User login

Would routine use of tranexamic acid for PPH be cost-effective in the United States?

Sudhof LS, Shainker SA, Einerson BD. Tranexamic acid in the routine treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online June 18, 2019. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.030.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial showed that the use of TXA, an antifibrinolytic agent, for PPH decreases hemorrhage-related mortality and laparotomy. Routine use of TXA for PPH has demonstrated cost-effectiveness in low-resource countries, where hemorrhage-related mortality rates are higher than in the United States. This study aimed to determine if routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States also is cost-effective.

Details of the study

Sudhof and colleagues conducted a decision-tree analysis to compare the cost-effectiveness of 3 strategies regarding routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States: no TXA, TXA given at any time, and TXA given within 3 hours of delivery.

Health care system perspective. In the primary analysis, the 3 strategies were evaluated from the perspective of the health care system. Outcomes included cost, number of laparotomies, and maternal deaths from delivery until 6 weeks postpartum. Rates of hemorrhage and related complications, as well as cost assumptions, were derived from multiple US-based studies. The relative risk reduction in death and laparotomy with TXA in the United States was assumed to be similar to that found in the WOMAN trial (19% and 36%, respectively).

Societal perspective. In the secondary analysis, the 3 TXA strategies were evaluated from the societal perspective, comparing quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and cost per QALY. For both the primary and secondary analyses, sensitivity analyses were performed across a range of values for each input.

Main findings. Tranexamic acid use would be cost saving if the relative risk reduction for maternal death with TXA was greater than approximately 5%, which is significantly lower than that seen in the WOMAN trial (19%). The primary analysis demonstrated that—assuming a 3% rate of PPH—giving TXA to women with PPH would save $11.3 million, prevent 334 laparotomies, and avert 9 maternal deaths annually in the United States. This cost saving nearly tripled if TXA was administered within 3 hours of delivery, with 5 additional maternal deaths prevented.

Secondary analysis incorporating QALYs also showed TXA use to be cost-effective. These findings held through various sensitivity analyses.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

This study is novel in its critical objective to determine the cost-effectiveness of routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States. Robust modeling using Monte Carlo estimation and a variety of sensitivity analyses add reliability to the authors’ findings.

This work is limited, however, by the assumptions put into the authors’ models. For example, outcome data regarding effectiveness of TXA was taken from the WOMAN trial, which was not performed within the United States. In addition, it is difficult to quantify in dollars an event as profound as a maternal death. The authors recognize that they likely underestimate the “cost” of a maternal death, but that this underestimation would only increase the cost-effectiveness of TXA.

Finally, it is important to take into account that such economic analyses are helpful to inform institutional guidelines and hemorrhage protocols, but that patient-specific decision-making should be individualized based on the clinical scenario at hand.

Routine use of TXA for PPH, particularly within 3 hours of delivery, is likely cost-effective in the United States. Consideration should be given to including TXA in institutional hemorrhage protocols.

REBECCA F. HAMM, MD, and ADI HIRSHBERG, MD

Sudhof LS, Shainker SA, Einerson BD. Tranexamic acid in the routine treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online June 18, 2019. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.030.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial showed that the use of TXA, an antifibrinolytic agent, for PPH decreases hemorrhage-related mortality and laparotomy. Routine use of TXA for PPH has demonstrated cost-effectiveness in low-resource countries, where hemorrhage-related mortality rates are higher than in the United States. This study aimed to determine if routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States also is cost-effective.

Details of the study

Sudhof and colleagues conducted a decision-tree analysis to compare the cost-effectiveness of 3 strategies regarding routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States: no TXA, TXA given at any time, and TXA given within 3 hours of delivery.

Health care system perspective. In the primary analysis, the 3 strategies were evaluated from the perspective of the health care system. Outcomes included cost, number of laparotomies, and maternal deaths from delivery until 6 weeks postpartum. Rates of hemorrhage and related complications, as well as cost assumptions, were derived from multiple US-based studies. The relative risk reduction in death and laparotomy with TXA in the United States was assumed to be similar to that found in the WOMAN trial (19% and 36%, respectively).

Societal perspective. In the secondary analysis, the 3 TXA strategies were evaluated from the societal perspective, comparing quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and cost per QALY. For both the primary and secondary analyses, sensitivity analyses were performed across a range of values for each input.

Main findings. Tranexamic acid use would be cost saving if the relative risk reduction for maternal death with TXA was greater than approximately 5%, which is significantly lower than that seen in the WOMAN trial (19%). The primary analysis demonstrated that—assuming a 3% rate of PPH—giving TXA to women with PPH would save $11.3 million, prevent 334 laparotomies, and avert 9 maternal deaths annually in the United States. This cost saving nearly tripled if TXA was administered within 3 hours of delivery, with 5 additional maternal deaths prevented.

Secondary analysis incorporating QALYs also showed TXA use to be cost-effective. These findings held through various sensitivity analyses.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

This study is novel in its critical objective to determine the cost-effectiveness of routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States. Robust modeling using Monte Carlo estimation and a variety of sensitivity analyses add reliability to the authors’ findings.

This work is limited, however, by the assumptions put into the authors’ models. For example, outcome data regarding effectiveness of TXA was taken from the WOMAN trial, which was not performed within the United States. In addition, it is difficult to quantify in dollars an event as profound as a maternal death. The authors recognize that they likely underestimate the “cost” of a maternal death, but that this underestimation would only increase the cost-effectiveness of TXA.

Finally, it is important to take into account that such economic analyses are helpful to inform institutional guidelines and hemorrhage protocols, but that patient-specific decision-making should be individualized based on the clinical scenario at hand.

Routine use of TXA for PPH, particularly within 3 hours of delivery, is likely cost-effective in the United States. Consideration should be given to including TXA in institutional hemorrhage protocols.

REBECCA F. HAMM, MD, and ADI HIRSHBERG, MD

Sudhof LS, Shainker SA, Einerson BD. Tranexamic acid in the routine treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online June 18, 2019. doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.030.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial showed that the use of TXA, an antifibrinolytic agent, for PPH decreases hemorrhage-related mortality and laparotomy. Routine use of TXA for PPH has demonstrated cost-effectiveness in low-resource countries, where hemorrhage-related mortality rates are higher than in the United States. This study aimed to determine if routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States also is cost-effective.

Details of the study

Sudhof and colleagues conducted a decision-tree analysis to compare the cost-effectiveness of 3 strategies regarding routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States: no TXA, TXA given at any time, and TXA given within 3 hours of delivery.

Health care system perspective. In the primary analysis, the 3 strategies were evaluated from the perspective of the health care system. Outcomes included cost, number of laparotomies, and maternal deaths from delivery until 6 weeks postpartum. Rates of hemorrhage and related complications, as well as cost assumptions, were derived from multiple US-based studies. The relative risk reduction in death and laparotomy with TXA in the United States was assumed to be similar to that found in the WOMAN trial (19% and 36%, respectively).

Societal perspective. In the secondary analysis, the 3 TXA strategies were evaluated from the societal perspective, comparing quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and cost per QALY. For both the primary and secondary analyses, sensitivity analyses were performed across a range of values for each input.

Main findings. Tranexamic acid use would be cost saving if the relative risk reduction for maternal death with TXA was greater than approximately 5%, which is significantly lower than that seen in the WOMAN trial (19%). The primary analysis demonstrated that—assuming a 3% rate of PPH—giving TXA to women with PPH would save $11.3 million, prevent 334 laparotomies, and avert 9 maternal deaths annually in the United States. This cost saving nearly tripled if TXA was administered within 3 hours of delivery, with 5 additional maternal deaths prevented.

Secondary analysis incorporating QALYs also showed TXA use to be cost-effective. These findings held through various sensitivity analyses.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

This study is novel in its critical objective to determine the cost-effectiveness of routine use of TXA for PPH in the United States. Robust modeling using Monte Carlo estimation and a variety of sensitivity analyses add reliability to the authors’ findings.

This work is limited, however, by the assumptions put into the authors’ models. For example, outcome data regarding effectiveness of TXA was taken from the WOMAN trial, which was not performed within the United States. In addition, it is difficult to quantify in dollars an event as profound as a maternal death. The authors recognize that they likely underestimate the “cost” of a maternal death, but that this underestimation would only increase the cost-effectiveness of TXA.

Finally, it is important to take into account that such economic analyses are helpful to inform institutional guidelines and hemorrhage protocols, but that patient-specific decision-making should be individualized based on the clinical scenario at hand.

Routine use of TXA for PPH, particularly within 3 hours of delivery, is likely cost-effective in the United States. Consideration should be given to including TXA in institutional hemorrhage protocols.

REBECCA F. HAMM, MD, and ADI HIRSHBERG, MD

The case for outpatient cervical ripening for IOL at term for low-risk pregnancies

Case 1 Induction at 39 weeks in a healthy nulliparous woman

A healthy 35-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 weeks 0 days and with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. She inquires about scheduling an induction of labor, noting that she read a news story about induction at 39 weeks and that it might lower her chance of having a cesarean delivery (CD).

You perform a cervical exam—she is 1 cm dilated, 3 cm long, -2 station, posterior, and firm. You sweep her membranes after obtaining verbal consent. After describing the induction process, you explain that she might be hospitalized for several days before the birth given the need for cervical ripening. “You mean I need to stay in the hospital for the entire process?” she asks incredulously.

Over the past 20 years, the percentage of patients undergoing induction of labor (IOL) has increased from 10% to 25%.1 This percentage likely will rise over time, particularly in the wake of a recent randomized controlled trial suggesting potential maternal benefits, such as reduced CD rate, for nulliparas induced at 39 weeks compared with expectant management.2 Although there have not been any changes to guidelines for timing of IOL from such professional societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) or the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, key considerations of rising IOL volume include patient experience, labor and delivery (L&D) units’ capacity and resources, and associated health care costs.

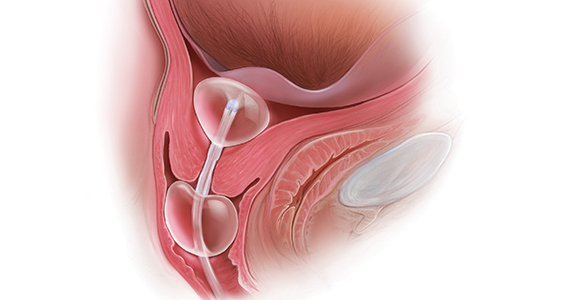

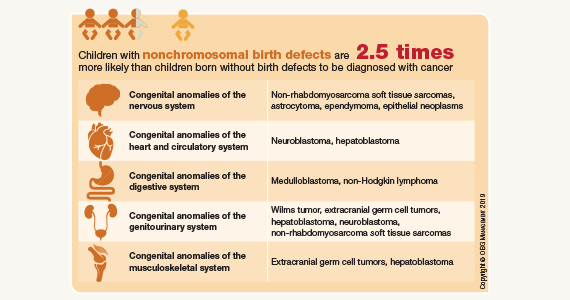

An essential part of successful induction involves patience. Induction can be a lengthy process, particularly for nulliparas with unripe cervices. Cervical ripening is a necessary component of successful labor induction, whether achieved mechanically or pharmacologically with synthetic prostaglandins, and it has been shown to lower the chance of CD.3,4 However, achieving a ripe cervix is often the lengthiest part of an induction, and not uncommonly consumes 12 to 24 hours or more of inpatient time. Investigators have sought ways to make this process more expeditious. For example, the FOR-MOMI trial demonstrated that the induction-to-delivery time was several hours shorter when cervical ripening combined mechanical and pharmacologic approaches (Foley balloon plus misoprostol), compared with either method alone, without any increase in maternal or fetal complication rates.5

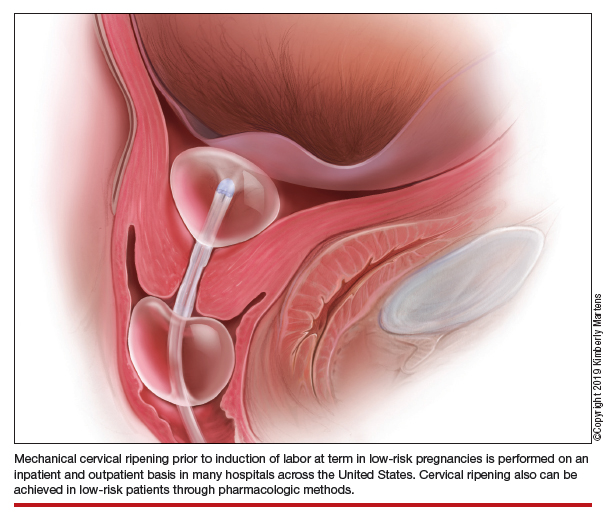

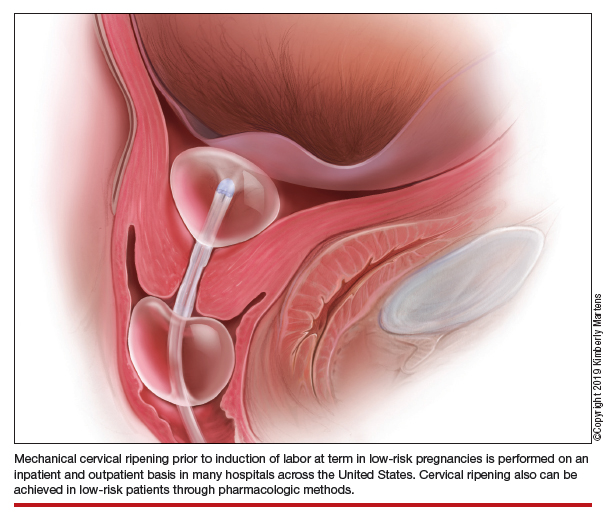

Better yet, what if admission to the L&D unit for IOL at term could be deferred until the cervix is ripe? A number of hospitals in the United States have successfully introduced outpatient cervical ripening, and several small observational and randomized controlled trials have reported good results in terms of safety, efficacy and time saved, and patient experience. Here, we will make the case that outpatient cervical ripening should be the standard of care for low-risk pregnancies.

Mechanical cervical ripening

Safety

Although data are limited on the safety, the authors of an ACOG Practice Bulletin suggest that, based on the available evidence of mechanical ripening in an inpatient setting, it is also appropriate in the outpatient setting.6 Unlike cervical ripening using prostaglandins, mechanical ripening is not associated with tachysystole, fetal intolerance of labor, or meconium staining.3 A cohort study of nearly 2,000 low-risk patients who underwent Foley catheter placement for cervical ripening using an outpatient protocol but monitored overnight as inpatients and evaluated for adverse outcomes found no CD for fetal distress, vaginal bleeding, placental abruption, or intrapartum stillbirth.7 The authors posited that, given this safety profile in the inpatient setting, that mechanical cervical ripening with a Foley catheter would be appropriate for outpatient use in low-risk populations. Other systematic reviews have been reassuring as well, with exceedingly low complication rates during inpatient mechanical cervical ripening.8 These data advocate for the evaluation of cervical ripening in the outpatient setting.

The evidence for outpatient mechanical ripening, although again limited, also has demonstrated safety. There does not appear to be an increased rate of maternal or neonatal complications, including infectious morbidity, postpartum hemorrhage, CD, operative vaginal delivery, or fetal distress.9-12

Continue to: Efficacy and length-of-stay...

Efficacy and length-of-stay

Efficacy also generally has been shown to be similar when mechanical methods are used in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Small randomized trials of outpatient versus inpatient Foley catheter ripening have shown decreased length of stay (by 10 to 13 hours) and similar or less oxytocin use in the outpatient groups, as well as similar Bishop scores after cervical ripening and no difference in maternal or fetal outcomes.9,11,13,14

One major concern with increasing IOL prevalence is the availability of hospital resources and the associated health care costs, given the known increased length of inpatient stay due to cervical ripening time. Admission to an L&D unit is resource intensive; the costs are similar to admission to an intensive care unit in many hospitals given its level of acuity and high nurse/patient ratio. However, given the safety of outpatient mechanical cervical ripening described above, we argue that routinely admitting low-risk patients for mechanical ripening constitutes a suboptimal use of costly resources.

Indeed, data suggest significant inpatient time savings if cervical ripening can be accomplished prior to admission. A cost-effectiveness analysis in the Netherlands demonstrated a nearly 1,000-euro decrease in cost per induction when Foley catheter induction was done on an outpatient basis.15 Interestingly, a recent trial confined to multiparas found no differences in hospital time when comparing outpatient ripening with Foley balloon alone with inpatient ripening with Foley balloon plus simultaneous oxytocin.10 This certainly merits further study, but it may be that the largest time- and cost-savings are among nulliparas.

Patient preferences

Relatively few studies specifically have addressed patient experiences with outpatient versus inpatient mechanical cervical ripening. Outpatient cervical ripening may provide patients with the benefits of being in the comfort of their own homes with their preferred support persons, increased mobility, more bodily autonomy, and satisfaction with their birthing process.

In a pilot trial involving 48 women, inpatient was compared with outpatient cervical ripening using a Foley balloon. Those in the outpatient group reported getting more rest, feeling less isolated, and having enough privacy. However, participants in both groups were equally satisfied and equally likely to recommend their method of induction to others.11 Another study comparing outpatient versus inpatient Foley balloon cervical ripening found that 85% of patients who underwent outpatient ripening were satisfied with the induction method; however, no query or comparison was done with the inpatient group.12 A trial comparing outpatient mechanical cervical ripening with inpatient misoprostol found that outpatient participants reported several hours more sleep and less pain.16 And in a discrete choice experiment of British gravidas, participants favored the option of outpatient cervical ripening, even if it meant an extra 1.4 trips to the hospital and over an hour of extra travel time.17

While these preliminary findings provide some insight that patients may prefer an outpatient approach to cervical ripening, more studies are needed to fully evaluate patient desires.

Continue to: Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening...

Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening

Most patients undergoing scheduled IOL are reasonable candidates for outpatient cervical ripening based on safety and efficacy. By definition, scheduling in advance implies that the provider has determined that outpatient management is reasonable until that date, and the plan for outpatient ripening need not prolong this period.

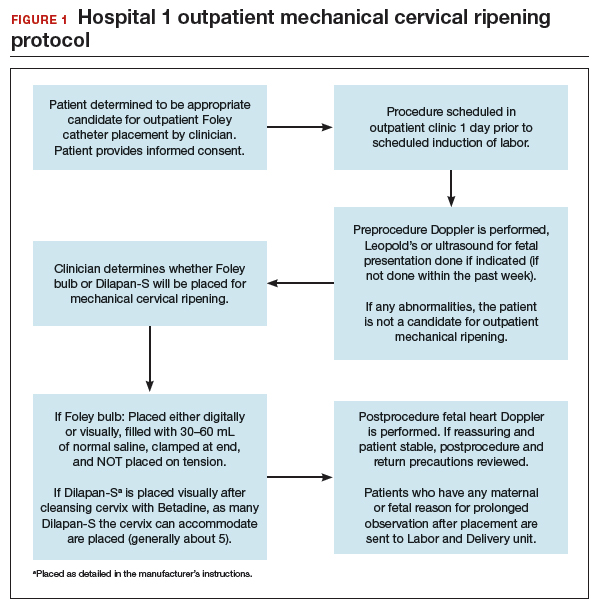

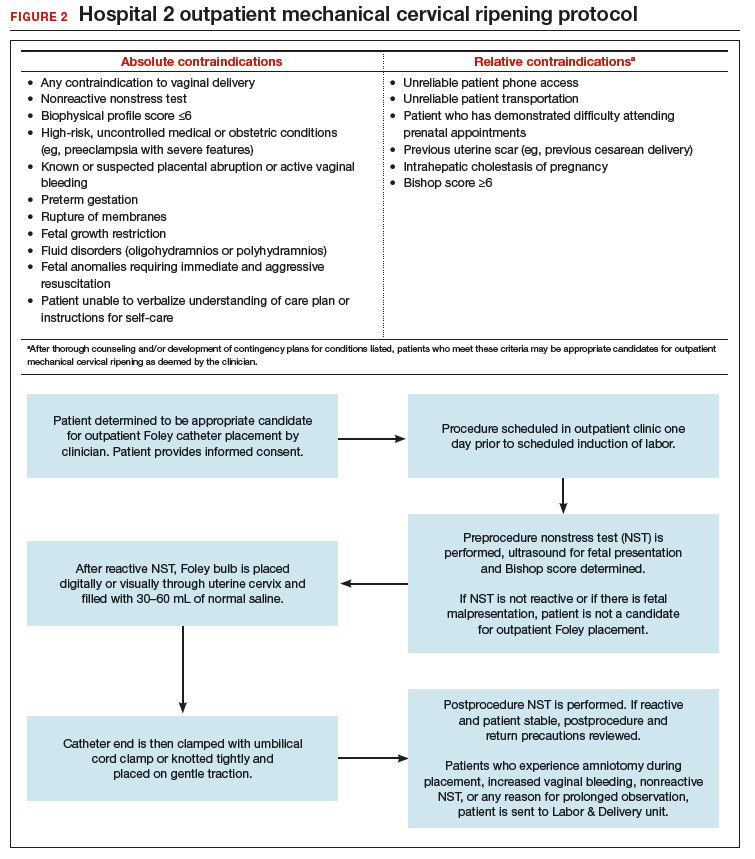

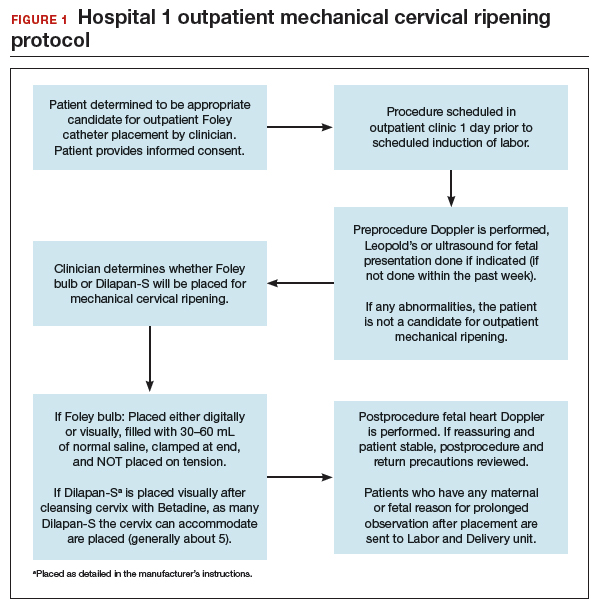

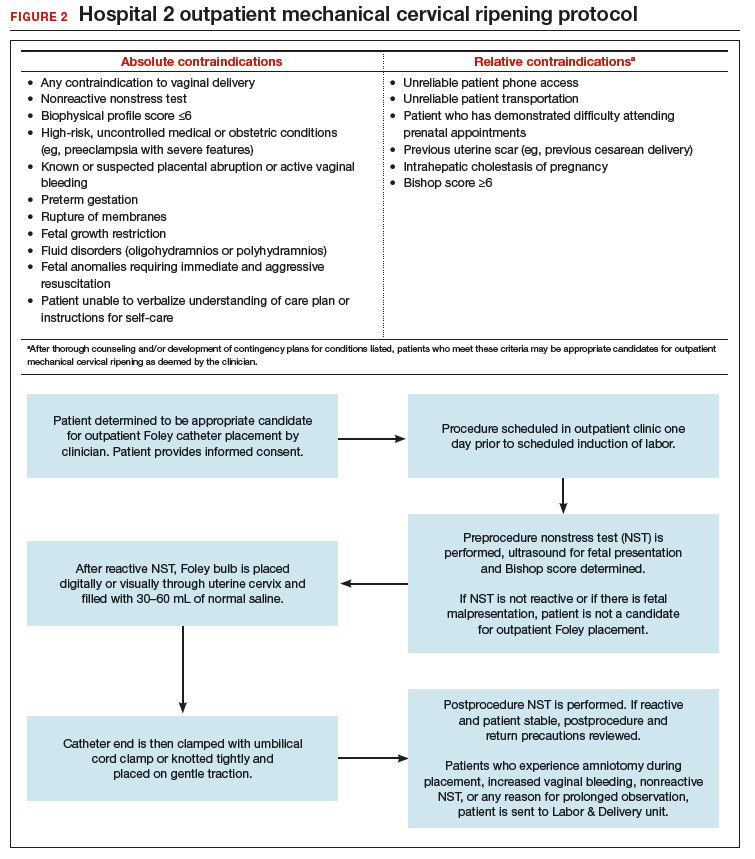

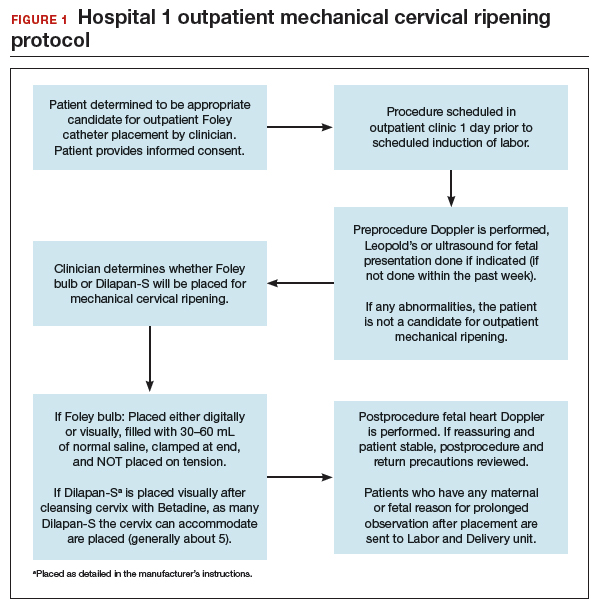

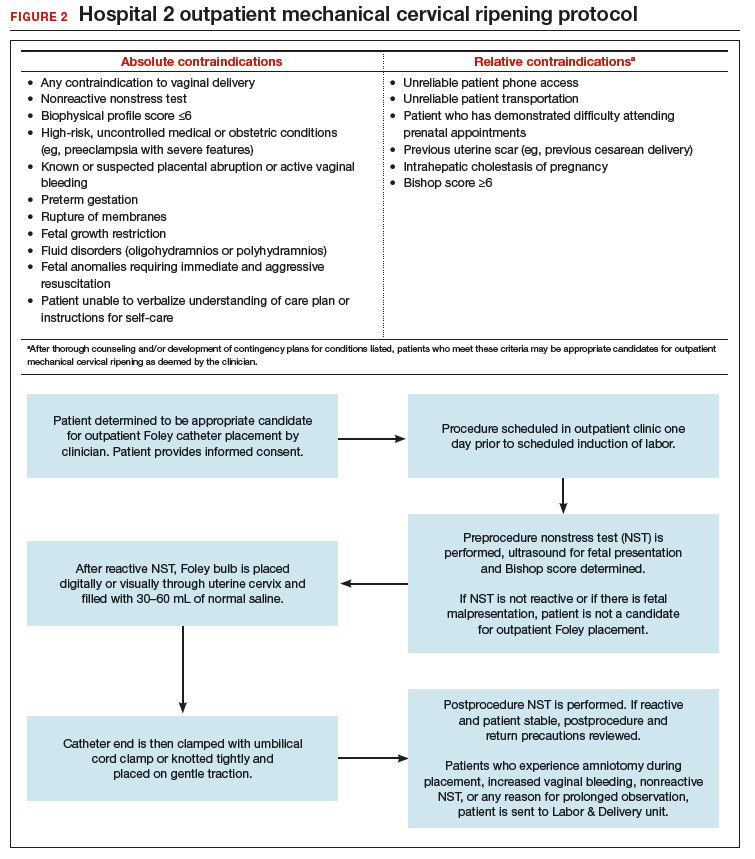

FIGURES 1 and 2 show protocols for our 2 hospital centers, which regularly allow for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening. In the process of protocol development, we identified absolute and relative contraindications to determine appropriate candidates. We exclude women who require inpatient management of medical or obstetric conditions (for example, women with severe preeclampsia or any condition requiring continuous fetal monitoring). We also do not routinely recommend outpatient cervical ripening to patients who do not have the necessary social conditions to make this process as safe as possible (including stable housing, reliable transportation, and a support person), although this occurs with some exceptions depending on individual patient situations.

Some examples of ideal candidates for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening include those undergoing elective or routine prolonged gestation inductions, or inductions for well-controlled, stable conditions (chronic hypertension and gestational diabetes). At one center, after thorough counseling and assessment, outpatient cervical ripening is also offered to patients with mild risk factors, including twins, prior low transverse CD, stable preeclampsia without severe features, isolated oligohydramnios with otherwise reassuring fetal status, and other similar conditions.

After mechanical cervical ripening placement (either Foley catheter or mechanical dilators), the clinician completes a postprocedure safety checklist and detailed procedure documentation, including number and type of foreign bodies placed. If there are any concerns regarding maternal or fetal well-being, the patient is sent to L&D for evaluation. If the procedure was tolerated well, the patient is discharged home, after a reactive postprocedure nonstress test is done, with detailed instructions for self-care, as well as with a list of symptoms that warrant prompt evaluation prior to scheduled induction time. In a large California hospital group following a similar protocol, only about 5% of women presented in labor before their scheduled induction.18

Case 2 Cervical ripening for labor preparation in low-risk pregnancy

A 32-year-old woman (G1P0) with an uncomplicated pregnancy at 40 weeks and 3 days presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. Her vital signs are normal, and her fetus is vertex with an estimated fetal weight of 7.5 lb by Leopald’s maneuvers. You perform a cervical exam and find that her cervix is closed, long, and posterior.

You discuss with her your recommendation for induction of labor by 41 weeks, and she agrees. You also discuss the need for cervical ripening and recommend misoprostol given her closed cervix. You explain that several doses may be needed to get her cervix ready for labor, and she asks, “Do I have to stay in the hospital that whole time?”

Pharmacologic cervical ripening

Efficacy

There are multiple pharmacologic agents that can be used for ripening an unfavorable cervix. The main agents used in the United States are prostaglandins, either PGE1 (oral or vaginal misoprostol) or PGE2 in a gel or sustained-release vaginal insert (dinoprostone).

Outpatient misoprostol to avoid labor induction. Many studies have looked at outpatient misoprostol use as a “prophylactic measure” (to prevent the need for labor induction). For example, Gaffaney and colleagues showed that administering outpatient oral misoprostol (100 µg every 24 hours for up to 3 doses) after 40 weeks’ gestation to women with an unfavorable cervix significantly decreased the time to delivery by a day and a half.19 Similarly, PonMalar and colleagues demonstrated that administering 25 µg of vaginal misoprostol in a single dose as an outpatient after stripping the membranes significantly reduced time to delivery by 2 days.20 And Stitely and colleagues found a significant reduction in the need for labor induction with the use of outpatient vaginal misoprostol. They administered up to 2 doses of misoprostol 25 µg vaginally every 24 hours for the 48 hours prior to a scheduled postdates induction and found a large reduction in the need for labor induction (11% vs 85%; P<.01).21

Continue to: Multiple protocols and regimens...

Multiple protocols and regimens have been studied but, overall, the findings suggest that administering outpatient misoprostol may shorten the time interval to spontaneous labor and decrease the need for a formal labor induction.19-23

Inpatient compared with outpatient prostaglandin use. These trials of “prophylactic” misoprostol generally have compared outpatient administration of misoprostol with placebo. Prostaglandins are one of the most common methods of inpatient cervical ripening, so what about comparisons of inpatient cervical ripening with outpatient prostaglandin administration? There are a handful of studies that make this comparison.

Chang and colleagues looked retrospectively at inpatient and outpatient misoprostol and found that outpatient administration saved 3 to 5 hours on labor and delivery.24 Biem and colleagues randomly assigned women to either inpatient cervical ripening with PGE2 intravaginal inserts or 1 hour of inpatient monitoring after PGE2 administration and then outpatient discharge until the onset of labor or for a nonstress test at 12 hours. They found that those who underwent outpatient ripening spent 8 hours less on labor and delivery and were more highly satisfied with the initial 12 hours of labor induction experience (56% vs 39%; P<.01).25

The largest randomized controlled trial conducted to study outpatient prostaglandin use was the OPRA study (involving 827 women). Investigators compared inpatient to outpatient PGE2 intravaginal gel.26 The primary outcome was total oxytocin administration, which was not different between groups. The study was underpowered, however, as 50% of women labored spontaneously postrandomization. But in the outpatient arm, less than half of the women required additional inpatient ripening, and nearly 40% returned in spontaneous labor, suggesting that outpatient prostaglandin administration may indeed save women a significant amount of time on labor and delivery.

Safety

The safety of outpatient administration of prostaglandins is the biggest concern, especially since, when prostaglandins are compared to outpatient Foley catheter use, Foleys are overall associated with less tachysystole, fetal intolerance, and meconium-stained fluid.3 Foley catheter use for cervical ripening may not be an appropriate choice for all patients, however. For instance, our case patient has a closed cervix, which could make Foley insertion uncomfortable or even impossible. Misoprostol use also offers the potential for flexibility in cervical ripening protocols as patients need not return for Foley balloon removal and indeed labor induction need not take place immediately after administration of misoprostol.

Patients also may prefer outpatient cervical ripening with misoprostol over a Foley. There are some data to suggest that women, overall, have a preference toward prostaglandins; in the PROBAAT-II trial, which compared inpatient oral misoprostol to Foley catheter for cervical ripening, 12% of women in the Foley arm would have preferred another method of induction (vs 6% in the misoprostol arm; P = .02).27 This preference may be magnified in an outpatient setting.

But, again, is outpatient administration of prostaglandins safe? The published trials thus far have not reported an increase in out-of-hospital deliveries or adverse fetal outcomes. However, studies have been of limited size to see more rare outcomes. Unfortunately, an adequately powered study to demonstrate safety is likely never to be accomplished, given that if used responsibly (in low-risk patients with adequate monitoring after administration) the incidence of adverse fetal outcomes during the at-home portion of cervical ripening is likely to be very low. With responsible use, outpatient administration of prostaglandins should be safe. Women are monitored after misoprostol administration and are not sent home if there are any concerns for fetal distress or if frequent contractions continue. Misoprostol reaches maximum blood concentration 30 minutes after oral administration and 70 to 80 minutes after vaginal administration.28 After this time, if contractions start to intensify it is likely that misoprostol has triggered spontaneous labor. In this setting, women are routinely allowed to spontaneously labor at home. One may even argue that outpatient misoprostol could lead to improved safety, as women essentially have a contraction stress test prior to spontaneous labor, and misoprostol administration as an outpatient, as opposed to as an inpatient, may allow for longer time intervals between doses, which could prevent dose stacking.

Continue to: Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening...

Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening

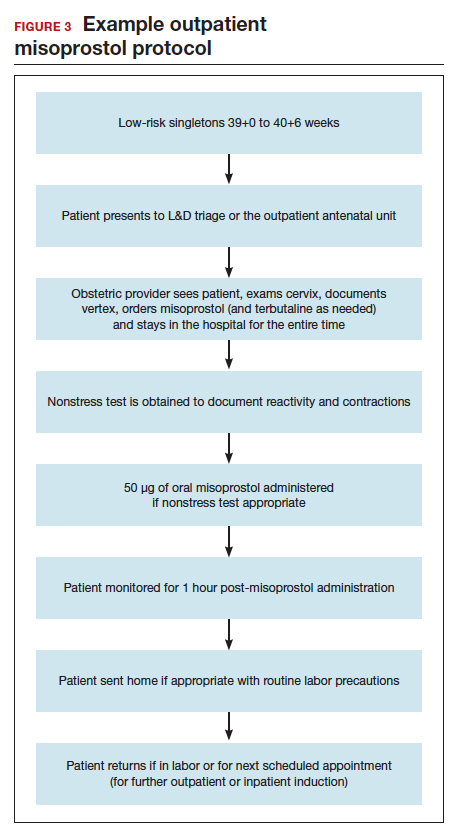

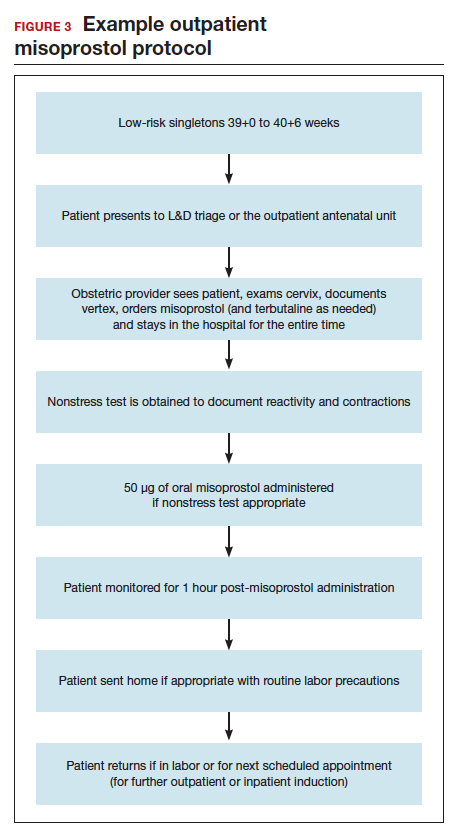

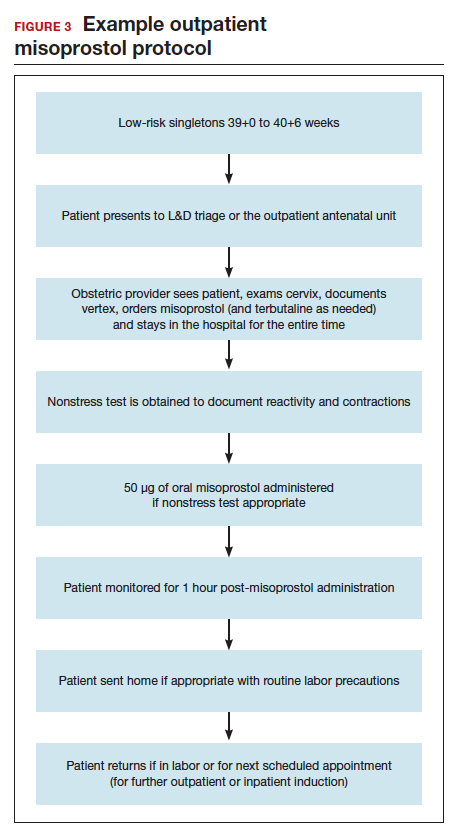

Our hospital has been conducting outpatient cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol for more th

Conclusion

While the data continue to be limited, we strongly believe there is sufficient quality evidence from a safety and efficacy perspective to support implementation and evaluation of outpatient cervical ripening protocols for low-risk pregnancies. In the setting of renewed commitments to reducing suboptimal health care costs and utilization as well as increasing patient satisfaction and control in their birthing experiences, we posit it is the responsibility of obstetricians, L&D leadership, and health care institutions to explore the implementation of outpatient cervical ripening for appropriate candidates in their settings.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Jozwiak M, Bloemenkamp KW, Kelly AJ, et al. Mechanical methods for induction of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001233.

- Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Dowswell T. Intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD003246.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, et al. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1357-1364.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107: induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397. Reaffirmed 2019.

- Sciscione AC, Bedder CL, Hoffman MK, et al. The timing of adverse events with Foley catheter preinduction cervical ripening; implications for outpatient use. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:781-786.

- Diederen M, Gommers J, Wilkinson C, et al. Safety of the balloon catheter for cervical ripening in outpatient care: complications during the period from insertion to expulsion of a balloon catheter in the process of labour induction: a systematic review. BJOG. 2018;125:1086-1095.

- McKenna DS, Duke JM. Effectiveness and infectious morbidity of outpatient cervical ripening with a Foley catheter. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:28-32.

- Kuper SG, Jauk VC, George DM, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter for induction of labor in parous women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:94-101.

- Wilkinson C, Adelson P, Turnbull D. A comparison of inpatient with outpatient balloon catheter cervical ripening: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:126.

- Kruit H, Heikinheimo O, Ulander VM, et al. Foley catheter induction of labor as an outpatient procedure. J Perinatol. 2016;36:618-622.

- Sciscione AC, Muench M, Pollock M, et al. Transcervical Foley catheter for preinduction cervical ripening in an outpatient versus inpatient setting. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 pt 1):751-756.

- Policiano C, Pimenta M, Martins D, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient cervix priming with Foley catheter: a randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:1-6.

- Ten Eikelder M, van Baaren GJ, Oude Rengerink K, et al. Comparing induction of labour with oral misoprostol or Foley catheter at term: cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised controlled multi-centre non-inferiority trial. BJOG. 2018;125:375-383.

- Henry A, Madan A, Reid R, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter versus inpatient prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour: a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:25.

- Howard K, Gerard K, Adelson P, et al. Women’s preferences for inpatient and outpatient priming for labour induction: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:330.

- Main E, LaGrew D; California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Induction of labor risks, benefits, and techniques for increasing success. June 14, 2017. https://www .cmqcc.org/resource/induction-labor-risk-benefits-and-techniques-increasing -success. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- Gaffaney CA, Saul LL, Rumney PJ, et al. Outpatient oral misoprostol for prolonged pregnancies: a pilot investigation. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:673-677.

- PonMalar J, Benjamin SJ, Abraham A, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of preinduction cervical priming with 25 µg of misoprostol in the outpatient setting to prevent formal induction of labour. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:33-38.

- Stitely ML, Browning J, Fowler M, et al. Outpatient cervical ripening with intravaginal misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 pt 1):684-688.

- McKenna DS, Ester JB, Proffitt M, et al. Misoprostol outpatient cervical ripening without subsequent induction of labor: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:579-584.

- Oboro VO, Tabowei TO. Outpatient misoprostol cervical ripening withoutsubsequent induction of labor to prevent post-term pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:628-631.

- Chang DW, Velazquez MD, Colyer M, et al. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening at term: comparison of outpatient vs. inpatient administration. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:735-739.

- Biem SR, Turnell RW, Olatunbosun O, et al. A randomized controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient labour induction with vaginal controlled-release prostaglandin-E2: effectiveness and satisfaction. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:23-31.

- Wilkinson C, Bryce R, Adelson P, et al. A randomised controlled trial of outpatient compared with inpatient cervical ripening with prostaglandin E₂ (OPRA study). BJOG. 2015;122:94-104.

- Ten Eikelder ML, van de Meent MM, Mast K, et al. Women’s experiences with and preference for induction of labor with oral misoprostol or Foley catheter at term. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:138-146.

- Tang OS, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Ho PC. Misoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99 (suppl 2):S160-S167.

Case 1 Induction at 39 weeks in a healthy nulliparous woman

A healthy 35-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 weeks 0 days and with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. She inquires about scheduling an induction of labor, noting that she read a news story about induction at 39 weeks and that it might lower her chance of having a cesarean delivery (CD).

You perform a cervical exam—she is 1 cm dilated, 3 cm long, -2 station, posterior, and firm. You sweep her membranes after obtaining verbal consent. After describing the induction process, you explain that she might be hospitalized for several days before the birth given the need for cervical ripening. “You mean I need to stay in the hospital for the entire process?” she asks incredulously.

Over the past 20 years, the percentage of patients undergoing induction of labor (IOL) has increased from 10% to 25%.1 This percentage likely will rise over time, particularly in the wake of a recent randomized controlled trial suggesting potential maternal benefits, such as reduced CD rate, for nulliparas induced at 39 weeks compared with expectant management.2 Although there have not been any changes to guidelines for timing of IOL from such professional societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) or the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, key considerations of rising IOL volume include patient experience, labor and delivery (L&D) units’ capacity and resources, and associated health care costs.

An essential part of successful induction involves patience. Induction can be a lengthy process, particularly for nulliparas with unripe cervices. Cervical ripening is a necessary component of successful labor induction, whether achieved mechanically or pharmacologically with synthetic prostaglandins, and it has been shown to lower the chance of CD.3,4 However, achieving a ripe cervix is often the lengthiest part of an induction, and not uncommonly consumes 12 to 24 hours or more of inpatient time. Investigators have sought ways to make this process more expeditious. For example, the FOR-MOMI trial demonstrated that the induction-to-delivery time was several hours shorter when cervical ripening combined mechanical and pharmacologic approaches (Foley balloon plus misoprostol), compared with either method alone, without any increase in maternal or fetal complication rates.5

Better yet, what if admission to the L&D unit for IOL at term could be deferred until the cervix is ripe? A number of hospitals in the United States have successfully introduced outpatient cervical ripening, and several small observational and randomized controlled trials have reported good results in terms of safety, efficacy and time saved, and patient experience. Here, we will make the case that outpatient cervical ripening should be the standard of care for low-risk pregnancies.

Mechanical cervical ripening

Safety

Although data are limited on the safety, the authors of an ACOG Practice Bulletin suggest that, based on the available evidence of mechanical ripening in an inpatient setting, it is also appropriate in the outpatient setting.6 Unlike cervical ripening using prostaglandins, mechanical ripening is not associated with tachysystole, fetal intolerance of labor, or meconium staining.3 A cohort study of nearly 2,000 low-risk patients who underwent Foley catheter placement for cervical ripening using an outpatient protocol but monitored overnight as inpatients and evaluated for adverse outcomes found no CD for fetal distress, vaginal bleeding, placental abruption, or intrapartum stillbirth.7 The authors posited that, given this safety profile in the inpatient setting, that mechanical cervical ripening with a Foley catheter would be appropriate for outpatient use in low-risk populations. Other systematic reviews have been reassuring as well, with exceedingly low complication rates during inpatient mechanical cervical ripening.8 These data advocate for the evaluation of cervical ripening in the outpatient setting.

The evidence for outpatient mechanical ripening, although again limited, also has demonstrated safety. There does not appear to be an increased rate of maternal or neonatal complications, including infectious morbidity, postpartum hemorrhage, CD, operative vaginal delivery, or fetal distress.9-12

Continue to: Efficacy and length-of-stay...

Efficacy and length-of-stay

Efficacy also generally has been shown to be similar when mechanical methods are used in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Small randomized trials of outpatient versus inpatient Foley catheter ripening have shown decreased length of stay (by 10 to 13 hours) and similar or less oxytocin use in the outpatient groups, as well as similar Bishop scores after cervical ripening and no difference in maternal or fetal outcomes.9,11,13,14

One major concern with increasing IOL prevalence is the availability of hospital resources and the associated health care costs, given the known increased length of inpatient stay due to cervical ripening time. Admission to an L&D unit is resource intensive; the costs are similar to admission to an intensive care unit in many hospitals given its level of acuity and high nurse/patient ratio. However, given the safety of outpatient mechanical cervical ripening described above, we argue that routinely admitting low-risk patients for mechanical ripening constitutes a suboptimal use of costly resources.

Indeed, data suggest significant inpatient time savings if cervical ripening can be accomplished prior to admission. A cost-effectiveness analysis in the Netherlands demonstrated a nearly 1,000-euro decrease in cost per induction when Foley catheter induction was done on an outpatient basis.15 Interestingly, a recent trial confined to multiparas found no differences in hospital time when comparing outpatient ripening with Foley balloon alone with inpatient ripening with Foley balloon plus simultaneous oxytocin.10 This certainly merits further study, but it may be that the largest time- and cost-savings are among nulliparas.

Patient preferences

Relatively few studies specifically have addressed patient experiences with outpatient versus inpatient mechanical cervical ripening. Outpatient cervical ripening may provide patients with the benefits of being in the comfort of their own homes with their preferred support persons, increased mobility, more bodily autonomy, and satisfaction with their birthing process.

In a pilot trial involving 48 women, inpatient was compared with outpatient cervical ripening using a Foley balloon. Those in the outpatient group reported getting more rest, feeling less isolated, and having enough privacy. However, participants in both groups were equally satisfied and equally likely to recommend their method of induction to others.11 Another study comparing outpatient versus inpatient Foley balloon cervical ripening found that 85% of patients who underwent outpatient ripening were satisfied with the induction method; however, no query or comparison was done with the inpatient group.12 A trial comparing outpatient mechanical cervical ripening with inpatient misoprostol found that outpatient participants reported several hours more sleep and less pain.16 And in a discrete choice experiment of British gravidas, participants favored the option of outpatient cervical ripening, even if it meant an extra 1.4 trips to the hospital and over an hour of extra travel time.17

While these preliminary findings provide some insight that patients may prefer an outpatient approach to cervical ripening, more studies are needed to fully evaluate patient desires.

Continue to: Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening...

Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening

Most patients undergoing scheduled IOL are reasonable candidates for outpatient cervical ripening based on safety and efficacy. By definition, scheduling in advance implies that the provider has determined that outpatient management is reasonable until that date, and the plan for outpatient ripening need not prolong this period.

FIGURES 1 and 2 show protocols for our 2 hospital centers, which regularly allow for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening. In the process of protocol development, we identified absolute and relative contraindications to determine appropriate candidates. We exclude women who require inpatient management of medical or obstetric conditions (for example, women with severe preeclampsia or any condition requiring continuous fetal monitoring). We also do not routinely recommend outpatient cervical ripening to patients who do not have the necessary social conditions to make this process as safe as possible (including stable housing, reliable transportation, and a support person), although this occurs with some exceptions depending on individual patient situations.

Some examples of ideal candidates for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening include those undergoing elective or routine prolonged gestation inductions, or inductions for well-controlled, stable conditions (chronic hypertension and gestational diabetes). At one center, after thorough counseling and assessment, outpatient cervical ripening is also offered to patients with mild risk factors, including twins, prior low transverse CD, stable preeclampsia without severe features, isolated oligohydramnios with otherwise reassuring fetal status, and other similar conditions.

After mechanical cervical ripening placement (either Foley catheter or mechanical dilators), the clinician completes a postprocedure safety checklist and detailed procedure documentation, including number and type of foreign bodies placed. If there are any concerns regarding maternal or fetal well-being, the patient is sent to L&D for evaluation. If the procedure was tolerated well, the patient is discharged home, after a reactive postprocedure nonstress test is done, with detailed instructions for self-care, as well as with a list of symptoms that warrant prompt evaluation prior to scheduled induction time. In a large California hospital group following a similar protocol, only about 5% of women presented in labor before their scheduled induction.18

Case 2 Cervical ripening for labor preparation in low-risk pregnancy

A 32-year-old woman (G1P0) with an uncomplicated pregnancy at 40 weeks and 3 days presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. Her vital signs are normal, and her fetus is vertex with an estimated fetal weight of 7.5 lb by Leopald’s maneuvers. You perform a cervical exam and find that her cervix is closed, long, and posterior.

You discuss with her your recommendation for induction of labor by 41 weeks, and she agrees. You also discuss the need for cervical ripening and recommend misoprostol given her closed cervix. You explain that several doses may be needed to get her cervix ready for labor, and she asks, “Do I have to stay in the hospital that whole time?”

Pharmacologic cervical ripening

Efficacy

There are multiple pharmacologic agents that can be used for ripening an unfavorable cervix. The main agents used in the United States are prostaglandins, either PGE1 (oral or vaginal misoprostol) or PGE2 in a gel or sustained-release vaginal insert (dinoprostone).

Outpatient misoprostol to avoid labor induction. Many studies have looked at outpatient misoprostol use as a “prophylactic measure” (to prevent the need for labor induction). For example, Gaffaney and colleagues showed that administering outpatient oral misoprostol (100 µg every 24 hours for up to 3 doses) after 40 weeks’ gestation to women with an unfavorable cervix significantly decreased the time to delivery by a day and a half.19 Similarly, PonMalar and colleagues demonstrated that administering 25 µg of vaginal misoprostol in a single dose as an outpatient after stripping the membranes significantly reduced time to delivery by 2 days.20 And Stitely and colleagues found a significant reduction in the need for labor induction with the use of outpatient vaginal misoprostol. They administered up to 2 doses of misoprostol 25 µg vaginally every 24 hours for the 48 hours prior to a scheduled postdates induction and found a large reduction in the need for labor induction (11% vs 85%; P<.01).21

Continue to: Multiple protocols and regimens...

Multiple protocols and regimens have been studied but, overall, the findings suggest that administering outpatient misoprostol may shorten the time interval to spontaneous labor and decrease the need for a formal labor induction.19-23

Inpatient compared with outpatient prostaglandin use. These trials of “prophylactic” misoprostol generally have compared outpatient administration of misoprostol with placebo. Prostaglandins are one of the most common methods of inpatient cervical ripening, so what about comparisons of inpatient cervical ripening with outpatient prostaglandin administration? There are a handful of studies that make this comparison.

Chang and colleagues looked retrospectively at inpatient and outpatient misoprostol and found that outpatient administration saved 3 to 5 hours on labor and delivery.24 Biem and colleagues randomly assigned women to either inpatient cervical ripening with PGE2 intravaginal inserts or 1 hour of inpatient monitoring after PGE2 administration and then outpatient discharge until the onset of labor or for a nonstress test at 12 hours. They found that those who underwent outpatient ripening spent 8 hours less on labor and delivery and were more highly satisfied with the initial 12 hours of labor induction experience (56% vs 39%; P<.01).25

The largest randomized controlled trial conducted to study outpatient prostaglandin use was the OPRA study (involving 827 women). Investigators compared inpatient to outpatient PGE2 intravaginal gel.26 The primary outcome was total oxytocin administration, which was not different between groups. The study was underpowered, however, as 50% of women labored spontaneously postrandomization. But in the outpatient arm, less than half of the women required additional inpatient ripening, and nearly 40% returned in spontaneous labor, suggesting that outpatient prostaglandin administration may indeed save women a significant amount of time on labor and delivery.

Safety

The safety of outpatient administration of prostaglandins is the biggest concern, especially since, when prostaglandins are compared to outpatient Foley catheter use, Foleys are overall associated with less tachysystole, fetal intolerance, and meconium-stained fluid.3 Foley catheter use for cervical ripening may not be an appropriate choice for all patients, however. For instance, our case patient has a closed cervix, which could make Foley insertion uncomfortable or even impossible. Misoprostol use also offers the potential for flexibility in cervical ripening protocols as patients need not return for Foley balloon removal and indeed labor induction need not take place immediately after administration of misoprostol.

Patients also may prefer outpatient cervical ripening with misoprostol over a Foley. There are some data to suggest that women, overall, have a preference toward prostaglandins; in the PROBAAT-II trial, which compared inpatient oral misoprostol to Foley catheter for cervical ripening, 12% of women in the Foley arm would have preferred another method of induction (vs 6% in the misoprostol arm; P = .02).27 This preference may be magnified in an outpatient setting.

But, again, is outpatient administration of prostaglandins safe? The published trials thus far have not reported an increase in out-of-hospital deliveries or adverse fetal outcomes. However, studies have been of limited size to see more rare outcomes. Unfortunately, an adequately powered study to demonstrate safety is likely never to be accomplished, given that if used responsibly (in low-risk patients with adequate monitoring after administration) the incidence of adverse fetal outcomes during the at-home portion of cervical ripening is likely to be very low. With responsible use, outpatient administration of prostaglandins should be safe. Women are monitored after misoprostol administration and are not sent home if there are any concerns for fetal distress or if frequent contractions continue. Misoprostol reaches maximum blood concentration 30 minutes after oral administration and 70 to 80 minutes after vaginal administration.28 After this time, if contractions start to intensify it is likely that misoprostol has triggered spontaneous labor. In this setting, women are routinely allowed to spontaneously labor at home. One may even argue that outpatient misoprostol could lead to improved safety, as women essentially have a contraction stress test prior to spontaneous labor, and misoprostol administration as an outpatient, as opposed to as an inpatient, may allow for longer time intervals between doses, which could prevent dose stacking.

Continue to: Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening...

Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening

Our hospital has been conducting outpatient cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol for more th

Conclusion

While the data continue to be limited, we strongly believe there is sufficient quality evidence from a safety and efficacy perspective to support implementation and evaluation of outpatient cervical ripening protocols for low-risk pregnancies. In the setting of renewed commitments to reducing suboptimal health care costs and utilization as well as increasing patient satisfaction and control in their birthing experiences, we posit it is the responsibility of obstetricians, L&D leadership, and health care institutions to explore the implementation of outpatient cervical ripening for appropriate candidates in their settings.

Case 1 Induction at 39 weeks in a healthy nulliparous woman

A healthy 35-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 weeks 0 days and with an uncomplicated pregnancy presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. She inquires about scheduling an induction of labor, noting that she read a news story about induction at 39 weeks and that it might lower her chance of having a cesarean delivery (CD).

You perform a cervical exam—she is 1 cm dilated, 3 cm long, -2 station, posterior, and firm. You sweep her membranes after obtaining verbal consent. After describing the induction process, you explain that she might be hospitalized for several days before the birth given the need for cervical ripening. “You mean I need to stay in the hospital for the entire process?” she asks incredulously.

Over the past 20 years, the percentage of patients undergoing induction of labor (IOL) has increased from 10% to 25%.1 This percentage likely will rise over time, particularly in the wake of a recent randomized controlled trial suggesting potential maternal benefits, such as reduced CD rate, for nulliparas induced at 39 weeks compared with expectant management.2 Although there have not been any changes to guidelines for timing of IOL from such professional societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) or the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, key considerations of rising IOL volume include patient experience, labor and delivery (L&D) units’ capacity and resources, and associated health care costs.

An essential part of successful induction involves patience. Induction can be a lengthy process, particularly for nulliparas with unripe cervices. Cervical ripening is a necessary component of successful labor induction, whether achieved mechanically or pharmacologically with synthetic prostaglandins, and it has been shown to lower the chance of CD.3,4 However, achieving a ripe cervix is often the lengthiest part of an induction, and not uncommonly consumes 12 to 24 hours or more of inpatient time. Investigators have sought ways to make this process more expeditious. For example, the FOR-MOMI trial demonstrated that the induction-to-delivery time was several hours shorter when cervical ripening combined mechanical and pharmacologic approaches (Foley balloon plus misoprostol), compared with either method alone, without any increase in maternal or fetal complication rates.5

Better yet, what if admission to the L&D unit for IOL at term could be deferred until the cervix is ripe? A number of hospitals in the United States have successfully introduced outpatient cervical ripening, and several small observational and randomized controlled trials have reported good results in terms of safety, efficacy and time saved, and patient experience. Here, we will make the case that outpatient cervical ripening should be the standard of care for low-risk pregnancies.

Mechanical cervical ripening

Safety

Although data are limited on the safety, the authors of an ACOG Practice Bulletin suggest that, based on the available evidence of mechanical ripening in an inpatient setting, it is also appropriate in the outpatient setting.6 Unlike cervical ripening using prostaglandins, mechanical ripening is not associated with tachysystole, fetal intolerance of labor, or meconium staining.3 A cohort study of nearly 2,000 low-risk patients who underwent Foley catheter placement for cervical ripening using an outpatient protocol but monitored overnight as inpatients and evaluated for adverse outcomes found no CD for fetal distress, vaginal bleeding, placental abruption, or intrapartum stillbirth.7 The authors posited that, given this safety profile in the inpatient setting, that mechanical cervical ripening with a Foley catheter would be appropriate for outpatient use in low-risk populations. Other systematic reviews have been reassuring as well, with exceedingly low complication rates during inpatient mechanical cervical ripening.8 These data advocate for the evaluation of cervical ripening in the outpatient setting.

The evidence for outpatient mechanical ripening, although again limited, also has demonstrated safety. There does not appear to be an increased rate of maternal or neonatal complications, including infectious morbidity, postpartum hemorrhage, CD, operative vaginal delivery, or fetal distress.9-12

Continue to: Efficacy and length-of-stay...

Efficacy and length-of-stay

Efficacy also generally has been shown to be similar when mechanical methods are used in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Small randomized trials of outpatient versus inpatient Foley catheter ripening have shown decreased length of stay (by 10 to 13 hours) and similar or less oxytocin use in the outpatient groups, as well as similar Bishop scores after cervical ripening and no difference in maternal or fetal outcomes.9,11,13,14

One major concern with increasing IOL prevalence is the availability of hospital resources and the associated health care costs, given the known increased length of inpatient stay due to cervical ripening time. Admission to an L&D unit is resource intensive; the costs are similar to admission to an intensive care unit in many hospitals given its level of acuity and high nurse/patient ratio. However, given the safety of outpatient mechanical cervical ripening described above, we argue that routinely admitting low-risk patients for mechanical ripening constitutes a suboptimal use of costly resources.

Indeed, data suggest significant inpatient time savings if cervical ripening can be accomplished prior to admission. A cost-effectiveness analysis in the Netherlands demonstrated a nearly 1,000-euro decrease in cost per induction when Foley catheter induction was done on an outpatient basis.15 Interestingly, a recent trial confined to multiparas found no differences in hospital time when comparing outpatient ripening with Foley balloon alone with inpatient ripening with Foley balloon plus simultaneous oxytocin.10 This certainly merits further study, but it may be that the largest time- and cost-savings are among nulliparas.

Patient preferences

Relatively few studies specifically have addressed patient experiences with outpatient versus inpatient mechanical cervical ripening. Outpatient cervical ripening may provide patients with the benefits of being in the comfort of their own homes with their preferred support persons, increased mobility, more bodily autonomy, and satisfaction with their birthing process.

In a pilot trial involving 48 women, inpatient was compared with outpatient cervical ripening using a Foley balloon. Those in the outpatient group reported getting more rest, feeling less isolated, and having enough privacy. However, participants in both groups were equally satisfied and equally likely to recommend their method of induction to others.11 Another study comparing outpatient versus inpatient Foley balloon cervical ripening found that 85% of patients who underwent outpatient ripening were satisfied with the induction method; however, no query or comparison was done with the inpatient group.12 A trial comparing outpatient mechanical cervical ripening with inpatient misoprostol found that outpatient participants reported several hours more sleep and less pain.16 And in a discrete choice experiment of British gravidas, participants favored the option of outpatient cervical ripening, even if it meant an extra 1.4 trips to the hospital and over an hour of extra travel time.17

While these preliminary findings provide some insight that patients may prefer an outpatient approach to cervical ripening, more studies are needed to fully evaluate patient desires.

Continue to: Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening...

Our approach to mechanical cervical ripening

Most patients undergoing scheduled IOL are reasonable candidates for outpatient cervical ripening based on safety and efficacy. By definition, scheduling in advance implies that the provider has determined that outpatient management is reasonable until that date, and the plan for outpatient ripening need not prolong this period.

FIGURES 1 and 2 show protocols for our 2 hospital centers, which regularly allow for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening. In the process of protocol development, we identified absolute and relative contraindications to determine appropriate candidates. We exclude women who require inpatient management of medical or obstetric conditions (for example, women with severe preeclampsia or any condition requiring continuous fetal monitoring). We also do not routinely recommend outpatient cervical ripening to patients who do not have the necessary social conditions to make this process as safe as possible (including stable housing, reliable transportation, and a support person), although this occurs with some exceptions depending on individual patient situations.

Some examples of ideal candidates for outpatient mechanical cervical ripening include those undergoing elective or routine prolonged gestation inductions, or inductions for well-controlled, stable conditions (chronic hypertension and gestational diabetes). At one center, after thorough counseling and assessment, outpatient cervical ripening is also offered to patients with mild risk factors, including twins, prior low transverse CD, stable preeclampsia without severe features, isolated oligohydramnios with otherwise reassuring fetal status, and other similar conditions.

After mechanical cervical ripening placement (either Foley catheter or mechanical dilators), the clinician completes a postprocedure safety checklist and detailed procedure documentation, including number and type of foreign bodies placed. If there are any concerns regarding maternal or fetal well-being, the patient is sent to L&D for evaluation. If the procedure was tolerated well, the patient is discharged home, after a reactive postprocedure nonstress test is done, with detailed instructions for self-care, as well as with a list of symptoms that warrant prompt evaluation prior to scheduled induction time. In a large California hospital group following a similar protocol, only about 5% of women presented in labor before their scheduled induction.18

Case 2 Cervical ripening for labor preparation in low-risk pregnancy

A 32-year-old woman (G1P0) with an uncomplicated pregnancy at 40 weeks and 3 days presents to your office for a routine prenatal visit. Her vital signs are normal, and her fetus is vertex with an estimated fetal weight of 7.5 lb by Leopald’s maneuvers. You perform a cervical exam and find that her cervix is closed, long, and posterior.

You discuss with her your recommendation for induction of labor by 41 weeks, and she agrees. You also discuss the need for cervical ripening and recommend misoprostol given her closed cervix. You explain that several doses may be needed to get her cervix ready for labor, and she asks, “Do I have to stay in the hospital that whole time?”

Pharmacologic cervical ripening

Efficacy

There are multiple pharmacologic agents that can be used for ripening an unfavorable cervix. The main agents used in the United States are prostaglandins, either PGE1 (oral or vaginal misoprostol) or PGE2 in a gel or sustained-release vaginal insert (dinoprostone).

Outpatient misoprostol to avoid labor induction. Many studies have looked at outpatient misoprostol use as a “prophylactic measure” (to prevent the need for labor induction). For example, Gaffaney and colleagues showed that administering outpatient oral misoprostol (100 µg every 24 hours for up to 3 doses) after 40 weeks’ gestation to women with an unfavorable cervix significantly decreased the time to delivery by a day and a half.19 Similarly, PonMalar and colleagues demonstrated that administering 25 µg of vaginal misoprostol in a single dose as an outpatient after stripping the membranes significantly reduced time to delivery by 2 days.20 And Stitely and colleagues found a significant reduction in the need for labor induction with the use of outpatient vaginal misoprostol. They administered up to 2 doses of misoprostol 25 µg vaginally every 24 hours for the 48 hours prior to a scheduled postdates induction and found a large reduction in the need for labor induction (11% vs 85%; P<.01).21

Continue to: Multiple protocols and regimens...

Multiple protocols and regimens have been studied but, overall, the findings suggest that administering outpatient misoprostol may shorten the time interval to spontaneous labor and decrease the need for a formal labor induction.19-23

Inpatient compared with outpatient prostaglandin use. These trials of “prophylactic” misoprostol generally have compared outpatient administration of misoprostol with placebo. Prostaglandins are one of the most common methods of inpatient cervical ripening, so what about comparisons of inpatient cervical ripening with outpatient prostaglandin administration? There are a handful of studies that make this comparison.

Chang and colleagues looked retrospectively at inpatient and outpatient misoprostol and found that outpatient administration saved 3 to 5 hours on labor and delivery.24 Biem and colleagues randomly assigned women to either inpatient cervical ripening with PGE2 intravaginal inserts or 1 hour of inpatient monitoring after PGE2 administration and then outpatient discharge until the onset of labor or for a nonstress test at 12 hours. They found that those who underwent outpatient ripening spent 8 hours less on labor and delivery and were more highly satisfied with the initial 12 hours of labor induction experience (56% vs 39%; P<.01).25

The largest randomized controlled trial conducted to study outpatient prostaglandin use was the OPRA study (involving 827 women). Investigators compared inpatient to outpatient PGE2 intravaginal gel.26 The primary outcome was total oxytocin administration, which was not different between groups. The study was underpowered, however, as 50% of women labored spontaneously postrandomization. But in the outpatient arm, less than half of the women required additional inpatient ripening, and nearly 40% returned in spontaneous labor, suggesting that outpatient prostaglandin administration may indeed save women a significant amount of time on labor and delivery.

Safety

The safety of outpatient administration of prostaglandins is the biggest concern, especially since, when prostaglandins are compared to outpatient Foley catheter use, Foleys are overall associated with less tachysystole, fetal intolerance, and meconium-stained fluid.3 Foley catheter use for cervical ripening may not be an appropriate choice for all patients, however. For instance, our case patient has a closed cervix, which could make Foley insertion uncomfortable or even impossible. Misoprostol use also offers the potential for flexibility in cervical ripening protocols as patients need not return for Foley balloon removal and indeed labor induction need not take place immediately after administration of misoprostol.

Patients also may prefer outpatient cervical ripening with misoprostol over a Foley. There are some data to suggest that women, overall, have a preference toward prostaglandins; in the PROBAAT-II trial, which compared inpatient oral misoprostol to Foley catheter for cervical ripening, 12% of women in the Foley arm would have preferred another method of induction (vs 6% in the misoprostol arm; P = .02).27 This preference may be magnified in an outpatient setting.

But, again, is outpatient administration of prostaglandins safe? The published trials thus far have not reported an increase in out-of-hospital deliveries or adverse fetal outcomes. However, studies have been of limited size to see more rare outcomes. Unfortunately, an adequately powered study to demonstrate safety is likely never to be accomplished, given that if used responsibly (in low-risk patients with adequate monitoring after administration) the incidence of adverse fetal outcomes during the at-home portion of cervical ripening is likely to be very low. With responsible use, outpatient administration of prostaglandins should be safe. Women are monitored after misoprostol administration and are not sent home if there are any concerns for fetal distress or if frequent contractions continue. Misoprostol reaches maximum blood concentration 30 minutes after oral administration and 70 to 80 minutes after vaginal administration.28 After this time, if contractions start to intensify it is likely that misoprostol has triggered spontaneous labor. In this setting, women are routinely allowed to spontaneously labor at home. One may even argue that outpatient misoprostol could lead to improved safety, as women essentially have a contraction stress test prior to spontaneous labor, and misoprostol administration as an outpatient, as opposed to as an inpatient, may allow for longer time intervals between doses, which could prevent dose stacking.

Continue to: Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening...

Our approach to pharmacologic cervical ripening

Our hospital has been conducting outpatient cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol for more th

Conclusion

While the data continue to be limited, we strongly believe there is sufficient quality evidence from a safety and efficacy perspective to support implementation and evaluation of outpatient cervical ripening protocols for low-risk pregnancies. In the setting of renewed commitments to reducing suboptimal health care costs and utilization as well as increasing patient satisfaction and control in their birthing experiences, we posit it is the responsibility of obstetricians, L&D leadership, and health care institutions to explore the implementation of outpatient cervical ripening for appropriate candidates in their settings.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Jozwiak M, Bloemenkamp KW, Kelly AJ, et al. Mechanical methods for induction of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001233.

- Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Dowswell T. Intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD003246.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, et al. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1357-1364.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107: induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397. Reaffirmed 2019.

- Sciscione AC, Bedder CL, Hoffman MK, et al. The timing of adverse events with Foley catheter preinduction cervical ripening; implications for outpatient use. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:781-786.

- Diederen M, Gommers J, Wilkinson C, et al. Safety of the balloon catheter for cervical ripening in outpatient care: complications during the period from insertion to expulsion of a balloon catheter in the process of labour induction: a systematic review. BJOG. 2018;125:1086-1095.

- McKenna DS, Duke JM. Effectiveness and infectious morbidity of outpatient cervical ripening with a Foley catheter. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:28-32.

- Kuper SG, Jauk VC, George DM, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter for induction of labor in parous women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:94-101.

- Wilkinson C, Adelson P, Turnbull D. A comparison of inpatient with outpatient balloon catheter cervical ripening: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:126.

- Kruit H, Heikinheimo O, Ulander VM, et al. Foley catheter induction of labor as an outpatient procedure. J Perinatol. 2016;36:618-622.

- Sciscione AC, Muench M, Pollock M, et al. Transcervical Foley catheter for preinduction cervical ripening in an outpatient versus inpatient setting. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 pt 1):751-756.

- Policiano C, Pimenta M, Martins D, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient cervix priming with Foley catheter: a randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:1-6.

- Ten Eikelder M, van Baaren GJ, Oude Rengerink K, et al. Comparing induction of labour with oral misoprostol or Foley catheter at term: cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised controlled multi-centre non-inferiority trial. BJOG. 2018;125:375-383.

- Henry A, Madan A, Reid R, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter versus inpatient prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour: a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:25.

- Howard K, Gerard K, Adelson P, et al. Women’s preferences for inpatient and outpatient priming for labour induction: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:330.

- Main E, LaGrew D; California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Induction of labor risks, benefits, and techniques for increasing success. June 14, 2017. https://www .cmqcc.org/resource/induction-labor-risk-benefits-and-techniques-increasing -success. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- Gaffaney CA, Saul LL, Rumney PJ, et al. Outpatient oral misoprostol for prolonged pregnancies: a pilot investigation. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:673-677.

- PonMalar J, Benjamin SJ, Abraham A, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of preinduction cervical priming with 25 µg of misoprostol in the outpatient setting to prevent formal induction of labour. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:33-38.

- Stitely ML, Browning J, Fowler M, et al. Outpatient cervical ripening with intravaginal misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 pt 1):684-688.

- McKenna DS, Ester JB, Proffitt M, et al. Misoprostol outpatient cervical ripening without subsequent induction of labor: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:579-584.

- Oboro VO, Tabowei TO. Outpatient misoprostol cervical ripening withoutsubsequent induction of labor to prevent post-term pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:628-631.

- Chang DW, Velazquez MD, Colyer M, et al. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening at term: comparison of outpatient vs. inpatient administration. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:735-739.

- Biem SR, Turnell RW, Olatunbosun O, et al. A randomized controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient labour induction with vaginal controlled-release prostaglandin-E2: effectiveness and satisfaction. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:23-31.

- Wilkinson C, Bryce R, Adelson P, et al. A randomised controlled trial of outpatient compared with inpatient cervical ripening with prostaglandin E₂ (OPRA study). BJOG. 2015;122:94-104.

- Ten Eikelder ML, van de Meent MM, Mast K, et al. Women’s experiences with and preference for induction of labor with oral misoprostol or Foley catheter at term. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:138-146.

- Tang OS, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Ho PC. Misoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99 (suppl 2):S160-S167.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Jozwiak M, Bloemenkamp KW, Kelly AJ, et al. Mechanical methods for induction of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001233.

- Alfirevic Z, Kelly AJ, Dowswell T. Intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD003246.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, et al. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1357-1364.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107: induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397. Reaffirmed 2019.

- Sciscione AC, Bedder CL, Hoffman MK, et al. The timing of adverse events with Foley catheter preinduction cervical ripening; implications for outpatient use. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:781-786.

- Diederen M, Gommers J, Wilkinson C, et al. Safety of the balloon catheter for cervical ripening in outpatient care: complications during the period from insertion to expulsion of a balloon catheter in the process of labour induction: a systematic review. BJOG. 2018;125:1086-1095.

- McKenna DS, Duke JM. Effectiveness and infectious morbidity of outpatient cervical ripening with a Foley catheter. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:28-32.

- Kuper SG, Jauk VC, George DM, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter for induction of labor in parous women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:94-101.

- Wilkinson C, Adelson P, Turnbull D. A comparison of inpatient with outpatient balloon catheter cervical ripening: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:126.

- Kruit H, Heikinheimo O, Ulander VM, et al. Foley catheter induction of labor as an outpatient procedure. J Perinatol. 2016;36:618-622.

- Sciscione AC, Muench M, Pollock M, et al. Transcervical Foley catheter for preinduction cervical ripening in an outpatient versus inpatient setting. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 pt 1):751-756.

- Policiano C, Pimenta M, Martins D, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient cervix priming with Foley catheter: a randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:1-6.

- Ten Eikelder M, van Baaren GJ, Oude Rengerink K, et al. Comparing induction of labour with oral misoprostol or Foley catheter at term: cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised controlled multi-centre non-inferiority trial. BJOG. 2018;125:375-383.

- Henry A, Madan A, Reid R, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter versus inpatient prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour: a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:25.