User login

Cardiogenic shock: From ECMO to Impella and beyond

A 43-year-old man presented to a community hospital with acute chest pain and shortness of breath and was diagnosed with anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He was a smoker with a history of alcohol abuse, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and in the past he had undergone percutaneous coronary interventions to the right coronary artery and the first obtuse marginal artery.

Angiography showed total occlusion in the left anterior descending artery, 90% stenosis in the right coronary artery, and mild disease in the left circumflex artery. A drug-eluting stent was placed in the left anterior descending artery, resulting in good blood flow.

However, his left ventricle continued to have severe dysfunction. An intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted. Afterward, computed tomography showed subsegmental pulmonary embolism with congestion. His mean arterial pressure was 60 mm Hg (normal 70–110), central venous pressure 12 mm Hg (3–8), pulmonary artery pressure 38/26 mm Hg (15–30/4–12), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 24 mm Hg (2–15), and cardiac index 1.4 L/min (2.5–4).

The patient was started on dobutamine and norepinephrine and transferred to Cleveland Clinic on day 2. Over the next day, he had runs of ventricular tachycardia, for which he was given amiodarone and lidocaine. His urine output was low, and his serum creatinine was elevated at 1.65 mg/dL (baseline 1.2, normal 0.5–1.5). Liver function tests were also elevated, with aspartate aminotransferase at 115 U/L(14–40) and alanine aminotransferase at 187 U/L (10–54).

Poor oxygenation was evident: his arterial partial pressure of oxygen was 64 mm Hg (normal 75–100). He was intubated and given 100% oxygen with positive end-expiratory pressure of 12 cm H2O.

Echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 15% (normal 55%–70%) and mild right ventricular dysfunction.

