User login

For MD-IQ use only

Fellowship procedure logs: A word of advice for fellows and a call to action for fellowship programs

As a GI fellow, I never would have imagined I would be writing an article on GI fellowship procedure logs. At the time, in my naiveté, I looked at the procedure log as a necessary evil and part of the “red tape” imposed on fellowship programs by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). While the importance of keeping a log was highlighted and enforced by my program, the large majority of the recommended numbers were easily achievable. As a result, even my sporadic tracking of completed procedures was sufficient to meet the requirements. My poor compliance wasn’t because I was lazy or careless, but rather because of the absence of a formal system, which resulted in homegrown methods that were highly inaccurate. I wasn’t alone in my follies. As I discussed this issue with fellows across the nation, I learned that these sentiments were universally shared. It seemed that everyone had come up with their own unique way of keeping a log – from Word and Excel documents, to a binder of patient stickers, to a daily folded sheet of paper with scribbled technical notes – all of which were an inconvenience to trainees already stretched thin. However, when the time came for employee credentialing, I came to realize the importance of keeping an accurate record. This once-neglected document would become the ultimate record of my capabilities for independent practice. The pitfalls and shortcomings of how we currently log procedures is why it was the first thing I worked on improving once I was an academic faculty member. There had to be a better way!

I started by reviewing what ACGME actually mandates trainees in GI to track, and to my surprise, they no longer set minimum procedure requirements, but rather competencies. The current requirements state that “Fellows must demonstrate competence in performance of ... procedures”1 and specifically state that competence should “not be based solely on a minimum number of procedures performed.” So, where does the need for a procedure log and minimum numbers come from? Your fellowship programs’ review committee. Programs recognize that, in order to approve requests for independent practice privileges, they need to substantiate the competency of the fellow, which ultimately is best evidenced through procedure logs. Therefore, the committee sets the minimum number of cases they believe is necessary for trainees to practice safely and independently.2 Our program leadership at UConn Health in Farmington, Conn., annually assesses our procedure activity and, over the years, has settled on the procedure guideline numbers provided to fellows at orientation and reviewed with them semiannually.

Once I understood exactly why we need procedure logs, I started looking at how other specialties handle them, particularly surgical programs in which accurate procedure logs are vitally important. It turns out that they universally use, and look favorably on, the ACGME Case Log System - an online, all encompassing, tracking software. This system is provided to surgical programs despite ACGME’s focus on competencies rather than numbers. Why this system is not offered for GI programs is unclear. However, in my endeavor, I was able to find the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Procedure Log system. When we reviewed the system in 2015 for use in our program, it was more of a concept than an all-encompassing tool. Fortunately, the AGA Information Technology (IT) and Training departments were kind enough to work with us to develop a complete online tracking tool that could be used nationally by all trainees in GI. Finally, we had a system to keep an accurate, secure log online and in real time.

A plea to fellows

With this, understand that in today’s document driven and litigious world, your procedure log is as vital to endoscopy as the scope itself. Without it, you may not be granted permission to do x, y, or z procedure. Indirectly, it can lead to delays in patient care and may prevent you from performing certain tasks and ultimately lead to repetitive training. Treat it as an official legal document of what you’ve done and what you are capable of doing. Recognize that it will be used by your mentors as supporting evidence regarding your competency for independent practice. Ask your training program to provide a clear list of expectations and requirements for graduation and a method for you to accurately track them, such as the AGA Procedure Log. An online, mobile system will allow you to document cases immediately after you finish while the procedure is fresh in your mind. Taking an extra minute after each case will prevent headaches down the road. The faculty and your cofellows all know of the end of the year “procedure scavenger” (i.e., the fellow who searches for procedures and takes them from others to make sure they meet their numbers for graduation). Please don’t be that person.

A request for program directors

As GI educators, we all know the mention of procedure logs to fellows is typically accompanied by eye rolls. It doesn’t have to be that way. Provide your fellows with clear expectations and a quick, easy, and accurate way to track their accomplishments. Help them recognize the importance of an accurate and complete procedure log. Consider an online tracking system such as the AGA Procedure Log. Studies have demonstrated that a computer-based system increases compliance and accuracy.3 Not providing one will surely lead to difficulties in the long run and is a disservice to those we work to empower, educate, and prepare for success.

References

1. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Gastroenterology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2020 Jul 1. pp 21, 28. Accessed Sept. 13, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/144_Gastroenterology_2020.pdf.

2. Steven J et al. J Grad Med Educat. 2012;4(2):257-60.

3. Rowe BH et al. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:2113–20.

Dr. Rezaizadeh is an assistant professor of medicine, associate program director, gastroenterology fellowship program, UConn Health, Farmington, Conn.

As a GI fellow, I never would have imagined I would be writing an article on GI fellowship procedure logs. At the time, in my naiveté, I looked at the procedure log as a necessary evil and part of the “red tape” imposed on fellowship programs by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). While the importance of keeping a log was highlighted and enforced by my program, the large majority of the recommended numbers were easily achievable. As a result, even my sporadic tracking of completed procedures was sufficient to meet the requirements. My poor compliance wasn’t because I was lazy or careless, but rather because of the absence of a formal system, which resulted in homegrown methods that were highly inaccurate. I wasn’t alone in my follies. As I discussed this issue with fellows across the nation, I learned that these sentiments were universally shared. It seemed that everyone had come up with their own unique way of keeping a log – from Word and Excel documents, to a binder of patient stickers, to a daily folded sheet of paper with scribbled technical notes – all of which were an inconvenience to trainees already stretched thin. However, when the time came for employee credentialing, I came to realize the importance of keeping an accurate record. This once-neglected document would become the ultimate record of my capabilities for independent practice. The pitfalls and shortcomings of how we currently log procedures is why it was the first thing I worked on improving once I was an academic faculty member. There had to be a better way!

I started by reviewing what ACGME actually mandates trainees in GI to track, and to my surprise, they no longer set minimum procedure requirements, but rather competencies. The current requirements state that “Fellows must demonstrate competence in performance of ... procedures”1 and specifically state that competence should “not be based solely on a minimum number of procedures performed.” So, where does the need for a procedure log and minimum numbers come from? Your fellowship programs’ review committee. Programs recognize that, in order to approve requests for independent practice privileges, they need to substantiate the competency of the fellow, which ultimately is best evidenced through procedure logs. Therefore, the committee sets the minimum number of cases they believe is necessary for trainees to practice safely and independently.2 Our program leadership at UConn Health in Farmington, Conn., annually assesses our procedure activity and, over the years, has settled on the procedure guideline numbers provided to fellows at orientation and reviewed with them semiannually.

Once I understood exactly why we need procedure logs, I started looking at how other specialties handle them, particularly surgical programs in which accurate procedure logs are vitally important. It turns out that they universally use, and look favorably on, the ACGME Case Log System - an online, all encompassing, tracking software. This system is provided to surgical programs despite ACGME’s focus on competencies rather than numbers. Why this system is not offered for GI programs is unclear. However, in my endeavor, I was able to find the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Procedure Log system. When we reviewed the system in 2015 for use in our program, it was more of a concept than an all-encompassing tool. Fortunately, the AGA Information Technology (IT) and Training departments were kind enough to work with us to develop a complete online tracking tool that could be used nationally by all trainees in GI. Finally, we had a system to keep an accurate, secure log online and in real time.

