User login

Atrial Fibrillation and Bleeding in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treated with Ibrutinib in the Veterans Health Administration (FULL)

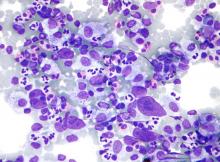

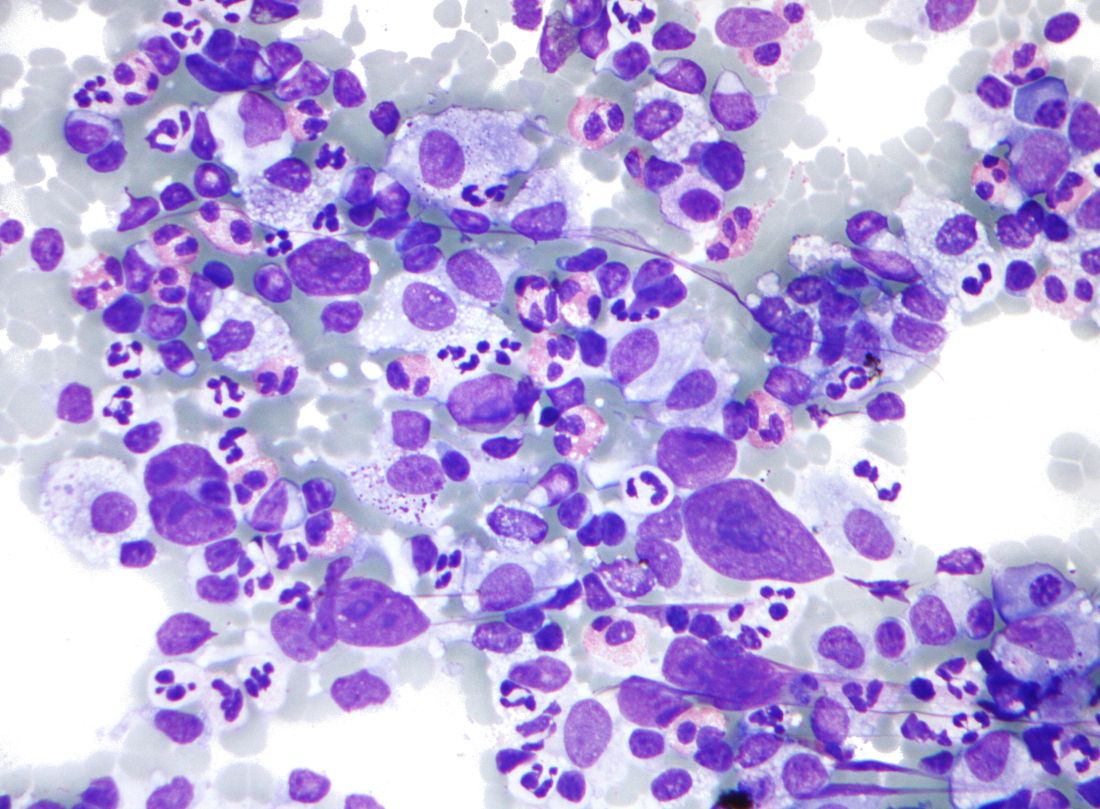

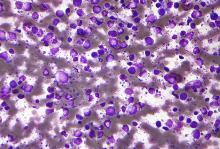

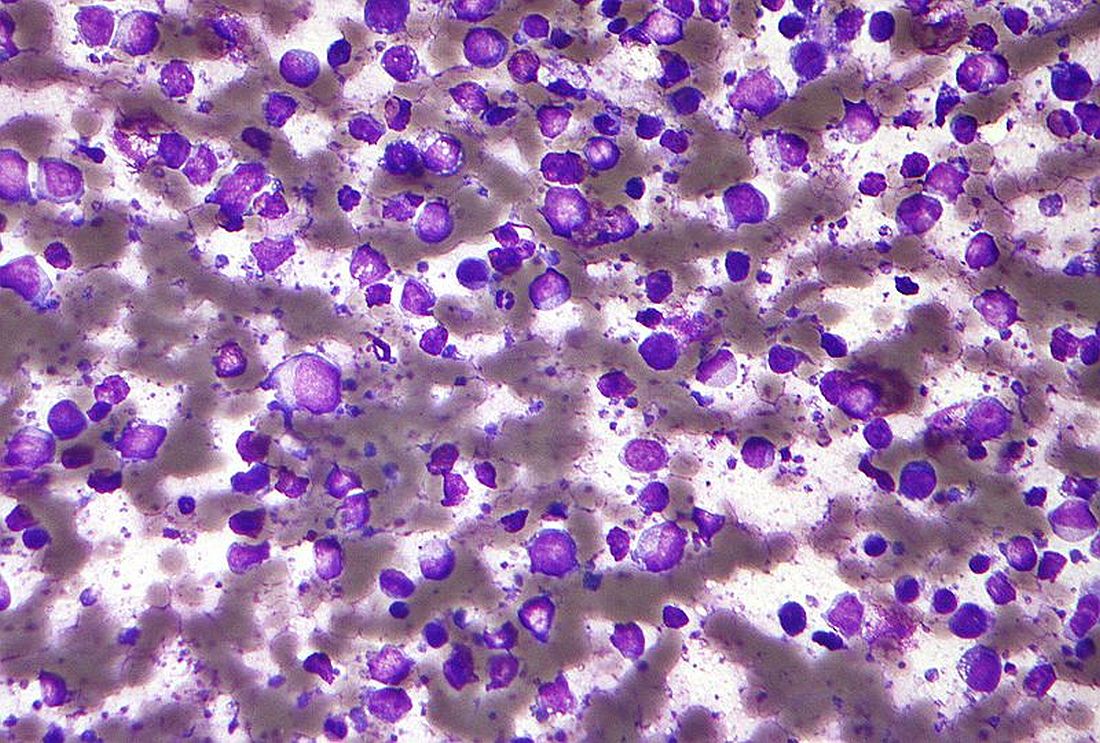

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia diagnosed in developed countries, with an estimated 21,040 new diagnoses of CLL expected in the US in 2020. 1-3 CLL is an indolent cancer characterized by the accumulation of B-lymphocytes in the blood, marrow, and lymphoid tissues. 4 It has a heterogeneous clinical course; the majority of patients are observed or receive delayed treatment following diagnosis, while a minority of patients require immediate treatment. After first-line treatment, some patients experience prolonged remissions while others require retreatment within 1 or 2 years. Fortunately, advances in cancer biology and therapeutics in the last decade have increased the number of treatment options available for patients with CLL.

