User login

Things We Do for No Reason: Prescribing Docusate for Constipation in Hospitalized Adults

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

Click here for the Choosing Wisely website.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 80-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents with a mechanical fall. X-rays are notable for a right hip fracture. She is treated with morphine for analgesia and evaluated by orthopedic surgery for surgical repair. The hospitalist recognizes that this patient is at high risk for constipation and orders docusate for prevention of constipation.

BACKGROUND

Constipation is a highly prevalent problem in all practice settings, especially in the hospital, affecting two out of five hospitalized patients.1 Multiple factors in the inpatient setting contribute to constipation, including decreased mobility, medical comorbidities, postsurgical ileus, anesthetics, and medications such as opioid analgesics. Furthermore, the inpatient population is aging in parallel with the general population and constipation is more common in the elderly, likely owing to a combination of decreased muscle mass and impaired function of autonomic nerves.2 Consequently, inpatient providers frequently treat constipation or try to prevent it using stool softeners or laxatives.

One of the most commonly prescribed agents, regardless of medical specialty, is docusate, also known as dioctyl sulfosuccinate or by its brand name, Colace. A study from McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Canada reported that docusate was the most frequently prescribed laxative, accounting for 64% of laxative medication doses, with associated costs approaching $60,000 per year.3 Direct drug costs accounted for a quarter of the expenses, and the remaining three quarters were estimated labor costs for administration. Medical and surgical admissions shared similar proportions of usage, with an average of 10 doses of docusate per admission across 17,064 admissions. Furthermore, half of the patients were prescribed docusate upon discharge. The authors extrapolated their data to suggest that total healthcare spending in North America on docusate products likely exceeds $100,000,000 yearly. A second study from Toronto found that 15% of all hospitalized patients are prescribed at least one dose of docusate, and that one-third of all new inpatient prescriptions are continued at discharge.4

WHY YOU THINK DOCUSATE MIGHT BE HELPFUL FOR CONSTIPATION

Docusate is thought to act as a detergent to retain water in the stool, thereby acting as a stool softener to facilitate stool passage. Physicians have prescribed docusate for decades, and attendings have passed down the practice of prescribing docusate for constipation to medical trainees for generations. The initial docusate studies showed promise, as it softened the stool by increasing its water content and made it easier to pass through the intestines.5 One of the earliest human studies compared docusate to an unspecified placebo in 35 elderly patients with chronic atonic constipation and found a decreased need for enemas.6 Some other observational studies also reported a decreased need for manual disimpactions and enemas in elderly populations.7,8 One randomized, controlled trial from 1968 showed an increased frequency of bowel movements compared to placebo, but it excluded half of the enrolled patients because they had a positive placebo response.9 Since those early studies from the 1950s and 1960s, docusate remains widely accepted as an effective stool softener with positive endorsements from hospital formularies and order sets and patient information sheets such as the JAMA Patient Page.10 Furthermore, the World Health Organization lists docusate as an “essential medicine,” reinforcing the notion that it is effective.11

WHY THERE IS NO REASON TO PRESCRIBE DOCUSATE FOR CONSTIPATION

Despite common practice, the efficacy of docusate as a stool softener has not been borne out by rigorous scientific data. On the contrary, multiple randomized controlled trials have failed to show any significant efficacy of this drug over placebo (Table).

The initial trial in 1976 studied 34 elderly patients on a general medical ward for prophylaxis of constipation.12 They randomized patients to 100 mg twice daily of docusate sodium versus a control group that did not receive any type of laxative. The number of bowel movements and their character served as the measured outcomes. The study demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the frequency and character of bowel movements between the docusate and placebo groups. Even at that time, the authors questioned whether docusate had any efficacy at all: “[w]hether the drug actually offers anything beyond a placebo effect in preventing constipation is in doubt.”

Another trial in 1978 studied 46 elderly, institutionalized patients with chronic functional constipation.13 All patients underwent a two-week placebo period followed by a three-week treatment period with three arms of randomization: docusate sodium 100 mg daily, docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily, or docusate calcium 240 mg daily. Patients received enemas or suppositories if required. All three arms showed an increase in the average number of natural bowel movements when compared to each patient’s own placebo period, but only the arm with docusate calcium reached statistical significance (P < .02). According to the authors, none of the therapies appeared to have a significant effect on stool consistency. The authors hypothesized that the higher dose given to the docusate calcium arm may have been the reason for the apparent efficacy in this cohort. As such, studies with higher doses of docusate calcium would be reasonable.

A third study in 1985 compared docusate sodium 100 mg three times daily versus placebo in six healthy patients with ileostomies and six healthy volunteers.14 Therapy with docusate “had no effect on stool weight, stool frequency, stool water, or mean transit time.”

Another study in 1991 evaluated 15 elderly nursing home residents with a randomized, double-blind crossover design.15 Subjects received 240 mg twice daily of docusate calcium versus placebo for three weeks and then crossed over to other arm after a two-week wash-out period. The investigators found no difference in the number of bowel movements per week or in the need for additional laxatives between the two study periods. There were also no differences in the patients’ subjective experience of constipation or discomfort with defecation.

Larger studies were subsequently initiated in more recent years. In 1998, a randomized controlled trial in 170 subjects with chronic idiopathic constipation compared psyllium 5.1 g twice daily and docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily with a corresponding placebo in each arm for a treatment duration of two weeks after a two-week placebo baseline period.16 Psyllium was found to increase stool water content and stool water weight over the baseline period, while docusate essentially had no effect on stool water content or water weight. Furthermore, by treatment week 2, psyllium demonstrated an increase in the frequency of bowel movements, whereas docusate did not. It should be noted that this study was funded by Procter & Gamble, which manufactures Metamucil, a popular brand of psyllium.

Lastly, the most recent randomized controlled trial was published in 2013. It included 74 hospice patients in Canada, comparing docusate 200 mg and sennosides twice daily versus placebo and sennosides for 10 days. The study found no difference in stool frequency, volume, or consistency between docusate and placebo.17

A number of systematic reviews have studied the literature on bowel regimens and have noted the paucity of high-quality data supporting the efficacy of docusate, despite its widespread use.18-22 With these weak data, multiple authors have advocated for removing docusate from hospital formularies and using hospitalizations as an opportunity to deprescribe this medication to reduce polypharmacy. 3,4,23

Although docusate is considered a benign therapy, there is certainly potential for harm to the patient and detrimental effects on the healthcare system. Patients commonly complain about the unpleasant taste and lingering aftertaste, which may lead to decreased oral intake and worsening nutritional status.23 Furthermore, docusate may impact the absorption and effectiveness of other proven treatments.23 Perhaps the most important harm is that providers needlessly wait for docusate to fail before prescribing effective therapies for constipation. This process negatively impacts patient satisfaction and potentially increases healthcare costs if hospital length of stay is increased. Another important consideration is that patients may refuse truly necessary medications due to the excessive pill burden.