A plea to fellows

With this, understand that in today’s document driven and litigious world, your procedure log is as vital to endoscopy as the scope itself. Without it, you may not be granted permission to do x, y, or z procedure. Indirectly, it can lead to delays in patient care and may prevent you from performing certain tasks and ultimately lead to repetitive training. Treat it as an official legal document of what you’ve done and what you are capable of doing. Recognize that it will be used by your mentors as supporting evidence regarding your competency for independent practice. Ask your training program to provide a clear list of expectations and requirements for graduation and a method for you to accurately track them, such as the AGA Procedure Log. An online, mobile system will allow you to document cases immediately after you finish while the procedure is fresh in your mind. Taking an extra minute after each case will prevent headaches down the road. The faculty and your cofellows all know of the end of the year “procedure scavenger” (i.e., the fellow who searches for procedures and takes them from others to make sure they meet their numbers for graduation). Please don’t be that person.

A request for program directors

As GI educators, we all know the mention of procedure logs to fellows is typically accompanied by eye rolls. It doesn’t have to be that way. Provide your fellows with clear expectations and a quick, easy, and accurate way to track their accomplishments. Help them recognize the importance of an accurate and complete procedure log. Consider an online tracking system such as the AGA Procedure Log. Studies have demonstrated that a computer-based system increases compliance and accuracy.3 Not providing one will surely lead to difficulties in the long run and is a disservice to those we work to empower, educate, and prepare for success.

References

1. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Gastroenterology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2020 Jul 1. pp 21, 28. Accessed Sept. 13, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/144_Gastroenterology_2020.pdf.

2. Steven J et al. J Grad Med Educat. 2012;4(2):257-60.

3. Rowe BH et al. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:2113–20.

Dr. Rezaizadeh is an assistant professor of medicine, associate program director, gastroenterology fellowship program, UConn Health, Farmington, Conn.

As a GI fellow, I never would have imagined I would be writing an article on GI fellowship procedure logs. At the time, in my naiveté, I looked at the procedure log as a necessary evil and part of the “red tape” imposed on fellowship programs by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). While the importance of keeping a log was highlighted and enforced by my program, the large majority of the recommended numbers were easily achievable. As a result, even my sporadic tracking of completed procedures was sufficient to meet the requirements. My poor compliance wasn’t because I was lazy or careless, but rather because of the absence of a formal system, which resulted in homegrown methods that were highly inaccurate. I wasn’t alone in my follies. As I discussed this issue with fellows across the nation, I learned that these sentiments were universally shared. It seemed that everyone had come up with their own unique way of keeping a log – from Word and Excel documents, to a binder of patient stickers, to a daily folded sheet of paper with scribbled technical notes – all of which were an inconvenience to trainees already stretched thin. However, when the time came for employee credentialing, I came to realize the importance of keeping an accurate record. This once-neglected document would become the ultimate record of my capabilities for independent practice. The pitfalls and shortcomings of how we currently log procedures is why it was the first thing I worked on improving once I was an academic faculty member. There had to be a better way!

I started by reviewing what ACGME actually mandates trainees in GI to track, and to my surprise, they no longer set minimum procedure requirements, but rather competencies. The current requirements state that “Fellows must demonstrate competence in performance of ... procedures”1 and specifically state that competence should “not be based solely on a minimum number of procedures performed.” So, where does the need for a procedure log and minimum numbers come from? Your fellowship programs’ review committee. Programs recognize that, in order to approve requests for independent practice privileges, they need to substantiate the competency of the fellow, which ultimately is best evidenced through procedure logs. Therefore, the committee sets the minimum number of cases they believe is necessary for trainees to practice safely and independently.2 Our program leadership at UConn Health in Farmington, Conn., annually assesses our procedure activity and, over the years, has settled on the procedure guideline numbers provided to fellows at orientation and reviewed with them semiannually.

Once I understood exactly why we need procedure logs, I started looking at how other specialties handle them, particularly surgical programs in which accurate procedure logs are vitally important. It turns out that they universally use, and look favorably on, the ACGME Case Log System - an online, all encompassing, tracking software. This system is provided to surgical programs despite ACGME’s focus on competencies rather than numbers. Why this system is not offered for GI programs is unclear. However, in my endeavor, I was able to find the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Procedure Log system. When we reviewed the system in 2015 for use in our program, it was more of a concept than an all-encompassing tool. Fortunately, the AGA Information Technology (IT) and Training departments were kind enough to work with us to develop a complete online tracking tool that could be used nationally by all trainees in GI. Finally, we had a system to keep an accurate, secure log online and in real time.

A plea to fellows

With this, understand that in today’s document driven and litigious world, your procedure log is as vital to endoscopy as the scope itself. Without it, you may not be granted permission to do x, y, or z procedure. Indirectly, it can lead to delays in patient care and may prevent you from performing certain tasks and ultimately lead to repetitive training. Treat it as an official legal document of what you’ve done and what you are capable of doing. Recognize that it will be used by your mentors as supporting evidence regarding your competency for independent practice. Ask your training program to provide a clear list of expectations and requirements for graduation and a method for you to accurately track them, such as the AGA Procedure Log. An online, mobile system will allow you to document cases immediately after you finish while the procedure is fresh in your mind. Taking an extra minute after each case will prevent headaches down the road. The faculty and your cofellows all know of the end of the year “procedure scavenger” (i.e., the fellow who searches for procedures and takes them from others to make sure they meet their numbers for graduation). Please don’t be that person.

A request for program directors

As GI educators, we all know the mention of procedure logs to fellows is typically accompanied by eye rolls. It doesn’t have to be that way. Provide your fellows with clear expectations and a quick, easy, and accurate way to track their accomplishments. Help them recognize the importance of an accurate and complete procedure log. Consider an online tracking system such as the AGA Procedure Log. Studies have demonstrated that a computer-based system increases compliance and accuracy.3 Not providing one will surely lead to difficulties in the long run and is a disservice to those we work to empower, educate, and prepare for success.

References

1. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Gastroenterology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2020 Jul 1. pp 21, 28. Accessed Sept. 13, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/144_Gastroenterology_2020.pdf.

2. Steven J et al. J Grad Med Educat. 2012;4(2):257-60.

3. Rowe BH et al. Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:2113–20.

Dr. Rezaizadeh is an assistant professor of medicine, associate program director, gastroenterology fellowship program, UConn Health, Farmington, Conn.

HM20 Virtual: Combating racism in medicine

HM20 Virtual session title

When Grief and Crises Intersect: Perspectives of a Black Physician in the Time of Two Pandemics

Presenter

Kimberly Manning, MD, FACP, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Kimberly Manning, associate vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Emory University, Atlanta, masterfully discussed the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and racism that we are currently experiencing and tried to describe the unique perspective of Black Americans.

Though it is easy to see that COVID-19 is a pandemic, racism is not always seen in this way. Dr. Manning demonstrated that when a pandemic is defined as “that which occurs over a wide geographic area and affects a high proportion of the population,” racism is absolutely a pandemic. She gave a great analogy: when sticking your hand into a bowl of Lucky Charms cereal, you do not expect to always end up with marshmallows alone, yet repeatedly, we see that Black Americans have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. We often hear that we are in unprecedented times but as far as racism is concerned, there is nothing new about this.

