User login

Coronavirus on fabric: What you should know

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

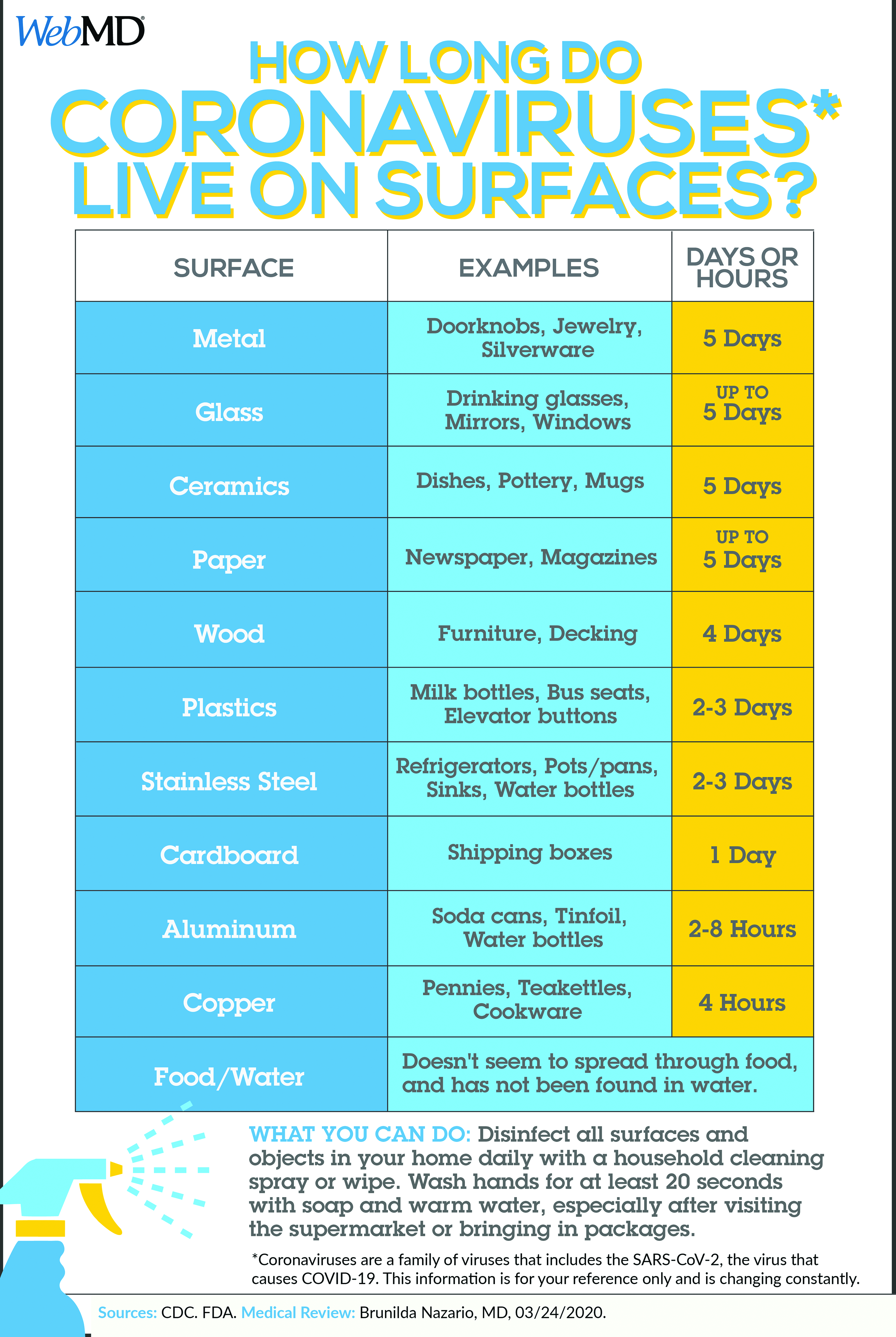

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Neurologic symptoms and COVID-19: What’s known, what isn’t