Until recently, most CLL treatments relied on a chemotherapy or a chemoimmunotherapy backbone; however, the last few years have seen novel therapies introduced, such as small molecule inhibitors to target molecular pathways that promote the normal development, expansion, and survival of B-cells.5 One such therapy is ibrutinib, a targeted Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2014 for patients with CLL who received at least 1 prior therapy. The FDA later expanded this approval to include use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL with relapsed or refractory disease, with or without chromosome 17p deletion. In 2016, based on data from the RESONATE-17 study, the FDA approved ibrutinib for first-line therapy in patients with CLL.6

Ibrutinib’s efficacy, ease of administration and dosing (all doses are oral and fixed, rather than based on weight or body surface area), and relatively favorable safety profile have resulted in a rapid growth in its adoption.7 Since its adverse event (AE) profile is generally more tolerable than that of a typical chemoimmunotherapy, its use in older patients with CLL and patients with significant comorbidities is particularly appealing.8

However, the results of some clinical trials suggest an association between treatment with ibrutinib and an increased risk of bleeding-related events of any grade (44%) and major bleeding events (4%).7,8 The incidence of major bleeding events was reported to be higher (9%) in one clinical trial and at 5-year follow-up, although this trial did not exclude patients receiving concomitant oral anticoagulation with warfarin.6,9

Heterogeneity in clinical trials’ definitions of major bleeding confounded the ability to calculate bleeding risk in patients treated with ibrutinib in a systematic review and meta-analysis that called for more data.10 Additionally, patients with factors that might increase the risk of major bleeding with ibrutinib treatment were likely underrepresented in clinical trials, given the carefully selected nature of clinical trial subjects. These factors include renal or hepatic disease, gastrointestinal disease, and use of a number of concomitant medications such as antiplatelets or anticoagulant medications. Accounting for use of the latter is particularly important because patients who develop atrial fibrillation (Afib), one of the recognized AEs of treatment with ibrutinib, often are treated with anticoagulant medications in order to decrease the risk of stroke or other thromboembolic complications.

A single-site observational study of patients treated with ibrutinib reported a high utilization rate of antiplatelet medications (70%), anticoagulant medications (17%), or both (13%) with a concomitant major bleeding rate of 18% of patients.11 Prevalence of bleeding events seemed to be highly affected by the presence of concomitant medications: 78% of patients treated with ibrutinib while concurrently receiving both antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications developed a major bleeding event, while none of the patients who were not receiving antiplatelets, anticoagulants, or medications that interact with cytochrome P450 (an enzyme that metabolized chemotherapeutic agents used to treat cancer) experienced a major bleeding event.11

The prevalence of major bleeding events, comorbidities, and utilization of medications that could increase the risk of major bleeding in patients with CLL on ibrutinib in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is not known. The VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the US. To address these knowledge gaps, a retrospective observational study was conducted using data on demographics, comorbidities that could affect bleeding, use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications, and bleeding events in patients with CLL who were treated in the first year of ibrutinib availability from the VHA.

The first year of ibrutinib availability was chosen for this study since we anticipated that many health care providers would be unfamiliar with ibrutinib during that time given its novelty, and therefore more likely to codispense ibrutinib with medications that could increase the risk of a bleeding event. Since Afib is both an AE associated with ibrutinib treatment and a condition that often is treated with anticoagulants, the prevalence of Afib in this population was also included. For context, the incidence of bleeding and Afib and use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications during treatment in a cohort of patients with CLL treated with bendamustine + rituximab (BR) also was reported.

Methods

The VHA maintains the centralized US Department of Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry System (VACRS), with electronic medical record data and other sources captured in its Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The VHA CDW is a national repository comprising data from several VHA clinical and administrative systems. The CDW includes patient identifiers; demographics; vital status; lab information; administrative information (such as diagnostic International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-9] codes); medication dispensation tables (such as outpatient fill); IV package information; and notes from radiology, pathology, outpatient and inpatient admission, discharge, and daily progress.

Registrars abstract all cancer cases within the VHA system (or diagnosed outside the VHA, if patients subsequently receive treatment in the VHA). It is estimated that VACRS captures 3% of cancer cases in the US.12 Like most registries, VACRS captures data such as diagnosis, age, gender, race, and vital status.

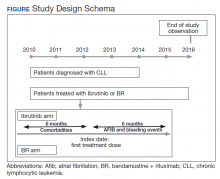

The study received approval from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and used individual patient-level historical administrative, cancer registry, and electronic health care record data. Patients diagnosed and treated for CLL at the VHA from 2010 to 2014 were identified through the VACRS and CDW; patients with a prior malignancy were excluded. Patients who received ibrutinib or BR based on pharmacy dispensation information were selected. Patients were followed until December 31, 2016 or death; patients with documentation of another cancer or lack of utilization of the VHA hematology or oncology services (defined as absence of any hematology and/or oncology clinic visits for ≥ 18 months) were omitted from the final analysis (Figure).

Previous and concomitant utilization of antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel) or anticoagulant (dalteparin, enoxaparin, fondaparinux, heparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin) medications was extracted 6 months before and after the first dispensation of ibrutinib or BR using pharmacy dispensation records.

