User login

Obstetric anal sphincter injury: Prevention and repair

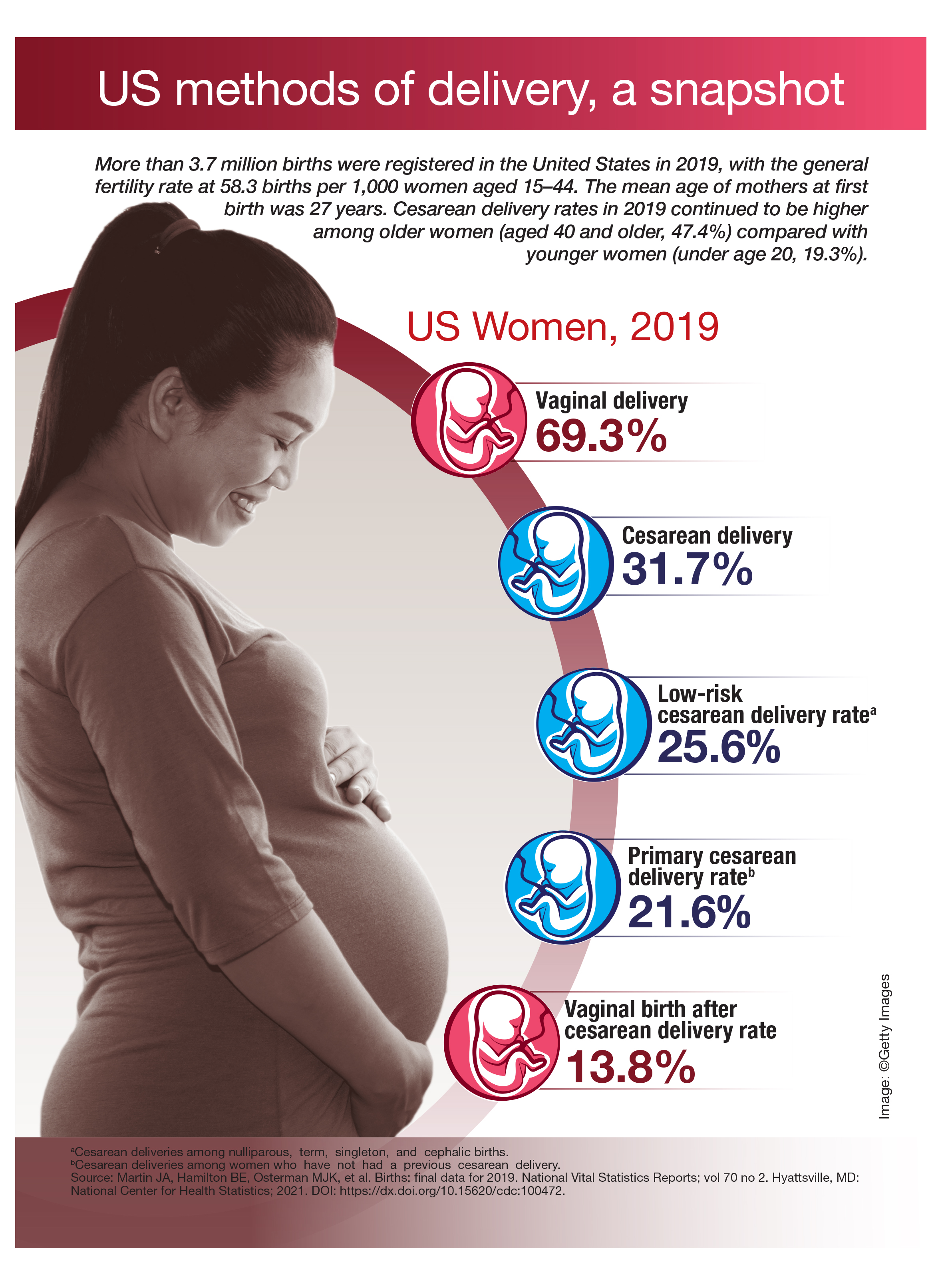

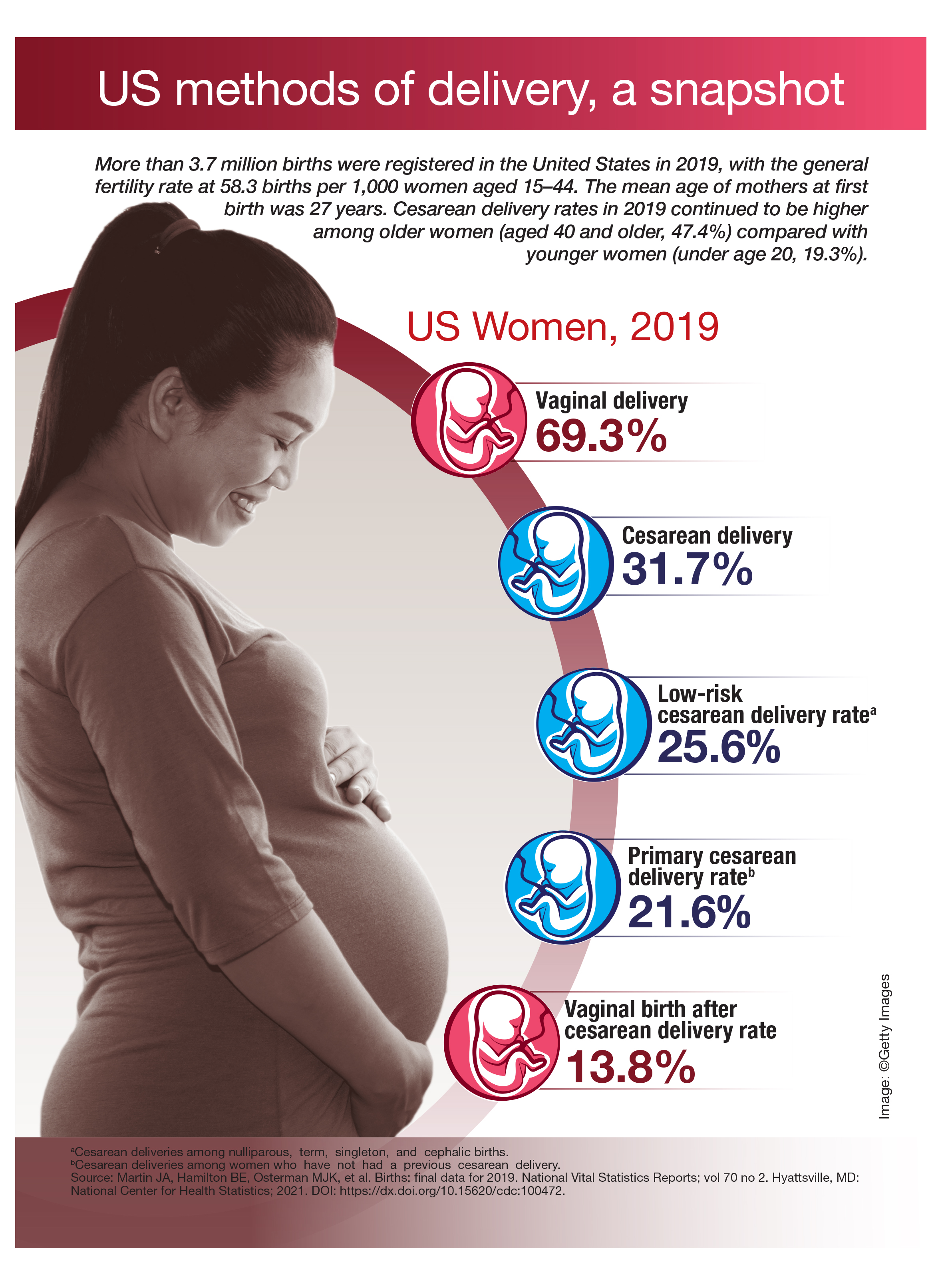

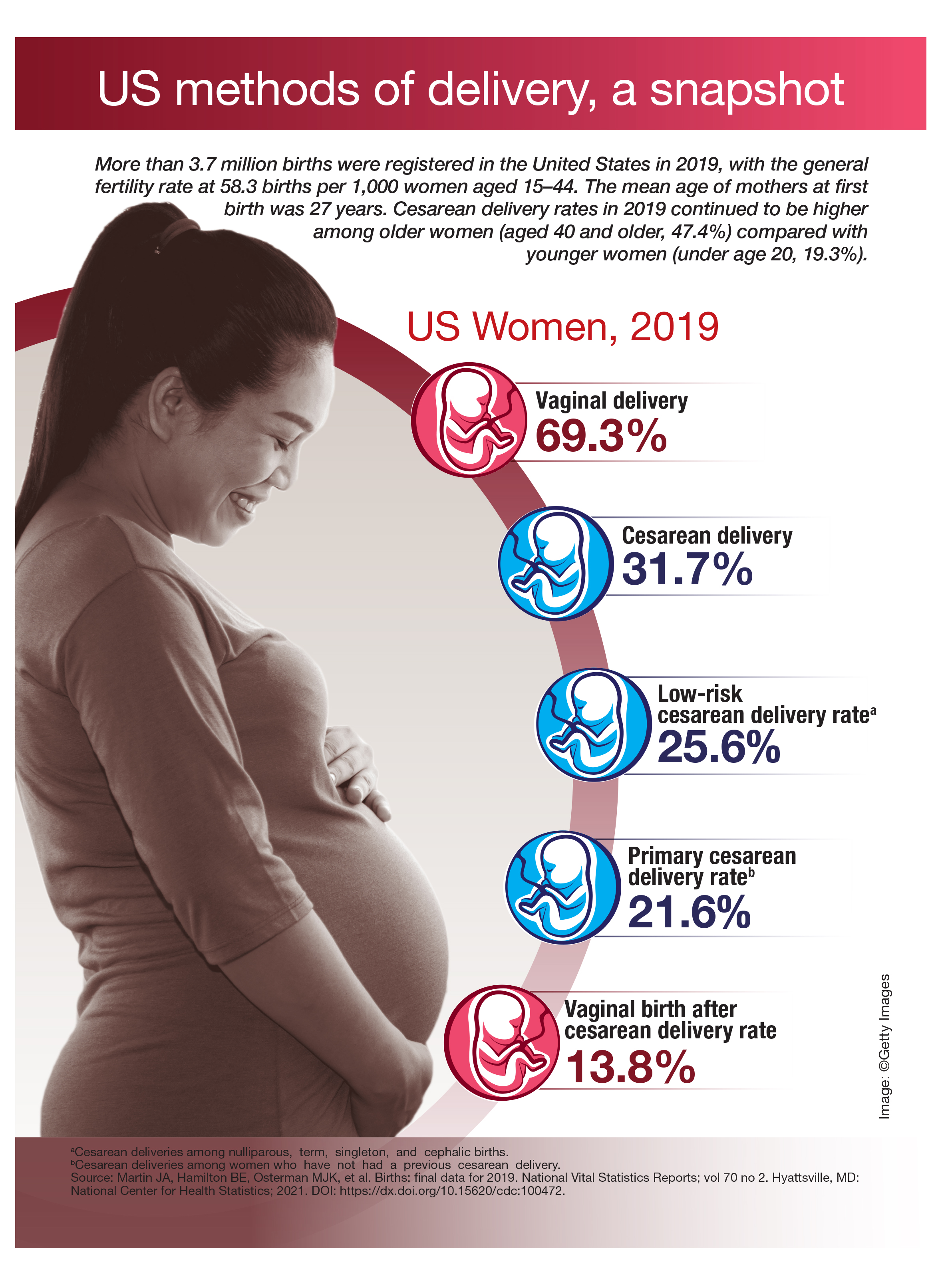

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

The breakdown of an OASIS repair is an obstetric catastrophe with complications that can last many months and sometimes stretch into years. The best approach to a perineal laceration wound breakdown remains controversial. It is optimal if all patients with a wound breakdown can be offered an early secondary repair or healing by secondary intention, permitting the patient to select the best approach for their specific situation.

