User login

Discrepancies in Skin Cancer Screening Reporting Among Patients, Primary Care Physicians, and Patient Medical Records

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

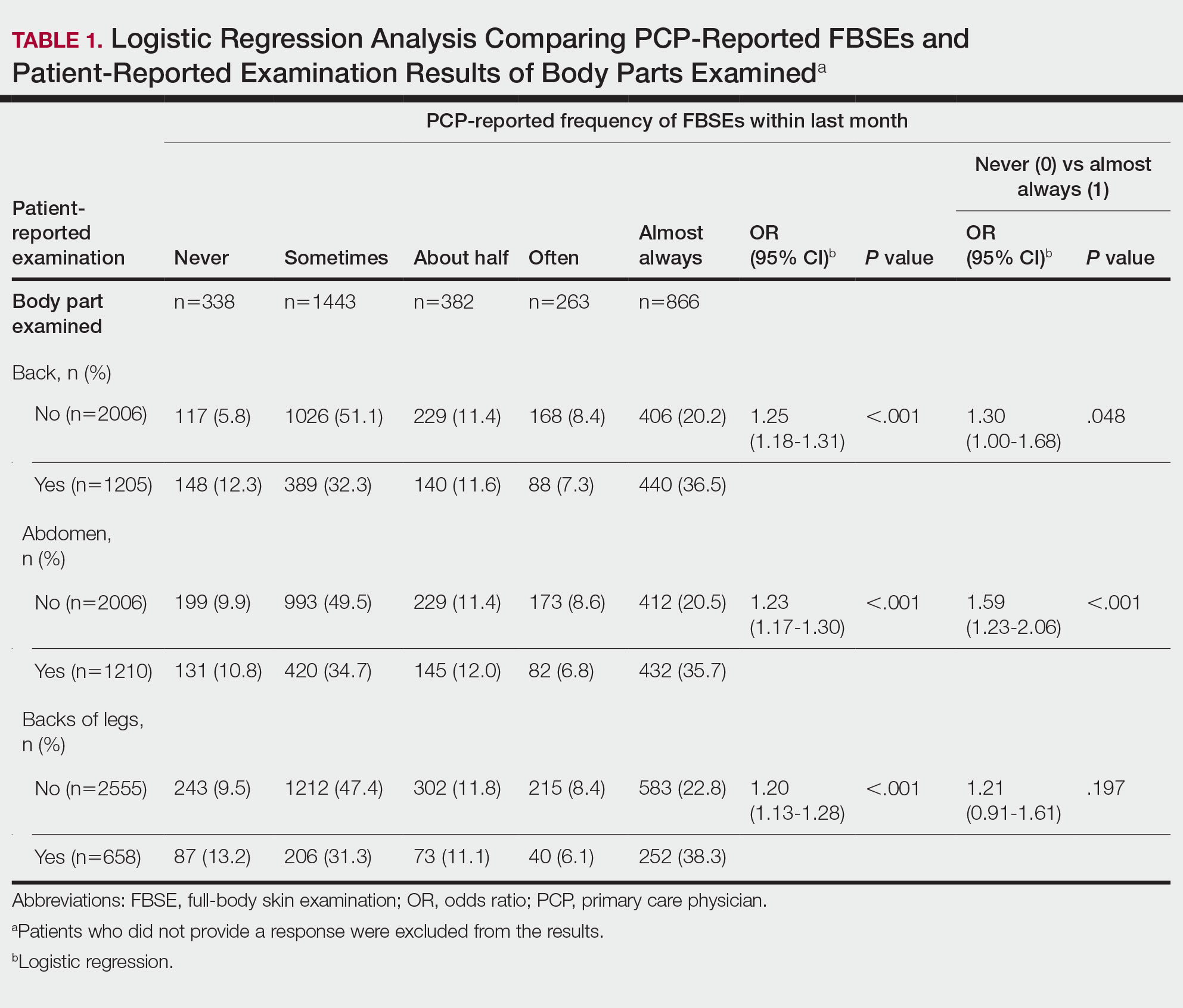

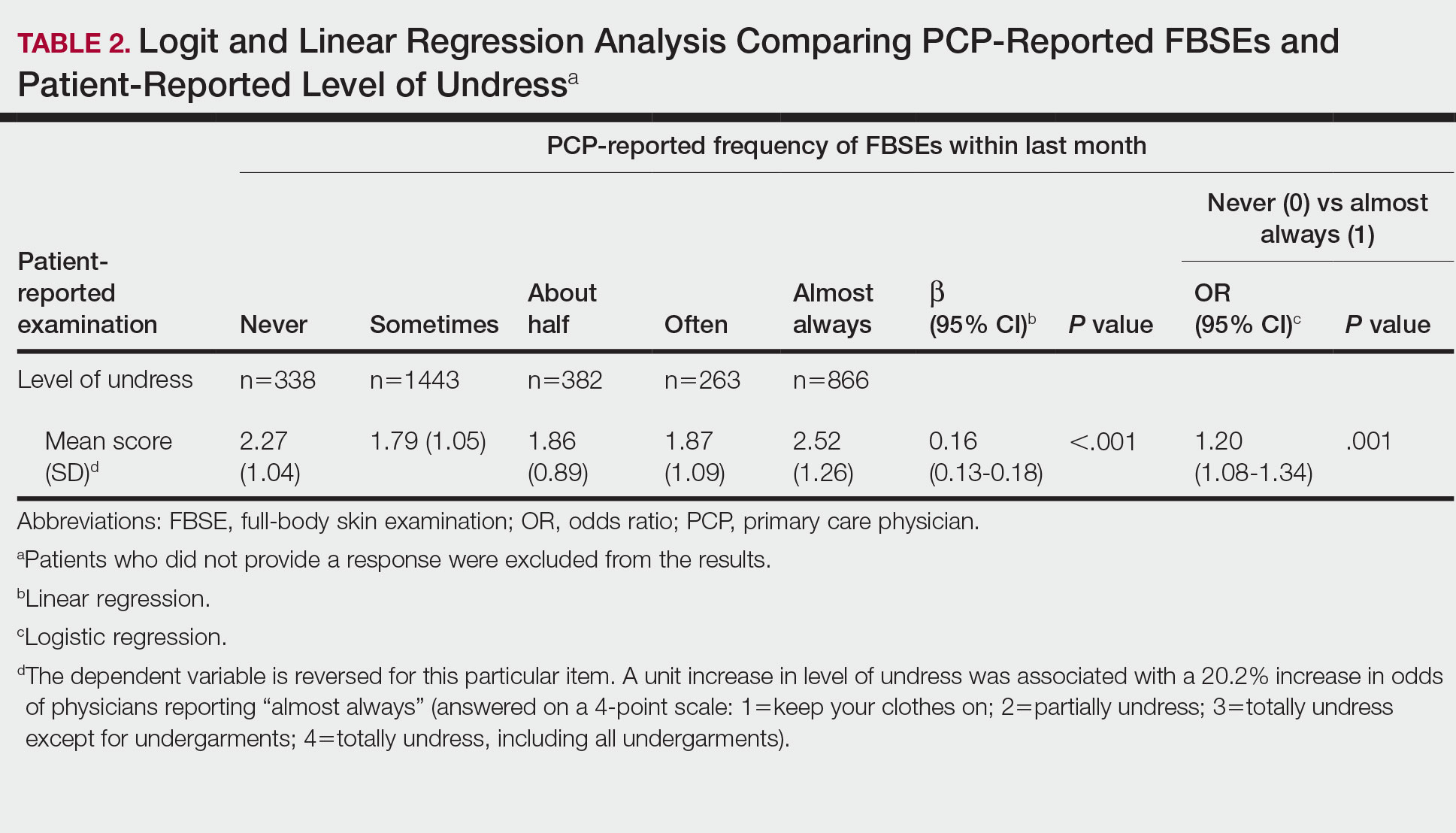

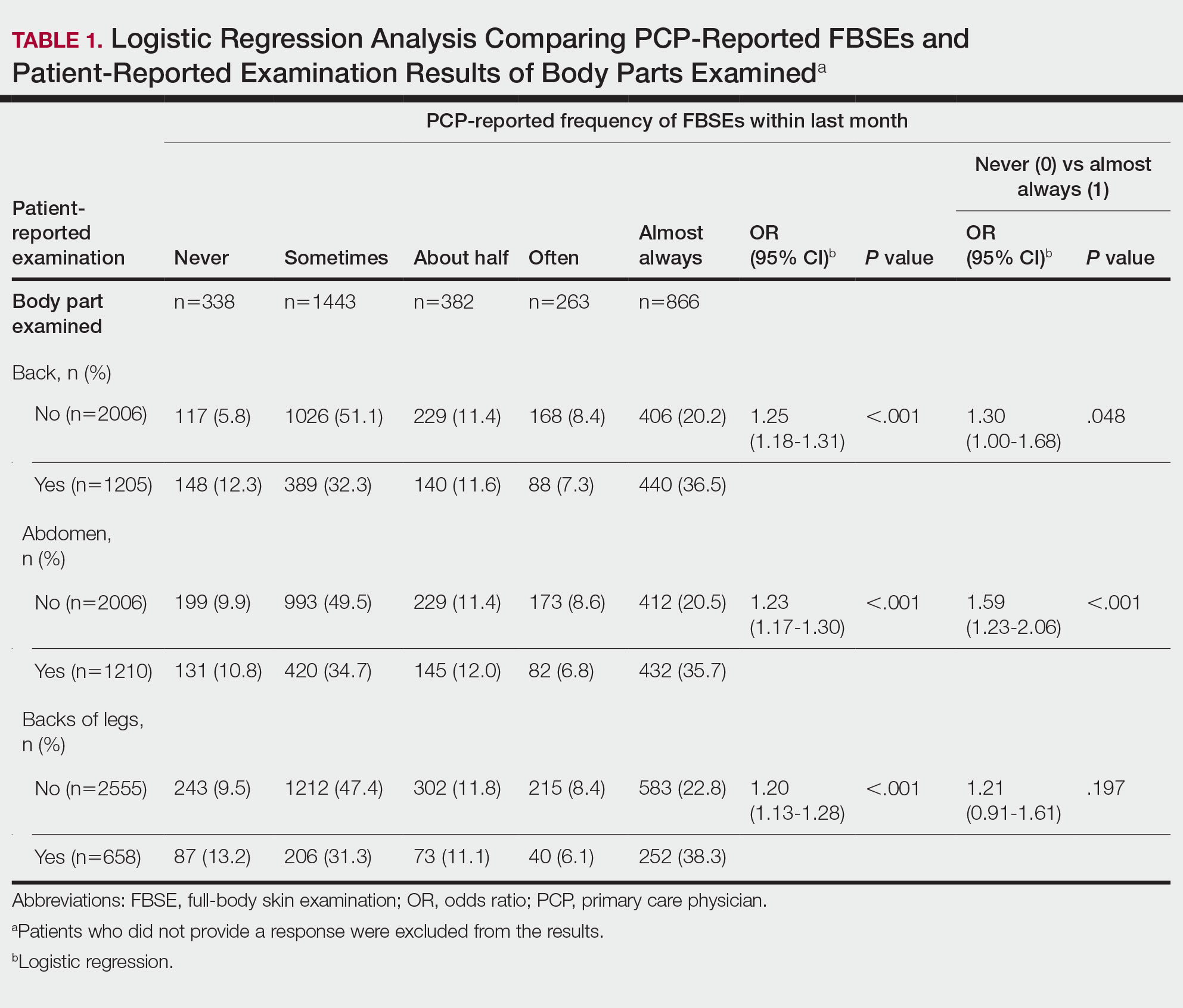

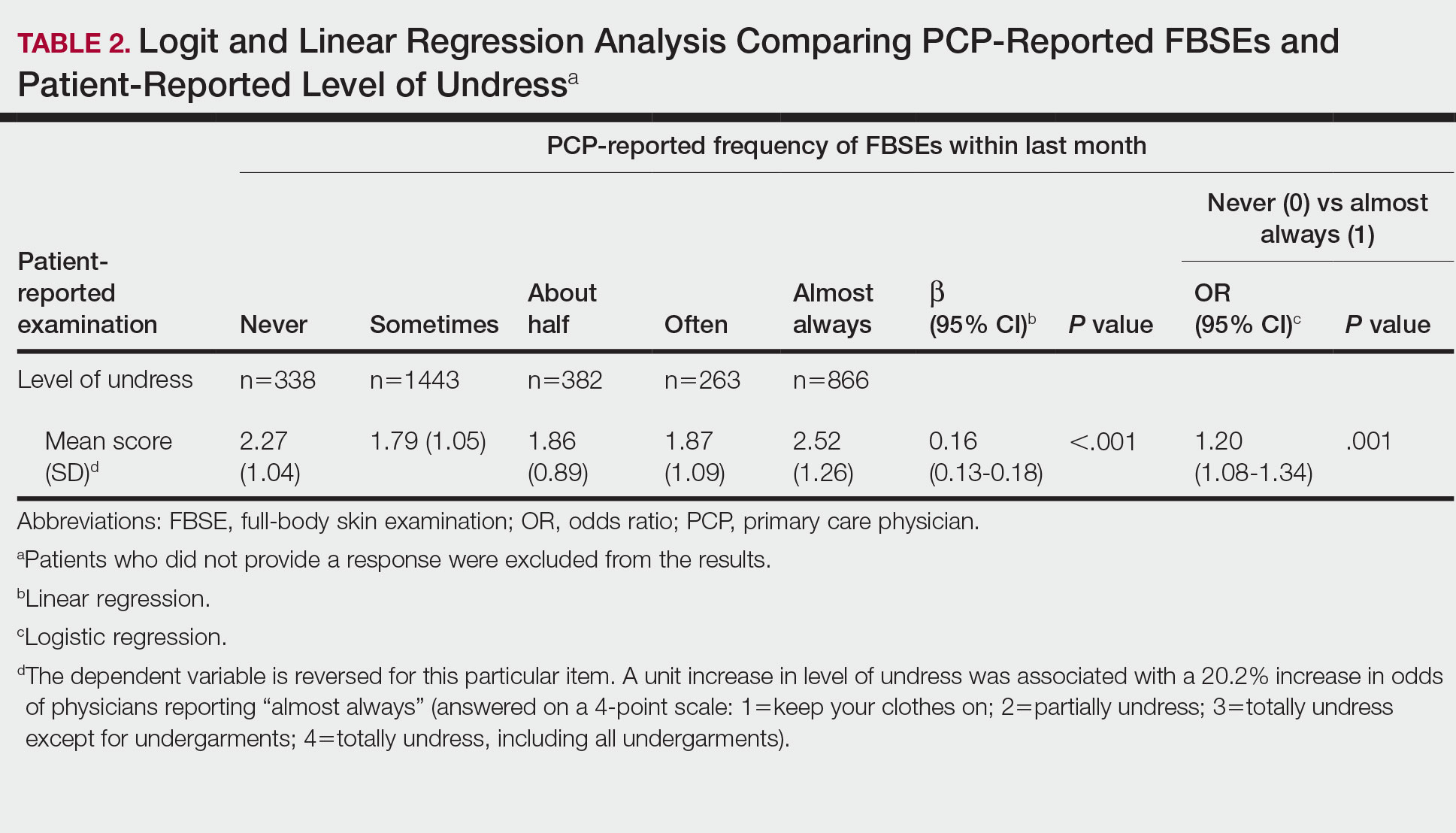

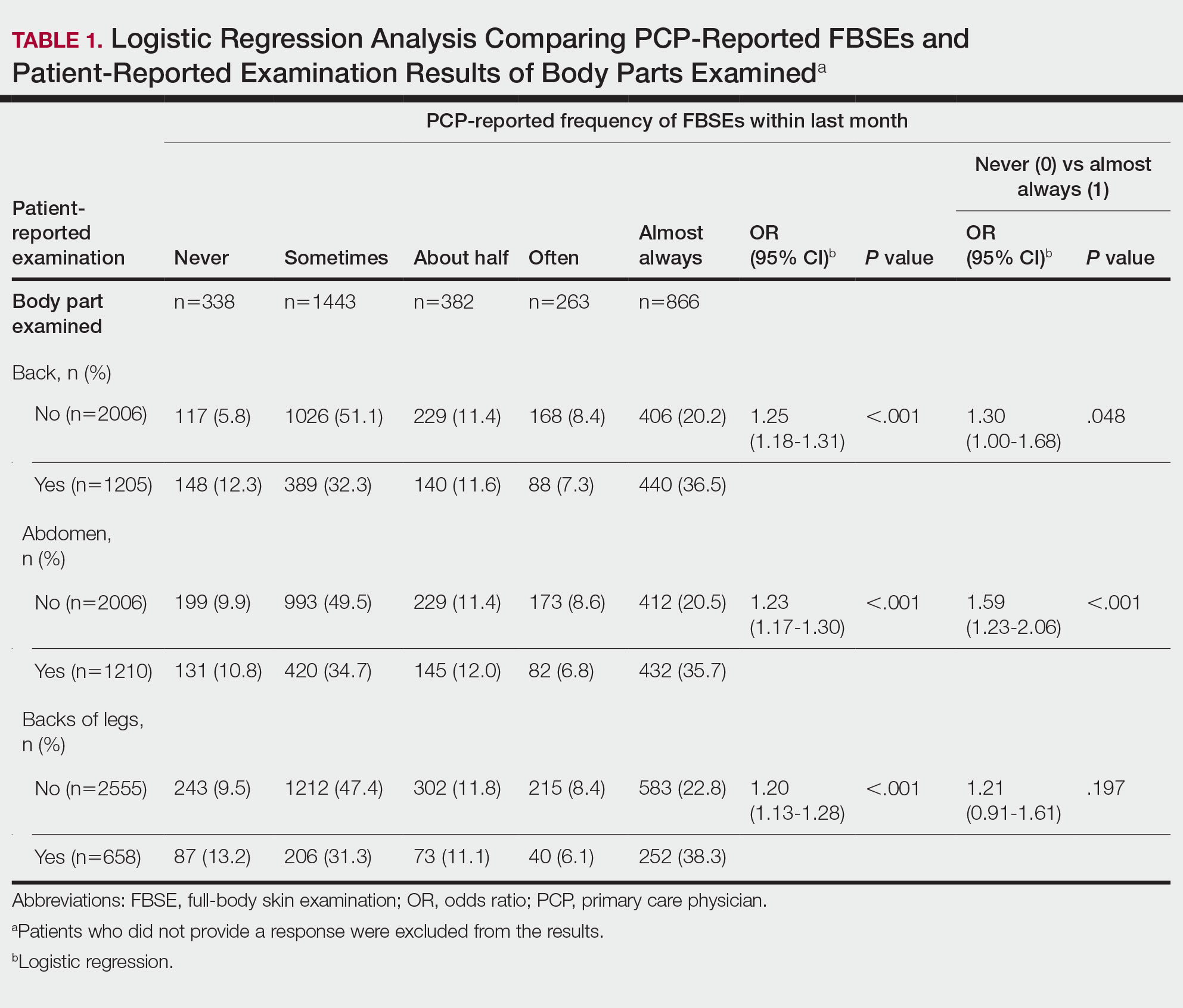

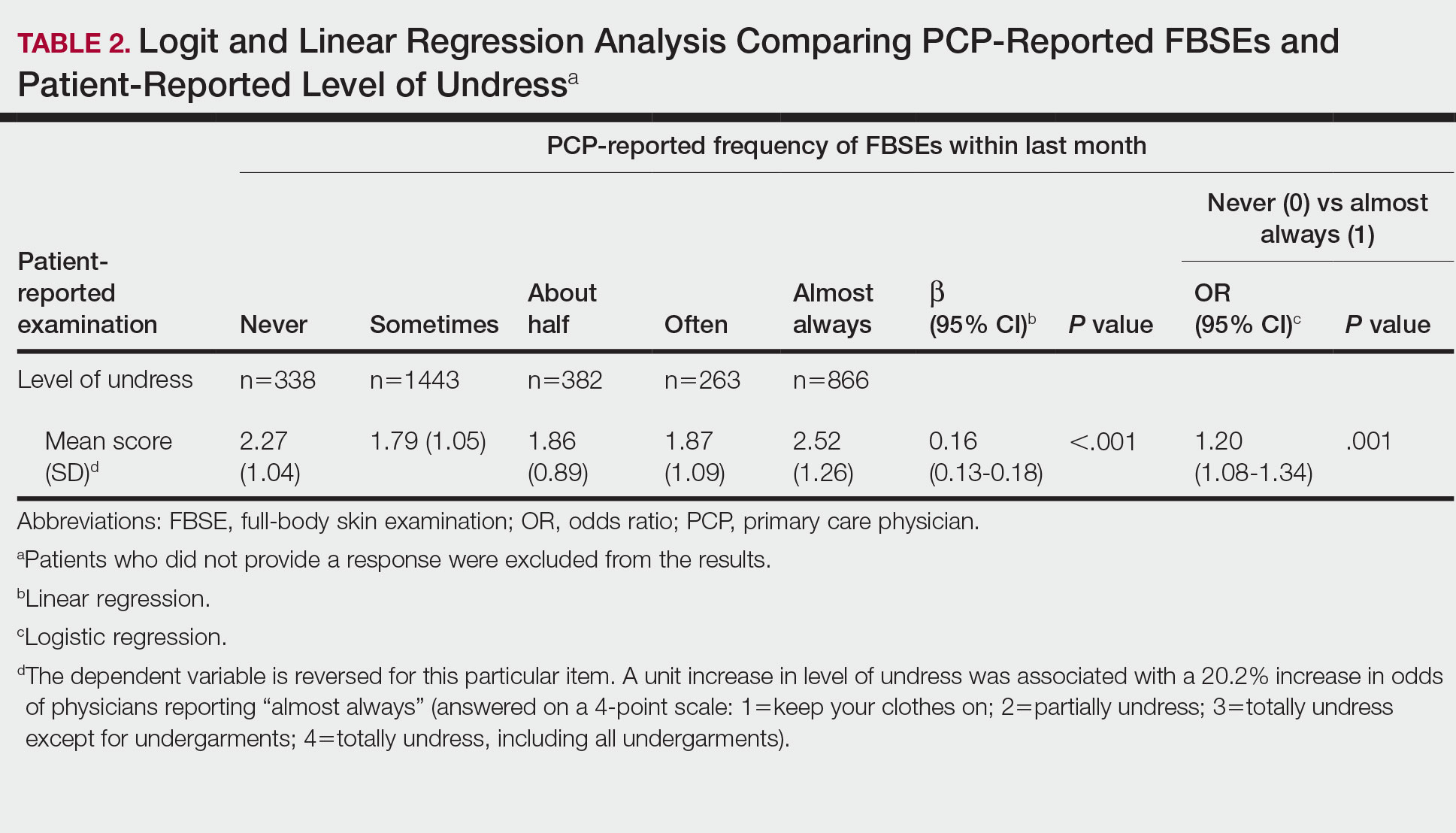

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics

The final sample included data from 53 physicians and 3343 patients. The study sample mean age (SD) was 50.3 (9.9) years for PCPs (n=53) and 59.8 (16.9) years for patients (n=3343). The physician sample was 36% female and predominantly White (83%). Ninety-one percent of the PCPs had an MD (the remaining had a DO degree), and the mean (SD) years practicing was 21.8 (10.6) years. Seventeen percent of PCPs were trained in internal medicine, 4% in internal medicine and pediatrics, and 79% family medicine; 79% of PCPs had received prior training in dermatology. The patient sample was 58% female, predominantly White (84%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (95%), had completed high school (94%), and earned more than $40,000 annually (66%).

Physician- and Patient-Reported FBSEs

Physicians reported performing FBSEs with variable frequency. Among PCPs who conducted FBSEs with greater frequency, there was a modest increase in the odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: odds ratio [OR], 24.5% [95% CI, 1.18-1.31; P<.001]; abdomen: OR, 23.3% [95% CI, 1.17-1.30; P<.001]; backs of legs: OR, 20.4% [95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P<.001])(Table 1). The patient-reported level of undress during examination was significantly associated with physician-reported FBSE (β=0.16 [95% CI, 0.13-0.18; P<.001])(Table 2).

Because of the bimodal distribution of scores in the physician-reported frequency of FBSEs, particularly pertaining to the extreme points of the scale, we further repeated analysis with only the never and almost always groups (Table 1). Primary care providers who reported almost always for FBSE had 29.6% increased odds of patient-reported back examination (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P=.048) and 59.3% increased odds of patient-reported abdomen examination (95% CI, 1.23-2.06; P<.001). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE were 56%, 40%, and 26%, respectively. The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE were 52%, 51%, and 30%, respectively. Raw percentages were calculated by dividing the number of "yes" responses by participants for each body part examined by thetotal number of participant responses (“yes” and “no”) for each respective body part. There was no significant change in odds of patient-reported backs of legs examined with PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE. In addition, a greater patient-reported level of undress was associated with 20.2% increased odds of PCPs reporting almost always conducting an FBSE (95% CI, 1.08-1.34; P=.001).

