User login

VIDEO: Novel postpartum depression drug effective in phase 3 trial

AUSTIN, TEXAS – A novel therapeutic agent shows promise for postpartum depression in a phase 3 trial presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

, according to presenter Christine Clemson, PhD, senior medical director at Sage Therapeutics, the company developing brexanolone.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study enrolled 138 women who were 6 months postpartum or less, and had been diagnosed with a major depressive episode during the third trimester or at 4 or fewer weeks postpartum, and had a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score of 26 or greater.

They were randomized to either brexanolone 60 mcg/kg/hour or 90 mcg/kg/hour administered intravenously over 60 hours as inpatients, or placebo. All three groups were an average aged 27 years old, the majority were white, and they had a HAM-D score between 28.4 and 29.1 at baseline.

After the first 60 hours of treatment, patients in the brexanolone group had mean reductions in the HAM-D score of about 20 in the 60 mcg group (P less than .01) and 18 in the 90 mcg group (P less than .05), compared with almost 14 in the placebo group. This was the primary endpoint,

Patients retained improvement through day 30, while those in the placebo group experienced a slight swing in the opposite direction.

Adverse effects in the brexanolone-treated groups were minimal; the majority of events reported were headaches or dizziness. However, Dr. Clemson said that some patients had to stop breastfeeding for a week.

An application for brexanolone for treating postpartum depression was submitted to the Food and Drug Administration on April 23; if approved, it would be the first drug of its kind to become available to treat postpartum depression.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics; two of the six authors are company employees. Two authors, including the lead author, are from the department of psychiatry, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

SOURCE: S. Meltzer-Brody S et al. ACOG 2018, Poster 29B.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – A novel therapeutic agent shows promise for postpartum depression in a phase 3 trial presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

, according to presenter Christine Clemson, PhD, senior medical director at Sage Therapeutics, the company developing brexanolone.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study enrolled 138 women who were 6 months postpartum or less, and had been diagnosed with a major depressive episode during the third trimester or at 4 or fewer weeks postpartum, and had a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score of 26 or greater.

They were randomized to either brexanolone 60 mcg/kg/hour or 90 mcg/kg/hour administered intravenously over 60 hours as inpatients, or placebo. All three groups were an average aged 27 years old, the majority were white, and they had a HAM-D score between 28.4 and 29.1 at baseline.

After the first 60 hours of treatment, patients in the brexanolone group had mean reductions in the HAM-D score of about 20 in the 60 mcg group (P less than .01) and 18 in the 90 mcg group (P less than .05), compared with almost 14 in the placebo group. This was the primary endpoint,

Patients retained improvement through day 30, while those in the placebo group experienced a slight swing in the opposite direction.

Adverse effects in the brexanolone-treated groups were minimal; the majority of events reported were headaches or dizziness. However, Dr. Clemson said that some patients had to stop breastfeeding for a week.

An application for brexanolone for treating postpartum depression was submitted to the Food and Drug Administration on April 23; if approved, it would be the first drug of its kind to become available to treat postpartum depression.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics; two of the six authors are company employees. Two authors, including the lead author, are from the department of psychiatry, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

SOURCE: S. Meltzer-Brody S et al. ACOG 2018, Poster 29B.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – A novel therapeutic agent shows promise for postpartum depression in a phase 3 trial presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

, according to presenter Christine Clemson, PhD, senior medical director at Sage Therapeutics, the company developing brexanolone.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study enrolled 138 women who were 6 months postpartum or less, and had been diagnosed with a major depressive episode during the third trimester or at 4 or fewer weeks postpartum, and had a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score of 26 or greater.

They were randomized to either brexanolone 60 mcg/kg/hour or 90 mcg/kg/hour administered intravenously over 60 hours as inpatients, or placebo. All three groups were an average aged 27 years old, the majority were white, and they had a HAM-D score between 28.4 and 29.1 at baseline.

After the first 60 hours of treatment, patients in the brexanolone group had mean reductions in the HAM-D score of about 20 in the 60 mcg group (P less than .01) and 18 in the 90 mcg group (P less than .05), compared with almost 14 in the placebo group. This was the primary endpoint,

Patients retained improvement through day 30, while those in the placebo group experienced a slight swing in the opposite direction.

Adverse effects in the brexanolone-treated groups were minimal; the majority of events reported were headaches or dizziness. However, Dr. Clemson said that some patients had to stop breastfeeding for a week.

An application for brexanolone for treating postpartum depression was submitted to the Food and Drug Administration on April 23; if approved, it would be the first drug of its kind to become available to treat postpartum depression.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics; two of the six authors are company employees. Two authors, including the lead author, are from the department of psychiatry, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

SOURCE: S. Meltzer-Brody S et al. ACOG 2018, Poster 29B.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

VIDEO: Prepaid prenatal care bundle delivers quality care to uninsured

AUSTIN, TEXAS – The experiences of one safety net hospital showed the feasibility of delivering prenatal care to low-risk, uninsured women in a prepaid, bundled package.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

. The adjusted odds ratio for predefined adequacy of care was 3.75 for the low-risk bundled care recipients compared with those on Medicaid (P = .015), according to the experience at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, presented at the annual clinical and scientific sessions of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For hospitals with large numbers of undocumented patients and others who are uninsured but ineligible for Medicaid, considerable cost savings could be realized, said Erin Duncan, MD, who completed the work while in training at Emory University.

“Using data from previous studies, Grady Memorial Hospital could see a savings of over $1 million per year by providing care to its undocumented population,” she and her collaborators wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Dr. Duncan said that since implementation in 2010, about 40% of deliveries at the facility have occurred under the “Grady Healthy Baby” (GHB) bundle.

The one-payment package of bundled prenatal care was developed assuming that most participants would have low-risk pregnancies, said Dr. Duncan, who is currently an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Atlanta area.

To look further into maternal and pregnancy characteristics of GHB participants and compare them with those on Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators performed a retrospective cohort study. Examining viable singleton pregnancies delivered at Grady between 2011 and 2014, the investigators compared 100 randomly selected GHB participants with 100 randomly selected Medicaid participants.

Comparing patients receiving care under GHB and Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her colleagues found that “GHB participants were older, more likely to be Hispanic, and less likely to be black compared to Medicaid recipients (P less than .001 for all,)” they wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Hispanic patients made up 59% of the GHB group, compared with 8% of the Medicaid group, said Dr. Duncan, adding in an interview that over half of Hispanics in the state of Georgia during the study period were undocumented.

Parity was similar between the two groups, as were gestational age at delivery and mode of delivery.

In their analysis, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators looked at both complexity and adequacy of care for the 200 patients studied. They found that there was no significant difference in the number of patients in each care group who remained low risk throughout their pregnancies, transitioned from low risk to high risk, or entered prenatal care with a high risk pregnancy, a circumstance that occurred in about 1 in 10 pregnancies.

For the approximately 50% of patients who remained low risk through their pregnancies, care under the GHB model was significantly more likely to be assessed as adequate throughout pregnancy than for those patients on Medicaid (61.7% vs 35.5%, P = .001).

Patients who became high risk during prenatal care were no more likely to receive adequate care under one model than the other.

For high risk patients, delivery of adequate care happened only under the Medicaid care model. Numbers in this group were small; 7 of 100 GHB and 15 of 100 Medicaid patients entered prenatal care with high risk pregnancies. However, no high risk GHB patients received adequate care, while that standard was met for 80% of the Medicaid patients (P less than .001).

Adequacy of care was assessed using the Kotelchuck index for low-risk pregnancies; this model assumes care is “adequate” when 80% of the number of expected visits were attended by the woman receiving prenatal care. Additionally, care was deemed adequate for high-risk pregnancies if at least 80% of the number of expected ultrasound appointments were attended.

