User login

Nonhormonal medication treatment of VMS

VMS, also known as hot flashes, night sweats, or cold sweats, occur for the majority of perimenopausal and menopausal women.1 In one study, the mean duration of clinically significant VMS was 5 years, and one-third of participants continued to have bothersome hot flashes 10 or more years after the onset of menopause.2 VMS may contribute to disrupted sleep patterns and depressed mood.3

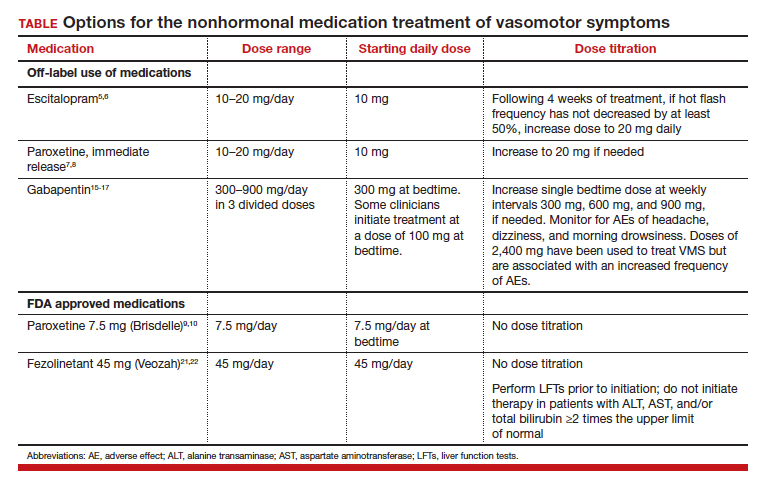

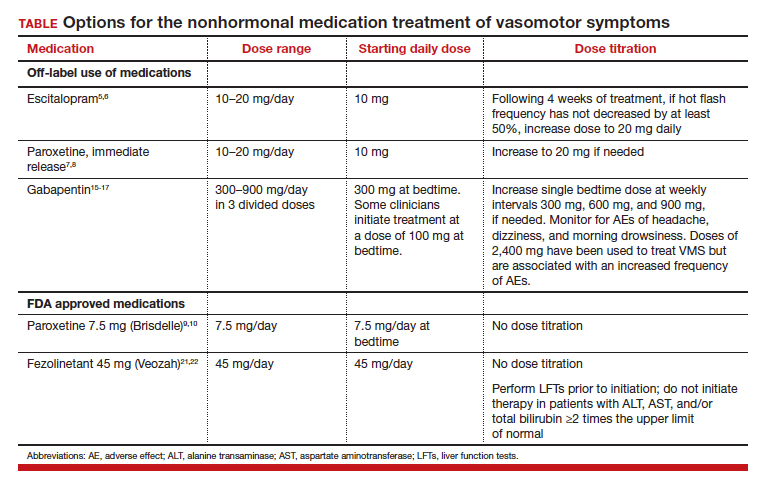

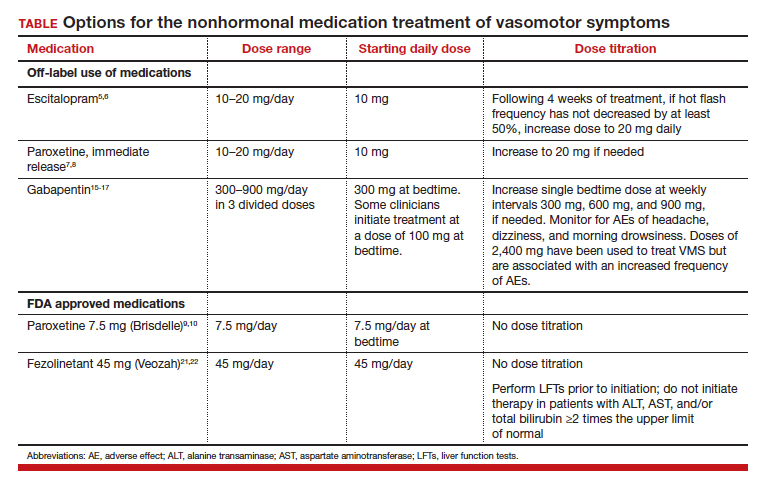

All obstetrician-gynecologists know that estradiol and other estrogens are highly effective in the treatment of bothersome VMS. A meta-analysis reported that the frequency of VMS was reduced by 60% to 80% with oral estradiol (1 mg/day), transdermal estradiol(0.05 mg/day), and conjugated estrogen (0.625 mg).4 Breast tenderness and irregular uterine bleeding are common side effects of estrogen treatment of VMS. Estrogen treatment is contraindicated in patients with estrogen-responsive cancers, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and some cases of inherited thrombophilia. For these patients, an important option is the nonhormonal treatment of VMS, and several nonhormonal medications have been demonstrated to be effective therapy (TABLE 1). In this editorial I will review the medication treatment of VMS with escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant.

Escitalopram and paroxetine

Escitalopram and paroxetine have been shown to reduce VMS more than placebo in multiple clinical trials.5-10 In addition, escitalopram and paroxetine, at the doses tested, may be more effective for the treatment of VMS than sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.11 In one trial assessing the efficacy of escitalopram to treat VMS, 205 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo or escitalopram.5 The initial escitalopram dose was 10 mg daily. At week 4:

- if VMS frequency was reduced by ≥ 50%, the patient remained on the 10-mg dose

- if VMS frequency was reduced by < 50%, the escitalopram dose was increased to 20 mg daily.

Following 8 weeks of treatment, the frequency of VMS decreased for patients in the placebo and escitalopram groups by 33% and 47%, respectively. Similar results have been reported in other studies.6

Paroxetine at a dose of 7.5 mg/day administered at bedtime is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of VMS. In a pivotal study, 1,112 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or paroxetine 7.5 mg at bedtime.9 In the 12-week study the reported decrease in mean weekly frequency of VMS for patients in the placebo and paroxetine groups were -37 and -44, respectively.9 Paroxetine 7.5 mg also reduced awakenings per night attributed to VMS and increased nighttime sleep duration.10

Depressed mood is prevalent among perimenopausal and postmenopausal patients.12 Prescribing escitalopram or paroxetine for VMS also may improve mood. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are effective for the treatment of VMS;13,14 however, I seldom prescribe these medications for VMS because in my experience they are associated with more bothersome side effects, including dry mouth, decreased appetite, nausea, and insomnia than escitalopram or low-dose paroxetine.

