User login

Better control of asymptomatic C. difficile needed in communities

Clostridium difficile is transmitted at higher rates in hospitals or long-term care facilities than in community settings, but more efforts need to be directed at reducing community transmission of the infection, report David P. Durham, Ph.D., and his associates.

Hospitalized symptomatic patients transmit C. difficile at a rate 15 times that of patients who are asymptomatic, according to a model created from U.S. national databases described in the paper. Long-term care facility (LTCF) residents transmit C. difficile at a rate of 27% that of hospitalized patients, while people in the community transmit the infection at a rate of less than 0.1% that of hospitalized patients, the model found.

“Despite the lower community transmission rate, we found that because of the much larger pool of colonized persons in the community, interventions that reduce community transmission hold substantial potential to reduce hospital-onset C. difficile infection by reducing the number of patients entering the hospital with asymptomatic colonization,” reported Dr. Durham, associate research scientist in epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his associates.

The researchers also estimated the effect of transmission-control interventions on C. difficile incidence by computing the percentage reduction in hospital-onset C. difficile, community-onset C. difficile, and LTCF C. difficile per percentage in improvement in hospital C. difficile diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation protocols, overall hospital hygiene, transmission in the community, and transmission in an LTCF.

“We found that C. difficile infection diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation, overall hospital hygiene, and transmission in the community, but not transmission in an LTCF, affected hospital-onset C. difficile infection,” the researchers wrote. “In addition, community-onset C. difficile infection and LTCF C. difficile infection were not affected by hospital-based transmission interventions.”

Additionally, as the relative risk for antimicrobial drug class prescribed increased in each of the three settings, the C. difficile incidence increased within the respective setting.

The researchers suggested that the use of vaccines and other toxin-targeting treatments, nontoxigenic C. difficile, and monoclonal antibodies could lead to reductions in primary C. difficile cases and transmission of the infection.

“These results underscore the need for empirical quantification of community-associated transmission and the need of understanding transmission dynamics in all settings when evaluating C. difficile interventions and control strategies,” researchers said.

Read the study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.3201.eid2204.1540455).

Clostridium difficile is transmitted at higher rates in hospitals or long-term care facilities than in community settings, but more efforts need to be directed at reducing community transmission of the infection, report David P. Durham, Ph.D., and his associates.

Hospitalized symptomatic patients transmit C. difficile at a rate 15 times that of patients who are asymptomatic, according to a model created from U.S. national databases described in the paper. Long-term care facility (LTCF) residents transmit C. difficile at a rate of 27% that of hospitalized patients, while people in the community transmit the infection at a rate of less than 0.1% that of hospitalized patients, the model found.

“Despite the lower community transmission rate, we found that because of the much larger pool of colonized persons in the community, interventions that reduce community transmission hold substantial potential to reduce hospital-onset C. difficile infection by reducing the number of patients entering the hospital with asymptomatic colonization,” reported Dr. Durham, associate research scientist in epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his associates.

The researchers also estimated the effect of transmission-control interventions on C. difficile incidence by computing the percentage reduction in hospital-onset C. difficile, community-onset C. difficile, and LTCF C. difficile per percentage in improvement in hospital C. difficile diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation protocols, overall hospital hygiene, transmission in the community, and transmission in an LTCF.

“We found that C. difficile infection diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation, overall hospital hygiene, and transmission in the community, but not transmission in an LTCF, affected hospital-onset C. difficile infection,” the researchers wrote. “In addition, community-onset C. difficile infection and LTCF C. difficile infection were not affected by hospital-based transmission interventions.”

Additionally, as the relative risk for antimicrobial drug class prescribed increased in each of the three settings, the C. difficile incidence increased within the respective setting.

The researchers suggested that the use of vaccines and other toxin-targeting treatments, nontoxigenic C. difficile, and monoclonal antibodies could lead to reductions in primary C. difficile cases and transmission of the infection.

“These results underscore the need for empirical quantification of community-associated transmission and the need of understanding transmission dynamics in all settings when evaluating C. difficile interventions and control strategies,” researchers said.

Read the study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.3201.eid2204.1540455).

Clostridium difficile is transmitted at higher rates in hospitals or long-term care facilities than in community settings, but more efforts need to be directed at reducing community transmission of the infection, report David P. Durham, Ph.D., and his associates.

Hospitalized symptomatic patients transmit C. difficile at a rate 15 times that of patients who are asymptomatic, according to a model created from U.S. national databases described in the paper. Long-term care facility (LTCF) residents transmit C. difficile at a rate of 27% that of hospitalized patients, while people in the community transmit the infection at a rate of less than 0.1% that of hospitalized patients, the model found.

“Despite the lower community transmission rate, we found that because of the much larger pool of colonized persons in the community, interventions that reduce community transmission hold substantial potential to reduce hospital-onset C. difficile infection by reducing the number of patients entering the hospital with asymptomatic colonization,” reported Dr. Durham, associate research scientist in epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his associates.

The researchers also estimated the effect of transmission-control interventions on C. difficile incidence by computing the percentage reduction in hospital-onset C. difficile, community-onset C. difficile, and LTCF C. difficile per percentage in improvement in hospital C. difficile diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation protocols, overall hospital hygiene, transmission in the community, and transmission in an LTCF.

“We found that C. difficile infection diagnosis rate, effectiveness of isolation, overall hospital hygiene, and transmission in the community, but not transmission in an LTCF, affected hospital-onset C. difficile infection,” the researchers wrote. “In addition, community-onset C. difficile infection and LTCF C. difficile infection were not affected by hospital-based transmission interventions.”

Additionally, as the relative risk for antimicrobial drug class prescribed increased in each of the three settings, the C. difficile incidence increased within the respective setting.

The researchers suggested that the use of vaccines and other toxin-targeting treatments, nontoxigenic C. difficile, and monoclonal antibodies could lead to reductions in primary C. difficile cases and transmission of the infection.

“These results underscore the need for empirical quantification of community-associated transmission and the need of understanding transmission dynamics in all settings when evaluating C. difficile interventions and control strategies,” researchers said.

Read the study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.3201.eid2204.1540455).

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

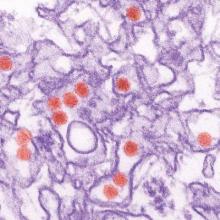

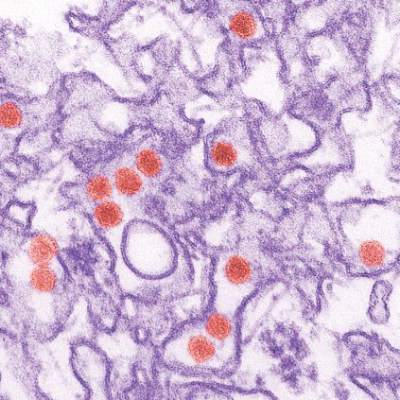

Study links microcephaly to first trimester Zika infection

A new analysis of the Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia supports the theory that infection during the first trimester of pregnancy poses the greatest risk of the fetus developing microcephaly.

