User login

In vasculitis, the skin tells the story

MILAN – , Robert Micheletti, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

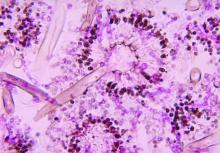

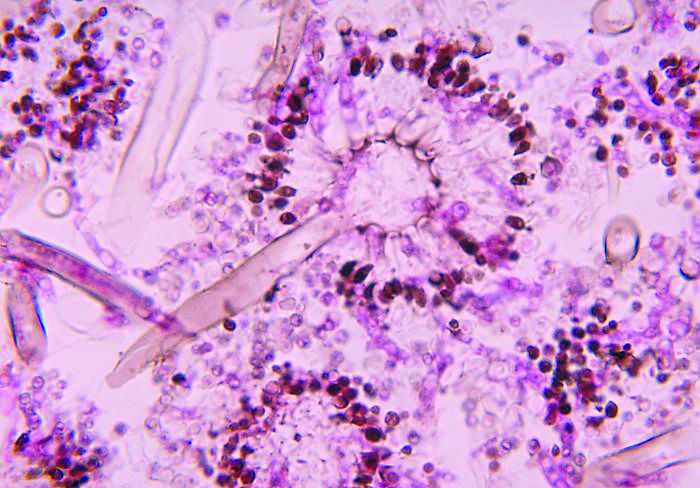

In granulomatous vasculitis, histiocytes and giant cells can play a significant role, explained Dr. Micheletti, director of the cutaneous vasculitis clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The condition may be secondary to an autoimmune disease such as lupus erythematosus or RA; a granulomatous disease such as Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis; infections such as tuberculosis, a fungal disease, or herpes or zoster viruses, or lymphoma, Dr. Micheletti said.

However, a primary systemic vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly known as Wegener’s polyangiitis) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; also known as Churg-Strauss vasculitis), giant cell arteritis, or Takayasu arteritis may also be responsible, he said. Occasionally, the culprit can also be a drug-induced vasculitis.

The physical examination gives clues to the size of involved vessels, which in turn helps to classify the vasculitis, Dr. Micheletti said.

When vasculitis affects small vessels, the skin findings will be palpable purpura, urticarial papules, vesicles, and petechiae, he said, adding that “The small vessel involvement accounts for the small size of the lesions, and complement cascade and inflammation account for the palpability of the lesions and the symptomatology.” As red blood cells extravasate from the affected vessels, nonblanching purpura develop, and gravity’s effect on the deposition of immune complex material dictates how lesions are distributed.

“Manifestations more typical of medium vessel vasculitis include subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, larger hemorrhagic bullae, and more significant ulceration and necrosis,” he said. “If such lesions are seen, suspect medium-vessel vasculitis or vasculitis overlapping small and medium vessels.” Cutaneous or systemic polyarteritis nodosa, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are examples, he added.

The particularities of renal manifestations of vasculitis also offer clues to the vessels involved. When a vasculitis patient has glomerulonephritis, suspect small-vessel involvement, Dr. Micheletti said. However, vasculitis affecting medium-sized vessels will cause renovascular hypertension and, potentially renal arterial aneurysms.

Nerves are typically spared in small-vessel vasculitis, while wrist or foot drop can be seen in mononeuritis multiplex.

Recently, the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) looked at more than 6,800 patients at over 130 sites around the world, proposing new classification criteria for ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) and large-vessel vasculitis. The study found that skin findings are common in AAV, with 30%-50% of cases presenting initially with skin lesions. Petechiae and/or purpura are the most common of the skin manifestations, he said. By contrast, for EGPA, allergic and nonspecific findings were the most common findings.

Although skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis in up to 94% of AAV cases, it’s underutilized and performed in less than half (24%-44%) of cases, Dr. Micheletti said. The study’s findings “demonstrate the importance of a good skin exam, as well as its utility for diagnosis” of vasculitis, he said.

An additional finding form the DCVAS study was that skin lesions can give clues to severity of vasculitis: “Among 1,184 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis, those with cutaneous involvement were more likely to have systemic manifestations of disease, more likely to have such severe manifestations as glomerulonephritis, alveolar hemorrhage, and mononeuritis,” said Dr. Micheletti, with a hazard ratio of 2.0 among those individuals who had EGPA or GPA.

“Skin findings have diagnostic and, potentially, prognostic importance,” he said. “Use the physician exam and your clinical acumen to your advantage,” but always confirm vasculitis with a biopsy. “Clinicopathologic correlation is key.” A simple urinalysis will screen for renal involvement, and is of “paramount importance,” he added.

Dr. Micheletti reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

MILAN – , Robert Micheletti, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

In granulomatous vasculitis, histiocytes and giant cells can play a significant role, explained Dr. Micheletti, director of the cutaneous vasculitis clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The condition may be secondary to an autoimmune disease such as lupus erythematosus or RA; a granulomatous disease such as Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis; infections such as tuberculosis, a fungal disease, or herpes or zoster viruses, or lymphoma, Dr. Micheletti said.

However, a primary systemic vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly known as Wegener’s polyangiitis) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; also known as Churg-Strauss vasculitis), giant cell arteritis, or Takayasu arteritis may also be responsible, he said. Occasionally, the culprit can also be a drug-induced vasculitis.

The physical examination gives clues to the size of involved vessels, which in turn helps to classify the vasculitis, Dr. Micheletti said.

When vasculitis affects small vessels, the skin findings will be palpable purpura, urticarial papules, vesicles, and petechiae, he said, adding that “The small vessel involvement accounts for the small size of the lesions, and complement cascade and inflammation account for the palpability of the lesions and the symptomatology.” As red blood cells extravasate from the affected vessels, nonblanching purpura develop, and gravity’s effect on the deposition of immune complex material dictates how lesions are distributed.

“Manifestations more typical of medium vessel vasculitis include subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, larger hemorrhagic bullae, and more significant ulceration and necrosis,” he said. “If such lesions are seen, suspect medium-vessel vasculitis or vasculitis overlapping small and medium vessels.” Cutaneous or systemic polyarteritis nodosa, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are examples, he added.

The particularities of renal manifestations of vasculitis also offer clues to the vessels involved. When a vasculitis patient has glomerulonephritis, suspect small-vessel involvement, Dr. Micheletti said. However, vasculitis affecting medium-sized vessels will cause renovascular hypertension and, potentially renal arterial aneurysms.

Nerves are typically spared in small-vessel vasculitis, while wrist or foot drop can be seen in mononeuritis multiplex.

Recently, the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) looked at more than 6,800 patients at over 130 sites around the world, proposing new classification criteria for ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) and large-vessel vasculitis. The study found that skin findings are common in AAV, with 30%-50% of cases presenting initially with skin lesions. Petechiae and/or purpura are the most common of the skin manifestations, he said. By contrast, for EGPA, allergic and nonspecific findings were the most common findings.

Although skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis in up to 94% of AAV cases, it’s underutilized and performed in less than half (24%-44%) of cases, Dr. Micheletti said. The study’s findings “demonstrate the importance of a good skin exam, as well as its utility for diagnosis” of vasculitis, he said.