“In the current political climate, this study has implications for all pregnancies that begin as uninsured, regardless of maternal documentation status,” wrote Dr. Duncan and her colleagues.

Dr. Duncan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Duncan, E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 28C.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – The experiences of one safety net hospital showed the feasibility of delivering prenatal care to low-risk, uninsured women in a prepaid, bundled package.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

. The adjusted odds ratio for predefined adequacy of care was 3.75 for the low-risk bundled care recipients compared with those on Medicaid (P = .015), according to the experience at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, presented at the annual clinical and scientific sessions of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For hospitals with large numbers of undocumented patients and others who are uninsured but ineligible for Medicaid, considerable cost savings could be realized, said Erin Duncan, MD, who completed the work while in training at Emory University.

“Using data from previous studies, Grady Memorial Hospital could see a savings of over $1 million per year by providing care to its undocumented population,” she and her collaborators wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Dr. Duncan said that since implementation in 2010, about 40% of deliveries at the facility have occurred under the “Grady Healthy Baby” (GHB) bundle.

The one-payment package of bundled prenatal care was developed assuming that most participants would have low-risk pregnancies, said Dr. Duncan, who is currently an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Atlanta area.

To look further into maternal and pregnancy characteristics of GHB participants and compare them with those on Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators performed a retrospective cohort study. Examining viable singleton pregnancies delivered at Grady between 2011 and 2014, the investigators compared 100 randomly selected GHB participants with 100 randomly selected Medicaid participants.

Comparing patients receiving care under GHB and Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her colleagues found that “GHB participants were older, more likely to be Hispanic, and less likely to be black compared to Medicaid recipients (P less than .001 for all,)” they wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Hispanic patients made up 59% of the GHB group, compared with 8% of the Medicaid group, said Dr. Duncan, adding in an interview that over half of Hispanics in the state of Georgia during the study period were undocumented.

Parity was similar between the two groups, as were gestational age at delivery and mode of delivery.

In their analysis, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators looked at both complexity and adequacy of care for the 200 patients studied. They found that there was no significant difference in the number of patients in each care group who remained low risk throughout their pregnancies, transitioned from low risk to high risk, or entered prenatal care with a high risk pregnancy, a circumstance that occurred in about 1 in 10 pregnancies.

For the approximately 50% of patients who remained low risk through their pregnancies, care under the GHB model was significantly more likely to be assessed as adequate throughout pregnancy than for those patients on Medicaid (61.7% vs 35.5%, P = .001).

Patients who became high risk during prenatal care were no more likely to receive adequate care under one model than the other.

For high risk patients, delivery of adequate care happened only under the Medicaid care model. Numbers in this group were small; 7 of 100 GHB and 15 of 100 Medicaid patients entered prenatal care with high risk pregnancies. However, no high risk GHB patients received adequate care, while that standard was met for 80% of the Medicaid patients (P less than .001).

Adequacy of care was assessed using the Kotelchuck index for low-risk pregnancies; this model assumes care is “adequate” when 80% of the number of expected visits were attended by the woman receiving prenatal care. Additionally, care was deemed adequate for high-risk pregnancies if at least 80% of the number of expected ultrasound appointments were attended.

“In the current political climate, this study has implications for all pregnancies that begin as uninsured, regardless of maternal documentation status,” wrote Dr. Duncan and her colleagues.

Dr. Duncan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Duncan, E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 28C.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – The experiences of one safety net hospital showed the feasibility of delivering prenatal care to low-risk, uninsured women in a prepaid, bundled package.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

. The adjusted odds ratio for predefined adequacy of care was 3.75 for the low-risk bundled care recipients compared with those on Medicaid (P = .015), according to the experience at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, presented at the annual clinical and scientific sessions of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For hospitals with large numbers of undocumented patients and others who are uninsured but ineligible for Medicaid, considerable cost savings could be realized, said Erin Duncan, MD, who completed the work while in training at Emory University.

“Using data from previous studies, Grady Memorial Hospital could see a savings of over $1 million per year by providing care to its undocumented population,” she and her collaborators wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Dr. Duncan said that since implementation in 2010, about 40% of deliveries at the facility have occurred under the “Grady Healthy Baby” (GHB) bundle.

The one-payment package of bundled prenatal care was developed assuming that most participants would have low-risk pregnancies, said Dr. Duncan, who is currently an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Atlanta area.

To look further into maternal and pregnancy characteristics of GHB participants and compare them with those on Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators performed a retrospective cohort study. Examining viable singleton pregnancies delivered at Grady between 2011 and 2014, the investigators compared 100 randomly selected GHB participants with 100 randomly selected Medicaid participants.

Comparing patients receiving care under GHB and Medicaid, Dr. Duncan and her colleagues found that “GHB participants were older, more likely to be Hispanic, and less likely to be black compared to Medicaid recipients (P less than .001 for all,)” they wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

Hispanic patients made up 59% of the GHB group, compared with 8% of the Medicaid group, said Dr. Duncan, adding in an interview that over half of Hispanics in the state of Georgia during the study period were undocumented.

Parity was similar between the two groups, as were gestational age at delivery and mode of delivery.

In their analysis, Dr. Duncan and her collaborators looked at both complexity and adequacy of care for the 200 patients studied. They found that there was no significant difference in the number of patients in each care group who remained low risk throughout their pregnancies, transitioned from low risk to high risk, or entered prenatal care with a high risk pregnancy, a circumstance that occurred in about 1 in 10 pregnancies.

For the approximately 50% of patients who remained low risk through their pregnancies, care under the GHB model was significantly more likely to be assessed as adequate throughout pregnancy than for those patients on Medicaid (61.7% vs 35.5%, P = .001).

Patients who became high risk during prenatal care were no more likely to receive adequate care under one model than the other.

For high risk patients, delivery of adequate care happened only under the Medicaid care model. Numbers in this group were small; 7 of 100 GHB and 15 of 100 Medicaid patients entered prenatal care with high risk pregnancies. However, no high risk GHB patients received adequate care, while that standard was met for 80% of the Medicaid patients (P less than .001).

Adequacy of care was assessed using the Kotelchuck index for low-risk pregnancies; this model assumes care is “adequate” when 80% of the number of expected visits were attended by the woman receiving prenatal care. Additionally, care was deemed adequate for high-risk pregnancies if at least 80% of the number of expected ultrasound appointments were attended.

“In the current political climate, this study has implications for all pregnancies that begin as uninsured, regardless of maternal documentation status,” wrote Dr. Duncan and her colleagues.

Dr. Duncan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Duncan, E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 28C.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Time to scrap LMWH for prevention of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications?

SAN DIEGO – Low molecular weight heparin does not appear to reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior such complications, according to Marc Rodger, MD.

“It’s time to put the needles away for pregnant patients,” he said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

The pathophysiology of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications includes placental thrombosis. Thrombophilias predispose to the development of thrombosis in slow-flow circulation of the placenta. “It’s possible that the etiology mix of placental-mediated pregnancy complications includes thrombophilias, and by extension, that anticoagulants would prevent these complications,” said Dr. Rodger, a senior scientist at the hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa.

In a study from 1999, researchers demonstrated that patients with pregnancy-mediated placental complications were 8.2 times more likely to develop thrombophilia, compared with controls (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9-13). “But as with positive initial case-control studies, subsequent work downplayed this association,” Dr. Rodger said. “Now, we’re at a point where we recognize that thrombophilias are weakly associated with recurrent early loss, late pregnancy loss, and severe preeclampsia ([odds ratio] of about 1.5-2.0 for all associations), while thrombophilias are not associated with nonsevere preeclampsia and small for gestational age.”