Gabapentin

Numerous randomized clinical trials have reported that gabapentin is superior to placebo for the treatment of VMS.15 In one trial, 420 patients with breast cancer and VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo, gabapentin 300 mg/day (G300), or gabapentin 900 mg/day (G900) in 3 divided doses.16 Following 8 weeks of treatment, reduction in hot-flash severity score among patients receiving placebo, G300, or G900 was 15%, 31%, and 46%, respectively. Fatigue and somnolence were reported more frequently among patients taking gabapentin 900 mg/day. In a small trial, 60 patients with VMS were randomized to receive placebo, conjugated estrogen (0.2625 mg/day),or gabapentin (target dose of 2,400 mg/day in 3 divided doses).17 Following 12 weeks of treatment, the patient-reported decrease in VMS for those taking placebo, estrogen, or gabapentin was 54%, 72%, and 71%, respectively.

High-dose gabapentin treatment was associated with side effects of headache and dizziness more often than placebo or estrogen. Although gabapentin is not a treatment for insomnia, in my practice if a menopausal patient has prominent and bothersome symptoms of sleep disturbance and mild VMS symptoms, I will consider a trial of low-dose gabapentin. Some experts recommend initiating gabapentin at a dose of 100 mgdaily before bedtime to assess the effectiveness of a low dose that seldom causes significant side effects.

Fezolinetant

In a study of genetic variation associated with VMS, investigators discovered that nucleic acid variation in the neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor was strongly associated with the prevalence of VMS, suggesting that this receptor is in the causal pathway to menopausal VMS.18 Additional research demonstrated that the kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons, which are involved in the control of hypothalamic thermoregulation, are stimulated by neurokinin B, acting through the NK3 receptor, and suppressed by estradiol. A reduction in hypothalamic estrogen results in unopposed neurokinin B activity, which stimulates KNDy neurons, destabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, causing vasodilation, which is perceived as hot flashes and sweating followed by chills.19

Fezolinetant is a high-affinity NK3 receptor antagonist that blocks the activity of neurokinin B, stabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, thereby suppressing hot flashes. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe VMS due to menopause using a fixed dose of 45 mg daily.20 In one clinical trial, 500 menopausal patients with bothersome VMS were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo, fezolinetant 30 mg/day, or fezolinetant 45 mg/day. Following 12 weeks of treatment, the reported frequency rates of VMS among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 43%, 61%, and 64%, respectively.21 In addition, following 12 weeks of treatment, the severity of VMS rates among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 20%, 26%, and 32%, respectively.

Fezolinetant improved the quality of sleep and was associated with an improvement in patient-reported quality of life. Following 12 weeks of treatment, sleep quality among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups was reported to be “much or moderately better” in 34%, 45%, and 54% of the patients, respectively.21 Similar results were reported in a companion study.22

Fezolinetant is contraindicated for patients with liver cirrhosis or severe renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Before initiating treatment, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin (total and direct). Fezolinetant should not be prescribed if any of these tests are greater than twice the upper limit of normal. These tests should be repeated at 3, 6, and 9 months, and if the patient reports symptoms or signs of liver injury (nausea, vomiting, jaundice). Fezolinetant is metabolized by CYP1A2 and should not be prescribed to patients taking strong CYP1A2 inhibitors. The most common side effects associated with fezolinetant treatment are abdominal pain (4.3%), diarrhea (3.9%), insomnia (3.9%), back pain (3.0%), and hepatic transaminase elevation (2.3%). Fezolinetant has not been thoroughly evaluated in patients older than age 65. Following an oral dose of the medication, the median maximum concentration is reached in 1.5 hours, and the half-life is estimated to be 10 hours.20 Of all the medications discussed in this editorial, fezolinetant is the most expensive.

Effective VMS treatment improves overall health

Estrogen therapy is the gold standard treatment of VMS. However, many menopausal patients with bothersome VMS prefer not to take estrogen, and some have a medical condition that is a contraindication to estrogen treatment. The nonhormonal medication options for the treatment of VMS include escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant. Patients value the ability to choose the treatment they prefer, among all available hormonal and nonhormonal medication options. For mid-life women, effectively treating bothersome VMS is only one of many interventions that improves health. Optimal health is best achieved with23:

- high-quality diet

- daily physical activity

- appropriate body mass index

- nicotine avoidance

- a healthy sleep schedule

- normal blood pressure, lipid, and glucose levels.

Women who have a high-quality diet; daily physical activity; an appropriate body mass index; and normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels are estimated to live 9 disease-free years longer than other women.24 ●

- Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopause transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Pub Health. 2006;1226-1235.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause. 2014;21:924-932.

- Hatcher KM, Smith RL, Chiang C, et al. Nocturnal hot flashes, but not serum hormone concentrations as a predictor of insomnia in menopausal women: results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Women’s Health. 2023;32:94-101.

- Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610.

- Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:267-227.

- Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, et al. Effect of escitalopram on hot flash interference: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1399-1404.e1.

- Slaton RM, Champion MN, Palmore KB. A review of paroxetine for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. J Pharm Pract. 2015;28:266-274.

- Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6919-6930.

- Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Lowdose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20:1027-1035.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, et al. Lowdose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause. 2015;22:50-58.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:204-213.

- Freeman EW. Depression in the menopause transition: risks in the changing hormone milieu as observed in the general population. Womens Midlife Health. 2015;1:2.

- Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059-2063.

- Sun Z, Hao Y, Zhang M. Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:255-262.

- Toulis KA, Tzellos T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

- Pandya KJ, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: a randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:818-824.

- Reddy SY, Warner H, Guttuso T Jr, et al. Gabapentin, estrogen, and placebo for treating hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:41-48.

- Crandall CJ, Manson JE, Hohensee C, et al. Association of genetic variation in the tachykinin receptor 3 locus with hot flashes and night sweats in the Women’s Health Initiative Study. Menopause. 2017;24:252.

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neurendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227.

- Veozah (package insert). Astellas Pharma; Northbrook, Illinois. May 2023.

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a Phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1981-1997.

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18-43.

- Wang X, Ma H, Li X, et al. Association of cardiovascular health with life expectancy free of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia in U.K. adults. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:340-349.