An additional finding form the DCVAS study was that skin lesions can give clues to severity of vasculitis: “Among 1,184 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis, those with cutaneous involvement were more likely to have systemic manifestations of disease, more likely to have such severe manifestations as glomerulonephritis, alveolar hemorrhage, and mononeuritis,” said Dr. Micheletti, with a hazard ratio of 2.0 among those individuals who had EGPA or GPA.

“Skin findings have diagnostic and, potentially, prognostic importance,” he said. “Use the physician exam and your clinical acumen to your advantage,” but always confirm vasculitis with a biopsy. “Clinicopathologic correlation is key.” A simple urinalysis will screen for renal involvement, and is of “paramount importance,” he added.

Dr. Micheletti reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

MILAN – , Robert Micheletti, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

In granulomatous vasculitis, histiocytes and giant cells can play a significant role, explained Dr. Micheletti, director of the cutaneous vasculitis clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The condition may be secondary to an autoimmune disease such as lupus erythematosus or RA; a granulomatous disease such as Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis; infections such as tuberculosis, a fungal disease, or herpes or zoster viruses, or lymphoma, Dr. Micheletti said.

However, a primary systemic vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly known as Wegener’s polyangiitis) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; also known as Churg-Strauss vasculitis), giant cell arteritis, or Takayasu arteritis may also be responsible, he said. Occasionally, the culprit can also be a drug-induced vasculitis.

The physical examination gives clues to the size of involved vessels, which in turn helps to classify the vasculitis, Dr. Micheletti said.

When vasculitis affects small vessels, the skin findings will be palpable purpura, urticarial papules, vesicles, and petechiae, he said, adding that “The small vessel involvement accounts for the small size of the lesions, and complement cascade and inflammation account for the palpability of the lesions and the symptomatology.” As red blood cells extravasate from the affected vessels, nonblanching purpura develop, and gravity’s effect on the deposition of immune complex material dictates how lesions are distributed.

“Manifestations more typical of medium vessel vasculitis include subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, larger hemorrhagic bullae, and more significant ulceration and necrosis,” he said. “If such lesions are seen, suspect medium-vessel vasculitis or vasculitis overlapping small and medium vessels.” Cutaneous or systemic polyarteritis nodosa, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are examples, he added.

The particularities of renal manifestations of vasculitis also offer clues to the vessels involved. When a vasculitis patient has glomerulonephritis, suspect small-vessel involvement, Dr. Micheletti said. However, vasculitis affecting medium-sized vessels will cause renovascular hypertension and, potentially renal arterial aneurysms.

Nerves are typically spared in small-vessel vasculitis, while wrist or foot drop can be seen in mononeuritis multiplex.

Recently, the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) looked at more than 6,800 patients at over 130 sites around the world, proposing new classification criteria for ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) and large-vessel vasculitis. The study found that skin findings are common in AAV, with 30%-50% of cases presenting initially with skin lesions. Petechiae and/or purpura are the most common of the skin manifestations, he said. By contrast, for EGPA, allergic and nonspecific findings were the most common findings.

Although skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis in up to 94% of AAV cases, it’s underutilized and performed in less than half (24%-44%) of cases, Dr. Micheletti said. The study’s findings “demonstrate the importance of a good skin exam, as well as its utility for diagnosis” of vasculitis, he said.

An additional finding form the DCVAS study was that skin lesions can give clues to severity of vasculitis: “Among 1,184 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis, those with cutaneous involvement were more likely to have systemic manifestations of disease, more likely to have such severe manifestations as glomerulonephritis, alveolar hemorrhage, and mononeuritis,” said Dr. Micheletti, with a hazard ratio of 2.0 among those individuals who had EGPA or GPA.

“Skin findings have diagnostic and, potentially, prognostic importance,” he said. “Use the physician exam and your clinical acumen to your advantage,” but always confirm vasculitis with a biopsy. “Clinicopathologic correlation is key.” A simple urinalysis will screen for renal involvement, and is of “paramount importance,” he added.

Dr. Micheletti reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

AT WCD2019

Onychomycosis that fails terbinafine probably isn’t T. rubrum

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Severe influenza increases risk of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in the ICU

Severe influenza is an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with an accompanying increased mortality in the ICU, according to a multicenter retrospective cohort study at seven tertiary centers in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Data was collected from criteria-meeting adult patients admitted to the ICU for more than 24 hours with acute respiratory failure during the 2009-2016 influenza seasons. The included cohort of 432 patients was composed of 56% men and had a median age of 59 years; all participants were diagnosed as having severe type A or type B influenza infection according to positive airway RT-PCR results.

The full cohort was subcategorized into 117 immunocompromised and 315 as nonimmunocompromised individuals using criteria established by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study group (EORTC/MSG) . To assess influenza as an independent variable in the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, the 315 nonimmunocompromised influenza positive individuals were compared to an influenza-negative control group of 315 nonimmunocompromised patients admitted to the ICU that presented similar respiratory insufficiency symptoms with community-acquired pneumonia.

Determination of other independent risk factors for incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was achieved by multivariate analysis of factors such as sex, diabetes status, prednisone use, age, and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score. The mean APACHE II score was 22, with the majority of patients requiring intubation for mechanical ventilation for a median duration of 11 days.

Influenza is not considered a host factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and will often miss being diagnosed when using strict interpretation of the current EORTC/MSG or AspICU algorithm criteria, according to the researchers. Consequently for patients with influenza and the noninfluenza control group with community-acquired pneumonia, the definition of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was modified from the AspICU algorithm. Stringent mycological criteria, including bronchoaveolar lavage (BAL) culture, a positive Aspergillus culture, positive galactomannan test, and/or positive serum galactomannan tests, provided supporting diagnostics for an invasive pulmonary aspergillosis determination.

At a median of 3 days following admission to the ICU, a diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was determined for 19% of the 432 influenza patients. Similar incident percentages of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurring for type A and type B, 71/355 (20%) and 12/77 (16%) patients respectively, showed that there was no clear association of the disease development with influenza subtypes that occurred during different annual seasons.

AspICU or EORTC/MSG criteria characterized only 43% and 58% of cases as proven or possible aspergillosis, respectively. On the other hand, stringent mycological tests yielded better invasive pulmonary aspergillosis classification, with 63% of BAL cultures being positive for Aspergillus, 88% of BAL galactomannan tests being positive, and 65% of serum galactomannan tests being positive in the 81/83 patients tested.

The study found that, for influenza patients, being immunocompromised more than doubled the incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, at 32% versus the 14% of those patients who were nonimmunocompromised. In contrast only 5% in the control group developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Influenza patients who developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in the ICU tended to have their stays significantly lengthened from 9 days (interquartile range, 5-20 days) for those without it to 19 days (IQR, 12-38 days) for those infected (P less than .0001). Likewise, 90-day mortality significantly rose from 28% for those influenza patients without invasive pulmonary aspergillosis to 51% for those with it (P = .0001).

