User login

Bariatric surgery leads to better cardiovascular function in pregnancy

Pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery have better cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy compared with women who have similar early-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) but no history of weight loss surgery, new data suggest.

“Pregnant women who have had bariatric surgery demonstrate better cardiovascular adaptation through lower blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, more favorable diastolic indices, and better systolic function,” reported Deesha Patel, MBBS MRCOG, specialist registrar, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“Because the groups were matched for early pregnancy BMI, it’s unlikely that the results are due to weight loss alone but indicate that the metabolic alterations as a result of the surgery, via the enterocardiac axis, play an important role,” Dr. Patel continued.

The findings were presented at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2021 Virtual World Congress.

Although obesity is known for its inflammatory and toxic effects on the cardiovascular system, it is not clear to what extent the various treatment options for obesity modify these risks in the long term, said Hutan Ashrafian, MD, clinical lecturer in surgery, Imperial College London.

“It is even less clear how anti-obesity interventions affect the cardiovascular system in pregnancy,” Dr. Ashrafian told this news organization.

“This very novel study in pregnant mothers having undergone the most successful and consistent intervention for severe obesity – bariatric or metabolic surgery – gives new clues as to the extent that bariatric procedures can alter cardiovascular risk in pregnant mothers,” continued Dr. Ashrafian, who was not involved in the study.

The results show how bariatric surgery has favorable effects on cardiac adaptation in pregnancy and in turn “might offer protection from pregnancy-related cardiovascular pathology such as preeclampsia,” explained Dr. Ashrafian. “This adds to the known effects of cardiovascular protection of bariatric surgery through the enterocardiac axis, which may explain a wider range of effects that can be translated within pregnancy and possibly following pregnancy in the postpartum era and beyond.”

A history of bariatric surgery versus no surgery

The prospective, longitudinal study compared 41 women who had a history of bariatric surgery with 41 women who had not undergone surgery. Patients’ characteristics were closely matched for age, BMI (34.5 kg/m2 and 34.3 kg/m2 in the surgery and bariatric surgery groups, respectively) and race. Hypertensive disorders in the post-surgery group were significantly less common compared with the no-surgery group (0% vs. 9.8%).

During the study, participants underwent cardiovascular assessment at 12-14 weeks, 20-24 weeks, and 30-32 weeks of gestation. The assessment included measurement of blood pressure and heart rate, transthoracic echocardiography, and 2D speckle tracking, performed offline to assess global longitudinal and circumferential strain.

Blood pressure readings across the three trimesters were consistently lower in the women who had undergone bariatric surgery compared with those in the no-surgery group, and all differences were statistically significant. Likewise, heart rate and cardiac output across the three trimesters were lower in the post-surgery cohort. However, there was no difference in stroke volume between the two groups.

As for diastolic function, there were more favorable indices in the post-surgery group with a higher E/A ratio, a marker of left ventricle filling (P < .001), and lower left atrial volume (P < .05), Dr. Patel reported.

With respect to systolic function, there was no difference in ejection fraction, but there was lower global longitudinal strain (P < .01) and global circumferential strain in the post-bariatric group (P = .02), suggesting better systolic function.

“Strain is a measure of differences in motion and velocity between regions of the myocardium through the cardiac cycle and can detect subclinical changes when ejection fraction is normal,” she added.

“This is a fascinating piece of work. The author should be congratulated on gathering so many [pregnant] women who had had bariatric surgery. The work gives a unique glimpse into metabolic syndrome,” said Philip Toozs-Hobson, MD, who moderated the session.

“We are increasingly recognizing the impact [of bariatric surgery] on metabolic syndrome, and the fact that this study demonstrates that there is more to it than just weight is important,” continued Dr. Toosz-Hobson, who is a consultant gynecologist at Birmingham Women’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom.

Cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery has been associated with loss of excess body weight of up to 55% and with approximately 40% reduction in all-cause mortality in the general population. The procedure also reduces the risk for heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

The cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery include reduced hypertension, remodeling of the heart with a reduction in left ventricular mass, and an improvement in diastolic and systolic function.

“Traditionally, the cardiac changes were thought to be due to weight loss and blood pressure reduction, but it is now conceivable that the metabolic components contribute to the reverse modeling via changes to the enterocardiac axis involving changes to gut hormones,” said Dr. Patel. These hormones include secretin, glucagon, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which are known to have inotropic effects, as well as adiponectin and leptin, which are known to have cardiac effects, she added.

“Pregnancy following bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced risk of hypertensive disorders, as well as a reduced risk of gestational diabetes, large-for-gestational-age neonates, and a small increased risk of small-for-gestational-age neonates,” said Dr. Patel.

Dr. Patel and Dr. Toosz-Hobson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery have better cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy compared with women who have similar early-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) but no history of weight loss surgery, new data suggest.

“Pregnant women who have had bariatric surgery demonstrate better cardiovascular adaptation through lower blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, more favorable diastolic indices, and better systolic function,” reported Deesha Patel, MBBS MRCOG, specialist registrar, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“Because the groups were matched for early pregnancy BMI, it’s unlikely that the results are due to weight loss alone but indicate that the metabolic alterations as a result of the surgery, via the enterocardiac axis, play an important role,” Dr. Patel continued.

The findings were presented at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2021 Virtual World Congress.

Although obesity is known for its inflammatory and toxic effects on the cardiovascular system, it is not clear to what extent the various treatment options for obesity modify these risks in the long term, said Hutan Ashrafian, MD, clinical lecturer in surgery, Imperial College London.

“It is even less clear how anti-obesity interventions affect the cardiovascular system in pregnancy,” Dr. Ashrafian told this news organization.

“This very novel study in pregnant mothers having undergone the most successful and consistent intervention for severe obesity – bariatric or metabolic surgery – gives new clues as to the extent that bariatric procedures can alter cardiovascular risk in pregnant mothers,” continued Dr. Ashrafian, who was not involved in the study.

The results show how bariatric surgery has favorable effects on cardiac adaptation in pregnancy and in turn “might offer protection from pregnancy-related cardiovascular pathology such as preeclampsia,” explained Dr. Ashrafian. “This adds to the known effects of cardiovascular protection of bariatric surgery through the enterocardiac axis, which may explain a wider range of effects that can be translated within pregnancy and possibly following pregnancy in the postpartum era and beyond.”

A history of bariatric surgery versus no surgery

The prospective, longitudinal study compared 41 women who had a history of bariatric surgery with 41 women who had not undergone surgery. Patients’ characteristics were closely matched for age, BMI (34.5 kg/m2 and 34.3 kg/m2 in the surgery and bariatric surgery groups, respectively) and race. Hypertensive disorders in the post-surgery group were significantly less common compared with the no-surgery group (0% vs. 9.8%).

During the study, participants underwent cardiovascular assessment at 12-14 weeks, 20-24 weeks, and 30-32 weeks of gestation. The assessment included measurement of blood pressure and heart rate, transthoracic echocardiography, and 2D speckle tracking, performed offline to assess global longitudinal and circumferential strain.