Costs to the healthcare system are increased needlessly when medications that do not improve outcomes are prescribed. Although the individual pill cost is low, the widespread use and the associated pharmacy and nursing resources required for administration create an estimated cost for docusate over $100,000,000 per year for North America alone.3 The staff time required for administration may prevent healthcare personnel from engaging in other more valuable tasks. Additionally, every medication order creates an opportunity for medical error. Lastly, bacteria were recently found contaminating the liquid formulation, which carries its own obvious implications if patients develop iatrogenic infections.24

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of using docusate, prescribe agents with established efficacy. In 2006, a systematic review published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology graded the evidence behind different therapies for chronic constipation.21 They found good evidence (Grade A) to support the use of polyethylene glycol (PEG), while psyllium and lactulose had moderate evidence (Grade B) to support their use. All other currently available agents that were reviewed had poor evidence to support their use. A more recent study in people prescribed opioids similarly found evidence to support the use of polyethylene glycol, lactulose, and sennosides.25 Lastly, the 2016 guidelines from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons do not mention docusate, though they comment on the paucity of data on stool softeners. Their recommendations for laxative therapy are similar to those of the previously discussed reviews.26 Ultimately, the choice of therapy, pharmacological and nonpharmacological, should be individualized for each patient based on the clinical context and cause of constipation. Nonpharmacologic treatments include dietary modification, mobilization, chewing gum, and biofeedback. If pharmacotherapy is required, use laxatives with the strongest evidence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- In patients with constipation or at risk for constipation, use laxatives with proven efficacy (such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides) for treatment or prophylaxis of constipation instead of using docusate.

- Discuss de-prescription for patients using docusate prior to admission.

- Remove docusate from your hospital formulary.

CONCLUSION

Docusate is commonly used for the treatment and prevention of constipation in hospitalized patients, with significant associated costs. This common practice continues despite little evidence supporting its efficacy and many trials failing to show benefits over placebo. Decreased utilization of ineffective therapies such as docusate is recommended. Returning to the case presentation, the hospitalist should start the patient on alternative therapies, instead of docusate, such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides, which have better evidence supporting their use.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosures

All authors deny any relevant conflict of interest with the attached manuscript.

1. Noiesen E, Trosborg I, Bager L, Herning M, Lyngby C, Konradsen H. Constipation--prevalence and incidence among medical patients acutely admitted to hospital with a medical condition. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2295-2302. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12511.

2. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, Eusebi LH, Bazzoli F, Chiarioni G. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3.

3. Lee TC, McDonald EG, Bonnici A, Tamblyn R. Pattern of inpatient laxative use: waste not, want not. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1216-1217. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2775.

4. MacMillan TE, Kamali R, Cavalcanti RB. Missed opportunity to deprescribe: docusate for constipation in medical inpatients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001 e1001-1007. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.04.008.

5. Spiesman MG, Malow L. New fecal softener (doxinate) in the treatment of constipation. J Lancet. 1956;76(6):164-167.

6. Harris R. Constipation in geriatrics; management with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate. Am J Dig Dis. Sep 1957;2(9):487-492.

7. Smigel JO, Lowe KJ, Hosp PH, Gibson JH. Constipation in elderly patients; treatment with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate plus peristim. Med Times. 1958;86(12):1521-1526.

8. Wilson JL, Dickinson DG. Use of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (aerosol O.T.) for severe constipation. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;158(4):261-263. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960040019006a.

9. Hyland CM, Foran JD. Dioctyl sodium sulphosuccinate as a laxative in the elderly. Practitioner. 1968;200(199):698-699.

10. Jin J. JAMA patient page. Over-the-counter laxatives. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2078.

11. 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015). 2015; http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/.

12. Goodman J, Pang J, Bessman AN. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate- an ineffective prophylactic laxative. J Chronic Dis. 1976;29(1):59-63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(76)90068-0.

13. Fain AM, Susat R, Herring M, Dorton K. Treatment of constipation in geriatric and chronically ill patients: a comparison. South Med J. 1978;71(6):677-680.

14. Chapman RW, Sillery J, Fontana DD, Matthys C, Saunders DR. Effect of oral dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate on intake-output studies of human small and large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1985;89(3):489-493. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90441-X.

15. Castle SC, Cantrell M, Israel DS, Samuelson MJ. Constipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questioned. Geriatrics. 1991;46(11):84-86.

16. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(5):491-497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00336.x.

17. Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(1):2-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.008.

18. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, Stone P. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD003448.

19. Hurdon V, Viola R, Schroder C. How useful is docusate in patients at risk for constipation? A systematic review of the evidence in the chronically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):130-136. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00157-8.

20. Pare P, Fedorak RN. Systematic review of stimulant and nonstimulant laxatives for the treatment of functional constipation. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(10):549-557.

21. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):936-971. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x

22. Health CAfDaTi. Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate (calcium or sodium) for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Ottawa (ON)2014.

23. McKee KY, Widera E. Habitual prescribing of laxatives-it’s time to flush outdated protocols down the drain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1217-1219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2780.

24. Marquez L, Jones KN, Whaley EM, et al. An outbreak of burkholderia cepacia complex infections associated with contaminated liquid docusate. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(5):567-573. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.11.

25. Ahmedzai SH, Boland J. Constipation in people prescribed opioids. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010.

26. Paquette IM, Varma M, Ternent C, et al. The American society of colon and rectal surgeons’ clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(6):479-492. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000599

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

Click here for the Choosing Wisely website.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 80-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents with a mechanical fall. X-rays are notable for a right hip fracture. She is treated with morphine for analgesia and evaluated by orthopedic surgery for surgical repair. The hospitalist recognizes that this patient is at high risk for constipation and orders docusate for prevention of constipation.

BACKGROUND

Constipation is a highly prevalent problem in all practice settings, especially in the hospital, affecting two out of five hospitalized patients.1 Multiple factors in the inpatient setting contribute to constipation, including decreased mobility, medical comorbidities, postsurgical ileus, anesthetics, and medications such as opioid analgesics. Furthermore, the inpatient population is aging in parallel with the general population and constipation is more common in the elderly, likely owing to a combination of decreased muscle mass and impaired function of autonomic nerves.2 Consequently, inpatient providers frequently treat constipation or try to prevent it using stool softeners or laxatives.

One of the most commonly prescribed agents, regardless of medical specialty, is docusate, also known as dioctyl sulfosuccinate or by its brand name, Colace. A study from McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Canada reported that docusate was the most frequently prescribed laxative, accounting for 64% of laxative medication doses, with associated costs approaching $60,000 per year.3 Direct drug costs accounted for a quarter of the expenses, and the remaining three quarters were estimated labor costs for administration. Medical and surgical admissions shared similar proportions of usage, with an average of 10 doses of docusate per admission across 17,064 admissions. Furthermore, half of the patients were prescribed docusate upon discharge. The authors extrapolated their data to suggest that total healthcare spending in North America on docusate products likely exceeds $100,000,000 yearly. A second study from Toronto found that 15% of all hospitalized patients are prescribed at least one dose of docusate, and that one-third of all new inpatient prescriptions are continued at discharge.4

WHY YOU THINK DOCUSATE MIGHT BE HELPFUL FOR CONSTIPATION

Docusate is thought to act as a detergent to retain water in the stool, thereby acting as a stool softener to facilitate stool passage. Physicians have prescribed docusate for decades, and attendings have passed down the practice of prescribing docusate for constipation to medical trainees for generations. The initial docusate studies showed promise, as it softened the stool by increasing its water content and made it easier to pass through the intestines.5 One of the earliest human studies compared docusate to an unspecified placebo in 35 elderly patients with chronic atonic constipation and found a decreased need for enemas.6 Some other observational studies also reported a decreased need for manual disimpactions and enemas in elderly populations.7,8 One randomized, controlled trial from 1968 showed an increased frequency of bowel movements compared to placebo, but it excluded half of the enrolled patients because they had a positive placebo response.9 Since those early studies from the 1950s and 1960s, docusate remains widely accepted as an effective stool softener with positive endorsements from hospital formularies and order sets and patient information sheets such as the JAMA Patient Page.10 Furthermore, the World Health Organization lists docusate as an “essential medicine,” reinforcing the notion that it is effective.11

WHY THERE IS NO REASON TO PRESCRIBE DOCUSATE FOR CONSTIPATION

Despite common practice, the efficacy of docusate as a stool softener has not been borne out by rigorous scientific data. On the contrary, multiple randomized controlled trials have failed to show any significant efficacy of this drug over placebo (Table).