The authors concluded that influenza was “independently associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (adjusted odds ratio, 5.19; P less than.0001) along with a higher APACHE II score, male sex, and use of corticosteroids.”

Furthermore, as influenza appears to be an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its associated high mortality, the authors suggested that “future studies should assess whether a faster diagnosis or antifungal prophylaxis could improve the outcome of influenza-associated aspergillosis.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schauwvlieghe AFAD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jul 31. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1

Severe influenza is an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with an accompanying increased mortality in the ICU, according to a multicenter retrospective cohort study at seven tertiary centers in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Data was collected from criteria-meeting adult patients admitted to the ICU for more than 24 hours with acute respiratory failure during the 2009-2016 influenza seasons. The included cohort of 432 patients was composed of 56% men and had a median age of 59 years; all participants were diagnosed as having severe type A or type B influenza infection according to positive airway RT-PCR results.

The full cohort was subcategorized into 117 immunocompromised and 315 as nonimmunocompromised individuals using criteria established by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study group (EORTC/MSG) . To assess influenza as an independent variable in the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, the 315 nonimmunocompromised influenza positive individuals were compared to an influenza-negative control group of 315 nonimmunocompromised patients admitted to the ICU that presented similar respiratory insufficiency symptoms with community-acquired pneumonia.

Determination of other independent risk factors for incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was achieved by multivariate analysis of factors such as sex, diabetes status, prednisone use, age, and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score. The mean APACHE II score was 22, with the majority of patients requiring intubation for mechanical ventilation for a median duration of 11 days.

Influenza is not considered a host factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and will often miss being diagnosed when using strict interpretation of the current EORTC/MSG or AspICU algorithm criteria, according to the researchers. Consequently for patients with influenza and the noninfluenza control group with community-acquired pneumonia, the definition of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was modified from the AspICU algorithm. Stringent mycological criteria, including bronchoaveolar lavage (BAL) culture, a positive Aspergillus culture, positive galactomannan test, and/or positive serum galactomannan tests, provided supporting diagnostics for an invasive pulmonary aspergillosis determination.

At a median of 3 days following admission to the ICU, a diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was determined for 19% of the 432 influenza patients. Similar incident percentages of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurring for type A and type B, 71/355 (20%) and 12/77 (16%) patients respectively, showed that there was no clear association of the disease development with influenza subtypes that occurred during different annual seasons.

AspICU or EORTC/MSG criteria characterized only 43% and 58% of cases as proven or possible aspergillosis, respectively. On the other hand, stringent mycological tests yielded better invasive pulmonary aspergillosis classification, with 63% of BAL cultures being positive for Aspergillus, 88% of BAL galactomannan tests being positive, and 65% of serum galactomannan tests being positive in the 81/83 patients tested.

The study found that, for influenza patients, being immunocompromised more than doubled the incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, at 32% versus the 14% of those patients who were nonimmunocompromised. In contrast only 5% in the control group developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Influenza patients who developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in the ICU tended to have their stays significantly lengthened from 9 days (interquartile range, 5-20 days) for those without it to 19 days (IQR, 12-38 days) for those infected (P less than .0001). Likewise, 90-day mortality significantly rose from 28% for those influenza patients without invasive pulmonary aspergillosis to 51% for those with it (P = .0001).

The authors concluded that influenza was “independently associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (adjusted odds ratio, 5.19; P less than.0001) along with a higher APACHE II score, male sex, and use of corticosteroids.”

Furthermore, as influenza appears to be an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its associated high mortality, the authors suggested that “future studies should assess whether a faster diagnosis or antifungal prophylaxis could improve the outcome of influenza-associated aspergillosis.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schauwvlieghe AFAD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jul 31. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1

Severe influenza is an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with an accompanying increased mortality in the ICU, according to a multicenter retrospective cohort study at seven tertiary centers in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Data was collected from criteria-meeting adult patients admitted to the ICU for more than 24 hours with acute respiratory failure during the 2009-2016 influenza seasons. The included cohort of 432 patients was composed of 56% men and had a median age of 59 years; all participants were diagnosed as having severe type A or type B influenza infection according to positive airway RT-PCR results.

The full cohort was subcategorized into 117 immunocompromised and 315 as nonimmunocompromised individuals using criteria established by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study group (EORTC/MSG) . To assess influenza as an independent variable in the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, the 315 nonimmunocompromised influenza positive individuals were compared to an influenza-negative control group of 315 nonimmunocompromised patients admitted to the ICU that presented similar respiratory insufficiency symptoms with community-acquired pneumonia.

Determination of other independent risk factors for incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was achieved by multivariate analysis of factors such as sex, diabetes status, prednisone use, age, and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score. The mean APACHE II score was 22, with the majority of patients requiring intubation for mechanical ventilation for a median duration of 11 days.

Influenza is not considered a host factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and will often miss being diagnosed when using strict interpretation of the current EORTC/MSG or AspICU algorithm criteria, according to the researchers. Consequently for patients with influenza and the noninfluenza control group with community-acquired pneumonia, the definition of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was modified from the AspICU algorithm. Stringent mycological criteria, including bronchoaveolar lavage (BAL) culture, a positive Aspergillus culture, positive galactomannan test, and/or positive serum galactomannan tests, provided supporting diagnostics for an invasive pulmonary aspergillosis determination.

At a median of 3 days following admission to the ICU, a diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was determined for 19% of the 432 influenza patients. Similar incident percentages of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurring for type A and type B, 71/355 (20%) and 12/77 (16%) patients respectively, showed that there was no clear association of the disease development with influenza subtypes that occurred during different annual seasons.

AspICU or EORTC/MSG criteria characterized only 43% and 58% of cases as proven or possible aspergillosis, respectively. On the other hand, stringent mycological tests yielded better invasive pulmonary aspergillosis classification, with 63% of BAL cultures being positive for Aspergillus, 88% of BAL galactomannan tests being positive, and 65% of serum galactomannan tests being positive in the 81/83 patients tested.

The study found that, for influenza patients, being immunocompromised more than doubled the incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, at 32% versus the 14% of those patients who were nonimmunocompromised. In contrast only 5% in the control group developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Influenza patients who developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in the ICU tended to have their stays significantly lengthened from 9 days (interquartile range, 5-20 days) for those without it to 19 days (IQR, 12-38 days) for those infected (P less than .0001). Likewise, 90-day mortality significantly rose from 28% for those influenza patients without invasive pulmonary aspergillosis to 51% for those with it (P = .0001).

The authors concluded that influenza was “independently associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (adjusted odds ratio, 5.19; P less than.0001) along with a higher APACHE II score, male sex, and use of corticosteroids.”

Furthermore, as influenza appears to be an independent risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its associated high mortality, the authors suggested that “future studies should assess whether a faster diagnosis or antifungal prophylaxis could improve the outcome of influenza-associated aspergillosis.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schauwvlieghe AFAD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jul 31. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Key clinical point: ICU admission for severe influenza as significant a risk factor should be included in the existing diagnostic criteria for predicting incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Major finding: Influenza is an independent risk factor associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, with 90-day mortality rising from 28% to 51% when this fungal infection occurs.