VMS, also known as hot flashes, night sweats, or cold sweats, occur for the majority of perimenopausal and menopausal women.1 In one study, the mean duration of clinically significant VMS was 5 years, and one-third of participants continued to have bothersome hot flashes 10 or more years after the onset of menopause.2 VMS may contribute to disrupted sleep patterns and depressed mood.3

All obstetrician-gynecologists know that estradiol and other estrogens are highly effective in the treatment of bothersome VMS. A meta-analysis reported that the frequency of VMS was reduced by 60% to 80% with oral estradiol (1 mg/day), transdermal estradiol(0.05 mg/day), and conjugated estrogen (0.625 mg).4 Breast tenderness and irregular uterine bleeding are common side effects of estrogen treatment of VMS. Estrogen treatment is contraindicated in patients with estrogen-responsive cancers, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and some cases of inherited thrombophilia. For these patients, an important option is the nonhormonal treatment of VMS, and several nonhormonal medications have been demonstrated to be effective therapy (TABLE 1). In this editorial I will review the medication treatment of VMS with escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant.

Escitalopram and paroxetine

Escitalopram and paroxetine have been shown to reduce VMS more than placebo in multiple clinical trials.5-10 In addition, escitalopram and paroxetine, at the doses tested, may be more effective for the treatment of VMS than sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.11 In one trial assessing the efficacy of escitalopram to treat VMS, 205 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo or escitalopram.5 The initial escitalopram dose was 10 mg daily. At week 4:

- if VMS frequency was reduced by ≥ 50%, the patient remained on the 10-mg dose

- if VMS frequency was reduced by < 50%, the escitalopram dose was increased to 20 mg daily.

Following 8 weeks of treatment, the frequency of VMS decreased for patients in the placebo and escitalopram groups by 33% and 47%, respectively. Similar results have been reported in other studies.6

Paroxetine at a dose of 7.5 mg/day administered at bedtime is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of VMS. In a pivotal study, 1,112 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or paroxetine 7.5 mg at bedtime.9 In the 12-week study the reported decrease in mean weekly frequency of VMS for patients in the placebo and paroxetine groups were -37 and -44, respectively.9 Paroxetine 7.5 mg also reduced awakenings per night attributed to VMS and increased nighttime sleep duration.10

Depressed mood is prevalent among perimenopausal and postmenopausal patients.12 Prescribing escitalopram or paroxetine for VMS also may improve mood. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are effective for the treatment of VMS;13,14 however, I seldom prescribe these medications for VMS because in my experience they are associated with more bothersome side effects, including dry mouth, decreased appetite, nausea, and insomnia than escitalopram or low-dose paroxetine.

Gabapentin

Numerous randomized clinical trials have reported that gabapentin is superior to placebo for the treatment of VMS.15 In one trial, 420 patients with breast cancer and VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo, gabapentin 300 mg/day (G300), or gabapentin 900 mg/day (G900) in 3 divided doses.16 Following 8 weeks of treatment, reduction in hot-flash severity score among patients receiving placebo, G300, or G900 was 15%, 31%, and 46%, respectively. Fatigue and somnolence were reported more frequently among patients taking gabapentin 900 mg/day. In a small trial, 60 patients with VMS were randomized to receive placebo, conjugated estrogen (0.2625 mg/day),or gabapentin (target dose of 2,400 mg/day in 3 divided doses).17 Following 12 weeks of treatment, the patient-reported decrease in VMS for those taking placebo, estrogen, or gabapentin was 54%, 72%, and 71%, respectively.

High-dose gabapentin treatment was associated with side effects of headache and dizziness more often than placebo or estrogen. Although gabapentin is not a treatment for insomnia, in my practice if a menopausal patient has prominent and bothersome symptoms of sleep disturbance and mild VMS symptoms, I will consider a trial of low-dose gabapentin. Some experts recommend initiating gabapentin at a dose of 100 mgdaily before bedtime to assess the effectiveness of a low dose that seldom causes significant side effects.

Fezolinetant

In a study of genetic variation associated with VMS, investigators discovered that nucleic acid variation in the neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor was strongly associated with the prevalence of VMS, suggesting that this receptor is in the causal pathway to menopausal VMS.18 Additional research demonstrated that the kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons, which are involved in the control of hypothalamic thermoregulation, are stimulated by neurokinin B, acting through the NK3 receptor, and suppressed by estradiol. A reduction in hypothalamic estrogen results in unopposed neurokinin B activity, which stimulates KNDy neurons, destabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, causing vasodilation, which is perceived as hot flashes and sweating followed by chills.19

Fezolinetant is a high-affinity NK3 receptor antagonist that blocks the activity of neurokinin B, stabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, thereby suppressing hot flashes. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe VMS due to menopause using a fixed dose of 45 mg daily.20 In one clinical trial, 500 menopausal patients with bothersome VMS were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo, fezolinetant 30 mg/day, or fezolinetant 45 mg/day. Following 12 weeks of treatment, the reported frequency rates of VMS among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 43%, 61%, and 64%, respectively.21 In addition, following 12 weeks of treatment, the severity of VMS rates among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 20%, 26%, and 32%, respectively.

Fezolinetant improved the quality of sleep and was associated with an improvement in patient-reported quality of life. Following 12 weeks of treatment, sleep quality among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups was reported to be “much or moderately better” in 34%, 45%, and 54% of the patients, respectively.21 Similar results were reported in a companion study.22

Fezolinetant is contraindicated for patients with liver cirrhosis or severe renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Before initiating treatment, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin (total and direct). Fezolinetant should not be prescribed if any of these tests are greater than twice the upper limit of normal. These tests should be repeated at 3, 6, and 9 months, and if the patient reports symptoms or signs of liver injury (nausea, vomiting, jaundice). Fezolinetant is metabolized by CYP1A2 and should not be prescribed to patients taking strong CYP1A2 inhibitors. The most common side effects associated with fezolinetant treatment are abdominal pain (4.3%), diarrhea (3.9%), insomnia (3.9%), back pain (3.0%), and hepatic transaminase elevation (2.3%). Fezolinetant has not been thoroughly evaluated in patients older than age 65. Following an oral dose of the medication, the median maximum concentration is reached in 1.5 hours, and the half-life is estimated to be 10 hours.20 Of all the medications discussed in this editorial, fezolinetant is the most expensive.

Effective VMS treatment improves overall health

Estrogen therapy is the gold standard treatment of VMS. However, many menopausal patients with bothersome VMS prefer not to take estrogen, and some have a medical condition that is a contraindication to estrogen treatment. The nonhormonal medication options for the treatment of VMS include escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant. Patients value the ability to choose the treatment they prefer, among all available hormonal and nonhormonal medication options. For mid-life women, effectively treating bothersome VMS is only one of many interventions that improves health. Optimal health is best achieved with23:

- high-quality diet

- daily physical activity

- appropriate body mass index

- nicotine avoidance

- a healthy sleep schedule

- normal blood pressure, lipid, and glucose levels.