Study Definitions

Prevalence of comorbidities that could increase bleeding risk was determined using administrative ICD-9-CM codes. Liver disease was identified by presence of cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus, or alcoholic liver disease using administrative codes validated by Kramer and colleagues, who reported positive and negative predictive values of 90% and 87% for cirrhosis, 93% and 92% for hepatitis C virus, and 71% and 98% for alcoholic liver disease.13 Similarly, end-stage liver disease was identified using a validated coding algorithm developed by Goldberg and colleagues, with a positive predictive value of 89.3%.14 The presence of controlled or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM) was identified using the procedure described by Guzman and colleagues.15 Quan’s algorithm was used to calculate Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on ICD-9-CM codes for inpatient and outpatient visits within a 6-month lookback period prior to treatment initiation.16

A major bleeding event was defined as a hospitalization with an ICD-9-CM code suggestive of major bleeding as the primary reason, as defined by Lane and colleagues in their study of major bleeding related to warfarin in a cohort of patients treated within the VHA.17 Incidence rates of major bleeding events were identified during the first 6 months of treatment. Incidence of Afib—defined as an inpatient or outpatient encounter with the 427.31 ICD-9-CM code—also was examined within the first 6 months after starting treatment. The period of 6 months was chosen because bendamustine must be discontinued after 6 months.

Study Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine patient demographics, disease characteristics, and treatment history from initial CLL diagnosis through end of study observation period. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and accompanying proportions, while a mean and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous variables. For the means of continuous variables and of categorical data, 95% CIs were used. Proportions and accompanying 95% CIs characterized treatment patterns, including line of therapy, comorbidities, and bleeding events. Treatment duration was described using mean and accompanying 95% CI. Statistical tests were not conducted for comparisons among treatment groups. Patients were censored at the end of follow-up, defined as the earliest of the following scenarios: (1) end of study observation period (December 31, 2016); (2) development of a secondary cancer; or (3) last day of contact given absence of care within the VHA for ≥ 18 months (with care defined as oncology and/or oncology/hematology visit with an associated note). Analysis was performed using R 3.4.0.

Results

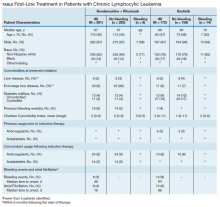

Between 2010 and 2014, 2,796 patients were diagnosed and received care for CLL within the VHA. Overall, all 172 patients who were treated with ibrutinib during our inclusion period were selected. These patients were treated between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016, following ibrutinib’s approval in early 2014. An additional 291 patients were selected who received BR (Table). Reflecting the predominantly male population of the VHA, 282 (97%) BR patients and 167 (97%) ibrutinib patients were male. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years for BR patients and 69 years for ibrutinib patients. About 76% of patients who received ibrutinib and 82% of patients who received BR were non-Hispanic white; 17% and 14% were African American, respectively.

Less than 10% of patients receiving either ibrutinib or BR had liver disease per criteria used by Kramer and colleagues, or end-stage liver disease using criteria developed by Goldberg and colleagues.12,13 About 5% of patients had a history of previous bleeding in the 6-month period prior to initiating either therapy. Mean CCI (excluding malignancy) score was 1.5 (range, 0-11) for the ibrutinib group, and 2.1 (range, 0-9) for the BR group. About 16% of the ibrutinib group had controlled DM and fewer than 10% had uncontrolled DM, while 4% of patients in the BR group met the criteria for controlled DM and another 4% met the criteria for uncontrolled DM.

There was very low utilization of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication prior to initiation of ibrutinib (2.9% and 2.3%, respectively) or BR (< 1% each). In the first 6 months after treatment initiation, about 8% of patients in both ibrutinib and BR cohorts received anticoagulant medication while antiplatelet utilization was < 5% in either group.

In the BR group, 8 patients (2.7%) experienced a major bleeding event, while 14 patients (8.1%) in the ibrutinib group experienced a bleeding event (P = .008). While these numbers were too low to perform a formal statistical analysis of the association between clinical covariates and bleeding in either group, there did not seem to be an association between bleeding and liver disease or DM. Of patients who experienced a bleeding event, about 1 in 4 patients had had a prior bleeding event in both the ibrutinib and the BR groups. Interestingly, while none of the patients who experienced a bleeding event while receiving BR were taking concomitant anticoagulant medication, 3 of the 14 patients who experienced a bleeding event in the ibrutinib group showed evidence of anticoagulant utilization. Finally, the incidence of Afib (defined as patients with no evidence of Afib in the 6 months prior to treatment but with evidence of Afib in the 6 months following treatment initiation) was 4% in the BR group, and about 8% in the ibrutinib group (P = .003).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to examine the real-world incidence of bleeding and Afib in veterans who received ibrutinib for CLL in the first year of its availability. The study found minimal use of anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet agents prior to receiving first-line ibrutinib or BR, and very low use of these agents in the first 6 months following the initiation of first-line treatment. This finding suggests a high awareness among VA providers of potential adverse effects (AEs) of ibrutinib and chemotherapy, and a careful selection of patients that lack risk factors for AEs.

In patients treated with first-line ibrutinib when compared with patients treated with first-line BR, moderate increases in bleeding (2.7% vs 8.1%, P = .008) and Afib (10.5% vs 3%, P = .003) also were observed. These results are concordant with previous findings examining the use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL.18-20

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as some limitations must be considered. The study was conducted in the early days of ibrutinib adoption. Since then, more patients have been treated with ibrutinib and for longer durations. As clinicians gain more familiarity and with ibrutinib, and as additional novel therapeutics emerge, it is possible that the initial awareness about risks for possible AEs may diminish; patients with high comorbidity burdens and concomitant medications would be especially vulnerable in cases of reduced physician vigilance.

Another limitation of this study stems from the potential for dual system use among patients treated in the VHA. Concurrent or alternating use of multiple health care systems (use of VHA and private-sector facilities) may present gaps in the reconstruction of patient histories, resulting in missing data as patients transition between commercial, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and VHA care. As a result, the results presented here do not reflect instances where a patient experienced a bleeding event treated outside the VA.

Problems with missing data also may occur due to incomplete extraction from the electronic health record; these issues were addressed by leveraging an understanding of the multiple data marts within the CDW environment to harmonize missing and/or erroneous information through use of other data marts when possible. Lastly, this research represents a population-level study of the VHA, thus all findings are directly relevant to the VHA. The generalizability of the findings outside the VHA would depend on the characteristics of the external population.

