User login

Firm Exophytic Tumor on the Shin

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

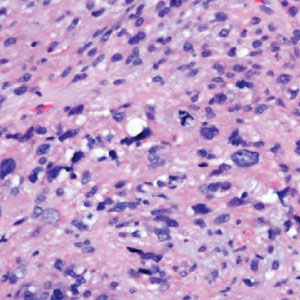

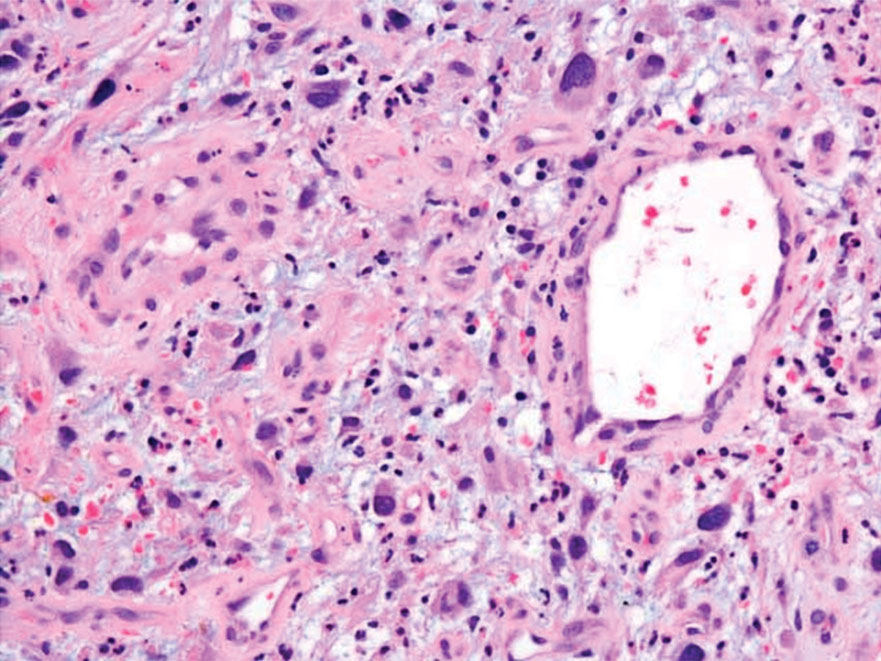

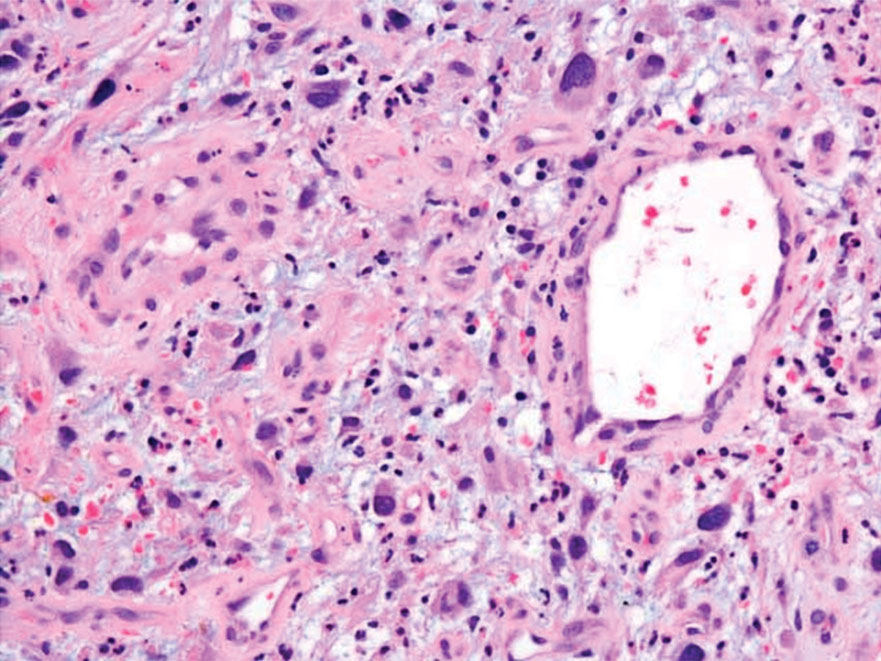

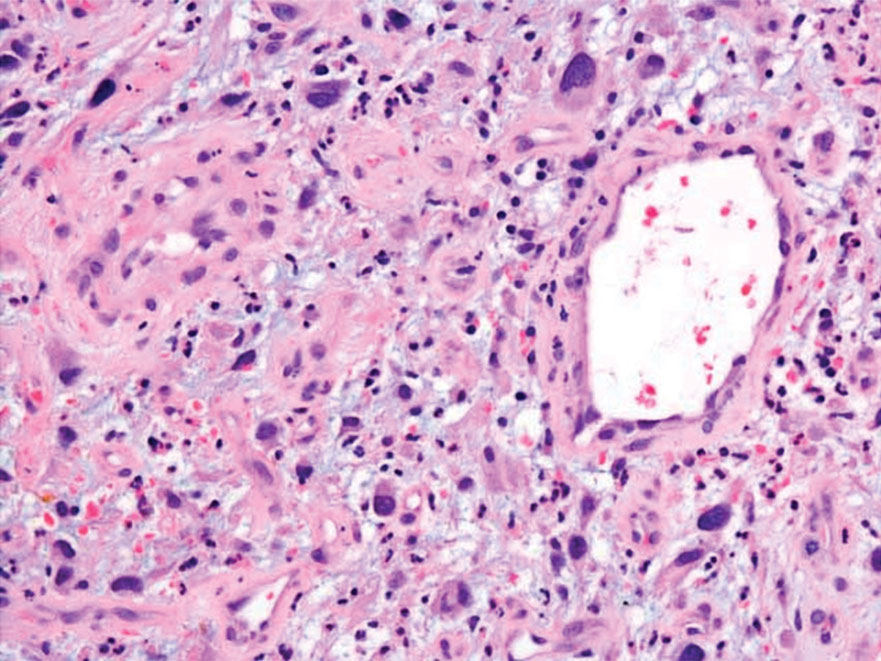

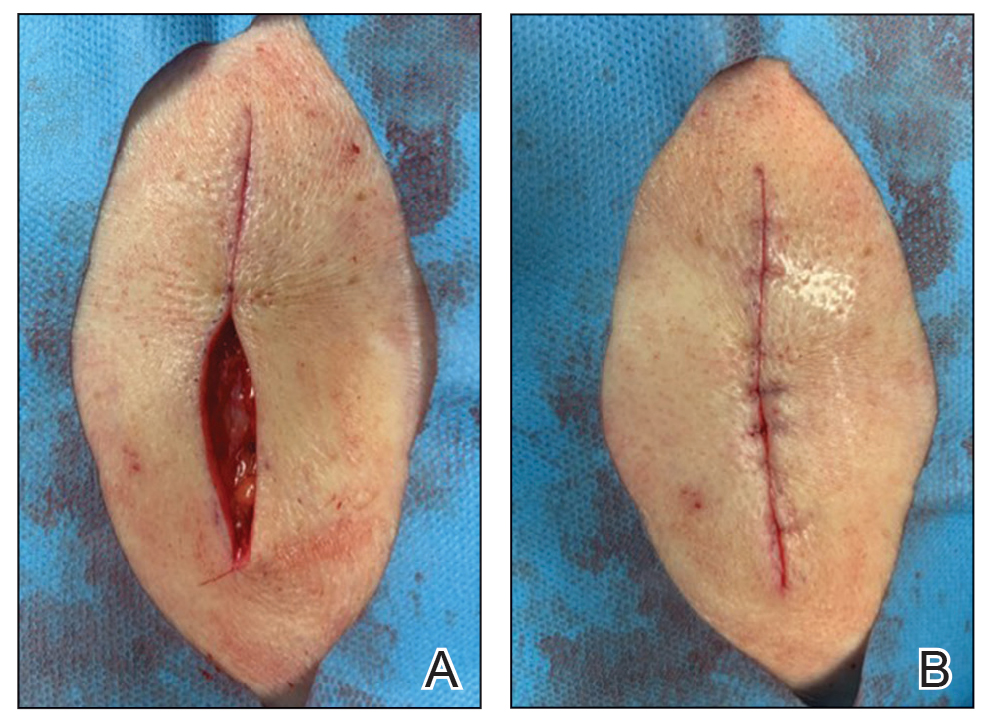

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

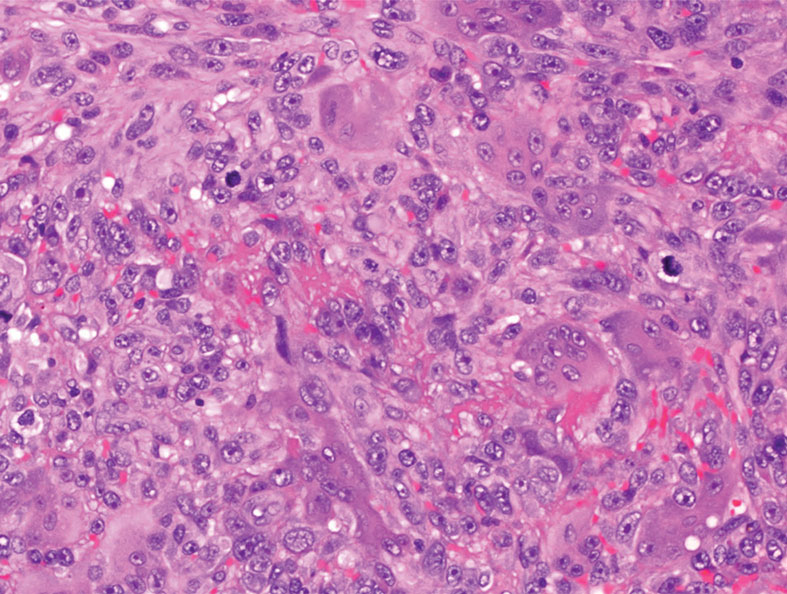

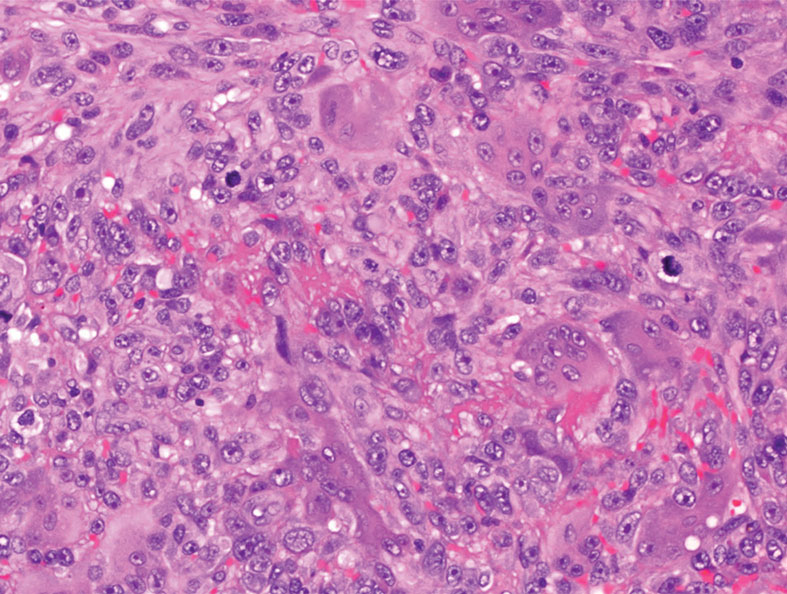

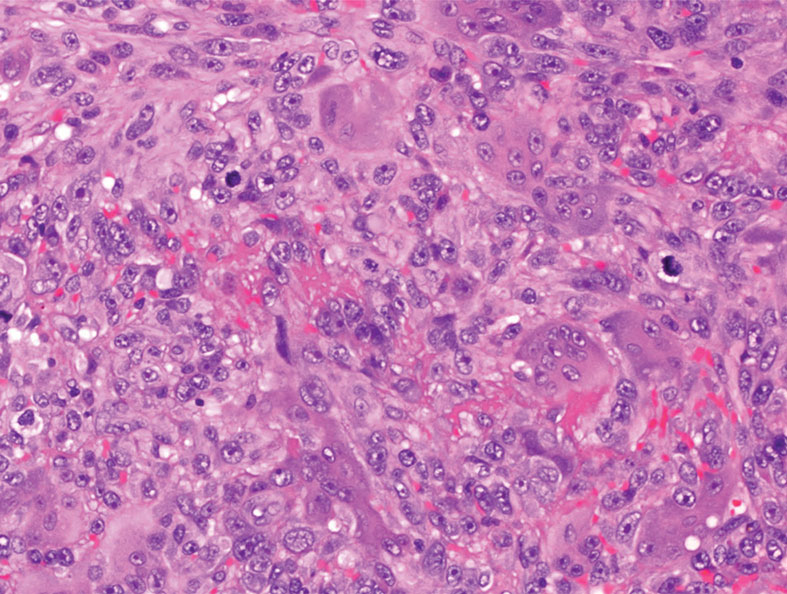

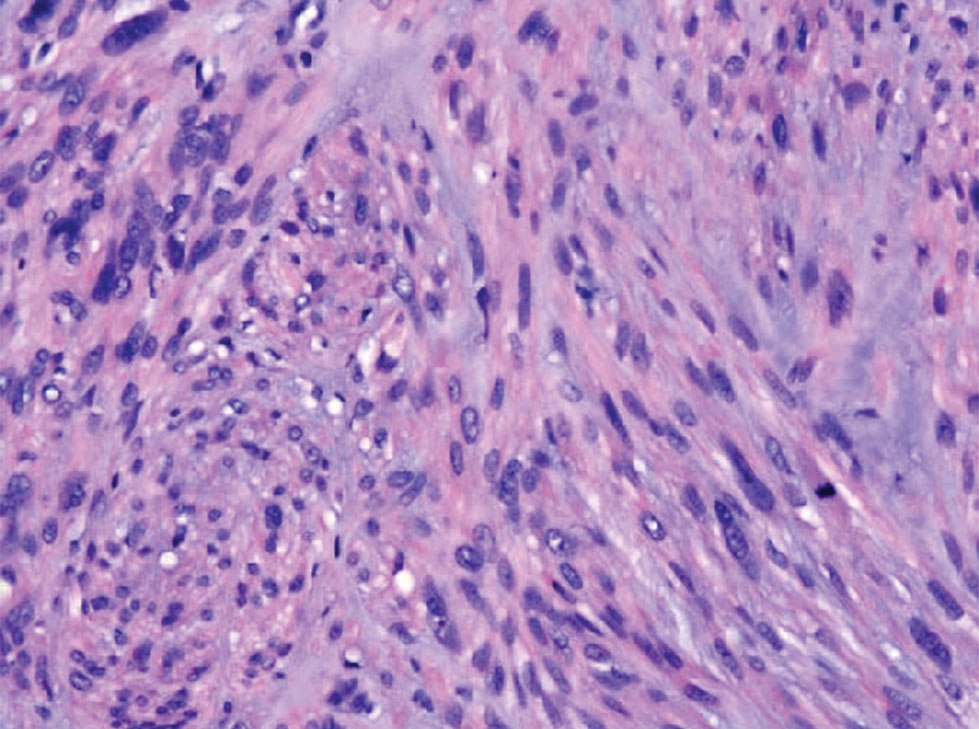

