User login

For MD-IQ use only

Vitamin D shows no survival benefit in nondeficient elderly

, including mortality linked to cardiovascular disease, new results from a large, placebo-controlled trial show.

“The take-home message is that routine vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of the dosing regimen, is unlikely to be beneficial in a population with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency,” first author Rachel E. Neale, PhD, of the Population Health Department, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, in Brisbane, Australia, told this news organization.

Despite extensive previous research on vitamin D supplementation, “mortality has not been the primary outcome in any previous large trial of high-dose vitamin D supplementation,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted. The results, published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, are from the D-Health trial.

With more than 20,000 participants, this is the largest intermittent-dosing trial to date, the authors noted. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality.

In an accompanying editorial, Inez Schoenmakers, PhD, noted that “the findings [are] highly relevant for population policy, owing to the study’s population-based design, large scale, and long duration.”

This new “research contributes to the concept that improving vitamin D status with supplementation in a mostly vitamin D-replete older population does not influence all-cause mortality,” Dr. Schoenmakers, of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, said in an interview.

“This is not dissimilar to research with many other nutrients showing that increasing intake above the adequate intake has no further health benefits,” she added.

D-Health Trial

The D-Health Trial involved 21,315 participants in Australia, enrolled between February 2014 and June 2015, who had not been screened for vitamin D deficiency but were largely considered to be vitamin D replete. They were a mean age of 69.3 years and 54% were men.

Participants were randomized 1:1 to a once-monthly oral vitamin D3 supplementation of 60,000 IU (n = 10,662) or a placebo capsule (n = 10,653).

They were permitted to take up to 2,000 IU/day of supplemental vitamin D in addition to the study protocol and had no history of kidney stones, hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, or sarcoidosis.

Over a median follow-up of 5.7 years, there were 1,100 deaths: 562 in the vitamin D group (5.3%) and 538 in the placebo group (5.1%). With a hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 1.04, the difference was not significant (P = .47).

There were also no significant differences in terms of mortality from cardiovascular disease (HR, 0.96; P = .77), cancer (HR, 1.15; P = .13), or other causes (HR, 0.83; P = .15).

Rates of total adverse events between the two groups, including hypercalcemia and kidney stones, were similar.

An exploratory analysis excluding the first 2 years of follow-up in fact showed a numerically higher hazard ratio for cancer mortality in the vitamin D group versus no supplementation (HR, 1.24; P = .05). However, the authors noted that the effect was “not apparent when the analysis was restricted to deaths that were coded by the study team and not officially coded.”

Nevertheless, “our findings, from a large study in an unscreened population, give pause to earlier reports that vitamin D supplements might reduce cancer mortality,” they underscored.

Retention and adherence in the study were high, each exceeding 80%. Although blood samples were not collected at baseline, samples from 3,943 randomly sampled participants during follow-up showed mean serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations of 77 nmol/L in the placebo group and 115 nmol/L in the vitamin D group, both within the normal range of 50-125 nmol/L.

Findings supported by previous research

The trial results are consistent with those of prior large studies and meta-analyses of older adults with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency showing that vitamin D3 supplementation, regardless of whether taken daily or monthly, is not likely to have an effect on all-cause mortality.

In the US VITAL trial, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, among 25,871 participants administered 2,000 IU/day of vitamin D3 for a median of 5.3 years, there was no reduction in all-cause mortality.

The ViDA trial of 5,110 older adults in New Zealand, published in 2019 in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, also showed monthly vitamin D3 supplementation of 100,000 IU for a median of 3.3 years was not associated with a benefit in people who were not deficient.

“In total, the results from the large trials and meta-analyses suggest that routine supplementation of older adults in populations with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is unlikely to reduce the rate of all-cause mortality,” Dr. Neale and colleagues concluded.

Longer-term supplementation beneficial?

The population was limited to older adults and the study had a relatively short follow-up period, which Dr. Neale noted was necessary for pragmatic reasons.

“Our primary outcome was all-cause mortality, so to have sufficient deaths we either needed to study older adults or a much larger sample of younger adults,” she explained.

“However, we felt that [the former] ... had biological justification, as there is evidence that vitamin D plays a role later in the course of a number of diseases, with potential impacts on mortality.”

She noted that recent studies evaluating genetically predicted concentrations of serum 25(OH)D have further shown no link between those levels and all-cause mortality, stroke, or coronary heart disease.

“This confirms the statement that vitamin D is unlikely to be beneficial in people who are not vitamin D deficient, irrespective of whether supplementation occurs over the short or longer term,” Dr. Neale said.

The source of vitamin D, itself, is another consideration, with ongoing speculation of differences in benefits between dietary or supplementation sources versus sunlight exposure.

“Exposure to ultraviolet radiation, for which serum 25(OH)D concentration is a good marker, might confer benefits not mediated by vitamin D,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted.

They added that the results in the older Australian population “cannot be generalized to populations with a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, or with a greater proportion of people not of White ancestry, than the study population.”

Ten-year mortality rates from the D-Health trial are expected to be reported in the future.

Strategies still needed to address vitamin D deficiency

Further commenting on the findings, Dr. Schoenmakers underscored that “vitamin D deficiency is very common worldwide, [and] more should be done to develop strategies to address the needs of those groups and populations that are at risk of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency.”

That said, the D-Health study is important in helping to distinguish when supplementation may – and may not – be of benefit, she noted.

“This and other research in the past 15 years have contributed to our understanding [of] what the ranges of vitamin D status are [in which] health consequences may be anticipated.”

The D-Health Trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Neale and Dr. Schoenmakers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, including mortality linked to cardiovascular disease, new results from a large, placebo-controlled trial show.

“The take-home message is that routine vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of the dosing regimen, is unlikely to be beneficial in a population with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency,” first author Rachel E. Neale, PhD, of the Population Health Department, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, in Brisbane, Australia, told this news organization.

Despite extensive previous research on vitamin D supplementation, “mortality has not been the primary outcome in any previous large trial of high-dose vitamin D supplementation,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted. The results, published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, are from the D-Health trial.

With more than 20,000 participants, this is the largest intermittent-dosing trial to date, the authors noted. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality.

In an accompanying editorial, Inez Schoenmakers, PhD, noted that “the findings [are] highly relevant for population policy, owing to the study’s population-based design, large scale, and long duration.”

This new “research contributes to the concept that improving vitamin D status with supplementation in a mostly vitamin D-replete older population does not influence all-cause mortality,” Dr. Schoenmakers, of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, said in an interview.

“This is not dissimilar to research with many other nutrients showing that increasing intake above the adequate intake has no further health benefits,” she added.

D-Health Trial

The D-Health Trial involved 21,315 participants in Australia, enrolled between February 2014 and June 2015, who had not been screened for vitamin D deficiency but were largely considered to be vitamin D replete. They were a mean age of 69.3 years and 54% were men.