Study details: Multicenter retrospective study of 432 adult patients with confirmed severe influenza admitted to the ICU with acute respiratory failure.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Schauwvlieghe AFAD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jul 31. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1.

NYC outbreak of Candida auris linked to 45% mortality

Mortality within 90 days of infection was 45% among 51 patients diagnosed with antibiotic-resistant Candida auris infections in a multihospital outbreak in New York City from 2012 to 2017.

Transmission is ongoing in health care facilities, primarily among patients with extensive health care exposures, according to a report published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Intensive infection prevention and control efforts continue; the goals are delaying endemicity, preventing outbreaks within facilities, reducing transmission and geographic spread, and blunting the effect of C. auris in New York and the rest of the United States,” Eleanor Adams, MD, of the New York Health Department, and her colleagues wrote. “Among medically fragile patients in NYC who had a history of extensive contact with health care facilities, clinicians should include C. auris in the differential diagnosis for patients with symptoms compatible with bloodstream infection.”

In the intensive case-patient analysis conducted by the New York State Health Department, 21 cases were from seven hospitals in Brooklyn, 16 were from three hospitals and one private medical office in Queens, 12 were from five hospitals and one long-term acute care hospital in Manhattan, and 1 was from a hospital in the Bronx. The remaining clinical case was identified in a western New York hospital in a patient who had recently been admitted to an involved Brooklyn hospital.

Among these patients, 31 (61%) had resided in long-term care facilities immediately before being admitted to the hospital in which their infection was diagnosed, and 19 of these 31 resided in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator beds; 1 (2%) resided in a long-term acute care hospital; 5 (10%) had been transferred from another hospital; and 4 (8%) had traveled internationally within 5 years before diagnosis, according to the investigators.

Isolates from 50 patients (98%) were resistant to fluconazole and 13 (25%) were resistant to fluconazole and amphotericin B. No initial isolates were resistant to echinocandins, although subsequent isolates obtained from 3 persons who had received an echinocandin acquired resistance to it, according to the researchers. Whole-genome sequencing performed at The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that 50 of 51 isolates belonged to a South Asia clade; the remaining isolate was the only one susceptible to fluconazole.

The work was supported by the CDC. No disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Adams E et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Sep 12; 24(10); ID: 18-0649.

Mortality within 90 days of infection was 45% among 51 patients diagnosed with antibiotic-resistant Candida auris infections in a multihospital outbreak in New York City from 2012 to 2017.

Transmission is ongoing in health care facilities, primarily among patients with extensive health care exposures, according to a report published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Intensive infection prevention and control efforts continue; the goals are delaying endemicity, preventing outbreaks within facilities, reducing transmission and geographic spread, and blunting the effect of C. auris in New York and the rest of the United States,” Eleanor Adams, MD, of the New York Health Department, and her colleagues wrote. “Among medically fragile patients in NYC who had a history of extensive contact with health care facilities, clinicians should include C. auris in the differential diagnosis for patients with symptoms compatible with bloodstream infection.”

In the intensive case-patient analysis conducted by the New York State Health Department, 21 cases were from seven hospitals in Brooklyn, 16 were from three hospitals and one private medical office in Queens, 12 were from five hospitals and one long-term acute care hospital in Manhattan, and 1 was from a hospital in the Bronx. The remaining clinical case was identified in a western New York hospital in a patient who had recently been admitted to an involved Brooklyn hospital.

Among these patients, 31 (61%) had resided in long-term care facilities immediately before being admitted to the hospital in which their infection was diagnosed, and 19 of these 31 resided in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator beds; 1 (2%) resided in a long-term acute care hospital; 5 (10%) had been transferred from another hospital; and 4 (8%) had traveled internationally within 5 years before diagnosis, according to the investigators.

Isolates from 50 patients (98%) were resistant to fluconazole and 13 (25%) were resistant to fluconazole and amphotericin B. No initial isolates were resistant to echinocandins, although subsequent isolates obtained from 3 persons who had received an echinocandin acquired resistance to it, according to the researchers. Whole-genome sequencing performed at The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that 50 of 51 isolates belonged to a South Asia clade; the remaining isolate was the only one susceptible to fluconazole.

The work was supported by the CDC. No disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Adams E et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Sep 12; 24(10); ID: 18-0649.

Mortality within 90 days of infection was 45% among 51 patients diagnosed with antibiotic-resistant Candida auris infections in a multihospital outbreak in New York City from 2012 to 2017.

Transmission is ongoing in health care facilities, primarily among patients with extensive health care exposures, according to a report published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Intensive infection prevention and control efforts continue; the goals are delaying endemicity, preventing outbreaks within facilities, reducing transmission and geographic spread, and blunting the effect of C. auris in New York and the rest of the United States,” Eleanor Adams, MD, of the New York Health Department, and her colleagues wrote. “Among medically fragile patients in NYC who had a history of extensive contact with health care facilities, clinicians should include C. auris in the differential diagnosis for patients with symptoms compatible with bloodstream infection.”

In the intensive case-patient analysis conducted by the New York State Health Department, 21 cases were from seven hospitals in Brooklyn, 16 were from three hospitals and one private medical office in Queens, 12 were from five hospitals and one long-term acute care hospital in Manhattan, and 1 was from a hospital in the Bronx. The remaining clinical case was identified in a western New York hospital in a patient who had recently been admitted to an involved Brooklyn hospital.

Among these patients, 31 (61%) had resided in long-term care facilities immediately before being admitted to the hospital in which their infection was diagnosed, and 19 of these 31 resided in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator beds; 1 (2%) resided in a long-term acute care hospital; 5 (10%) had been transferred from another hospital; and 4 (8%) had traveled internationally within 5 years before diagnosis, according to the investigators.

Isolates from 50 patients (98%) were resistant to fluconazole and 13 (25%) were resistant to fluconazole and amphotericin B. No initial isolates were resistant to echinocandins, although subsequent isolates obtained from 3 persons who had received an echinocandin acquired resistance to it, according to the researchers. Whole-genome sequencing performed at The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that 50 of 51 isolates belonged to a South Asia clade; the remaining isolate was the only one susceptible to fluconazole.

The work was supported by the CDC. No disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Adams E et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Sep 12; 24(10); ID: 18-0649.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

So it’s pediatric onychomycosis. Now what?

CHICAGO – Though research shows that nail fungus occurs in just 0.3% of pediatric patients in the United States, that’s not what Sheila Friedlander, MD, is seeing in her southern California practice, where it’s not uncommon to see children whose nails, toe nails in particular, have fungal involvement.

said Dr. Friedlander during a nail-focused session at the annual summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr. Friedlander, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, said that she suspects that more participation in organized sports at a young age may be contributing to the increase, with occlusive sports footwear replacing bare feet or sandals for more hours of the day, presenting more opportunities for toenail trauma in sports such as soccer.

