User login

When to screen asymptomatic diabetics for CAD

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The use of coronary artery calcium screening in the subset of asymptomatic diabetes patients at higher clinical risk of CAD appears to offer a practical strategy for identifying a subgroup in whom costlier stress cardiac imaging may be justified, Marcelo F. di Carli, MD, said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The ultimate goal is to reliably identify those patients who have asymptomatic diabetes with significant CAD warranting revascularization or maximal medical therapy for primary cardiovascular prevention.

“Coronary artery calcium is a simple test that’s accessible and inexpensive and can give us a quick read on the extent of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries,” said Dr. di Carli, professor of radiology and medicine at Harvard University in Boston. “There’s good data that in diabetic patients there’s a gradation of risk across the spectrum of calcium scores. Risk increases exponentially from a coronary artery calcium score of 0 to more than 400. The calcium score can also provide a snapshot of which patients are more likely to have flow-limiting coronary disease.”

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the biggest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of diabetes, and diabetes experts are eager to avoid jacking up those costs further by routinely ordering stress nuclear imaging, stress echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and other expensive noninvasive imaging methods unless they can be shown to lead to improved outcomes. There is general agreement on the value of noninvasive imaging in diabetic patients with CAD symptoms. However, the routine use of such testing in asymptomatic diabetic patients has been controversial.

Indeed, according to the 2017 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes: “In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for coronary artery disease is not recommended as it does not improve outcomes as long as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors are treated (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl. 1]:S75-87). That’s a Level A recommendation.

But Dr. di Carli is among many cardiologists who believe this statement paints with too broad a brush. He considers it an overgeneralization that’s based on the negative results of two randomized trials of routine screening in asymptomatic diabetics: DIAD, which utilized stress single-photon emission CT (SPECT) imaging (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55), and FACTOR-64, which relied upon coronary CT angiography (JAMA. 2014 Dec 3;312[21]: 2234-43). Both studies found relatively low yields of severe CAD and showed no survival benefit for screening. And of course, these are also costly and inconvenient tests.

The problem in generalizing from DIAD and FACTOR-64 to the overall population of asymptomatic diabetic patients is that both studies were conducted in asymptomatic patients at the lower end of the cardiovascular risk spectrum. They were young, with an average age of 60 years. They had a history of diabetes of less than 10 years, and their diabetes was reasonably well controlled. They had normal ECGs and preserved renal function. Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was present in only 9% of the DIAD population and no one in FACTOR-64. So this would not be expected to be a high-risk/high-yield population, according to Dr. di Carli, executive director of the cardiovascular imaging program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

An earlier study from the Mayo Clinic identified the clinical factors that can potentially be used to identify a higher-risk cohort of asymptomatic diabetic patients in whom high-tech noninvasive testing for significant CAD may be justified, he continued. This was a nonrandomized study of 1,427 asymptomatic diabetic patients without known CAD who underwent SPECT imaging. Compared with the study populations in DIAD and FACTOR-64, the Mayo Clinic patients had a longer duration of diabetes and substantially higher rates of poor diabetes control, renal dysfunction, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. One-third of them had PAD.

Fifty-eight percent of the 1,427 patients in the Mayo cohort proved to have an abnormal SPECT imaging scan, and 18% had a high-risk scan. In a multivariate analysis, the investigators identified several factors independently associated with a high-risk scan. Q waves were present on the ECGs of 9% of the asymptomatic diabetes patients, and 43% of that subgroup had a high-risk scan. Thirty-eight percent of patients had other ECG abnormalities, and 28% of them had a high-risk scan. Age greater than 65 was associated with an increased likelihood of a high-risk SPECT result. And 28% of patients with PAD had a high-risk scan.

On the other hand, the likelihood of a high-risk scan in the 69% of subjects without PAD was 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Jan 4;45[1]:43-9).

The 2017 ADA guidelines acknowledge this and similar evidence by providing as a relatively weak Level E recommendation: “Consider screening for CAD in the presence of any of the following: atypical cardiac symptoms (e.g., unexplained dyspnea, chest discomfort); signs of symptoms of associated vascular disease including carotid bruits, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, or PAD; or electrogram abnormalities (e.g., Q waves).”

