User login

Neurologists need not discourage breastfeeding in women with MS

STOCKHOLM – Most neurologists are overly conservative when it comes to advising women with multiple sclerosis (MS) about breastfeeding, discouraging this broadly beneficial practice in favor of early resumption of treatment post pregnancy, Kerstin Hellwig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“We should change our behavior, and I predict we will change it so that more women are breastfeeding while under MS medication within the next couple years. ,” said Dr. Hellwig, senior consultant and MS specialist in the department of neurology at St. Josef Hospital/Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany.

She was a coauthor of a groundbreaking 2012 meta-analysis that concluded that breastfeeding by MS patients is not harmful (J Neurol. 2012 Oct;259[10]:2246-8), a finding since confirmed in multiple additional studies.

“Women with MS who want to breastfeed should be supported in doing so,” Dr. Hellwig said.

In this regard, many neurologists are out of step with their colleagues in rheumatology and gastroenterology, who commonly endorse breastfeeding by their patients while on monoclonal antibodies for other autoimmune diseases, according to Dr. Hellwig.

It is important to recognize that most women of reproductive age with MS have milder forms of the disease, she said. They can safely breastfeed without being on any MS medications at all for the duration.

For women who want to breastfeed and have more-active disease where early treatment resumption is warranted, the key is to select a breastfeeding-compatible medication. The main determinant of whether a drug will enter the mother’s breast milk is the size of the drug molecule, with large molecules being unlikely to make their way into breast milk in anything approaching clinically meaningful amounts. The injectable first-line disease-modifying drugs are good options: For example, interferon-beta is a very large molecule which has been detected in breast milk at 0.0006% of the relative infant dose. That’s reassuring, Dr. Hellwig said, since anything less than a relative infant dose of 10% is generally considered to be safe for a baby. And while glatiramer acetate, another injectable, has not been tested, it is metabolized so rapidly that it is unlikely to be detectable in breast milk, according to Dr. Hellwig.

Monoclonal antibodies are also compatible with breastfeeding. Rituximab has been detected in breast milk at 1/240th of the maternal serum level, and natalizumab at less than 1/200th. These are large molecules with a low likelihood of infant absorption, since they are probably destroyed in the child’s gastrointestinal tract. Ocrelizumab has not been studied in breast milk, but it is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody, as is rituximab, and so should likewise pose “exceedingly low risk,” Dr. Hellwig said.

At last year’s ECTRIMS conference, she presented reassuring 1-year follow-up data on a cohort of infants breastfed by mothers with MS while on interferon-beta. “We do not see any growth disturbances, any severe infections, hospitalizations, excess antibiotic use, or postponed reaching of developmental milestones in babies being breastfed under the injectables,” she said.

Dr. Hellwig has served on scientific advisory board for Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has received speaker honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, SanofiGenzyme, and Teva, and has received support for congress participation from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, and Merck.

STOCKHOLM – Most neurologists are overly conservative when it comes to advising women with multiple sclerosis (MS) about breastfeeding, discouraging this broadly beneficial practice in favor of early resumption of treatment post pregnancy, Kerstin Hellwig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“We should change our behavior, and I predict we will change it so that more women are breastfeeding while under MS medication within the next couple years. ,” said Dr. Hellwig, senior consultant and MS specialist in the department of neurology at St. Josef Hospital/Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany.

She was a coauthor of a groundbreaking 2012 meta-analysis that concluded that breastfeeding by MS patients is not harmful (J Neurol. 2012 Oct;259[10]:2246-8), a finding since confirmed in multiple additional studies.

“Women with MS who want to breastfeed should be supported in doing so,” Dr. Hellwig said.

In this regard, many neurologists are out of step with their colleagues in rheumatology and gastroenterology, who commonly endorse breastfeeding by their patients while on monoclonal antibodies for other autoimmune diseases, according to Dr. Hellwig.

It is important to recognize that most women of reproductive age with MS have milder forms of the disease, she said. They can safely breastfeed without being on any MS medications at all for the duration.

For women who want to breastfeed and have more-active disease where early treatment resumption is warranted, the key is to select a breastfeeding-compatible medication. The main determinant of whether a drug will enter the mother’s breast milk is the size of the drug molecule, with large molecules being unlikely to make their way into breast milk in anything approaching clinically meaningful amounts. The injectable first-line disease-modifying drugs are good options: For example, interferon-beta is a very large molecule which has been detected in breast milk at 0.0006% of the relative infant dose. That’s reassuring, Dr. Hellwig said, since anything less than a relative infant dose of 10% is generally considered to be safe for a baby. And while glatiramer acetate, another injectable, has not been tested, it is metabolized so rapidly that it is unlikely to be detectable in breast milk, according to Dr. Hellwig.

Monoclonal antibodies are also compatible with breastfeeding. Rituximab has been detected in breast milk at 1/240th of the maternal serum level, and natalizumab at less than 1/200th. These are large molecules with a low likelihood of infant absorption, since they are probably destroyed in the child’s gastrointestinal tract. Ocrelizumab has not been studied in breast milk, but it is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody, as is rituximab, and so should likewise pose “exceedingly low risk,” Dr. Hellwig said.

At last year’s ECTRIMS conference, she presented reassuring 1-year follow-up data on a cohort of infants breastfed by mothers with MS while on interferon-beta. “We do not see any growth disturbances, any severe infections, hospitalizations, excess antibiotic use, or postponed reaching of developmental milestones in babies being breastfed under the injectables,” she said.

Dr. Hellwig has served on scientific advisory board for Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has received speaker honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, SanofiGenzyme, and Teva, and has received support for congress participation from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, and Merck.

STOCKHOLM – Most neurologists are overly conservative when it comes to advising women with multiple sclerosis (MS) about breastfeeding, discouraging this broadly beneficial practice in favor of early resumption of treatment post pregnancy, Kerstin Hellwig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“We should change our behavior, and I predict we will change it so that more women are breastfeeding while under MS medication within the next couple years. ,” said Dr. Hellwig, senior consultant and MS specialist in the department of neurology at St. Josef Hospital/Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany.

She was a coauthor of a groundbreaking 2012 meta-analysis that concluded that breastfeeding by MS patients is not harmful (J Neurol. 2012 Oct;259[10]:2246-8), a finding since confirmed in multiple additional studies.

“Women with MS who want to breastfeed should be supported in doing so,” Dr. Hellwig said.

In this regard, many neurologists are out of step with their colleagues in rheumatology and gastroenterology, who commonly endorse breastfeeding by their patients while on monoclonal antibodies for other autoimmune diseases, according to Dr. Hellwig.

It is important to recognize that most women of reproductive age with MS have milder forms of the disease, she said. They can safely breastfeed without being on any MS medications at all for the duration.

For women who want to breastfeed and have more-active disease where early treatment resumption is warranted, the key is to select a breastfeeding-compatible medication. The main determinant of whether a drug will enter the mother’s breast milk is the size of the drug molecule, with large molecules being unlikely to make their way into breast milk in anything approaching clinically meaningful amounts. The injectable first-line disease-modifying drugs are good options: For example, interferon-beta is a very large molecule which has been detected in breast milk at 0.0006% of the relative infant dose. That’s reassuring, Dr. Hellwig said, since anything less than a relative infant dose of 10% is generally considered to be safe for a baby. And while glatiramer acetate, another injectable, has not been tested, it is metabolized so rapidly that it is unlikely to be detectable in breast milk, according to Dr. Hellwig.

Monoclonal antibodies are also compatible with breastfeeding. Rituximab has been detected in breast milk at 1/240th of the maternal serum level, and natalizumab at less than 1/200th. These are large molecules with a low likelihood of infant absorption, since they are probably destroyed in the child’s gastrointestinal tract. Ocrelizumab has not been studied in breast milk, but it is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody, as is rituximab, and so should likewise pose “exceedingly low risk,” Dr. Hellwig said.

At last year’s ECTRIMS conference, she presented reassuring 1-year follow-up data on a cohort of infants breastfed by mothers with MS while on interferon-beta. “We do not see any growth disturbances, any severe infections, hospitalizations, excess antibiotic use, or postponed reaching of developmental milestones in babies being breastfed under the injectables,” she said.

Dr. Hellwig has served on scientific advisory board for Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has received speaker honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, SanofiGenzyme, and Teva, and has received support for congress participation from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, and Merck.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ECTRIMS 2019

No decrease in preterm birth with n-3 fatty acid supplements

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: No decrease in preterm birth was seen with n-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy, compared with controls.