ECMO and then Impella placement

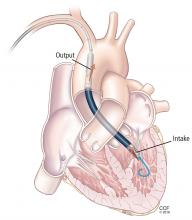

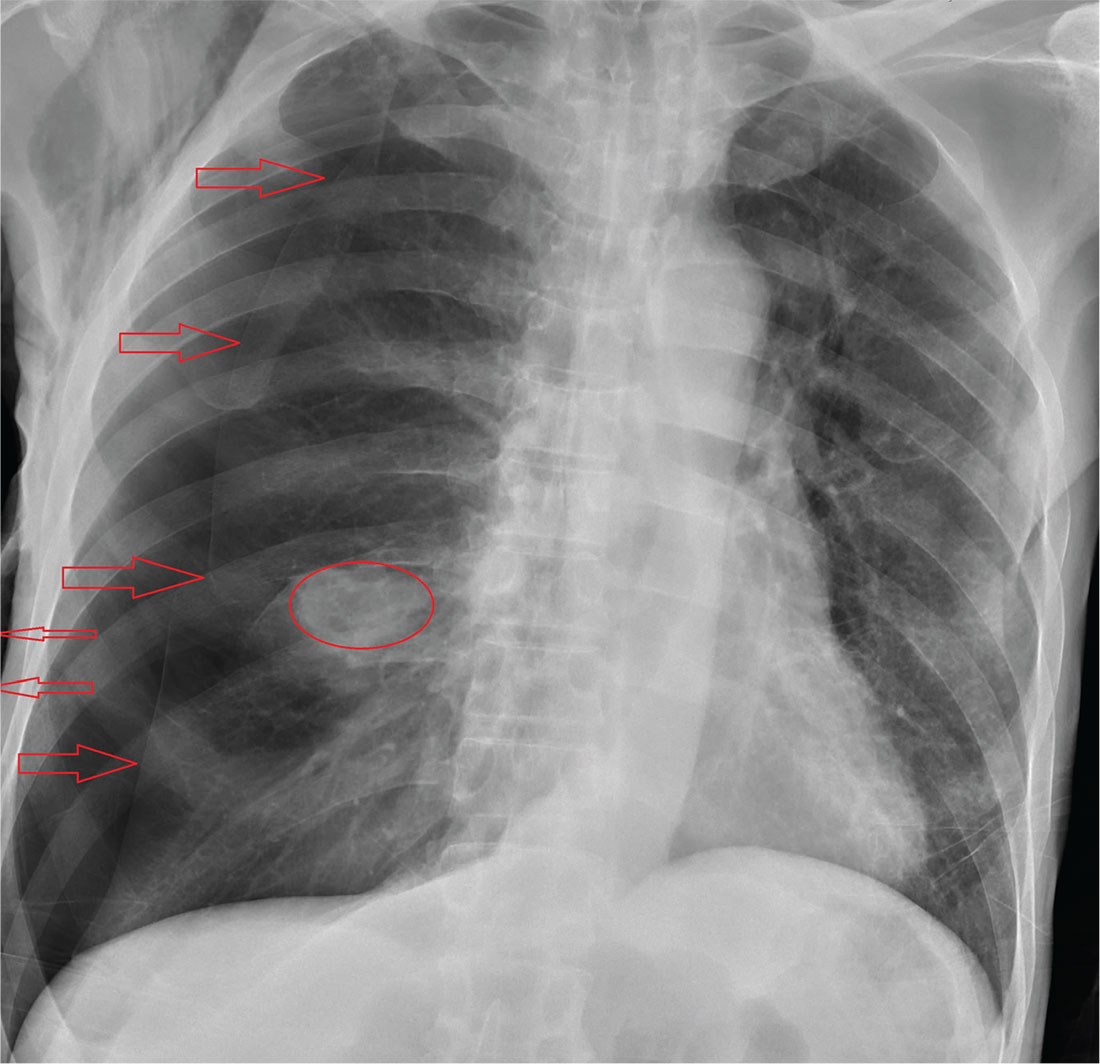

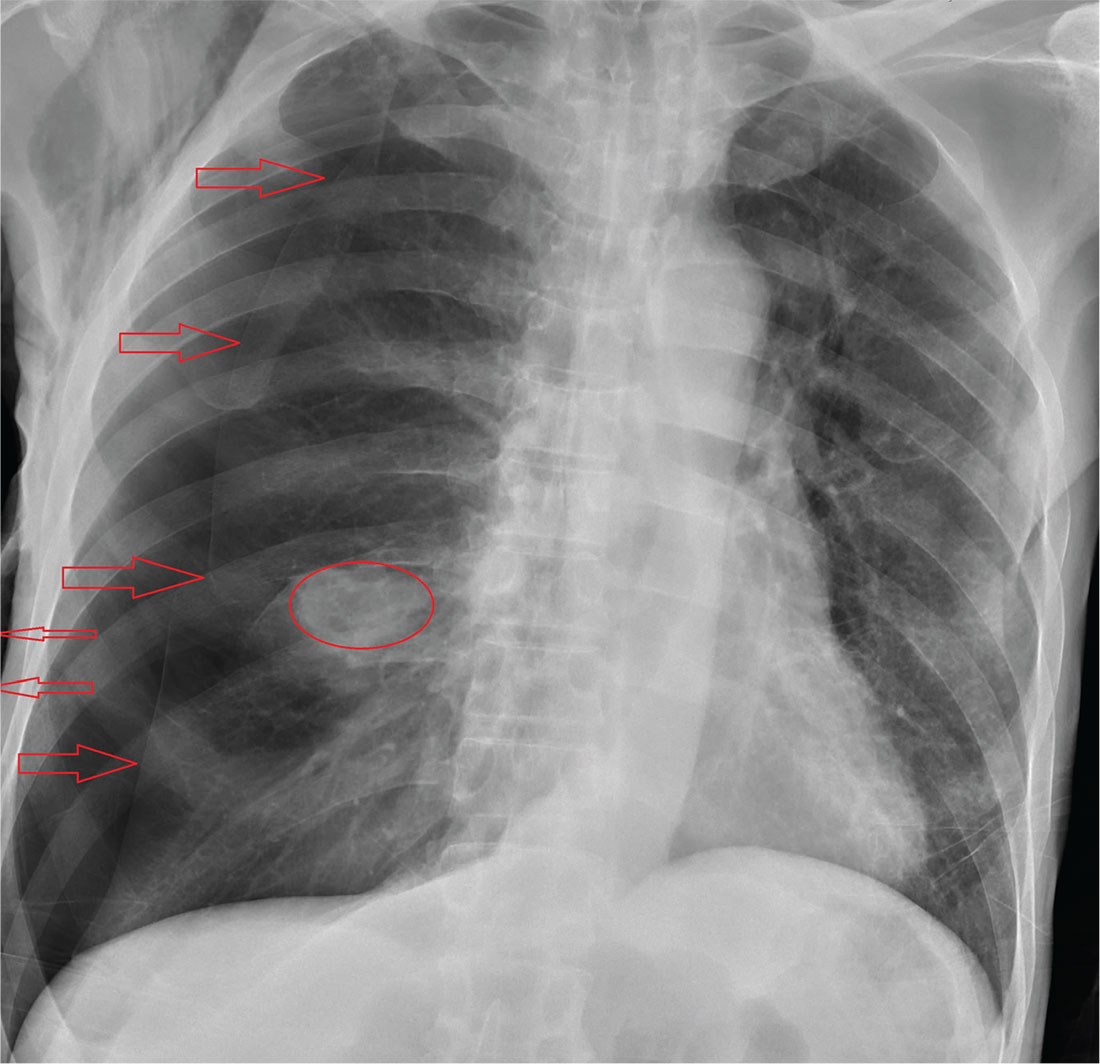

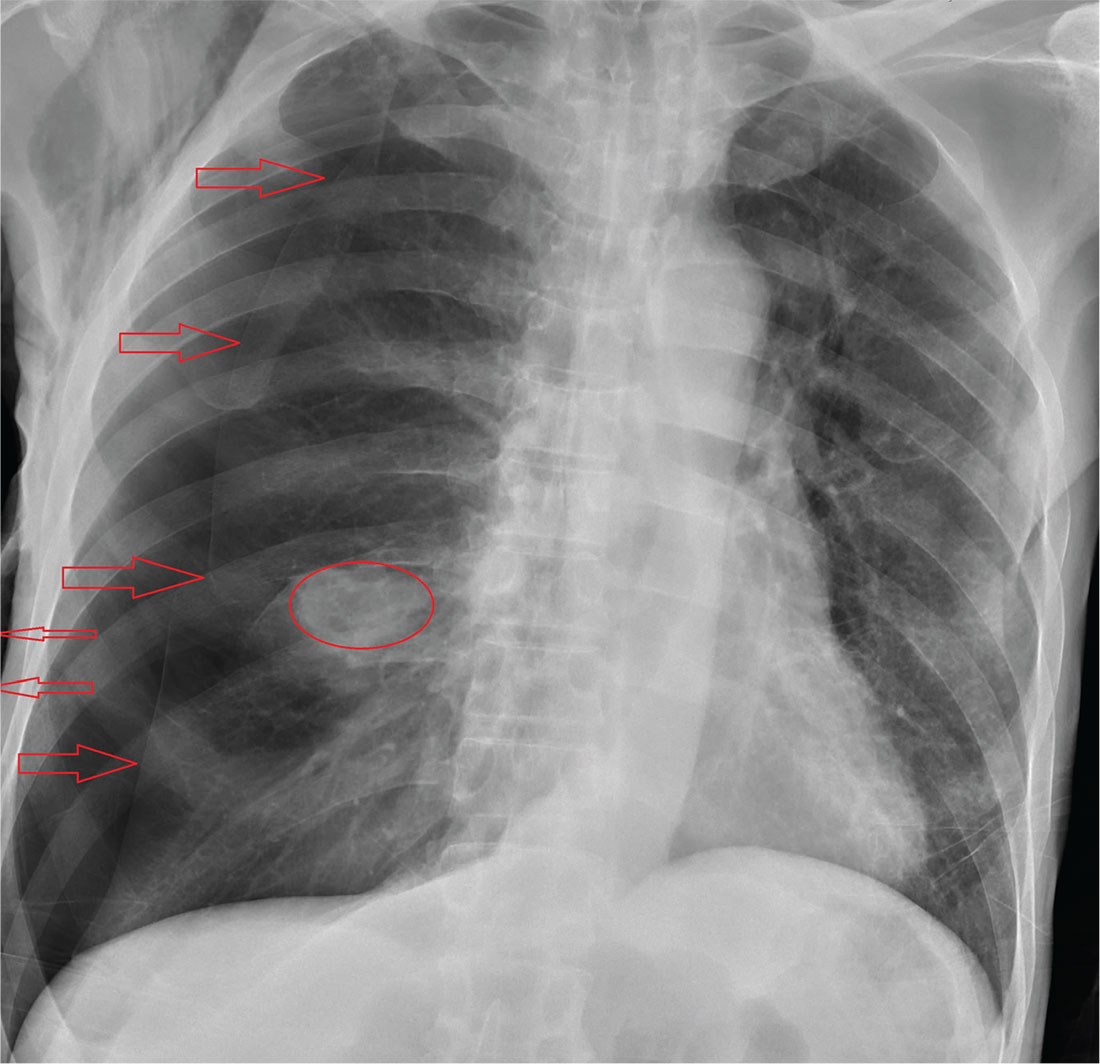

On his third hospital day, a venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device was placed peripherally (Figure 1).

His hemodynamic variables stabilized, and he was weaned off dobutamine and norepinephrine. Results of liver function tests normalized, his urinary output increased, and his serum creatinine dropped to a normal 1.0 mg/dL. However, a chest radiograph showed pulmonary congestion, and echocardiography now showed severe left ventricular dysfunction.

On hospital day 5, the patient underwent surgical placement of an Impella 5.0 device (Abiomed, Danvers, MA) through the right axillary artery in an effort to improve his pulmonary edema. The ECMO device was removed. Placement of a venovenous ECMO device was deemed unnecessary when oxygenation improved with the Impella.

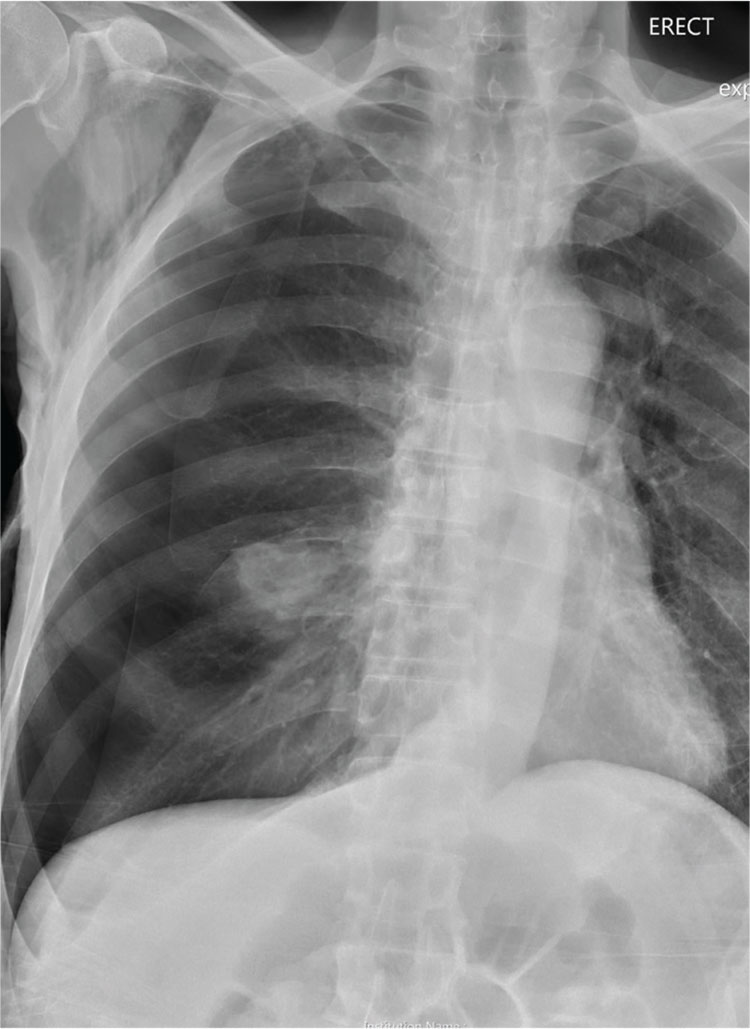

Three days after Impella placement, radiography showed improved edema with some remaining pleural effusion.

ACUTE CARDIOGENIC SHOCK

Cardiogenic shock remains a challenging clinical problem: patients with it are among the sickest in the hospital, and many of them die. ECMO was once the only therapy available and is still widely used. However, it is a 2-edged sword; complications such as bleeding, infection, and thrombosis are almost inevitable if it is used for long. Importantly, patients are usually kept intubated and bedridden.

In recent years, new devices have become available that are easier to place (some in the catheterization laboratory or even at the bedside) and allow safer bridging to recovery, transplant, or other therapies.

This case illustrates the natural history of cardiogenic shock and the preferred clinical approach: ie, ongoing evaluation that permits rapid response to evolving challenges.

In general, acute cardiogenic shock occurs within 24 to 48 hours after the initial insult, so even if a procedure succeeds, the patient may develop progressive hypotension and organ dysfunction. Reduced cardiac output causes a downward spiral with multiple systemic and inflammatory processes as well as increased nitric oxide synthesis, leading to progressive decline and eventual end-organ dysfunction.

Continuously evaluate

The cardiac team should continuously assess the acuity and severity of a patient’s condition, with the goals of maintaining end-organ perfusion and identifying the source of problems. Refractory cardiogenic shock, with tissue hypoperfusion despite vasoactive medications and treatment of the underlying cause, is associated with in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 30% to 50%.1,2 The rates have actually increased over the past decade, as sicker patients are being treated.

When a patient presents with cardiogenic shock, we first try a series of vasoactive drugs and usually an intra-aortic balloon pump (Figure 2). We then tailor treatment depending on etiology. For example, a patient may have viral myocarditis and may even require a biopsy.

If cardiogenic shock is refractory, mechanical circulatory support devices can be a short-term bridge to either recovery or a new decision. A multidisciplinary team should be consulted to consider transplant, a long-term device, or palliative care. Sometimes a case requires “bridging to a bridge,” with several devices used short-term in turn.

Prognostic factors in cardiogenic shock

Several tools help predict outcome in a severely ill patient. End-organ function, indicated by blood lactate levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate, is perhaps the most informative and should be monitored serially.

CardShock3 is a simple scoring system based on age, mental status at presentation, laboratory values, and medical history. Patients receive 1 point for each of the following factors:

- Age > 75

- Confusion at presentation

- Previous myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting

- Acute coronary syndrome etiology

- Left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%

- Blood lactate level between 2 and 4 mmol/L, inclusively (2 points for lactate levels > 4 mmol/L)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, inclusively (2 points if < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Thus, scores range from 0 (best) to 9 (worst). A score of 0 to 3 points was associated with a 9% risk of death in the hospital, a score of 4 or 5 with a risk of 36%, and a score of 6 through 9 with a risk of 77%.3

The Survival After Veno-arterial ECMO (SAVE) score (www.save-score.com) is a prediction tool derived from a large international ECMO registry.4 It is based on patient age, diagnosis, and indicators of end-organ dysfunction. Scores range from –35 (worst) to +7 (best).

The mortality rate associated with postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock increases with the amount of inotropic support provided. In a 1996–1999 case series of patients who underwent open-heart surgery,5 the hospital mortality rate was 40% in those who received 2 inotropes in high doses and 80% in those who received 3. A strategy of early implementation of mechanical support is critical.

Selection criteria for destination therapy

Deciding whether a patient should receive a long-term device is frequently a challenge. The decision often must be based on limited information about not only the medical indications but also psychosocial factors that influence long-term success.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have established criteria for candidates for left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as destination therapy.6 Contraindications established for heart transplant should also be considered (Table 1).

CASE REVISITED

Several factors argued against LVAD placement in our patient. He had no health insurance and had been off medications. He smoked and said he consumed 3 hard liquor drinks per week. His Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation score was 30 (minimally acceptable). He had hypoxia with subsegmental pulmonary edema, a strong contraindication to immediate transplant.

On the other hand, he had only mild right ventricular dysfunction. His CardShock score was 4 (intermediate risk, based on lactate 1.5 mmol/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate 52 mL/min/1.73 m2). His SAVE score was –9 (class IV), which overall is associated with a 30% risk of death (low enough to consider treatment).

During the patient’s time on temporary support, the team had the opportunity to better understand him and assess his family support and his ability to handle a permanent device. His surviving the acute course bolstered the team’s confidence that he could enjoy long-term survival with destination therapy.

CATHETERIZATION LABORATORY DEVICE CAPABILITIES

Although most implantation procedures are done in the operating room, they are often done in the catheterization laboratory because patients undergoing catheterization may not be stable enough for transfer, or an emergency intervention may be required during the night. Catheterization interventionists are also an important part of the team to help determine the best approach for long-term therapy.

The catheterization laboratory has multiple acute intervention options. Usually, decisions must be made quickly. In general, patients needing mechanical support are managed as follows:

- Those who need circulation support and oxygenation receive ECMO

- Those who need circulation support alone because of mechanical issues (eg, myocardial infarction) are considered for an intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, or TandemHeart pump (Cardiac Assist, Pittsburgh, PA).

Factors that guide the selection of a temporary pump include:

- Left ventricular function

- Right ventricular function

- Aortic valve stenosis (some devices cannot be inserted through critical aortic stenosis)

- Aortic regurgitation (can affect some devices)

- Peripheral artery disease (some devices are large and must be placed percutaneously).

CHOOSING AMONG PERCUTANEOUS DEVICES

Circulatory support in cardiogenic shock improves outcomes, and devices play an important role in supporting high-risk procedures. The goal is not necessarily to use the device throughout the hospital stay. Acute stabilization is most important initially; a more considered decision about long-term therapy can be made when more is known about the patient.

Patient selection is the most important component of success. However, randomized data to support outcomes with the various devices are sparse and complicated by the critically ill state of the patient population.

SHORT-TERM CIRCULATORY SUPPORT: ECMO, IMPELLA, TANDEMHEART

A menu of options is available for temporary mechanical support. Options differ by their degree of circulatory support and ease of insertion (Table 2).

ECMO: A fast option with many advantages

ECMO has evolved and now can be placed quickly. A remote diagnostic platform such as CardioHub permits management at the bedside, in the medical unit, or in the cardiac intensive care unit.7

ECMO has several advantages. It can be used during cardiopulmonary bypass, it provides oxygenation, it is the only option in the setting of lung injury, it can be placed peripherally (without thoracotomy), and it is the only percutaneous option for biventricular support.

ECMO also has significant disadvantages

ECMO is a good device for acute resuscitation of a patient in shock, as it offers quick placement and resuscitation. But it is falling out of favor because of significant disadvantages.

Its major drawback is that it provides no left ventricular unloading. Although in a very unstable patient ECMO can stabilize end organs and restore their function, the lack of left ventricular unloading and reduced ventricular work threaten the myocardium. It creates extremely high afterload; therefore, in a left ventricle with poor function, wall tension and myocardial oxygen demand increase. Multiple studies have shown that coronary perfusion worsens, especially if the patient is cannulated peripherally. Because relative cerebral hypoxia occurs in many situations, it is imperative to check blood saturations at multiple sites to determine if perfusion is adequate everywhere.

Ineffective left ventricular unloading with venoarterial ECMO is managed in several ways. Sometimes left ventricular distention is slight and the effects are subtle. Left ventricular distention causing pulmonary edema can be addressed with:

- Inotropes (in moderate doses)

- Anticoagulation to prevent left ventricular thrombus formation

- An intra-aortic balloon pump. Most patients on ECMO already have an intra-aortic balloon pump in place, and it should be left in to provide additional support. For those who do not have one, it should be placed via the contralateral femoral artery.

If problems persist despite these measures, apical cannulation or left ventricular septostomy can be performed.

Outcomes with ECMO have been disappointing. Studies show that whether ECMO was indicated for cardiac failure or for respiratory failure, survival is only about 25% at 5 years. Analyzing data only for arteriovenous ECMO, survival was 48% in bridged patients and 41% in patients who were weaned.

The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry, in their international summary from 2010, found that 34% of cardiac patients on ECMO survived to discharge or transfer. Most of these patients had cardiogenic shock from acute myocardial infarction. Outcomes are so poor because of complications endemic to ECMO, eg, dialysis-dependent renal failure (about 40%) and neurologic complications (about 30%), often involving ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Limb and pump complications were also significant in the past. These have been reduced with the new reperfusion cannula and the Quadrox oxygenator.

Complications unique to ECMO should be understood and anticipated so that they can be avoided. Better tools are available, ie, Impella and TandemHeart.

Left-sided Impella: A longer-term temporary support

ECMO is a temporary fix that is usually used only for a few days. If longer support is needed, axillary placement of an Impella should be used as a bridge to recovery, transplant, or a durable LVAD.

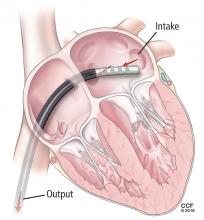

The Impella device (Figure 3) is a miniature rotary blood pump increasingly used to treat cardiogenic shock. It is inserted retrograde across the aortic valve to provide short-term ventricular support. Most devices are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for less than 7 days of use, but we have experience using them up to 30 days. They are very hemocompatible, involving minimal hemolysis. Axillary placement allows early extubation and ambulation and is more stable than groin placement.

Several models are available: the 2.5 and 3.5 L/min devices can be placed percutaneously, while the 5 L/min model must be surgically placed in the axillary or groin region. Heparin is required with their use. They can replace ECMO. A right ventricular assist device (RVAD), Impella RP, is also available.

Physiologic impact of the Impella

The Impella fully unloads the left ventricle, reducing myocardial oxygen demand and increasing myocardial blood flow. It reduces end-diastolic volume and pressure, the mechanical work of the heart, and wall tension. Microvascular resistance is reduced, allowing increased coronary flow. Cardiac output and power are increased by multiple means.8–11

The RECOVER 1 trial evaluated the 5L Impella placed after cardiac surgery. The cardiac index increased in all the patients, and the systemic vascular resistance and wedge pressure decreased.12

Unloading the ventricle is critical. Meyns and colleagues13 found a fivefold reduction in infarct size from baseline in a left anterior descending occlusion model in pigs after off-loading the ventricle.

Impella has the advantage of simple percutaneous insertion (the 2.5 and CP models). It also tests right ventricular tolerance: if the right ventricle is doing well, one can predict with high certainty that it will tolerate an LVAD (eg, HeartWare, HeartMate 2 (Pleasanton, CA), or HeartMate 3 when available).

Disadvantages include that it provides only left ventricular support, although a right ventricular device can be inserted for dual support. Placement requires fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance.

TandemHeart requires septal puncture

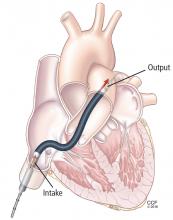

The TandemHeart is approved for short-term and biventricular use. It consists of an extracorporeal centrifugal pump that withdraws blood from the left atrium via a trans-septal cannula placed through the femoral vein (Figure 4) and returns it to one or both femoral arteries. The blood is pumped at up to 5 L/min.

It is designed to reduce the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, ventricular work, and myocardial oxygen demand and increase cardiac output and mean arterial pressure. It has the advantages of percutaneous placement and the ability to provide biventricular support with 2 devices. It can be used for up to 3 weeks. It can easily be converted to ECMO by either splicing in an oxygenator or adding another cannula.

Although the TandemHeart provides significant support, it is no longer often used. A 21F venous cannula must be passed to the left atrium by trans-septal puncture, which requires advanced skill and must be done in the catheterization laboratory. Insertion can take too much time and cause bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant. Insertion usually destroys the septum, and removal requires a complete patch of the entire septum. Systemic anticoagulation is required. Other disadvantages are risks of hemolysis, limb ischemia, and infection with longer support times.

The CentriMag (Levitronix LLC; Framingham, MA) is an improved device that requires only 1 cannula instead of 2 to cover both areas.

DEVICES FOR RIGHT-SIDED SUPPORT

Most early devices were designed for left-sided support. The right heart, especially in failure, has been more difficult to manage. Previously the only option for a patient with right ventricular failure was venoarterial ECMO. This is more support than needed for a patient with isolated right ventricular failure and involves the risk of multiple complications from the device.

With more options available for the right heart (Table 3), we can choose the most appropriate device according to the underlying cause of right heart failure (eg, right ventricular infarct, pulmonary hypertension), the likelihood of recovery, and the expected time to recovery.

The ideal RVAD would be easy to implant, maintain, and remove. It would allow for chest closure and patient ambulation. It would be durable and biocompatible, so that it could remain implanted for months if necessary. It would cause little blood trauma, have the capability for adding an oxygenator for pulmonary support, and be cost-effective.

Although no single system has all these qualities, each available device fulfills certain combinations of these criteria, so the best one can be selected for each patient’s needs.

ECMO Rotaflow centrifugal pump: Fast, simple, inexpensive

A recent improvement to ECMO is the Rotaflow centrifugal pump (Maquet, Wayne, NJ), which is connected by sewing an 8-mm graft onto the pulmonary artery and placing a venous cannula in the femoral vein. If the patient is not bleeding, the chest can then be closed. This creates a fast, simple, and inexpensive temporary RVAD system. When the patient is ready to be weaned, the outflow graft can be disconnected at the bedside without reopening the chest.

The disadvantage is that the Rotaflow system contains a sapphire bearing. Although it is magnetically coupled, it generates heat and is a nidus for thrombus formation, which can lead to pump failure and embolization. This system can be used for patients who are expected to need support for less than 5 to 7 days. Beyond this duration, the incidence of complications increases.

CentriMag Ventricular Assist System offers right, left, or bilateral support

The CentriMag Ventricular Assist System is a fully magnetically levitated pump containing no bearings or seals, and with the same technology as is found in many of the durable devices such as HeartMate 3. It is coupled with a reusable motor and is easy to use.

CentriMag offers versatility, allowing for right, left, or bilateral ventricular support. An oxygenator can be added for pulmonary edema and additional support. It is the most biocompatible device and is FDA-approved for use for 4 weeks, although it has been used successfully for much longer. It allows for chest closure and ambulation. It is especially important as a bridge to transplant. The main disadvantage is that insertion and removal require sternotomy.

Impella RP: One size does not fit all

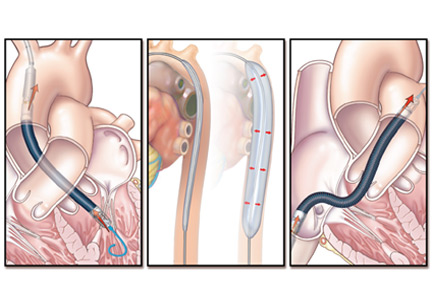

The Impella RP (Figure 5) has an 11F catheter diameter, 23F pump, and a maximum flow rate of more than 4 L/minute. It has a unique 3-dimensional cannula design based on computed tomography 3-dimensional reconstructions from hundreds of patients.

The device is biocompatible and can be used for support for more than 7 days, although most patients require only 3 or 4 days. There is almost no priming volume, so there is no hemodilution.

The disadvantages are that it is more challenging to place than other devices, and some patients cannot use it because the cannula does not fit. It also does not provide pulmonary support. Finally, it is the most expensive of the 3 right-sided devices.

CASE REVISITED

The patient described at the beginning of this article was extubated on day 12 but was then reintubated. On day 20, a tracheotomy tube was placed. By day 24, he had improved so little that his family signed a “do-not-resuscitate–comfort-care-arrest” order (ie, if the patient’s heart or breathing stops, only comfort care is to be provided).

But slowly he got better, and the Impella was removed on day 30. Afterward, serum creatinine and liver function tests began rising again, requiring dobutamine for heart support.

On day 34, his family reversed the do-not-resuscitate order, and he was reevaluated for an LVAD as destination therapy. At this point, echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 10%, normal right ventricular function, with a normal heartbeat and valves. On day 47, a HeartMate II LVAD was placed.

On postoperative day 18, he was transferred out of the intensive care unit, then discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility 8 days later (hospital day 73). He was subsequently discharged.

At a recent follow-up appointment, the patient said that he was feeling “pretty good” and walked with no shortness of breath.

- Reyentovich A, Barghash MH, Hochman JS. Management of refractory cardiogenic shock. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016; 13:481–492.

- Wayangankar SA, Bangalore S, McCoy LA, et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions for cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a report from the CathPCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 9:341–351.

- Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, et al; CardShock Study Investigators; GREAT network. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17:501–509.

- Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2246–2256.

- Samuels LE, Kaufman MS, Thomas MP, Holmes EC, Brockman SK, Wechsler AS. Pharmacological criteria for ventricular assist device insertion following postcardiotomy shock: experience with the Abiomed BVS system. J Card Surg 1999; 14:288–293.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ventricular assist devices as destination therapy (CAG-00119R2). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=243&ver=9&NcaName=Ventricular+Assist+Devices+as+Destination+Therapy+(2nd+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAAA&&fromdb=true. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Kulkarni T, Sharma NS, Diaz-Guzman E. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: a practical guide for internists. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:373–384.

- Remmelink M, Sjauw KD, Henriques JP, et al. Effects of left ventricular unloading by Impella Recover LP2.5 on coronary hemodynamics. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 70:532–537.

- Aqel RA, Hage FG, Iskandrian AE. Improvement of myocardial perfusion with a percutaneously inserted left ventricular assist device. J Nucl Cardiol 2010; 17:158–160.

- Sarnoff SJ, Braunwald E, Welch Jr GH, Case RB, Stainsby WN, Macruz R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol 1957; 192:148–156.

- Braunwald E. 50th anniversary historical article. Myocardial oxygen consumption: the quest for its determinants and some clinical fallout. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 34:1365–1368.

- Griffith BP, Anderson MB, Samuels LE, Pae WE Jr, Naka Y, Frazier OH. The RECOVER I: A multicenter prospective study of Impella 5.0/LD for postcardiotomy circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145:548–554

- Meyns B, Stolinski J, Leunens V, Verbeken E, Flameng W. Left ventricular support by cathteter-mounted axial flow pump reduces infarct size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:1087–1095.

A 43-year-old man presented to a community hospital with acute chest pain and shortness of breath and was diagnosed with anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He was a smoker with a history of alcohol abuse, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and in the past he had undergone percutaneous coronary interventions to the right coronary artery and the first obtuse marginal artery.

Angiography showed total occlusion in the left anterior descending artery, 90% stenosis in the right coronary artery, and mild disease in the left circumflex artery. A drug-eluting stent was placed in the left anterior descending artery, resulting in good blood flow.

However, his left ventricle continued to have severe dysfunction. An intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted. Afterward, computed tomography showed subsegmental pulmonary embolism with congestion. His mean arterial pressure was 60 mm Hg (normal 70–110), central venous pressure 12 mm Hg (3–8), pulmonary artery pressure 38/26 mm Hg (15–30/4–12), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 24 mm Hg (2–15), and cardiac index 1.4 L/min (2.5–4).

The patient was started on dobutamine and norepinephrine and transferred to Cleveland Clinic on day 2. Over the next day, he had runs of ventricular tachycardia, for which he was given amiodarone and lidocaine. His urine output was low, and his serum creatinine was elevated at 1.65 mg/dL (baseline 1.2, normal 0.5–1.5). Liver function tests were also elevated, with aspartate aminotransferase at 115 U/L(14–40) and alanine aminotransferase at 187 U/L (10–54).

Poor oxygenation was evident: his arterial partial pressure of oxygen was 64 mm Hg (normal 75–100). He was intubated and given 100% oxygen with positive end-expiratory pressure of 12 cm H2O.

Echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 15% (normal 55%–70%) and mild right ventricular dysfunction.

ECMO and then Impella placement

On his third hospital day, a venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device was placed peripherally (Figure 1).

His hemodynamic variables stabilized, and he was weaned off dobutamine and norepinephrine. Results of liver function tests normalized, his urinary output increased, and his serum creatinine dropped to a normal 1.0 mg/dL. However, a chest radiograph showed pulmonary congestion, and echocardiography now showed severe left ventricular dysfunction.

On hospital day 5, the patient underwent surgical placement of an Impella 5.0 device (Abiomed, Danvers, MA) through the right axillary artery in an effort to improve his pulmonary edema. The ECMO device was removed. Placement of a venovenous ECMO device was deemed unnecessary when oxygenation improved with the Impella.

Three days after Impella placement, radiography showed improved edema with some remaining pleural effusion.

ACUTE CARDIOGENIC SHOCK

Cardiogenic shock remains a challenging clinical problem: patients with it are among the sickest in the hospital, and many of them die. ECMO was once the only therapy available and is still widely used. However, it is a 2-edged sword; complications such as bleeding, infection, and thrombosis are almost inevitable if it is used for long. Importantly, patients are usually kept intubated and bedridden.

In recent years, new devices have become available that are easier to place (some in the catheterization laboratory or even at the bedside) and allow safer bridging to recovery, transplant, or other therapies.

This case illustrates the natural history of cardiogenic shock and the preferred clinical approach: ie, ongoing evaluation that permits rapid response to evolving challenges.

In general, acute cardiogenic shock occurs within 24 to 48 hours after the initial insult, so even if a procedure succeeds, the patient may develop progressive hypotension and organ dysfunction. Reduced cardiac output causes a downward spiral with multiple systemic and inflammatory processes as well as increased nitric oxide synthesis, leading to progressive decline and eventual end-organ dysfunction.

Continuously evaluate

The cardiac team should continuously assess the acuity and severity of a patient’s condition, with the goals of maintaining end-organ perfusion and identifying the source of problems. Refractory cardiogenic shock, with tissue hypoperfusion despite vasoactive medications and treatment of the underlying cause, is associated with in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 30% to 50%.1,2 The rates have actually increased over the past decade, as sicker patients are being treated.

When a patient presents with cardiogenic shock, we first try a series of vasoactive drugs and usually an intra-aortic balloon pump (Figure 2). We then tailor treatment depending on etiology. For example, a patient may have viral myocarditis and may even require a biopsy.

If cardiogenic shock is refractory, mechanical circulatory support devices can be a short-term bridge to either recovery or a new decision. A multidisciplinary team should be consulted to consider transplant, a long-term device, or palliative care. Sometimes a case requires “bridging to a bridge,” with several devices used short-term in turn.

Prognostic factors in cardiogenic shock

Several tools help predict outcome in a severely ill patient. End-organ function, indicated by blood lactate levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate, is perhaps the most informative and should be monitored serially.

CardShock3 is a simple scoring system based on age, mental status at presentation, laboratory values, and medical history. Patients receive 1 point for each of the following factors:

- Age > 75

- Confusion at presentation

- Previous myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting

- Acute coronary syndrome etiology

- Left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%

- Blood lactate level between 2 and 4 mmol/L, inclusively (2 points for lactate levels > 4 mmol/L)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, inclusively (2 points if < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Thus, scores range from 0 (best) to 9 (worst). A score of 0 to 3 points was associated with a 9% risk of death in the hospital, a score of 4 or 5 with a risk of 36%, and a score of 6 through 9 with a risk of 77%.3

The Survival After Veno-arterial ECMO (SAVE) score (www.save-score.com) is a prediction tool derived from a large international ECMO registry.4 It is based on patient age, diagnosis, and indicators of end-organ dysfunction. Scores range from –35 (worst) to +7 (best).

The mortality rate associated with postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock increases with the amount of inotropic support provided. In a 1996–1999 case series of patients who underwent open-heart surgery,5 the hospital mortality rate was 40% in those who received 2 inotropes in high doses and 80% in those who received 3. A strategy of early implementation of mechanical support is critical.

Selection criteria for destination therapy

Deciding whether a patient should receive a long-term device is frequently a challenge. The decision often must be based on limited information about not only the medical indications but also psychosocial factors that influence long-term success.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have established criteria for candidates for left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as destination therapy.6 Contraindications established for heart transplant should also be considered (Table 1).

CASE REVISITED

Several factors argued against LVAD placement in our patient. He had no health insurance and had been off medications. He smoked and said he consumed 3 hard liquor drinks per week. His Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation score was 30 (minimally acceptable). He had hypoxia with subsegmental pulmonary edema, a strong contraindication to immediate transplant.

On the other hand, he had only mild right ventricular dysfunction. His CardShock score was 4 (intermediate risk, based on lactate 1.5 mmol/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate 52 mL/min/1.73 m2). His SAVE score was –9 (class IV), which overall is associated with a 30% risk of death (low enough to consider treatment).

During the patient’s time on temporary support, the team had the opportunity to better understand him and assess his family support and his ability to handle a permanent device. His surviving the acute course bolstered the team’s confidence that he could enjoy long-term survival with destination therapy.

CATHETERIZATION LABORATORY DEVICE CAPABILITIES

Although most implantation procedures are done in the operating room, they are often done in the catheterization laboratory because patients undergoing catheterization may not be stable enough for transfer, or an emergency intervention may be required during the night. Catheterization interventionists are also an important part of the team to help determine the best approach for long-term therapy.

The catheterization laboratory has multiple acute intervention options. Usually, decisions must be made quickly. In general, patients needing mechanical support are managed as follows:

- Those who need circulation support and oxygenation receive ECMO

- Those who need circulation support alone because of mechanical issues (eg, myocardial infarction) are considered for an intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, or TandemHeart pump (Cardiac Assist, Pittsburgh, PA).

Factors that guide the selection of a temporary pump include:

- Left ventricular function

- Right ventricular function

- Aortic valve stenosis (some devices cannot be inserted through critical aortic stenosis)

- Aortic regurgitation (can affect some devices)

- Peripheral artery disease (some devices are large and must be placed percutaneously).

CHOOSING AMONG PERCUTANEOUS DEVICES

Circulatory support in cardiogenic shock improves outcomes, and devices play an important role in supporting high-risk procedures. The goal is not necessarily to use the device throughout the hospital stay. Acute stabilization is most important initially; a more considered decision about long-term therapy can be made when more is known about the patient.

Patient selection is the most important component of success. However, randomized data to support outcomes with the various devices are sparse and complicated by the critically ill state of the patient population.

SHORT-TERM CIRCULATORY SUPPORT: ECMO, IMPELLA, TANDEMHEART

A menu of options is available for temporary mechanical support. Options differ by their degree of circulatory support and ease of insertion (Table 2).

ECMO: A fast option with many advantages

ECMO has evolved and now can be placed quickly. A remote diagnostic platform such as CardioHub permits management at the bedside, in the medical unit, or in the cardiac intensive care unit.7

ECMO has several advantages. It can be used during cardiopulmonary bypass, it provides oxygenation, it is the only option in the setting of lung injury, it can be placed peripherally (without thoracotomy), and it is the only percutaneous option for biventricular support.

ECMO also has significant disadvantages

ECMO is a good device for acute resuscitation of a patient in shock, as it offers quick placement and resuscitation. But it is falling out of favor because of significant disadvantages.

Its major drawback is that it provides no left ventricular unloading. Although in a very unstable patient ECMO can stabilize end organs and restore their function, the lack of left ventricular unloading and reduced ventricular work threaten the myocardium. It creates extremely high afterload; therefore, in a left ventricle with poor function, wall tension and myocardial oxygen demand increase. Multiple studies have shown that coronary perfusion worsens, especially if the patient is cannulated peripherally. Because relative cerebral hypoxia occurs in many situations, it is imperative to check blood saturations at multiple sites to determine if perfusion is adequate everywhere.

Ineffective left ventricular unloading with venoarterial ECMO is managed in several ways. Sometimes left ventricular distention is slight and the effects are subtle. Left ventricular distention causing pulmonary edema can be addressed with:

- Inotropes (in moderate doses)

- Anticoagulation to prevent left ventricular thrombus formation

- An intra-aortic balloon pump. Most patients on ECMO already have an intra-aortic balloon pump in place, and it should be left in to provide additional support. For those who do not have one, it should be placed via the contralateral femoral artery.

If problems persist despite these measures, apical cannulation or left ventricular septostomy can be performed.

Outcomes with ECMO have been disappointing. Studies show that whether ECMO was indicated for cardiac failure or for respiratory failure, survival is only about 25% at 5 years. Analyzing data only for arteriovenous ECMO, survival was 48% in bridged patients and 41% in patients who were weaned.

The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry, in their international summary from 2010, found that 34% of cardiac patients on ECMO survived to discharge or transfer. Most of these patients had cardiogenic shock from acute myocardial infarction. Outcomes are so poor because of complications endemic to ECMO, eg, dialysis-dependent renal failure (about 40%) and neurologic complications (about 30%), often involving ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Limb and pump complications were also significant in the past. These have been reduced with the new reperfusion cannula and the Quadrox oxygenator.

Complications unique to ECMO should be understood and anticipated so that they can be avoided. Better tools are available, ie, Impella and TandemHeart.

Left-sided Impella: A longer-term temporary support

ECMO is a temporary fix that is usually used only for a few days. If longer support is needed, axillary placement of an Impella should be used as a bridge to recovery, transplant, or a durable LVAD.

The Impella device (Figure 3) is a miniature rotary blood pump increasingly used to treat cardiogenic shock. It is inserted retrograde across the aortic valve to provide short-term ventricular support. Most devices are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for less than 7 days of use, but we have experience using them up to 30 days. They are very hemocompatible, involving minimal hemolysis. Axillary placement allows early extubation and ambulation and is more stable than groin placement.

Several models are available: the 2.5 and 3.5 L/min devices can be placed percutaneously, while the 5 L/min model must be surgically placed in the axillary or groin region. Heparin is required with their use. They can replace ECMO. A right ventricular assist device (RVAD), Impella RP, is also available.

Physiologic impact of the Impella

The Impella fully unloads the left ventricle, reducing myocardial oxygen demand and increasing myocardial blood flow. It reduces end-diastolic volume and pressure, the mechanical work of the heart, and wall tension. Microvascular resistance is reduced, allowing increased coronary flow. Cardiac output and power are increased by multiple means.8–11

The RECOVER 1 trial evaluated the 5L Impella placed after cardiac surgery. The cardiac index increased in all the patients, and the systemic vascular resistance and wedge pressure decreased.12

Unloading the ventricle is critical. Meyns and colleagues13 found a fivefold reduction in infarct size from baseline in a left anterior descending occlusion model in pigs after off-loading the ventricle.

Impella has the advantage of simple percutaneous insertion (the 2.5 and CP models). It also tests right ventricular tolerance: if the right ventricle is doing well, one can predict with high certainty that it will tolerate an LVAD (eg, HeartWare, HeartMate 2 (Pleasanton, CA), or HeartMate 3 when available).

Disadvantages include that it provides only left ventricular support, although a right ventricular device can be inserted for dual support. Placement requires fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance.

TandemHeart requires septal puncture

The TandemHeart is approved for short-term and biventricular use. It consists of an extracorporeal centrifugal pump that withdraws blood from the left atrium via a trans-septal cannula placed through the femoral vein (Figure 4) and returns it to one or both femoral arteries. The blood is pumped at up to 5 L/min.

It is designed to reduce the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, ventricular work, and myocardial oxygen demand and increase cardiac output and mean arterial pressure. It has the advantages of percutaneous placement and the ability to provide biventricular support with 2 devices. It can be used for up to 3 weeks. It can easily be converted to ECMO by either splicing in an oxygenator or adding another cannula.

Although the TandemHeart provides significant support, it is no longer often used. A 21F venous cannula must be passed to the left atrium by trans-septal puncture, which requires advanced skill and must be done in the catheterization laboratory. Insertion can take too much time and cause bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant. Insertion usually destroys the septum, and removal requires a complete patch of the entire septum. Systemic anticoagulation is required. Other disadvantages are risks of hemolysis, limb ischemia, and infection with longer support times.

The CentriMag (Levitronix LLC; Framingham, MA) is an improved device that requires only 1 cannula instead of 2 to cover both areas.

DEVICES FOR RIGHT-SIDED SUPPORT

Most early devices were designed for left-sided support. The right heart, especially in failure, has been more difficult to manage. Previously the only option for a patient with right ventricular failure was venoarterial ECMO. This is more support than needed for a patient with isolated right ventricular failure and involves the risk of multiple complications from the device.

With more options available for the right heart (Table 3), we can choose the most appropriate device according to the underlying cause of right heart failure (eg, right ventricular infarct, pulmonary hypertension), the likelihood of recovery, and the expected time to recovery.

The ideal RVAD would be easy to implant, maintain, and remove. It would allow for chest closure and patient ambulation. It would be durable and biocompatible, so that it could remain implanted for months if necessary. It would cause little blood trauma, have the capability for adding an oxygenator for pulmonary support, and be cost-effective.

Although no single system has all these qualities, each available device fulfills certain combinations of these criteria, so the best one can be selected for each patient’s needs.

ECMO Rotaflow centrifugal pump: Fast, simple, inexpensive

A recent improvement to ECMO is the Rotaflow centrifugal pump (Maquet, Wayne, NJ), which is connected by sewing an 8-mm graft onto the pulmonary artery and placing a venous cannula in the femoral vein. If the patient is not bleeding, the chest can then be closed. This creates a fast, simple, and inexpensive temporary RVAD system. When the patient is ready to be weaned, the outflow graft can be disconnected at the bedside without reopening the chest.

The disadvantage is that the Rotaflow system contains a sapphire bearing. Although it is magnetically coupled, it generates heat and is a nidus for thrombus formation, which can lead to pump failure and embolization. This system can be used for patients who are expected to need support for less than 5 to 7 days. Beyond this duration, the incidence of complications increases.

CentriMag Ventricular Assist System offers right, left, or bilateral support

The CentriMag Ventricular Assist System is a fully magnetically levitated pump containing no bearings or seals, and with the same technology as is found in many of the durable devices such as HeartMate 3. It is coupled with a reusable motor and is easy to use.

CentriMag offers versatility, allowing for right, left, or bilateral ventricular support. An oxygenator can be added for pulmonary edema and additional support. It is the most biocompatible device and is FDA-approved for use for 4 weeks, although it has been used successfully for much longer. It allows for chest closure and ambulation. It is especially important as a bridge to transplant. The main disadvantage is that insertion and removal require sternotomy.

Impella RP: One size does not fit all

The Impella RP (Figure 5) has an 11F catheter diameter, 23F pump, and a maximum flow rate of more than 4 L/minute. It has a unique 3-dimensional cannula design based on computed tomography 3-dimensional reconstructions from hundreds of patients.

The device is biocompatible and can be used for support for more than 7 days, although most patients require only 3 or 4 days. There is almost no priming volume, so there is no hemodilution.

The disadvantages are that it is more challenging to place than other devices, and some patients cannot use it because the cannula does not fit. It also does not provide pulmonary support. Finally, it is the most expensive of the 3 right-sided devices.

CASE REVISITED

The patient described at the beginning of this article was extubated on day 12 but was then reintubated. On day 20, a tracheotomy tube was placed. By day 24, he had improved so little that his family signed a “do-not-resuscitate–comfort-care-arrest” order (ie, if the patient’s heart or breathing stops, only comfort care is to be provided).

But slowly he got better, and the Impella was removed on day 30. Afterward, serum creatinine and liver function tests began rising again, requiring dobutamine for heart support.

On day 34, his family reversed the do-not-resuscitate order, and he was reevaluated for an LVAD as destination therapy. At this point, echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 10%, normal right ventricular function, with a normal heartbeat and valves. On day 47, a HeartMate II LVAD was placed.

On postoperative day 18, he was transferred out of the intensive care unit, then discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility 8 days later (hospital day 73). He was subsequently discharged.

At a recent follow-up appointment, the patient said that he was feeling “pretty good” and walked with no shortness of breath.

A 43-year-old man presented to a community hospital with acute chest pain and shortness of breath and was diagnosed with anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He was a smoker with a history of alcohol abuse, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and in the past he had undergone percutaneous coronary interventions to the right coronary artery and the first obtuse marginal artery.

Angiography showed total occlusion in the left anterior descending artery, 90% stenosis in the right coronary artery, and mild disease in the left circumflex artery. A drug-eluting stent was placed in the left anterior descending artery, resulting in good blood flow.

However, his left ventricle continued to have severe dysfunction. An intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted. Afterward, computed tomography showed subsegmental pulmonary embolism with congestion. His mean arterial pressure was 60 mm Hg (normal 70–110), central venous pressure 12 mm Hg (3–8), pulmonary artery pressure 38/26 mm Hg (15–30/4–12), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 24 mm Hg (2–15), and cardiac index 1.4 L/min (2.5–4).

The patient was started on dobutamine and norepinephrine and transferred to Cleveland Clinic on day 2. Over the next day, he had runs of ventricular tachycardia, for which he was given amiodarone and lidocaine. His urine output was low, and his serum creatinine was elevated at 1.65 mg/dL (baseline 1.2, normal 0.5–1.5). Liver function tests were also elevated, with aspartate aminotransferase at 115 U/L(14–40) and alanine aminotransferase at 187 U/L (10–54).

Poor oxygenation was evident: his arterial partial pressure of oxygen was 64 mm Hg (normal 75–100). He was intubated and given 100% oxygen with positive end-expiratory pressure of 12 cm H2O.

Echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 15% (normal 55%–70%) and mild right ventricular dysfunction.

ECMO and then Impella placement

On his third hospital day, a venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device was placed peripherally (Figure 1).

His hemodynamic variables stabilized, and he was weaned off dobutamine and norepinephrine. Results of liver function tests normalized, his urinary output increased, and his serum creatinine dropped to a normal 1.0 mg/dL. However, a chest radiograph showed pulmonary congestion, and echocardiography now showed severe left ventricular dysfunction.

On hospital day 5, the patient underwent surgical placement of an Impella 5.0 device (Abiomed, Danvers, MA) through the right axillary artery in an effort to improve his pulmonary edema. The ECMO device was removed. Placement of a venovenous ECMO device was deemed unnecessary when oxygenation improved with the Impella.

Three days after Impella placement, radiography showed improved edema with some remaining pleural effusion.

ACUTE CARDIOGENIC SHOCK

Cardiogenic shock remains a challenging clinical problem: patients with it are among the sickest in the hospital, and many of them die. ECMO was once the only therapy available and is still widely used. However, it is a 2-edged sword; complications such as bleeding, infection, and thrombosis are almost inevitable if it is used for long. Importantly, patients are usually kept intubated and bedridden.

In recent years, new devices have become available that are easier to place (some in the catheterization laboratory or even at the bedside) and allow safer bridging to recovery, transplant, or other therapies.

This case illustrates the natural history of cardiogenic shock and the preferred clinical approach: ie, ongoing evaluation that permits rapid response to evolving challenges.

In general, acute cardiogenic shock occurs within 24 to 48 hours after the initial insult, so even if a procedure succeeds, the patient may develop progressive hypotension and organ dysfunction. Reduced cardiac output causes a downward spiral with multiple systemic and inflammatory processes as well as increased nitric oxide synthesis, leading to progressive decline and eventual end-organ dysfunction.

Continuously evaluate

The cardiac team should continuously assess the acuity and severity of a patient’s condition, with the goals of maintaining end-organ perfusion and identifying the source of problems. Refractory cardiogenic shock, with tissue hypoperfusion despite vasoactive medications and treatment of the underlying cause, is associated with in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 30% to 50%.1,2 The rates have actually increased over the past decade, as sicker patients are being treated.

When a patient presents with cardiogenic shock, we first try a series of vasoactive drugs and usually an intra-aortic balloon pump (Figure 2). We then tailor treatment depending on etiology. For example, a patient may have viral myocarditis and may even require a biopsy.

If cardiogenic shock is refractory, mechanical circulatory support devices can be a short-term bridge to either recovery or a new decision. A multidisciplinary team should be consulted to consider transplant, a long-term device, or palliative care. Sometimes a case requires “bridging to a bridge,” with several devices used short-term in turn.

Prognostic factors in cardiogenic shock

Several tools help predict outcome in a severely ill patient. End-organ function, indicated by blood lactate levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate, is perhaps the most informative and should be monitored serially.

CardShock3 is a simple scoring system based on age, mental status at presentation, laboratory values, and medical history. Patients receive 1 point for each of the following factors:

- Age > 75

- Confusion at presentation

- Previous myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting

- Acute coronary syndrome etiology

- Left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%

- Blood lactate level between 2 and 4 mmol/L, inclusively (2 points for lactate levels > 4 mmol/L)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, inclusively (2 points if < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Thus, scores range from 0 (best) to 9 (worst). A score of 0 to 3 points was associated with a 9% risk of death in the hospital, a score of 4 or 5 with a risk of 36%, and a score of 6 through 9 with a risk of 77%.3

The Survival After Veno-arterial ECMO (SAVE) score (www.save-score.com) is a prediction tool derived from a large international ECMO registry.4 It is based on patient age, diagnosis, and indicators of end-organ dysfunction. Scores range from –35 (worst) to +7 (best).

The mortality rate associated with postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock increases with the amount of inotropic support provided. In a 1996–1999 case series of patients who underwent open-heart surgery,5 the hospital mortality rate was 40% in those who received 2 inotropes in high doses and 80% in those who received 3. A strategy of early implementation of mechanical support is critical.

Selection criteria for destination therapy

Deciding whether a patient should receive a long-term device is frequently a challenge. The decision often must be based on limited information about not only the medical indications but also psychosocial factors that influence long-term success.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have established criteria for candidates for left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as destination therapy.6 Contraindications established for heart transplant should also be considered (Table 1).

CASE REVISITED

Several factors argued against LVAD placement in our patient. He had no health insurance and had been off medications. He smoked and said he consumed 3 hard liquor drinks per week. His Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation score was 30 (minimally acceptable). He had hypoxia with subsegmental pulmonary edema, a strong contraindication to immediate transplant.

On the other hand, he had only mild right ventricular dysfunction. His CardShock score was 4 (intermediate risk, based on lactate 1.5 mmol/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate 52 mL/min/1.73 m2). His SAVE score was –9 (class IV), which overall is associated with a 30% risk of death (low enough to consider treatment).

During the patient’s time on temporary support, the team had the opportunity to better understand him and assess his family support and his ability to handle a permanent device. His surviving the acute course bolstered the team’s confidence that he could enjoy long-term survival with destination therapy.

CATHETERIZATION LABORATORY DEVICE CAPABILITIES

Although most implantation procedures are done in the operating room, they are often done in the catheterization laboratory because patients undergoing catheterization may not be stable enough for transfer, or an emergency intervention may be required during the night. Catheterization interventionists are also an important part of the team to help determine the best approach for long-term therapy.

The catheterization laboratory has multiple acute intervention options. Usually, decisions must be made quickly. In general, patients needing mechanical support are managed as follows:

- Those who need circulation support and oxygenation receive ECMO

- Those who need circulation support alone because of mechanical issues (eg, myocardial infarction) are considered for an intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, or TandemHeart pump (Cardiac Assist, Pittsburgh, PA).

Factors that guide the selection of a temporary pump include:

- Left ventricular function

- Right ventricular function

- Aortic valve stenosis (some devices cannot be inserted through critical aortic stenosis)

- Aortic regurgitation (can affect some devices)

- Peripheral artery disease (some devices are large and must be placed percutaneously).

CHOOSING AMONG PERCUTANEOUS DEVICES

Circulatory support in cardiogenic shock improves outcomes, and devices play an important role in supporting high-risk procedures. The goal is not necessarily to use the device throughout the hospital stay. Acute stabilization is most important initially; a more considered decision about long-term therapy can be made when more is known about the patient.

Patient selection is the most important component of success. However, randomized data to support outcomes with the various devices are sparse and complicated by the critically ill state of the patient population.

SHORT-TERM CIRCULATORY SUPPORT: ECMO, IMPELLA, TANDEMHEART

A menu of options is available for temporary mechanical support. Options differ by their degree of circulatory support and ease of insertion (Table 2).

ECMO: A fast option with many advantages

ECMO has evolved and now can be placed quickly. A remote diagnostic platform such as CardioHub permits management at the bedside, in the medical unit, or in the cardiac intensive care unit.7

ECMO has several advantages. It can be used during cardiopulmonary bypass, it provides oxygenation, it is the only option in the setting of lung injury, it can be placed peripherally (without thoracotomy), and it is the only percutaneous option for biventricular support.

ECMO also has significant disadvantages

ECMO is a good device for acute resuscitation of a patient in shock, as it offers quick placement and resuscitation. But it is falling out of favor because of significant disadvantages.

Its major drawback is that it provides no left ventricular unloading. Although in a very unstable patient ECMO can stabilize end organs and restore their function, the lack of left ventricular unloading and reduced ventricular work threaten the myocardium. It creates extremely high afterload; therefore, in a left ventricle with poor function, wall tension and myocardial oxygen demand increase. Multiple studies have shown that coronary perfusion worsens, especially if the patient is cannulated peripherally. Because relative cerebral hypoxia occurs in many situations, it is imperative to check blood saturations at multiple sites to determine if perfusion is adequate everywhere.

Ineffective left ventricular unloading with venoarterial ECMO is managed in several ways. Sometimes left ventricular distention is slight and the effects are subtle. Left ventricular distention causing pulmonary edema can be addressed with:

- Inotropes (in moderate doses)

- Anticoagulation to prevent left ventricular thrombus formation

- An intra-aortic balloon pump. Most patients on ECMO already have an intra-aortic balloon pump in place, and it should be left in to provide additional support. For those who do not have one, it should be placed via the contralateral femoral artery.

If problems persist despite these measures, apical cannulation or left ventricular septostomy can be performed.

Outcomes with ECMO have been disappointing. Studies show that whether ECMO was indicated for cardiac failure or for respiratory failure, survival is only about 25% at 5 years. Analyzing data only for arteriovenous ECMO, survival was 48% in bridged patients and 41% in patients who were weaned.

The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry, in their international summary from 2010, found that 34% of cardiac patients on ECMO survived to discharge or transfer. Most of these patients had cardiogenic shock from acute myocardial infarction. Outcomes are so poor because of complications endemic to ECMO, eg, dialysis-dependent renal failure (about 40%) and neurologic complications (about 30%), often involving ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Limb and pump complications were also significant in the past. These have been reduced with the new reperfusion cannula and the Quadrox oxygenator.

Complications unique to ECMO should be understood and anticipated so that they can be avoided. Better tools are available, ie, Impella and TandemHeart.

Left-sided Impella: A longer-term temporary support

ECMO is a temporary fix that is usually used only for a few days. If longer support is needed, axillary placement of an Impella should be used as a bridge to recovery, transplant, or a durable LVAD.

The Impella device (Figure 3) is a miniature rotary blood pump increasingly used to treat cardiogenic shock. It is inserted retrograde across the aortic valve to provide short-term ventricular support. Most devices are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for less than 7 days of use, but we have experience using them up to 30 days. They are very hemocompatible, involving minimal hemolysis. Axillary placement allows early extubation and ambulation and is more stable than groin placement.

Several models are available: the 2.5 and 3.5 L/min devices can be placed percutaneously, while the 5 L/min model must be surgically placed in the axillary or groin region. Heparin is required with their use. They can replace ECMO. A right ventricular assist device (RVAD), Impella RP, is also available.

Physiologic impact of the Impella

The Impella fully unloads the left ventricle, reducing myocardial oxygen demand and increasing myocardial blood flow. It reduces end-diastolic volume and pressure, the mechanical work of the heart, and wall tension. Microvascular resistance is reduced, allowing increased coronary flow. Cardiac output and power are increased by multiple means.8–11

The RECOVER 1 trial evaluated the 5L Impella placed after cardiac surgery. The cardiac index increased in all the patients, and the systemic vascular resistance and wedge pressure decreased.12

Unloading the ventricle is critical. Meyns and colleagues13 found a fivefold reduction in infarct size from baseline in a left anterior descending occlusion model in pigs after off-loading the ventricle.

Impella has the advantage of simple percutaneous insertion (the 2.5 and CP models). It also tests right ventricular tolerance: if the right ventricle is doing well, one can predict with high certainty that it will tolerate an LVAD (eg, HeartWare, HeartMate 2 (Pleasanton, CA), or HeartMate 3 when available).

Disadvantages include that it provides only left ventricular support, although a right ventricular device can be inserted for dual support. Placement requires fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance.

TandemHeart requires septal puncture

The TandemHeart is approved for short-term and biventricular use. It consists of an extracorporeal centrifugal pump that withdraws blood from the left atrium via a trans-septal cannula placed through the femoral vein (Figure 4) and returns it to one or both femoral arteries. The blood is pumped at up to 5 L/min.

It is designed to reduce the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, ventricular work, and myocardial oxygen demand and increase cardiac output and mean arterial pressure. It has the advantages of percutaneous placement and the ability to provide biventricular support with 2 devices. It can be used for up to 3 weeks. It can easily be converted to ECMO by either splicing in an oxygenator or adding another cannula.

Although the TandemHeart provides significant support, it is no longer often used. A 21F venous cannula must be passed to the left atrium by trans-septal puncture, which requires advanced skill and must be done in the catheterization laboratory. Insertion can take too much time and cause bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant. Insertion usually destroys the septum, and removal requires a complete patch of the entire septum. Systemic anticoagulation is required. Other disadvantages are risks of hemolysis, limb ischemia, and infection with longer support times.

The CentriMag (Levitronix LLC; Framingham, MA) is an improved device that requires only 1 cannula instead of 2 to cover both areas.

DEVICES FOR RIGHT-SIDED SUPPORT

Most early devices were designed for left-sided support. The right heart, especially in failure, has been more difficult to manage. Previously the only option for a patient with right ventricular failure was venoarterial ECMO. This is more support than needed for a patient with isolated right ventricular failure and involves the risk of multiple complications from the device.

With more options available for the right heart (Table 3), we can choose the most appropriate device according to the underlying cause of right heart failure (eg, right ventricular infarct, pulmonary hypertension), the likelihood of recovery, and the expected time to recovery.

The ideal RVAD would be easy to implant, maintain, and remove. It would allow for chest closure and patient ambulation. It would be durable and biocompatible, so that it could remain implanted for months if necessary. It would cause little blood trauma, have the capability for adding an oxygenator for pulmonary support, and be cost-effective.

Although no single system has all these qualities, each available device fulfills certain combinations of these criteria, so the best one can be selected for each patient’s needs.

ECMO Rotaflow centrifugal pump: Fast, simple, inexpensive

A recent improvement to ECMO is the Rotaflow centrifugal pump (Maquet, Wayne, NJ), which is connected by sewing an 8-mm graft onto the pulmonary artery and placing a venous cannula in the femoral vein. If the patient is not bleeding, the chest can then be closed. This creates a fast, simple, and inexpensive temporary RVAD system. When the patient is ready to be weaned, the outflow graft can be disconnected at the bedside without reopening the chest.

The disadvantage is that the Rotaflow system contains a sapphire bearing. Although it is magnetically coupled, it generates heat and is a nidus for thrombus formation, which can lead to pump failure and embolization. This system can be used for patients who are expected to need support for less than 5 to 7 days. Beyond this duration, the incidence of complications increases.

CentriMag Ventricular Assist System offers right, left, or bilateral support

The CentriMag Ventricular Assist System is a fully magnetically levitated pump containing no bearings or seals, and with the same technology as is found in many of the durable devices such as HeartMate 3. It is coupled with a reusable motor and is easy to use.

CentriMag offers versatility, allowing for right, left, or bilateral ventricular support. An oxygenator can be added for pulmonary edema and additional support. It is the most biocompatible device and is FDA-approved for use for 4 weeks, although it has been used successfully for much longer. It allows for chest closure and ambulation. It is especially important as a bridge to transplant. The main disadvantage is that insertion and removal require sternotomy.

Impella RP: One size does not fit all

The Impella RP (Figure 5) has an 11F catheter diameter, 23F pump, and a maximum flow rate of more than 4 L/minute. It has a unique 3-dimensional cannula design based on computed tomography 3-dimensional reconstructions from hundreds of patients.

The device is biocompatible and can be used for support for more than 7 days, although most patients require only 3 or 4 days. There is almost no priming volume, so there is no hemodilution.

The disadvantages are that it is more challenging to place than other devices, and some patients cannot use it because the cannula does not fit. It also does not provide pulmonary support. Finally, it is the most expensive of the 3 right-sided devices.

CASE REVISITED

The patient described at the beginning of this article was extubated on day 12 but was then reintubated. On day 20, a tracheotomy tube was placed. By day 24, he had improved so little that his family signed a “do-not-resuscitate–comfort-care-arrest” order (ie, if the patient’s heart or breathing stops, only comfort care is to be provided).

But slowly he got better, and the Impella was removed on day 30. Afterward, serum creatinine and liver function tests began rising again, requiring dobutamine for heart support.

On day 34, his family reversed the do-not-resuscitate order, and he was reevaluated for an LVAD as destination therapy. At this point, echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 10%, normal right ventricular function, with a normal heartbeat and valves. On day 47, a HeartMate II LVAD was placed.

On postoperative day 18, he was transferred out of the intensive care unit, then discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility 8 days later (hospital day 73). He was subsequently discharged.

At a recent follow-up appointment, the patient said that he was feeling “pretty good” and walked with no shortness of breath.

- Reyentovich A, Barghash MH, Hochman JS. Management of refractory cardiogenic shock. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016; 13:481–492.

- Wayangankar SA, Bangalore S, McCoy LA, et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions for cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a report from the CathPCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 9:341–351.

- Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, et al; CardShock Study Investigators; GREAT network. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17:501–509.

- Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2246–2256.

- Samuels LE, Kaufman MS, Thomas MP, Holmes EC, Brockman SK, Wechsler AS. Pharmacological criteria for ventricular assist device insertion following postcardiotomy shock: experience with the Abiomed BVS system. J Card Surg 1999; 14:288–293.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ventricular assist devices as destination therapy (CAG-00119R2). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=243&ver=9&NcaName=Ventricular+Assist+Devices+as+Destination+Therapy+(2nd+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAAA&&fromdb=true. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Kulkarni T, Sharma NS, Diaz-Guzman E. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: a practical guide for internists. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:373–384.

- Remmelink M, Sjauw KD, Henriques JP, et al. Effects of left ventricular unloading by Impella Recover LP2.5 on coronary hemodynamics. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 70:532–537.

- Aqel RA, Hage FG, Iskandrian AE. Improvement of myocardial perfusion with a percutaneously inserted left ventricular assist device. J Nucl Cardiol 2010; 17:158–160.

- Sarnoff SJ, Braunwald E, Welch Jr GH, Case RB, Stainsby WN, Macruz R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol 1957; 192:148–156.

- Braunwald E. 50th anniversary historical article. Myocardial oxygen consumption: the quest for its determinants and some clinical fallout. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 34:1365–1368.

- Griffith BP, Anderson MB, Samuels LE, Pae WE Jr, Naka Y, Frazier OH. The RECOVER I: A multicenter prospective study of Impella 5.0/LD for postcardiotomy circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145:548–554

- Meyns B, Stolinski J, Leunens V, Verbeken E, Flameng W. Left ventricular support by cathteter-mounted axial flow pump reduces infarct size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:1087–1095.

- Reyentovich A, Barghash MH, Hochman JS. Management of refractory cardiogenic shock. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016; 13:481–492.

- Wayangankar SA, Bangalore S, McCoy LA, et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions for cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a report from the CathPCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 9:341–351.

- Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, et al; CardShock Study Investigators; GREAT network. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17:501–509.

- Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2246–2256.

- Samuels LE, Kaufman MS, Thomas MP, Holmes EC, Brockman SK, Wechsler AS. Pharmacological criteria for ventricular assist device insertion following postcardiotomy shock: experience with the Abiomed BVS system. J Card Surg 1999; 14:288–293.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ventricular assist devices as destination therapy (CAG-00119R2). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=243&ver=9&NcaName=Ventricular+Assist+Devices+as+Destination+Therapy+(2nd+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAAA&&fromdb=true. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Kulkarni T, Sharma NS, Diaz-Guzman E. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: a practical guide for internists. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:373–384.

- Remmelink M, Sjauw KD, Henriques JP, et al. Effects of left ventricular unloading by Impella Recover LP2.5 on coronary hemodynamics. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 70:532–537.

- Aqel RA, Hage FG, Iskandrian AE. Improvement of myocardial perfusion with a percutaneously inserted left ventricular assist device. J Nucl Cardiol 2010; 17:158–160.

- Sarnoff SJ, Braunwald E, Welch Jr GH, Case RB, Stainsby WN, Macruz R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol 1957; 192:148–156.

- Braunwald E. 50th anniversary historical article. Myocardial oxygen consumption: the quest for its determinants and some clinical fallout. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 34:1365–1368.

- Griffith BP, Anderson MB, Samuels LE, Pae WE Jr, Naka Y, Frazier OH. The RECOVER I: A multicenter prospective study of Impella 5.0/LD for postcardiotomy circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145:548–554

- Meyns B, Stolinski J, Leunens V, Verbeken E, Flameng W. Left ventricular support by cathteter-mounted axial flow pump reduces infarct size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:1087–1095.

KEY POINTS

- ECMO is the fastest way to stabilize a patient in acute cardiogenic shock and prevent end-organ failure, but it should likely be used for a short time and does not reduce the work of (“unload”) the left ventricle.

- An intra-aortic balloon pump may provide diastolic filling in a patient on ECMO.

- The TandemHeart provides significant support, but its insertion requires puncture of the atrial septum.

- The Impella fully unloads the left ventricle, critically reducing the work of the heart.

- Options for right-ventricular support include the ECMO Rotaflow circuit, CentriMag, and Impella RP.

- The CentriMag is the most versatile device, allowing right, left, or biventricular support, but placement requires sternotomy.

Confusion and hypercalcemia in an 80-year-old man

A retired 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department after 10 days of increasing polydipsia, polyuria, dry mouth, confusion, and slurred speech. He also reported that he had gradually and unintentionally lost 20 pounds and had loss of appetite, constipation, and chronic itching. He denied fevers, chills, night sweats, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Medical history. He had type 2 diabetes mellitus that was well controlled by oral hypoglycemics, hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine in stable doses, and chronic hepatitis C complicated by liver cirrhosis without focal hepatic lesions. He also had hypertension, well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide and losartan. For his long-standing pruritus he had tried prescription drugs including gabapentin and pregabalin without improvement. He had also seen a naturopathic practitioner, who had prescribed supplements that relieved the symptoms.

Examination. The patient was in no acute distress. He appeared thin, with a weight of 140 lb and a body mass index of 21 kg/m2. His temperature was 36.8°C (98.2°F), blood pressure 198/82 mm Hg, heart rate 72 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97%. His skin was without jaundice or rashes. The mucous membranes in the oropharynx were dry.

Neurologic examination revealed mild confusion, dysarthria, and ataxic gait. Sensation to light touch, pinprick, and vibration was intact. Generalized weakness was noted. Cranial nerves II through XII were intact. Deep tendon reflexes were symmetrically globally suppressed. Asterixis was absent. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory values in the emergency department. We initially suspected he had symptomatic hyperglycemia, but a bedside blood glucose value of 113 mg/dL ruled this out. Other initial laboratory values:

- Blood urea nitrogen 31 mg/dL (reference range 9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dL (0.73–1.22; an earlier value had been 1.0 mg/dL)

- Total serum calcium 14.4 mg/dL (8.6–10.0)