The initial trial in 1976 studied 34 elderly patients on a general medical ward for prophylaxis of constipation.12 They randomized patients to 100 mg twice daily of docusate sodium versus a control group that did not receive any type of laxative. The number of bowel movements and their character served as the measured outcomes. The study demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the frequency and character of bowel movements between the docusate and placebo groups. Even at that time, the authors questioned whether docusate had any efficacy at all: “[w]hether the drug actually offers anything beyond a placebo effect in preventing constipation is in doubt.”

Another trial in 1978 studied 46 elderly, institutionalized patients with chronic functional constipation.13 All patients underwent a two-week placebo period followed by a three-week treatment period with three arms of randomization: docusate sodium 100 mg daily, docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily, or docusate calcium 240 mg daily. Patients received enemas or suppositories if required. All three arms showed an increase in the average number of natural bowel movements when compared to each patient’s own placebo period, but only the arm with docusate calcium reached statistical significance (P < .02). According to the authors, none of the therapies appeared to have a significant effect on stool consistency. The authors hypothesized that the higher dose given to the docusate calcium arm may have been the reason for the apparent efficacy in this cohort. As such, studies with higher doses of docusate calcium would be reasonable.

A third study in 1985 compared docusate sodium 100 mg three times daily versus placebo in six healthy patients with ileostomies and six healthy volunteers.14 Therapy with docusate “had no effect on stool weight, stool frequency, stool water, or mean transit time.”

Another study in 1991 evaluated 15 elderly nursing home residents with a randomized, double-blind crossover design.15 Subjects received 240 mg twice daily of docusate calcium versus placebo for three weeks and then crossed over to other arm after a two-week wash-out period. The investigators found no difference in the number of bowel movements per week or in the need for additional laxatives between the two study periods. There were also no differences in the patients’ subjective experience of constipation or discomfort with defecation.

Larger studies were subsequently initiated in more recent years. In 1998, a randomized controlled trial in 170 subjects with chronic idiopathic constipation compared psyllium 5.1 g twice daily and docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily with a corresponding placebo in each arm for a treatment duration of two weeks after a two-week placebo baseline period.16 Psyllium was found to increase stool water content and stool water weight over the baseline period, while docusate essentially had no effect on stool water content or water weight. Furthermore, by treatment week 2, psyllium demonstrated an increase in the frequency of bowel movements, whereas docusate did not. It should be noted that this study was funded by Procter & Gamble, which manufactures Metamucil, a popular brand of psyllium.

Lastly, the most recent randomized controlled trial was published in 2013. It included 74 hospice patients in Canada, comparing docusate 200 mg and sennosides twice daily versus placebo and sennosides for 10 days. The study found no difference in stool frequency, volume, or consistency between docusate and placebo.17

A number of systematic reviews have studied the literature on bowel regimens and have noted the paucity of high-quality data supporting the efficacy of docusate, despite its widespread use.18-22 With these weak data, multiple authors have advocated for removing docusate from hospital formularies and using hospitalizations as an opportunity to deprescribe this medication to reduce polypharmacy. 3,4,23

Although docusate is considered a benign therapy, there is certainly potential for harm to the patient and detrimental effects on the healthcare system. Patients commonly complain about the unpleasant taste and lingering aftertaste, which may lead to decreased oral intake and worsening nutritional status.23 Furthermore, docusate may impact the absorption and effectiveness of other proven treatments.23 Perhaps the most important harm is that providers needlessly wait for docusate to fail before prescribing effective therapies for constipation. This process negatively impacts patient satisfaction and potentially increases healthcare costs if hospital length of stay is increased. Another important consideration is that patients may refuse truly necessary medications due to the excessive pill burden.

Costs to the healthcare system are increased needlessly when medications that do not improve outcomes are prescribed. Although the individual pill cost is low, the widespread use and the associated pharmacy and nursing resources required for administration create an estimated cost for docusate over $100,000,000 per year for North America alone.3 The staff time required for administration may prevent healthcare personnel from engaging in other more valuable tasks. Additionally, every medication order creates an opportunity for medical error. Lastly, bacteria were recently found contaminating the liquid formulation, which carries its own obvious implications if patients develop iatrogenic infections.24

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of using docusate, prescribe agents with established efficacy. In 2006, a systematic review published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology graded the evidence behind different therapies for chronic constipation.21 They found good evidence (Grade A) to support the use of polyethylene glycol (PEG), while psyllium and lactulose had moderate evidence (Grade B) to support their use. All other currently available agents that were reviewed had poor evidence to support their use. A more recent study in people prescribed opioids similarly found evidence to support the use of polyethylene glycol, lactulose, and sennosides.25 Lastly, the 2016 guidelines from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons do not mention docusate, though they comment on the paucity of data on stool softeners. Their recommendations for laxative therapy are similar to those of the previously discussed reviews.26 Ultimately, the choice of therapy, pharmacological and nonpharmacological, should be individualized for each patient based on the clinical context and cause of constipation. Nonpharmacologic treatments include dietary modification, mobilization, chewing gum, and biofeedback. If pharmacotherapy is required, use laxatives with the strongest evidence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- In patients with constipation or at risk for constipation, use laxatives with proven efficacy (such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides) for treatment or prophylaxis of constipation instead of using docusate.

- Discuss de-prescription for patients using docusate prior to admission.

- Remove docusate from your hospital formulary.

CONCLUSION

Docusate is commonly used for the treatment and prevention of constipation in hospitalized patients, with significant associated costs. This common practice continues despite little evidence supporting its efficacy and many trials failing to show benefits over placebo. Decreased utilization of ineffective therapies such as docusate is recommended. Returning to the case presentation, the hospitalist should start the patient on alternative therapies, instead of docusate, such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides, which have better evidence supporting their use.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosures

All authors deny any relevant conflict of interest with the attached manuscript.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

Click here for the Choosing Wisely website.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 80-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents with a mechanical fall. X-rays are notable for a right hip fracture. She is treated with morphine for analgesia and evaluated by orthopedic surgery for surgical repair. The hospitalist recognizes that this patient is at high risk for constipation and orders docusate for prevention of constipation.

BACKGROUND

Constipation is a highly prevalent problem in all practice settings, especially in the hospital, affecting two out of five hospitalized patients.1 Multiple factors in the inpatient setting contribute to constipation, including decreased mobility, medical comorbidities, postsurgical ileus, anesthetics, and medications such as opioid analgesics. Furthermore, the inpatient population is aging in parallel with the general population and constipation is more common in the elderly, likely owing to a combination of decreased muscle mass and impaired function of autonomic nerves.2 Consequently, inpatient providers frequently treat constipation or try to prevent it using stool softeners or laxatives.