Currently, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the preferred pharmacoprophylaxis in pregnancy. Unfractionated heparin, meanwhile, requires b.i.d. or t.i.d. injections, and has a 10-fold higher risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and a greater than 10-fold higher risk of osteoporotic fracture. Warfarin is teratogenic antepartum and inconvenient postpartum, while direct oral anticoagulants cross the placenta and enter breast milk.

Downsides of LMWH include the burden of self-injections and costs of over $10,000 per antepartum period, Dr. Rodger said. Common side effects include minor bleeding and elevated liver function tests, and it complicates regional anesthetic options at term. Uncommon side effects include major bleeding, skin reactions, and postpartum wound complications, while rare but serious complications include heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and osteoporotic fractures.

He offered a hypothetical case. A 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks asks you, “Should I be treated with LMWH in my next pregnancy?” What should you tell her? To answer this question, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a study-level meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials that included 848 pregnant women with prior placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Blood. 2014;123[6]:822-8). The primary objective was to determine the effect of LMWH in preventing placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior late placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. This included patients with or without thrombophilia who were treated with or without LMWH. The primary outcome was a composite of preeclampsia, birth of an SGA newborn, placental abruption, or pregnancy loss greater than 20 weeks. Overall, 67 (18.7%) of 358 of women being given prophylactic LMWH had recurrent severe placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with 127 (42.9%) of 296 women with no LMWH (relative risk reduction, 0.52; P = .01, indicating moderate heterogeneity). They identified similar relative risk reductions with LMWH for individual outcomes, including any preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, SGA below the 10th percentile, SGA below the 5th percentile, preterm delivery less than 37 weeks, and preterm delivery less than 34 weeks with minimal heterogeneity. They concluded that LMWH “may be a promising therapy for recurrent, especially severe, placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, but further research is required.”

At the meeting, Dr. Rodger noted that the positive studies in the analysis were single-center trials, “which are generally acknowledged to be of a lesser methodologic quality, and the majority of patients in these single-center trials are from a small area in the south of France. Multicenter trials don’t show an effect, so is it single-centeredness or is it something else? The other feature that’s distinct is that the positive trials recruited patients with prior severe complications only, while the negative trials included patients with nonsevere complications. So maybe LMWH works in patients who have a very strong phenotype that have had very bad prior complications. We can’t tease that out with a study-level meta-analysis because we’re getting average effects over heterogeneous groups of patients.”

To expand on the study-level meta-analysis, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials of 963 patients conducted between 2000 and 2013 of LMWH to prevent recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Lancet. 2016;388:2629-41). “In this approach you get individual patient data from the trials, and you create a new randomized, controlled data set,” he explained. “That way we could tease out the patients who have had the prior severe complications and whether their mild or severe outcomes are being prevented or not.”

The study’s composite primary outcome was one or more of the following: early-onset or severe preeclampsia, SGA newborn below the 5th percentile, late pregnancy loss (over 20 weeks), or placental abruption. Dr. Rodger and his associates found that LMWH did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with patients who did not receive LMWH (14% vs. 22%, respectively; P = .09). In subgroup analyses, however, LMWH in multicenter trials reduced the primary outcome in women with previous abruption (P = .006) but not in any of the other subgroups of previous complications. “There were small numbers of patients in this subgroup, though, so I would use caution,” Dr. Rodger said. Two recent randomized, controlled trials from separate investigators further support the overall null findings of the individual patient data meta-analysis (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[5]:1053-63 and Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;216[3]:296.e1-296.e14).

Revisiting the hypothetical case of a 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks, Dr. Rodger said that he would “definitely not” recommend LMWH during her next pregnancy.

He acknowledged limitations of the systematic review, including the limited numbers of patients in subgroups and the large differences between single-center and multicenter trials. “We still can’t explain this, and it remains an open question that bugs me,” he said. “This has been seen in many disease areas. Empirically, single-centeredness leans toward positivity.”

He called for more research in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Dr. Rodger reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Low molecular weight heparin does not appear to reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior such complications, according to Marc Rodger, MD.

“It’s time to put the needles away for pregnant patients,” he said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

The pathophysiology of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications includes placental thrombosis. Thrombophilias predispose to the development of thrombosis in slow-flow circulation of the placenta. “It’s possible that the etiology mix of placental-mediated pregnancy complications includes thrombophilias, and by extension, that anticoagulants would prevent these complications,” said Dr. Rodger, a senior scientist at the hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa.

In a study from 1999, researchers demonstrated that patients with pregnancy-mediated placental complications were 8.2 times more likely to develop thrombophilia, compared with controls (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9-13). “But as with positive initial case-control studies, subsequent work downplayed this association,” Dr. Rodger said. “Now, we’re at a point where we recognize that thrombophilias are weakly associated with recurrent early loss, late pregnancy loss, and severe preeclampsia ([odds ratio] of about 1.5-2.0 for all associations), while thrombophilias are not associated with nonsevere preeclampsia and small for gestational age.”

Currently, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the preferred pharmacoprophylaxis in pregnancy. Unfractionated heparin, meanwhile, requires b.i.d. or t.i.d. injections, and has a 10-fold higher risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and a greater than 10-fold higher risk of osteoporotic fracture. Warfarin is teratogenic antepartum and inconvenient postpartum, while direct oral anticoagulants cross the placenta and enter breast milk.

Downsides of LMWH include the burden of self-injections and costs of over $10,000 per antepartum period, Dr. Rodger said. Common side effects include minor bleeding and elevated liver function tests, and it complicates regional anesthetic options at term. Uncommon side effects include major bleeding, skin reactions, and postpartum wound complications, while rare but serious complications include heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and osteoporotic fractures.

He offered a hypothetical case. A 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks asks you, “Should I be treated with LMWH in my next pregnancy?” What should you tell her? To answer this question, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a study-level meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials that included 848 pregnant women with prior placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Blood. 2014;123[6]:822-8). The primary objective was to determine the effect of LMWH in preventing placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior late placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. This included patients with or without thrombophilia who were treated with or without LMWH. The primary outcome was a composite of preeclampsia, birth of an SGA newborn, placental abruption, or pregnancy loss greater than 20 weeks. Overall, 67 (18.7%) of 358 of women being given prophylactic LMWH had recurrent severe placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with 127 (42.9%) of 296 women with no LMWH (relative risk reduction, 0.52; P = .01, indicating moderate heterogeneity). They identified similar relative risk reductions with LMWH for individual outcomes, including any preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, SGA below the 10th percentile, SGA below the 5th percentile, preterm delivery less than 37 weeks, and preterm delivery less than 34 weeks with minimal heterogeneity. They concluded that LMWH “may be a promising therapy for recurrent, especially severe, placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, but further research is required.”

At the meeting, Dr. Rodger noted that the positive studies in the analysis were single-center trials, “which are generally acknowledged to be of a lesser methodologic quality, and the majority of patients in these single-center trials are from a small area in the south of France. Multicenter trials don’t show an effect, so is it single-centeredness or is it something else? The other feature that’s distinct is that the positive trials recruited patients with prior severe complications only, while the negative trials included patients with nonsevere complications. So maybe LMWH works in patients who have a very strong phenotype that have had very bad prior complications. We can’t tease that out with a study-level meta-analysis because we’re getting average effects over heterogeneous groups of patients.”

To expand on the study-level meta-analysis, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials of 963 patients conducted between 2000 and 2013 of LMWH to prevent recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Lancet. 2016;388:2629-41). “In this approach you get individual patient data from the trials, and you create a new randomized, controlled data set,” he explained. “That way we could tease out the patients who have had the prior severe complications and whether their mild or severe outcomes are being prevented or not.”

The study’s composite primary outcome was one or more of the following: early-onset or severe preeclampsia, SGA newborn below the 5th percentile, late pregnancy loss (over 20 weeks), or placental abruption. Dr. Rodger and his associates found that LMWH did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with patients who did not receive LMWH (14% vs. 22%, respectively; P = .09). In subgroup analyses, however, LMWH in multicenter trials reduced the primary outcome in women with previous abruption (P = .006) but not in any of the other subgroups of previous complications. “There were small numbers of patients in this subgroup, though, so I would use caution,” Dr. Rodger said. Two recent randomized, controlled trials from separate investigators further support the overall null findings of the individual patient data meta-analysis (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[5]:1053-63 and Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;216[3]:296.e1-296.e14).

Revisiting the hypothetical case of a 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks, Dr. Rodger said that he would “definitely not” recommend LMWH during her next pregnancy.

He acknowledged limitations of the systematic review, including the limited numbers of patients in subgroups and the large differences between single-center and multicenter trials. “We still can’t explain this, and it remains an open question that bugs me,” he said. “This has been seen in many disease areas. Empirically, single-centeredness leans toward positivity.”

He called for more research in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Dr. Rodger reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Low molecular weight heparin does not appear to reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior such complications, according to Marc Rodger, MD.

“It’s time to put the needles away for pregnant patients,” he said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

The pathophysiology of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications includes placental thrombosis. Thrombophilias predispose to the development of thrombosis in slow-flow circulation of the placenta. “It’s possible that the etiology mix of placental-mediated pregnancy complications includes thrombophilias, and by extension, that anticoagulants would prevent these complications,” said Dr. Rodger, a senior scientist at the hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa.

In a study from 1999, researchers demonstrated that patients with pregnancy-mediated placental complications were 8.2 times more likely to develop thrombophilia, compared with controls (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9-13). “But as with positive initial case-control studies, subsequent work downplayed this association,” Dr. Rodger said. “Now, we’re at a point where we recognize that thrombophilias are weakly associated with recurrent early loss, late pregnancy loss, and severe preeclampsia ([odds ratio] of about 1.5-2.0 for all associations), while thrombophilias are not associated with nonsevere preeclampsia and small for gestational age.”

Currently, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the preferred pharmacoprophylaxis in pregnancy. Unfractionated heparin, meanwhile, requires b.i.d. or t.i.d. injections, and has a 10-fold higher risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and a greater than 10-fold higher risk of osteoporotic fracture. Warfarin is teratogenic antepartum and inconvenient postpartum, while direct oral anticoagulants cross the placenta and enter breast milk.

Downsides of LMWH include the burden of self-injections and costs of over $10,000 per antepartum period, Dr. Rodger said. Common side effects include minor bleeding and elevated liver function tests, and it complicates regional anesthetic options at term. Uncommon side effects include major bleeding, skin reactions, and postpartum wound complications, while rare but serious complications include heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and osteoporotic fractures.

He offered a hypothetical case. A 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks asks you, “Should I be treated with LMWH in my next pregnancy?” What should you tell her? To answer this question, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a study-level meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials that included 848 pregnant women with prior placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Blood. 2014;123[6]:822-8). The primary objective was to determine the effect of LMWH in preventing placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with prior late placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. This included patients with or without thrombophilia who were treated with or without LMWH. The primary outcome was a composite of preeclampsia, birth of an SGA newborn, placental abruption, or pregnancy loss greater than 20 weeks. Overall, 67 (18.7%) of 358 of women being given prophylactic LMWH had recurrent severe placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with 127 (42.9%) of 296 women with no LMWH (relative risk reduction, 0.52; P = .01, indicating moderate heterogeneity). They identified similar relative risk reductions with LMWH for individual outcomes, including any preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, SGA below the 10th percentile, SGA below the 5th percentile, preterm delivery less than 37 weeks, and preterm delivery less than 34 weeks with minimal heterogeneity. They concluded that LMWH “may be a promising therapy for recurrent, especially severe, placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, but further research is required.”

At the meeting, Dr. Rodger noted that the positive studies in the analysis were single-center trials, “which are generally acknowledged to be of a lesser methodologic quality, and the majority of patients in these single-center trials are from a small area in the south of France. Multicenter trials don’t show an effect, so is it single-centeredness or is it something else? The other feature that’s distinct is that the positive trials recruited patients with prior severe complications only, while the negative trials included patients with nonsevere complications. So maybe LMWH works in patients who have a very strong phenotype that have had very bad prior complications. We can’t tease that out with a study-level meta-analysis because we’re getting average effects over heterogeneous groups of patients.”

To expand on the study-level meta-analysis, Dr. Rodger and his associates conducted a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials of 963 patients conducted between 2000 and 2013 of LMWH to prevent recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications (Lancet. 2016;388:2629-41). “In this approach you get individual patient data from the trials, and you create a new randomized, controlled data set,” he explained. “That way we could tease out the patients who have had the prior severe complications and whether their mild or severe outcomes are being prevented or not.”

The study’s composite primary outcome was one or more of the following: early-onset or severe preeclampsia, SGA newborn below the 5th percentile, late pregnancy loss (over 20 weeks), or placental abruption. Dr. Rodger and his associates found that LMWH did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, compared with patients who did not receive LMWH (14% vs. 22%, respectively; P = .09). In subgroup analyses, however, LMWH in multicenter trials reduced the primary outcome in women with previous abruption (P = .006) but not in any of the other subgroups of previous complications. “There were small numbers of patients in this subgroup, though, so I would use caution,” Dr. Rodger said. Two recent randomized, controlled trials from separate investigators further support the overall null findings of the individual patient data meta-analysis (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[5]:1053-63 and Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;216[3]:296.e1-296.e14).

Revisiting the hypothetical case of a 32-year-old woman with prior severe preeclampsia who delivered at 32 weeks, Dr. Rodger said that he would “definitely not” recommend LMWH during her next pregnancy.

He acknowledged limitations of the systematic review, including the limited numbers of patients in subgroups and the large differences between single-center and multicenter trials. “We still can’t explain this, and it remains an open question that bugs me,” he said. “This has been seen in many disease areas. Empirically, single-centeredness leans toward positivity.”

He called for more research in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Dr. Rodger reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Prolactin, the pituitary, and pregnancy: Where’s the balance?

CHICAGO – Management of fertility and reproduction for women with prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors is a balancing act, often in the absence of robust data to support clinical decision making. So judgment, communication, and paying attention to the patient become paramount considerations, said endocrinologist Mark Molitch, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The first step: restoring fertility

“Remember that our patients that have hyperprolactinemia are generally infertile,” said Dr. Molitch, Martha Leland Sherwin Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. “You really need to restore prolactin levels to close to normal, or normal, to allow ovulation to occur,” he said.

Dr. Molitch noted that up to 94% of women with hyperprolactinemia will initially have anovulation, amenorrhea, and infertility, but restoration of normal prolactin levels usually corrects these.

“If you have a patient where you are unable to restore prolactin levels to normal, there are other methods” to consider. Patients may end up using clomiphene, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropins, or even moving to in vitro fertilization in these cases, said Dr. Molitch.

Preferable to any of these, though, is achieving normal prolactin levels.

In patients who are hyperprolactinemic, “the major action is occurring at the hypothalamic level,” with decreases in pulsatile secretion of GnRH, said Dr. Molitch. Next, there are resultant decreases in gonadotropin secretion, which in turn interrupt the ovary’s normal physiology. “There’s also an interruption in positive estrogen feedback in this cycle,” he said.

“So what’s new in this area is kisspeptin,” Dr. Molitch said, adding that the peptide activates the G-protein coupled receptor GPR54, found in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Infusion of kisspeptin stimulates secretion of luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Conversely, mutations that inactivate GPR43 result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, while activating mutations are associated with centrally caused precocious puberty (Biol Reprod. 2011 Oct;85[4]:650-60; Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 Oct 22;346[1-2]:29-3).