Dr. di Carli would add to that list age older than 65, diabetes duration of greater than 10 years, poor diabetes control, and a high burden of standard cardiovascular risk factors. And he proposed the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score as a sensible gateway to selective use of further screening tests, citing as support a report from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).

The MESA investigators assessed CAC in 6,603 persons aged 45-84 free of known CAD at baseline, including 881 with diabetes. Participants were subsequently followed prospectively for an average of 6.4 years. Compared with diabetes patients who had a baseline CAC score of 0, those with a score of 1-99 were at a risk factor– and ethnicity-adjusted 2.9-fold increased risk for developing coronary heart disease during the follow-up period. The CHD risk climbed stepwise with an increasing CAC score such that subjects with a score of 400 or higher were at 9.5-fold increased risk (Diabetes Care. 2011 Oct;34[10]L2285-90).

Using CAC measurement in this way as a screening tool in asymptomatic diabetes patients with clinical factors placing them at higher risk of significant CAD is consistent with appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease. The criteria were provided in a 2014 joint report by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The report rates CAC testing as “May Be Appropriate” for asymptomatic patients of intermediate or high global risk. As such, CAC “can be an option for further evaluation of potential SIHD [stable ischemic heart disease] in an individual patient when deemed reasonable by the patient’s physician,” according to the appropriate use criteria guidance, which was created with the express purpose of developing standards to avoid overuse of costly cardiovascular testing (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 4;63[4]:380-406).

Dr. di Carli reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The use of coronary artery calcium screening in the subset of asymptomatic diabetes patients at higher clinical risk of CAD appears to offer a practical strategy for identifying a subgroup in whom costlier stress cardiac imaging may be justified, Marcelo F. di Carli, MD, said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The ultimate goal is to reliably identify those patients who have asymptomatic diabetes with significant CAD warranting revascularization or maximal medical therapy for primary cardiovascular prevention.

“Coronary artery calcium is a simple test that’s accessible and inexpensive and can give us a quick read on the extent of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries,” said Dr. di Carli, professor of radiology and medicine at Harvard University in Boston. “There’s good data that in diabetic patients there’s a gradation of risk across the spectrum of calcium scores. Risk increases exponentially from a coronary artery calcium score of 0 to more than 400. The calcium score can also provide a snapshot of which patients are more likely to have flow-limiting coronary disease.”

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the biggest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of diabetes, and diabetes experts are eager to avoid jacking up those costs further by routinely ordering stress nuclear imaging, stress echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and other expensive noninvasive imaging methods unless they can be shown to lead to improved outcomes. There is general agreement on the value of noninvasive imaging in diabetic patients with CAD symptoms. However, the routine use of such testing in asymptomatic diabetic patients has been controversial.

Indeed, according to the 2017 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes: “In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for coronary artery disease is not recommended as it does not improve outcomes as long as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors are treated (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl. 1]:S75-87). That’s a Level A recommendation.

But Dr. di Carli is among many cardiologists who believe this statement paints with too broad a brush. He considers it an overgeneralization that’s based on the negative results of two randomized trials of routine screening in asymptomatic diabetics: DIAD, which utilized stress single-photon emission CT (SPECT) imaging (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55), and FACTOR-64, which relied upon coronary CT angiography (JAMA. 2014 Dec 3;312[21]: 2234-43). Both studies found relatively low yields of severe CAD and showed no survival benefit for screening. And of course, these are also costly and inconvenient tests.

The problem in generalizing from DIAD and FACTOR-64 to the overall population of asymptomatic diabetic patients is that both studies were conducted in asymptomatic patients at the lower end of the cardiovascular risk spectrum. They were young, with an average age of 60 years. They had a history of diabetes of less than 10 years, and their diabetes was reasonably well controlled. They had normal ECGs and preserved renal function. Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was present in only 9% of the DIAD population and no one in FACTOR-64. So this would not be expected to be a high-risk/high-yield population, according to Dr. di Carli, executive director of the cardiovascular imaging program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

An earlier study from the Mayo Clinic identified the clinical factors that can potentially be used to identify a higher-risk cohort of asymptomatic diabetic patients in whom high-tech noninvasive testing for significant CAD may be justified, he continued. This was a nonrandomized study of 1,427 asymptomatic diabetic patients without known CAD who underwent SPECT imaging. Compared with the study populations in DIAD and FACTOR-64, the Mayo Clinic patients had a longer duration of diabetes and substantially higher rates of poor diabetes control, renal dysfunction, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. One-third of them had PAD.

Fifty-eight percent of the 1,427 patients in the Mayo cohort proved to have an abnormal SPECT imaging scan, and 18% had a high-risk scan. In a multivariate analysis, the investigators identified several factors independently associated with a high-risk scan. Q waves were present on the ECGs of 9% of the asymptomatic diabetes patients, and 43% of that subgroup had a high-risk scan. Thirty-eight percent of patients had other ECG abnormalities, and 28% of them had a high-risk scan. Age greater than 65 was associated with an increased likelihood of a high-risk SPECT result. And 28% of patients with PAD had a high-risk scan.

On the other hand, the likelihood of a high-risk scan in the 69% of subjects without PAD was 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Jan 4;45[1]:43-9).

The 2017 ADA guidelines acknowledge this and similar evidence by providing as a relatively weak Level E recommendation: “Consider screening for CAD in the presence of any of the following: atypical cardiac symptoms (e.g., unexplained dyspnea, chest discomfort); signs of symptoms of associated vascular disease including carotid bruits, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, or PAD; or electrogram abnormalities (e.g., Q waves).”

Dr. di Carli would add to that list age older than 65, diabetes duration of greater than 10 years, poor diabetes control, and a high burden of standard cardiovascular risk factors. And he proposed the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score as a sensible gateway to selective use of further screening tests, citing as support a report from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).

The MESA investigators assessed CAC in 6,603 persons aged 45-84 free of known CAD at baseline, including 881 with diabetes. Participants were subsequently followed prospectively for an average of 6.4 years. Compared with diabetes patients who had a baseline CAC score of 0, those with a score of 1-99 were at a risk factor– and ethnicity-adjusted 2.9-fold increased risk for developing coronary heart disease during the follow-up period. The CHD risk climbed stepwise with an increasing CAC score such that subjects with a score of 400 or higher were at 9.5-fold increased risk (Diabetes Care. 2011 Oct;34[10]L2285-90).

Using CAC measurement in this way as a screening tool in asymptomatic diabetes patients with clinical factors placing them at higher risk of significant CAD is consistent with appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease. The criteria were provided in a 2014 joint report by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The report rates CAC testing as “May Be Appropriate” for asymptomatic patients of intermediate or high global risk. As such, CAC “can be an option for further evaluation of potential SIHD [stable ischemic heart disease] in an individual patient when deemed reasonable by the patient’s physician,” according to the appropriate use criteria guidance, which was created with the express purpose of developing standards to avoid overuse of costly cardiovascular testing (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 4;63[4]:380-406).

Dr. di Carli reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The use of coronary artery calcium screening in the subset of asymptomatic diabetes patients at higher clinical risk of CAD appears to offer a practical strategy for identifying a subgroup in whom costlier stress cardiac imaging may be justified, Marcelo F. di Carli, MD, said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The ultimate goal is to reliably identify those patients who have asymptomatic diabetes with significant CAD warranting revascularization or maximal medical therapy for primary cardiovascular prevention.

“Coronary artery calcium is a simple test that’s accessible and inexpensive and can give us a quick read on the extent of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries,” said Dr. di Carli, professor of radiology and medicine at Harvard University in Boston. “There’s good data that in diabetic patients there’s a gradation of risk across the spectrum of calcium scores. Risk increases exponentially from a coronary artery calcium score of 0 to more than 400. The calcium score can also provide a snapshot of which patients are more likely to have flow-limiting coronary disease.”