Dr. Manning discussed the life stories of her grandfather, her father, and even her own life’s milestones such as starting college, getting into medical school, finishing residency – all the way to becoming a full professor. She described how each of these instances, though marked by something beautiful, was also marked by something truly awful. Each time she had a reason to smile and laugh, there was something awful happening in the country simultaneously that showed us how racism was still present. Though this was one person’s story, all Black Americans, not just those working in health care, can recount similar stories, emotions, and feelings of grief.

Dr. Manning concluded by telling us how we can “Do the Work” to combat the pandemic of racism:

- Broaden your fund of knowledge: Read books, listen to podcasts, watch documentaries.

- Remember that people are grieving.

- Explore your implicit biases.

- Be a brave bystander.

- Avoid performative allyship.

Key takeaways

- Though the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, the pandemic of racism is not.

- The story of COVID-19 is the story of social determinants of health.

- We all must “Do the Work” to combat everyday racism and be cognizant of what our Black colleagues are going through every day.

Dr. Doraiswamy is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics and a med-peds hospitalist at The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus.

HM20 Virtual session title

When Grief and Crises Intersect: Perspectives of a Black Physician in the Time of Two Pandemics

Presenter

Kimberly Manning, MD, FACP, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Kimberly Manning, associate vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Emory University, Atlanta, masterfully discussed the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and racism that we are currently experiencing and tried to describe the unique perspective of Black Americans.

Though it is easy to see that COVID-19 is a pandemic, racism is not always seen in this way. Dr. Manning demonstrated that when a pandemic is defined as “that which occurs over a wide geographic area and affects a high proportion of the population,” racism is absolutely a pandemic. She gave a great analogy: when sticking your hand into a bowl of Lucky Charms cereal, you do not expect to always end up with marshmallows alone, yet repeatedly, we see that Black Americans have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. We often hear that we are in unprecedented times but as far as racism is concerned, there is nothing new about this.

Dr. Manning discussed the life stories of her grandfather, her father, and even her own life’s milestones such as starting college, getting into medical school, finishing residency – all the way to becoming a full professor. She described how each of these instances, though marked by something beautiful, was also marked by something truly awful. Each time she had a reason to smile and laugh, there was something awful happening in the country simultaneously that showed us how racism was still present. Though this was one person’s story, all Black Americans, not just those working in health care, can recount similar stories, emotions, and feelings of grief.

Dr. Manning concluded by telling us how we can “Do the Work” to combat the pandemic of racism:

- Broaden your fund of knowledge: Read books, listen to podcasts, watch documentaries.

- Remember that people are grieving.

- Explore your implicit biases.

- Be a brave bystander.

- Avoid performative allyship.

Key takeaways

- Though the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, the pandemic of racism is not.

- The story of COVID-19 is the story of social determinants of health.

- We all must “Do the Work” to combat everyday racism and be cognizant of what our Black colleagues are going through every day.

Dr. Doraiswamy is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics and a med-peds hospitalist at The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus.

HM20 Virtual session title

When Grief and Crises Intersect: Perspectives of a Black Physician in the Time of Two Pandemics

Presenter

Kimberly Manning, MD, FACP, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Kimberly Manning, associate vice chair of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Emory University, Atlanta, masterfully discussed the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and racism that we are currently experiencing and tried to describe the unique perspective of Black Americans.

Though it is easy to see that COVID-19 is a pandemic, racism is not always seen in this way. Dr. Manning demonstrated that when a pandemic is defined as “that which occurs over a wide geographic area and affects a high proportion of the population,” racism is absolutely a pandemic. She gave a great analogy: when sticking your hand into a bowl of Lucky Charms cereal, you do not expect to always end up with marshmallows alone, yet repeatedly, we see that Black Americans have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. We often hear that we are in unprecedented times but as far as racism is concerned, there is nothing new about this.

Dr. Manning discussed the life stories of her grandfather, her father, and even her own life’s milestones such as starting college, getting into medical school, finishing residency – all the way to becoming a full professor. She described how each of these instances, though marked by something beautiful, was also marked by something truly awful. Each time she had a reason to smile and laugh, there was something awful happening in the country simultaneously that showed us how racism was still present. Though this was one person’s story, all Black Americans, not just those working in health care, can recount similar stories, emotions, and feelings of grief.

Dr. Manning concluded by telling us how we can “Do the Work” to combat the pandemic of racism:

- Broaden your fund of knowledge: Read books, listen to podcasts, watch documentaries.

- Remember that people are grieving.

- Explore your implicit biases.

- Be a brave bystander.

- Avoid performative allyship.

Key takeaways

- Though the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, the pandemic of racism is not.

- The story of COVID-19 is the story of social determinants of health.

- We all must “Do the Work” to combat everyday racism and be cognizant of what our Black colleagues are going through every day.

Dr. Doraiswamy is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics and a med-peds hospitalist at The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus.

DAPA-CKD resets eGFR floor for safe SGLT2 inhibitor use

The dramatically positive safety and efficacy results from the DAPA-CKD trial, which showed that treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin significantly cut both chronic kidney disease progression and all-cause death in patients with or without type 2 diabetes, were also notable for broadening the population of patients eligible for this treatment to those in the upper range of stage 4 CKD.

Of the 4,304 CKD patients enrolled in DAPA-CKD, 624 (14%) had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, an unprecedented population to receive a drug from the SGLT2 inhibitor class in a reported study. The results provided definitive evidence for efficacy and safety in this range of renal function, said Hiddo J.L. Heerspink, Ph.D., at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Until now, the widely accepted lowest level for starting an SGLT2 inhibitor in routine practice has been an eGFR as low as 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Using SGLT2 inhibitors when eGFR is as low as 25

“It’s time to reduce the eGFR level for initiating an SGLT2 inhibitor to as low as 25,” said Dr. Heerspink, a professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands).

While conceding that this is primarily a decision to be made by guideline writers and regulatory bodies, he declared what he believed was established by the DAPA-CKD findings: “We’ve shown that dapagliflozin can be safely used in these patients. It is effective across the spectrum of kidney function.”

Other experts not associated with the study agreed.

The trial researchers were “brave” to enroll patients with eGFRs as low as 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and “we urgently need these agents in patients with an eGFR this low,” commented Chantal Mathieu, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium, and designated discussant for the report. Overall, she called the findings “spectacular,” a “landmark trial,” and a “winner.”

The study also set an new, lower floor for the level of albuminuria that can be usefully treated with dapagliflozin (Farxiga) by enrolling patients with a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio as low as 200 mg/g; the previous lower limit had been 300 mg/g, noted Dr. Mathieu. The new findings pose challenges to guideline writers, regulators who approve drug labels, and payers to a quickly make changes that will bring dapagliflozin to a wider number of patients with CKD.

Once the full DAPA-CKD results are reported, “it will change practice, and push the eGFR needle down” to as low as 25. It will also lower the albuminuria threshold for using dapagliflozin or other drugs in the class, commented David Z.I. Cherney, MD, a nephrologist at the University of Toronto. “It’s just one study,” he admitted, but the consistent renal benefits seen across several studies involving all four drugs in the SGLT2 inhibitor class will help hasten this change in identifying treatable patients, as well as expand the drug class to patients with CKD but no type 2 diabetes (T2D).

“I don’t think we’ve ever had stronger evidence” for drugs that can benefit both heart and renal function, plus the drug class is “very safe, and really easy to start” and maintain in patients, Dr. Cherney said in an interview. “It’s wonderful for these patients that we now have something new for treatment,” a drug with a “very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.”

Results show many dapagliflozin benefits

While this broadening of the range of patients proven to tolerate and benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor was an important consequence of DAPA-CKD, the study’s primary finding – that dapagliflozin was as safe and effective for slowing CKD progression in patients regardless of whether they also had T2D – will have an even bigger impact on expanding the target patient population. Showing efficacy in patients with CKD but without a T2D etiology, the status of about a third of the enrolled 4,304 patients, makes this treatment an option for “millions” of additional patients worldwide, said Dr. Heerspink. “These are the most common patients nephrologists see.” A major challenge now will be to do a better job finding patients with CKD who could benefit from dapagliflozin.

DAPA-CKD enrolled CKD patients based primarily on prespecified albuminuria and eGFR levels at more than 300 centers in 34 countries, including the United States. Virtually all patients, 97%, were on the only treatment now available with proven efficacy for slowing CKD, either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker. The small number of patients not on one of these drugs was because of poor tolerance.

The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a drop in eGFR of at least 50% from baseline. This occurred in 14.5% of patients who received placebo and in 9.2% of those who received dapagliflozin during a median follow-up of 2.4 years, a highly significant 39% relative risk reduction. Concurrently with the report at the virtual meeting the results also appeared online in the New England Journal of Medicine. This 5.3% cut in the absolute rate of the combined, primary adverse outcome converted into a number needed to treat of 19 to prevent 1 event during 2.4 years, a “much lower” number needed to treat than reported for renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in these types of patients, Dr. Heerspink said.

Notable positive secondary outcomes included a significant 31% relative cut (a 2% absolute decline) in all-cause mortality, “a major highlight” of the findings, Dr. Heerspink said. Dapagliflozin treatment also linked with a significant 29% relative cut in the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure.

“Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in patients with CKD,” explained David C. Wheeler, MD, a coinvestigator on the study and professor of kidney medicine at University College London. “The heart and kidney are intertwined. This is about cardiorenal disease.”

DAPA-CKD was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin. Dr. Heerspink has been a consultant to and received research funding from AstraZeneca. He has also received personal fees from Mundipharma and Novo Nordisk, and he has also served as consultant to several other companies with the honoraria being paid to his institution. Dr. Mathieu has had relationships with AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Cherney has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Wheeler has received personal fees from AstraZeneca and from several other companies.

SOURCE: Heerspink HJL et al. EASD 2020 and N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816.

The dramatically positive safety and efficacy results from the DAPA-CKD trial, which showed that treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin significantly cut both chronic kidney disease progression and all-cause death in patients with or without type 2 diabetes, were also notable for broadening the population of patients eligible for this treatment to those in the upper range of stage 4 CKD.

Of the 4,304 CKD patients enrolled in DAPA-CKD, 624 (14%) had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, an unprecedented population to receive a drug from the SGLT2 inhibitor class in a reported study. The results provided definitive evidence for efficacy and safety in this range of renal function, said Hiddo J.L. Heerspink, Ph.D., at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Until now, the widely accepted lowest level for starting an SGLT2 inhibitor in routine practice has been an eGFR as low as 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Using SGLT2 inhibitors when eGFR is as low as 25

“It’s time to reduce the eGFR level for initiating an SGLT2 inhibitor to as low as 25,” said Dr. Heerspink, a professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands).

While conceding that this is primarily a decision to be made by guideline writers and regulatory bodies, he declared what he believed was established by the DAPA-CKD findings: “We’ve shown that dapagliflozin can be safely used in these patients. It is effective across the spectrum of kidney function.”

Other experts not associated with the study agreed.

The trial researchers were “brave” to enroll patients with eGFRs as low as 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and “we urgently need these agents in patients with an eGFR this low,” commented Chantal Mathieu, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium, and designated discussant for the report. Overall, she called the findings “spectacular,” a “landmark trial,” and a “winner.”

The study also set an new, lower floor for the level of albuminuria that can be usefully treated with dapagliflozin (Farxiga) by enrolling patients with a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio as low as 200 mg/g; the previous lower limit had been 300 mg/g, noted Dr. Mathieu. The new findings pose challenges to guideline writers, regulators who approve drug labels, and payers to a quickly make changes that will bring dapagliflozin to a wider number of patients with CKD.

Once the full DAPA-CKD results are reported, “it will change practice, and push the eGFR needle down” to as low as 25. It will also lower the albuminuria threshold for using dapagliflozin or other drugs in the class, commented David Z.I. Cherney, MD, a nephrologist at the University of Toronto. “It’s just one study,” he admitted, but the consistent renal benefits seen across several studies involving all four drugs in the SGLT2 inhibitor class will help hasten this change in identifying treatable patients, as well as expand the drug class to patients with CKD but no type 2 diabetes (T2D).

“I don’t think we’ve ever had stronger evidence” for drugs that can benefit both heart and renal function, plus the drug class is “very safe, and really easy to start” and maintain in patients, Dr. Cherney said in an interview. “It’s wonderful for these patients that we now have something new for treatment,” a drug with a “very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.”

Results show many dapagliflozin benefits

While this broadening of the range of patients proven to tolerate and benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor was an important consequence of DAPA-CKD, the study’s primary finding – that dapagliflozin was as safe and effective for slowing CKD progression in patients regardless of whether they also had T2D – will have an even bigger impact on expanding the target patient population. Showing efficacy in patients with CKD but without a T2D etiology, the status of about a third of the enrolled 4,304 patients, makes this treatment an option for “millions” of additional patients worldwide, said Dr. Heerspink. “These are the most common patients nephrologists see.” A major challenge now will be to do a better job finding patients with CKD who could benefit from dapagliflozin.

DAPA-CKD enrolled CKD patients based primarily on prespecified albuminuria and eGFR levels at more than 300 centers in 34 countries, including the United States. Virtually all patients, 97%, were on the only treatment now available with proven efficacy for slowing CKD, either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker. The small number of patients not on one of these drugs was because of poor tolerance.

The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a drop in eGFR of at least 50% from baseline. This occurred in 14.5% of patients who received placebo and in 9.2% of those who received dapagliflozin during a median follow-up of 2.4 years, a highly significant 39% relative risk reduction. Concurrently with the report at the virtual meeting the results also appeared online in the New England Journal of Medicine. This 5.3% cut in the absolute rate of the combined, primary adverse outcome converted into a number needed to treat of 19 to prevent 1 event during 2.4 years, a “much lower” number needed to treat than reported for renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in these types of patients, Dr. Heerspink said.

Notable positive secondary outcomes included a significant 31% relative cut (a 2% absolute decline) in all-cause mortality, “a major highlight” of the findings, Dr. Heerspink said. Dapagliflozin treatment also linked with a significant 29% relative cut in the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure.

“Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in patients with CKD,” explained David C. Wheeler, MD, a coinvestigator on the study and professor of kidney medicine at University College London. “The heart and kidney are intertwined. This is about cardiorenal disease.”

DAPA-CKD was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin. Dr. Heerspink has been a consultant to and received research funding from AstraZeneca. He has also received personal fees from Mundipharma and Novo Nordisk, and he has also served as consultant to several other companies with the honoraria being paid to his institution. Dr. Mathieu has had relationships with AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Cherney has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Wheeler has received personal fees from AstraZeneca and from several other companies.

SOURCE: Heerspink HJL et al. EASD 2020 and N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816.

The dramatically positive safety and efficacy results from the DAPA-CKD trial, which showed that treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin significantly cut both chronic kidney disease progression and all-cause death in patients with or without type 2 diabetes, were also notable for broadening the population of patients eligible for this treatment to those in the upper range of stage 4 CKD.

Of the 4,304 CKD patients enrolled in DAPA-CKD, 624 (14%) had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, an unprecedented population to receive a drug from the SGLT2 inhibitor class in a reported study. The results provided definitive evidence for efficacy and safety in this range of renal function, said Hiddo J.L. Heerspink, Ph.D., at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Until now, the widely accepted lowest level for starting an SGLT2 inhibitor in routine practice has been an eGFR as low as 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Using SGLT2 inhibitors when eGFR is as low as 25

“It’s time to reduce the eGFR level for initiating an SGLT2 inhibitor to as low as 25,” said Dr. Heerspink, a professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands).

While conceding that this is primarily a decision to be made by guideline writers and regulatory bodies, he declared what he believed was established by the DAPA-CKD findings: “We’ve shown that dapagliflozin can be safely used in these patients. It is effective across the spectrum of kidney function.”

Other experts not associated with the study agreed.

The trial researchers were “brave” to enroll patients with eGFRs as low as 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and “we urgently need these agents in patients with an eGFR this low,” commented Chantal Mathieu, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium, and designated discussant for the report. Overall, she called the findings “spectacular,” a “landmark trial,” and a “winner.”

The study also set an new, lower floor for the level of albuminuria that can be usefully treated with dapagliflozin (Farxiga) by enrolling patients with a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio as low as 200 mg/g; the previous lower limit had been 300 mg/g, noted Dr. Mathieu. The new findings pose challenges to guideline writers, regulators who approve drug labels, and payers to a quickly make changes that will bring dapagliflozin to a wider number of patients with CKD.

Once the full DAPA-CKD results are reported, “it will change practice, and push the eGFR needle down” to as low as 25. It will also lower the albuminuria threshold for using dapagliflozin or other drugs in the class, commented David Z.I. Cherney, MD, a nephrologist at the University of Toronto. “It’s just one study,” he admitted, but the consistent renal benefits seen across several studies involving all four drugs in the SGLT2 inhibitor class will help hasten this change in identifying treatable patients, as well as expand the drug class to patients with CKD but no type 2 diabetes (T2D).

“I don’t think we’ve ever had stronger evidence” for drugs that can benefit both heart and renal function, plus the drug class is “very safe, and really easy to start” and maintain in patients, Dr. Cherney said in an interview. “It’s wonderful for these patients that we now have something new for treatment,” a drug with a “very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.”

Results show many dapagliflozin benefits

While this broadening of the range of patients proven to tolerate and benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor was an important consequence of DAPA-CKD, the study’s primary finding – that dapagliflozin was as safe and effective for slowing CKD progression in patients regardless of whether they also had T2D – will have an even bigger impact on expanding the target patient population. Showing efficacy in patients with CKD but without a T2D etiology, the status of about a third of the enrolled 4,304 patients, makes this treatment an option for “millions” of additional patients worldwide, said Dr. Heerspink. “These are the most common patients nephrologists see.” A major challenge now will be to do a better job finding patients with CKD who could benefit from dapagliflozin.

DAPA-CKD enrolled CKD patients based primarily on prespecified albuminuria and eGFR levels at more than 300 centers in 34 countries, including the United States. Virtually all patients, 97%, were on the only treatment now available with proven efficacy for slowing CKD, either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker. The small number of patients not on one of these drugs was because of poor tolerance.

The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a drop in eGFR of at least 50% from baseline. This occurred in 14.5% of patients who received placebo and in 9.2% of those who received dapagliflozin during a median follow-up of 2.4 years, a highly significant 39% relative risk reduction. Concurrently with the report at the virtual meeting the results also appeared online in the New England Journal of Medicine. This 5.3% cut in the absolute rate of the combined, primary adverse outcome converted into a number needed to treat of 19 to prevent 1 event during 2.4 years, a “much lower” number needed to treat than reported for renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in these types of patients, Dr. Heerspink said.

Notable positive secondary outcomes included a significant 31% relative cut (a 2% absolute decline) in all-cause mortality, “a major highlight” of the findings, Dr. Heerspink said. Dapagliflozin treatment also linked with a significant 29% relative cut in the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure.

“Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in patients with CKD,” explained David C. Wheeler, MD, a coinvestigator on the study and professor of kidney medicine at University College London. “The heart and kidney are intertwined. This is about cardiorenal disease.”

DAPA-CKD was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin. Dr. Heerspink has been a consultant to and received research funding from AstraZeneca. He has also received personal fees from Mundipharma and Novo Nordisk, and he has also served as consultant to several other companies with the honoraria being paid to his institution. Dr. Mathieu has had relationships with AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Cherney has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and several other companies. Dr. Wheeler has received personal fees from AstraZeneca and from several other companies.

SOURCE: Heerspink HJL et al. EASD 2020 and N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816.

FROM EASD 2020

Pruritic Axillary Plaques

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

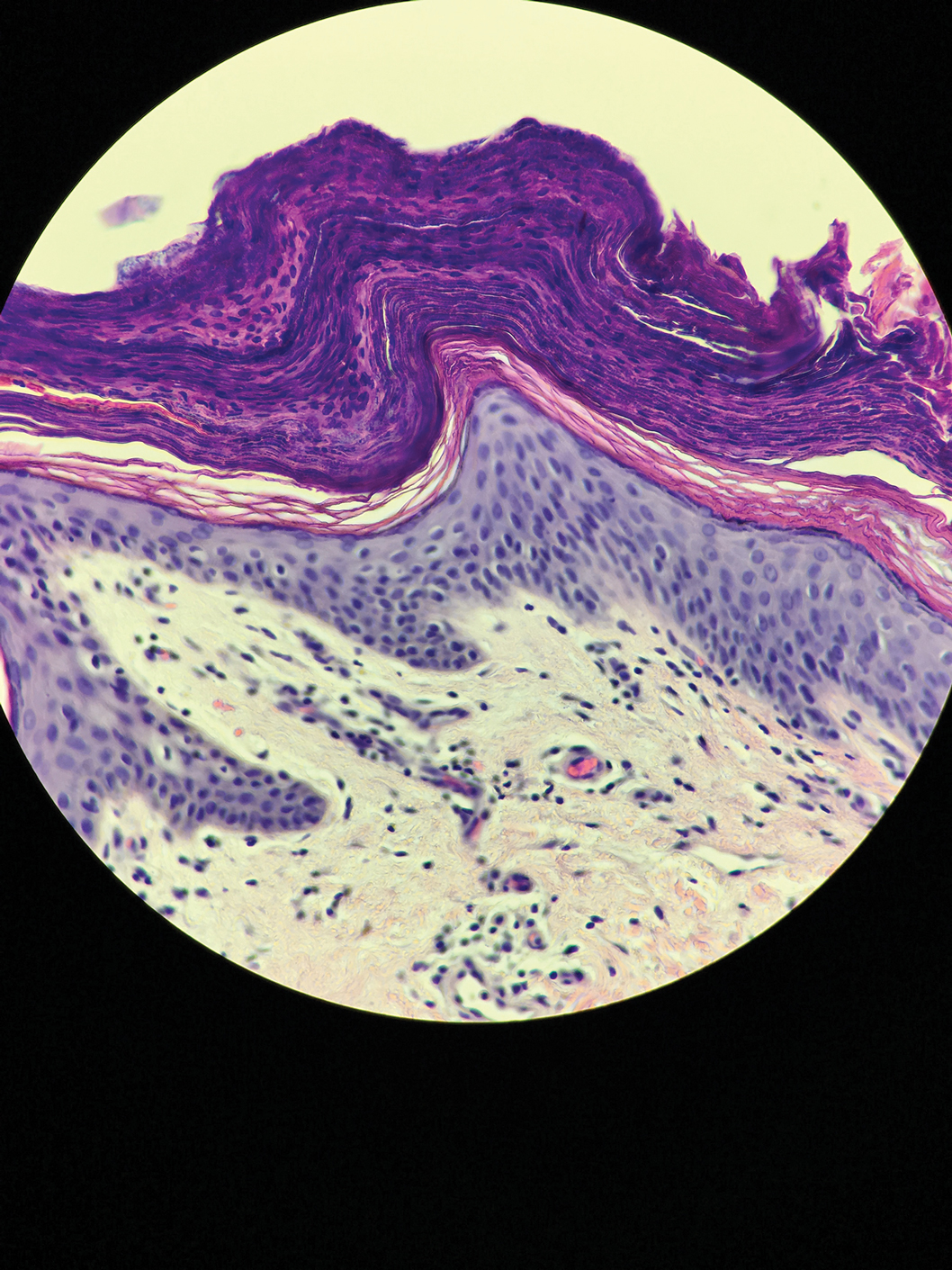

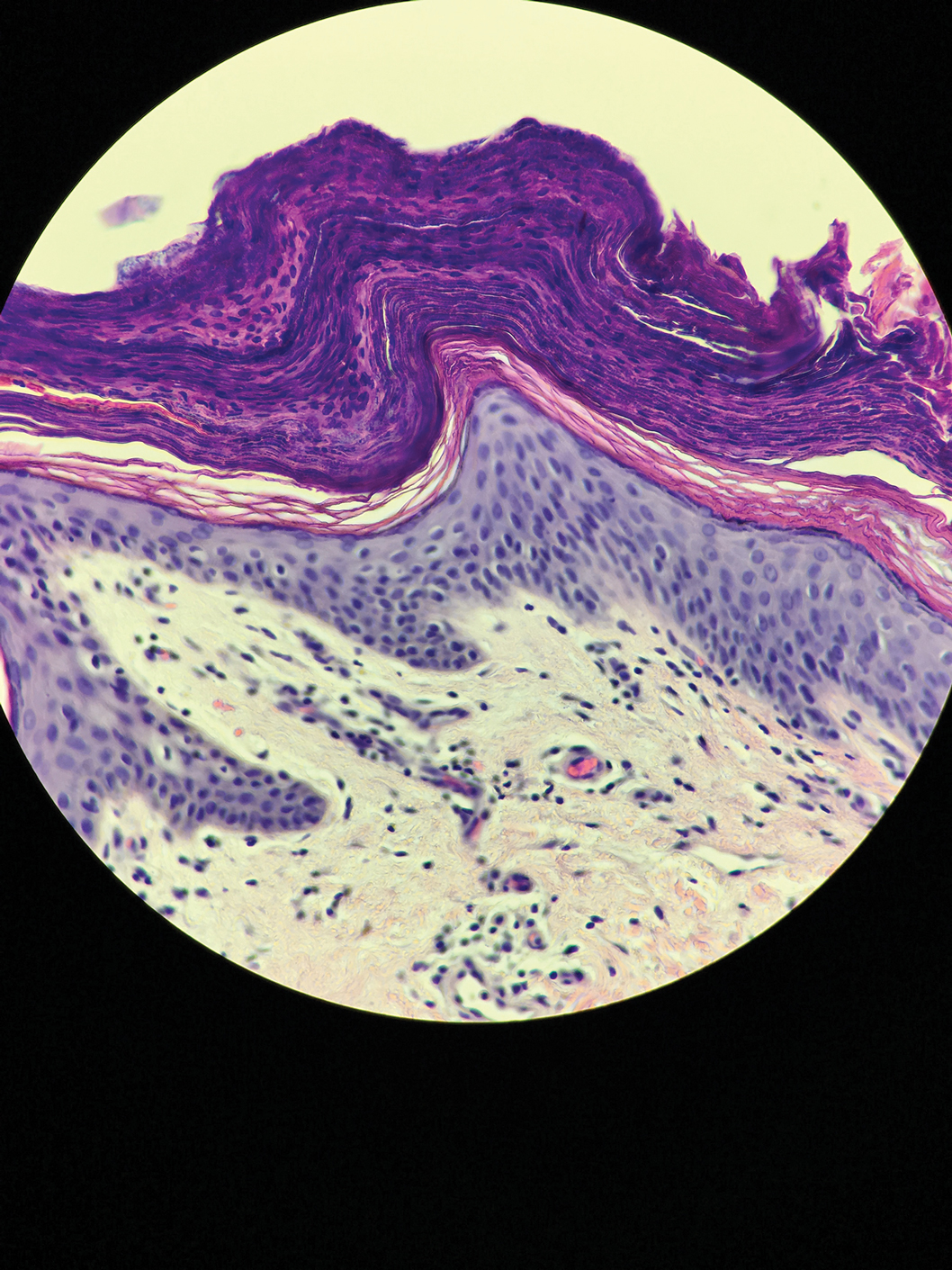

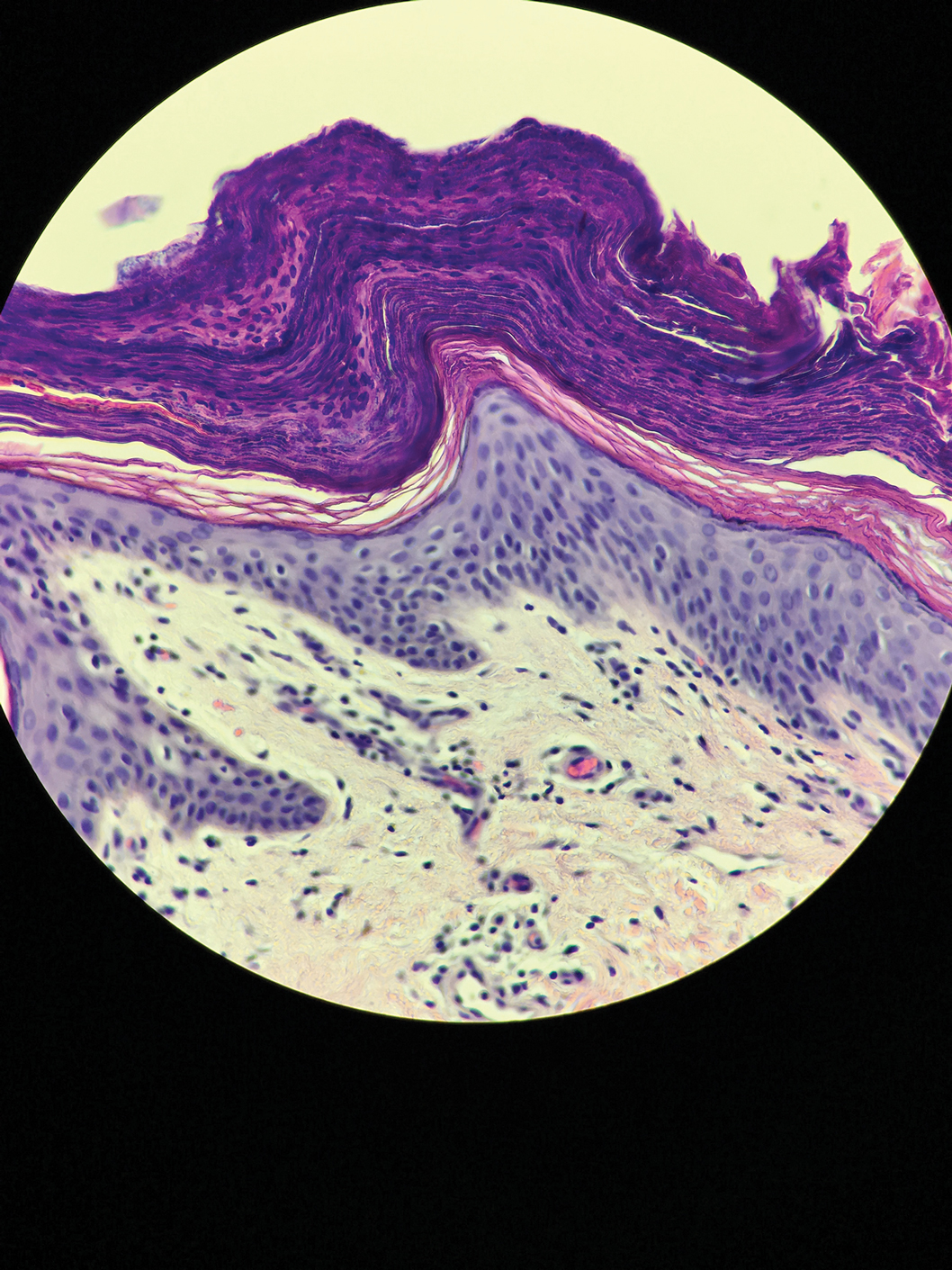

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

A 42-year-old man presented with pruritic axillary plaques of 6 months’ duration that were exacerbated by heat and friction. He maintained a very active lifestyle and used an antiperspirant regularly. He denied any family history of similar lesions. Thick emollients provided no relief. Physical examination demonstrated numerous soft, hyperkeratotic, waxy, yellowish brown papules coalescing into plaques localized to the bilateral axillary vaults, affecting the right axilla more than the left. Although some papules were firmly adherent to the skin, others were friable and easily removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, revealing an underlying, faintly erythematous base.

Physicians, make a plan to vote

In March 2020, following the announcement of the United States’ first death related to COVID-19, many physicians began using their voices to discuss the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). Many physicians, myself included, petitioned elected leaders at the community, state, and federal levels to address the PPE shortage.

Historically, physicians have advocated for improved public health. From seat belt laws in the 1980s and 1990s to the Affordable Care Act in the 2000s, physicians have testified at the community, state, and federal levels to advocate for the health and safety of our patients and the public. Yet while we have been making our voices heard, we are often silent at the ballot box.

In the 1996 and 2000 elections, physicians voted 9% less often than the general public, and compared with lawyers – professionals with similar educational attainment and finances – physicians voted 22% less often.1 It is unclear why physicians are less likely to vote. In a 2016 article, David Grande, MD, and Katrina Armstrong, MD, postulated that physicians may not vote because our work hours create barriers to visiting polls.2

Despite our lack of engagement at the ballot box, voting is important to improving our patients’ social determinants of health. In a recently published systematic review, the authors found several studies supporting the association between voting and social determinants of health. Their review found that, when large numbers of people from communities participated in voting, it translated into greater influence over determining who held political power in that community. Those with power introduced and supported policies responding to their constituents’ needs, ultimately influencing their constituents’ social determinants of health.3 By voting, we as physicians are helping to address the social determinants of health in our communities.

Many medical students have been doing their part to improve the social determinants of health in their communities by pledging to vote. In 2018, the American Medical Student Association launched their “Med Out the Vote” initiative prior to the election. The organization called on all health care providers and providers in training to pledge to vote in the election.4 They are continuing these efforts for the 2020 elections.

We should join our nation’s medical students by also pledging to vote. To begin, we can all Make A Plan To Vote. Each plan should include the following:

- Register to vote: In many states eligible voters can register online.

- Request an absentee ballot: Many states require registered voters to request absentee ballots online or by mail.

- Vote: Submit an absentee ballot prior to election or vote in-person on election day. Some counties allow voting early in person.

In practice, our plans will differ slightly because each state has its own election laws.

This election season let us ensure all physician voices are heard. Make A Plan To Vote for your patients and communities.

Dr. Kumar is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. She is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do Doctors Vote? J Gen Intern Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. Grande D, Armstrong K. Will Physicians Vote? Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:814-5.

3. Brown CL et al. Voting, health and interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00133-6.

4. American Medical Student Association. AMSA Launches Med Out the Vote Campaign, Call to Action. 2018 Jul 29. Accessed 2020 Sep 14. https://www.amsa.org/about/amsa-press-room/amsa-launches-med-out-the-vote-campaign-call-to-action/

In March 2020, following the announcement of the United States’ first death related to COVID-19, many physicians began using their voices to discuss the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). Many physicians, myself included, petitioned elected leaders at the community, state, and federal levels to address the PPE shortage.

Historically, physicians have advocated for improved public health. From seat belt laws in the 1980s and 1990s to the Affordable Care Act in the 2000s, physicians have testified at the community, state, and federal levels to advocate for the health and safety of our patients and the public. Yet while we have been making our voices heard, we are often silent at the ballot box.

In the 1996 and 2000 elections, physicians voted 9% less often than the general public, and compared with lawyers – professionals with similar educational attainment and finances – physicians voted 22% less often.1 It is unclear why physicians are less likely to vote. In a 2016 article, David Grande, MD, and Katrina Armstrong, MD, postulated that physicians may not vote because our work hours create barriers to visiting polls.2

Despite our lack of engagement at the ballot box, voting is important to improving our patients’ social determinants of health. In a recently published systematic review, the authors found several studies supporting the association between voting and social determinants of health. Their review found that, when large numbers of people from communities participated in voting, it translated into greater influence over determining who held political power in that community. Those with power introduced and supported policies responding to their constituents’ needs, ultimately influencing their constituents’ social determinants of health.3 By voting, we as physicians are helping to address the social determinants of health in our communities.

Many medical students have been doing their part to improve the social determinants of health in their communities by pledging to vote. In 2018, the American Medical Student Association launched their “Med Out the Vote” initiative prior to the election. The organization called on all health care providers and providers in training to pledge to vote in the election.4 They are continuing these efforts for the 2020 elections.

We should join our nation’s medical students by also pledging to vote. To begin, we can all Make A Plan To Vote. Each plan should include the following:

- Register to vote: In many states eligible voters can register online.

- Request an absentee ballot: Many states require registered voters to request absentee ballots online or by mail.

- Vote: Submit an absentee ballot prior to election or vote in-person on election day. Some counties allow voting early in person.

In practice, our plans will differ slightly because each state has its own election laws.

This election season let us ensure all physician voices are heard. Make A Plan To Vote for your patients and communities.

Dr. Kumar is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. She is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do Doctors Vote? J Gen Intern Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. Grande D, Armstrong K. Will Physicians Vote? Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:814-5.

3. Brown CL et al. Voting, health and interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00133-6.

4. American Medical Student Association. AMSA Launches Med Out the Vote Campaign, Call to Action. 2018 Jul 29. Accessed 2020 Sep 14. https://www.amsa.org/about/amsa-press-room/amsa-launches-med-out-the-vote-campaign-call-to-action/

In March 2020, following the announcement of the United States’ first death related to COVID-19, many physicians began using their voices to discuss the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). Many physicians, myself included, petitioned elected leaders at the community, state, and federal levels to address the PPE shortage.

Historically, physicians have advocated for improved public health. From seat belt laws in the 1980s and 1990s to the Affordable Care Act in the 2000s, physicians have testified at the community, state, and federal levels to advocate for the health and safety of our patients and the public. Yet while we have been making our voices heard, we are often silent at the ballot box.

In the 1996 and 2000 elections, physicians voted 9% less often than the general public, and compared with lawyers – professionals with similar educational attainment and finances – physicians voted 22% less often.1 It is unclear why physicians are less likely to vote. In a 2016 article, David Grande, MD, and Katrina Armstrong, MD, postulated that physicians may not vote because our work hours create barriers to visiting polls.2

Despite our lack of engagement at the ballot box, voting is important to improving our patients’ social determinants of health. In a recently published systematic review, the authors found several studies supporting the association between voting and social determinants of health. Their review found that, when large numbers of people from communities participated in voting, it translated into greater influence over determining who held political power in that community. Those with power introduced and supported policies responding to their constituents’ needs, ultimately influencing their constituents’ social determinants of health.3 By voting, we as physicians are helping to address the social determinants of health in our communities.

Many medical students have been doing their part to improve the social determinants of health in their communities by pledging to vote. In 2018, the American Medical Student Association launched their “Med Out the Vote” initiative prior to the election. The organization called on all health care providers and providers in training to pledge to vote in the election.4 They are continuing these efforts for the 2020 elections.

We should join our nation’s medical students by also pledging to vote. To begin, we can all Make A Plan To Vote. Each plan should include the following:

- Register to vote: In many states eligible voters can register online.

- Request an absentee ballot: Many states require registered voters to request absentee ballots online or by mail.

- Vote: Submit an absentee ballot prior to election or vote in-person on election day. Some counties allow voting early in person.

In practice, our plans will differ slightly because each state has its own election laws.

This election season let us ensure all physician voices are heard. Make A Plan To Vote for your patients and communities.

Dr. Kumar is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. She is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

References

1. Grande D et al. Do Doctors Vote? J Gen Intern Med. 2007 May;22(5):585-9.

2. Grande D, Armstrong K. Will Physicians Vote? Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:814-5.

3. Brown CL et al. Voting, health and interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00133-6.

4. American Medical Student Association. AMSA Launches Med Out the Vote Campaign, Call to Action. 2018 Jul 29. Accessed 2020 Sep 14. https://www.amsa.org/about/amsa-press-room/amsa-launches-med-out-the-vote-campaign-call-to-action/

Social media and health information: Empowering or misleading?

The search engine giants, Dr. Google or Dr. Bing, are visited by most of our patients before seeking medical help. In 1976, medical student Tom Ferguson, MD, first coined the term e-Patient. It means a health consumer who uses the Internet to gather information about a medical condition for themselves or on behalf of family and friends and uses electronic communication tools to cope with medical conditions. Dr. Ferguson described e-Patients as “empowered medical consumers.”1

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media and networking platforms – such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, WhatsApp, online health support groups – are used increasingly by e-Patients to gather critical health information. Health care providers often take a conflicted stand on the use of social media. Though we want our patients to read about their illnesses and make informed choices, we often get frustrated by misdiagnoses, misinformation, and disinformation that comes with it.

According to a study investigating the differential diffusion of news stories distributed on Twitter from 2006 to 2017, fake news was considered more novel than true news, and people were more likely to share novel information.2 Bots accelerated the spread of true and fake news at the same rate, implying that fake news spreads more than the truth because humans, not robots, are more likely to spread it. Social media has promoted some of the best health campaigns, like public cancer awareness, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, World Heart Day, and others. At the same time, it has also provided a platform for antivaccination activists, dangerous and unproven alternative cancer therapies, weight loss pills, and nutrition plans.

According to a Pew Research Center survey, 72% of adult Internet users had searched online for information about a range of health issues of their own or for others in the past 12 months.3 A survey from 2019-2020 showed that those who relied on social media for news were among the least knowledgeable about key facts during the COVID-19 outbreak.4 About 74% of public posts about COVID-19 were linked to news organizations, while just 1% linked to health and science sites.5 While social media has emerged as one of the most significant health information sources, it famously has only a few safeguards in place against medical misinformation. Requiring responsibility and regulations for accurate or evidence-based information walks a thin line on infringing freedom of speech. Medical misinformation related to COVID-19 has become as contagious as the virus itself.

In February 2020, the World Health Organization warned that a massive ‘Infodemic’ had accompanied the COVID-19 outbreak, with an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not, making it difficult for people to find reliable sources and trustworthy information.6 The Black immunity myth, groups opposing vaccines, campaigns against 5G mobile phone networks, suggestions that SARS-CoV-2 was an engineered bioweapon, and online rumors leading to mob attacks in India and mass poisonings in Iran are some of the misleading health information that has circulated related to COVID-19.

In the Web 2.0 era, in which credible health information comes packaged with divisive and misleading information, social media’s full impact on health care, health outcomes, and mental health has yet to be explored. Social networks and media sharing networks have recently announced initiatives to stop misinformation and disinformation by fact-checking, flagging, issuing warnings, and deleting misinformation or misleading content. Providing links to more and correct information and partnering with health and science organizations can also encourage the spread of verifiable information.

While we have yet to see if social media safeguards are adequate, the medical community needs to proactively educate patients on the appropriate use of social media for health information, e-Health literacy, and media health literacy. Like health care providers evaluating scientific papers, we need to cultivate e-Patients’ ability to seek, evaluate, understand, and convey health information from electronic sources. Although the measurement and training tools for e-Health and media health literacy are still scarce, a good place to start could be to have simple conversations with patients. Encouraging patients to critically analyze online information, use credible social media sources, and recognizing the warnings, red flags, and links on unreliable information are some of the discussions worth considering. Equally important is to discourage patients from changing health behaviors or practices based on unverified social media resources and discussing the possible impact of medical misinformation.

A practical approach for e-Patients could be to ask the Five Ws, considered fundamental in information gathering: Who, What, Why, When, and Where.7,8