Major finding: Early preterm delivery occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

Study details: A multicenter, double-blind trial in 5,517 women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

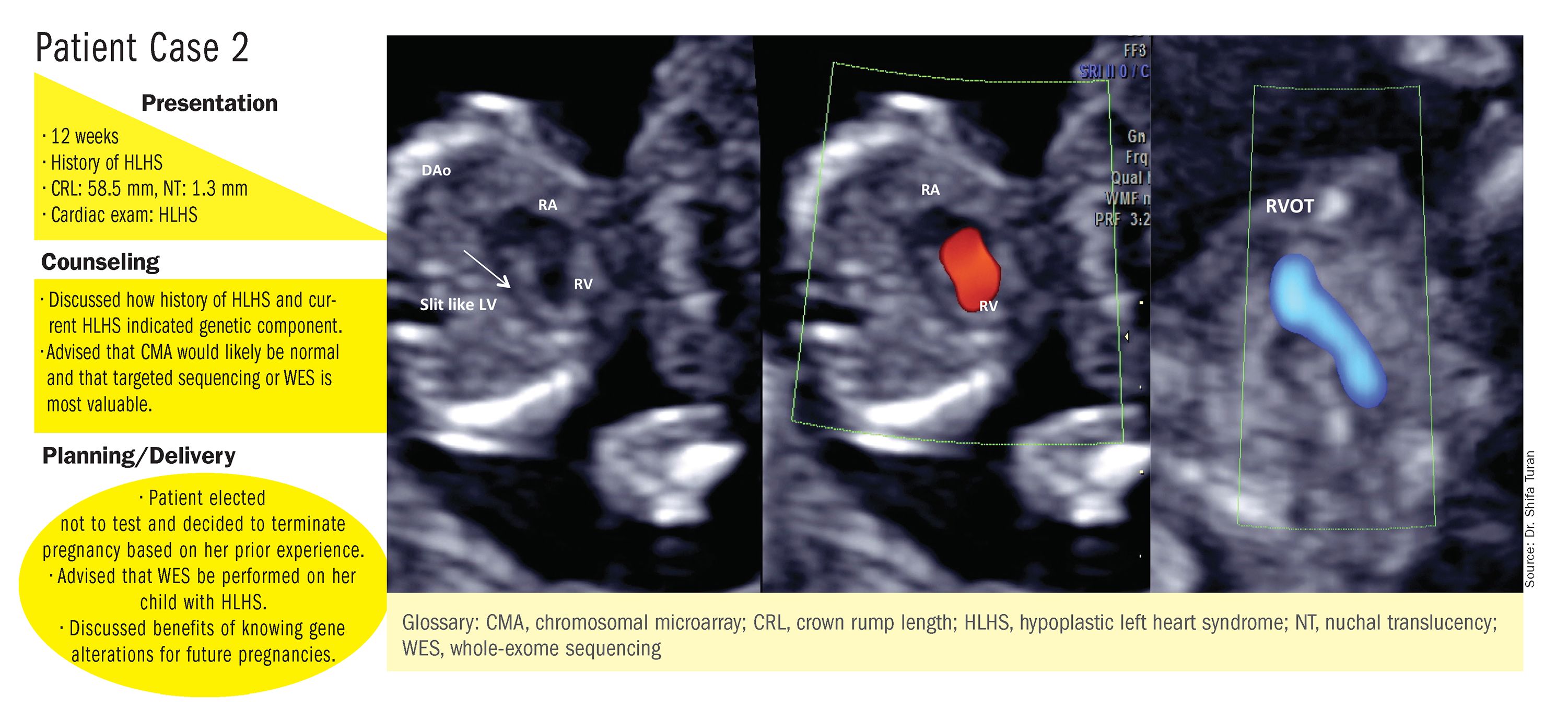

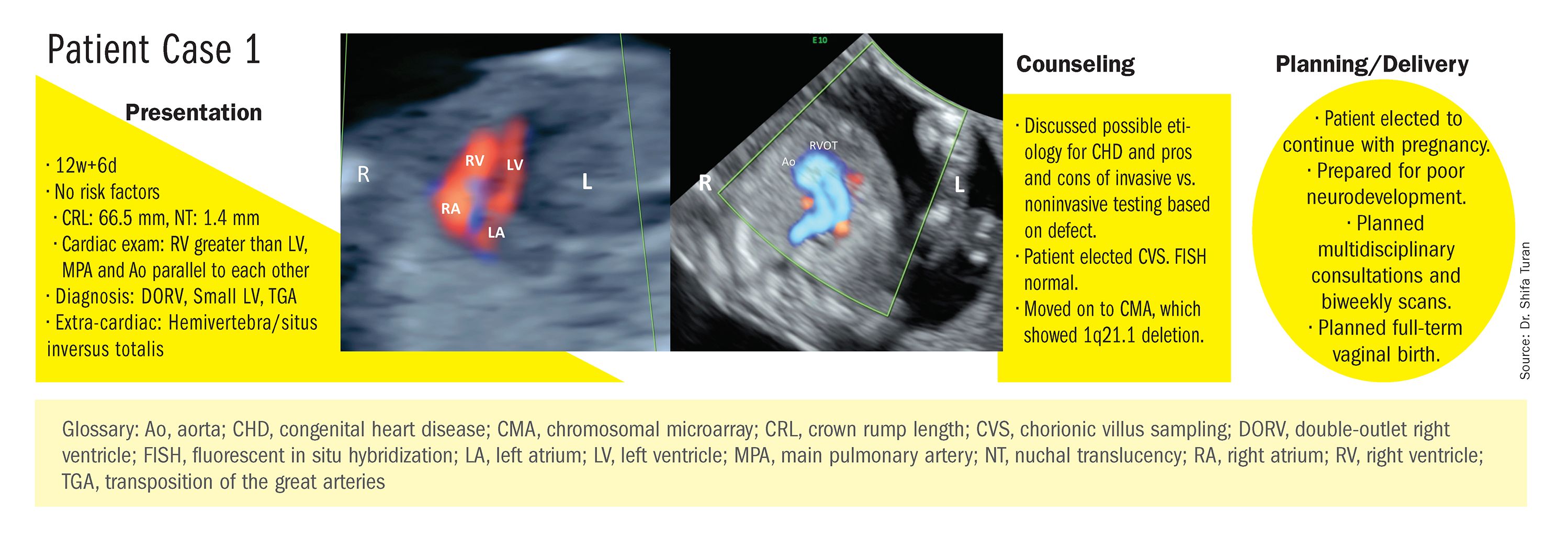

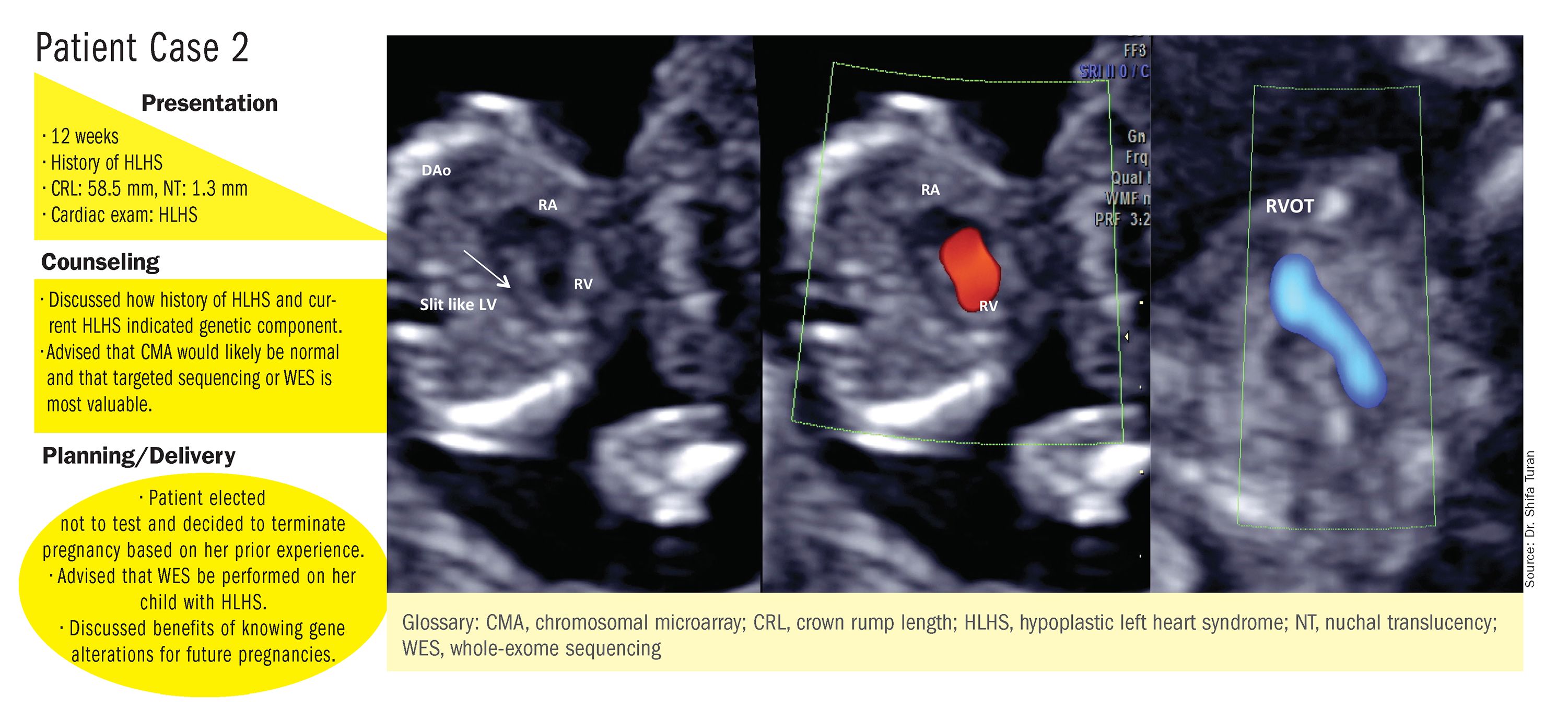

Use of genetic testing for congenital heart defect management

The average student in America learns that genes form the building blocks of what makes us human by the time they receive their high school diploma. Indeed, the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 paved the way for our genetic makeup, much like our medical history, to become a routine part of our health care. For example, our faculty at the University of Maryland School of Medicine discovered an important gene – CYP2C19 – which is involved in the metabolism of the antiplatelet medicine clopidogrel (Plavix). Although most people have this gene, some don’t. Therefore, when we manage a patient with coronary disease, we use a genetic screen to determine whether that patient has CYP2C19 and then modify therapy based on these results.

Our genes also have become commodities – from companies willing to analyze our genes to determine our racial and ethnic ancestry or propensity for certain diseases to those that can sequence the family dog’s genes.

Advances in genomics similarly have impacted ob.gyn. practice. Because of rapidly evolving gene analysis tools, we can now, for example, noninvasively test a developing fetus’s risk for chromosomal abnormalities and determine a baby’s sex by merely examining fetal DNA in a pregnant woman’s bloodstream. Although not diagnostic, these gene-based prenatal screening tests have reduced the need for unnecessary, costly, and highly invasive procedures for many of our patients.