Blood pressure readings across the three trimesters were consistently lower in the women who had undergone bariatric surgery compared with those in the no-surgery group, and all differences were statistically significant. Likewise, heart rate and cardiac output across the three trimesters were lower in the post-surgery cohort. However, there was no difference in stroke volume between the two groups.

As for diastolic function, there were more favorable indices in the post-surgery group with a higher E/A ratio, a marker of left ventricle filling (P < .001), and lower left atrial volume (P < .05), Dr. Patel reported.

With respect to systolic function, there was no difference in ejection fraction, but there was lower global longitudinal strain (P < .01) and global circumferential strain in the post-bariatric group (P = .02), suggesting better systolic function.

“Strain is a measure of differences in motion and velocity between regions of the myocardium through the cardiac cycle and can detect subclinical changes when ejection fraction is normal,” she added.

“This is a fascinating piece of work. The author should be congratulated on gathering so many [pregnant] women who had had bariatric surgery. The work gives a unique glimpse into metabolic syndrome,” said Philip Toozs-Hobson, MD, who moderated the session.

“We are increasingly recognizing the impact [of bariatric surgery] on metabolic syndrome, and the fact that this study demonstrates that there is more to it than just weight is important,” continued Dr. Toosz-Hobson, who is a consultant gynecologist at Birmingham Women’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom.

Cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery has been associated with loss of excess body weight of up to 55% and with approximately 40% reduction in all-cause mortality in the general population. The procedure also reduces the risk for heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

The cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery include reduced hypertension, remodeling of the heart with a reduction in left ventricular mass, and an improvement in diastolic and systolic function.

“Traditionally, the cardiac changes were thought to be due to weight loss and blood pressure reduction, but it is now conceivable that the metabolic components contribute to the reverse modeling via changes to the enterocardiac axis involving changes to gut hormones,” said Dr. Patel. These hormones include secretin, glucagon, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which are known to have inotropic effects, as well as adiponectin and leptin, which are known to have cardiac effects, she added.

“Pregnancy following bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced risk of hypertensive disorders, as well as a reduced risk of gestational diabetes, large-for-gestational-age neonates, and a small increased risk of small-for-gestational-age neonates,” said Dr. Patel.

Dr. Patel and Dr. Toosz-Hobson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery have better cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy compared with women who have similar early-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) but no history of weight loss surgery, new data suggest.

“Pregnant women who have had bariatric surgery demonstrate better cardiovascular adaptation through lower blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, more favorable diastolic indices, and better systolic function,” reported Deesha Patel, MBBS MRCOG, specialist registrar, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“Because the groups were matched for early pregnancy BMI, it’s unlikely that the results are due to weight loss alone but indicate that the metabolic alterations as a result of the surgery, via the enterocardiac axis, play an important role,” Dr. Patel continued.

The findings were presented at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2021 Virtual World Congress.

Although obesity is known for its inflammatory and toxic effects on the cardiovascular system, it is not clear to what extent the various treatment options for obesity modify these risks in the long term, said Hutan Ashrafian, MD, clinical lecturer in surgery, Imperial College London.

“It is even less clear how anti-obesity interventions affect the cardiovascular system in pregnancy,” Dr. Ashrafian told this news organization.

“This very novel study in pregnant mothers having undergone the most successful and consistent intervention for severe obesity – bariatric or metabolic surgery – gives new clues as to the extent that bariatric procedures can alter cardiovascular risk in pregnant mothers,” continued Dr. Ashrafian, who was not involved in the study.

The results show how bariatric surgery has favorable effects on cardiac adaptation in pregnancy and in turn “might offer protection from pregnancy-related cardiovascular pathology such as preeclampsia,” explained Dr. Ashrafian. “This adds to the known effects of cardiovascular protection of bariatric surgery through the enterocardiac axis, which may explain a wider range of effects that can be translated within pregnancy and possibly following pregnancy in the postpartum era and beyond.”

A history of bariatric surgery versus no surgery

The prospective, longitudinal study compared 41 women who had a history of bariatric surgery with 41 women who had not undergone surgery. Patients’ characteristics were closely matched for age, BMI (34.5 kg/m2 and 34.3 kg/m2 in the surgery and bariatric surgery groups, respectively) and race. Hypertensive disorders in the post-surgery group were significantly less common compared with the no-surgery group (0% vs. 9.8%).

During the study, participants underwent cardiovascular assessment at 12-14 weeks, 20-24 weeks, and 30-32 weeks of gestation. The assessment included measurement of blood pressure and heart rate, transthoracic echocardiography, and 2D speckle tracking, performed offline to assess global longitudinal and circumferential strain.

Blood pressure readings across the three trimesters were consistently lower in the women who had undergone bariatric surgery compared with those in the no-surgery group, and all differences were statistically significant. Likewise, heart rate and cardiac output across the three trimesters were lower in the post-surgery cohort. However, there was no difference in stroke volume between the two groups.

As for diastolic function, there were more favorable indices in the post-surgery group with a higher E/A ratio, a marker of left ventricle filling (P < .001), and lower left atrial volume (P < .05), Dr. Patel reported.

With respect to systolic function, there was no difference in ejection fraction, but there was lower global longitudinal strain (P < .01) and global circumferential strain in the post-bariatric group (P = .02), suggesting better systolic function.

“Strain is a measure of differences in motion and velocity between regions of the myocardium through the cardiac cycle and can detect subclinical changes when ejection fraction is normal,” she added.

“This is a fascinating piece of work. The author should be congratulated on gathering so many [pregnant] women who had had bariatric surgery. The work gives a unique glimpse into metabolic syndrome,” said Philip Toozs-Hobson, MD, who moderated the session.

“We are increasingly recognizing the impact [of bariatric surgery] on metabolic syndrome, and the fact that this study demonstrates that there is more to it than just weight is important,” continued Dr. Toosz-Hobson, who is a consultant gynecologist at Birmingham Women’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom.

Cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery has been associated with loss of excess body weight of up to 55% and with approximately 40% reduction in all-cause mortality in the general population. The procedure also reduces the risk for heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

The cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery include reduced hypertension, remodeling of the heart with a reduction in left ventricular mass, and an improvement in diastolic and systolic function.

“Traditionally, the cardiac changes were thought to be due to weight loss and blood pressure reduction, but it is now conceivable that the metabolic components contribute to the reverse modeling via changes to the enterocardiac axis involving changes to gut hormones,” said Dr. Patel. These hormones include secretin, glucagon, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which are known to have inotropic effects, as well as adiponectin and leptin, which are known to have cardiac effects, she added.

“Pregnancy following bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced risk of hypertensive disorders, as well as a reduced risk of gestational diabetes, large-for-gestational-age neonates, and a small increased risk of small-for-gestational-age neonates,” said Dr. Patel.

Dr. Patel and Dr. Toosz-Hobson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with migraine are ‘high-risk’ patients during pregnancy

new research suggests. Although pregnancy is generally considered a “safe period” for women with migraine, “we actually found they have more diabetes, more hypertension, more blood clots, more complications during their delivery, and more postpartum complications,” said study investigator Nirit Lev, MD, PhD, head, department of neurology, Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University.

The results highlight the need for clinicians “to take people with migraines seriously” and reinforce the idea that migraine is not “just a headache,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine should be considered high risk and have specialized neurologic follow-up during pregnancy and the postpartum period, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Prevalent, disabling

Migraine is one of the most prevalent and disabling neurologic disorders. Such disorders are major causes of death and disability.

In childhood, there’s no difference between the sexes in terms of migraine prevalence, but after puberty, migraine is about three times more common in women than men. Fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone likely explain these differences, said Dr. Lev.

The prevalence of migraine among females peaks during their reproductive years. Most female migraine patients report an improvement in headache symptoms during pregnancy, with some experiencing a “complete remission.” However, a minority report worsening of migraine when expecting a child, said Dr. Lev.

Some patients have their first aura during pregnancy. The most common migraine aura is visual, a problem with the visual field that can affect motor and sensory functioning, said Dr. Lev.

Managing migraine during pregnancy is “very complicated,” said Dr. Lev. She said the first-line treatment is paracetamol (acetaminophen) and stressed that taking opioids should be avoided.

Retrospective database study

For the study, the researchers retrospectively reviewed pregnancy and delivery records from a database of Clalit Medical Services, which has more than 4.5 million members and is the largest such database in Israel. They collected demographic data and information on mode of delivery, medical and obstetric complications, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, use of medications, laboratory reports, and medical consultations.

The study included 145,102 women who gave birth from 2014 to 2020.

Of these, 10,646 had migraine without aura, and 1,576 had migraine with aura. The migraine diagnoses, which were based on International Headache Society criteria and diagnostic codes, were made prior to pregnancy.

Dr. Lev noted that the number of patients with migraine is likely an underestimation because migraine is “not always diagnosed.”

Results showed that the risk for obstetric complications was higher among pregnant women with migraine, especially those with aura, in comparison with women without migraine. About 6.9% of patients with migraine without aura were admitted to high-risk hospital departments, compared with 6% of pregnant control patients who did not have migraine (P < .0001). For patients with migraine with aura, the risk for admissions was even higher (8.7%; P < .0001 vs. control patients and P < .03 vs. patients with migraine without aura) and was “very highly statistically significant,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine were at significantly increased risk for gestational diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (all P < .0001). These women were also more likely to experience preeclampsia and blood clots (P < .0001).

Unexpected finding

The finding that the risk for diabetes was higher was “unexpected,” inasmuch as older women with migraine are typically at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and higher body mass index, said Dr. Lev.

Migraine patients had significantly more consultations with family physicians, gynecologists, and neurologists (P < .0001). In addition, they were more likely to utilize emergency services; take more medications, mostly analgesics; and undergo more laboratory studies and brain imaging.

Those with aura had significantly more specialist consultations and took more medications compared with migraine patients without aura.

There was a statistically significant increase in the use of epidural anesthesia for migraine patients (40.5% of women without migraine; 45.7% of those with migraine accompanied by aura; and 47.5% of migraine patients without aura).

This was an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Lev. “We didn’t know what to expect; people with migraine are used to pain, so the question was, will they tolerate pain better or be more afraid of pain?”

Women with migraine also experienced more assisted deliveries with increased use of vacuums and forceps.

During the 3-month postpartum period, women with migraine sought more medical consultations and used more medications compared with control patients. They also underwent more lab examinations and more brain imaging during this period.

Dr. Lev noted that some of these evaluations may have been postponed because of the pregnancy.

Women with migraine also had a greater risk for postpartum depression, which Dr. Lev found “concerning.” She noted that depression is often underreported but is treatable. Women with migraine should be monitored for depression post partum, she said.

It’s unclear which factors contribute to the increased risk for pregnancy complications in women with migraine. Dr. Lev said she doesn’t believe it’s drug related.

“Although they’re taking more medications than people who don’t have migraine, we still are giving very low doses and only safe medicines, so I don’t think these increased risks are side effects,” she said.

She noted that women with migraine have more cardiovascular complications, including stroke and myocardial infarction, although these generally affect older patients.

Dr. Lev also noted that pain, especially chronic pain, can cause depression. “We know that people with migraine have more depression and anxiety, so maybe that also affects them during their pregnancy and after,” she said.

She suggested that pregnant women with migraine be considered high risk and be managed via specialized clinics.

Room for improvement

Commenting on the research, Lauren Doyle Strauss, DO, associate professor of neurology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who has written about the management of migraine during pregnancy, said studies such as this help raise awareness about pregnancy risks in migraine patients. Dr. Strauss did not attend the live presentation but is aware of the findings.

The increased use of epidurals during delivery among migraine patients in the study makes some sense, said Dr. Strauss. “It kind of shows a comfort level with medicines.”

She expressed concern that such research may be “skewed” because it includes patients with more severe migraine. If less severe cases were included in this research, “maybe there would still be higher risks, but not as high as what we have been finding in some of our studies,” she said.

Dr. Strauss said she feels the medical community should do a better job of identifying and diagnosing migraine. She said she would like to see migraine screening become a routine part of obstetric/gynecologic care. Doctors should counsel migraine patients who wish to become pregnant about potential risks, said Dr. Strauss. “We need to be up front in telling them when to seek care and when to report symptoms and not to wait for it to become super severe,” she said.

She also believes doctors should be “proactive” in helping patients develop a treatment plan before becoming pregnant, because the limited pain control options available for pregnant patients can take time to have an effect.

Also commenting on the study findings, Nina Riggins, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study raises “important questions” and has “important aims.”

She believes the study reinforces the importance of collaboration between experts in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, and neurology. However, she was surprised at some of the investigators’ assertions that there are no differences in migraine among prepubertal children and that the course of migraine for men is stable throughout their life span.

“There is literature that supports the view that the prevalence in boys is higher in prepuberty, and studies do show that migraine prevalence decreases in older adults – men and women,” she said.

There is still not enough evidence to determine that antiemetics and triptans are safe during pregnancy or that pregnant women with migraine should be taking acetylsalicylic acid, said Dr. Riggins.

The investigators, Dr. Strauss, and Dr. Riggins have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Although pregnancy is generally considered a “safe period” for women with migraine, “we actually found they have more diabetes, more hypertension, more blood clots, more complications during their delivery, and more postpartum complications,” said study investigator Nirit Lev, MD, PhD, head, department of neurology, Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University.

The results highlight the need for clinicians “to take people with migraines seriously” and reinforce the idea that migraine is not “just a headache,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine should be considered high risk and have specialized neurologic follow-up during pregnancy and the postpartum period, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Prevalent, disabling

Migraine is one of the most prevalent and disabling neurologic disorders. Such disorders are major causes of death and disability.

In childhood, there’s no difference between the sexes in terms of migraine prevalence, but after puberty, migraine is about three times more common in women than men. Fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone likely explain these differences, said Dr. Lev.

The prevalence of migraine among females peaks during their reproductive years. Most female migraine patients report an improvement in headache symptoms during pregnancy, with some experiencing a “complete remission.” However, a minority report worsening of migraine when expecting a child, said Dr. Lev.

Some patients have their first aura during pregnancy. The most common migraine aura is visual, a problem with the visual field that can affect motor and sensory functioning, said Dr. Lev.

Managing migraine during pregnancy is “very complicated,” said Dr. Lev. She said the first-line treatment is paracetamol (acetaminophen) and stressed that taking opioids should be avoided.

Retrospective database study

For the study, the researchers retrospectively reviewed pregnancy and delivery records from a database of Clalit Medical Services, which has more than 4.5 million members and is the largest such database in Israel. They collected demographic data and information on mode of delivery, medical and obstetric complications, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, use of medications, laboratory reports, and medical consultations.

The study included 145,102 women who gave birth from 2014 to 2020.

Of these, 10,646 had migraine without aura, and 1,576 had migraine with aura. The migraine diagnoses, which were based on International Headache Society criteria and diagnostic codes, were made prior to pregnancy.

Dr. Lev noted that the number of patients with migraine is likely an underestimation because migraine is “not always diagnosed.”

Results showed that the risk for obstetric complications was higher among pregnant women with migraine, especially those with aura, in comparison with women without migraine. About 6.9% of patients with migraine without aura were admitted to high-risk hospital departments, compared with 6% of pregnant control patients who did not have migraine (P < .0001). For patients with migraine with aura, the risk for admissions was even higher (8.7%; P < .0001 vs. control patients and P < .03 vs. patients with migraine without aura) and was “very highly statistically significant,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine were at significantly increased risk for gestational diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (all P < .0001). These women were also more likely to experience preeclampsia and blood clots (P < .0001).

Unexpected finding

The finding that the risk for diabetes was higher was “unexpected,” inasmuch as older women with migraine are typically at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and higher body mass index, said Dr. Lev.

Migraine patients had significantly more consultations with family physicians, gynecologists, and neurologists (P < .0001). In addition, they were more likely to utilize emergency services; take more medications, mostly analgesics; and undergo more laboratory studies and brain imaging.

Those with aura had significantly more specialist consultations and took more medications compared with migraine patients without aura.

There was a statistically significant increase in the use of epidural anesthesia for migraine patients (40.5% of women without migraine; 45.7% of those with migraine accompanied by aura; and 47.5% of migraine patients without aura).

This was an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Lev. “We didn’t know what to expect; people with migraine are used to pain, so the question was, will they tolerate pain better or be more afraid of pain?”

Women with migraine also experienced more assisted deliveries with increased use of vacuums and forceps.

During the 3-month postpartum period, women with migraine sought more medical consultations and used more medications compared with control patients. They also underwent more lab examinations and more brain imaging during this period.

Dr. Lev noted that some of these evaluations may have been postponed because of the pregnancy.

Women with migraine also had a greater risk for postpartum depression, which Dr. Lev found “concerning.” She noted that depression is often underreported but is treatable. Women with migraine should be monitored for depression post partum, she said.

It’s unclear which factors contribute to the increased risk for pregnancy complications in women with migraine. Dr. Lev said she doesn’t believe it’s drug related.

“Although they’re taking more medications than people who don’t have migraine, we still are giving very low doses and only safe medicines, so I don’t think these increased risks are side effects,” she said.

She noted that women with migraine have more cardiovascular complications, including stroke and myocardial infarction, although these generally affect older patients.

Dr. Lev also noted that pain, especially chronic pain, can cause depression. “We know that people with migraine have more depression and anxiety, so maybe that also affects them during their pregnancy and after,” she said.

She suggested that pregnant women with migraine be considered high risk and be managed via specialized clinics.

Room for improvement

Commenting on the research, Lauren Doyle Strauss, DO, associate professor of neurology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who has written about the management of migraine during pregnancy, said studies such as this help raise awareness about pregnancy risks in migraine patients. Dr. Strauss did not attend the live presentation but is aware of the findings.

The increased use of epidurals during delivery among migraine patients in the study makes some sense, said Dr. Strauss. “It kind of shows a comfort level with medicines.”

She expressed concern that such research may be “skewed” because it includes patients with more severe migraine. If less severe cases were included in this research, “maybe there would still be higher risks, but not as high as what we have been finding in some of our studies,” she said.

Dr. Strauss said she feels the medical community should do a better job of identifying and diagnosing migraine. She said she would like to see migraine screening become a routine part of obstetric/gynecologic care. Doctors should counsel migraine patients who wish to become pregnant about potential risks, said Dr. Strauss. “We need to be up front in telling them when to seek care and when to report symptoms and not to wait for it to become super severe,” she said.

She also believes doctors should be “proactive” in helping patients develop a treatment plan before becoming pregnant, because the limited pain control options available for pregnant patients can take time to have an effect.

Also commenting on the study findings, Nina Riggins, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study raises “important questions” and has “important aims.”

She believes the study reinforces the importance of collaboration between experts in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, and neurology. However, she was surprised at some of the investigators’ assertions that there are no differences in migraine among prepubertal children and that the course of migraine for men is stable throughout their life span.

“There is literature that supports the view that the prevalence in boys is higher in prepuberty, and studies do show that migraine prevalence decreases in older adults – men and women,” she said.

There is still not enough evidence to determine that antiemetics and triptans are safe during pregnancy or that pregnant women with migraine should be taking acetylsalicylic acid, said Dr. Riggins.

The investigators, Dr. Strauss, and Dr. Riggins have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Although pregnancy is generally considered a “safe period” for women with migraine, “we actually found they have more diabetes, more hypertension, more blood clots, more complications during their delivery, and more postpartum complications,” said study investigator Nirit Lev, MD, PhD, head, department of neurology, Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University.

The results highlight the need for clinicians “to take people with migraines seriously” and reinforce the idea that migraine is not “just a headache,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine should be considered high risk and have specialized neurologic follow-up during pregnancy and the postpartum period, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Prevalent, disabling

Migraine is one of the most prevalent and disabling neurologic disorders. Such disorders are major causes of death and disability.

In childhood, there’s no difference between the sexes in terms of migraine prevalence, but after puberty, migraine is about three times more common in women than men. Fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone likely explain these differences, said Dr. Lev.

The prevalence of migraine among females peaks during their reproductive years. Most female migraine patients report an improvement in headache symptoms during pregnancy, with some experiencing a “complete remission.” However, a minority report worsening of migraine when expecting a child, said Dr. Lev.

Some patients have their first aura during pregnancy. The most common migraine aura is visual, a problem with the visual field that can affect motor and sensory functioning, said Dr. Lev.

Managing migraine during pregnancy is “very complicated,” said Dr. Lev. She said the first-line treatment is paracetamol (acetaminophen) and stressed that taking opioids should be avoided.

Retrospective database study

For the study, the researchers retrospectively reviewed pregnancy and delivery records from a database of Clalit Medical Services, which has more than 4.5 million members and is the largest such database in Israel. They collected demographic data and information on mode of delivery, medical and obstetric complications, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, use of medications, laboratory reports, and medical consultations.

The study included 145,102 women who gave birth from 2014 to 2020.

Of these, 10,646 had migraine without aura, and 1,576 had migraine with aura. The migraine diagnoses, which were based on International Headache Society criteria and diagnostic codes, were made prior to pregnancy.

Dr. Lev noted that the number of patients with migraine is likely an underestimation because migraine is “not always diagnosed.”

