User login

ID Blog: Wuhan coronavirus – just a stop on the zoonotic highway

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

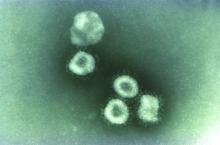

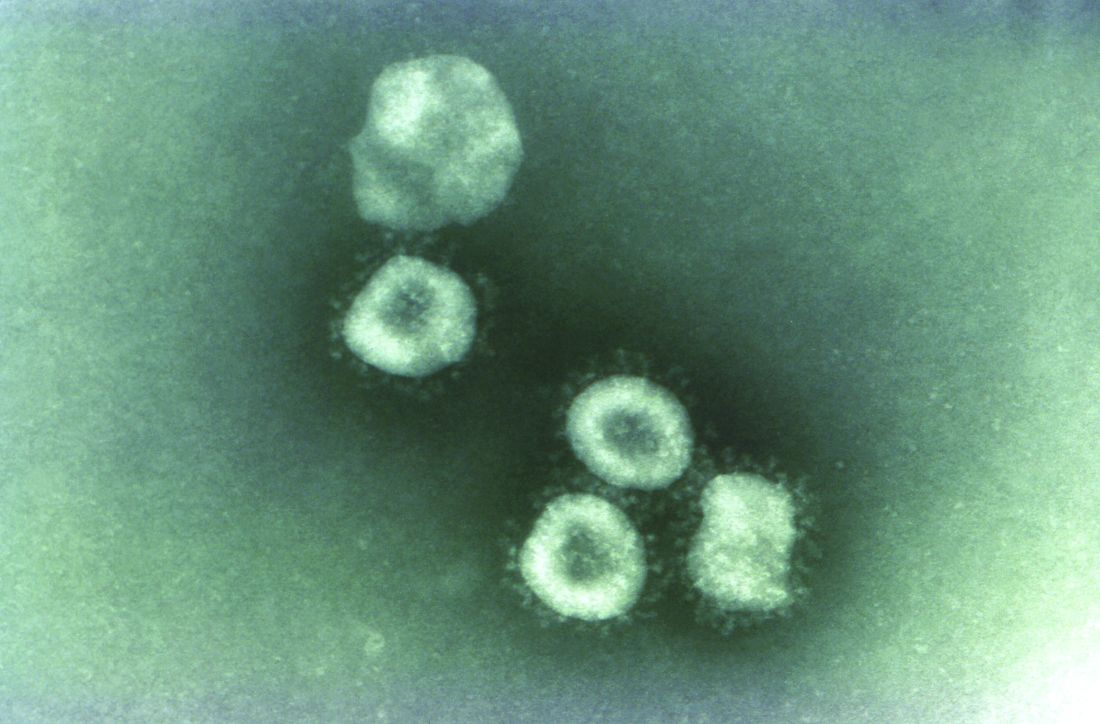

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Wuhan coronavirus cluster suggests human-to-human spread

A Chinese man became ill from a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 4 days after arriving in Vietnam to visit his 27-year-old son. Three days later the healthy young man was also stricken, according to a report published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This family cluster of 2019-nCoV infection that occurred outside China arouses concern regarding human-to-human transmission,” the authors wrote.

The father, age 65 years and with multiple comorbidities including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease with stent placement, and lung cancer, flew to Hanoi with his wife on January 13; they traveled from the Wuchang district in Wuhan, China, where outbreaks of 2019-nCoV have been occurring.

On Jan. 17, the older man and his wife met their adult son in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and shared a hotel room with him for 3 days. The father developed a fever that same day and the son developed a dry cough, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting on Jan. 20. Both men went to a hospital ED on Jan. 22.

The authors say the timing of the son’s symptoms suggests the incubation period may have been 3 days or fewer.

Upon admission to the hospital, the father reported that he had not visited a “wet market” where live and dead animals are sold while he was in Wuhan. Throat swabs were positive for 2019-nCoV on real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction assays.

The man was placed in isolation and “treated empirically with antiviral agents, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and supportive therapies,” wrote Lan T. Phan, PhD, from the Pasteur Institute Ho Chi Minh City and coauthors.

On admission, chest radiographs revealed an infiltrate in the upper lobe of his left lung; he developed worsening dyspnea with hypoxemia on Jan. 25 and required supplemental oxygen at 5 L/min by nasal cannula. Chest radiographs showed a progressive infiltrate and consolidation. His fever resolved on that day and he has progressively improved.

The man’s son had a fever of 39° C (102.2° F) when the two men arrived at the hospital on Jan. 22; hospital staff isolated the son, and chest radiographs and other laboratory tests were normal with the exception of an increased C-reactive protein level.

The son’s throat swab was positive for 2019-nCoV and he is believed to have been exposed from his father; however, the strains have not been ascertained.

“This family had traveled to four cities across Vietnam using various forms of transportation, including planes, trains, and taxis,” the authors wrote. A total of 28 close contacts were identified, none of whom have developed respiratory symptoms. The older man’s wife has been healthy as well.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Chinese man became ill from a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 4 days after arriving in Vietnam to visit his 27-year-old son. Three days later the healthy young man was also stricken, according to a report published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This family cluster of 2019-nCoV infection that occurred outside China arouses concern regarding human-to-human transmission,” the authors wrote.

The father, age 65 years and with multiple comorbidities including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease with stent placement, and lung cancer, flew to Hanoi with his wife on January 13; they traveled from the Wuchang district in Wuhan, China, where outbreaks of 2019-nCoV have been occurring.

On Jan. 17, the older man and his wife met their adult son in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and shared a hotel room with him for 3 days. The father developed a fever that same day and the son developed a dry cough, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting on Jan. 20. Both men went to a hospital ED on Jan. 22.

The authors say the timing of the son’s symptoms suggests the incubation period may have been 3 days or fewer.

Upon admission to the hospital, the father reported that he had not visited a “wet market” where live and dead animals are sold while he was in Wuhan. Throat swabs were positive for 2019-nCoV on real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction assays.

The man was placed in isolation and “treated empirically with antiviral agents, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and supportive therapies,” wrote Lan T. Phan, PhD, from the Pasteur Institute Ho Chi Minh City and coauthors.

On admission, chest radiographs revealed an infiltrate in the upper lobe of his left lung; he developed worsening dyspnea with hypoxemia on Jan. 25 and required supplemental oxygen at 5 L/min by nasal cannula. Chest radiographs showed a progressive infiltrate and consolidation. His fever resolved on that day and he has progressively improved.

The man’s son had a fever of 39° C (102.2° F) when the two men arrived at the hospital on Jan. 22; hospital staff isolated the son, and chest radiographs and other laboratory tests were normal with the exception of an increased C-reactive protein level.

The son’s throat swab was positive for 2019-nCoV and he is believed to have been exposed from his father; however, the strains have not been ascertained.

“This family had traveled to four cities across Vietnam using various forms of transportation, including planes, trains, and taxis,” the authors wrote. A total of 28 close contacts were identified, none of whom have developed respiratory symptoms. The older man’s wife has been healthy as well.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Chinese man became ill from a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 4 days after arriving in Vietnam to visit his 27-year-old son. Three days later the healthy young man was also stricken, according to a report published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This family cluster of 2019-nCoV infection that occurred outside China arouses concern regarding human-to-human transmission,” the authors wrote.

The father, age 65 years and with multiple comorbidities including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease with stent placement, and lung cancer, flew to Hanoi with his wife on January 13; they traveled from the Wuchang district in Wuhan, China, where outbreaks of 2019-nCoV have been occurring.

On Jan. 17, the older man and his wife met their adult son in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and shared a hotel room with him for 3 days. The father developed a fever that same day and the son developed a dry cough, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting on Jan. 20. Both men went to a hospital ED on Jan. 22.

The authors say the timing of the son’s symptoms suggests the incubation period may have been 3 days or fewer.

Upon admission to the hospital, the father reported that he had not visited a “wet market” where live and dead animals are sold while he was in Wuhan. Throat swabs were positive for 2019-nCoV on real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction assays.

The man was placed in isolation and “treated empirically with antiviral agents, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and supportive therapies,” wrote Lan T. Phan, PhD, from the Pasteur Institute Ho Chi Minh City and coauthors.

On admission, chest radiographs revealed an infiltrate in the upper lobe of his left lung; he developed worsening dyspnea with hypoxemia on Jan. 25 and required supplemental oxygen at 5 L/min by nasal cannula. Chest radiographs showed a progressive infiltrate and consolidation. His fever resolved on that day and he has progressively improved.

The man’s son had a fever of 39° C (102.2° F) when the two men arrived at the hospital on Jan. 22; hospital staff isolated the son, and chest radiographs and other laboratory tests were normal with the exception of an increased C-reactive protein level.

The son’s throat swab was positive for 2019-nCoV and he is believed to have been exposed from his father; however, the strains have not been ascertained.

“This family had traveled to four cities across Vietnam using various forms of transportation, including planes, trains, and taxis,” the authors wrote. A total of 28 close contacts were identified, none of whom have developed respiratory symptoms. The older man’s wife has been healthy as well.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Echoes of SARS mark 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

FROM THE LANCET

CDC: Five confirmed 2019-nCoV cases in the U.S.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

Wuhan virus: What clinicians need to know

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

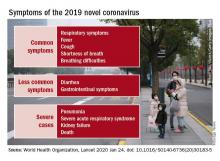

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

If patients exhibit symptoms and either they or a close contact has returned from China recently, take standard airborne precautions and send specimens – a serum sample, oral and nasal pharyngeal swabs, and lower respiratory tract specimens if available – to the local health department, which will forward them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing. Turnaround time is 24-48 hours.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in December in association with a live animal market in Wuhan, China, has been implicated in almost 2,000 cases and 56 deaths in that country. Cases have been reported in 13 countries besides China. Five cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been confirmed in the United States, all in people recently returned from Wuhan. As the virus spreads in China, however, it’s almost certain more cases will show up in the United States. Travel history is key, Dr. Schaffner and others said.

Plan and rehearse

The first step to prepare is to use the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals to make a written plan specific to your practice to respond to a potential case. The plan must include notifying the local health department, the CDC liaison for testing, and tracking down patient contacts.

“It’s not good enough to just download CDC’s guidance; use it to make your own local plan and know what to do 24/7,” said Daniel Lucey, MD, an infectious disease expert at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

“Know who is on call at the health department on weekends and nights,” he said. Know where the patient is going to be isolated; figure out what to do if there’s more than one, and tests come back positive. Have masks on hand, and rehearse the response. “Make a coronavirus team, and absolutely have the nurses involved,” as well as other providers who may come into contact with a case, he added.

“You want to be able to do as well as your counterparts in Washington state and Chicago,” where the first two U.S. cases emerged. “They were prepared. They knew what to do,” Dr. Lucey said.

Those first two U.S. patients – a man in Everett, Wash., and a Chicago woman – developed symptoms after returning from Wuhan, a city of 11 million just over 400 miles inland from the port city of Shanghai. On Jan. 26 three more cases were confirmed by the CDC, two in California and one in Arizona, and each had recently traveled to Wuhan. All five patients remain hospitalized, and there’s no evidence they spread the infection further. There is also no evidence of human-to-human transmission of other cases exported from China to any other countries, according to the WHO.

WHO declined to declare a global health emergency – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in its parlance – on Jan. 23. The step would have triggered travel and trade restrictions in member states, including the United States. For now, at least, the group said it wasn’t warranted at this point.

Fatality rates

The focus right now is China. The outbreak has spread beyond Wuhan to other parts of the country, and there’s evidence of fourth-generation spread.

Transportation into and out of Wuhan and other cities has been curtailed, Lunar New Year festivals have been canceled, and the Shanghai Disneyland has been closed, among other measures taken by Chinese officials.

The government could be taking drastic measures in part to prevent the public criticism it took in the early 2000’s for the delayed response and lack of transparency during the global outbreak of another wildlife market coronavirus epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a press conference Jan. 22, WHO officials commended the government’s containment efforts but did not say they recommended them.

According to WHO, serious cases in China have mostly been in people over 40 years old with significant comorbidities and have skewed towards men. Spread seems to be limited to family members, health care providers, and other close contacts, probably by respiratory droplets. If that pattern holds, WHO officials said, the outbreak is containable.

The fatality rate appears to be around 3%, a good deal lower than the 10% reported for SARS and much lower than the nearly 40% reported for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another recent coronavirus mutation from the animal trade.

The Wuhan virus fatality rate might drop as milder cases are detected and added to the denominator. “It definitely appears to be less severe than SARS and MERS,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease physician in Pittsburgh and emerging infectious disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

SARS: Lessons learned

In general, the world is much better equipped for coronavirus outbreaks than when SARS, in particular, emerged in 2003.

WHO officials in their press conference lauded China for it openness with the current outbreak, and for isolating and sequencing the virus immediately, which gave the world a diagnostic test in the first days of the outbreak, something that wasn’t available for SARS. China and other countries also are cooperating and working closely to contain the Wuhan virus.

“What we know today might change tomorrow, so we have to keep tuned in to new information, but we learned a lot from SARS,” Dr. Shaffner said. Overall, it’s likely “the impact on the United States of this new coronavirus is going to be trivial,” he predicted.

Dr. Lucey, however, recalled that the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003 started with one missed case. A woman returned asymptomatic from Hong Kong and spread the infection to her family members before she died. Her cause of death wasn’t immediately recognized, nor was the reason her family members were sick, since they hadn’t been to Hong Kong recently.

The infection ultimately spread to more than 200 people, about half of them health care workers. A few people died.

If a virus is sufficiently contagious, “it just takes one. You don’t want to be the one who misses that first patient,” Dr. Lucey said.

Currently, there are no antivirals or vaccines for coronaviruses; researchers are working on both, but for now, care is supportive.

This article was updated with new case numbers on 1/26/20.

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

If patients exhibit symptoms and either they or a close contact has returned from China recently, take standard airborne precautions and send specimens – a serum sample, oral and nasal pharyngeal swabs, and lower respiratory tract specimens if available – to the local health department, which will forward them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for testing. Turnaround time is 24-48 hours.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in December in association with a live animal market in Wuhan, China, has been implicated in almost 2,000 cases and 56 deaths in that country. Cases have been reported in 13 countries besides China. Five cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been confirmed in the United States, all in people recently returned from Wuhan. As the virus spreads in China, however, it’s almost certain more cases will show up in the United States. Travel history is key, Dr. Schaffner and others said.

Plan and rehearse

The first step to prepare is to use the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals to make a written plan specific to your practice to respond to a potential case. The plan must include notifying the local health department, the CDC liaison for testing, and tracking down patient contacts.

“It’s not good enough to just download CDC’s guidance; use it to make your own local plan and know what to do 24/7,” said Daniel Lucey, MD, an infectious disease expert at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

“Know who is on call at the health department on weekends and nights,” he said. Know where the patient is going to be isolated; figure out what to do if there’s more than one, and tests come back positive. Have masks on hand, and rehearse the response. “Make a coronavirus team, and absolutely have the nurses involved,” as well as other providers who may come into contact with a case, he added.

“You want to be able to do as well as your counterparts in Washington state and Chicago,” where the first two U.S. cases emerged. “They were prepared. They knew what to do,” Dr. Lucey said.

Those first two U.S. patients – a man in Everett, Wash., and a Chicago woman – developed symptoms after returning from Wuhan, a city of 11 million just over 400 miles inland from the port city of Shanghai. On Jan. 26 three more cases were confirmed by the CDC, two in California and one in Arizona, and each had recently traveled to Wuhan. All five patients remain hospitalized, and there’s no evidence they spread the infection further. There is also no evidence of human-to-human transmission of other cases exported from China to any other countries, according to the WHO.

WHO declined to declare a global health emergency – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in its parlance – on Jan. 23. The step would have triggered travel and trade restrictions in member states, including the United States. For now, at least, the group said it wasn’t warranted at this point.

Fatality rates

The focus right now is China. The outbreak has spread beyond Wuhan to other parts of the country, and there’s evidence of fourth-generation spread.

Transportation into and out of Wuhan and other cities has been curtailed, Lunar New Year festivals have been canceled, and the Shanghai Disneyland has been closed, among other measures taken by Chinese officials.

The government could be taking drastic measures in part to prevent the public criticism it took in the early 2000’s for the delayed response and lack of transparency during the global outbreak of another wildlife market coronavirus epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a press conference Jan. 22, WHO officials commended the government’s containment efforts but did not say they recommended them.

According to WHO, serious cases in China have mostly been in people over 40 years old with significant comorbidities and have skewed towards men. Spread seems to be limited to family members, health care providers, and other close contacts, probably by respiratory droplets. If that pattern holds, WHO officials said, the outbreak is containable.

The fatality rate appears to be around 3%, a good deal lower than the 10% reported for SARS and much lower than the nearly 40% reported for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), another recent coronavirus mutation from the animal trade.

The Wuhan virus fatality rate might drop as milder cases are detected and added to the denominator. “It definitely appears to be less severe than SARS and MERS,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease physician in Pittsburgh and emerging infectious disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

SARS: Lessons learned

In general, the world is much better equipped for coronavirus outbreaks than when SARS, in particular, emerged in 2003.

WHO officials in their press conference lauded China for it openness with the current outbreak, and for isolating and sequencing the virus immediately, which gave the world a diagnostic test in the first days of the outbreak, something that wasn’t available for SARS. China and other countries also are cooperating and working closely to contain the Wuhan virus.

“What we know today might change tomorrow, so we have to keep tuned in to new information, but we learned a lot from SARS,” Dr. Shaffner said. Overall, it’s likely “the impact on the United States of this new coronavirus is going to be trivial,” he predicted.

Dr. Lucey, however, recalled that the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003 started with one missed case. A woman returned asymptomatic from Hong Kong and spread the infection to her family members before she died. Her cause of death wasn’t immediately recognized, nor was the reason her family members were sick, since they hadn’t been to Hong Kong recently.

The infection ultimately spread to more than 200 people, about half of them health care workers. A few people died.

If a virus is sufficiently contagious, “it just takes one. You don’t want to be the one who misses that first patient,” Dr. Lucey said.

Currently, there are no antivirals or vaccines for coronaviruses; researchers are working on both, but for now, care is supportive.

This article was updated with new case numbers on 1/26/20.

As the Wuhan coronavirus story unfolds, , according to infectious disease experts.

“We are asking that of everyone with fever and respiratory symptoms who comes to our clinics, hospital, or emergency room. It’s a powerful screening tool,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

In addition to fever, common signs of infection include cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Some patients have had diarrhea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In more severe cases, infection can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and death. The incubation period appears to be up to 2 weeks, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).