FBSEs in Patient Medical Records

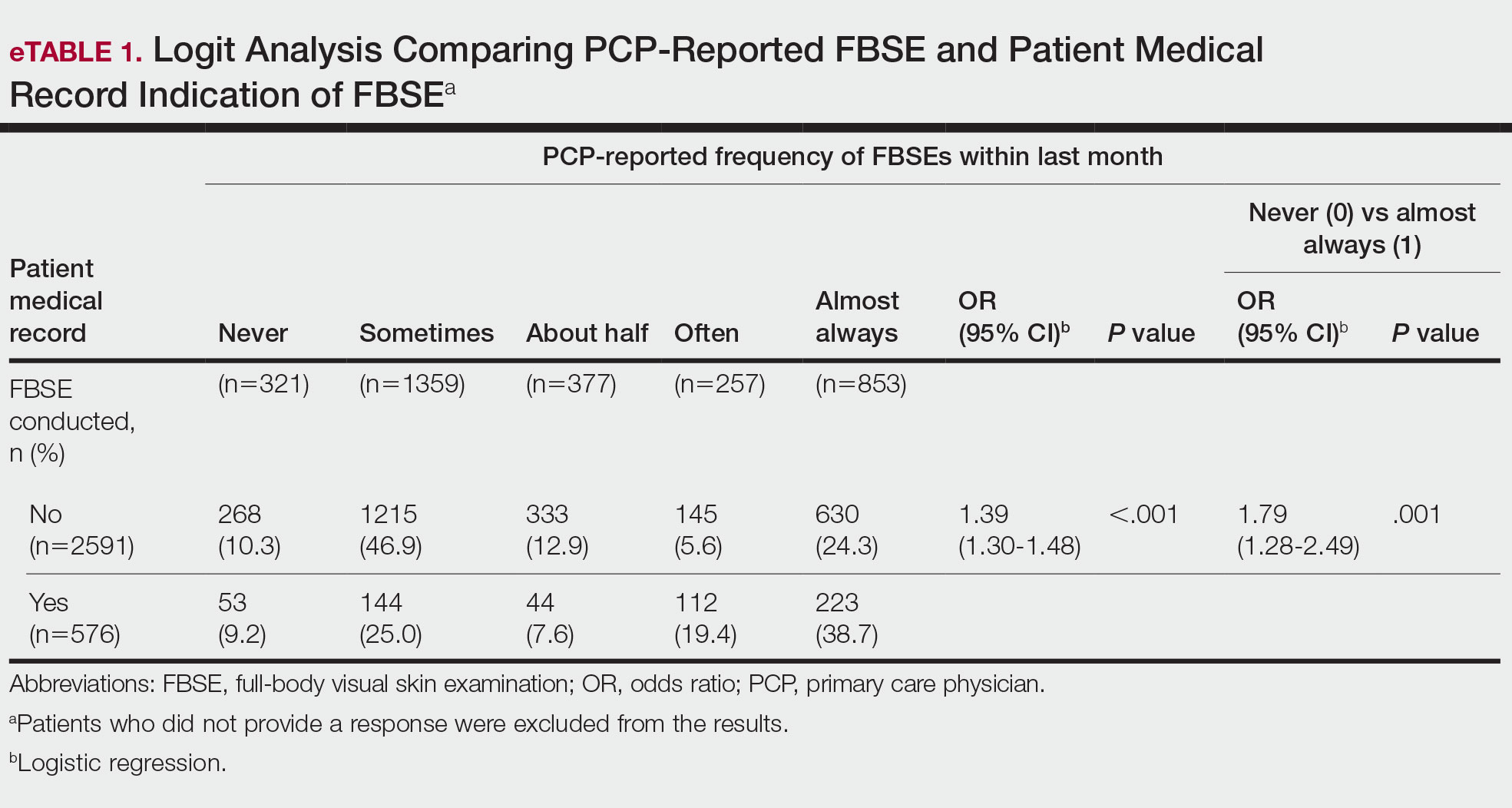

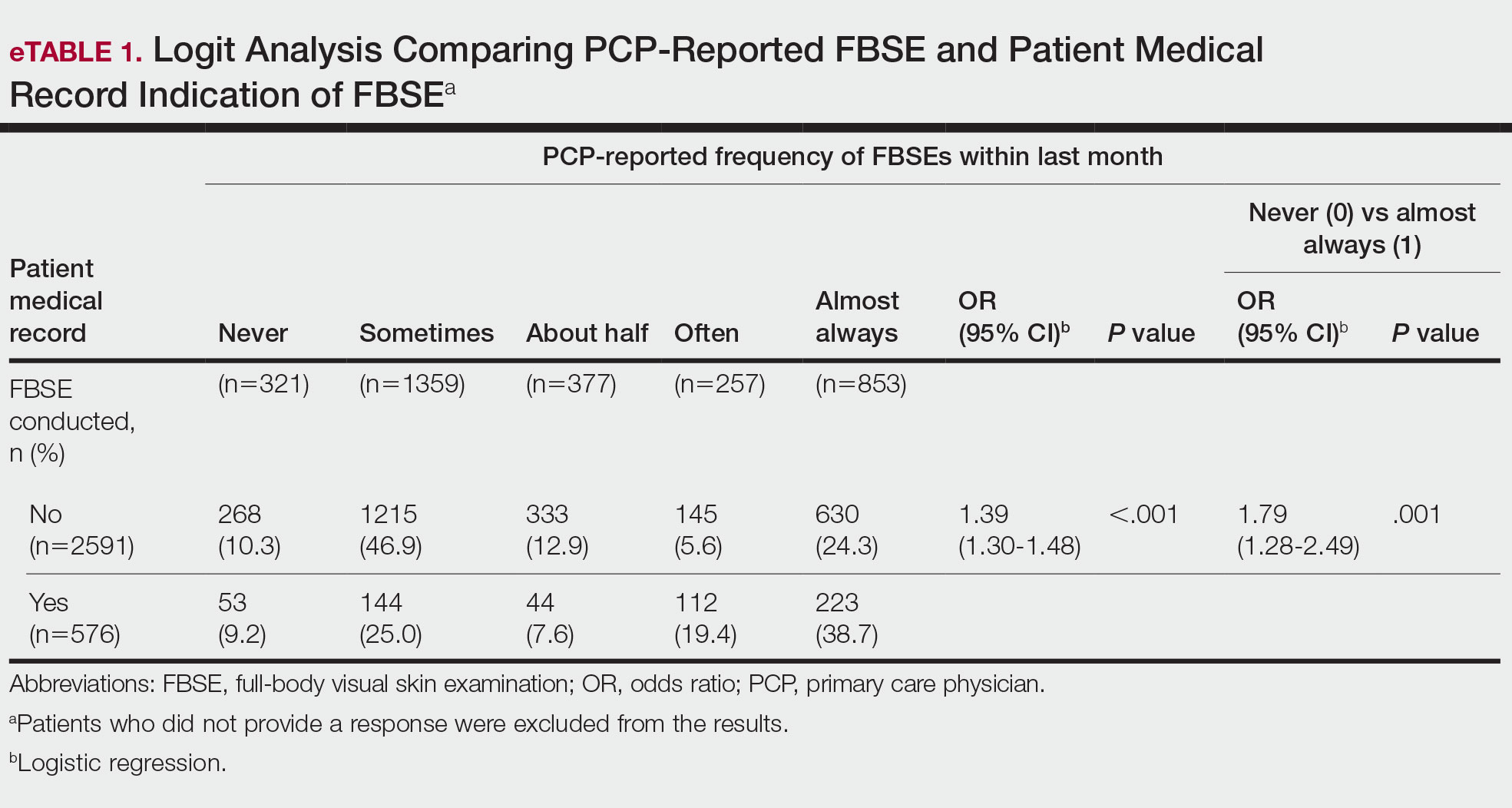

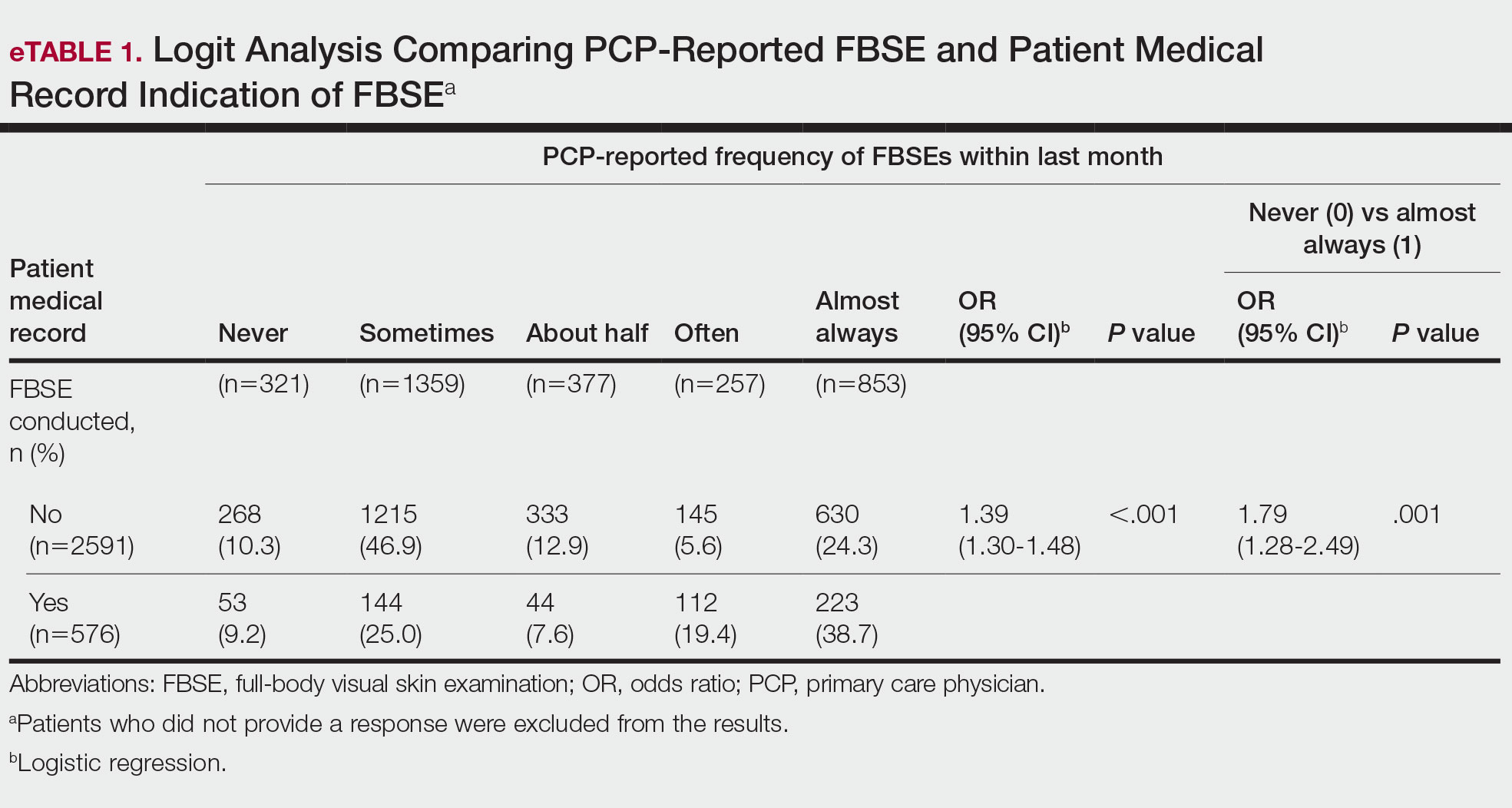

When comparing PCP-reported FBSE and report of FBSE in patient medical records, there was a 39.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating FBSE when physicians reported conducting an FBSE with greater frequency (95% CI, 1.30-1.48; P<.001)(eTable 1). When examining PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE, a report of almost always was associated with 79.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating that an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.28-2.49; P=.001). The raw percentage of the patient medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE was 17% and 26% when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE.