Researchers examined serological and surveillance data from a Zika outbreak in French Polynesia that lasted from October 2013 to April 2014, and searched medical records to identify cases of microcephaly diagnosed between September 2013 and July 2015. Of 8,750 suspected Zika virus infections, 383 (4.4%) were confirmed in the laboratory. There were a total of eight cases of microcephaly among pregnant women with Zika virus during the study period, including three live births, reported Simon Cauchemez, Ph.D., of Institut Pasteur, Paris, and colleagues.

Of those eight cases, all but one occurred during the four-month period from March 1 to July 10, 2014, leading researchers to suspect that the period of risk was during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Using a mathematical and statistical model that used the first trimester as the period of risk during pregnancy, the risk of microcephaly was 95 cases per 10,000 women infected during the first trimester for a risk ratio of 53.4 (95% CI 6.5-1061.2). The baseline prevalence was two cases per 10,000 neonates.

Though the researchers could not rule out an increased risk of microcephaly in other trimesters, the first trimester risk model was the best fit, they reported (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6).

The researchers estimated that the risk of microcephaly in the first trimester was about 1%, which is low compared to other viral infections associated with birth defects such as cytomegalovirus or congenital rubella syndrome. But the high incidence of Zika virus in the general population – reaching 66% in French Polynesia at the end of the outbreak – is a cause for concern.

“Although infection with Zika virus is associated with a low fetal risk, it is an important public health issue,” the researchers wrote. “No treatment is available for Zika virus and development of a vaccine will take time. Our findings highlight the need to inform pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant to protect themselves from mosquito bites and avoid travel to affected countries as far as possible.”

The study was supported by the French government, the National Institutes of Health, the AXA Research fund, and the European Union. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The finding that the highest risk of microcephaly was associated with infection in the first trimester of pregnancy is biologically plausible, given the timing of brain development and the type and severity of the neurological abnormalities.

The risk estimate in this study is lower than that found in other studies, but are they consistent with a single underlying risk or, alternatively, will risk be dependent on other factors, such as the presence of clinical symptoms or previous dengue infection? Further data will soon be available from Pernambuco, Colombia, Rio de Janeiro, and maybe other sites that will gradually answer these questions.

Dr. Laura C Rodrigues is from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group in Recife, Brazil. Her comments are adapted from an editorial (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00742-X). She reported having no financial disclosures.

The finding that the highest risk of microcephaly was associated with infection in the first trimester of pregnancy is biologically plausible, given the timing of brain development and the type and severity of the neurological abnormalities.

The risk estimate in this study is lower than that found in other studies, but are they consistent with a single underlying risk or, alternatively, will risk be dependent on other factors, such as the presence of clinical symptoms or previous dengue infection? Further data will soon be available from Pernambuco, Colombia, Rio de Janeiro, and maybe other sites that will gradually answer these questions.

Dr. Laura C Rodrigues is from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group in Recife, Brazil. Her comments are adapted from an editorial (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00742-X). She reported having no financial disclosures.

The finding that the highest risk of microcephaly was associated with infection in the first trimester of pregnancy is biologically plausible, given the timing of brain development and the type and severity of the neurological abnormalities.

The risk estimate in this study is lower than that found in other studies, but are they consistent with a single underlying risk or, alternatively, will risk be dependent on other factors, such as the presence of clinical symptoms or previous dengue infection? Further data will soon be available from Pernambuco, Colombia, Rio de Janeiro, and maybe other sites that will gradually answer these questions.

Dr. Laura C Rodrigues is from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group in Recife, Brazil. Her comments are adapted from an editorial (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00742-X). She reported having no financial disclosures.

A new analysis of the Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia supports the theory that infection during the first trimester of pregnancy poses the greatest risk of the fetus developing microcephaly.

Researchers examined serological and surveillance data from a Zika outbreak in French Polynesia that lasted from October 2013 to April 2014, and searched medical records to identify cases of microcephaly diagnosed between September 2013 and July 2015. Of 8,750 suspected Zika virus infections, 383 (4.4%) were confirmed in the laboratory. There were a total of eight cases of microcephaly among pregnant women with Zika virus during the study period, including three live births, reported Simon Cauchemez, Ph.D., of Institut Pasteur, Paris, and colleagues.

Of those eight cases, all but one occurred during the four-month period from March 1 to July 10, 2014, leading researchers to suspect that the period of risk was during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Using a mathematical and statistical model that used the first trimester as the period of risk during pregnancy, the risk of microcephaly was 95 cases per 10,000 women infected during the first trimester for a risk ratio of 53.4 (95% CI 6.5-1061.2). The baseline prevalence was two cases per 10,000 neonates.

Though the researchers could not rule out an increased risk of microcephaly in other trimesters, the first trimester risk model was the best fit, they reported (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6).

The researchers estimated that the risk of microcephaly in the first trimester was about 1%, which is low compared to other viral infections associated with birth defects such as cytomegalovirus or congenital rubella syndrome. But the high incidence of Zika virus in the general population – reaching 66% in French Polynesia at the end of the outbreak – is a cause for concern.

“Although infection with Zika virus is associated with a low fetal risk, it is an important public health issue,” the researchers wrote. “No treatment is available for Zika virus and development of a vaccine will take time. Our findings highlight the need to inform pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant to protect themselves from mosquito bites and avoid travel to affected countries as far as possible.”

The study was supported by the French government, the National Institutes of Health, the AXA Research fund, and the European Union. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

A new analysis of the Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia supports the theory that infection during the first trimester of pregnancy poses the greatest risk of the fetus developing microcephaly.

Researchers examined serological and surveillance data from a Zika outbreak in French Polynesia that lasted from October 2013 to April 2014, and searched medical records to identify cases of microcephaly diagnosed between September 2013 and July 2015. Of 8,750 suspected Zika virus infections, 383 (4.4%) were confirmed in the laboratory. There were a total of eight cases of microcephaly among pregnant women with Zika virus during the study period, including three live births, reported Simon Cauchemez, Ph.D., of Institut Pasteur, Paris, and colleagues.

Of those eight cases, all but one occurred during the four-month period from March 1 to July 10, 2014, leading researchers to suspect that the period of risk was during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Using a mathematical and statistical model that used the first trimester as the period of risk during pregnancy, the risk of microcephaly was 95 cases per 10,000 women infected during the first trimester for a risk ratio of 53.4 (95% CI 6.5-1061.2). The baseline prevalence was two cases per 10,000 neonates.

Though the researchers could not rule out an increased risk of microcephaly in other trimesters, the first trimester risk model was the best fit, they reported (The Lancet. 2016 March 15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6).

The researchers estimated that the risk of microcephaly in the first trimester was about 1%, which is low compared to other viral infections associated with birth defects such as cytomegalovirus or congenital rubella syndrome. But the high incidence of Zika virus in the general population – reaching 66% in French Polynesia at the end of the outbreak – is a cause for concern.

“Although infection with Zika virus is associated with a low fetal risk, it is an important public health issue,” the researchers wrote. “No treatment is available for Zika virus and development of a vaccine will take time. Our findings highlight the need to inform pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant to protect themselves from mosquito bites and avoid travel to affected countries as far as possible.”