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 less severe in children, yet questions for pediatricians remain

COVID-19 is less severe in children, compared with adults, early data suggest. “Yet many questions remain, especially regarding the effects on children with special health care needs,” according to a viewpoint recently published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The COVID-19 pandemic also raises questions about clinic visits for healthy children in communities with widespread transmission and about the unintended effects of school closures and other measures aimed at slowing the spread of the disease, wrote Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, both of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In communities with widespread outbreaks, telephone triage and expanded use of telehealth may be needed to limit nonurgent clinic visits, they suggested.

“Community mitigation interventions, such as school closures, cancellation of mass gatherings, and closure of public places are appropriate” in places with widespread transmission, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “If these measures are required, pediatricians need to advocate to alleviate unintended consequences or inadvertent expansion of health disparities on children, such as by finding ways to maintain nutrition for those who depend on school lunches and provide online mental health services for stress management for families whose routines might be severely interrupted for an extended period of time.”

Continued preventive care for infants and vaccinations for younger children may be warranted, they wrote.

Clinical course

Overall, children have experienced lower-than-expected rates of COVID-19 disease, and deaths in this population appear to be rare, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 in adults include fever, cough, myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, and diarrhea, and children have similar manifestations. In adults, older age and underlying illness increase the risk of severe disease. There has not been convincing evidence of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19, and whether breastfeeding can transmit the virus is unknown, they noted.

An analysis of more than 72,000 cases from China found that 1.2% were in patients aged 10-19 years, and 0.9% were in patients younger than 10 years. One death occurred in the adolescent age range. A separate analysis of 2,143 confirmed and suspected pediatric cases in China indicated that infants were at higher risk of severe disease (11%), compared with older children – 4% for those aged 11-15 years, and 3% in those 16 years and older.

There is less data available about the clinical course of COVID-19 in children in the United States, the authors noted. But among more than 4,000 patients with COVID-19 in the United States through March 16, no ICU admissions or deaths were reported for patients aged younger than 19 years (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 26;69[12]:343-6).

Still, researchers have suggested that children with underlying illness may be at greater risk of COVID-19. In a study of 20 children with COVID-19 in China, 7 of the patients had a history of congenital or acquired disease, potentially indicating that they were more susceptible to the virus (Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718). Chest CT consolidations with surrounding halo sign was evident in half of the patients, and procalcitonin elevation was seen in 80% of the children; these were signs common in children, but not in adults with COVID-19.

“About 10% of children in the U.S. have asthma; many children live with other pulmonary, cardiac, neuromuscular, or genetic diseases that affect their ability to handle respiratory disease, and other children are immunosuppressed because of illness or its treatment,” Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “It is possible that these children will experience COVID-19 differently than counterparts of the same ages who are healthy.”

The authors reported that they had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rasmussen SA, Thompson LA. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1224.

COVID-19 is less severe in children, compared with adults, early data suggest. “Yet many questions remain, especially regarding the effects on children with special health care needs,” according to a viewpoint recently published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The COVID-19 pandemic also raises questions about clinic visits for healthy children in communities with widespread transmission and about the unintended effects of school closures and other measures aimed at slowing the spread of the disease, wrote Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, both of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In communities with widespread outbreaks, telephone triage and expanded use of telehealth may be needed to limit nonurgent clinic visits, they suggested.

“Community mitigation interventions, such as school closures, cancellation of mass gatherings, and closure of public places are appropriate” in places with widespread transmission, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “If these measures are required, pediatricians need to advocate to alleviate unintended consequences or inadvertent expansion of health disparities on children, such as by finding ways to maintain nutrition for those who depend on school lunches and provide online mental health services for stress management for families whose routines might be severely interrupted for an extended period of time.”

Continued preventive care for infants and vaccinations for younger children may be warranted, they wrote.