Conclusion

Real-world evidence from a nationwide cohort of veteran patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib suggest that, while there is an association of increased bleeding-related events and Afib, the risk is comparable to those reported in previous studies.18-20 These findings suggest that patients in real-world clinical care settings with higher levels of comorbidities may be at a slight increased risk for bleeding events and Afib.

1. Scarfò L, Ferreri AJ, Ghia P. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:169-182.

2. Devereux S, Cuthill K. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;45(5):292-296.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2020.

4. Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:16096.

5. Owen C, Assouline S, Kuruvilla J, Uchida C, Bellingham C, Sehn L. Novel therapies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a Canadian perspective. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(11):627-634.e5.

6. O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1409–1418.

7. Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425-2437.

8. Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42.

9. O’Brien S, Furman R, Coutre S, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131(17):1910-1919.

10. Caron F, Leong DP, Hillis C, Fraser G, Siegal D. Current understanding of bleeding with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2017;1(12):772-778.

11. Kunk PR, Mock J, Devitt ME, Palkimas S, et al. Major bleeding with ibrutinib: more than expected. Blood. 2016;128(22):3229.

12. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

13. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274-282.

14. Goldberg D, Lewis JD, Halpern SD, Weiner M, Lo Re V 3rd. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(7):765-769.

15. Guzman JZ, Iatridis JC, Skovrlj B, et al. Outcomes and complications of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing degenerative lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(19):1596-1604.

16. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

17. Lane MA, Zeringue A, McDonald JR. Serious bleeding events due to warfarin and antibiotic co-prescription in a cohort of veterans. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):657–663.e2.

18. Leong DP, Caron F, Hillis C, et al. The risk of atrial fibrillation with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2016;128(1):138-140.

19. Lipsky AH, Farooqui MZ, Tian X, et al. Incidence and risk factors of bleeding-related adverse events in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Haematologica. 2015;100(12):1571-1578.

20. Brown JR, Moslehi J, O’Brien S, et al. Characterization of atrial fibrillation adverse events reported in ibrutinib randomized controlled registration trials. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1796-1805.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia diagnosed in developed countries, with an estimated 21,040 new diagnoses of CLL expected in the US in 2020. 1-3 CLL is an indolent cancer characterized by the accumulation of B-lymphocytes in the blood, marrow, and lymphoid tissues. 4 It has a heterogeneous clinical course; the majority of patients are observed or receive delayed treatment following diagnosis, while a minority of patients require immediate treatment. After first-line treatment, some patients experience prolonged remissions while others require retreatment within 1 or 2 years. Fortunately, advances in cancer biology and therapeutics in the last decade have increased the number of treatment options available for patients with CLL.

Until recently, most CLL treatments relied on a chemotherapy or a chemoimmunotherapy backbone; however, the last few years have seen novel therapies introduced, such as small molecule inhibitors to target molecular pathways that promote the normal development, expansion, and survival of B-cells.5 One such therapy is ibrutinib, a targeted Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2014 for patients with CLL who received at least 1 prior therapy. The FDA later expanded this approval to include use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL with relapsed or refractory disease, with or without chromosome 17p deletion. In 2016, based on data from the RESONATE-17 study, the FDA approved ibrutinib for first-line therapy in patients with CLL.6

Ibrutinib’s efficacy, ease of administration and dosing (all doses are oral and fixed, rather than based on weight or body surface area), and relatively favorable safety profile have resulted in a rapid growth in its adoption.7 Since its adverse event (AE) profile is generally more tolerable than that of a typical chemoimmunotherapy, its use in older patients with CLL and patients with significant comorbidities is particularly appealing.8

However, the results of some clinical trials suggest an association between treatment with ibrutinib and an increased risk of bleeding-related events of any grade (44%) and major bleeding events (4%).7,8 The incidence of major bleeding events was reported to be higher (9%) in one clinical trial and at 5-year follow-up, although this trial did not exclude patients receiving concomitant oral anticoagulation with warfarin.6,9

Heterogeneity in clinical trials’ definitions of major bleeding confounded the ability to calculate bleeding risk in patients treated with ibrutinib in a systematic review and meta-analysis that called for more data.10 Additionally, patients with factors that might increase the risk of major bleeding with ibrutinib treatment were likely underrepresented in clinical trials, given the carefully selected nature of clinical trial subjects. These factors include renal or hepatic disease, gastrointestinal disease, and use of a number of concomitant medications such as antiplatelets or anticoagulant medications. Accounting for use of the latter is particularly important because patients who develop atrial fibrillation (Afib), one of the recognized AEs of treatment with ibrutinib, often are treated with anticoagulant medications in order to decrease the risk of stroke or other thromboembolic complications.

A single-site observational study of patients treated with ibrutinib reported a high utilization rate of antiplatelet medications (70%), anticoagulant medications (17%), or both (13%) with a concomitant major bleeding rate of 18% of patients.11 Prevalence of bleeding events seemed to be highly affected by the presence of concomitant medications: 78% of patients treated with ibrutinib while concurrently receiving both antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications developed a major bleeding event, while none of the patients who were not receiving antiplatelets, anticoagulants, or medications that interact with cytochrome P450 (an enzyme that metabolized chemotherapeutic agents used to treat cancer) experienced a major bleeding event.11

The prevalence of major bleeding events, comorbidities, and utilization of medications that could increase the risk of major bleeding in patients with CLL on ibrutinib in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is not known. The VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the US. To address these knowledge gaps, a retrospective observational study was conducted using data on demographics, comorbidities that could affect bleeding, use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications, and bleeding events in patients with CLL who were treated in the first year of ibrutinib availability from the VHA.

The first year of ibrutinib availability was chosen for this study since we anticipated that many health care providers would be unfamiliar with ibrutinib during that time given its novelty, and therefore more likely to codispense ibrutinib with medications that could increase the risk of a bleeding event. Since Afib is both an AE associated with ibrutinib treatment and a condition that often is treated with anticoagulants, the prevalence of Afib in this population was also included. For context, the incidence of bleeding and Afib and use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications during treatment in a cohort of patients with CLL treated with bendamustine + rituximab (BR) also was reported.