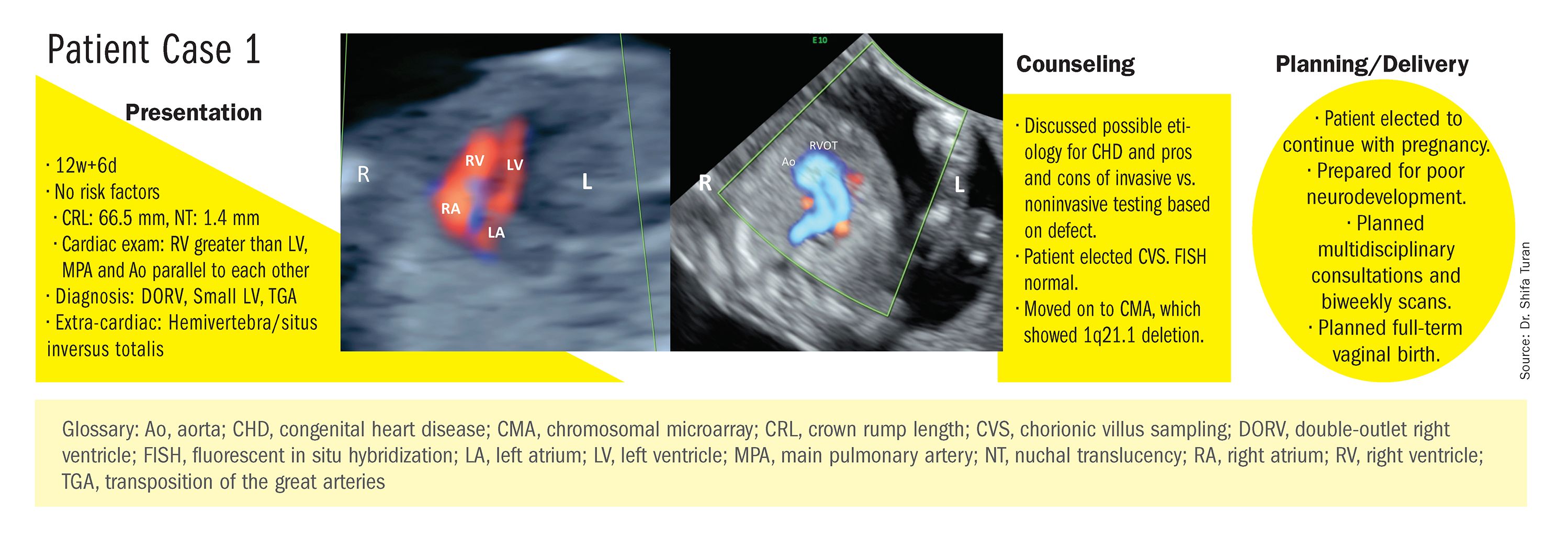

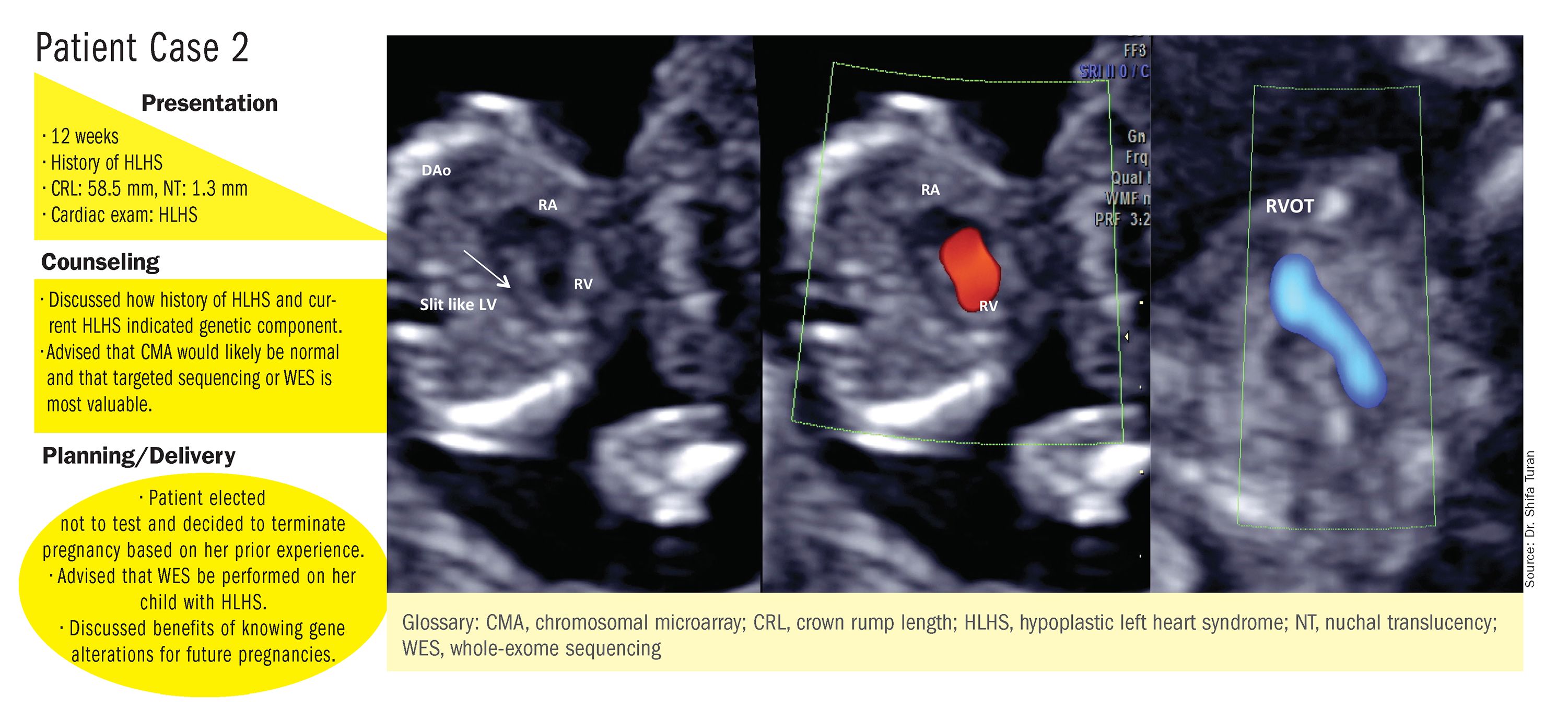

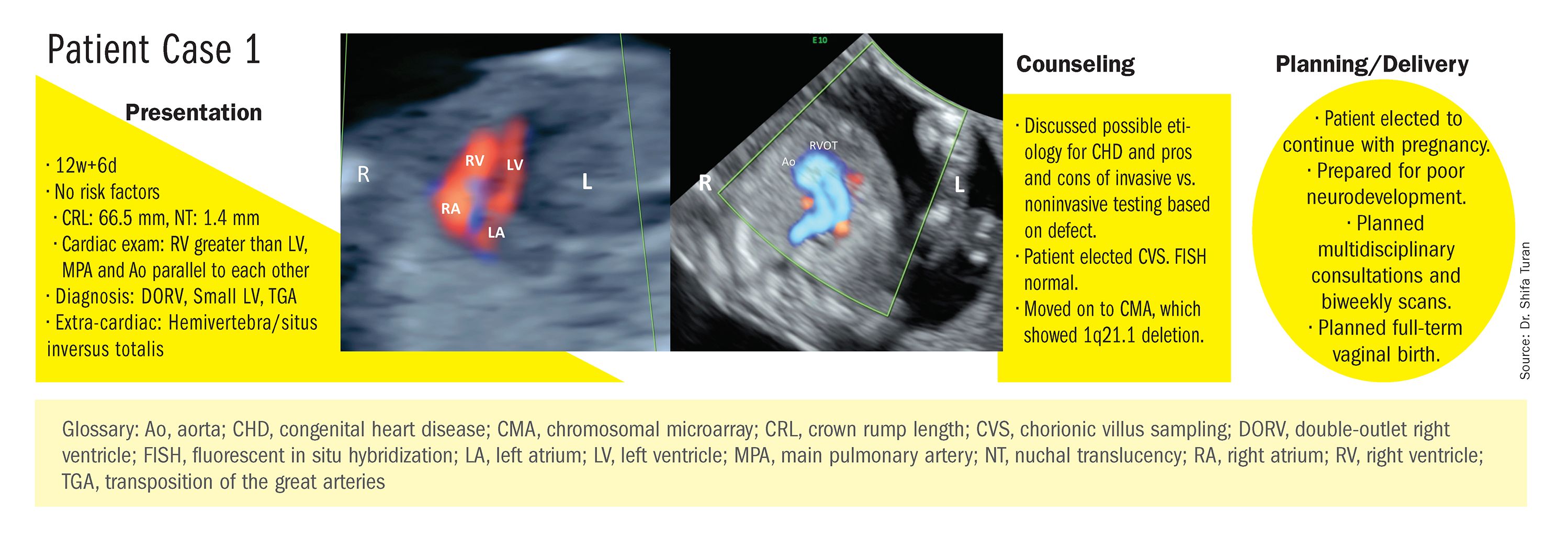

Importantly, our recognition that certain genes can confer a higher risk of disease has meant that performing a prenatal genetic evaluation can greatly inform the mother and her care team about potential problems her baby may have that may require additional management. For babies who have congenital heart defects, a genetic evaluation performed in addition to sonographic examination can provide ob.gyns. with crucial details to enhance pregnancy management and postnatal care decisions.

The importance of genetic testing and analysis in the detection, treatment, and prevention of congenital heart defects is the topic of part two of this two-part Master Class series authored by Shifa Turan, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. By using a combination of three- and four-dimensional ultrasound with gene assays, Dr. Turan and her colleagues can greatly enhance and personalize the care they deliver to their patients.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

The average student in America learns that genes form the building blocks of what makes us human by the time they receive their high school diploma. Indeed, the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 paved the way for our genetic makeup, much like our medical history, to become a routine part of our health care. For example, our faculty at the University of Maryland School of Medicine discovered an important gene – CYP2C19 – which is involved in the metabolism of the antiplatelet medicine clopidogrel (Plavix). Although most people have this gene, some don’t. Therefore, when we manage a patient with coronary disease, we use a genetic screen to determine whether that patient has CYP2C19 and then modify therapy based on these results.

Our genes also have become commodities – from companies willing to analyze our genes to determine our racial and ethnic ancestry or propensity for certain diseases to those that can sequence the family dog’s genes.

Advances in genomics similarly have impacted ob.gyn. practice. Because of rapidly evolving gene analysis tools, we can now, for example, noninvasively test a developing fetus’s risk for chromosomal abnormalities and determine a baby’s sex by merely examining fetal DNA in a pregnant woman’s bloodstream. Although not diagnostic, these gene-based prenatal screening tests have reduced the need for unnecessary, costly, and highly invasive procedures for many of our patients.

Importantly, our recognition that certain genes can confer a higher risk of disease has meant that performing a prenatal genetic evaluation can greatly inform the mother and her care team about potential problems her baby may have that may require additional management. For babies who have congenital heart defects, a genetic evaluation performed in addition to sonographic examination can provide ob.gyns. with crucial details to enhance pregnancy management and postnatal care decisions.

The importance of genetic testing and analysis in the detection, treatment, and prevention of congenital heart defects is the topic of part two of this two-part Master Class series authored by Shifa Turan, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. By using a combination of three- and four-dimensional ultrasound with gene assays, Dr. Turan and her colleagues can greatly enhance and personalize the care they deliver to their patients.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

The average student in America learns that genes form the building blocks of what makes us human by the time they receive their high school diploma. Indeed, the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 paved the way for our genetic makeup, much like our medical history, to become a routine part of our health care. For example, our faculty at the University of Maryland School of Medicine discovered an important gene – CYP2C19 – which is involved in the metabolism of the antiplatelet medicine clopidogrel (Plavix). Although most people have this gene, some don’t. Therefore, when we manage a patient with coronary disease, we use a genetic screen to determine whether that patient has CYP2C19 and then modify therapy based on these results.

Our genes also have become commodities – from companies willing to analyze our genes to determine our racial and ethnic ancestry or propensity for certain diseases to those that can sequence the family dog’s genes.

Advances in genomics similarly have impacted ob.gyn. practice. Because of rapidly evolving gene analysis tools, we can now, for example, noninvasively test a developing fetus’s risk for chromosomal abnormalities and determine a baby’s sex by merely examining fetal DNA in a pregnant woman’s bloodstream. Although not diagnostic, these gene-based prenatal screening tests have reduced the need for unnecessary, costly, and highly invasive procedures for many of our patients.

Importantly, our recognition that certain genes can confer a higher risk of disease has meant that performing a prenatal genetic evaluation can greatly inform the mother and her care team about potential problems her baby may have that may require additional management. For babies who have congenital heart defects, a genetic evaluation performed in addition to sonographic examination can provide ob.gyns. with crucial details to enhance pregnancy management and postnatal care decisions.

The importance of genetic testing and analysis in the detection, treatment, and prevention of congenital heart defects is the topic of part two of this two-part Master Class series authored by Shifa Turan, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. By using a combination of three- and four-dimensional ultrasound with gene assays, Dr. Turan and her colleagues can greatly enhance and personalize the care they deliver to their patients.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

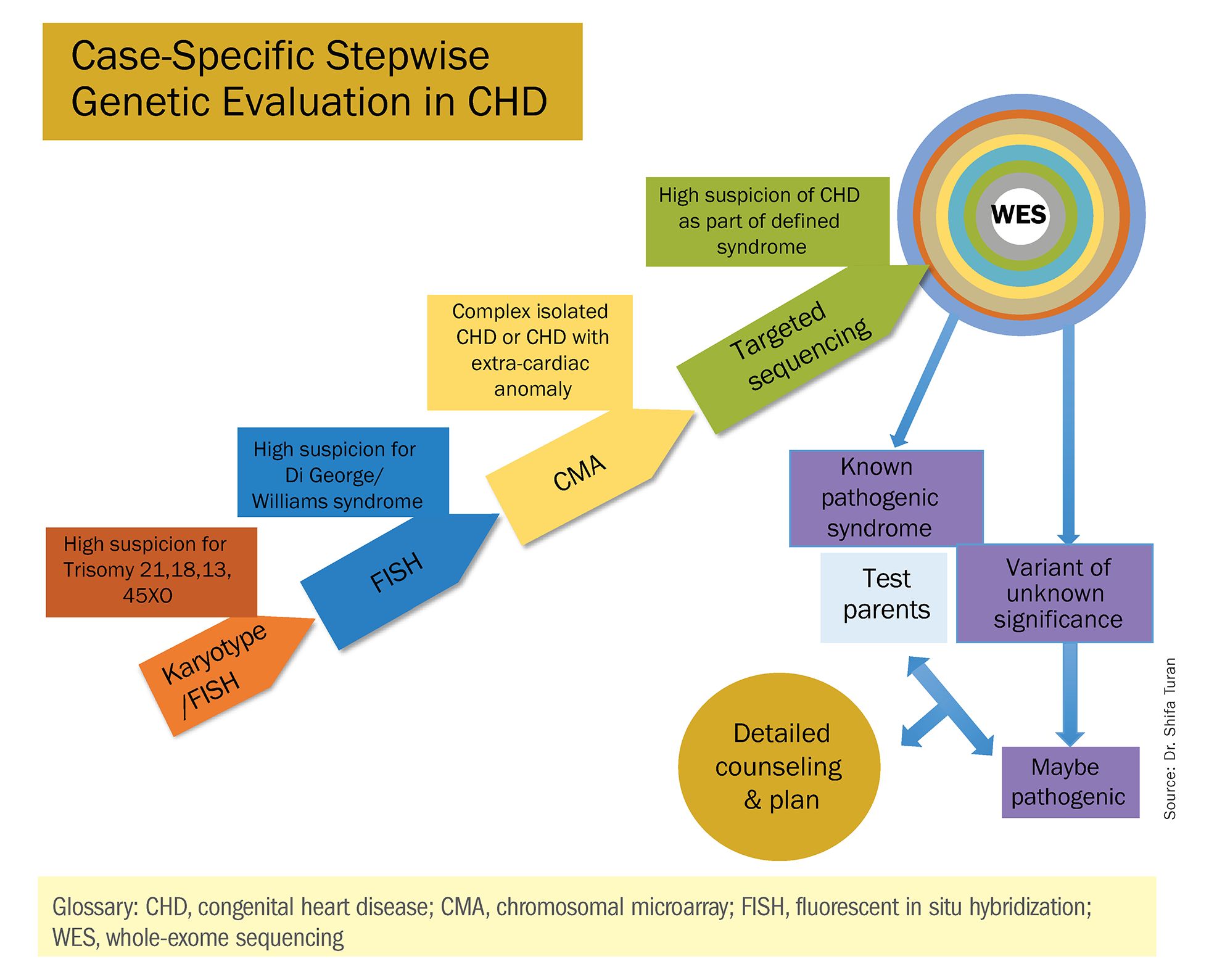

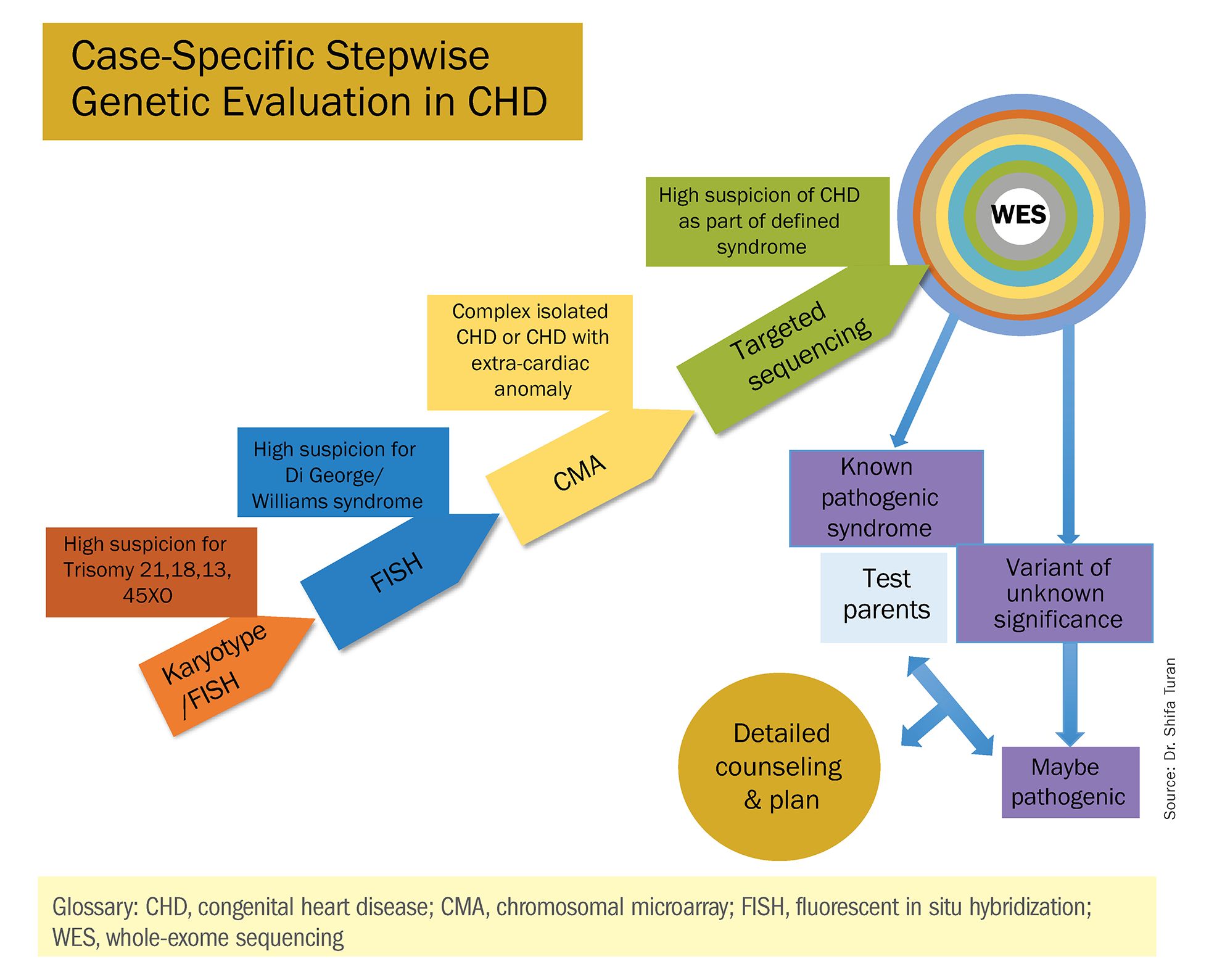

Genetic assessment for CHD: Case-specific, stepwise

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are etiologically heterogeneous, but in recent years it has become clear that genetics plays a larger role in the development of CHDs than was previously thought. Research has been shifting from a focus on risk – estimating the magnitude of increased risk, for instance, based on maternal or familial risk factors – to a focus on the etiology of cardiac defects.

In practice, advances in genetic testing technologies have made the underlying causes of CHDs increasingly detectable. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) – technology that detects significantly more and smaller changes in the amount of chromosomal material than traditional karyotype – has been proven to increase the diagnostic yield in cases of isolated CHDs and CHDs with extracardiac anomalies. Targeted next-generation sequencing also is now available as an additional approach in selective cases, and a clinically viable option for whole-exome sequencing is fast approaching.

For researchers, genetic evaluation carries the potential to unravel remaining mysteries about underlying causes of CHDs – to provide pathological insights and identify potential therapeutic targets. Currently, about 6 % of the total pie of presumed genetic determinants of CHDs is attributed to chromosomal anomalies, 10% to copy number variants, and 12% to single-gene defects. The remaining 72% of etiology, approximately, is undetermined.

As Helen Taussig, MD, (known as the founder of pediatric cardiology) once said, common cardiac malformations occurring in otherwise “normal” individuals “must be genetic in origin.”1 Greater use of genetic testing – and in particular, of whole-exome sequencing – will drive down this “undetermined” piece of the genetics pie.

For clinicians and patients, prenatal genetic evaluation can inform clinical management, guiding decisions on the mode, timing, and location of delivery. Genetic assessments help guide the neonatal health care team in taking optimal care of the infant, and the surgeon in preparing for neonatal surgeries and postsurgical complications.

In a recent analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database, prenatal diagnosis was associated with a lower overall prevalence of major preoperative risk factors for cardiac surgery.2 Surgical outcomes themselves also have been shown to be better after the prenatal diagnosis of complex CHDs, mainly because of improvements in perioperative care.3

When genetic etiology is elucidated, the cardiologist also is better able to counsel patients about anticipated challenges – such as the propensity, with certain genetic variants of CHD, to develop neurodevelopmental delays or other cardiac complications – and to target patient follow-up. Patients also can make informed decisions about termination or continuation of a current pregnancy and about family planning in the future.

Fortunately, advances in genetics technology have paralleled technological advancements in ultrasound. As I discussed in part one of this two-part Master Class series, it is now possible to detect many major CHDs well before 16 weeks’ gestation. Checking the structure of the fetal heart at the first-trimester screening and sonography (11-14 weeks of gestation) offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment, counseling, and planning when anomalies are detected.

A personalized approach

There has been growing interest in recent years in CMA for the prenatal genetic workup of CHDs. Microarray targets chromosomal regions at a much higher resolution than traditional karyotype. Traditional karyotype assesses both changes in chromosome number as well as more subtle structural changes such as chromosomal deletions and duplications. CMA finds what traditional karyotype identifies, but in addition, it identifies much smaller, clinically relevant chromosomal deletions and duplications that are not detected by karyotype performed with or without fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH). FISH uses DNA probes that carry fluorescent tags to detect chromosomal DNA.

At our center, we studied the prenatal genetic test results of 145 fetuses diagnosed with CHDs. Each case involved FISH for aneuploidy/karyotype, followed by CMA in cases of a negative karyotype result. CMA increased the diagnostic yield in cases of CHD by 19.8% overall – 17.4% in cases of isolated CHD and 24.5% in cases of CHD plus extracardiac anomalies.4

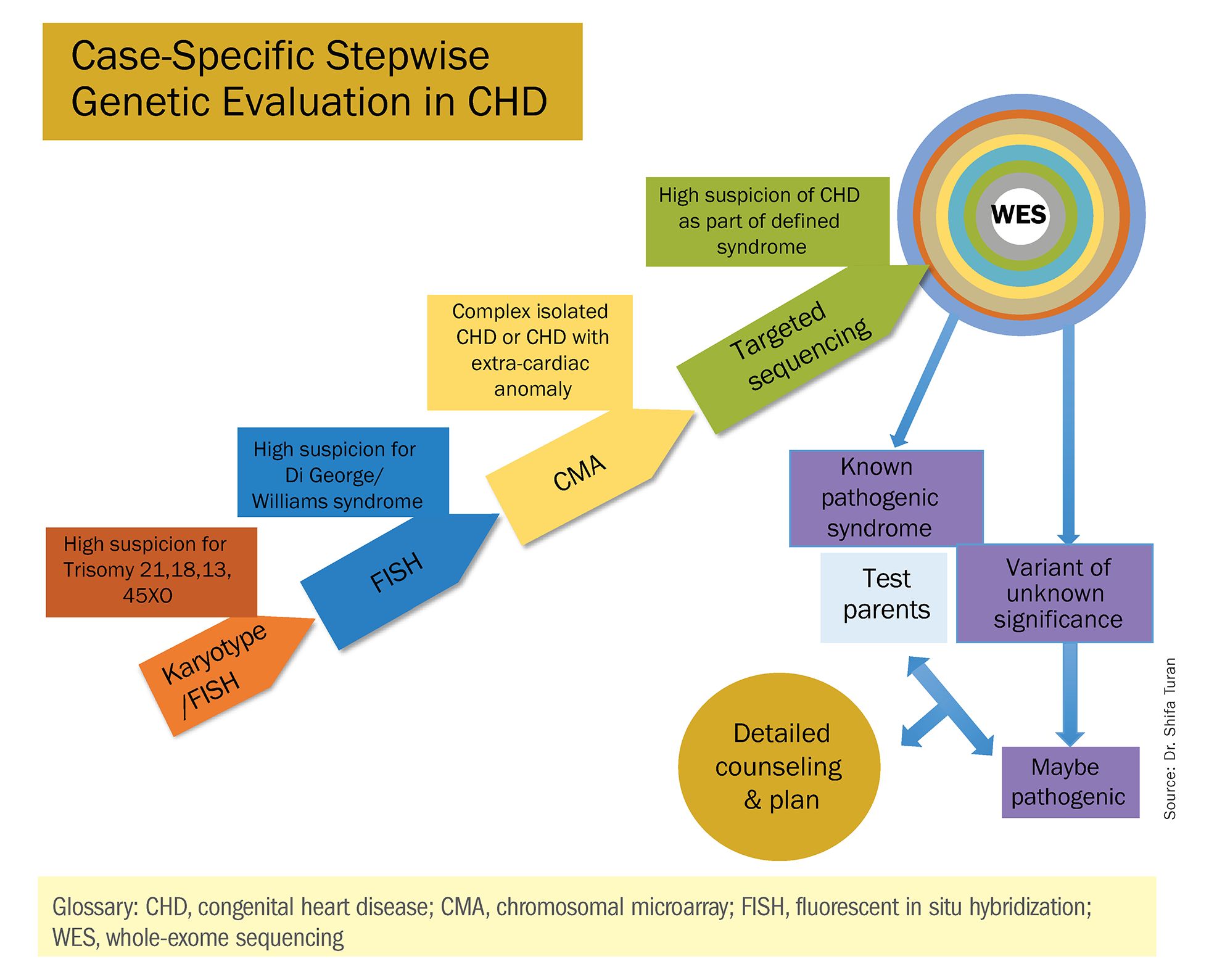

Indeed, although a microarray costs more and takes an additional 2 weeks to run, CMA should be strongly considered as first-line testing for the prenatal genetic evaluation of fetuses with major structural cardiac abnormalities detected by ultrasound. However, there still are cases in which a karyotype might be sufficient. For instance, if I see that a fetus has an atrial-ventricular septal defect on a prenatal ultrasound, and there are markers for trisomy 21, 13, or 18, or Turner’s syndrome (45 XO), I usually recommend a karyotype or FISH rather than an initial CMA. If the karyotype is abnormal – which is likely in such a scenario – there isn’t a need for more extensive testing.

Similarly, when there is high suspicion for DiGeorge syndrome (the 22q11.2 deletion, which often includes cleft palate and aortic arch abnormalities), usually it is most appropriate to perform a FISH test.

CMA is the preferred first modality, however, when prenatal imaging suggests severe CHD – for instance, when there are signs of hypoplastic left heart syndrome or tetralogy of Fallot (a conotruncal defect) – or complex CHD with extracardiac anomalies. In these cases, there is a high likelihood of detecting a small deletion or duplication that would be missed with karyotype.

In the past decade, karyotype and CMA have become the major methods used in our practice. However, targeted next‐generation sequencing and whole‐exome sequencing may become more widely used because these technologies enable rapid analysis of a large number of gene sequences and facilitate discovery of novel causative genes in many genetic diseases that cause CHDs.

Currently, targeted next-generation sequencing has mainly been used in the postnatal setting, and there are limited data available on its prenatal use. Compared with whole-exome sequencing, which sequences all of the protein-coding regions of the genome, targeted next-generation sequencing panels select regions of genes that are known to be associated with diseases of interest.

For CHDs, some perinatal centers have begun using a customized gene panel that targets 77 CHD-associated genes. This particular panel has been shown to be useful in addition to current methods and is an effective tool for prenatal genetic diagnosis.5

Whole-exome sequencing is currently expensive and time consuming. While sometimes it is used in the postnatal context, it is not yet part of routine practice as a prenatal diagnostic tool. As technology advances this will change – early in the next decade, I believe. For now, whole-exome sequencing may be an option for some patients who want to know more when severe CHD is evident on ultrasound and there are negative results from CMA or targeted sequencing. We have diagnosed some rare genetic syndromes using whole-exome sequencing; these diagnoses helped us to better manage the pregnancies.

These choices are part of the case-specific, stepwise approach to genetic evaluation that we take in our fetal heart program. Our goal is to pursue information that will be accurate and valuable for the patient and clinicians, in the most cost-effective and timely manner.

Limitations of noninvasive screening

In our fetal heart program we see increasing numbers of referred patients who have chosen noninvasive cell-free fetal DNA screening (cfDNA) after a cardiac anomaly is detected on ultrasound examination, and who believe that their “low risk” results demonstrate very little or no risk of CHD. Many of these patients express a belief that noninvasive testing is highly sensitive and accurate for fetal anomalies, including CHDs, and are not easily convinced of the value of other genetic tests.

We recently conducted a retrospective chart analysis (unpublished) in which we found that 41% of cases of CHD with abnormal genetics results were not detectable by cfDNA screening.

In the case of atrial-ventricular septal defects and conotruncal abnormalities that often are more associated with common aneuploidies (trisomy 21, 18, 13, and 45 XO), a “high-risk” result from cfDNA screening may offer the family and cardiology/neonatal team some guidance, but a “low-risk” result does not eliminate the risk of a microarray abnormality and thus may provide false reassurance.

Other research has shown that noninvasive screening will miss up to 7.3% of karyotype abnormalities in pregnancies at high risk for common aneuploidies.6

While invasive testing poses a very small risk of miscarriage, it is hard without such testing to elucidate the potential genetic etiologies of CHDs and truly understand the problems. We must take time to thoughtfully counsel patients who decline invasive testing about the limitations of cfDNA screening for CHDs and other anomalies.

Dr. Turan is an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences, and director of the fetal heart program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Dr. Turan reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Oct;12(4):1079-86.

2. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019 Mar;40(3):489-96.

3. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2017 May-Aug;10(2):126-30.

4. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;221:172-76.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;52(2):205-11.

6. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 15;11(1):e0146794.

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are etiologically heterogeneous, but in recent years it has become clear that genetics plays a larger role in the development of CHDs than was previously thought. Research has been shifting from a focus on risk – estimating the magnitude of increased risk, for instance, based on maternal or familial risk factors – to a focus on the etiology of cardiac defects.

In practice, advances in genetic testing technologies have made the underlying causes of CHDs increasingly detectable. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) – technology that detects significantly more and smaller changes in the amount of chromosomal material than traditional karyotype – has been proven to increase the diagnostic yield in cases of isolated CHDs and CHDs with extracardiac anomalies. Targeted next-generation sequencing also is now available as an additional approach in selective cases, and a clinically viable option for whole-exome sequencing is fast approaching.

For researchers, genetic evaluation carries the potential to unravel remaining mysteries about underlying causes of CHDs – to provide pathological insights and identify potential therapeutic targets. Currently, about 6 % of the total pie of presumed genetic determinants of CHDs is attributed to chromosomal anomalies, 10% to copy number variants, and 12% to single-gene defects. The remaining 72% of etiology, approximately, is undetermined.

As Helen Taussig, MD, (known as the founder of pediatric cardiology) once said, common cardiac malformations occurring in otherwise “normal” individuals “must be genetic in origin.”1 Greater use of genetic testing – and in particular, of whole-exome sequencing – will drive down this “undetermined” piece of the genetics pie.

For clinicians and patients, prenatal genetic evaluation can inform clinical management, guiding decisions on the mode, timing, and location of delivery. Genetic assessments help guide the neonatal health care team in taking optimal care of the infant, and the surgeon in preparing for neonatal surgeries and postsurgical complications.

In a recent analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database, prenatal diagnosis was associated with a lower overall prevalence of major preoperative risk factors for cardiac surgery.2 Surgical outcomes themselves also have been shown to be better after the prenatal diagnosis of complex CHDs, mainly because of improvements in perioperative care.3

When genetic etiology is elucidated, the cardiologist also is better able to counsel patients about anticipated challenges – such as the propensity, with certain genetic variants of CHD, to develop neurodevelopmental delays or other cardiac complications – and to target patient follow-up. Patients also can make informed decisions about termination or continuation of a current pregnancy and about family planning in the future.

Fortunately, advances in genetics technology have paralleled technological advancements in ultrasound. As I discussed in part one of this two-part Master Class series, it is now possible to detect many major CHDs well before 16 weeks’ gestation. Checking the structure of the fetal heart at the first-trimester screening and sonography (11-14 weeks of gestation) offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment, counseling, and planning when anomalies are detected.

A personalized approach

There has been growing interest in recent years in CMA for the prenatal genetic workup of CHDs. Microarray targets chromosomal regions at a much higher resolution than traditional karyotype. Traditional karyotype assesses both changes in chromosome number as well as more subtle structural changes such as chromosomal deletions and duplications. CMA finds what traditional karyotype identifies, but in addition, it identifies much smaller, clinically relevant chromosomal deletions and duplications that are not detected by karyotype performed with or without fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH). FISH uses DNA probes that carry fluorescent tags to detect chromosomal DNA.

At our center, we studied the prenatal genetic test results of 145 fetuses diagnosed with CHDs. Each case involved FISH for aneuploidy/karyotype, followed by CMA in cases of a negative karyotype result. CMA increased the diagnostic yield in cases of CHD by 19.8% overall – 17.4% in cases of isolated CHD and 24.5% in cases of CHD plus extracardiac anomalies.4

Indeed, although a microarray costs more and takes an additional 2 weeks to run, CMA should be strongly considered as first-line testing for the prenatal genetic evaluation of fetuses with major structural cardiac abnormalities detected by ultrasound. However, there still are cases in which a karyotype might be sufficient. For instance, if I see that a fetus has an atrial-ventricular septal defect on a prenatal ultrasound, and there are markers for trisomy 21, 13, or 18, or Turner’s syndrome (45 XO), I usually recommend a karyotype or FISH rather than an initial CMA. If the karyotype is abnormal – which is likely in such a scenario – there isn’t a need for more extensive testing.

Similarly, when there is high suspicion for DiGeorge syndrome (the 22q11.2 deletion, which often includes cleft palate and aortic arch abnormalities), usually it is most appropriate to perform a FISH test.

CMA is the preferred first modality, however, when prenatal imaging suggests severe CHD – for instance, when there are signs of hypoplastic left heart syndrome or tetralogy of Fallot (a conotruncal defect) – or complex CHD with extracardiac anomalies. In these cases, there is a high likelihood of detecting a small deletion or duplication that would be missed with karyotype.

In the past decade, karyotype and CMA have become the major methods used in our practice. However, targeted next‐generation sequencing and whole‐exome sequencing may become more widely used because these technologies enable rapid analysis of a large number of gene sequences and facilitate discovery of novel causative genes in many genetic diseases that cause CHDs.

Currently, targeted next-generation sequencing has mainly been used in the postnatal setting, and there are limited data available on its prenatal use. Compared with whole-exome sequencing, which sequences all of the protein-coding regions of the genome, targeted next-generation sequencing panels select regions of genes that are known to be associated with diseases of interest.

For CHDs, some perinatal centers have begun using a customized gene panel that targets 77 CHD-associated genes. This particular panel has been shown to be useful in addition to current methods and is an effective tool for prenatal genetic diagnosis.5

Whole-exome sequencing is currently expensive and time consuming. While sometimes it is used in the postnatal context, it is not yet part of routine practice as a prenatal diagnostic tool. As technology advances this will change – early in the next decade, I believe. For now, whole-exome sequencing may be an option for some patients who want to know more when severe CHD is evident on ultrasound and there are negative results from CMA or targeted sequencing. We have diagnosed some rare genetic syndromes using whole-exome sequencing; these diagnoses helped us to better manage the pregnancies.

These choices are part of the case-specific, stepwise approach to genetic evaluation that we take in our fetal heart program. Our goal is to pursue information that will be accurate and valuable for the patient and clinicians, in the most cost-effective and timely manner.

Limitations of noninvasive screening

In our fetal heart program we see increasing numbers of referred patients who have chosen noninvasive cell-free fetal DNA screening (cfDNA) after a cardiac anomaly is detected on ultrasound examination, and who believe that their “low risk” results demonstrate very little or no risk of CHD. Many of these patients express a belief that noninvasive testing is highly sensitive and accurate for fetal anomalies, including CHDs, and are not easily convinced of the value of other genetic tests.

We recently conducted a retrospective chart analysis (unpublished) in which we found that 41% of cases of CHD with abnormal genetics results were not detectable by cfDNA screening.

In the case of atrial-ventricular septal defects and conotruncal abnormalities that often are more associated with common aneuploidies (trisomy 21, 18, 13, and 45 XO), a “high-risk” result from cfDNA screening may offer the family and cardiology/neonatal team some guidance, but a “low-risk” result does not eliminate the risk of a microarray abnormality and thus may provide false reassurance.

Other research has shown that noninvasive screening will miss up to 7.3% of karyotype abnormalities in pregnancies at high risk for common aneuploidies.6

While invasive testing poses a very small risk of miscarriage, it is hard without such testing to elucidate the potential genetic etiologies of CHDs and truly understand the problems. We must take time to thoughtfully counsel patients who decline invasive testing about the limitations of cfDNA screening for CHDs and other anomalies.

Dr. Turan is an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences, and director of the fetal heart program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Dr. Turan reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Oct;12(4):1079-86.

2. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019 Mar;40(3):489-96.

3. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2017 May-Aug;10(2):126-30.

4. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;221:172-76.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;52(2):205-11.

6. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 15;11(1):e0146794.

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are etiologically heterogeneous, but in recent years it has become clear that genetics plays a larger role in the development of CHDs than was previously thought. Research has been shifting from a focus on risk – estimating the magnitude of increased risk, for instance, based on maternal or familial risk factors – to a focus on the etiology of cardiac defects.

In practice, advances in genetic testing technologies have made the underlying causes of CHDs increasingly detectable. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) – technology that detects significantly more and smaller changes in the amount of chromosomal material than traditional karyotype – has been proven to increase the diagnostic yield in cases of isolated CHDs and CHDs with extracardiac anomalies. Targeted next-generation sequencing also is now available as an additional approach in selective cases, and a clinically viable option for whole-exome sequencing is fast approaching.

For researchers, genetic evaluation carries the potential to unravel remaining mysteries about underlying causes of CHDs – to provide pathological insights and identify potential therapeutic targets. Currently, about 6 % of the total pie of presumed genetic determinants of CHDs is attributed to chromosomal anomalies, 10% to copy number variants, and 12% to single-gene defects. The remaining 72% of etiology, approximately, is undetermined.

As Helen Taussig, MD, (known as the founder of pediatric cardiology) once said, common cardiac malformations occurring in otherwise “normal” individuals “must be genetic in origin.”1 Greater use of genetic testing – and in particular, of whole-exome sequencing – will drive down this “undetermined” piece of the genetics pie.

For clinicians and patients, prenatal genetic evaluation can inform clinical management, guiding decisions on the mode, timing, and location of delivery. Genetic assessments help guide the neonatal health care team in taking optimal care of the infant, and the surgeon in preparing for neonatal surgeries and postsurgical complications.

In a recent analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database, prenatal diagnosis was associated with a lower overall prevalence of major preoperative risk factors for cardiac surgery.2 Surgical outcomes themselves also have been shown to be better after the prenatal diagnosis of complex CHDs, mainly because of improvements in perioperative care.3

When genetic etiology is elucidated, the cardiologist also is better able to counsel patients about anticipated challenges – such as the propensity, with certain genetic variants of CHD, to develop neurodevelopmental delays or other cardiac complications – and to target patient follow-up. Patients also can make informed decisions about termination or continuation of a current pregnancy and about family planning in the future.

Fortunately, advances in genetics technology have paralleled technological advancements in ultrasound. As I discussed in part one of this two-part Master Class series, it is now possible to detect many major CHDs well before 16 weeks’ gestation. Checking the structure of the fetal heart at the first-trimester screening and sonography (11-14 weeks of gestation) offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment, counseling, and planning when anomalies are detected.

A personalized approach

There has been growing interest in recent years in CMA for the prenatal genetic workup of CHDs. Microarray targets chromosomal regions at a much higher resolution than traditional karyotype. Traditional karyotype assesses both changes in chromosome number as well as more subtle structural changes such as chromosomal deletions and duplications. CMA finds what traditional karyotype identifies, but in addition, it identifies much smaller, clinically relevant chromosomal deletions and duplications that are not detected by karyotype performed with or without fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH). FISH uses DNA probes that carry fluorescent tags to detect chromosomal DNA.

At our center, we studied the prenatal genetic test results of 145 fetuses diagnosed with CHDs. Each case involved FISH for aneuploidy/karyotype, followed by CMA in cases of a negative karyotype result. CMA increased the diagnostic yield in cases of CHD by 19.8% overall – 17.4% in cases of isolated CHD and 24.5% in cases of CHD plus extracardiac anomalies.4

Indeed, although a microarray costs more and takes an additional 2 weeks to run, CMA should be strongly considered as first-line testing for the prenatal genetic evaluation of fetuses with major structural cardiac abnormalities detected by ultrasound. However, there still are cases in which a karyotype might be sufficient. For instance, if I see that a fetus has an atrial-ventricular septal defect on a prenatal ultrasound, and there are markers for trisomy 21, 13, or 18, or Turner’s syndrome (45 XO), I usually recommend a karyotype or FISH rather than an initial CMA. If the karyotype is abnormal – which is likely in such a scenario – there isn’t a need for more extensive testing.

Similarly, when there is high suspicion for DiGeorge syndrome (the 22q11.2 deletion, which often includes cleft palate and aortic arch abnormalities), usually it is most appropriate to perform a FISH test.

CMA is the preferred first modality, however, when prenatal imaging suggests severe CHD – for instance, when there are signs of hypoplastic left heart syndrome or tetralogy of Fallot (a conotruncal defect) – or complex CHD with extracardiac anomalies. In these cases, there is a high likelihood of detecting a small deletion or duplication that would be missed with karyotype.

In the past decade, karyotype and CMA have become the major methods used in our practice. However, targeted next‐generation sequencing and whole‐exome sequencing may become more widely used because these technologies enable rapid analysis of a large number of gene sequences and facilitate discovery of novel causative genes in many genetic diseases that cause CHDs.

Currently, targeted next-generation sequencing has mainly been used in the postnatal setting, and there are limited data available on its prenatal use. Compared with whole-exome sequencing, which sequences all of the protein-coding regions of the genome, targeted next-generation sequencing panels select regions of genes that are known to be associated with diseases of interest.

For CHDs, some perinatal centers have begun using a customized gene panel that targets 77 CHD-associated genes. This particular panel has been shown to be useful in addition to current methods and is an effective tool for prenatal genetic diagnosis.5

Whole-exome sequencing is currently expensive and time consuming. While sometimes it is used in the postnatal context, it is not yet part of routine practice as a prenatal diagnostic tool. As technology advances this will change – early in the next decade, I believe. For now, whole-exome sequencing may be an option for some patients who want to know more when severe CHD is evident on ultrasound and there are negative results from CMA or targeted sequencing. We have diagnosed some rare genetic syndromes using whole-exome sequencing; these diagnoses helped us to better manage the pregnancies.

These choices are part of the case-specific, stepwise approach to genetic evaluation that we take in our fetal heart program. Our goal is to pursue information that will be accurate and valuable for the patient and clinicians, in the most cost-effective and timely manner.

Limitations of noninvasive screening

In our fetal heart program we see increasing numbers of referred patients who have chosen noninvasive cell-free fetal DNA screening (cfDNA) after a cardiac anomaly is detected on ultrasound examination, and who believe that their “low risk” results demonstrate very little or no risk of CHD. Many of these patients express a belief that noninvasive testing is highly sensitive and accurate for fetal anomalies, including CHDs, and are not easily convinced of the value of other genetic tests.

We recently conducted a retrospective chart analysis (unpublished) in which we found that 41% of cases of CHD with abnormal genetics results were not detectable by cfDNA screening.

In the case of atrial-ventricular septal defects and conotruncal abnormalities that often are more associated with common aneuploidies (trisomy 21, 18, 13, and 45 XO), a “high-risk” result from cfDNA screening may offer the family and cardiology/neonatal team some guidance, but a “low-risk” result does not eliminate the risk of a microarray abnormality and thus may provide false reassurance.

Other research has shown that noninvasive screening will miss up to 7.3% of karyotype abnormalities in pregnancies at high risk for common aneuploidies.6

While invasive testing poses a very small risk of miscarriage, it is hard without such testing to elucidate the potential genetic etiologies of CHDs and truly understand the problems. We must take time to thoughtfully counsel patients who decline invasive testing about the limitations of cfDNA screening for CHDs and other anomalies.

Dr. Turan is an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences, and director of the fetal heart program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and director of the Fetal Heart Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Dr. Turan reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Oct;12(4):1079-86.

2. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019 Mar;40(3):489-96.

3. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2017 May-Aug;10(2):126-30.

4. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;221:172-76.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;52(2):205-11.

6. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 15;11(1):e0146794.

Zulresso: Hope and lingering questions

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.