From this and other work, endocrinologists now know that kisspeptin is “very likely involved in puberty initiation and in response to fasting,” said Dr. Molitch. It’s now thought that high prolactin levels alter kisspeptin levels, “which then causes the further downstream effects,” said Dr. Molitch.

Dopamine agonists and pregnancy

Dopamine agonists are the primary therapies used for patients with prolactinomas and hyperprolactinemia. In patients seeking fertility, the dopamine agonist is usually continued just through the first few weeks of pregnancy, until the patient misses her first menstrual period, he said.

Establishing the menstrual interval is key to knowing when to stop the dopamine agonist, though. “We often use barrier contraceptives, so we can tell what the menstrual interval is – so we can tell when somebody’s missed her period,” Dr. Molitch explained.

“Most of the safety data on these drugs … are based on that relatively short period of exposure,” said Dr. Molitch. “As far as long-term use during pregnancy, only about 100 patients who took bromocriptine throughout pregnancy have been reported,” with two minor fetal anomalies reported from this series of patients, he said.

Though fewer than 20 cases have been reported of cabergoline being continued throughout a pregnancy, “there have not been any problems with that,” said Dr. Molitch.

Overall, over 6,000 pregnancies with bromocriptine exposure, as well as over 1,000 with cabergoline, have now been reported.

Dr. Molitch summarized the aggregate safety data for each dopamine agonist: “When we look at the adverse outcomes that occurred with either of these drugs, as far as spontaneous abortions or terminations, premature deliveries, multiple births, and, of course, the most important thing here being major malformations … in neither drug is there an increase in these adverse outcomes” (J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Jan;41[1]:129-41).

“In my own mind now, I think that the number of cases with cabergoline now is quite sufficient to justify the safety of its use during pregnancy,” Dr. Molitch said. “However, this is sort of an individualized decision between you – the clinician – as well as your patient to make”: whether to trust the 1,000-case–strong data for cabergoline. “I no longer change patients from cabergoline to bromocriptine because of safety concerns. I think that cabergoline is perfectly safe,” he added.

What if the tumor grows in pregnancy?

During pregnancy, high estrogen levels from the placenta can stimulate prolactinoma growth, and the dopamine agonist’s inhibitory effect is gone once that medication’s been stopped. This means that “We have both a ‘push’ and a decrease in the ‘pull’ here, so you may have tumor enlargement,” said Dr. Molitch.

The risk for tumor enlargement in microadenomas is about 2.4%, and ranges to about 16% for enlargement of macroadenomas during pregnancy. For macroadenomas, “you might consider a prepregnancy debulking of the tumor,” Dr. Molitch said.

It’s reasonable to stop a dopamine agonist once pregnancy’s been established in a patient with a prolactinoma, and “follow the patient symptomatically every few months,” letting suspicious new symptoms like visual changes or headaches be the prompt for visual field exam and magnetic resonance imaging without contrast, said Dr. Molitch.

Though it’s not FDA approved, consideration can be given to continuing a dopamine agonist in a patient with a large prepregnancy adenoma throughout pregnancy – and if the tumor is enlarging significantly, the dopamine agonist should be restarted if it’s been withheld, said Dr. Molitch. Finally, surgery is the option if an enlarging tumor doesn’t respond to a dopamine agonist, unless the pregnancy is far enough along that delivery is a safe option.

“It’s important to actually document that there’s tumor enlargement, because if you’re going to do something like restarting a drug or even surgery, you really want to make sure that it’s the enlarging tumor that’s causing the problem,” said Dr. Molitch.

Postpartum prolactinoma considerations

Postpartum, even though prolactin secretion is upped by nursing, “there are no data to show that lactation stimulates tumor growth,” said Dr. Molitch. “I don’t see that there’s any problem with somebody nursing if they choose to do so.” However, “You certainly cannot restart the dopamine agonist, because that will lower prolactin levels and prevent that person from being able to nurse,” he said.

For reasons that are not clear, prolactin levels often drop post partum. Accordingly, it’s a reasonable approach in a nursing mother with mildly elevated prolactin levels to wait until nursing is done to see if menses resume spontaneously before restarting the dopamine agonist, said Dr. Molitch.

Dr. Molitch reported receiving fees and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed that his spouse holds stock in Amgen.

SOURCE: Molitch M ENDO 2018. Abstract M02-2.

CHICAGO – Management of fertility and reproduction for women with prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors is a balancing act, often in the absence of robust data to support clinical decision making. So judgment, communication, and paying attention to the patient become paramount considerations, said endocrinologist Mark Molitch, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The first step: restoring fertility

“Remember that our patients that have hyperprolactinemia are generally infertile,” said Dr. Molitch, Martha Leland Sherwin Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. “You really need to restore prolactin levels to close to normal, or normal, to allow ovulation to occur,” he said.

Dr. Molitch noted that up to 94% of women with hyperprolactinemia will initially have anovulation, amenorrhea, and infertility, but restoration of normal prolactin levels usually corrects these.

“If you have a patient where you are unable to restore prolactin levels to normal, there are other methods” to consider. Patients may end up using clomiphene, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropins, or even moving to in vitro fertilization in these cases, said Dr. Molitch.

Preferable to any of these, though, is achieving normal prolactin levels.

In patients who are hyperprolactinemic, “the major action is occurring at the hypothalamic level,” with decreases in pulsatile secretion of GnRH, said Dr. Molitch. Next, there are resultant decreases in gonadotropin secretion, which in turn interrupt the ovary’s normal physiology. “There’s also an interruption in positive estrogen feedback in this cycle,” he said.

“So what’s new in this area is kisspeptin,” Dr. Molitch said, adding that the peptide activates the G-protein coupled receptor GPR54, found in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Infusion of kisspeptin stimulates secretion of luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Conversely, mutations that inactivate GPR43 result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, while activating mutations are associated with centrally caused precocious puberty (Biol Reprod. 2011 Oct;85[4]:650-60; Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 Oct 22;346[1-2]:29-3).

From this and other work, endocrinologists now know that kisspeptin is “very likely involved in puberty initiation and in response to fasting,” said Dr. Molitch. It’s now thought that high prolactin levels alter kisspeptin levels, “which then causes the further downstream effects,” said Dr. Molitch.

Dopamine agonists and pregnancy

Dopamine agonists are the primary therapies used for patients with prolactinomas and hyperprolactinemia. In patients seeking fertility, the dopamine agonist is usually continued just through the first few weeks of pregnancy, until the patient misses her first menstrual period, he said.

Establishing the menstrual interval is key to knowing when to stop the dopamine agonist, though. “We often use barrier contraceptives, so we can tell what the menstrual interval is – so we can tell when somebody’s missed her period,” Dr. Molitch explained.

“Most of the safety data on these drugs … are based on that relatively short period of exposure,” said Dr. Molitch. “As far as long-term use during pregnancy, only about 100 patients who took bromocriptine throughout pregnancy have been reported,” with two minor fetal anomalies reported from this series of patients, he said.

Though fewer than 20 cases have been reported of cabergoline being continued throughout a pregnancy, “there have not been any problems with that,” said Dr. Molitch.

Overall, over 6,000 pregnancies with bromocriptine exposure, as well as over 1,000 with cabergoline, have now been reported.

Dr. Molitch summarized the aggregate safety data for each dopamine agonist: “When we look at the adverse outcomes that occurred with either of these drugs, as far as spontaneous abortions or terminations, premature deliveries, multiple births, and, of course, the most important thing here being major malformations … in neither drug is there an increase in these adverse outcomes” (J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Jan;41[1]:129-41).

