User login

CDC finds that too little naloxone is dispensed

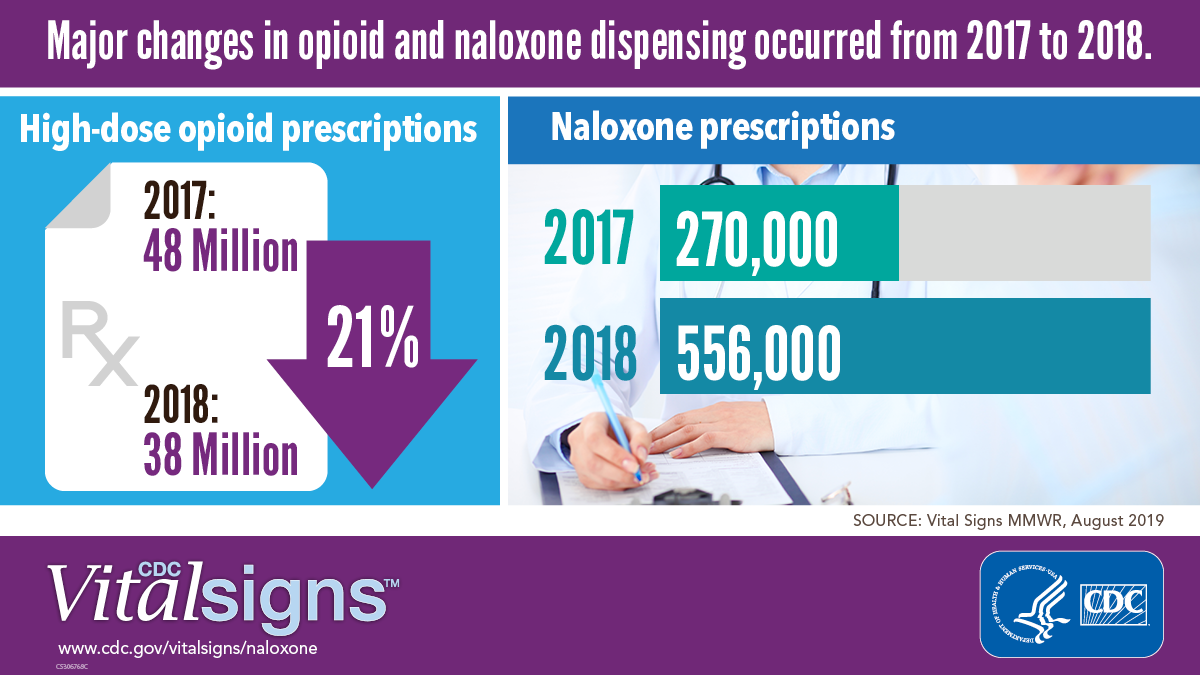

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

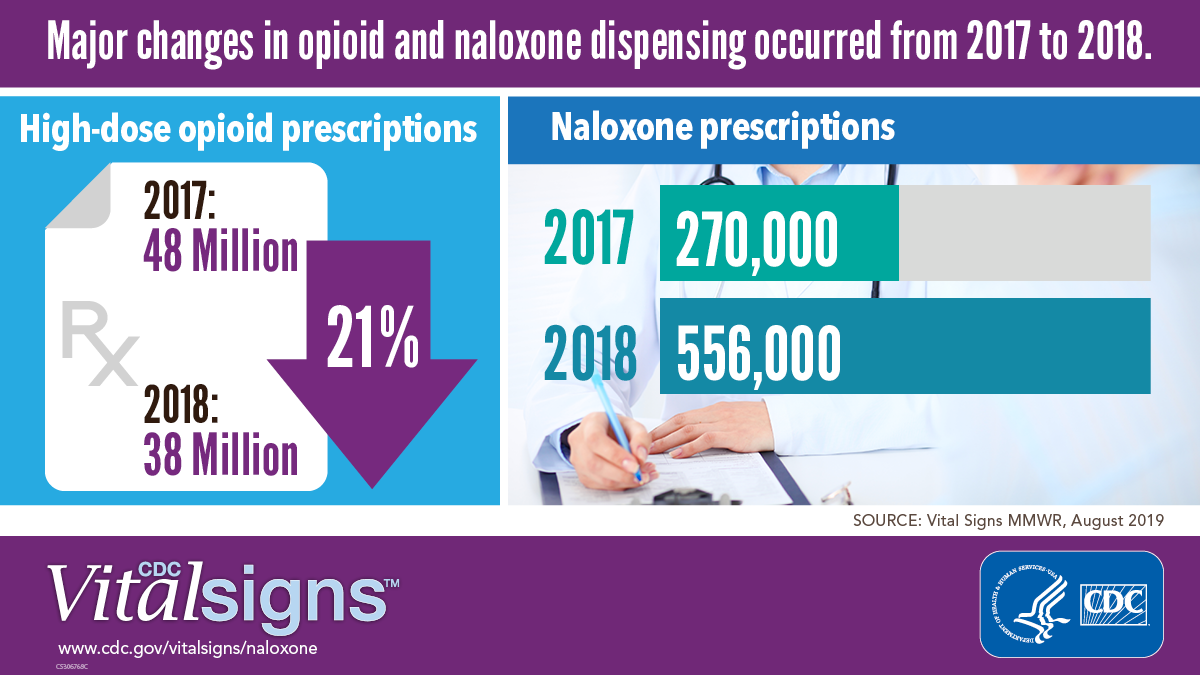