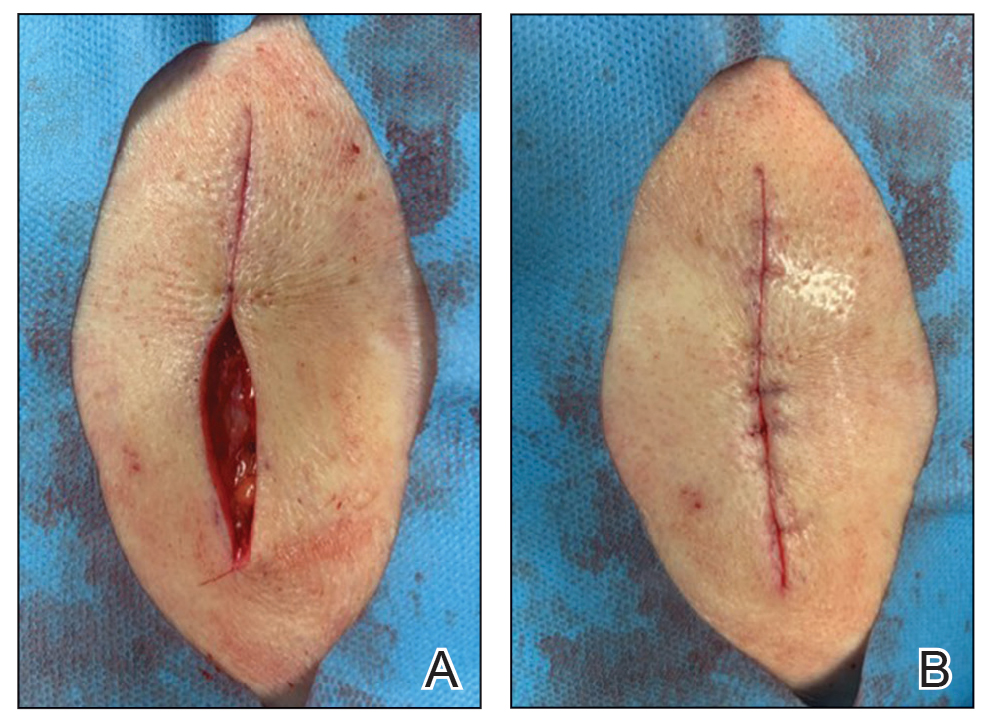

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

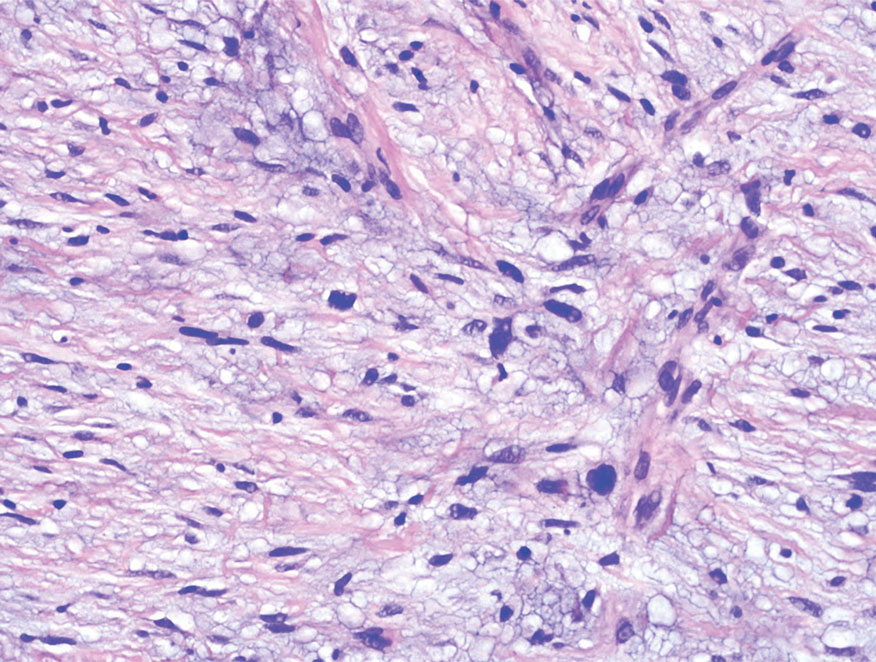

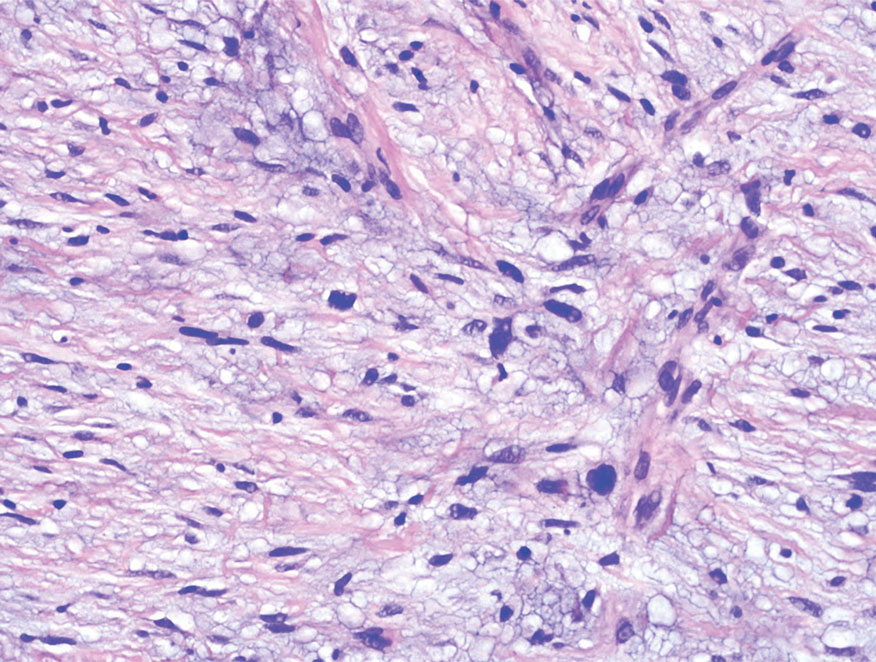

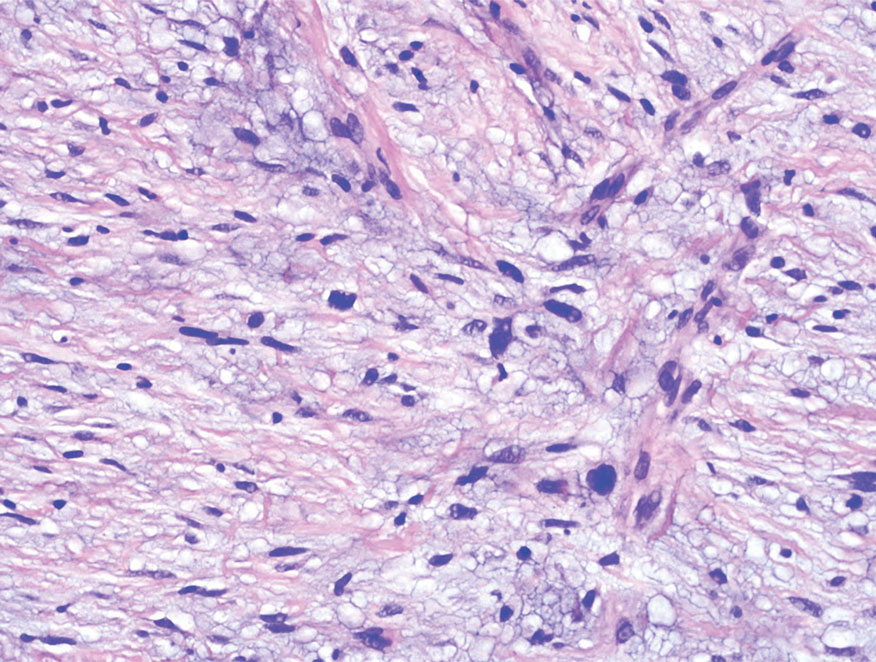

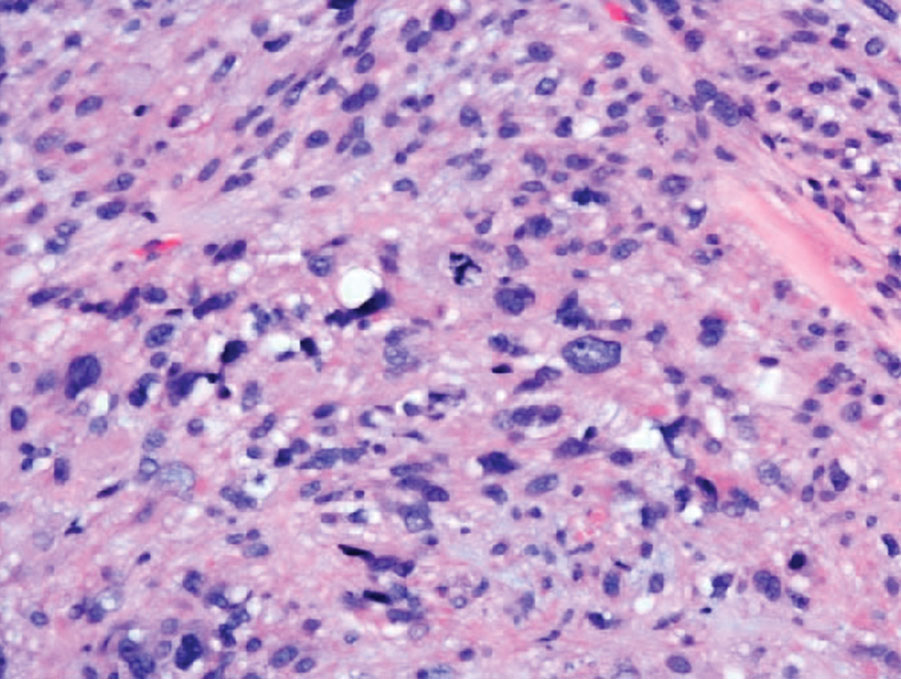

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

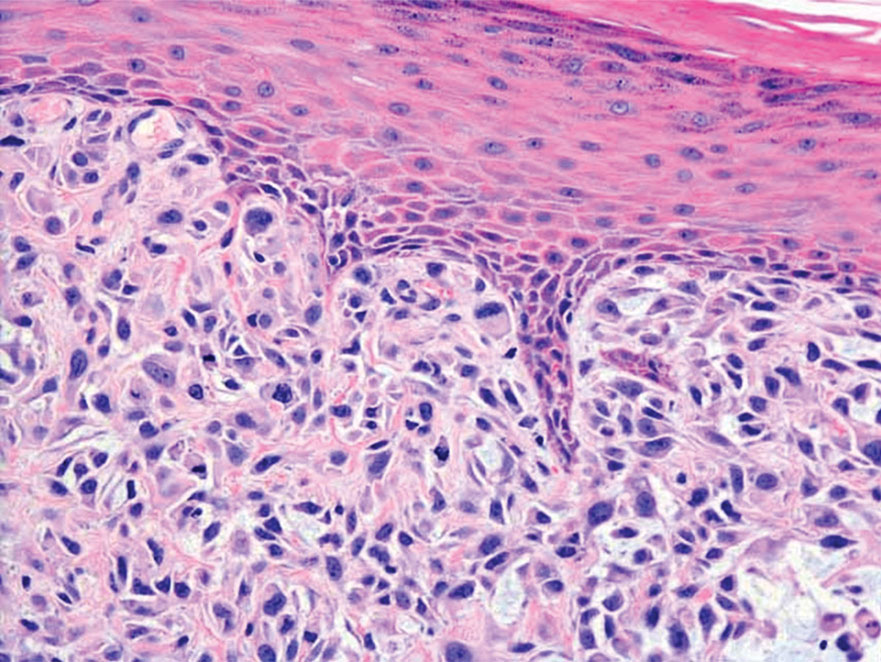

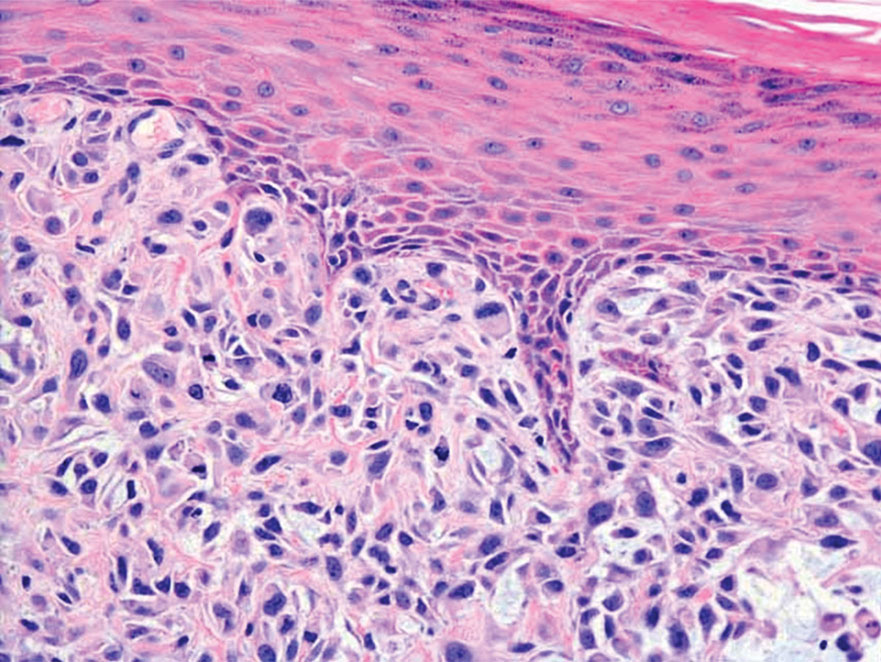

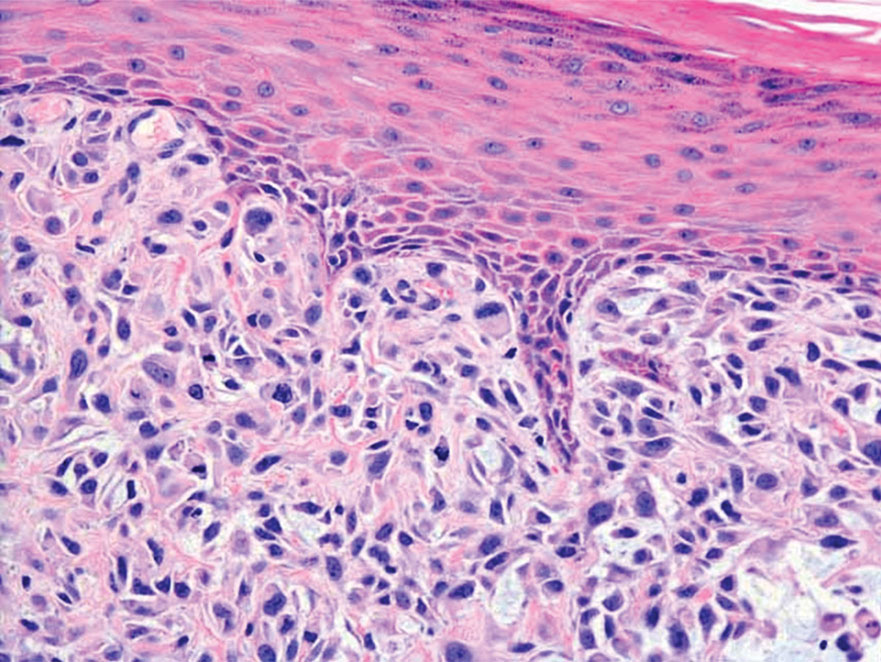

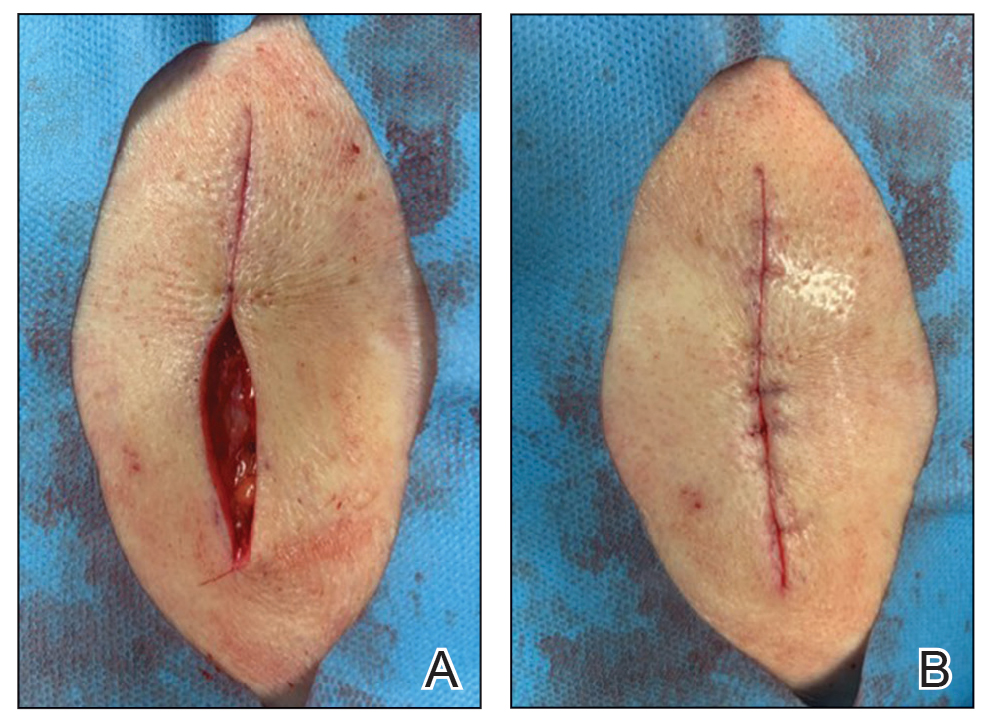