As noted by the pioneers of early repair of episiotomy dehiscence, Drs. Hankins, Haugh, Gilstrap, Ramin, and others,18-20 conventional doctrine is that an episiotomy repair dehiscence should be managed expectantly, allowing healing by secondary intention and delaying repair of the sphincters for a minimum of 3 to 4 months.21 However, many small case-series report that early secondary repair of a perineal laceration wound breakdown is possible following multiple days of wound preparation prior to the repair, good surgical technique and diligent postoperative follow-up care. One large case series reported on 72 women with complete perineal wound dehiscence who had early secondary repair.22 The median time to complete wound healing following early repair was 28 days. About 36% of the patients had one or more complications, including skin dehiscence, granuloma formation, perineal pain, and sinus formation. A pilot randomized trial reported that, compared with expectant management of a wound breakdown, early repair resulted in a shorter time to wound healing.23

Early repair of perineal wound dehiscence often involves a course of care that extends over multiple weeks. As an example, following a vaginal birth with OASIS and immediate repair, the patient is often discharged from the hospital to home on postpartum day 3. The wound breakdown often is detected between postpartum days 6 to 10. If early secondary repair is selected as the best treatment, 1 to 6 days of daily debridement of the wound is needed to prepare the wound for early secondary repair. The daily debridement required to prepare the wound for early repair is often performed in the hospital, potentially disrupting early mother-newborn bonding. Following the repair, the patient is observed in the hospital for 1 to 3 days and then discharged home with daily wound care and multiple follow-up visits to monitor wound healing. Pelvic floor physical therapy may be initiated when the wound is healed. The prolonged process required for early secondary repair may be best undertaken by a subspecialty practice.24

The surgical repair and postpartum care of OASIS continues to evolve. In your practice you should consider:

- performing a mediolateral episiotomy at a 60-degree angle to reduce the risk of OASIS in situations where there is a high risk of anal sphincter injury, such as in forceps delivery

- using one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobic coverage, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin

- focus on identifying and separately repairing an internal anal sphincter injury

- using a long-lasting absorbable suture, such as PDS, to repair the internal and external anal sphincters

- ensuring that the patient with a dehiscence following an episiotomy or anal sphincter injury has access to early secondary repair. Standardizing your approach to the prevention and repair of anal sphincter injury will benefit the approximately 112,600 US women who experience OASIS each year. ●

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review reported that moderate-quality evidence showed a decrease in OASIS with the use of intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum and perineal massage.1 Compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum did not result in a reduction in first- or second-degree tears, suturing of perineal tears, or use of episiotomy. However, compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum was associated with a reduction in OASIS (relative risk [RR], 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.27–0.79; 1,799 women; 4 studies; moderate quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies). In addition to a possible reduction in OASIS, warm compresses also may provide the laboring woman, especially those having a natural childbirth, a positive sensory experience and reinforce her perception of the thoughtfulness and caring of her clinicians.

Compared with control, perineal massage was associated with an increase in the rate of an intact perineum (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11–2.73; 6 studies; 2,618 women; low-quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies) and a decrease in OASIS (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.94; 5 studies; 2,477 women; moderate quality evidence). Compared with control, perineal massage did not significantly reduce first- or second-degree tears, perineal tears requiring suturing, or the use of episiotomy (very low-quality evidence). Although perineal massage may have benefit, excessive perineal massage likely can contribute to tissue edema and epithelial trauma.

Reference

1. Aasheim V, Nilsen ABC, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD006672.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, et al. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:927-937.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MK. Births: Provisional data for 2019. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; No. 8. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf

- Pergialitotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, et al. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth: an updated meta-analysis. European J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;247:94-100.

- Sultan AH, Kettle C. Diagnosis of perineal trauma. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE, eds. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. 1st ed. London, England: Springer-Verlag; 2009:33-51.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD000081.

- Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, et al. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:408-412.

- Sooklim R, Thinkhamrop J, Lumbiganon P, et al. The outcomes of midline versus medio-lateral episiotomy. Reprod Health. 2007;4:10.

- El-Din AS, Kamal MM, Amin MA. Comparison between two incision angles of mediolateral episiotomy in primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1877-1882.

- Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1268-1273.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2015;37:1131-1148.

- Cox CK, Bugosh MD, Fenner DE, et al. Antibiotic use during repair of obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a qualitative improvement initiative. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; Epub January 28.

- Deierhoi RJ, Dawes LG, Vick C, et al. Choice of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery does matter. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:763-769.

- Till Sr, Morgan DM, Bazzi AA, et al. Reducing surgical site infections after hysterectomy: metronidazole plus cefazolin compared with cephalosporin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:187.e1-e11.

- Pihl S, Blomberg M, Uustal E. Internal anal sphincter injury in the immediate postpartum period: prevalence, risk factors and diagnostic methods in the Swedish perineal laceration registry. European J Obst Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;245:1-6.

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjodahl R, et al. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long-term effects. BJOG. 2005;112:312-316.

- Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, et al. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318-323.

- Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, et al. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:201-207.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, Ward SC, et al. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:806-809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:48-51.

- Ramin SR, Ramus RM, Little BB, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1104-1107.

- Pritchard JA, MacDonald PC, Gant NF. Williams Obstetrics, 17th ed. Norwalk Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985:349-350.

- Okeahialam NA, Thakar R, Kleprlikova H, et al. Early re-suturing of dehisced obstetric perineal woulds: a 13-year experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;254:69-73.

- Dudley L, Kettle C, Thomas PW, et al. Perineal resuturing versus expectant management following vaginal delivery complicated by a dehisced wound (PREVIEW): a pilot and feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012766.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

The breakdown of an OASIS repair is an obstetric catastrophe with complications that can last many months and sometimes stretch into years. The best approach to a perineal laceration wound breakdown remains controversial. It is optimal if all patients with a wound breakdown can be offered an early secondary repair or healing by secondary intention, permitting the patient to select the best approach for their specific situation.

As noted by the pioneers of early repair of episiotomy dehiscence, Drs. Hankins, Haugh, Gilstrap, Ramin, and others,18-20 conventional doctrine is that an episiotomy repair dehiscence should be managed expectantly, allowing healing by secondary intention and delaying repair of the sphincters for a minimum of 3 to 4 months.21 However, many small case-series report that early secondary repair of a perineal laceration wound breakdown is possible following multiple days of wound preparation prior to the repair, good surgical technique and diligent postoperative follow-up care. One large case series reported on 72 women with complete perineal wound dehiscence who had early secondary repair.22 The median time to complete wound healing following early repair was 28 days. About 36% of the patients had one or more complications, including skin dehiscence, granuloma formation, perineal pain, and sinus formation. A pilot randomized trial reported that, compared with expectant management of a wound breakdown, early repair resulted in a shorter time to wound healing.23

Early repair of perineal wound dehiscence often involves a course of care that extends over multiple weeks. As an example, following a vaginal birth with OASIS and immediate repair, the patient is often discharged from the hospital to home on postpartum day 3. The wound breakdown often is detected between postpartum days 6 to 10. If early secondary repair is selected as the best treatment, 1 to 6 days of daily debridement of the wound is needed to prepare the wound for early secondary repair. The daily debridement required to prepare the wound for early repair is often performed in the hospital, potentially disrupting early mother-newborn bonding. Following the repair, the patient is observed in the hospital for 1 to 3 days and then discharged home with daily wound care and multiple follow-up visits to monitor wound healing. Pelvic floor physical therapy may be initiated when the wound is healed. The prolonged process required for early secondary repair may be best undertaken by a subspecialty practice.24

The surgical repair and postpartum care of OASIS continues to evolve. In your practice you should consider:

- performing a mediolateral episiotomy at a 60-degree angle to reduce the risk of OASIS in situations where there is a high risk of anal sphincter injury, such as in forceps delivery

- using one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobic coverage, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin

- focus on identifying and separately repairing an internal anal sphincter injury

- using a long-lasting absorbable suture, such as PDS, to repair the internal and external anal sphincters

- ensuring that the patient with a dehiscence following an episiotomy or anal sphincter injury has access to early secondary repair. Standardizing your approach to the prevention and repair of anal sphincter injury will benefit the approximately 112,600 US women who experience OASIS each year. ●

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review reported that moderate-quality evidence showed a decrease in OASIS with the use of intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum and perineal massage.1 Compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum did not result in a reduction in first- or second-degree tears, suturing of perineal tears, or use of episiotomy. However, compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum was associated with a reduction in OASIS (relative risk [RR], 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.27–0.79; 1,799 women; 4 studies; moderate quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies). In addition to a possible reduction in OASIS, warm compresses also may provide the laboring woman, especially those having a natural childbirth, a positive sensory experience and reinforce her perception of the thoughtfulness and caring of her clinicians.

Compared with control, perineal massage was associated with an increase in the rate of an intact perineum (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11–2.73; 6 studies; 2,618 women; low-quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies) and a decrease in OASIS (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.94; 5 studies; 2,477 women; moderate quality evidence). Compared with control, perineal massage did not significantly reduce first- or second-degree tears, perineal tears requiring suturing, or the use of episiotomy (very low-quality evidence). Although perineal massage may have benefit, excessive perineal massage likely can contribute to tissue edema and epithelial trauma.

Reference

1. Aasheim V, Nilsen ABC, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD006672.

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

The breakdown of an OASIS repair is an obstetric catastrophe with complications that can last many months and sometimes stretch into years. The best approach to a perineal laceration wound breakdown remains controversial. It is optimal if all patients with a wound breakdown can be offered an early secondary repair or healing by secondary intention, permitting the patient to select the best approach for their specific situation.

As noted by the pioneers of early repair of episiotomy dehiscence, Drs. Hankins, Haugh, Gilstrap, Ramin, and others,18-20 conventional doctrine is that an episiotomy repair dehiscence should be managed expectantly, allowing healing by secondary intention and delaying repair of the sphincters for a minimum of 3 to 4 months.21 However, many small case-series report that early secondary repair of a perineal laceration wound breakdown is possible following multiple days of wound preparation prior to the repair, good surgical technique and diligent postoperative follow-up care. One large case series reported on 72 women with complete perineal wound dehiscence who had early secondary repair.22 The median time to complete wound healing following early repair was 28 days. About 36% of the patients had one or more complications, including skin dehiscence, granuloma formation, perineal pain, and sinus formation. A pilot randomized trial reported that, compared with expectant management of a wound breakdown, early repair resulted in a shorter time to wound healing.23

Early repair of perineal wound dehiscence often involves a course of care that extends over multiple weeks. As an example, following a vaginal birth with OASIS and immediate repair, the patient is often discharged from the hospital to home on postpartum day 3. The wound breakdown often is detected between postpartum days 6 to 10. If early secondary repair is selected as the best treatment, 1 to 6 days of daily debridement of the wound is needed to prepare the wound for early secondary repair. The daily debridement required to prepare the wound for early repair is often performed in the hospital, potentially disrupting early mother-newborn bonding. Following the repair, the patient is observed in the hospital for 1 to 3 days and then discharged home with daily wound care and multiple follow-up visits to monitor wound healing. Pelvic floor physical therapy may be initiated when the wound is healed. The prolonged process required for early secondary repair may be best undertaken by a subspecialty practice.24

The surgical repair and postpartum care of OASIS continues to evolve. In your practice you should consider:

- performing a mediolateral episiotomy at a 60-degree angle to reduce the risk of OASIS in situations where there is a high risk of anal sphincter injury, such as in forceps delivery

- using one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobic coverage, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin

- focus on identifying and separately repairing an internal anal sphincter injury

- using a long-lasting absorbable suture, such as PDS, to repair the internal and external anal sphincters

- ensuring that the patient with a dehiscence following an episiotomy or anal sphincter injury has access to early secondary repair. Standardizing your approach to the prevention and repair of anal sphincter injury will benefit the approximately 112,600 US women who experience OASIS each year. ●

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review reported that moderate-quality evidence showed a decrease in OASIS with the use of intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum and perineal massage.1 Compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum did not result in a reduction in first- or second-degree tears, suturing of perineal tears, or use of episiotomy. However, compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum was associated with a reduction in OASIS (relative risk [RR], 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.27–0.79; 1,799 women; 4 studies; moderate quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies). In addition to a possible reduction in OASIS, warm compresses also may provide the laboring woman, especially those having a natural childbirth, a positive sensory experience and reinforce her perception of the thoughtfulness and caring of her clinicians.

Compared with control, perineal massage was associated with an increase in the rate of an intact perineum (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11–2.73; 6 studies; 2,618 women; low-quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies) and a decrease in OASIS (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.94; 5 studies; 2,477 women; moderate quality evidence). Compared with control, perineal massage did not significantly reduce first- or second-degree tears, perineal tears requiring suturing, or the use of episiotomy (very low-quality evidence). Although perineal massage may have benefit, excessive perineal massage likely can contribute to tissue edema and epithelial trauma.

Reference

1. Aasheim V, Nilsen ABC, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD006672.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, et al. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:927-937.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MK. Births: Provisional data for 2019. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; No. 8. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf

- Pergialitotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, et al. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth: an updated meta-analysis. European J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;247:94-100.

- Sultan AH, Kettle C. Diagnosis of perineal trauma. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE, eds. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. 1st ed. London, England: Springer-Verlag; 2009:33-51.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD000081.

- Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, et al. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:408-412.

- Sooklim R, Thinkhamrop J, Lumbiganon P, et al. The outcomes of midline versus medio-lateral episiotomy. Reprod Health. 2007;4:10.

- El-Din AS, Kamal MM, Amin MA. Comparison between two incision angles of mediolateral episiotomy in primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1877-1882.

- Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1268-1273.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2015;37:1131-1148.

- Cox CK, Bugosh MD, Fenner DE, et al. Antibiotic use during repair of obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a qualitative improvement initiative. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; Epub January 28.

- Deierhoi RJ, Dawes LG, Vick C, et al. Choice of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery does matter. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:763-769.

- Till Sr, Morgan DM, Bazzi AA, et al. Reducing surgical site infections after hysterectomy: metronidazole plus cefazolin compared with cephalosporin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:187.e1-e11.

- Pihl S, Blomberg M, Uustal E. Internal anal sphincter injury in the immediate postpartum period: prevalence, risk factors and diagnostic methods in the Swedish perineal laceration registry. European J Obst Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;245:1-6.

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjodahl R, et al. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long-term effects. BJOG. 2005;112:312-316.

- Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, et al. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318-323.

- Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, et al. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:201-207.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, Ward SC, et al. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:806-809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:48-51.

- Ramin SR, Ramus RM, Little BB, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1104-1107.

- Pritchard JA, MacDonald PC, Gant NF. Williams Obstetrics, 17th ed. Norwalk Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985:349-350.

- Okeahialam NA, Thakar R, Kleprlikova H, et al. Early re-suturing of dehisced obstetric perineal woulds: a 13-year experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;254:69-73.

- Dudley L, Kettle C, Thomas PW, et al. Perineal resuturing versus expectant management following vaginal delivery complicated by a dehisced wound (PREVIEW): a pilot and feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012766.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, et al. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:927-937.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MK. Births: Provisional data for 2019. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; No. 8. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf

- Pergialitotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, et al. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth: an updated meta-analysis. European J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;247:94-100.

- Sultan AH, Kettle C. Diagnosis of perineal trauma. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE, eds. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. 1st ed. London, England: Springer-Verlag; 2009:33-51.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD000081.

- Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, et al. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:408-412.

- Sooklim R, Thinkhamrop J, Lumbiganon P, et al. The outcomes of midline versus medio-lateral episiotomy. Reprod Health. 2007;4:10.

- El-Din AS, Kamal MM, Amin MA. Comparison between two incision angles of mediolateral episiotomy in primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1877-1882.

- Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1268-1273.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2015;37:1131-1148.

- Cox CK, Bugosh MD, Fenner DE, et al. Antibiotic use during repair of obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a qualitative improvement initiative. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; Epub January 28.

- Deierhoi RJ, Dawes LG, Vick C, et al. Choice of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery does matter. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:763-769.

- Till Sr, Morgan DM, Bazzi AA, et al. Reducing surgical site infections after hysterectomy: metronidazole plus cefazolin compared with cephalosporin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:187.e1-e11.

- Pihl S, Blomberg M, Uustal E. Internal anal sphincter injury in the immediate postpartum period: prevalence, risk factors and diagnostic methods in the Swedish perineal laceration registry. European J Obst Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;245:1-6.

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjodahl R, et al. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long-term effects. BJOG. 2005;112:312-316.

- Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, et al. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318-323.

- Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, et al. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:201-207.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, Ward SC, et al. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:806-809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:48-51.

- Ramin SR, Ramus RM, Little BB, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1104-1107.

- Pritchard JA, MacDonald PC, Gant NF. Williams Obstetrics, 17th ed. Norwalk Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985:349-350.

- Okeahialam NA, Thakar R, Kleprlikova H, et al. Early re-suturing of dehisced obstetric perineal woulds: a 13-year experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;254:69-73.

- Dudley L, Kettle C, Thomas PW, et al. Perineal resuturing versus expectant management following vaginal delivery complicated by a dehisced wound (PREVIEW): a pilot and feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012766.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

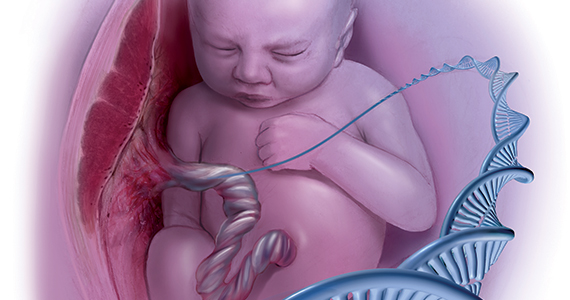

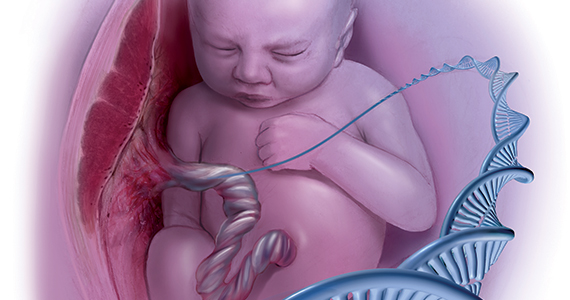

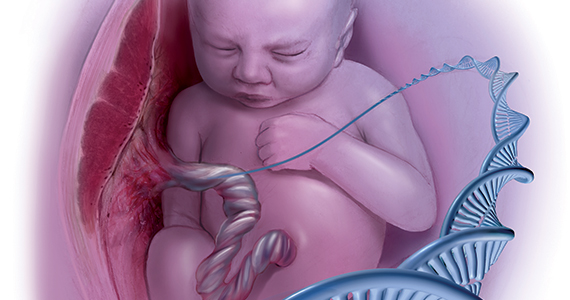

Genetic variants account for up to one-third of cases of cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of severe neurodisability in children, and it occurs in about 2 to 3 per 1,000 births worldwide.1 This nonprogressive disorder is characterized by symptoms that include spasticity, dystonia, choreoathetosis, and/or ataxia that are evident in the first few years of life. While many perinatal variables have been associated with CP, in most cases a specific cause is not identified.

Other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder, are often associated with CP.2 These other neurodevelopmental disorders are often genetic, and this has raised the question as to whether CP also might have a substantial genetic component, although this has not been investigated in any significant way until recently. This topic is of great interest to the obstetric community, given that CP often is attributed to obstetric events, including mismanagement of labor and delivery.

Emerging evidence of a genetic-CP association

In an article published recently in JAMA, Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues sought to determine the diagnostic yield of exome sequencing for CP.3 This large cross-sectional study included results of exome sequencing performed in 2 settings. The first setting was a commercial laboratory in which samples were sent for analysis due to a diagnosis of CP, primarily in children (n = 1,345) with a median age of 8.8 years. A second cohort, recruited from a neurodevelopmental disorders clinic at Geisinger, included primarily adults (n = 181) with a median age of 41.9 years.

As is standard in exome sequencing, results were considered likely causative if they were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic based on criteria of the American College of Genetics and Genomics. In the laboratory group, 32.7% (440 of 1,345) had a genetic cause of the CP identified, while in the clinic group, 10.5% (19 of 181) had a genetic etiology found. Although most of the identified genetic variants were de novo (that is, they arose in the affected individual and were not clearly inherited), some were inherited from carrier parents.3

A number of other recent studies also have investigated genetic causes of CP and similarly have reported that a substantial number of cases are genetic. Several studies that performed chromosomal microarray analysis in individuals with CP found deleterious copy number variants in 10% to 31% of cases.4-6 Genomic variants detectable by exome sequencing have been reported in 15% to 20% of cases.3 In a recent study in Nature Genetics, researchers performed exome sequencing on 250 parent-child “trios” in which the child had CP, and they found that 14% of cases had an associated genetic variant that was thought to be causative.4 These studies all provide consistent evidence that a substantial proportion of CP cases are due to genetic causes.

Contributors to CP risk

Historically, CP was considered to occur largely as a result of perinatal anoxia. In 1862, the British orthopedic surgeon William John Little first reported an association between prematurity, asphyxia, difficult delivery, and CP in a paper presented to the Obstetrical Society of London.7 Subsequently, much effort has gone into the prevention of perinatal asphyxia and birth injury, although our ability to monitor fetal well-being remains limited. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are nonspecific and can occur for many reasons other than fetal asphyxia. Studies of electronic fetal monitoring have found that continuous monitoring primarily leads to an increase in cesarean delivery with no decrease in CP or infant mortality.8

While some have attributed this to failure to accurately interpret the fetal heart rate tracing, it also may be because a substantial number of CP cases are due to genetic and other causes, and that very few in fact result from preventable intrapartum injury.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that knowledge gaps preclude definitive determination that a given case of neonatal encephalopathy is attributable to an acute intrapartum event, and they provide criteria that must be fulfilled to establish a reasonable causal link between an intrapartum event and subsequent long-term neurologic disability.9 However, there continues to be a belief in the medical, scientific, and lay communities that birth asphyxia, secondary to adverse intrapartum events, is the leading cause of CP. A “brain-damaged infant” remains one of the most common malpractice claims, and birth injury one of the highest paid claims. Such claims generally allege that intrapartum asphyxia has caused long-term neurologic sequelae, including CP.

While it is true that prematurity, infection, hypoxia-ischemia, and pre- and perinatal stroke all have been implicated as contributing to CP risk, large population-based studies have shown that birth asphyxia accounts for less than 12% of CP cases.10 Specifically, recent data indicate that acute intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia occurs only in about 6% of CP cases. In other words, it does occur and may contribute to some cases, but this is likely a smaller percent than previously thought, and genetic factors now appear to be far more significant contributors.11

Continue to: Exploring a genetic etiology...

Exploring a genetic etiology

In considering the etiologies of CP, it is important to note that 21% to 40% of individuals with CP have an associated congenital anomaly, suggesting a genetic origin in at least some individuals. Moreover, a 40% heritability has been estimated in CP, which is comparable to the heritability rate for autism spectrum disorders.12

In the recent study by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues, some of the gene variants detected were previously associated with other forms of neurodevelopmental disability, such as epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder.3 Many individuals in the study cohort were found to have multiple neurologic comorbidities, for example, CP as well as epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and/or intellectual disability. The presence of these additional comorbidities increased the likelihood of finding a genetic cause; the authors found that the diagnostic yield ranged from 11.2% with isolated CP to 32.9% with all 3 comorbidities. The yield was highest with CP and intellectual disability and CP with all 3 comorbidities. A few genes were particularly common, and some were reported previously in association with CP and/or other neurodevelopmental disorders. In some patients, variants were found in genes or gene regions associated with disorders that do not frequently include CP, such as Rett syndrome.3

Implications for ObGyns

The data from the study by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues are interesting and relevant to pediatricians, neurologists, and geneticists, as well as obstetricians. Understanding the cause of any disease or disorder improves care, including counseling regarding the cause, the appropriate interventions or therapy, and in some families, the recurrence risk in another pregnancy. The treatment for CP has not changed significantly in many years. Increasingly, detection of an underlying genetic cause can guide precision treatments; thus, the detection of specific gene variants allows a targeted approach to therapy.

Identification of a genetic cause also can significantly impact recurrence risk counseling and prenatal diagnosis options in another pregnancy. In general, the empiric recurrence risk of CP is quoted as 1% to 2%,13 and with de novo variants this does not change. However, with inherited variants the recurrence risk in future children is substantially higher. While 72% of the genetic variants associated with CP in the Moreno-De-Luca study were de novo with a low recurrence risk, in the other 28% the mode of inheritance indicated a substantial risk of recurrence (25%–50%) in another pregnancy.3 Detecting such causative variant(s) allows not only accurate counseling about recurrence risk but also preimplantation genetic testing or prenatal diagnosis when recurrence risk is high.

In the field of obstetrics, the debate about the etiology of CP is important largely due to the medicolegal implications. Patient-oriented information on the internet often states that CP is caused by damage to the child’s brain just before, during, or soon after birth, supporting potential blame of those providing care during those times. Patient-oriented websites regarding CP do not list genetic disorders among the causes but rather include primarily environmental factors, such as prematurity, low birth weight, in utero infections, anoxia or other brain injury, or perinatal stroke. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website lists brain damage as the primary etiology of CP.14 Hopefully, these new data will increase a broader understanding of this condition.

Exome sequencing is now recommended as a first-tier test for individuals with many neurodevelopmental disorders, including epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder.15 However, comprehensive genetic testing is not typically recommended or performed in cases of CP. Based on recent data, including the report by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues, it would seem that CP should be added to the list of disorders for which exome sequencing is ordered, given the similar prevalence and diagnostic yield. ●

- Oskoui M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, et al. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:509-519.

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007;109:8-14.

- Moreno-De-Luca A, Millan F, Pesacreta DR, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325:467-475.

- Jin SC, Lewis SA, Bakhtiari S, et al. Mutations disrupting neuritogenesis genes confer risk for cerebral palsy. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1046-1056.

- Segel R, Ben-Pazi H, Zeligson S, et al. Copy number variations in cryptogenic cerebral palsy. Neurology. 2015;84:1660-1668.

- McMichael G, Girirrajan S, Moreno-De-Luca A, et al. Rare copy number variation in cerebral palsy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:40-45.

- Little WJ. On the influence of abnormal parturition, difficult labours, premature births, and asphyxia neonatorum, on the mental and physical condition of the child, especially in relation to deformities. Trans Obstet Soc Lond. 1862;3:293-344.

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5;CD006066.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Executive summary: neonatal encephalopathy and neurologic outcome second edition. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:896- 901.

- Ellenberg JH, Nelson KB. The association of cerebral palsy with birth asphyxia: a definitional quagmire. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:210- 216.

- Himmelmann K, Uvebrant P. The panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden part XII shows that patterns changed in the birth years 2007–2010. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107: 462-468.

- Petterson B, Stanley F, Henderson D. Cerebral palsy in multiple births in Western Australia: genetic aspects. Am J Med Genet. 1990;37:346- 351.

- Korzeniewski SJ, Slaughter J, Lenski M, et al. The complex aetiology of cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:528-543.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Causes and risk factors of cerebral palsy. https:// www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/causes.html. Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Srivastava S, Love-Nichols JA, Dies KA, et al; NDD Exome Scoping Review Work Group. Meta-analysis and multidisciplinary consensus statement: exome sequencing is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med. 2019;21:2413-2421.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of severe neurodisability in children, and it occurs in about 2 to 3 per 1,000 births worldwide.1 This nonprogressive disorder is characterized by symptoms that include spasticity, dystonia, choreoathetosis, and/or ataxia that are evident in the first few years of life. While many perinatal variables have been associated with CP, in most cases a specific cause is not identified.

Other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder, are often associated with CP.2 These other neurodevelopmental disorders are often genetic, and this has raised the question as to whether CP also might have a substantial genetic component, although this has not been investigated in any significant way until recently. This topic is of great interest to the obstetric community, given that CP often is attributed to obstetric events, including mismanagement of labor and delivery.

Emerging evidence of a genetic-CP association

In an article published recently in JAMA, Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues sought to determine the diagnostic yield of exome sequencing for CP.3 This large cross-sectional study included results of exome sequencing performed in 2 settings. The first setting was a commercial laboratory in which samples were sent for analysis due to a diagnosis of CP, primarily in children (n = 1,345) with a median age of 8.8 years. A second cohort, recruited from a neurodevelopmental disorders clinic at Geisinger, included primarily adults (n = 181) with a median age of 41.9 years.

As is standard in exome sequencing, results were considered likely causative if they were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic based on criteria of the American College of Genetics and Genomics. In the laboratory group, 32.7% (440 of 1,345) had a genetic cause of the CP identified, while in the clinic group, 10.5% (19 of 181) had a genetic etiology found. Although most of the identified genetic variants were de novo (that is, they arose in the affected individual and were not clearly inherited), some were inherited from carrier parents.3

A number of other recent studies also have investigated genetic causes of CP and similarly have reported that a substantial number of cases are genetic. Several studies that performed chromosomal microarray analysis in individuals with CP found deleterious copy number variants in 10% to 31% of cases.4-6 Genomic variants detectable by exome sequencing have been reported in 15% to 20% of cases.3 In a recent study in Nature Genetics, researchers performed exome sequencing on 250 parent-child “trios” in which the child had CP, and they found that 14% of cases had an associated genetic variant that was thought to be causative.4 These studies all provide consistent evidence that a substantial proportion of CP cases are due to genetic causes.

Contributors to CP risk

Historically, CP was considered to occur largely as a result of perinatal anoxia. In 1862, the British orthopedic surgeon William John Little first reported an association between prematurity, asphyxia, difficult delivery, and CP in a paper presented to the Obstetrical Society of London.7 Subsequently, much effort has gone into the prevention of perinatal asphyxia and birth injury, although our ability to monitor fetal well-being remains limited. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are nonspecific and can occur for many reasons other than fetal asphyxia. Studies of electronic fetal monitoring have found that continuous monitoring primarily leads to an increase in cesarean delivery with no decrease in CP or infant mortality.8

While some have attributed this to failure to accurately interpret the fetal heart rate tracing, it also may be because a substantial number of CP cases are due to genetic and other causes, and that very few in fact result from preventable intrapartum injury.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that knowledge gaps preclude definitive determination that a given case of neonatal encephalopathy is attributable to an acute intrapartum event, and they provide criteria that must be fulfilled to establish a reasonable causal link between an intrapartum event and subsequent long-term neurologic disability.9 However, there continues to be a belief in the medical, scientific, and lay communities that birth asphyxia, secondary to adverse intrapartum events, is the leading cause of CP. A “brain-damaged infant” remains one of the most common malpractice claims, and birth injury one of the highest paid claims. Such claims generally allege that intrapartum asphyxia has caused long-term neurologic sequelae, including CP.

While it is true that prematurity, infection, hypoxia-ischemia, and pre- and perinatal stroke all have been implicated as contributing to CP risk, large population-based studies have shown that birth asphyxia accounts for less than 12% of CP cases.10 Specifically, recent data indicate that acute intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia occurs only in about 6% of CP cases. In other words, it does occur and may contribute to some cases, but this is likely a smaller percent than previously thought, and genetic factors now appear to be far more significant contributors.11

Continue to: Exploring a genetic etiology...

Exploring a genetic etiology

In considering the etiologies of CP, it is important to note that 21% to 40% of individuals with CP have an associated congenital anomaly, suggesting a genetic origin in at least some individuals. Moreover, a 40% heritability has been estimated in CP, which is comparable to the heritability rate for autism spectrum disorders.12

In the recent study by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues, some of the gene variants detected were previously associated with other forms of neurodevelopmental disability, such as epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder.3 Many individuals in the study cohort were found to have multiple neurologic comorbidities, for example, CP as well as epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and/or intellectual disability. The presence of these additional comorbidities increased the likelihood of finding a genetic cause; the authors found that the diagnostic yield ranged from 11.2% with isolated CP to 32.9% with all 3 comorbidities. The yield was highest with CP and intellectual disability and CP with all 3 comorbidities. A few genes were particularly common, and some were reported previously in association with CP and/or other neurodevelopmental disorders. In some patients, variants were found in genes or gene regions associated with disorders that do not frequently include CP, such as Rett syndrome.3

Implications for ObGyns

The data from the study by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues are interesting and relevant to pediatricians, neurologists, and geneticists, as well as obstetricians. Understanding the cause of any disease or disorder improves care, including counseling regarding the cause, the appropriate interventions or therapy, and in some families, the recurrence risk in another pregnancy. The treatment for CP has not changed significantly in many years. Increasingly, detection of an underlying genetic cause can guide precision treatments; thus, the detection of specific gene variants allows a targeted approach to therapy.

Identification of a genetic cause also can significantly impact recurrence risk counseling and prenatal diagnosis options in another pregnancy. In general, the empiric recurrence risk of CP is quoted as 1% to 2%,13 and with de novo variants this does not change. However, with inherited variants the recurrence risk in future children is substantially higher. While 72% of the genetic variants associated with CP in the Moreno-De-Luca study were de novo with a low recurrence risk, in the other 28% the mode of inheritance indicated a substantial risk of recurrence (25%–50%) in another pregnancy.3 Detecting such causative variant(s) allows not only accurate counseling about recurrence risk but also preimplantation genetic testing or prenatal diagnosis when recurrence risk is high.

In the field of obstetrics, the debate about the etiology of CP is important largely due to the medicolegal implications. Patient-oriented information on the internet often states that CP is caused by damage to the child’s brain just before, during, or soon after birth, supporting potential blame of those providing care during those times. Patient-oriented websites regarding CP do not list genetic disorders among the causes but rather include primarily environmental factors, such as prematurity, low birth weight, in utero infections, anoxia or other brain injury, or perinatal stroke. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website lists brain damage as the primary etiology of CP.14 Hopefully, these new data will increase a broader understanding of this condition.

Exome sequencing is now recommended as a first-tier test for individuals with many neurodevelopmental disorders, including epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder.15 However, comprehensive genetic testing is not typically recommended or performed in cases of CP. Based on recent data, including the report by Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues, it would seem that CP should be added to the list of disorders for which exome sequencing is ordered, given the similar prevalence and diagnostic yield. ●

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of severe neurodisability in children, and it occurs in about 2 to 3 per 1,000 births worldwide.1 This nonprogressive disorder is characterized by symptoms that include spasticity, dystonia, choreoathetosis, and/or ataxia that are evident in the first few years of life. While many perinatal variables have been associated with CP, in most cases a specific cause is not identified.

Other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder, are often associated with CP.2 These other neurodevelopmental disorders are often genetic, and this has raised the question as to whether CP also might have a substantial genetic component, although this has not been investigated in any significant way until recently. This topic is of great interest to the obstetric community, given that CP often is attributed to obstetric events, including mismanagement of labor and delivery.

Emerging evidence of a genetic-CP association

In an article published recently in JAMA, Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues sought to determine the diagnostic yield of exome sequencing for CP.3 This large cross-sectional study included results of exome sequencing performed in 2 settings. The first setting was a commercial laboratory in which samples were sent for analysis due to a diagnosis of CP, primarily in children (n = 1,345) with a median age of 8.8 years. A second cohort, recruited from a neurodevelopmental disorders clinic at Geisinger, included primarily adults (n = 181) with a median age of 41.9 years.

As is standard in exome sequencing, results were considered likely causative if they were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic based on criteria of the American College of Genetics and Genomics. In the laboratory group, 32.7% (440 of 1,345) had a genetic cause of the CP identified, while in the clinic group, 10.5% (19 of 181) had a genetic etiology found. Although most of the identified genetic variants were de novo (that is, they arose in the affected individual and were not clearly inherited), some were inherited from carrier parents.3

A number of other recent studies also have investigated genetic causes of CP and similarly have reported that a substantial number of cases are genetic. Several studies that performed chromosomal microarray analysis in individuals with CP found deleterious copy number variants in 10% to 31% of cases.4-6 Genomic variants detectable by exome sequencing have been reported in 15% to 20% of cases.3 In a recent study in Nature Genetics, researchers performed exome sequencing on 250 parent-child “trios” in which the child had CP, and they found that 14% of cases had an associated genetic variant that was thought to be causative.4 These studies all provide consistent evidence that a substantial proportion of CP cases are due to genetic causes.

Contributors to CP risk

Historically, CP was considered to occur largely as a result of perinatal anoxia. In 1862, the British orthopedic surgeon William John Little first reported an association between prematurity, asphyxia, difficult delivery, and CP in a paper presented to the Obstetrical Society of London.7 Subsequently, much effort has gone into the prevention of perinatal asphyxia and birth injury, although our ability to monitor fetal well-being remains limited. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are nonspecific and can occur for many reasons other than fetal asphyxia. Studies of electronic fetal monitoring have found that continuous monitoring primarily leads to an increase in cesarean delivery with no decrease in CP or infant mortality.8

While some have attributed this to failure to accurately interpret the fetal heart rate tracing, it also may be because a substantial number of CP cases are due to genetic and other causes, and that very few in fact result from preventable intrapartum injury.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that knowledge gaps preclude definitive determination that a given case of neonatal encephalopathy is attributable to an acute intrapartum event, and they provide criteria that must be fulfilled to establish a reasonable causal link between an intrapartum event and subsequent long-term neurologic disability.9 However, there continues to be a belief in the medical, scientific, and lay communities that birth asphyxia, secondary to adverse intrapartum events, is the leading cause of CP. A “brain-damaged infant” remains one of the most common malpractice claims, and birth injury one of the highest paid claims. Such claims generally allege that intrapartum asphyxia has caused long-term neurologic sequelae, including CP.

While it is true that prematurity, infection, hypoxia-ischemia, and pre- and perinatal stroke all have been implicated as contributing to CP risk, large population-based studies have shown that birth asphyxia accounts for less than 12% of CP cases.10 Specifically, recent data indicate that acute intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia occurs only in about 6% of CP cases. In other words, it does occur and may contribute to some cases, but this is likely a smaller percent than previously thought, and genetic factors now appear to be far more significant contributors.11

Continue to: Exploring a genetic etiology...

Exploring a genetic etiology

In considering the etiologies of CP, it is important to note that 21% to 40% of individuals with CP have an associated congenital anomaly, suggesting a genetic origin in at least some individuals. Moreover, a 40% heritability has been estimated in CP, which is comparable to the heritability rate for autism spectrum disorders.12