User login

For MD-IQ use only

Hospital medicine, it’s time to vote

Whether physicians or advanced practice practitioners, we are the backbone of our nation’s network of acute care facilities, and on a daily basis, we see just about everything. We have valuable insight into how to improve our nation’s health care system, especially now, as our nation continues to battle COVID-19.

Our role, squarely on the front lines during this pandemic, has given us an important perspective that needs to be heard. We spend our days managing patients with complexity, coordinating with specialists and subspecialists, and advocating – at local, state, and national levels – so that our patients can more easily transition to their lives out of the hospital.

Our current polarized political climate makes it seem that individual voices will not make a difference. It is easy to feel frustrated and powerless. However, those in our specialty are actually in a perfect position to have an educated and influential say in how we move forward, not only about the immediate health crises, but also regarding future health care issues. That voice begins with voting.

Historically, physicians have had surprisingly low rates of voting. For example, a 2007 study found significantly lower rates of voting among physicians, compared with the general public.1 While physician voter turnout may have improved in the past decade, given the substantial changes in health care and the increasing amount of physician engagement in the public sphere, our participation should be greater still. Elected officials listen to, and follow up with, constituents who make their voices heard. Each of us can ensure that the health care policy priorities of our fast-growing specialty are addressed by mobilizing to the voting booth.

Candidates we elect shape our health care system for the future, directly impacting us and our patients. Cost, coverage, access to health care, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services inpatient fee schedules, the ongoing pandemic response, surprise billing, use of telehealth, observation status, and the three-midnight rule are just a few of the issues most important to hospital medicine.

Therefore, we, the SHM Public Policy Committee, urge all of our colleagues, regardless of political sway, to make your voice heard this and every election henceforth. The first step is to register to vote, if you have not done so already.2 Next, exercise that privilege. Given the pandemic, this is not as simple a process as it has been in the past. Take the time to plan your approach to early voting, mail-in voting, or election day voting. Check your County Supervisor of Elections’ website for further information, including how to register, view candidate profiles, check your precinct, and request a mail-in ballot.

In addition to casting your vote, we encourage you to share your opinions and engage in dialogue about health care issues. Clinical fact can dispel rumor and misinformation, and daily experiences can personalize our patients’ health care stories and the impact laws and rules have on our ability to practice. We are part of a trusted profession and have a unique perspective; others need and want to hear it. They can only do that if we are part of the process. Arming yourself with information and voting are the first steps on the path of advocacy. Interpersonal advocacy can also be done on social media. For example, SHM has an active grassroots advocacy network on Twitter. Tag @SHMadvocacy in your tweets to share your thoughts with their network.

Finally, as advocates for our patients in health care, we can also help ensure their safety during this election, in particular regarding COVID-19. Some patients may not wish to engage us in politics, and we must respect their decision. Others may seek our counsel and we should provide it in an unbiased fashion. We can ask our patients if they have considered a safe voting plan, help patients review the alternatives to voting in person if desired, and inform those who wish to physically cast a vote on Election Day of how to mitigate the risk of in-person voting.

Every election is important and health care is front and center for a multitude of reasons. We who practice hospital medicine are integral to our communities and need to be more politically involved. This is our chance to share our voice through our vote, not just this year, but in future elections as well.

Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, is division chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and chair of the SHM Public Policy Committee. Other members of the SHM PPC include Marta Almli, MD; John Biebelhausen, MD; Robert Burke, MD, MS, FHM; George Cheely, MD; Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM; Jennifer Cowart, MD, FHM; Suparna Dutta, MD, MS, MPH; Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM; Alain Folefack, MD; Rick Hilger MD SFHM; Melinda Johnson, MD; Sevan Karadolian, MD; Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM; Steve Phillipson, MD; Dahlia Rizk, DO; Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM; Brett Stauffer, MD, MHS; Amit Vashist, MD, SFHM; Robert Zipper, MD, SFHM.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do doctors vote? J Gen Int Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. How to register to vote, confirm or change your registration and get a voter registration card. https://www.usa.gov/voter-registration/.

Whether physicians or advanced practice practitioners, we are the backbone of our nation’s network of acute care facilities, and on a daily basis, we see just about everything. We have valuable insight into how to improve our nation’s health care system, especially now, as our nation continues to battle COVID-19.

Our role, squarely on the front lines during this pandemic, has given us an important perspective that needs to be heard. We spend our days managing patients with complexity, coordinating with specialists and subspecialists, and advocating – at local, state, and national levels – so that our patients can more easily transition to their lives out of the hospital.

Our current polarized political climate makes it seem that individual voices will not make a difference. It is easy to feel frustrated and powerless. However, those in our specialty are actually in a perfect position to have an educated and influential say in how we move forward, not only about the immediate health crises, but also regarding future health care issues. That voice begins with voting.

Historically, physicians have had surprisingly low rates of voting. For example, a 2007 study found significantly lower rates of voting among physicians, compared with the general public.1 While physician voter turnout may have improved in the past decade, given the substantial changes in health care and the increasing amount of physician engagement in the public sphere, our participation should be greater still. Elected officials listen to, and follow up with, constituents who make their voices heard. Each of us can ensure that the health care policy priorities of our fast-growing specialty are addressed by mobilizing to the voting booth.

Candidates we elect shape our health care system for the future, directly impacting us and our patients. Cost, coverage, access to health care, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services inpatient fee schedules, the ongoing pandemic response, surprise billing, use of telehealth, observation status, and the three-midnight rule are just a few of the issues most important to hospital medicine.

Therefore, we, the SHM Public Policy Committee, urge all of our colleagues, regardless of political sway, to make your voice heard this and every election henceforth. The first step is to register to vote, if you have not done so already.2 Next, exercise that privilege. Given the pandemic, this is not as simple a process as it has been in the past. Take the time to plan your approach to early voting, mail-in voting, or election day voting. Check your County Supervisor of Elections’ website for further information, including how to register, view candidate profiles, check your precinct, and request a mail-in ballot.

In addition to casting your vote, we encourage you to share your opinions and engage in dialogue about health care issues. Clinical fact can dispel rumor and misinformation, and daily experiences can personalize our patients’ health care stories and the impact laws and rules have on our ability to practice. We are part of a trusted profession and have a unique perspective; others need and want to hear it. They can only do that if we are part of the process. Arming yourself with information and voting are the first steps on the path of advocacy. Interpersonal advocacy can also be done on social media. For example, SHM has an active grassroots advocacy network on Twitter. Tag @SHMadvocacy in your tweets to share your thoughts with their network.

Finally, as advocates for our patients in health care, we can also help ensure their safety during this election, in particular regarding COVID-19. Some patients may not wish to engage us in politics, and we must respect their decision. Others may seek our counsel and we should provide it in an unbiased fashion. We can ask our patients if they have considered a safe voting plan, help patients review the alternatives to voting in person if desired, and inform those who wish to physically cast a vote on Election Day of how to mitigate the risk of in-person voting.

Every election is important and health care is front and center for a multitude of reasons. We who practice hospital medicine are integral to our communities and need to be more politically involved. This is our chance to share our voice through our vote, not just this year, but in future elections as well.

Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, is division chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and chair of the SHM Public Policy Committee. Other members of the SHM PPC include Marta Almli, MD; John Biebelhausen, MD; Robert Burke, MD, MS, FHM; George Cheely, MD; Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM; Jennifer Cowart, MD, FHM; Suparna Dutta, MD, MS, MPH; Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM; Alain Folefack, MD; Rick Hilger MD SFHM; Melinda Johnson, MD; Sevan Karadolian, MD; Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM; Steve Phillipson, MD; Dahlia Rizk, DO; Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM; Brett Stauffer, MD, MHS; Amit Vashist, MD, SFHM; Robert Zipper, MD, SFHM.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do doctors vote? J Gen Int Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. How to register to vote, confirm or change your registration and get a voter registration card. https://www.usa.gov/voter-registration/.

Whether physicians or advanced practice practitioners, we are the backbone of our nation’s network of acute care facilities, and on a daily basis, we see just about everything. We have valuable insight into how to improve our nation’s health care system, especially now, as our nation continues to battle COVID-19.

Our role, squarely on the front lines during this pandemic, has given us an important perspective that needs to be heard. We spend our days managing patients with complexity, coordinating with specialists and subspecialists, and advocating – at local, state, and national levels – so that our patients can more easily transition to their lives out of the hospital.

Our current polarized political climate makes it seem that individual voices will not make a difference. It is easy to feel frustrated and powerless. However, those in our specialty are actually in a perfect position to have an educated and influential say in how we move forward, not only about the immediate health crises, but also regarding future health care issues. That voice begins with voting.

Historically, physicians have had surprisingly low rates of voting. For example, a 2007 study found significantly lower rates of voting among physicians, compared with the general public.1 While physician voter turnout may have improved in the past decade, given the substantial changes in health care and the increasing amount of physician engagement in the public sphere, our participation should be greater still. Elected officials listen to, and follow up with, constituents who make their voices heard. Each of us can ensure that the health care policy priorities of our fast-growing specialty are addressed by mobilizing to the voting booth.

Candidates we elect shape our health care system for the future, directly impacting us and our patients. Cost, coverage, access to health care, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services inpatient fee schedules, the ongoing pandemic response, surprise billing, use of telehealth, observation status, and the three-midnight rule are just a few of the issues most important to hospital medicine.

Therefore, we, the SHM Public Policy Committee, urge all of our colleagues, regardless of political sway, to make your voice heard this and every election henceforth. The first step is to register to vote, if you have not done so already.2 Next, exercise that privilege. Given the pandemic, this is not as simple a process as it has been in the past. Take the time to plan your approach to early voting, mail-in voting, or election day voting. Check your County Supervisor of Elections’ website for further information, including how to register, view candidate profiles, check your precinct, and request a mail-in ballot.

In addition to casting your vote, we encourage you to share your opinions and engage in dialogue about health care issues. Clinical fact can dispel rumor and misinformation, and daily experiences can personalize our patients’ health care stories and the impact laws and rules have on our ability to practice. We are part of a trusted profession and have a unique perspective; others need and want to hear it. They can only do that if we are part of the process. Arming yourself with information and voting are the first steps on the path of advocacy. Interpersonal advocacy can also be done on social media. For example, SHM has an active grassroots advocacy network on Twitter. Tag @SHMadvocacy in your tweets to share your thoughts with their network.

Finally, as advocates for our patients in health care, we can also help ensure their safety during this election, in particular regarding COVID-19. Some patients may not wish to engage us in politics, and we must respect their decision. Others may seek our counsel and we should provide it in an unbiased fashion. We can ask our patients if they have considered a safe voting plan, help patients review the alternatives to voting in person if desired, and inform those who wish to physically cast a vote on Election Day of how to mitigate the risk of in-person voting.

Every election is important and health care is front and center for a multitude of reasons. We who practice hospital medicine are integral to our communities and need to be more politically involved. This is our chance to share our voice through our vote, not just this year, but in future elections as well.

Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, is division chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and chair of the SHM Public Policy Committee. Other members of the SHM PPC include Marta Almli, MD; John Biebelhausen, MD; Robert Burke, MD, MS, FHM; George Cheely, MD; Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM; Jennifer Cowart, MD, FHM; Suparna Dutta, MD, MS, MPH; Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM; Alain Folefack, MD; Rick Hilger MD SFHM; Melinda Johnson, MD; Sevan Karadolian, MD; Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM; Steve Phillipson, MD; Dahlia Rizk, DO; Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM; Brett Stauffer, MD, MHS; Amit Vashist, MD, SFHM; Robert Zipper, MD, SFHM.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do doctors vote? J Gen Int Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. How to register to vote, confirm or change your registration and get a voter registration card. https://www.usa.gov/voter-registration/.

Review finds mortality rates low in young pregnant women with SJS, TEN

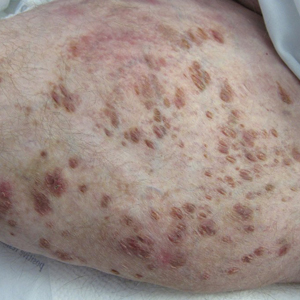

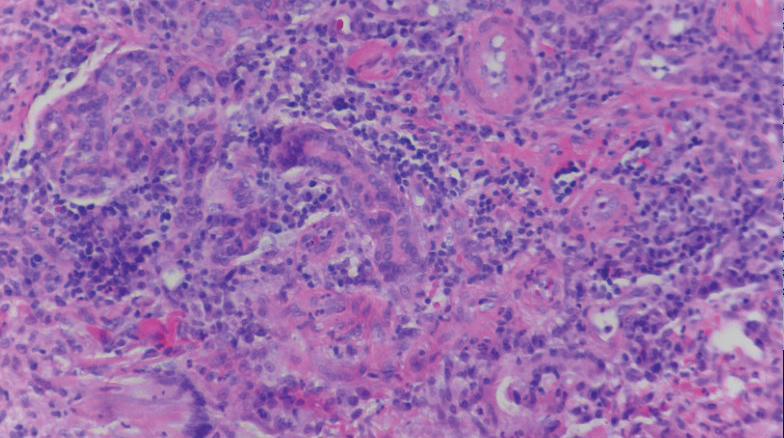

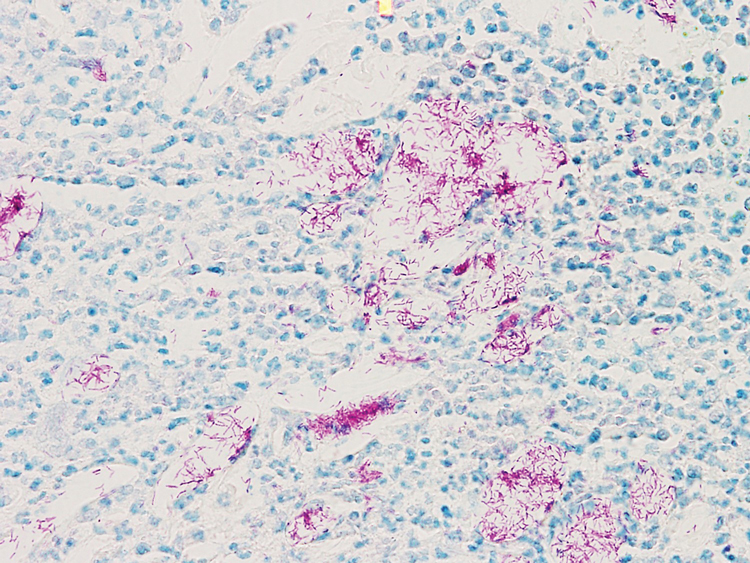

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

2020 has been quite a year

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Psychosocial resilience associated with better cardiovascular health in Blacks

Resilience might deserve targeting

Increased psychosocial resilience, which captures a sense of purpose, optimism, and life-coping strategies, correlates with improved cardiovascular (CV) health in Black Americans, according to a study that might hold a key for identifying new strategies for CV disease prevention.

“Our findings highlight the importance of individual psychosocial factors that promote cardiovascular health among Black adults, traditionally considered to be a high-risk population,” according to a team of authors collaborating on a study produced by the Morehouse-Emory Cardiovascular Center for Health Equity in Atlanta.

Studies associating psychosocial resilience with improved health outcomes have been published before. In a 12-study review of this concept, it was emphasized that resilience is a dynamic process, not a personality trait, and has shown promise as a target of efforts to relieve the burden of disease (Johnston MC et al. Psychosomatics 2015;56:168-80).

In this study, which received partial support from the American Heart Association, psychosocial resilience was evaluated at both the individual level and at the community level among 389 Black adults living in Atlanta. The senior author was Tené T. Lewis, PhD, of the department of epidemiology at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7;13:3006638).

Psychosocial resilience was calculated across the domains of environmental mastery, purpose of life, optimism, coping, and lack of depression with standardized tests, such as the Life Orientation Test-Revised questionnaire for optimism and the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being for the domains of environmental mastery and purpose of life. A composite score for psychosocial resilience was reached by calculating the median score across the measured domains.

Patients with high psychosocial resilience, defined as a composite score above the median, or low resilience, defined as a lower score, were then compared for CV health based on the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score.

LS7 scores incorporate measures for exercise, diet, smoking history, blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, and body mass index. Composite LS7 scores range from 0 to 14. Prior work cited by the authors have associated each 1-unit increase in LS7 score with a 13% lower risk of CVD.

As a continuous variable for CV risk at the individual level, each higher standard-deviation increment in the composite psychosocial resilience score was associated with a highly significant 0.42-point increase in LS7 score (P < .001) for study participants. In other words, increasing resilience predicted lower CV risk scores.

Resilience was also calculated at the community level by looking at census tract-level rates of CV mortality and morbidity relative to socioeconomic status. Again, high CV resilience, defined as scores above the median, were compared with lower scores across neighborhoods with similar median household income. As a continuous variable in this analysis, each higher standard-deviation increment in the resilience score was associated with a 0.27-point increase in LS7 score (P = .01).

After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, the association between psychosocial resilience and CV health remained significant for both the individual and community calculations, according to the authors. When examined jointly, high individual psychosocial resilience remained independently associated with improved CV health, but living in a high-resilience neighborhood was not an independent predictor.

When evaluated individually, each of the domains in the psychosocial resistance score were positively correlated with higher LS7 scores, meaning lower CV risk. The strongest associations on a statistical level were low depressive symptoms (P = .001), environmental mastery (P = .006), and purpose in life (P = .009).

The impact of high psychosocial resistance scores was greatest in Black adults living in low-resilience neighborhoods. Among these subjects, high resilience was associated with a nearly 1-point increase in LS7 score relative to low resilience (8.38 vs. 7.42). This was unexpected, but it “is consistent with some broader conceptual literature that posits that individual psychosocial resilience matters more under conditions of adversity,” the authors reported.

Understanding disparities is key

Black race has repeatedly been associated with an increased risk of CV events, but this study is valuable for providing a fresh perspective on the potential reasons, according to the authors of an accompanying editorial, Amber E. Johnson, MD, and Jared Magnani, MD, who are both affiliated with the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007357.

“Clinicians increasingly recognize that race-based disparities do not stem inherently from race; instead, the disparities stem from the underlying social determinations of health,” they wrote, citing such variables as unequal access to pay and acceptable living conditions “and the structural racism that perpetuates them.”

They agreed with the authors that promotion of psychosocial resilience among Black people living in communities with poor CV health has the potential to improve CV outcomes, but they warned that this is complex. Although they contend that resilience techniques can be taught, they cautioned there might be limitations if the underlying factors associated with poor psychosocial resilience remain unchanged.

“Thus, the superficial application of positive psychology strategies is likely insufficient to bring parity to CV health outcomes,” they wrote, concluding that strategies to promote health equity would negate the need for interventions to bolster resilience.

Studies that focus on Black adults and cardiovascular health, including this investigation into the role of psychosocial factors “are much needed and very welcome,” said Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, a cardiologist and professor in the Institute for Social and Policy Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He sees a broad array of potential directions of research.

“The study opens many questions about whether the resilience can be strengthened by interventions; whether addressing structural racism could reduce the need for such resilience, and whether this association is specific to Black adults in an urban center or is generally present in other settings and in other populations,” Dr. Krumholz said.

An effort is now needed to determine “whether this is a marker or a mediator of cardiovascular health,” he added.

In either case, resilience is a potentially important factor for understanding racial disparities in CV-disease prevalence and outcomes, according to the authors of the accompanying editorial and Dr. Krumholz.

SOURCE: Kim JH et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Oct 7;13:e006638.

Resilience might deserve targeting

Resilience might deserve targeting

Increased psychosocial resilience, which captures a sense of purpose, optimism, and life-coping strategies, correlates with improved cardiovascular (CV) health in Black Americans, according to a study that might hold a key for identifying new strategies for CV disease prevention.

“Our findings highlight the importance of individual psychosocial factors that promote cardiovascular health among Black adults, traditionally considered to be a high-risk population,” according to a team of authors collaborating on a study produced by the Morehouse-Emory Cardiovascular Center for Health Equity in Atlanta.

Studies associating psychosocial resilience with improved health outcomes have been published before. In a 12-study review of this concept, it was emphasized that resilience is a dynamic process, not a personality trait, and has shown promise as a target of efforts to relieve the burden of disease (Johnston MC et al. Psychosomatics 2015;56:168-80).

In this study, which received partial support from the American Heart Association, psychosocial resilience was evaluated at both the individual level and at the community level among 389 Black adults living in Atlanta. The senior author was Tené T. Lewis, PhD, of the department of epidemiology at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7;13:3006638).

Psychosocial resilience was calculated across the domains of environmental mastery, purpose of life, optimism, coping, and lack of depression with standardized tests, such as the Life Orientation Test-Revised questionnaire for optimism and the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being for the domains of environmental mastery and purpose of life. A composite score for psychosocial resilience was reached by calculating the median score across the measured domains.

Patients with high psychosocial resilience, defined as a composite score above the median, or low resilience, defined as a lower score, were then compared for CV health based on the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score.

LS7 scores incorporate measures for exercise, diet, smoking history, blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, and body mass index. Composite LS7 scores range from 0 to 14. Prior work cited by the authors have associated each 1-unit increase in LS7 score with a 13% lower risk of CVD.

As a continuous variable for CV risk at the individual level, each higher standard-deviation increment in the composite psychosocial resilience score was associated with a highly significant 0.42-point increase in LS7 score (P < .001) for study participants. In other words, increasing resilience predicted lower CV risk scores.

Resilience was also calculated at the community level by looking at census tract-level rates of CV mortality and morbidity relative to socioeconomic status. Again, high CV resilience, defined as scores above the median, were compared with lower scores across neighborhoods with similar median household income. As a continuous variable in this analysis, each higher standard-deviation increment in the resilience score was associated with a 0.27-point increase in LS7 score (P = .01).

After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, the association between psychosocial resilience and CV health remained significant for both the individual and community calculations, according to the authors. When examined jointly, high individual psychosocial resilience remained independently associated with improved CV health, but living in a high-resilience neighborhood was not an independent predictor.

When evaluated individually, each of the domains in the psychosocial resistance score were positively correlated with higher LS7 scores, meaning lower CV risk. The strongest associations on a statistical level were low depressive symptoms (P = .001), environmental mastery (P = .006), and purpose in life (P = .009).

The impact of high psychosocial resistance scores was greatest in Black adults living in low-resilience neighborhoods. Among these subjects, high resilience was associated with a nearly 1-point increase in LS7 score relative to low resilience (8.38 vs. 7.42). This was unexpected, but it “is consistent with some broader conceptual literature that posits that individual psychosocial resilience matters more under conditions of adversity,” the authors reported.

Understanding disparities is key

Black race has repeatedly been associated with an increased risk of CV events, but this study is valuable for providing a fresh perspective on the potential reasons, according to the authors of an accompanying editorial, Amber E. Johnson, MD, and Jared Magnani, MD, who are both affiliated with the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007357.

“Clinicians increasingly recognize that race-based disparities do not stem inherently from race; instead, the disparities stem from the underlying social determinations of health,” they wrote, citing such variables as unequal access to pay and acceptable living conditions “and the structural racism that perpetuates them.”

They agreed with the authors that promotion of psychosocial resilience among Black people living in communities with poor CV health has the potential to improve CV outcomes, but they warned that this is complex. Although they contend that resilience techniques can be taught, they cautioned there might be limitations if the underlying factors associated with poor psychosocial resilience remain unchanged.

“Thus, the superficial application of positive psychology strategies is likely insufficient to bring parity to CV health outcomes,” they wrote, concluding that strategies to promote health equity would negate the need for interventions to bolster resilience.

Studies that focus on Black adults and cardiovascular health, including this investigation into the role of psychosocial factors “are much needed and very welcome,” said Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, a cardiologist and professor in the Institute for Social and Policy Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He sees a broad array of potential directions of research.

“The study opens many questions about whether the resilience can be strengthened by interventions; whether addressing structural racism could reduce the need for such resilience, and whether this association is specific to Black adults in an urban center or is generally present in other settings and in other populations,” Dr. Krumholz said.

An effort is now needed to determine “whether this is a marker or a mediator of cardiovascular health,” he added.

In either case, resilience is a potentially important factor for understanding racial disparities in CV-disease prevalence and outcomes, according to the authors of the accompanying editorial and Dr. Krumholz.

SOURCE: Kim JH et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Oct 7;13:e006638.

Increased psychosocial resilience, which captures a sense of purpose, optimism, and life-coping strategies, correlates with improved cardiovascular (CV) health in Black Americans, according to a study that might hold a key for identifying new strategies for CV disease prevention.

“Our findings highlight the importance of individual psychosocial factors that promote cardiovascular health among Black adults, traditionally considered to be a high-risk population,” according to a team of authors collaborating on a study produced by the Morehouse-Emory Cardiovascular Center for Health Equity in Atlanta.

Studies associating psychosocial resilience with improved health outcomes have been published before. In a 12-study review of this concept, it was emphasized that resilience is a dynamic process, not a personality trait, and has shown promise as a target of efforts to relieve the burden of disease (Johnston MC et al. Psychosomatics 2015;56:168-80).

In this study, which received partial support from the American Heart Association, psychosocial resilience was evaluated at both the individual level and at the community level among 389 Black adults living in Atlanta. The senior author was Tené T. Lewis, PhD, of the department of epidemiology at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7;13:3006638).

Psychosocial resilience was calculated across the domains of environmental mastery, purpose of life, optimism, coping, and lack of depression with standardized tests, such as the Life Orientation Test-Revised questionnaire for optimism and the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being for the domains of environmental mastery and purpose of life. A composite score for psychosocial resilience was reached by calculating the median score across the measured domains.

Patients with high psychosocial resilience, defined as a composite score above the median, or low resilience, defined as a lower score, were then compared for CV health based on the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score.

LS7 scores incorporate measures for exercise, diet, smoking history, blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, and body mass index. Composite LS7 scores range from 0 to 14. Prior work cited by the authors have associated each 1-unit increase in LS7 score with a 13% lower risk of CVD.

As a continuous variable for CV risk at the individual level, each higher standard-deviation increment in the composite psychosocial resilience score was associated with a highly significant 0.42-point increase in LS7 score (P < .001) for study participants. In other words, increasing resilience predicted lower CV risk scores.

Resilience was also calculated at the community level by looking at census tract-level rates of CV mortality and morbidity relative to socioeconomic status. Again, high CV resilience, defined as scores above the median, were compared with lower scores across neighborhoods with similar median household income. As a continuous variable in this analysis, each higher standard-deviation increment in the resilience score was associated with a 0.27-point increase in LS7 score (P = .01).

After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, the association between psychosocial resilience and CV health remained significant for both the individual and community calculations, according to the authors. When examined jointly, high individual psychosocial resilience remained independently associated with improved CV health, but living in a high-resilience neighborhood was not an independent predictor.

When evaluated individually, each of the domains in the psychosocial resistance score were positively correlated with higher LS7 scores, meaning lower CV risk. The strongest associations on a statistical level were low depressive symptoms (P = .001), environmental mastery (P = .006), and purpose in life (P = .009).

The impact of high psychosocial resistance scores was greatest in Black adults living in low-resilience neighborhoods. Among these subjects, high resilience was associated with a nearly 1-point increase in LS7 score relative to low resilience (8.38 vs. 7.42). This was unexpected, but it “is consistent with some broader conceptual literature that posits that individual psychosocial resilience matters more under conditions of adversity,” the authors reported.

Understanding disparities is key

Black race has repeatedly been associated with an increased risk of CV events, but this study is valuable for providing a fresh perspective on the potential reasons, according to the authors of an accompanying editorial, Amber E. Johnson, MD, and Jared Magnani, MD, who are both affiliated with the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020 Oct 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007357.

“Clinicians increasingly recognize that race-based disparities do not stem inherently from race; instead, the disparities stem from the underlying social determinations of health,” they wrote, citing such variables as unequal access to pay and acceptable living conditions “and the structural racism that perpetuates them.”

They agreed with the authors that promotion of psychosocial resilience among Black people living in communities with poor CV health has the potential to improve CV outcomes, but they warned that this is complex. Although they contend that resilience techniques can be taught, they cautioned there might be limitations if the underlying factors associated with poor psychosocial resilience remain unchanged.

“Thus, the superficial application of positive psychology strategies is likely insufficient to bring parity to CV health outcomes,” they wrote, concluding that strategies to promote health equity would negate the need for interventions to bolster resilience.

Studies that focus on Black adults and cardiovascular health, including this investigation into the role of psychosocial factors “are much needed and very welcome,” said Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, a cardiologist and professor in the Institute for Social and Policy Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He sees a broad array of potential directions of research.

“The study opens many questions about whether the resilience can be strengthened by interventions; whether addressing structural racism could reduce the need for such resilience, and whether this association is specific to Black adults in an urban center or is generally present in other settings and in other populations,” Dr. Krumholz said.

An effort is now needed to determine “whether this is a marker or a mediator of cardiovascular health,” he added.

In either case, resilience is a potentially important factor for understanding racial disparities in CV-disease prevalence and outcomes, according to the authors of the accompanying editorial and Dr. Krumholz.

SOURCE: Kim JH et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Oct 7;13:e006638.

FROM CIRCULATION: CARDIOVASCULAR QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

The ally in the waiting room

Improving communication with patients’ loved ones

We think of a patient’s recovery happening in multiple locations – in a hospital room or a rehabilitation facility, for example. But many clinicians may not consider the opportunity to aid healing that lies in the waiting room.

The waiting room is where a patient’s loved ones often are and they, sometimes more than anyone, can unlock the path to a patient’s quicker recovery. Friends and family can offer encouragement, as they have an existing bond of trust that can help if a patient needs reinforcement to take their medications or follow other health care advice. But if loved ones are going to help patients, they need help from clinicians. Beyond being potential allies, they are also hurting, experiencing worry or confusion in a world of medical jargon.

The coronavirus changes the relationship of patients and their loved ones, as patients are often isolated or limited in the number of visitors they are allowed to see. A smartphone replaces the smiling faces of friends and relatives at their bedside, and a text is a poor substitute for a hug.

The Hospitalist asked some experienced hospitalists for insight on how best to communicate with patients’ loved ones to improve outcomes for all, medically and emotionally.

Team approach

“Patients feel isolated, terrified, and vulnerable but still need an advocate in the hospital, so daily communication with a patient’s loved one is important to give a sense that the patient is looked after,” said Kari Esbensen, MD, PhD, a hospitalist and palliative care expert at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta.

Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and director, quality and safety programs, at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, agreed. He said that the most important thing is to communicate, period.

“We fall into this pattern of ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ ” he said. “We need to take the extra step to find out who a patient’s loved ones are. If it is a clinical visit, ask the patient, or maybe get the information from a caseworker, or just pay attention to who is dropping in to see the patient. Having a second person available to jot down notes, or having a handy list of questions – it all helps the patient. We forget that sometimes it can seem like a whirlwind for the patient when they are hurting. We have to remember that a loved one is important to a patient’s care team and we need to include them, empower them, and show that we want to hear their voices.”

Dr. Esbensen said it is critical to start off on the right foot when communicating with a patient’s loved one, especially during the current pandemic.

“With COVID-19, the most important thing is to speak honestly, to say hope for the best but prepare for the worst-case scenario,” Dr. Esbensen said. “We’ve seen that conditions can shift dramatically in short periods of time. The loved one needs to have a sense of the positive and negative possibilities. Families tend to lack understanding of the changes in the patient that are caused by COVID-19. The patient can come out of the hospital debilitated, very different than when they entered the hospital, and we need to warn people close to them about this. Unrealistic expectations need to be guarded against if a patient’s loved ones are going to help.”

Perhaps the best form of communication with a patient’s loved ones is an often-forgotten skill: listening.

“Get an idea from the patient’s loved ones of what the issues are, as well as their idea of what they think of the disease and how it spreads,” Dr. Esbensen said. “Sometimes they are right on target but sometimes there are misinterpretations and we need to help them understand it better. It’s not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ speech that we should give, but try to say, ‘tell me what you think is going on, what you think you’ve heard, and what you’re worried about,’ and learn what is most important to the patient. Start on those terms and adapt; this way you can correct and address what makes them most fearful, which can be different for each loved one. For some, the concern could be that they have children or other vulnerable people in the house. Finding out these other issues is important.”

Venkatrao Medarametla, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., emphasized that, in a time when hospitalists are being pulled in every direction, it is easy to lose your attention.

“It’s very important that family members know you’re present with them,” he said. “This can be an emotional time and they need empathy. It’s very easy for our list of tasks to get in the way of communicating, including with our body language.”

Dr. Medarametla said one of the reasons to communicate with patients’ loved ones is to calm them – a patient’s relatives or their friends may not be under your medical care, but they are still human beings.

“A lot of people just want information and want to be helpful, but we also need to realize that, while we are caring for many patients, this one person is the patient they are focused on,” said Laura Nell Hodo, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Kravis Children’s Hospital at Mount Sinai in New York. “Don’t rush, and if you know that a patient’s loved one needs more time, make sure it can be found – if not then, at least later on the phone. Fifteen to 20 minutes may be what’s needed, and you can’t shortchange them.”

Dr. Hodo said that a patient’s loved ones often do not realize it is possible to receive phone calls from hospitalists. “We need to remind them that they can get in touch with us. We have to remember how helpless they can feel and how they want to understand what is happening in the hospital.”

For medical adherence issues, sometimes it is best to communicate with the patient and loved one at the same time, Dr. Hodo advised. “Whether it’s for medication or postdischarge exercises, if they both receive the information together it can reinforce adherence. But you also need to remember that the patient may only want a loved one told about certain things, or possibly nothing at all. We need to make sure we understand the patient’s wishes, regardless of whether we think a person close to them can be an ally or not.”

Dr. Esbensen also noted that a loved one can give hospitalists important clues to the emotional components of a patient’s care.

“I remember a patient whose wife told me how he worked in a garage, how he was strong and did not want people to think he was a weak guy just because of what was happening to him,” Dr. Esbensen said. “I didn’t know that he felt he might be perceived in this way. I mentioned to him how I learned he was a good mechanic and he perked up and felt seen in a different light. These things make a difference.”

But when is the best time to speak with a patient’s loved ones? Since much communication is done via phone during the pandemic, there are different philosophies.

“We had a debate among colleagues to see how each of us did it,” Dr. Esbensen said. “Some try to call after each patient encounter, while they are outside the room and it’s fresh in their mind, but others find it better to make the call after their rounds, to give the person their full attention. Most of the time I try to do it that way.”

She noted that, in the current environment, a phone call may be better than a face-to-face conversation with patients’ loved ones.

“We’re covered in so much gear to protect us from the coronavirus that it can feel like a great distance exists between us and the person with whom we’re speaking,” she said. “It’s strange, but the phone can make the conversation seem more relaxed and may get people to open up more.”

Even when they leave

All the hospitalists affirmed that loved ones can make a big difference for the patient through all aspects of care. Long after a patient returns home, the support of loved ones can have a profound impact in speeding healing and improving long-term outcomes.

Dr. Esbensen said COVID-19 and other serious illnesses can leave a patient needing support, and maybe a “push” when feeling low keeps them from adhering to medical advice.

“It’s not just in the hospital but after discharge,” she said. “A person offering support can really help patients throughout their journey, and much success in recovering from illness occurs after the transition home. Having the support of that one person a patient trusts can be critical.”

Dr. Hodo believes that the coronavirus pandemic could forever change the way hospitalists communicate with patients and their loved ones.

“I work in pediatrics and we know serious medical decisions can’t be made without guardians or parents,” she said. “But in adult medicine doctors may not automatically ask the patient about calling someone for input on decision-making. With COVID, you cannot assume a patient is on their own, because there are protocols keeping people from physically being present in the patient’s room. My experience from working in adult coronavirus units is that the thinking about the loved ones’ role in patient care – and communication with them – might just change. … At least, I hope so.”

Quick takeaways for hospitalists

- Get beyond personal protective equipment. A conversation with a patient’s loved one might be easier to achieve via phone, without all the protective gear in the way.

- Encourage adherence. Speaking with patients and loved ones together may be more effective. They may reach agreement quicker on how best to adhere to medical advice.

- Loved ones offer clues. They might give you a better sense of a patient’s worries, or help you to connect better with those in your care.

- Be present. You have a long to-do list but do not let empathy fall off it, even if you feel overwhelmed.

Improving communication with patients’ loved ones

Improving communication with patients’ loved ones

We think of a patient’s recovery happening in multiple locations – in a hospital room or a rehabilitation facility, for example. But many clinicians may not consider the opportunity to aid healing that lies in the waiting room.

The waiting room is where a patient’s loved ones often are and they, sometimes more than anyone, can unlock the path to a patient’s quicker recovery. Friends and family can offer encouragement, as they have an existing bond of trust that can help if a patient needs reinforcement to take their medications or follow other health care advice. But if loved ones are going to help patients, they need help from clinicians. Beyond being potential allies, they are also hurting, experiencing worry or confusion in a world of medical jargon.

The coronavirus changes the relationship of patients and their loved ones, as patients are often isolated or limited in the number of visitors they are allowed to see. A smartphone replaces the smiling faces of friends and relatives at their bedside, and a text is a poor substitute for a hug.

The Hospitalist asked some experienced hospitalists for insight on how best to communicate with patients’ loved ones to improve outcomes for all, medically and emotionally.

Team approach

“Patients feel isolated, terrified, and vulnerable but still need an advocate in the hospital, so daily communication with a patient’s loved one is important to give a sense that the patient is looked after,” said Kari Esbensen, MD, PhD, a hospitalist and palliative care expert at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta.

Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and director, quality and safety programs, at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, agreed. He said that the most important thing is to communicate, period.

“We fall into this pattern of ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ ” he said. “We need to take the extra step to find out who a patient’s loved ones are. If it is a clinical visit, ask the patient, or maybe get the information from a caseworker, or just pay attention to who is dropping in to see the patient. Having a second person available to jot down notes, or having a handy list of questions – it all helps the patient. We forget that sometimes it can seem like a whirlwind for the patient when they are hurting. We have to remember that a loved one is important to a patient’s care team and we need to include them, empower them, and show that we want to hear their voices.”

Dr. Esbensen said it is critical to start off on the right foot when communicating with a patient’s loved one, especially during the current pandemic.

“With COVID-19, the most important thing is to speak honestly, to say hope for the best but prepare for the worst-case scenario,” Dr. Esbensen said. “We’ve seen that conditions can shift dramatically in short periods of time. The loved one needs to have a sense of the positive and negative possibilities. Families tend to lack understanding of the changes in the patient that are caused by COVID-19. The patient can come out of the hospital debilitated, very different than when they entered the hospital, and we need to warn people close to them about this. Unrealistic expectations need to be guarded against if a patient’s loved ones are going to help.”

Perhaps the best form of communication with a patient’s loved ones is an often-forgotten skill: listening.

“Get an idea from the patient’s loved ones of what the issues are, as well as their idea of what they think of the disease and how it spreads,” Dr. Esbensen said. “Sometimes they are right on target but sometimes there are misinterpretations and we need to help them understand it better. It’s not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ speech that we should give, but try to say, ‘tell me what you think is going on, what you think you’ve heard, and what you’re worried about,’ and learn what is most important to the patient. Start on those terms and adapt; this way you can correct and address what makes them most fearful, which can be different for each loved one. For some, the concern could be that they have children or other vulnerable people in the house. Finding out these other issues is important.”

Venkatrao Medarametla, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., emphasized that, in a time when hospitalists are being pulled in every direction, it is easy to lose your attention.

“It’s very important that family members know you’re present with them,” he said. “This can be an emotional time and they need empathy. It’s very easy for our list of tasks to get in the way of communicating, including with our body language.”

Dr. Medarametla said one of the reasons to communicate with patients’ loved ones is to calm them – a patient’s relatives or their friends may not be under your medical care, but they are still human beings.

“A lot of people just want information and want to be helpful, but we also need to realize that, while we are caring for many patients, this one person is the patient they are focused on,” said Laura Nell Hodo, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Kravis Children’s Hospital at Mount Sinai in New York. “Don’t rush, and if you know that a patient’s loved one needs more time, make sure it can be found – if not then, at least later on the phone. Fifteen to 20 minutes may be what’s needed, and you can’t shortchange them.”

Dr. Hodo said that a patient’s loved ones often do not realize it is possible to receive phone calls from hospitalists. “We need to remind them that they can get in touch with us. We have to remember how helpless they can feel and how they want to understand what is happening in the hospital.”

For medical adherence issues, sometimes it is best to communicate with the patient and loved one at the same time, Dr. Hodo advised. “Whether it’s for medication or postdischarge exercises, if they both receive the information together it can reinforce adherence. But you also need to remember that the patient may only want a loved one told about certain things, or possibly nothing at all. We need to make sure we understand the patient’s wishes, regardless of whether we think a person close to them can be an ally or not.”

Dr. Esbensen also noted that a loved one can give hospitalists important clues to the emotional components of a patient’s care.

“I remember a patient whose wife told me how he worked in a garage, how he was strong and did not want people to think he was a weak guy just because of what was happening to him,” Dr. Esbensen said. “I didn’t know that he felt he might be perceived in this way. I mentioned to him how I learned he was a good mechanic and he perked up and felt seen in a different light. These things make a difference.”

But when is the best time to speak with a patient’s loved ones? Since much communication is done via phone during the pandemic, there are different philosophies.

“We had a debate among colleagues to see how each of us did it,” Dr. Esbensen said. “Some try to call after each patient encounter, while they are outside the room and it’s fresh in their mind, but others find it better to make the call after their rounds, to give the person their full attention. Most of the time I try to do it that way.”

She noted that, in the current environment, a phone call may be better than a face-to-face conversation with patients’ loved ones.

“We’re covered in so much gear to protect us from the coronavirus that it can feel like a great distance exists between us and the person with whom we’re speaking,” she said. “It’s strange, but the phone can make the conversation seem more relaxed and may get people to open up more.”

Even when they leave

All the hospitalists affirmed that loved ones can make a big difference for the patient through all aspects of care. Long after a patient returns home, the support of loved ones can have a profound impact in speeding healing and improving long-term outcomes.

Dr. Esbensen said COVID-19 and other serious illnesses can leave a patient needing support, and maybe a “push” when feeling low keeps them from adhering to medical advice.

“It’s not just in the hospital but after discharge,” she said. “A person offering support can really help patients throughout their journey, and much success in recovering from illness occurs after the transition home. Having the support of that one person a patient trusts can be critical.”

Dr. Hodo believes that the coronavirus pandemic could forever change the way hospitalists communicate with patients and their loved ones.