User login

Black women have higher state-level rates of TNBC

New national data on the occurrence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) among different racial groups confirms that the disease is more common among Black women nationwide. A state-by-state analysis in the study, published online in JAMA Oncology, shows that these trends persist at the state level.

The analysis revealed that incidence rate ratios of TNBC were significantly higher among Black women, compared with White women, in all states with data on this population. Rates ranged from a low of 1.38 in Colorado to a high of 2.32 in Delaware.

The state-level disparities highlight gaps in physicians’ understanding of how social factors contribute to disparities in TNBC risk and the need “to develop effective preventative measures,” the study authors explain.

“We’ve realized for a long time that Black women have a higher incidence of TNBC. This is related to the genetic signature of the cancer. So that is not at all surprising,” said Arnold M. Baskies, MD, past chairman of the national board of directors of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, who was not involved in the research. However, “the variance of TNBC among women from state to state is somewhat surprising.”

Existing research shows that TNBC is diagnosed more frequently among non-Hispanic Black women than among other populations in the United States, but it’s unclear whether these racial and ethnic disparities differ at the state level.

The authors identified 133,579 women with TNBC from the U.S. Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database whose conditions were diagnosed from January 2015 through the end of December 2019. Most patients (64.5%) were White, 21.5% were Black, nearly 10% were Hispanic, 3.7% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 0.6% were American Indian or Alaska Native. States with fewer than 30 cases were excluded, as was Nevada, owing to concerns regarding data quality. That left eight states for American Indian or Alaska Natives, 22 for Asian or Pacific Islanders, 35 for Hispanic women, 38 for Black women, and 50 for White women.

Overall, the incidence ratios of TNBC were highest among Black women (IR, 25.2 per 100,000), followed by White women (IR, 12.9 per 100,000), American Indian or Alaska Native women (IR, 11.2 per 100,000), Hispanic women (IR, 11.1 per 100,000 women), and Asian or Pacific Islander (IR, 9.0 per 100,000) women.

The authors also uncovered significant state-by-state variations in TNBC incidence by racial and ethnic groups. The lowest IR rates occurred among Asian or Pacific Islander women in Oregon and Pennsylvania – fewer than 7 per 100,000 women – and the highest occurred among Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi – more than 29 per 100,000 women.

In the 38 states for which data on Black women were available, IR rates were significantly higher among Black women in all 38, compared with White women. The IR rates ranged from a low of 1.38 (IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women) in Colorado to a high of 2.32 (IR, 32.0 per 100 000 women) in Delaware.

While genetics play a role in TNBC risk, “the substantial geographic variation we found within each racial and ethnic group is highly suggestive that there are structural, environmental, and social factors at play in determining women’s risk of TNBC,” said lead study author Hyuna Sung, PhD, senior principal scientist and cancer epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

Existing evidence indicates that Black and White women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are at higher risk of developing more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer, Dr. Sung said. Another factor, Dr. Sung and co-authors note, is breastfeeding. Across races, women who breastfeed have lower rates of TNBC.

Getting more definitive answers as to what causes differences in TNBC rates across states and what strategies can help reduce these disparities will be difficult and requires more research. “We really need to do a better job at researching and treating TNBC to improve health care equality for all women,” Dr. Baskies said. “The mortality rates from this cancer are high, and we rely heavily on surgery and toxic chemotherapy to treat it.”

Dr. Sung agreed, noting that “the observed state variation in TNBC rates merits further studies with risk factor data at multiple levels to better understand the associations of social exposures with the risk of TNBC.”

In states such as Louisiana and Mississippi, which are known to have a disproportionately higher burden of many types of cancers, “addressing barriers to access to preventive care and empowering public health efforts to promote a healthy living environment are the best policy prescription that could be deduced from our results,” Dr. Sung concluded.

Dr. Baskies is on the board of directors of Anixa Biosciences, which is currently conducting a clinical trial of a TNBC vaccine at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Sung has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New national data on the occurrence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) among different racial groups confirms that the disease is more common among Black women nationwide. A state-by-state analysis in the study, published online in JAMA Oncology, shows that these trends persist at the state level.

The analysis revealed that incidence rate ratios of TNBC were significantly higher among Black women, compared with White women, in all states with data on this population. Rates ranged from a low of 1.38 in Colorado to a high of 2.32 in Delaware.

The state-level disparities highlight gaps in physicians’ understanding of how social factors contribute to disparities in TNBC risk and the need “to develop effective preventative measures,” the study authors explain.

“We’ve realized for a long time that Black women have a higher incidence of TNBC. This is related to the genetic signature of the cancer. So that is not at all surprising,” said Arnold M. Baskies, MD, past chairman of the national board of directors of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, who was not involved in the research. However, “the variance of TNBC among women from state to state is somewhat surprising.”

Existing research shows that TNBC is diagnosed more frequently among non-Hispanic Black women than among other populations in the United States, but it’s unclear whether these racial and ethnic disparities differ at the state level.

The authors identified 133,579 women with TNBC from the U.S. Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database whose conditions were diagnosed from January 2015 through the end of December 2019. Most patients (64.5%) were White, 21.5% were Black, nearly 10% were Hispanic, 3.7% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 0.6% were American Indian or Alaska Native. States with fewer than 30 cases were excluded, as was Nevada, owing to concerns regarding data quality. That left eight states for American Indian or Alaska Natives, 22 for Asian or Pacific Islanders, 35 for Hispanic women, 38 for Black women, and 50 for White women.

Overall, the incidence ratios of TNBC were highest among Black women (IR, 25.2 per 100,000), followed by White women (IR, 12.9 per 100,000), American Indian or Alaska Native women (IR, 11.2 per 100,000), Hispanic women (IR, 11.1 per 100,000 women), and Asian or Pacific Islander (IR, 9.0 per 100,000) women.

The authors also uncovered significant state-by-state variations in TNBC incidence by racial and ethnic groups. The lowest IR rates occurred among Asian or Pacific Islander women in Oregon and Pennsylvania – fewer than 7 per 100,000 women – and the highest occurred among Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi – more than 29 per 100,000 women.

In the 38 states for which data on Black women were available, IR rates were significantly higher among Black women in all 38, compared with White women. The IR rates ranged from a low of 1.38 (IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women) in Colorado to a high of 2.32 (IR, 32.0 per 100 000 women) in Delaware.

While genetics play a role in TNBC risk, “the substantial geographic variation we found within each racial and ethnic group is highly suggestive that there are structural, environmental, and social factors at play in determining women’s risk of TNBC,” said lead study author Hyuna Sung, PhD, senior principal scientist and cancer epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

Existing evidence indicates that Black and White women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are at higher risk of developing more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer, Dr. Sung said. Another factor, Dr. Sung and co-authors note, is breastfeeding. Across races, women who breastfeed have lower rates of TNBC.

Getting more definitive answers as to what causes differences in TNBC rates across states and what strategies can help reduce these disparities will be difficult and requires more research. “We really need to do a better job at researching and treating TNBC to improve health care equality for all women,” Dr. Baskies said. “The mortality rates from this cancer are high, and we rely heavily on surgery and toxic chemotherapy to treat it.”

Dr. Sung agreed, noting that “the observed state variation in TNBC rates merits further studies with risk factor data at multiple levels to better understand the associations of social exposures with the risk of TNBC.”

In states such as Louisiana and Mississippi, which are known to have a disproportionately higher burden of many types of cancers, “addressing barriers to access to preventive care and empowering public health efforts to promote a healthy living environment are the best policy prescription that could be deduced from our results,” Dr. Sung concluded.

Dr. Baskies is on the board of directors of Anixa Biosciences, which is currently conducting a clinical trial of a TNBC vaccine at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Sung has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New national data on the occurrence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) among different racial groups confirms that the disease is more common among Black women nationwide. A state-by-state analysis in the study, published online in JAMA Oncology, shows that these trends persist at the state level.

The analysis revealed that incidence rate ratios of TNBC were significantly higher among Black women, compared with White women, in all states with data on this population. Rates ranged from a low of 1.38 in Colorado to a high of 2.32 in Delaware.

The state-level disparities highlight gaps in physicians’ understanding of how social factors contribute to disparities in TNBC risk and the need “to develop effective preventative measures,” the study authors explain.

“We’ve realized for a long time that Black women have a higher incidence of TNBC. This is related to the genetic signature of the cancer. So that is not at all surprising,” said Arnold M. Baskies, MD, past chairman of the national board of directors of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, who was not involved in the research. However, “the variance of TNBC among women from state to state is somewhat surprising.”

Existing research shows that TNBC is diagnosed more frequently among non-Hispanic Black women than among other populations in the United States, but it’s unclear whether these racial and ethnic disparities differ at the state level.

The authors identified 133,579 women with TNBC from the U.S. Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database whose conditions were diagnosed from January 2015 through the end of December 2019. Most patients (64.5%) were White, 21.5% were Black, nearly 10% were Hispanic, 3.7% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 0.6% were American Indian or Alaska Native. States with fewer than 30 cases were excluded, as was Nevada, owing to concerns regarding data quality. That left eight states for American Indian or Alaska Natives, 22 for Asian or Pacific Islanders, 35 for Hispanic women, 38 for Black women, and 50 for White women.