When making the clinical call about a nail problem, bear in mind that the younger the child, the less likely a nail problem is fungal, Dr. Friedlander noted. “Little children are much less likely than older children to have nail fungus. Pediatric nails are thinner, and they are faster growing, with better blood supply to the matrix.”

And if frank onychomadesis is observed, think about the time of year, and ask about recent fevers and rashes, because coxsackievirus may be the culprit. “Be not afraid, and look everywhere if the nail is confusing to you,” she said. In all ages, the diagnosis is primarily clinical, “but I culture them, I ‘PAS’ [periodic acid-Schiff stain] them, too. If you do both, you’ll increase your yield,” Dr. Friedlander said, adding, “the beauty of PAS is you can use it to give your families an answer very soon.”

Once you’ve established that fungus is to blame for a nail problem, there’s a conundrum: There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies, either topical or systemic, for pediatric onychomycosis, Dr. Friedlander said. She, along with coauthors and first author Aditya Gupta, MD, of Mediprobe Research, London, Ontario, Canada, recently published an article reviewing the safety and efficacy of antifungal agents in this age group (Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1111/pde.13561).

Reviewing information available in the United States and Canada, Dr. Friedlander and her coauthors came up with three topical and four oral options for children, along with recommendations for dosage and duration.

In response to an audience question about the use of topical antifungal treatment for nail involvement, Dr. Friedlander responded, “I think topicals would be great for kids, but it’s for kids where there is no nail matrix involvement. Also, cost is a problem. Nobody will cover it. But some families are willing to do this to avoid systemic therapy,” and if the family budget can accommodate a topical choice, it’s a logical option, she said, noting that partial reimbursement via a coupon system is available from some pharmaceutical companies.

Where appropriate, ciclopirox 8%, efinaconazole 10%, and tavaborole 5% can each be considered. Dr. Friedlander cited one study she coauthored, which reported that 70% of pediatric participants with nonmatrix onychomycosis saw effective treatment, with a 71% mycological cure rate (P = .03), after 32 weeks of treatment with ciclopirox lacquer versus vehicle (Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 May-Jun;30[3]:316-22).

Systemic therapies – which, when studied, have been given at tinea capitis doses – could include griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole.

In terms of oral options, Dr. Friedlander said, griseofulvin has some practical limitations. While prolonged treatment is required in any case, terbinafine may produce results in about 3 months, whereas griseofulvin may require up to 9 months of therapy. “I always try to use terbinafine … griseofulvin takes a year and a day,” she said.

She also shared some tips to improve pediatric adherence with oral antifungals: “You can tell parents to crush terbinafine tablets and mix in peanut butter or applesauce to improve adherence. Griseofulvin can be flavored by the pharmacy, but volumes are big with griseofulvin, so it’s a challenge to get kids to take it all,” she said.

Dr. Friedlander reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

CHICAGO – Though research shows that nail fungus occurs in just 0.3% of pediatric patients in the United States, that’s not what Sheila Friedlander, MD, is seeing in her southern California practice, where it’s not uncommon to see children whose nails, toe nails in particular, have fungal involvement.

said Dr. Friedlander during a nail-focused session at the annual summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr. Friedlander, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, said that she suspects that more participation in organized sports at a young age may be contributing to the increase, with occlusive sports footwear replacing bare feet or sandals for more hours of the day, presenting more opportunities for toenail trauma in sports such as soccer.

When making the clinical call about a nail problem, bear in mind that the younger the child, the less likely a nail problem is fungal, Dr. Friedlander noted. “Little children are much less likely than older children to have nail fungus. Pediatric nails are thinner, and they are faster growing, with better blood supply to the matrix.”

And if frank onychomadesis is observed, think about the time of year, and ask about recent fevers and rashes, because coxsackievirus may be the culprit. “Be not afraid, and look everywhere if the nail is confusing to you,” she said. In all ages, the diagnosis is primarily clinical, “but I culture them, I ‘PAS’ [periodic acid-Schiff stain] them, too. If you do both, you’ll increase your yield,” Dr. Friedlander said, adding, “the beauty of PAS is you can use it to give your families an answer very soon.”

Once you’ve established that fungus is to blame for a nail problem, there’s a conundrum: There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies, either topical or systemic, for pediatric onychomycosis, Dr. Friedlander said. She, along with coauthors and first author Aditya Gupta, MD, of Mediprobe Research, London, Ontario, Canada, recently published an article reviewing the safety and efficacy of antifungal agents in this age group (Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1111/pde.13561).

Reviewing information available in the United States and Canada, Dr. Friedlander and her coauthors came up with three topical and four oral options for children, along with recommendations for dosage and duration.

In response to an audience question about the use of topical antifungal treatment for nail involvement, Dr. Friedlander responded, “I think topicals would be great for kids, but it’s for kids where there is no nail matrix involvement. Also, cost is a problem. Nobody will cover it. But some families are willing to do this to avoid systemic therapy,” and if the family budget can accommodate a topical choice, it’s a logical option, she said, noting that partial reimbursement via a coupon system is available from some pharmaceutical companies.

Where appropriate, ciclopirox 8%, efinaconazole 10%, and tavaborole 5% can each be considered. Dr. Friedlander cited one study she coauthored, which reported that 70% of pediatric participants with nonmatrix onychomycosis saw effective treatment, with a 71% mycological cure rate (P = .03), after 32 weeks of treatment with ciclopirox lacquer versus vehicle (Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 May-Jun;30[3]:316-22).

Systemic therapies – which, when studied, have been given at tinea capitis doses – could include griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole.

In terms of oral options, Dr. Friedlander said, griseofulvin has some practical limitations. While prolonged treatment is required in any case, terbinafine may produce results in about 3 months, whereas griseofulvin may require up to 9 months of therapy. “I always try to use terbinafine … griseofulvin takes a year and a day,” she said.

She also shared some tips to improve pediatric adherence with oral antifungals: “You can tell parents to crush terbinafine tablets and mix in peanut butter or applesauce to improve adherence. Griseofulvin can be flavored by the pharmacy, but volumes are big with griseofulvin, so it’s a challenge to get kids to take it all,” she said.

Dr. Friedlander reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

CHICAGO – Though research shows that nail fungus occurs in just 0.3% of pediatric patients in the United States, that’s not what Sheila Friedlander, MD, is seeing in her southern California practice, where it’s not uncommon to see children whose nails, toe nails in particular, have fungal involvement.

said Dr. Friedlander during a nail-focused session at the annual summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr. Friedlander, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, said that she suspects that more participation in organized sports at a young age may be contributing to the increase, with occlusive sports footwear replacing bare feet or sandals for more hours of the day, presenting more opportunities for toenail trauma in sports such as soccer.

When making the clinical call about a nail problem, bear in mind that the younger the child, the less likely a nail problem is fungal, Dr. Friedlander noted. “Little children are much less likely than older children to have nail fungus. Pediatric nails are thinner, and they are faster growing, with better blood supply to the matrix.”

And if frank onychomadesis is observed, think about the time of year, and ask about recent fevers and rashes, because coxsackievirus may be the culprit. “Be not afraid, and look everywhere if the nail is confusing to you,” she said. In all ages, the diagnosis is primarily clinical, “but I culture them, I ‘PAS’ [periodic acid-Schiff stain] them, too. If you do both, you’ll increase your yield,” Dr. Friedlander said, adding, “the beauty of PAS is you can use it to give your families an answer very soon.”

Once you’ve established that fungus is to blame for a nail problem, there’s a conundrum: There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies, either topical or systemic, for pediatric onychomycosis, Dr. Friedlander said. She, along with coauthors and first author Aditya Gupta, MD, of Mediprobe Research, London, Ontario, Canada, recently published an article reviewing the safety and efficacy of antifungal agents in this age group (Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1111/pde.13561).

Reviewing information available in the United States and Canada, Dr. Friedlander and her coauthors came up with three topical and four oral options for children, along with recommendations for dosage and duration.

In response to an audience question about the use of topical antifungal treatment for nail involvement, Dr. Friedlander responded, “I think topicals would be great for kids, but it’s for kids where there is no nail matrix involvement. Also, cost is a problem. Nobody will cover it. But some families are willing to do this to avoid systemic therapy,” and if the family budget can accommodate a topical choice, it’s a logical option, she said, noting that partial reimbursement via a coupon system is available from some pharmaceutical companies.

Where appropriate, ciclopirox 8%, efinaconazole 10%, and tavaborole 5% can each be considered. Dr. Friedlander cited one study she coauthored, which reported that 70% of pediatric participants with nonmatrix onychomycosis saw effective treatment, with a 71% mycological cure rate (P = .03), after 32 weeks of treatment with ciclopirox lacquer versus vehicle (Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 May-Jun;30[3]:316-22).

Systemic therapies – which, when studied, have been given at tinea capitis doses – could include griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole.

In terms of oral options, Dr. Friedlander said, griseofulvin has some practical limitations. While prolonged treatment is required in any case, terbinafine may produce results in about 3 months, whereas griseofulvin may require up to 9 months of therapy. “I always try to use terbinafine … griseofulvin takes a year and a day,” she said.

She also shared some tips to improve pediatric adherence with oral antifungals: “You can tell parents to crush terbinafine tablets and mix in peanut butter or applesauce to improve adherence. Griseofulvin can be flavored by the pharmacy, but volumes are big with griseofulvin, so it’s a challenge to get kids to take it all,” she said.

Dr. Friedlander reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2018

Less is more: Nanotechnology enhances antifungal’s efficacy

The use of nanotechnology significantly reduced the amount of efinaconazole needed to effectively treat nail fungus in a study that pitted nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles combined with the antifungal against reference strains of Trichophyton rubrum.

Efinaconazole has demonstrated effectiveness as a topical treatment for T. rubrum, but treatment can be expensive, with a single 4-mL bottle costing $691 at a major chain pharmacy, wrote Caroline B. Costa-Orlandi, PhD, of Universidade Estadual Paulista, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, an international research team evaluated topical efinaconazole and topical terbinafine, each combined with previously characterized, nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles (NO-np) in a checkerboard design, to attack two reference strains of T. rubrum, ATCC MYA-4438 and ATCC 28189. NO-np was combined with 10% efinaconazole or with terbinafine.

The combination of NO-np and efinaconazole reduced the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of efinaconazole by 16 times compared with treatment alone against ATCC MYA-4438; by 4 times when combined against ATCC 28189. With NO-np plus terbinafine, MICs against ATCC 28189 and ATCC MYA-4438 were reduced by four- and twofold, respectively, when compared with terbinafine alone. These data follow recently published findings in a study cited by the authors that demonstrated that NO-np is superior to topical terbinafine 1% cream in clearing infection in a mouse model of deep dermal dermatophytosis, suggesting that the combination may be even more effective (Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct;13[7]:2267-70).

“What we found was that we could impart the same antifungal activity at the highest concentrations tested of either alone by combining them at a fraction of these concentrations,” corresponding author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said in a press release issued by the university. The impact of this combination, “which we visualized using electron microscopy as compared to either product alone, highlighted their synergistic damaging effects at concentrations that would be completely safe to human cells,” he added.

Other benefits of NO-np include low cost, safety, ease of use, reduced likelihood for the development of antimicrobial resistance, and proven efficacy against other dermatophyte infections, the researchers noted.

The findings support the potential value of further research to evaluate nanoparticles combined with topical antifungals in a clinical setting, they said.

Dr. Costa-Orlandi had no financial conflicts to disclose. Authors Adam Friedman, MD, and Joel Friedman, MD, are coinventors of the nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles used in the study. Dr. Adam Friedman is on the advisory board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Costa-Orlandi C et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):717-20.

The use of nanotechnology significantly reduced the amount of efinaconazole needed to effectively treat nail fungus in a study that pitted nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles combined with the antifungal against reference strains of Trichophyton rubrum.

Efinaconazole has demonstrated effectiveness as a topical treatment for T. rubrum, but treatment can be expensive, with a single 4-mL bottle costing $691 at a major chain pharmacy, wrote Caroline B. Costa-Orlandi, PhD, of Universidade Estadual Paulista, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, an international research team evaluated topical efinaconazole and topical terbinafine, each combined with previously characterized, nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles (NO-np) in a checkerboard design, to attack two reference strains of T. rubrum, ATCC MYA-4438 and ATCC 28189. NO-np was combined with 10% efinaconazole or with terbinafine.

The combination of NO-np and efinaconazole reduced the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of efinaconazole by 16 times compared with treatment alone against ATCC MYA-4438; by 4 times when combined against ATCC 28189. With NO-np plus terbinafine, MICs against ATCC 28189 and ATCC MYA-4438 were reduced by four- and twofold, respectively, when compared with terbinafine alone. These data follow recently published findings in a study cited by the authors that demonstrated that NO-np is superior to topical terbinafine 1% cream in clearing infection in a mouse model of deep dermal dermatophytosis, suggesting that the combination may be even more effective (Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct;13[7]:2267-70).

“What we found was that we could impart the same antifungal activity at the highest concentrations tested of either alone by combining them at a fraction of these concentrations,” corresponding author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said in a press release issued by the university. The impact of this combination, “which we visualized using electron microscopy as compared to either product alone, highlighted their synergistic damaging effects at concentrations that would be completely safe to human cells,” he added.

Other benefits of NO-np include low cost, safety, ease of use, reduced likelihood for the development of antimicrobial resistance, and proven efficacy against other dermatophyte infections, the researchers noted.

The findings support the potential value of further research to evaluate nanoparticles combined with topical antifungals in a clinical setting, they said.

Dr. Costa-Orlandi had no financial conflicts to disclose. Authors Adam Friedman, MD, and Joel Friedman, MD, are coinventors of the nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles used in the study. Dr. Adam Friedman is on the advisory board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Costa-Orlandi C et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):717-20.

The use of nanotechnology significantly reduced the amount of efinaconazole needed to effectively treat nail fungus in a study that pitted nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles combined with the antifungal against reference strains of Trichophyton rubrum.

Efinaconazole has demonstrated effectiveness as a topical treatment for T. rubrum, but treatment can be expensive, with a single 4-mL bottle costing $691 at a major chain pharmacy, wrote Caroline B. Costa-Orlandi, PhD, of Universidade Estadual Paulista, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, an international research team evaluated topical efinaconazole and topical terbinafine, each combined with previously characterized, nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles (NO-np) in a checkerboard design, to attack two reference strains of T. rubrum, ATCC MYA-4438 and ATCC 28189. NO-np was combined with 10% efinaconazole or with terbinafine.

The combination of NO-np and efinaconazole reduced the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of efinaconazole by 16 times compared with treatment alone against ATCC MYA-4438; by 4 times when combined against ATCC 28189. With NO-np plus terbinafine, MICs against ATCC 28189 and ATCC MYA-4438 were reduced by four- and twofold, respectively, when compared with terbinafine alone. These data follow recently published findings in a study cited by the authors that demonstrated that NO-np is superior to topical terbinafine 1% cream in clearing infection in a mouse model of deep dermal dermatophytosis, suggesting that the combination may be even more effective (Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct;13[7]:2267-70).

“What we found was that we could impart the same antifungal activity at the highest concentrations tested of either alone by combining them at a fraction of these concentrations,” corresponding author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said in a press release issued by the university. The impact of this combination, “which we visualized using electron microscopy as compared to either product alone, highlighted their synergistic damaging effects at concentrations that would be completely safe to human cells,” he added.

Other benefits of NO-np include low cost, safety, ease of use, reduced likelihood for the development of antimicrobial resistance, and proven efficacy against other dermatophyte infections, the researchers noted.

The findings support the potential value of further research to evaluate nanoparticles combined with topical antifungals in a clinical setting, they said.

Dr. Costa-Orlandi had no financial conflicts to disclose. Authors Adam Friedman, MD, and Joel Friedman, MD, are coinventors of the nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles used in the study. Dr. Adam Friedman is on the advisory board of Dermatology News.

SOURCE: Costa-Orlandi C et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):717-20.

FROM JOURNAL OF DRUGS IN DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Adding nanoparticles to antifungal medication improved the drug’s effectiveness and reduced the amount needed.

Major finding: Efinaconazole combined with nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles reduced the antifungal’s minimum inhibitory concentration 16-fold, compared with the antifungal alone against T. rubrum reference strains.

Study details: The data come from an in vitro analysis of nanoparticle-enhanced efinaconazole or terbinafine against T. rubrum.

Disclosures: Dr. Costa-Orlandi had no financial conflicts to disclose. Coauthors Dr. Adam Friedman and Dr. Joel Friedman are coinventors of the nitric oxide–releasing nanoparticles used in the study.

Source: Costa-Orlandi C et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):717-20.

VIDEO: Device-based therapy for onychomycosis

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

SAN DIEGO – which has been studied in two clinical trials and case series, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where she presented on this topic.

“Something that we’re looking at is plasma treatment of onychomycosis basically using ionized gas,” which has been shown to inhibit the growth of Trichophyton rubrum in vitro, added Dr. Lipner of the department of dermatology, Cornell University, New York.

In a pilot study of 19 patients with onychomycosis, she and her associates found that the clinical cure with nonthermal plasma was about 50% and the mycological cure rate was 15%, “and we’re now trying to improve efficacy using this device,” she said (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Apr;42[3]:295-8). With a dielectric insulator, “nonthermal plasma is created by short pulses (about 10 ns) of strong (about 20 kV/mm peak) electric field that ionizes air molecules, creating ions and electrons, as well as ozone, hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide,” according to the description in the study.

Other device-based therapies include iontophoresis, using electrical currents to increase drug delivery, and creating small punch biopsies or using a device to create “microholes” in the nails to increase delivery of topical medication across the nail, Dr. Lipner said.

Patients often ask about another device-based treatment, laser therapy, which she pointed out is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cure, but for a temporary increase in clear nail in patients with onychomycosis, “very different” than the criteria used for topical and systemic medications, making it difficult to compare efficacy data between lasers and medications, she noted.

Dr. Lipner reported receiving grants/research funding from MOE Medical Devices.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

SAN DIEGO – which has been studied in two clinical trials and case series, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where she presented on this topic.

“Something that we’re looking at is plasma treatment of onychomycosis basically using ionized gas,” which has been shown to inhibit the growth of Trichophyton rubrum in vitro, added Dr. Lipner of the department of dermatology, Cornell University, New York.

In a pilot study of 19 patients with onychomycosis, she and her associates found that the clinical cure with nonthermal plasma was about 50% and the mycological cure rate was 15%, “and we’re now trying to improve efficacy using this device,” she said (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Apr;42[3]:295-8). With a dielectric insulator, “nonthermal plasma is created by short pulses (about 10 ns) of strong (about 20 kV/mm peak) electric field that ionizes air molecules, creating ions and electrons, as well as ozone, hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide,” according to the description in the study.

Other device-based therapies include iontophoresis, using electrical currents to increase drug delivery, and creating small punch biopsies or using a device to create “microholes” in the nails to increase delivery of topical medication across the nail, Dr. Lipner said.

Patients often ask about another device-based treatment, laser therapy, which she pointed out is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cure, but for a temporary increase in clear nail in patients with onychomycosis, “very different” than the criteria used for topical and systemic medications, making it difficult to compare efficacy data between lasers and medications, she noted.

Dr. Lipner reported receiving grants/research funding from MOE Medical Devices.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

SAN DIEGO – which has been studied in two clinical trials and case series, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where she presented on this topic.

“Something that we’re looking at is plasma treatment of onychomycosis basically using ionized gas,” which has been shown to inhibit the growth of Trichophyton rubrum in vitro, added Dr. Lipner of the department of dermatology, Cornell University, New York.

In a pilot study of 19 patients with onychomycosis, she and her associates found that the clinical cure with nonthermal plasma was about 50% and the mycological cure rate was 15%, “and we’re now trying to improve efficacy using this device,” she said (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Apr;42[3]:295-8). With a dielectric insulator, “nonthermal plasma is created by short pulses (about 10 ns) of strong (about 20 kV/mm peak) electric field that ionizes air molecules, creating ions and electrons, as well as ozone, hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide,” according to the description in the study.

Other device-based therapies include iontophoresis, using electrical currents to increase drug delivery, and creating small punch biopsies or using a device to create “microholes” in the nails to increase delivery of topical medication across the nail, Dr. Lipner said.

Patients often ask about another device-based treatment, laser therapy, which she pointed out is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cure, but for a temporary increase in clear nail in patients with onychomycosis, “very different” than the criteria used for topical and systemic medications, making it difficult to compare efficacy data between lasers and medications, she noted.

Dr. Lipner reported receiving grants/research funding from MOE Medical Devices.

Ibrutinib linked to invasive fungal infections

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) may be associated with early-onset invasive fungal infections (IFI) in patients with hematologic malignancies, investigators caution.

French investigators identified 33 cases of invasive fungal infections occurring among patients who had been treated with ibrutinib as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. Of the 33 cases, 27 were invasive aspergillosis, and 40% of these were localized in the central nervous system. The findings were published in the journal Blood.

“IFI tend to occur within the first months of treatment and are infrequent thereafter. Whilst it seems difficult at this point to advocate for systematic antifungal prophylaxis in all patients, an increased awareness about the potential risk of IFI after initiating ibrutinib is warranted, especially when other predisposing factors are associated,” wrote David Ghez, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the Gustave Roussy Institute in Villejuif and other centers in France.

Although ibrutinib, an inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, is generally considered to be less immunosuppressive than other therapies, it was associated with five cases of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with ibrutinib monotherapy in a 2016 report (Blood. 2016;128:1940-3). Of these five patients, four were treatment naive, suggesting that ibrutinib itself could increase risk for invasive opportunistic infections, Dr. Ghez and his colleagues noted.

Based on this finding and on case reports of invasive infections in other patients being treated with ibrutinib, the authors conducted a retrospective survey of centers in the French Innovative Leukemia Organization CLL group.

They identified 33 cases, including 30 patients with CLL (15 of whom had deleterious 17p deletions), 1 with mantle cell lymphoma, and 2 with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia.

Invasive aspergillosis accounted for 27 of the 33 cases, and 11 cases had CNS localization. There were four cases of disseminated cryptococcosis, and one each of mucormycosis and pneumocystis pneumonia.

The median time between the start of ibrutinib therapy and a diagnosis of invasive fungal infection was 3 months, with some cases occurring as early as 1 month, and others occurring 30 months out. However, the majority of cases – 28 – were diagnosed within 6 months of the start of therapy, including 20 that occurred within 3 months of ibrutinib initiation.

In 21 patients, the diagnosis of an invasive fungal infection led to drug discontinuation. In the remaining patients, the drug was either resumed after resolution of the IFI, or continued at a lower dose because of potential for interaction between ibrutinib and the antifungal agent voriconazole.

Dr. Ghez reported receiving a research grant from Janssen, and coauthor Loic Ysebaert, MD, PhD, reported consultancy fees from the company. All other authors declared no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Ghez D et al., Blood. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-818286.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) may be associated with early-onset invasive fungal infections (IFI) in patients with hematologic malignancies, investigators caution.

French investigators identified 33 cases of invasive fungal infections occurring among patients who had been treated with ibrutinib as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. Of the 33 cases, 27 were invasive aspergillosis, and 40% of these were localized in the central nervous system. The findings were published in the journal Blood.

“IFI tend to occur within the first months of treatment and are infrequent thereafter. Whilst it seems difficult at this point to advocate for systematic antifungal prophylaxis in all patients, an increased awareness about the potential risk of IFI after initiating ibrutinib is warranted, especially when other predisposing factors are associated,” wrote David Ghez, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the Gustave Roussy Institute in Villejuif and other centers in France.

Although ibrutinib, an inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, is generally considered to be less immunosuppressive than other therapies, it was associated with five cases of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with ibrutinib monotherapy in a 2016 report (Blood. 2016;128:1940-3). Of these five patients, four were treatment naive, suggesting that ibrutinib itself could increase risk for invasive opportunistic infections, Dr. Ghez and his colleagues noted.

Based on this finding and on case reports of invasive infections in other patients being treated with ibrutinib, the authors conducted a retrospective survey of centers in the French Innovative Leukemia Organization CLL group.

They identified 33 cases, including 30 patients with CLL (15 of whom had deleterious 17p deletions), 1 with mantle cell lymphoma, and 2 with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia.

Invasive aspergillosis accounted for 27 of the 33 cases, and 11 cases had CNS localization. There were four cases of disseminated cryptococcosis, and one each of mucormycosis and pneumocystis pneumonia.

The median time between the start of ibrutinib therapy and a diagnosis of invasive fungal infection was 3 months, with some cases occurring as early as 1 month, and others occurring 30 months out. However, the majority of cases – 28 – were diagnosed within 6 months of the start of therapy, including 20 that occurred within 3 months of ibrutinib initiation.

In 21 patients, the diagnosis of an invasive fungal infection led to drug discontinuation. In the remaining patients, the drug was either resumed after resolution of the IFI, or continued at a lower dose because of potential for interaction between ibrutinib and the antifungal agent voriconazole.

Dr. Ghez reported receiving a research grant from Janssen, and coauthor Loic Ysebaert, MD, PhD, reported consultancy fees from the company. All other authors declared no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Ghez D et al., Blood. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-818286.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) may be associated with early-onset invasive fungal infections (IFI) in patients with hematologic malignancies, investigators caution.

French investigators identified 33 cases of invasive fungal infections occurring among patients who had been treated with ibrutinib as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. Of the 33 cases, 27 were invasive aspergillosis, and 40% of these were localized in the central nervous system. The findings were published in the journal Blood.

“IFI tend to occur within the first months of treatment and are infrequent thereafter. Whilst it seems difficult at this point to advocate for systematic antifungal prophylaxis in all patients, an increased awareness about the potential risk of IFI after initiating ibrutinib is warranted, especially when other predisposing factors are associated,” wrote David Ghez, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the Gustave Roussy Institute in Villejuif and other centers in France.

Although ibrutinib, an inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, is generally considered to be less immunosuppressive than other therapies, it was associated with five cases of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with ibrutinib monotherapy in a 2016 report (Blood. 2016;128:1940-3). Of these five patients, four were treatment naive, suggesting that ibrutinib itself could increase risk for invasive opportunistic infections, Dr. Ghez and his colleagues noted.

Based on this finding and on case reports of invasive infections in other patients being treated with ibrutinib, the authors conducted a retrospective survey of centers in the French Innovative Leukemia Organization CLL group.

They identified 33 cases, including 30 patients with CLL (15 of whom had deleterious 17p deletions), 1 with mantle cell lymphoma, and 2 with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia.

Invasive aspergillosis accounted for 27 of the 33 cases, and 11 cases had CNS localization. There were four cases of disseminated cryptococcosis, and one each of mucormycosis and pneumocystis pneumonia.

The median time between the start of ibrutinib therapy and a diagnosis of invasive fungal infection was 3 months, with some cases occurring as early as 1 month, and others occurring 30 months out. However, the majority of cases – 28 – were diagnosed within 6 months of the start of therapy, including 20 that occurred within 3 months of ibrutinib initiation.

In 21 patients, the diagnosis of an invasive fungal infection led to drug discontinuation. In the remaining patients, the drug was either resumed after resolution of the IFI, or continued at a lower dose because of potential for interaction between ibrutinib and the antifungal agent voriconazole.

Dr. Ghez reported receiving a research grant from Janssen, and coauthor Loic Ysebaert, MD, PhD, reported consultancy fees from the company. All other authors declared no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Ghez D et al., Blood. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-818286.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 33 identified cases, 27 were invasive aspergillosis.

Study details: Retrospective review of case reports from 16 French centers.