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the biggest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of diabetes, and diabetes experts are eager to avoid jacking up those costs further by routinely ordering stress nuclear imaging, stress echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and other expensive noninvasive imaging methods unless they can be shown to lead to improved outcomes. There is general agreement on the value of noninvasive imaging in diabetic patients with CAD symptoms. However, the routine use of such testing in asymptomatic diabetic patients has been controversial.

Indeed, according to the 2017 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes: “In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for coronary artery disease is not recommended as it does not improve outcomes as long as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors are treated (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl. 1]:S75-87). That’s a Level A recommendation.

But Dr. di Carli is among many cardiologists who believe this statement paints with too broad a brush. He considers it an overgeneralization that’s based on the negative results of two randomized trials of routine screening in asymptomatic diabetics: DIAD, which utilized stress single-photon emission CT (SPECT) imaging (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55), and FACTOR-64, which relied upon coronary CT angiography (JAMA. 2014 Dec 3;312[21]: 2234-43). Both studies found relatively low yields of severe CAD and showed no survival benefit for screening. And of course, these are also costly and inconvenient tests.

The problem in generalizing from DIAD and FACTOR-64 to the overall population of asymptomatic diabetic patients is that both studies were conducted in asymptomatic patients at the lower end of the cardiovascular risk spectrum. They were young, with an average age of 60 years. They had a history of diabetes of less than 10 years, and their diabetes was reasonably well controlled. They had normal ECGs and preserved renal function. Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was present in only 9% of the DIAD population and no one in FACTOR-64. So this would not be expected to be a high-risk/high-yield population, according to Dr. di Carli, executive director of the cardiovascular imaging program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

An earlier study from the Mayo Clinic identified the clinical factors that can potentially be used to identify a higher-risk cohort of asymptomatic diabetic patients in whom high-tech noninvasive testing for significant CAD may be justified, he continued. This was a nonrandomized study of 1,427 asymptomatic diabetic patients without known CAD who underwent SPECT imaging. Compared with the study populations in DIAD and FACTOR-64, the Mayo Clinic patients had a longer duration of diabetes and substantially higher rates of poor diabetes control, renal dysfunction, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. One-third of them had PAD.

Fifty-eight percent of the 1,427 patients in the Mayo cohort proved to have an abnormal SPECT imaging scan, and 18% had a high-risk scan. In a multivariate analysis, the investigators identified several factors independently associated with a high-risk scan. Q waves were present on the ECGs of 9% of the asymptomatic diabetes patients, and 43% of that subgroup had a high-risk scan. Thirty-eight percent of patients had other ECG abnormalities, and 28% of them had a high-risk scan. Age greater than 65 was associated with an increased likelihood of a high-risk SPECT result. And 28% of patients with PAD had a high-risk scan.

On the other hand, the likelihood of a high-risk scan in the 69% of subjects without PAD was 14% (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Jan 4;45[1]:43-9).

The 2017 ADA guidelines acknowledge this and similar evidence by providing as a relatively weak Level E recommendation: “Consider screening for CAD in the presence of any of the following: atypical cardiac symptoms (e.g., unexplained dyspnea, chest discomfort); signs of symptoms of associated vascular disease including carotid bruits, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, or PAD; or electrogram abnormalities (e.g., Q waves).”

Dr. di Carli would add to that list age older than 65, diabetes duration of greater than 10 years, poor diabetes control, and a high burden of standard cardiovascular risk factors. And he proposed the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score as a sensible gateway to selective use of further screening tests, citing as support a report from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).

The MESA investigators assessed CAC in 6,603 persons aged 45-84 free of known CAD at baseline, including 881 with diabetes. Participants were subsequently followed prospectively for an average of 6.4 years. Compared with diabetes patients who had a baseline CAC score of 0, those with a score of 1-99 were at a risk factor– and ethnicity-adjusted 2.9-fold increased risk for developing coronary heart disease during the follow-up period. The CHD risk climbed stepwise with an increasing CAC score such that subjects with a score of 400 or higher were at 9.5-fold increased risk (Diabetes Care. 2011 Oct;34[10]L2285-90).

