User login

Understanding the bell-ringing of concussion

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

Breast calcifications mimicking pulmonary nodules

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

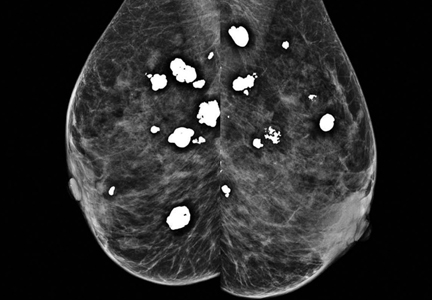

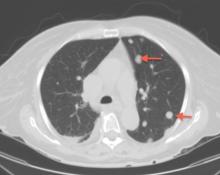

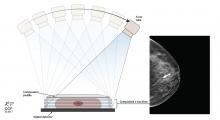

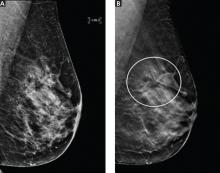

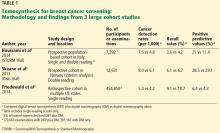

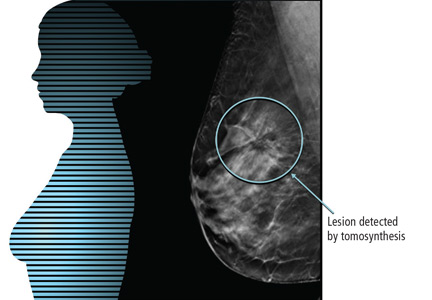

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

Necrotizing pancreatitis: Diagnose, treat, consult

Acute pancreatitis accounted for more than 300,000 admissions and $2.6 billion in associated healthcare costs in the United States in 2012.1 First-line management is early aggressive fluid resuscitation and analgesics for pain control. Guidelines recommend estimating the clinical severity of each attack using a validated scoring system such as the Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis.2 Clinically severe pancreatitis is associated with necrosis.

Acute pancreatitis results from inappropriate activation of zymogens and subsequent autodigestion of the pancreas by its own enzymes. Though necrotizing pancreatitis is thought to be an ischemic complication, its pathogenesis is not completely understood. Necrosis increases the morbidity and mortality risk of acute pancreatitis because of its association with organ failure and infectious complications. As such, patients with necrotizing pancreatitis may need admission to the intensive care unit, nutritional support, antibiotics, and radiologic, endoscopic, or surgical interventions.

Here, we review current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of necrotizing pancreatitis.

PROPER TERMINOLOGY HELPS COLLABORATION

Managing necrotizing pancreatitis requires the combined efforts of internists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. This collaboration is aided by proper terminology.

A classification system was devised in Atlanta, GA, in 1992 to facilitate communication and interdisciplinary collaboration.3 Severe pancreatitis was differentiated from mild by the presence of organ failure or the complications of pseudocyst, necrosis, or abscess.

The original Atlanta classification had several limitations. First, the terminology for fluid collections was ambiguous and frequently misused. Second, the assessment of clinical severity required either the Ranson score or the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, both of which are complex and have other limitations. Finally, advances in imaging and treatment have rendered the original Atlanta nomenclature obsolete.

In 2012, the Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group issued a revised Atlanta classification that modernized the terminology pertaining to natural history, severity, imaging features, and complications. It divides the natural course of acute pancreatitis into early and late phases.4

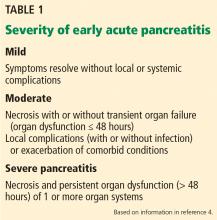

Early vs late phase

In the early phase, findings on computed tomography (CT) neither correlate with clinical severity nor alter clinical management.6 Thus, early imaging is not indicated unless there is diagnostic uncertainty, lack of response to appropriate treatment, or sudden deterioration.

Moderate pancreatitis describes patients with pancreatic necrosis with or without transient organ failure (organ dysfunction for ≤ 48 hours).

Severe pancreatitis is defined by pancreatic necrosis and persistent organ dysfunction.4 It may be accompanied by pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections; bacteremia and sepsis can occur in association with infection of necrotic collections.

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis vs necrotizing pancreatitis

The revised Atlanta classification maintains the original classification of acute pancreatitis into 2 main categories: interstitial edematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis.

Necrotizing pancreatitis is further divided into 3 subtypes based on extent and location of necrosis:

- Parenchymal necrosis alone (5% of cases)

- Necrosis of peripancreatic fat alone (20%)

- Necrosis of both parenchyma and peripancreatic fat (75%).

Peripancreatic involvement is commonly found in the mesentery, peripancreatic and distant retroperitoneum, and lesser sac.

Of the three subtypes, peripancreatic necrosis has the best prognosis. However, all of the subtypes of necrotizing pancreatitis are associated with poorer outcomes than interstitial edematous pancreatitis.

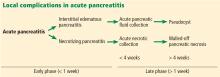

Fluid collections

Acute pancreatic fluid collections contain exclusively nonsolid components without an inflammatory wall and are typically found in the peripancreatic fat. These collections often resolve without intervention as the patient recovers. If they persist beyond 4 weeks and develop a nonepithelialized, fibrous wall, they become pseudocysts. Intervention is generally not recommended for pseudocysts unless they are symptomatic.

ROLE OF IMAGING

Radiographic imaging is not usually necessary to diagnose acute pancreatitis. However, it can be a valuable tool to clarify an ambiguous presentation, determine severity, and identify complications.

The timing and appropriate type of imaging are integral to obtaining useful data. Any imaging obtained in acute pancreatitis to evaluate necrosis should be performed at least 3 to 5 days from the initial symptom onset; if imaging is obtained before 72 hours, necrosis cannot be confidently excluded.8

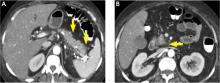

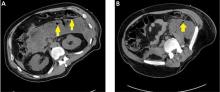

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

CT is the imaging test of choice when evaluating acute pancreatitis. In addition, almost all percutaneous interventions are performed with CT guidance. The Balthazar score is the most well-known CT severity index. It is calculated based on the degree of inflammation, acute fluid collections, and parenchymal necrosis.9 However, a modified severity index incorporates extrapancreatic complications such as ascites and vascular compromise and was found to more strongly correlate with outcomes than the standard Balthazar score.10

Contrast-enhanced CT is performed in 2 phases:

The pancreatic parenchymal phase

The pancreatic parenchymal or late arterial phase is obtained approximately 40 to 45 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect necrosis in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and to assess the peripancreatic arteries for pseudoaneurysms in the late phase of acute pancreatitis.11

Pancreatic necrosis appears as an area of decreased parenchymal enhancement, either well-defined or heterogeneous. The normal pancreatic parenchyma has a postcontrast enhancement pattern similar to that of the spleen. Parenchyma that does not enhance to the same degree is considered necrotic. The severity of necrosis is graded based on the percentage of the pancreas involved (< 30%, 30%–50%, or > 50%), and a higher percentage correlates with a worse outcome.12,13

Peripancreatic necrosis is harder to detect, as there is no method to assess fat enhancement as there is with pancreatic parenchymal enhancement. In general, radiologists assume that heterogeneous peripancreatic changes, including areas of fat, fluid, and soft tissue attenuation, are consistent with peripancreatic necrosis. After 7 to 10 days, if these changes become more homogeneous and confluent with a more mass-like process, peripancreatic necrosis can be more confidently identified.12,13

The portal venous phase

The later, portal venous phase of the scan is obtained approximately 70 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect and characterize fluid collections and venous complications of the disease.

Drawbacks of CT

A drawback of CT is the need for iodinated intravenous contrast media, which in severely ill patients may precipitate or worsen pre-existing acute kidney injury.

Further, several studies have shown that findings on CT rarely alter the management of patients in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and in fact may be an overuse of medical resources.14 Unless there are confounding clinical signs or symptoms, CT should be delayed for at least 72 hours.9,10,14,15

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not a first-line imaging test in this disease because it is not as available as CT and takes longer to perform—20 to 30 minutes. The patient must be evaluated for candidacy, as it is difficult for acutely ill patients to tolerate an examination that takes this long and requires them to hold their breath multiple times.

MRI is an appropriate alternative in patients who are pregnant or who have severe iodinated-contrast allergy. While contrast is necessary to detect pancreatic necrosis with CT, MRI can detect necrosis without the need for contrast in patients with acute kidney injury or severe chronic kidney disease. Also, MRI may be better in complicated cases requiring repeated imaging because it does not expose the patient to radiation.

On MRI, pancreatic necrosis appears as a heterogeneous area, owing to its liquid and solid components. Liquid components appear hyperintense, and solid components hypointense, on T2 fluid-weighted imaging. This ability to differentiate the components of a walled-off pancreatic necrosis can be useful in determining whether a collection requires drainage or debridement. MRI is also more sensitive for hemorrhagic complications, best seen on T1 fat-weighted images.12,16

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is an excellent method for ductal evaluation through heavily T2-weighted imaging. It is more sensitive than CT for detecting common bile duct stones and can also detect pancreatic duct strictures or extravasation into fluid collections.16

SUPPORTIVE MANAGEMENT OF EARLY NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

In the early phase of necrotizing pancreatitis, management is supportive with the primary aim of preventing intravascular volume depletion. Aggressive fluid resuscitation in the first 48 to 72 hours, pain control, and bowel rest are the mainstays of supportive therapy. Intensive care may be necessary if organ failure and hemodynamic instability accompany necrotizing pancreatitis.

Prophylactic antibiotic and antifungal therapy to prevent infected necrosis has been controversial. Recent studies of its utility have not yielded supportive results, and the American College of Gastroenterology and the Infectious Diseases Society of America no longer recommend it.9,17 These medications should not be given unless concomitant cholangitis or extrapancreatic infection is clinically suspected.

Early enteral nutrition is recommended in patients in whom pancreatitis is predicted to be severe and in those not expected to resume oral intake within 5 to 7 days. Enteral nutrition most commonly involves bedside or endoscopic placement of a nasojejunal feeding tube and collaboration with a nutritionist to determine protein-caloric requirements.

Compared with enteral nutrition, total parenteral nutrition is associated with higher rates of infection, multiorgan dysfunction and failure, and death.18

MANAGING COMPLICATIONS OF PANCREATIC NECROSIS

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a defining complication of acute pancreatitis, and its presence alone indicates greater severity. However, superimposed complications may further worsen outcomes.

Infected pancreatic necrosis

Infection occurs in approximately 20% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and confers a mortality rate of 20% to 50%.19 Infected pancreatic necrosis occurs when gut organisms translocate into the nearby necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue. The most commonly identified organisms include Escherichia coli and Enterococcus species.20

This complication usually manifests 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset; earlier onset is uncommon to rare. It should be considered when the systemic inflammatory response syndrome persists or recurs after 10 days to 2 weeks. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is also common in sterile necrotizing pancreatitis and sometimes in interstitial pancreatitis, particularly during the first week. However, its sudden appearance or resurgence, high spiking fevers, or worsening organ failure in the later phase (2–4 weeks) of pancreatitis should heighten suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis.

Imaging may also help diagnose infection, and the presence of gas within a collection or region of necrosis is highly specific. However, the presence of gas is not completely sensitive for infection, as it is seen in only 12% to 22% of infected cases.

Before minimally invasive techniques became available, the diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis was confirmed by percutaneous CT-guided aspiration of the necrotic mass or collection for Gram stain and culture.

Antibiotic therapy is indicated in confirmed or suspected cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Antibiotics with gram-negative coverage and appropriate penetration such as carbapenems, metronidazole, fluoroquinolones, and selected cephalosporins are most commonly used. Meropenem is the antibiotic of choice at our institution.

CT-guided fine-needle aspiration is often done if suspected infected pancreatic necrosis fails to respond to empiric antibiotic therapy.

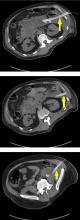

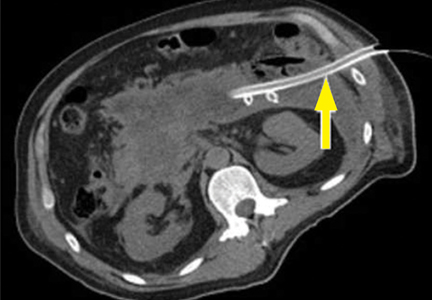

Debridement or drainage. Generally, the diagnosis or suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis (suggestive signs are high fever, elevated white blood cell count, and sepsis) warrants an intervention to debride or drain infected pancreatic tissue and control sepsis.21

While source control is integral to the successful treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis, antibiotic therapy may provide a bridge to intervention for critically ill patients by suppressing bacteremia and subsequent sepsis. A 2013 meta-analysis found that 324 of 409 patients with suspected infected pancreatic necrosis were successfully stabilized with antibiotic treatment.21,22 The trend toward conservative management and promising outcomes with antibiotic therapy alone or with minimally invasive techniques has lessened the need for diagnostic CT-guided fine-needle aspiration.

Hemorrhage

Spontaneous hemorrhage into pancreatic necrosis is a rare but life-threatening complication. Because CT is almost always performed with contrast enhancement, this complication is rarely identified with imaging. The diagnosis is made by noting a drop in hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Hemorrhage into the retroperitoneum or the peritoneal cavity, or both, can occur when an inflammatory process erodes into a nearby artery. Luminal gastrointestinal bleeding can occur from gastric varices arising from splenic vein thrombosis and resulting left-sided portal hypertension, or from pseudoaneurysms. These can also bleed into the pancreatic duct (hemosuccus pancreaticus). Pseudoaneurysm is a later complication that occurs when an arterial wall (most commonly the splenic or gastroduodenal artery) is weakened by pancreatic enzymes.23

Prompt recognition of hemorrhagic events and consultation with an interventional radiologist or surgeon are required to prevent death.

Inflammation and abdominal compartment syndrome

Inflammation from necrotizing pancreatitis can cause further complications by blocking nearby structures. Reported complications include jaundice from biliary compression, hydronephrosis from ureteral compression, bowel obstruction, and gastric outlet obstruction.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is an increasingly recognized complication of acute pancreatitis. Abdominal pressure can rise due to a number of factors, including fluid collections, ascites, ileus, and overly aggressive fluid resuscitation.24 Elevated abdominal pressure is associated with complications such as decreased respiratory compliance, increased peak airway pressure, decreased cardiac preload, hypotension, mesenteric and intestinal ischemia, feeding intolerance, and lower-extremity ischemia and thrombosis.

Patients with necrotizing pancreatitis who have abdominal compartment syndrome have a mortality rate 5 times higher than patients without abdominal compartment syndrome.25

Abdominal pressures should be monitored using a bladder pressure sensor in critically ill or ventilated patients with acute pancreatitis. If the abdominal pressure rises above 20 mm Hg, medical and surgical interventions should be offered in a stepwise fashion to decrease it. Interventions include decompression by nasogastric and rectal tube, sedation or paralysis to relax abdominal wall tension, minimization of intravenous fluids, percutaneous drainage of ascites, and (rarely) surgical midline or subcostal laparotomy.

ROLE OF INTERVENTION

The treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis has changed rapidly, thanks to a growing experience with minimally invasive techniques.

Indications for intervention

Infected pancreatic necrosis is the primary indication for surgical, percutaneous, or endoscopic intervention.

In sterile necrosis, the threshold for intervention is less clear, and intervention is often reserved for patients who fail to clinically improve or who have intractable abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or fistulating disease.26

In asymptomatic cases, intervention is almost never indicated regardless of the location or size of the necrotic area.

In walled-off pancreatic necrosis, less-invasive and less-morbid interventions such as endoscopic or percutaneous drainage or video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement can be done.

Timing of intervention

In the past, delaying intervention was thought to increase the risk of death. However, multiple studies have found that outcomes are often worse if intervention is done early, likely due to the lack of a fully formed fibrous wall or demarcation of the necrotic area.27

If the patient remains clinically stable, it is best to delay intervention until at least 4 weeks after the index event to achieve optimal outcomes. Delay can often be achieved by antibiotic treatment to suppress bacteremia and endoscopic or percutaneous drainage of infected collections to control sepsis.

Open surgery

The gold-standard intervention for infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis is open necrosectomy. This involves exploratory laparotomy with blunt debridement of all visible necrotic pancreatic tissue.

Methods to facilitate later evacuation of residual infected fluid and debris vary widely. Multiple large-caliber drains can be placed to facilitate irrigation and drainage before closure of the abdominal fascia. As infected pancreatic necrosis carries the risk of contaminating the peritoneal cavity, the skin is often left open to heal by secondary intention. An interventional radiologist is frequently enlisted to place, exchange, or downsize drainage catheters.

Infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis often requires more than one operation to achieve satisfactory debridement.

The goals of open necrosectomy are to remove nonviable tissue and infection, preserve viable pancreatic tissue, eliminate fistulous connections, and minimize damage to local organs and vasculature.

Minimally invasive techniques

Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement has been described as a hybrid between endoscopic and open retroperitoneal debridement.28 This technique requires first placing a percutaneous catheter into the necrotic area through the left flank to create a retroperitoneal tract. A 5-cm incision is made and the necrotic space is entered using the drain for guidance. Necrotic tissue is carefully debrided under direct vision using a combination of forceps, irrigation, and suction. A laparoscopic port can also be introduced into the incision when the procedure can no longer be continued under direct vision.29,30

Although not all patients are candidates for minimal-access surgery, it remains an evolving surgical option.

Endoscopic transmural debridement is another option for infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Depending on the location of the necrotic area, an echoendoscope is passed to either the stomach or duodenum. Guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, a needle is passed into the collection, allowing subsequent fistula creation and stenting for internal drainage or debridement. In the past, this process required several steps, multiple devices, fluoroscopic guidance, and considerable time. But newer endoscopic lumen-apposing metal stents have been developed that can be placed in a single step without fluoroscopy. A slimmer endoscope can then be introduced into the necrotic cavity via the stent, and the necrotic debris can be debrided with endoscopic baskets, snares, forceps, and irrigation.9,31

Similar to surgical necrosectomy, satisfactory debridement is not often obtained with a single procedure; 2 to 5 endoscopic procedures may be needed to achieve resolution. However, the luminal approach in endoscopic necrosectomy avoids the significant morbidity of major abdominal surgery and the potential for pancreaticocutaneous fistulae that may occur with drains.

In a randomized trial comparing endoscopic necrosectomy vs surgical necrosectomy (video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement and exploratory laparotomy),32 endoscopic necrosectomy showed less inflammatory response than surgical necrosectomy and had a lower risk of new-onset organ failure, bleeding, fistula formation, and death.32

Selecting the best intervention for the individual patient

Given the multiple available techniques, selecting the best intervention for individual patients can be challenging. A team approach with input from a gastroenterologist, surgeon, and interventional radiologist is best when determining which technique would best suit each patient.

Surgical necrosectomy is still the treatment of choice for unstable patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or multiple, inaccessible collections, but current evidence suggests a different approach in stable infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

The Dutch Pancreatitis Group28 randomized 88 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis to open necrosectomy or a minimally invasive “step-up” approach consisting of up to 2 percutaneous drainage or endoscopic debridement procedures before escalation to video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement. The step-up approach resulted in lower rates of morbidity and death than surgical necrosectomy as first-line treatment. Furthermore, some patients in the step-up group avoided the need for surgery entirely.30

SUMMING UP

Necrosis significantly increases rates of morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Hospitalists, general internists, and general surgeons are all on the front lines in identifying severe cases and consulting the appropriate specialists for optimal multidisciplinary care. Selective and appropriate timing of radiologic imaging is key, and a vital tool in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis.

While the primary indication for intervention is infected pancreatic necrosis, additional indications are symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis secondary to intractable abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, and failure to thrive. As a result of improving technology and inpatient care, these patients may present with intractable symptoms in the outpatient setting rather than the inpatient setting. The onus is on the primary care physician to maintain a high level of suspicion and refer these patients to subspecialists as appropriate.

Open surgical necrosectomy remains an important approach for care of infected pancreatic necrosis or patients with intractable symptoms. A step-up approach starting with a minimally invasive procedure and escalating if the initial intervention is unsuccessful is gradually becoming the standard of care.

- Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:1731–1741e3.

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:1400–1416.

- Bradley EL 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, GA, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg 1993; 128:586–590.

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013; 62:102–111.

- Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med 1995; 23:1638–1652.

- Kadiyala V, Suleiman SL, McNabb-Baltar J, Wu BU, Banks PA, Singh VK. The Atlanta classification, revised Atlanta classification, and determinant-based classification of acute pancreatitis: which is best at stratifying outcomes? Pancreas 2016; 45:510–515.

- Singh VK, Bollen TL, Wu BU, et al. An assessment of the severity of interstitial pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:1098–1103.

- Kotwal V, Talukdar R, Levy M, Vege SS. Role of endoscopic ultrasound during hospitalization for acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16:4888–4891.

- Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology 2002; 223:603–613.

- Mortele KJ, Wiesner W, Intriere L, et al. A modified CT severity index for evaluating acute pancreatitis: improved correlation with patient outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183:1261–1265.

- Verde F, Fishman EK, Johnson PT. Arterial pseudoaneurysms complicating pancreatitis: literature review. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2015; 39:7–12.

- Shyu JY, Sainani NI, Sahni VA, et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis, imaging, and intervention. Radiographics 2014; 34:1218–1239.

- Thoeni RF. The revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis: its importance for the radiologist and its effect on treatment. Radiology 2012; 262:751–764.

- Morgan DE, Ragheb CM, Lockhart ME, Cary B, Fineberg NS, Berland LL. Acute pancreatitis: computed tomography utilization and radiation exposure are related to severity but not patient age. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8:303–308.

- Vitellas KM, Paulson EK, Enns RA, Keogan MT, Pappas TN. Pancreatitis complicated by gland necrosis: evolution of findings on contrast-enhanced CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999; 23:898–905.

- Stimac D, Miletic D, Radic M, et al. The role of nonenhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the early assessment of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:997–1004.

- Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2010; 11:79–109.

- Petrov MS, Kukosh MV, Emelyanov NV. A randomized controlled trial of enteral versus parenteral feeding in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis shows a significant reduction in mortality and in infected pancreatic complications with total enteral nutrition. Dig Surg 2006; 23:336–345.

- Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, Phillips AR, Windsor JA. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:813–820.

- Villatoro E, Bassi C, Larvin M. Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 4:CD002941.

- Baril NB, Ralls PW, Wren SM, et al. Does an infected peripancreatic fluid collection or abscess mandate operation? Ann Surg 2000; 231:361–367.

- Mouli VP, Sreenivas V, Garg PK. Efficacy of conservative treatment, without necrosectomy, for infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:333–340.e2.

- Kirby JM, Vora P, Midia M, Rawlinson J. Vascular complications of pancreatitis: imaging and intervention. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008; 31:957–970.

- De Waele JJ, Hoste E, Blot SI, Decruyenaere J, Colardyn F. Intra-abdominal hypertension in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Crit Care 2005; 9:R452–R457.

- van Brunschot S, Schut AJ, Bouwense SA, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Abdominal compartment syndrome in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas 2014; 43:665–674.

- Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M, et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: a review of the interventions. Int J Surg 2016; 28(suppl 1):S163–S171.

- Besselink MG, Verwer TJ, Schoenmaeckers EJ, et al. Timing of surgical intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg 2007; 142:1194–1201.

- van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Horvath KD, et al; Dutch Acute Pancreatis Study Group. Videoscopic assisted retroperitoneal debridement in infected necrotizing pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2007; 9:156–159.

- van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, Buskens E, van Ramshorst B, Gooszen HG; Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Case-matched comparison of the retroperitoneal approach with laparotomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Surg 2007; 31:1635–1642.

- van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1491–1502.

- Thompson CC, Kumar N, Slattery J, et al. A standardized method for endoscopic necrosectomy improves complication and mortality rates. Pancreatology 2016; 16:66–72.

- Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307:1053–1061.

Acute pancreatitis accounted for more than 300,000 admissions and $2.6 billion in associated healthcare costs in the United States in 2012.1 First-line management is early aggressive fluid resuscitation and analgesics for pain control. Guidelines recommend estimating the clinical severity of each attack using a validated scoring system such as the Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis.2 Clinically severe pancreatitis is associated with necrosis.

Acute pancreatitis results from inappropriate activation of zymogens and subsequent autodigestion of the pancreas by its own enzymes. Though necrotizing pancreatitis is thought to be an ischemic complication, its pathogenesis is not completely understood. Necrosis increases the morbidity and mortality risk of acute pancreatitis because of its association with organ failure and infectious complications. As such, patients with necrotizing pancreatitis may need admission to the intensive care unit, nutritional support, antibiotics, and radiologic, endoscopic, or surgical interventions.

Here, we review current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of necrotizing pancreatitis.

PROPER TERMINOLOGY HELPS COLLABORATION

Managing necrotizing pancreatitis requires the combined efforts of internists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. This collaboration is aided by proper terminology.

A classification system was devised in Atlanta, GA, in 1992 to facilitate communication and interdisciplinary collaboration.3 Severe pancreatitis was differentiated from mild by the presence of organ failure or the complications of pseudocyst, necrosis, or abscess.

The original Atlanta classification had several limitations. First, the terminology for fluid collections was ambiguous and frequently misused. Second, the assessment of clinical severity required either the Ranson score or the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, both of which are complex and have other limitations. Finally, advances in imaging and treatment have rendered the original Atlanta nomenclature obsolete.

In 2012, the Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group issued a revised Atlanta classification that modernized the terminology pertaining to natural history, severity, imaging features, and complications. It divides the natural course of acute pancreatitis into early and late phases.4

Early vs late phase

In the early phase, findings on computed tomography (CT) neither correlate with clinical severity nor alter clinical management.6 Thus, early imaging is not indicated unless there is diagnostic uncertainty, lack of response to appropriate treatment, or sudden deterioration.

Moderate pancreatitis describes patients with pancreatic necrosis with or without transient organ failure (organ dysfunction for ≤ 48 hours).

Severe pancreatitis is defined by pancreatic necrosis and persistent organ dysfunction.4 It may be accompanied by pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections; bacteremia and sepsis can occur in association with infection of necrotic collections.

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis vs necrotizing pancreatitis

The revised Atlanta classification maintains the original classification of acute pancreatitis into 2 main categories: interstitial edematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis.

Necrotizing pancreatitis is further divided into 3 subtypes based on extent and location of necrosis:

- Parenchymal necrosis alone (5% of cases)

- Necrosis of peripancreatic fat alone (20%)

- Necrosis of both parenchyma and peripancreatic fat (75%).

Peripancreatic involvement is commonly found in the mesentery, peripancreatic and distant retroperitoneum, and lesser sac.

Of the three subtypes, peripancreatic necrosis has the best prognosis. However, all of the subtypes of necrotizing pancreatitis are associated with poorer outcomes than interstitial edematous pancreatitis.

Fluid collections

Acute pancreatic fluid collections contain exclusively nonsolid components without an inflammatory wall and are typically found in the peripancreatic fat. These collections often resolve without intervention as the patient recovers. If they persist beyond 4 weeks and develop a nonepithelialized, fibrous wall, they become pseudocysts. Intervention is generally not recommended for pseudocysts unless they are symptomatic.

ROLE OF IMAGING

Radiographic imaging is not usually necessary to diagnose acute pancreatitis. However, it can be a valuable tool to clarify an ambiguous presentation, determine severity, and identify complications.

The timing and appropriate type of imaging are integral to obtaining useful data. Any imaging obtained in acute pancreatitis to evaluate necrosis should be performed at least 3 to 5 days from the initial symptom onset; if imaging is obtained before 72 hours, necrosis cannot be confidently excluded.8

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

CT is the imaging test of choice when evaluating acute pancreatitis. In addition, almost all percutaneous interventions are performed with CT guidance. The Balthazar score is the most well-known CT severity index. It is calculated based on the degree of inflammation, acute fluid collections, and parenchymal necrosis.9 However, a modified severity index incorporates extrapancreatic complications such as ascites and vascular compromise and was found to more strongly correlate with outcomes than the standard Balthazar score.10

Contrast-enhanced CT is performed in 2 phases:

The pancreatic parenchymal phase

The pancreatic parenchymal or late arterial phase is obtained approximately 40 to 45 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect necrosis in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and to assess the peripancreatic arteries for pseudoaneurysms in the late phase of acute pancreatitis.11

Pancreatic necrosis appears as an area of decreased parenchymal enhancement, either well-defined or heterogeneous. The normal pancreatic parenchyma has a postcontrast enhancement pattern similar to that of the spleen. Parenchyma that does not enhance to the same degree is considered necrotic. The severity of necrosis is graded based on the percentage of the pancreas involved (< 30%, 30%–50%, or > 50%), and a higher percentage correlates with a worse outcome.12,13

Peripancreatic necrosis is harder to detect, as there is no method to assess fat enhancement as there is with pancreatic parenchymal enhancement. In general, radiologists assume that heterogeneous peripancreatic changes, including areas of fat, fluid, and soft tissue attenuation, are consistent with peripancreatic necrosis. After 7 to 10 days, if these changes become more homogeneous and confluent with a more mass-like process, peripancreatic necrosis can be more confidently identified.12,13

The portal venous phase

The later, portal venous phase of the scan is obtained approximately 70 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect and characterize fluid collections and venous complications of the disease.

Drawbacks of CT

A drawback of CT is the need for iodinated intravenous contrast media, which in severely ill patients may precipitate or worsen pre-existing acute kidney injury.

Further, several studies have shown that findings on CT rarely alter the management of patients in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and in fact may be an overuse of medical resources.14 Unless there are confounding clinical signs or symptoms, CT should be delayed for at least 72 hours.9,10,14,15

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not a first-line imaging test in this disease because it is not as available as CT and takes longer to perform—20 to 30 minutes. The patient must be evaluated for candidacy, as it is difficult for acutely ill patients to tolerate an examination that takes this long and requires them to hold their breath multiple times.

MRI is an appropriate alternative in patients who are pregnant or who have severe iodinated-contrast allergy. While contrast is necessary to detect pancreatic necrosis with CT, MRI can detect necrosis without the need for contrast in patients with acute kidney injury or severe chronic kidney disease. Also, MRI may be better in complicated cases requiring repeated imaging because it does not expose the patient to radiation.

On MRI, pancreatic necrosis appears as a heterogeneous area, owing to its liquid and solid components. Liquid components appear hyperintense, and solid components hypointense, on T2 fluid-weighted imaging. This ability to differentiate the components of a walled-off pancreatic necrosis can be useful in determining whether a collection requires drainage or debridement. MRI is also more sensitive for hemorrhagic complications, best seen on T1 fat-weighted images.12,16

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is an excellent method for ductal evaluation through heavily T2-weighted imaging. It is more sensitive than CT for detecting common bile duct stones and can also detect pancreatic duct strictures or extravasation into fluid collections.16

SUPPORTIVE MANAGEMENT OF EARLY NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

In the early phase of necrotizing pancreatitis, management is supportive with the primary aim of preventing intravascular volume depletion. Aggressive fluid resuscitation in the first 48 to 72 hours, pain control, and bowel rest are the mainstays of supportive therapy. Intensive care may be necessary if organ failure and hemodynamic instability accompany necrotizing pancreatitis.

Prophylactic antibiotic and antifungal therapy to prevent infected necrosis has been controversial. Recent studies of its utility have not yielded supportive results, and the American College of Gastroenterology and the Infectious Diseases Society of America no longer recommend it.9,17 These medications should not be given unless concomitant cholangitis or extrapancreatic infection is clinically suspected.

Early enteral nutrition is recommended in patients in whom pancreatitis is predicted to be severe and in those not expected to resume oral intake within 5 to 7 days. Enteral nutrition most commonly involves bedside or endoscopic placement of a nasojejunal feeding tube and collaboration with a nutritionist to determine protein-caloric requirements.

Compared with enteral nutrition, total parenteral nutrition is associated with higher rates of infection, multiorgan dysfunction and failure, and death.18

MANAGING COMPLICATIONS OF PANCREATIC NECROSIS

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a defining complication of acute pancreatitis, and its presence alone indicates greater severity. However, superimposed complications may further worsen outcomes.

Infected pancreatic necrosis

Infection occurs in approximately 20% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and confers a mortality rate of 20% to 50%.19 Infected pancreatic necrosis occurs when gut organisms translocate into the nearby necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue. The most commonly identified organisms include Escherichia coli and Enterococcus species.20

This complication usually manifests 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset; earlier onset is uncommon to rare. It should be considered when the systemic inflammatory response syndrome persists or recurs after 10 days to 2 weeks. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is also common in sterile necrotizing pancreatitis and sometimes in interstitial pancreatitis, particularly during the first week. However, its sudden appearance or resurgence, high spiking fevers, or worsening organ failure in the later phase (2–4 weeks) of pancreatitis should heighten suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis.

Imaging may also help diagnose infection, and the presence of gas within a collection or region of necrosis is highly specific. However, the presence of gas is not completely sensitive for infection, as it is seen in only 12% to 22% of infected cases.

Before minimally invasive techniques became available, the diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis was confirmed by percutaneous CT-guided aspiration of the necrotic mass or collection for Gram stain and culture.

Antibiotic therapy is indicated in confirmed or suspected cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Antibiotics with gram-negative coverage and appropriate penetration such as carbapenems, metronidazole, fluoroquinolones, and selected cephalosporins are most commonly used. Meropenem is the antibiotic of choice at our institution.

CT-guided fine-needle aspiration is often done if suspected infected pancreatic necrosis fails to respond to empiric antibiotic therapy.

Debridement or drainage. Generally, the diagnosis or suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis (suggestive signs are high fever, elevated white blood cell count, and sepsis) warrants an intervention to debride or drain infected pancreatic tissue and control sepsis.21

While source control is integral to the successful treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis, antibiotic therapy may provide a bridge to intervention for critically ill patients by suppressing bacteremia and subsequent sepsis. A 2013 meta-analysis found that 324 of 409 patients with suspected infected pancreatic necrosis were successfully stabilized with antibiotic treatment.21,22 The trend toward conservative management and promising outcomes with antibiotic therapy alone or with minimally invasive techniques has lessened the need for diagnostic CT-guided fine-needle aspiration.

Hemorrhage

Spontaneous hemorrhage into pancreatic necrosis is a rare but life-threatening complication. Because CT is almost always performed with contrast enhancement, this complication is rarely identified with imaging. The diagnosis is made by noting a drop in hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Hemorrhage into the retroperitoneum or the peritoneal cavity, or both, can occur when an inflammatory process erodes into a nearby artery. Luminal gastrointestinal bleeding can occur from gastric varices arising from splenic vein thrombosis and resulting left-sided portal hypertension, or from pseudoaneurysms. These can also bleed into the pancreatic duct (hemosuccus pancreaticus). Pseudoaneurysm is a later complication that occurs when an arterial wall (most commonly the splenic or gastroduodenal artery) is weakened by pancreatic enzymes.23

Prompt recognition of hemorrhagic events and consultation with an interventional radiologist or surgeon are required to prevent death.

Inflammation and abdominal compartment syndrome

Inflammation from necrotizing pancreatitis can cause further complications by blocking nearby structures. Reported complications include jaundice from biliary compression, hydronephrosis from ureteral compression, bowel obstruction, and gastric outlet obstruction.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is an increasingly recognized complication of acute pancreatitis. Abdominal pressure can rise due to a number of factors, including fluid collections, ascites, ileus, and overly aggressive fluid resuscitation.24 Elevated abdominal pressure is associated with complications such as decreased respiratory compliance, increased peak airway pressure, decreased cardiac preload, hypotension, mesenteric and intestinal ischemia, feeding intolerance, and lower-extremity ischemia and thrombosis.

Patients with necrotizing pancreatitis who have abdominal compartment syndrome have a mortality rate 5 times higher than patients without abdominal compartment syndrome.25

Abdominal pressures should be monitored using a bladder pressure sensor in critically ill or ventilated patients with acute pancreatitis. If the abdominal pressure rises above 20 mm Hg, medical and surgical interventions should be offered in a stepwise fashion to decrease it. Interventions include decompression by nasogastric and rectal tube, sedation or paralysis to relax abdominal wall tension, minimization of intravenous fluids, percutaneous drainage of ascites, and (rarely) surgical midline or subcostal laparotomy.

ROLE OF INTERVENTION

The treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis has changed rapidly, thanks to a growing experience with minimally invasive techniques.

Indications for intervention

Infected pancreatic necrosis is the primary indication for surgical, percutaneous, or endoscopic intervention.

In sterile necrosis, the threshold for intervention is less clear, and intervention is often reserved for patients who fail to clinically improve or who have intractable abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or fistulating disease.26

In asymptomatic cases, intervention is almost never indicated regardless of the location or size of the necrotic area.

In walled-off pancreatic necrosis, less-invasive and less-morbid interventions such as endoscopic or percutaneous drainage or video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement can be done.

Timing of intervention

In the past, delaying intervention was thought to increase the risk of death. However, multiple studies have found that outcomes are often worse if intervention is done early, likely due to the lack of a fully formed fibrous wall or demarcation of the necrotic area.27

If the patient remains clinically stable, it is best to delay intervention until at least 4 weeks after the index event to achieve optimal outcomes. Delay can often be achieved by antibiotic treatment to suppress bacteremia and endoscopic or percutaneous drainage of infected collections to control sepsis.

Open surgery

The gold-standard intervention for infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis is open necrosectomy. This involves exploratory laparotomy with blunt debridement of all visible necrotic pancreatic tissue.

Methods to facilitate later evacuation of residual infected fluid and debris vary widely. Multiple large-caliber drains can be placed to facilitate irrigation and drainage before closure of the abdominal fascia. As infected pancreatic necrosis carries the risk of contaminating the peritoneal cavity, the skin is often left open to heal by secondary intention. An interventional radiologist is frequently enlisted to place, exchange, or downsize drainage catheters.

Infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis often requires more than one operation to achieve satisfactory debridement.

The goals of open necrosectomy are to remove nonviable tissue and infection, preserve viable pancreatic tissue, eliminate fistulous connections, and minimize damage to local organs and vasculature.

Minimally invasive techniques

Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement has been described as a hybrid between endoscopic and open retroperitoneal debridement.28 This technique requires first placing a percutaneous catheter into the necrotic area through the left flank to create a retroperitoneal tract. A 5-cm incision is made and the necrotic space is entered using the drain for guidance. Necrotic tissue is carefully debrided under direct vision using a combination of forceps, irrigation, and suction. A laparoscopic port can also be introduced into the incision when the procedure can no longer be continued under direct vision.29,30

Although not all patients are candidates for minimal-access surgery, it remains an evolving surgical option.

Endoscopic transmural debridement is another option for infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Depending on the location of the necrotic area, an echoendoscope is passed to either the stomach or duodenum. Guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, a needle is passed into the collection, allowing subsequent fistula creation and stenting for internal drainage or debridement. In the past, this process required several steps, multiple devices, fluoroscopic guidance, and considerable time. But newer endoscopic lumen-apposing metal stents have been developed that can be placed in a single step without fluoroscopy. A slimmer endoscope can then be introduced into the necrotic cavity via the stent, and the necrotic debris can be debrided with endoscopic baskets, snares, forceps, and irrigation.9,31

Similar to surgical necrosectomy, satisfactory debridement is not often obtained with a single procedure; 2 to 5 endoscopic procedures may be needed to achieve resolution. However, the luminal approach in endoscopic necrosectomy avoids the significant morbidity of major abdominal surgery and the potential for pancreaticocutaneous fistulae that may occur with drains.

In a randomized trial comparing endoscopic necrosectomy vs surgical necrosectomy (video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement and exploratory laparotomy),32 endoscopic necrosectomy showed less inflammatory response than surgical necrosectomy and had a lower risk of new-onset organ failure, bleeding, fistula formation, and death.32

Selecting the best intervention for the individual patient

Given the multiple available techniques, selecting the best intervention for individual patients can be challenging. A team approach with input from a gastroenterologist, surgeon, and interventional radiologist is best when determining which technique would best suit each patient.

Surgical necrosectomy is still the treatment of choice for unstable patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or multiple, inaccessible collections, but current evidence suggests a different approach in stable infected pancreatic necrosis and symptomatic sterile walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

The Dutch Pancreatitis Group28 randomized 88 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis or symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis to open necrosectomy or a minimally invasive “step-up” approach consisting of up to 2 percutaneous drainage or endoscopic debridement procedures before escalation to video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement. The step-up approach resulted in lower rates of morbidity and death than surgical necrosectomy as first-line treatment. Furthermore, some patients in the step-up group avoided the need for surgery entirely.30

SUMMING UP

Necrosis significantly increases rates of morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Hospitalists, general internists, and general surgeons are all on the front lines in identifying severe cases and consulting the appropriate specialists for optimal multidisciplinary care. Selective and appropriate timing of radiologic imaging is key, and a vital tool in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis.

While the primary indication for intervention is infected pancreatic necrosis, additional indications are symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis secondary to intractable abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, and failure to thrive. As a result of improving technology and inpatient care, these patients may present with intractable symptoms in the outpatient setting rather than the inpatient setting. The onus is on the primary care physician to maintain a high level of suspicion and refer these patients to subspecialists as appropriate.

Open surgical necrosectomy remains an important approach for care of infected pancreatic necrosis or patients with intractable symptoms. A step-up approach starting with a minimally invasive procedure and escalating if the initial intervention is unsuccessful is gradually becoming the standard of care.

Acute pancreatitis accounted for more than 300,000 admissions and $2.6 billion in associated healthcare costs in the United States in 2012.1 First-line management is early aggressive fluid resuscitation and analgesics for pain control. Guidelines recommend estimating the clinical severity of each attack using a validated scoring system such as the Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis.2 Clinically severe pancreatitis is associated with necrosis.

Acute pancreatitis results from inappropriate activation of zymogens and subsequent autodigestion of the pancreas by its own enzymes. Though necrotizing pancreatitis is thought to be an ischemic complication, its pathogenesis is not completely understood. Necrosis increases the morbidity and mortality risk of acute pancreatitis because of its association with organ failure and infectious complications. As such, patients with necrotizing pancreatitis may need admission to the intensive care unit, nutritional support, antibiotics, and radiologic, endoscopic, or surgical interventions.

Here, we review current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of necrotizing pancreatitis.

PROPER TERMINOLOGY HELPS COLLABORATION

Managing necrotizing pancreatitis requires the combined efforts of internists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. This collaboration is aided by proper terminology.

A classification system was devised in Atlanta, GA, in 1992 to facilitate communication and interdisciplinary collaboration.3 Severe pancreatitis was differentiated from mild by the presence of organ failure or the complications of pseudocyst, necrosis, or abscess.

The original Atlanta classification had several limitations. First, the terminology for fluid collections was ambiguous and frequently misused. Second, the assessment of clinical severity required either the Ranson score or the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, both of which are complex and have other limitations. Finally, advances in imaging and treatment have rendered the original Atlanta nomenclature obsolete.

In 2012, the Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group issued a revised Atlanta classification that modernized the terminology pertaining to natural history, severity, imaging features, and complications. It divides the natural course of acute pancreatitis into early and late phases.4

Early vs late phase

In the early phase, findings on computed tomography (CT) neither correlate with clinical severity nor alter clinical management.6 Thus, early imaging is not indicated unless there is diagnostic uncertainty, lack of response to appropriate treatment, or sudden deterioration.

Moderate pancreatitis describes patients with pancreatic necrosis with or without transient organ failure (organ dysfunction for ≤ 48 hours).

Severe pancreatitis is defined by pancreatic necrosis and persistent organ dysfunction.4 It may be accompanied by pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections; bacteremia and sepsis can occur in association with infection of necrotic collections.

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis vs necrotizing pancreatitis

The revised Atlanta classification maintains the original classification of acute pancreatitis into 2 main categories: interstitial edematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis.

Necrotizing pancreatitis is further divided into 3 subtypes based on extent and location of necrosis:

- Parenchymal necrosis alone (5% of cases)

- Necrosis of peripancreatic fat alone (20%)

- Necrosis of both parenchyma and peripancreatic fat (75%).

Peripancreatic involvement is commonly found in the mesentery, peripancreatic and distant retroperitoneum, and lesser sac.

Of the three subtypes, peripancreatic necrosis has the best prognosis. However, all of the subtypes of necrotizing pancreatitis are associated with poorer outcomes than interstitial edematous pancreatitis.

Fluid collections

Acute pancreatic fluid collections contain exclusively nonsolid components without an inflammatory wall and are typically found in the peripancreatic fat. These collections often resolve without intervention as the patient recovers. If they persist beyond 4 weeks and develop a nonepithelialized, fibrous wall, they become pseudocysts. Intervention is generally not recommended for pseudocysts unless they are symptomatic.

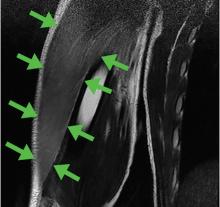

ROLE OF IMAGING

Radiographic imaging is not usually necessary to diagnose acute pancreatitis. However, it can be a valuable tool to clarify an ambiguous presentation, determine severity, and identify complications.