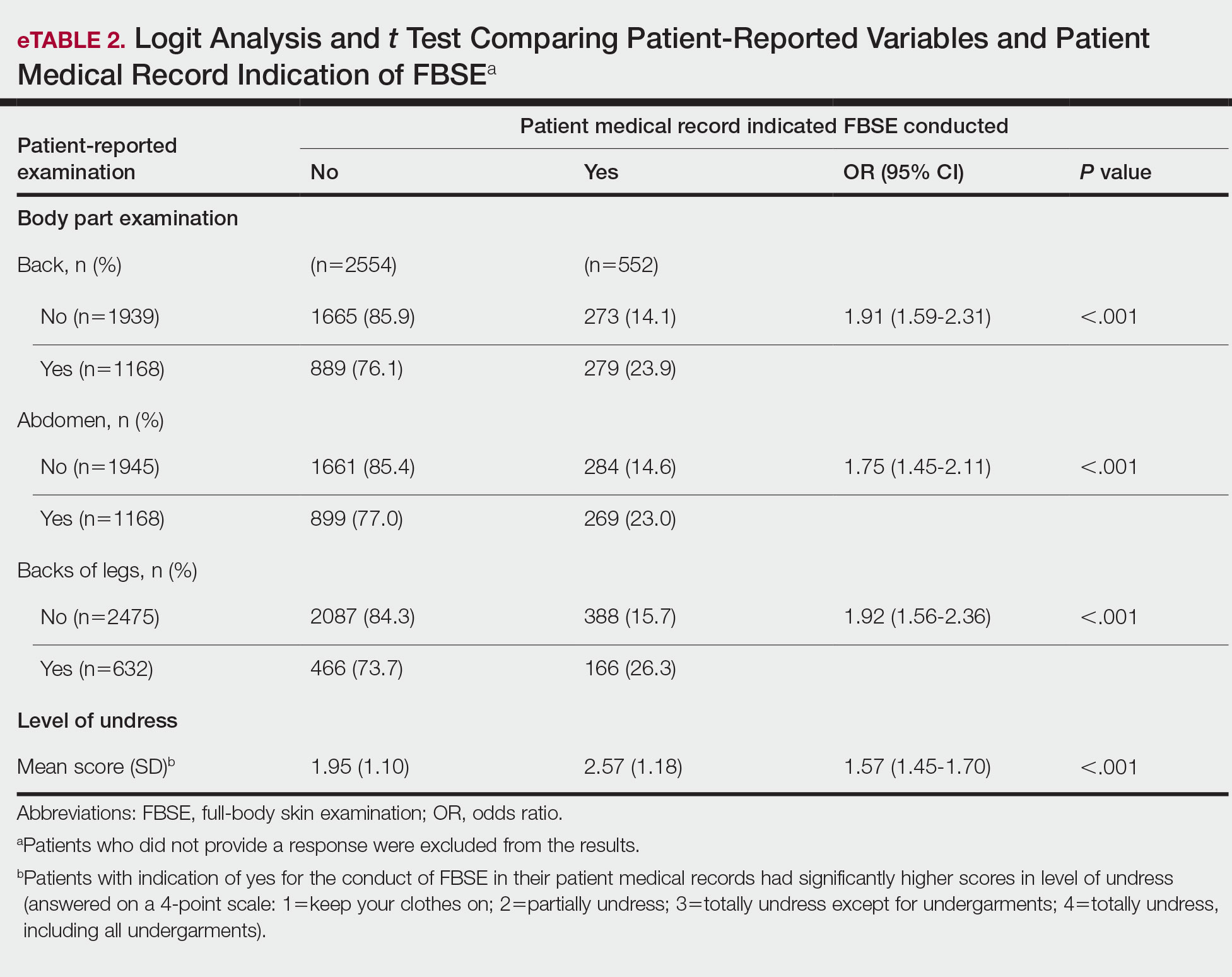

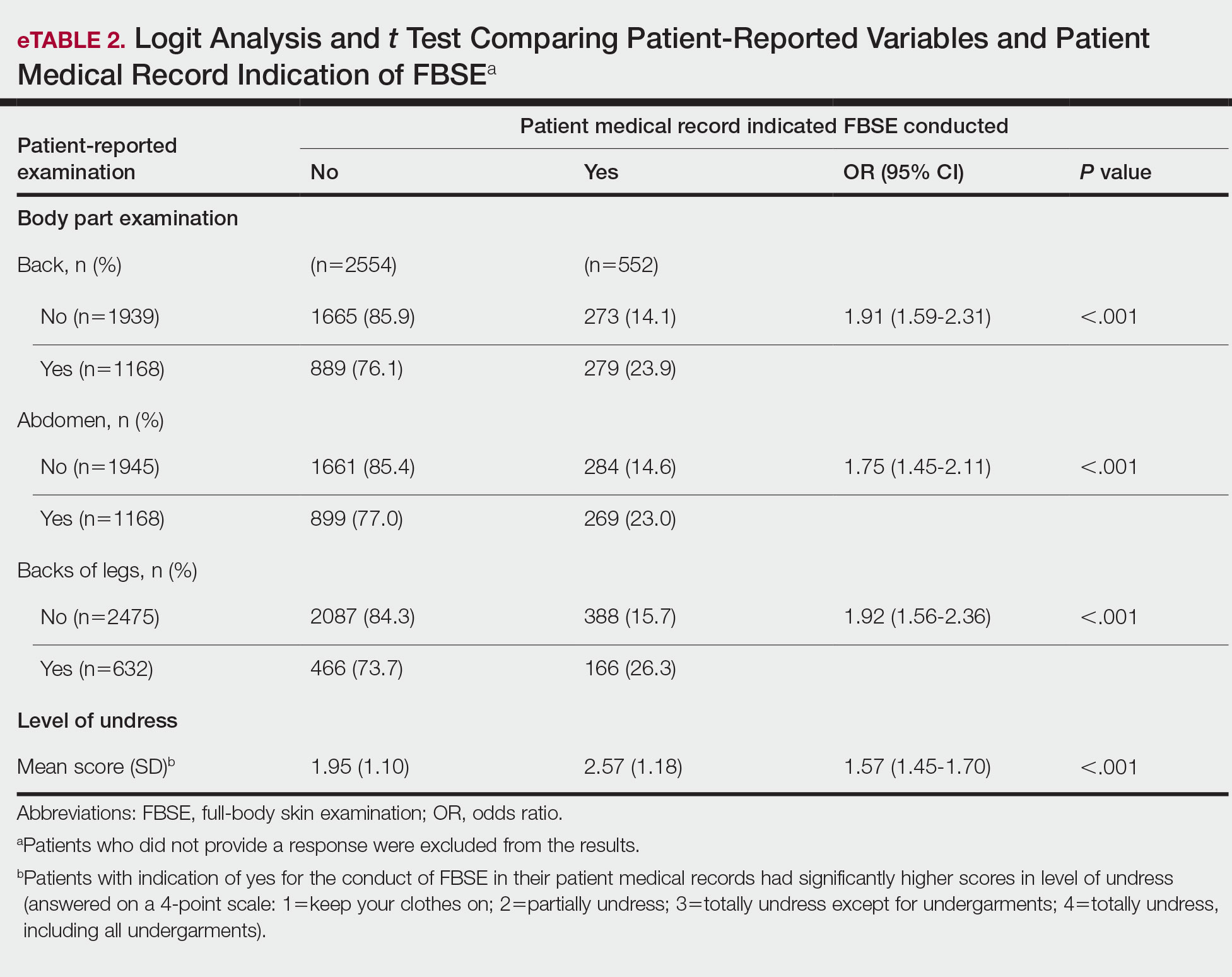

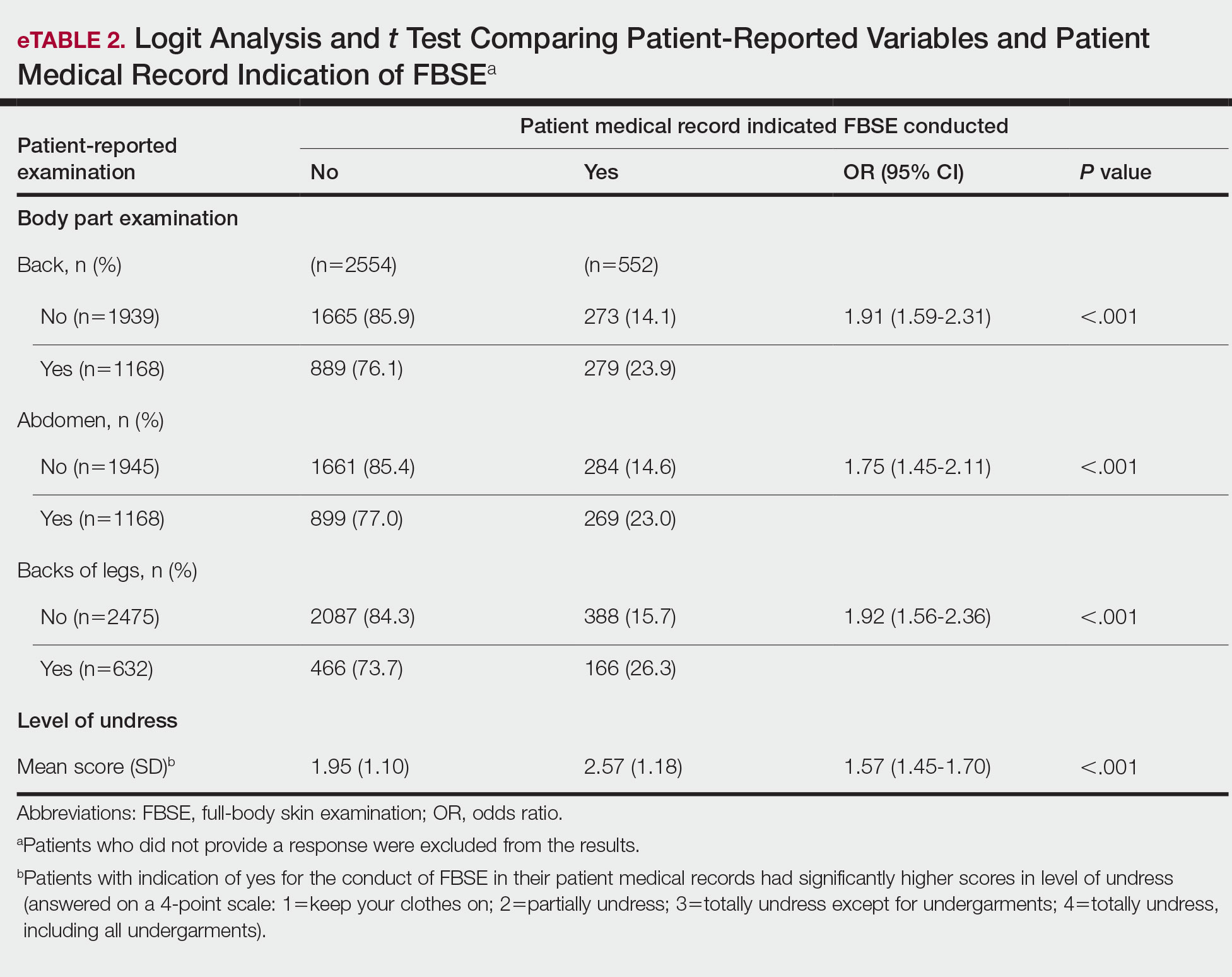

When comparing the patient-reported body part examined with patient FBSE medical record documentation, an indication of yes for FBSE on the patient medical record was associated with a considerable increase in odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: 91.4% [95% CI, 1.59-2.31; P<.001]; abdomen: 75.0% [95% CI, 1.45-2.11; P<.001]; backs of legs: 91.6% [95% CI, 1.56-2.36; P<.001])(eTable 2). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined vs not examined when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE was completed were 24% vs 14%, 23% vs 15%, and 26% vs 16%, respectively. An increase in patient-reported level of undress was associated with a 57.0% increased odds of their medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.45-1.70; P<.001).

COMMENT How PCPs Perform FBSEs Varies

We found that PCPs performed FBSEs with variable frequency, and among those who did, the patient report of their examination varied considerably (Table 1). There appears to be considerable ambiguity in each of these means of determining the extent to which the skin was inspected for skin cancer, which may render the task of improving such inspection more difficult. We asked patients whether their back, abdomen, and backs of legs were examined as an assessment of some of the variety of areas inspected during an FBSE. During a general well-visit appointment, a patient’s back and abdomen may be examined for multiple reasons. Patients may have misinterpreted elements of the pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal, or musculoskeletal examinations as being part of the FBSE. The back and abdomen—the least specific features of the FBSE—were reported by patients to be the most often examined. Conversely, the backs of the legs—the most specific feature of the FBSE—had the lowest odds of being examined (Table 1).

In addition to the potential limitations of patient awareness of physician activity, our results also could be explained by differences among PCPs in how they performed FBSEs. There is no standardized method of conducting an FBSE. Furthermore, not all medical students and residents are exposed to dermatology training. In our sample of 53 physicians, 79% had reported receiving dermatology training; however, we did not assess the extent to which they had been trained in conducting an FBSE and/or identifying malignant lesions. In an American survey of 659 medical students, more than two-thirds of students had never been trained or never examined a patient for skin cancer.21 In another American survey of 342 internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology residents across 7 medical schools and 4 residency programs, more than three-quarters of residents had never been trained in skin cancer screening.22 Our findings reflect insufficient and inconsistent training in skin cancer screening and underscore the need for mandatory education to ensure quality FBSEs are performed in the primary care setting.

Frequency of PCPs Performing FBSEs

Similar to prior studies analyzing the frequency of FBSE performance in the primary care setting,16,19,23,24 more than half of our PCP sample reported sometimes to never conducting FBSEs. The percentage of physicians who reported conducting FBSEs in our sample was greater than the proportion reported by the National Health Interview Survey, in which only 8% of patients received an FBSE in the prior year by a PCP or obstetrician/gynecologist,16 but similar to a smaller patient study.19 In that study, 87% of patients, regardless of their skin cancer history, also reported that they would like their PCP to perform an FBSE regularly.19 Although some of our patient participants may have declined an FBSE, it is unlikely that that would have entirely accounted for the relatively low number of PCPs who reported frequently performing FBSEs.

Documentation in Medical Records of FBSEs