The study was supported by the French government, the National Institutes of Health, the AXA Research fund, and the European Union. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Infection with Zika virus during the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with a significant increase in the risk of microcephaly in the fetus.

Major finding: The researchers estimated that risk of microcephaly in women infected with Zika virus in the first trimester was 95 cases per 10,000 women infected.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of the 2013-2014 Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the French government, the National Institutes of Health, the AXA Research fund, and the European Union. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Severe dengue fever outcomes predicted via metabolomics

The progression of dengue fever into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome can be predicted by analyzing patient serum for metabolites associated with dengue virus infection, a proof of concept study suggests.

Researchers led by Natalia V. Voge, Ph.D., of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, said that because dengue fever had the potential to develop into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), “the ability to predict these severe outcomes using acute phase clinical specimens would be of enormous value to physicians and health care workers for appropriate triaging of patients for clinical management” (PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004449).

Advances in the field of metabolomics provided new opportunities to identify host small molecule biomarkers (SMBs) in acute phase clinical specimens that differentiate dengue disease outcomes, they said.

Collaborating with colleagues from the University of California, Berkeley, the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, and the University of Yucatan, Mexico, the researchers used liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry to analyze 88 serum samples from Nicaraguan pediatric patients with diagnosed DHF/DSS or ND, and 101 serum samples from pediatric and adult Mexican patients.

In the Nicaraguan samples, the researchers identified metabolites that were associated with and differentiated DHF/DSS, DF, and non-dengue febrile illness outcomes, primary and secondary virus infections, and infections with different dengue virus serotypes.

“These metabolites provide insights into metabolic pathways that play roles in dengue virus infection, replication, and pathogenesis,” they wrote.

For instance, some were associated with “lipid metabolism and regulation of inflammatory processes controlled by signaling fatty acids and phospholipids, and others with endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular barrier function.”

The findings were not seen in the Mexican samples, which Dr. Voge and her associates said could reflect the diversity of the disease and the Mexican patients, who had a larger age distribution, compared with the pediatric Nicaraguan population.

Nevertheless, their results provided a proof of concept that “differential perturbation of the serum metabolome” is associated with different dengue infections and disease outcomes, they said.

Dr. Voge and her associates cautioned that while the results were encouraging, they were based on a small sample size and additional studies would be needed to confirm the results.

The findings were restricted to pediatric Nicaraguan patients and the same metabolites may not be predictive of progression to DHF/DSS in adult Nicaraguan patients or in patients from other geographic, genetic, and environmental backgrounds, they added.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants.

The progression of dengue fever into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome can be predicted by analyzing patient serum for metabolites associated with dengue virus infection, a proof of concept study suggests.

Researchers led by Natalia V. Voge, Ph.D., of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, said that because dengue fever had the potential to develop into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), “the ability to predict these severe outcomes using acute phase clinical specimens would be of enormous value to physicians and health care workers for appropriate triaging of patients for clinical management” (PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004449).

Advances in the field of metabolomics provided new opportunities to identify host small molecule biomarkers (SMBs) in acute phase clinical specimens that differentiate dengue disease outcomes, they said.

Collaborating with colleagues from the University of California, Berkeley, the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, and the University of Yucatan, Mexico, the researchers used liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry to analyze 88 serum samples from Nicaraguan pediatric patients with diagnosed DHF/DSS or ND, and 101 serum samples from pediatric and adult Mexican patients.

In the Nicaraguan samples, the researchers identified metabolites that were associated with and differentiated DHF/DSS, DF, and non-dengue febrile illness outcomes, primary and secondary virus infections, and infections with different dengue virus serotypes.

“These metabolites provide insights into metabolic pathways that play roles in dengue virus infection, replication, and pathogenesis,” they wrote.

For instance, some were associated with “lipid metabolism and regulation of inflammatory processes controlled by signaling fatty acids and phospholipids, and others with endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular barrier function.”

The findings were not seen in the Mexican samples, which Dr. Voge and her associates said could reflect the diversity of the disease and the Mexican patients, who had a larger age distribution, compared with the pediatric Nicaraguan population.

Nevertheless, their results provided a proof of concept that “differential perturbation of the serum metabolome” is associated with different dengue infections and disease outcomes, they said.

Dr. Voge and her associates cautioned that while the results were encouraging, they were based on a small sample size and additional studies would be needed to confirm the results.

The findings were restricted to pediatric Nicaraguan patients and the same metabolites may not be predictive of progression to DHF/DSS in adult Nicaraguan patients or in patients from other geographic, genetic, and environmental backgrounds, they added.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants.

The progression of dengue fever into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome can be predicted by analyzing patient serum for metabolites associated with dengue virus infection, a proof of concept study suggests.

Researchers led by Natalia V. Voge, Ph.D., of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, said that because dengue fever had the potential to develop into life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), “the ability to predict these severe outcomes using acute phase clinical specimens would be of enormous value to physicians and health care workers for appropriate triaging of patients for clinical management” (PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004449).

Advances in the field of metabolomics provided new opportunities to identify host small molecule biomarkers (SMBs) in acute phase clinical specimens that differentiate dengue disease outcomes, they said.

Collaborating with colleagues from the University of California, Berkeley, the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, and the University of Yucatan, Mexico, the researchers used liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry to analyze 88 serum samples from Nicaraguan pediatric patients with diagnosed DHF/DSS or ND, and 101 serum samples from pediatric and adult Mexican patients.

In the Nicaraguan samples, the researchers identified metabolites that were associated with and differentiated DHF/DSS, DF, and non-dengue febrile illness outcomes, primary and secondary virus infections, and infections with different dengue virus serotypes.

“These metabolites provide insights into metabolic pathways that play roles in dengue virus infection, replication, and pathogenesis,” they wrote.

For instance, some were associated with “lipid metabolism and regulation of inflammatory processes controlled by signaling fatty acids and phospholipids, and others with endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular barrier function.”

The findings were not seen in the Mexican samples, which Dr. Voge and her associates said could reflect the diversity of the disease and the Mexican patients, who had a larger age distribution, compared with the pediatric Nicaraguan population.

Nevertheless, their results provided a proof of concept that “differential perturbation of the serum metabolome” is associated with different dengue infections and disease outcomes, they said.

Dr. Voge and her associates cautioned that while the results were encouraging, they were based on a small sample size and additional studies would be needed to confirm the results.

The findings were restricted to pediatric Nicaraguan patients and the same metabolites may not be predictive of progression to DHF/DSS in adult Nicaraguan patients or in patients from other geographic, genetic, and environmental backgrounds, they added.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants.

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES

Key clinical point: The life-threatening outcomes of dengue fever could be predicted by identifying host small biomarkers in patient serum.

Major finding: The researchers identified metabolites that were associated with and differentiated dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), dengue fever (DF), and non-dengue febrile illness (ND) outcomes, primary and secondary virus infections, and infections with different dengue virus serotypes.

Data source: A total of 88 serum samples from Nicaraguan pediatric patients with diagnosed DHF/DSS or ND, and 101 serum samples from pediatric and adult Mexican patients.

Disclosures: The research was supported by National Institute of Health grants.

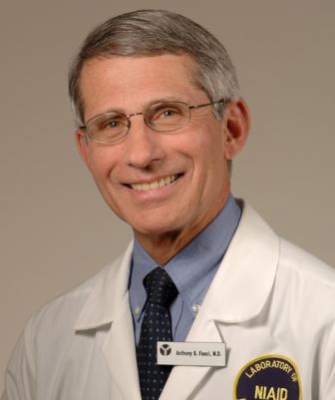

Zika vaccine candidates possible by early 2017

Phase I trials to determine the safety and immunogenicity of a Zika virus vaccine could begin as soon as late summer or early fall of this year, with a candidate vaccine by early 2017.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, made the announcement during a call with the media on March 10, stating that finding a vaccine to combat the increasingly problematic spread of the Zika virus is a top priority of federal health agencies.

Phase I trials “usually take several months – 3 or 4 months – to get an answer,” said Dr. Fauci, adding that he hopes to have “a candidate or candidates that are safe and can induce an immune response” by early 2017.

Dr. Fauci said that he hopes the vaccine could be selected for an accelerated approval schedule so that it could be manufactured and distributed as quickly as possible. That will, however, depend in large part on the state of the Zika virus outbreak in early 2017, a situation he called “impossible to predict.”

“What I can tell you is that we’ll be testing the vaccine in phase I [by] the early fall,” Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, echoed Dr. Fauci’s concerns about the growing Zika virus outbreak in the Americas.

Having just returned from a trip to Puerto Rico, Dr. Frieden said he is “very concerned that, before the year is out, we could see hundreds of thousands of Zika infections in Puerto Rico, and thousands of infected pregnant women.”

Health officials, however, are making progress. The CDC and the NIH are closer than ever to understanding the links between Zika virus and the neurological conditions that have been associated with the virus, including microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

“Never before have we had a mosquito-borne infection that could cause serious birth defects on a large scale,” Dr. Frieden said, adding that “funding from Congress is urgently needed” to adequately attack the growing threat.

Another approach being targeted to fight the Zika virus is controlling the way it is spread – through mosquitoes. To that end, Dr. Frieden outlined a four-pronged approach to reduce exposure to mosquitoes “inside the home, outside the home, at the larval stage, and at the adult mosquito stage,” including using insect repellents and wearing long-sleeve shirts and pants.

“The bottom line here is that [this] is an uphill battle,” Dr. Frieden said. “We know we won’t be able to protect 100% of women, but for every single case of Zika infection in pregnancy we prevent, we’re potentially preventing an individual, personal, and family tragedy.”

Phase I trials to determine the safety and immunogenicity of a Zika virus vaccine could begin as soon as late summer or early fall of this year, with a candidate vaccine by early 2017.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, made the announcement during a call with the media on March 10, stating that finding a vaccine to combat the increasingly problematic spread of the Zika virus is a top priority of federal health agencies.

Phase I trials “usually take several months – 3 or 4 months – to get an answer,” said Dr. Fauci, adding that he hopes to have “a candidate or candidates that are safe and can induce an immune response” by early 2017.

Dr. Fauci said that he hopes the vaccine could be selected for an accelerated approval schedule so that it could be manufactured and distributed as quickly as possible. That will, however, depend in large part on the state of the Zika virus outbreak in early 2017, a situation he called “impossible to predict.”

“What I can tell you is that we’ll be testing the vaccine in phase I [by] the early fall,” Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, echoed Dr. Fauci’s concerns about the growing Zika virus outbreak in the Americas.

Having just returned from a trip to Puerto Rico, Dr. Frieden said he is “very concerned that, before the year is out, we could see hundreds of thousands of Zika infections in Puerto Rico, and thousands of infected pregnant women.”

Health officials, however, are making progress. The CDC and the NIH are closer than ever to understanding the links between Zika virus and the neurological conditions that have been associated with the virus, including microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

“Never before have we had a mosquito-borne infection that could cause serious birth defects on a large scale,” Dr. Frieden said, adding that “funding from Congress is urgently needed” to adequately attack the growing threat.

Another approach being targeted to fight the Zika virus is controlling the way it is spread – through mosquitoes. To that end, Dr. Frieden outlined a four-pronged approach to reduce exposure to mosquitoes “inside the home, outside the home, at the larval stage, and at the adult mosquito stage,” including using insect repellents and wearing long-sleeve shirts and pants.

“The bottom line here is that [this] is an uphill battle,” Dr. Frieden said. “We know we won’t be able to protect 100% of women, but for every single case of Zika infection in pregnancy we prevent, we’re potentially preventing an individual, personal, and family tragedy.”

Phase I trials to determine the safety and immunogenicity of a Zika virus vaccine could begin as soon as late summer or early fall of this year, with a candidate vaccine by early 2017.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, made the announcement during a call with the media on March 10, stating that finding a vaccine to combat the increasingly problematic spread of the Zika virus is a top priority of federal health agencies.

Phase I trials “usually take several months – 3 or 4 months – to get an answer,” said Dr. Fauci, adding that he hopes to have “a candidate or candidates that are safe and can induce an immune response” by early 2017.

Dr. Fauci said that he hopes the vaccine could be selected for an accelerated approval schedule so that it could be manufactured and distributed as quickly as possible. That will, however, depend in large part on the state of the Zika virus outbreak in early 2017, a situation he called “impossible to predict.”

“What I can tell you is that we’ll be testing the vaccine in phase I [by] the early fall,” Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, echoed Dr. Fauci’s concerns about the growing Zika virus outbreak in the Americas.

Having just returned from a trip to Puerto Rico, Dr. Frieden said he is “very concerned that, before the year is out, we could see hundreds of thousands of Zika infections in Puerto Rico, and thousands of infected pregnant women.”

Health officials, however, are making progress. The CDC and the NIH are closer than ever to understanding the links between Zika virus and the neurological conditions that have been associated with the virus, including microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

“Never before have we had a mosquito-borne infection that could cause serious birth defects on a large scale,” Dr. Frieden said, adding that “funding from Congress is urgently needed” to adequately attack the growing threat.

Another approach being targeted to fight the Zika virus is controlling the way it is spread – through mosquitoes. To that end, Dr. Frieden outlined a four-pronged approach to reduce exposure to mosquitoes “inside the home, outside the home, at the larval stage, and at the adult mosquito stage,” including using insect repellents and wearing long-sleeve shirts and pants.

“The bottom line here is that [this] is an uphill battle,” Dr. Frieden said. “We know we won’t be able to protect 100% of women, but for every single case of Zika infection in pregnancy we prevent, we’re potentially preventing an individual, personal, and family tragedy.”

Ebola research update: February 2016

The struggle to defeat Ebola viral disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a look.

New research reveals that the Ebola virus is typically cleared from the blood within 16 days – meaning that the risk of infection from contact with a survivor is low. However, an exception to this is transmission via sexual intercourse due to the virus’ presence in semen for many months after a patient has otherwise recovered. Contact with the patient’s blood is also a longer-term risk.

A report in Clinical Infectious Diseases assesses two cases of Ebola viral disease (EVD) in pregnant women who survived, initially with intact pregnancies. Both patients had live second trimester fetuses in utero following cure, but each woman ultimately delivered a stillborn fetus with persistent EVD–polymerase chain reaction amniotic fluid positivity. The investigators say this highlights the need for research on possible infectivity of amniotic fluid after convalescence of the mother.

According to new research, extracts of the medicinal plant Cistus incanus attack Ebola and HIV virus particles and prevent them from multiplying in cultured cells. Since the antiviral activity of Cistus extracts differs from all clinically approved drugs, the researchers say Cistus-derived products could be an important complement to currently established drug regimens.

Investigators at the CDC used mice engrafted with human immune cells as a model for Ebola virus infection and disease progression. They demonstrated that mice devoid of their native immune response and reconstituted with a human innate and adaptive immune system are susceptible to infection and die of disease within approximately 2 weeks after inoculation with wild-type Ebola virus. Mice appear to offer a unique model for investigating the human immune response in EVD and an alternative animal model for EVD pathogenesis studies and therapeutic screening.

A study published in Scientific Reports shows the ability of a vaccine vector, based on a common herpesvirus called cytomegalovirus expressing Ebola virus glycoprotein, to provide protection against Ebola virus in the experimental rhesus macaque, non-human primate model. Investigators say the study is a step forward for the development of conventional Ebola virus vaccines for use in humans.

Researchers at the Yale School of Public Health developed computational models for disease transmission and infection progression to estimate the repercussions of the 2014-2015 West African Ebola outbreak on populations already at risk for malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis. They estimated that a 50% reduction in access to healthcare services during the Ebola outbreak exacerbated malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis mortality rates by additional death counts of 6,269 in Guinea; 1,535 in Liberia; and 2,819 in Sierra Leone.

A broad panel of neutralizing, anti–Ebola virus antibodies have been isolated from a survivor of the recent Zaire outbreak. Investigators said 77% of the monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) neutralize live EBOV, and several mAbs exhibit unprecedented potency. They said the results provide a framework for the design of new EBOV vaccine candidates and immunotherapies.

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa provides valuable lessons for how to respond to infectious disease epidemics generally, according to an analysis in Science. The report says rebuilding local health care infrastructures, improving capacity to respond more quickly to outbreaks, and considering multiple perspectives across disciplines during decision-making processes are the key areas for action.

A multicenter non-randomized trial of Ebola virus patients in Guinea found that favipiravir monotherapy, along with standardized care, merits further study in patients with medium to high viremia, but not in those with very high viremia. The results also confirm that viral load is a strong predictor of mortality.

According to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the support from the World Health Organization’s polio program infrastructure, particularly the coordination mechanism adopted, the availability of skilled personnel in the polio program, and lessons learned from managing the polio eradication program greatly contributed to the speedy containment of the 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola viral disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a look.

New research reveals that the Ebola virus is typically cleared from the blood within 16 days – meaning that the risk of infection from contact with a survivor is low. However, an exception to this is transmission via sexual intercourse due to the virus’ presence in semen for many months after a patient has otherwise recovered. Contact with the patient’s blood is also a longer-term risk.

A report in Clinical Infectious Diseases assesses two cases of Ebola viral disease (EVD) in pregnant women who survived, initially with intact pregnancies. Both patients had live second trimester fetuses in utero following cure, but each woman ultimately delivered a stillborn fetus with persistent EVD–polymerase chain reaction amniotic fluid positivity. The investigators say this highlights the need for research on possible infectivity of amniotic fluid after convalescence of the mother.

According to new research, extracts of the medicinal plant Cistus incanus attack Ebola and HIV virus particles and prevent them from multiplying in cultured cells. Since the antiviral activity of Cistus extracts differs from all clinically approved drugs, the researchers say Cistus-derived products could be an important complement to currently established drug regimens.

Investigators at the CDC used mice engrafted with human immune cells as a model for Ebola virus infection and disease progression. They demonstrated that mice devoid of their native immune response and reconstituted with a human innate and adaptive immune system are susceptible to infection and die of disease within approximately 2 weeks after inoculation with wild-type Ebola virus. Mice appear to offer a unique model for investigating the human immune response in EVD and an alternative animal model for EVD pathogenesis studies and therapeutic screening.

A study published in Scientific Reports shows the ability of a vaccine vector, based on a common herpesvirus called cytomegalovirus expressing Ebola virus glycoprotein, to provide protection against Ebola virus in the experimental rhesus macaque, non-human primate model. Investigators say the study is a step forward for the development of conventional Ebola virus vaccines for use in humans.

Researchers at the Yale School of Public Health developed computational models for disease transmission and infection progression to estimate the repercussions of the 2014-2015 West African Ebola outbreak on populations already at risk for malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis. They estimated that a 50% reduction in access to healthcare services during the Ebola outbreak exacerbated malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis mortality rates by additional death counts of 6,269 in Guinea; 1,535 in Liberia; and 2,819 in Sierra Leone.

A broad panel of neutralizing, anti–Ebola virus antibodies have been isolated from a survivor of the recent Zaire outbreak. Investigators said 77% of the monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) neutralize live EBOV, and several mAbs exhibit unprecedented potency. They said the results provide a framework for the design of new EBOV vaccine candidates and immunotherapies.

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa provides valuable lessons for how to respond to infectious disease epidemics generally, according to an analysis in Science. The report says rebuilding local health care infrastructures, improving capacity to respond more quickly to outbreaks, and considering multiple perspectives across disciplines during decision-making processes are the key areas for action.

A multicenter non-randomized trial of Ebola virus patients in Guinea found that favipiravir monotherapy, along with standardized care, merits further study in patients with medium to high viremia, but not in those with very high viremia. The results also confirm that viral load is a strong predictor of mortality.

According to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the support from the World Health Organization’s polio program infrastructure, particularly the coordination mechanism adopted, the availability of skilled personnel in the polio program, and lessons learned from managing the polio eradication program greatly contributed to the speedy containment of the 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola viral disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a look.

New research reveals that the Ebola virus is typically cleared from the blood within 16 days – meaning that the risk of infection from contact with a survivor is low. However, an exception to this is transmission via sexual intercourse due to the virus’ presence in semen for many months after a patient has otherwise recovered. Contact with the patient’s blood is also a longer-term risk.

A report in Clinical Infectious Diseases assesses two cases of Ebola viral disease (EVD) in pregnant women who survived, initially with intact pregnancies. Both patients had live second trimester fetuses in utero following cure, but each woman ultimately delivered a stillborn fetus with persistent EVD–polymerase chain reaction amniotic fluid positivity. The investigators say this highlights the need for research on possible infectivity of amniotic fluid after convalescence of the mother.

According to new research, extracts of the medicinal plant Cistus incanus attack Ebola and HIV virus particles and prevent them from multiplying in cultured cells. Since the antiviral activity of Cistus extracts differs from all clinically approved drugs, the researchers say Cistus-derived products could be an important complement to currently established drug regimens.

Investigators at the CDC used mice engrafted with human immune cells as a model for Ebola virus infection and disease progression. They demonstrated that mice devoid of their native immune response and reconstituted with a human innate and adaptive immune system are susceptible to infection and die of disease within approximately 2 weeks after inoculation with wild-type Ebola virus. Mice appear to offer a unique model for investigating the human immune response in EVD and an alternative animal model for EVD pathogenesis studies and therapeutic screening.

A study published in Scientific Reports shows the ability of a vaccine vector, based on a common herpesvirus called cytomegalovirus expressing Ebola virus glycoprotein, to provide protection against Ebola virus in the experimental rhesus macaque, non-human primate model. Investigators say the study is a step forward for the development of conventional Ebola virus vaccines for use in humans.

Researchers at the Yale School of Public Health developed computational models for disease transmission and infection progression to estimate the repercussions of the 2014-2015 West African Ebola outbreak on populations already at risk for malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis. They estimated that a 50% reduction in access to healthcare services during the Ebola outbreak exacerbated malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis mortality rates by additional death counts of 6,269 in Guinea; 1,535 in Liberia; and 2,819 in Sierra Leone.

A broad panel of neutralizing, anti–Ebola virus antibodies have been isolated from a survivor of the recent Zaire outbreak. Investigators said 77% of the monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) neutralize live EBOV, and several mAbs exhibit unprecedented potency. They said the results provide a framework for the design of new EBOV vaccine candidates and immunotherapies.

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa provides valuable lessons for how to respond to infectious disease epidemics generally, according to an analysis in Science. The report says rebuilding local health care infrastructures, improving capacity to respond more quickly to outbreaks, and considering multiple perspectives across disciplines during decision-making processes are the key areas for action.

A multicenter non-randomized trial of Ebola virus patients in Guinea found that favipiravir monotherapy, along with standardized care, merits further study in patients with medium to high viremia, but not in those with very high viremia. The results also confirm that viral load is a strong predictor of mortality.

According to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the support from the World Health Organization’s polio program infrastructure, particularly the coordination mechanism adopted, the availability of skilled personnel in the polio program, and lessons learned from managing the polio eradication program greatly contributed to the speedy containment of the 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria.

On Twitter @richpizzi

EHR Report: How Zika virus reveals the fault in our EHRs

It is always noteworthy when the headlines in the medical and mainstream media appear to be the same.

Typically, this means one of two things: 1) Sensationalism has propelled a minor issue into the common lexicon; or 2) a truly serious issue has grown to the point where the whole world is finally taking notice.

With the recent resurgence of Zika virus, something that initially seemed to be the former has unmistakably developed into the latter, and health care providers are again facing an age-old question: How do we adequately fight an evolving and serious illness in the midst of an ever-changing battlefield?

As has been the case countless times before, the answer to this question really lies in early identification. One might think that the advent of modern technology would make this a much easier proposition, but that has not exactly been the case.

In fact, recent Ebola and Zika outbreaks have actually served to demonstrate a big problem in many modern electronic health records: poor clinical decision support.

In this column, we felt it would be helpful to highlight this shortcoming, and make the suggestion that in the world of EHRs …

Change needs to be faster than Zika

Zika virus is not new (it was first identified in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947), and neither is the concept of serious mosquito-born illness. While the current Zika hot zones are South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean, case reports indicate the virus is quickly migrating. At the time of this writing, more than 150 travel-associated cases of Zika have been identified in the continental United States, and it is clear that the consequences of undiagnosed Zika in pregnancy can be devastating.

Furthermore, Zika is just the latest of many viruses to threaten the health and welfare of modern civilization (for example, Ebola, swine flu, SARS, and so on), so screening and prevention is far from a novel idea.

Unfortunately, electronic record vendors don’t seem to have gotten the message that the ability to adapt quickly to public health threats should be a core element of any modern EHR.

On the contrary, EHRs seem to be designed for fixed “best practice” workflows, and updates are often slow in coming (typically requiring a major upgrade or “patch”). This renders them fairly unable to react nimbly to change.

This fact became evident to us as we attempted to implement a reminder for staff members to perform a Zika-focused travel history on all patients. We felt it was critical for this reminder to be prominent, be easy to interact with, and appear at the most appropriate time for screening.

Despite multiple attempts, we discovered that our top-ranked, industry-leading EHR was unable to do this seemingly straightforward task, and eventually we reverted to the age-old practice of hanging signs in all of the exam rooms. These encouraged patients to inform their doctor “of worrisome symptoms or recent travel history to affected areas.”

We refuse to accept the inability of any modern electronic health record to create simple and flexible clinical support rules and improve on the efficacy of the paper sign. This, especially in light of the fact that one of the core requirements of the Meaningful Use (MU) program – for which all EHRs are certified – is clinical decision support!

Unfortunately, the MU guidelines are not specific, so most vendors choose to include a standard set of rules and don’t allow the ability for customization. That just isn’t good enough. If Ebola and Zika have taught the health information technology community one thing, it’s that …

It is time for smarter EHRs!

For many people, the notion of artificial intelligence seems to be science fiction, but they don’t realize they are carrying incredible “AI” devices with them everywhere they go. We are, of course, referring to our cell phones, which seem to be getting more intelligent all the time.

If you own an iPhone, you may have noticed it often seems to know where you are about to drive and how long it will take you to get there. This can be a bit creepy at first, until you realize how helpful – and smart – it actually is.

Essentially, our devices are constantly collecting data, reading the patterns of our lives, and learning ways to enhance them. Smartphones have revolutionized how we communicate, work, and play. Why, then, can’t our electronic health record software do the same?

It will surprise exactly none of our readers that the Meaningful Use program has fallen short of its goal of promoting the true benefits of electronic records. Many critics have suggested that the incentive program has faltered because EHRs have made physicians work harder, without helping them work smarter.

Zika virus proves the critics correct. Beyond creating just simple reminders as mentioned above, EHRs should be able to make intelligent suggestions based on patient data and current practice guidelines.

Some EHRs get it half correct. For example, they are “smart” enough to remind clinicians that women of a certain age should have mammograms, but they fall short in the ability to efficiently update those reminders when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updates the screening recommendation (as they did recently).

Other EHRs do allow you to customize preventative health reminders, but do not place them in a position of prominence – so they are easily overlooked by providers as they care for patients.

Few products seem to get it just right, and it’s time for this to change.

Simply put, as questions in the media loom about how to stop this rising threat, we as frontline health care providers should have the tools – and the decision support – required to provide meaningful answers.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

It is always noteworthy when the headlines in the medical and mainstream media appear to be the same.

Typically, this means one of two things: 1) Sensationalism has propelled a minor issue into the common lexicon; or 2) a truly serious issue has grown to the point where the whole world is finally taking notice.

With the recent resurgence of Zika virus, something that initially seemed to be the former has unmistakably developed into the latter, and health care providers are again facing an age-old question: How do we adequately fight an evolving and serious illness in the midst of an ever-changing battlefield?

As has been the case countless times before, the answer to this question really lies in early identification. One might think that the advent of modern technology would make this a much easier proposition, but that has not exactly been the case.

In fact, recent Ebola and Zika outbreaks have actually served to demonstrate a big problem in many modern electronic health records: poor clinical decision support.

In this column, we felt it would be helpful to highlight this shortcoming, and make the suggestion that in the world of EHRs …

Change needs to be faster than Zika

Zika virus is not new (it was first identified in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947), and neither is the concept of serious mosquito-born illness. While the current Zika hot zones are South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean, case reports indicate the virus is quickly migrating. At the time of this writing, more than 150 travel-associated cases of Zika have been identified in the continental United States, and it is clear that the consequences of undiagnosed Zika in pregnancy can be devastating.

Furthermore, Zika is just the latest of many viruses to threaten the health and welfare of modern civilization (for example, Ebola, swine flu, SARS, and so on), so screening and prevention is far from a novel idea.

Unfortunately, electronic record vendors don’t seem to have gotten the message that the ability to adapt quickly to public health threats should be a core element of any modern EHR.

On the contrary, EHRs seem to be designed for fixed “best practice” workflows, and updates are often slow in coming (typically requiring a major upgrade or “patch”). This renders them fairly unable to react nimbly to change.

This fact became evident to us as we attempted to implement a reminder for staff members to perform a Zika-focused travel history on all patients. We felt it was critical for this reminder to be prominent, be easy to interact with, and appear at the most appropriate time for screening.

Despite multiple attempts, we discovered that our top-ranked, industry-leading EHR was unable to do this seemingly straightforward task, and eventually we reverted to the age-old practice of hanging signs in all of the exam rooms. These encouraged patients to inform their doctor “of worrisome symptoms or recent travel history to affected areas.”

We refuse to accept the inability of any modern electronic health record to create simple and flexible clinical support rules and improve on the efficacy of the paper sign. This, especially in light of the fact that one of the core requirements of the Meaningful Use (MU) program – for which all EHRs are certified – is clinical decision support!

Unfortunately, the MU guidelines are not specific, so most vendors choose to include a standard set of rules and don’t allow the ability for customization. That just isn’t good enough. If Ebola and Zika have taught the health information technology community one thing, it’s that …

It is time for smarter EHRs!

For many people, the notion of artificial intelligence seems to be science fiction, but they don’t realize they are carrying incredible “AI” devices with them everywhere they go. We are, of course, referring to our cell phones, which seem to be getting more intelligent all the time.

If you own an iPhone, you may have noticed it often seems to know where you are about to drive and how long it will take you to get there. This can be a bit creepy at first, until you realize how helpful – and smart – it actually is.

Essentially, our devices are constantly collecting data, reading the patterns of our lives, and learning ways to enhance them. Smartphones have revolutionized how we communicate, work, and play. Why, then, can’t our electronic health record software do the same?

It will surprise exactly none of our readers that the Meaningful Use program has fallen short of its goal of promoting the true benefits of electronic records. Many critics have suggested that the incentive program has faltered because EHRs have made physicians work harder, without helping them work smarter.

Zika virus proves the critics correct. Beyond creating just simple reminders as mentioned above, EHRs should be able to make intelligent suggestions based on patient data and current practice guidelines.

Some EHRs get it half correct. For example, they are “smart” enough to remind clinicians that women of a certain age should have mammograms, but they fall short in the ability to efficiently update those reminders when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updates the screening recommendation (as they did recently).

Other EHRs do allow you to customize preventative health reminders, but do not place them in a position of prominence – so they are easily overlooked by providers as they care for patients.

Few products seem to get it just right, and it’s time for this to change.

Simply put, as questions in the media loom about how to stop this rising threat, we as frontline health care providers should have the tools – and the decision support – required to provide meaningful answers.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

It is always noteworthy when the headlines in the medical and mainstream media appear to be the same.

Typically, this means one of two things: 1) Sensationalism has propelled a minor issue into the common lexicon; or 2) a truly serious issue has grown to the point where the whole world is finally taking notice.

With the recent resurgence of Zika virus, something that initially seemed to be the former has unmistakably developed into the latter, and health care providers are again facing an age-old question: How do we adequately fight an evolving and serious illness in the midst of an ever-changing battlefield?

As has been the case countless times before, the answer to this question really lies in early identification. One might think that the advent of modern technology would make this a much easier proposition, but that has not exactly been the case.

In fact, recent Ebola and Zika outbreaks have actually served to demonstrate a big problem in many modern electronic health records: poor clinical decision support.

In this column, we felt it would be helpful to highlight this shortcoming, and make the suggestion that in the world of EHRs …

Change needs to be faster than Zika

Zika virus is not new (it was first identified in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947), and neither is the concept of serious mosquito-born illness. While the current Zika hot zones are South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean, case reports indicate the virus is quickly migrating. At the time of this writing, more than 150 travel-associated cases of Zika have been identified in the continental United States, and it is clear that the consequences of undiagnosed Zika in pregnancy can be devastating.

Furthermore, Zika is just the latest of many viruses to threaten the health and welfare of modern civilization (for example, Ebola, swine flu, SARS, and so on), so screening and prevention is far from a novel idea.

Unfortunately, electronic record vendors don’t seem to have gotten the message that the ability to adapt quickly to public health threats should be a core element of any modern EHR.

On the contrary, EHRs seem to be designed for fixed “best practice” workflows, and updates are often slow in coming (typically requiring a major upgrade or “patch”). This renders them fairly unable to react nimbly to change.

This fact became evident to us as we attempted to implement a reminder for staff members to perform a Zika-focused travel history on all patients. We felt it was critical for this reminder to be prominent, be easy to interact with, and appear at the most appropriate time for screening.

Despite multiple attempts, we discovered that our top-ranked, industry-leading EHR was unable to do this seemingly straightforward task, and eventually we reverted to the age-old practice of hanging signs in all of the exam rooms. These encouraged patients to inform their doctor “of worrisome symptoms or recent travel history to affected areas.”

We refuse to accept the inability of any modern electronic health record to create simple and flexible clinical support rules and improve on the efficacy of the paper sign. This, especially in light of the fact that one of the core requirements of the Meaningful Use (MU) program – for which all EHRs are certified – is clinical decision support!

Unfortunately, the MU guidelines are not specific, so most vendors choose to include a standard set of rules and don’t allow the ability for customization. That just isn’t good enough. If Ebola and Zika have taught the health information technology community one thing, it’s that …

It is time for smarter EHRs!

For many people, the notion of artificial intelligence seems to be science fiction, but they don’t realize they are carrying incredible “AI” devices with them everywhere they go. We are, of course, referring to our cell phones, which seem to be getting more intelligent all the time.

If you own an iPhone, you may have noticed it often seems to know where you are about to drive and how long it will take you to get there. This can be a bit creepy at first, until you realize how helpful – and smart – it actually is.

Essentially, our devices are constantly collecting data, reading the patterns of our lives, and learning ways to enhance them. Smartphones have revolutionized how we communicate, work, and play. Why, then, can’t our electronic health record software do the same?

It will surprise exactly none of our readers that the Meaningful Use program has fallen short of its goal of promoting the true benefits of electronic records. Many critics have suggested that the incentive program has faltered because EHRs have made physicians work harder, without helping them work smarter.