Methods

The VHA maintains the centralized US Department of Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry System (VACRS), with electronic medical record data and other sources captured in its Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The VHA CDW is a national repository comprising data from several VHA clinical and administrative systems. The CDW includes patient identifiers; demographics; vital status; lab information; administrative information (such as diagnostic International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-9] codes); medication dispensation tables (such as outpatient fill); IV package information; and notes from radiology, pathology, outpatient and inpatient admission, discharge, and daily progress.

Registrars abstract all cancer cases within the VHA system (or diagnosed outside the VHA, if patients subsequently receive treatment in the VHA). It is estimated that VACRS captures 3% of cancer cases in the US.12 Like most registries, VACRS captures data such as diagnosis, age, gender, race, and vital status.

The study received approval from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and used individual patient-level historical administrative, cancer registry, and electronic health care record data. Patients diagnosed and treated for CLL at the VHA from 2010 to 2014 were identified through the VACRS and CDW; patients with a prior malignancy were excluded. Patients who received ibrutinib or BR based on pharmacy dispensation information were selected. Patients were followed until December 31, 2016 or death; patients with documentation of another cancer or lack of utilization of the VHA hematology or oncology services (defined as absence of any hematology and/or oncology clinic visits for ≥ 18 months) were omitted from the final analysis (Figure).

Previous and concomitant utilization of antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel) or anticoagulant (dalteparin, enoxaparin, fondaparinux, heparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin) medications was extracted 6 months before and after the first dispensation of ibrutinib or BR using pharmacy dispensation records.

Study Definitions

Prevalence of comorbidities that could increase bleeding risk was determined using administrative ICD-9-CM codes. Liver disease was identified by presence of cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus, or alcoholic liver disease using administrative codes validated by Kramer and colleagues, who reported positive and negative predictive values of 90% and 87% for cirrhosis, 93% and 92% for hepatitis C virus, and 71% and 98% for alcoholic liver disease.13 Similarly, end-stage liver disease was identified using a validated coding algorithm developed by Goldberg and colleagues, with a positive predictive value of 89.3%.14 The presence of controlled or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM) was identified using the procedure described by Guzman and colleagues.15 Quan’s algorithm was used to calculate Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on ICD-9-CM codes for inpatient and outpatient visits within a 6-month lookback period prior to treatment initiation.16

A major bleeding event was defined as a hospitalization with an ICD-9-CM code suggestive of major bleeding as the primary reason, as defined by Lane and colleagues in their study of major bleeding related to warfarin in a cohort of patients treated within the VHA.17 Incidence rates of major bleeding events were identified during the first 6 months of treatment. Incidence of Afib—defined as an inpatient or outpatient encounter with the 427.31 ICD-9-CM code—also was examined within the first 6 months after starting treatment. The period of 6 months was chosen because bendamustine must be discontinued after 6 months.

Study Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine patient demographics, disease characteristics, and treatment history from initial CLL diagnosis through end of study observation period. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and accompanying proportions, while a mean and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous variables. For the means of continuous variables and of categorical data, 95% CIs were used. Proportions and accompanying 95% CIs characterized treatment patterns, including line of therapy, comorbidities, and bleeding events. Treatment duration was described using mean and accompanying 95% CI. Statistical tests were not conducted for comparisons among treatment groups. Patients were censored at the end of follow-up, defined as the earliest of the following scenarios: (1) end of study observation period (December 31, 2016); (2) development of a secondary cancer; or (3) last day of contact given absence of care within the VHA for ≥ 18 months (with care defined as oncology and/or oncology/hematology visit with an associated note). Analysis was performed using R 3.4.0.

Results

Between 2010 and 2014, 2,796 patients were diagnosed and received care for CLL within the VHA. Overall, all 172 patients who were treated with ibrutinib during our inclusion period were selected. These patients were treated between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016, following ibrutinib’s approval in early 2014. An additional 291 patients were selected who received BR (Table). Reflecting the predominantly male population of the VHA, 282 (97%) BR patients and 167 (97%) ibrutinib patients were male. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years for BR patients and 69 years for ibrutinib patients. About 76% of patients who received ibrutinib and 82% of patients who received BR were non-Hispanic white; 17% and 14% were African American, respectively.

Less than 10% of patients receiving either ibrutinib or BR had liver disease per criteria used by Kramer and colleagues, or end-stage liver disease using criteria developed by Goldberg and colleagues.12,13 About 5% of patients had a history of previous bleeding in the 6-month period prior to initiating either therapy. Mean CCI (excluding malignancy) score was 1.5 (range, 0-11) for the ibrutinib group, and 2.1 (range, 0-9) for the BR group. About 16% of the ibrutinib group had controlled DM and fewer than 10% had uncontrolled DM, while 4% of patients in the BR group met the criteria for controlled DM and another 4% met the criteria for uncontrolled DM.

There was very low utilization of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication prior to initiation of ibrutinib (2.9% and 2.3%, respectively) or BR (< 1% each). In the first 6 months after treatment initiation, about 8% of patients in both ibrutinib and BR cohorts received anticoagulant medication while antiplatelet utilization was < 5% in either group.

In the BR group, 8 patients (2.7%) experienced a major bleeding event, while 14 patients (8.1%) in the ibrutinib group experienced a bleeding event (P = .008). While these numbers were too low to perform a formal statistical analysis of the association between clinical covariates and bleeding in either group, there did not seem to be an association between bleeding and liver disease or DM. Of patients who experienced a bleeding event, about 1 in 4 patients had had a prior bleeding event in both the ibrutinib and the BR groups. Interestingly, while none of the patients who experienced a bleeding event while receiving BR were taking concomitant anticoagulant medication, 3 of the 14 patients who experienced a bleeding event in the ibrutinib group showed evidence of anticoagulant utilization. Finally, the incidence of Afib (defined as patients with no evidence of Afib in the 6 months prior to treatment but with evidence of Afib in the 6 months following treatment initiation) was 4% in the BR group, and about 8% in the ibrutinib group (P = .003).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to examine the real-world incidence of bleeding and Afib in veterans who received ibrutinib for CLL in the first year of its availability. The study found minimal use of anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet agents prior to receiving first-line ibrutinib or BR, and very low use of these agents in the first 6 months following the initiation of first-line treatment. This finding suggests a high awareness among VA providers of potential adverse effects (AEs) of ibrutinib and chemotherapy, and a careful selection of patients that lack risk factors for AEs.

In patients treated with first-line ibrutinib when compared with patients treated with first-line BR, moderate increases in bleeding (2.7% vs 8.1%, P = .008) and Afib (10.5% vs 3%, P = .003) also were observed. These results are concordant with previous findings examining the use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL.18-20

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as some limitations must be considered. The study was conducted in the early days of ibrutinib adoption. Since then, more patients have been treated with ibrutinib and for longer durations. As clinicians gain more familiarity and with ibrutinib, and as additional novel therapeutics emerge, it is possible that the initial awareness about risks for possible AEs may diminish; patients with high comorbidity burdens and concomitant medications would be especially vulnerable in cases of reduced physician vigilance.

Another limitation of this study stems from the potential for dual system use among patients treated in the VHA. Concurrent or alternating use of multiple health care systems (use of VHA and private-sector facilities) may present gaps in the reconstruction of patient histories, resulting in missing data as patients transition between commercial, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and VHA care. As a result, the results presented here do not reflect instances where a patient experienced a bleeding event treated outside the VA.

Problems with missing data also may occur due to incomplete extraction from the electronic health record; these issues were addressed by leveraging an understanding of the multiple data marts within the CDW environment to harmonize missing and/or erroneous information through use of other data marts when possible. Lastly, this research represents a population-level study of the VHA, thus all findings are directly relevant to the VHA. The generalizability of the findings outside the VHA would depend on the characteristics of the external population.

Conclusion

Real-world evidence from a nationwide cohort of veteran patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib suggest that, while there is an association of increased bleeding-related events and Afib, the risk is comparable to those reported in previous studies.18-20 These findings suggest that patients in real-world clinical care settings with higher levels of comorbidities may be at a slight increased risk for bleeding events and Afib.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia diagnosed in developed countries, with an estimated 21,040 new diagnoses of CLL expected in the US in 2020. 1-3 CLL is an indolent cancer characterized by the accumulation of B-lymphocytes in the blood, marrow, and lymphoid tissues. 4 It has a heterogeneous clinical course; the majority of patients are observed or receive delayed treatment following diagnosis, while a minority of patients require immediate treatment. After first-line treatment, some patients experience prolonged remissions while others require retreatment within 1 or 2 years. Fortunately, advances in cancer biology and therapeutics in the last decade have increased the number of treatment options available for patients with CLL.

Until recently, most CLL treatments relied on a chemotherapy or a chemoimmunotherapy backbone; however, the last few years have seen novel therapies introduced, such as small molecule inhibitors to target molecular pathways that promote the normal development, expansion, and survival of B-cells.5 One such therapy is ibrutinib, a targeted Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2014 for patients with CLL who received at least 1 prior therapy. The FDA later expanded this approval to include use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL with relapsed or refractory disease, with or without chromosome 17p deletion. In 2016, based on data from the RESONATE-17 study, the FDA approved ibrutinib for first-line therapy in patients with CLL.6

Ibrutinib’s efficacy, ease of administration and dosing (all doses are oral and fixed, rather than based on weight or body surface area), and relatively favorable safety profile have resulted in a rapid growth in its adoption.7 Since its adverse event (AE) profile is generally more tolerable than that of a typical chemoimmunotherapy, its use in older patients with CLL and patients with significant comorbidities is particularly appealing.8

However, the results of some clinical trials suggest an association between treatment with ibrutinib and an increased risk of bleeding-related events of any grade (44%) and major bleeding events (4%).7,8 The incidence of major bleeding events was reported to be higher (9%) in one clinical trial and at 5-year follow-up, although this trial did not exclude patients receiving concomitant oral anticoagulation with warfarin.6,9

Heterogeneity in clinical trials’ definitions of major bleeding confounded the ability to calculate bleeding risk in patients treated with ibrutinib in a systematic review and meta-analysis that called for more data.10 Additionally, patients with factors that might increase the risk of major bleeding with ibrutinib treatment were likely underrepresented in clinical trials, given the carefully selected nature of clinical trial subjects. These factors include renal or hepatic disease, gastrointestinal disease, and use of a number of concomitant medications such as antiplatelets or anticoagulant medications. Accounting for use of the latter is particularly important because patients who develop atrial fibrillation (Afib), one of the recognized AEs of treatment with ibrutinib, often are treated with anticoagulant medications in order to decrease the risk of stroke or other thromboembolic complications.

A single-site observational study of patients treated with ibrutinib reported a high utilization rate of antiplatelet medications (70%), anticoagulant medications (17%), or both (13%) with a concomitant major bleeding rate of 18% of patients.11 Prevalence of bleeding events seemed to be highly affected by the presence of concomitant medications: 78% of patients treated with ibrutinib while concurrently receiving both antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications developed a major bleeding event, while none of the patients who were not receiving antiplatelets, anticoagulants, or medications that interact with cytochrome P450 (an enzyme that metabolized chemotherapeutic agents used to treat cancer) experienced a major bleeding event.11

The prevalence of major bleeding events, comorbidities, and utilization of medications that could increase the risk of major bleeding in patients with CLL on ibrutinib in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is not known. The VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the US. To address these knowledge gaps, a retrospective observational study was conducted using data on demographics, comorbidities that could affect bleeding, use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications, and bleeding events in patients with CLL who were treated in the first year of ibrutinib availability from the VHA.