Compared to PCP self-reported performance of FBSEs, considerably fewer PCPs marked the patient medical record as having completed an FBSE. Among patients with medical records that indicated an FBSE had been conducted, they reported higher odds of all 3 body parts being examined, the highest being the backs of the legs. Also, when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE had been completed, the odds that the PCP reported an FBSE also were higher. The relatively low medical record documentation of FBSEs highlights the need for more rigorous enforcement of accurate documentation. However, among the cases that were recorded, it appeared that the content of the examinations was more consistent.

Benefits of PCP-Led FBSEs

Although the USPSTF issued an I rating for PCP-led FBSEs,14 multiple national medical societies, including the American Cancer Society,25 American Academy of Dermatology,26 and Skin Cancer Foundation,27 as well as international guidelines in Germany,28 Australia,29,30 and New Zealand,31 recommend regular FBSEs among the general or at-risk population; New Zealand and Australia have the highest incidence and prevalence of melanoma in the world.8 The benefits of physician-led FBSEs on detection of early-stage skin cancer, and in particular, melanoma detection, have been documented in numerous studies.30,32-38 However, the variability and often poor quality of skin screening may contribute in part to the just as numerous null results from prior skin screening studies,15 perpetuating the insufficient status of skin examinations by USPSTF standards.14 Our study underscores both the variability in frequency and content of PCP-administered FBSEs. It also highlights the need for standardization of screening examinations at the medical student, trainee, and physician level.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, there was an unknown time lag between the FBSEs and physician self-reported surveys. Similarly, there was a variable time lag between the patient examination encounter and subsequent telephone survey. Both the physician and patient survey data may have been affected by recall bias. Second, patients were not asked directly whether an FBSE had been conducted. Furthermore, patients may not have appreciated whether the body part examined was part of the FBSE or another examination. Also, screenings often were not recorded in the medical record, assuming that the patient report and/or physician report was more accurate than the medical record.

Our study also was limited by demographics; our patient sample was largely comprised of White, educated, US adults, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Conversely, a notable strength of our study was that our participants were recruited from 4 geographically diverse centers. Furthermore, we had a comparatively large sample size of patients and physicians. Also, the independent assessment of provider-reported examinations, objective assessment of medical records, and patient reports of their encounters provides a strong foundation for assessing the independent contributions of each data source.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the challenges future studies face in promoting skin cancer screening in the primary care setting. Our findings underscore the need for a standardized FBSE as well as clear clinical expectations regarding skin cancer screening that is expected of PCPs.

As long as skin cancer screening rates remain low in the United States, patients will be subject to potential delays and missed diagnoses, impacting morbidity and mortality.8 There are burgeoning resources and efforts in place to increase skin cancer screening. For example, free validated online training is available for early detection of melanoma and other skin cancers (https://www.visualdx.com/skin-cancer-education/).39-42 Future directions for bolstering screening numbers must focus on educating PCPs about skin cancer prevention and perhaps narrowing the screening population by age-appropriate risk assessments.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Dourmishev LA, Rusinova D, Botev I. Clinical variants, stages, and management of basal cell carcinoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:12-17.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:243-251.