Zika virus proves the critics correct. Beyond creating just simple reminders as mentioned above, EHRs should be able to make intelligent suggestions based on patient data and current practice guidelines.

Some EHRs get it half correct. For example, they are “smart” enough to remind clinicians that women of a certain age should have mammograms, but they fall short in the ability to efficiently update those reminders when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updates the screening recommendation (as they did recently).

Other EHRs do allow you to customize preventative health reminders, but do not place them in a position of prominence – so they are easily overlooked by providers as they care for patients.

Few products seem to get it just right, and it’s time for this to change.

Simply put, as questions in the media loom about how to stop this rising threat, we as frontline health care providers should have the tools – and the decision support – required to provide meaningful answers.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Brazilian study identifies fetal abnormalities linked to Zika virus

Fetal abnormalities were detected among more than a quarter of pregnant women who underwent ultrasound examinations after testing positive for Zika virus infection.

The small study, which included 88 pregnant women enrolled from September 2015 through February 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, was published online March 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412).

“Our findings provide further support for a link between maternal ZIKV infection and fetal and placental abnormalities that is not unlike that of other viruses that are known to cause congenital infections characterized by intrauterine growth restriction and placental insufficiency,” investigators from Brazil and California reported.

The women in the study had developed a rash within the previous 5 days and were tested for Zika virus infection using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays. Of the 88 women tested, 72 (82%) tested positive for Zika virus in blood, urine, or both.

Acute Zika infection was found throughout the course of pregnancy, though more than half of the women presented with acute infection during the second trimester. Along with a macular or maculopapular rash with pruritus, other distinctive clinical features of Zika virus infection included conjunctival injection, lymphadenopathy, and an absence of respiratory symptoms.

Two women who were positive for Zika virus had miscarriages during the first trimester. The investigators performed ultrasound for 42 of the remaining 70 women who had tested positive for Zika virus, as well as all women who tested negative for the virus. The other women who tested positive for Zika virus declined the imaging studies.

Fetal abnormalities were detected in 12 (29%) of the 42 women who were Zika virus positive and none of the women who had tested negative.

Among the 12 fetuses with abnormalities, there were two fetal deaths noted on ultrasound after 30 weeks of gestation. There were five fetuses with in utero growth restriction with or without microcephaly on ultrasound. Four fetuses had cerebral calcifications, and other central nervous system alterations were noted in two fetuses. Ultrasound detected abnormal arterial flow in the cerebral or umbilical arteries in four fetuses. Also, oligohydramnios and anhydramnios were seen in two fetuses.

At the time of this report, there had been six live births and two stillbirths among the study cohort and the ultrasound findings had been confirmed. The study was not supported by any research funds. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Fetal abnormalities were detected among more than a quarter of pregnant women who underwent ultrasound examinations after testing positive for Zika virus infection.

The small study, which included 88 pregnant women enrolled from September 2015 through February 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, was published online March 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412).

“Our findings provide further support for a link between maternal ZIKV infection and fetal and placental abnormalities that is not unlike that of other viruses that are known to cause congenital infections characterized by intrauterine growth restriction and placental insufficiency,” investigators from Brazil and California reported.

The women in the study had developed a rash within the previous 5 days and were tested for Zika virus infection using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays. Of the 88 women tested, 72 (82%) tested positive for Zika virus in blood, urine, or both.

Acute Zika infection was found throughout the course of pregnancy, though more than half of the women presented with acute infection during the second trimester. Along with a macular or maculopapular rash with pruritus, other distinctive clinical features of Zika virus infection included conjunctival injection, lymphadenopathy, and an absence of respiratory symptoms.

Two women who were positive for Zika virus had miscarriages during the first trimester. The investigators performed ultrasound for 42 of the remaining 70 women who had tested positive for Zika virus, as well as all women who tested negative for the virus. The other women who tested positive for Zika virus declined the imaging studies.

Fetal abnormalities were detected in 12 (29%) of the 42 women who were Zika virus positive and none of the women who had tested negative.

Among the 12 fetuses with abnormalities, there were two fetal deaths noted on ultrasound after 30 weeks of gestation. There were five fetuses with in utero growth restriction with or without microcephaly on ultrasound. Four fetuses had cerebral calcifications, and other central nervous system alterations were noted in two fetuses. Ultrasound detected abnormal arterial flow in the cerebral or umbilical arteries in four fetuses. Also, oligohydramnios and anhydramnios were seen in two fetuses.

At the time of this report, there had been six live births and two stillbirths among the study cohort and the ultrasound findings had been confirmed. The study was not supported by any research funds. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Fetal abnormalities were detected among more than a quarter of pregnant women who underwent ultrasound examinations after testing positive for Zika virus infection.

The small study, which included 88 pregnant women enrolled from September 2015 through February 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, was published online March 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412).

“Our findings provide further support for a link between maternal ZIKV infection and fetal and placental abnormalities that is not unlike that of other viruses that are known to cause congenital infections characterized by intrauterine growth restriction and placental insufficiency,” investigators from Brazil and California reported.

The women in the study had developed a rash within the previous 5 days and were tested for Zika virus infection using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays. Of the 88 women tested, 72 (82%) tested positive for Zika virus in blood, urine, or both.

Acute Zika infection was found throughout the course of pregnancy, though more than half of the women presented with acute infection during the second trimester. Along with a macular or maculopapular rash with pruritus, other distinctive clinical features of Zika virus infection included conjunctival injection, lymphadenopathy, and an absence of respiratory symptoms.

Two women who were positive for Zika virus had miscarriages during the first trimester. The investigators performed ultrasound for 42 of the remaining 70 women who had tested positive for Zika virus, as well as all women who tested negative for the virus. The other women who tested positive for Zika virus declined the imaging studies.

Fetal abnormalities were detected in 12 (29%) of the 42 women who were Zika virus positive and none of the women who had tested negative.

Among the 12 fetuses with abnormalities, there were two fetal deaths noted on ultrasound after 30 weeks of gestation. There were five fetuses with in utero growth restriction with or without microcephaly on ultrasound. Four fetuses had cerebral calcifications, and other central nervous system alterations were noted in two fetuses. Ultrasound detected abnormal arterial flow in the cerebral or umbilical arteries in four fetuses. Also, oligohydramnios and anhydramnios were seen in two fetuses.

At the time of this report, there had been six live births and two stillbirths among the study cohort and the ultrasound findings had been confirmed. The study was not supported by any research funds. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Zika virus infection in pregnancy appears to be associated with in utero growth restriction, central nervous system lesions, and fetal death.

Major finding: Fetal abnormalities were detected by ultrasound in 12 of 42 pregnant women who tested positive for Zika virus infection.

Data source: A prospective study of 88 pregnant women with a rash from September 2015 through February 2016 in Rio de Janeiro.

Disclosures: The study was not supported by any research funds. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

WHO guidance for caring for pregnant women in Zika virus areas

The World Health Organization has released guidance for physicians and other healthcare providers on how to care for pregnant women in areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing.

“The guidance is intended to inform the development of national and local clinical protocols and health policies that relate to pregnancy care in the context of Zika virus transmission,” according to the document, released on March 2.