Using CAC measurement in this way as a screening tool in asymptomatic diabetes patients with clinical factors placing them at higher risk of significant CAD is consistent with appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease. The criteria were provided in a 2014 joint report by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The report rates CAC testing as “May Be Appropriate” for asymptomatic patients of intermediate or high global risk. As such, CAC “can be an option for further evaluation of potential SIHD [stable ischemic heart disease] in an individual patient when deemed reasonable by the patient’s physician,” according to the appropriate use criteria guidance, which was created with the express purpose of developing standards to avoid overuse of costly cardiovascular testing (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 4;63[4]:380-406).

Dr. di Carli reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Diagnosis of Severe Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding with CTA

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

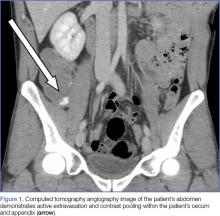

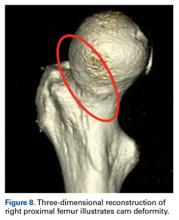

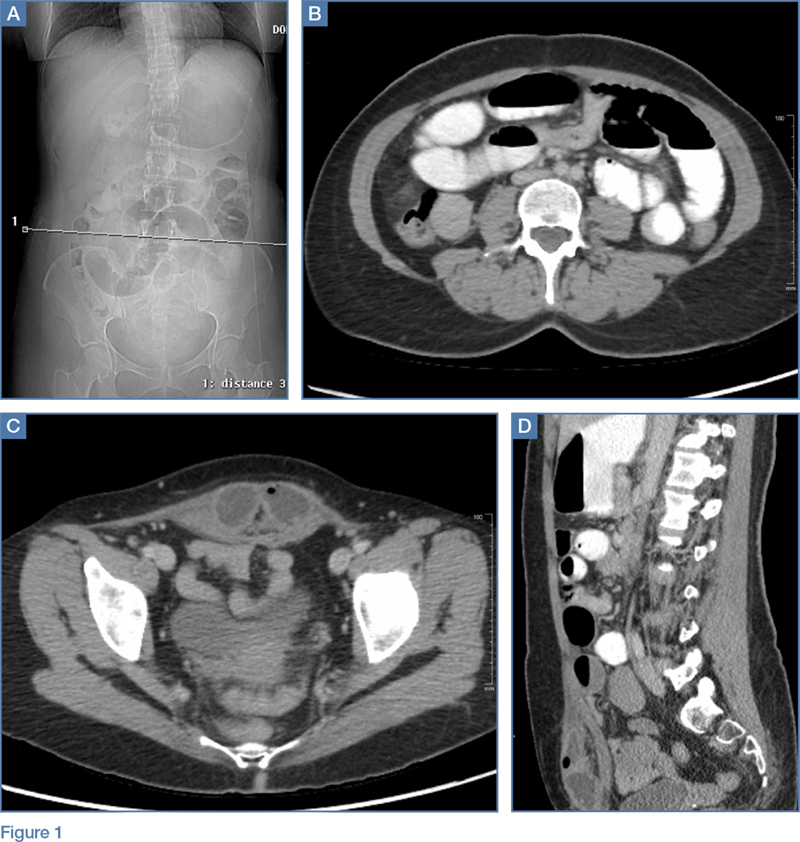

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

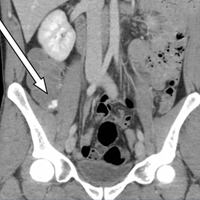

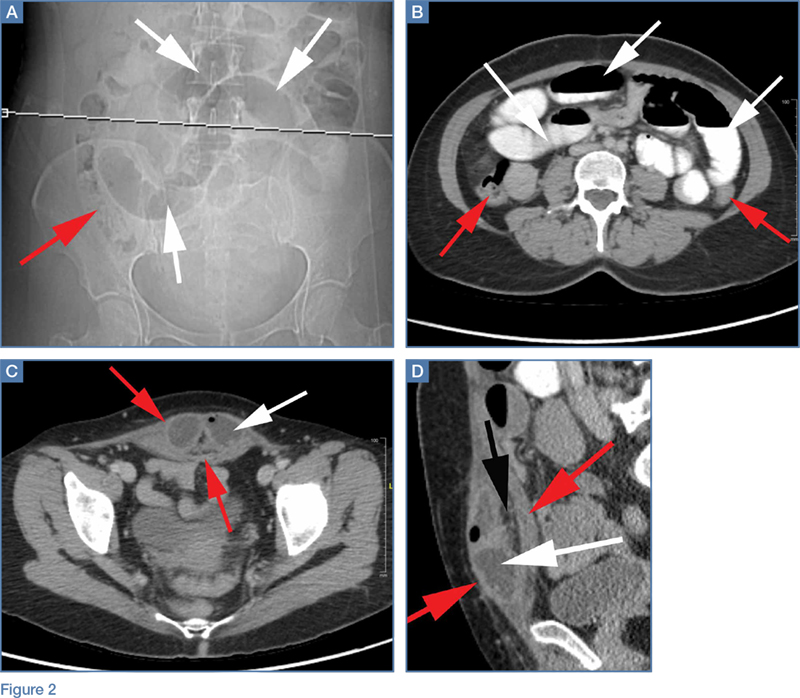

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

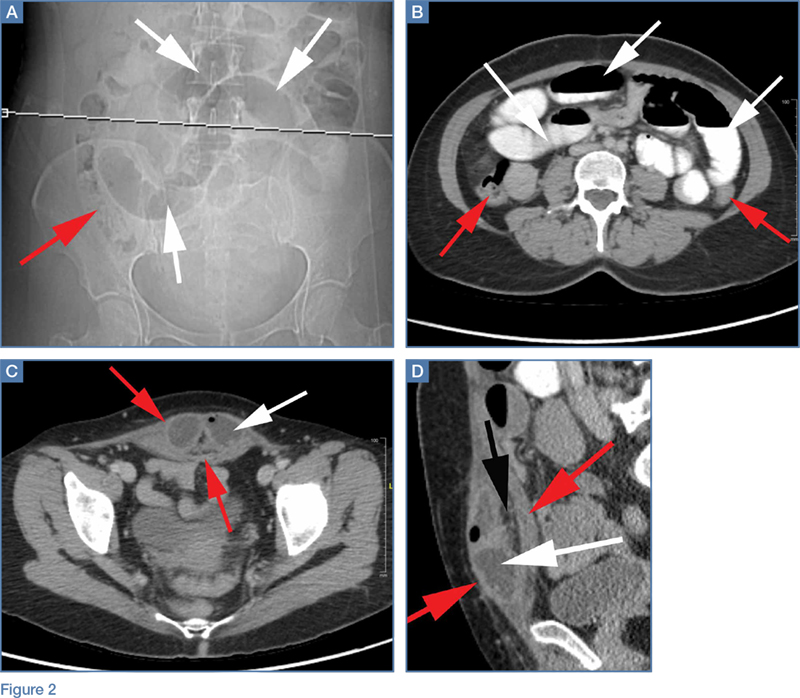

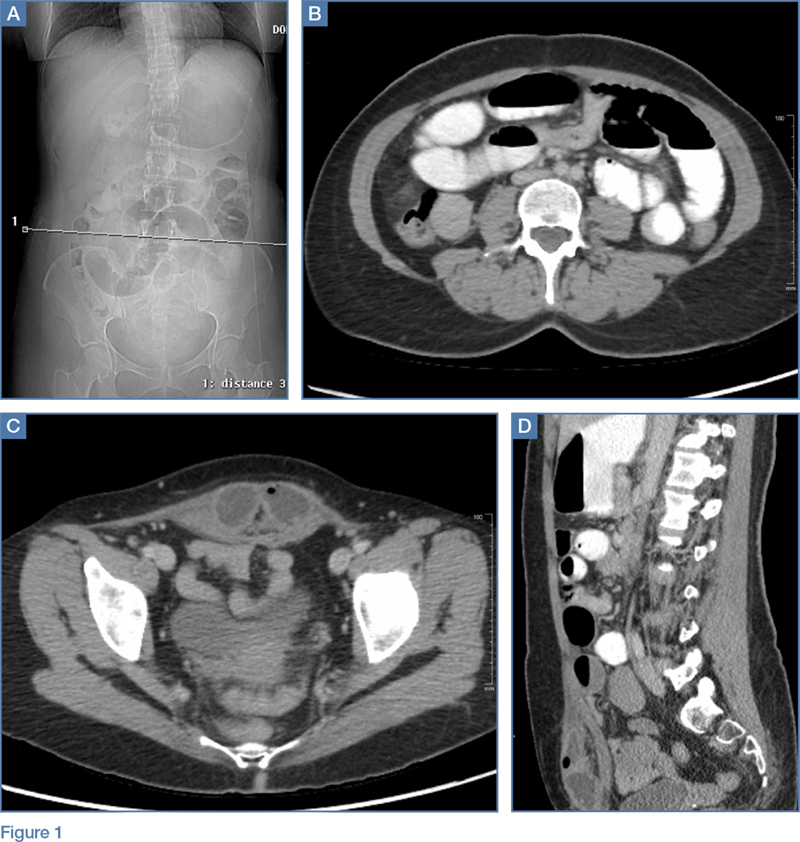

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

Emergency Imaging: Abdominal Pain 6 Months After Cesarean Delivery

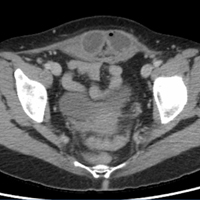

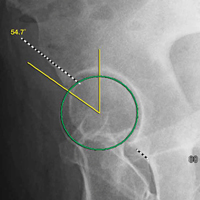

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

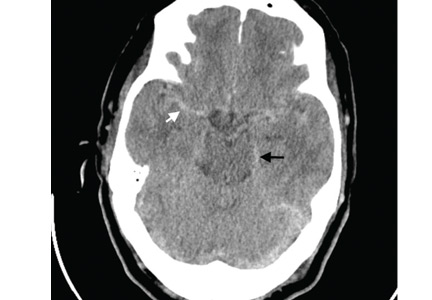