The timing and appropriate type of imaging are integral to obtaining useful data. Any imaging obtained in acute pancreatitis to evaluate necrosis should be performed at least 3 to 5 days from the initial symptom onset; if imaging is obtained before 72 hours, necrosis cannot be confidently excluded.8

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

CT is the imaging test of choice when evaluating acute pancreatitis. In addition, almost all percutaneous interventions are performed with CT guidance. The Balthazar score is the most well-known CT severity index. It is calculated based on the degree of inflammation, acute fluid collections, and parenchymal necrosis.9 However, a modified severity index incorporates extrapancreatic complications such as ascites and vascular compromise and was found to more strongly correlate with outcomes than the standard Balthazar score.10

Contrast-enhanced CT is performed in 2 phases:

The pancreatic parenchymal phase

The pancreatic parenchymal or late arterial phase is obtained approximately 40 to 45 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect necrosis in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and to assess the peripancreatic arteries for pseudoaneurysms in the late phase of acute pancreatitis.11

Pancreatic necrosis appears as an area of decreased parenchymal enhancement, either well-defined or heterogeneous. The normal pancreatic parenchyma has a postcontrast enhancement pattern similar to that of the spleen. Parenchyma that does not enhance to the same degree is considered necrotic. The severity of necrosis is graded based on the percentage of the pancreas involved (< 30%, 30%–50%, or > 50%), and a higher percentage correlates with a worse outcome.12,13

Peripancreatic necrosis is harder to detect, as there is no method to assess fat enhancement as there is with pancreatic parenchymal enhancement. In general, radiologists assume that heterogeneous peripancreatic changes, including areas of fat, fluid, and soft tissue attenuation, are consistent with peripancreatic necrosis. After 7 to 10 days, if these changes become more homogeneous and confluent with a more mass-like process, peripancreatic necrosis can be more confidently identified.12,13

The portal venous phase

The later, portal venous phase of the scan is obtained approximately 70 seconds after the start of the contrast bolus. It is used to detect and characterize fluid collections and venous complications of the disease.

Drawbacks of CT

A drawback of CT is the need for iodinated intravenous contrast media, which in severely ill patients may precipitate or worsen pre-existing acute kidney injury.

Further, several studies have shown that findings on CT rarely alter the management of patients in the early phase of acute pancreatitis and in fact may be an overuse of medical resources.14 Unless there are confounding clinical signs or symptoms, CT should be delayed for at least 72 hours.9,10,14,15

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not a first-line imaging test in this disease because it is not as available as CT and takes longer to perform—20 to 30 minutes. The patient must be evaluated for candidacy, as it is difficult for acutely ill patients to tolerate an examination that takes this long and requires them to hold their breath multiple times.

MRI is an appropriate alternative in patients who are pregnant or who have severe iodinated-contrast allergy. While contrast is necessary to detect pancreatic necrosis with CT, MRI can detect necrosis without the need for contrast in patients with acute kidney injury or severe chronic kidney disease. Also, MRI may be better in complicated cases requiring repeated imaging because it does not expose the patient to radiation.

On MRI, pancreatic necrosis appears as a heterogeneous area, owing to its liquid and solid components. Liquid components appear hyperintense, and solid components hypointense, on T2 fluid-weighted imaging. This ability to differentiate the components of a walled-off pancreatic necrosis can be useful in determining whether a collection requires drainage or debridement. MRI is also more sensitive for hemorrhagic complications, best seen on T1 fat-weighted images.12,16

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is an excellent method for ductal evaluation through heavily T2-weighted imaging. It is more sensitive than CT for detecting common bile duct stones and can also detect pancreatic duct strictures or extravasation into fluid collections.16

SUPPORTIVE MANAGEMENT OF EARLY NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

In the early phase of necrotizing pancreatitis, management is supportive with the primary aim of preventing intravascular volume depletion. Aggressive fluid resuscitation in the first 48 to 72 hours, pain control, and bowel rest are the mainstays of supportive therapy. Intensive care may be necessary if organ failure and hemodynamic instability accompany necrotizing pancreatitis.

Prophylactic antibiotic and antifungal therapy to prevent infected necrosis has been controversial. Recent studies of its utility have not yielded supportive results, and the American College of Gastroenterology and the Infectious Diseases Society of America no longer recommend it.9,17 These medications should not be given unless concomitant cholangitis or extrapancreatic infection is clinically suspected.

Early enteral nutrition is recommended in patients in whom pancreatitis is predicted to be severe and in those not expected to resume oral intake within 5 to 7 days. Enteral nutrition most commonly involves bedside or endoscopic placement of a nasojejunal feeding tube and collaboration with a nutritionist to determine protein-caloric requirements.

Compared with enteral nutrition, total parenteral nutrition is associated with higher rates of infection, multiorgan dysfunction and failure, and death.18

MANAGING COMPLICATIONS OF PANCREATIC NECROSIS

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a defining complication of acute pancreatitis, and its presence alone indicates greater severity. However, superimposed complications may further worsen outcomes.

Infected pancreatic necrosis

Infection occurs in approximately 20% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and confers a mortality rate of 20% to 50%.19 Infected pancreatic necrosis occurs when gut organisms translocate into the nearby necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue. The most commonly identified organisms include Escherichia coli and Enterococcus species.20

This complication usually manifests 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset; earlier onset is uncommon to rare. It should be considered when the systemic inflammatory response syndrome persists or recurs after 10 days to 2 weeks. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is also common in sterile necrotizing pancreatitis and sometimes in interstitial pancreatitis, particularly during the first week. However, its sudden appearance or resurgence, high spiking fevers, or worsening organ failure in the later phase (2–4 weeks) of pancreatitis should heighten suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis.

Imaging may also help diagnose infection, and the presence of gas within a collection or region of necrosis is highly specific. However, the presence of gas is not completely sensitive for infection, as it is seen in only 12% to 22% of infected cases.

Before minimally invasive techniques became available, the diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis was confirmed by percutaneous CT-guided aspiration of the necrotic mass or collection for Gram stain and culture.

Antibiotic therapy is indicated in confirmed or suspected cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Antibiotics with gram-negative coverage and appropriate penetration such as carbapenems, metronidazole, fluoroquinolones, and selected cephalosporins are most commonly used. Meropenem is the antibiotic of choice at our institution.

CT-guided fine-needle aspiration is often done if suspected infected pancreatic necrosis fails to respond to empiric antibiotic therapy.

Debridement or drainage. Generally, the diagnosis or suspicion of infected pancreatic necrosis (suggestive signs are high fever, elevated white blood cell count, and sepsis) warrants an intervention to debride or drain infected pancreatic tissue and control sepsis.21