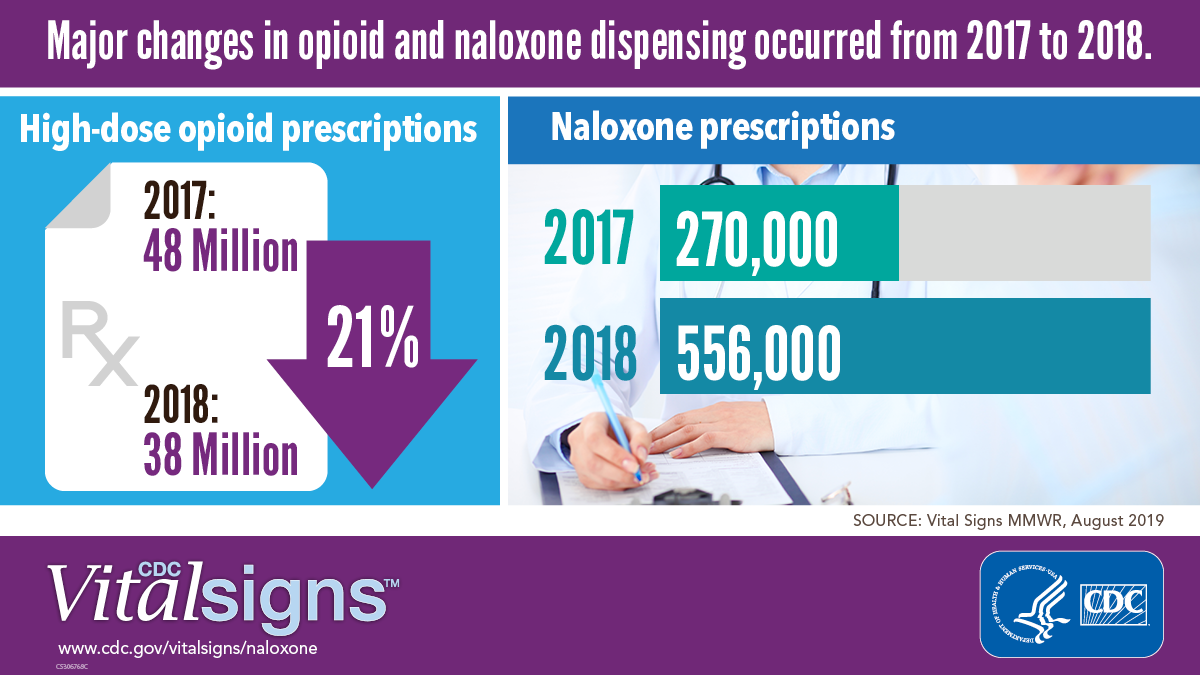

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

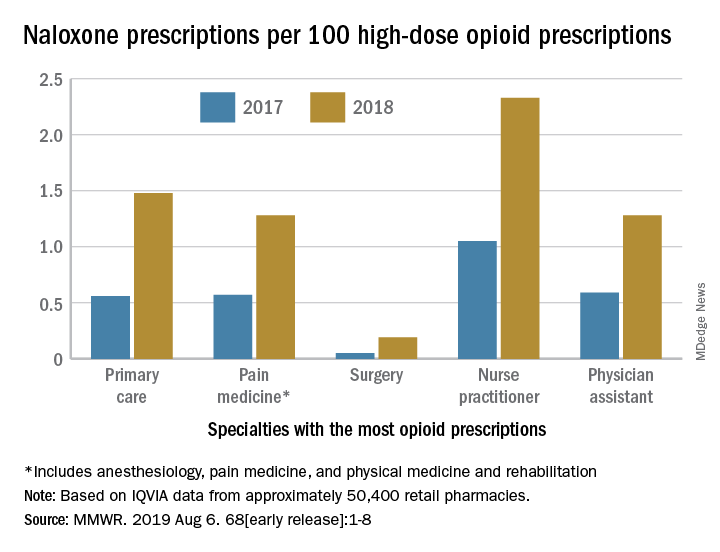

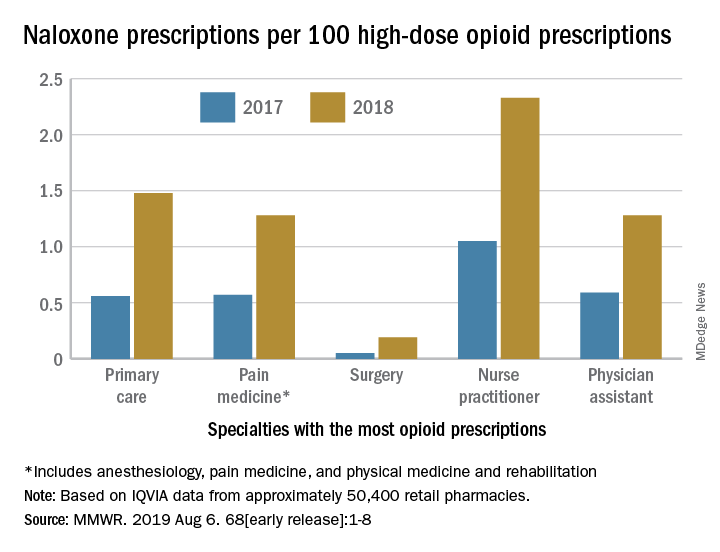