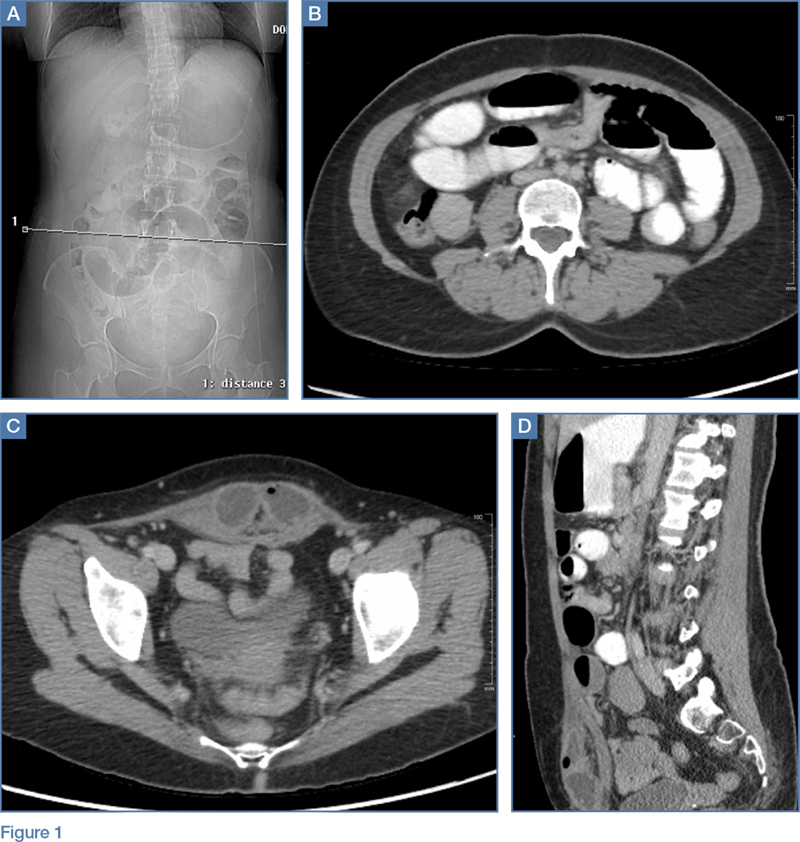

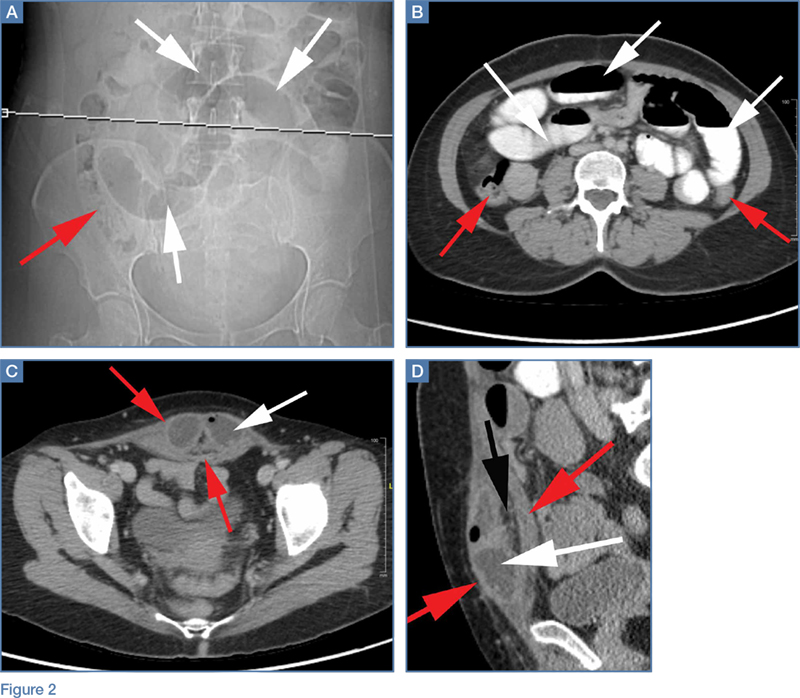

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

1. Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1045-1051, v-vi. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4.

2. Lenobel S, Lenobel R, Yu J. Posterior rectus sheath hernia causing intermittent small bowel obstruction. J Radiol Case Rep J. 2014;8(9):25-29. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i9.2081.

3. Losanoff JE, Basson MD, Gruber SA. Spontaneous hernia through the posterior rectus abdominis sheath: case report and review of the published literature 1937-2008. Hernia. 2009;13(5):555-558. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0481-6.

4. Bentzon N, Adamsen S. Hernia of the posterior rectus sheath: a new entity? Eur J Surg. 1995;161(3):215-216.

5. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at mutli-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25(6):1501-1520. doi:10.1148/rg.256055018.

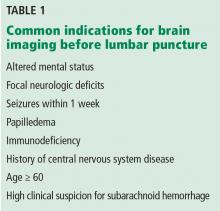

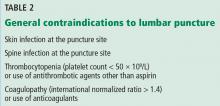

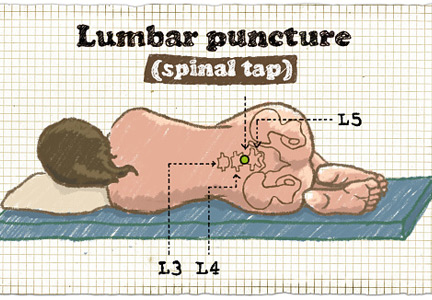

When should brain imaging precede lumbar puncture in cases of suspected bacterial meningitis?

Brain imaging should precede lumbar puncture in patients with focal neurologic deficits or immunodeficiency, or with altered mental status or seizures during the previous week. However, lumbar puncture can be safely done in most patients without first obtaining brain imaging. Empiric antibiotic and corticosteroid therapy must not be delayed; they should be started immediately after the lumber puncture is done, without waiting for the results. If the lumbar puncture is going to be delayed, these treatments should be started immediately after obtaining blood samples for culture.

A MEDICAL EMERGENCY