“In my own mind now, I think that the number of cases with cabergoline now is quite sufficient to justify the safety of its use during pregnancy,” Dr. Molitch said. “However, this is sort of an individualized decision between you – the clinician – as well as your patient to make”: whether to trust the 1,000-case–strong data for cabergoline. “I no longer change patients from cabergoline to bromocriptine because of safety concerns. I think that cabergoline is perfectly safe,” he added.

What if the tumor grows in pregnancy?

During pregnancy, high estrogen levels from the placenta can stimulate prolactinoma growth, and the dopamine agonist’s inhibitory effect is gone once that medication’s been stopped. This means that “We have both a ‘push’ and a decrease in the ‘pull’ here, so you may have tumor enlargement,” said Dr. Molitch.

The risk for tumor enlargement in microadenomas is about 2.4%, and ranges to about 16% for enlargement of macroadenomas during pregnancy. For macroadenomas, “you might consider a prepregnancy debulking of the tumor,” Dr. Molitch said.

It’s reasonable to stop a dopamine agonist once pregnancy’s been established in a patient with a prolactinoma, and “follow the patient symptomatically every few months,” letting suspicious new symptoms like visual changes or headaches be the prompt for visual field exam and magnetic resonance imaging without contrast, said Dr. Molitch.

Though it’s not FDA approved, consideration can be given to continuing a dopamine agonist in a patient with a large prepregnancy adenoma throughout pregnancy – and if the tumor is enlarging significantly, the dopamine agonist should be restarted if it’s been withheld, said Dr. Molitch. Finally, surgery is the option if an enlarging tumor doesn’t respond to a dopamine agonist, unless the pregnancy is far enough along that delivery is a safe option.

“It’s important to actually document that there’s tumor enlargement, because if you’re going to do something like restarting a drug or even surgery, you really want to make sure that it’s the enlarging tumor that’s causing the problem,” said Dr. Molitch.

Postpartum prolactinoma considerations

Postpartum, even though prolactin secretion is upped by nursing, “there are no data to show that lactation stimulates tumor growth,” said Dr. Molitch. “I don’t see that there’s any problem with somebody nursing if they choose to do so.” However, “You certainly cannot restart the dopamine agonist, because that will lower prolactin levels and prevent that person from being able to nurse,” he said.

For reasons that are not clear, prolactin levels often drop post partum. Accordingly, it’s a reasonable approach in a nursing mother with mildly elevated prolactin levels to wait until nursing is done to see if menses resume spontaneously before restarting the dopamine agonist, said Dr. Molitch.

Dr. Molitch reported receiving fees and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed that his spouse holds stock in Amgen.

SOURCE: Molitch M ENDO 2018. Abstract M02-2.

CHICAGO – Management of fertility and reproduction for women with prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors is a balancing act, often in the absence of robust data to support clinical decision making. So judgment, communication, and paying attention to the patient become paramount considerations, said endocrinologist Mark Molitch, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The first step: restoring fertility

“Remember that our patients that have hyperprolactinemia are generally infertile,” said Dr. Molitch, Martha Leland Sherwin Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. “You really need to restore prolactin levels to close to normal, or normal, to allow ovulation to occur,” he said.

Dr. Molitch noted that up to 94% of women with hyperprolactinemia will initially have anovulation, amenorrhea, and infertility, but restoration of normal prolactin levels usually corrects these.

“If you have a patient where you are unable to restore prolactin levels to normal, there are other methods” to consider. Patients may end up using clomiphene, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropins, or even moving to in vitro fertilization in these cases, said Dr. Molitch.

Preferable to any of these, though, is achieving normal prolactin levels.

In patients who are hyperprolactinemic, “the major action is occurring at the hypothalamic level,” with decreases in pulsatile secretion of GnRH, said Dr. Molitch. Next, there are resultant decreases in gonadotropin secretion, which in turn interrupt the ovary’s normal physiology. “There’s also an interruption in positive estrogen feedback in this cycle,” he said.

“So what’s new in this area is kisspeptin,” Dr. Molitch said, adding that the peptide activates the G-protein coupled receptor GPR54, found in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Infusion of kisspeptin stimulates secretion of luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Conversely, mutations that inactivate GPR43 result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, while activating mutations are associated with centrally caused precocious puberty (Biol Reprod. 2011 Oct;85[4]:650-60; Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 Oct 22;346[1-2]:29-3).

From this and other work, endocrinologists now know that kisspeptin is “very likely involved in puberty initiation and in response to fasting,” said Dr. Molitch. It’s now thought that high prolactin levels alter kisspeptin levels, “which then causes the further downstream effects,” said Dr. Molitch.

Dopamine agonists and pregnancy

Dopamine agonists are the primary therapies used for patients with prolactinomas and hyperprolactinemia. In patients seeking fertility, the dopamine agonist is usually continued just through the first few weeks of pregnancy, until the patient misses her first menstrual period, he said.

Establishing the menstrual interval is key to knowing when to stop the dopamine agonist, though. “We often use barrier contraceptives, so we can tell what the menstrual interval is – so we can tell when somebody’s missed her period,” Dr. Molitch explained.

“Most of the safety data on these drugs … are based on that relatively short period of exposure,” said Dr. Molitch. “As far as long-term use during pregnancy, only about 100 patients who took bromocriptine throughout pregnancy have been reported,” with two minor fetal anomalies reported from this series of patients, he said.

Though fewer than 20 cases have been reported of cabergoline being continued throughout a pregnancy, “there have not been any problems with that,” said Dr. Molitch.

Overall, over 6,000 pregnancies with bromocriptine exposure, as well as over 1,000 with cabergoline, have now been reported.

Dr. Molitch summarized the aggregate safety data for each dopamine agonist: “When we look at the adverse outcomes that occurred with either of these drugs, as far as spontaneous abortions or terminations, premature deliveries, multiple births, and, of course, the most important thing here being major malformations … in neither drug is there an increase in these adverse outcomes” (J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Jan;41[1]:129-41).

“In my own mind now, I think that the number of cases with cabergoline now is quite sufficient to justify the safety of its use during pregnancy,” Dr. Molitch said. “However, this is sort of an individualized decision between you – the clinician – as well as your patient to make”: whether to trust the 1,000-case–strong data for cabergoline. “I no longer change patients from cabergoline to bromocriptine because of safety concerns. I think that cabergoline is perfectly safe,” he added.

What if the tumor grows in pregnancy?

During pregnancy, high estrogen levels from the placenta can stimulate prolactinoma growth, and the dopamine agonist’s inhibitory effect is gone once that medication’s been stopped. This means that “We have both a ‘push’ and a decrease in the ‘pull’ here, so you may have tumor enlargement,” said Dr. Molitch.

The risk for tumor enlargement in microadenomas is about 2.4%, and ranges to about 16% for enlargement of macroadenomas during pregnancy. For macroadenomas, “you might consider a prepregnancy debulking of the tumor,” Dr. Molitch said.

It’s reasonable to stop a dopamine agonist once pregnancy’s been established in a patient with a prolactinoma, and “follow the patient symptomatically every few months,” letting suspicious new symptoms like visual changes or headaches be the prompt for visual field exam and magnetic resonance imaging without contrast, said Dr. Molitch.

Though it’s not FDA approved, consideration can be given to continuing a dopamine agonist in a patient with a large prepregnancy adenoma throughout pregnancy – and if the tumor is enlarging significantly, the dopamine agonist should be restarted if it’s been withheld, said Dr. Molitch. Finally, surgery is the option if an enlarging tumor doesn’t respond to a dopamine agonist, unless the pregnancy is far enough along that delivery is a safe option.

“It’s important to actually document that there’s tumor enlargement, because if you’re going to do something like restarting a drug or even surgery, you really want to make sure that it’s the enlarging tumor that’s causing the problem,” said Dr. Molitch.