The first year of ibrutinib availability was chosen for this study since we anticipated that many health care providers would be unfamiliar with ibrutinib during that time given its novelty, and therefore more likely to codispense ibrutinib with medications that could increase the risk of a bleeding event. Since Afib is both an AE associated with ibrutinib treatment and a condition that often is treated with anticoagulants, the prevalence of Afib in this population was also included. For context, the incidence of bleeding and Afib and use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications during treatment in a cohort of patients with CLL treated with bendamustine + rituximab (BR) also was reported.

Methods

The VHA maintains the centralized US Department of Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry System (VACRS), with electronic medical record data and other sources captured in its Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The VHA CDW is a national repository comprising data from several VHA clinical and administrative systems. The CDW includes patient identifiers; demographics; vital status; lab information; administrative information (such as diagnostic International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-9] codes); medication dispensation tables (such as outpatient fill); IV package information; and notes from radiology, pathology, outpatient and inpatient admission, discharge, and daily progress.

Registrars abstract all cancer cases within the VHA system (or diagnosed outside the VHA, if patients subsequently receive treatment in the VHA). It is estimated that VACRS captures 3% of cancer cases in the US.12 Like most registries, VACRS captures data such as diagnosis, age, gender, race, and vital status.

The study received approval from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and used individual patient-level historical administrative, cancer registry, and electronic health care record data. Patients diagnosed and treated for CLL at the VHA from 2010 to 2014 were identified through the VACRS and CDW; patients with a prior malignancy were excluded. Patients who received ibrutinib or BR based on pharmacy dispensation information were selected. Patients were followed until December 31, 2016 or death; patients with documentation of another cancer or lack of utilization of the VHA hematology or oncology services (defined as absence of any hematology and/or oncology clinic visits for ≥ 18 months) were omitted from the final analysis (Figure).

Previous and concomitant utilization of antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel) or anticoagulant (dalteparin, enoxaparin, fondaparinux, heparin, rivaroxaban, and warfarin) medications was extracted 6 months before and after the first dispensation of ibrutinib or BR using pharmacy dispensation records.

Study Definitions

Prevalence of comorbidities that could increase bleeding risk was determined using administrative ICD-9-CM codes. Liver disease was identified by presence of cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus, or alcoholic liver disease using administrative codes validated by Kramer and colleagues, who reported positive and negative predictive values of 90% and 87% for cirrhosis, 93% and 92% for hepatitis C virus, and 71% and 98% for alcoholic liver disease.13 Similarly, end-stage liver disease was identified using a validated coding algorithm developed by Goldberg and colleagues, with a positive predictive value of 89.3%.14 The presence of controlled or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM) was identified using the procedure described by Guzman and colleagues.15 Quan’s algorithm was used to calculate Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on ICD-9-CM codes for inpatient and outpatient visits within a 6-month lookback period prior to treatment initiation.16

A major bleeding event was defined as a hospitalization with an ICD-9-CM code suggestive of major bleeding as the primary reason, as defined by Lane and colleagues in their study of major bleeding related to warfarin in a cohort of patients treated within the VHA.17 Incidence rates of major bleeding events were identified during the first 6 months of treatment. Incidence of Afib—defined as an inpatient or outpatient encounter with the 427.31 ICD-9-CM code—also was examined within the first 6 months after starting treatment. The period of 6 months was chosen because bendamustine must be discontinued after 6 months.

Study Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine patient demographics, disease characteristics, and treatment history from initial CLL diagnosis through end of study observation period. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and accompanying proportions, while a mean and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous variables. For the means of continuous variables and of categorical data, 95% CIs were used. Proportions and accompanying 95% CIs characterized treatment patterns, including line of therapy, comorbidities, and bleeding events. Treatment duration was described using mean and accompanying 95% CI. Statistical tests were not conducted for comparisons among treatment groups. Patients were censored at the end of follow-up, defined as the earliest of the following scenarios: (1) end of study observation period (December 31, 2016); (2) development of a secondary cancer; or (3) last day of contact given absence of care within the VHA for ≥ 18 months (with care defined as oncology and/or oncology/hematology visit with an associated note). Analysis was performed using R 3.4.0.

Results

Between 2010 and 2014, 2,796 patients were diagnosed and received care for CLL within the VHA. Overall, all 172 patients who were treated with ibrutinib during our inclusion period were selected. These patients were treated between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016, following ibrutinib’s approval in early 2014. An additional 291 patients were selected who received BR (Table). Reflecting the predominantly male population of the VHA, 282 (97%) BR patients and 167 (97%) ibrutinib patients were male. The median age at diagnosis was 67 years for BR patients and 69 years for ibrutinib patients. About 76% of patients who received ibrutinib and 82% of patients who received BR were non-Hispanic white; 17% and 14% were African American, respectively.

Less than 10% of patients receiving either ibrutinib or BR had liver disease per criteria used by Kramer and colleagues, or end-stage liver disease using criteria developed by Goldberg and colleagues.12,13 About 5% of patients had a history of previous bleeding in the 6-month period prior to initiating either therapy. Mean CCI (excluding malignancy) score was 1.5 (range, 0-11) for the ibrutinib group, and 2.1 (range, 0-9) for the BR group. About 16% of the ibrutinib group had controlled DM and fewer than 10% had uncontrolled DM, while 4% of patients in the BR group met the criteria for controlled DM and another 4% met the criteria for uncontrolled DM.

There was very low utilization of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication prior to initiation of ibrutinib (2.9% and 2.3%, respectively) or BR (< 1% each). In the first 6 months after treatment initiation, about 8% of patients in both ibrutinib and BR cohorts received anticoagulant medication while antiplatelet utilization was < 5% in either group.