Women who have a high-quality diet; daily physical activity; an appropriate body mass index; and normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels are estimated to live 9 disease-free years longer than other women.24 ●

VMS, also known as hot flashes, night sweats, or cold sweats, occur for the majority of perimenopausal and menopausal women.1 In one study, the mean duration of clinically significant VMS was 5 years, and one-third of participants continued to have bothersome hot flashes 10 or more years after the onset of menopause.2 VMS may contribute to disrupted sleep patterns and depressed mood.3

All obstetrician-gynecologists know that estradiol and other estrogens are highly effective in the treatment of bothersome VMS. A meta-analysis reported that the frequency of VMS was reduced by 60% to 80% with oral estradiol (1 mg/day), transdermal estradiol(0.05 mg/day), and conjugated estrogen (0.625 mg).4 Breast tenderness and irregular uterine bleeding are common side effects of estrogen treatment of VMS. Estrogen treatment is contraindicated in patients with estrogen-responsive cancers, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and some cases of inherited thrombophilia. For these patients, an important option is the nonhormonal treatment of VMS, and several nonhormonal medications have been demonstrated to be effective therapy (TABLE 1). In this editorial I will review the medication treatment of VMS with escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant.

Escitalopram and paroxetine

Escitalopram and paroxetine have been shown to reduce VMS more than placebo in multiple clinical trials.5-10 In addition, escitalopram and paroxetine, at the doses tested, may be more effective for the treatment of VMS than sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.11 In one trial assessing the efficacy of escitalopram to treat VMS, 205 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo or escitalopram.5 The initial escitalopram dose was 10 mg daily. At week 4:

- if VMS frequency was reduced by ≥ 50%, the patient remained on the 10-mg dose

- if VMS frequency was reduced by < 50%, the escitalopram dose was increased to 20 mg daily.

Following 8 weeks of treatment, the frequency of VMS decreased for patients in the placebo and escitalopram groups by 33% and 47%, respectively. Similar results have been reported in other studies.6

Paroxetine at a dose of 7.5 mg/day administered at bedtime is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of VMS. In a pivotal study, 1,112 patients with VMS were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or paroxetine 7.5 mg at bedtime.9 In the 12-week study the reported decrease in mean weekly frequency of VMS for patients in the placebo and paroxetine groups were -37 and -44, respectively.9 Paroxetine 7.5 mg also reduced awakenings per night attributed to VMS and increased nighttime sleep duration.10

Depressed mood is prevalent among perimenopausal and postmenopausal patients.12 Prescribing escitalopram or paroxetine for VMS also may improve mood. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are effective for the treatment of VMS;13,14 however, I seldom prescribe these medications for VMS because in my experience they are associated with more bothersome side effects, including dry mouth, decreased appetite, nausea, and insomnia than escitalopram or low-dose paroxetine.

Gabapentin

Numerous randomized clinical trials have reported that gabapentin is superior to placebo for the treatment of VMS.15 In one trial, 420 patients with breast cancer and VMS were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with placebo, gabapentin 300 mg/day (G300), or gabapentin 900 mg/day (G900) in 3 divided doses.16 Following 8 weeks of treatment, reduction in hot-flash severity score among patients receiving placebo, G300, or G900 was 15%, 31%, and 46%, respectively. Fatigue and somnolence were reported more frequently among patients taking gabapentin 900 mg/day. In a small trial, 60 patients with VMS were randomized to receive placebo, conjugated estrogen (0.2625 mg/day),or gabapentin (target dose of 2,400 mg/day in 3 divided doses).17 Following 12 weeks of treatment, the patient-reported decrease in VMS for those taking placebo, estrogen, or gabapentin was 54%, 72%, and 71%, respectively.

High-dose gabapentin treatment was associated with side effects of headache and dizziness more often than placebo or estrogen. Although gabapentin is not a treatment for insomnia, in my practice if a menopausal patient has prominent and bothersome symptoms of sleep disturbance and mild VMS symptoms, I will consider a trial of low-dose gabapentin. Some experts recommend initiating gabapentin at a dose of 100 mgdaily before bedtime to assess the effectiveness of a low dose that seldom causes significant side effects.

Fezolinetant

In a study of genetic variation associated with VMS, investigators discovered that nucleic acid variation in the neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor was strongly associated with the prevalence of VMS, suggesting that this receptor is in the causal pathway to menopausal VMS.18 Additional research demonstrated that the kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons, which are involved in the control of hypothalamic thermoregulation, are stimulated by neurokinin B, acting through the NK3 receptor, and suppressed by estradiol. A reduction in hypothalamic estrogen results in unopposed neurokinin B activity, which stimulates KNDy neurons, destabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, causing vasodilation, which is perceived as hot flashes and sweating followed by chills.19

Fezolinetant is a high-affinity NK3 receptor antagonist that blocks the activity of neurokinin B, stabilizing the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, thereby suppressing hot flashes. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe VMS due to menopause using a fixed dose of 45 mg daily.20 In one clinical trial, 500 menopausal patients with bothersome VMS were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo, fezolinetant 30 mg/day, or fezolinetant 45 mg/day. Following 12 weeks of treatment, the reported frequency rates of VMS among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 43%, 61%, and 64%, respectively.21 In addition, following 12 weeks of treatment, the severity of VMS rates among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups were reduced by 20%, 26%, and 32%, respectively.

Fezolinetant improved the quality of sleep and was associated with an improvement in patient-reported quality of life. Following 12 weeks of treatment, sleep quality among patients in the placebo, F30, and F45 groups was reported to be “much or moderately better” in 34%, 45%, and 54% of the patients, respectively.21 Similar results were reported in a companion study.22

Fezolinetant is contraindicated for patients with liver cirrhosis or severe renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Before initiating treatment, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin (total and direct). Fezolinetant should not be prescribed if any of these tests are greater than twice the upper limit of normal. These tests should be repeated at 3, 6, and 9 months, and if the patient reports symptoms or signs of liver injury (nausea, vomiting, jaundice). Fezolinetant is metabolized by CYP1A2 and should not be prescribed to patients taking strong CYP1A2 inhibitors. The most common side effects associated with fezolinetant treatment are abdominal pain (4.3%), diarrhea (3.9%), insomnia (3.9%), back pain (3.0%), and hepatic transaminase elevation (2.3%). Fezolinetant has not been thoroughly evaluated in patients older than age 65. Following an oral dose of the medication, the median maximum concentration is reached in 1.5 hours, and the half-life is estimated to be 10 hours.20 Of all the medications discussed in this editorial, fezolinetant is the most expensive.

Effective VMS treatment improves overall health

Estrogen therapy is the gold standard treatment of VMS. However, many menopausal patients with bothersome VMS prefer not to take estrogen, and some have a medical condition that is a contraindication to estrogen treatment. The nonhormonal medication options for the treatment of VMS include escitalopram, paroxetine, gabapentin, and fezolinetant. Patients value the ability to choose the treatment they prefer, among all available hormonal and nonhormonal medication options. For mid-life women, effectively treating bothersome VMS is only one of many interventions that improves health. Optimal health is best achieved with23:

- high-quality diet

- daily physical activity

- appropriate body mass index

- nicotine avoidance

- a healthy sleep schedule

- normal blood pressure, lipid, and glucose levels.

Women who have a high-quality diet; daily physical activity; an appropriate body mass index; and normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels are estimated to live 9 disease-free years longer than other women.24 ●

- Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopause transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Pub Health. 2006;1226-1235.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause. 2014;21:924-932.

- Hatcher KM, Smith RL, Chiang C, et al. Nocturnal hot flashes, but not serum hormone concentrations as a predictor of insomnia in menopausal women: results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Women’s Health. 2023;32:94-101.

- Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610.

- Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:267-227.

- Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, et al. Effect of escitalopram on hot flash interference: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1399-1404.e1.

- Slaton RM, Champion MN, Palmore KB. A review of paroxetine for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. J Pharm Pract. 2015;28:266-274.

- Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6919-6930.

- Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Lowdose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20:1027-1035.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, et al. Lowdose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause. 2015;22:50-58.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:204-213.

- Freeman EW. Depression in the menopause transition: risks in the changing hormone milieu as observed in the general population. Womens Midlife Health. 2015;1:2.

- Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059-2063.

- Sun Z, Hao Y, Zhang M. Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:255-262.

- Toulis KA, Tzellos T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

- Pandya KJ, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: a randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:818-824.

- Reddy SY, Warner H, Guttuso T Jr, et al. Gabapentin, estrogen, and placebo for treating hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:41-48.

- Crandall CJ, Manson JE, Hohensee C, et al. Association of genetic variation in the tachykinin receptor 3 locus with hot flashes and night sweats in the Women’s Health Initiative Study. Menopause. 2017;24:252.

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neurendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227.

- Veozah (package insert). Astellas Pharma; Northbrook, Illinois. May 2023.

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a Phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1981-1997.

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18-43.

- Wang X, Ma H, Li X, et al. Association of cardiovascular health with life expectancy free of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia in U.K. adults. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:340-349.

- Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopause transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Pub Health. 2006;1226-1235.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Sanders RJ. Risk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohort. Menopause. 2014;21:924-932.

- Hatcher KM, Smith RL, Chiang C, et al. Nocturnal hot flashes, but not serum hormone concentrations as a predictor of insomnia in menopausal women: results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Women’s Health. 2023;32:94-101.

- Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610.

- Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:267-227.

- Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, et al. Effect of escitalopram on hot flash interference: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1399-1404.e1.

- Slaton RM, Champion MN, Palmore KB. A review of paroxetine for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. J Pharm Pract. 2015;28:266-274.

- Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6919-6930.

- Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Lowdose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20:1027-1035.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, et al. Lowdose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause. 2015;22:50-58.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:204-213.

- Freeman EW. Depression in the menopause transition: risks in the changing hormone milieu as observed in the general population. Womens Midlife Health. 2015;1:2.

- Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059-2063.

- Sun Z, Hao Y, Zhang M. Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:255-262.

- Toulis KA, Tzellos T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

- Pandya KJ, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: a randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:818-824.

- Reddy SY, Warner H, Guttuso T Jr, et al. Gabapentin, estrogen, and placebo for treating hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:41-48.

- Crandall CJ, Manson JE, Hohensee C, et al. Association of genetic variation in the tachykinin receptor 3 locus with hot flashes and night sweats in the Women’s Health Initiative Study. Menopause. 2017;24:252.

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neurendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227.

- Veozah (package insert). Astellas Pharma; Northbrook, Illinois. May 2023.

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a Phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1981-1997.

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18-43.

- Wang X, Ma H, Li X, et al. Association of cardiovascular health with life expectancy free of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia in U.K. adults. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:340-349.

Hormone therapy less effective in menopausal women with obesity

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).

The proportions of women reporting relief from only lifestyle modifications or from nonhormonal medications, such as SSRIs/SNRIs, trazodone, and clonidine, were not statistically different. There were 33 women who relied only on lifestyle modifications, with 31% of the 16 women with obesity and 59% of the 17 women without obesity reporting improvement in their symptoms (P = .112). Similarly, among the 33 women using nonhormonal medications, 75% of the 20 women with obesity and 77% of the 13 women without obesity experienced relief (P = .9).

Women with obesity are undertreated

Dr. Pershad emphasized the need to improve care and counseling for diverse patients seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms.

“More research is needed to examine how women with medical comorbidities are uniquely impacted by menopause and respond to therapies,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “This can be achieved by actively including more diverse patient populations in women’s health studies, burdened by the social determinants of health and medical comorbidities such as obesity.”

Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, Rochester, Minn., and medical director for The Menopause Society, was not surprised by the findings, particularly given that women with obesity tend to have more hot flashes and night sweats as a result of their extra weight. However, dosage data was not adjusted for BMI in the study and data on hormone levels was unavailable, she said, so it’s difficult to determine from the data whether HT was less effective for women with obesity or whether they were underdosed.

“I think women with obesity are undertreated,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “My guess is people are afraid. Women with obesity also may have other comorbidities,” such as hypertension and diabetes, she said, and “the greater the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the higher risk hormone therapy is.” Providers may therefore be leery of prescribing HT or prescribing it at an appropriately high enough dose to treat menopausal symptoms.

Common practice is to start patients at the lowest dose and titrate up according to symptoms, but “if people are afraid of it, they’re going to start the lowest dose” and may not increase it, Dr. Faubion said. She noted that other nonhormonal options are available, though providers should be conscientious about selecting ones whose adverse events do not include weight gain.

Although the study focused on an understudied population within hormone therapy research, the study was limited by its small size, low overall use of hormone therapy, recall bias, and the researchers’ inability to control for other medications the participants may have been taking.

Dr. Pershad said she is continuing research to try to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced efficacy in women with obesity.

The research did not use any external funding. Dr. Pershad had no industry disclosures, but her colleagues reported honoraria from or speaking for TherapeuticsMD, Astella Pharma, Scynexis, Pharmavite, and Pfizer. Dr. Faubion had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).

The proportions of women reporting relief from only lifestyle modifications or from nonhormonal medications, such as SSRIs/SNRIs, trazodone, and clonidine, were not statistically different. There were 33 women who relied only on lifestyle modifications, with 31% of the 16 women with obesity and 59% of the 17 women without obesity reporting improvement in their symptoms (P = .112). Similarly, among the 33 women using nonhormonal medications, 75% of the 20 women with obesity and 77% of the 13 women without obesity experienced relief (P = .9).

Women with obesity are undertreated

Dr. Pershad emphasized the need to improve care and counseling for diverse patients seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms.

“More research is needed to examine how women with medical comorbidities are uniquely impacted by menopause and respond to therapies,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “This can be achieved by actively including more diverse patient populations in women’s health studies, burdened by the social determinants of health and medical comorbidities such as obesity.”

Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, Rochester, Minn., and medical director for The Menopause Society, was not surprised by the findings, particularly given that women with obesity tend to have more hot flashes and night sweats as a result of their extra weight. However, dosage data was not adjusted for BMI in the study and data on hormone levels was unavailable, she said, so it’s difficult to determine from the data whether HT was less effective for women with obesity or whether they were underdosed.

“I think women with obesity are undertreated,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “My guess is people are afraid. Women with obesity also may have other comorbidities,” such as hypertension and diabetes, she said, and “the greater the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the higher risk hormone therapy is.” Providers may therefore be leery of prescribing HT or prescribing it at an appropriately high enough dose to treat menopausal symptoms.

Common practice is to start patients at the lowest dose and titrate up according to symptoms, but “if people are afraid of it, they’re going to start the lowest dose” and may not increase it, Dr. Faubion said. She noted that other nonhormonal options are available, though providers should be conscientious about selecting ones whose adverse events do not include weight gain.

Although the study focused on an understudied population within hormone therapy research, the study was limited by its small size, low overall use of hormone therapy, recall bias, and the researchers’ inability to control for other medications the participants may have been taking.

Dr. Pershad said she is continuing research to try to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced efficacy in women with obesity.

The research did not use any external funding. Dr. Pershad had no industry disclosures, but her colleagues reported honoraria from or speaking for TherapeuticsMD, Astella Pharma, Scynexis, Pharmavite, and Pfizer. Dr. Faubion had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).

The proportions of women reporting relief from only lifestyle modifications or from nonhormonal medications, such as SSRIs/SNRIs, trazodone, and clonidine, were not statistically different. There were 33 women who relied only on lifestyle modifications, with 31% of the 16 women with obesity and 59% of the 17 women without obesity reporting improvement in their symptoms (P = .112). Similarly, among the 33 women using nonhormonal medications, 75% of the 20 women with obesity and 77% of the 13 women without obesity experienced relief (P = .9).

Women with obesity are undertreated

Dr. Pershad emphasized the need to improve care and counseling for diverse patients seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms.

“More research is needed to examine how women with medical comorbidities are uniquely impacted by menopause and respond to therapies,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “This can be achieved by actively including more diverse patient populations in women’s health studies, burdened by the social determinants of health and medical comorbidities such as obesity.”

Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, Rochester, Minn., and medical director for The Menopause Society, was not surprised by the findings, particularly given that women with obesity tend to have more hot flashes and night sweats as a result of their extra weight. However, dosage data was not adjusted for BMI in the study and data on hormone levels was unavailable, she said, so it’s difficult to determine from the data whether HT was less effective for women with obesity or whether they were underdosed.

“I think women with obesity are undertreated,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “My guess is people are afraid. Women with obesity also may have other comorbidities,” such as hypertension and diabetes, she said, and “the greater the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the higher risk hormone therapy is.” Providers may therefore be leery of prescribing HT or prescribing it at an appropriately high enough dose to treat menopausal symptoms.

Common practice is to start patients at the lowest dose and titrate up according to symptoms, but “if people are afraid of it, they’re going to start the lowest dose” and may not increase it, Dr. Faubion said. She noted that other nonhormonal options are available, though providers should be conscientious about selecting ones whose adverse events do not include weight gain.

Although the study focused on an understudied population within hormone therapy research, the study was limited by its small size, low overall use of hormone therapy, recall bias, and the researchers’ inability to control for other medications the participants may have been taking.

Dr. Pershad said she is continuing research to try to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced efficacy in women with obesity.

The research did not use any external funding. Dr. Pershad had no industry disclosures, but her colleagues reported honoraria from or speaking for TherapeuticsMD, Astella Pharma, Scynexis, Pharmavite, and Pfizer. Dr. Faubion had no disclosures.

AT THE MENOPAUSE SOCIETY ANNUAL MEETING

False-positive Pap smear may indicate genitourinary syndrome

TOPLINE:

, according to a poster presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting.

METHODOLOGY:

- Starting in 2010, researchers in Florida and Antigua saw an increase in the number of perimenopausal women with no history of cervical abnormalities and low risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) presenting with abnormal Pap smears at their clinics.

- They studied 1,500 women aged 30-70 from several clinics. The women had low risk for STIs, a maximum of two sexual partners, and the presence of cervical dysplasia over a period of 12 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly all (96.7%) of the women who received local estrogen treatment had a normal Pap smear following therapy.

- A high number of patients who initially presented with cervical dysplasia underwent interventions such as colposcopies, biopsies, LEEP excisions, cryotherapy, cone biopsies, and hysterectomies because of cervical atrophy.

- The researchers concluded that local estrogen treatment could save patients money spent on treatments for cervical atrophy.

- Some women who underwent cone biopsies and hysterectomies and did not receive local estrogen still had vaginal dysplasia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In this study, we report an early sign of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: false positive cervical dysplasia caused by cervicovaginal atrophy resulting from decreased estrogen levels during perimenopause,” say the investigators. “We also demonstrate how the use of local estrogen therapy can prevent a significant number of interventions and procedures, resulting in significant cost savings. This is particularly relevant as the number of Pap smears conducted in this population represents 50%-60% of all Pap smears performed on women.”

SOURCE:

The data were presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting. The study was led by Alberto Dominguez-Bali, MD, from the Miami Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Human Sexuality.

LIMITATIONS:

The study authors report no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a poster presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting.

METHODOLOGY:

- Starting in 2010, researchers in Florida and Antigua saw an increase in the number of perimenopausal women with no history of cervical abnormalities and low risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) presenting with abnormal Pap smears at their clinics.

- They studied 1,500 women aged 30-70 from several clinics. The women had low risk for STIs, a maximum of two sexual partners, and the presence of cervical dysplasia over a period of 12 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly all (96.7%) of the women who received local estrogen treatment had a normal Pap smear following therapy.

- A high number of patients who initially presented with cervical dysplasia underwent interventions such as colposcopies, biopsies, LEEP excisions, cryotherapy, cone biopsies, and hysterectomies because of cervical atrophy.

- The researchers concluded that local estrogen treatment could save patients money spent on treatments for cervical atrophy.

- Some women who underwent cone biopsies and hysterectomies and did not receive local estrogen still had vaginal dysplasia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In this study, we report an early sign of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: false positive cervical dysplasia caused by cervicovaginal atrophy resulting from decreased estrogen levels during perimenopause,” say the investigators. “We also demonstrate how the use of local estrogen therapy can prevent a significant number of interventions and procedures, resulting in significant cost savings. This is particularly relevant as the number of Pap smears conducted in this population represents 50%-60% of all Pap smears performed on women.”

SOURCE:

The data were presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting. The study was led by Alberto Dominguez-Bali, MD, from the Miami Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Human Sexuality.

LIMITATIONS:

The study authors report no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a poster presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting.

METHODOLOGY:

- Starting in 2010, researchers in Florida and Antigua saw an increase in the number of perimenopausal women with no history of cervical abnormalities and low risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) presenting with abnormal Pap smears at their clinics.

- They studied 1,500 women aged 30-70 from several clinics. The women had low risk for STIs, a maximum of two sexual partners, and the presence of cervical dysplasia over a period of 12 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly all (96.7%) of the women who received local estrogen treatment had a normal Pap smear following therapy.

- A high number of patients who initially presented with cervical dysplasia underwent interventions such as colposcopies, biopsies, LEEP excisions, cryotherapy, cone biopsies, and hysterectomies because of cervical atrophy.

- The researchers concluded that local estrogen treatment could save patients money spent on treatments for cervical atrophy.

- Some women who underwent cone biopsies and hysterectomies and did not receive local estrogen still had vaginal dysplasia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In this study, we report an early sign of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: false positive cervical dysplasia caused by cervicovaginal atrophy resulting from decreased estrogen levels during perimenopause,” say the investigators. “We also demonstrate how the use of local estrogen therapy can prevent a significant number of interventions and procedures, resulting in significant cost savings. This is particularly relevant as the number of Pap smears conducted in this population represents 50%-60% of all Pap smears performed on women.”

SOURCE:

The data were presented at The Menopause Society 2023 annual meeting. The study was led by Alberto Dominguez-Bali, MD, from the Miami Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Human Sexuality.

LIMITATIONS:

The study authors report no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE MENOPAUSE SOCIETY ANNUAL MEETING

CBT effectively treats sexual concerns in menopausal women

PHILADELPHIA – . Four CBT sessions specifically focused on sexual concerns resulted in decreased sexual distress and concern, reduced depressive and menopausal symptoms, and increased sexual desire and functioning, as well as improved body image and relationship satisfaction.

An estimated 68%-87% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women report sexual concerns, Sheryl Green, PhD, CPsych, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University and a psychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare’s Women’s Health Concerns Clinic, both in Hamilton, Ont., told attendees at the meeting.

“Sexual concerns over the menopausal transition are not just physical, but they’re also psychological and emotional,” Dr. Green said. “Three common challenges include decreased sexual desire, a reduction in physical arousal and ability to achieve an orgasm, and sexual pain and discomfort during intercourse.”

The reasons for these concerns are multifactorial, she said. Decreased sexual desire can stem from stress, medical problems, their relationship with their partner, or other causes. A woman’s difficulty with reduced physical arousal or ability to have an orgasm can result from changes in hormone levels and vaginal changes, such as vaginal atrophy, which can also contribute to the sexual pain or discomfort reported by 17%-45% of postmenopausal women.

Two pharmacologic treatments exist for sexual concerns: oral flibanserin (Addyi) and injectable bremelanotide (Vyleesi). But many women may be unable or unwilling to take medication for their concerns. Previous research from Lori Brotto has found cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness interventions to effectively improve sexual functioning in women treated for gynecologic cancer and in women without a history of cancer.

“Sexual function needs to be understood from a bio-psychosocial model, looking at the biologic factors, the psychological factors, the sociocultural factors, and the interpersonal factors,” Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and a psychologist at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said in an interview.

“They can all overlap, and the clinician can ask a few pointed questions that help identify what the source of the problem is,” said Dr. Kingsberg, who was not involved in this study. She noted that the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has an algorithm that can help in determining the source of the problems.

“Sometimes it’s going to be a biologic condition for which pharmacologic options are nice, but even if it is primarily pharmacologic, psychotherapy is always useful,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Once the problem is there, even if it’s biologically based, then you have all the things in terms of the cognitive distortion, anxiety,” and other issues that a cognitive behavioral approach can help address. “And access is now much wider because of telehealth,” she added.

‘Psychology of menopause’

The study led by Dr. Green focused on peri- and postmenopausal women, with an average age of 50, who were experiencing primary sexual concerns based on a score of at least 26 on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Among the 20 women recruited for the study, 6 had already been prescribed hormone therapy for sexual concerns.

All reported decreased sexual desire, 17 reported decreased sexual arousal, 14 had body image dissatisfaction related to sexual concerns, and 6 reported urogenital problems. Nine of the women were in full remission from major depressive disorder, one had post-traumatic stress syndrome, and one had subclinical generalized anxiety disorder.

After spending 4 weeks on a wait list as self-control group for the study, the 15 women who completed the trial underwent four individual CBT sessions focusing on sexual concerns. The first session focused on psychoeducation and thought monitoring, and the second focused on cognitive distortions, cognitive strategies, and unhelpful beliefs or expectations related to sexual concerns. The third session looked at the role of problematic behaviors and behavioral experiments, and the fourth focused on continuation of strategies, long-term goals, and maintaining gains.

The participants completed eight measures at baseline, after the 4 weeks on the wait list, and after the four CBT sessions to assess the following:

- Sexual satisfaction, distress, and desire, using the FSFI, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), and the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ).

- Menopause symptoms, using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS).

- Body image, using the Dresden Body Image Questionnaire (DBIQ).

- Relationship satisfaction, using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI).

- Depression, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

- Anxiety, using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

The women did not experience any significant changes while on the wait list except a slight decrease on the FSDQ concern subscale. Following the CBT sessions, however, the women experienced a significant decrease in sexual distress and concern as well as an increase in sexual dyadic desire and sexual functioning (P = .003 for FSFI, P = .002 for FSDS-R, and P = .003 for FSDQ).

Participants also experienced a decrease in depression (P < .0001) and menopausal symptoms (P = .001) and an increase in body-image satisfaction (P = .018) and relationship satisfaction (P = .0011) after the CBT sessions. The researchers assessed participants’ satisfaction with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire after the CBT sessions and reported some of the qualitative findings.

“The treatment program was able to assist me with recognizing that some of my sexual concerns were normal, emotional as well as physical and hormonal, and provided me the ability to delve more deeply into the psychology of menopause and how to work through symptoms and concerns in more manageable pieces,” one participant wrote. Another found helpful the “homework exercises of recognizing a thought/feeling/emotion surrounding how I feel about myself/body and working through. More positive thought pattern/restructuring a response the most helpful.”

The main complaint about the program was that it was too short, with women wanting more sessions to help continue their progress.

Not an ‘either-or’ approach

Dr. Kingsberg said ISSWSH has a variety of sexual medicine practitioners, including providers who can provide CBT for sexual concerns, and the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists has a referral directory.

“Keeping in mind the bio-psychosocial model, sometimes psychotherapy is going to be a really effective treatment for sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Sometimes the pharmacologic option is going to be a really effective treatment for some concerns, and sometimes the combination is going to have a really nice treatment effect. So it’s not a one-size-fits-all, and it doesn’t have to be an either-or.”

The sexual concerns of women still do not get adequately addressed in medical schools and residencies, Dr. Kingsberg said, which is distinctly different from how male sexual concerns are addressed in health care.

“Erectile dysfunction is kind of in the norm, and women are still a little hesitant to bring up their sexual concerns,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “They don’t know if it’s appropriate and they’re hoping that their clinician will ask.”

One way clinicians can do that is with a global question for all their patients: “Most of my patients have sexual questions or concerns; what concerns do you have?”

“They don’t have to go through a checklist of 10 things,” Dr. Kingsberg said. If the patient does not bring anything up, providers can then ask a single follow up question: “Do you have any concerns with desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain?” That question, Dr. Kingsberg said, covers the four main areas of concern.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Green reported no disclosures. Dr. Kingsberg has consulted for or served on the advisory board for Alloy, Astellas, Bayer, Dare Bioscience, Freya, Reunion Neuroscience, Materna Medical, Madorra, Palatin, Pfizer, ReJoy, Sprout, Strategic Science Technologies, and MsMedicine.

PHILADELPHIA – . Four CBT sessions specifically focused on sexual concerns resulted in decreased sexual distress and concern, reduced depressive and menopausal symptoms, and increased sexual desire and functioning, as well as improved body image and relationship satisfaction.

An estimated 68%-87% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women report sexual concerns, Sheryl Green, PhD, CPsych, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at McMaster University and a psychologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare’s Women’s Health Concerns Clinic, both in Hamilton, Ont., told attendees at the meeting.

“Sexual concerns over the menopausal transition are not just physical, but they’re also psychological and emotional,” Dr. Green said. “Three common challenges include decreased sexual desire, a reduction in physical arousal and ability to achieve an orgasm, and sexual pain and discomfort during intercourse.”

The reasons for these concerns are multifactorial, she said. Decreased sexual desire can stem from stress, medical problems, their relationship with their partner, or other causes. A woman’s difficulty with reduced physical arousal or ability to have an orgasm can result from changes in hormone levels and vaginal changes, such as vaginal atrophy, which can also contribute to the sexual pain or discomfort reported by 17%-45% of postmenopausal women.

Two pharmacologic treatments exist for sexual concerns: oral flibanserin (Addyi) and injectable bremelanotide (Vyleesi). But many women may be unable or unwilling to take medication for their concerns. Previous research from Lori Brotto has found cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness interventions to effectively improve sexual functioning in women treated for gynecologic cancer and in women without a history of cancer.

“Sexual function needs to be understood from a bio-psychosocial model, looking at the biologic factors, the psychological factors, the sociocultural factors, and the interpersonal factors,” Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and a psychologist at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said in an interview.

“They can all overlap, and the clinician can ask a few pointed questions that help identify what the source of the problem is,” said Dr. Kingsberg, who was not involved in this study. She noted that the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has an algorithm that can help in determining the source of the problems.

“Sometimes it’s going to be a biologic condition for which pharmacologic options are nice, but even if it is primarily pharmacologic, psychotherapy is always useful,” Dr. Kingsberg said. “Once the problem is there, even if it’s biologically based, then you have all the things in terms of the cognitive distortion, anxiety,” and other issues that a cognitive behavioral approach can help address. “And access is now much wider because of telehealth,” she added.

‘Psychology of menopause’

The study led by Dr. Green focused on peri- and postmenopausal women, with an average age of 50, who were experiencing primary sexual concerns based on a score of at least 26 on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Among the 20 women recruited for the study, 6 had already been prescribed hormone therapy for sexual concerns.

All reported decreased sexual desire, 17 reported decreased sexual arousal, 14 had body image dissatisfaction related to sexual concerns, and 6 reported urogenital problems. Nine of the women were in full remission from major depressive disorder, one had post-traumatic stress syndrome, and one had subclinical generalized anxiety disorder.

After spending 4 weeks on a wait list as self-control group for the study, the 15 women who completed the trial underwent four individual CBT sessions focusing on sexual concerns. The first session focused on psychoeducation and thought monitoring, and the second focused on cognitive distortions, cognitive strategies, and unhelpful beliefs or expectations related to sexual concerns. The third session looked at the role of problematic behaviors and behavioral experiments, and the fourth focused on continuation of strategies, long-term goals, and maintaining gains.

The participants completed eight measures at baseline, after the 4 weeks on the wait list, and after the four CBT sessions to assess the following:

- Sexual satisfaction, distress, and desire, using the FSFI, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), and the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ).

- Menopause symptoms, using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS).

- Body image, using the Dresden Body Image Questionnaire (DBIQ).

- Relationship satisfaction, using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI).

- Depression, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

- Anxiety, using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

The women did not experience any significant changes while on the wait list except a slight decrease on the FSDQ concern subscale. Following the CBT sessions, however, the women experienced a significant decrease in sexual distress and concern as well as an increase in sexual dyadic desire and sexual functioning (P = .003 for FSFI, P = .002 for FSDS-R, and P = .003 for FSDQ).

Participants also experienced a decrease in depression (P < .0001) and menopausal symptoms (P = .001) and an increase in body-image satisfaction (P = .018) and relationship satisfaction (P = .0011) after the CBT sessions. The researchers assessed participants’ satisfaction with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire after the CBT sessions and reported some of the qualitative findings.