Overall, the incidence ratios of TNBC were highest among Black women (IR, 25.2 per 100,000), followed by White women (IR, 12.9 per 100,000), American Indian or Alaska Native women (IR, 11.2 per 100,000), Hispanic women (IR, 11.1 per 100,000 women), and Asian or Pacific Islander (IR, 9.0 per 100,000) women.

The authors also uncovered significant state-by-state variations in TNBC incidence by racial and ethnic groups. The lowest IR rates occurred among Asian or Pacific Islander women in Oregon and Pennsylvania – fewer than 7 per 100,000 women – and the highest occurred among Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi – more than 29 per 100,000 women.

In the 38 states for which data on Black women were available, IR rates were significantly higher among Black women in all 38, compared with White women. The IR rates ranged from a low of 1.38 (IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women) in Colorado to a high of 2.32 (IR, 32.0 per 100 000 women) in Delaware.

While genetics play a role in TNBC risk, “the substantial geographic variation we found within each racial and ethnic group is highly suggestive that there are structural, environmental, and social factors at play in determining women’s risk of TNBC,” said lead study author Hyuna Sung, PhD, senior principal scientist and cancer epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

Existing evidence indicates that Black and White women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are at higher risk of developing more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer, Dr. Sung said. Another factor, Dr. Sung and co-authors note, is breastfeeding. Across races, women who breastfeed have lower rates of TNBC.

Getting more definitive answers as to what causes differences in TNBC rates across states and what strategies can help reduce these disparities will be difficult and requires more research. “We really need to do a better job at researching and treating TNBC to improve health care equality for all women,” Dr. Baskies said. “The mortality rates from this cancer are high, and we rely heavily on surgery and toxic chemotherapy to treat it.”

Dr. Sung agreed, noting that “the observed state variation in TNBC rates merits further studies with risk factor data at multiple levels to better understand the associations of social exposures with the risk of TNBC.”

In states such as Louisiana and Mississippi, which are known to have a disproportionately higher burden of many types of cancers, “addressing barriers to access to preventive care and empowering public health efforts to promote a healthy living environment are the best policy prescription that could be deduced from our results,” Dr. Sung concluded.

Dr. Baskies is on the board of directors of Anixa Biosciences, which is currently conducting a clinical trial of a TNBC vaccine at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Sung has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Black people are less likely to receive dementia meds

, preliminary data from a retrospective study show.

“There have been disparities regarding the use of cognition-enhancing medications in the treatment of dementia described in the literature, and disparities in the use of adjunctive treatments for other neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia described in hospital and nursing home settings,” said study investigator Alice Hawkins, MD, with the department of neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “However, less is known about use of dementia medications that people take at home. Our study found disparities in this area as well,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

More research needed

The researchers analyzed data on 3,655 Black and 12,885 White patients with a diagnosis of dementia who were seen at Mount Sinai. They evaluated utilization of five medication classes:

- cholinesterase inhibitors.

- N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists.

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- antipsychotics.

- benzodiazepines.

They found that Black patients with dementia received cognitive enhancers less often than White patients with dementia (20% vs. 30% for cholinesterase inhibitors; 10% vs. 17% for NMDA antagonists).

Black patients with dementia were also less likely to receive medications for behavioral and psychological symptom management, compared with White peers (24% vs. 40% for SSRIs; 18% vs. 22% for antipsychotics; and 18% vs. 37% for benzodiazepines).

These disparities remained even after controlling for factors such as demographics and insurance coverage.

“Larger systemic forces such as systemic racism, quality of care, and provider bias are harder to pin down, particularly in the medical record, though they all may be playing a role in perpetuating these inequities. More research will be needed to pinpoint all the factors that are contributing to these disparities,” said Dr. Hawkins.

The researchers found Black patients who were referred to a neurologist received cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists at rates comparable with White patients. “Therefore, referrals to specialists such as neurologists may decrease the disparities for these prescriptions,” Dr. Hawkins said.

Crucial research

Commenting on the findings, Carl V. Hill, PhD, MPH, Alzheimer’s Association chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer, said the study “adds to previous research that points to inequities in the administering of medications for dementia symptoms, and highlights the inequities we know exist in dementia care.”

“Cognitive enhancers and other behavioral/psychological management drugs, while they don’t stop, slow, or cure dementia, can offer relief for some of the challenging symptoms associated with diseases caused by dementia. If people aren’t being appropriately prescribed medications that may offer symptom relief from this challenging disease, it could lead to poorer health outcomes,” said Dr. Hill.

“These data underscore the importance of health disparities research that is crucial in uncovering inequities in dementia treatment, care, and research for Black individuals, as well as all underrepresented populations.

“We must create a society in which the underserved, disproportionately affected, and underrepresented are safe, cared for, and valued. This can be done through enhancing cultural competence in health care settings, improving representation within the health care system, and engaging and building trust with diverse communities,” Dr. Hill said.

The Alzheimer’s Association has partnered with more than 500 diverse community-based groups on disease education programs to ensure families have information and resources to navigate this devastating disease.

The study was supported by the American Academy of Neurology Resident Research Scholarship. Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Hill reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, preliminary data from a retrospective study show.

“There have been disparities regarding the use of cognition-enhancing medications in the treatment of dementia described in the literature, and disparities in the use of adjunctive treatments for other neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia described in hospital and nursing home settings,” said study investigator Alice Hawkins, MD, with the department of neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “However, less is known about use of dementia medications that people take at home. Our study found disparities in this area as well,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

More research needed

The researchers analyzed data on 3,655 Black and 12,885 White patients with a diagnosis of dementia who were seen at Mount Sinai. They evaluated utilization of five medication classes:

- cholinesterase inhibitors.

- N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists.

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- antipsychotics.

- benzodiazepines.

They found that Black patients with dementia received cognitive enhancers less often than White patients with dementia (20% vs. 30% for cholinesterase inhibitors; 10% vs. 17% for NMDA antagonists).

Black patients with dementia were also less likely to receive medications for behavioral and psychological symptom management, compared with White peers (24% vs. 40% for SSRIs; 18% vs. 22% for antipsychotics; and 18% vs. 37% for benzodiazepines).

These disparities remained even after controlling for factors such as demographics and insurance coverage.

“Larger systemic forces such as systemic racism, quality of care, and provider bias are harder to pin down, particularly in the medical record, though they all may be playing a role in perpetuating these inequities. More research will be needed to pinpoint all the factors that are contributing to these disparities,” said Dr. Hawkins.

The researchers found Black patients who were referred to a neurologist received cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists at rates comparable with White patients. “Therefore, referrals to specialists such as neurologists may decrease the disparities for these prescriptions,” Dr. Hawkins said.

Crucial research

Commenting on the findings, Carl V. Hill, PhD, MPH, Alzheimer’s Association chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer, said the study “adds to previous research that points to inequities in the administering of medications for dementia symptoms, and highlights the inequities we know exist in dementia care.”

“Cognitive enhancers and other behavioral/psychological management drugs, while they don’t stop, slow, or cure dementia, can offer relief for some of the challenging symptoms associated with diseases caused by dementia. If people aren’t being appropriately prescribed medications that may offer symptom relief from this challenging disease, it could lead to poorer health outcomes,” said Dr. Hill.

“These data underscore the importance of health disparities research that is crucial in uncovering inequities in dementia treatment, care, and research for Black individuals, as well as all underrepresented populations.

“We must create a society in which the underserved, disproportionately affected, and underrepresented are safe, cared for, and valued. This can be done through enhancing cultural competence in health care settings, improving representation within the health care system, and engaging and building trust with diverse communities,” Dr. Hill said.

The Alzheimer’s Association has partnered with more than 500 diverse community-based groups on disease education programs to ensure families have information and resources to navigate this devastating disease.

The study was supported by the American Academy of Neurology Resident Research Scholarship. Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Hill reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, preliminary data from a retrospective study show.

“There have been disparities regarding the use of cognition-enhancing medications in the treatment of dementia described in the literature, and disparities in the use of adjunctive treatments for other neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia described in hospital and nursing home settings,” said study investigator Alice Hawkins, MD, with the department of neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “However, less is known about use of dementia medications that people take at home. Our study found disparities in this area as well,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

More research needed

The researchers analyzed data on 3,655 Black and 12,885 White patients with a diagnosis of dementia who were seen at Mount Sinai. They evaluated utilization of five medication classes:

- cholinesterase inhibitors.

- N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists.

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- antipsychotics.

- benzodiazepines.

They found that Black patients with dementia received cognitive enhancers less often than White patients with dementia (20% vs. 30% for cholinesterase inhibitors; 10% vs. 17% for NMDA antagonists).

Black patients with dementia were also less likely to receive medications for behavioral and psychological symptom management, compared with White peers (24% vs. 40% for SSRIs; 18% vs. 22% for antipsychotics; and 18% vs. 37% for benzodiazepines).

These disparities remained even after controlling for factors such as demographics and insurance coverage.

“Larger systemic forces such as systemic racism, quality of care, and provider bias are harder to pin down, particularly in the medical record, though they all may be playing a role in perpetuating these inequities. More research will be needed to pinpoint all the factors that are contributing to these disparities,” said Dr. Hawkins.

The researchers found Black patients who were referred to a neurologist received cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists at rates comparable with White patients. “Therefore, referrals to specialists such as neurologists may decrease the disparities for these prescriptions,” Dr. Hawkins said.

Crucial research

Commenting on the findings, Carl V. Hill, PhD, MPH, Alzheimer’s Association chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer, said the study “adds to previous research that points to inequities in the administering of medications for dementia symptoms, and highlights the inequities we know exist in dementia care.”

“Cognitive enhancers and other behavioral/psychological management drugs, while they don’t stop, slow, or cure dementia, can offer relief for some of the challenging symptoms associated with diseases caused by dementia. If people aren’t being appropriately prescribed medications that may offer symptom relief from this challenging disease, it could lead to poorer health outcomes,” said Dr. Hill.

“These data underscore the importance of health disparities research that is crucial in uncovering inequities in dementia treatment, care, and research for Black individuals, as well as all underrepresented populations.

“We must create a society in which the underserved, disproportionately affected, and underrepresented are safe, cared for, and valued. This can be done through enhancing cultural competence in health care settings, improving representation within the health care system, and engaging and building trust with diverse communities,” Dr. Hill said.

The Alzheimer’s Association has partnered with more than 500 diverse community-based groups on disease education programs to ensure families have information and resources to navigate this devastating disease.

The study was supported by the American Academy of Neurology Resident Research Scholarship. Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Hill reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term BP reductions with renal denervation not race specific

WASHINGTON – On the heels the recently published final report from the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 renal denervation trial, a new analysis showed that Black patients, like non-Blacks, had sustained blood pressure control.

Contrary to a signal from earlier results, “there is nothing race specific about renal denervation,” said presenter Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

Black patients are well represented among patients with treatment-resistant hypertension and considered an important subgroup to target, according to Dr. Bhatt, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. This is the reason that they were not only a prespecified subgroup in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, but race was one of two stratification factors at enrollment. At the time of the study design, there was an expectation that Black patients would benefit more than non-Blacks.

This did not prove to be the case during the 6-month controlled phase of the trial. When patients randomized to renal denervation or the sham procedure were stratified by race, the primary endpoint of reduction in office systolic blood pressure (SBP) reached significance in the experimental arm among non-Black patients (–6.63 mm Hg; P = .01), but not among Black patients (–2.25 mm Hg; P = .09).

Blacks comprised 26% of SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial

In the initial controlled analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the lack of benefit in the substantial Black enrollment – representing 26% of the study total – weighed against the ability of the trial to demonstrate a benefit, but Dr. Bhatt pointed out that BP reductions were unexpectedly high in the sham group regardless of race. Patients randomized to the sham group were encouraged to adhere to antihypertensive therapy, and based on response, this was particularly effective in the Black sham subgroup.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, patients with treatment-resistant hypertension were randomized to renal denervation or a sham procedure in a 2:1 ratio. While the controlled phase lasted just 6 months, the follow-up after the study was unblinded has continued out to 3 years. Safety and efficacy were assessed at 12, 24, and 36 months.

Unlike the disappointing results at 6 months, renal denervation has been consistently associated with significantly lower BP over long-term follow-up, even though those randomized to the sham procedure were permitted to cross over. About two-thirds of the sham group did so.

In the recently published final report of SYMPLICITY, the overall median change in office SBP at 3 years regardless of race was –26.4 mm Hg in the group initially randomized to renal denervation versus –5.7 mm Hg (P < .0001) among those randomized to the sham procedure.

In the subgroup analysis presented by Dr. Bhatt, the relative control of office SBP, as well as other measures of blood pressure, were similarly and significantly reduced in both Black and non-Black patients. In general, the relative control offered by being randomized initially to renal denervation increased over time in both groups.

For example, the relative reduction in office SBP favoring renal denervation climbed from –12.0 mm Hg at 12 months (P = .0066) to –21.0 at 18 months (P = .0002) and then to –24.9 mm Hg (P < .0001) at 36 months in the Black subgroup. In non-Blacks, the same type of relative reductions were seen at each time point, climbing from –13.5 (P < .0001) to –20.5 (P < .0001) and then to –21.0 (P < .0001).

The comparisons for other measures of BP control, including office diastolic BP, 24-hour SBP, and BP control during morning, day, and night periods were also statistically and similarly improved for those initially randomized to renal denervation rather than a sham procedure among both Blacks and non-Blacks.

Renal denervation safe in Black and non-Black patients

Renal denervation was well tolerated in both Black and non-Black participants with no signal of long-term risks over 36 months in either group. Among Blacks, rates of death at 36 months (3% vs. 11%) and stroke (7% vs. 11%) were lower among those randomized to renal denervation relative to sham patients who never crossed over, but Dr. Bhatt said the numbers are too small to draw any conclusions about outcomes.

While this subgroup analysis, along with the final SYMPLICITY report, supports the efficacy of renal denervation over the long term, these data are also consistent with the recently published analysis of SPYRAL ON-MED . Together, these data have led many experts, including Dr. Bhatt, to conclude that renal denervation is effective and deserves regulatory approval.

“In out-of-control blood pressure, when patients have maxed out on medications and lifestyle, I think renal denervation is efficacious, and it is equally efficacious in Blacks and non-Blacks,” Dr. Bhatt said.

This subgroup analysis is important because of the need for options in treatment-resistant hypertension among Black as well as non-Black patients, pointed out Sripal Bangalore, MBBS, director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

“I am glad that we did not conclude too soon that it does not work in Blacks,” Dr. Bangalore said. If renal denervation is approved, he expects this procedure to be a valuable tool in this racial group.

Dr. Bhatt reported financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical and device companies, including Medtronic, which provided funding for the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. Dr. Bangalore has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic.

WASHINGTON – On the heels the recently published final report from the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 renal denervation trial, a new analysis showed that Black patients, like non-Blacks, had sustained blood pressure control.

Contrary to a signal from earlier results, “there is nothing race specific about renal denervation,” said presenter Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

Black patients are well represented among patients with treatment-resistant hypertension and considered an important subgroup to target, according to Dr. Bhatt, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. This is the reason that they were not only a prespecified subgroup in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, but race was one of two stratification factors at enrollment. At the time of the study design, there was an expectation that Black patients would benefit more than non-Blacks.

This did not prove to be the case during the 6-month controlled phase of the trial. When patients randomized to renal denervation or the sham procedure were stratified by race, the primary endpoint of reduction in office systolic blood pressure (SBP) reached significance in the experimental arm among non-Black patients (–6.63 mm Hg; P = .01), but not among Black patients (–2.25 mm Hg; P = .09).

Blacks comprised 26% of SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial

In the initial controlled analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the lack of benefit in the substantial Black enrollment – representing 26% of the study total – weighed against the ability of the trial to demonstrate a benefit, but Dr. Bhatt pointed out that BP reductions were unexpectedly high in the sham group regardless of race. Patients randomized to the sham group were encouraged to adhere to antihypertensive therapy, and based on response, this was particularly effective in the Black sham subgroup.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, patients with treatment-resistant hypertension were randomized to renal denervation or a sham procedure in a 2:1 ratio. While the controlled phase lasted just 6 months, the follow-up after the study was unblinded has continued out to 3 years. Safety and efficacy were assessed at 12, 24, and 36 months.

Unlike the disappointing results at 6 months, renal denervation has been consistently associated with significantly lower BP over long-term follow-up, even though those randomized to the sham procedure were permitted to cross over. About two-thirds of the sham group did so.

In the recently published final report of SYMPLICITY, the overall median change in office SBP at 3 years regardless of race was –26.4 mm Hg in the group initially randomized to renal denervation versus –5.7 mm Hg (P < .0001) among those randomized to the sham procedure.

In the subgroup analysis presented by Dr. Bhatt, the relative control of office SBP, as well as other measures of blood pressure, were similarly and significantly reduced in both Black and non-Black patients. In general, the relative control offered by being randomized initially to renal denervation increased over time in both groups.

For example, the relative reduction in office SBP favoring renal denervation climbed from –12.0 mm Hg at 12 months (P = .0066) to –21.0 at 18 months (P = .0002) and then to –24.9 mm Hg (P < .0001) at 36 months in the Black subgroup. In non-Blacks, the same type of relative reductions were seen at each time point, climbing from –13.5 (P < .0001) to –20.5 (P < .0001) and then to –21.0 (P < .0001).

The comparisons for other measures of BP control, including office diastolic BP, 24-hour SBP, and BP control during morning, day, and night periods were also statistically and similarly improved for those initially randomized to renal denervation rather than a sham procedure among both Blacks and non-Blacks.

Renal denervation safe in Black and non-Black patients

Renal denervation was well tolerated in both Black and non-Black participants with no signal of long-term risks over 36 months in either group. Among Blacks, rates of death at 36 months (3% vs. 11%) and stroke (7% vs. 11%) were lower among those randomized to renal denervation relative to sham patients who never crossed over, but Dr. Bhatt said the numbers are too small to draw any conclusions about outcomes.

While this subgroup analysis, along with the final SYMPLICITY report, supports the efficacy of renal denervation over the long term, these data are also consistent with the recently published analysis of SPYRAL ON-MED . Together, these data have led many experts, including Dr. Bhatt, to conclude that renal denervation is effective and deserves regulatory approval.

“In out-of-control blood pressure, when patients have maxed out on medications and lifestyle, I think renal denervation is efficacious, and it is equally efficacious in Blacks and non-Blacks,” Dr. Bhatt said.

This subgroup analysis is important because of the need for options in treatment-resistant hypertension among Black as well as non-Black patients, pointed out Sripal Bangalore, MBBS, director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

“I am glad that we did not conclude too soon that it does not work in Blacks,” Dr. Bangalore said. If renal denervation is approved, he expects this procedure to be a valuable tool in this racial group.

Dr. Bhatt reported financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical and device companies, including Medtronic, which provided funding for the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. Dr. Bangalore has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic.

WASHINGTON – On the heels the recently published final report from the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 renal denervation trial, a new analysis showed that Black patients, like non-Blacks, had sustained blood pressure control.

Contrary to a signal from earlier results, “there is nothing race specific about renal denervation,” said presenter Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

Black patients are well represented among patients with treatment-resistant hypertension and considered an important subgroup to target, according to Dr. Bhatt, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. This is the reason that they were not only a prespecified subgroup in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, but race was one of two stratification factors at enrollment. At the time of the study design, there was an expectation that Black patients would benefit more than non-Blacks.

This did not prove to be the case during the 6-month controlled phase of the trial. When patients randomized to renal denervation or the sham procedure were stratified by race, the primary endpoint of reduction in office systolic blood pressure (SBP) reached significance in the experimental arm among non-Black patients (–6.63 mm Hg; P = .01), but not among Black patients (–2.25 mm Hg; P = .09).

Blacks comprised 26% of SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial

In the initial controlled analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the lack of benefit in the substantial Black enrollment – representing 26% of the study total – weighed against the ability of the trial to demonstrate a benefit, but Dr. Bhatt pointed out that BP reductions were unexpectedly high in the sham group regardless of race. Patients randomized to the sham group were encouraged to adhere to antihypertensive therapy, and based on response, this was particularly effective in the Black sham subgroup.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, patients with treatment-resistant hypertension were randomized to renal denervation or a sham procedure in a 2:1 ratio. While the controlled phase lasted just 6 months, the follow-up after the study was unblinded has continued out to 3 years. Safety and efficacy were assessed at 12, 24, and 36 months.

Unlike the disappointing results at 6 months, renal denervation has been consistently associated with significantly lower BP over long-term follow-up, even though those randomized to the sham procedure were permitted to cross over. About two-thirds of the sham group did so.

In the recently published final report of SYMPLICITY, the overall median change in office SBP at 3 years regardless of race was –26.4 mm Hg in the group initially randomized to renal denervation versus –5.7 mm Hg (P < .0001) among those randomized to the sham procedure.

In the subgroup analysis presented by Dr. Bhatt, the relative control of office SBP, as well as other measures of blood pressure, were similarly and significantly reduced in both Black and non-Black patients. In general, the relative control offered by being randomized initially to renal denervation increased over time in both groups.

For example, the relative reduction in office SBP favoring renal denervation climbed from –12.0 mm Hg at 12 months (P = .0066) to –21.0 at 18 months (P = .0002) and then to –24.9 mm Hg (P < .0001) at 36 months in the Black subgroup. In non-Blacks, the same type of relative reductions were seen at each time point, climbing from –13.5 (P < .0001) to –20.5 (P < .0001) and then to –21.0 (P < .0001).

The comparisons for other measures of BP control, including office diastolic BP, 24-hour SBP, and BP control during morning, day, and night periods were also statistically and similarly improved for those initially randomized to renal denervation rather than a sham procedure among both Blacks and non-Blacks.

Renal denervation safe in Black and non-Black patients

Renal denervation was well tolerated in both Black and non-Black participants with no signal of long-term risks over 36 months in either group. Among Blacks, rates of death at 36 months (3% vs. 11%) and stroke (7% vs. 11%) were lower among those randomized to renal denervation relative to sham patients who never crossed over, but Dr. Bhatt said the numbers are too small to draw any conclusions about outcomes.

While this subgroup analysis, along with the final SYMPLICITY report, supports the efficacy of renal denervation over the long term, these data are also consistent with the recently published analysis of SPYRAL ON-MED . Together, these data have led many experts, including Dr. Bhatt, to conclude that renal denervation is effective and deserves regulatory approval.

“In out-of-control blood pressure, when patients have maxed out on medications and lifestyle, I think renal denervation is efficacious, and it is equally efficacious in Blacks and non-Blacks,” Dr. Bhatt said.

This subgroup analysis is important because of the need for options in treatment-resistant hypertension among Black as well as non-Black patients, pointed out Sripal Bangalore, MBBS, director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

“I am glad that we did not conclude too soon that it does not work in Blacks,” Dr. Bangalore said. If renal denervation is approved, he expects this procedure to be a valuable tool in this racial group.

Dr. Bhatt reported financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical and device companies, including Medtronic, which provided funding for the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. Dr. Bangalore has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic.

AT CRT 2023

Inequity, Bias, Racism, and Physician Burnout: Staying Connected to Purpose and Identity as an Antidote

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

Bridging the Digital Divide in Teledermatology Usage: A Retrospective Review of Patient Visits

Teledermatology is an effective patient care model for the delivery of high-quality dermatologic care.1 Teledermatology can occur using synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid models of care. In asynchronous visits (AVs), patients or health professionals submit photographs and information for dermatologists to review and provide treatment recommendations. With synchronous visits (SVs), patients have a visit with a dermatology health professional in real time via live video conferencing software. Hybrid models incorporate asynchronous strategies for patient intake forms and skin photograph submissions as well as synchronous methods for live video consultation in a single visit.1 However, remarkable inequities in internet access limit telemedicine usage among medically marginalized patient populations, including racialized, elderly, and low socioeconomic status groups.2

Synchronous visits, a relatively newer teledermatology format, allow for communication with dermatology professionals from the convenience of a patient’s selected location. The live interaction of SVs allows dermatology professionals to answer questions, provide treatment recommendations, and build therapeutic relationships with patients. Concerns for dermatologist reimbursement, malpractice/liability, and technological challenges stalled large-scale uptake of teledermatology platforms.3 The COVID-19 pandemic led to a drastic increase in teledermatology usage of approximately 587.2%, largely due to public safety measures and Medicaid reimbursement parity between SV and in-office visits (IVs).3,4

With the implementation of SVs as a patient care model, we investigated the demographics of patients who utilized SVs, AVs, or IVs, and we propose strategies to promote equity in dermatologic care access.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board (STUDY20110043). We performed a retrospective electronic medical record review of deidentified data from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a tertiary care center in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, with an established asynchronous teledermatology program. Hybrid SVs were integrated into the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center patient care visit options in March 2020. Patients were instructed to upload photographs of their skin conditions prior to SV appointments. The study included visits occurring between July and December 2020. Visit types included SVs, AVs, and IVs.

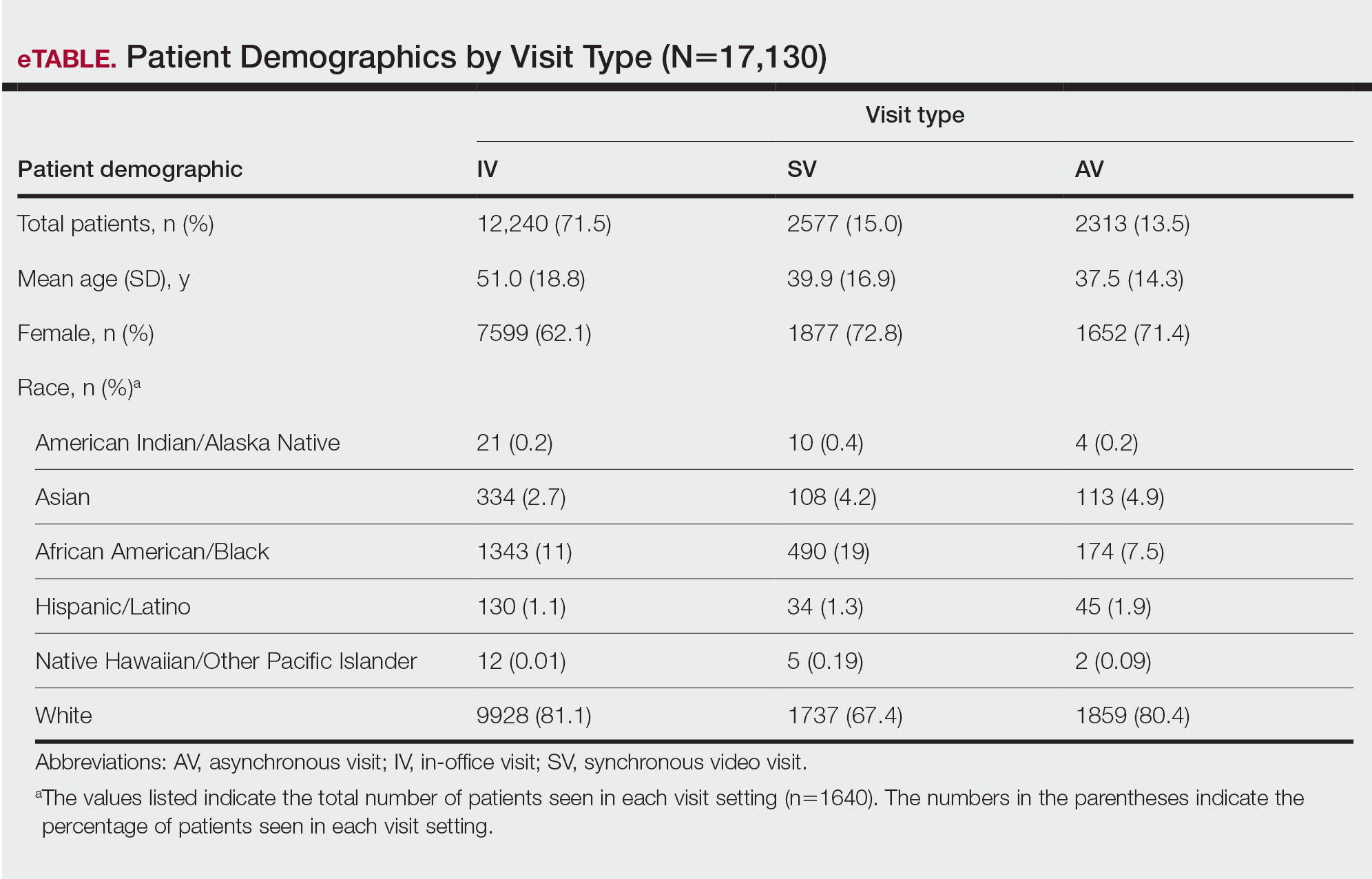

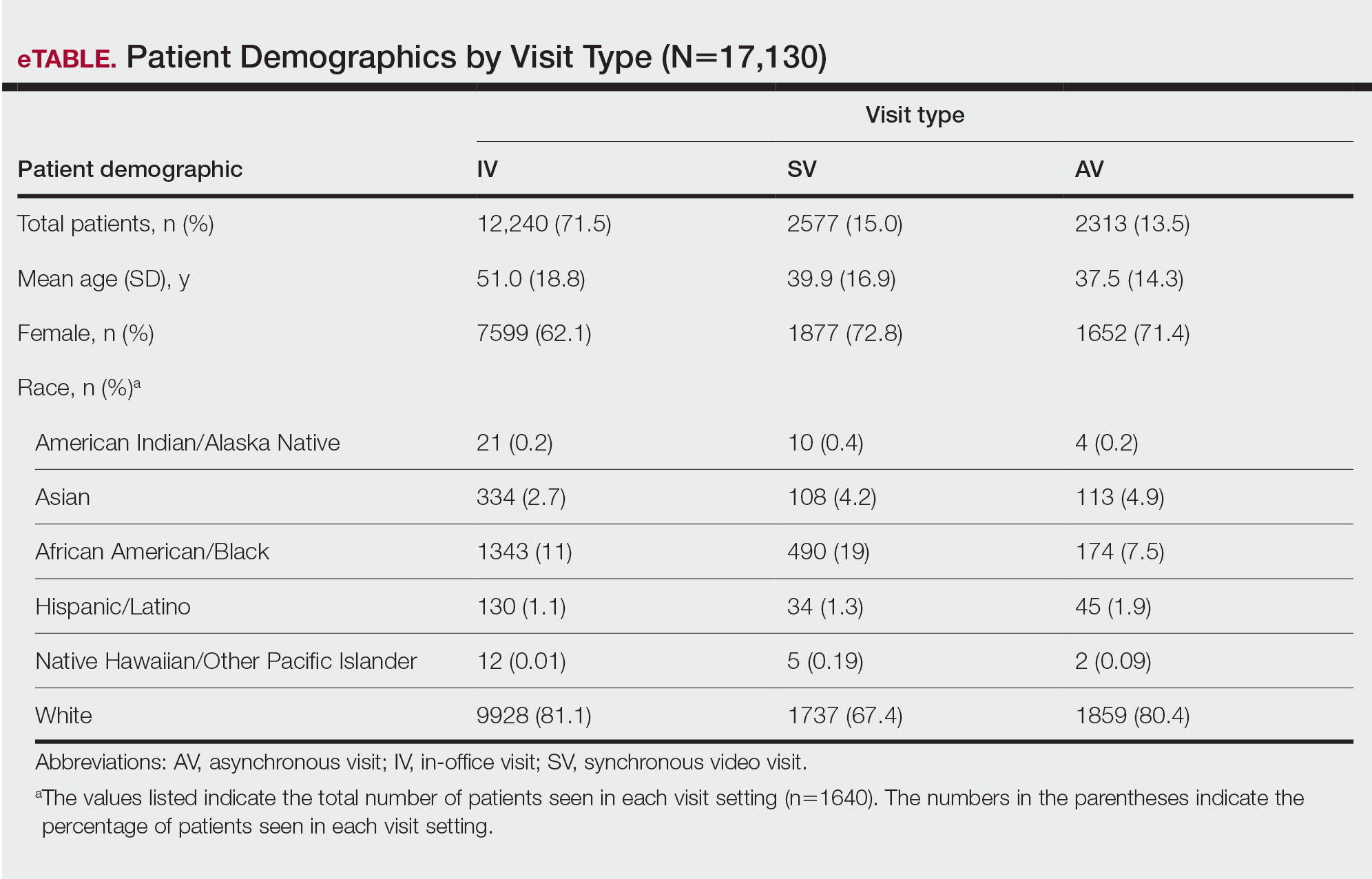

We analyzed the initial dermatology visits of 17,130 patients aged 17.5 years and older. Recorded data included diagnosis, age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance type for each visit type. Patients without a reported race (990 patients) or ethnicity (1712 patients) were excluded from analysis of race/ethnicity data. Patient zip codes were compared with the zip codes of Allegheny County municipalities as reported by the Allegheny County Elections Division.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated; frequency with percentage was used to report categorical variables, and the mean (SD) was used for normally distributed continuous variables. Univariate analysis was performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare age among visit types. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24 (IBM Corp) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

In our study population, 81.2% (13,916) of patients were residents of Allegheny County, where 51.6% of residents are female and 81.4% are older than 18 years according to data from 2020.5 The racial and ethnic demographics of Allegheny County were 13.4% African American/Black, 0.2% American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.2% Asian, 2.3% Hispanic/Latino, and 79.6% White. The percentage of residents who identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander was reported to be greater than 0% but less than 0.5%.5

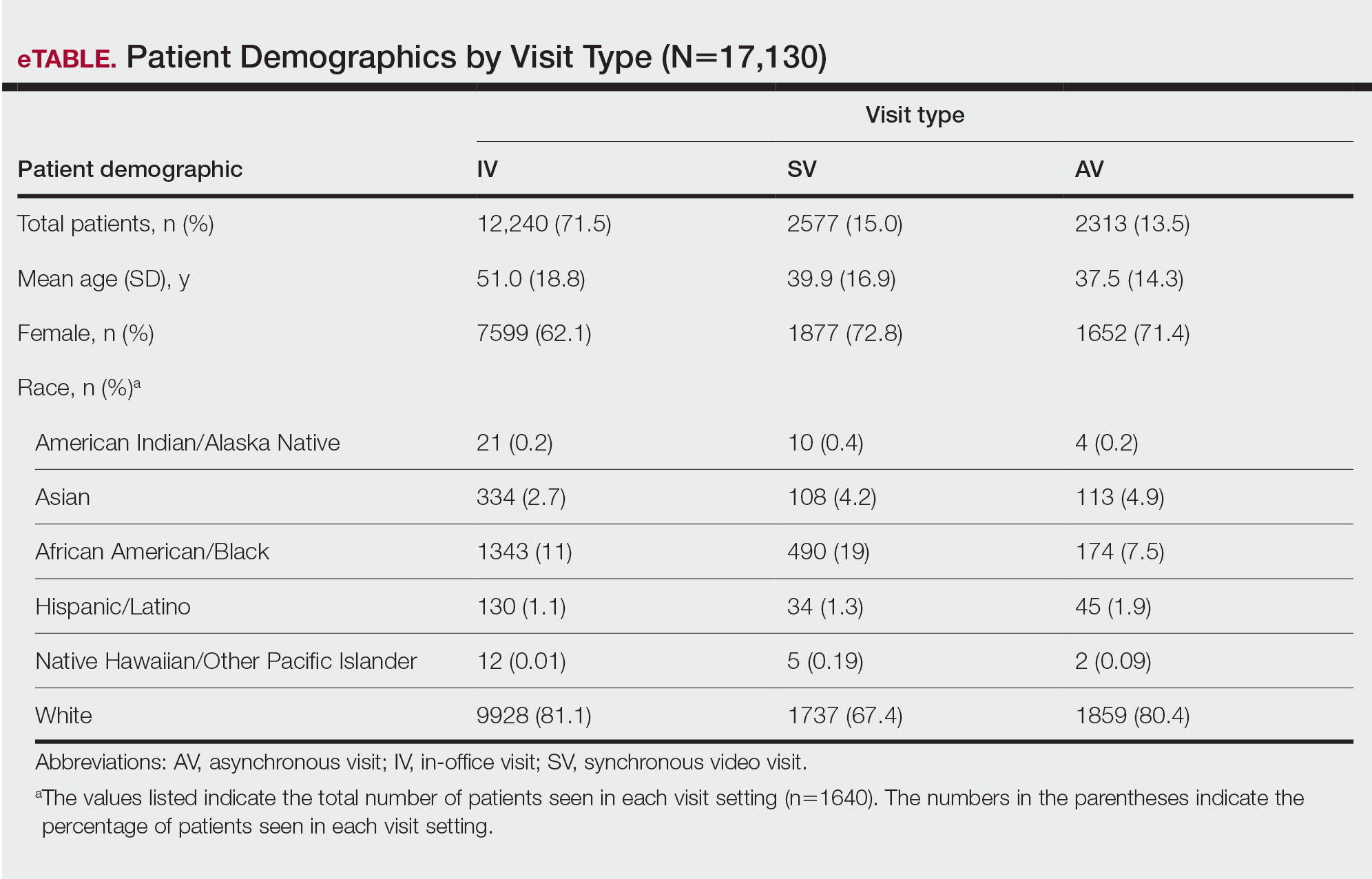

In our analysis, IVs were the most utilized visit type, accounting for 71.5% (12,240) of visits, followed by 15.0% (2577) for SVs and 13.5% (2313) for AVs. The mean age (SD) of IV patients was 51.0 (18.8) years compared with 39.9 (16.9) years for SV patients and 37.5 (14.3) years for AV patients (eTable). The majority of patients for all visits were female: 62.1% (7599) for IVs, 71.4% (1652) for AVs, and 72.8% (1877) for SVs. The largest racial or ethnic group for all visit types included White patients (83.8% [13,524] of all patients), followed by Black (12.4% [2007]), Hispanic/Latino (1.4% [209]), Asian (3.4% [555]), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.2% [35]), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients (0.1% [19]).

Asian patients, who comprised 4.2% of Allegheny County residents,5 accounted for 2.7% (334) of IVs, 4.9% (113) of AVs, and 4.2% (108) of SVs. Black patients, who were reported as 13.4% of the Allegheny County population,5 were more likely to utilize SVs (19% [490])compared with AVs (7.5% [174]) and IVs (11% [1343]). Hispanic/Latino patients had a disproportionally lower utilization of dermatologic care in all settings, comprising 1.4% (209) of all patients in our study compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 White patients, who comprised 79.6% of Allegheny County residents, accounted for 81.1% (9928) of IVs, 67.4% (1737) of SVs, and 80.4% (1859) of AVs. There was no significant difference in the percentage of American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients among visit types.

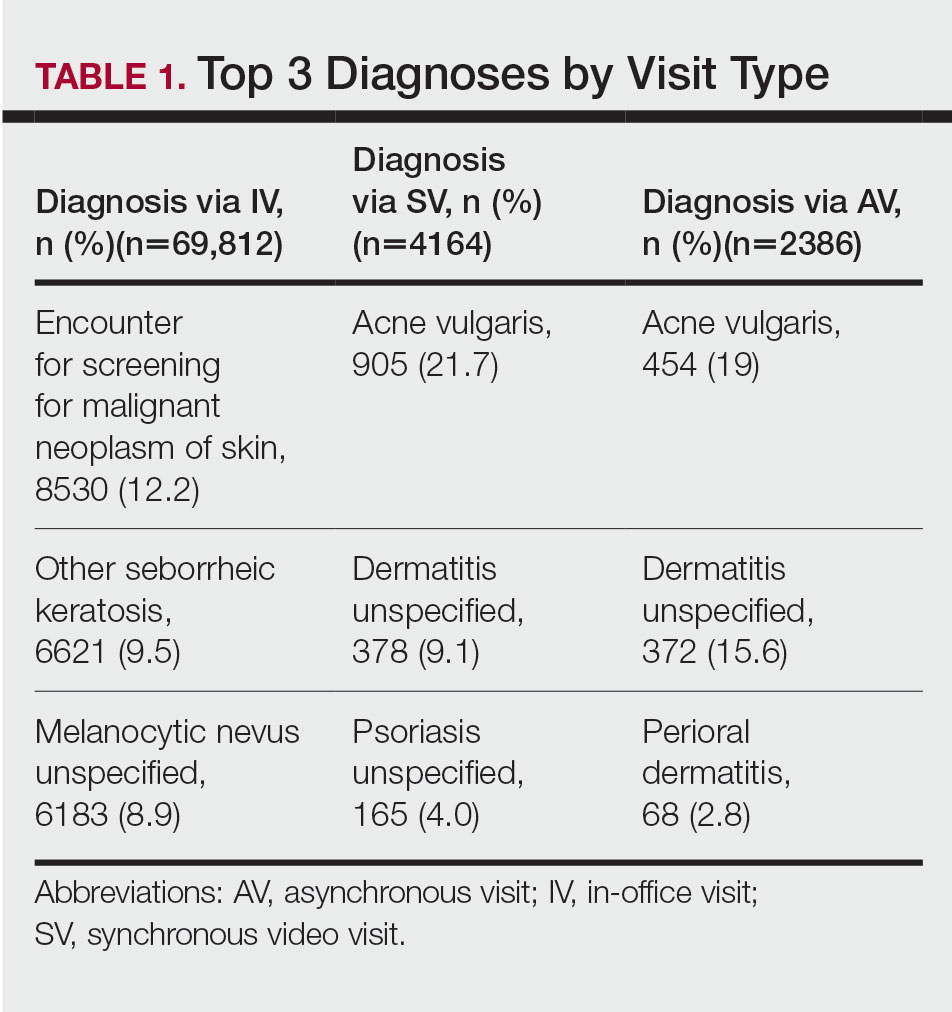

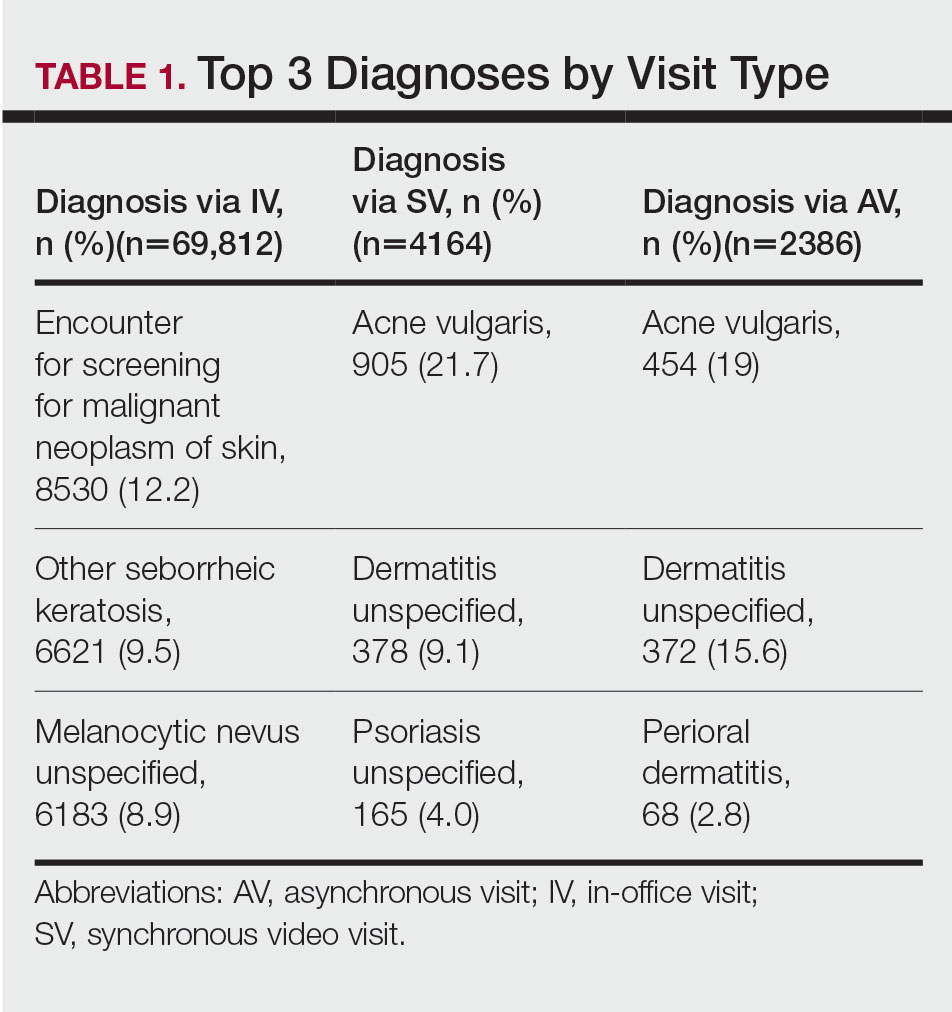

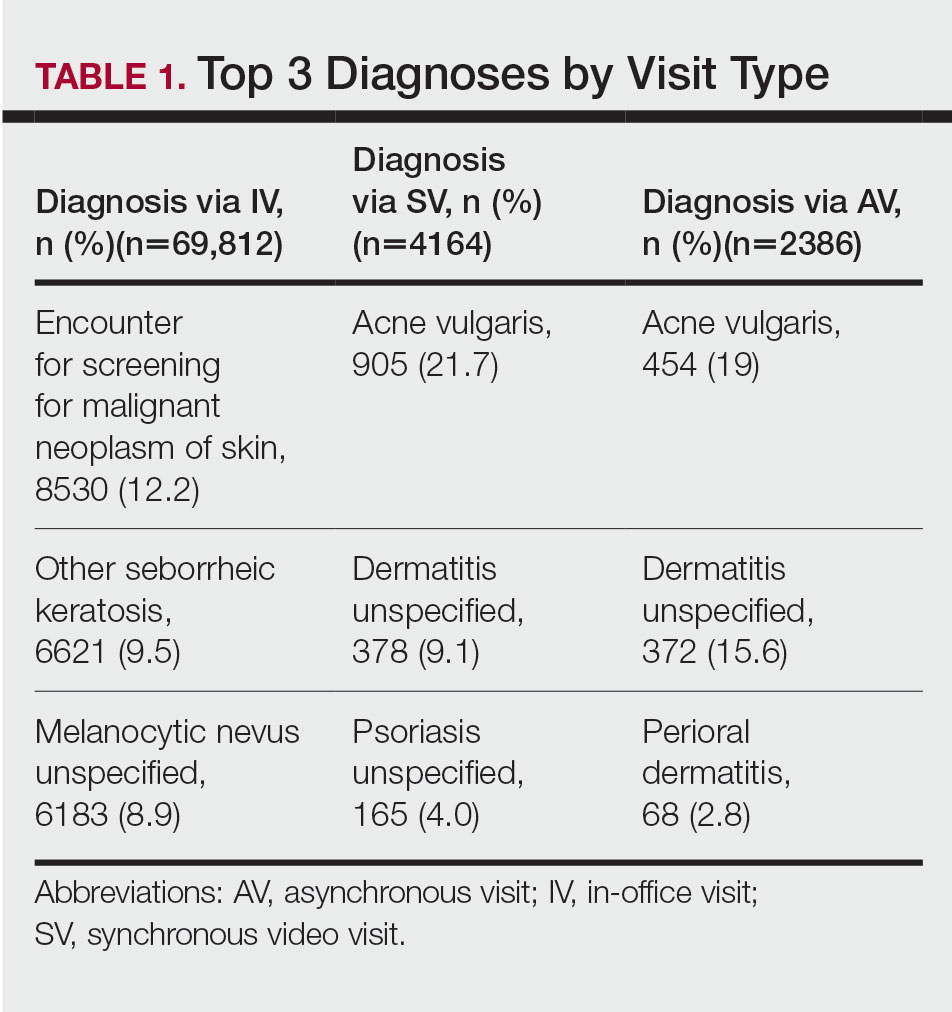

The 3 most common diagnoses for IVs were skin cancer screening, seborrheic keratosis, and melanocytic nevus (Table 1). Skin cancer screening was the most common diagnosis, accounting for 12.2% (8530) of 69,812 IVs. The 3 most common diagnoses for SVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and psoriasis. The 3 most common diagnoses for AVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis.

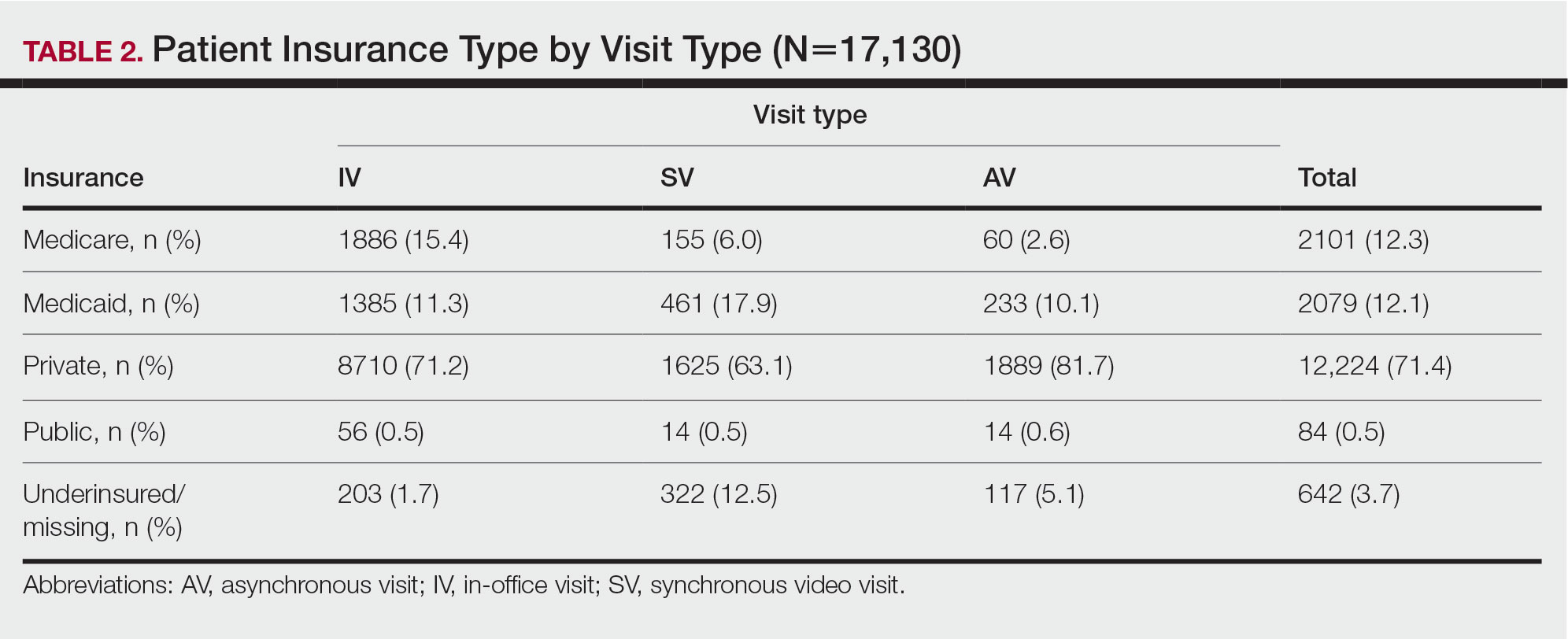

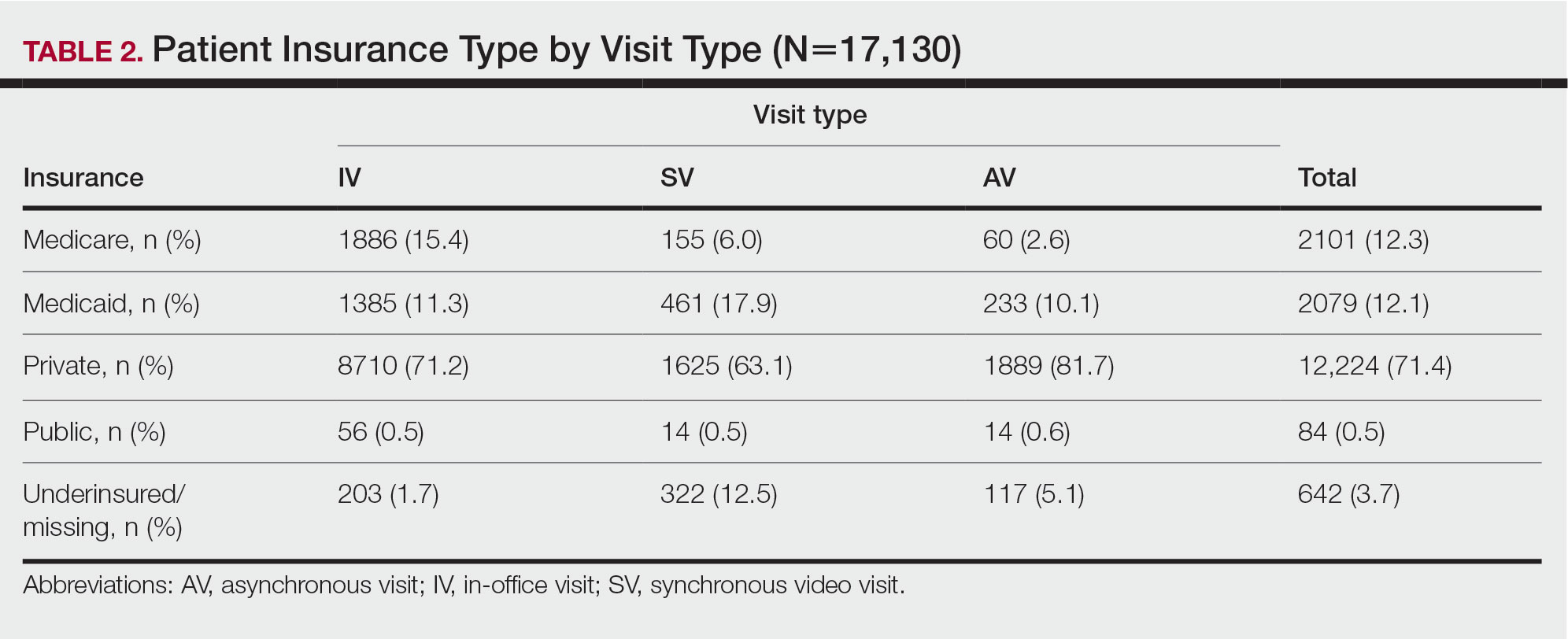

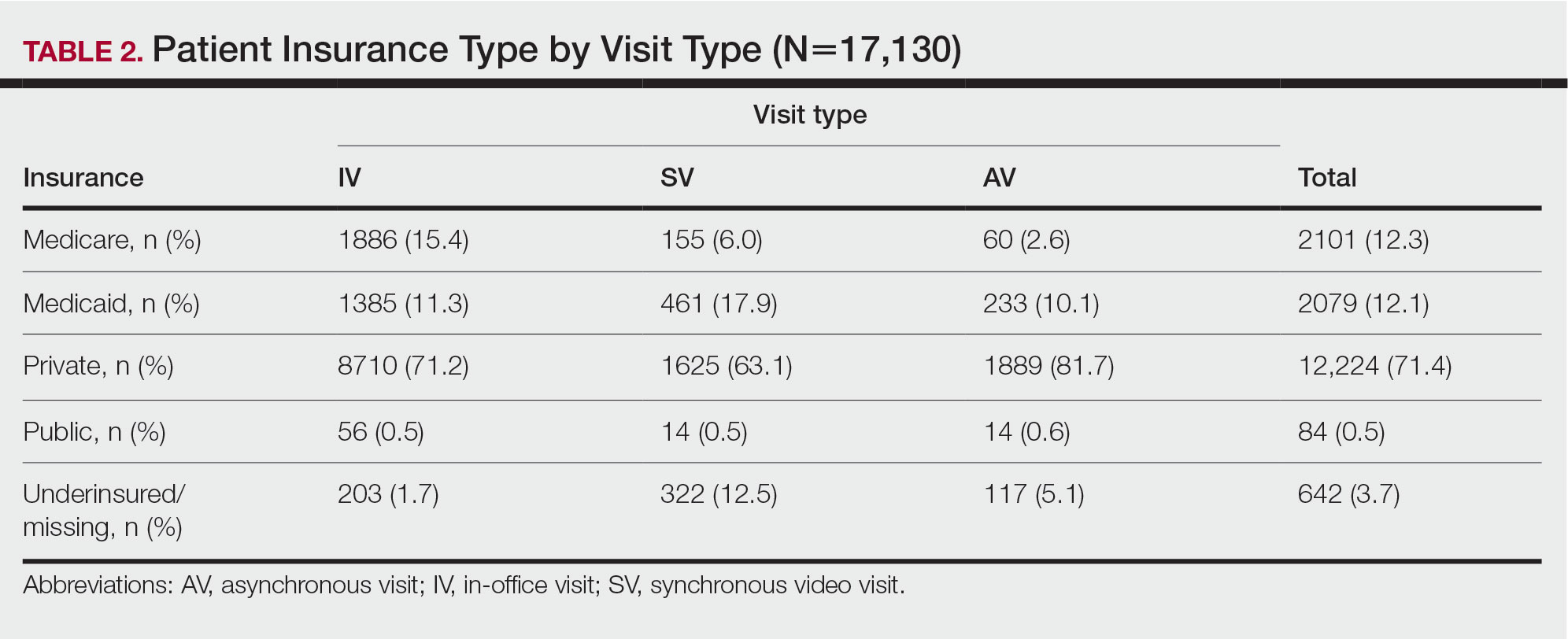

Private insurance was the most common insurance type among all patients (71.4% [12,224])(Table 2). A higher percentage of patients with Medicaid insurance (17.9% [461]) utilized SVs compared with AVs (10.1% [233]) and IVs (11.3% 1385]). Similarly, a higher percentage of patients with no insurance or no insurance listed were seen via SVs (12.5% [322]) compared with AVs (5.1% [117]) and IVs (1.7% [203]). Patients with Medicare insurance used IVs (15.4% [1886]) more than SVs (6.0% [155]) or AVs (2.6% [60]). There was no significant difference among visit type usage for patients with public insurance.

Comment

Teledermatology Benefits—In this retrospective review of medical records of patients who obtained dermatologic care after the implementation of SVs at our institution, we found a proportionally higher use of SVs among Black patients, patients with Medicaid, and patients who are underinsured. Benefits of teledermatology include decreases in patient transportation and associated costs, time away from work or home, and need for childcare.6 The SV format provides the additional advantage of direct live interaction and the development of a patient-physician or patient–physician assistant relationship. Although the prerequisite technology, internet, and broadband connectivity preclude use of teledermatology for many vulnerable patients,2 its convenience ultimately may reduce inequities in access.

Disparities in Dermatologic Care—Hispanic ethnicity and male sex are among described patient demographics associated with decreased rates of outpatient dermatologic care.7 We reported disparities in dermatologic care utilization across all visit types among Hispanic patients and males. Patients identifying as Hispanic/Latino composed only 1.4% (n=209) of our study population compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 During our study period, most patients seen were female, accounting for 62.1% to 72.8% of visits, compared with 51.6% of Allegheny County residents.5 These disparities in dermatologic care use may have implications for increased skin-associated morbidity and provide impetus for dermatologists to increase engagement with these patient groups.

Characteristics of Patients Using Teledermatology—Patients using SVs and AVs were significantly younger (mean age [SD], 39.9 [16.9] years and 37.5 [14.3] years, respectively) compared with those using IVs (51.0 [18.8] years). This finding reflects known digital knowledge barriers among older patients.8,9 The synchronous communication format of SVs simulates the traditional visit style of IVs, which may be preferable for some patients. Continued patient education and advocacy for broadband access may increase teledermatology use among older patients and patients with limited technology resources.8

Teledermatology visits were used most frequently for acne and dermatitis, while IVs were used for skin cancer screenings and examination of concerning lesions. This usage pattern is consistent with a previously described consensus among dermatologists on the conditions most amenable to teledermatology evaluation.3

Medicaid reimbursement parity for SVs is in effect nationally until the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration in the United States.10 As of February 2023, the public health emergency declaration has been renewed 12 times since January 2020, with the most recent renewal on January 11, 2023.11 As of January 2023, 21 states have enacted legislation providing permanent reimbursement parity for SV services. Six additional states have some payment parity in place, each with its own qualifying criteria, and 23 states have no payment parity.12 Only 25 Medicaid programs currently provide reimbursement for AV services.13

Study Limitations—Our study was limited by lack of data on patients who are multiracial and those who identify as nonbinary and transgender. Because of the low numbers of Hispanic patients associated with each race category and a high number of patients who did not report an ethnicity or race, race and ethnicity data were analyzed separately. For SVs, patients were instructed to upload photographs prior to their visit; however, the percentage of patients who uploaded photographs was not analyzed.

Conclusion

Expansion of teledermatology services, including SVs and AVs, patient outreach and education, advocacy for broadband access, and Medicaid payment parity, may improve dermatologic care access for medically marginalized groups. Teledermatology has the potential to serve as an effective health care option for patients who are racially minoritized, older, and underinsured. To further assess the effectiveness of teledermatology, we plan to analyze the number of SVs and AVs that were referred to IVs. Future studies also will investigate the impact of implementing patient education and patient-reported outcomes of teledermatology visits.

- Lee JJ, English JC. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.