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

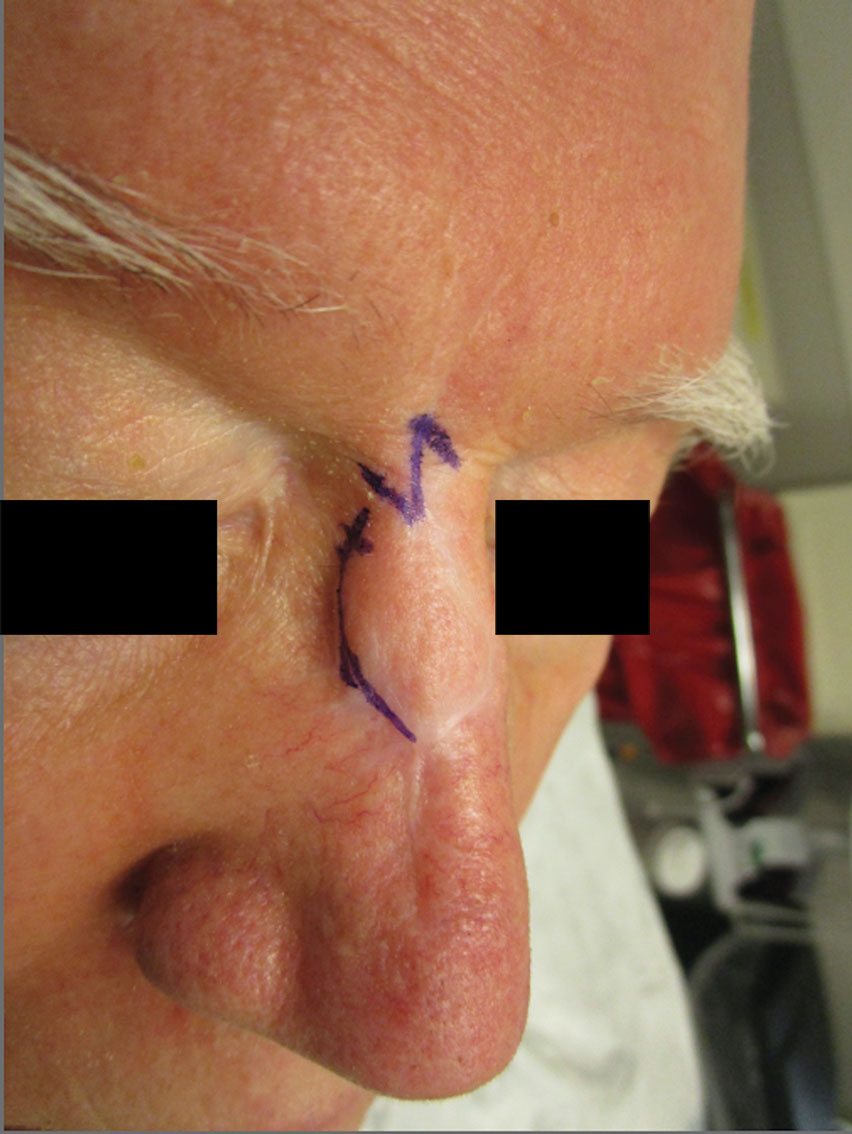

A 62-year-old man presented with a firm, exophytic, 2.8×1.5-cm tumor on the left shin of 6 to 7 years’ duration. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

FDA acts against sales of unapproved mole and skin tag products on Amazon, other sites

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

Discrepancies in Skin Cancer Screening Reporting Among Patients, Primary Care Physicians, and Patient Medical Records