Results showed that the risk for obstetric complications was higher among pregnant women with migraine, especially those with aura, in comparison with women without migraine. About 6.9% of patients with migraine without aura were admitted to high-risk hospital departments, compared with 6% of pregnant control patients who did not have migraine (P < .0001). For patients with migraine with aura, the risk for admissions was even higher (8.7%; P < .0001 vs. control patients and P < .03 vs. patients with migraine without aura) and was “very highly statistically significant,” said Dr. Lev.

Pregnant women with migraine were at significantly increased risk for gestational diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (all P < .0001). These women were also more likely to experience preeclampsia and blood clots (P < .0001).

Unexpected finding

The finding that the risk for diabetes was higher was “unexpected,” inasmuch as older women with migraine are typically at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and higher body mass index, said Dr. Lev.

Migraine patients had significantly more consultations with family physicians, gynecologists, and neurologists (P < .0001). In addition, they were more likely to utilize emergency services; take more medications, mostly analgesics; and undergo more laboratory studies and brain imaging.

Those with aura had significantly more specialist consultations and took more medications compared with migraine patients without aura.

There was a statistically significant increase in the use of epidural anesthesia for migraine patients (40.5% of women without migraine; 45.7% of those with migraine accompanied by aura; and 47.5% of migraine patients without aura).

This was an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Lev. “We didn’t know what to expect; people with migraine are used to pain, so the question was, will they tolerate pain better or be more afraid of pain?”

Women with migraine also experienced more assisted deliveries with increased use of vacuums and forceps.

During the 3-month postpartum period, women with migraine sought more medical consultations and used more medications compared with control patients. They also underwent more lab examinations and more brain imaging during this period.

Dr. Lev noted that some of these evaluations may have been postponed because of the pregnancy.

Women with migraine also had a greater risk for postpartum depression, which Dr. Lev found “concerning.” She noted that depression is often underreported but is treatable. Women with migraine should be monitored for depression post partum, she said.

It’s unclear which factors contribute to the increased risk for pregnancy complications in women with migraine. Dr. Lev said she doesn’t believe it’s drug related.

“Although they’re taking more medications than people who don’t have migraine, we still are giving very low doses and only safe medicines, so I don’t think these increased risks are side effects,” she said.

She noted that women with migraine have more cardiovascular complications, including stroke and myocardial infarction, although these generally affect older patients.

Dr. Lev also noted that pain, especially chronic pain, can cause depression. “We know that people with migraine have more depression and anxiety, so maybe that also affects them during their pregnancy and after,” she said.

She suggested that pregnant women with migraine be considered high risk and be managed via specialized clinics.

Room for improvement

Commenting on the research, Lauren Doyle Strauss, DO, associate professor of neurology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who has written about the management of migraine during pregnancy, said studies such as this help raise awareness about pregnancy risks in migraine patients. Dr. Strauss did not attend the live presentation but is aware of the findings.

The increased use of epidurals during delivery among migraine patients in the study makes some sense, said Dr. Strauss. “It kind of shows a comfort level with medicines.”

She expressed concern that such research may be “skewed” because it includes patients with more severe migraine. If less severe cases were included in this research, “maybe there would still be higher risks, but not as high as what we have been finding in some of our studies,” she said.

Dr. Strauss said she feels the medical community should do a better job of identifying and diagnosing migraine. She said she would like to see migraine screening become a routine part of obstetric/gynecologic care. Doctors should counsel migraine patients who wish to become pregnant about potential risks, said Dr. Strauss. “We need to be up front in telling them when to seek care and when to report symptoms and not to wait for it to become super severe,” she said.

She also believes doctors should be “proactive” in helping patients develop a treatment plan before becoming pregnant, because the limited pain control options available for pregnant patients can take time to have an effect.

Also commenting on the study findings, Nina Riggins, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study raises “important questions” and has “important aims.”

She believes the study reinforces the importance of collaboration between experts in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, and neurology. However, she was surprised at some of the investigators’ assertions that there are no differences in migraine among prepubertal children and that the course of migraine for men is stable throughout their life span.

“There is literature that supports the view that the prevalence in boys is higher in prepuberty, and studies do show that migraine prevalence decreases in older adults – men and women,” she said.

There is still not enough evidence to determine that antiemetics and triptans are safe during pregnancy or that pregnant women with migraine should be taking acetylsalicylic acid, said Dr. Riggins.

The investigators, Dr. Strauss, and Dr. Riggins have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From EAN 2021

Focus on diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus affects 10% of the US population, and as many as one-third of US adults have prediabetes, according to the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While diabetes is associated with significant long-term morbidity and mortality, with early identification and interventions, lifestyle modifications can significantly improve long-term health.

As with obesity (see “Focus on obesity” in OBG Management, May 2021), it is difficult to address lifestyle modifications with patients who have diabetes. However, many apps can be leveraged to aid physicians in this effort.

Diabetes app considerations

Obstetrician-gynecologists can play a pivotal role in helping to screen women for diabetes. When applying the ACOG-recommended rubric to evaluate the quality of an app that is targeted to address screening and diagnosing diabetes, it’s important to consider the app’s timeliness, authority, usefulness, and design.

There are point-of-care apps that include a few simple questions that can quickly identify which women should be screened. Some apps combine screening questions with testing results to streamline screening and diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes. These apps also provide clinical content to help physicians educate, initiate, and even treat diabetes if they desire.

A wealth of patient-centered apps are available to help patients address a diagnosis of diabetes. Apps that provide real-time feedback, motivational features to engage the user, and links to nutritional, fitness, and diabetic goals provide a woman with a comprehensive and personalized experience that can considerably improve health.

By incorporating apps and engaging with our patients on app technology, ObGyns can successfully partner with women to decrease morbidity with respect to diabetes mellitus and its long-term implications. ●

Diabetes mellitus affects 10% of the US population, and as many as one-third of US adults have prediabetes, according to the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While diabetes is associated with significant long-term morbidity and mortality, with early identification and interventions, lifestyle modifications can significantly improve long-term health.

As with obesity (see “Focus on obesity” in OBG Management, May 2021), it is difficult to address lifestyle modifications with patients who have diabetes. However, many apps can be leveraged to aid physicians in this effort.

Diabetes app considerations

Obstetrician-gynecologists can play a pivotal role in helping to screen women for diabetes. When applying the ACOG-recommended rubric to evaluate the quality of an app that is targeted to address screening and diagnosing diabetes, it’s important to consider the app’s timeliness, authority, usefulness, and design.

There are point-of-care apps that include a few simple questions that can quickly identify which women should be screened. Some apps combine screening questions with testing results to streamline screening and diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes. These apps also provide clinical content to help physicians educate, initiate, and even treat diabetes if they desire.

A wealth of patient-centered apps are available to help patients address a diagnosis of diabetes. Apps that provide real-time feedback, motivational features to engage the user, and links to nutritional, fitness, and diabetic goals provide a woman with a comprehensive and personalized experience that can considerably improve health.

By incorporating apps and engaging with our patients on app technology, ObGyns can successfully partner with women to decrease morbidity with respect to diabetes mellitus and its long-term implications. ●

Diabetes mellitus affects 10% of the US population, and as many as one-third of US adults have prediabetes, according to the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While diabetes is associated with significant long-term morbidity and mortality, with early identification and interventions, lifestyle modifications can significantly improve long-term health.

As with obesity (see “Focus on obesity” in OBG Management, May 2021), it is difficult to address lifestyle modifications with patients who have diabetes. However, many apps can be leveraged to aid physicians in this effort.

Diabetes app considerations

Obstetrician-gynecologists can play a pivotal role in helping to screen women for diabetes. When applying the ACOG-recommended rubric to evaluate the quality of an app that is targeted to address screening and diagnosing diabetes, it’s important to consider the app’s timeliness, authority, usefulness, and design.

There are point-of-care apps that include a few simple questions that can quickly identify which women should be screened. Some apps combine screening questions with testing results to streamline screening and diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes. These apps also provide clinical content to help physicians educate, initiate, and even treat diabetes if they desire.

A wealth of patient-centered apps are available to help patients address a diagnosis of diabetes. Apps that provide real-time feedback, motivational features to engage the user, and links to nutritional, fitness, and diabetic goals provide a woman with a comprehensive and personalized experience that can considerably improve health.

By incorporating apps and engaging with our patients on app technology, ObGyns can successfully partner with women to decrease morbidity with respect to diabetes mellitus and its long-term implications. ●

Adverse pregnancy outcomes and later cardiovascular disease

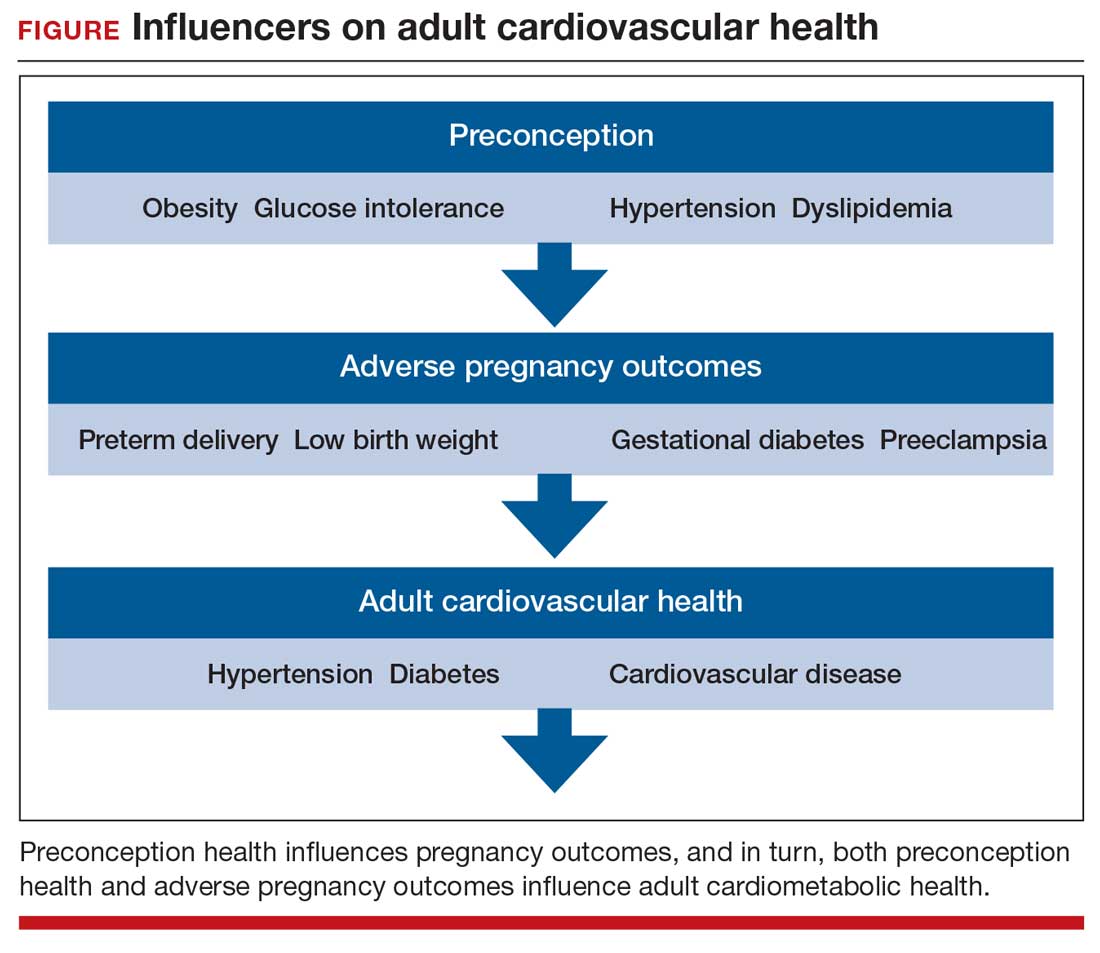

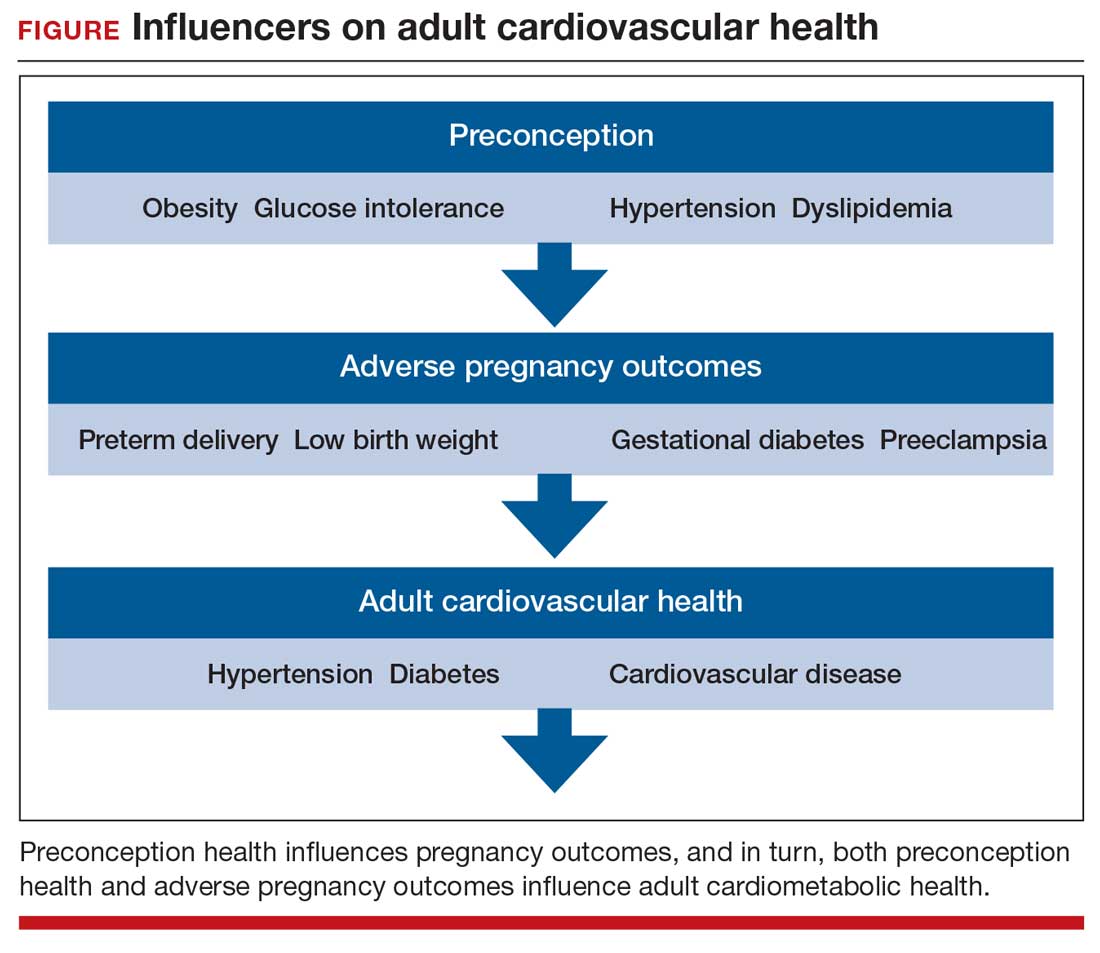

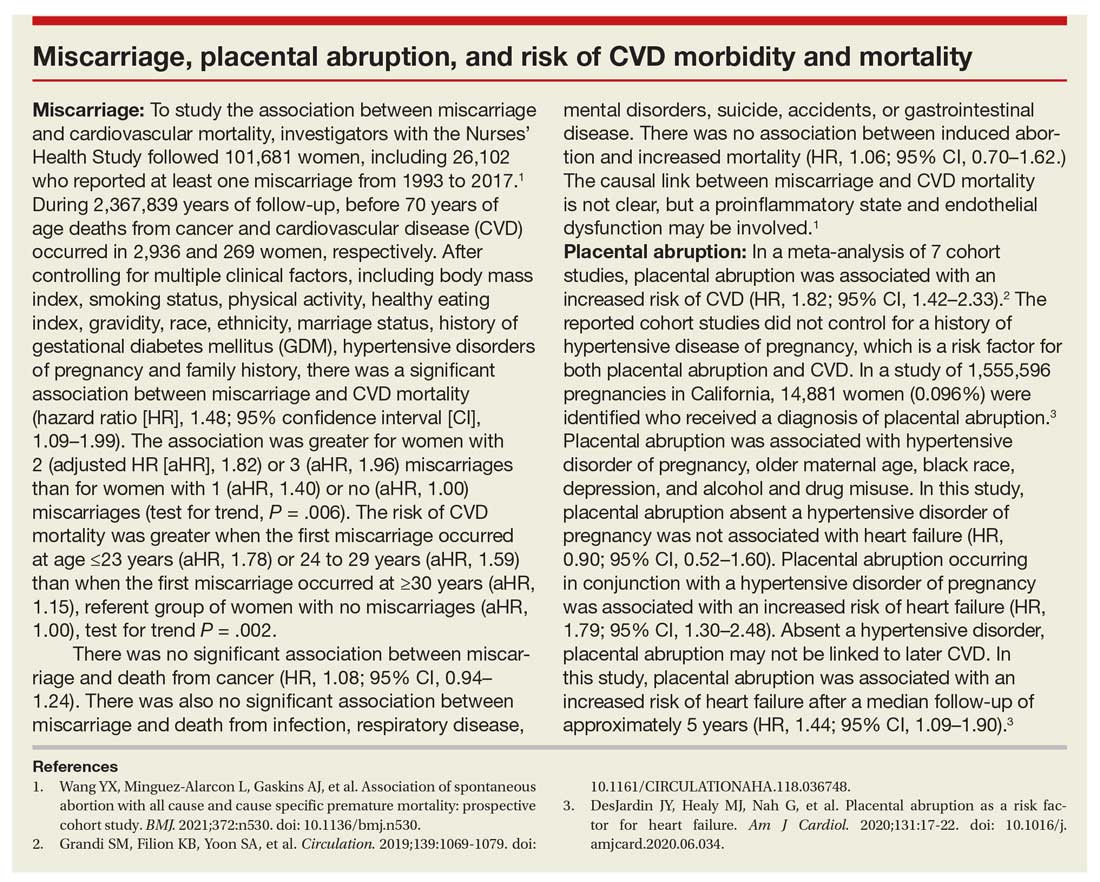

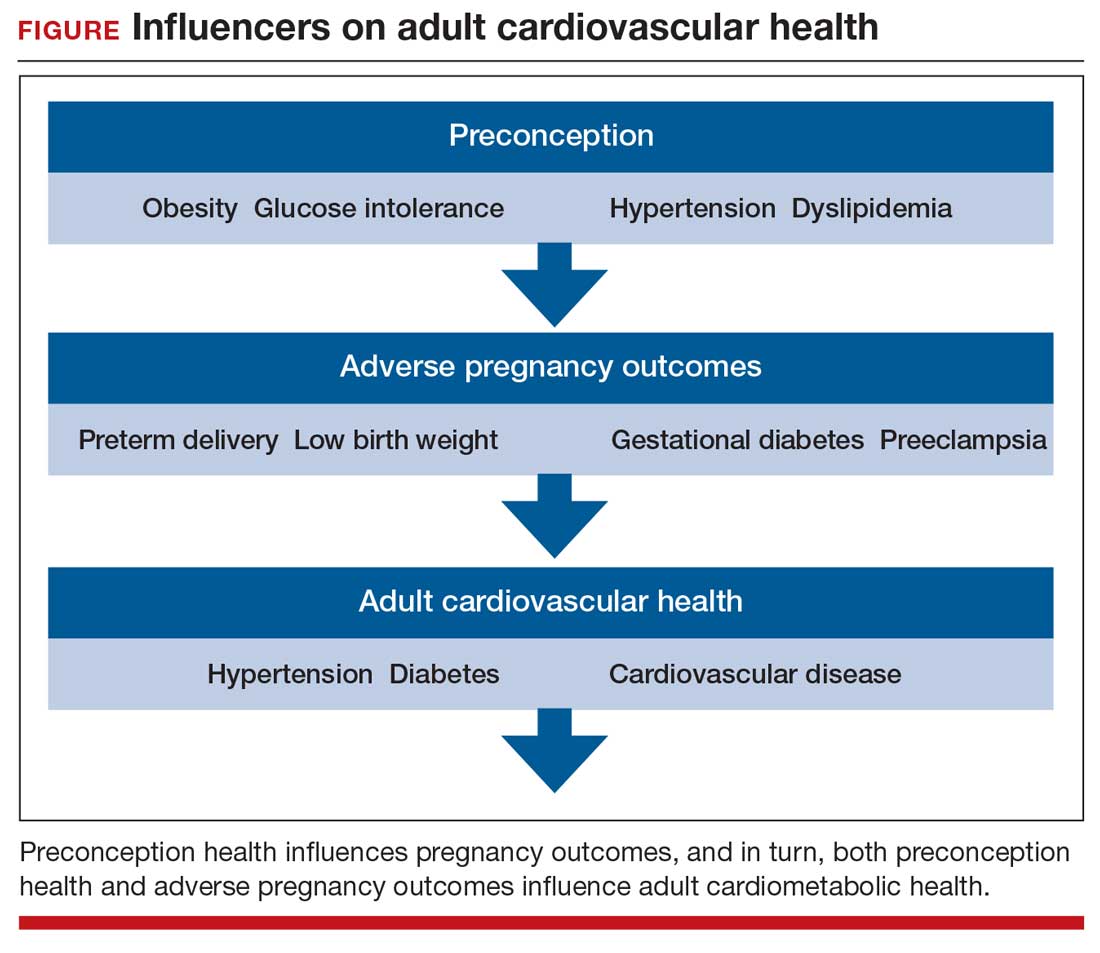

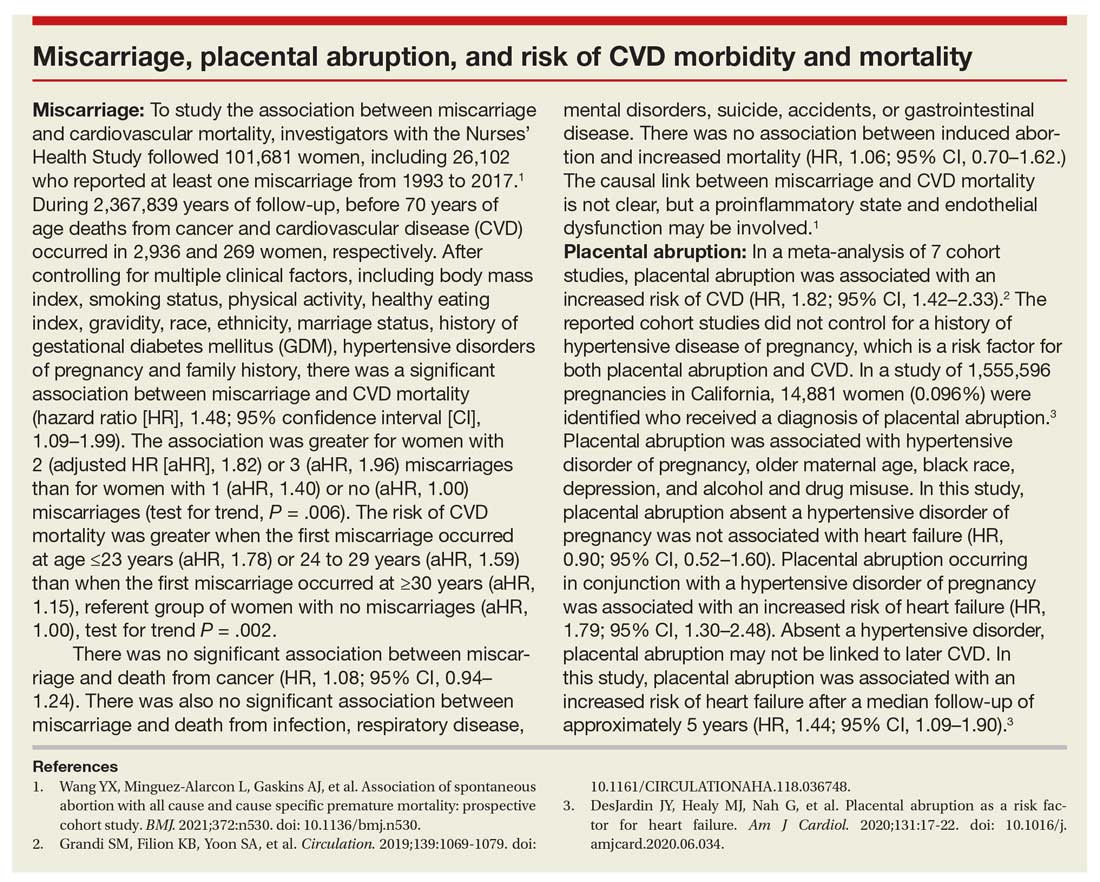

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

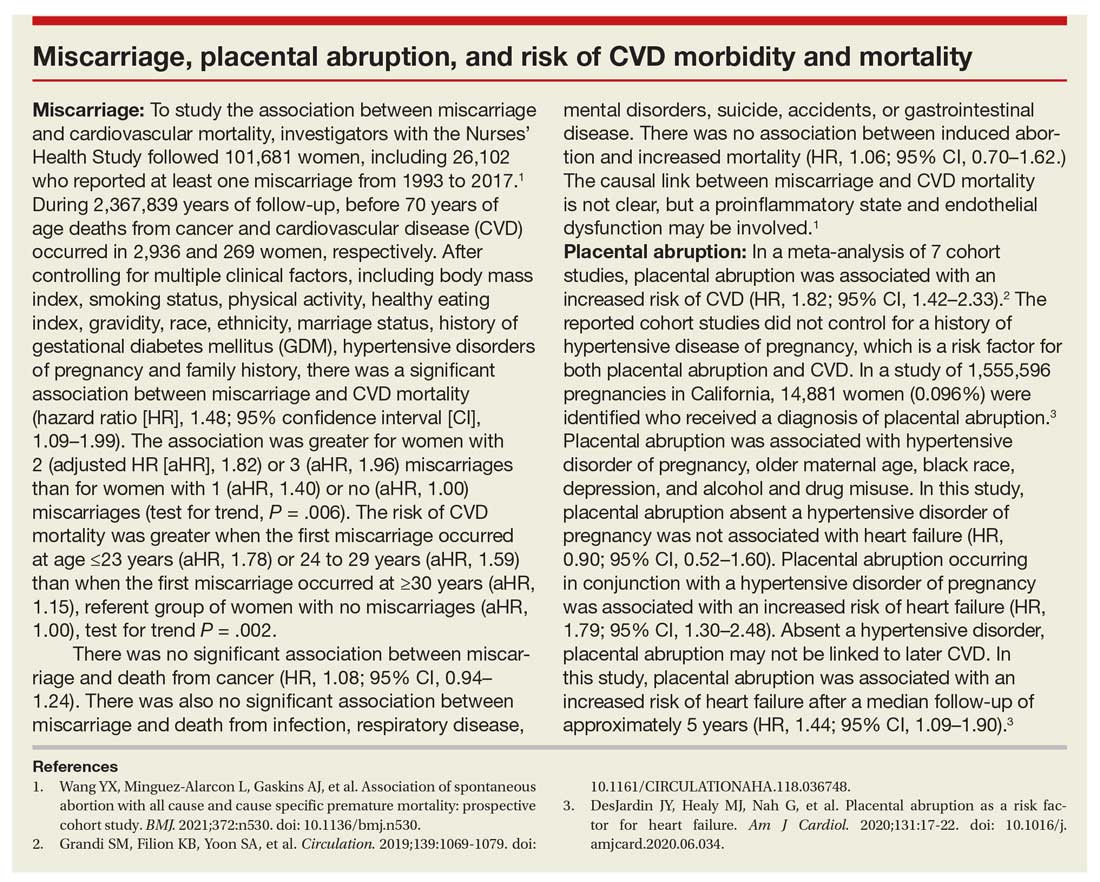

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk