User login

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

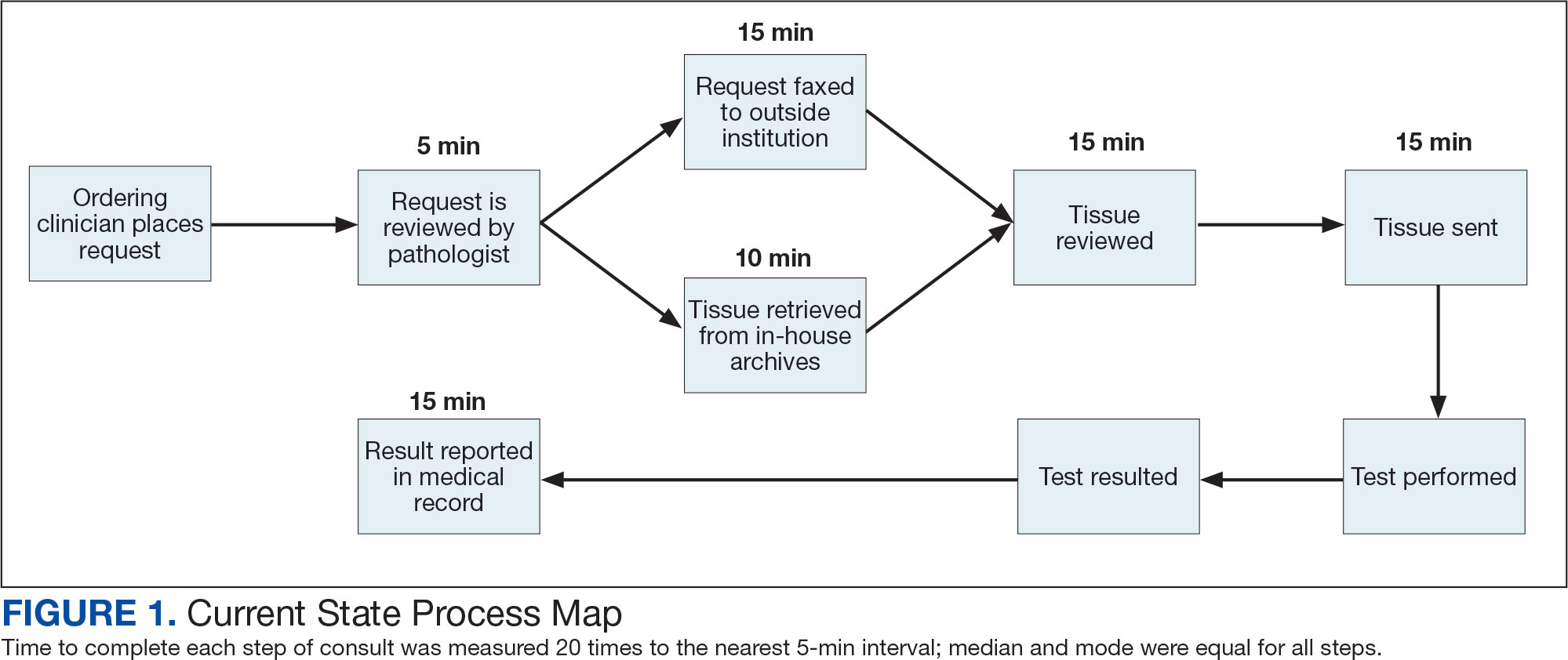

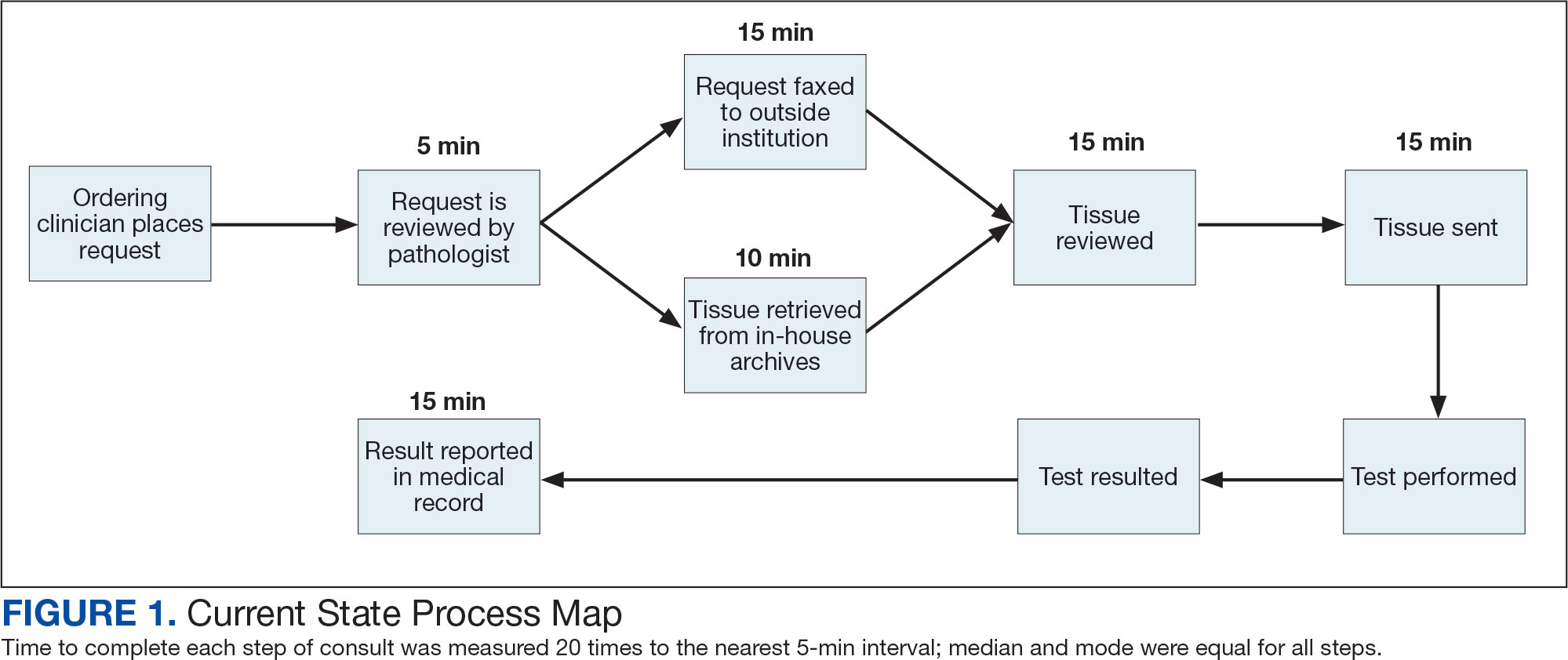

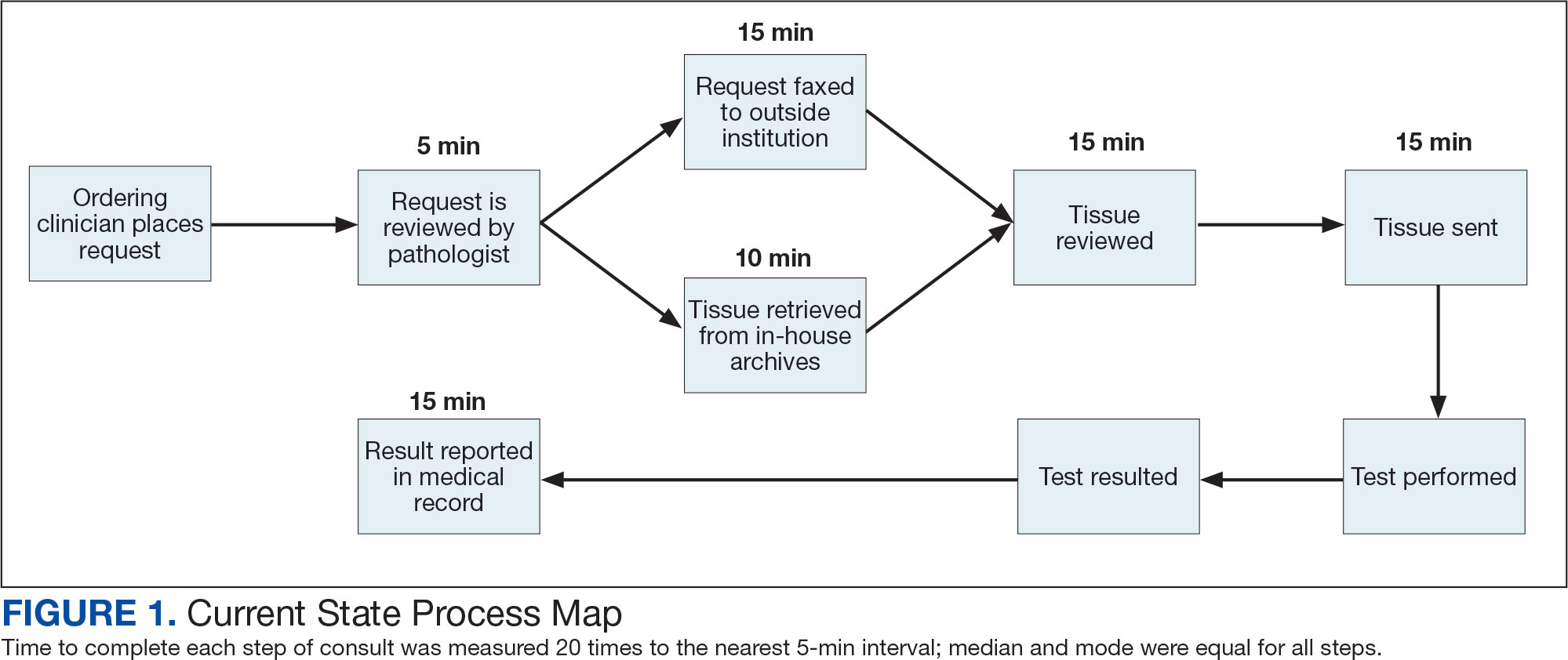

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

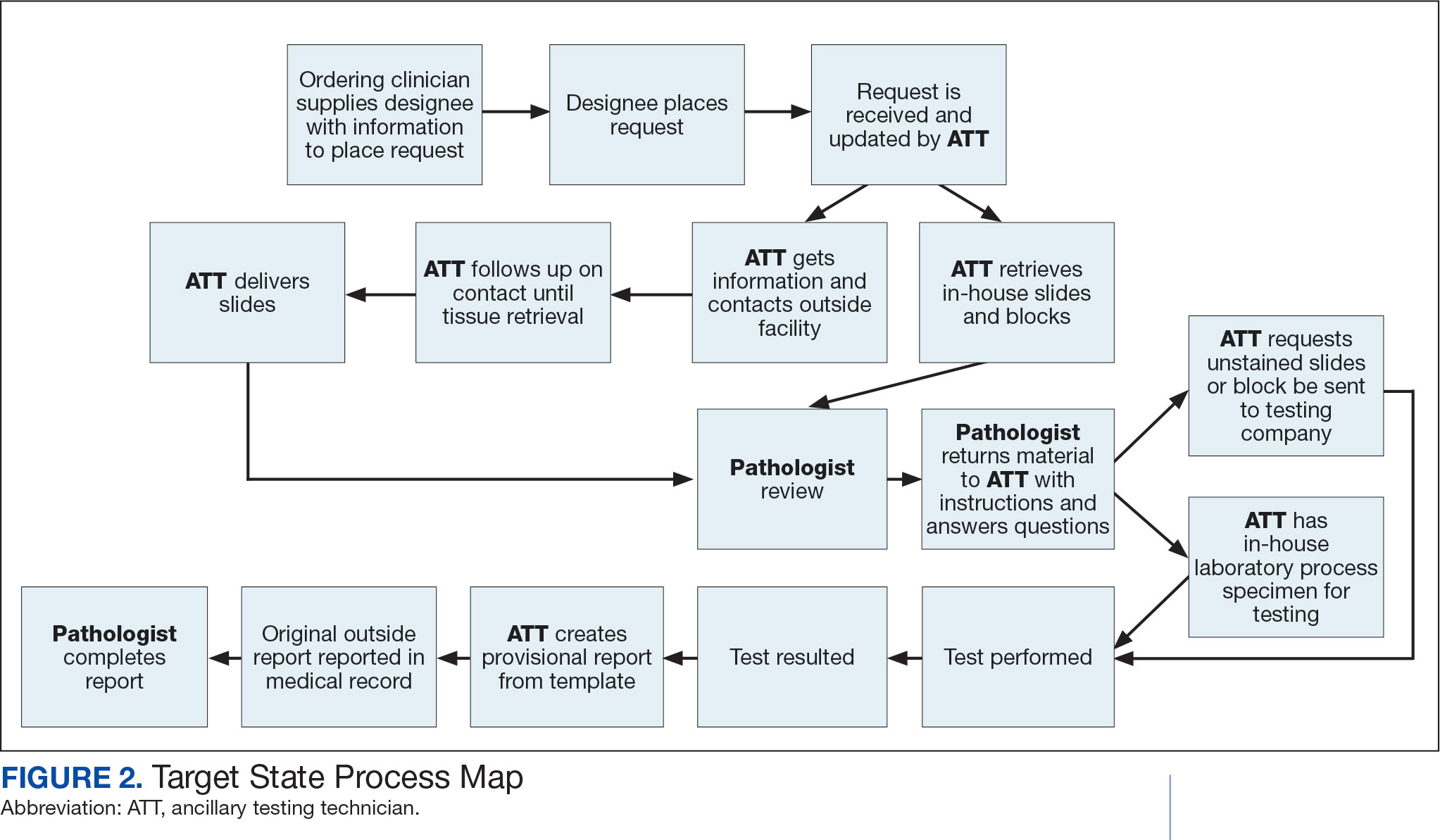

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

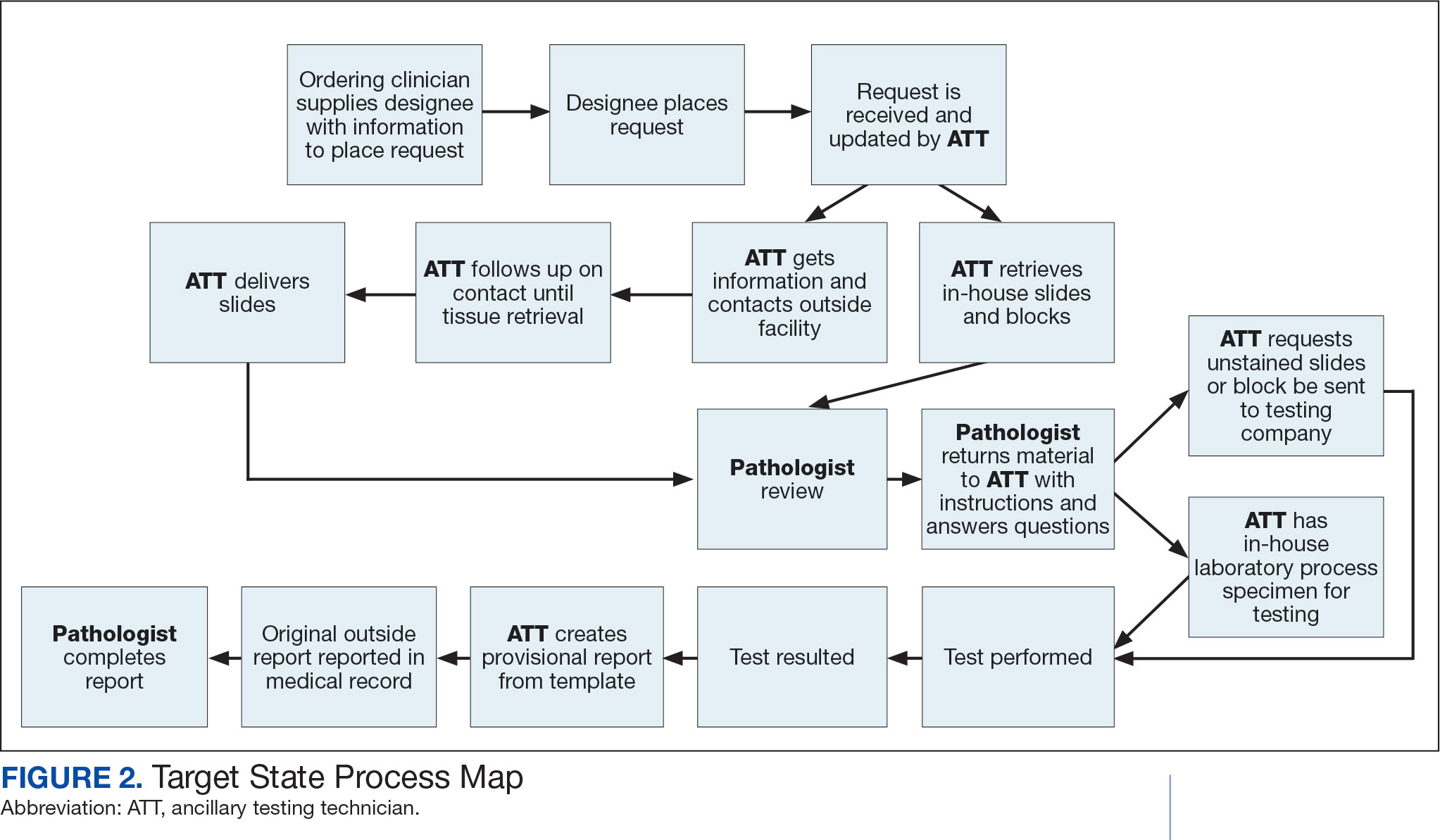

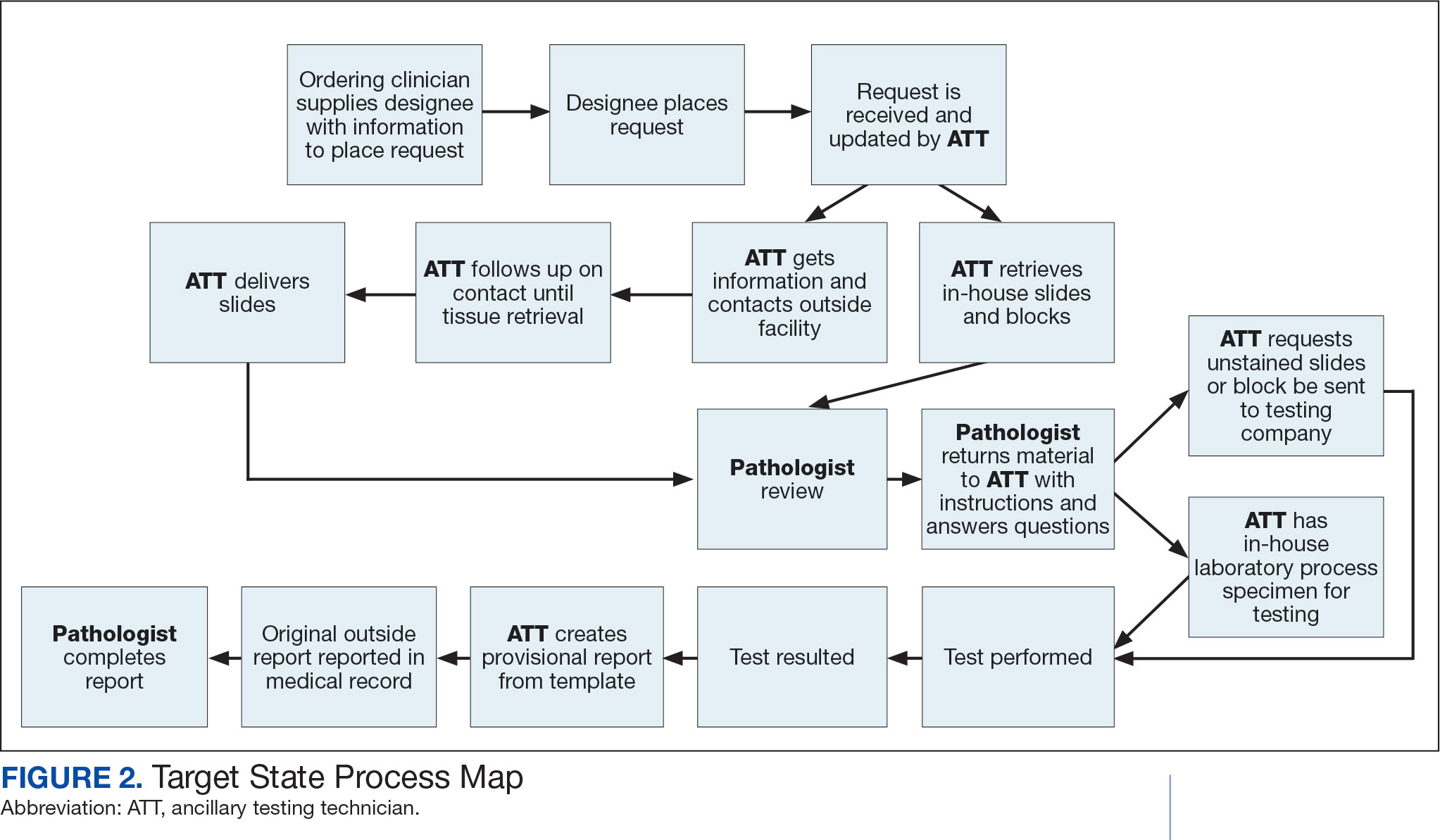

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Exercise Can Help Protect Against Cancer Fatigue, Depression

Lingering fatigue and depression are more common among women than men cancer survivors and often lead to a decrease in recreational physical activities in all patients, new data showed.

However, moderate physical activity was linked to an almost 50% lower risk for cancer-related fatigue, and both moderate and vigorous physical activity were associated with a two- to fivefold reduced risk for depression among cancer survivors, according to the analysis presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2025.

The findings “highlight the importance of providing special attention and tailored interventions such as exercise programs, support groups, and mind-body behavioral techniques for vulnerable groups to help effectively manage fatigue and improve participation in recreational activities as they are an essential aspect of quality of life,” Simo Du, MD, a resident at NYC Health + Hospitals and Jacobi Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, said in a news release.

Du noted that, during her residency, cancer-related fatigue was a common complaint among patients, affecting “not just their daily activities but also their overall quality of life and mental health, making tasks like climbing stairs, doing groceries, or laundry overwhelming.”

Cancer-related fatigue affects more than 80% of patients who receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy, while depression affects around 25% of patients. Unlike typical fatigue, cancer-related fatigue can linger for weeks, months, or even years after treatment, Du explained.

Despite its high prevalence, cancer-related fatigue remains “overlooked and undertreated,” she noted during a conference press briefing. In addition, cancer-related fatigue can affect men and women differently.

To investigate further, Du and her colleagues analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1552 cancer survivors (736 men and 816 women).

After adjusting for age, race, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, women cancer survivors were more likely to experience fatigue (odds ratio [OR], 1.54; P < .017) and depression (OR, 1.32; P = .341) related to their cancer compared with men cancer survivors.

Du said there are likely multiple reasons behind the sex differences observed.

Women may, for instance, be more likely to experience side effects from chemotherapy, radiation, and long-term use of endocrine treatments because of slower drug clearance, which can lead to higher concentrations and a stronger immune response that may heighten inflammatory side effects.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, cancer-related fatigue (OR, 1.93; P = .002) and depression (OR, 2.28; P = .011) were both strongly associated with reduced moderate recreational activities, such as brisk walking, biking, golfing, and light yard work.

The data also showed a protective role for physical activity. For patients who engaged in moderate physical activity, their risk for cancer-related fatigue (OR, 0.52; P = .002) and depression (OR, 0.41; P = .006) was significantly reduced, Du reported.

For depression (but not cancer-related fatigue), “the higher the intensity of physical activity, the higher the protective effects, with almost 4-5 times the reduction of the depression,” Du noted.

Although the NHANES uses standardized protocols designed to minimize biases, Du said a limitation of the current study is the use of self-reported data and the fact that women could potentially overreport fatigue symptoms and men could potentially underreport symptoms of depression.

Looking ahead, Du and her colleagues are planning studies to assess the effectiveness of tailored interventions on cancer-related fatigue and explore the connection between cancer-related fatigue and different mechanisms, such as inflammatory markers, to see if gender modifies the association.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jennifer Ligibel, MD, a senior physician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said that, because the dataset is cross-sectional, it is unclear whether people who were more tired weren’t exercising or if people who weren’t exercising were more tired.

However, Ligibel explained, a huge body of literature has demonstrated that exercise is “the most efficient remedy for fatigue,” and it likely helps with depression too.

In fact, in a recent survey of patients with cancer conducted by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, slightly more than half of patients reported that their oncologist talked about exercise and diet during clinic visits, Ligibel said. Provider recommendations for exercise and diet were associated with positive changes in these behaviors.

“Roughly half of oncologists now give exercise advice; that figure is a lot more than it was a few years ago, but it’s still not universal,” Ligibel said.

The study had no specific funding. Du and Ligibel had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lingering fatigue and depression are more common among women than men cancer survivors and often lead to a decrease in recreational physical activities in all patients, new data showed.

However, moderate physical activity was linked to an almost 50% lower risk for cancer-related fatigue, and both moderate and vigorous physical activity were associated with a two- to fivefold reduced risk for depression among cancer survivors, according to the analysis presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2025.

The findings “highlight the importance of providing special attention and tailored interventions such as exercise programs, support groups, and mind-body behavioral techniques for vulnerable groups to help effectively manage fatigue and improve participation in recreational activities as they are an essential aspect of quality of life,” Simo Du, MD, a resident at NYC Health + Hospitals and Jacobi Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, said in a news release.

Du noted that, during her residency, cancer-related fatigue was a common complaint among patients, affecting “not just their daily activities but also their overall quality of life and mental health, making tasks like climbing stairs, doing groceries, or laundry overwhelming.”

Cancer-related fatigue affects more than 80% of patients who receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy, while depression affects around 25% of patients. Unlike typical fatigue, cancer-related fatigue can linger for weeks, months, or even years after treatment, Du explained.

Despite its high prevalence, cancer-related fatigue remains “overlooked and undertreated,” she noted during a conference press briefing. In addition, cancer-related fatigue can affect men and women differently.

To investigate further, Du and her colleagues analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1552 cancer survivors (736 men and 816 women).

After adjusting for age, race, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, women cancer survivors were more likely to experience fatigue (odds ratio [OR], 1.54; P < .017) and depression (OR, 1.32; P = .341) related to their cancer compared with men cancer survivors.

Du said there are likely multiple reasons behind the sex differences observed.

Women may, for instance, be more likely to experience side effects from chemotherapy, radiation, and long-term use of endocrine treatments because of slower drug clearance, which can lead to higher concentrations and a stronger immune response that may heighten inflammatory side effects.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, cancer-related fatigue (OR, 1.93; P = .002) and depression (OR, 2.28; P = .011) were both strongly associated with reduced moderate recreational activities, such as brisk walking, biking, golfing, and light yard work.

The data also showed a protective role for physical activity. For patients who engaged in moderate physical activity, their risk for cancer-related fatigue (OR, 0.52; P = .002) and depression (OR, 0.41; P = .006) was significantly reduced, Du reported.

For depression (but not cancer-related fatigue), “the higher the intensity of physical activity, the higher the protective effects, with almost 4-5 times the reduction of the depression,” Du noted.

Although the NHANES uses standardized protocols designed to minimize biases, Du said a limitation of the current study is the use of self-reported data and the fact that women could potentially overreport fatigue symptoms and men could potentially underreport symptoms of depression.

Looking ahead, Du and her colleagues are planning studies to assess the effectiveness of tailored interventions on cancer-related fatigue and explore the connection between cancer-related fatigue and different mechanisms, such as inflammatory markers, to see if gender modifies the association.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jennifer Ligibel, MD, a senior physician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said that, because the dataset is cross-sectional, it is unclear whether people who were more tired weren’t exercising or if people who weren’t exercising were more tired.

However, Ligibel explained, a huge body of literature has demonstrated that exercise is “the most efficient remedy for fatigue,” and it likely helps with depression too.

In fact, in a recent survey of patients with cancer conducted by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, slightly more than half of patients reported that their oncologist talked about exercise and diet during clinic visits, Ligibel said. Provider recommendations for exercise and diet were associated with positive changes in these behaviors.

“Roughly half of oncologists now give exercise advice; that figure is a lot more than it was a few years ago, but it’s still not universal,” Ligibel said.

The study had no specific funding. Du and Ligibel had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lingering fatigue and depression are more common among women than men cancer survivors and often lead to a decrease in recreational physical activities in all patients, new data showed.

However, moderate physical activity was linked to an almost 50% lower risk for cancer-related fatigue, and both moderate and vigorous physical activity were associated with a two- to fivefold reduced risk for depression among cancer survivors, according to the analysis presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2025.

The findings “highlight the importance of providing special attention and tailored interventions such as exercise programs, support groups, and mind-body behavioral techniques for vulnerable groups to help effectively manage fatigue and improve participation in recreational activities as they are an essential aspect of quality of life,” Simo Du, MD, a resident at NYC Health + Hospitals and Jacobi Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, said in a news release.

Du noted that, during her residency, cancer-related fatigue was a common complaint among patients, affecting “not just their daily activities but also their overall quality of life and mental health, making tasks like climbing stairs, doing groceries, or laundry overwhelming.”

Cancer-related fatigue affects more than 80% of patients who receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy, while depression affects around 25% of patients. Unlike typical fatigue, cancer-related fatigue can linger for weeks, months, or even years after treatment, Du explained.

Despite its high prevalence, cancer-related fatigue remains “overlooked and undertreated,” she noted during a conference press briefing. In addition, cancer-related fatigue can affect men and women differently.

To investigate further, Du and her colleagues analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1552 cancer survivors (736 men and 816 women).

After adjusting for age, race, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, women cancer survivors were more likely to experience fatigue (odds ratio [OR], 1.54; P < .017) and depression (OR, 1.32; P = .341) related to their cancer compared with men cancer survivors.

Du said there are likely multiple reasons behind the sex differences observed.

Women may, for instance, be more likely to experience side effects from chemotherapy, radiation, and long-term use of endocrine treatments because of slower drug clearance, which can lead to higher concentrations and a stronger immune response that may heighten inflammatory side effects.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, cancer-related fatigue (OR, 1.93; P = .002) and depression (OR, 2.28; P = .011) were both strongly associated with reduced moderate recreational activities, such as brisk walking, biking, golfing, and light yard work.

The data also showed a protective role for physical activity. For patients who engaged in moderate physical activity, their risk for cancer-related fatigue (OR, 0.52; P = .002) and depression (OR, 0.41; P = .006) was significantly reduced, Du reported.

For depression (but not cancer-related fatigue), “the higher the intensity of physical activity, the higher the protective effects, with almost 4-5 times the reduction of the depression,” Du noted.

Although the NHANES uses standardized protocols designed to minimize biases, Du said a limitation of the current study is the use of self-reported data and the fact that women could potentially overreport fatigue symptoms and men could potentially underreport symptoms of depression.

Looking ahead, Du and her colleagues are planning studies to assess the effectiveness of tailored interventions on cancer-related fatigue and explore the connection between cancer-related fatigue and different mechanisms, such as inflammatory markers, to see if gender modifies the association.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jennifer Ligibel, MD, a senior physician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said that, because the dataset is cross-sectional, it is unclear whether people who were more tired weren’t exercising or if people who weren’t exercising were more tired.

However, Ligibel explained, a huge body of literature has demonstrated that exercise is “the most efficient remedy for fatigue,” and it likely helps with depression too.

In fact, in a recent survey of patients with cancer conducted by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, slightly more than half of patients reported that their oncologist talked about exercise and diet during clinic visits, Ligibel said. Provider recommendations for exercise and diet were associated with positive changes in these behaviors.

“Roughly half of oncologists now give exercise advice; that figure is a lot more than it was a few years ago, but it’s still not universal,” Ligibel said.

The study had no specific funding. Du and Ligibel had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AACR 2025

Early Warning Signs: Catching Gastric Cancer in Time

Hello. I’m Dr. David Johnson, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School and Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recently issued a clinical guideline on the diagnosis and management of gastric premalignant conditions.

Coincidentally, earlier this year, the ACG and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) collaborated to issue recommendations on quality indicators for upper endoscopy.

In this overview, I’ll focus on gastric premalignant conditions while drawing upon some of the quality indicators from ACG/ASGE. Together, these publications highlight several things that we may be overlooking and clearly need to do better at addressing, given the emerging data in this area.

Gastric Premalignant Conditions: Increased Risk for Progression

Gastric premalignant conditions are common and include atrophic gastritis, gastric intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and certain gastric epithelial polyps.

The increased risk for progression to gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States is quite striking. It also reveals an important cancer disparity in certain high-risk groups.

The incidence rates of gastric cancer are two- to 13-fold greater in non-White individuals, particularly among immigrants from high-risk areas. The rates exceed those for esophageal cancer and approach those for colorectal cancer. We have had a dramatic oversight in recognizing the risk for gastric carcinoma in underserved areas.

Gastric carcinoma is not a good diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate is 36%. Approximately 40% of cases are metastatic at the time of diagnosis; only about 15% are caught at a curable early stage.

These rates are in far contrast to Asia and areas that do programmatic screening, where the numbers are dramatically reduced. However, in the United States, we’re simply not there yet.

Endoscopic Evaluation

There are three phases of endoscopic evaluation for gastric premalignant conditions on which I’d like to focus: pre-endoscopy, intra-endoscopy, and post-endoscopy.

Pre-endoscopy — that is, before you even put in the endoscope — it’s important to assess patients’ potential risk for certain conditions, regardless of the reason for performing the endoscopy.

Gastric carcinoma is in the top eight leading causes of cancer death in the United States, with the risk being particularly high in Hispanics and Asians.

According to 2020 data, 40 million people living in the United States were born in another country, with over 70% coming from areas that have a high incidence of gastric carcinoma.

Accounting for the increased risk in these groups will become even more important. By 2065, it is projected that Asian and Hispanic individuals — the immigrant groups with the highest risk for gastric cancer — will comprise 70% of the US population. Therefore, we need to do a better job on pre-endoscopic assessment if we want to address this major cancer disparity in the United States.

However, it’s a potentially fixable problem because, in most cases, gastric carcinoma is preceded by a typical asymptomatic precancerous cascade known as the “Correa’s cascade.” It is analogous to what we see in Barrett’s esophagus or even in colorectal neoplasia as it evolves.

This histologic cascade is important to recognize in patients before they get to the stage of progression. Doing so is highly dependent on the assessment prior to the endoscopy.

You should also be thinking about high-risk groups before a pre-endoscopy evaluation.

During intra-endoscopy, it’s important to plan your actions while performing the procedure, even if you are not specifically screening for gastric carcinoma. We must be held accountable to established recommendations, standards, and best practices for accurately defining observations, determining appropriate actions, and effectively implementing screening protocols.

A high-quality evaluation of the gastric mucosa is critically important, as an estimated 5%-11% of neoplastic lesions are missed on upper endoscopy completed within 3 years of a gastric cancer diagnosis. With less-experienced endoscopists, the rate of missed neoplastic lesions may be as high as 25%.

A quality endoscopy begins (as it would in the colon) with mucosal cleaning. This may not be achieved by water alone and requires the use of mucolytic and defoaming agents, such as simethicone or N-acetylcysteine, which can be inordinately helpful.

Complete mucosal evaluation entails using insufflation to adequately distend the gastric folds.

Atrophic gastritis is observed in a high percentage of patients, and I’m always on the lookout for it when performing endoscopies. One way to identify atrophic gastritis is to look for the loss of gastric folds, which has an approximate sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 85%. The increased visibility of the submucosal venules is another sign of atrophic gastritis, although its sensitivity and specificity are relatively lower at 48% and 87%, respectively.

Full photo documentation of the gastric mucosa should be included. It is an important part of the intra-endoscopy procedure and also is mentioned as part of the recently published quality indicators for upper endoscopy from ACG/ASGE.