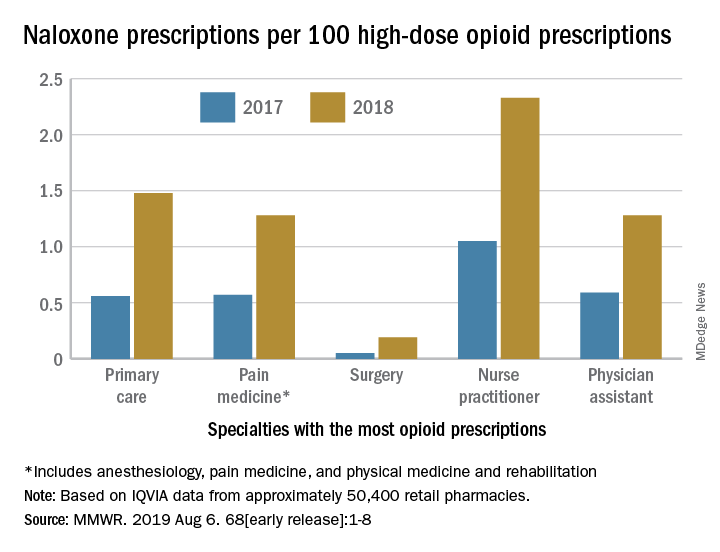

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Preoperative tramadol fails to improve function after knee surgery

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ARTHROPLASTY

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Patients With Low Back Pain

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

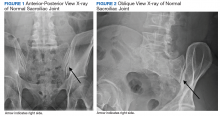

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

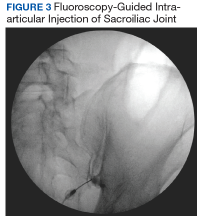

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment

Nonoperative management of SIJ dysfunction includes exercise programs, physical therapy, manual manipulation therapy, sacroiliac belts, and periodic articular injections. Efficacy of these methods is variable, and analgesics often do not significantly benefit this type of pain. Another nonoperative approach is radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the lumbar dorsal rami and lateral sacral branches, which can vary based on the number of rami treated as well as the technique used. About two-thirds of patients report pain relief after RFA.2 When successful, pain is relieved for 6 to 12 months, which is a temporary yet effective option for patients experiencing SIJ dysfunction.14,20

Fusion Surgery

Cadaver studies show that biomechanical stabilization of the SIJ leads to decreased range of motion in flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. This results in a decreased need for periarticular muscular and ligamentous support, therefore facilitating load transfer across the SIJ.21,22 Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery report better pain relief compared with those receiving open surgery at 12 months postoperatively.23 The 2 main SIJ fusion approaches used are the lateral transarticular and the dorsal approaches. In the dorsal approach, the SIJ is distracted and allograft dowels or titanium cages with graft are inserted into the joint space posteriorly through the back. When approaching laterally, hollow screw implants filled with graft or triangular titanium implants are placed across the joint, accessing the SIJ through the iliac bones using imaging guidance. This lateral transiliac approach using porous titanium triangular rods currently is the most studied technique.24

A recent prospective, multicenter trial included 423 patients with SIJ dysfunction who were randomized to receive SIJ fusion with triangular titanium implants vs a control group who received nonoperative management. Patients in the SIJ fusion group showed substantially greater improvement in pain (81.4%) compared with that of the nonoperative group (26.1%) 6 months after surgery. Pain relief in the SIJ fusion group was maintained at > 80% at 1 and 2 year follow-up, while the nonoperative group’s pain relief decreased to < 10% at the follow-ups. Measures of quality of life and disability also improved for the SIJ fusion group compared with that of the nonoperative group. Patients who were crossed over from conservative management to SIJ fusion after 6 months demonstrated improvements that were similar to those in the SIJ fusion group by the end of the study. Only 3% of patients required surgical revision. The strongest predictor of pain relief after surgery was a diagnostic SIJ anesthetic block of 30 to 60 minutes, which resulted in > 75% pain reduction.21,25 Additional predictors of successful SIJ fusion include nonsmokers, nonopioid users, and older patients who have a longer time course of SIJ pain.26

Another study investigating the outcomes of SIJ fusion, RFA, and conservative management with a 6-year follow-up demonstrated similar results.27 This further confirms the durability of the surgical group’s outcome, which sustained significant improvement compared with RFA and conservative management group in pain relief, daily function, and opioid use.

HCPs should consider SIJ fusion for patients who have at least 6 months of unsuccessful nonoperative management, significant SIJ pain (> 5 in a 10-point scale), ≥ 3 positive provocation tests, and at least 50% pain relief (> 75% preferred) with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injection.14 It is reasonable for primary care providers to refer these patients to a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon for possible fusion. Patients with earlier lumbar/lumbosacral spinal fusions and persistent LBP should be evaluated for potential SIJ dysfunction. SIJ dysfunction after lumbosacral fusion could be considered a form of distal pseudarthrosis resulting from increased motion at the joint. One study found its incidence correlated with the number of segments fused in the lumbar spine.28 Another study found that about one-third of patients with persistent LBP after lumbosacral fusion could be attributed to SIJ dysfunction.29

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female army veteran presented with bilateral buttock pain, which she described as a dull, aching pain across her sacral region, 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain was in a L5-S1 pattern. The pain was bilateral, with the right side worse than the left, and worsened with lateral bending and load transferring. She reported no numbness, tingling, or weakness.