- Weinstock MA, Bogaars HA, Ashley M, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality. a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1194-1197.

- Matthews NH, Li W-Q, Qureshi AA, et al. Epidemiology of melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, eds. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy. Codon Publications; 2017:3-22.

- Cakir BO, Adamson P, Cingi C. Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20:419-422.

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187.

- Losina E, Walensky RP, Geller A, et al. Visual screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:21-28.

- Markova A, Weinstock MA, Risica P, et al. Effect of a web-based curriculum on primary care practice: basic skin cancer triage trial. Fam Med. 2013;45:558-568.

- Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Screening for skin cancer in adults: an updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. November 30, 2015. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review159/skin-cancer-screening2

- Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for skin cancer in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review forthe US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:436-447.

- LeBlanc WG, Vidal L, Kirsner RS, et al. Reported skin cancer screening of US adult workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:55-63.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Caralis PV, et al. Screening for skin cancer in primary care settings. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1423-1425.

- Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG. Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:564-566.

- Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Tobin DG, et al. Full-body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:530-534.

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp; 2015.

- Moore MM, Geller AC, Zhang Z, et al. Skin cancer examination teaching in US medical education. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:439-444.

- Wise E, Singh D, Moore M, et al. Rates of skin cancer screening and prevention counseling by US medical residents. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1131-1136.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am J Med. 2010;123:439-445.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer incidence rates. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer prevention. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/prevention-guidelines

- Katalinic A, Eisemann N, Waldmann A. Skin cancer screening in Germany. documenting melanoma incidence and mortality from 2008 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:629-634.

- Cancer Council Australia. Position statement: screening and early detection of skin cancer. Published July 2014. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://dermcoll.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PosStatEarlyDetectSkinCa.pdf

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice. 9th ed. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2016. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Redbook9/17048-Red-Book-9th-Edition.pdf

- Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network and New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney and New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington; 2008. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/melanoma-guideline-nov08-v2.pdf

- Swetter SM, Pollitt RA, Johnson TM, et al. Behavioral determinants of successful early melanoma detection: role of self and physician skin examination. Cancer. 2012;118:3725-3734.

- Terushkin V, Halpern AC. Melanoma early detection. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:481-500, viii.

- Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:450-458.

- Aitken JF, Elwood JM, Lowe JB, et al. A randomised trial of population screening for melanoma. J Med Screen. 2002;9:33-37.

- Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:201-211.

- Janda M, Lowe JB, Elwood M, et al. Do centralised skin screening clinics increase participation in melanoma screening (Australia)? Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:161-168.

- Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:105-114.

- Eide MJ, Asgari MM, Fletcher SW, et al. Effects on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:648-657.

- Weinstock MA, Ferris LK, Saul MI, et al. Downstream consequences of melanoma screening in a community practice setting: first results. Cancer. 2016;122:3152-3156.

- Matthews NH, Risica PM, Ferris LK, et al. Psychosocial impact of skin biopsies in the setting of melanoma screening: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:664-665.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics

The final sample included data from 53 physicians and 3343 patients. The study sample mean age (SD) was 50.3 (9.9) years for PCPs (n=53) and 59.8 (16.9) years for patients (n=3343). The physician sample was 36% female and predominantly White (83%). Ninety-one percent of the PCPs had an MD (the remaining had a DO degree), and the mean (SD) years practicing was 21.8 (10.6) years. Seventeen percent of PCPs were trained in internal medicine, 4% in internal medicine and pediatrics, and 79% family medicine; 79% of PCPs had received prior training in dermatology. The patient sample was 58% female, predominantly White (84%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (95%), had completed high school (94%), and earned more than $40,000 annually (66%).

Physician- and Patient-Reported FBSEs

Physicians reported performing FBSEs with variable frequency. Among PCPs who conducted FBSEs with greater frequency, there was a modest increase in the odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: odds ratio [OR], 24.5% [95% CI, 1.18-1.31; P<.001]; abdomen: OR, 23.3% [95% CI, 1.17-1.30; P<.001]; backs of legs: OR, 20.4% [95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P<.001])(Table 1). The patient-reported level of undress during examination was significantly associated with physician-reported FBSE (β=0.16 [95% CI, 0.13-0.18; P<.001])(Table 2).

Because of the bimodal distribution of scores in the physician-reported frequency of FBSEs, particularly pertaining to the extreme points of the scale, we further repeated analysis with only the never and almost always groups (Table 1). Primary care providers who reported almost always for FBSE had 29.6% increased odds of patient-reported back examination (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P=.048) and 59.3% increased odds of patient-reported abdomen examination (95% CI, 1.23-2.06; P<.001). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE were 56%, 40%, and 26%, respectively. The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE were 52%, 51%, and 30%, respectively. Raw percentages were calculated by dividing the number of "yes" responses by participants for each body part examined by thetotal number of participant responses (“yes” and “no”) for each respective body part. There was no significant change in odds of patient-reported backs of legs examined with PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE. In addition, a greater patient-reported level of undress was associated with 20.2% increased odds of PCPs reporting almost always conducting an FBSE (95% CI, 1.08-1.34; P=.001).

FBSEs in Patient Medical Records

When comparing PCP-reported FBSE and report of FBSE in patient medical records, there was a 39.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating FBSE when physicians reported conducting an FBSE with greater frequency (95% CI, 1.30-1.48; P<.001)(eTable 1). When examining PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE, a report of almost always was associated with 79.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating that an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.28-2.49; P=.001). The raw percentage of the patient medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE was 17% and 26% when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE.

When comparing the patient-reported body part examined with patient FBSE medical record documentation, an indication of yes for FBSE on the patient medical record was associated with a considerable increase in odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: 91.4% [95% CI, 1.59-2.31; P<.001]; abdomen: 75.0% [95% CI, 1.45-2.11; P<.001]; backs of legs: 91.6% [95% CI, 1.56-2.36; P<.001])(eTable 2). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined vs not examined when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE was completed were 24% vs 14%, 23% vs 15%, and 26% vs 16%, respectively. An increase in patient-reported level of undress was associated with a 57.0% increased odds of their medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.45-1.70; P<.001).

COMMENT How PCPs Perform FBSEs Varies

We found that PCPs performed FBSEs with variable frequency, and among those who did, the patient report of their examination varied considerably (Table 1). There appears to be considerable ambiguity in each of these means of determining the extent to which the skin was inspected for skin cancer, which may render the task of improving such inspection more difficult. We asked patients whether their back, abdomen, and backs of legs were examined as an assessment of some of the variety of areas inspected during an FBSE. During a general well-visit appointment, a patient’s back and abdomen may be examined for multiple reasons. Patients may have misinterpreted elements of the pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal, or musculoskeletal examinations as being part of the FBSE. The back and abdomen—the least specific features of the FBSE—were reported by patients to be the most often examined. Conversely, the backs of the legs—the most specific feature of the FBSE—had the lowest odds of being examined (Table 1).

In addition to the potential limitations of patient awareness of physician activity, our results also could be explained by differences among PCPs in how they performed FBSEs. There is no standardized method of conducting an FBSE. Furthermore, not all medical students and residents are exposed to dermatology training. In our sample of 53 physicians, 79% had reported receiving dermatology training; however, we did not assess the extent to which they had been trained in conducting an FBSE and/or identifying malignant lesions. In an American survey of 659 medical students, more than two-thirds of students had never been trained or never examined a patient for skin cancer.21 In another American survey of 342 internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology residents across 7 medical schools and 4 residency programs, more than three-quarters of residents had never been trained in skin cancer screening.22 Our findings reflect insufficient and inconsistent training in skin cancer screening and underscore the need for mandatory education to ensure quality FBSEs are performed in the primary care setting.

Frequency of PCPs Performing FBSEs

Similar to prior studies analyzing the frequency of FBSE performance in the primary care setting,16,19,23,24 more than half of our PCP sample reported sometimes to never conducting FBSEs. The percentage of physicians who reported conducting FBSEs in our sample was greater than the proportion reported by the National Health Interview Survey, in which only 8% of patients received an FBSE in the prior year by a PCP or obstetrician/gynecologist,16 but similar to a smaller patient study.19 In that study, 87% of patients, regardless of their skin cancer history, also reported that they would like their PCP to perform an FBSE regularly.19 Although some of our patient participants may have declined an FBSE, it is unlikely that that would have entirely accounted for the relatively low number of PCPs who reported frequently performing FBSEs.

Documentation in Medical Records of FBSEs

Compared to PCP self-reported performance of FBSEs, considerably fewer PCPs marked the patient medical record as having completed an FBSE. Among patients with medical records that indicated an FBSE had been conducted, they reported higher odds of all 3 body parts being examined, the highest being the backs of the legs. Also, when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE had been completed, the odds that the PCP reported an FBSE also were higher. The relatively low medical record documentation of FBSEs highlights the need for more rigorous enforcement of accurate documentation. However, among the cases that were recorded, it appeared that the content of the examinations was more consistent.

Benefits of PCP-Led FBSEs

Although the USPSTF issued an I rating for PCP-led FBSEs,14 multiple national medical societies, including the American Cancer Society,25 American Academy of Dermatology,26 and Skin Cancer Foundation,27 as well as international guidelines in Germany,28 Australia,29,30 and New Zealand,31 recommend regular FBSEs among the general or at-risk population; New Zealand and Australia have the highest incidence and prevalence of melanoma in the world.8 The benefits of physician-led FBSEs on detection of early-stage skin cancer, and in particular, melanoma detection, have been documented in numerous studies.30,32-38 However, the variability and often poor quality of skin screening may contribute in part to the just as numerous null results from prior skin screening studies,15 perpetuating the insufficient status of skin examinations by USPSTF standards.14 Our study underscores both the variability in frequency and content of PCP-administered FBSEs. It also highlights the need for standardization of screening examinations at the medical student, trainee, and physician level.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, there was an unknown time lag between the FBSEs and physician self-reported surveys. Similarly, there was a variable time lag between the patient examination encounter and subsequent telephone survey. Both the physician and patient survey data may have been affected by recall bias. Second, patients were not asked directly whether an FBSE had been conducted. Furthermore, patients may not have appreciated whether the body part examined was part of the FBSE or another examination. Also, screenings often were not recorded in the medical record, assuming that the patient report and/or physician report was more accurate than the medical record.

Our study also was limited by demographics; our patient sample was largely comprised of White, educated, US adults, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Conversely, a notable strength of our study was that our participants were recruited from 4 geographically diverse centers. Furthermore, we had a comparatively large sample size of patients and physicians. Also, the independent assessment of provider-reported examinations, objective assessment of medical records, and patient reports of their encounters provides a strong foundation for assessing the independent contributions of each data source.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the challenges future studies face in promoting skin cancer screening in the primary care setting. Our findings underscore the need for a standardized FBSE as well as clear clinical expectations regarding skin cancer screening that is expected of PCPs.

