User login

2021 ACIP adult schedule released

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has updated its recommended immunization schedule for adults for 2021.

A summary of the annual update was published online Feb. 11 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and is available in Annals of Internal Medicine and on the CDC website.

It features a special section on vaccination during the pandemic as well as interim recommendations on administering the Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

The authors, led by Mark S. Freedman, DVM, MPH, DACVPM, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, in Atlanta, note that this year’s recommendations for adults – persons aged 19 years and older – are largely the same as last year’s. “There have been very few changes,” Dr. Freedman said in an interview. “Changes to the schedule tables and notes were made to harmonize to the greatest extent possible the adult and child/adolescent schedules.”

Changes in the schedule include new or updated ACIP recommendations for influenza, hepatitis A, hepatitis B (Hep B), and human papillomavirus (HPV) as well as for meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, and Y (MenACYW) vaccines, meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines, and the zoster vaccine.

Vaccine-specific changes

Influenza

The schedule highlights updates to the composition of several influenza vaccines, which apply to components in both trivalent and quadrivalent formulations.

The cover page abbreviation for live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was changed to LAIV4. The abbreviation for live recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV) was changed to RIV4.

For individuals with a history of egg allergy who experience reactions other than hives, the following procedural warning has been added: “If using an influenza vaccine other than RIV4 or ccIIV4, administer in medical setting under supervision of health care provider who can recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.”

Zoster

The zoster vaccine live (Zostavax) has been removed from the schedule because it is no longer available in the United States. The recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix remains available as a 2-dose regimen for adults aged 50 years or older.

HPV

As in previous years, HPV vaccination is routinely recommended for persons aged 11-12 years, with catch-up vaccination for those aged 26 or younger. Catch-up vaccination can be considered with shared decision making for those aged 27 through 45. In this year’s schedule, in the pregnancy column, the color pink, which formerly indicated “delay until after pregnancy,” has been replaced with red and an asterisk, indicating “vaccinate after pregnancy.”

HepB

ACIP continues to recommend vaccination of adults at risk for HepB; however, the text overlay has been changed to read, “2, 3, or 4 doses, depending on vaccine or condition.” Additionally, HepB vaccination is now routinely recommended for adults younger than 60 years with diabetes. For those with diabetes who are older than 60, shared decision making is recommended.

Meningococcal vaccine

ACIP continues to recommend routine vaccination with a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY) for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease caused by serogroups A, C, W, or Y. The MenQuadfi (MenACWY-TT) vaccine, which was first licensed in 2020, has been added to all relevant sections of MenACWY vaccines. For MenACWY booster doses, new text addresses special situations, including outbreaks.

Improvements have been made to text and layout, Dr. Freedman said. An example is the minimizing of specialized text. Other changes were made to ensure more consistent text structure and language. Various fine-tunings of color and positioning were made to the cover page and tables, and the wording of the notes sections was improved.

Vaccination in the pandemic

The updated schedule outlines guidance on the use of COVID-19 vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration under emergency use authorization, with interim recommendations for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 16 and older and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The authors stress the importance of receiving the recommended routine and catch-up immunizations notwithstanding widespread anxiety about visiting medical offices. Last spring, the CDC reported a dramatic drop in child vaccinations after the declaration of the national emergency in mid-March, a drop attributed to fear of COVID-19 exposure.

“ACIP continued to meet and make recommendations during the pandemic,” Dr. Freedman said. “Our recommendation remains that despite challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, adults and their healthcare providers should follow the recommended vaccine schedule to protect against serious and sometimes deadly diseases.”

Regular vaccines can be safely administered even as COVID-19 retains its grasp on the United States. “Healthcare providers should follow the CDC’s interim guidance for the safe delivery of vaccines during the pandemic, which includes the use of personal protective equipment and physical distancing,” Dr. Freedman said.

Dr. Freedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor Henry Bernstein, DO, is the editor of the Current Opinion in Pediatrics Office Pediatrics Series, is a Harvard School of Public Health faculty member, and is a member of the data safety and monitoring board for a Takeda study on intrathecal enzymes for Hunter and San Filippo syndromes. Coauthor Kevin Ault, MD, has served on the data safety and monitoring committee for ACI Clinical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has updated its recommended immunization schedule for adults for 2021.

A summary of the annual update was published online Feb. 11 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and is available in Annals of Internal Medicine and on the CDC website.

It features a special section on vaccination during the pandemic as well as interim recommendations on administering the Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

The authors, led by Mark S. Freedman, DVM, MPH, DACVPM, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, in Atlanta, note that this year’s recommendations for adults – persons aged 19 years and older – are largely the same as last year’s. “There have been very few changes,” Dr. Freedman said in an interview. “Changes to the schedule tables and notes were made to harmonize to the greatest extent possible the adult and child/adolescent schedules.”

Changes in the schedule include new or updated ACIP recommendations for influenza, hepatitis A, hepatitis B (Hep B), and human papillomavirus (HPV) as well as for meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, and Y (MenACYW) vaccines, meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines, and the zoster vaccine.

Vaccine-specific changes

Influenza

The schedule highlights updates to the composition of several influenza vaccines, which apply to components in both trivalent and quadrivalent formulations.

The cover page abbreviation for live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was changed to LAIV4. The abbreviation for live recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV) was changed to RIV4.

For individuals with a history of egg allergy who experience reactions other than hives, the following procedural warning has been added: “If using an influenza vaccine other than RIV4 or ccIIV4, administer in medical setting under supervision of health care provider who can recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.”

Zoster

The zoster vaccine live (Zostavax) has been removed from the schedule because it is no longer available in the United States. The recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix remains available as a 2-dose regimen for adults aged 50 years or older.

HPV

As in previous years, HPV vaccination is routinely recommended for persons aged 11-12 years, with catch-up vaccination for those aged 26 or younger. Catch-up vaccination can be considered with shared decision making for those aged 27 through 45. In this year’s schedule, in the pregnancy column, the color pink, which formerly indicated “delay until after pregnancy,” has been replaced with red and an asterisk, indicating “vaccinate after pregnancy.”

HepB

ACIP continues to recommend vaccination of adults at risk for HepB; however, the text overlay has been changed to read, “2, 3, or 4 doses, depending on vaccine or condition.” Additionally, HepB vaccination is now routinely recommended for adults younger than 60 years with diabetes. For those with diabetes who are older than 60, shared decision making is recommended.

Meningococcal vaccine

ACIP continues to recommend routine vaccination with a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY) for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease caused by serogroups A, C, W, or Y. The MenQuadfi (MenACWY-TT) vaccine, which was first licensed in 2020, has been added to all relevant sections of MenACWY vaccines. For MenACWY booster doses, new text addresses special situations, including outbreaks.

Improvements have been made to text and layout, Dr. Freedman said. An example is the minimizing of specialized text. Other changes were made to ensure more consistent text structure and language. Various fine-tunings of color and positioning were made to the cover page and tables, and the wording of the notes sections was improved.

Vaccination in the pandemic

The updated schedule outlines guidance on the use of COVID-19 vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration under emergency use authorization, with interim recommendations for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 16 and older and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The authors stress the importance of receiving the recommended routine and catch-up immunizations notwithstanding widespread anxiety about visiting medical offices. Last spring, the CDC reported a dramatic drop in child vaccinations after the declaration of the national emergency in mid-March, a drop attributed to fear of COVID-19 exposure.

“ACIP continued to meet and make recommendations during the pandemic,” Dr. Freedman said. “Our recommendation remains that despite challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, adults and their healthcare providers should follow the recommended vaccine schedule to protect against serious and sometimes deadly diseases.”

Regular vaccines can be safely administered even as COVID-19 retains its grasp on the United States. “Healthcare providers should follow the CDC’s interim guidance for the safe delivery of vaccines during the pandemic, which includes the use of personal protective equipment and physical distancing,” Dr. Freedman said.

Dr. Freedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor Henry Bernstein, DO, is the editor of the Current Opinion in Pediatrics Office Pediatrics Series, is a Harvard School of Public Health faculty member, and is a member of the data safety and monitoring board for a Takeda study on intrathecal enzymes for Hunter and San Filippo syndromes. Coauthor Kevin Ault, MD, has served on the data safety and monitoring committee for ACI Clinical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has updated its recommended immunization schedule for adults for 2021.

A summary of the annual update was published online Feb. 11 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and is available in Annals of Internal Medicine and on the CDC website.

It features a special section on vaccination during the pandemic as well as interim recommendations on administering the Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

The authors, led by Mark S. Freedman, DVM, MPH, DACVPM, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, in Atlanta, note that this year’s recommendations for adults – persons aged 19 years and older – are largely the same as last year’s. “There have been very few changes,” Dr. Freedman said in an interview. “Changes to the schedule tables and notes were made to harmonize to the greatest extent possible the adult and child/adolescent schedules.”

Changes in the schedule include new or updated ACIP recommendations for influenza, hepatitis A, hepatitis B (Hep B), and human papillomavirus (HPV) as well as for meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, and Y (MenACYW) vaccines, meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines, and the zoster vaccine.

Vaccine-specific changes

Influenza

The schedule highlights updates to the composition of several influenza vaccines, which apply to components in both trivalent and quadrivalent formulations.

The cover page abbreviation for live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was changed to LAIV4. The abbreviation for live recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV) was changed to RIV4.

For individuals with a history of egg allergy who experience reactions other than hives, the following procedural warning has been added: “If using an influenza vaccine other than RIV4 or ccIIV4, administer in medical setting under supervision of health care provider who can recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.”

Zoster

The zoster vaccine live (Zostavax) has been removed from the schedule because it is no longer available in the United States. The recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix remains available as a 2-dose regimen for adults aged 50 years or older.

HPV

As in previous years, HPV vaccination is routinely recommended for persons aged 11-12 years, with catch-up vaccination for those aged 26 or younger. Catch-up vaccination can be considered with shared decision making for those aged 27 through 45. In this year’s schedule, in the pregnancy column, the color pink, which formerly indicated “delay until after pregnancy,” has been replaced with red and an asterisk, indicating “vaccinate after pregnancy.”

HepB

ACIP continues to recommend vaccination of adults at risk for HepB; however, the text overlay has been changed to read, “2, 3, or 4 doses, depending on vaccine or condition.” Additionally, HepB vaccination is now routinely recommended for adults younger than 60 years with diabetes. For those with diabetes who are older than 60, shared decision making is recommended.

Meningococcal vaccine

ACIP continues to recommend routine vaccination with a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY) for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease caused by serogroups A, C, W, or Y. The MenQuadfi (MenACWY-TT) vaccine, which was first licensed in 2020, has been added to all relevant sections of MenACWY vaccines. For MenACWY booster doses, new text addresses special situations, including outbreaks.

Improvements have been made to text and layout, Dr. Freedman said. An example is the minimizing of specialized text. Other changes were made to ensure more consistent text structure and language. Various fine-tunings of color and positioning were made to the cover page and tables, and the wording of the notes sections was improved.

Vaccination in the pandemic

The updated schedule outlines guidance on the use of COVID-19 vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration under emergency use authorization, with interim recommendations for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 16 and older and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for people aged 18 and older.

The authors stress the importance of receiving the recommended routine and catch-up immunizations notwithstanding widespread anxiety about visiting medical offices. Last spring, the CDC reported a dramatic drop in child vaccinations after the declaration of the national emergency in mid-March, a drop attributed to fear of COVID-19 exposure.

“ACIP continued to meet and make recommendations during the pandemic,” Dr. Freedman said. “Our recommendation remains that despite challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, adults and their healthcare providers should follow the recommended vaccine schedule to protect against serious and sometimes deadly diseases.”

Regular vaccines can be safely administered even as COVID-19 retains its grasp on the United States. “Healthcare providers should follow the CDC’s interim guidance for the safe delivery of vaccines during the pandemic, which includes the use of personal protective equipment and physical distancing,” Dr. Freedman said.

Dr. Freedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor Henry Bernstein, DO, is the editor of the Current Opinion in Pediatrics Office Pediatrics Series, is a Harvard School of Public Health faculty member, and is a member of the data safety and monitoring board for a Takeda study on intrathecal enzymes for Hunter and San Filippo syndromes. Coauthor Kevin Ault, MD, has served on the data safety and monitoring committee for ACI Clinical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Expert calls for paradigm shift in lab monitoring of some dermatology drugs

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

FROM ODAC 2021

Is COVID-19 accelerating progress toward high-value care?

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

COVID-19 in children: New cases down for third straight week

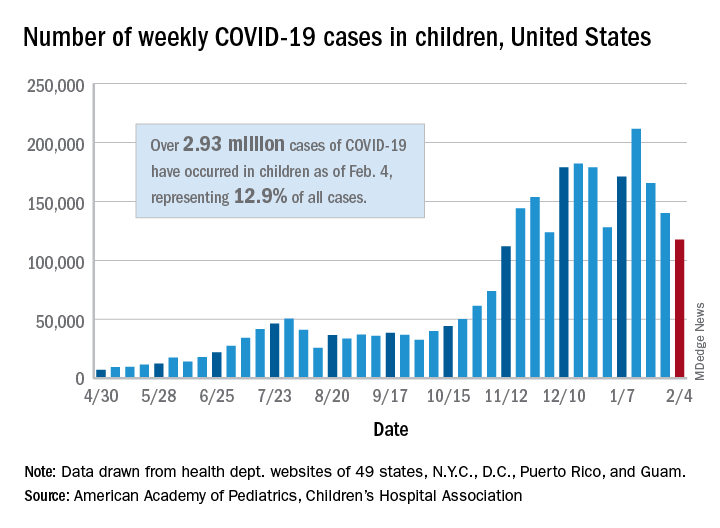

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

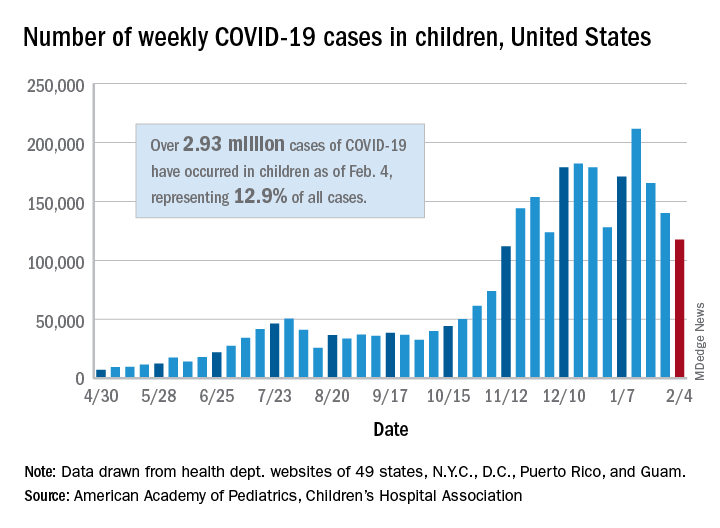

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

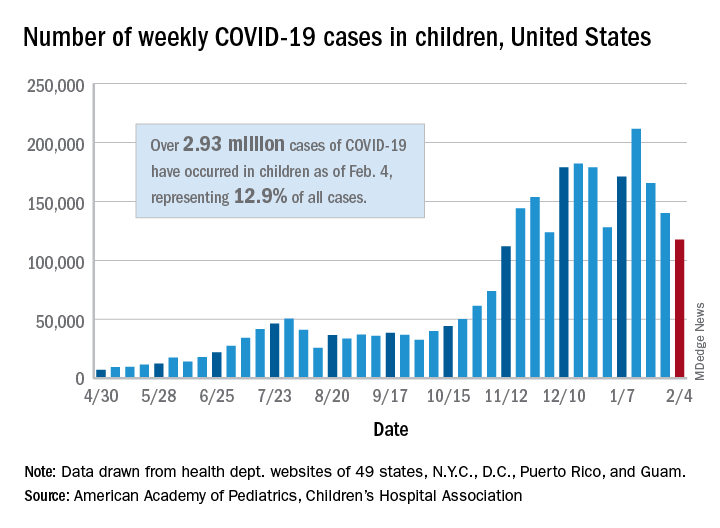

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

U.K. COVID-19 variant doubling every 10 days in the U.S.: Study

The SARS-CoV-2 variant first detected in the United Kingdom is rapidly becoming the dominant strain in several countries and is doubling every 10 days in the United States, according to new data.

The findings by Nicole L. Washington, PhD, associate director of research at the genomics company Helix, and colleagues were posted Feb. 7, 2021, on the preprint server medRxiv. The paper has not been peer-reviewed in a scientific journal.

The researchers also found that the transmission rate in the United States of the variant, labeled B.1.1.7, is 30%-40% higher than that of more common lineages.

While clinical outcomes initially were thought to be similar to those of other SARS-CoV-2 variants, early reports suggest that infection with the B.1.1.7 variant may increase death risk by about 30%.

A coauthor of the current study, Kristian Andersen, PhD, told the New York Times , “Nothing in this paper is surprising, but people need to see it.”

Dr. Andersen, a virologist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., added that “we should probably prepare for this being the predominant lineage in most places in the United States by March.”

The study of the B.1.1.7 variant adds support for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prediction in January that it would dominate by March.

“Our study shows that the U.S. is on a similar trajectory as other countries where B.1.1.7 rapidly became the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant, requiring immediate and decisive action to minimize COVID-19 morbidity and mortality,” the researchers wrote.

The authors pointed out that the B.1.1.7 variant became the dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain in the United Kingdom within a couple of months of its detection.

“Since then, the variant has been increasingly observed across many European countries, including Portugal and Ireland, which, like the U.K., observed devastating waves of COVID-19 after B.1.1.7 became dominant,” the authors wrote.

“Category 5” storm

The B.1.1.7 variant has likely been spreading between U.S. states since at least December, they wrote.

This news organization reported on Jan. 15 that, as of Jan. 13, the B.1.1.7 variant was seen in 76 cases across 12 U.S. states, according to an early release of the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

As of Feb. 7, there were 690 cases of the B.1.1.7 variant in the US in 33 states, according to the CDC.

Dr. Washington and colleagues examined more than 500,000 coronavirus test samples from cases across the United States that were tested at San Mateo, Calif.–based Helix facilities since July.

In the study, they found inconsistent prevalence of the variant across states. By the last week in January, the researchers estimated the proportion of B.1.1.7 in the U.S. population to be about 2.1% of all COVID-19 cases, though they found it made up about 2% of all COVID-19 cases in California and about 4.5% of cases in Florida. The authors acknowledged that their data is less robust outside of those two states.

Though that seems a relatively low frequency, “our estimates show that its growth rate is at least 35%-45% increased and doubling every week and a half,” the authors wrote.

“Because laboratories in the U.S. are only sequencing a small subset of SARS-CoV-2 samples, the true sequence diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in this country is still unknown,” they noted.