Postpartum prolactinoma considerations

Postpartum, even though prolactin secretion is upped by nursing, “there are no data to show that lactation stimulates tumor growth,” said Dr. Molitch. “I don’t see that there’s any problem with somebody nursing if they choose to do so.” However, “You certainly cannot restart the dopamine agonist, because that will lower prolactin levels and prevent that person from being able to nurse,” he said.

For reasons that are not clear, prolactin levels often drop post partum. Accordingly, it’s a reasonable approach in a nursing mother with mildly elevated prolactin levels to wait until nursing is done to see if menses resume spontaneously before restarting the dopamine agonist, said Dr. Molitch.

Dr. Molitch reported receiving fees and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed that his spouse holds stock in Amgen.

SOURCE: Molitch M ENDO 2018. Abstract M02-2.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2018

Oncofertility in women: Time for a national solution

Fertility preservation and sexual health are main concerns in reproductive-age cancer survivors. Approximately 1% of cancer survivors are younger than age 20 and up to 10% are estimated to be younger than age 45.1 For many of these survivors, a cancer diagnosis may have occurred prior to their completion of childbearing.

Infertility or premature ovarian failure has been reported in 40% to 80% of cancer survivors due to chemotoxicity-induced accelerated loss of oocytes.2 Most gonadotoxic chemotherapeutic agents cause DNA double-strand breaks that cannot be adequately repaired, eventually leading to apoptotic cell death.3 Therefore, any chemotherapeutic agent that induces apoptotic death will cause irreversible depletion of ovarian reserve, since primordial follicles cannot be regenerated.

Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, have been shown to be most cytotoxic, and young cancer survivors who have received a combination of alkylating agents and abdominopelvic radiation—such as those with Hodgkin’s lymphoma—are at higher risk. Other poor prognostic factors for fertility include a hypothalamic-pituitary radiation dose greater than 30 Gy, an ovarian-uterine radiation dose greater than 5 Gy, summed alkylating agent dose score of 3 to 4 for each agent, and treatment with lomustine or cyclophosphamide.4

In general, a woman’s age (which reflects her existing ovarian reserve), type of therapeutic agents used, and duration of therapy impact the posttreatment viability of ovarian function. Despite conflicting information in published literature, medical suppression by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists is not effective.

Fertility preservation options in the United States include egg, embryo, and ovarian tissue banking and ovarian transposition and ovarian transplantation.5

Oncofertility: Maximizing reproductive potential in cancer patients

In 2006, Dr. Teresa Woodruff of the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University coined the term oncofertility. Oncofertility is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “a field concerned with minimizing the negative effects of cancer treatment (such as chemotherapy or radiation) on the reproductive system and fertility and with assisting individuals with reproductive impairments resulting from cancer therapy.”

Recognition of the many barriers to fertility preservation led to the establishment of the Oncofertility Consortium, a multi-institution group that includes Northwestern University, the University of California San Diego, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Missouri, and Oregon Health and Science University. The Consortium facilitates collaboration between biomedical and social scientists, pediatricians, oncologists, reproductive specialists, educators, social workers, and medical ethicists in an effort to assess the impact of cancer and its treatment on future fertility and reproductive health and to advance knowledge. The Consortium also is a valuable information resource on fertility preservation options for patients, their families, and providers.6

The oncofertility program at Northwestern University was established as an interdisciplinary team of oncologists, reproductive health specialists, supportive care staff, and researchers. Reproductive-age women with cancer can participate in a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach to the management of their malignancy with strict planning and coordination of care, if they wish to maintain fertility following treatment. Many hospitals and health care systems have established such programs, recognizing that the need to preserve fertility potential is an essential part of the comprehensive care of a reproductive-age woman undergoing treatment. When a cancer diagnosis is made, prompt referral to a fertility specialist and a multidisciplinary approach to treatment planning are critical to mitigate the negative impact of cancer treatment on fertility and the potential risk of ovarian damage.

Barriers to oncofertility care

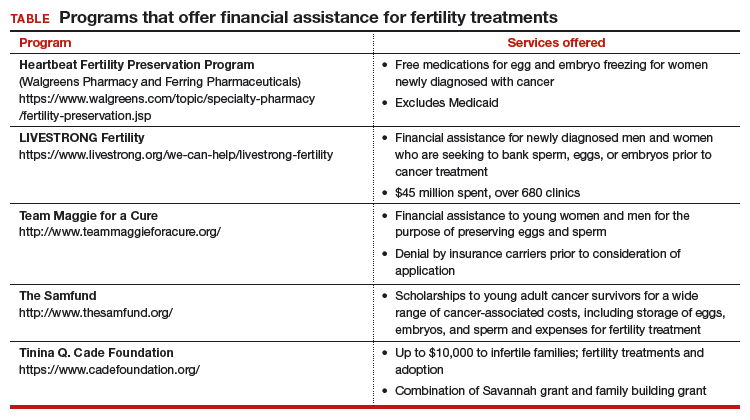

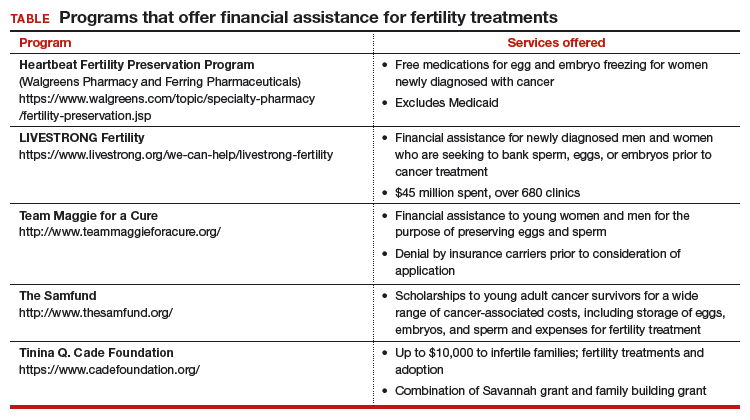

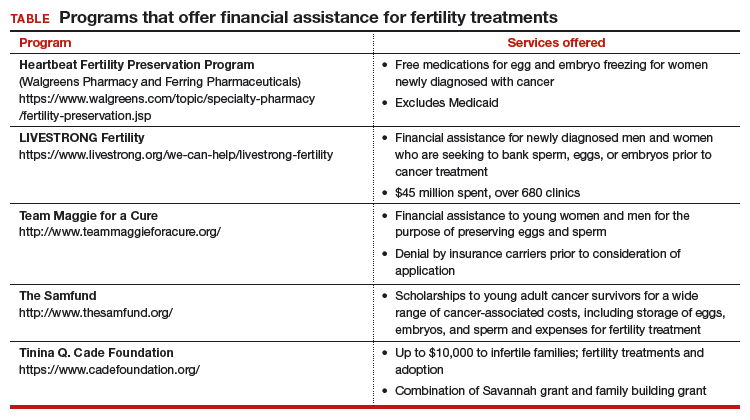

Timely referral to fertility specialists may not occur because of lack of a formal oncofertility program or unawareness of available therapeutic options. In some instances, delaying cancer treatment is not feasible. Additionally, many other factors must be considered regarding societal, ethical, and legal implications. But most concerning is the lack of consistent and timely access to funding for fertility preservation by third-party payers. Although some funding options exist, these require both patient awareness and effort to pursue (TABLE).