On physical examination, she had full strength in her lower extremities and intact sensation. She reported tenderness to palpation of the sacrum and SIJ. Her gait was normal. The patient had positive thigh thrust and distraction tests. Lumbar spine X-ray, CT, MRI, and electromyographic studies did not show any pathology. She described little or no relief with analgesics or physical therapy. Previous L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet anesthetic injections and transforaminal epidural steroid injections provided minimal pain relief immediately after the procedures. Bilateral SIJ anesthetic injections under fluoroscopic guidance decreased her pain severity from a 7 to 3 out of 10 for 2 to 3 months before returning to her baseline. Radiofrequency ablation of the right SIJ under fluoroscopy provided moderate relief for about 4 months.

After exhausting nonoperative management for SIJ dysfunction without adequate pain control, the patient was referred to neurosurgery for surgical fusion. The patient was deemed an appropriate surgical candidate and underwent a right-sided SIJ fusion (Figures 4 and 5). At her 6-month and 1-year follow-up appointments, she had lasting pain relief, 2 out of 10.

Conclusion

SIJ dysfunction is widely overlooked because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other similarly presenting syndromes. However, with a detailed history, appropriate physical maneuvers, imaging, and adequate response to intra-articular anesthetic, providers can reach an accurate diagnosis that will inform subsequent treatments. After failure of nonsurgical methods, patients with SIJ dysfunction should be considered for minimally invasive fusion techniques, which have proven to be a safe, effective, and viable treatment option.

1. Zaidi HA, Montoure AJ, Dickman CA. Surgical and clinical efficacy of sacroiliac joint fusion: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(1):59-66.

2. Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5):1440-1453.

3. Chou LH, Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, et al. Inciting events initiating injection‐proven sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med. 2004;5(1):26-32.

4. Dreyfuss P, Dreyer SJ, Cole A, Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(4):255-265.

5. Buijs E, Visser L, Groen G. Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint: a forgotten concept. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(5):713-716.

6. Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: asymptomatic volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(13):1475-1482.

7. Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):31-37.

8. Fortin JD, Washington WJ, Falco FJ. Three pathways between the sacroiliac joint and neural structures. ANJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(8):1429-1434.

9. Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354-368.

10. Merskey H, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

11. Cusi MF. Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfunction. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(2):152-161.

12. Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207-218.

13. Laslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(3):142-152.

14. Polly DW Jr. The sacroiliac joint. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2017;28(3):301-312.

15. Cusi M, Van Der Wall H, Saunders J, Fogelman I. Metabolic disturbances identified by SPECT-CT in patients with a clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint incompetence. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(7):1674-1682.

16. Tofuku K, Koga H, Komiya S. The diagnostic value of single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography for severe sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(4):859-863.

17. Kennedy DJ, Engel A, Kreiner DS, Nampiaparampil D, Duszynski B, MacVicar J. Fluoroscopically guided diagnostic and therapeutic intra‐articular sacroiliac joint injections: a systematic review. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1500-1518.

18. Schneider BJ, Huynh L, Levin J, Rinkaekan P, Kordi R, Kennedy DJ. Does immediate pain relief after an injection into the sacroiliac joint with anesthetic and corticosteroid predict subsequent pain relief? Pain Med. 2018;19(2):244-251.

19. Murakami E, Tanaka Y, Aizawa T, Ishizuka M, Kokubun S. Effect of periarticular and intraarticular lidocaine injections for sacroiliac joint pain: prospective comparative study. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12(3):274-280.

20. Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Kurihara C, Morlando B, Dragovich A. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(2):279-288.