As long as skin cancer screening rates remain low in the United States, patients will be subject to potential delays and missed diagnoses, impacting morbidity and mortality.8 There are burgeoning resources and efforts in place to increase skin cancer screening. For example, free validated online training is available for early detection of melanoma and other skin cancers (https://www.visualdx.com/skin-cancer-education/).39-42 Future directions for bolstering screening numbers must focus on educating PCPs about skin cancer prevention and perhaps narrowing the screening population by age-appropriate risk assessments.

Keratinocyte carcinoma (KC), or nonmelanoma skin cancer, is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of all KCs.2,3 Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of KCs and accounting for the majority of KC-related deaths.4-7 Malignant melanoma represents the majority of all skin cancer–related deaths.8 The incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma in the United States is on the rise and carries substantial morbidity and mortality with notable social and economic burdens.1,8-10

Prevention is necessary to reduce skin cancer morbidity and mortality as well as rising treatment costs. The most commonly used skin cancer screening method among dermatologists is the visual full-body skin examination (FBSE), which is a noninvasive, safe, quick, and cost-effective method of early detection and prevention.11 To effectively confront the growing incidence and health care burden of skin cancer, primary care providers (PCPs) must join dermatologists in conducting FBSEs.12,13

Despite being the predominant means of secondary skin cancer prevention, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued an I rating for insufficient evidence to assess the benefits vs harms of screening the adult general population by PCPs.14,15 A major barrier to studying screening is the lack of a standardized method for conducting and reporting FBSEs.13 Systematic thorough skin examination generally is not performed in the primary care setting.16-18

We aimed to investigate what occurs during an FBSE in the primary care setting and how often they are performed. We examined whether there was potential variation in the execution of the examination, what was perceived by the patient vs reported by the physician, and what was ultimately included in the medical record. Miscommunication between patient and provider regarding performance of FBSEs has previously been noted,17-19 and we sought to characterize and quantify that miscommunication. We hypothesized that there would be lower patient-reported FBSEs compared to physicians and patient medical records. We also hypothesized that there would be variability in how physicians screened for skin cancer.

METHODS

This study was cross-sectional and was conducted based on interviews and a review of medical records at secondary- and tertiary-level units (clinics and hospitals) across the United States. We examined baseline data from a randomized controlled trial of a Web-based skin cancer early detection continuing education course—the Basic Skin Cancer Triage curriculum. Complete details have been described elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, and Brown University (all in Providence, Rhode Island), as well as those of all recruitment sites.

Data were collected from 2005 to 2008 and included physician online surveys, patient telephone interviews, and patient medical record data abstracted by research assistants. Primary care providers included in the study were general internists, family physicians, or medicine-pediatrics practitioners who were recruited from 4 collaborating centers across the United States in the mid-Atlantic region, Ohio, Kansas, and southern California, and who had been in practice for at least a year. Patients were recruited from participating physician practices and selected by research assistants who traveled to each clinic for coordination, recruitment, and performance of medical record reviews. Patients were selected as having minimal risk of melanoma (eg, no signs of severe photodamage to the skin). Patients completed structured telephone surveys within 1 to 2 weeks of the office visit regarding the practices observed and clinical questions asked during their recent clinical encounter with their PCP.

Measures

Demographics—Demographic variables asked of physicians included age, sex, ethnicity, academic degree (MD vs DO), years in practice, training, and prior dermatology training. Demographic information asked of patients included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and household income.

Physician-Reported Examination and Counseling Variables—Physicians were asked to characterize their clinical practices, prompted by questions regarding performance of FBSEs: “Please think of a typical month and using the scale below, indicate how frequently you perform a total body skin exam during an annual exam (eg, periodic follow-up exam).” Physicians responded to 3 questions on a 5-point scale (1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=about half, 4=often, 5=almost always).

Patient-Reported Examination Variables—Patients also were asked to characterize the skin examination experienced in their clinical encounter with their PCP, including: “During your last visit, as far as you could tell, did your physician: (1) look at the skin on your back? (2) look at the skin on your belly area? (3) look at the skin on the back of your legs?” Patient responses were coded as yes, no, don’t know, or refused. Participants who refused were excluded from analysis; participants who responded are detailed in Table 1. In addition, patients also reported the level of undress with their physician by answering the following question: “During your last medical exam, did you: 1=keep your clothes on; 2=partially undress; 3=totally undress except for undergarments; 4=totally undress, including all undergarments?”

Patient Medical Record–Extracted Data—Research assistants used a structured abstract form to extract the information from the patient’s medical record and graded it as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence) from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Logit/logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of patient-reported outcomes that were binary with physician-reported variables as the predictor. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the association between 2 continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM).20 Significance criterion was set at α of .05.

RESULTS Demographics

The final sample included data from 53 physicians and 3343 patients. The study sample mean age (SD) was 50.3 (9.9) years for PCPs (n=53) and 59.8 (16.9) years for patients (n=3343). The physician sample was 36% female and predominantly White (83%). Ninety-one percent of the PCPs had an MD (the remaining had a DO degree), and the mean (SD) years practicing was 21.8 (10.6) years. Seventeen percent of PCPs were trained in internal medicine, 4% in internal medicine and pediatrics, and 79% family medicine; 79% of PCPs had received prior training in dermatology. The patient sample was 58% female, predominantly White (84%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (95%), had completed high school (94%), and earned more than $40,000 annually (66%).

Physician- and Patient-Reported FBSEs

Physicians reported performing FBSEs with variable frequency. Among PCPs who conducted FBSEs with greater frequency, there was a modest increase in the odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: odds ratio [OR], 24.5% [95% CI, 1.18-1.31; P<.001]; abdomen: OR, 23.3% [95% CI, 1.17-1.30; P<.001]; backs of legs: OR, 20.4% [95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P<.001])(Table 1). The patient-reported level of undress during examination was significantly associated with physician-reported FBSE (β=0.16 [95% CI, 0.13-0.18; P<.001])(Table 2).

Because of the bimodal distribution of scores in the physician-reported frequency of FBSEs, particularly pertaining to the extreme points of the scale, we further repeated analysis with only the never and almost always groups (Table 1). Primary care providers who reported almost always for FBSE had 29.6% increased odds of patient-reported back examination (95% CI, 1.00-1.68; P=.048) and 59.3% increased odds of patient-reported abdomen examination (95% CI, 1.23-2.06; P<.001). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE were 56%, 40%, and 26%, respectively. The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE were 52%, 51%, and 30%, respectively. Raw percentages were calculated by dividing the number of "yes" responses by participants for each body part examined by thetotal number of participant responses (“yes” and “no”) for each respective body part. There was no significant change in odds of patient-reported backs of legs examined with PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE. In addition, a greater patient-reported level of undress was associated with 20.2% increased odds of PCPs reporting almost always conducting an FBSE (95% CI, 1.08-1.34; P=.001).

FBSEs in Patient Medical Records

When comparing PCP-reported FBSE and report of FBSE in patient medical records, there was a 39.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating FBSE when physicians reported conducting an FBSE with greater frequency (95% CI, 1.30-1.48; P<.001)(eTable 1). When examining PCP-reported never vs almost always conducting an FBSE, a report of almost always was associated with 79.0% increased odds of the patient medical record indicating that an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.28-2.49; P=.001). The raw percentage of the patient medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted when the PCP reported having never conducted an FBSE was 17% and 26% when the PCP reported having almost always conducted an FBSE.

When comparing the patient-reported body part examined with patient FBSE medical record documentation, an indication of yes for FBSE on the patient medical record was associated with a considerable increase in odds that patients reported a particular body part was examined (back: 91.4% [95% CI, 1.59-2.31; P<.001]; abdomen: 75.0% [95% CI, 1.45-2.11; P<.001]; backs of legs: 91.6% [95% CI, 1.56-2.36; P<.001])(eTable 2). The raw percentages of patients who reported having their back, abdomen, and backs of legs examined vs not examined when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE was completed were 24% vs 14%, 23% vs 15%, and 26% vs 16%, respectively. An increase in patient-reported level of undress was associated with a 57.0% increased odds of their medical record indicating an FBSE was conducted (95% CI, 1.45-1.70; P<.001).

COMMENT How PCPs Perform FBSEs Varies

We found that PCPs performed FBSEs with variable frequency, and among those who did, the patient report of their examination varied considerably (Table 1). There appears to be considerable ambiguity in each of these means of determining the extent to which the skin was inspected for skin cancer, which may render the task of improving such inspection more difficult. We asked patients whether their back, abdomen, and backs of legs were examined as an assessment of some of the variety of areas inspected during an FBSE. During a general well-visit appointment, a patient’s back and abdomen may be examined for multiple reasons. Patients may have misinterpreted elements of the pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal, or musculoskeletal examinations as being part of the FBSE. The back and abdomen—the least specific features of the FBSE—were reported by patients to be the most often examined. Conversely, the backs of the legs—the most specific feature of the FBSE—had the lowest odds of being examined (Table 1).

In addition to the potential limitations of patient awareness of physician activity, our results also could be explained by differences among PCPs in how they performed FBSEs. There is no standardized method of conducting an FBSE. Furthermore, not all medical students and residents are exposed to dermatology training. In our sample of 53 physicians, 79% had reported receiving dermatology training; however, we did not assess the extent to which they had been trained in conducting an FBSE and/or identifying malignant lesions. In an American survey of 659 medical students, more than two-thirds of students had never been trained or never examined a patient for skin cancer.21 In another American survey of 342 internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology residents across 7 medical schools and 4 residency programs, more than three-quarters of residents had never been trained in skin cancer screening.22 Our findings reflect insufficient and inconsistent training in skin cancer screening and underscore the need for mandatory education to ensure quality FBSEs are performed in the primary care setting.

Frequency of PCPs Performing FBSEs

Similar to prior studies analyzing the frequency of FBSE performance in the primary care setting,16,19,23,24 more than half of our PCP sample reported sometimes to never conducting FBSEs. The percentage of physicians who reported conducting FBSEs in our sample was greater than the proportion reported by the National Health Interview Survey, in which only 8% of patients received an FBSE in the prior year by a PCP or obstetrician/gynecologist,16 but similar to a smaller patient study.19 In that study, 87% of patients, regardless of their skin cancer history, also reported that they would like their PCP to perform an FBSE regularly.19 Although some of our patient participants may have declined an FBSE, it is unlikely that that would have entirely accounted for the relatively low number of PCPs who reported frequently performing FBSEs.

Documentation in Medical Records of FBSEs

Compared to PCP self-reported performance of FBSEs, considerably fewer PCPs marked the patient medical record as having completed an FBSE. Among patients with medical records that indicated an FBSE had been conducted, they reported higher odds of all 3 body parts being examined, the highest being the backs of the legs. Also, when the patient medical record indicated an FBSE had been completed, the odds that the PCP reported an FBSE also were higher. The relatively low medical record documentation of FBSEs highlights the need for more rigorous enforcement of accurate documentation. However, among the cases that were recorded, it appeared that the content of the examinations was more consistent.

