User login

Dermatology and Vaccines: We Must Do Better

Vaccines work. They are powerful tools that have saved millions of lives worldwide; however, a robust antivaccine movement has taken hold in the United States and worldwide despite overwhelming data in support of vaccination. In fact, vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines—was listed by the World Health Organization as one of the top 10 global health threats in 2019.1

Several vaccines have a role in dermatology, including the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9 [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp]), the herpes zoster vaccines (Zostavax [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp] and Shingrix [GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals]), and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, among others. These vaccinations are necessary for children and many adults alike, and they play a critical role in protecting both healthy and immunosuppressed patients.

Vaccine hesitancy is a growing threat to individual and public health that requires a response from all physicians. In our experience, dermatologists have been somewhat passive in advocating for vaccinations, possibly due to knowledge barriers or time constraints; however, this stance must change. Dermatologists must join the front lines in advocating for vaccinations, which are a proven and effective modality in promoting public health.

Dermatologists can employ the following practical tips to improve vaccination compliance among patients:

• Familiarize yourself with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention immunization schedules and vaccination information sheets (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/current-vis.html). Printed copies of informational handouts should be readily available to provide to patients in the office. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offers tip sheets to guide conversations with patients (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/index.html).

• Prior to starting an immunosuppressive medication, confirm the patient’s immunization status. You should know which vaccines are live (containing an attenuated pathogen) and which are inactivated. Live vaccines typically are not administered to immunosuppressed patients.

• Use electronic medical records to help provide reminders to prompt administration of any necessary vaccines.

• Know the facts, especially regarding purported vaccine controversies, and be able to cite data on vaccine safety and efficacy. For example, when having a conversation with a patient you could state that vaccination against HPV, which can cause genital warts and certain cancers, has decreased the number of HPV infections by more than 70% in young women and 80% in teenaged girls.2 Cervical precancers were reduced by 40% in women vaccinated against HPV. Twelve years of monitoring data validates the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine—it is safe and effective, with benefits that outweigh any potential risks.2

• Tailor counseling based on the patient’s age and focus on benefits that directly impact the patient. For example, consider showing young adults photographs of genital warts while educating them that the HPV vaccine can help prevent this kind of infection in the future.

• Emphasize that vaccines are a routine part of comprehensive patient care and support this point by providing data and specific reasons for recommending vaccines.3 Avoid phrases such as, “Do you want the vaccine?” or “You could consider receiving the vaccine today,” which can imply that the vaccine is not necessary.

• Offer vaccines in your office or provide clear printed informational sheets directing patients to nearby primary care clinics, infectious disease clinics, or pharmacies where vaccinations are offered.

• Consider using social media to promote the benefits of vaccination among patients.

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has brought the topic of vaccination into the limelight while highlighting that rampant misinformation can lead to distrust of health care workers. Dermatologists, along with all physicians, should be trusted advisors and advocates for public health. In addition to being knowledgeable, dermatologists must remain open-minded in having conversations with skeptical patients. Physicians must take the time and effort to promote vaccinations—the health of patients and the general public depends on it.

- Akbar R. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Published March 21, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- HPV vaccination is safe and effective. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccinesafety.html. Updated April 29, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- How to give a strong recommendation to adult patients who require vaccination. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/842874. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2020.

Vaccines work. They are powerful tools that have saved millions of lives worldwide; however, a robust antivaccine movement has taken hold in the United States and worldwide despite overwhelming data in support of vaccination. In fact, vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines—was listed by the World Health Organization as one of the top 10 global health threats in 2019.1

Several vaccines have a role in dermatology, including the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9 [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp]), the herpes zoster vaccines (Zostavax [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp] and Shingrix [GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals]), and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, among others. These vaccinations are necessary for children and many adults alike, and they play a critical role in protecting both healthy and immunosuppressed patients.

Vaccine hesitancy is a growing threat to individual and public health that requires a response from all physicians. In our experience, dermatologists have been somewhat passive in advocating for vaccinations, possibly due to knowledge barriers or time constraints; however, this stance must change. Dermatologists must join the front lines in advocating for vaccinations, which are a proven and effective modality in promoting public health.

Dermatologists can employ the following practical tips to improve vaccination compliance among patients:

• Familiarize yourself with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention immunization schedules and vaccination information sheets (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/current-vis.html). Printed copies of informational handouts should be readily available to provide to patients in the office. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offers tip sheets to guide conversations with patients (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/index.html).

• Prior to starting an immunosuppressive medication, confirm the patient’s immunization status. You should know which vaccines are live (containing an attenuated pathogen) and which are inactivated. Live vaccines typically are not administered to immunosuppressed patients.

• Use electronic medical records to help provide reminders to prompt administration of any necessary vaccines.

• Know the facts, especially regarding purported vaccine controversies, and be able to cite data on vaccine safety and efficacy. For example, when having a conversation with a patient you could state that vaccination against HPV, which can cause genital warts and certain cancers, has decreased the number of HPV infections by more than 70% in young women and 80% in teenaged girls.2 Cervical precancers were reduced by 40% in women vaccinated against HPV. Twelve years of monitoring data validates the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine—it is safe and effective, with benefits that outweigh any potential risks.2

• Tailor counseling based on the patient’s age and focus on benefits that directly impact the patient. For example, consider showing young adults photographs of genital warts while educating them that the HPV vaccine can help prevent this kind of infection in the future.

• Emphasize that vaccines are a routine part of comprehensive patient care and support this point by providing data and specific reasons for recommending vaccines.3 Avoid phrases such as, “Do you want the vaccine?” or “You could consider receiving the vaccine today,” which can imply that the vaccine is not necessary.