21. Polly DW, Cher DJ, Wine KD, et al; INSITE Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants vs nonsurgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: 12-month outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(5):674-690.

22. Soriano-Baron H, Lindsey DP, Rodriguez-Martinez N, et al. The effect of implant placement on sacroiliac joint range of motion: posterior versus transarticular. Spine. 2015;40(9):E525-E530.

23. Smith AG, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. Open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a multi-center comparison of perioperative measures and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):14.

24. Rashbaum RF, Ohnmeiss DD, Lindley EM, Kitchel SH, Patel VV. Sacroiliac joint pain and its treatment. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(2):42-48.

25. Polly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, et al. Two-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion vs. non-surgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:28.

26. Dengler J, Duhon B, Whang P, et al. Predictors of outcome in conservative and minimally invasive surgical management of pain originating from the sacroiliac joint: a pooled analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(21):1664-1673.

27. Vanaclocha V, Herrera JM, Sáiz-Sapena N, Rivera-Paz M, Verdú-López F. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, radiofrequency denervation, and conservative management for sacroiliac joint pain: 6-year comparative case series. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(1):48-55.

28. Unoki E, Abe E, Murai H, Kobayashi T, Abe T. Fusion of multiple segments can increase the incidence of sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(12):999-1005.

29. Katz V, Schofferman J, Reynolds J. The sacroiliac joint: a potential cause of pain after lumbar fusion to the sacrum. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):96-99.

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment

Nonoperative management of SIJ dysfunction includes exercise programs, physical therapy, manual manipulation therapy, sacroiliac belts, and periodic articular injections. Efficacy of these methods is variable, and analgesics often do not significantly benefit this type of pain. Another nonoperative approach is radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the lumbar dorsal rami and lateral sacral branches, which can vary based on the number of rami treated as well as the technique used. About two-thirds of patients report pain relief after RFA.2 When successful, pain is relieved for 6 to 12 months, which is a temporary yet effective option for patients experiencing SIJ dysfunction.14,20

Fusion Surgery

Cadaver studies show that biomechanical stabilization of the SIJ leads to decreased range of motion in flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. This results in a decreased need for periarticular muscular and ligamentous support, therefore facilitating load transfer across the SIJ.21,22 Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery report better pain relief compared with those receiving open surgery at 12 months postoperatively.23 The 2 main SIJ fusion approaches used are the lateral transarticular and the dorsal approaches. In the dorsal approach, the SIJ is distracted and allograft dowels or titanium cages with graft are inserted into the joint space posteriorly through the back. When approaching laterally, hollow screw implants filled with graft or triangular titanium implants are placed across the joint, accessing the SIJ through the iliac bones using imaging guidance. This lateral transiliac approach using porous titanium triangular rods currently is the most studied technique.24

A recent prospective, multicenter trial included 423 patients with SIJ dysfunction who were randomized to receive SIJ fusion with triangular titanium implants vs a control group who received nonoperative management. Patients in the SIJ fusion group showed substantially greater improvement in pain (81.4%) compared with that of the nonoperative group (26.1%) 6 months after surgery. Pain relief in the SIJ fusion group was maintained at > 80% at 1 and 2 year follow-up, while the nonoperative group’s pain relief decreased to < 10% at the follow-ups. Measures of quality of life and disability also improved for the SIJ fusion group compared with that of the nonoperative group. Patients who were crossed over from conservative management to SIJ fusion after 6 months demonstrated improvements that were similar to those in the SIJ fusion group by the end of the study. Only 3% of patients required surgical revision. The strongest predictor of pain relief after surgery was a diagnostic SIJ anesthetic block of 30 to 60 minutes, which resulted in > 75% pain reduction.21,25 Additional predictors of successful SIJ fusion include nonsmokers, nonopioid users, and older patients who have a longer time course of SIJ pain.26

Another study investigating the outcomes of SIJ fusion, RFA, and conservative management with a 6-year follow-up demonstrated similar results.27 This further confirms the durability of the surgical group’s outcome, which sustained significant improvement compared with RFA and conservative management group in pain relief, daily function, and opioid use.

HCPs should consider SIJ fusion for patients who have at least 6 months of unsuccessful nonoperative management, significant SIJ pain (> 5 in a 10-point scale), ≥ 3 positive provocation tests, and at least 50% pain relief (> 75% preferred) with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injection.14 It is reasonable for primary care providers to refer these patients to a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon for possible fusion. Patients with earlier lumbar/lumbosacral spinal fusions and persistent LBP should be evaluated for potential SIJ dysfunction. SIJ dysfunction after lumbosacral fusion could be considered a form of distal pseudarthrosis resulting from increased motion at the joint. One study found its incidence correlated with the number of segments fused in the lumbar spine.28 Another study found that about one-third of patients with persistent LBP after lumbosacral fusion could be attributed to SIJ dysfunction.29

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female army veteran presented with bilateral buttock pain, which she described as a dull, aching pain across her sacral region, 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain was in a L5-S1 pattern. The pain was bilateral, with the right side worse than the left, and worsened with lateral bending and load transferring. She reported no numbness, tingling, or weakness.

On physical examination, she had full strength in her lower extremities and intact sensation. She reported tenderness to palpation of the sacrum and SIJ. Her gait was normal. The patient had positive thigh thrust and distraction tests. Lumbar spine X-ray, CT, MRI, and electromyographic studies did not show any pathology. She described little or no relief with analgesics or physical therapy. Previous L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet anesthetic injections and transforaminal epidural steroid injections provided minimal pain relief immediately after the procedures. Bilateral SIJ anesthetic injections under fluoroscopic guidance decreased her pain severity from a 7 to 3 out of 10 for 2 to 3 months before returning to her baseline. Radiofrequency ablation of the right SIJ under fluoroscopy provided moderate relief for about 4 months.

After exhausting nonoperative management for SIJ dysfunction without adequate pain control, the patient was referred to neurosurgery for surgical fusion. The patient was deemed an appropriate surgical candidate and underwent a right-sided SIJ fusion (Figures 4 and 5). At her 6-month and 1-year follow-up appointments, she had lasting pain relief, 2 out of 10.

Conclusion

SIJ dysfunction is widely overlooked because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other similarly presenting syndromes. However, with a detailed history, appropriate physical maneuvers, imaging, and adequate response to intra-articular anesthetic, providers can reach an accurate diagnosis that will inform subsequent treatments. After failure of nonsurgical methods, patients with SIJ dysfunction should be considered for minimally invasive fusion techniques, which have proven to be a safe, effective, and viable treatment option.

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment

Nonoperative management of SIJ dysfunction includes exercise programs, physical therapy, manual manipulation therapy, sacroiliac belts, and periodic articular injections. Efficacy of these methods is variable, and analgesics often do not significantly benefit this type of pain. Another nonoperative approach is radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the lumbar dorsal rami and lateral sacral branches, which can vary based on the number of rami treated as well as the technique used. About two-thirds of patients report pain relief after RFA.2 When successful, pain is relieved for 6 to 12 months, which is a temporary yet effective option for patients experiencing SIJ dysfunction.14,20

Fusion Surgery

Cadaver studies show that biomechanical stabilization of the SIJ leads to decreased range of motion in flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. This results in a decreased need for periarticular muscular and ligamentous support, therefore facilitating load transfer across the SIJ.21,22 Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery report better pain relief compared with those receiving open surgery at 12 months postoperatively.23 The 2 main SIJ fusion approaches used are the lateral transarticular and the dorsal approaches. In the dorsal approach, the SIJ is distracted and allograft dowels or titanium cages with graft are inserted into the joint space posteriorly through the back. When approaching laterally, hollow screw implants filled with graft or triangular titanium implants are placed across the joint, accessing the SIJ through the iliac bones using imaging guidance. This lateral transiliac approach using porous titanium triangular rods currently is the most studied technique.24

A recent prospective, multicenter trial included 423 patients with SIJ dysfunction who were randomized to receive SIJ fusion with triangular titanium implants vs a control group who received nonoperative management. Patients in the SIJ fusion group showed substantially greater improvement in pain (81.4%) compared with that of the nonoperative group (26.1%) 6 months after surgery. Pain relief in the SIJ fusion group was maintained at > 80% at 1 and 2 year follow-up, while the nonoperative group’s pain relief decreased to < 10% at the follow-ups. Measures of quality of life and disability also improved for the SIJ fusion group compared with that of the nonoperative group. Patients who were crossed over from conservative management to SIJ fusion after 6 months demonstrated improvements that were similar to those in the SIJ fusion group by the end of the study. Only 3% of patients required surgical revision. The strongest predictor of pain relief after surgery was a diagnostic SIJ anesthetic block of 30 to 60 minutes, which resulted in > 75% pain reduction.21,25 Additional predictors of successful SIJ fusion include nonsmokers, nonopioid users, and older patients who have a longer time course of SIJ pain.26

Another study investigating the outcomes of SIJ fusion, RFA, and conservative management with a 6-year follow-up demonstrated similar results.27 This further confirms the durability of the surgical group’s outcome, which sustained significant improvement compared with RFA and conservative management group in pain relief, daily function, and opioid use.

HCPs should consider SIJ fusion for patients who have at least 6 months of unsuccessful nonoperative management, significant SIJ pain (> 5 in a 10-point scale), ≥ 3 positive provocation tests, and at least 50% pain relief (> 75% preferred) with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injection.14 It is reasonable for primary care providers to refer these patients to a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon for possible fusion. Patients with earlier lumbar/lumbosacral spinal fusions and persistent LBP should be evaluated for potential SIJ dysfunction. SIJ dysfunction after lumbosacral fusion could be considered a form of distal pseudarthrosis resulting from increased motion at the joint. One study found its incidence correlated with the number of segments fused in the lumbar spine.28 Another study found that about one-third of patients with persistent LBP after lumbosacral fusion could be attributed to SIJ dysfunction.29

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female army veteran presented with bilateral buttock pain, which she described as a dull, aching pain across her sacral region, 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain was in a L5-S1 pattern. The pain was bilateral, with the right side worse than the left, and worsened with lateral bending and load transferring. She reported no numbness, tingling, or weakness.

On physical examination, she had full strength in her lower extremities and intact sensation. She reported tenderness to palpation of the sacrum and SIJ. Her gait was normal. The patient had positive thigh thrust and distraction tests. Lumbar spine X-ray, CT, MRI, and electromyographic studies did not show any pathology. She described little or no relief with analgesics or physical therapy. Previous L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet anesthetic injections and transforaminal epidural steroid injections provided minimal pain relief immediately after the procedures. Bilateral SIJ anesthetic injections under fluoroscopic guidance decreased her pain severity from a 7 to 3 out of 10 for 2 to 3 months before returning to her baseline. Radiofrequency ablation of the right SIJ under fluoroscopy provided moderate relief for about 4 months.

After exhausting nonoperative management for SIJ dysfunction without adequate pain control, the patient was referred to neurosurgery for surgical fusion. The patient was deemed an appropriate surgical candidate and underwent a right-sided SIJ fusion (Figures 4 and 5). At her 6-month and 1-year follow-up appointments, she had lasting pain relief, 2 out of 10.

Conclusion

SIJ dysfunction is widely overlooked because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other similarly presenting syndromes. However, with a detailed history, appropriate physical maneuvers, imaging, and adequate response to intra-articular anesthetic, providers can reach an accurate diagnosis that will inform subsequent treatments. After failure of nonsurgical methods, patients with SIJ dysfunction should be considered for minimally invasive fusion techniques, which have proven to be a safe, effective, and viable treatment option.

1. Zaidi HA, Montoure AJ, Dickman CA. Surgical and clinical efficacy of sacroiliac joint fusion: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(1):59-66.