One of the most commonly prescribed agents, regardless of medical specialty, is docusate, also known as dioctyl sulfosuccinate or by its brand name, Colace. A study from McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Canada reported that docusate was the most frequently prescribed laxative, accounting for 64% of laxative medication doses, with associated costs approaching $60,000 per year.3 Direct drug costs accounted for a quarter of the expenses, and the remaining three quarters were estimated labor costs for administration. Medical and surgical admissions shared similar proportions of usage, with an average of 10 doses of docusate per admission across 17,064 admissions. Furthermore, half of the patients were prescribed docusate upon discharge. The authors extrapolated their data to suggest that total healthcare spending in North America on docusate products likely exceeds $100,000,000 yearly. A second study from Toronto found that 15% of all hospitalized patients are prescribed at least one dose of docusate, and that one-third of all new inpatient prescriptions are continued at discharge.4

WHY YOU THINK DOCUSATE MIGHT BE HELPFUL FOR CONSTIPATION

Docusate is thought to act as a detergent to retain water in the stool, thereby acting as a stool softener to facilitate stool passage. Physicians have prescribed docusate for decades, and attendings have passed down the practice of prescribing docusate for constipation to medical trainees for generations. The initial docusate studies showed promise, as it softened the stool by increasing its water content and made it easier to pass through the intestines.5 One of the earliest human studies compared docusate to an unspecified placebo in 35 elderly patients with chronic atonic constipation and found a decreased need for enemas.6 Some other observational studies also reported a decreased need for manual disimpactions and enemas in elderly populations.7,8 One randomized, controlled trial from 1968 showed an increased frequency of bowel movements compared to placebo, but it excluded half of the enrolled patients because they had a positive placebo response.9 Since those early studies from the 1950s and 1960s, docusate remains widely accepted as an effective stool softener with positive endorsements from hospital formularies and order sets and patient information sheets such as the JAMA Patient Page.10 Furthermore, the World Health Organization lists docusate as an “essential medicine,” reinforcing the notion that it is effective.11

WHY THERE IS NO REASON TO PRESCRIBE DOCUSATE FOR CONSTIPATION

Despite common practice, the efficacy of docusate as a stool softener has not been borne out by rigorous scientific data. On the contrary, multiple randomized controlled trials have failed to show any significant efficacy of this drug over placebo (Table).

The initial trial in 1976 studied 34 elderly patients on a general medical ward for prophylaxis of constipation.12 They randomized patients to 100 mg twice daily of docusate sodium versus a control group that did not receive any type of laxative. The number of bowel movements and their character served as the measured outcomes. The study demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the frequency and character of bowel movements between the docusate and placebo groups. Even at that time, the authors questioned whether docusate had any efficacy at all: “[w]hether the drug actually offers anything beyond a placebo effect in preventing constipation is in doubt.”

Another trial in 1978 studied 46 elderly, institutionalized patients with chronic functional constipation.13 All patients underwent a two-week placebo period followed by a three-week treatment period with three arms of randomization: docusate sodium 100 mg daily, docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily, or docusate calcium 240 mg daily. Patients received enemas or suppositories if required. All three arms showed an increase in the average number of natural bowel movements when compared to each patient’s own placebo period, but only the arm with docusate calcium reached statistical significance (P < .02). According to the authors, none of the therapies appeared to have a significant effect on stool consistency. The authors hypothesized that the higher dose given to the docusate calcium arm may have been the reason for the apparent efficacy in this cohort. As such, studies with higher doses of docusate calcium would be reasonable.

A third study in 1985 compared docusate sodium 100 mg three times daily versus placebo in six healthy patients with ileostomies and six healthy volunteers.14 Therapy with docusate “had no effect on stool weight, stool frequency, stool water, or mean transit time.”

Another study in 1991 evaluated 15 elderly nursing home residents with a randomized, double-blind crossover design.15 Subjects received 240 mg twice daily of docusate calcium versus placebo for three weeks and then crossed over to other arm after a two-week wash-out period. The investigators found no difference in the number of bowel movements per week or in the need for additional laxatives between the two study periods. There were also no differences in the patients’ subjective experience of constipation or discomfort with defecation.

Larger studies were subsequently initiated in more recent years. In 1998, a randomized controlled trial in 170 subjects with chronic idiopathic constipation compared psyllium 5.1 g twice daily and docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily with a corresponding placebo in each arm for a treatment duration of two weeks after a two-week placebo baseline period.16 Psyllium was found to increase stool water content and stool water weight over the baseline period, while docusate essentially had no effect on stool water content or water weight. Furthermore, by treatment week 2, psyllium demonstrated an increase in the frequency of bowel movements, whereas docusate did not. It should be noted that this study was funded by Procter & Gamble, which manufactures Metamucil, a popular brand of psyllium.

Lastly, the most recent randomized controlled trial was published in 2013. It included 74 hospice patients in Canada, comparing docusate 200 mg and sennosides twice daily versus placebo and sennosides for 10 days. The study found no difference in stool frequency, volume, or consistency between docusate and placebo.17

A number of systematic reviews have studied the literature on bowel regimens and have noted the paucity of high-quality data supporting the efficacy of docusate, despite its widespread use.18-22 With these weak data, multiple authors have advocated for removing docusate from hospital formularies and using hospitalizations as an opportunity to deprescribe this medication to reduce polypharmacy. 3,4,23

Although docusate is considered a benign therapy, there is certainly potential for harm to the patient and detrimental effects on the healthcare system. Patients commonly complain about the unpleasant taste and lingering aftertaste, which may lead to decreased oral intake and worsening nutritional status.23 Furthermore, docusate may impact the absorption and effectiveness of other proven treatments.23 Perhaps the most important harm is that providers needlessly wait for docusate to fail before prescribing effective therapies for constipation. This process negatively impacts patient satisfaction and potentially increases healthcare costs if hospital length of stay is increased. Another important consideration is that patients may refuse truly necessary medications due to the excessive pill burden.

Costs to the healthcare system are increased needlessly when medications that do not improve outcomes are prescribed. Although the individual pill cost is low, the widespread use and the associated pharmacy and nursing resources required for administration create an estimated cost for docusate over $100,000,000 per year for North America alone.3 The staff time required for administration may prevent healthcare personnel from engaging in other more valuable tasks. Additionally, every medication order creates an opportunity for medical error. Lastly, bacteria were recently found contaminating the liquid formulation, which carries its own obvious implications if patients develop iatrogenic infections.24

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Instead of using docusate, prescribe agents with established efficacy. In 2006, a systematic review published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology graded the evidence behind different therapies for chronic constipation.21 They found good evidence (Grade A) to support the use of polyethylene glycol (PEG), while psyllium and lactulose had moderate evidence (Grade B) to support their use. All other currently available agents that were reviewed had poor evidence to support their use. A more recent study in people prescribed opioids similarly found evidence to support the use of polyethylene glycol, lactulose, and sennosides.25 Lastly, the 2016 guidelines from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons do not mention docusate, though they comment on the paucity of data on stool softeners. Their recommendations for laxative therapy are similar to those of the previously discussed reviews.26 Ultimately, the choice of therapy, pharmacological and nonpharmacological, should be individualized for each patient based on the clinical context and cause of constipation. Nonpharmacologic treatments include dietary modification, mobilization, chewing gum, and biofeedback. If pharmacotherapy is required, use laxatives with the strongest evidence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- In patients with constipation or at risk for constipation, use laxatives with proven efficacy (such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides) for treatment or prophylaxis of constipation instead of using docusate.

- Discuss de-prescription for patients using docusate prior to admission.

- Remove docusate from your hospital formulary.

CONCLUSION

Docusate is commonly used for the treatment and prevention of constipation in hospitalized patients, with significant associated costs. This common practice continues despite little evidence supporting its efficacy and many trials failing to show benefits over placebo. Decreased utilization of ineffective therapies such as docusate is recommended. Returning to the case presentation, the hospitalist should start the patient on alternative therapies, instead of docusate, such as polyethylene glycol, lactulose, psyllium, or sennosides, which have better evidence supporting their use.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosures

All authors deny any relevant conflict of interest with the attached manuscript.

1. Noiesen E, Trosborg I, Bager L, Herning M, Lyngby C, Konradsen H. Constipation--prevalence and incidence among medical patients acutely admitted to hospital with a medical condition. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2295-2302. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12511.

2. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, Eusebi LH, Bazzoli F, Chiarioni G. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3.

3. Lee TC, McDonald EG, Bonnici A, Tamblyn R. Pattern of inpatient laxative use: waste not, want not. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1216-1217. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2775.

4. MacMillan TE, Kamali R, Cavalcanti RB. Missed opportunity to deprescribe: docusate for constipation in medical inpatients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001 e1001-1007. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.04.008.

5. Spiesman MG, Malow L. New fecal softener (doxinate) in the treatment of constipation. J Lancet. 1956;76(6):164-167.

6. Harris R. Constipation in geriatrics; management with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate. Am J Dig Dis. Sep 1957;2(9):487-492.

7. Smigel JO, Lowe KJ, Hosp PH, Gibson JH. Constipation in elderly patients; treatment with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate plus peristim. Med Times. 1958;86(12):1521-1526.

8. Wilson JL, Dickinson DG. Use of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (aerosol O.T.) for severe constipation. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;158(4):261-263. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960040019006a.

9. Hyland CM, Foran JD. Dioctyl sodium sulphosuccinate as a laxative in the elderly. Practitioner. 1968;200(199):698-699.

10. Jin J. JAMA patient page. Over-the-counter laxatives. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2078.

11. 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015). 2015; http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/.

12. Goodman J, Pang J, Bessman AN. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate- an ineffective prophylactic laxative. J Chronic Dis. 1976;29(1):59-63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(76)90068-0.

13. Fain AM, Susat R, Herring M, Dorton K. Treatment of constipation in geriatric and chronically ill patients: a comparison. South Med J. 1978;71(6):677-680.

14. Chapman RW, Sillery J, Fontana DD, Matthys C, Saunders DR. Effect of oral dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate on intake-output studies of human small and large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1985;89(3):489-493. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90441-X.

15. Castle SC, Cantrell M, Israel DS, Samuelson MJ. Constipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questioned. Geriatrics. 1991;46(11):84-86.

16. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(5):491-497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00336.x.

17. Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(1):2-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.008.

18. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, Stone P. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD003448.

19. Hurdon V, Viola R, Schroder C. How useful is docusate in patients at risk for constipation? A systematic review of the evidence in the chronically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):130-136. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00157-8.

20. Pare P, Fedorak RN. Systematic review of stimulant and nonstimulant laxatives for the treatment of functional constipation. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(10):549-557.

21. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):936-971. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x

22. Health CAfDaTi. Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate (calcium or sodium) for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Ottawa (ON)2014.

23. McKee KY, Widera E. Habitual prescribing of laxatives-it’s time to flush outdated protocols down the drain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1217-1219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2780.

24. Marquez L, Jones KN, Whaley EM, et al. An outbreak of burkholderia cepacia complex infections associated with contaminated liquid docusate. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(5):567-573. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.11.

25. Ahmedzai SH, Boland J. Constipation in people prescribed opioids. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010.

26. Paquette IM, Varma M, Ternent C, et al. The American society of colon and rectal surgeons’ clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(6):479-492. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000599

1. Noiesen E, Trosborg I, Bager L, Herning M, Lyngby C, Konradsen H. Constipation--prevalence and incidence among medical patients acutely admitted to hospital with a medical condition. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2295-2302. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12511.

2. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, Eusebi LH, Bazzoli F, Chiarioni G. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3.

3. Lee TC, McDonald EG, Bonnici A, Tamblyn R. Pattern of inpatient laxative use: waste not, want not. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1216-1217. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2775.

4. MacMillan TE, Kamali R, Cavalcanti RB. Missed opportunity to deprescribe: docusate for constipation in medical inpatients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001 e1001-1007. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.04.008.

5. Spiesman MG, Malow L. New fecal softener (doxinate) in the treatment of constipation. J Lancet. 1956;76(6):164-167.

6. Harris R. Constipation in geriatrics; management with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate. Am J Dig Dis. Sep 1957;2(9):487-492.

7. Smigel JO, Lowe KJ, Hosp PH, Gibson JH. Constipation in elderly patients; treatment with dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate plus peristim. Med Times. 1958;86(12):1521-1526.

8. Wilson JL, Dickinson DG. Use of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (aerosol O.T.) for severe constipation. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;158(4):261-263. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960040019006a.

9. Hyland CM, Foran JD. Dioctyl sodium sulphosuccinate as a laxative in the elderly. Practitioner. 1968;200(199):698-699.

10. Jin J. JAMA patient page. Over-the-counter laxatives. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2078.

11. 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015). 2015; http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/.

12. Goodman J, Pang J, Bessman AN. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate- an ineffective prophylactic laxative. J Chronic Dis. 1976;29(1):59-63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(76)90068-0.

13. Fain AM, Susat R, Herring M, Dorton K. Treatment of constipation in geriatric and chronically ill patients: a comparison. South Med J. 1978;71(6):677-680.

14. Chapman RW, Sillery J, Fontana DD, Matthys C, Saunders DR. Effect of oral dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate on intake-output studies of human small and large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1985;89(3):489-493. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90441-X.

15. Castle SC, Cantrell M, Israel DS, Samuelson MJ. Constipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questioned. Geriatrics. 1991;46(11):84-86.

16. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(5):491-497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00336.x.

17. Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(1):2-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.008.

18. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, Stone P. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD003448.

19. Hurdon V, Viola R, Schroder C. How useful is docusate in patients at risk for constipation? A systematic review of the evidence in the chronically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):130-136. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00157-8.

20. Pare P, Fedorak RN. Systematic review of stimulant and nonstimulant laxatives for the treatment of functional constipation. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(10):549-557.

21. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):936-971. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x

22. Health CAfDaTi. Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate (calcium or sodium) for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Ottawa (ON)2014.

23. McKee KY, Widera E. Habitual prescribing of laxatives-it’s time to flush outdated protocols down the drain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1217-1219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2780.

24. Marquez L, Jones KN, Whaley EM, et al. An outbreak of burkholderia cepacia complex infections associated with contaminated liquid docusate. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(5):567-573. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.11.

25. Ahmedzai SH, Boland J. Constipation in people prescribed opioids. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010.

26. Paquette IM, Varma M, Ternent C, et al. The American society of colon and rectal surgeons’ clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(6):479-492. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000599

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Managing malignant pleural effusion

Managing patients with malignant pleural effusion can be challenging. Symptoms are often distressing, and its presence signifies advanced disease. Median survival after diagnosis is 4 to 9 months,1–3 although prognosis varies considerably depending on the type and stage of the malignancy.

How patients are best managed depends on clinical circumstances. Physicians should consider the risks and benefits of each option while keeping in mind realistic goals of care.

This article uses brief case presentations to review management strategies for malignant pleural effusion.