National legislation does not include provision for this aspect of women’s health, and as of 2017 insurance coverage for oncofertility was mandated only in 2 states, Connecticut and Rhode Island. In New York, Governor Cuomo directed the Department of Financial Services to study how to ensure that New Yorkers can have access to oncofertility services, and legislation is pending in the New York state legislature.7

Recently, Cardozo and colleagues reported that 15 states currently require insurers to provide some form of infertility coverage.8 By contrast, RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, reports information on fertility coverage and the status of bills by state on its website (https://resolve.org). For example, in California, Hawaii, Illinois, and Maryland, bills have been proposed and are in various stages of assessment. Connecticut and Rhode Island mandate coverage. As always, details matter. Cardozo and colleagues eloquently point out limitations of coverage based on age and definition of infertility, and potential financial impact.8

An actuarial consulting company called NovaRest prepared a document for the state of Maryland in which the estimated expected number of “cases” would amount to 1,327 women and 731 men aged 10 to 44.9 These individuals might require oncofertility services. NovaRest estimated that clients could experience up to a 0.4% increase in insurance premiums annually if this program was offered. Similar estimates are reported by other states. In Kentucky and Mississippi, such bills “died in committee.” The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) is actively lobbying with partners, including the Coalition to Protect Parenthood After Cancer, to advocate for preservation of fertility.

Drs. Ursillo and Chalas bring attention to an important issue. As technology advances, so do treatment and coverage needs, and so does the need for ongoing physician and patient education.

In 1990, the US Congress passed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act to help ensure that low-income women would have access to screening for these diseases. It took 10 years before Congress passed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act so that women detected with breast or cervical cancer could be treated. A curious delay, I know.

Today, we seem to be in a similar situation regarding fertility preservation. Cancer treatment is advanced, coverage is available. Fertility-related treatment is now possible, but coverage is nearly absent.

In my research for this commentary, I learned (a little) about ovarian transplantation and translocation. Even that little was enough to see that we live in an amazing new world. Drs. Ursillo and Chalas put out an important call for physicians to learn, to teach their patients, and, especially, to consider fertility preservation options before (when possible) initiating cancer treatment. It also is imperative to consider fertility preservation in young patients who have not yet reached their fertile years. Cancer treatment begun before fertility preservation may mean future irreversible infertility.

They also call for insurers and public programs to cover fertility and fertility preservation as “essential in the comprehensive care” of cancer patients. To the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), that means a federal policy that would ensure public and private coverage for every woman, no matter where she lives, her income level, or her employer.

In many ways, this is a difficult time in public policy related to women’s health. With ACOG’s leadership, our physician colleague organizations and patient advocacy groups are fighting hard to retain women’s health protections already in law. At this moment, opportunities are rare for consideration of expansion. But a national solution is the right solution.

Until we reach that goal, we support state efforts to require private health insurers to cover fertility preservation. As Drs. Ursillo and Chalas point out, only 2 states require private insurers to cover fertility preservation treatment. State-by-state efforts are notoriously difficult, unique, and inequitable to patients. Patients in some states simply are luckier than patients in other states. That is not how to solve a health care problem.

As is often the case, employers—in this case big, cutting-edge companies—are leading the way. Recently, an article in the Wall Street Journal (February 7, 2018) described companies that offer fertility treatment coverage to attract potential employees, such as Pinterest, American Express, and Foursquare. This is an important first step that we can build upon, ensuring that coverage includes fertility protection and then leveraging employer coverage experience to influence coverage more broadly.

Big employers may help us find our way, showing just how little inclusion of this coverage relates to premiums; by some estimates, only 0.4%. That is a small investment for enormous results in a patient’s future.

My takeaways from this thoughtful editorial:

- Physicians should educate themselves about fertility preservation options.

- Physicians should educate their patients about the same.

- Physicians should consider these options before initiating treatment.

- We all should advocate for our patients, in this case, national, state, and employer coverage of fertility treatment, including preservation.

Ms. DiVenere is Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Washington, DC. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

We need a joint effort

Most recent statistics support an increase in cancer survivorship over the past decade.10 This trend likely will continue thanks to greater application of screening and more effective therapies. The use of targeted therapy is on the rise, but it is not applicable for most malignancies at this time, and its effect on fertility is largely unknown. Millennials now constitute the largest group in our population, and delaying childbearing to the late second and third decades is now common. These medical and societal trends will result in more women being interested in fertility preservation.

The ASRM and other organizations are lobbying to support legislation to mandate coverage for oncofertility on a state-by-state basis. Major limitations of this approach include inability to address oncofertility unless such legislation already has been introduced, the lack of impact on individuals residing in other states, and inefficiency of regional lobbying. In addition, those who are self-insured are not subject to state mandates and therefore will not benefit from such coverage mandates. Finally, nuances in the definition of infertility or age-based restrictions may limit access to these services even when mandated.

A cancer diagnosis is always potentially life-threatening and is often perceived as devastating on a personal level. In women of reproductive age, it represents a threat to their future ability to bear children and to ovarian function. These women deserve to have the opportunity to consider all options to maintain fertility, and they should not struggle with difficult financial choices at a time of such extreme stress.

To address this important issue, a 3-pronged approach is called for:

- All providers caring for cancer patients of reproductive age must be aware of fertility preservation and inform patients of these options.

- Cancer survivors and their caretakers must assist in legislative advocacy efforts.

- Nationally mandated coverage must be sought.

A joint effort by the medical community and women advocates is critical to bring attention to this issue in a national forum and provide a solution that benefits all women.

Acknowledgement

The authors express gratitude to Erin Kramer, Government Affairs, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and Christa Christakis, Executive Director, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists District II, for their assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Woodruff TK. The Oncofertility Consortium—addressing fertility in young people with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(8):466–475.

- Pereira N, Schattman GL. Fertility preservation and sexual health after cancer therapy. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):643–651.

- Soleimani R, Heytens E, Darzynkiewicz Z, Oktay K. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced human ovarian aging: double strand DNA breaks and microvascular compromise. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(8):782–793.

- Green DM, Nolan VG, Kawashima T, et al. Decreased fertility among female childhood cancer survivors who received 22-27 Gr hypothalamic/pituitary irradiation: a report from the Child Cancer Survivor Study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(6):1922–1927.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update [published online April 5, 2018]. J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.1914.

- Woodruff TK, Snyder KA. Oncofertility: fertility preservation for cancer survivors. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2007.

- New York State Council on Women and Girls. Report on the status of New York women and girls: 2018 outlook. https://www.ny.gov/sites/ny.gov/files/atoms/files/StatusNYWomenGirls2018Outlook.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Cardozo ER, Huber WJ, Stuckey AR, Alvero RJ. Mandating coverage for fertility preservation—a step in the right direction. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1607–1609.

- NovaRest Actuarial Consulting. Annual mandate report: coverage for iatrogenic infertility. http://mhcc.maryland.gov/mhcc/pages/plr/plr/documents/NovaRest_Evaluation_of_%20Proposed_Mandated_Services_Iatrogenic_Infertility_FINAL_11-20-17.pdf. Published November 16, 2017. Accessed April 13, 2018.

- Siegel R, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30.

Fertility preservation and sexual health are main concerns in reproductive-age cancer survivors. Approximately 1% of cancer survivors are younger than age 20 and up to 10% are estimated to be younger than age 45.1 For many of these survivors, a cancer diagnosis may have occurred prior to their completion of childbearing.

Infertility or premature ovarian failure has been reported in 40% to 80% of cancer survivors due to chemotoxicity-induced accelerated loss of oocytes.2 Most gonadotoxic chemotherapeutic agents cause DNA double-strand breaks that cannot be adequately repaired, eventually leading to apoptotic cell death.3 Therefore, any chemotherapeutic agent that induces apoptotic death will cause irreversible depletion of ovarian reserve, since primordial follicles cannot be regenerated.

Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, have been shown to be most cytotoxic, and young cancer survivors who have received a combination of alkylating agents and abdominopelvic radiation—such as those with Hodgkin’s lymphoma—are at higher risk. Other poor prognostic factors for fertility include a hypothalamic-pituitary radiation dose greater than 30 Gy, an ovarian-uterine radiation dose greater than 5 Gy, summed alkylating agent dose score of 3 to 4 for each agent, and treatment with lomustine or cyclophosphamide.4