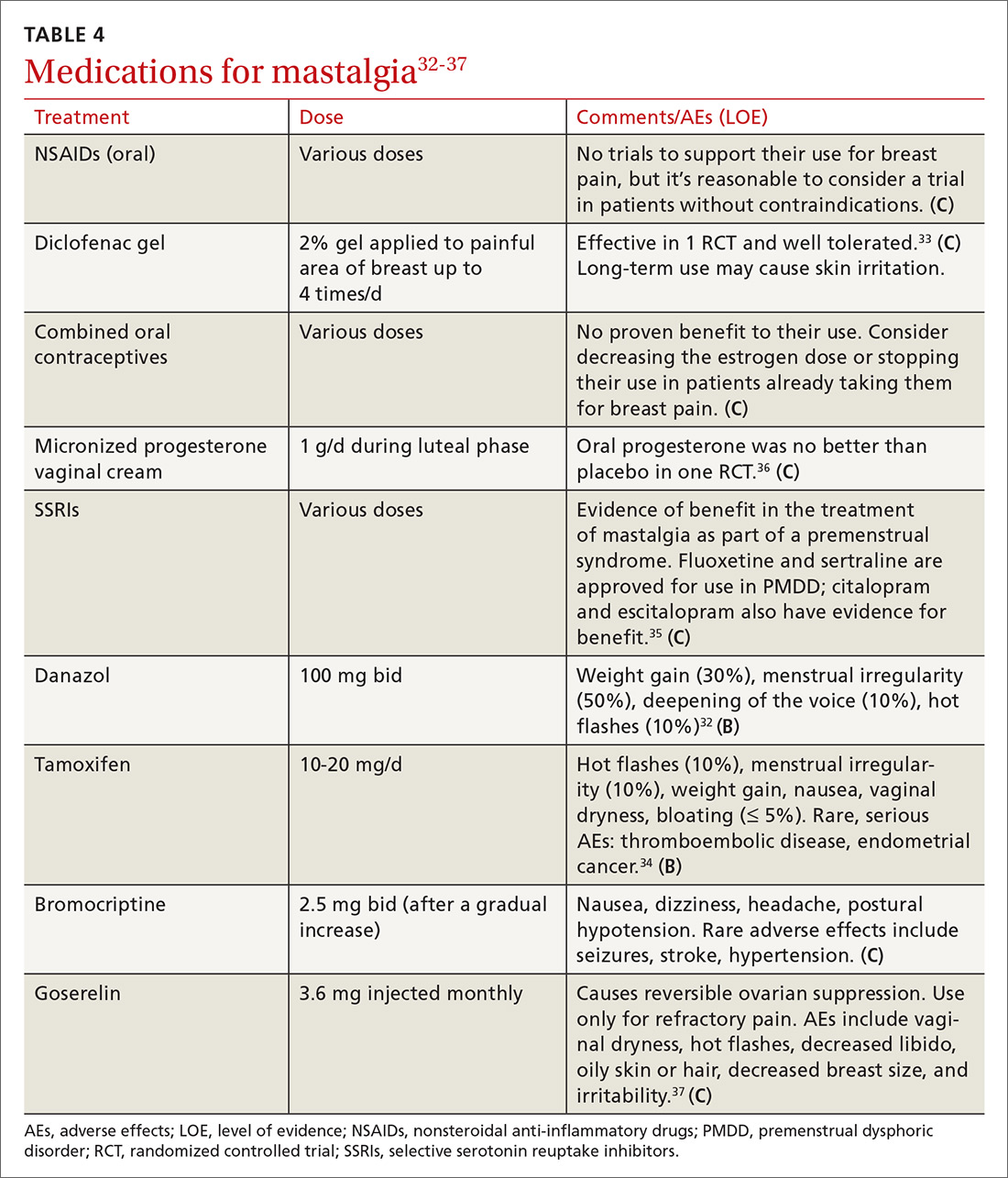

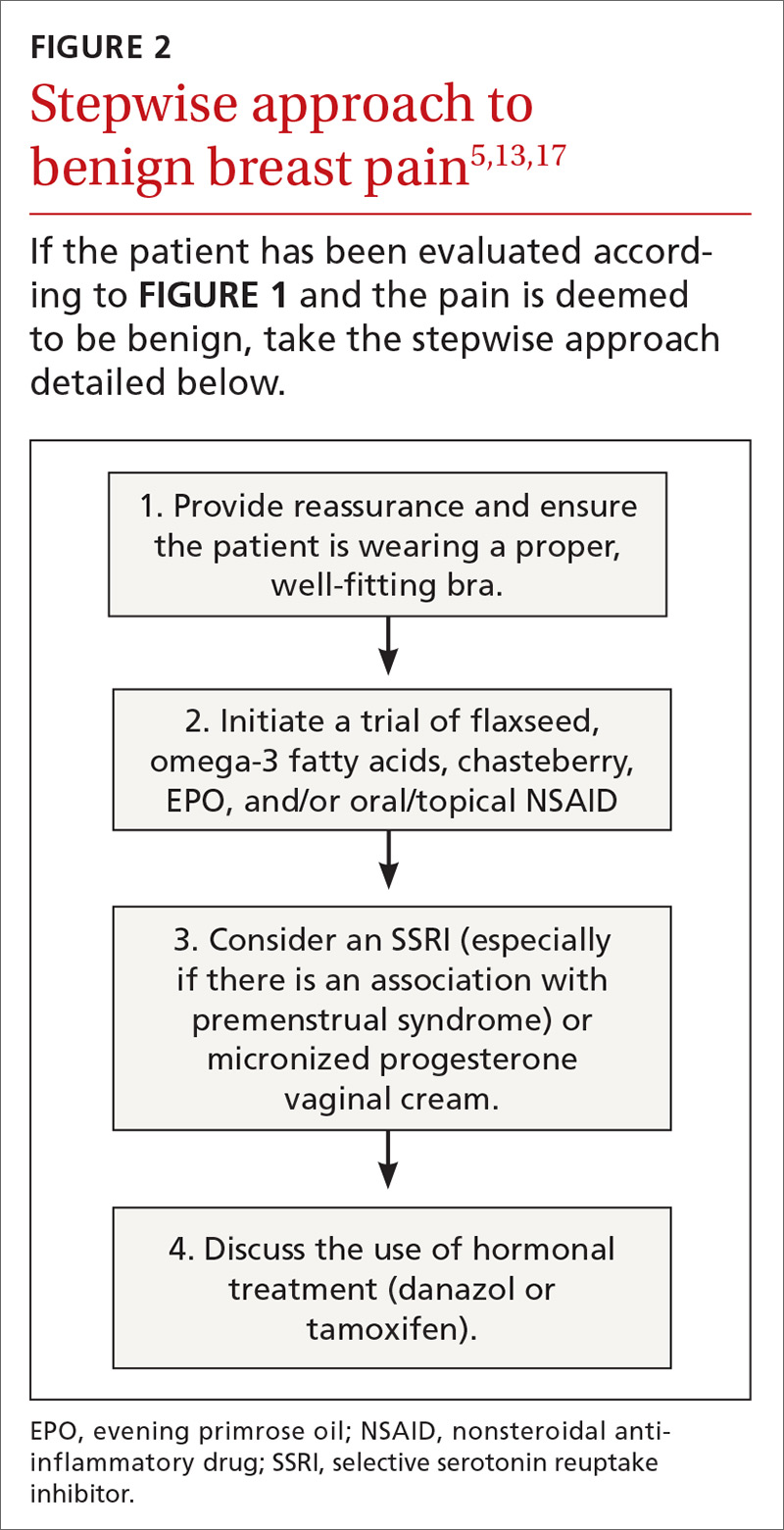

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often recommended as a first-line treatment for mastalgia and are likely effective for some women; however, there is currently insufficient evidence that oral NSAIDs (or acetaminophen) improve pain (TABLE 432-37; FIGURE 25,13,17). Nevertheless, the potential benefits are thought to outweigh the risk of adverse effects in most patients. A small RCT did demonstrate that topical diclofenac was effective in patients with cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia.38

SSRIs. A meta-analysis of 10 double-blind RCTs of SSRIs used in women with premenstrual symptoms, including 4 studies that specifically included physical symptoms such as breast pain, showed SSRIs to be more effective than placebo at relieving breast pain.35

Progesterones. Several studies have found topical, oral, and injected progesterone ineffective at reducing breast pain.8,36,39 However, one RCT did show topical vaginal micronized progesterone used in the luteal phase to be effective in reducing breast pain by at least 50%.36

Continue to: Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives. For women who use oral contraceptive pills and experience cyclic breast pain, continuous dosing (skipping the pill-free week) or using a lower dose of estrogen may improve symptoms. Postmenopausal women with mastalgia that developed with initiation of hormone therapy may benefit from discontinuing hormone therapy or decreasing the estrogen dose; however, there are no RCTs to offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions.10

Danazol. Women with severe mastalgia that does not respond to more benign therapies may require hormone therapy. As with all symptom management, it is imperative to engage the patient in a shared decision-making conversation about the risks and benefits of this treatment strategy. Women must be able to balance the potential adverse effects of agents such as danazol and tamoxifen with the need to alleviate pain and improve quality of life.

Danazol is the only medication FDA-approved for the treatment of mastalgia. Danazol is an androgen that blocks the release of other gonadotropins to limit hormonal stimulation of breast tissue. One RCT demonstrated that danazol (100 mg bid) reduces breast pain in 60% to 90% of women, although adverse effects often limit utility.40 Adverse effects of danazol include weight gain, hot flashes, deepening of the voice, hirsutism, menorrhagia or amenorrhea, muscle cramps, and androgenic effects on a fetus.8,31,40 Danazol may be best used cyclically during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle to limit these adverse effects with reduction of the dose to 100 mg/d after relief of symptoms.31,40

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, has been shown to reduce breast pain in 80% to 90% of women, although it is not indicated for mastalgia.40 Tamoxifen may cause endometrial thickening, hot flashes, menstrual irregularity, venous thromboembolism, and teratogenicity. The 10 mg/d dose appears to be as effective at improving symptoms as the 20 mg/d dose with fewer adverse effects.8,31,40

In a head-to-head randomized trial, tamoxifen was superior to danazol for relief of breast pain with fewer adverse effects.34 Experts recommend limiting use of tamoxifen and danazol to 3 to 6 months. Neither of these drugs is considered safe in pregnancy.

Continue to: Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine, a prolactin inhibitor, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain, although nausea and dizziness contribute to high discontinuation rates. Bromocriptine is less effective than danazol.40

Goserelin, which is not available in the United States, is a gonadorelin analog (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analog) that produces reversible ovarian suppression. One RCT showed that goserelin injection may be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain.37 Adverse effects include vaginal dryness, hot flashes, decreased libido, oily skin or hair, decreased breast size, and irritability. It is recommended as treatment only for severe refractory mastalgia and that it be used no longer than 6 months.31,37

CASE 1

You reassure Ms. S that her history and physical exam are consistent with cyclic breast pain and not malignancy. You review the current US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for breast cancer screening in women ages 40 to 49 years (Grade C; women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose screening).41 Based on shared decision-making,you offer her a screening mammogram, which returns normal. After confirming that she is using an appropriately-sized supportive bra, you recommend adding 25 g/d of ground flaxseed to her diet.

After 2 months she reports a 30% improvement in her pain. You then recommend chasteberry extract 4.2 mg/d, which provides additional relief to the point where she can now sleep better and walk for exercise.

CASE 2

You order a diagnostic mammogram of the left breast, which is normal, and an ultrasound that demonstrates a 6-cm deep mass. A biopsy determines that Ms. R has invasive lobular breast cancer—an extremely unlikely outcome of breast pain. She elects to have a double mastectomy and reconstruction and is doing well 4 years later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1100 Delaplaine Ct., Madison, WI, 53715; [email protected].

1. Salzman B, Fleegle S, Tully AS. Common breast problems. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:343-349.

2. Chetlen AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

3. Expert Panel on Breast Imaging: Jokich PM, Bailey L, D’Orsi C, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Breast Pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S25-S33.

4. Arslan M, Küçükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

5. Smith RL, Pruthi S, Fitzpatrick LA. Evaluation and management of breast pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:353-372.

6. Mansel RE. ABC of breast diseases. Breast pain. BMJ. 1994;309:866-868.

7. Ader DN, South-Paul J, Adera T, et al. Cyclical mastalgia: prevalence and associated health and behavioral factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22:71-76.

8. Iddon J, Dixon JM. Mastalgia. BMJ. 2013;347:f3288.

9. Eren T, Aslan A, Ozemir IA, et al. Factors effecting mastalgia. Breast Care (Basel). 2016;11:188-193.

10. Pearlman MD, Griffin JL. Benign breast disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:747-758.

11. Gateley CA, Mansel RE. The Cardiff Breast Score. Br J Hosp Med. 1991;45:16.

12. Michigan Medicine. University of Michigan. Common breast problems: guidelines for clinical care. https://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/breast/breast.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed September 3, 2019.

13. Millet AV, Dirbas FM. Clinical management of breast pain: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:451-461.

14. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Breast Pain. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3091546/Narrative/. Revised 2018. Accessed July 2, 2019.

15. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Palpable Breast Masses. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69495/Narrative/. Revised 2016. Accessed September 3, 2019.

16. Loving VA, DeMartini WB, Eby PR, et al. Targeted ultrasound in women younger than 30 years with focal breast signs or symptoms: outcomes analyses and management implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1472-1477.

17. Molckovsky A, Fitzgerald B, Freedman O, et al. Approach to inflammatory breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:25-31.

18. Ammari FF, Yaghan RJ, Omari AK. Periductal mastitis: clinical characteristics and outcome. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:819-822.

19. Lannin DR. Twenty-two year experience with recurring subareolar abscess and lactiferous duct fistula treated by a single breast surgeon. Am J Surg. 2004;188:407-410.

20. Wilson JP, Massoll N, Marshall J, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: in search of a therapeutic paradigm. Am Surg. 2007;73:798-802.

21. Bouton ME, Jayaram L, O’Neill PJ, et al. Management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis with observation. Am J Surg. 2015;210:258-262.

22. Olawaiye A, Withiam-Leitch M, Danakas G, et al. Mastalgia: a review of management. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:933-939.

23. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 164: Diagnosis and management of benign breast disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e141-e156.

24. Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Ahmadpour P, et al. Effects of Vitex agnus and flaxseed on cyclic mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:90-95.

25. Vaziri F, Zamani Lari M, Sansami Dehaghani A, et al. Comparing the effects of dietary flaxseed and omega-3 fatty acids supplement on cyclical mastalgia in Iranian women: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Fam Med. 2014;2014:174532.

26. Sohrabi N, Kashanian M, Ghafoori SS, et al. Evaluation of the effect of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: “a pilot trial”. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:141-146.

27. McFayden IJ, Chetty U, Setchell KD, et al. A randomized double blind-cross over trial of soya protein for the treatment of cyclical breast pain. Breast. 2000;9:271-276.

28. Pruthi S, Wahner-Roedler DL, Torkelson CJ, et al. Vitamin E and evening primrose oil for management of cyclical mastalgia: a randomized pilot study. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15:59-67.

29. Halaska M, Raus K, Beles P, et al. Treatment of cyclical mastodynia using an extract of Vitex agnus castus: results of a double-blind comparison with a placebo. Ceska Gynekol. 1998;63:388-392.

30. Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective randomised placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322:134-137.

31. Goyal A. Breast pain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:0812.

32. Maddox PR, Harrison BJ, Mansel RE. Low-dose danazol for mastalgia. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1989;68:43-47.

33. Ahmadinejad M, Delfan B, Haghdani S, et al. Comparing the effect of diclofenac gel and piroxicam gel on mastalgia. Breast J. 2010;16:213-214.

34. Kontostolis E, Stefanidis K, Navrozoglou I, et al. Comparison of tamoxifen with danazol for treatment of cyclical mastalgia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:393-397.

35. Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3.

36. Nappi C, Affinito P, Di Carlo C, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of progesterone vaginal cream treatment for cyclical mastodynia in women with benign breast disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:801-806.

37. Mansel RE, Goyal A, Preece P, et al. European randomized, multicenter study of goserelin (Zoladex) in the management of mastalgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1942-1949.

38. Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficacy of topical nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:525-530.

39. Goyal A. Breast pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:872-873.

40. Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

41. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Screening. Release date: January 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Accessed August 13, 2019.

CASE 1

Robin S is a 40-year-old woman who has never had children or been pregnant. She is in a relationship with a woman so does not use contraception. She has no family history of cancer. She presents with worsening bilateral breast pain that starts 10 days before the onset of her period. The pain has been present for about 4 years, but it has worsened over the last 6 months such that she is unable to wear a bra during these 10 days, finds lying in bed on her side too painful for sleep, and is unable to exercise. She has tried to eliminate caffeine from her diet and takes ibuprofen, but neither of these interventions has controlled her pain. Her breast exam is normal except for diffuse tenderness over both breasts.

CASE 2

Meg R is a 50-year-old healthy woman. She is a G2P2 who breastfed each of her children for 1 year. She does not smoke. She has no family history of breast cancer or other malignancies. She presents with 2 months of deep, left-sided breast pain. She describes the pain as constant, progressive, dull, and achy. She points to a spot in the upper outer quadrant of her left breast and describes the pain as being close to her ribs. She had a screening mammogram 3 weeks earlier that was normal, with findings of dense breasts. She did not tell the technician that she was having pain. Clinical breast examination of both breasts reveals tenderness to deep palpation of the left breast. She has dense breasts but a focal mass is not palpated.

Mastalgia, or breast pain, is one of the most common breast symptoms seen in primary care and a common reason for referrals to breast surgeons. Up to 70% of women will experience breast pain during their lifetime—most in their premenopausal years.1,2

The most common type of breast pain is cyclic (ie, relating to the menstrual cycle); it accounts for up to 70% of all cases of breast pain in women.1,3 The other 2 types of breast pain are noncyclic and extramammary. The cause of cyclic breast pain is unclear, but it is likely hormonally mediated and multifactorial. In the vast majority of women with breast pain, no distinct etiology is found, and there is a very low incidence of breast cancer.2,4

In this review, we describe how to proceed when a woman who is not breastfeeding presents with cyclic or noncyclic breast pain.

Evaluation: Focus on the pain, medications, and history

Evaluation of breast pain should begin with the patient describing the pain, including its quality, location, radiation, and relationship to the menstrual cycle. It’s important to inquire about recent trauma or aggravating activities and to order a pregnancy test for women of childbearing age.1

Cyclic mastalgia is typically described as diffuse, either unilateral or bilateral, with an aching or heavy quality. The pain is often felt in the upper outer quadrant of the breast with radiation to the axilla. It most commonly occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, improves with the onset of menses, and is thought to be related to the increased water content in breast stroma caused by increasing hormone levels during the luteal phase.5-7

Continue to: Noncyclic mastalgia

Noncyclic mastalgia is typically unilateral and localized within 1 quadrant of the breast; however, women may report diffuse pain with radiation to the axilla. The pain is often described as burning, achy, or as soreness.5,6 There can be considerable overlap in the presentations of cyclic and noncyclic pain and differentiating between the 2 is often not necessary as management is similar.8

A thorough review of medications is important as several drugs have been associated with breast pain. These include oral contraceptives, hormone therapy, antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], venlafaxine, mirtazapine), antipsychotics (haloperidol), and some cardiovascular agents (spironolactone, digoxin).5

Inquiring about stress, caffeine intake, smoking status, and bra usage may also yield useful information. Increased stress and caffeine intake have been associated with mastalgia,7 and women who are heavy smokers are more likely to have noncyclic hypersensitive breast pain.9 In addition, women with large breasts often have noncyclic breast pain, particularly if they don’t wear a sufficiently supportive bra.3

Medical, surgical, family history. Relevant aspects of a woman’s past medical, surgical, and family history include prior breast mass or biopsy, breast surgery, and risk factors associated with breast cancer (menarche age < 12 years, menopause age > 55 years, nulliparity, exposure to ionizing radiation, and family history of breast or ovarian cancer).1 A thorough history should include questions to evaluate for extra-mammary etiologies of breast pain such as those that are musculoskeletal or dermatologic in nature (TABLE 11,5,8,10).

Using an objective measure of pain is not only helpful for evaluating the pain itself, but also for determining the effectiveness of treatment strategies. When using the Cardiff Breast Pain Chart, for example, menstrual cycle and level of pain are recorded on a calendar (see www.breastcancercare.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/breast_pain_chart.pdf).11 If the pain is determined to be cyclic, the concern for malignancy is significantly lower.2

Continue to: Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Women presenting with breast pain should undergo a clinical breast exam in both the upright and supine positions. Inspect for asymmetry, erythema, rashes, skin dimpling, nipple discharge, and retraction/inversion. Palpate the breasts for any suspicious masses, asymmetry, or tenderness, as well as for axillary and/or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and chest wall tenderness. This is facilitated by having the patient lie in the lateral decubitus position, allowing the breast to fall away from the chest wall.5,12,13

Imaging: Preferred method depends on the age of the patient

Women with a palpable mass should be referred for diagnostic imaging (FIGURE 11,14). Ultrasonography is the recommended modality for women < 30 years of age (TABLE 215). For women between the ages of 30 and 39 years, appropriate initial imaging includes ultrasound, diagnostic mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). For women ≥ 40 years of age, diagnostic mammography or DBT is recommended.15

Cyclic breast pain. Women with cyclic breast pain do not require further evaluation with imaging. Reassurance and symptomatic treatment is appropriate in most cases, as the risk of malignancy is very low in the absence of other concerning signs or symptoms. A screening mammogram may be appropriate for women > 40 years of age who have not had one in the preceding 12 months.1-3,10,12,15

Noncyclic breast pain. In contrast, imaging may be appropriate in women who present with noncyclic breast pain depending on the woman’s age and whether the pain is focal (≤ 25% of the breast and axillary tissue) or diffuse (> 25% of the breast and axillary tissue). Although evidence suggests that the risk of malignancy in women with noncyclic breast pain is low, the American College of Radiology advises that imaging may be useful in some patients to provide reassurance and to exclude a treatable cause of breast pain.3,14 In women with focal pain, ultrasound alone is the preferred modality for women < 30 years of age and ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography is recommended for women ≥ 30 years of age.3,14

In one small study, the use of ultrasonography in women ages < 30 years with focal breast pain had a sensitivity of 100% and a negative predictive value of 100%.16 Similarly, another small retrospective study in older women (average age 56 years) with focal breast pain and no palpable mass showed that ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography had a negative predictive value of 100%.4 DBT may be used in place of mammography to rule out malignancy in this setting.

Continue to: In general...

In general, routine imaging is not indicated for women with noncyclic diffuse breast pain, although diagnostic mammography or DBT may be considered in women ≥ 40 years of age 14 (see “Less common diagnoses with breast pain”4,5,17-21).

SIDEBAR

Less common diagnoses with breast pain

Many women presenting with breast pain are concerned about malignancy. Breast cancer is an uncommon cause of breast pain; only 0.5% of patients presenting with mastalgia without other clinical findings have a malignancy.4 Mastalgia is not a risk factor for breast cancer.

When mastalgia is associated with breast cancer, it is more likely to be unilateral, intense, noncyclic, and progressive.5 Concerning features that warrant further evaluation include new onset focal pain with or without an abnormal exam. If symptoms cannot be explained by an obvious cause (such as trauma, costochondritis, radicular back or intercostal pain, herpes zoster, or superficial thrombophlebitis that does not resolve), diagnostic breast imaging is indicated.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is an aggressive form of breast cancer that initially presents with breast pain and rapidly enlarging diffuse erythema of the breast in the absence of a discrete breast lump. The initial presentation is similar to that seen with benign inflammatory etiologies of the breast tissue like cellulitis or abscess, duct ectasia, mastitis, phlebitis of the thoracoepigastric vein (Mondor’s disease), or fat necrosis.17 Benign breast conditions due to these causes will generally resolve with appropriate treatment for those conditions within 7 days and will generally not present with the warning signs of IBC, which include a personal history of breast cancer, nonlactational status, and palpable axillary adenopathy. Although uncommon (accounting for 1%-6% of all breast cancer diagnoses), IBC spreads rapidly over a few weeks; thus, urgent imaging is warranted.17

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissue that may or may not be associated with a bacterial infection and uncommonly occurs in nonbreastfeeding women. Periductal mastitis is characterized by inflammation of the subareolar ducts and can present with pain, periareolar inflammation, and purulent nipple discharge.18 The condition is typically chronic, and the inflamed ducts may become secondarily infected leading to duct damage and abscess formation. Treatment generally includes antibiotics along with incision and drainage of any associated abscesses or duct excision.18,19

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a rare inflammatory breast disease that typically affects young parous women. The presentation can vary from a single peripheral breast mass to multiple areas of infection with abscesses and skin ulceration. The etiology is unknown. Diagnosis requires a core needle biopsy to rule out malignancy or other causes of granulomatous disease. IGM is a benign condition and typically resolves without treatment over the course of several months, although antibiotics and/or drainage may be required for secondary infections.20,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment: When reassurance isn’t enough

Nonrandomized studies suggest that reassurance that mastalgia is benign is enough to treat up to 70% of women.8,22,23 Cyclic breast pain is usually treated symptomatically since the likelihood of breast cancer is extremely low in absence of clinical breast examination abnormalities.2 Because treatment for cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia overlaps, available treatments are discussed together on the following pages.

Lifestyle factors associated with breast pain include stress, caffeine consumption, smoking, and having breastfed 3 or more children (P < .05).9 Although restriction of caffeine, fat, and salt intake may be attempted to address breast pain, no randomized control trials (RCTs) of these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing mastalgia.8,10

Although not supported by RCTs, first-line treatment of mastalgia includes a recommendation that women, particularly those with large, heavy breasts, wear a well-fitted and supportive bra.8,10

Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for mastalgia

A number of complementary and alternative medicine treatments have demonstrated benefit in treating mastalgia and are often tried before pharmacologic agents (TABLE 324-28). Keep in mind, though, that these therapies are not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). So it’s wise to review particular products with your patient before she buys them (or ask her to bring in any bottles of product for you to review).

Flaxseed, omega-3 fatty acids, and soy milk. Flaxseed, a source of phytoestrogens and omega-3 fatty acids, has been shown to reduce cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.24,25 Breast pain scores were significantly lower for patients ingesting 25 g/d of flaxseed powder compared with placebo.24,25 Omega-3 fatty acids were also more effective than placebo for relief of cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.25,26 Another small RCT demonstrated that women who drank soy milk had a nonsignificant improvement in breast pain compared with those who drank cow’s milk.27

Continue to: Chasteberry

Chasteberry. One RCT demonstrated that Vitex agnus-castus, a chasteberry fruit extract, produced significant and clinically meaningful improvement in visual analogue pain scores for mastalgia, with few adverse effects.29 Another RCT assessing breast fullness as part of the premenstrual syndrome showed significant improvement in breast discomfort for women treated with Vitex agnus-castus.30

Evening primrose oil (EPO). In at least one small study, EPO was effective in controlling breast pain.28 A more recent meta-analysis of all of the EPO trials including gamolenic acid (the active ingredient of EPO) showed no significant difference in mastalgia compared with placebo.31

Pharmacologic Tx options: Start with NSAIDs

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often recommended as a first-line treatment for mastalgia and are likely effective for some women; however, there is currently insufficient evidence that oral NSAIDs (or acetaminophen) improve pain (TABLE 432-37; FIGURE 25,13,17). Nevertheless, the potential benefits are thought to outweigh the risk of adverse effects in most patients. A small RCT did demonstrate that topical diclofenac was effective in patients with cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia.38

SSRIs. A meta-analysis of 10 double-blind RCTs of SSRIs used in women with premenstrual symptoms, including 4 studies that specifically included physical symptoms such as breast pain, showed SSRIs to be more effective than placebo at relieving breast pain.35

Progesterones. Several studies have found topical, oral, and injected progesterone ineffective at reducing breast pain.8,36,39 However, one RCT did show topical vaginal micronized progesterone used in the luteal phase to be effective in reducing breast pain by at least 50%.36

Continue to: Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives. For women who use oral contraceptive pills and experience cyclic breast pain, continuous dosing (skipping the pill-free week) or using a lower dose of estrogen may improve symptoms. Postmenopausal women with mastalgia that developed with initiation of hormone therapy may benefit from discontinuing hormone therapy or decreasing the estrogen dose; however, there are no RCTs to offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions.10

Danazol. Women with severe mastalgia that does not respond to more benign therapies may require hormone therapy. As with all symptom management, it is imperative to engage the patient in a shared decision-making conversation about the risks and benefits of this treatment strategy. Women must be able to balance the potential adverse effects of agents such as danazol and tamoxifen with the need to alleviate pain and improve quality of life.

Danazol is the only medication FDA-approved for the treatment of mastalgia. Danazol is an androgen that blocks the release of other gonadotropins to limit hormonal stimulation of breast tissue. One RCT demonstrated that danazol (100 mg bid) reduces breast pain in 60% to 90% of women, although adverse effects often limit utility.40 Adverse effects of danazol include weight gain, hot flashes, deepening of the voice, hirsutism, menorrhagia or amenorrhea, muscle cramps, and androgenic effects on a fetus.8,31,40 Danazol may be best used cyclically during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle to limit these adverse effects with reduction of the dose to 100 mg/d after relief of symptoms.31,40

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, has been shown to reduce breast pain in 80% to 90% of women, although it is not indicated for mastalgia.40 Tamoxifen may cause endometrial thickening, hot flashes, menstrual irregularity, venous thromboembolism, and teratogenicity. The 10 mg/d dose appears to be as effective at improving symptoms as the 20 mg/d dose with fewer adverse effects.8,31,40

In a head-to-head randomized trial, tamoxifen was superior to danazol for relief of breast pain with fewer adverse effects.34 Experts recommend limiting use of tamoxifen and danazol to 3 to 6 months. Neither of these drugs is considered safe in pregnancy.

Continue to: Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine, a prolactin inhibitor, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain, although nausea and dizziness contribute to high discontinuation rates. Bromocriptine is less effective than danazol.40

Goserelin, which is not available in the United States, is a gonadorelin analog (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analog) that produces reversible ovarian suppression. One RCT showed that goserelin injection may be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain.37 Adverse effects include vaginal dryness, hot flashes, decreased libido, oily skin or hair, decreased breast size, and irritability. It is recommended as treatment only for severe refractory mastalgia and that it be used no longer than 6 months.31,37

CASE 1

You reassure Ms. S that her history and physical exam are consistent with cyclic breast pain and not malignancy. You review the current US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for breast cancer screening in women ages 40 to 49 years (Grade C; women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose screening).41 Based on shared decision-making,you offer her a screening mammogram, which returns normal. After confirming that she is using an appropriately-sized supportive bra, you recommend adding 25 g/d of ground flaxseed to her diet.

After 2 months she reports a 30% improvement in her pain. You then recommend chasteberry extract 4.2 mg/d, which provides additional relief to the point where she can now sleep better and walk for exercise.

CASE 2

You order a diagnostic mammogram of the left breast, which is normal, and an ultrasound that demonstrates a 6-cm deep mass. A biopsy determines that Ms. R has invasive lobular breast cancer—an extremely unlikely outcome of breast pain. She elects to have a double mastectomy and reconstruction and is doing well 4 years later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1100 Delaplaine Ct., Madison, WI, 53715; [email protected].

CASE 1

Robin S is a 40-year-old woman who has never had children or been pregnant. She is in a relationship with a woman so does not use contraception. She has no family history of cancer. She presents with worsening bilateral breast pain that starts 10 days before the onset of her period. The pain has been present for about 4 years, but it has worsened over the last 6 months such that she is unable to wear a bra during these 10 days, finds lying in bed on her side too painful for sleep, and is unable to exercise. She has tried to eliminate caffeine from her diet and takes ibuprofen, but neither of these interventions has controlled her pain. Her breast exam is normal except for diffuse tenderness over both breasts.

CASE 2

Meg R is a 50-year-old healthy woman. She is a G2P2 who breastfed each of her children for 1 year. She does not smoke. She has no family history of breast cancer or other malignancies. She presents with 2 months of deep, left-sided breast pain. She describes the pain as constant, progressive, dull, and achy. She points to a spot in the upper outer quadrant of her left breast and describes the pain as being close to her ribs. She had a screening mammogram 3 weeks earlier that was normal, with findings of dense breasts. She did not tell the technician that she was having pain. Clinical breast examination of both breasts reveals tenderness to deep palpation of the left breast. She has dense breasts but a focal mass is not palpated.

Mastalgia, or breast pain, is one of the most common breast symptoms seen in primary care and a common reason for referrals to breast surgeons. Up to 70% of women will experience breast pain during their lifetime—most in their premenopausal years.1,2

The most common type of breast pain is cyclic (ie, relating to the menstrual cycle); it accounts for up to 70% of all cases of breast pain in women.1,3 The other 2 types of breast pain are noncyclic and extramammary. The cause of cyclic breast pain is unclear, but it is likely hormonally mediated and multifactorial. In the vast majority of women with breast pain, no distinct etiology is found, and there is a very low incidence of breast cancer.2,4

In this review, we describe how to proceed when a woman who is not breastfeeding presents with cyclic or noncyclic breast pain.

Evaluation: Focus on the pain, medications, and history

Evaluation of breast pain should begin with the patient describing the pain, including its quality, location, radiation, and relationship to the menstrual cycle. It’s important to inquire about recent trauma or aggravating activities and to order a pregnancy test for women of childbearing age.1

Cyclic mastalgia is typically described as diffuse, either unilateral or bilateral, with an aching or heavy quality. The pain is often felt in the upper outer quadrant of the breast with radiation to the axilla. It most commonly occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, improves with the onset of menses, and is thought to be related to the increased water content in breast stroma caused by increasing hormone levels during the luteal phase.5-7

Continue to: Noncyclic mastalgia

Noncyclic mastalgia is typically unilateral and localized within 1 quadrant of the breast; however, women may report diffuse pain with radiation to the axilla. The pain is often described as burning, achy, or as soreness.5,6 There can be considerable overlap in the presentations of cyclic and noncyclic pain and differentiating between the 2 is often not necessary as management is similar.8

A thorough review of medications is important as several drugs have been associated with breast pain. These include oral contraceptives, hormone therapy, antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], venlafaxine, mirtazapine), antipsychotics (haloperidol), and some cardiovascular agents (spironolactone, digoxin).5

Inquiring about stress, caffeine intake, smoking status, and bra usage may also yield useful information. Increased stress and caffeine intake have been associated with mastalgia,7 and women who are heavy smokers are more likely to have noncyclic hypersensitive breast pain.9 In addition, women with large breasts often have noncyclic breast pain, particularly if they don’t wear a sufficiently supportive bra.3

Medical, surgical, family history. Relevant aspects of a woman’s past medical, surgical, and family history include prior breast mass or biopsy, breast surgery, and risk factors associated with breast cancer (menarche age < 12 years, menopause age > 55 years, nulliparity, exposure to ionizing radiation, and family history of breast or ovarian cancer).1 A thorough history should include questions to evaluate for extra-mammary etiologies of breast pain such as those that are musculoskeletal or dermatologic in nature (TABLE 11,5,8,10).

Using an objective measure of pain is not only helpful for evaluating the pain itself, but also for determining the effectiveness of treatment strategies. When using the Cardiff Breast Pain Chart, for example, menstrual cycle and level of pain are recorded on a calendar (see www.breastcancercare.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/breast_pain_chart.pdf).11 If the pain is determined to be cyclic, the concern for malignancy is significantly lower.2

Continue to: Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Ensure that the physical exam is thorough

Women presenting with breast pain should undergo a clinical breast exam in both the upright and supine positions. Inspect for asymmetry, erythema, rashes, skin dimpling, nipple discharge, and retraction/inversion. Palpate the breasts for any suspicious masses, asymmetry, or tenderness, as well as for axillary and/or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and chest wall tenderness. This is facilitated by having the patient lie in the lateral decubitus position, allowing the breast to fall away from the chest wall.5,12,13

Imaging: Preferred method depends on the age of the patient

Women with a palpable mass should be referred for diagnostic imaging (FIGURE 11,14). Ultrasonography is the recommended modality for women < 30 years of age (TABLE 215). For women between the ages of 30 and 39 years, appropriate initial imaging includes ultrasound, diagnostic mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). For women ≥ 40 years of age, diagnostic mammography or DBT is recommended.15

Cyclic breast pain. Women with cyclic breast pain do not require further evaluation with imaging. Reassurance and symptomatic treatment is appropriate in most cases, as the risk of malignancy is very low in the absence of other concerning signs or symptoms. A screening mammogram may be appropriate for women > 40 years of age who have not had one in the preceding 12 months.1-3,10,12,15

Noncyclic breast pain. In contrast, imaging may be appropriate in women who present with noncyclic breast pain depending on the woman’s age and whether the pain is focal (≤ 25% of the breast and axillary tissue) or diffuse (> 25% of the breast and axillary tissue). Although evidence suggests that the risk of malignancy in women with noncyclic breast pain is low, the American College of Radiology advises that imaging may be useful in some patients to provide reassurance and to exclude a treatable cause of breast pain.3,14 In women with focal pain, ultrasound alone is the preferred modality for women < 30 years of age and ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography is recommended for women ≥ 30 years of age.3,14

In one small study, the use of ultrasonography in women ages < 30 years with focal breast pain had a sensitivity of 100% and a negative predictive value of 100%.16 Similarly, another small retrospective study in older women (average age 56 years) with focal breast pain and no palpable mass showed that ultrasound plus diagnostic mammography had a negative predictive value of 100%.4 DBT may be used in place of mammography to rule out malignancy in this setting.

Continue to: In general...

In general, routine imaging is not indicated for women with noncyclic diffuse breast pain, although diagnostic mammography or DBT may be considered in women ≥ 40 years of age 14 (see “Less common diagnoses with breast pain”4,5,17-21).

SIDEBAR

Less common diagnoses with breast pain

Many women presenting with breast pain are concerned about malignancy. Breast cancer is an uncommon cause of breast pain; only 0.5% of patients presenting with mastalgia without other clinical findings have a malignancy.4 Mastalgia is not a risk factor for breast cancer.

When mastalgia is associated with breast cancer, it is more likely to be unilateral, intense, noncyclic, and progressive.5 Concerning features that warrant further evaluation include new onset focal pain with or without an abnormal exam. If symptoms cannot be explained by an obvious cause (such as trauma, costochondritis, radicular back or intercostal pain, herpes zoster, or superficial thrombophlebitis that does not resolve), diagnostic breast imaging is indicated.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is an aggressive form of breast cancer that initially presents with breast pain and rapidly enlarging diffuse erythema of the breast in the absence of a discrete breast lump. The initial presentation is similar to that seen with benign inflammatory etiologies of the breast tissue like cellulitis or abscess, duct ectasia, mastitis, phlebitis of the thoracoepigastric vein (Mondor’s disease), or fat necrosis.17 Benign breast conditions due to these causes will generally resolve with appropriate treatment for those conditions within 7 days and will generally not present with the warning signs of IBC, which include a personal history of breast cancer, nonlactational status, and palpable axillary adenopathy. Although uncommon (accounting for 1%-6% of all breast cancer diagnoses), IBC spreads rapidly over a few weeks; thus, urgent imaging is warranted.17

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissue that may or may not be associated with a bacterial infection and uncommonly occurs in nonbreastfeeding women. Periductal mastitis is characterized by inflammation of the subareolar ducts and can present with pain, periareolar inflammation, and purulent nipple discharge.18 The condition is typically chronic, and the inflamed ducts may become secondarily infected leading to duct damage and abscess formation. Treatment generally includes antibiotics along with incision and drainage of any associated abscesses or duct excision.18,19

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a rare inflammatory breast disease that typically affects young parous women. The presentation can vary from a single peripheral breast mass to multiple areas of infection with abscesses and skin ulceration. The etiology is unknown. Diagnosis requires a core needle biopsy to rule out malignancy or other causes of granulomatous disease. IGM is a benign condition and typically resolves without treatment over the course of several months, although antibiotics and/or drainage may be required for secondary infections.20,21

Continue to: Treatment...

Treatment: When reassurance isn’t enough

Nonrandomized studies suggest that reassurance that mastalgia is benign is enough to treat up to 70% of women.8,22,23 Cyclic breast pain is usually treated symptomatically since the likelihood of breast cancer is extremely low in absence of clinical breast examination abnormalities.2 Because treatment for cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia overlaps, available treatments are discussed together on the following pages.

Lifestyle factors associated with breast pain include stress, caffeine consumption, smoking, and having breastfed 3 or more children (P < .05).9 Although restriction of caffeine, fat, and salt intake may be attempted to address breast pain, no randomized control trials (RCTs) of these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing mastalgia.8,10

Although not supported by RCTs, first-line treatment of mastalgia includes a recommendation that women, particularly those with large, heavy breasts, wear a well-fitted and supportive bra.8,10

Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for mastalgia

A number of complementary and alternative medicine treatments have demonstrated benefit in treating mastalgia and are often tried before pharmacologic agents (TABLE 324-28). Keep in mind, though, that these therapies are not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). So it’s wise to review particular products with your patient before she buys them (or ask her to bring in any bottles of product for you to review).

Flaxseed, omega-3 fatty acids, and soy milk. Flaxseed, a source of phytoestrogens and omega-3 fatty acids, has been shown to reduce cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.24,25 Breast pain scores were significantly lower for patients ingesting 25 g/d of flaxseed powder compared with placebo.24,25 Omega-3 fatty acids were also more effective than placebo for relief of cyclic breast pain in 2 small RCTs.25,26 Another small RCT demonstrated that women who drank soy milk had a nonsignificant improvement in breast pain compared with those who drank cow’s milk.27

Continue to: Chasteberry

Chasteberry. One RCT demonstrated that Vitex agnus-castus, a chasteberry fruit extract, produced significant and clinically meaningful improvement in visual analogue pain scores for mastalgia, with few adverse effects.29 Another RCT assessing breast fullness as part of the premenstrual syndrome showed significant improvement in breast discomfort for women treated with Vitex agnus-castus.30

Evening primrose oil (EPO). In at least one small study, EPO was effective in controlling breast pain.28 A more recent meta-analysis of all of the EPO trials including gamolenic acid (the active ingredient of EPO) showed no significant difference in mastalgia compared with placebo.31

Pharmacologic Tx options: Start with NSAIDs

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often recommended as a first-line treatment for mastalgia and are likely effective for some women; however, there is currently insufficient evidence that oral NSAIDs (or acetaminophen) improve pain (TABLE 432-37; FIGURE 25,13,17). Nevertheless, the potential benefits are thought to outweigh the risk of adverse effects in most patients. A small RCT did demonstrate that topical diclofenac was effective in patients with cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia.38

SSRIs. A meta-analysis of 10 double-blind RCTs of SSRIs used in women with premenstrual symptoms, including 4 studies that specifically included physical symptoms such as breast pain, showed SSRIs to be more effective than placebo at relieving breast pain.35

Progesterones. Several studies have found topical, oral, and injected progesterone ineffective at reducing breast pain.8,36,39 However, one RCT did show topical vaginal micronized progesterone used in the luteal phase to be effective in reducing breast pain by at least 50%.36

Continue to: Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives. For women who use oral contraceptive pills and experience cyclic breast pain, continuous dosing (skipping the pill-free week) or using a lower dose of estrogen may improve symptoms. Postmenopausal women with mastalgia that developed with initiation of hormone therapy may benefit from discontinuing hormone therapy or decreasing the estrogen dose; however, there are no RCTs to offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions.10

Danazol. Women with severe mastalgia that does not respond to more benign therapies may require hormone therapy. As with all symptom management, it is imperative to engage the patient in a shared decision-making conversation about the risks and benefits of this treatment strategy. Women must be able to balance the potential adverse effects of agents such as danazol and tamoxifen with the need to alleviate pain and improve quality of life.

Danazol is the only medication FDA-approved for the treatment of mastalgia. Danazol is an androgen that blocks the release of other gonadotropins to limit hormonal stimulation of breast tissue. One RCT demonstrated that danazol (100 mg bid) reduces breast pain in 60% to 90% of women, although adverse effects often limit utility.40 Adverse effects of danazol include weight gain, hot flashes, deepening of the voice, hirsutism, menorrhagia or amenorrhea, muscle cramps, and androgenic effects on a fetus.8,31,40 Danazol may be best used cyclically during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle to limit these adverse effects with reduction of the dose to 100 mg/d after relief of symptoms.31,40

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, has been shown to reduce breast pain in 80% to 90% of women, although it is not indicated for mastalgia.40 Tamoxifen may cause endometrial thickening, hot flashes, menstrual irregularity, venous thromboembolism, and teratogenicity. The 10 mg/d dose appears to be as effective at improving symptoms as the 20 mg/d dose with fewer adverse effects.8,31,40

In a head-to-head randomized trial, tamoxifen was superior to danazol for relief of breast pain with fewer adverse effects.34 Experts recommend limiting use of tamoxifen and danazol to 3 to 6 months. Neither of these drugs is considered safe in pregnancy.

Continue to: Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine, a prolactin inhibitor, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain, although nausea and dizziness contribute to high discontinuation rates. Bromocriptine is less effective than danazol.40

Goserelin, which is not available in the United States, is a gonadorelin analog (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analog) that produces reversible ovarian suppression. One RCT showed that goserelin injection may be more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain.37 Adverse effects include vaginal dryness, hot flashes, decreased libido, oily skin or hair, decreased breast size, and irritability. It is recommended as treatment only for severe refractory mastalgia and that it be used no longer than 6 months.31,37

CASE 1

You reassure Ms. S that her history and physical exam are consistent with cyclic breast pain and not malignancy. You review the current US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for breast cancer screening in women ages 40 to 49 years (Grade C; women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose screening).41 Based on shared decision-making,you offer her a screening mammogram, which returns normal. After confirming that she is using an appropriately-sized supportive bra, you recommend adding 25 g/d of ground flaxseed to her diet.

After 2 months she reports a 30% improvement in her pain. You then recommend chasteberry extract 4.2 mg/d, which provides additional relief to the point where she can now sleep better and walk for exercise.

CASE 2

You order a diagnostic mammogram of the left breast, which is normal, and an ultrasound that demonstrates a 6-cm deep mass. A biopsy determines that Ms. R has invasive lobular breast cancer—an extremely unlikely outcome of breast pain. She elects to have a double mastectomy and reconstruction and is doing well 4 years later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1100 Delaplaine Ct., Madison, WI, 53715; [email protected].

1. Salzman B, Fleegle S, Tully AS. Common breast problems. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:343-349.

2. Chetlen AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

3. Expert Panel on Breast Imaging: Jokich PM, Bailey L, D’Orsi C, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Breast Pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S25-S33.

4. Arslan M, Küçükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

5. Smith RL, Pruthi S, Fitzpatrick LA. Evaluation and management of breast pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:353-372.

6. Mansel RE. ABC of breast diseases. Breast pain. BMJ. 1994;309:866-868.

7. Ader DN, South-Paul J, Adera T, et al. Cyclical mastalgia: prevalence and associated health and behavioral factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22:71-76.

8. Iddon J, Dixon JM. Mastalgia. BMJ. 2013;347:f3288.

9. Eren T, Aslan A, Ozemir IA, et al. Factors effecting mastalgia. Breast Care (Basel). 2016;11:188-193.

10. Pearlman MD, Griffin JL. Benign breast disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:747-758.

11. Gateley CA, Mansel RE. The Cardiff Breast Score. Br J Hosp Med. 1991;45:16.

12. Michigan Medicine. University of Michigan. Common breast problems: guidelines for clinical care. https://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/breast/breast.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed September 3, 2019.

13. Millet AV, Dirbas FM. Clinical management of breast pain: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:451-461.

14. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Breast Pain. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3091546/Narrative/. Revised 2018. Accessed July 2, 2019.

15. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Palpable Breast Masses. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69495/Narrative/. Revised 2016. Accessed September 3, 2019.

16. Loving VA, DeMartini WB, Eby PR, et al. Targeted ultrasound in women younger than 30 years with focal breast signs or symptoms: outcomes analyses and management implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1472-1477.

17. Molckovsky A, Fitzgerald B, Freedman O, et al. Approach to inflammatory breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:25-31.

18. Ammari FF, Yaghan RJ, Omari AK. Periductal mastitis: clinical characteristics and outcome. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:819-822.

19. Lannin DR. Twenty-two year experience with recurring subareolar abscess and lactiferous duct fistula treated by a single breast surgeon. Am J Surg. 2004;188:407-410.

20. Wilson JP, Massoll N, Marshall J, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: in search of a therapeutic paradigm. Am Surg. 2007;73:798-802.

21. Bouton ME, Jayaram L, O’Neill PJ, et al. Management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis with observation. Am J Surg. 2015;210:258-262.

22. Olawaiye A, Withiam-Leitch M, Danakas G, et al. Mastalgia: a review of management. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:933-939.

23. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 164: Diagnosis and management of benign breast disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e141-e156.

24. Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Ahmadpour P, et al. Effects of Vitex agnus and flaxseed on cyclic mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:90-95.

25. Vaziri F, Zamani Lari M, Sansami Dehaghani A, et al. Comparing the effects of dietary flaxseed and omega-3 fatty acids supplement on cyclical mastalgia in Iranian women: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Fam Med. 2014;2014:174532.

26. Sohrabi N, Kashanian M, Ghafoori SS, et al. Evaluation of the effect of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: “a pilot trial”. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:141-146.

27. McFayden IJ, Chetty U, Setchell KD, et al. A randomized double blind-cross over trial of soya protein for the treatment of cyclical breast pain. Breast. 2000;9:271-276.

28. Pruthi S, Wahner-Roedler DL, Torkelson CJ, et al. Vitamin E and evening primrose oil for management of cyclical mastalgia: a randomized pilot study. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15:59-67.

29. Halaska M, Raus K, Beles P, et al. Treatment of cyclical mastodynia using an extract of Vitex agnus castus: results of a double-blind comparison with a placebo. Ceska Gynekol. 1998;63:388-392.

30. Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective randomised placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322:134-137.

31. Goyal A. Breast pain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:0812.

32. Maddox PR, Harrison BJ, Mansel RE. Low-dose danazol for mastalgia. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1989;68:43-47.

33. Ahmadinejad M, Delfan B, Haghdani S, et al. Comparing the effect of diclofenac gel and piroxicam gel on mastalgia. Breast J. 2010;16:213-214.

34. Kontostolis E, Stefanidis K, Navrozoglou I, et al. Comparison of tamoxifen with danazol for treatment of cyclical mastalgia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:393-397.

35. Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3.

36. Nappi C, Affinito P, Di Carlo C, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of progesterone vaginal cream treatment for cyclical mastodynia in women with benign breast disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:801-806.

37. Mansel RE, Goyal A, Preece P, et al. European randomized, multicenter study of goserelin (Zoladex) in the management of mastalgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1942-1949.

38. Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficacy of topical nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:525-530.

39. Goyal A. Breast pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:872-873.

40. Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

41. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Screening. Release date: January 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Accessed August 13, 2019.

1. Salzman B, Fleegle S, Tully AS. Common breast problems. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:343-349.

2. Chetlen AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

3. Expert Panel on Breast Imaging: Jokich PM, Bailey L, D’Orsi C, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Breast Pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S25-S33.

4. Arslan M, Küçükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

5. Smith RL, Pruthi S, Fitzpatrick LA. Evaluation and management of breast pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:353-372.

6. Mansel RE. ABC of breast diseases. Breast pain. BMJ. 1994;309:866-868.

7. Ader DN, South-Paul J, Adera T, et al. Cyclical mastalgia: prevalence and associated health and behavioral factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22:71-76.

8. Iddon J, Dixon JM. Mastalgia. BMJ. 2013;347:f3288.

9. Eren T, Aslan A, Ozemir IA, et al. Factors effecting mastalgia. Breast Care (Basel). 2016;11:188-193.

10. Pearlman MD, Griffin JL. Benign breast disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:747-758.

11. Gateley CA, Mansel RE. The Cardiff Breast Score. Br J Hosp Med. 1991;45:16.

12. Michigan Medicine. University of Michigan. Common breast problems: guidelines for clinical care. https://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/breast/breast.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed September 3, 2019.

13. Millet AV, Dirbas FM. Clinical management of breast pain: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:451-461.

14. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Breast Pain. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3091546/Narrative/. Revised 2018. Accessed July 2, 2019.

15. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Palpable Breast Masses. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69495/Narrative/. Revised 2016. Accessed September 3, 2019.

16. Loving VA, DeMartini WB, Eby PR, et al. Targeted ultrasound in women younger than 30 years with focal breast signs or symptoms: outcomes analyses and management implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1472-1477.

17. Molckovsky A, Fitzgerald B, Freedman O, et al. Approach to inflammatory breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:25-31.

18. Ammari FF, Yaghan RJ, Omari AK. Periductal mastitis: clinical characteristics and outcome. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:819-822.

19. Lannin DR. Twenty-two year experience with recurring subareolar abscess and lactiferous duct fistula treated by a single breast surgeon. Am J Surg. 2004;188:407-410.

20. Wilson JP, Massoll N, Marshall J, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: in search of a therapeutic paradigm. Am Surg. 2007;73:798-802.

21. Bouton ME, Jayaram L, O’Neill PJ, et al. Management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis with observation. Am J Surg. 2015;210:258-262.

22. Olawaiye A, Withiam-Leitch M, Danakas G, et al. Mastalgia: a review of management. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:933-939.

23. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 164: Diagnosis and management of benign breast disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e141-e156.

24. Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Ahmadpour P, et al. Effects of Vitex agnus and flaxseed on cyclic mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:90-95.

25. Vaziri F, Zamani Lari M, Sansami Dehaghani A, et al. Comparing the effects of dietary flaxseed and omega-3 fatty acids supplement on cyclical mastalgia in Iranian women: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Fam Med. 2014;2014:174532.

26. Sohrabi N, Kashanian M, Ghafoori SS, et al. Evaluation of the effect of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: “a pilot trial”. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:141-146.

27. McFayden IJ, Chetty U, Setchell KD, et al. A randomized double blind-cross over trial of soya protein for the treatment of cyclical breast pain. Breast. 2000;9:271-276.

28. Pruthi S, Wahner-Roedler DL, Torkelson CJ, et al. Vitamin E and evening primrose oil for management of cyclical mastalgia: a randomized pilot study. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15:59-67.

29. Halaska M, Raus K, Beles P, et al. Treatment of cyclical mastodynia using an extract of Vitex agnus castus: results of a double-blind comparison with a placebo. Ceska Gynekol. 1998;63:388-392.

30. Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective randomised placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322:134-137.

31. Goyal A. Breast pain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:0812.

32. Maddox PR, Harrison BJ, Mansel RE. Low-dose danazol for mastalgia. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1989;68:43-47.

33. Ahmadinejad M, Delfan B, Haghdani S, et al. Comparing the effect of diclofenac gel and piroxicam gel on mastalgia. Breast J. 2010;16:213-214.

34. Kontostolis E, Stefanidis K, Navrozoglou I, et al. Comparison of tamoxifen with danazol for treatment of cyclical mastalgia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:393-397.

35. Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3.

36. Nappi C, Affinito P, Di Carlo C, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of progesterone vaginal cream treatment for cyclical mastodynia in women with benign breast disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:801-806.

37. Mansel RE, Goyal A, Preece P, et al. European randomized, multicenter study of goserelin (Zoladex) in the management of mastalgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1942-1949.

38. Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficacy of topical nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:525-530.

39. Goyal A. Breast pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:872-873.

40. Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

41. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Screening. Release date: January 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Accessed August 13, 2019.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Instruct patients to maintain a pain diary, which, along with a careful history and physical examination, helps to determine the cause of breast pain and the type of evaluation needed. C

› Treat cyclic, bilateral breast pain with chasteberry and flaxseed. B

› Consider short-term treatment with danazol or tamoxifen for women with severe pain. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CDC, SAMHSA commit $1.8 billion to combat opioid crisis

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.