• Offer vaccines in your office or provide clear printed informational sheets directing patients to nearby primary care clinics, infectious disease clinics, or pharmacies where vaccinations are offered.

• Consider using social media to promote the benefits of vaccination among patients.

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has brought the topic of vaccination into the limelight while highlighting that rampant misinformation can lead to distrust of health care workers. Dermatologists, along with all physicians, should be trusted advisors and advocates for public health. In addition to being knowledgeable, dermatologists must remain open-minded in having conversations with skeptical patients. Physicians must take the time and effort to promote vaccinations—the health of patients and the general public depends on it.

Vaccines work. They are powerful tools that have saved millions of lives worldwide; however, a robust antivaccine movement has taken hold in the United States and worldwide despite overwhelming data in support of vaccination. In fact, vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines—was listed by the World Health Organization as one of the top 10 global health threats in 2019.1

Several vaccines have a role in dermatology, including the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9 [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp]), the herpes zoster vaccines (Zostavax [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp] and Shingrix [GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals]), and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, among others. These vaccinations are necessary for children and many adults alike, and they play a critical role in protecting both healthy and immunosuppressed patients.

Vaccine hesitancy is a growing threat to individual and public health that requires a response from all physicians. In our experience, dermatologists have been somewhat passive in advocating for vaccinations, possibly due to knowledge barriers or time constraints; however, this stance must change. Dermatologists must join the front lines in advocating for vaccinations, which are a proven and effective modality in promoting public health.

Dermatologists can employ the following practical tips to improve vaccination compliance among patients:

• Familiarize yourself with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention immunization schedules and vaccination information sheets (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/current-vis.html). Printed copies of informational handouts should be readily available to provide to patients in the office. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offers tip sheets to guide conversations with patients (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/index.html).

• Prior to starting an immunosuppressive medication, confirm the patient’s immunization status. You should know which vaccines are live (containing an attenuated pathogen) and which are inactivated. Live vaccines typically are not administered to immunosuppressed patients.

• Use electronic medical records to help provide reminders to prompt administration of any necessary vaccines.

• Know the facts, especially regarding purported vaccine controversies, and be able to cite data on vaccine safety and efficacy. For example, when having a conversation with a patient you could state that vaccination against HPV, which can cause genital warts and certain cancers, has decreased the number of HPV infections by more than 70% in young women and 80% in teenaged girls.2 Cervical precancers were reduced by 40% in women vaccinated against HPV. Twelve years of monitoring data validates the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine—it is safe and effective, with benefits that outweigh any potential risks.2

• Tailor counseling based on the patient’s age and focus on benefits that directly impact the patient. For example, consider showing young adults photographs of genital warts while educating them that the HPV vaccine can help prevent this kind of infection in the future.

• Emphasize that vaccines are a routine part of comprehensive patient care and support this point by providing data and specific reasons for recommending vaccines.3 Avoid phrases such as, “Do you want the vaccine?” or “You could consider receiving the vaccine today,” which can imply that the vaccine is not necessary.

• Offer vaccines in your office or provide clear printed informational sheets directing patients to nearby primary care clinics, infectious disease clinics, or pharmacies where vaccinations are offered.

• Consider using social media to promote the benefits of vaccination among patients.

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has brought the topic of vaccination into the limelight while highlighting that rampant misinformation can lead to distrust of health care workers. Dermatologists, along with all physicians, should be trusted advisors and advocates for public health. In addition to being knowledgeable, dermatologists must remain open-minded in having conversations with skeptical patients. Physicians must take the time and effort to promote vaccinations—the health of patients and the general public depends on it.

- Akbar R. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Published March 21, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- HPV vaccination is safe and effective. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccinesafety.html. Updated April 29, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- How to give a strong recommendation to adult patients who require vaccination. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/842874. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- Akbar R. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Published March 21, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- HPV vaccination is safe and effective. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccinesafety.html. Updated April 29, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- How to give a strong recommendation to adult patients who require vaccination. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/842874. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2020.

Infant’s COVID-19–related myocardial injury reversed

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

FROM JACC CASE REPORTS

Key clinical point: Children presenting with COVID-19 should be tested for heart failure.

Major finding: A 2-month-old infant with COVID-19 had acute but reversible myocardial injury.

Study details: Single case report.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharma, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Obesity, hypoxia predict severity in children with COVID-19

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

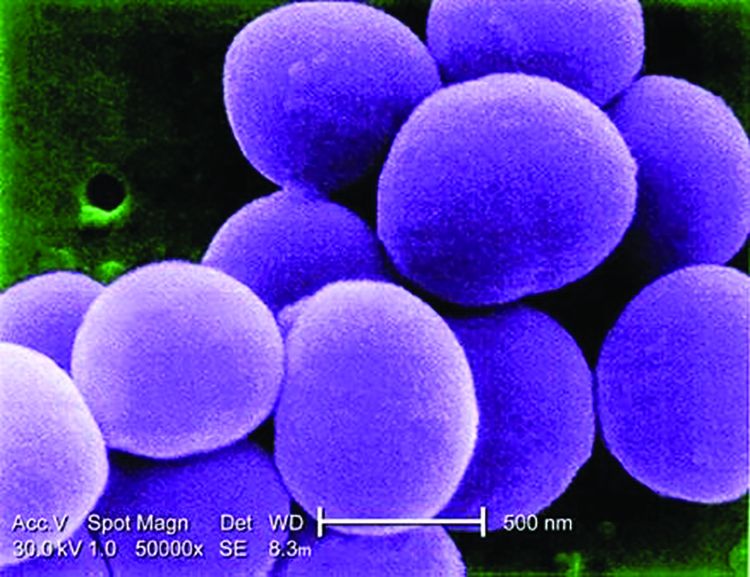

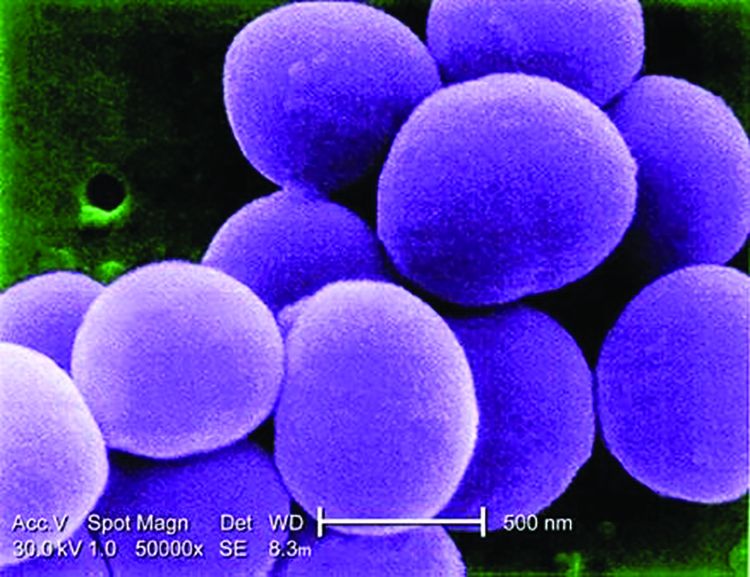

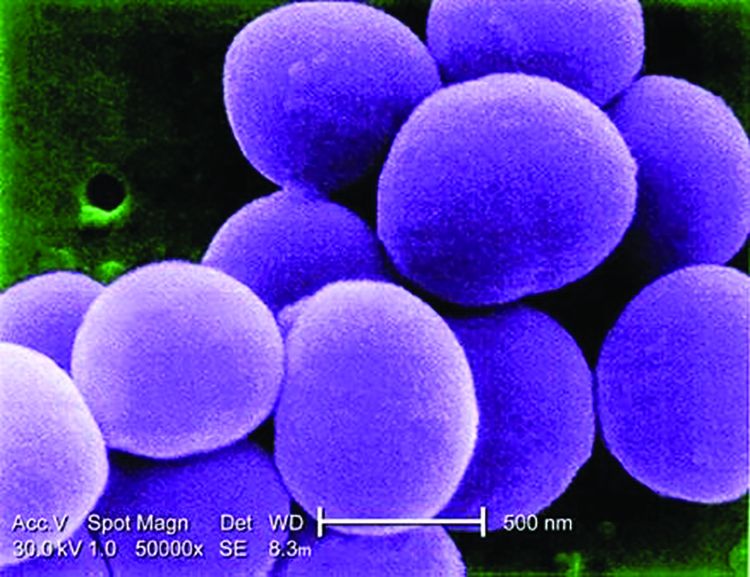

Two consecutive negative FUBC results clear S. aureus bacteremia

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

reported Caitlin Cardenas-Comfort, MD, of the section of pediatric infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues.

In a retrospective cohort study of 122 pediatric patients with documented Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) that were hospitalized at one of three hospitals in the Texas Children’s Hospital network in Houston, Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues sought to determine whether specific recommendations can be made on the number of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) needed to document clearance of SAB. Patients included in the study were under 18 years of age and had confirmed diagnosis of SAB between Jan. 1, and Dec. 31, 2018.

Most cases of bacteremia resolve in under 48 hours

In the majority of cases, patients had bacteremia for less than 48 hours and few to no complications. Only 16% of patients experienced bacteremia lasting 3 or more days, and they had either central line-associated bloodstream infection, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis. In such cases, “patients with endovascular and closed-space infections are at an increased risk of persistent bacteremia,” warranting more conservative monitoring and follow-up, cautioned the researchers.

Although Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues did note an association between the duration of bacteremia and a diagnosis of infectious disease, increased risk for persistent SAB did not appear to be tied to an underlying medical condition, including immunosuppression.

Fewer than 5% of patients with SAB had intermittent positive cultures and fewer than 1% had repeat positive cultures following two negative FUBC results. For those patients with intermittent positive cultures, the risk of being diagnosed with endocarditis or osteomyelitis is more than double. The authors suggested that “source control could be a critical variable” increasing the risk for intermittent positive cultures, noting that surgical debridement occurred more than 24 hours following initial blood draw for every patient in the osteomyelitis group. In contrast, of those who had consistently negative FUBC results, only 2 of 33 (6%) had debridement in the same period, and only 6 of 33 (18%) required more than one debridement.

Children are less likely to have intermittent positive cultures

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues also observed that intermittent positive cultures may appear less frequently in children than adults, consistent with a recent study of adults in which intermittent cultures were found in 13% of 1.071 SAB cases. In just 4% of the cases in that study, more than 2 days of negative blood cultures preceded a repeat positive culture.

The researchers noted several study limitations in their own research. Because more than half (61%) of patients had two or less FUBCs collected, and 21% one or less, they acknowledged that their conclusions are based on the presumption that the 61% of patients would not have any further positive cultures if they had been drawn. Relying on provider documentation also suggested that cases of bacteremia without an identified source also likely were overrepresented. The retrospective nature of the study only allowed for limited collection of standardized follow-up metrics with the limited patient sample available. Patient characteristics also may have affected the quality of study results because a large number of patients had underlying medical conditions or were premature infants.

Look for ongoing hemodynamic instability before third FUBC

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues only recommend a third FUBC in cases where patients demonstrate ongoing hemodynamic instability. Applying this to their study population, in retrospect, the authors noted that unnecessary FUBCs could have been prevented in 26% of patients included in the study. They further recommend a thorough clinical evaluation for any patients with SAB lasting 3 or more days with an unidentified infection source. Further research could be beneficial in evaluating cost savings that come from eliminating unnecessary cultures. Additionally, performing a powered analysis would help to determine the probability of an increase in complications based on implementation of these recommendations.

In a separate interview, Tina Q. Tan, MD, infectious disease specialist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago noted: “This study provides some importance evidence-based guidance on deciding how many blood cultures are needed to demonstrate clearance of S. aureus bacteremia, even in children who have intermittent positive cultures after having negative FUBCs. The recommendation that additional blood cultures to document sterility are not needed after 2 FUBC results are negative in well-appearing children is one that has the potential to decrease cost and unnecessary discomfort in patients. The recommendation currently is for well-appearing children; children who are ill appearing may require further blood cultures to document sterility. Even though this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients (n = 122), the information provided is a very useful guide to all clinicians who deal with this issue. Further studies are needed to determine the impact on cost reduction by the elimination of unnecessary blood cultures and whether the rate of complications would increase as a result of not obtaining further cultures in well-appearing children who have two negative follow up blood cultures.”

Dr. Cardenas-Comfort and colleagues as well as Dr. Tan had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding for the study.

SOURCE: Cardenas-Comfort C et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1821.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Challenges in the Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Abstract

Objective: To review current challenges in the management of peptic ulcer disease.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Peptic ulcer disease affects 5% to 10% of the population worldwide, with recent decreases in lifetime prevalence in high-income countries. Helicobacter pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use are the most important drivers of peptic ulcer disease. Current management strategies for peptic ulcer disease focus on ulcer healing; management of complications such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction; and prevention of ulcer recurrence. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcers, and complement testing for and treatment of H. pylori infection as well as elimination of NSAID use. Although advances have been made in the medical and endoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer disease and the management of ulcer complications, such as bleeding and obstruction, challenges remain.

Conclusion: Peptic ulcer disease is a common health problem globally, with persistent challenges related to refractory ulcers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use, and continued bleeding in the face of endoscopic therapy. These challenges should be met with PPI therapy of adequate frequency and duration, vigilant attention to and treatment of ulcer etiology, evidence-based handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, and utilization of novel endoscopic tools to obtain improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: H. pylori; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSAIDs; proton pump inhibitor; PPI; bleeding; perforation; obstruction; refractory ulcer; salvage endoscopic therapy; transcatheter angiographic embolization.

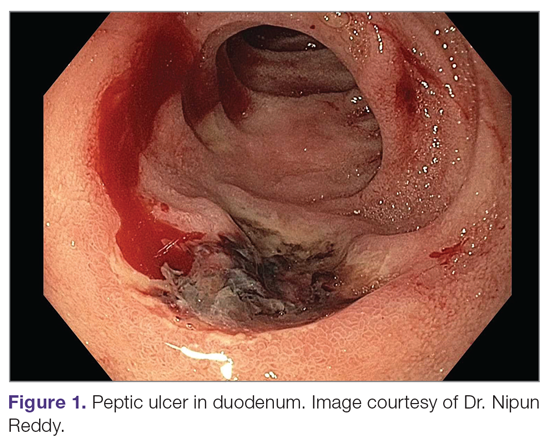

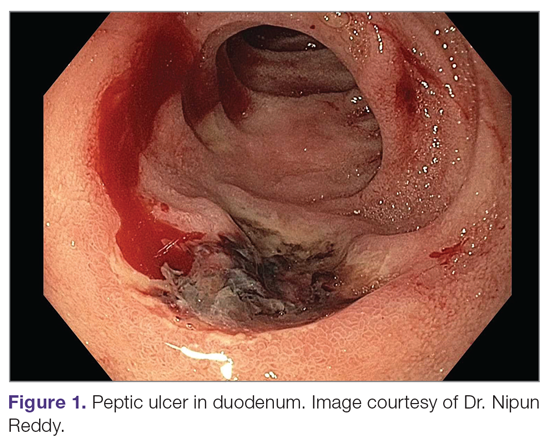

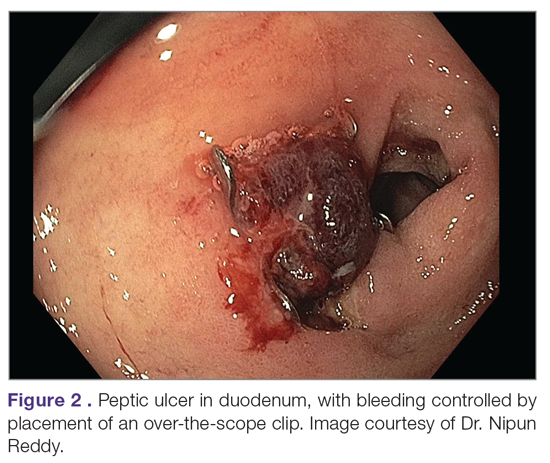

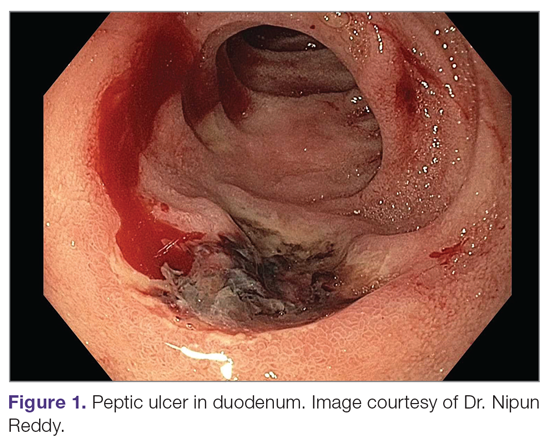

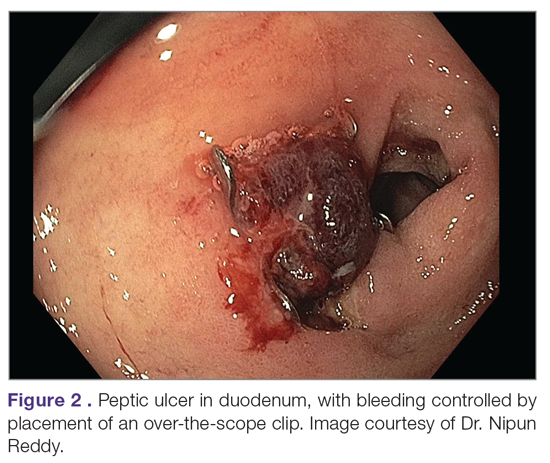

A peptic ulcer is a fibrin-covered break in the mucosa of the digestive tract extending to the submucosa that is caused by acid injury (Figure 1). Most peptic ulcers occur in the stomach or proximal duodenum, though they may also occur in the esophagus or, less frequently, in a Meckel’s diverticulum.1,2 The estimated worldwide prevalence of peptic ulcer disease is 5% to 10%, with an annual incidence of 0.1% to 0.3%1; both rates are declining.3 The annual incidence of peptic ulcer disease requiring medical or surgical treatment is also declining, and currently is estimated to be 0.1% to 0.2%.4 The lifetime prevalence of peptic ulcers has been decreasing in high-income countries since the mid-20th century due to both the widespread use of medications that suppress gastric acid secretion and the declining prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection.1,3

Peptic ulcer disease in most individuals results from H. pylori infection, chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, or both. A combination of H. pylori factors and host factors lead to mucosal disruption in infected individuals who develop peptic ulcers. H. pylori–specific factors include the expression of virulence factors such as CagA and VacA, which interact with the host inflammatory response to cause mucosal injury. The mucosal inflammatory response is at least partially determined by polymorphisms in the host’s cytokine genes.1,4 NSAIDs inhibit the production of cyclooxygenase-1-derived prostaglandins, with subsequent decreases in epithelial mucous formation, bicarbonate secretion, cell proliferation, and mucosal blood flow, all of which are key elements in the maintenance of mucosal integrity.1,5 Less common causes of peptic ulcers include gastrinoma, adenocarcinoma, idiopathic ulcers, use of sympathomimetic drugs (eg, cocaine or methamphetamine), certain anticancer agents, and bariatric surgery.4,6

This article provides an overview of current management principles for peptic ulcer disease and discusses current challenges in peptic ulcer management, including proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, refractory ulcers, handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulants during and after peptic ulcer bleeding, and ulcer bleeding that continues despite salvage endoscopic therapy.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE using the term peptic ulcer disease in combination with the terms current challenges, epidemiology, bleeding, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, PPI potency, etiology, treatment, management, and refractory. We selected publications from the past 35 years that we judged to be relevant.

Current Management

The goals of peptic ulcer disease management are ulcer healing and prevention of recurrence. The primary interventions used in the management of peptic ulcer disease are medical therapy and implementation of measures that address the underlying etiology of the disease.

Medical Therapy

Introduced in the late 1980s, PPIs are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcer disease.6 These agents irreversibly inhibit the H+/K+-ATPase pump in the gastric mucosa and thereby inhibit gastric acid secretion, promoting ulcer healing. PPIs improve rates of ulcer healing compared to H2-receptor antagonists.4,7

Underlying Causes

The underlying cause of peptic ulcer disease should be addressed, in addition to initiating medical therapy. A detailed history of NSAID use should be obtained, and patients with peptic ulcers caused by NSAIDs should be counseled to avoid them, if possible. Patients with peptic ulcer disease who require long-term use of NSAIDs should be placed on long-term PPI therapy.6 Any patient with peptic ulcer disease, regardless of any history of H. pylori infection or treatment, should be tested for infection. Tests that identify active infection, such as urea breath test, stool antigen assay, or mucosal biopsy–based testing, are preferred to IgG antibody testing, although the latter is acceptable in the context of peptic ulcer disease with a high pretest probability of infection.8 Any evidence of active infection warrants appropriate treatment to allow ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.1H. pylori infection is most often treated with clarithromycin triple therapy or bismuth quadruple therapy for 14 days, with regimens selected based on the presence or absence of penicillin allergy, prior antibiotic exposure, and local clarithromycin resistance rates, when known.4,8

Managing Complications

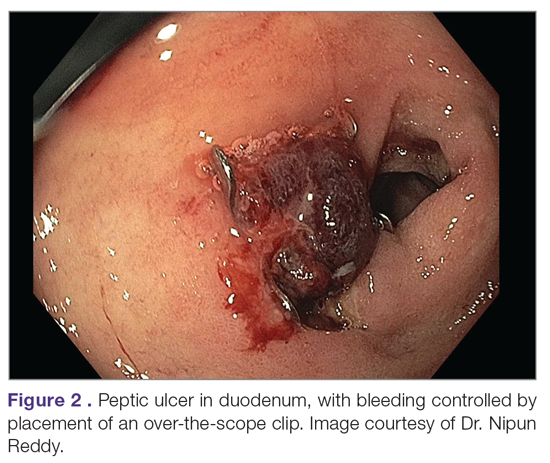

An additional aspect of care in peptic ulcer disease is managing the complications of bleeding, perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease, which accounts for 40% to 60% of nonvariceal acute upper GIB.1,6 The first step in the management of acute GIB from a peptic ulcer is fluid resuscitation to ensure hemodynamic stability. If there is associated anemia with a hemoglobin level < 8 g/dL, blood transfusion should be undertaken to target a hemoglobin level > 8 g/dL. In patients with peptic ulcer disease–related acute upper GIB and comorbid cardiovascular disease, the transfusion threshold is higher, with the specific cutoff depending on clinical status, type and severity of cardiovascular disease, and degree of bleeding. Endoscopic management should generally be undertaken within 24 hours of presentation and should not be delayed in patients taking anticoagulants.9 Combination endoscopic treatment with through-the-scope clips plus thermocoagulation or sclerosant injection is recommended for acutely bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata.

Pharmacologic management of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata includes PPI therapy, with an 80 mg intravenous (IV) loading dose followed by continuous infusion of 8 mg/hr for 72 hours to reduce rebleeding and mortality. Following completion of IV therapy, oral PPI therapy should be continued twice daily for 14 days, followed by once-daily dosing thereafter.9Patients with peptic ulcer perforation present with sudden-onset epigastric abdominal pain and have tenderness to palpation, guarding, and rigidity on examination, often along with tachycardia and hypotension.1,4 Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen is 98% sensitive for identifying and localizing a perforation. Most perforations occur in the duodenum or antrum.

Management of a peptic ulcer perforation requires consultation with a surgeon to determine whether a nonoperative approach may be employed (eg, a stable patient with a contained perforation), or if surgery is indicated. The surgical approach to peptic ulcer perforation has been impacted by the clinical success of gastric acid suppression with PPIs and H. pylori eradication, but a range of surgical approaches are still used to repair perforations, from omental patch repair with peritoneal drain placement, to more extensive surgeries such as wedge resection or partial gastrectomy.4 Perforation carries a high mortality risk, up to 20% to 30%, and is the leading cause of death in patients with peptic ulcer disease.1,4

Gastric outlet obstruction, a rare complication of peptic ulcer disease, results from recurrent ulcer formation and scarring. Obstruction often presents with hypovolemia and metabolic alkalosis from prolonged vomiting. CT imaging with oral contrast is often the first diagnostic test employed to demonstrate obstruction. Upper endoscopy should be performed to evaluate the appearance and degree of obstruction as well as to obtain biopsies to evaluate for a malignant etiology of the ulcer disease. Endoscopic balloon dilation has become the cornerstone of initial therapy for obstruction from peptic ulcer disease, especially in the case of ulcers due to reversible causes. Surgery is now typically reserved for cases of refractory obstruction, after repeated endoscopic balloon dilation has failed to remove the obstruction. However, because nearly all patients with gastric outlet obstruction present with malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies should be addressed prior to the patient undergoing surgical intervention. Surgical options include pyloroplasty, antrectomy, and gastrojejunostomy.4

Current Challenges

Rapid Metabolism of PPIs

High-dose PPI therapy is a key component of therapy for peptic ulcer healing. PPIs are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, which is comprised of multiple isoenzymes. CYP2C19, an isoenzyme involved in PPI metabolism, has 21 polymorphisms, which have variable effects leading to ultra-rapid, extensive, intermediate, or poor metabolism of PPIs.10 With rapid metabolism of PPIs, standard dosing can result in inadequate suppression of acid secretion. Despite this knowledge, routine testing of CYP2C19 phenotype is not recommended due to the cost of testing. Instead, inadequate ulcer healing should prompt consideration of increased PPI dosing to 80 mg orally twice daily, which may be sufficient to overcome rapid PPI metabolism.11

Relative Potency of PPIs

In addition to variation in PPI metabolism, the relative potency of various PPIs has been questioned. A review of all available clinical studies of the effects of PPIs on mean 24-hour intragastric pH reported a quantitative difference in the potency of 5 PPIs, with omeprazole as the reference standard. Potencies ranged from 0.23 omeprazole equivalents for pantoprazole to 1.82 omeprazole equivalents for rabeprazole.12 An additional study of data from 56 randomized clinical trials confirmed that PPIs vary in potency, which was measured as time that gastric pH is less than 4. A linear increase in intragastric pH time less than 4 was observed from 9 to 64 mg omeprazole equivalents; higher doses yielded no additional benefit. An increase in PPI dosing from once daily to twice daily also increased the duration of intragastric pH time less than 4 from 15 to 21 hours.13 Earlier modeling of the relationship between duodenal ulcer healing and antisecretory therapy showed a strong correlation of ulcer healing with the duration of acid suppression, length of therapy, and the degree of acid suppression. Additional benefit was not observed after intragastric pH rose above 3.14 Thus, as the frequency and duration of acid suppression therapy are more important than PPI potency, PPIs can be used interchangeably.13,14

Addressing Underlying Causes

Continued NSAID Use. Refractory peptic ulcers are defined as those that do not heal despite adherence to 8 to 12 weeks of standard acid-suppression therapy. A cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease that must be considered is continued NSAID use.1,15 In a study of patients with refractory peptic ulcers, 27% of patients continued NSAID use, as determined by eventual disclosure by the patients or platelet cyclooxygenase activity assay, despite extensive counseling to avoid NSAIDs at the time of the diagnosis of their refractory ulcer and at subsequent visits.16 Pain may make NSAID cessation difficult for some patients, while others do not realize that over-the-counter preparations they take contain NSAIDs.15

Another group of patients with continued NSAID exposure are those who require long-term NSAID therapy for control of arthritis or the management of cardiovascular conditions. If NSAID therapy cannot be discontinued, the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal injury can be assessed based on the presence of multiple risk factors, including age > 65 years, high-dose NSAID therapy, a history of peptic ulcer, and concurrent use of aspirin, corticosteroids, or anticoagulants. Individuals with 3 or more of the preceding risk factors or a history of a peptic ulcer with a complication, especially if recent, are considered to be at high risk of developing an NSAID-related ulcer and possible subsequent complications.17 In these individuals, NSAID therapy should be continued with agents that have the lowest risk for gastrointestinal toxicity and at the lowest possible dose. A meta-analysis comparing nonselective NSAIDs to placebo demonstrated naproxen to have the highest risk of gastrointestinal complications, including GIB, perforation, and obstruction (adjusted rate ratio, 4.2), while diclofenac demonstrated the lowest risk (adjusted rate ratio, 1.89). High-dose NSAID therapy demonstrated a 2-fold increase in risk of peptic ulcer formation as compared to low-dose therapy.18

In addition to selecting the NSAID with the least gastrointestinal toxicity at the lowest possible dose, additional strategies to prevent peptic ulcer disease and its complications in chronic NSAID users include co-administration of a PPI and substitution of a COX-2 selective NSAID for nonselective NSAIDs.1,9 Prior double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trials with patients requiring daily NSAIDs demonstrated an up to 15% absolute reduction in the risk of developing peptic ulcers over 6 months while taking esomeprazole.19

Persistent Infection. Persistent H. pylori infection, due either to initial false-negative testing or ongoing infection despite first-line therapy, is another cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease.1,15 Because antibiotics and PPIs can reduce the number of H. pylori bacteria, use of these medications concurrent with H. pylori testing can lead to false-negative results with several testing modalities. When suspicion for H. pylori is high, 2 or more diagnostic tests may be needed to effectively rule out infection.15

When H. pylori is detected, successful eradication is becoming more difficult due to an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance, leading to persistent infection in many cases and maintained risk of peptic ulcer disease, despite appropriate first-line therapy.8 Options for salvage therapy for persistent H. pylori, as well as information on the role and best timing of susceptibility testing, are beyond the scope of this review, but are reviewed by Lanas and Chan1 and in the American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the treatment of H. pylori infection.8

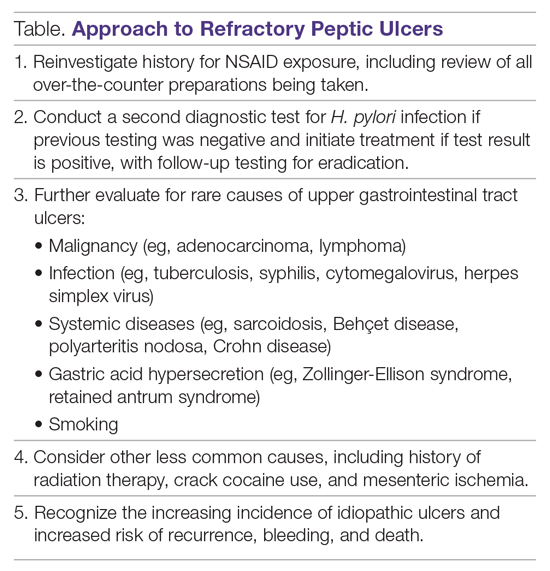

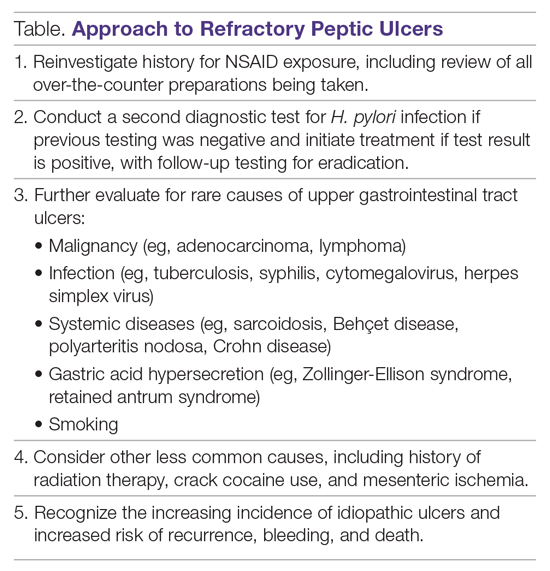

Other Causes. In a meta-analysis of rigorously designed studies from North America, 20% of patients experienced ulcer recurrence at 6 months, despite successful H. pylori eradication and no NSAID use.20 In addition, as H. pylori prevalence is decreasing, idiopathic ulcers are increasingly being diagnosed, and such ulcers may be associated with high rates of GIB and mortality.1 In this subset of patients with non-H. pylori, non-NSAID ulcers, increased effort is required to further evaluate the differential diagnosis for rarer causes of upper GI tract ulcer disease (Table). Certain malignancies, including adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, can cause ulcer formation and should be considered in refractory cases. Repeat biopsy at follow-up endoscopy for persistent ulcers should always be obtained to further evaluate for malignancy.1,15 Infectious diseases other than H. pylori infection, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus, are also reported as etiologies of refractory ulcers, and require specific antimicrobial treatment over and above PPI monotherapy. Special attention in biopsy sampling and sample processing is often required when infectious etiologies are being considered, as specific histologic stains and cultures may be needed for identification.15

Systemic conditions, including sarcoidosis,21 Behçet disease,22 and polyarteritis nodosa,15,23 can also cause refractory ulcers. Approximately 15% of patients with Crohn disease have gastroduodenal involvement, which may include ulcers of variable sizes.1,15,24 The increased gastric acid production seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome commonly presents as refractory peptic ulcers in the duodenum beyond the bulb that do not heal with standard doses of PPIs.1,15 More rare causes of acid hypersecretion leading to refractory ulcers include idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion and retained gastric antrum syndrome after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis.15 Smoking is a known risk factor for impaired tissue healing throughout the body, and can contribute to impaired healing of peptic ulcers through decreased prostaglandin synthesis25 and reduced gastric mucosal blood flow.26 Smoking should always be addressed in patients with refractory peptic ulcers, and cessation should be strongly encouraged. Other less common causes of refractory upper GI tract ulcers include radiation therapy, crack cocaine use, and mesenteric ischemia.15

Managing Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications

Use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants, alone or in combination, increases the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. In patients who continue to take aspirin after a peptic ulcer bleed, recurrent bleeding occurs in up to 300 cases per 1000 person-years. The rate of GIB associated with aspirin use ranges from 1.1% to 2.5%, depending on the dose. Prior peptic ulcer disease, age greater than 70 years, and concurrent NSAID, steroid, anticoagulant, or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) use increase the risk of bleeding while on aspirin. The rate of GIB while taking a thienopyridine alone is slightly less than that when taking aspirin, ranging from 0.5% to 1.6%. Studies to date have yielded mixed estimates of the effect of DAPT on the risk of GIB. Estimates of the risk of GIB with DAPT range from an odds ratio for serious GIB of 7.4 to an absolute risk increase of only 1.3% when compared to clopidogrel alone.27

Many patients are also on warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC). In a study from the United Kingdom, the adjusted rate ratio of GIB with warfarin alone was 1.94, and this increased to 6.48 when warfarin was used with aspirin.28 The use of warfarin and DAPT, often called triple therapy, further increases the risk of GIB, with a hazard ratio of 5.0 compared to DAPT alone, and 5.38 when compared to warfarin alone. DOACs are increasingly prescribed for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism, and by 2014 were prescribed as often as warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in the United States. A meta-analysis showed the risk of major GIB did not differ between DOACs and warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin, but among DOACs factor Xa inhibitors showed a reduced risk of GIB compared with dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor.29

The use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants in the context of peptic ulcer bleeding is a current management challenge. Data to guide decision-making in patients on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy who experience peptic ulcer bleeding are scarce. Decision-making in this group of patients requires balancing the severity and risk of bleeding with the risk of thromboembolism.1,27 In patients on antiplatelet therapy for primary prophylaxis of atherothrombosis who develop bleeding from a peptic ulcer, the antiplatelet should generally be held and the indication for the medication reassessed. In patients on antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention, the agent may be immediately resumed after endoscopy if bleeding is found to be due to an ulcer with low-risk stigmata. With bleeding resulting from an ulcer with high-risk stigmata, antiplatelet agents employed for secondary prevention may be held initially, with consideration given to early reintroduction, as early as day 3 after endoscopy.1 In patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events, including those on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis, withholding aspirin leads to a 3-fold increase in the risk of a major adverse cardiac event, with events occurring as early as 5 days after aspirin cessation in some cases.27 A randomized controlled trial of continuing low-dose aspirin versus withholding it for 8 weeks in patients on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular events who experienced peptic ulcer bleeding that required endoscopic therapy demonstrated lower all-cause mortality (1.3% vs 12.9%), including death from cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events, among those who continued aspirin therapy, with a small increased risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding (10.3% vs 5.4%).30 Thus, it is recommended that antiplatelet therapy, when held, be resumed as early as possible when the risk of a cardiovascular or cerebrovascular event is considered to be higher than the risk of bleeding.27

When patients are on DAPT for a history of drug-eluting stent placement, withholding both antiplatelet medications should be avoided, even for a brief period of time, given the risk of in-stent thrombosis. When DAPT is employed for other reasons, it should be continued, if indicated, after bleeding that is found to be due to peptic ulcers with low-risk stigmata. If bleeding is due to a peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata at endoscopy, then aspirin monotherapy should be continued and consultation should be obtained with a cardiologist to determine optimal timing to resume the second antiplatelet agent.1 In patients on anticoagulants, anticoagulation should be resumed once hemostasis is achieved when the risk of withholding anticoagulation is thought to be greater than the risk of rebleeding. For example, anticoagulation should be resumed early in a patient with a mechanical heart valve to prevent thrombosis.1,27 Following upper GIB from peptic ulcer disease, patients who will require long-term aspirin, DAPT, or anticoagulation with either warfarin or DOACs should be maintained on long-term PPI therapy to reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding.9,27

Failure of Endoscopic Therapy to Control Peptic Ulcer Bleeding