Participants were randomized 1:1 to a once-monthly oral vitamin D3 supplementation of 60,000 IU (n = 10,662) or a placebo capsule (n = 10,653).

They were permitted to take up to 2,000 IU/day of supplemental vitamin D in addition to the study protocol and had no history of kidney stones, hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, or sarcoidosis.

Over a median follow-up of 5.7 years, there were 1,100 deaths: 562 in the vitamin D group (5.3%) and 538 in the placebo group (5.1%). With a hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 1.04, the difference was not significant (P = .47).

There were also no significant differences in terms of mortality from cardiovascular disease (HR, 0.96; P = .77), cancer (HR, 1.15; P = .13), or other causes (HR, 0.83; P = .15).

Rates of total adverse events between the two groups, including hypercalcemia and kidney stones, were similar.

An exploratory analysis excluding the first 2 years of follow-up in fact showed a numerically higher hazard ratio for cancer mortality in the vitamin D group versus no supplementation (HR, 1.24; P = .05). However, the authors noted that the effect was “not apparent when the analysis was restricted to deaths that were coded by the study team and not officially coded.”

Nevertheless, “our findings, from a large study in an unscreened population, give pause to earlier reports that vitamin D supplements might reduce cancer mortality,” they underscored.

Retention and adherence in the study were high, each exceeding 80%. Although blood samples were not collected at baseline, samples from 3,943 randomly sampled participants during follow-up showed mean serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations of 77 nmol/L in the placebo group and 115 nmol/L in the vitamin D group, both within the normal range of 50-125 nmol/L.

Findings supported by previous research

The trial results are consistent with those of prior large studies and meta-analyses of older adults with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency showing that vitamin D3 supplementation, regardless of whether taken daily or monthly, is not likely to have an effect on all-cause mortality.

In the US VITAL trial, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, among 25,871 participants administered 2,000 IU/day of vitamin D3 for a median of 5.3 years, there was no reduction in all-cause mortality.

The ViDA trial of 5,110 older adults in New Zealand, published in 2019 in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, also showed monthly vitamin D3 supplementation of 100,000 IU for a median of 3.3 years was not associated with a benefit in people who were not deficient.

“In total, the results from the large trials and meta-analyses suggest that routine supplementation of older adults in populations with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is unlikely to reduce the rate of all-cause mortality,” Dr. Neale and colleagues concluded.

Longer-term supplementation beneficial?

The population was limited to older adults and the study had a relatively short follow-up period, which Dr. Neale noted was necessary for pragmatic reasons.

“Our primary outcome was all-cause mortality, so to have sufficient deaths we either needed to study older adults or a much larger sample of younger adults,” she explained.

“However, we felt that [the former] ... had biological justification, as there is evidence that vitamin D plays a role later in the course of a number of diseases, with potential impacts on mortality.”

She noted that recent studies evaluating genetically predicted concentrations of serum 25(OH)D have further shown no link between those levels and all-cause mortality, stroke, or coronary heart disease.

“This confirms the statement that vitamin D is unlikely to be beneficial in people who are not vitamin D deficient, irrespective of whether supplementation occurs over the short or longer term,” Dr. Neale said.

The source of vitamin D, itself, is another consideration, with ongoing speculation of differences in benefits between dietary or supplementation sources versus sunlight exposure.

“Exposure to ultraviolet radiation, for which serum 25(OH)D concentration is a good marker, might confer benefits not mediated by vitamin D,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted.

They added that the results in the older Australian population “cannot be generalized to populations with a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, or with a greater proportion of people not of White ancestry, than the study population.”

Ten-year mortality rates from the D-Health trial are expected to be reported in the future.

Strategies still needed to address vitamin D deficiency

Further commenting on the findings, Dr. Schoenmakers underscored that “vitamin D deficiency is very common worldwide, [and] more should be done to develop strategies to address the needs of those groups and populations that are at risk of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency.”

That said, the D-Health study is important in helping to distinguish when supplementation may – and may not – be of benefit, she noted.

“This and other research in the past 15 years have contributed to our understanding [of] what the ranges of vitamin D status are [in which] health consequences may be anticipated.”

The D-Health Trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Neale and Dr. Schoenmakers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, including mortality linked to cardiovascular disease, new results from a large, placebo-controlled trial show.

“The take-home message is that routine vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of the dosing regimen, is unlikely to be beneficial in a population with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency,” first author Rachel E. Neale, PhD, of the Population Health Department, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, in Brisbane, Australia, told this news organization.

Despite extensive previous research on vitamin D supplementation, “mortality has not been the primary outcome in any previous large trial of high-dose vitamin D supplementation,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted. The results, published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, are from the D-Health trial.

With more than 20,000 participants, this is the largest intermittent-dosing trial to date, the authors noted. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality.

In an accompanying editorial, Inez Schoenmakers, PhD, noted that “the findings [are] highly relevant for population policy, owing to the study’s population-based design, large scale, and long duration.”

This new “research contributes to the concept that improving vitamin D status with supplementation in a mostly vitamin D-replete older population does not influence all-cause mortality,” Dr. Schoenmakers, of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, England, said in an interview.

“This is not dissimilar to research with many other nutrients showing that increasing intake above the adequate intake has no further health benefits,” she added.

D-Health Trial

The D-Health Trial involved 21,315 participants in Australia, enrolled between February 2014 and June 2015, who had not been screened for vitamin D deficiency but were largely considered to be vitamin D replete. They were a mean age of 69.3 years and 54% were men.

Participants were randomized 1:1 to a once-monthly oral vitamin D3 supplementation of 60,000 IU (n = 10,662) or a placebo capsule (n = 10,653).

They were permitted to take up to 2,000 IU/day of supplemental vitamin D in addition to the study protocol and had no history of kidney stones, hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, or sarcoidosis.

Over a median follow-up of 5.7 years, there were 1,100 deaths: 562 in the vitamin D group (5.3%) and 538 in the placebo group (5.1%). With a hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality of 1.04, the difference was not significant (P = .47).

There were also no significant differences in terms of mortality from cardiovascular disease (HR, 0.96; P = .77), cancer (HR, 1.15; P = .13), or other causes (HR, 0.83; P = .15).

Rates of total adverse events between the two groups, including hypercalcemia and kidney stones, were similar.

An exploratory analysis excluding the first 2 years of follow-up in fact showed a numerically higher hazard ratio for cancer mortality in the vitamin D group versus no supplementation (HR, 1.24; P = .05). However, the authors noted that the effect was “not apparent when the analysis was restricted to deaths that were coded by the study team and not officially coded.”

Nevertheless, “our findings, from a large study in an unscreened population, give pause to earlier reports that vitamin D supplements might reduce cancer mortality,” they underscored.

Retention and adherence in the study were high, each exceeding 80%. Although blood samples were not collected at baseline, samples from 3,943 randomly sampled participants during follow-up showed mean serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations of 77 nmol/L in the placebo group and 115 nmol/L in the vitamin D group, both within the normal range of 50-125 nmol/L.

Findings supported by previous research

The trial results are consistent with those of prior large studies and meta-analyses of older adults with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency showing that vitamin D3 supplementation, regardless of whether taken daily or monthly, is not likely to have an effect on all-cause mortality.

In the US VITAL trial, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, among 25,871 participants administered 2,000 IU/day of vitamin D3 for a median of 5.3 years, there was no reduction in all-cause mortality.

The ViDA trial of 5,110 older adults in New Zealand, published in 2019 in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, also showed monthly vitamin D3 supplementation of 100,000 IU for a median of 3.3 years was not associated with a benefit in people who were not deficient.

“In total, the results from the large trials and meta-analyses suggest that routine supplementation of older adults in populations with a low prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is unlikely to reduce the rate of all-cause mortality,” Dr. Neale and colleagues concluded.

Longer-term supplementation beneficial?

The population was limited to older adults and the study had a relatively short follow-up period, which Dr. Neale noted was necessary for pragmatic reasons.

“Our primary outcome was all-cause mortality, so to have sufficient deaths we either needed to study older adults or a much larger sample of younger adults,” she explained.

“However, we felt that [the former] ... had biological justification, as there is evidence that vitamin D plays a role later in the course of a number of diseases, with potential impacts on mortality.”

She noted that recent studies evaluating genetically predicted concentrations of serum 25(OH)D have further shown no link between those levels and all-cause mortality, stroke, or coronary heart disease.

“This confirms the statement that vitamin D is unlikely to be beneficial in people who are not vitamin D deficient, irrespective of whether supplementation occurs over the short or longer term,” Dr. Neale said.

The source of vitamin D, itself, is another consideration, with ongoing speculation of differences in benefits between dietary or supplementation sources versus sunlight exposure.

“Exposure to ultraviolet radiation, for which serum 25(OH)D concentration is a good marker, might confer benefits not mediated by vitamin D,” Dr. Neale and coauthors noted.

They added that the results in the older Australian population “cannot be generalized to populations with a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, or with a greater proportion of people not of White ancestry, than the study population.”

Ten-year mortality rates from the D-Health trial are expected to be reported in the future.

Strategies still needed to address vitamin D deficiency

Further commenting on the findings, Dr. Schoenmakers underscored that “vitamin D deficiency is very common worldwide, [and] more should be done to develop strategies to address the needs of those groups and populations that are at risk of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency.”

That said, the D-Health study is important in helping to distinguish when supplementation may – and may not – be of benefit, she noted.

“This and other research in the past 15 years have contributed to our understanding [of] what the ranges of vitamin D status are [in which] health consequences may be anticipated.”

The D-Health Trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Neale and Dr. Schoenmakers have reported no relevant financial relationships.

version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

It’s time for moonshot thinking in psychiatry

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

President John F. Kennedy, May 25, 1961

Despite significant progress, there remain many unmet needs in psychiatry. These include a granular understanding of the neurobiology of various psychopathologies, an objective and valid diagnostic schema, and disease-modifying treatments for chronic and disabling psychiatric disorders. Several moonshots are needed to address those festering needs.

A “moonshot” is an extremely ambitious, dramatic, imaginative, and inspiring goal. Landing on the Moon was generally believed to be impossible when President Kennedy boldly set that as a goal for the United States in 1961. Yet, 8 short years later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped off the lunar module ladder onto the Moon’s surface, a feat that captured the imagination of the nation and the world. I distinctly remember watching it on television with amazement as a young boy. It was a surreal experience. That’s what achieving a moonshot feels like.

Successful organizations should always have 1 or more moonshots (American Psychiatric Association and National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], are you listening?). Setting lofty goals that require monumental determination and effort to accomplish will have a transformative, long-lasting impact. The construction of the Panama Canal to connect 2 oceans and the Manhattan Project to develop the first nuclear bomb, which ended World War II, are examples of moonshots that continue to reverberate. A more recent moonshot is the driverless car, which in the past was a laughable idea but is now a reality that will change society and the world in many ways. Innovative billionaire moguls now speak loudly about colonizing Mars, which sounds improbable and highly risky, but it’s a moonshot that may be achieved within a few years. Establishing world peace is a moonshot that requires collective Kennedy-esque vision and motivation among world leaders, which currently is sadly lacking.

So, for contemporary psychiatry, what is the equivalent of landing on the Moon? Here is the list that pops in my brain’s mind (let us know which of these would be your top 3 moonshots by taking our survey at https://bit.ly/3qkKqTa):

- A cure for schizophrenia (across positive, negative, and cognitive symptom domains)

- A cure for mood disorders, unipolar and bipolar (including suicide)

- A cure for anxiety disorders

- A cure for obsessive-compulsive disorder

- A cure for posttraumatic stress disorder

- A cure for alcoholism/addiction

- A cure for autism

- A cure for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

- A cure for personality disorders, especially antisocial and borderline

- A cure for the visceral hatred across political parties that permeates our society (obviously not a psychiatric category, but perhaps it should be added to DSM because it is so destructive).

Those moonshots may be regarded as absurd, and totally unachievable, but so was landing on the Moon, until it was accomplished. Psychiatry must stop thinking small and being content with tiny advances (which is like changing the chairs to more comfortable sofas on the deck of the Titanic and calling it “progress…”). Psychiatry needs to be unified under the flag of “moonshot thinking” by several visionary and transformative leaders to start believing in a miraculously better future for our patients. But to pave the way for moonshots in psychiatry, the leading organizations must collaborate closely to open the door for unprecedented scientific and medical breakthroughs of a moonshot by:

- Lobbying effectively to secure massive funding for research from federal, state, corporate, and foundation sources (perhaps convincing the Gates Foundation that schizophrenia is as devastating worldwide as malaria may bring a few badly needed billions into psychiatric brain research).

- Reminding members of Congress that in the United States, costs associated with psychiatric brain disorders total an estimated $700 billion annually,1 and that this must be addressed by boosting the meager NIMH budget by at least an order of magnitude. The NIMH should disproportionately invest its resources on severe brain disorders such as schizophrenia because breakthrough advances in its neurobiology will provide unprecedented insights to the pathophysiology of other severe psychiatric brain disorders.

- Partnering intimately with the pharmaceutical industry in a powerful public-private coalition to exploit the extensive research infrastructure of this industry.

- Creating the necessary army of researchers (physician-scientists) by providing huge incentives to medical students and psychiatric residents to pursue careers in neuroscience research. Incentives can include paying for an individual’s entire medical education and research training, and providing generous salaries that match or exceed the income of a very successful clinical practice.

- Convincing all psychiatric clinicians to support research by referring patients to research projects. Clinical psychiatrists are badly needed to care for the population, but they must be reminded that every treatment they are using today was a research project in the past, and that the research of today will evolve into the treatments (or cures) of tomorrow.

Pursuing lofty moonshots via innovative research is very likely to enhance serendipity and lead to unexpected discoveries along the way. As Louis Pasteur said, “chance only favors the prepared mind.”2 Moonshot thinking in psychiatry today is more feasible than ever before because of the many advances in research methods (neuroimaging, pluripotent cells, optogenetics, CRISPR, etc) and complex data management technologies (big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence), each of which qualifies as a preparatory moonshot in its own right.

Given the tragic consequences of psychiatric brain disorders, it is imperative that we “think big.” Humanity expects us to do that. We must envision the future of psychiatry as dramatically different from the present. Moonshot thinking is the indispensable vehicle to take us there.

1. Discovery Mood and Anxiety Program. The rising cost of mental health and substance abuse in the United States. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://discoverymood.com/blog/cost-of-mental-health-increase/

2. Wikiquote. Louis Pasteur. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Louis_Pasteur

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

President John F. Kennedy, May 25, 1961

Despite significant progress, there remain many unmet needs in psychiatry. These include a granular understanding of the neurobiology of various psychopathologies, an objective and valid diagnostic schema, and disease-modifying treatments for chronic and disabling psychiatric disorders. Several moonshots are needed to address those festering needs.

A “moonshot” is an extremely ambitious, dramatic, imaginative, and inspiring goal. Landing on the Moon was generally believed to be impossible when President Kennedy boldly set that as a goal for the United States in 1961. Yet, 8 short years later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped off the lunar module ladder onto the Moon’s surface, a feat that captured the imagination of the nation and the world. I distinctly remember watching it on television with amazement as a young boy. It was a surreal experience. That’s what achieving a moonshot feels like.

Successful organizations should always have 1 or more moonshots (American Psychiatric Association and National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], are you listening?). Setting lofty goals that require monumental determination and effort to accomplish will have a transformative, long-lasting impact. The construction of the Panama Canal to connect 2 oceans and the Manhattan Project to develop the first nuclear bomb, which ended World War II, are examples of moonshots that continue to reverberate. A more recent moonshot is the driverless car, which in the past was a laughable idea but is now a reality that will change society and the world in many ways. Innovative billionaire moguls now speak loudly about colonizing Mars, which sounds improbable and highly risky, but it’s a moonshot that may be achieved within a few years. Establishing world peace is a moonshot that requires collective Kennedy-esque vision and motivation among world leaders, which currently is sadly lacking.

So, for contemporary psychiatry, what is the equivalent of landing on the Moon? Here is the list that pops in my brain’s mind (let us know which of these would be your top 3 moonshots by taking our survey at https://bit.ly/3qkKqTa):

- A cure for schizophrenia (across positive, negative, and cognitive symptom domains)

- A cure for mood disorders, unipolar and bipolar (including suicide)

- A cure for anxiety disorders

- A cure for obsessive-compulsive disorder

- A cure for posttraumatic stress disorder

- A cure for alcoholism/addiction

- A cure for autism

- A cure for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

- A cure for personality disorders, especially antisocial and borderline

- A cure for the visceral hatred across political parties that permeates our society (obviously not a psychiatric category, but perhaps it should be added to DSM because it is so destructive).

Those moonshots may be regarded as absurd, and totally unachievable, but so was landing on the Moon, until it was accomplished. Psychiatry must stop thinking small and being content with tiny advances (which is like changing the chairs to more comfortable sofas on the deck of the Titanic and calling it “progress…”). Psychiatry needs to be unified under the flag of “moonshot thinking” by several visionary and transformative leaders to start believing in a miraculously better future for our patients. But to pave the way for moonshots in psychiatry, the leading organizations must collaborate closely to open the door for unprecedented scientific and medical breakthroughs of a moonshot by:

- Lobbying effectively to secure massive funding for research from federal, state, corporate, and foundation sources (perhaps convincing the Gates Foundation that schizophrenia is as devastating worldwide as malaria may bring a few badly needed billions into psychiatric brain research).

- Reminding members of Congress that in the United States, costs associated with psychiatric brain disorders total an estimated $700 billion annually,1 and that this must be addressed by boosting the meager NIMH budget by at least an order of magnitude. The NIMH should disproportionately invest its resources on severe brain disorders such as schizophrenia because breakthrough advances in its neurobiology will provide unprecedented insights to the pathophysiology of other severe psychiatric brain disorders.

- Partnering intimately with the pharmaceutical industry in a powerful public-private coalition to exploit the extensive research infrastructure of this industry.

- Creating the necessary army of researchers (physician-scientists) by providing huge incentives to medical students and psychiatric residents to pursue careers in neuroscience research. Incentives can include paying for an individual’s entire medical education and research training, and providing generous salaries that match or exceed the income of a very successful clinical practice.

- Convincing all psychiatric clinicians to support research by referring patients to research projects. Clinical psychiatrists are badly needed to care for the population, but they must be reminded that every treatment they are using today was a research project in the past, and that the research of today will evolve into the treatments (or cures) of tomorrow.

Pursuing lofty moonshots via innovative research is very likely to enhance serendipity and lead to unexpected discoveries along the way. As Louis Pasteur said, “chance only favors the prepared mind.”2 Moonshot thinking in psychiatry today is more feasible than ever before because of the many advances in research methods (neuroimaging, pluripotent cells, optogenetics, CRISPR, etc) and complex data management technologies (big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence), each of which qualifies as a preparatory moonshot in its own right.

Given the tragic consequences of psychiatric brain disorders, it is imperative that we “think big.” Humanity expects us to do that. We must envision the future of psychiatry as dramatically different from the present. Moonshot thinking is the indispensable vehicle to take us there.

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

President John F. Kennedy, May 25, 1961

Despite significant progress, there remain many unmet needs in psychiatry. These include a granular understanding of the neurobiology of various psychopathologies, an objective and valid diagnostic schema, and disease-modifying treatments for chronic and disabling psychiatric disorders. Several moonshots are needed to address those festering needs.

A “moonshot” is an extremely ambitious, dramatic, imaginative, and inspiring goal. Landing on the Moon was generally believed to be impossible when President Kennedy boldly set that as a goal for the United States in 1961. Yet, 8 short years later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped off the lunar module ladder onto the Moon’s surface, a feat that captured the imagination of the nation and the world. I distinctly remember watching it on television with amazement as a young boy. It was a surreal experience. That’s what achieving a moonshot feels like.

Successful organizations should always have 1 or more moonshots (American Psychiatric Association and National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], are you listening?). Setting lofty goals that require monumental determination and effort to accomplish will have a transformative, long-lasting impact. The construction of the Panama Canal to connect 2 oceans and the Manhattan Project to develop the first nuclear bomb, which ended World War II, are examples of moonshots that continue to reverberate. A more recent moonshot is the driverless car, which in the past was a laughable idea but is now a reality that will change society and the world in many ways. Innovative billionaire moguls now speak loudly about colonizing Mars, which sounds improbable and highly risky, but it’s a moonshot that may be achieved within a few years. Establishing world peace is a moonshot that requires collective Kennedy-esque vision and motivation among world leaders, which currently is sadly lacking.

So, for contemporary psychiatry, what is the equivalent of landing on the Moon? Here is the list that pops in my brain’s mind (let us know which of these would be your top 3 moonshots by taking our survey at https://bit.ly/3qkKqTa):

- A cure for schizophrenia (across positive, negative, and cognitive symptom domains)

- A cure for mood disorders, unipolar and bipolar (including suicide)

- A cure for anxiety disorders

- A cure for obsessive-compulsive disorder

- A cure for posttraumatic stress disorder

- A cure for alcoholism/addiction

- A cure for autism

- A cure for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

- A cure for personality disorders, especially antisocial and borderline

- A cure for the visceral hatred across political parties that permeates our society (obviously not a psychiatric category, but perhaps it should be added to DSM because it is so destructive).

Those moonshots may be regarded as absurd, and totally unachievable, but so was landing on the Moon, until it was accomplished. Psychiatry must stop thinking small and being content with tiny advances (which is like changing the chairs to more comfortable sofas on the deck of the Titanic and calling it “progress…”). Psychiatry needs to be unified under the flag of “moonshot thinking” by several visionary and transformative leaders to start believing in a miraculously better future for our patients. But to pave the way for moonshots in psychiatry, the leading organizations must collaborate closely to open the door for unprecedented scientific and medical breakthroughs of a moonshot by:

- Lobbying effectively to secure massive funding for research from federal, state, corporate, and foundation sources (perhaps convincing the Gates Foundation that schizophrenia is as devastating worldwide as malaria may bring a few badly needed billions into psychiatric brain research).

- Reminding members of Congress that in the United States, costs associated with psychiatric brain disorders total an estimated $700 billion annually,1 and that this must be addressed by boosting the meager NIMH budget by at least an order of magnitude. The NIMH should disproportionately invest its resources on severe brain disorders such as schizophrenia because breakthrough advances in its neurobiology will provide unprecedented insights to the pathophysiology of other severe psychiatric brain disorders.

- Partnering intimately with the pharmaceutical industry in a powerful public-private coalition to exploit the extensive research infrastructure of this industry.

- Creating the necessary army of researchers (physician-scientists) by providing huge incentives to medical students and psychiatric residents to pursue careers in neuroscience research. Incentives can include paying for an individual’s entire medical education and research training, and providing generous salaries that match or exceed the income of a very successful clinical practice.

- Convincing all psychiatric clinicians to support research by referring patients to research projects. Clinical psychiatrists are badly needed to care for the population, but they must be reminded that every treatment they are using today was a research project in the past, and that the research of today will evolve into the treatments (or cures) of tomorrow.

Pursuing lofty moonshots via innovative research is very likely to enhance serendipity and lead to unexpected discoveries along the way. As Louis Pasteur said, “chance only favors the prepared mind.”2 Moonshot thinking in psychiatry today is more feasible than ever before because of the many advances in research methods (neuroimaging, pluripotent cells, optogenetics, CRISPR, etc) and complex data management technologies (big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence), each of which qualifies as a preparatory moonshot in its own right.

Given the tragic consequences of psychiatric brain disorders, it is imperative that we “think big.” Humanity expects us to do that. We must envision the future of psychiatry as dramatically different from the present. Moonshot thinking is the indispensable vehicle to take us there.

1. Discovery Mood and Anxiety Program. The rising cost of mental health and substance abuse in the United States. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://discoverymood.com/blog/cost-of-mental-health-increase/

2. Wikiquote. Louis Pasteur. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Louis_Pasteur

1. Discovery Mood and Anxiety Program. The rising cost of mental health and substance abuse in the United States. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://discoverymood.com/blog/cost-of-mental-health-increase/

2. Wikiquote. Louis Pasteur. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Louis_Pasteur

Honor thy parents? Understanding parricide and associated spree killings

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

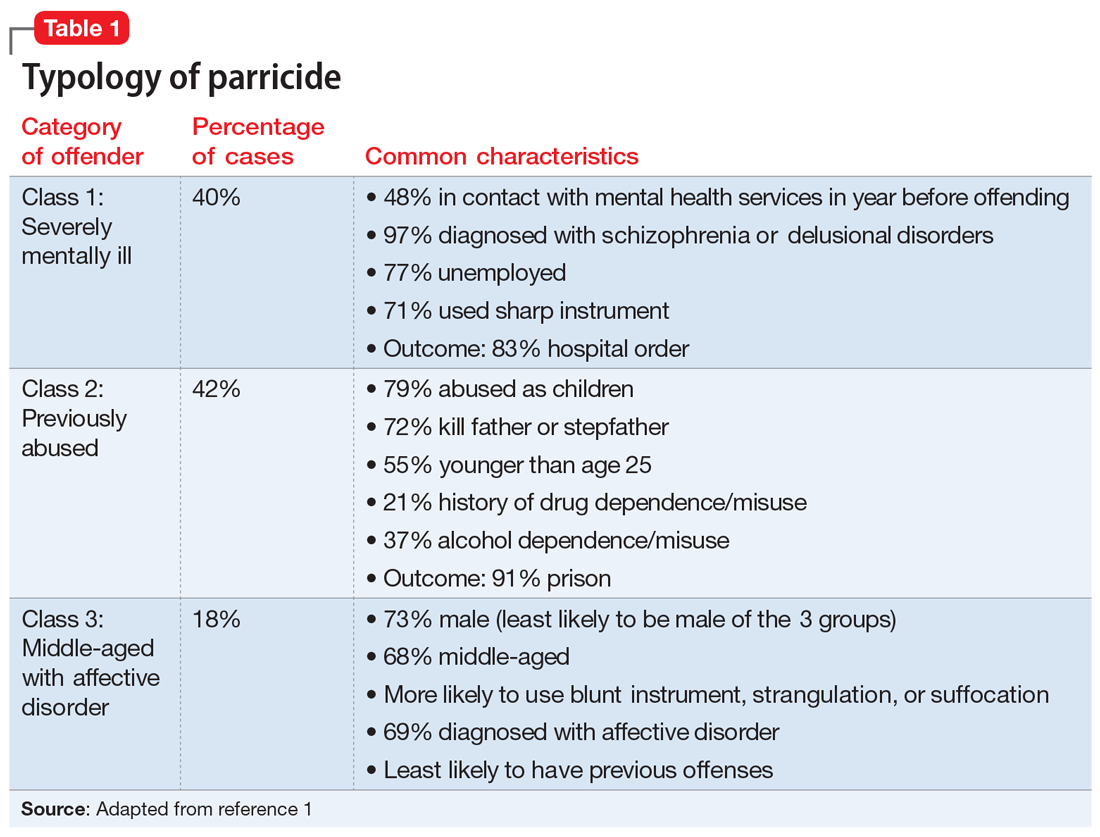

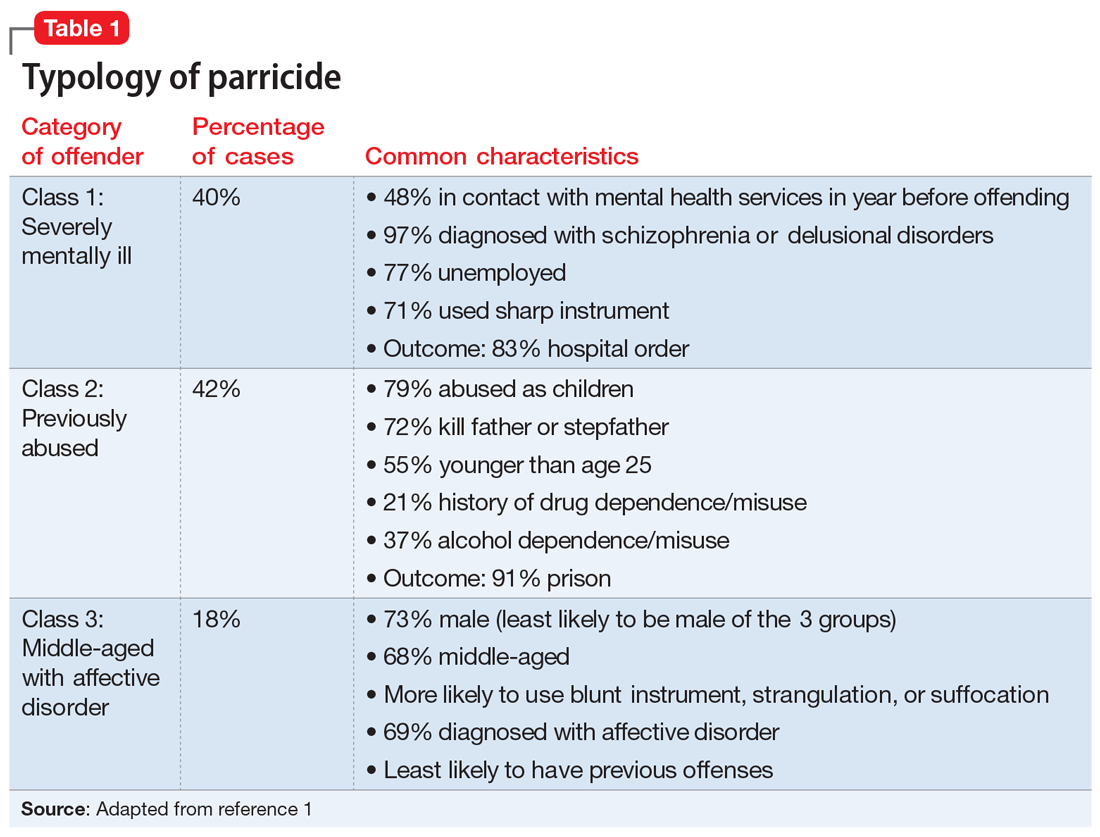

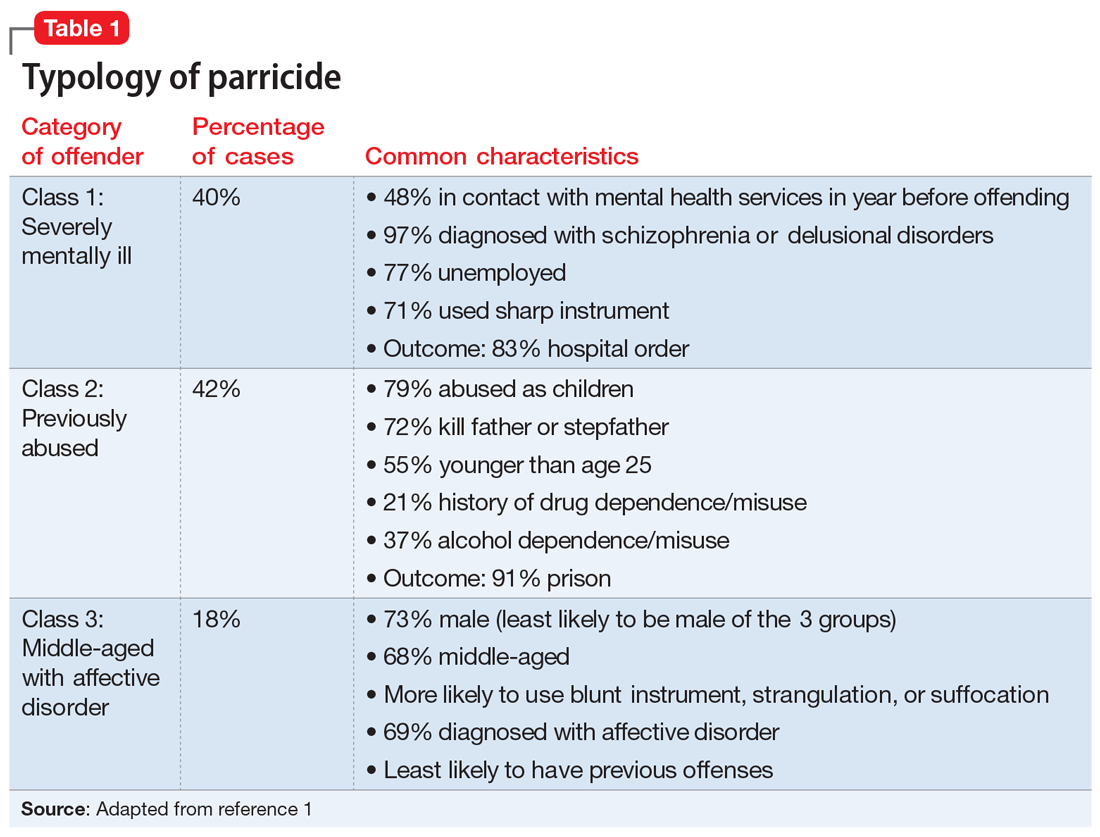

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

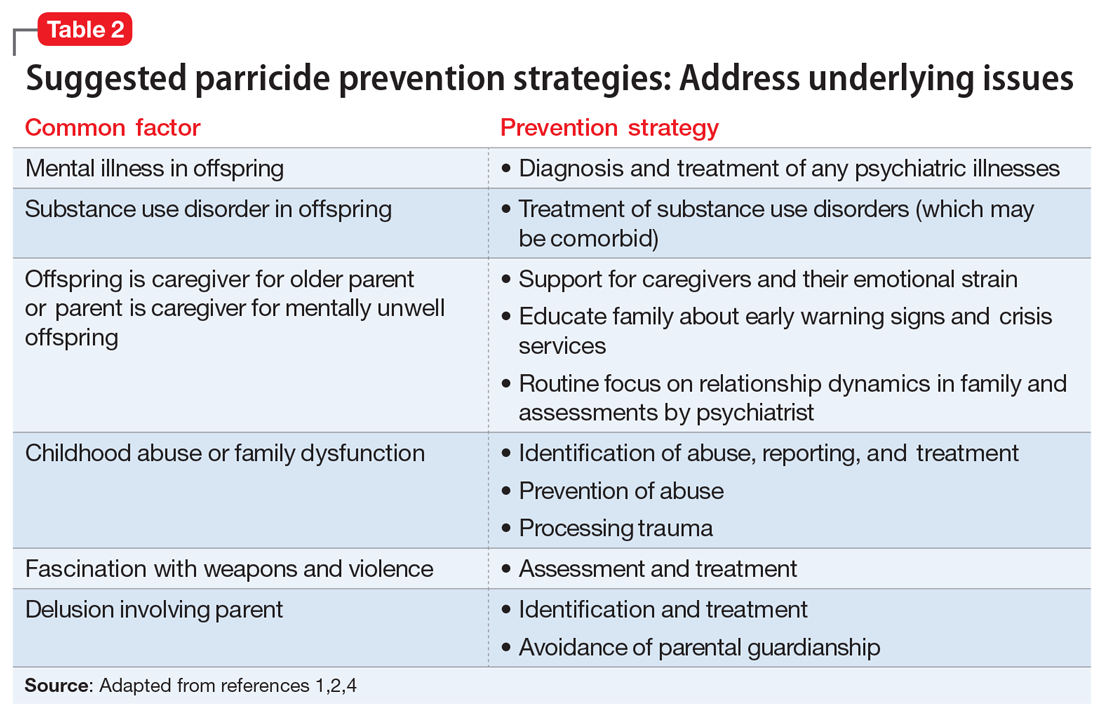

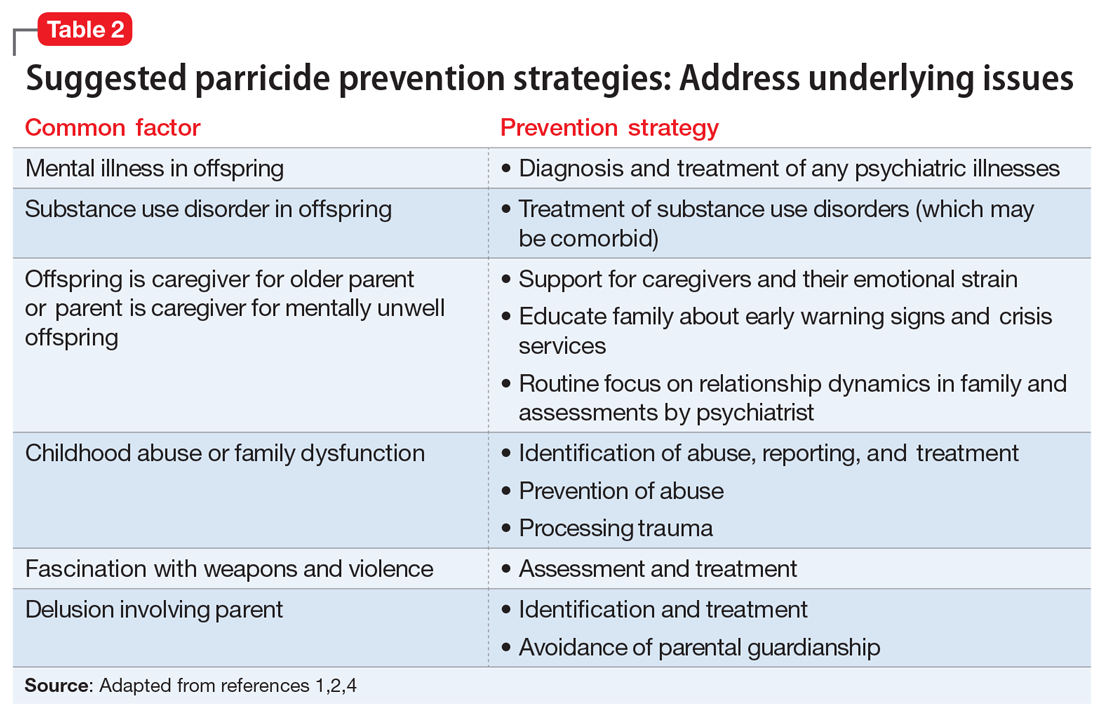

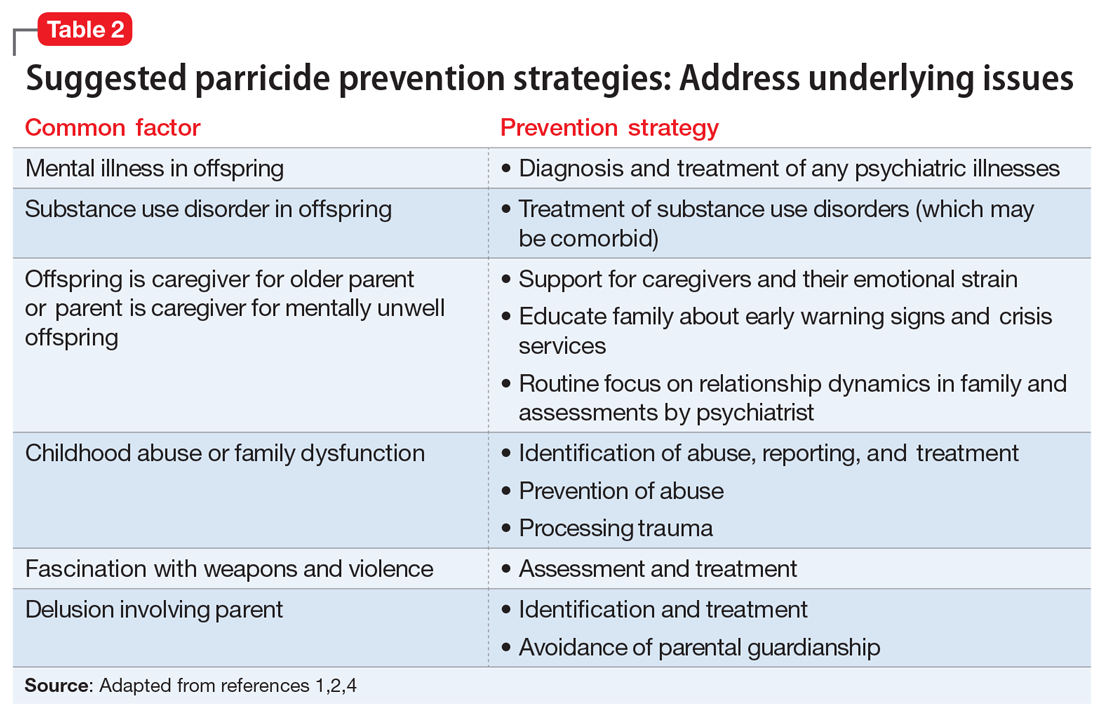

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

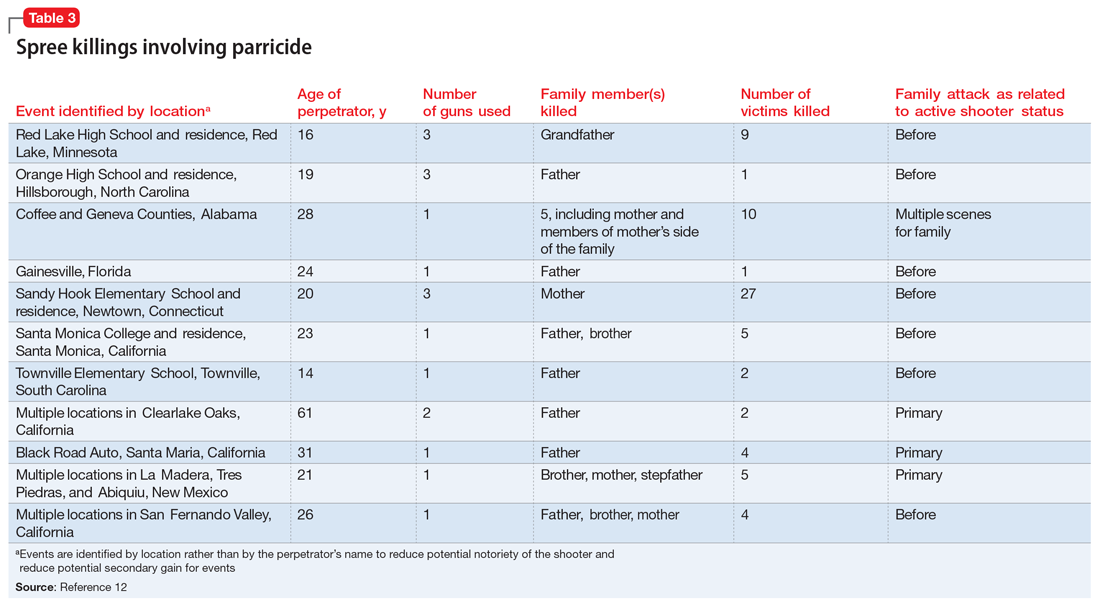

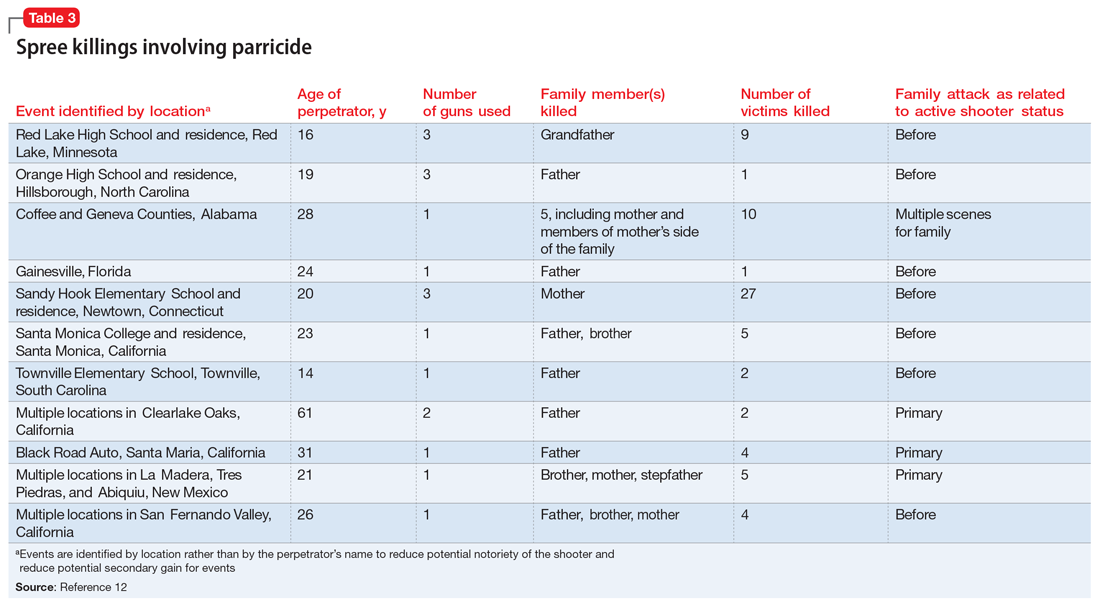

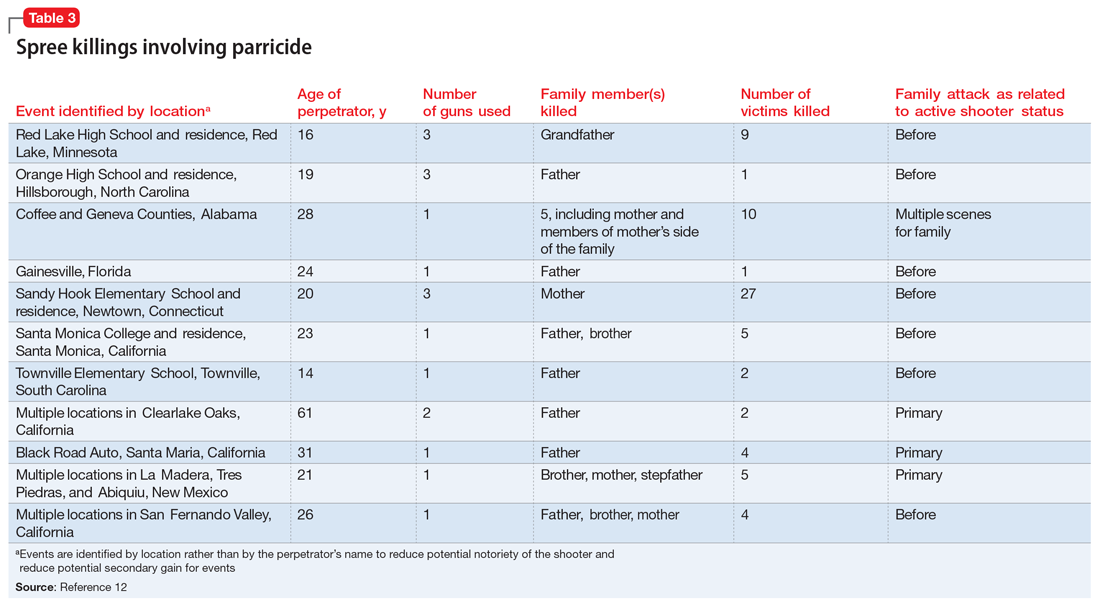

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).