Benefits of PCP-Led FBSEs

Although the USPSTF issued an I rating for PCP-led FBSEs,14 multiple national medical societies, including the American Cancer Society,25 American Academy of Dermatology,26 and Skin Cancer Foundation,27 as well as international guidelines in Germany,28 Australia,29,30 and New Zealand,31 recommend regular FBSEs among the general or at-risk population; New Zealand and Australia have the highest incidence and prevalence of melanoma in the world.8 The benefits of physician-led FBSEs on detection of early-stage skin cancer, and in particular, melanoma detection, have been documented in numerous studies.30,32-38 However, the variability and often poor quality of skin screening may contribute in part to the just as numerous null results from prior skin screening studies,15 perpetuating the insufficient status of skin examinations by USPSTF standards.14 Our study underscores both the variability in frequency and content of PCP-administered FBSEs. It also highlights the need for standardization of screening examinations at the medical student, trainee, and physician level.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, there was an unknown time lag between the FBSEs and physician self-reported surveys. Similarly, there was a variable time lag between the patient examination encounter and subsequent telephone survey. Both the physician and patient survey data may have been affected by recall bias. Second, patients were not asked directly whether an FBSE had been conducted. Furthermore, patients may not have appreciated whether the body part examined was part of the FBSE or another examination. Also, screenings often were not recorded in the medical record, assuming that the patient report and/or physician report was more accurate than the medical record.

Our study also was limited by demographics; our patient sample was largely comprised of White, educated, US adults, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Conversely, a notable strength of our study was that our participants were recruited from 4 geographically diverse centers. Furthermore, we had a comparatively large sample size of patients and physicians. Also, the independent assessment of provider-reported examinations, objective assessment of medical records, and patient reports of their encounters provides a strong foundation for assessing the independent contributions of each data source.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the challenges future studies face in promoting skin cancer screening in the primary care setting. Our findings underscore the need for a standardized FBSE as well as clear clinical expectations regarding skin cancer screening that is expected of PCPs.

As long as skin cancer screening rates remain low in the United States, patients will be subject to potential delays and missed diagnoses, impacting morbidity and mortality.8 There are burgeoning resources and efforts in place to increase skin cancer screening. For example, free validated online training is available for early detection of melanoma and other skin cancers (https://www.visualdx.com/skin-cancer-education/).39-42 Future directions for bolstering screening numbers must focus on educating PCPs about skin cancer prevention and perhaps narrowing the screening population by age-appropriate risk assessments.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Dourmishev LA, Rusinova D, Botev I. Clinical variants, stages, and management of basal cell carcinoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:12-17.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:243-251.

- Weinstock MA, Bogaars HA, Ashley M, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality. a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1194-1197.

- Matthews NH, Li W-Q, Qureshi AA, et al. Epidemiology of melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, eds. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy. Codon Publications; 2017:3-22.

- Cakir BO, Adamson P, Cingi C. Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20:419-422.

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187.

- Losina E, Walensky RP, Geller A, et al. Visual screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:21-28.

- Markova A, Weinstock MA, Risica P, et al. Effect of a web-based curriculum on primary care practice: basic skin cancer triage trial. Fam Med. 2013;45:558-568.

- Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Screening for skin cancer in adults: an updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. November 30, 2015. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review159/skin-cancer-screening2

- Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for skin cancer in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review forthe US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:436-447.

- LeBlanc WG, Vidal L, Kirsner RS, et al. Reported skin cancer screening of US adult workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:55-63.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Caralis PV, et al. Screening for skin cancer in primary care settings. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1423-1425.

- Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG. Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:564-566.

- Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Tobin DG, et al. Full-body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:530-534.

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp; 2015.

- Moore MM, Geller AC, Zhang Z, et al. Skin cancer examination teaching in US medical education. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:439-444.

- Wise E, Singh D, Moore M, et al. Rates of skin cancer screening and prevention counseling by US medical residents. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1131-1136.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am J Med. 2010;123:439-445.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer incidence rates. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer prevention. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/prevention-guidelines

- Katalinic A, Eisemann N, Waldmann A. Skin cancer screening in Germany. documenting melanoma incidence and mortality from 2008 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:629-634.

- Cancer Council Australia. Position statement: screening and early detection of skin cancer. Published July 2014. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://dermcoll.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PosStatEarlyDetectSkinCa.pdf

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice. 9th ed. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2016. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Redbook9/17048-Red-Book-9th-Edition.pdf

- Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network and New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney and New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington; 2008. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/melanoma-guideline-nov08-v2.pdf

- Swetter SM, Pollitt RA, Johnson TM, et al. Behavioral determinants of successful early melanoma detection: role of self and physician skin examination. Cancer. 2012;118:3725-3734.

- Terushkin V, Halpern AC. Melanoma early detection. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:481-500, viii.

- Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:450-458.

- Aitken JF, Elwood JM, Lowe JB, et al. A randomised trial of population screening for melanoma. J Med Screen. 2002;9:33-37.

- Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:201-211.

- Janda M, Lowe JB, Elwood M, et al. Do centralised skin screening clinics increase participation in melanoma screening (Australia)? Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:161-168.

- Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:105-114.

- Eide MJ, Asgari MM, Fletcher SW, et al. Effects on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:648-657.

- Weinstock MA, Ferris LK, Saul MI, et al. Downstream consequences of melanoma screening in a community practice setting: first results. Cancer. 2016;122:3152-3156.

- Matthews NH, Risica PM, Ferris LK, et al. Psychosocial impact of skin biopsies in the setting of melanoma screening: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:664-665.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Dourmishev LA, Rusinova D, Botev I. Clinical variants, stages, and management of basal cell carcinoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:12-17.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:243-251.

- Weinstock MA, Bogaars HA, Ashley M, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality. a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1194-1197.

- Matthews NH, Li W-Q, Qureshi AA, et al. Epidemiology of melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, eds. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy. Codon Publications; 2017:3-22.

- Cakir BO, Adamson P, Cingi C. Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20:419-422.

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187.

- Losina E, Walensky RP, Geller A, et al. Visual screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:21-28.

- Markova A, Weinstock MA, Risica P, et al. Effect of a web-based curriculum on primary care practice: basic skin cancer triage trial. Fam Med. 2013;45:558-568.

- Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Screening for skin cancer in adults: an updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. November 30, 2015. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review159/skin-cancer-screening2

- Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for skin cancer in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review forthe US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:436-447.

- LeBlanc WG, Vidal L, Kirsner RS, et al. Reported skin cancer screening of US adult workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:55-63.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Caralis PV, et al. Screening for skin cancer in primary care settings. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1423-1425.

- Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG. Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:564-566.

- Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Tobin DG, et al. Full-body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:530-534.

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp; 2015.

- Moore MM, Geller AC, Zhang Z, et al. Skin cancer examination teaching in US medical education. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:439-444.

- Wise E, Singh D, Moore M, et al. Rates of skin cancer screening and prevention counseling by US medical residents. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1131-1136.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am J Med. 2010;123:439-445.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer incidence rates. Updated April 22, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer prevention. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/prevention-guidelines

- Katalinic A, Eisemann N, Waldmann A. Skin cancer screening in Germany. documenting melanoma incidence and mortality from 2008 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:629-634.

- Cancer Council Australia. Position statement: screening and early detection of skin cancer. Published July 2014. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://dermcoll.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PosStatEarlyDetectSkinCa.pdf

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice. 9th ed. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2016. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Redbook9/17048-Red-Book-9th-Edition.pdf

- Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network and New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney and New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington; 2008. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/melanoma-guideline-nov08-v2.pdf

- Swetter SM, Pollitt RA, Johnson TM, et al. Behavioral determinants of successful early melanoma detection: role of self and physician skin examination. Cancer. 2012;118:3725-3734.

- Terushkin V, Halpern AC. Melanoma early detection. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:481-500, viii.

- Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:450-458.

- Aitken JF, Elwood JM, Lowe JB, et al. A randomised trial of population screening for melanoma. J Med Screen. 2002;9:33-37.

- Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:201-211.

- Janda M, Lowe JB, Elwood M, et al. Do centralised skin screening clinics increase participation in melanoma screening (Australia)? Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:161-168.

- Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:105-114.

- Eide MJ, Asgari MM, Fletcher SW, et al. Effects on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:648-657.

- Weinstock MA, Ferris LK, Saul MI, et al. Downstream consequences of melanoma screening in a community practice setting: first results. Cancer. 2016;122:3152-3156.

- Matthews NH, Risica PM, Ferris LK, et al. Psychosocial impact of skin biopsies in the setting of melanoma screening: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:664-665.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists should be aware of the variability in practice and execution of full-body skin examinations (FBSEs) among primary care providers and offer comprehensive examinations for every patient.

- Variability in reporting and execution of FBSEs may impact the continued US Preventive Services Task Force I rating in their guidelines and promotion of skin cancer screening in the primary care setting.

Devices to detect skin cancer: FDA advisers offer mixed views

.

So far, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has cleared two devices. Both are computer-aided skin lesion classification devices meant to help clinicians assess cases of suspected melanoma.

Both were given a class III designation. That classification is intended for products that are considered to have a high risk of harm because of flawed design or implementation. Many such devices are under development, and there has been a proposal to include these devices in class II, which is less restrictive.

The FDA turned to one of its expert panels for advice. At a meeting held on Aug. 29, experts on the panel offered differing views and expressed concerns about the accuracy of these devices.

This was the second day of meetings of the general and plastic surgery devices panel of the FDA’s Medical Devices Advisory Committee. On the previous day, the panel held a wide-ranging discussion about expanding use of skin lesion analyzer devices.

The FDA sought the expert panel’s advice concerning a field that appears to be heating up quickly after relatively quiet times.

Two devices have been approved by the FDA so far, but only one is still being promoted – SciBase AB’s Nevisense. The Swedish company announced in May 2020 that it had received FDA approval for Nevisense 3.0, the third generation of their Nevisense system for early melanoma detection, an AI-based point-of-care system for the noninvasive evaluation of irregular moles.

The other device, known as MelaFind, was acquired by Strata Skin Sciences, but the company said in 2017 that it discontinued research and development, sales, and support activity related to the device, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

But there’s been a swell in recent years in the number of publications related to the use of AI and machine learning, which could give rise to new tools for aiding in the diagnosis of skin conditions, including cancer. Google is among the companies that are involved in these efforts.

So, the FDA asked the expert panel to discuss a series of questions related to how the agency should weigh the risks of computer-aided devices for melanoma diagnosis. The agency also asked the panel to provide feedback about how well risks associated with such devices and tools might be managed and to offer suggestions.

The discussion at the July 29 meeting spun beyond narrow questions about reclassification of the current class III devices to topics involving emerging technology, such as efforts to apply AI to dermatology.

“Innovation continues. Medical device developers are anxious to plan how they might be able to develop the level of evidence that would meet your expectations” for future products, Binita Ashar, MD, a senior official in FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, told the panel.

Company CEO backs tougher regulation