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

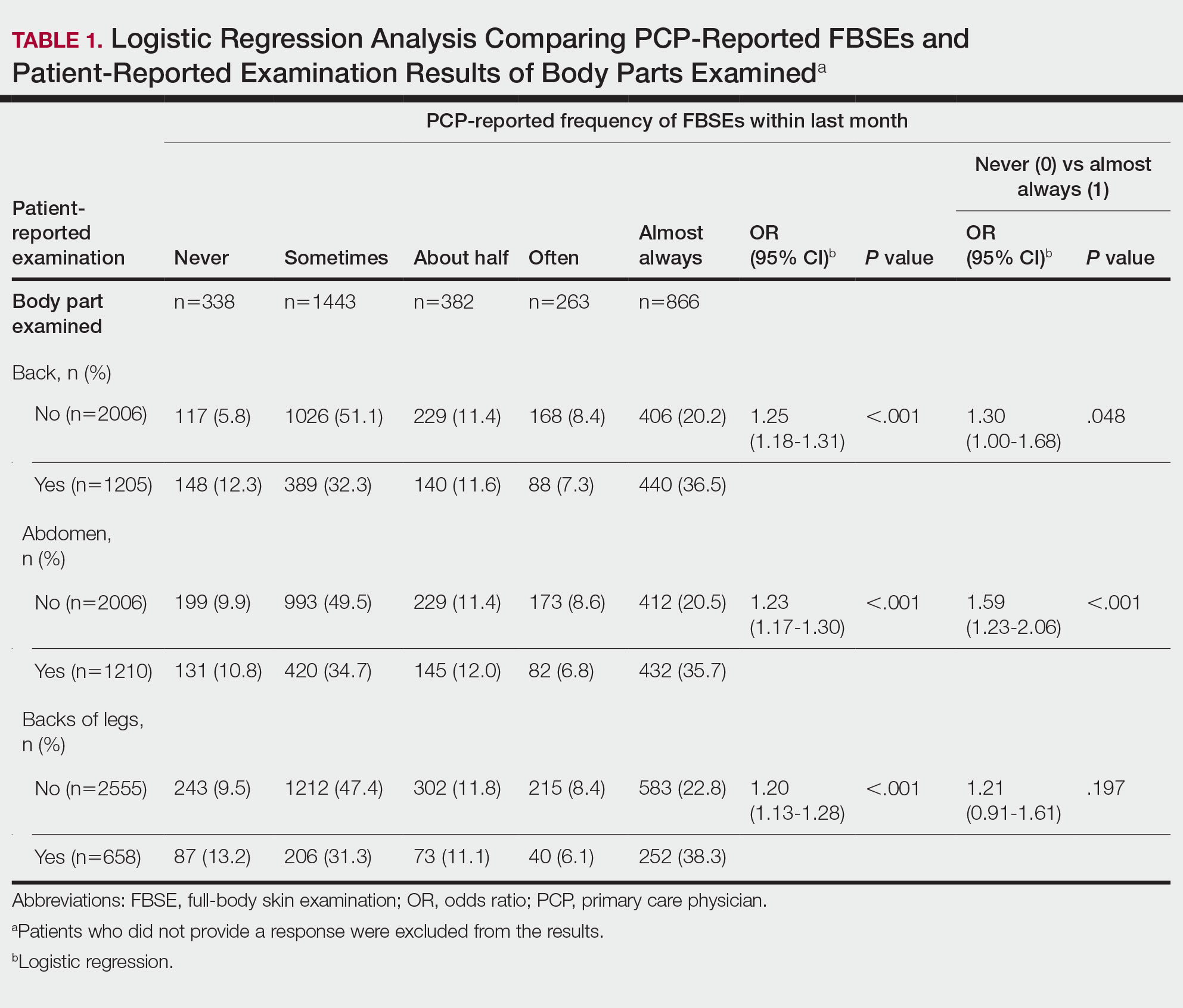

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics

The final sample included data from 53 physicians and 3343 patients. The study sample mean age (SD) was 50.3 (9.9) years for PCPs (n=53) and 59.8 (16.9) years for patients (n=3343). The physician sample was 36% female and predominantly White (83%). Ninety-one percent of the PCPs had an MD (the remaining had a DO degree), and the mean (SD) years practicing was 21.8 (10.6) years. Seventeen percent of PCPs were trained in internal medicine, 4% in internal medicine and pediatrics, and 79% family medicine; 79% of PCPs had received prior training in dermatology. The patient sample was 58% female, predominantly White (84%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (95%), had completed high school (94%), and earned more than $40,000 annually (66%).

Physician- and Patient-Reported FBSEs

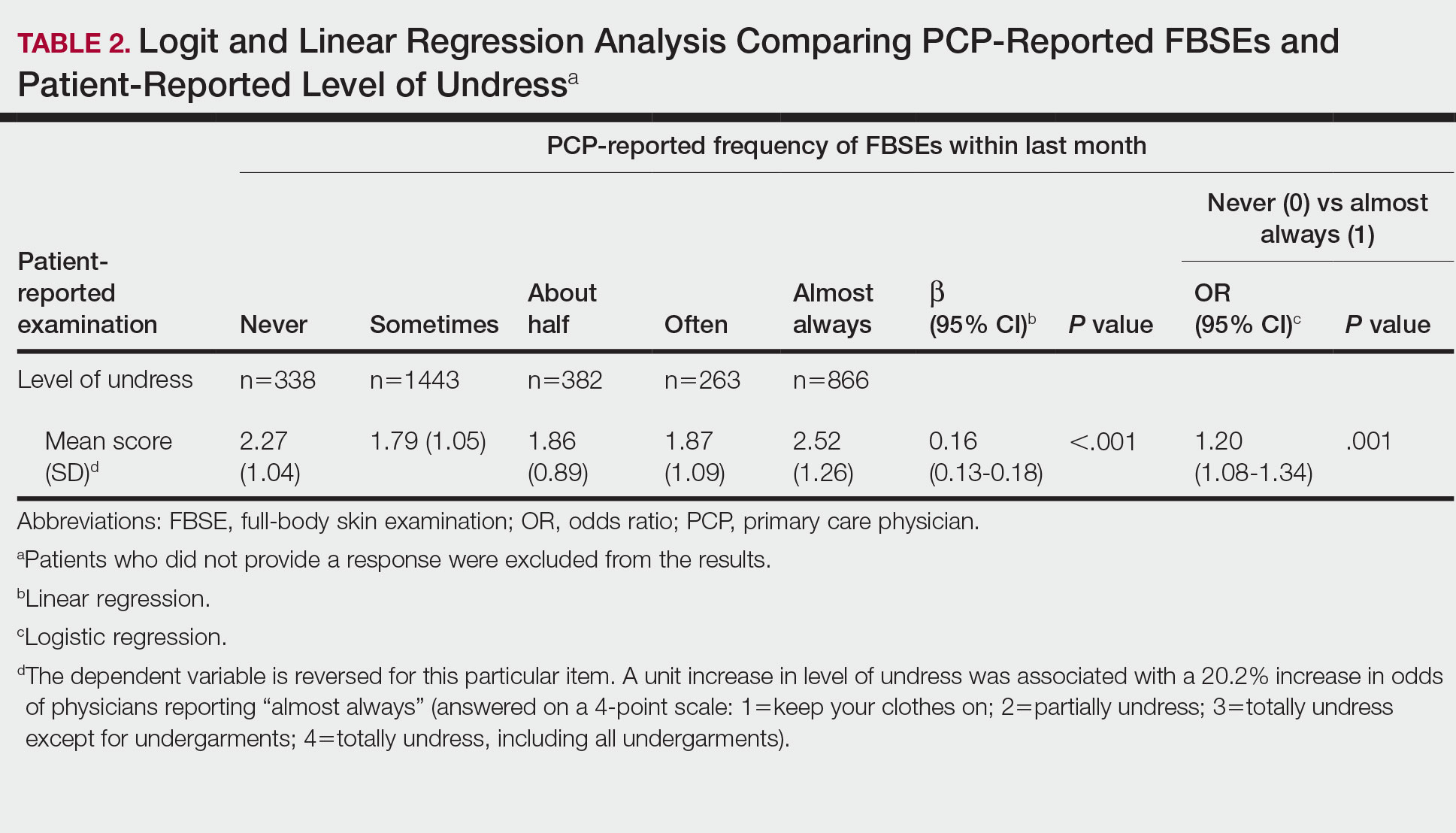

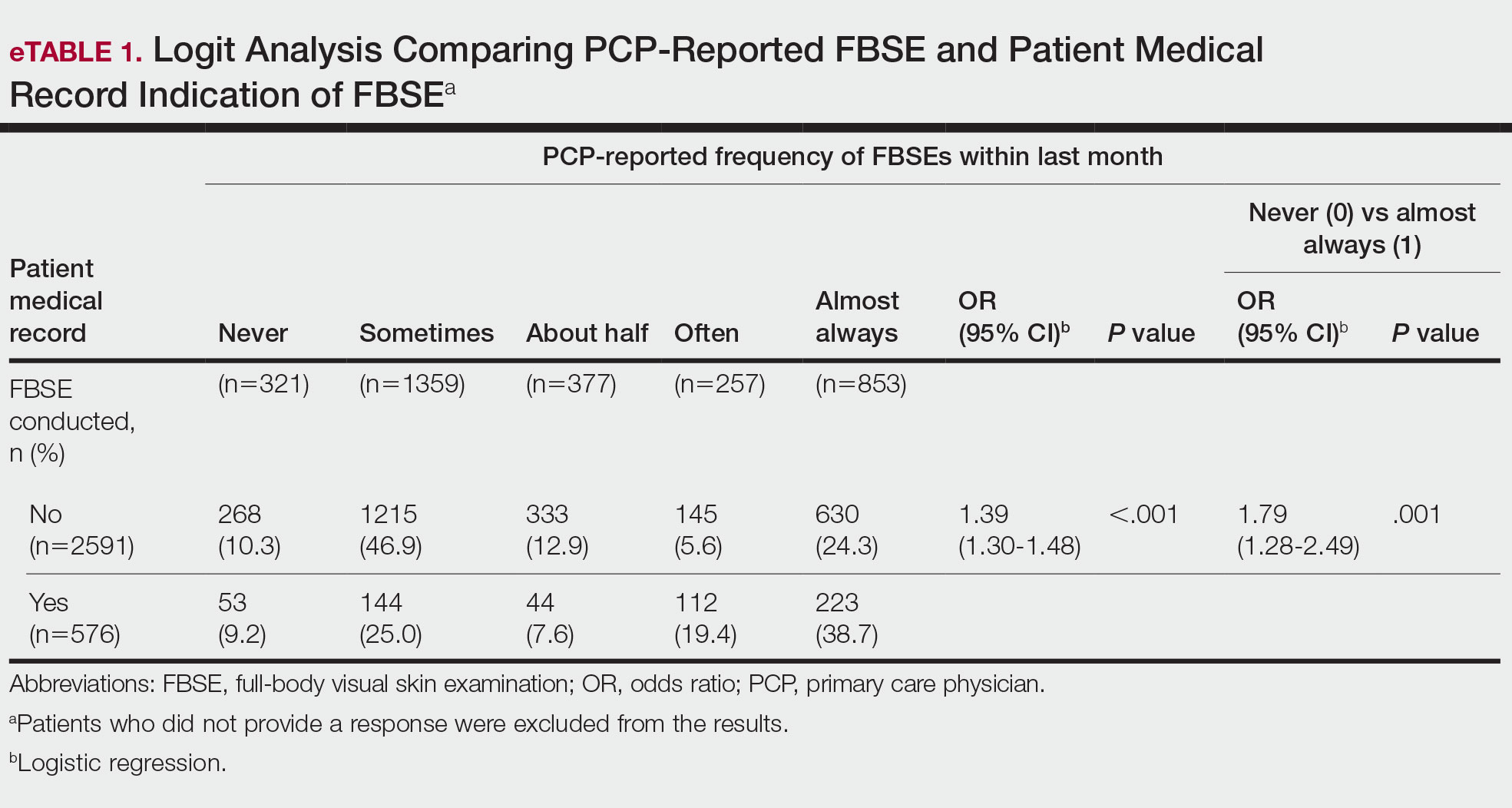

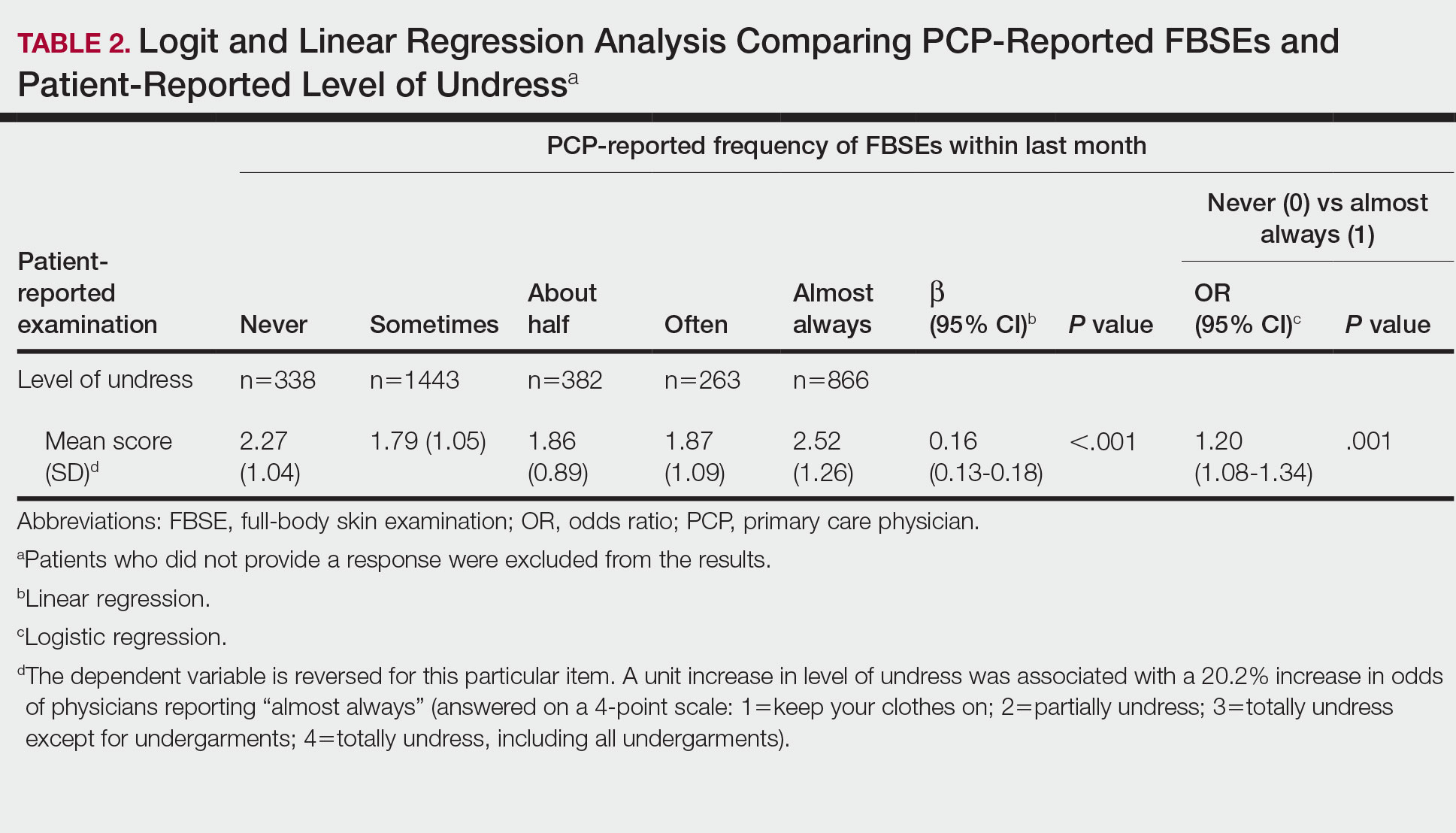

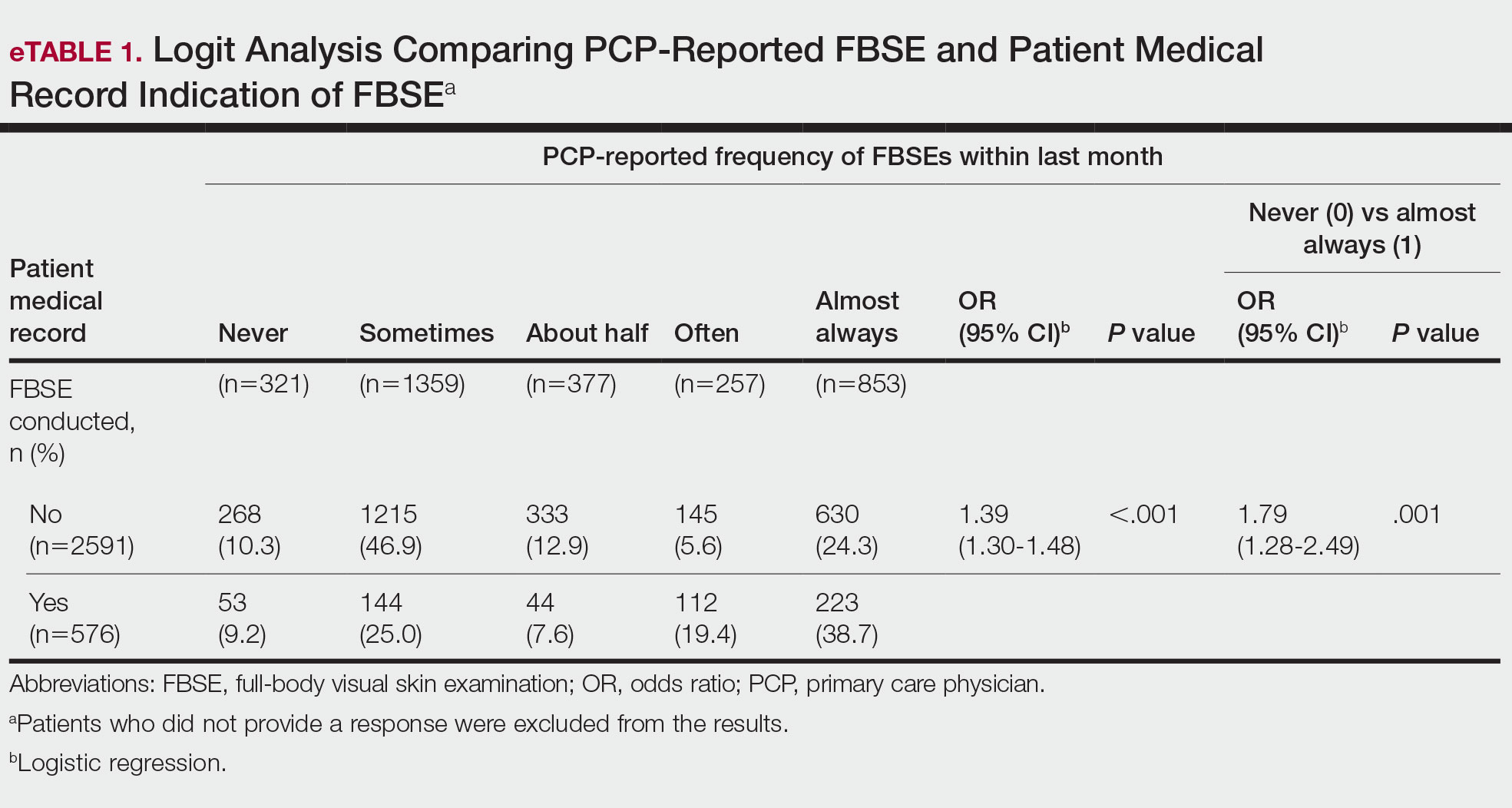

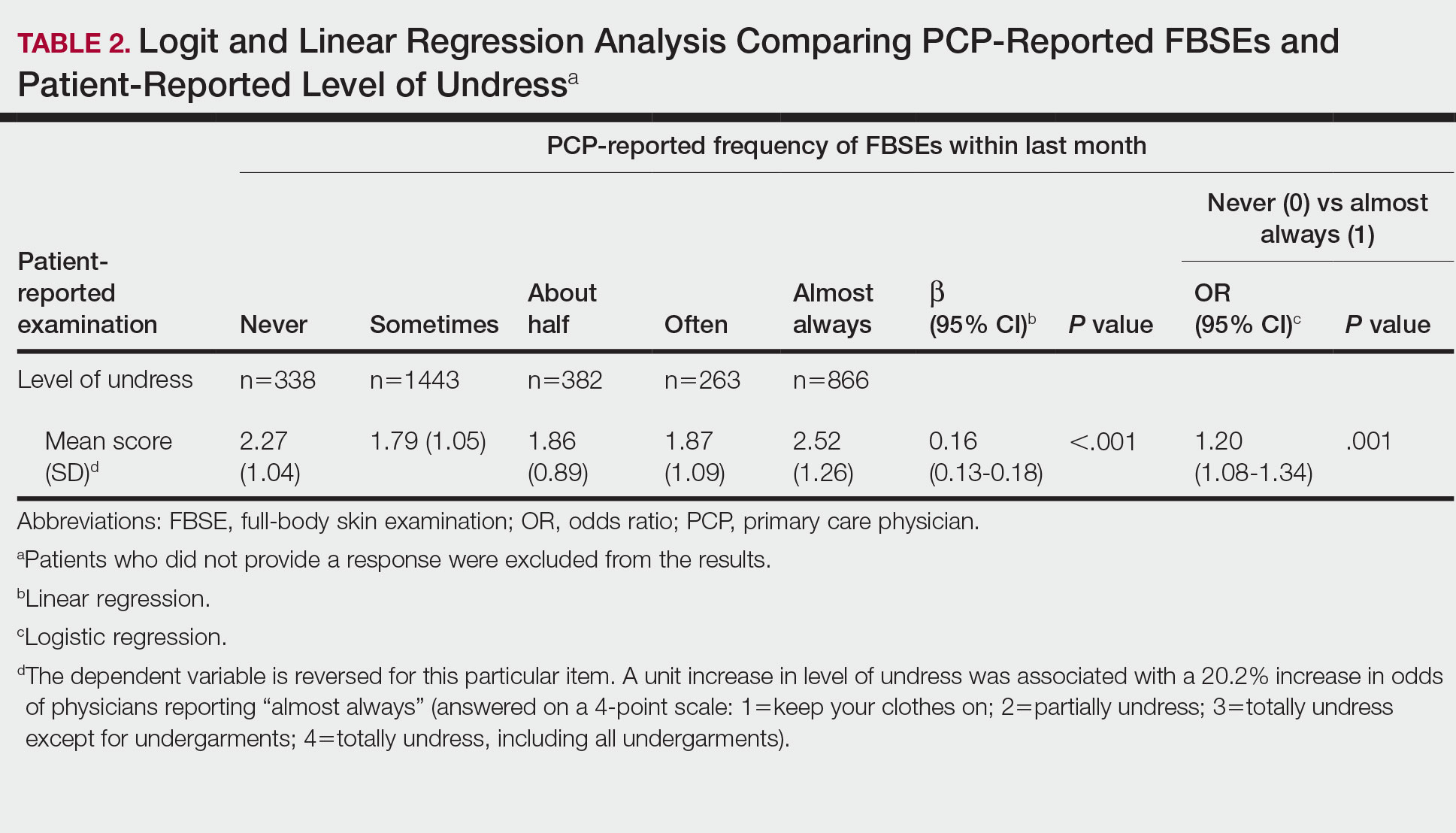

Physicians reported performing FBSEs with variable frequency. Among PCPs who conducted FBSEs with greater frequency, there was a modest increase in the odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: odds ratio [OR], 24.5% [95% CI, 1.18-1.31; P<.001]; abdomen: OR, 23.3% [95% CI, 1.17-1.30; P<.001]; backs of legs: OR, 20.4% [95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P<.001])(Table 1). The patient-reported level of undress during examination was significantly associated with physician-reported FBSE (β=0.16 [95% CI, 0.13-0.18; P<.001])(Table 2).

Because of the bimodal distribution of scores in the physician-reported frequency of FBSEs, particularly pertaining to the extreme points of the scale, we further repeated analysis with only the never and almost always groups (Table 1). Primary care providers who reported almost always for FBSE had 29.6% increased odds of patient-reported back examination (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P=.048) and 59.3% increased odds of patient-reported abdomen examination (95% CI, 1.23-2.06; P<.001). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE were 56%, 40%, and 26%, respectively. The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE were 52%, 51%, and 30%, respectively. Raw percentages were calculated by dividing the number of "yes" responses by participants for each body part examined by thetotal number of participant responses (“yes” and “no”) for each respective body part. There was no significant change in odds of patient-reported backs of legs examined with PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE. In addition, a greater patient-reported level of undress was associated with 20.2% increased odds of PCPs reporting almost always conducting an FBSE (95% CI, 1.08-1.34; P=.001).

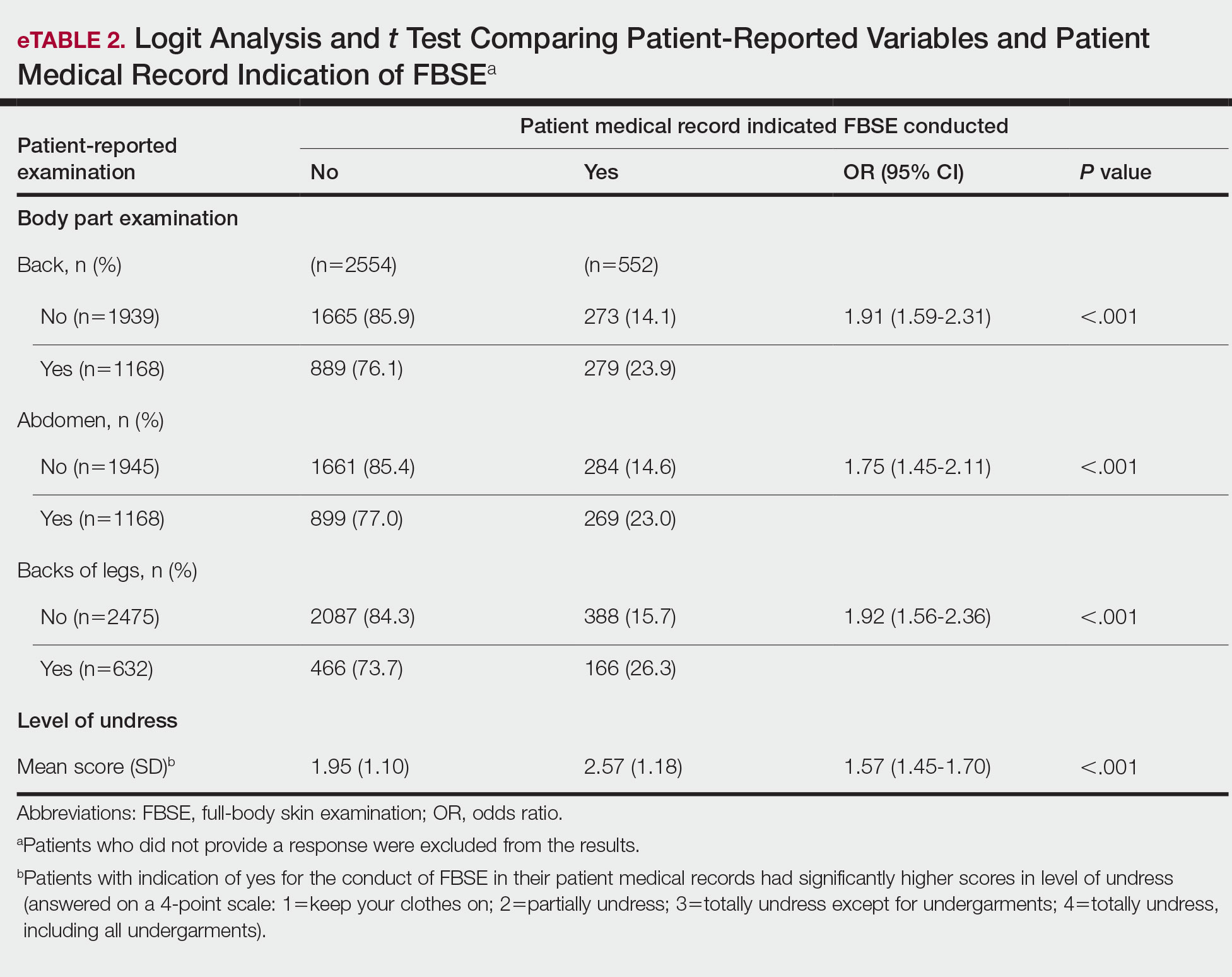

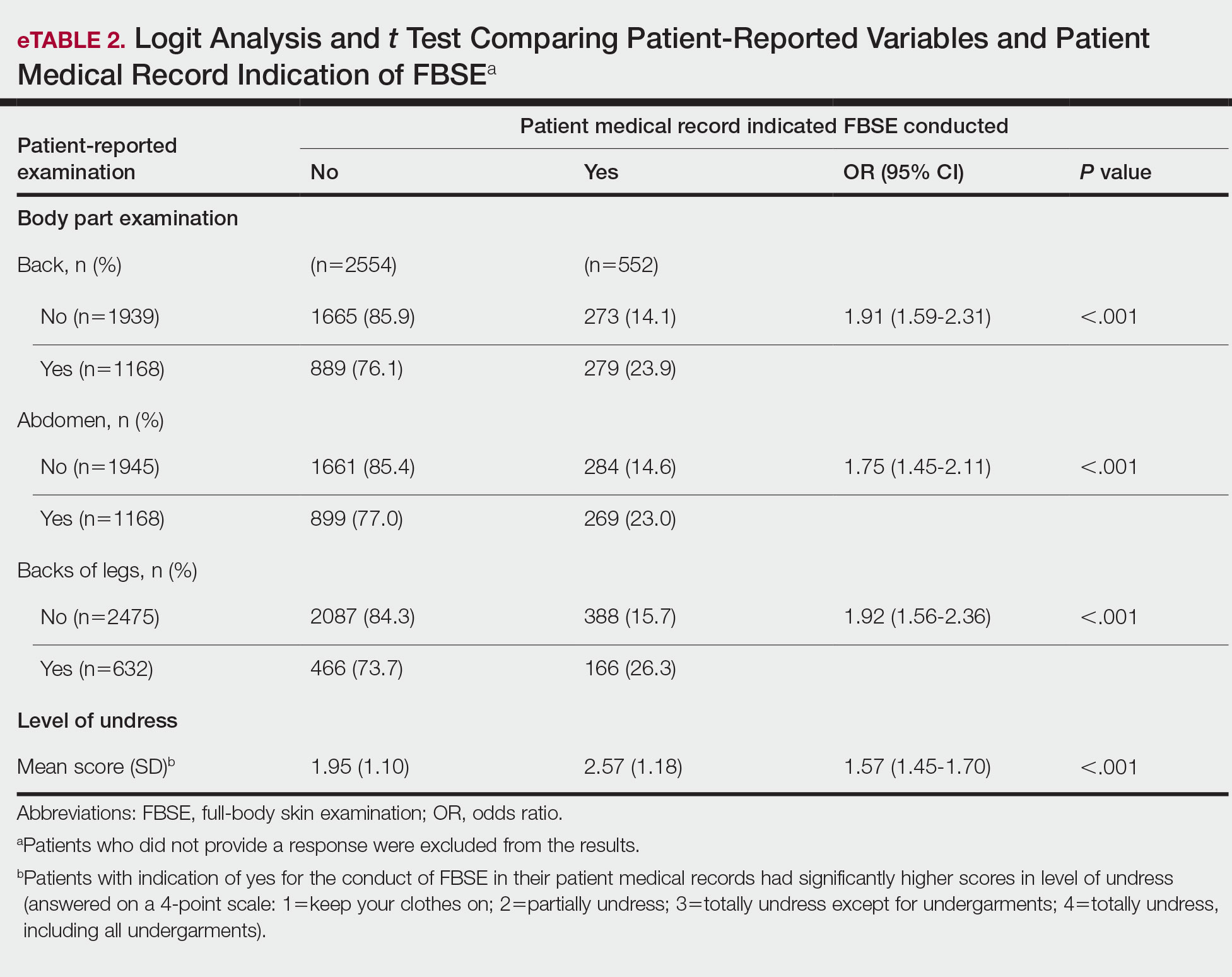

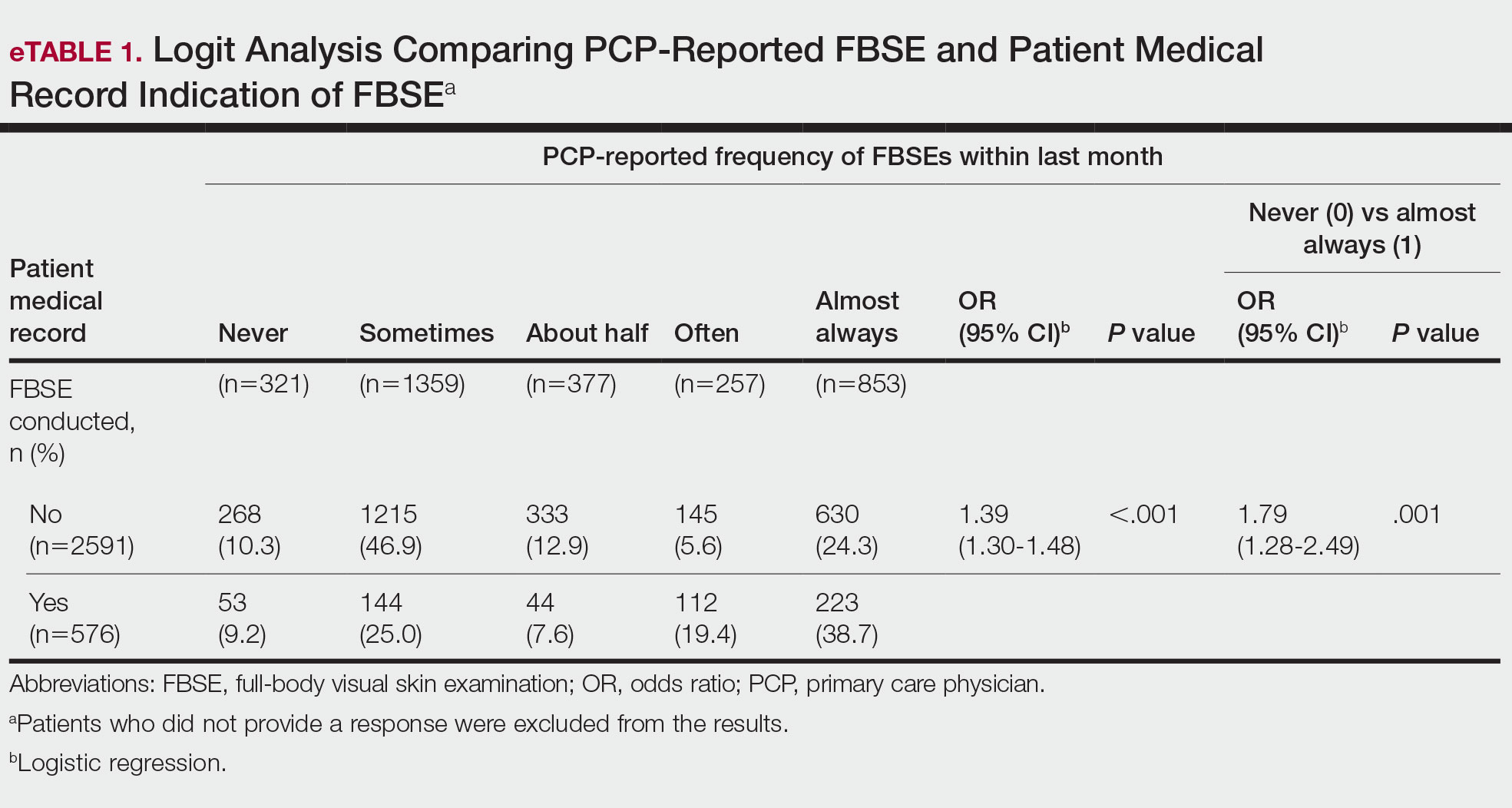

FBSEs in Patient Medical Records

When comparing PCP-reported FBSE and report of FBSE in patient medical records, there was a 39.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating FBSE when physicians reported conducting an FBSE with greater frequency (95% CI, 1.30-1.48; P<.001)(eTable 1). When examining PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE, a report of almost always was associated with 79.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating that an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.28-2.49; P=.001). The raw percentage of the patient medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE was 17% and 26% when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE.