In the BR group, 8 patients (2.7%) experienced a major bleeding event, while 14 patients (8.1%) in the ibrutinib group experienced a bleeding event (P = .008). While these numbers were too low to perform a formal statistical analysis of the association between clinical covariates and bleeding in either group, there did not seem to be an association between bleeding and liver disease or DM. Of patients who experienced a bleeding event, about 1 in 4 patients had had a prior bleeding event in both the ibrutinib and the BR groups. Interestingly, while none of the patients who experienced a bleeding event while receiving BR were taking concomitant anticoagulant medication, 3 of the 14 patients who experienced a bleeding event in the ibrutinib group showed evidence of anticoagulant utilization. Finally, the incidence of Afib (defined as patients with no evidence of Afib in the 6 months prior to treatment but with evidence of Afib in the 6 months following treatment initiation) was 4% in the BR group, and about 8% in the ibrutinib group (P = .003).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to examine the real-world incidence of bleeding and Afib in veterans who received ibrutinib for CLL in the first year of its availability. The study found minimal use of anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet agents prior to receiving first-line ibrutinib or BR, and very low use of these agents in the first 6 months following the initiation of first-line treatment. This finding suggests a high awareness among VA providers of potential adverse effects (AEs) of ibrutinib and chemotherapy, and a careful selection of patients that lack risk factors for AEs.

In patients treated with first-line ibrutinib when compared with patients treated with first-line BR, moderate increases in bleeding (2.7% vs 8.1%, P = .008) and Afib (10.5% vs 3%, P = .003) also were observed. These results are concordant with previous findings examining the use of ibrutinib in patients with CLL.18-20

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as some limitations must be considered. The study was conducted in the early days of ibrutinib adoption. Since then, more patients have been treated with ibrutinib and for longer durations. As clinicians gain more familiarity and with ibrutinib, and as additional novel therapeutics emerge, it is possible that the initial awareness about risks for possible AEs may diminish; patients with high comorbidity burdens and concomitant medications would be especially vulnerable in cases of reduced physician vigilance.

Another limitation of this study stems from the potential for dual system use among patients treated in the VHA. Concurrent or alternating use of multiple health care systems (use of VHA and private-sector facilities) may present gaps in the reconstruction of patient histories, resulting in missing data as patients transition between commercial, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and VHA care. As a result, the results presented here do not reflect instances where a patient experienced a bleeding event treated outside the VA.

Problems with missing data also may occur due to incomplete extraction from the electronic health record; these issues were addressed by leveraging an understanding of the multiple data marts within the CDW environment to harmonize missing and/or erroneous information through use of other data marts when possible. Lastly, this research represents a population-level study of the VHA, thus all findings are directly relevant to the VHA. The generalizability of the findings outside the VHA would depend on the characteristics of the external population.

Conclusion

Real-world evidence from a nationwide cohort of veteran patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib suggest that, while there is an association of increased bleeding-related events and Afib, the risk is comparable to those reported in previous studies.18-20 These findings suggest that patients in real-world clinical care settings with higher levels of comorbidities may be at a slight increased risk for bleeding events and Afib.

1. Scarfò L, Ferreri AJ, Ghia P. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:169-182.

2. Devereux S, Cuthill K. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;45(5):292-296.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2020.

4. Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:16096.

5. Owen C, Assouline S, Kuruvilla J, Uchida C, Bellingham C, Sehn L. Novel therapies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a Canadian perspective. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(11):627-634.e5.

6. O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1409–1418.

7. Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425-2437.

8. Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42.

9. O’Brien S, Furman R, Coutre S, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131(17):1910-1919.

10. Caron F, Leong DP, Hillis C, Fraser G, Siegal D. Current understanding of bleeding with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2017;1(12):772-778.

11. Kunk PR, Mock J, Devitt ME, Palkimas S, et al. Major bleeding with ibrutinib: more than expected. Blood. 2016;128(22):3229.

12. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

13. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274-282.

14. Goldberg D, Lewis JD, Halpern SD, Weiner M, Lo Re V 3rd. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(7):765-769.

15. Guzman JZ, Iatridis JC, Skovrlj B, et al. Outcomes and complications of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing degenerative lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(19):1596-1604.

16. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

17. Lane MA, Zeringue A, McDonald JR. Serious bleeding events due to warfarin and antibiotic co-prescription in a cohort of veterans. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):657–663.e2.

18. Leong DP, Caron F, Hillis C, et al. The risk of atrial fibrillation with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2016;128(1):138-140.

19. Lipsky AH, Farooqui MZ, Tian X, et al. Incidence and risk factors of bleeding-related adverse events in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Haematologica. 2015;100(12):1571-1578.

20. Brown JR, Moslehi J, O’Brien S, et al. Characterization of atrial fibrillation adverse events reported in ibrutinib randomized controlled registration trials. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1796-1805.

1. Scarfò L, Ferreri AJ, Ghia P. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:169-182.

2. Devereux S, Cuthill K. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;45(5):292-296.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2020.

4. Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:16096.

5. Owen C, Assouline S, Kuruvilla J, Uchida C, Bellingham C, Sehn L. Novel therapies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a Canadian perspective. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(11):627-634.e5.

6. O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1409–1418.

7. Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425-2437.

8. Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42.

9. O’Brien S, Furman R, Coutre S, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131(17):1910-1919.

10. Caron F, Leong DP, Hillis C, Fraser G, Siegal D. Current understanding of bleeding with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2017;1(12):772-778.

11. Kunk PR, Mock J, Devitt ME, Palkimas S, et al. Major bleeding with ibrutinib: more than expected. Blood. 2016;128(22):3229.

12. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

13. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274-282.

14. Goldberg D, Lewis JD, Halpern SD, Weiner M, Lo Re V 3rd. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(7):765-769.

15. Guzman JZ, Iatridis JC, Skovrlj B, et al. Outcomes and complications of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing degenerative lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(19):1596-1604.

16. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

17. Lane MA, Zeringue A, McDonald JR. Serious bleeding events due to warfarin and antibiotic co-prescription in a cohort of veterans. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):657–663.e2.

18. Leong DP, Caron F, Hillis C, et al. The risk of atrial fibrillation with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2016;128(1):138-140.

19. Lipsky AH, Farooqui MZ, Tian X, et al. Incidence and risk factors of bleeding-related adverse events in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Haematologica. 2015;100(12):1571-1578.

20. Brown JR, Moslehi J, O’Brien S, et al. Characterization of atrial fibrillation adverse events reported in ibrutinib randomized controlled registration trials. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1796-1805.

Hyperprogression on immunotherapy: When outcomes are much worse

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”