CANCER IS A COMMON CAUSE OF PLEURAL EFFUSION

Physicians and surgeons, especially in tertiary care hospitals, must often manage malignant pleural effusion.4 Malignancy is the third leading cause of pleural effusion after heart failure and pneumonia, accounting for 44% to 77% of exudates.5 Although pleural effusion can arise secondary to many different malignancies, the most common causes are lung cancer in men and breast cancer in women; these cancers account for about 75% of all cases of malignant pleural effusion.6,7

A WOMAN ON CHEMOTHERAPY WITH ASYMPTOMATIC PLEURAL EFFUSION

An 18-year-old woman with non-Hodgkin lymphoma has received her first cycle of chemotherapy and is now admitted to the hospital for diarrhea. A routine chest radiograph reveals a left-sided pleural effusion covering one-third of the thoracic cavity. She is asymptomatic and reports no shortness of breath at rest or with exertion. Her oxygen saturation level is above 92% on room air without supplemental oxygen.

Thoracentesis reveals an exudative effusion, and cytologic study shows malignant lymphoid cells, consistent with a malignant pleural effusion. Cultures are negative.

What is the appropriate next step to manage this patient’s effusion?

Observation is reasonable

This patient is experiencing no symptoms and has just begun chemotherapy for her lymphoma. Malignant pleural effusion associated with lymphoma, small-cell lung cancer, and breast cancer is most sensitive to chemotherapy.5 For patients who do not have symptoms from the pleural effusion and who are scheduled to receive further chemotherapy, a watch-and-wait approach is reasonable.

It is important to follow the patient for developing symptoms and obtain serial imaging to evaluate for an increase in the effusion size. We recommend repeat imaging at 2- to 4-week intervals, and sooner if symptoms develop.

If progression is evident or if the patient’s oncologist indicates that the cancer is unresponsive to systemic therapy, further intervention may be necessary with one of the options discussed below.

A MAN WITH LUNG CANCER WITH PLEURAL EFFUSION, LUNG COLLAPSE

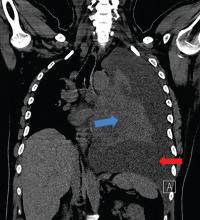

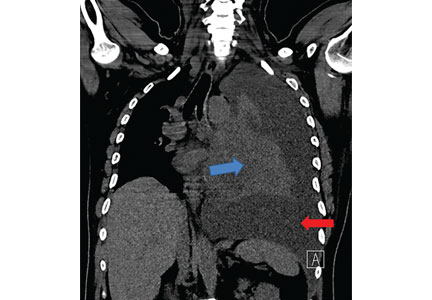

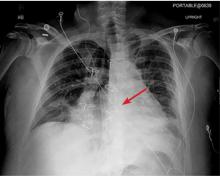

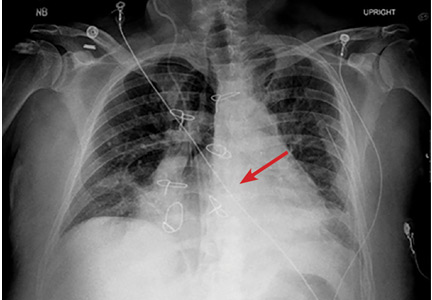

A 42-year-old man with a history of lung cancer is admitted for worsening shortness of breath. Chest radiography reveals a large left-sided pleural effusion with complete collapse of the left lung and contralateral shift of midline structures (Figure 1). Large-volume thoracentesis improves his symptoms. Pleural fluid cytology is positive for malignant cells. A repeat chest radiograph shows incomplete expansion of the left lung, thick pleura, and pneumothorax, indicating a trapped lung (ie, one unable to expand fully). Two weeks later, his symptoms recur, and chest radiography reveals a recurrent effusion.

How should this effusion be managed?

Indwelling pleural catheter placement

In a retrospective cohort study,8 malignant pleural effusion recurred in 97% of patients within 1 month (mean, 4.2 days) of therapeutic aspiration, highlighting the need for definitive treatment.

In the absence of lung expansion, pleurodesis is rarely successful, and placing an indwelling pleural catheter in symptomatic patients is the preferred strategy. The US Food and Drug Administration approved this use in 1997.9

Indwelling pleural catheters are narrow (15.5 French, or about 5 mm in diameter) and soft (made of silicone), with distal fenestrations. The distal end remains positioned in the pleural cavity to enable drainage of pleural fluid. The middle portion passes through subcutaneous tissue, where a polyester cuff prevents dislodgement and infection. The proximal end of the catheter remains outside the patient’s skin and is connected to a 1-way valve that prevents air or fluid flow into the pleural cavity.

Pleural fluid is typically drained every 2 or 3 days for palliation. Patients must be educated about home drainage and proper catheter care.

Indwelling pleural catheters are now initial therapy for many

Although indwelling pleural catheters were first used for patients who were not candidates for pleurodesis, they are now increasingly used as first-line therapy.

Since these devices were introduced, several clinical series including more than 800 patients have found that their use for malignant pleural infusion led to symptomatic improvement in 89% to 100% of cases, with 90% of patients needing no subsequent pleural procedures after catheter insertion.10–13

Davies et al14 randomized 106 patients with malignant pleural effusion to either receive an indwelling pleural catheter or undergo pleurodesis. In the first 6 weeks, the 2 groups had about the same incidence of dyspnea, but the catheter group had less dyspnea at 6 months, shorter index hospitalization (0 vs 4 days), fewer hospital days in the first year for treatment-related complications (1 vs 4.5 days), and fewer patients needing follow-up pleural procedures (6% vs 22%). On the other hand, adverse events were more frequent in the indwelling pleural catheter group (40% vs 13%). The most frequent events were pleural infection, cellulitis, and catheter blockage.

Fysh et al15 also compared indwelling pleural catheter insertion and pleurodesis (based on patient choice) in patients with malignant pleural effusion. As in the previous trial, those who received a catheter required significantly fewer days in the hospital and fewer additional pleural procedures than those who received pleurodesis. Safety profiles and symptom control were comparable.

Indwelling pleural catheters have several other advantages. They have been found to be more cost-effective than talc pleurodesis in patients not expected to live long (survival < 14 weeks).16 Patients with an indwelling pleural catheter can receive chemotherapy, and concurrent treatment does not increase risk of infection.17 And a systematic review18 found a 46% rate of autopleurodesis at a median of 52 days after insertion of an indwelling pleural catheter.

Drainage rate may need to be moderated

Chest pain has been reported with the use of indwelling pleural catheters, related to rapid drainage of the effusion in the setting of failed reexpansion of the trapped lung due to thickened pleura. Drainage schedules may need to be adjusted, with more frequent draining of smaller volumes, to control dyspnea without causing significant pain.

A WOMAN WITH RECURRENT PLEURAL EFFUSION, GOOD PROGNOSIS

A 55-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer presents with shortness of breath. Chest radiography reveals a right-sided effusion, which on thoracentesis is found to be malignant. After fluid removal, repeat chest radiography shows complete lung expansion.

One month later, she returns with symptoms and recurrence of the effusion. Ultrasonography does not reveal any adhesions in the pleural space. Her oncologist informs you that her expected survival is in years.

What is the next step?

Chemical pleurodesis

Chemical pleurodesis involves introducing a sclerosant into the pleural space to provoke an intense inflammatory response, creating adhesions and fibrosis that will obliterate the space. The sclerosing agent (typically talc) can be delivered by tube thoracostomy, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), or medical pleuroscopy. Although the latter 2 methods allow direct visualization of the pleural space and, in theory, a more even distribution of the sclerosing agent, current evidence does not favor 1 option over the other,19 and practice patterns vary between institutions.

Tube thoracostomy. Typically, the sclerosing agent is administered once a chest radiograph shows lung reexpansion, and tube output of pleural fluid is less than 150 mL/day.19 However, some studies indicate that if pleural apposition can be confirmed using ultrasonography, then sclerosant administration at that time leads to optimal pleurodesis efficacy and shorter hospitalization.20,21

VATS is usually done in the operating room with the patient under general anesthesia. A double-lumen endotracheal tube allows for single-lung ventilation; a camera is then inserted into the pleural space of the collapsed lung. Multiple ports of entry are usually employed, and the entire pleural space can be visualized and the sclerosing agent instilled uniformly. The surgeon may alternatively choose to perform mechanical pleurodesis, which entails abrading the visceral and parietal pleura with dry gauze to provoke diffuse petechial hemorrhage and an inflammatory reaction. VATS can also be used to perform biopsy, lobectomy, and pneumonectomy.

Medical pleuroscopy. Medical pleuroscopy is usually done using local anesthesia with the patient awake, moderately sedated, and not intubated. Because no double-lumen endotracheal tube is used, lung collapse may not be complete, making it difficult to completely visualize the entire pleural surfaces.

Although no randomized study of VATS vs medical pleuroscopy exists, a retrospective case-matched study22 comparing VATS (under general anesthesia) to single-port VATS (under local anesthesia) noted equivalent rates of pleurodesis. However, the local anesthesia group had a lower perioperative mortality rate (0% vs 2.3%), a lower postoperative major morbidity rate (5.2% vs 9%), earlier improvement in quality of life, and shorter hospitalization (3 vs 5 days).22 In general, the diagnostic sensitivity of pleuroscopy for pleural malignancy is similar to that of VATS (93% vs 97%).23,24

A MAN WITH PLEURAL EFFUSION AND A POOR PROGNOSIS

A 60-year-old man with metastatic pancreatic cancer is brought to the clinic for worsening shortness of breath over the past 2 months. During that time, he has lost 6 kg and has become bedridden.

On examination, he has severe cachexia and is significantly short of breath at rest with associated hypoxia. His oncologist expects him to survive less than 3 months.

His laboratory investigations reveal hypoalbuminemia and leukocytosis. A chest radiograph shows a large left-sided pleural effusion that was not present 2 months ago.

What should be done for him?

Thoracentesis, repeat as needed

Malignant pleural effusion causing dyspnea is not uncommon in certain advanced malignancies and may contribute to significant suffering at the end of life. A study of 298 patients with malignant pleural effusion noted that the presence of leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and hypoxemia was associated with a poorer prognosis. Patients having all 3 factors had a median survival of 42 days.25

Thoracentesis, the least invasive option that may improve dyspnea, can be done in the clinic setting and is a reasonable strategy for patients with advanced cancer and an expected survival of less than 3 months.26 Although recurrence is expected, it may take up to a few weeks, and repeat thoracentesis can be performed as needed.

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.136994

- Ruckdeschel JC. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Semin Oncol 1995; 22(2 suppl 3):58–63. pmid:7740322

- Bielsa S, Martín-Juan J, Porcel JM, Rodríguez-Panadero F. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of pleural adhesions in malignant effusions. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3(11):1251–1256. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318189f53d

- 35th Annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Brussels, Belgium, 28 September–2 October, 1999. Abstracts. Diabetologia 1999;42(suppl 1):A1–A354. pmid:10505080

- Antony VB, Loddenkemper R, Astoul P, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J 2001; 18(2):402–419. pmid:11529302

- Sahn SA. Malignancy metastatic to the pleura. Clin Chest Med 1998; 19(2):351–361. pmid:9646986

- Sahn SA. Pleural diseases related to metastatic malignancies. Eur Respir J 1997; 10(8):1907–1913. pmid:9272937

- Anderson CB, Philpott GW, Ferguson TB. The treatment of malignant pleural effusions. Cancer 1974; 33(4):916–922. pmid:4362107

- Uzbeck MH, Almeida FA, Sarkiss MG, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Adv Ther 2010; 27(6):334–347. doi:10.1007/S12325-010-0031-8

- Suzuki K, Servais EL, Rizk NP, et al. Palliation and pleurodesis in malignant pleural effusion: the role for tunneled pleural catheters. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6(4):762–767. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820d614f

- Tremblay A, Michaud G. Single-center experience with 250 tunnelled pleural catheter insertions for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2006; 129(2):362–368. doi:10.1378/chest.129.2.362

- Warren WH, Kalimi R, Khodadadian LM, Kim AW. Management of malignant pleural effusions using the Pleur(x) catheter. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85(3):1049–1055 doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.039

- Murthy SC, Okereke I, Mason DP, Rice TW. A simple solution for complicated pleural effusions. J Thorac Oncol 2006; 1(7):697–700. pmid:17409939

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307(22):2383–2389. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5535

- Fysh ETH, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142(2):394–400. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2657

- Olfert JA, Penz ED, Manns BJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of indwelling pleural catheter compared with talc in malignant pleural effusion. Respirology 2017; 22(4):764–770. doi:10.1111/resp.12962

- Morel A, Mishra E, Medley L, et al. Chemotherapy should not be withheld from patients with an indwelling pleural catheter for malignant pleural effusion. Thorax 2011; 66(5):448–449. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.133504

- Van Meter MEM, McKee KY, Kohlwes RJ. Efficacy and safety of tunneled pleural catheters in adults with malignant pleural effusions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26(1):70–76. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1472-0

- Lee YCG, Baumann MH, Maskell NA, et al. Pleurodesis practice for malignant pleural effusions in five English-speaking countries. Chest 2003; 124(6):2229–2238. pmid:14665505

- Villanueva AG, Gray AW Jr, Shahian DM, Williamson WA, Beamis JF Jr. Efficacy of short term versus long term tube thoracostomy drainage before tetracycline pleurodesis in the treatment of malignant pleural effusions. Thorax 1994; 49(1):23–25. pmid:7512285

- Sartori S, Tombesi P, Tassinari D, et al. Sonographically guided small-bore chest tubes and sonographic monitoring for rapid sclerotherapy of recurrent malignant pleural effusions. J Ultrasound Med 2004; 23(9):1171–1176. pmid:15328431

- Mineo TC, Sellitri F, Tacconi F, Ambrogi V. Quality of life and outcomes after nonintubated versus intubated video-thoracoscopic pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion: comparison by a case-matched study. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(7):761–768. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0617

- Michaud G, Berkowitz DM, Ernst A. Pleuroscopy for diagnosis and therapy for pleural effusions. Chest 2010; 138(5):1242–1246. doi:10.1378/chest.10-1259

- Bhatnagar R, Maskell NA. Medical pleuroscopy. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34(3):487–500. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2013.04.001

- Pilling JE, Dusmet ME, Ladas G, Goldstraw P. Prognostic factors for survival after surgical palliation of malignant pleural effusion. J Thorac Oncol 2010; 5(10):1544–1550. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e95cb8

- Beyea A, Winzelberg G, Stafford RE. To drain or not to drain: an evidence-based approach to palliative procedures for the management of malignant pleural effusions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 44(2):301–306. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.002

Managing patients with malignant pleural effusion can be challenging. Symptoms are often distressing, and its presence signifies advanced disease. Median survival after diagnosis is 4 to 9 months,1–3 although prognosis varies considerably depending on the type and stage of the malignancy.

How patients are best managed depends on clinical circumstances. Physicians should consider the risks and benefits of each option while keeping in mind realistic goals of care.

This article uses brief case presentations to review management strategies for malignant pleural effusion.

CANCER IS A COMMON CAUSE OF PLEURAL EFFUSION

Physicians and surgeons, especially in tertiary care hospitals, must often manage malignant pleural effusion.4 Malignancy is the third leading cause of pleural effusion after heart failure and pneumonia, accounting for 44% to 77% of exudates.5 Although pleural effusion can arise secondary to many different malignancies, the most common causes are lung cancer in men and breast cancer in women; these cancers account for about 75% of all cases of malignant pleural effusion.6,7

A WOMAN ON CHEMOTHERAPY WITH ASYMPTOMATIC PLEURAL EFFUSION

An 18-year-old woman with non-Hodgkin lymphoma has received her first cycle of chemotherapy and is now admitted to the hospital for diarrhea. A routine chest radiograph reveals a left-sided pleural effusion covering one-third of the thoracic cavity. She is asymptomatic and reports no shortness of breath at rest or with exertion. Her oxygen saturation level is above 92% on room air without supplemental oxygen.

Thoracentesis reveals an exudative effusion, and cytologic study shows malignant lymphoid cells, consistent with a malignant pleural effusion. Cultures are negative.

What is the appropriate next step to manage this patient’s effusion?

Observation is reasonable

This patient is experiencing no symptoms and has just begun chemotherapy for her lymphoma. Malignant pleural effusion associated with lymphoma, small-cell lung cancer, and breast cancer is most sensitive to chemotherapy.5 For patients who do not have symptoms from the pleural effusion and who are scheduled to receive further chemotherapy, a watch-and-wait approach is reasonable.

It is important to follow the patient for developing symptoms and obtain serial imaging to evaluate for an increase in the effusion size. We recommend repeat imaging at 2- to 4-week intervals, and sooner if symptoms develop.

If progression is evident or if the patient’s oncologist indicates that the cancer is unresponsive to systemic therapy, further intervention may be necessary with one of the options discussed below.

A MAN WITH LUNG CANCER WITH PLEURAL EFFUSION, LUNG COLLAPSE

A 42-year-old man with a history of lung cancer is admitted for worsening shortness of breath. Chest radiography reveals a large left-sided pleural effusion with complete collapse of the left lung and contralateral shift of midline structures (Figure 1). Large-volume thoracentesis improves his symptoms. Pleural fluid cytology is positive for malignant cells. A repeat chest radiograph shows incomplete expansion of the left lung, thick pleura, and pneumothorax, indicating a trapped lung (ie, one unable to expand fully). Two weeks later, his symptoms recur, and chest radiography reveals a recurrent effusion.

How should this effusion be managed?

Indwelling pleural catheter placement

In a retrospective cohort study,8 malignant pleural effusion recurred in 97% of patients within 1 month (mean, 4.2 days) of therapeutic aspiration, highlighting the need for definitive treatment.

In the absence of lung expansion, pleurodesis is rarely successful, and placing an indwelling pleural catheter in symptomatic patients is the preferred strategy. The US Food and Drug Administration approved this use in 1997.9

Indwelling pleural catheters are narrow (15.5 French, or about 5 mm in diameter) and soft (made of silicone), with distal fenestrations. The distal end remains positioned in the pleural cavity to enable drainage of pleural fluid. The middle portion passes through subcutaneous tissue, where a polyester cuff prevents dislodgement and infection. The proximal end of the catheter remains outside the patient’s skin and is connected to a 1-way valve that prevents air or fluid flow into the pleural cavity.

Pleural fluid is typically drained every 2 or 3 days for palliation. Patients must be educated about home drainage and proper catheter care.

Indwelling pleural catheters are now initial therapy for many

Although indwelling pleural catheters were first used for patients who were not candidates for pleurodesis, they are now increasingly used as first-line therapy.

Since these devices were introduced, several clinical series including more than 800 patients have found that their use for malignant pleural infusion led to symptomatic improvement in 89% to 100% of cases, with 90% of patients needing no subsequent pleural procedures after catheter insertion.10–13

Davies et al14 randomized 106 patients with malignant pleural effusion to either receive an indwelling pleural catheter or undergo pleurodesis. In the first 6 weeks, the 2 groups had about the same incidence of dyspnea, but the catheter group had less dyspnea at 6 months, shorter index hospitalization (0 vs 4 days), fewer hospital days in the first year for treatment-related complications (1 vs 4.5 days), and fewer patients needing follow-up pleural procedures (6% vs 22%). On the other hand, adverse events were more frequent in the indwelling pleural catheter group (40% vs 13%). The most frequent events were pleural infection, cellulitis, and catheter blockage.

Fysh et al15 also compared indwelling pleural catheter insertion and pleurodesis (based on patient choice) in patients with malignant pleural effusion. As in the previous trial, those who received a catheter required significantly fewer days in the hospital and fewer additional pleural procedures than those who received pleurodesis. Safety profiles and symptom control were comparable.

Indwelling pleural catheters have several other advantages. They have been found to be more cost-effective than talc pleurodesis in patients not expected to live long (survival < 14 weeks).16 Patients with an indwelling pleural catheter can receive chemotherapy, and concurrent treatment does not increase risk of infection.17 And a systematic review18 found a 46% rate of autopleurodesis at a median of 52 days after insertion of an indwelling pleural catheter.

Drainage rate may need to be moderated

Chest pain has been reported with the use of indwelling pleural catheters, related to rapid drainage of the effusion in the setting of failed reexpansion of the trapped lung due to thickened pleura. Drainage schedules may need to be adjusted, with more frequent draining of smaller volumes, to control dyspnea without causing significant pain.

A WOMAN WITH RECURRENT PLEURAL EFFUSION, GOOD PROGNOSIS

A 55-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer presents with shortness of breath. Chest radiography reveals a right-sided effusion, which on thoracentesis is found to be malignant. After fluid removal, repeat chest radiography shows complete lung expansion.

One month later, she returns with symptoms and recurrence of the effusion. Ultrasonography does not reveal any adhesions in the pleural space. Her oncologist informs you that her expected survival is in years.

What is the next step?

Chemical pleurodesis

Chemical pleurodesis involves introducing a sclerosant into the pleural space to provoke an intense inflammatory response, creating adhesions and fibrosis that will obliterate the space. The sclerosing agent (typically talc) can be delivered by tube thoracostomy, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), or medical pleuroscopy. Although the latter 2 methods allow direct visualization of the pleural space and, in theory, a more even distribution of the sclerosing agent, current evidence does not favor 1 option over the other,19 and practice patterns vary between institutions.

Tube thoracostomy. Typically, the sclerosing agent is administered once a chest radiograph shows lung reexpansion, and tube output of pleural fluid is less than 150 mL/day.19 However, some studies indicate that if pleural apposition can be confirmed using ultrasonography, then sclerosant administration at that time leads to optimal pleurodesis efficacy and shorter hospitalization.20,21

VATS is usually done in the operating room with the patient under general anesthesia. A double-lumen endotracheal tube allows for single-lung ventilation; a camera is then inserted into the pleural space of the collapsed lung. Multiple ports of entry are usually employed, and the entire pleural space can be visualized and the sclerosing agent instilled uniformly. The surgeon may alternatively choose to perform mechanical pleurodesis, which entails abrading the visceral and parietal pleura with dry gauze to provoke diffuse petechial hemorrhage and an inflammatory reaction. VATS can also be used to perform biopsy, lobectomy, and pneumonectomy.

Medical pleuroscopy. Medical pleuroscopy is usually done using local anesthesia with the patient awake, moderately sedated, and not intubated. Because no double-lumen endotracheal tube is used, lung collapse may not be complete, making it difficult to completely visualize the entire pleural surfaces.