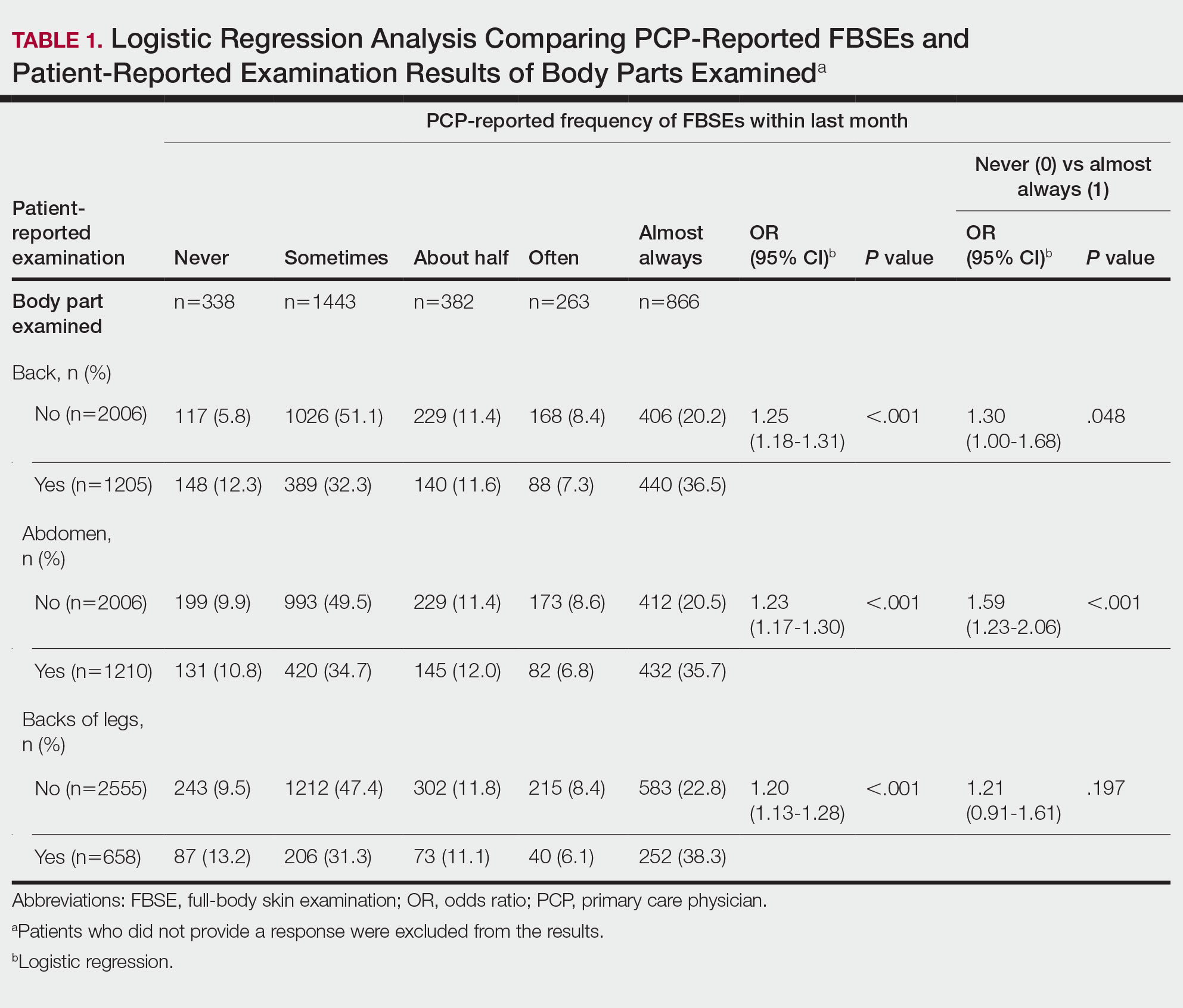

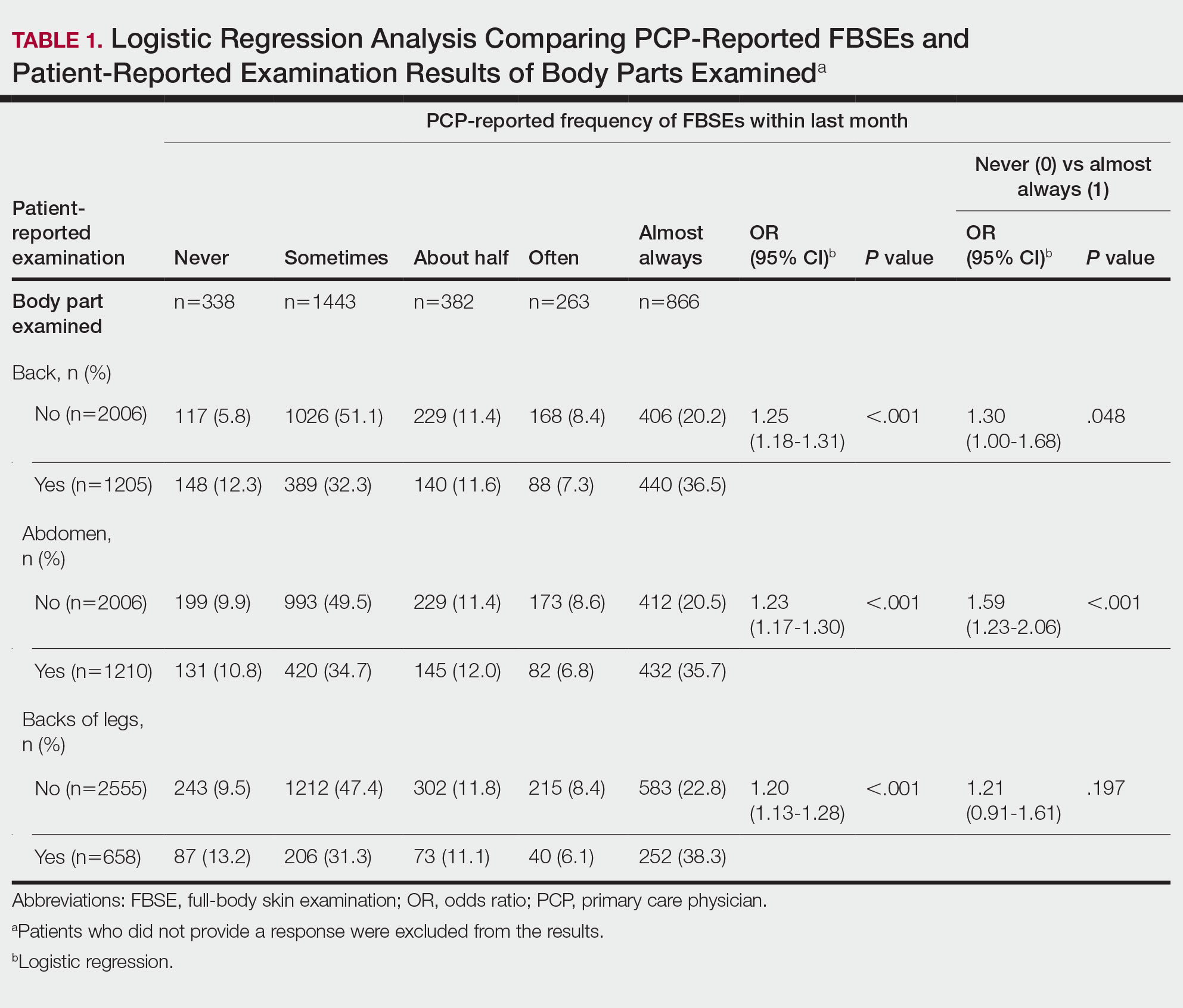

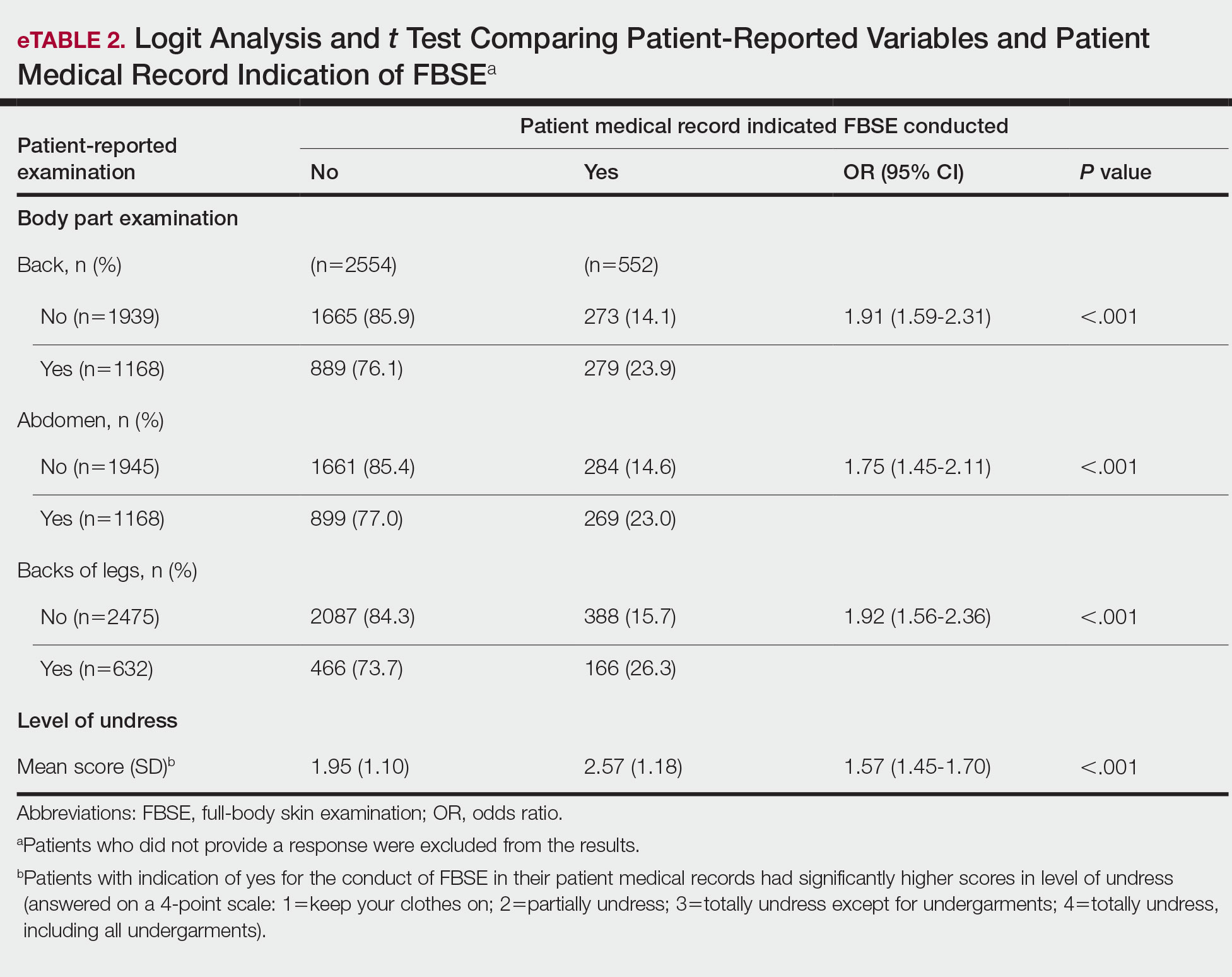

When comparing the patient-reported body part examined with patient FBSE medical record documentation, an indication of yes for FBSE on the patient medical record was associated with a considerable increase in odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: 91.4% [95% CI, 1.59-2.31; P<.001]; abdomen: 75.0% [95% CI, 1.45-2.11; P<.001]; backs of legs: 91.6% [95% CI, 1.56-2.36; P<.001])(eTable 2). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined vs not examined when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE was completed were 24% vs 14%, 23% vs 15%, and 26% vs 16%, respectively. An increase in patient-reported level of undress was associated with a 57.0% increased odds of their medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.45-1.70; P<.001).

COMMENT How PCPs Perform FBSEs Varies

We found that PCPs performed FBSEs with variable frequency, and among those who did, the patient report of their examination varied considerably (Table 1). There appears to be considerable ambiguity in each of these means of determining the extent to which the skin was inspected for skin cancer, which may render the task of improving such inspection more difficult. We asked patients whether their back, abdomen, and backs of legs were examined as an assessment of some of the variety of areas inspected during an FBSE. During a general well-visit appointment, a patient’s back and abdomen may be examined for multiple reasons. Patients may have misinterpreted elements of the pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal, or musculoskeletal examinations as being part of the FBSE. The back and abdomen—the least specific features of the FBSE—were reported by patients to be the most often examined. Conversely, the backs of the legs—the most specific feature of the FBSE—had the lowest odds of being examined (Table 1).

In addition to the potential limitations of patient awareness of physician activity, our results also could be explained by differences among PCPs in how they performed FBSEs. There is no standardized method of conducting an FBSE. Furthermore, not all medical students and residents are exposed to dermatology training. In our sample of 53 physicians, 79% had reported receiving dermatology training; however, we did not assess the extent to which they had been trained in conducting an FBSE and/or identifying malignant lesions. In an American survey of 659 medical students, more than two-thirds of students had never been trained or never examined a patient for skin cancer.21 In another American survey of 342 internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology residents across 7 medical schools and 4 residency programs, more than three-quarters of residents had never been trained in skin cancer screening.22 Our findings reflect insufficient and inconsistent training in skin cancer screening and underscore the need for mandatory education to ensure quality FBSEs are performed in the primary care setting.

Frequency of PCPs Performing FBSEs

Similar to prior studies analyzing the frequency of FBSE performance in the primary care setting,16,19,23,24 more than half of our PCP sample reported sometimes to never conducting FBSEs. The percentage of physicians who reported conducting FBSEs in our sample was greater than the proportion reported by the National Health Interview Survey, in which only 8% of patients received an FBSE in the prior year by a PCP or obstetrician/gynecologist,16 but similar to a smaller patient study.19 In that study, 87% of patients, regardless of their skin cancer history, also reported that they would like their PCP to perform an FBSE regularly.19 Although some of our patient participants may have declined an FBSE, it is unlikely that that would have entirely accounted for the relatively low number of PCPs who reported frequently performing FBSEs.

Documentation in Medical Records of FBSEs

Compared to PCP self-reported performance of FBSEs, considerably fewer PCPs marked the patient medical record as having completed an FBSE. Among patients with medical records that indicated an FBSE had been conducted, they reported higher odds of all 3 body parts being examined, the highest being the backs of the legs. Also, when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE had been completed, the odds that the PCP reported an FBSE also were higher. The relatively low medical record documentation of FBSEs highlights the need for more rigorous enforcement of accurate documentation. However, among the cases that were recorded, it appeared that the content of the examinations was more consistent.

Benefits of PCP-Led FBSEs

Although the USPSTF issued an I rating for PCP-led FBSEs,14 multiple national medical societies, including the American Cancer Society,25 American Academy of Dermatology,26 and Skin Cancer Foundation,27 as well as international guidelines in Germany,28 Australia,29,30 and New Zealand,31 recommend regular FBSEs among the general or at-risk population; New Zealand and Australia have the highest incidence and prevalence of melanoma in the world.8 The benefits of physician-led FBSEs on detection of early-stage skin cancer, and in particular, melanoma detection, have been documented in numerous studies.30,32-38 However, the variability and often poor quality of skin screening may contribute in part to the just as numerous null results from prior skin screening studies,15 perpetuating the insufficient status of skin examinations by USPSTF standards.14 Our study underscores both the variability in frequency and content of PCP-administered FBSEs. It also highlights the need for standardization of screening examinations at the medical student, trainee, and physician level.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, there was an unknown time lag between the FBSEs and physician self-reported surveys. Similarly, there was a variable time lag between the patient examination encounter and subsequent telephone survey. Both the physician and patient survey data may have been affected by recall bias. Second, patients were not asked directly whether an FBSE had been conducted. Furthermore, patients may not have appreciated whether the body part examined was part of the FBSE or another examination. Also, screenings often were not recorded in the medical record, assuming that the patient report and/or physician report was more accurate than the medical record.

Our study also was limited by demographics; our patient sample was largely comprised of White, educated, US adults, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Conversely, a notable strength of our study was that our participants were recruited from 4 geographically diverse centers. Furthermore, we had a comparatively large sample size of patients and physicians. Also, the independent assessment of provider-reported examinations, objective assessment of medical records, and patient reports of their encounters provides a strong foundation for assessing the independent contributions of each data source.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the challenges future studies face in promoting skin cancer screening in the primary care setting. Our findings underscore the need for a standardized FBSE as well as clear clinical expectations regarding skin cancer screening that is expected of PCPs.

As long as skin cancer screening rates remain low in the United States, patients will be subject to potential delays and missed diagnoses, impacting morbidity and mortality.8 There are burgeoning resources and efforts in place to increase skin cancer screening. For example, free validated online training is available for early detection of melanoma and other skin cancers (https://www.visualdx.com/skin-cancer-education/).39-42 Future directions for bolstering screening numbers must focus on educating PCPs about skin cancer prevention and perhaps narrowing the screening population by age-appropriate risk assessments.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Dourmishev LA, Rusinova D, Botev I. Clinical variants, stages, and management of basal cell carcinoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:12-17.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:243-251.

- Weinstock MA, Bogaars HA, Ashley M, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality. a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1194-1197.

- Matthews NH, Li W-Q, Qureshi AA, et al. Epidemiology of melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, eds. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy. Codon Publications; 2017:3-22.

- Cakir BO, Adamson P, Cingi C. Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20:419-422.

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187.

- Losina E, Walensky RP, Geller A, et al. Visual screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:21-28.

- Markova A, Weinstock MA, Risica P, et al. Effect of a web-based curriculum on primary care practice: basic skin cancer triage trial. Fam Med. 2013;45:558-568.

- Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Screening for skin cancer in adults: an updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. November 30, 2015. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review159/skin-cancer-screening2

- Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for skin cancer in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review forthe US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:436-447.

- LeBlanc WG, Vidal L, Kirsner RS, et al. Reported skin cancer screening of US adult workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:55-63.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Caralis PV, et al. Screening for skin cancer in primary care settings. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1423-1425.

- Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG. Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:564-566.

- Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Tobin DG, et al. Full-body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:530-534.

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp; 2015.

- Moore MM, Geller AC, Zhang Z, et al. Skin cancer examination teaching in US medical education. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:439-444.

- Wise E, Singh D, Moore M, et al. Rates of skin cancer screening and prevention counseling by US medical residents. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1131-1136.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am J Med. 2010;123:439-445.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer incidence rates. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer prevention. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/prevention-guidelines

- Katalinic A, Eisemann N, Waldmann A. Skin cancer screening in Germany. documenting melanoma incidence and mortality from 2008 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:629-634.

- Cancer Council Australia. Position statement: screening and early detection of skin cancer. Published July 2014. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://dermcoll.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PosStatEarlyDetectSkinCa.pdf

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice. 9th ed. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2016. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Redbook9/17048-Red-Book-9th-Edition.pdf

- Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network and New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney and New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington; 2008. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/melanoma-guideline-nov08-v2.pdf

- Swetter SM, Pollitt RA, Johnson TM, et al. Behavioral determinants of successful early melanoma detection: role of self and physician skin examination. Cancer. 2012;118:3725-3734.

- Terushkin V, Halpern AC. Melanoma early detection. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:481-500, viii.

- Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:450-458.

- Aitken JF, Elwood JM, Lowe JB, et al. A randomised trial of population screening for melanoma. J Med Screen. 2002;9:33-37.

- Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:201-211.

- Janda M, Lowe JB, Elwood M, et al. Do centralised skin screening clinics increase participation in melanoma screening (Australia)? Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:161-168.

- Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:105-114.

- Eide MJ, Asgari MM, Fletcher SW, et al. Effects on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:648-657.

- Weinstock MA, Ferris LK, Saul MI, et al. Downstream consequences of melanoma screening in a community practice setting: first results. Cancer. 2016;122:3152-3156.

- Matthews NH, Risica PM, Ferris LK, et al. Psychosocial impact of skin biopsies in the setting of melanoma screening: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:664-665.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics

The final sample included data from 53 physicians and 3343 patients. The study sample mean age (SD) was 50.3 (9.9) years for PCPs (n=53) and 59.8 (16.9) years for patients (n=3343). The physician sample was 36% female and predominantly White (83%). Ninety-one percent of the PCPs had an MD (the remaining had a DO degree), and the mean (SD) years practicing was 21.8 (10.6) years. Seventeen percent of PCPs were trained in internal medicine, 4% in internal medicine and pediatrics, and 79% family medicine; 79% of PCPs had received prior training in dermatology. The patient sample was 58% female, predominantly White (84%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (95%), had completed high school (94%), and earned more than $40,000 annually (66%).

Physician- and Patient-Reported FBSEs

Physicians reported performing FBSEs with variable frequency. Among PCPs who conducted FBSEs with greater frequency, there was a modest increase in the odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: odds ratio [OR], 24.5% [95% CI, 1.18-1.31; P<.001]; abdomen: OR, 23.3% [95% CI, 1.17-1.30; P<.001]; backs of legs: OR, 20.4% [95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P<.001])(Table 1). The patient-reported level of undress during examination was significantly associated with physician-reported FBSE (β=0.16 [95% CI, 0.13-0.18; P<.001])(Table 2).

Because of the bimodal distribution of scores in the physician-reported frequency of FBSEs, particularly pertaining to the extreme points of the scale, we further repeated analysis with only the never and almost always groups (Table 1). Primary care providers who reported almost always for FBSE had 29.6% increased odds of patient-reported back examination (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P=.048) and 59.3% increased odds of patient-reported abdomen examination (95% CI, 1.23-2.06; P<.001). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE were 56%, 40%, and 26%, respectively. The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE were 52%, 51%, and 30%, respectively. Raw percentages were calculated by dividing the number of "yes" responses by participants for each body part examined by thetotal number of participant responses (“yes” and “no”) for each respective body part. There was no significant change in odds of patient-reported backs of legs examined with PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE. In addition, a greater patient-reported level of undress was associated with 20.2% increased odds of PCPs reporting almost always conducting an FBSE (95% CI, 1.08-1.34; P=.001).

FBSEs in Patient Medical Records

When comparing PCP-reported FBSE and report of FBSE in patient medical records, there was a 39.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating FBSE when physicians reported conducting an FBSE with greater frequency (95% CI, 1.30-1.48; P<.001)(eTable 1). When examining PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE, a report of almost always was associated with 79.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating that an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.28-2.49; P=.001). The raw percentage of the patient medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE was 17% and 26% when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE.

When comparing the patient-reported body part examined with patient FBSE medical record documentation, an indication of yes for FBSE on the patient medical record was associated with a considerable increase in odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: 91.4% [95% CI, 1.59-2.31; P<.001]; abdomen: 75.0% [95% CI, 1.45-2.11; P<.001]; backs of legs: 91.6% [95% CI, 1.56-2.36; P<.001])(eTable 2). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined vs not examined when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE was completed were 24% vs 14%, 23% vs 15%, and 26% vs 16%, respectively. An increase in patient-reported level of undress was associated with a 57.0% increased odds of their medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.45-1.70; P<.001).

COMMENT How PCPs Perform FBSEs Varies

We found that PCPs performed FBSEs with variable frequency, and among those who did, the patient report of their examination varied considerably (Table 1). There appears to be considerable ambiguity in each of these means of determining the extent to which the skin was inspected for skin cancer, which may render the task of improving such inspection more difficult. We asked patients whether their back, abdomen, and backs of legs were examined as an assessment of some of the variety of areas inspected during an FBSE. During a general well-visit appointment, a patient’s back and abdomen may be examined for multiple reasons. Patients may have misinterpreted elements of the pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal, or musculoskeletal examinations as being part of the FBSE. The back and abdomen—the least specific features of the FBSE—were reported by patients to be the most often examined. Conversely, the backs of the legs—the most specific feature of the FBSE—had the lowest odds of being examined (Table 1).

In addition to the potential limitations of patient awareness of physician activity, our results also could be explained by differences among PCPs in how they performed FBSEs. There is no standardized method of conducting an FBSE. Furthermore, not all medical students and residents are exposed to dermatology training. In our sample of 53 physicians, 79% had reported receiving dermatology training; however, we did not assess the extent to which they had been trained in conducting an FBSE and/or identifying malignant lesions. In an American survey of 659 medical students, more than two-thirds of students had never been trained or never examined a patient for skin cancer.21 In another American survey of 342 internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology residents across 7 medical schools and 4 residency programs, more than three-quarters of residents had never been trained in skin cancer screening.22 Our findings reflect insufficient and inconsistent training in skin cancer screening and underscore the need for mandatory education to ensure quality FBSEs are performed in the primary care setting.

Frequency of PCPs Performing FBSEs

Similar to prior studies analyzing the frequency of FBSE performance in the primary care setting,16,19,23,24 more than half of our PCP sample reported sometimes to never conducting FBSEs. The percentage of physicians who reported conducting FBSEs in our sample was greater than the proportion reported by the National Health Interview Survey, in which only 8% of patients received an FBSE in the prior year by a PCP or obstetrician/gynecologist,16 but similar to a smaller patient study.19 In that study, 87% of patients, regardless of their skin cancer history, also reported that they would like their PCP to perform an FBSE regularly.19 Although some of our patient participants may have declined an FBSE, it is unlikely that that would have entirely accounted for the relatively low number of PCPs who reported frequently performing FBSEs.

Documentation in Medical Records of FBSEs

Compared to PCP self-reported performance of FBSEs, considerably fewer PCPs marked the patient medical record as having completed an FBSE. Among patients with medical records that indicated an FBSE had been conducted, they reported higher odds of all 3 body parts being examined, the highest being the backs of the legs. Also, when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE had been completed, the odds that the PCP reported an FBSE also were higher. The relatively low medical record documentation of FBSEs highlights the need for more rigorous enforcement of accurate documentation. However, among the cases that were recorded, it appeared that the content of the examinations was more consistent.

Benefits of PCP-Led FBSEs

Although the USPSTF issued an I rating for PCP-led FBSEs,14 multiple national medical societies, including the American Cancer Society,25 American Academy of Dermatology,26 and Skin Cancer Foundation,27 as well as international guidelines in Germany,28 Australia,29,30 and New Zealand,31 recommend regular FBSEs among the general or at-risk population; New Zealand and Australia have the highest incidence and prevalence of melanoma in the world.8 The benefits of physician-led FBSEs on detection of early-stage skin cancer, and in particular, melanoma detection, have been documented in numerous studies.30,32-38 However, the variability and often poor quality of skin screening may contribute in part to the just as numerous null results from prior skin screening studies,15 perpetuating the insufficient status of skin examinations by USPSTF standards.14 Our study underscores both the variability in frequency and content of PCP-administered FBSEs. It also highlights the need for standardization of screening examinations at the medical student, trainee, and physician level.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, there was an unknown time lag between the FBSEs and physician self-reported surveys. Similarly, there was a variable time lag between the patient examination encounter and subsequent telephone survey. Both the physician and patient survey data may have been affected by recall bias. Second, patients were not asked directly whether an FBSE had been conducted. Furthermore, patients may not have appreciated whether the body part examined was part of the FBSE or another examination. Also, screenings often were not recorded in the medical record, assuming that the patient report and/or physician report was more accurate than the medical record.

Our study also was limited by demographics; our patient sample was largely comprised of White, educated, US adults, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Conversely, a notable strength of our study was that our participants were recruited from 4 geographically diverse centers. Furthermore, we had a comparatively large sample size of patients and physicians. Also, the independent assessment of provider-reported examinations, objective assessment of medical records, and patient reports of their encounters provides a strong foundation for assessing the independent contributions of each data source.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the challenges future studies face in promoting skin cancer screening in the primary care setting. Our findings underscore the need for a standardized FBSE as well as clear clinical expectations regarding skin cancer screening that is expected of PCPs.

As long as skin cancer screening rates remain low in the United States, patients will be subject to potential delays and missed diagnoses, impacting morbidity and mortality.8 There are burgeoning resources and efforts in place to increase skin cancer screening. For example, free validated online training is available for early detection of melanoma and other skin cancers (https://www.visualdx.com/skin-cancer-education/).39-42 Future directions for bolstering screening numbers must focus on educating PCPs about skin cancer prevention and perhaps narrowing the screening population by age-appropriate risk assessments.

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics