User login

Perioperative medicine: Combining the science and the art

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine,1 Dr. Steven L. Cohn provides a succinct review of the recently published guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.2 Although no drastic changes have been made in these guidelines, several significant modifications have been implemented and are highlighted in his review.

A BREACH OF SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY

First, I am pleased Dr. Cohn described how the writing committee of the new guidelines handled the well-publicized breaches of scientific integrity by Dr. Don Poldermans, a prolific perioperative-medicine researcher at Erasmus University in the Netherlands who has contributed an abundance of literature that influenced clinical practice. Although some of his key publications were excluded by the ACC/AHA committee in its overall analysis, it remains unclear to me if simply ignoring some of his work is truly possible. For better or for worse, his publications have significantly shaped clinical practice in addition to guiding subsequent research in this field.

ASSESSING RISK

Along with continuing to endorse the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI),3 the guidelines now include another option for objective preoperative cardiovascular risk assessment. Dr. Cohn nicely outlines the pros and cons of the surgical risk calculator (often referred to as the “Gupta calculator”) derived from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database.4

Although the RCRI is not perfect, I agree with Dr. Cohn that the ACS NSQIP tool has limitations, including a cumbersome calculation (requiring a smartphone application or online calculator), lack of external validation, and use of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System, which has been notoriously confusing for generalists and has demonstrated poor inter-rater reliability among anesthesiologists.5,6

Of note, a patient may have very different risk-prediction scores depending on which tool is used. For example, a 66-year-old man with a history of ischemic heart disease, diabetes on insulin therapy, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with a serum creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dL who is scheduled to undergo total hip arthroplasty would have a risk of a perioperative cardiovascular event of about 10% according to the RCRI, but only 1.1% according to the ACS NSQIP calculator. How widely this newer risk-stratification tool will be adopted in clinical practice will be interesting to observe.

In what appears to be an effort to simplify the guidelines, the ACC/AHA now recommends combining the patient’s clinical and surgical risks into estimating an overall perioperative risk for developing major adverse cardiac events. This estimate is now whittled down to only two categories: “low risk” and “elevated risk.” I am concerned that the new guidelines may have become too streamlined and lack the direction to assist providers in making important clinical decisions. Most notably, and as Dr. Cohn appropriately suggests, many patients will be in a gray zone with respect to whether cardiac stress testing should be obtained before surgery.

STRESS TESTING

Significant background knowledge is required to answer the important question in the ACC/AHA algorithm, ie, whether further testing will have an impact on decision-making or perioperative care.2 Dr. Cohn provides some of this information by noting the abysmal positive predictive value of preoperative noninvasive cardiac testing (with studies ranging from 0% to 37%) and by correctly stating that no benefit has been observed with preoperative cardiac revascularization.

If this is not widely known, I share Dr. Cohn’s fear that the new guidelines may stimulate increased ordering of preoperative stress tests. We observed this trend with the highly scripted 2002 ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines7 and subsequently learned that stress testing before surgery very seldom changes patient management.

A preoperative stress test should be reserved for patients with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. As a diagnostic study, the value of stress testing is excellent. This is not true when it is used as a screening test for asymptomatic patients, where its ability to predict perioperative cardiovascular events is extremely poor. The only other indication for preoperative stress testing is the rare occasion when further risk stratification is desired for exceptionally high-risk patients. In this scenario, test results may influence the decision to proceed with surgery vs seeking nonoperative approaches or palliative care.

MANAGING MEDICATIONS

Dr. Cohn discusses pertinent issues in the perioperative management of patients’ medications, an important component of the preoperative evaluation.

Despite the inconsistent clinical trial results on perioperative beta-blockers, his assessment of their risks and benefits is clinically accurate and practical. Furthermore, I fully agree with Dr. Cohn’s thoughtful approach regarding perioperative statins, despite the limited data available from randomized controlled trials.

With respect to perioperative aspirin use, I have concerns with Dr. Cohn’s statement that it may be reasonable to continue aspirin perioperatively if the risk of potential cardiac events outweighs the risk of bleeding. Given the result of the recently published second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE-2) trial8 that showed a significantly higher risk of major perioperative bleeding in patients randomized to low-dose aspirin, it is difficult to advocate continuing aspirin when no cardiovascular protection was found in this very large trial. I agree with Dr. Cohn that this applies only to patients with no history of coronary artery stent placement, as patients with a stent should remain on low-dose aspirin throughout the entire perioperative period.

Controversy also surrounds angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Dr. Cohn agrees with the ACC/AHA guidelines to continue these agents before surgery; however, I favor holding them on the day of surgery. Although the risk of hypotension-induced cardiac events has not been clearly demonstrated, a recent retrospective study involving more than 1,100 patients showed significantly more acute kidney injury (even after adjusting for hypotension) as well as an increased length of hospital stay in the patients exposed to these agents before surgery.9 Given these findings, in addition to the postinduction hypotension (which can be profound) commonly observed by our anesthesiology colleagues, I recommend holding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the day of surgery, with very few exceptions.

THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MEDICINE

Dr. Cohn acknowledges that we lack scientific data to answer many questions that arise when caring for the perioperative patient and thus we rely on the ACC/AHA guidelines to provide a framework. These scientific knowledge gaps emphasize the importance of the art of medicine in the perioperative arena. Although we may desire “cookbook” guidelines, the significant gaps in the perioperative medicine evidence base reinforce the necessity to provide individual patient-level care in a multidisciplinary environment with our surgery and anesthesiology colleagues. Without the proper balance of science and art in perioperative medicine, we sacrifice our ability to deliver optimal care for this high-risk patient population.

- Cohn SL. Updated guidelines on cardiovascular evaluation before noncardiac surgery: a view from the trenches. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:742–751.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. pii: S0735-1097(14)05536-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print].

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation 2011; 124:381–387.

- Aronson WL, McAuliffe MS, Miller K. Variability in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification Scale. AANA J 2003; 71:265–274.

- Mak PH, Campbell RC, Irwin MG; American Society of Anesthesiologists. The ASA Physical Status Classification: inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anaesth Intensive Care 2002; 30:633–640.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1494–1503.

- Nielson E, Hennrikus E, Lehman E, Mets B. Angiotensin axis blockade, hypotension, and acute kidney injury in elective major orthopedic surgery. J Hosp Med 2014; 9:283–288.

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine,1 Dr. Steven L. Cohn provides a succinct review of the recently published guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.2 Although no drastic changes have been made in these guidelines, several significant modifications have been implemented and are highlighted in his review.

A BREACH OF SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY

First, I am pleased Dr. Cohn described how the writing committee of the new guidelines handled the well-publicized breaches of scientific integrity by Dr. Don Poldermans, a prolific perioperative-medicine researcher at Erasmus University in the Netherlands who has contributed an abundance of literature that influenced clinical practice. Although some of his key publications were excluded by the ACC/AHA committee in its overall analysis, it remains unclear to me if simply ignoring some of his work is truly possible. For better or for worse, his publications have significantly shaped clinical practice in addition to guiding subsequent research in this field.

ASSESSING RISK

Along with continuing to endorse the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI),3 the guidelines now include another option for objective preoperative cardiovascular risk assessment. Dr. Cohn nicely outlines the pros and cons of the surgical risk calculator (often referred to as the “Gupta calculator”) derived from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database.4

Although the RCRI is not perfect, I agree with Dr. Cohn that the ACS NSQIP tool has limitations, including a cumbersome calculation (requiring a smartphone application or online calculator), lack of external validation, and use of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System, which has been notoriously confusing for generalists and has demonstrated poor inter-rater reliability among anesthesiologists.5,6

Of note, a patient may have very different risk-prediction scores depending on which tool is used. For example, a 66-year-old man with a history of ischemic heart disease, diabetes on insulin therapy, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with a serum creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dL who is scheduled to undergo total hip arthroplasty would have a risk of a perioperative cardiovascular event of about 10% according to the RCRI, but only 1.1% according to the ACS NSQIP calculator. How widely this newer risk-stratification tool will be adopted in clinical practice will be interesting to observe.

In what appears to be an effort to simplify the guidelines, the ACC/AHA now recommends combining the patient’s clinical and surgical risks into estimating an overall perioperative risk for developing major adverse cardiac events. This estimate is now whittled down to only two categories: “low risk” and “elevated risk.” I am concerned that the new guidelines may have become too streamlined and lack the direction to assist providers in making important clinical decisions. Most notably, and as Dr. Cohn appropriately suggests, many patients will be in a gray zone with respect to whether cardiac stress testing should be obtained before surgery.

STRESS TESTING

Significant background knowledge is required to answer the important question in the ACC/AHA algorithm, ie, whether further testing will have an impact on decision-making or perioperative care.2 Dr. Cohn provides some of this information by noting the abysmal positive predictive value of preoperative noninvasive cardiac testing (with studies ranging from 0% to 37%) and by correctly stating that no benefit has been observed with preoperative cardiac revascularization.

If this is not widely known, I share Dr. Cohn’s fear that the new guidelines may stimulate increased ordering of preoperative stress tests. We observed this trend with the highly scripted 2002 ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines7 and subsequently learned that stress testing before surgery very seldom changes patient management.

A preoperative stress test should be reserved for patients with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. As a diagnostic study, the value of stress testing is excellent. This is not true when it is used as a screening test for asymptomatic patients, where its ability to predict perioperative cardiovascular events is extremely poor. The only other indication for preoperative stress testing is the rare occasion when further risk stratification is desired for exceptionally high-risk patients. In this scenario, test results may influence the decision to proceed with surgery vs seeking nonoperative approaches or palliative care.

MANAGING MEDICATIONS

Dr. Cohn discusses pertinent issues in the perioperative management of patients’ medications, an important component of the preoperative evaluation.

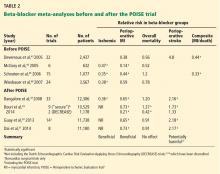

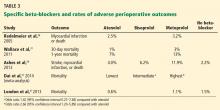

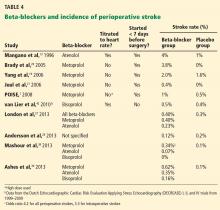

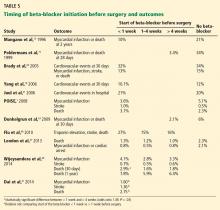

Despite the inconsistent clinical trial results on perioperative beta-blockers, his assessment of their risks and benefits is clinically accurate and practical. Furthermore, I fully agree with Dr. Cohn’s thoughtful approach regarding perioperative statins, despite the limited data available from randomized controlled trials.

With respect to perioperative aspirin use, I have concerns with Dr. Cohn’s statement that it may be reasonable to continue aspirin perioperatively if the risk of potential cardiac events outweighs the risk of bleeding. Given the result of the recently published second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE-2) trial8 that showed a significantly higher risk of major perioperative bleeding in patients randomized to low-dose aspirin, it is difficult to advocate continuing aspirin when no cardiovascular protection was found in this very large trial. I agree with Dr. Cohn that this applies only to patients with no history of coronary artery stent placement, as patients with a stent should remain on low-dose aspirin throughout the entire perioperative period.

Controversy also surrounds angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Dr. Cohn agrees with the ACC/AHA guidelines to continue these agents before surgery; however, I favor holding them on the day of surgery. Although the risk of hypotension-induced cardiac events has not been clearly demonstrated, a recent retrospective study involving more than 1,100 patients showed significantly more acute kidney injury (even after adjusting for hypotension) as well as an increased length of hospital stay in the patients exposed to these agents before surgery.9 Given these findings, in addition to the postinduction hypotension (which can be profound) commonly observed by our anesthesiology colleagues, I recommend holding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the day of surgery, with very few exceptions.

THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MEDICINE

Dr. Cohn acknowledges that we lack scientific data to answer many questions that arise when caring for the perioperative patient and thus we rely on the ACC/AHA guidelines to provide a framework. These scientific knowledge gaps emphasize the importance of the art of medicine in the perioperative arena. Although we may desire “cookbook” guidelines, the significant gaps in the perioperative medicine evidence base reinforce the necessity to provide individual patient-level care in a multidisciplinary environment with our surgery and anesthesiology colleagues. Without the proper balance of science and art in perioperative medicine, we sacrifice our ability to deliver optimal care for this high-risk patient population.

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine,1 Dr. Steven L. Cohn provides a succinct review of the recently published guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.2 Although no drastic changes have been made in these guidelines, several significant modifications have been implemented and are highlighted in his review.

A BREACH OF SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY

First, I am pleased Dr. Cohn described how the writing committee of the new guidelines handled the well-publicized breaches of scientific integrity by Dr. Don Poldermans, a prolific perioperative-medicine researcher at Erasmus University in the Netherlands who has contributed an abundance of literature that influenced clinical practice. Although some of his key publications were excluded by the ACC/AHA committee in its overall analysis, it remains unclear to me if simply ignoring some of his work is truly possible. For better or for worse, his publications have significantly shaped clinical practice in addition to guiding subsequent research in this field.

ASSESSING RISK

Along with continuing to endorse the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI),3 the guidelines now include another option for objective preoperative cardiovascular risk assessment. Dr. Cohn nicely outlines the pros and cons of the surgical risk calculator (often referred to as the “Gupta calculator”) derived from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database.4

Although the RCRI is not perfect, I agree with Dr. Cohn that the ACS NSQIP tool has limitations, including a cumbersome calculation (requiring a smartphone application or online calculator), lack of external validation, and use of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System, which has been notoriously confusing for generalists and has demonstrated poor inter-rater reliability among anesthesiologists.5,6

Of note, a patient may have very different risk-prediction scores depending on which tool is used. For example, a 66-year-old man with a history of ischemic heart disease, diabetes on insulin therapy, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with a serum creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dL who is scheduled to undergo total hip arthroplasty would have a risk of a perioperative cardiovascular event of about 10% according to the RCRI, but only 1.1% according to the ACS NSQIP calculator. How widely this newer risk-stratification tool will be adopted in clinical practice will be interesting to observe.

In what appears to be an effort to simplify the guidelines, the ACC/AHA now recommends combining the patient’s clinical and surgical risks into estimating an overall perioperative risk for developing major adverse cardiac events. This estimate is now whittled down to only two categories: “low risk” and “elevated risk.” I am concerned that the new guidelines may have become too streamlined and lack the direction to assist providers in making important clinical decisions. Most notably, and as Dr. Cohn appropriately suggests, many patients will be in a gray zone with respect to whether cardiac stress testing should be obtained before surgery.

STRESS TESTING

Significant background knowledge is required to answer the important question in the ACC/AHA algorithm, ie, whether further testing will have an impact on decision-making or perioperative care.2 Dr. Cohn provides some of this information by noting the abysmal positive predictive value of preoperative noninvasive cardiac testing (with studies ranging from 0% to 37%) and by correctly stating that no benefit has been observed with preoperative cardiac revascularization.

If this is not widely known, I share Dr. Cohn’s fear that the new guidelines may stimulate increased ordering of preoperative stress tests. We observed this trend with the highly scripted 2002 ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines7 and subsequently learned that stress testing before surgery very seldom changes patient management.

A preoperative stress test should be reserved for patients with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. As a diagnostic study, the value of stress testing is excellent. This is not true when it is used as a screening test for asymptomatic patients, where its ability to predict perioperative cardiovascular events is extremely poor. The only other indication for preoperative stress testing is the rare occasion when further risk stratification is desired for exceptionally high-risk patients. In this scenario, test results may influence the decision to proceed with surgery vs seeking nonoperative approaches or palliative care.

MANAGING MEDICATIONS

Dr. Cohn discusses pertinent issues in the perioperative management of patients’ medications, an important component of the preoperative evaluation.

Despite the inconsistent clinical trial results on perioperative beta-blockers, his assessment of their risks and benefits is clinically accurate and practical. Furthermore, I fully agree with Dr. Cohn’s thoughtful approach regarding perioperative statins, despite the limited data available from randomized controlled trials.

With respect to perioperative aspirin use, I have concerns with Dr. Cohn’s statement that it may be reasonable to continue aspirin perioperatively if the risk of potential cardiac events outweighs the risk of bleeding. Given the result of the recently published second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE-2) trial8 that showed a significantly higher risk of major perioperative bleeding in patients randomized to low-dose aspirin, it is difficult to advocate continuing aspirin when no cardiovascular protection was found in this very large trial. I agree with Dr. Cohn that this applies only to patients with no history of coronary artery stent placement, as patients with a stent should remain on low-dose aspirin throughout the entire perioperative period.

Controversy also surrounds angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Dr. Cohn agrees with the ACC/AHA guidelines to continue these agents before surgery; however, I favor holding them on the day of surgery. Although the risk of hypotension-induced cardiac events has not been clearly demonstrated, a recent retrospective study involving more than 1,100 patients showed significantly more acute kidney injury (even after adjusting for hypotension) as well as an increased length of hospital stay in the patients exposed to these agents before surgery.9 Given these findings, in addition to the postinduction hypotension (which can be profound) commonly observed by our anesthesiology colleagues, I recommend holding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the day of surgery, with very few exceptions.

THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MEDICINE

Dr. Cohn acknowledges that we lack scientific data to answer many questions that arise when caring for the perioperative patient and thus we rely on the ACC/AHA guidelines to provide a framework. These scientific knowledge gaps emphasize the importance of the art of medicine in the perioperative arena. Although we may desire “cookbook” guidelines, the significant gaps in the perioperative medicine evidence base reinforce the necessity to provide individual patient-level care in a multidisciplinary environment with our surgery and anesthesiology colleagues. Without the proper balance of science and art in perioperative medicine, we sacrifice our ability to deliver optimal care for this high-risk patient population.

- Cohn SL. Updated guidelines on cardiovascular evaluation before noncardiac surgery: a view from the trenches. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:742–751.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. pii: S0735-1097(14)05536-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print].

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation 2011; 124:381–387.

- Aronson WL, McAuliffe MS, Miller K. Variability in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification Scale. AANA J 2003; 71:265–274.

- Mak PH, Campbell RC, Irwin MG; American Society of Anesthesiologists. The ASA Physical Status Classification: inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anaesth Intensive Care 2002; 30:633–640.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1494–1503.

- Nielson E, Hennrikus E, Lehman E, Mets B. Angiotensin axis blockade, hypotension, and acute kidney injury in elective major orthopedic surgery. J Hosp Med 2014; 9:283–288.

- Cohn SL. Updated guidelines on cardiovascular evaluation before noncardiac surgery: a view from the trenches. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:742–751.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. pii: S0735-1097(14)05536-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print].

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation 2011; 124:381–387.

- Aronson WL, McAuliffe MS, Miller K. Variability in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification Scale. AANA J 2003; 71:265–274.

- Mak PH, Campbell RC, Irwin MG; American Society of Anesthesiologists. The ASA Physical Status Classification: inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anaesth Intensive Care 2002; 30:633–640.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1494–1503.

- Nielson E, Hennrikus E, Lehman E, Mets B. Angiotensin axis blockade, hypotension, and acute kidney injury in elective major orthopedic surgery. J Hosp Med 2014; 9:283–288.

Ebola—lessons still to be learned

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Kyle Brizendine reviews the basics of the Ebola virus and its natural history, diagnosis, and management.

Like many of you, I have followed the Ebola story with disquietude. So far, the disease has barely touched our country, with fewer than 10 confirmed cases on US soil, but it has had a big impact on our health care system and our national psyche.

The creation of specialized containment and management units may deplete some hospitals and their communities of intensive care beds. Specially trained caregivers will need to be diverted to staff these units, and the public’s fear may dissuade patients from undergoing elective procedures at hospitals caring for patients with Ebola. All of these pose a financial challenge to the hospitals most capable of dealing with these patients.

We have yet to hear about management guidelines dealing with renal replacement therapy and ventilator support, which may extend life but also pose extra risks to caregivers. Do we understand the disease well enough to know when advanced supportive therapies might be futile? Many lessons were learned from the Liberian patient who died of Ebola in Dallas, but many more clinical questions remain. I had hoped that in our sophisticated ICUs patients treated relatively early with aggressive supportive care would likely survive. We do not yet know if that is true. One death does not make it false, but it does give one pause.

About a half dozen other Ebola patients have survived with treatment here, but they were not African. Does genetic background play a role in disease severity and survival? Were the survivors treated sooner or differently in ways that matter? How much of the end-organ damage from the virus is from direct organ infection that cannot be reversed or prevented by even the best supportive treatment? Does the ability of the virus to suppress the immune system doom patients to opportunistic infections during prolonged supportive therapy? Is the viral-associated immunosuppression enough to prevent some patients from mounting an effective innate (interferon-based) or acquired (viral-specific T-cell or humoral) antiviral response? And is transfusing blood from survivors, presumably conferring passive immunity, actually efficacious?

I was relieved there were no new Ebola cases among the staff caring for Mr. Duncan at his second emergency room visit in Dallas, since at that time he was clearly quite ill, viremic, and contagious. Universal safety precautions must have helped. But how did the other nurses become infected, even though they presumably wore better protection? Hopefully, we will gain further understanding of transmissibility and resistance. We need this knowledge to inform safe and manageable protocols of care, particularly if successful vaccine development is delayed.

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Kyle Brizendine reviews the basics of the Ebola virus and its natural history, diagnosis, and management.

Like many of you, I have followed the Ebola story with disquietude. So far, the disease has barely touched our country, with fewer than 10 confirmed cases on US soil, but it has had a big impact on our health care system and our national psyche.

The creation of specialized containment and management units may deplete some hospitals and their communities of intensive care beds. Specially trained caregivers will need to be diverted to staff these units, and the public’s fear may dissuade patients from undergoing elective procedures at hospitals caring for patients with Ebola. All of these pose a financial challenge to the hospitals most capable of dealing with these patients.

We have yet to hear about management guidelines dealing with renal replacement therapy and ventilator support, which may extend life but also pose extra risks to caregivers. Do we understand the disease well enough to know when advanced supportive therapies might be futile? Many lessons were learned from the Liberian patient who died of Ebola in Dallas, but many more clinical questions remain. I had hoped that in our sophisticated ICUs patients treated relatively early with aggressive supportive care would likely survive. We do not yet know if that is true. One death does not make it false, but it does give one pause.

About a half dozen other Ebola patients have survived with treatment here, but they were not African. Does genetic background play a role in disease severity and survival? Were the survivors treated sooner or differently in ways that matter? How much of the end-organ damage from the virus is from direct organ infection that cannot be reversed or prevented by even the best supportive treatment? Does the ability of the virus to suppress the immune system doom patients to opportunistic infections during prolonged supportive therapy? Is the viral-associated immunosuppression enough to prevent some patients from mounting an effective innate (interferon-based) or acquired (viral-specific T-cell or humoral) antiviral response? And is transfusing blood from survivors, presumably conferring passive immunity, actually efficacious?

I was relieved there were no new Ebola cases among the staff caring for Mr. Duncan at his second emergency room visit in Dallas, since at that time he was clearly quite ill, viremic, and contagious. Universal safety precautions must have helped. But how did the other nurses become infected, even though they presumably wore better protection? Hopefully, we will gain further understanding of transmissibility and resistance. We need this knowledge to inform safe and manageable protocols of care, particularly if successful vaccine development is delayed.

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Kyle Brizendine reviews the basics of the Ebola virus and its natural history, diagnosis, and management.

Like many of you, I have followed the Ebola story with disquietude. So far, the disease has barely touched our country, with fewer than 10 confirmed cases on US soil, but it has had a big impact on our health care system and our national psyche.

The creation of specialized containment and management units may deplete some hospitals and their communities of intensive care beds. Specially trained caregivers will need to be diverted to staff these units, and the public’s fear may dissuade patients from undergoing elective procedures at hospitals caring for patients with Ebola. All of these pose a financial challenge to the hospitals most capable of dealing with these patients.

We have yet to hear about management guidelines dealing with renal replacement therapy and ventilator support, which may extend life but also pose extra risks to caregivers. Do we understand the disease well enough to know when advanced supportive therapies might be futile? Many lessons were learned from the Liberian patient who died of Ebola in Dallas, but many more clinical questions remain. I had hoped that in our sophisticated ICUs patients treated relatively early with aggressive supportive care would likely survive. We do not yet know if that is true. One death does not make it false, but it does give one pause.

About a half dozen other Ebola patients have survived with treatment here, but they were not African. Does genetic background play a role in disease severity and survival? Were the survivors treated sooner or differently in ways that matter? How much of the end-organ damage from the virus is from direct organ infection that cannot be reversed or prevented by even the best supportive treatment? Does the ability of the virus to suppress the immune system doom patients to opportunistic infections during prolonged supportive therapy? Is the viral-associated immunosuppression enough to prevent some patients from mounting an effective innate (interferon-based) or acquired (viral-specific T-cell or humoral) antiviral response? And is transfusing blood from survivors, presumably conferring passive immunity, actually efficacious?

I was relieved there were no new Ebola cases among the staff caring for Mr. Duncan at his second emergency room visit in Dallas, since at that time he was clearly quite ill, viremic, and contagious. Universal safety precautions must have helped. But how did the other nurses become infected, even though they presumably wore better protection? Hopefully, we will gain further understanding of transmissibility and resistance. We need this knowledge to inform safe and manageable protocols of care, particularly if successful vaccine development is delayed.

Ebola virus: Questions, answers, and more questions

A 50-year-old man who returned from a business trip to Nigeria 24 days ago presents with complaints of the sudden onset of fever, diarrhea, myalgia, and headache. He reports 10 bowel movements per day and has seen bloody stools.

During his trip he flew in to Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, ate meals only in his hotel, and attended meetings in Lagos central business district. He had no exposure to animals, mosquitoes, ticks, or sick people, and no sexual activity. After returning home, he felt well for the first 3 weeks.

The patient has a history of hypertension. He does not smoke, drink alcohol, or use injection drugs. He is married, works with commercial banks and financial institutions, and lives in Cleveland, OH.

On physical examination his temperature is 100.0˚F (37.8˚C), pulse 98, respirations 15, blood pressure 105/70 mm Hg, and weight 78 kg (172 lb). He appears comfortable but is a little diaphoretic. His abdomen is tender to palpation in the epigastrium and slightly to the right; he has no signs of peritonitis. His skin is without rash, bleeding, or bruising. The remainder of the examination is normal.

His white blood cell count is 17 × 109/L, hemoglobin 15 g/dL, hematocrit 41%, and platelet count 172 × 109/L. His sodium level is 126 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, chloride 95 mmol/L, carbon dioxide 20 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 11 mg/dL, creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, and glucose 130 mg/dL. His aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels are normal.

Could this patient have Ebola virus disease?

With Ebola virus disease on the rise in West Africa, physicians who encounter patients like this one need to include it in the differential diagnosis. Because the disease is new, many questions are raised for which we as yet have no answers. Here, I will review what we know and do not know in an effort to remove some of the fear and uncertainty.

A NEW DISEASE

Ebola virus disease is a severe hemorrhagic fever caused by negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses as belonging to the genus Ebolavirus in the family Filoviridae. Filoviruses get their name from the Latin filum, or thread-like structure.

The family Filoviridae was discovered in 1967 after inadvertent importation of infected monkeys from Uganda into Yugoslavia and Marburg, Germany. Outbreaks of severe illness occurred in workers at a vaccine plant who came into direct contact with the animals by killing them, removing their kidneys, or preparing primary cell cultures for polio vaccine production.

Ebola virus was discovered in 1976 by Peter Piot, who was working at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium. The blood of a Belgian woman who had been working in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) had been sent to the institute; she and Mabalo Lokela, a school headmaster and the first recorded victim of Ebola virus, had been working near Yambuku, about 96 km from the Ebola River.

Before the 2014 outbreak, all known outbreaks had caused fewer than 2,400 cases across a dozen African countries over 3 decades.

Five species of Ebola virus

The genus Ebolavirus contains five species, each associated with a consistent case-fatality rate and a more or less well-identified endemic area.1

Zaire ebolavirus was recognized in 1976; it has caused multiple outbreaks, with high case-fatality rates.

Sudan ebolavirus was seen first in the 1970s; it has a 50% case-fatality rate.

Tai Forest ebolavirus has been found in only one person, an ethologist working with deceased chimpanzees.

Bundibugyo ebolavirus emerged in 2007 and has a 30% case-fatality rate.

Reston ebolavirus is maintained in an animal reservoir in the Philippines and is not found in Africa. It caused an outbreak of lethal infection in macaques imported into the United States in 1989. There is evidence that Reston ebolavirus can cause asymptomatic infection in humans. None of the caretakers of the macaques became ill, nor did farmers working with infected pigs, although both groups seroconverted.

A reservoir in bats?

A reservoir in nonhuman primates was initially suspected. However, studies subsequently showed that monkeys are susceptible to rapidly lethal filoviral disease, precluding any role as a host for persistent viral infection. It is likely that Ebola virus is maintained in small animals that serve as a source of infection for both humans and wild primates. A prominent suspect is fruit bats, which are consumed in soup in West Africa.

Transmission is person-to-person or nosocomial

Ebola virus is transmitted by direct contact with body fluids such as blood, urine, sweat, vomitus, semen, and breast milk. Filoviruses can initiate infection via ingestion, inhalation (although probably not Ebola), or passage through breaks in the skin. Droplet inoculation into the mouth or eyes has been shown to result from inadvertent transfer of virus from contaminated hands. Patients transmit the virus while febrile and through later stages of disease, as well as postmortem through contact with the body during funeral preparations. The virus has been isolated in semen for as many as 61 days after illness onset.

Ebola virus can also be spread nosocomially. In 1976, a 44-year-old teacher sought care for fever at the Yambuku Mission Hospital. He was given parenteral chloroquine as empiric treatment for presumed malaria, which was routine for all febrile patients. However, he had unrecognized Ebola virus infection. Moreover, syringes were rinsed in the same pan of water and reused, which spread the infection to nearly 100 people, all of whom developed fulminant Ebola virus disease and died. Infection then spread to family caregivers, the hospital staff, and those who prepared the bodies for burial.

Nosocomial transmission was also responsible for an outbreak of Lake Victoria Marburg virus in Uige Province in northern Angola in 2005, with 374 putative cases and 329 deaths. When teams from Médecins Sans Frontières started setting up the Marburg ward, there were five patients with hemorrhagic fever in a makeshift isolation room in the hospital, together with corpses that the hospital staff had been too afraid to remove. Healers found in many rural African communities were administering injections in homes or in makeshift clinics with reused needles or syringes.2

There is no evidence that filoviruses are carried by mosquitoes or other biting arthropods. Also, the risk of transmission via fomites appears to be low when currently recommended infection-control guidelines for the viral hemorrhagic fevers are followed.3 One primary human case generates only one to three secondary cases on average.

EBOLA IS AN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

The main targets of infection are endothelial cells, mononuclear phagocytes, and hepatocytes. Ebola virus replicates at an unusually high rate. Macrophages infected with Zaire ebolavirus produce tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin (IL) 1 beta, IL-6, macrophage chemotactic protein 1, and nitric oxide. Virus-infected macrophages synthesize cell-surface tissue factor, triggering the extrinsic coagulation pathway.

Ebola is an immunodeficiency virus. Dendritic cells, which initiate adaptive immune responses, are a major site of filoviral replication. Infected cells cannot present antigens to naïve lymphocytes. Patients who die of Ebola virus disease do not develop antibodies to the virus. Lymphocytes remain uninfected, but undergo “bystander” apoptosis induced by inflammatory mediators.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The incubation period is generally 5 to 7 days (range 2 to 28 days), during which the patient is not infectious. Symptoms begin abruptly, with fever, chills, general malaise, weakness, severe headache, and myalgia. By the time of case detection in West Africa, most patients also had nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Once symptoms arise, patients have high levels of the virus in their blood and fluids and are infectious. Hemorrhagic symptoms have apparently been uncommon in West Africa, occurring in 1.0% to 5.7%, but “unexplained bleeding” has been documented in 18% of cases.4 Among those in whom the disease enters its hemorrhagic terminal phase, there is characteristic internal and subcutaneous bleeding, vomiting of blood, and subconjunctival hemorrhage.4

Laboratory findings include lymphocytopenia (often with counts as low as 1.0 × 109/L), thrombocytopenia (with counts in the range of 50 to 100 × 109/L), elevated aminotransferase levels (including aspartate aminotransferase levels 7 to 12 times higher than alanine aminotransferase in fatal cases), low total protein (due to capillary leak), and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Those who survive begin to improve in the second week, during which viremia resolves in association with the appearance of virus-specific antibodies.4

DIAGNOSIS

In symptomatic patients, Ebola virus infection is diagnosed by detection in blood or body fluids of viral antigens by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, or RNA sequences by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. The diagnosis is confirmed with cell culture (in a BSL-4 containment laboratory) showing characteristic viral particles by electron microscopy.

CARING FOR PATIENTS

The most detailed descriptions of the care of patients with Ebola virus disease have come from Dr. Bruce Ribner, of Emory University Hospital, in an October 2014 report of his experience caring for Ebola-infected patients at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, GA.5 He described fluid losses of 5 to 10 L/day, profound hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia, which were associated with cardiac arrhythmias and the need for intravenous and oral electrolyte repletion and hemodialysis. Intensive one-to-one nursing was critical, as was the coordination of many medical subspecialties. The Emory team arranged point-of-care testing near the unit and generally kept laboratory testing to a minimum. The team was surprised to learn that commercial carriers refused to transport specimens even when they were licensed for category A agents. Difficulties with the local water authority and waste disposal contractor required the hospital to dedicate an autoclave to process all materials used in clinical care.

TREATMENT: SUPPORTIVE AND EXPERIMENTAL

Treatment is supportive to maintain circulatory function and blood pressure and to correct coagulopathy. However, a variety of vaccines, antibodies, small-molecule agents, and antiviral agents are undergoing testing, mostly in animals at this point.

Vaccines. A therapeutic vaccine that worked only slightly was a live-attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing Ebola virus transmembrane glycoproteins, which was tested in mice, guinea pigs, and rhesus macaques who had been exposed to Ebola virus.6

A preventive vaccine worked better. Stanley et al7 evaluated a replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3-vectored vaccine that also contained Ebola virus glycoprotein. They gave macaques a single injection of this vaccine, and then 5 weeks later gave them a lethal dose of Ebola virus. All the vaccinated animals survived the infection, and half (2 of 4) survived when challenged 10 months later. With a prime-boost strategy (modified vaccinia virus Ankara, a poxvirus), all survived when challenged 10 months later.

KZ52, a neutralizing antibody, did not work. Oswald et al8 gave a human IgG monoclonal antibody against Zaire Ebola virus, designated KZ52, to four rhesus macaques, challenged them with the virus 24 hours later, and administered a second shot of KZ52 on day 4. All of them died.

ZMAb is a combination of three murine monoclonal antibodies, designated 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7. Ad-IFN is a human adenovirus, serotype 5, that expresses human interferon alpha. Qui et al9 gave ZMAb and Ad-IFN to macaques in several experiments. In experiment 1, eight macaques were infected and then were given ZMAb and Ad-IFN 3 days later, and ZMAb again on days 6 and 9. Seven of the eight survived. In a second experiment, Ad-IFN was given first, when the viral load was still less than the limit of detection of known assays, and then ZMAb was given upon detection of viremia and fever. Two of four macaques survived. Control animals had undetectable levels of IgG, whereas Ebola virus GP–specific IgG levels were detected in all survivors. IFN-gamma ELISpots showed high EBOV-GP–specific T-cell response in all survivors.

ZMapp is another cocktail of monoclonal antibodies, containing two from ZMab (2G4 and 4G7), plus a third, c13C6. In experiments in rhesus macaques, three groups of six animals each received three doses of ZMapp at varying times after being infected with Ebola virus: at 3, 6, and 9 days; at 4, 7, and 10 days, and at 5, 8, and 11 days. All 18 macaques treated with ZMapp survived. Thus, Zmapp extended the treatment window to 5 days postexposure.10 One of the American health care workers who contracted Ebola virus in Liberia received this medication.

HSPA5-PMO. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone heat shock 70 kDa protein 5 (HSPA5) is instrumental in the maturation of envelope proteins in hepatitis C and influenza A virus. It plays a role in viral entry for coxsackievirus A9 and dengue virus serotype 2, and it may be involved in Ebola viral budding. Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) are a class of antisense DNA nucleotide analogs.

Reid et al11 reported that mice treated with HSPA5–PMO were completely protected from lethal Ebola challenge. Therefore, HSPA5 appears to be a promising target for the development of antifilovirus countermeasures.

Favipiravir, an antiviral agent also known as T-705, is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative. Invented in 2002 by Toyama Chemicals as an inhibitor of influenza virus replication, it acts as a nucleotide analog, selectively inhibiting the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, or causes lethal mutagenesis upon incorporation into the virus RNA. Favipiravir suppresses Ebola virus replication by 4 log10 units in cell culture.12

Mice were challenged with intranasal inoculation of 1,000 focus-forming units of Ebola virus diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. Until the first day of treatment (postinfection day 6), all mice in the T-705 group lost weight similarly to control mice, developed viremia, and showed elevated serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. Within 4 days of T-705 treatment (post-infection day 10), the animals had cleared the virus from blood. Surviving mice developed Ebola virus-specific antibodies and CD8+ T cells specific for the viral nucleoprotein.12

The authors hypothesized that suppression of virus replication by T-705 allowed the host to mount a virus-specific adaptive immune response, and concluded that T-705 was 100% effective in the treatment of Zaire Ebola virus infection up to postinfection day 6 but was hardly beneficial at the terminal stage of disease.12 Of note, favipiravir is undergoing phase 2 and phase 3 trials as an anti-influenza agent in Japan.

THE CURRENT OUTBREAK

The current outbreak is with Zaire ebolavirus. It seems to have started in a 2-year-old child who died in Meliandou in Guéckédou Prefecture, Guinea, on December 6, 2013. On March 21, 2014, the Guinea Ministry of Health reported the outbreak of an illness characterized by fever, severe diarrhea, vomiting, and a high case-fatality rate (59%) in 49 persons. On May 25, 2014, Kenema Government Hospital confirmed the first case of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone, probably brought there by a traditional healer who had treated Ebola patients from Guinea. Tracing led to 13 additional cases—all women who attended the burial.13

The Center for Systems Biology at Harvard University and the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology generated 99 Ebola virus genome sequences from 78 patients with confirmed disease, representing more than 70% of the patients diagnosed with the disease in Sierra Leone from May to mid-June 2014. They found genetic similarity across the sequenced 2014 samples, suggesting a single transmission from the natural reservoir, followed by human-to-human transmission during the outbreak. Continued human-reservoir exposure is unlikely to have contributed to the growth of this epidemic.14

As of October 14, 2014, there were 8,914 suspected and confirmed cases of Ebola virus infection, and 4,477 deaths.15

But how did Zaire Ebola virus make the 2,000-mile trek from Central Africa to Guinea in West Africa? There are two possibilities: it has always been present in the region but we just never noticed, or it was recently introduced. Bayesian phylogenetic analyses and sequence divergence studies suggest the virus has been present in bat populations in Guinea without previously infecting humans.

Why Guinea and why Guéckédou? Guinea is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 178th of 187 countries on the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme, just behind Liberia (174th) and Sierra Leone (177th). In Guinea, the life expectancy is 56 years and the gross national income per capita is $440. The region has been systematically plundered and the forest decimated by clear-cut logging, leaving the Guinea Forest Region largely deforested, resulting in increased contact between humans and the small animals that serve as the source of infection.1

LIMITED CAPACITY, EVEN IN THE UNITED STATES

A few hospitals in the United States have dedicated units to handle serious infectious diseases such as Ebola: Emory University Hospital; Nebraska Medicine in Omaha; Providence St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, MT; and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD. However, in total they have only 19 beds.

QUESTIONS, ANSWERS—AND MORE QUESTIONS

(The following is from a question-and-answer discussion that followed Dr. Brizendine’s Grand Rounds presentation.)

Q: Are there any differences between survivors and those who die of the disease? A: We do not know. Patient survival depends on early recognition and supportive care. There are disparities in the care of patients. Schieffelin et al16 analyzed the characteristics of patients who died or who survived in Sierra Leone and found that the mortality rate was higher in older patients and those with a higher viral load on presentation.

Q: Does the virus block production or release of interferon early in infection? A: Yes, it has been shown17 that Ebola virus protein VP24 inhibits signaling downstream of both interferon alpha/beta and interferon gamma by indirectly impairing the transport of a transcription factor termed STAT1. VP24 is also able to bind STAT1 directly. The resulting suppression of host interferon very early on in the incubation phase is key to the virulence of the virus.

Q: Does infection with one of the viral species confer immunity from other species? A: No, there is no cross-immunity.

Q: How soon do patients test positive? A: About 5 days after exposure, when they develop a fever. At this time patients are highly viremic, which PCR can detect.

Q: Before the virus is detectable in the blood, where is it? A: The liver, endothelial cells, antigen-presenting cells, and adrenal glands.

Q: Do we really need to quarantine ill patients and health care workers returning from Africa, per CDC recommendations? A: We don’t know everything, and some people do make bad decisions, such as traveling while symptomatic. I support a period of observation, although confinement is not reasonable, as it may pose a disincentive to cooperation.

Q: What is the role of giving plasma from survivors? A: Dr. Kent Brantly (see American citizens infected with Ebola) received the blood of a 14-year-old who survived. We don’t know. It is not proved. It did not result in improvement in animal models.

Q: Is the bleeding caused by a mechanism similar to that in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection? A: No. That is a bacterial toxin, whereas this is more like disseminated intravascular coagulation, with an intrinsic pathway anticoagulation cascade.

Q: How long does the virus remain viable outside the body? A: In one study,18 Ebola virus could not be recovered from experimentally contaminated surfaces (plastic, metal or glass) at room temperature. In another in which it was dried onto a surface,19 Ebola virus survived in the dark for several hours between 20 and 25°C. When dried in tissue culture media onto glass and stored at 4°C, it has survived for over 50 days.

Q: How long does the virus remain in breast milk? A: We know it has been detected 15 days after disease onset and think possibly as late as 28 days from symptom onset.3

Q: How are people actually infected? A: I believe people get the virus on their hands and then touch their face, eyes, or mouth. If you are wearing personal protective equipment, it must occur while doffing the equipment.

Q: Could we increase the sensitivity of the test so that we could detect the virus before the onset of symptoms? A: In theory it may be possible. The virus is somewhere in the body during the incubation period. Perhaps we could sample the right compartment in an enriched mononuclear cell line.

Q: When can patients who recover resume their normal activities? A: After their viral load returns to 0, I would still advise abstaining from unprotected sex and from breastfeeding for a few months. but as for other activities, no special precautions are needed.

Q: Does the virus appear to be mutating at a high rate? A: Looking back to 2004, mutations are occurring, but there is no sign that any of these mutations has contributed to the size of the outbreak by changing the characteristics of the Ebola virus. Can it become aerosolized? It has been suggested that the virus that caused the outbreak separated from those that caused past Ebola outbreaks but does not seem to be affecting the spread or efficacy of experimental drugs and vaccines. So, even though it is an RNA virus and mutations are occurring, no serious changes have emerged.14

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

The differential diagnosis for the patient described at the beginning of this paper includes travelers’ diarrhea, malaria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, meningococcal disease … and Ebola virus disease, although this is much less likely in view of the epidemiology and incubation period of this disease. When his stool was tested by enzyme immunoassay and culture, it was found to be positive for Campylobacter. He recovered with oral rehydration.

- Bausch DG, Schwarz L. Outbreak of ebola virus disease in Guinea: where ecology meets economy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e3056.

- Roddy P, Thomas SL, Jeffs B, et al. Factors associated with Marburg hemorrhagic fever: analysis of patient data from Uige, Angola. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:1909–1918.

- Bausch DG, Towner JS, Dowell SF, et al. Assessment of the risk of Ebola virus transmission from bodily fluids and fomites. J Infect Dis 2007; 196(suppl 2):S142–S147.

- WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1481–1495.

- Ribner BS. Treating patients with Ebola virus infections in the US: lessons learned. Presented at IDWeek, October 8, 2014. Philadelphia PA.

- Feldman H, Jones SM, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, et al. Effective post-exposure treatment of Ebola infection. PLoS Pathog 2007; 3:e2.

- Stanley DA, Honko AN, Asiedu C, et al. Chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine generates acute and durable protective immunity against ebolavirus challenge. Nat Med 2014; 20:1126–1129.

- Oswald WB, Geisbert TW, Davis KJ, et al. Neutralizing antibody fails to impact the course of Ebola virus infection in monkeys. PLos Pathog 2007; 3:e9.

- Qui X, Wong G, Fernando L, et al. mAbs and Ad-vectored IFN-a therapy rescue Ebola-infected nonhuman primates when administered after the detection of viremia and symptoms. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5:207ra143.

- Qui X, Wong G, Audet J, et al. Reversion of advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman primates with ZMapp. Nature 2014; 514:47–53.

- Reid SP, Shurtleff AC, Costantino JA, et al. HSPA5 is an essential host factor for Ebola virus infection. Antiviral Res 2014; 109:171–174.

- Oestereich L, Lüdtke A, Wurr S, Rieger T, Muñoz-Fontela C, Günther S. Successful treatment of advanced Ebola virus infection with T-705 (favipiravir) in a small animal model. Antiviral Res 2014; 105:17–21.

- Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, et al. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus dsease in Guinea. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1418–1425.

- Gire SK, Goba A, Andersen KG, et al. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 2014; 345:1369–1372.

- Chamary JV. 4000 deaths and counting: the Ebola epidemic in 4 charts. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/jvchamary/2014/10/13/ebola-trends. Accessed November 5, 2014.

- Schieffelin JS, Shaffer JG, Goba A, et al, for the KGH Lassa Fever Program, the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Consortium, and the WHO Clinical Response Team. Clinical illness and outcomes in patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. N Engl J Med 2014 Oct 29 [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411680.

- Zhang AP, Bornholdt ZA, Liu T, et al. The ebola virus interferon antagonist VP24 directly binds STAT1 and has a novel, pyramidal fold. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002550.

- Piercy TJ, Smither SJ, Steward JA, Eastaugh L, Lever MS. The survival of filoviruses in liquids, on solid substrates and in a dynamic aerosol. J Appl Microbiol 2010; 109:1531–1539.

- Sagripanti JL, Rom AM, Holland LE. Persistence in darkness of virulent alphaviruses, Ebola virus, and Lassa virus deposited on solid surfaces. Arch Virol 2010; 155:2035–2039.

A 50-year-old man who returned from a business trip to Nigeria 24 days ago presents with complaints of the sudden onset of fever, diarrhea, myalgia, and headache. He reports 10 bowel movements per day and has seen bloody stools.

During his trip he flew in to Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, ate meals only in his hotel, and attended meetings in Lagos central business district. He had no exposure to animals, mosquitoes, ticks, or sick people, and no sexual activity. After returning home, he felt well for the first 3 weeks.

The patient has a history of hypertension. He does not smoke, drink alcohol, or use injection drugs. He is married, works with commercial banks and financial institutions, and lives in Cleveland, OH.

On physical examination his temperature is 100.0˚F (37.8˚C), pulse 98, respirations 15, blood pressure 105/70 mm Hg, and weight 78 kg (172 lb). He appears comfortable but is a little diaphoretic. His abdomen is tender to palpation in the epigastrium and slightly to the right; he has no signs of peritonitis. His skin is without rash, bleeding, or bruising. The remainder of the examination is normal.

His white blood cell count is 17 × 109/L, hemoglobin 15 g/dL, hematocrit 41%, and platelet count 172 × 109/L. His sodium level is 126 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, chloride 95 mmol/L, carbon dioxide 20 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 11 mg/dL, creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, and glucose 130 mg/dL. His aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels are normal.

Could this patient have Ebola virus disease?

With Ebola virus disease on the rise in West Africa, physicians who encounter patients like this one need to include it in the differential diagnosis. Because the disease is new, many questions are raised for which we as yet have no answers. Here, I will review what we know and do not know in an effort to remove some of the fear and uncertainty.

A NEW DISEASE

Ebola virus disease is a severe hemorrhagic fever caused by negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses as belonging to the genus Ebolavirus in the family Filoviridae. Filoviruses get their name from the Latin filum, or thread-like structure.

The family Filoviridae was discovered in 1967 after inadvertent importation of infected monkeys from Uganda into Yugoslavia and Marburg, Germany. Outbreaks of severe illness occurred in workers at a vaccine plant who came into direct contact with the animals by killing them, removing their kidneys, or preparing primary cell cultures for polio vaccine production.

Ebola virus was discovered in 1976 by Peter Piot, who was working at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium. The blood of a Belgian woman who had been working in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) had been sent to the institute; she and Mabalo Lokela, a school headmaster and the first recorded victim of Ebola virus, had been working near Yambuku, about 96 km from the Ebola River.

Before the 2014 outbreak, all known outbreaks had caused fewer than 2,400 cases across a dozen African countries over 3 decades.

Five species of Ebola virus

The genus Ebolavirus contains five species, each associated with a consistent case-fatality rate and a more or less well-identified endemic area.1

Zaire ebolavirus was recognized in 1976; it has caused multiple outbreaks, with high case-fatality rates.

Sudan ebolavirus was seen first in the 1970s; it has a 50% case-fatality rate.

Tai Forest ebolavirus has been found in only one person, an ethologist working with deceased chimpanzees.

Bundibugyo ebolavirus emerged in 2007 and has a 30% case-fatality rate.

Reston ebolavirus is maintained in an animal reservoir in the Philippines and is not found in Africa. It caused an outbreak of lethal infection in macaques imported into the United States in 1989. There is evidence that Reston ebolavirus can cause asymptomatic infection in humans. None of the caretakers of the macaques became ill, nor did farmers working with infected pigs, although both groups seroconverted.

A reservoir in bats?

A reservoir in nonhuman primates was initially suspected. However, studies subsequently showed that monkeys are susceptible to rapidly lethal filoviral disease, precluding any role as a host for persistent viral infection. It is likely that Ebola virus is maintained in small animals that serve as a source of infection for both humans and wild primates. A prominent suspect is fruit bats, which are consumed in soup in West Africa.

Transmission is person-to-person or nosocomial

Ebola virus is transmitted by direct contact with body fluids such as blood, urine, sweat, vomitus, semen, and breast milk. Filoviruses can initiate infection via ingestion, inhalation (although probably not Ebola), or passage through breaks in the skin. Droplet inoculation into the mouth or eyes has been shown to result from inadvertent transfer of virus from contaminated hands. Patients transmit the virus while febrile and through later stages of disease, as well as postmortem through contact with the body during funeral preparations. The virus has been isolated in semen for as many as 61 days after illness onset.

Ebola virus can also be spread nosocomially. In 1976, a 44-year-old teacher sought care for fever at the Yambuku Mission Hospital. He was given parenteral chloroquine as empiric treatment for presumed malaria, which was routine for all febrile patients. However, he had unrecognized Ebola virus infection. Moreover, syringes were rinsed in the same pan of water and reused, which spread the infection to nearly 100 people, all of whom developed fulminant Ebola virus disease and died. Infection then spread to family caregivers, the hospital staff, and those who prepared the bodies for burial.

Nosocomial transmission was also responsible for an outbreak of Lake Victoria Marburg virus in Uige Province in northern Angola in 2005, with 374 putative cases and 329 deaths. When teams from Médecins Sans Frontières started setting up the Marburg ward, there were five patients with hemorrhagic fever in a makeshift isolation room in the hospital, together with corpses that the hospital staff had been too afraid to remove. Healers found in many rural African communities were administering injections in homes or in makeshift clinics with reused needles or syringes.2

There is no evidence that filoviruses are carried by mosquitoes or other biting arthropods. Also, the risk of transmission via fomites appears to be low when currently recommended infection-control guidelines for the viral hemorrhagic fevers are followed.3 One primary human case generates only one to three secondary cases on average.

EBOLA IS AN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

The main targets of infection are endothelial cells, mononuclear phagocytes, and hepatocytes. Ebola virus replicates at an unusually high rate. Macrophages infected with Zaire ebolavirus produce tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin (IL) 1 beta, IL-6, macrophage chemotactic protein 1, and nitric oxide. Virus-infected macrophages synthesize cell-surface tissue factor, triggering the extrinsic coagulation pathway.

Ebola is an immunodeficiency virus. Dendritic cells, which initiate adaptive immune responses, are a major site of filoviral replication. Infected cells cannot present antigens to naïve lymphocytes. Patients who die of Ebola virus disease do not develop antibodies to the virus. Lymphocytes remain uninfected, but undergo “bystander” apoptosis induced by inflammatory mediators.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The incubation period is generally 5 to 7 days (range 2 to 28 days), during which the patient is not infectious. Symptoms begin abruptly, with fever, chills, general malaise, weakness, severe headache, and myalgia. By the time of case detection in West Africa, most patients also had nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Once symptoms arise, patients have high levels of the virus in their blood and fluids and are infectious. Hemorrhagic symptoms have apparently been uncommon in West Africa, occurring in 1.0% to 5.7%, but “unexplained bleeding” has been documented in 18% of cases.4 Among those in whom the disease enters its hemorrhagic terminal phase, there is characteristic internal and subcutaneous bleeding, vomiting of blood, and subconjunctival hemorrhage.4

Laboratory findings include lymphocytopenia (often with counts as low as 1.0 × 109/L), thrombocytopenia (with counts in the range of 50 to 100 × 109/L), elevated aminotransferase levels (including aspartate aminotransferase levels 7 to 12 times higher than alanine aminotransferase in fatal cases), low total protein (due to capillary leak), and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Those who survive begin to improve in the second week, during which viremia resolves in association with the appearance of virus-specific antibodies.4

DIAGNOSIS

In symptomatic patients, Ebola virus infection is diagnosed by detection in blood or body fluids of viral antigens by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, or RNA sequences by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. The diagnosis is confirmed with cell culture (in a BSL-4 containment laboratory) showing characteristic viral particles by electron microscopy.

CARING FOR PATIENTS

The most detailed descriptions of the care of patients with Ebola virus disease have come from Dr. Bruce Ribner, of Emory University Hospital, in an October 2014 report of his experience caring for Ebola-infected patients at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, GA.5 He described fluid losses of 5 to 10 L/day, profound hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia, which were associated with cardiac arrhythmias and the need for intravenous and oral electrolyte repletion and hemodialysis. Intensive one-to-one nursing was critical, as was the coordination of many medical subspecialties. The Emory team arranged point-of-care testing near the unit and generally kept laboratory testing to a minimum. The team was surprised to learn that commercial carriers refused to transport specimens even when they were licensed for category A agents. Difficulties with the local water authority and waste disposal contractor required the hospital to dedicate an autoclave to process all materials used in clinical care.

TREATMENT: SUPPORTIVE AND EXPERIMENTAL

Treatment is supportive to maintain circulatory function and blood pressure and to correct coagulopathy. However, a variety of vaccines, antibodies, small-molecule agents, and antiviral agents are undergoing testing, mostly in animals at this point.

Vaccines. A therapeutic vaccine that worked only slightly was a live-attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing Ebola virus transmembrane glycoproteins, which was tested in mice, guinea pigs, and rhesus macaques who had been exposed to Ebola virus.6

A preventive vaccine worked better. Stanley et al7 evaluated a replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3-vectored vaccine that also contained Ebola virus glycoprotein. They gave macaques a single injection of this vaccine, and then 5 weeks later gave them a lethal dose of Ebola virus. All the vaccinated animals survived the infection, and half (2 of 4) survived when challenged 10 months later. With a prime-boost strategy (modified vaccinia virus Ankara, a poxvirus), all survived when challenged 10 months later.

KZ52, a neutralizing antibody, did not work. Oswald et al8 gave a human IgG monoclonal antibody against Zaire Ebola virus, designated KZ52, to four rhesus macaques, challenged them with the virus 24 hours later, and administered a second shot of KZ52 on day 4. All of them died.

ZMAb is a combination of three murine monoclonal antibodies, designated 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7. Ad-IFN is a human adenovirus, serotype 5, that expresses human interferon alpha. Qui et al9 gave ZMAb and Ad-IFN to macaques in several experiments. In experiment 1, eight macaques were infected and then were given ZMAb and Ad-IFN 3 days later, and ZMAb again on days 6 and 9. Seven of the eight survived. In a second experiment, Ad-IFN was given first, when the viral load was still less than the limit of detection of known assays, and then ZMAb was given upon detection of viremia and fever. Two of four macaques survived. Control animals had undetectable levels of IgG, whereas Ebola virus GP–specific IgG levels were detected in all survivors. IFN-gamma ELISpots showed high EBOV-GP–specific T-cell response in all survivors.

ZMapp is another cocktail of monoclonal antibodies, containing two from ZMab (2G4 and 4G7), plus a third, c13C6. In experiments in rhesus macaques, three groups of six animals each received three doses of ZMapp at varying times after being infected with Ebola virus: at 3, 6, and 9 days; at 4, 7, and 10 days, and at 5, 8, and 11 days. All 18 macaques treated with ZMapp survived. Thus, Zmapp extended the treatment window to 5 days postexposure.10 One of the American health care workers who contracted Ebola virus in Liberia received this medication.

HSPA5-PMO. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone heat shock 70 kDa protein 5 (HSPA5) is instrumental in the maturation of envelope proteins in hepatitis C and influenza A virus. It plays a role in viral entry for coxsackievirus A9 and dengue virus serotype 2, and it may be involved in Ebola viral budding. Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) are a class of antisense DNA nucleotide analogs.

Reid et al11 reported that mice treated with HSPA5–PMO were completely protected from lethal Ebola challenge. Therefore, HSPA5 appears to be a promising target for the development of antifilovirus countermeasures.

Favipiravir, an antiviral agent also known as T-705, is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative. Invented in 2002 by Toyama Chemicals as an inhibitor of influenza virus replication, it acts as a nucleotide analog, selectively inhibiting the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, or causes lethal mutagenesis upon incorporation into the virus RNA. Favipiravir suppresses Ebola virus replication by 4 log10 units in cell culture.12

Mice were challenged with intranasal inoculation of 1,000 focus-forming units of Ebola virus diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. Until the first day of treatment (postinfection day 6), all mice in the T-705 group lost weight similarly to control mice, developed viremia, and showed elevated serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. Within 4 days of T-705 treatment (post-infection day 10), the animals had cleared the virus from blood. Surviving mice developed Ebola virus-specific antibodies and CD8+ T cells specific for the viral nucleoprotein.12

The authors hypothesized that suppression of virus replication by T-705 allowed the host to mount a virus-specific adaptive immune response, and concluded that T-705 was 100% effective in the treatment of Zaire Ebola virus infection up to postinfection day 6 but was hardly beneficial at the terminal stage of disease.12 Of note, favipiravir is undergoing phase 2 and phase 3 trials as an anti-influenza agent in Japan.

THE CURRENT OUTBREAK