User login

Consideration of herbal products in pregnancy and lactation

In recent decades, natural products have had increased consumer attention in industrialized nations. One of the challenges is that “natural” can be more of a perception than a standard. “Herbal products” is a more frequently used and perhaps a more apt term. Herbal products come in many forms, including herbs used in food preparation, teas, infusions, caplets, dried extracts, essential oils, and tinctures.

Multiple prescription medications have pharmacologically active compounds that originated from herbal products, both historically and currently. Examples include the cardiac stimulant digoxin (foxglove plant), the antimalarial quinine (Cinchona bark), and antihypertensives (Rauwolfia serpentina). Indeed, the first pharmacologically active compound, morphine, was extracted from the seed pods of opium poppies approximately 200 years ago. This demonstrated that medications could be purified from plants and that a precise dose could be determined for administration. However, herbal products are grown and harvested in varying seasonal conditions and soil types, which, over time and geography, may contribute to variability in the levels of active compound in the final products.

The importance of active compound purification and consistent precise dosage in herbal products brings up the topic of regulation. Herbal products are considered dietary supplements and as such are Food and Drug Administration regulated as a food under the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health Education Act. Regulation as a food product does not involve the same level of scrutiny as a medication. There is no requirement that manufacturers check for purity and consistency of their product’s active compound(s). Manufacturers must ensure that the claims they make about herbal products are not false or misleading. They must also support their claims with evidence. However, there is no requirement for the manufacturers to submit this evidence to the FDA. This can translate into a discrepancy between the claim on the product label and scientific evidence that the product does what it claims to do. In other words, the product may not be effective.

With uncertain efficacy, the safety of herbal products comes into focus. Very few herbal products (or their specific active compounds) have been scientifically studied for safety in pregnancy and lactation. Further, herbal products may contain contaminants. Metals such as lead and mercury occur naturally. Yet, because of human activities, both may have collected in areas where herbal products are grown. From a safety perspective, both can be concerning in pregnancy or lactation. Lead and mercury are two examples of metal contaminants. Other contaminants may include pesticides, chemicals, and bacteria or other microorganisms. Some liquid herbal products such as tinctures contain alcohol, which should be avoided in pregnancy. An additional consideration would be the potential for herbal products, including any of their known or unknown product contents, to interact with prescribed medications or anesthesia.

Select examples of herbal products

Astragalus is the root of an herb and it is used for reasons of boosting immunity, energy, and other functions. These and its purported promotion of breast milk flow (galactagogue) are unsupported. Safety concerns include irregular heartbeat and dizziness, rendering it unsafe for use in pregnancy and of unknown efficacy and safety in lactation.

Kombucha is an herbal product made from leaves (tea), sugar, a culture, and other varying products. Like many herbal products, it is both manufactured and home brewed. It is used for probiotic and antioxidant reasons. As a fermented product, kombucha may contain 0.2%-0.5% alcohol. There is no known safe level of alcohol and no known safe type of alcohol for use in pregnancy. Alcohol exposure in pregnancy can result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, involving a range of birth defects and life-long intellectual, learning and behavioral disorders. Alcohol found in breast milk approximates the level of alcohol found in the maternal bloodstream. Alcohol-containing products should be avoided in pregnancy and lactation.

Nux vomica is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. It comes from the raw seeds (toxic) of an evergreen tree. It has serious safety concerns and yet it is still in use. It contains strychnine, which can harm both the pregnant individual and the developing fetus. It is not recommended in lactation.

Red raspberry leaf is a leaf, brewed and ingested as a tea. It is used for reasons of preventing miscarriage, relieving nausea and stomach discomfort, toning the uterus, reducing labor pain, increasing breast milk production, and other functions. In low doses, it appears to be safe. In high doses, it can induce smooth muscle relaxation. Efficacy has not been demonstrated with labor and delivery or in increasing breast milk production.

Tabacum is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. Its full name is Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) and it contains 2%-8% nicotine, which should be avoided in pregnancy. Nicotine is a health danger for the pregnant individual and can damage a developing fetus’ brain and lungs.

Unless otherwise scientifically demonstrated, herbal products should be considered medications with pharmacologic activity, potential adverse effects, and potential toxicity in pregnancy and lactation. It’s easy for a patient to forget about reporting any nonprescription medications during a patient-provider visit. As a provider, purposefully asking about all over-the-counter and herbal products during each visit can prompt the patient to provide this important information. Further, it may facilitate discussion about the continuation/discontinuation of products of unknown safety and unknown benefit, culminating in the serious reflection: “Is it really worth the risk?”

For further information about the safety of herbal products, consult local Poison Control Centers, MothertoBaby, MothertoBaby affiliates, and the National Institutes of Health Drugs and Lactation Database, LactMed.

Dr. Hardy is a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, and represents the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention and the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists at PRGLAC meetings. Dr. Hardy has worked with multiple pharmaceutical manufacturers regarding studies of medication safety in pregnancy, most recently Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, CT.

.

In recent decades, natural products have had increased consumer attention in industrialized nations. One of the challenges is that “natural” can be more of a perception than a standard. “Herbal products” is a more frequently used and perhaps a more apt term. Herbal products come in many forms, including herbs used in food preparation, teas, infusions, caplets, dried extracts, essential oils, and tinctures.

Multiple prescription medications have pharmacologically active compounds that originated from herbal products, both historically and currently. Examples include the cardiac stimulant digoxin (foxglove plant), the antimalarial quinine (Cinchona bark), and antihypertensives (Rauwolfia serpentina). Indeed, the first pharmacologically active compound, morphine, was extracted from the seed pods of opium poppies approximately 200 years ago. This demonstrated that medications could be purified from plants and that a precise dose could be determined for administration. However, herbal products are grown and harvested in varying seasonal conditions and soil types, which, over time and geography, may contribute to variability in the levels of active compound in the final products.

The importance of active compound purification and consistent precise dosage in herbal products brings up the topic of regulation. Herbal products are considered dietary supplements and as such are Food and Drug Administration regulated as a food under the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health Education Act. Regulation as a food product does not involve the same level of scrutiny as a medication. There is no requirement that manufacturers check for purity and consistency of their product’s active compound(s). Manufacturers must ensure that the claims they make about herbal products are not false or misleading. They must also support their claims with evidence. However, there is no requirement for the manufacturers to submit this evidence to the FDA. This can translate into a discrepancy between the claim on the product label and scientific evidence that the product does what it claims to do. In other words, the product may not be effective.

With uncertain efficacy, the safety of herbal products comes into focus. Very few herbal products (or their specific active compounds) have been scientifically studied for safety in pregnancy and lactation. Further, herbal products may contain contaminants. Metals such as lead and mercury occur naturally. Yet, because of human activities, both may have collected in areas where herbal products are grown. From a safety perspective, both can be concerning in pregnancy or lactation. Lead and mercury are two examples of metal contaminants. Other contaminants may include pesticides, chemicals, and bacteria or other microorganisms. Some liquid herbal products such as tinctures contain alcohol, which should be avoided in pregnancy. An additional consideration would be the potential for herbal products, including any of their known or unknown product contents, to interact with prescribed medications or anesthesia.

Select examples of herbal products

Astragalus is the root of an herb and it is used for reasons of boosting immunity, energy, and other functions. These and its purported promotion of breast milk flow (galactagogue) are unsupported. Safety concerns include irregular heartbeat and dizziness, rendering it unsafe for use in pregnancy and of unknown efficacy and safety in lactation.

Kombucha is an herbal product made from leaves (tea), sugar, a culture, and other varying products. Like many herbal products, it is both manufactured and home brewed. It is used for probiotic and antioxidant reasons. As a fermented product, kombucha may contain 0.2%-0.5% alcohol. There is no known safe level of alcohol and no known safe type of alcohol for use in pregnancy. Alcohol exposure in pregnancy can result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, involving a range of birth defects and life-long intellectual, learning and behavioral disorders. Alcohol found in breast milk approximates the level of alcohol found in the maternal bloodstream. Alcohol-containing products should be avoided in pregnancy and lactation.

Nux vomica is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. It comes from the raw seeds (toxic) of an evergreen tree. It has serious safety concerns and yet it is still in use. It contains strychnine, which can harm both the pregnant individual and the developing fetus. It is not recommended in lactation.

Red raspberry leaf is a leaf, brewed and ingested as a tea. It is used for reasons of preventing miscarriage, relieving nausea and stomach discomfort, toning the uterus, reducing labor pain, increasing breast milk production, and other functions. In low doses, it appears to be safe. In high doses, it can induce smooth muscle relaxation. Efficacy has not been demonstrated with labor and delivery or in increasing breast milk production.

Tabacum is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. Its full name is Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) and it contains 2%-8% nicotine, which should be avoided in pregnancy. Nicotine is a health danger for the pregnant individual and can damage a developing fetus’ brain and lungs.

Unless otherwise scientifically demonstrated, herbal products should be considered medications with pharmacologic activity, potential adverse effects, and potential toxicity in pregnancy and lactation. It’s easy for a patient to forget about reporting any nonprescription medications during a patient-provider visit. As a provider, purposefully asking about all over-the-counter and herbal products during each visit can prompt the patient to provide this important information. Further, it may facilitate discussion about the continuation/discontinuation of products of unknown safety and unknown benefit, culminating in the serious reflection: “Is it really worth the risk?”

For further information about the safety of herbal products, consult local Poison Control Centers, MothertoBaby, MothertoBaby affiliates, and the National Institutes of Health Drugs and Lactation Database, LactMed.

Dr. Hardy is a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, and represents the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention and the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists at PRGLAC meetings. Dr. Hardy has worked with multiple pharmaceutical manufacturers regarding studies of medication safety in pregnancy, most recently Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, CT.

.

In recent decades, natural products have had increased consumer attention in industrialized nations. One of the challenges is that “natural” can be more of a perception than a standard. “Herbal products” is a more frequently used and perhaps a more apt term. Herbal products come in many forms, including herbs used in food preparation, teas, infusions, caplets, dried extracts, essential oils, and tinctures.

Multiple prescription medications have pharmacologically active compounds that originated from herbal products, both historically and currently. Examples include the cardiac stimulant digoxin (foxglove plant), the antimalarial quinine (Cinchona bark), and antihypertensives (Rauwolfia serpentina). Indeed, the first pharmacologically active compound, morphine, was extracted from the seed pods of opium poppies approximately 200 years ago. This demonstrated that medications could be purified from plants and that a precise dose could be determined for administration. However, herbal products are grown and harvested in varying seasonal conditions and soil types, which, over time and geography, may contribute to variability in the levels of active compound in the final products.

The importance of active compound purification and consistent precise dosage in herbal products brings up the topic of regulation. Herbal products are considered dietary supplements and as such are Food and Drug Administration regulated as a food under the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health Education Act. Regulation as a food product does not involve the same level of scrutiny as a medication. There is no requirement that manufacturers check for purity and consistency of their product’s active compound(s). Manufacturers must ensure that the claims they make about herbal products are not false or misleading. They must also support their claims with evidence. However, there is no requirement for the manufacturers to submit this evidence to the FDA. This can translate into a discrepancy between the claim on the product label and scientific evidence that the product does what it claims to do. In other words, the product may not be effective.

With uncertain efficacy, the safety of herbal products comes into focus. Very few herbal products (or their specific active compounds) have been scientifically studied for safety in pregnancy and lactation. Further, herbal products may contain contaminants. Metals such as lead and mercury occur naturally. Yet, because of human activities, both may have collected in areas where herbal products are grown. From a safety perspective, both can be concerning in pregnancy or lactation. Lead and mercury are two examples of metal contaminants. Other contaminants may include pesticides, chemicals, and bacteria or other microorganisms. Some liquid herbal products such as tinctures contain alcohol, which should be avoided in pregnancy. An additional consideration would be the potential for herbal products, including any of their known or unknown product contents, to interact with prescribed medications or anesthesia.

Select examples of herbal products

Astragalus is the root of an herb and it is used for reasons of boosting immunity, energy, and other functions. These and its purported promotion of breast milk flow (galactagogue) are unsupported. Safety concerns include irregular heartbeat and dizziness, rendering it unsafe for use in pregnancy and of unknown efficacy and safety in lactation.

Kombucha is an herbal product made from leaves (tea), sugar, a culture, and other varying products. Like many herbal products, it is both manufactured and home brewed. It is used for probiotic and antioxidant reasons. As a fermented product, kombucha may contain 0.2%-0.5% alcohol. There is no known safe level of alcohol and no known safe type of alcohol for use in pregnancy. Alcohol exposure in pregnancy can result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, involving a range of birth defects and life-long intellectual, learning and behavioral disorders. Alcohol found in breast milk approximates the level of alcohol found in the maternal bloodstream. Alcohol-containing products should be avoided in pregnancy and lactation.

Nux vomica is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. It comes from the raw seeds (toxic) of an evergreen tree. It has serious safety concerns and yet it is still in use. It contains strychnine, which can harm both the pregnant individual and the developing fetus. It is not recommended in lactation.

Red raspberry leaf is a leaf, brewed and ingested as a tea. It is used for reasons of preventing miscarriage, relieving nausea and stomach discomfort, toning the uterus, reducing labor pain, increasing breast milk production, and other functions. In low doses, it appears to be safe. In high doses, it can induce smooth muscle relaxation. Efficacy has not been demonstrated with labor and delivery or in increasing breast milk production.

Tabacum is an herbal product and is used for reasons of reducing nausea or vomiting in pregnancy. Its full name is Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) and it contains 2%-8% nicotine, which should be avoided in pregnancy. Nicotine is a health danger for the pregnant individual and can damage a developing fetus’ brain and lungs.

Unless otherwise scientifically demonstrated, herbal products should be considered medications with pharmacologic activity, potential adverse effects, and potential toxicity in pregnancy and lactation. It’s easy for a patient to forget about reporting any nonprescription medications during a patient-provider visit. As a provider, purposefully asking about all over-the-counter and herbal products during each visit can prompt the patient to provide this important information. Further, it may facilitate discussion about the continuation/discontinuation of products of unknown safety and unknown benefit, culminating in the serious reflection: “Is it really worth the risk?”

For further information about the safety of herbal products, consult local Poison Control Centers, MothertoBaby, MothertoBaby affiliates, and the National Institutes of Health Drugs and Lactation Database, LactMed.

Dr. Hardy is a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, and represents the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention and the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists at PRGLAC meetings. Dr. Hardy has worked with multiple pharmaceutical manufacturers regarding studies of medication safety in pregnancy, most recently Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, CT.

.

Which behavioral health screening tool should you use—and when?

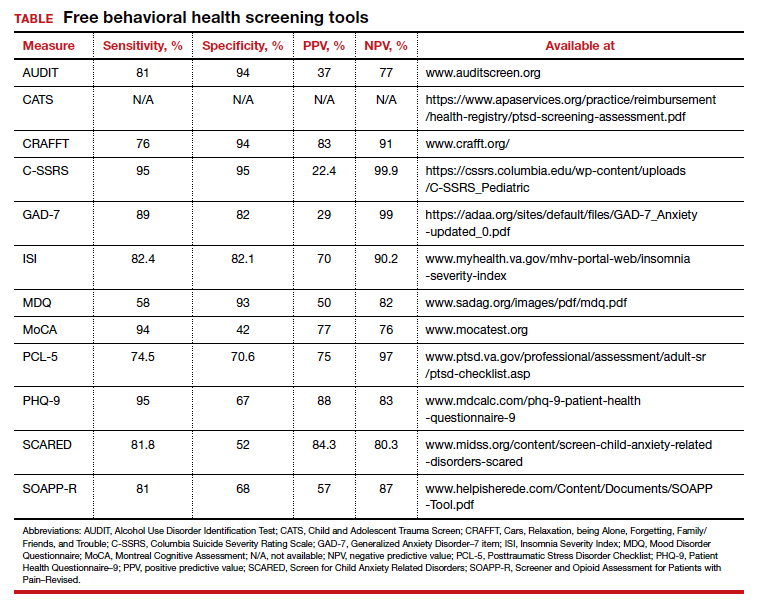

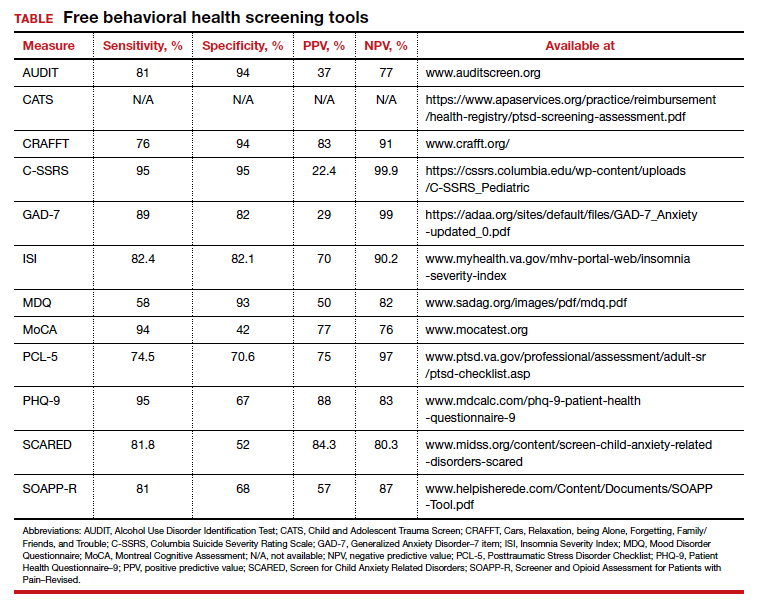

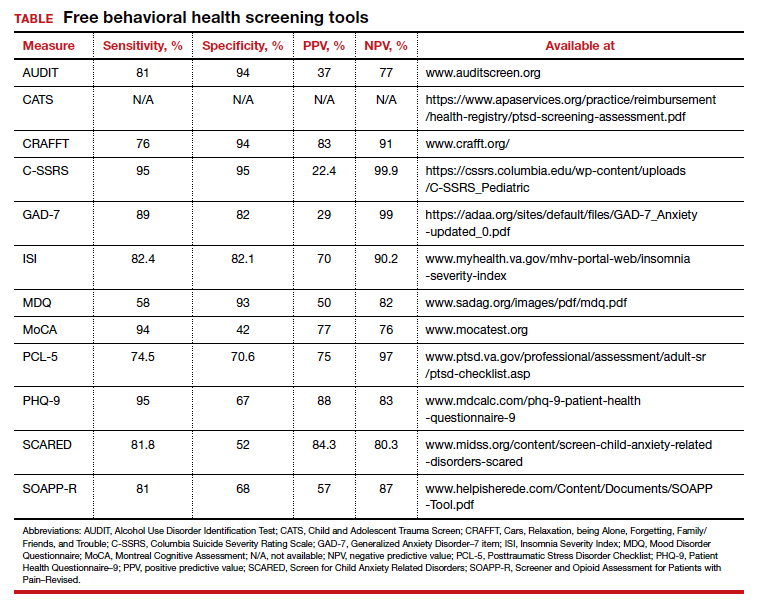

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

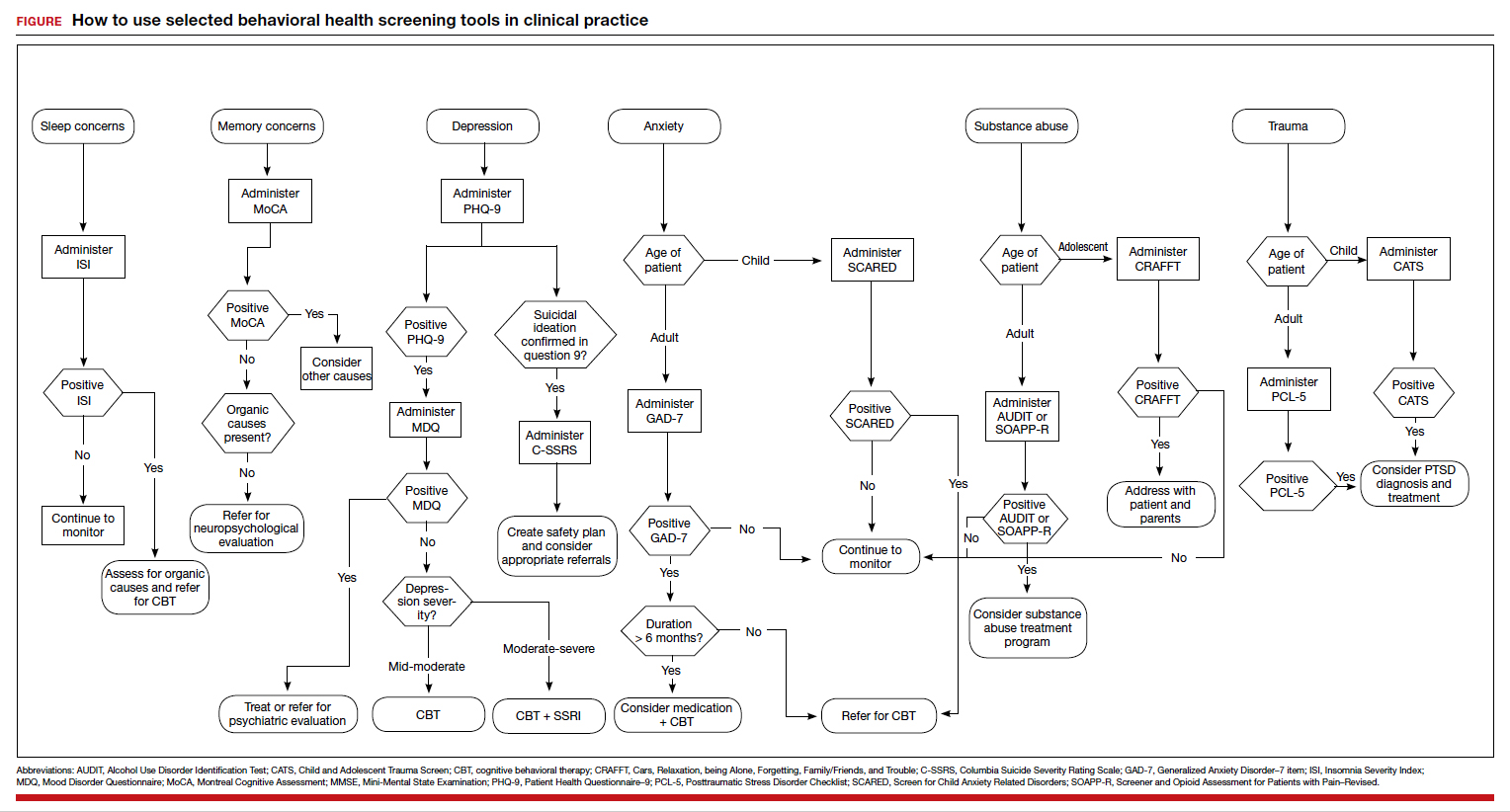

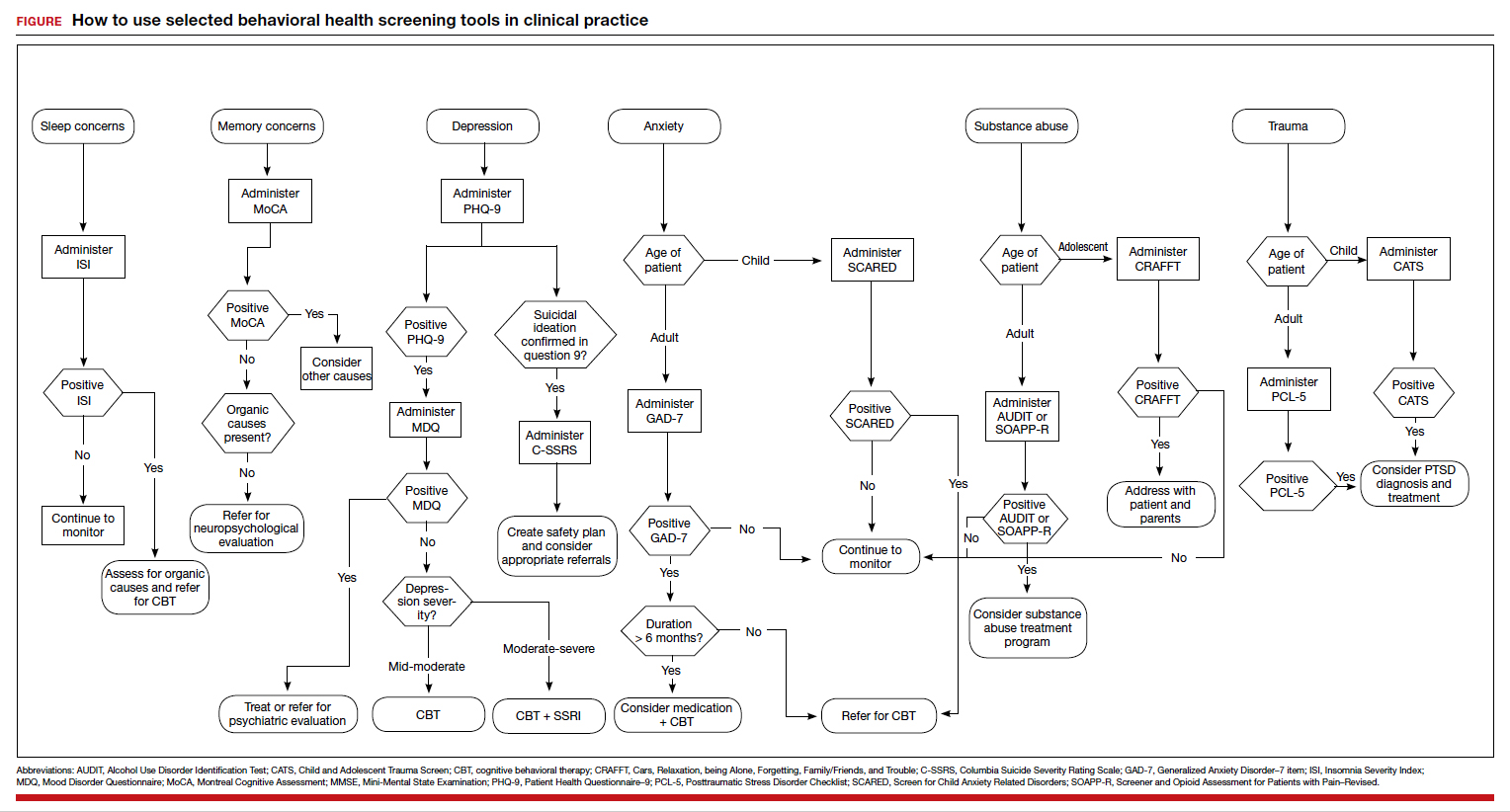

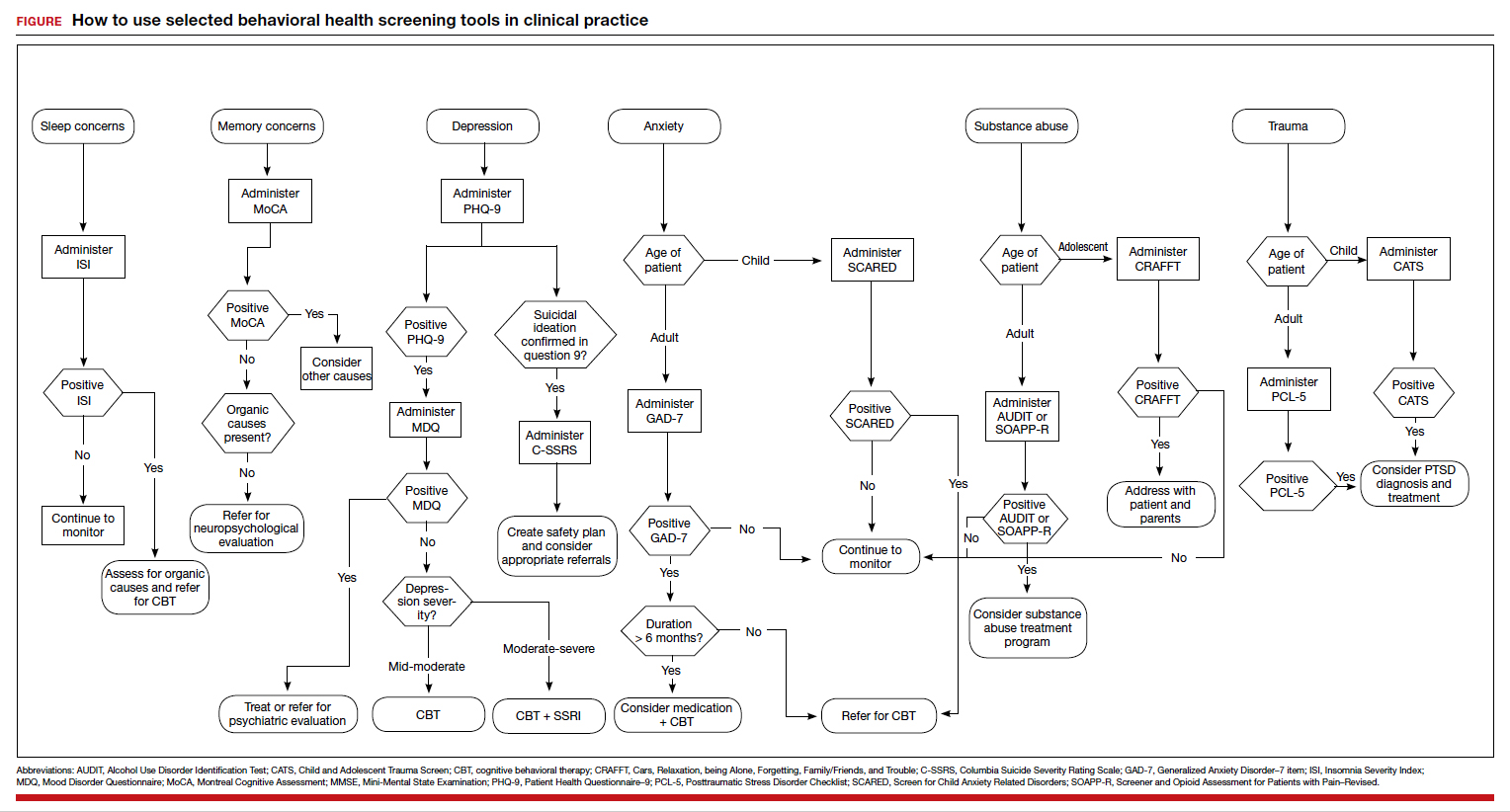

Adapting these screening tools to practice

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.

- DHHS. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetfdf8.html?csid=58&key=P#P. Accessed October 23,2020.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489-498.

- Verhey R, Chilbanda D, Gibson L, et al. Validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:109.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

- Stewart S, O’Riley A, Edelstein B, et al. A preliminary comparison of three cognitive screening instruments in long term care: the MMSE, SLUMS, and MoCA. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:57-75.

- Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke. 2011;42:1712-1716.

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

Adapting these screening tools to practice

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

Adapting these screening tools to practice

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.

- DHHS. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetfdf8.html?csid=58&key=P#P. Accessed October 23,2020.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489-498.

- Verhey R, Chilbanda D, Gibson L, et al. Validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:109.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

- Stewart S, O’Riley A, Edelstein B, et al. A preliminary comparison of three cognitive screening instruments in long term care: the MMSE, SLUMS, and MoCA. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:57-75.

- Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke. 2011;42:1712-1716.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.