Clinical course

Overall, children have experienced lower-than-expected rates of COVID-19 disease, and deaths in this population appear to be rare, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 in adults include fever, cough, myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, and diarrhea, and children have similar manifestations. In adults, older age and underlying illness increase the risk of severe disease. There has not been convincing evidence of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19, and whether breastfeeding can transmit the virus is unknown, they noted.

An analysis of more than 72,000 cases from China found that 1.2% were in patients aged 10-19 years, and 0.9% were in patients younger than 10 years. One death occurred in the adolescent age range. A separate analysis of 2,143 confirmed and suspected pediatric cases in China indicated that infants were at higher risk of severe disease (11%), compared with older children – 4% for those aged 11-15 years, and 3% in those 16 years and older.

There is less data available about the clinical course of COVID-19 in children in the United States, the authors noted. But among more than 4,000 patients with COVID-19 in the United States through March 16, no ICU admissions or deaths were reported for patients aged younger than 19 years (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 26;69[12]:343-6).

Still, researchers have suggested that children with underlying illness may be at greater risk of COVID-19. In a study of 20 children with COVID-19 in China, 7 of the patients had a history of congenital or acquired disease, potentially indicating that they were more susceptible to the virus (Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718). Chest CT consolidations with surrounding halo sign was evident in half of the patients, and procalcitonin elevation was seen in 80% of the children; these were signs common in children, but not in adults with COVID-19.

“About 10% of children in the U.S. have asthma; many children live with other pulmonary, cardiac, neuromuscular, or genetic diseases that affect their ability to handle respiratory disease, and other children are immunosuppressed because of illness or its treatment,” Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “It is possible that these children will experience COVID-19 differently than counterparts of the same ages who are healthy.”

The authors reported that they had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rasmussen SA, Thompson LA. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1224.

COVID-19 is less severe in children, compared with adults, early data suggest. “Yet many questions remain, especially regarding the effects on children with special health care needs,” according to a viewpoint recently published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The COVID-19 pandemic also raises questions about clinic visits for healthy children in communities with widespread transmission and about the unintended effects of school closures and other measures aimed at slowing the spread of the disease, wrote Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, both of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In communities with widespread outbreaks, telephone triage and expanded use of telehealth may be needed to limit nonurgent clinic visits, they suggested.

“Community mitigation interventions, such as school closures, cancellation of mass gatherings, and closure of public places are appropriate” in places with widespread transmission, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “If these measures are required, pediatricians need to advocate to alleviate unintended consequences or inadvertent expansion of health disparities on children, such as by finding ways to maintain nutrition for those who depend on school lunches and provide online mental health services for stress management for families whose routines might be severely interrupted for an extended period of time.”

Continued preventive care for infants and vaccinations for younger children may be warranted, they wrote.

Clinical course

Overall, children have experienced lower-than-expected rates of COVID-19 disease, and deaths in this population appear to be rare, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 in adults include fever, cough, myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, and diarrhea, and children have similar manifestations. In adults, older age and underlying illness increase the risk of severe disease. There has not been convincing evidence of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19, and whether breastfeeding can transmit the virus is unknown, they noted.

An analysis of more than 72,000 cases from China found that 1.2% were in patients aged 10-19 years, and 0.9% were in patients younger than 10 years. One death occurred in the adolescent age range. A separate analysis of 2,143 confirmed and suspected pediatric cases in China indicated that infants were at higher risk of severe disease (11%), compared with older children – 4% for those aged 11-15 years, and 3% in those 16 years and older.

There is less data available about the clinical course of COVID-19 in children in the United States, the authors noted. But among more than 4,000 patients with COVID-19 in the United States through March 16, no ICU admissions or deaths were reported for patients aged younger than 19 years (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 26;69[12]:343-6).

Still, researchers have suggested that children with underlying illness may be at greater risk of COVID-19. In a study of 20 children with COVID-19 in China, 7 of the patients had a history of congenital or acquired disease, potentially indicating that they were more susceptible to the virus (Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718). Chest CT consolidations with surrounding halo sign was evident in half of the patients, and procalcitonin elevation was seen in 80% of the children; these were signs common in children, but not in adults with COVID-19.

“About 10% of children in the U.S. have asthma; many children live with other pulmonary, cardiac, neuromuscular, or genetic diseases that affect their ability to handle respiratory disease, and other children are immunosuppressed because of illness or its treatment,” Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “It is possible that these children will experience COVID-19 differently than counterparts of the same ages who are healthy.”

The authors reported that they had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rasmussen SA, Thompson LA. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1224.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Flu activity down from its third peak of the season, COVID-19 still a factor

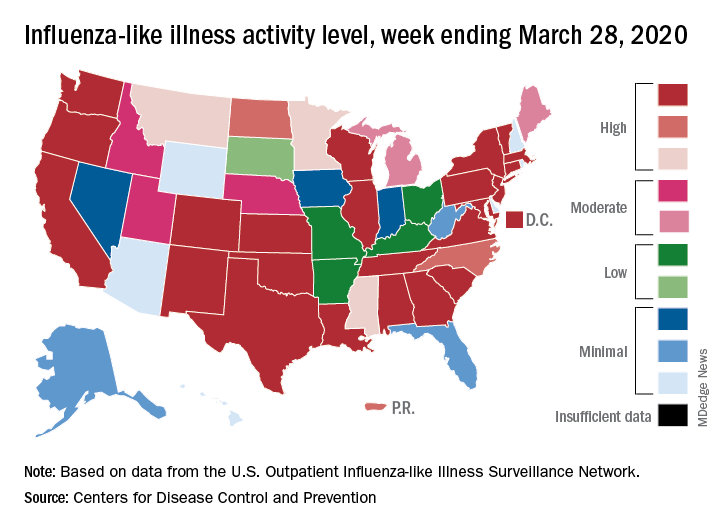

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

FDA grants emergency authorization for first rapid antibody test for COVID-19

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

Virtual Dermatology: A COVID-19 Update

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit

Follow these guidelines for practicing teledermatology: (1) ensure that the image or video is clear and that there is proper lighting, a monochromatic background, and a clear view of the anatomy necessary to evaluate; (2) dress in appropriate attire as if you were in clinic, such as scrubs, a white coat, or other professional attire; (3) begin the telehealth encounter by obtaining informed consent,13 according to state14 or Medicare guidelines; (4) document the location of the patient and provider; (5) for live virtual visits, document similarly to an in-person visit5; (6) for all other virtual care, document minutes spent on each task; and (7) select only 1 billing code per visit.

In some states, regulations for commercial and/or Medicaid plans require that other modifiers be added to billing codes, which vary plan-by-plan:

• Modifier GQ: For asynchronous care (store and forward).

• Modifier GT: For synchronous live telehealth visits.

• Modifier -95: In states where there are equal parity laws or if you are billing a commercial insurance payer (may vary by plan).

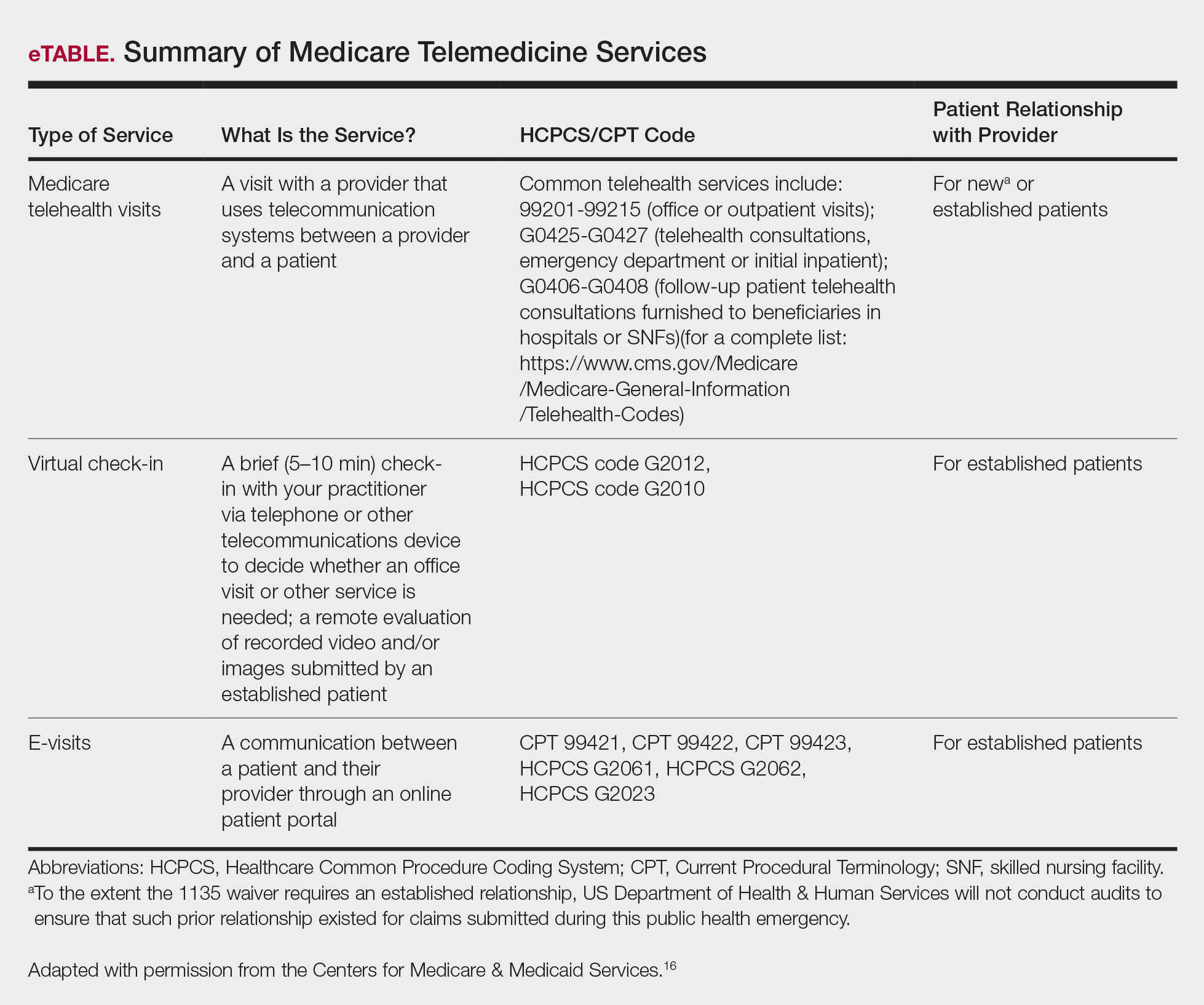

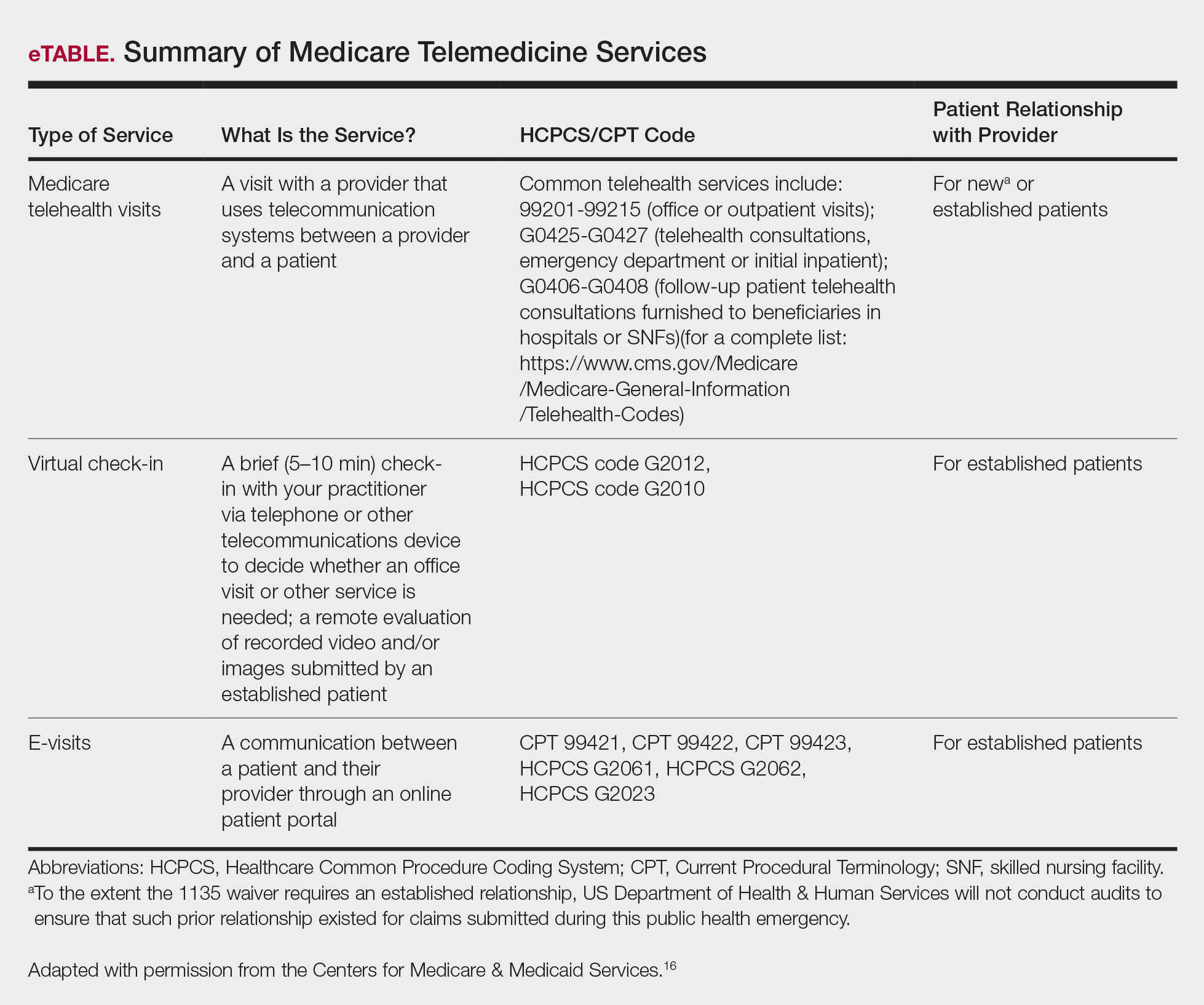

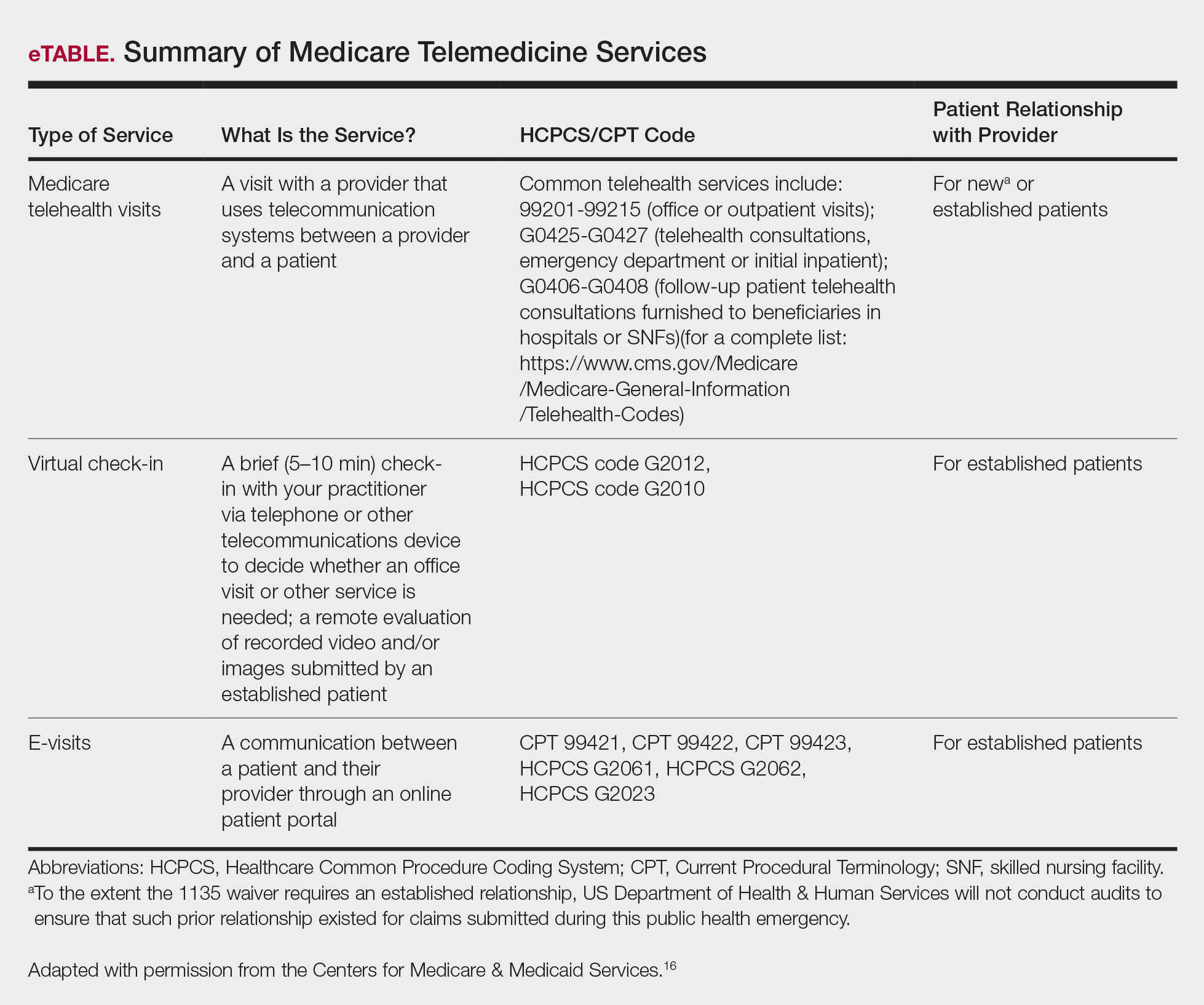

Medicare does not require any additional modifiers.15 If the plan reimburses telemedicine equally to a face-to-face visit, use regular office visit codes. The eTable16 lists billing codes and Medicare reimbursement rates.

Secure Software

Several electronic medical record systems already include secure patient communication. Other HIPAA-compliant communication options with a variety of features are available to clinicians:

• Klara allows for HIPAA-secure texting, group messaging, photograph uploads, and telephone calls.

• Doximity offers free calling and faxes.

• G Suite for health care offers HIPAA-compliant texting, emailing, and video calls through Google Voice and Google Hangouts Meet.

• Secure video chat is available on Zoom for Healthcare, VSee, Doxy.me, and other platforms.

• Multiservice platforms such as DermEngine include billing, payments, teledermatology, and teledermoscopy and allow for interprofessional consultation.

The Bottom Line

Telehealth readiness is playing a key role in containing the spread of COVID-19. In-person dermatology visits are now being limited to urgent conditions only, as per institutional guidelines.4

Acknowledgment

We thank Garfunkel Wild, P.C. (Great Neck, New York), for their expertise and assistance.

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, 2020. HR 748, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr748. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020. HR 6074, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr6074/text. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Azar AM II. Waiver or Modification of Requirements Under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions

/section1135/Pages/covid19-13March20.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2020. - American Academy of Dermatology Association. Can dermatologists use telemedicine to mitigate COVID-19 outbreaks? https://www.aad.org/member/practice/telederm/toolkit. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_ama

&utm_term=3207044834&utm_campaign=Public+Health. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020. - Federation of State Medical Boards. States waiving licensure requirements in response to COVID-19. http://www.fsmb.org/sitassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requimentscovid-19.pdf. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- American Telemedicine Association. 2019 State of the States: coverage & reimbursement. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/5096139/Files/Thought Leadership_ATA/2019 State of the States summary_final.pdf. Published July 18, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- COVID-19 related state actions. Center for Connected Health Policy website. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Governor Murphy announces departmental actions to expand access to telehealth and tele-mental health services in response to COVID-19 [news release]. Trenton, NJ: State of New Jersey; March 22, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200322b.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Caride M. Use of telemedicine and telehealth to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. State of New Jersey website. https://www.state.nj.us/dobi/bulletins/blt20_07.pdf. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Telemedicine forms. American Telemedicine Association Web site. http://hub.americantelemed.org/thesource/resources/telemedicine-forms. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- State telemedicine laws, simplified. eVisit Web site. https://evisit.com/state-telemedicine-policy/. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Response to the Public Health Emergency on the Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 20, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/se20011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit

Follow these guidelines for practicing teledermatology: (1) ensure that the image or video is clear and that there is proper lighting, a monochromatic background, and a clear view of the anatomy necessary to evaluate; (2) dress in appropriate attire as if you were in clinic, such as scrubs, a white coat, or other professional attire; (3) begin the telehealth encounter by obtaining informed consent,13 according to state14 or Medicare guidelines; (4) document the location of the patient and provider; (5) for live virtual visits, document similarly to an in-person visit5; (6) for all other virtual care, document minutes spent on each task; and (7) select only 1 billing code per visit.

In some states, regulations for commercial and/or Medicaid plans require that other modifiers be added to billing codes, which vary plan-by-plan:

• Modifier GQ: For asynchronous care (store and forward).

• Modifier GT: For synchronous live telehealth visits.

• Modifier -95: In states where there are equal parity laws or if you are billing a commercial insurance payer (may vary by plan).

Medicare does not require any additional modifiers.15 If the plan reimburses telemedicine equally to a face-to-face visit, use regular office visit codes. The eTable16 lists billing codes and Medicare reimbursement rates.

Secure Software

Several electronic medical record systems already include secure patient communication. Other HIPAA-compliant communication options with a variety of features are available to clinicians:

• Klara allows for HIPAA-secure texting, group messaging, photograph uploads, and telephone calls.

• Doximity offers free calling and faxes.

• G Suite for health care offers HIPAA-compliant texting, emailing, and video calls through Google Voice and Google Hangouts Meet.

• Secure video chat is available on Zoom for Healthcare, VSee, Doxy.me, and other platforms.

• Multiservice platforms such as DermEngine include billing, payments, teledermatology, and teledermoscopy and allow for interprofessional consultation.

The Bottom Line

Telehealth readiness is playing a key role in containing the spread of COVID-19. In-person dermatology visits are now being limited to urgent conditions only, as per institutional guidelines.4

Acknowledgment

We thank Garfunkel Wild, P.C. (Great Neck, New York), for their expertise and assistance.

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit