User login

‘We Will Rock You’ Into Real-time Diabetes Control

, reveals a series of experiments.

The research was published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

After developing a cell line in which music-sensitive calcium channels triggered the release of insulin-containing vesicles, the researchers conducted a series of studies identifying the optimal frequency, pitch, and volume of sounds for triggering release.

After settling on low-bass heavy popular music, they tested their system on mice with type 1 diabetes that had the insulin-releasing cells implanted in their abdomen. Applying the music directly at 60 dB led to near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood within 15 minutes.

“With only 4 hours required for a full refill, [the system] can provide several therapeutic doses a day,” says Martin Fussenegger, PhD, professor of biotechnology and bioengineering, Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering, ETH Zurich, Basel, Switzerland, and colleagues.

“This would match the typical needs of people with type 2 diabetes consuming three meals a day, and for whom administration of prandial insulin is an established treatment option, as they do not have capability for early postprandial insulin secretion from preformed insulin.”

As the system requires nothing more than portable battery-powered commercially available loudspeakers, the multiple daily dosing of biopharmaceuticals becomes “straightforward in the absence of medical infrastructure or staff, simply by having the patient listen to the prescribed music.”

It therefore “could be an interesting option for cell-based therapies, especially where the need for frequent dosing raises compliance issues.”

It is a “very exciting piece of work, no doubt,” said Anandwardhan A. Hardikar, PhD, group leader, Diabetes and Islet Biology Group, Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith NSW, Australia.

He pointed out that the concept of using music to drive gene expression “is something we’ve known for the last 20 years,” but bringing the different strands of research together to generate cells that can be implanted into mice is “an amazing idea.”

Dr. Hardikar, who was not involved in the study, said, however, the publication of the study as a correspondence “does not allow for a lot of the detail that I would have expected as an academic,” and consequently some questions remain.

The most important is whether the music itself is required to trigger the insulin release, as opposed simply to sounds in general.

Is Music or Sound the “Trigger?”

Music is “frequency, it’s the amplitude of the waveform, and it’s the duration for which those waveforms are present,” he noted, but the same profile can be achieved by cutting up and editing the melody so it becomes a jumble of sounds.

For Dr. Hardikar, the “best control” for the study would be to have no music as well as the edited song, with “bits of pieces” played randomly so “it sounds like it’s the same frequency and amplitude.”

Then it would be clear whether the effect is owing to the “noise, or we have to appreciate the melody.”

The other outstanding question is whether the results “can directly translate to larger animals,” such as humans, Dr. Hardikar said.

The authors point out that when translated into mechanical vibrations in the middle ear, the acoustic waves of music activate mechanosensitive ion channels, a form of trigger that is seen across the animal kingdom.

They go on to highlight that while gene switches have been developed for use in next-generation cell-based therapies for a range of conditions, small-molecular trigger compounds face a number of challenges and may cause adverse effects.

With “traceless triggers” such as light, ultrasound, magnetic fields, radio waves, electricity, and heat also facing issues, there is a “need for new switching modalities.”

The researchers therefore developed a music-inducible cellular control (MUSIC) system, which leverages the known intracellular calcium surge in response to music, via calcium-permeable mechanosensitive channels, to drive the release of biopharmaceuticals from vesicles.

They then generated MUSIC-controlled insulin-releasing cell lines, finding that, using a customized box containing off-the-shelf loudspeakers, they could induce channel activation and insulin release with 60 dB at 50 Hz, which is “within the safe range for the human ear.”

Further experiments revealed that insulin release was greatest at 50-100 Hz, and higher than that seen with potassium chloride, the “gold-standard” depolarization control for calcium channels.

The researchers then showed that with optimal stimulation at 50 Hz and 60 dB, channel activation and subsequent insulin release required at least 3 seconds of continuous music, “which might protect the cellular device from inadvertent activation during everyday activities.”

Next, they examined the impact of different musical genres on insulin release, finding that low-bass heavy popular music and movie soundtracks induced maximum release, while the responses were more diverse to classical and guitar-based music.

Specifically, “We Will Rock You,” by the British rock band Queen, induced the release of 70% of available insulin within 5 minutes and 100% within 15 minutes. This, the team notes, is “similar to the dynamics of glucose-triggered insulin release by human pancreatic islets.”

Exposing the cells to a second music session at different intervals revealed that full insulin refill was achieved within 4 hours, which “would be appropriate to attenuate glycemic excursions associated with typical dietary habits.”

Finally, the researchers tested the system in vivo, constructing a box with two off-the-shelf loudspeakers that focuses acoustic waves, via deflectors, onto the abdomens of mice with type 1 diabetes.

Exposing the mice, which had been implanted with microencapsulated MUSIC cells in the peritoneum, to low-bass acoustic waves at 60 dB (50 m/s2) for 15 minutes allowed them to achieve near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood and restored normoglycemia.

Moreover, “Queen’s song ‘We Will Rock You’ generated sufficient insulin to rapidly attenuate postprandial glycemic excursions during glucose tolerance tests,” the team says.

In contrast, animals without implants, or those that had implants but did not have music immersion, remained severely hyperglycemic, they add.

They also note that the effect was seen only when the sound waves “directly impinge on the skin just above the implantation site” for at least 15 minutes, with no increase in insulin release observed with commercially available headphones or ear plugs, such as Apple AirPods, or with loud environmental noises.

Consequently, “therapeutic MUSIC sessions would still be compatible with listening to other types of music or listening to all types of music via headphones,” the researchers write, and are “compatible with standard drug administration schemes.”

The study was supported by a European Research Council advanced grant and in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering. One author acknowledges the support of the Chinese Scholarship Council.

No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, reveals a series of experiments.

The research was published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

After developing a cell line in which music-sensitive calcium channels triggered the release of insulin-containing vesicles, the researchers conducted a series of studies identifying the optimal frequency, pitch, and volume of sounds for triggering release.

After settling on low-bass heavy popular music, they tested their system on mice with type 1 diabetes that had the insulin-releasing cells implanted in their abdomen. Applying the music directly at 60 dB led to near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood within 15 minutes.

“With only 4 hours required for a full refill, [the system] can provide several therapeutic doses a day,” says Martin Fussenegger, PhD, professor of biotechnology and bioengineering, Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering, ETH Zurich, Basel, Switzerland, and colleagues.

“This would match the typical needs of people with type 2 diabetes consuming three meals a day, and for whom administration of prandial insulin is an established treatment option, as they do not have capability for early postprandial insulin secretion from preformed insulin.”

As the system requires nothing more than portable battery-powered commercially available loudspeakers, the multiple daily dosing of biopharmaceuticals becomes “straightforward in the absence of medical infrastructure or staff, simply by having the patient listen to the prescribed music.”

It therefore “could be an interesting option for cell-based therapies, especially where the need for frequent dosing raises compliance issues.”

It is a “very exciting piece of work, no doubt,” said Anandwardhan A. Hardikar, PhD, group leader, Diabetes and Islet Biology Group, Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith NSW, Australia.

He pointed out that the concept of using music to drive gene expression “is something we’ve known for the last 20 years,” but bringing the different strands of research together to generate cells that can be implanted into mice is “an amazing idea.”

Dr. Hardikar, who was not involved in the study, said, however, the publication of the study as a correspondence “does not allow for a lot of the detail that I would have expected as an academic,” and consequently some questions remain.

The most important is whether the music itself is required to trigger the insulin release, as opposed simply to sounds in general.

Is Music or Sound the “Trigger?”

Music is “frequency, it’s the amplitude of the waveform, and it’s the duration for which those waveforms are present,” he noted, but the same profile can be achieved by cutting up and editing the melody so it becomes a jumble of sounds.

For Dr. Hardikar, the “best control” for the study would be to have no music as well as the edited song, with “bits of pieces” played randomly so “it sounds like it’s the same frequency and amplitude.”

Then it would be clear whether the effect is owing to the “noise, or we have to appreciate the melody.”

The other outstanding question is whether the results “can directly translate to larger animals,” such as humans, Dr. Hardikar said.

The authors point out that when translated into mechanical vibrations in the middle ear, the acoustic waves of music activate mechanosensitive ion channels, a form of trigger that is seen across the animal kingdom.

They go on to highlight that while gene switches have been developed for use in next-generation cell-based therapies for a range of conditions, small-molecular trigger compounds face a number of challenges and may cause adverse effects.

With “traceless triggers” such as light, ultrasound, magnetic fields, radio waves, electricity, and heat also facing issues, there is a “need for new switching modalities.”

The researchers therefore developed a music-inducible cellular control (MUSIC) system, which leverages the known intracellular calcium surge in response to music, via calcium-permeable mechanosensitive channels, to drive the release of biopharmaceuticals from vesicles.

They then generated MUSIC-controlled insulin-releasing cell lines, finding that, using a customized box containing off-the-shelf loudspeakers, they could induce channel activation and insulin release with 60 dB at 50 Hz, which is “within the safe range for the human ear.”

Further experiments revealed that insulin release was greatest at 50-100 Hz, and higher than that seen with potassium chloride, the “gold-standard” depolarization control for calcium channels.

The researchers then showed that with optimal stimulation at 50 Hz and 60 dB, channel activation and subsequent insulin release required at least 3 seconds of continuous music, “which might protect the cellular device from inadvertent activation during everyday activities.”

Next, they examined the impact of different musical genres on insulin release, finding that low-bass heavy popular music and movie soundtracks induced maximum release, while the responses were more diverse to classical and guitar-based music.

Specifically, “We Will Rock You,” by the British rock band Queen, induced the release of 70% of available insulin within 5 minutes and 100% within 15 minutes. This, the team notes, is “similar to the dynamics of glucose-triggered insulin release by human pancreatic islets.”

Exposing the cells to a second music session at different intervals revealed that full insulin refill was achieved within 4 hours, which “would be appropriate to attenuate glycemic excursions associated with typical dietary habits.”

Finally, the researchers tested the system in vivo, constructing a box with two off-the-shelf loudspeakers that focuses acoustic waves, via deflectors, onto the abdomens of mice with type 1 diabetes.

Exposing the mice, which had been implanted with microencapsulated MUSIC cells in the peritoneum, to low-bass acoustic waves at 60 dB (50 m/s2) for 15 minutes allowed them to achieve near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood and restored normoglycemia.

Moreover, “Queen’s song ‘We Will Rock You’ generated sufficient insulin to rapidly attenuate postprandial glycemic excursions during glucose tolerance tests,” the team says.

In contrast, animals without implants, or those that had implants but did not have music immersion, remained severely hyperglycemic, they add.

They also note that the effect was seen only when the sound waves “directly impinge on the skin just above the implantation site” for at least 15 minutes, with no increase in insulin release observed with commercially available headphones or ear plugs, such as Apple AirPods, or with loud environmental noises.

Consequently, “therapeutic MUSIC sessions would still be compatible with listening to other types of music or listening to all types of music via headphones,” the researchers write, and are “compatible with standard drug administration schemes.”

The study was supported by a European Research Council advanced grant and in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering. One author acknowledges the support of the Chinese Scholarship Council.

No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, reveals a series of experiments.

The research was published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

After developing a cell line in which music-sensitive calcium channels triggered the release of insulin-containing vesicles, the researchers conducted a series of studies identifying the optimal frequency, pitch, and volume of sounds for triggering release.

After settling on low-bass heavy popular music, they tested their system on mice with type 1 diabetes that had the insulin-releasing cells implanted in their abdomen. Applying the music directly at 60 dB led to near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood within 15 minutes.

“With only 4 hours required for a full refill, [the system] can provide several therapeutic doses a day,” says Martin Fussenegger, PhD, professor of biotechnology and bioengineering, Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering, ETH Zurich, Basel, Switzerland, and colleagues.

“This would match the typical needs of people with type 2 diabetes consuming three meals a day, and for whom administration of prandial insulin is an established treatment option, as they do not have capability for early postprandial insulin secretion from preformed insulin.”

As the system requires nothing more than portable battery-powered commercially available loudspeakers, the multiple daily dosing of biopharmaceuticals becomes “straightforward in the absence of medical infrastructure or staff, simply by having the patient listen to the prescribed music.”

It therefore “could be an interesting option for cell-based therapies, especially where the need for frequent dosing raises compliance issues.”

It is a “very exciting piece of work, no doubt,” said Anandwardhan A. Hardikar, PhD, group leader, Diabetes and Islet Biology Group, Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith NSW, Australia.

He pointed out that the concept of using music to drive gene expression “is something we’ve known for the last 20 years,” but bringing the different strands of research together to generate cells that can be implanted into mice is “an amazing idea.”

Dr. Hardikar, who was not involved in the study, said, however, the publication of the study as a correspondence “does not allow for a lot of the detail that I would have expected as an academic,” and consequently some questions remain.

The most important is whether the music itself is required to trigger the insulin release, as opposed simply to sounds in general.

Is Music or Sound the “Trigger?”

Music is “frequency, it’s the amplitude of the waveform, and it’s the duration for which those waveforms are present,” he noted, but the same profile can be achieved by cutting up and editing the melody so it becomes a jumble of sounds.

For Dr. Hardikar, the “best control” for the study would be to have no music as well as the edited song, with “bits of pieces” played randomly so “it sounds like it’s the same frequency and amplitude.”

Then it would be clear whether the effect is owing to the “noise, or we have to appreciate the melody.”

The other outstanding question is whether the results “can directly translate to larger animals,” such as humans, Dr. Hardikar said.

The authors point out that when translated into mechanical vibrations in the middle ear, the acoustic waves of music activate mechanosensitive ion channels, a form of trigger that is seen across the animal kingdom.

They go on to highlight that while gene switches have been developed for use in next-generation cell-based therapies for a range of conditions, small-molecular trigger compounds face a number of challenges and may cause adverse effects.

With “traceless triggers” such as light, ultrasound, magnetic fields, radio waves, electricity, and heat also facing issues, there is a “need for new switching modalities.”

The researchers therefore developed a music-inducible cellular control (MUSIC) system, which leverages the known intracellular calcium surge in response to music, via calcium-permeable mechanosensitive channels, to drive the release of biopharmaceuticals from vesicles.

They then generated MUSIC-controlled insulin-releasing cell lines, finding that, using a customized box containing off-the-shelf loudspeakers, they could induce channel activation and insulin release with 60 dB at 50 Hz, which is “within the safe range for the human ear.”

Further experiments revealed that insulin release was greatest at 50-100 Hz, and higher than that seen with potassium chloride, the “gold-standard” depolarization control for calcium channels.

The researchers then showed that with optimal stimulation at 50 Hz and 60 dB, channel activation and subsequent insulin release required at least 3 seconds of continuous music, “which might protect the cellular device from inadvertent activation during everyday activities.”

Next, they examined the impact of different musical genres on insulin release, finding that low-bass heavy popular music and movie soundtracks induced maximum release, while the responses were more diverse to classical and guitar-based music.

Specifically, “We Will Rock You,” by the British rock band Queen, induced the release of 70% of available insulin within 5 minutes and 100% within 15 minutes. This, the team notes, is “similar to the dynamics of glucose-triggered insulin release by human pancreatic islets.”

Exposing the cells to a second music session at different intervals revealed that full insulin refill was achieved within 4 hours, which “would be appropriate to attenuate glycemic excursions associated with typical dietary habits.”

Finally, the researchers tested the system in vivo, constructing a box with two off-the-shelf loudspeakers that focuses acoustic waves, via deflectors, onto the abdomens of mice with type 1 diabetes.

Exposing the mice, which had been implanted with microencapsulated MUSIC cells in the peritoneum, to low-bass acoustic waves at 60 dB (50 m/s2) for 15 minutes allowed them to achieve near wild-type levels of insulin in the blood and restored normoglycemia.

Moreover, “Queen’s song ‘We Will Rock You’ generated sufficient insulin to rapidly attenuate postprandial glycemic excursions during glucose tolerance tests,” the team says.

In contrast, animals without implants, or those that had implants but did not have music immersion, remained severely hyperglycemic, they add.

They also note that the effect was seen only when the sound waves “directly impinge on the skin just above the implantation site” for at least 15 minutes, with no increase in insulin release observed with commercially available headphones or ear plugs, such as Apple AirPods, or with loud environmental noises.

Consequently, “therapeutic MUSIC sessions would still be compatible with listening to other types of music or listening to all types of music via headphones,” the researchers write, and are “compatible with standard drug administration schemes.”

The study was supported by a European Research Council advanced grant and in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering. One author acknowledges the support of the Chinese Scholarship Council.

No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

Erectile Dysfunction Rx: Give It a Shot

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr Rachel Rubin. I am a urologist with fellowship training in sexual medicine. Today I’m going to explain why I may recommend that your patients put a needle directly into their penises for help with erectile dysfunction (ED).

I know that sounds crazy, but in a recent video when I talked about erection hardness, I acknowledged that it may not be easy to talk with patients about their penises, but it’s important.

ED can be a marker for cardiovascular disease, with 50% of our 50-year-old patients having ED. As physicians, we must do a better job of talking to our patients about ED and letting them know that it’s a marker for overall health.

How do we treat ED? Primary care doctors can do a great deal for patients with ED, and there are other things that urologists can do when you run out of options in your own toolbox.

What’s important for a healthy erection? You need three things: healthy muscle, healthy nerves, and healthy arteries. If anything goes wrong with muscles, nerves, or arteries, this is what leads to ED. Think through the algorithm of your patient’s medical history: Do they have diabetes, which can affect their nerves? Do they have high blood pressure, which can affect their arteries? Do they have problems with testosterone, which can affect the smooth muscles of the penis? Understanding your patient’s history can be really helpful when you figure out what is the best treatment strategy for your patient.

For the penis to work, those smooth muscles have to relax; therefore, your brain has to be relaxed, along with your pelvic floor muscles. The smooth muscle of the penis has to be relaxed so it can fill with blood, increase in girth and size, and hold that erection in place.

To treat ED, we have a biopsychosocial toolbox. Biology refers to the muscles, arteries, and nerves. The psychosocial component is stress: If your brain is stressed, you have a lot of adrenaline around that can tighten those smooth muscles and cause you to lose an erection.

So, what are these treatments? I’ll start with lifestyle. A healthy heart means a healthy penis, so, all of the things you already recommend for lifestyle changes can really help with ED. Sleep is important. Does your patient need a sleep study? Do they have sleep apnea? Are they exercising? Recent data show that exercise may be just as effective, if not more effective, than Viagra. How about a good diet? The Mediterranean diet seems to be the most helpful. So, encourage your patients to make dietary, exercise, sleep, and other lifestyle changes if they want to improve erectile function.

What about sex education? Most physicians didn’t get great education about sex in medical school, but it’s very important to our patients who likewise have had inadequate sex education. Ask questions, talk to them, explain what is normal.

I can’t stress enough how important mental health is to a great sex life. Everyone would benefit from sex therapy and becoming better at sex. We need to get better at communicating and educating patients and their partners to maximize their quality of life. If you need to refer to a specialist, we recommend going to psychologytoday.com or aasect.org to find a local sex therapist. Call them and use them in your referral networks.

In the “bio” component of the biopsychosocial approach, we can do a lot to treat ED with medications and hormones. Testosterone has been shown to help with low libido and erectile function. Checking the patient’s testosterone level can be very helpful. Pills — we are familiar with Viagra, Cialis, Levitra, and Stendra. The oral PDE-5 inhibitors have been around since the late 1990s and they work quite well for many people with ED. Viagra and Cialis are generic now and patients can get them fairly inexpensively with discount coupons from GoodRx or Cost Plus Drugs. They may not even have to worry about insurance coverage.

Pills relax the smooth muscle of the penis so that it fills with blood and becomes erect, but they don’t work for everybody. If pills stop working, we often talk about synergistic treatments — combining pills and devices. Devices for ED should be discussed more often, and clinicians should consider prescribing them. We commonly discuss eyeglasses and wheelchairs, but we don’t talk about the sexual health devices that could help patients have more success and fun in the bedroom.

What are the various types of devices for ED? One common device is a vacuum pump, which can be very effective. This is how they work: The penis is lubricated and placed into the pump. A button on the pump creates suction that brings blood into the penis. The patient then applies a constriction band around the base of the penis to hold that erection in place.

“Sex tech” has really expanded to help patients with ED with devices that vibrate and hold the erection in place. Vibrating devices allow for a better orgasm. We even have devices that monitor erectile fitness (like a Fitbit for the penis), gathering data to help patients understand the firmness of their erections.

Devices are helpful adjuncts, but they don’t always do enough to achieve an erect penis that’s hard enough for penetration. In those cases, we can recommend injections that increase smooth muscle relaxation of the penis. I know it sounds crazy. If the muscles, arteries, and nerves of the penis aren’t functioning well, additional smooth muscle relaxation can be achieved by injecting alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) directly into the penis. It’s a tiny needle. It doesn’t hurt. These injections can be quite helpful for our patients, and we often recommend them.

But what happens when your patient doesn’t even respond to injections or any of the synergistic treatments? They’ve tried everything. Urologists may suggest a surgical option, the penile implant. Penile implants contain a pump inside the scrotum that fills with fluid, allowing a rigid erection. Penile implants are wonderful for patients who can no longer get erections. Talking to a urologist about the pros and the cons and the risks and benefits of surgically placed implants is very important.

Finally, ED is a marker for cardiovascular disease. These patients may need a cardiology workup. They need to improve their general health. We have to ask our patients about their goals and what they care about, and find a toolbox that makes sense for each patient and couple to maximize their sexual health and quality of life. Don’t give up. If you have questions, let us know.

Rachel S. Rubin, MD, is Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Urology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC; Private practice, Rachel Rubin MD PLLC, North Bethesda, Maryland. She disclosed ties with Sprout, Maternal Medical, Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GSK, and Endo.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr Rachel Rubin. I am a urologist with fellowship training in sexual medicine. Today I’m going to explain why I may recommend that your patients put a needle directly into their penises for help with erectile dysfunction (ED).

I know that sounds crazy, but in a recent video when I talked about erection hardness, I acknowledged that it may not be easy to talk with patients about their penises, but it’s important.

ED can be a marker for cardiovascular disease, with 50% of our 50-year-old patients having ED. As physicians, we must do a better job of talking to our patients about ED and letting them know that it’s a marker for overall health.

How do we treat ED? Primary care doctors can do a great deal for patients with ED, and there are other things that urologists can do when you run out of options in your own toolbox.

What’s important for a healthy erection? You need three things: healthy muscle, healthy nerves, and healthy arteries. If anything goes wrong with muscles, nerves, or arteries, this is what leads to ED. Think through the algorithm of your patient’s medical history: Do they have diabetes, which can affect their nerves? Do they have high blood pressure, which can affect their arteries? Do they have problems with testosterone, which can affect the smooth muscles of the penis? Understanding your patient’s history can be really helpful when you figure out what is the best treatment strategy for your patient.

For the penis to work, those smooth muscles have to relax; therefore, your brain has to be relaxed, along with your pelvic floor muscles. The smooth muscle of the penis has to be relaxed so it can fill with blood, increase in girth and size, and hold that erection in place.

To treat ED, we have a biopsychosocial toolbox. Biology refers to the muscles, arteries, and nerves. The psychosocial component is stress: If your brain is stressed, you have a lot of adrenaline around that can tighten those smooth muscles and cause you to lose an erection.

So, what are these treatments? I’ll start with lifestyle. A healthy heart means a healthy penis, so, all of the things you already recommend for lifestyle changes can really help with ED. Sleep is important. Does your patient need a sleep study? Do they have sleep apnea? Are they exercising? Recent data show that exercise may be just as effective, if not more effective, than Viagra. How about a good diet? The Mediterranean diet seems to be the most helpful. So, encourage your patients to make dietary, exercise, sleep, and other lifestyle changes if they want to improve erectile function.

What about sex education? Most physicians didn’t get great education about sex in medical school, but it’s very important to our patients who likewise have had inadequate sex education. Ask questions, talk to them, explain what is normal.

I can’t stress enough how important mental health is to a great sex life. Everyone would benefit from sex therapy and becoming better at sex. We need to get better at communicating and educating patients and their partners to maximize their quality of life. If you need to refer to a specialist, we recommend going to psychologytoday.com or aasect.org to find a local sex therapist. Call them and use them in your referral networks.

In the “bio” component of the biopsychosocial approach, we can do a lot to treat ED with medications and hormones. Testosterone has been shown to help with low libido and erectile function. Checking the patient’s testosterone level can be very helpful. Pills — we are familiar with Viagra, Cialis, Levitra, and Stendra. The oral PDE-5 inhibitors have been around since the late 1990s and they work quite well for many people with ED. Viagra and Cialis are generic now and patients can get them fairly inexpensively with discount coupons from GoodRx or Cost Plus Drugs. They may not even have to worry about insurance coverage.

Pills relax the smooth muscle of the penis so that it fills with blood and becomes erect, but they don’t work for everybody. If pills stop working, we often talk about synergistic treatments — combining pills and devices. Devices for ED should be discussed more often, and clinicians should consider prescribing them. We commonly discuss eyeglasses and wheelchairs, but we don’t talk about the sexual health devices that could help patients have more success and fun in the bedroom.

What are the various types of devices for ED? One common device is a vacuum pump, which can be very effective. This is how they work: The penis is lubricated and placed into the pump. A button on the pump creates suction that brings blood into the penis. The patient then applies a constriction band around the base of the penis to hold that erection in place.

“Sex tech” has really expanded to help patients with ED with devices that vibrate and hold the erection in place. Vibrating devices allow for a better orgasm. We even have devices that monitor erectile fitness (like a Fitbit for the penis), gathering data to help patients understand the firmness of their erections.

Devices are helpful adjuncts, but they don’t always do enough to achieve an erect penis that’s hard enough for penetration. In those cases, we can recommend injections that increase smooth muscle relaxation of the penis. I know it sounds crazy. If the muscles, arteries, and nerves of the penis aren’t functioning well, additional smooth muscle relaxation can be achieved by injecting alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) directly into the penis. It’s a tiny needle. It doesn’t hurt. These injections can be quite helpful for our patients, and we often recommend them.

But what happens when your patient doesn’t even respond to injections or any of the synergistic treatments? They’ve tried everything. Urologists may suggest a surgical option, the penile implant. Penile implants contain a pump inside the scrotum that fills with fluid, allowing a rigid erection. Penile implants are wonderful for patients who can no longer get erections. Talking to a urologist about the pros and the cons and the risks and benefits of surgically placed implants is very important.

Finally, ED is a marker for cardiovascular disease. These patients may need a cardiology workup. They need to improve their general health. We have to ask our patients about their goals and what they care about, and find a toolbox that makes sense for each patient and couple to maximize their sexual health and quality of life. Don’t give up. If you have questions, let us know.

Rachel S. Rubin, MD, is Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Urology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC; Private practice, Rachel Rubin MD PLLC, North Bethesda, Maryland. She disclosed ties with Sprout, Maternal Medical, Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GSK, and Endo.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr Rachel Rubin. I am a urologist with fellowship training in sexual medicine. Today I’m going to explain why I may recommend that your patients put a needle directly into their penises for help with erectile dysfunction (ED).

I know that sounds crazy, but in a recent video when I talked about erection hardness, I acknowledged that it may not be easy to talk with patients about their penises, but it’s important.

ED can be a marker for cardiovascular disease, with 50% of our 50-year-old patients having ED. As physicians, we must do a better job of talking to our patients about ED and letting them know that it’s a marker for overall health.

How do we treat ED? Primary care doctors can do a great deal for patients with ED, and there are other things that urologists can do when you run out of options in your own toolbox.

What’s important for a healthy erection? You need three things: healthy muscle, healthy nerves, and healthy arteries. If anything goes wrong with muscles, nerves, or arteries, this is what leads to ED. Think through the algorithm of your patient’s medical history: Do they have diabetes, which can affect their nerves? Do they have high blood pressure, which can affect their arteries? Do they have problems with testosterone, which can affect the smooth muscles of the penis? Understanding your patient’s history can be really helpful when you figure out what is the best treatment strategy for your patient.

For the penis to work, those smooth muscles have to relax; therefore, your brain has to be relaxed, along with your pelvic floor muscles. The smooth muscle of the penis has to be relaxed so it can fill with blood, increase in girth and size, and hold that erection in place.

To treat ED, we have a biopsychosocial toolbox. Biology refers to the muscles, arteries, and nerves. The psychosocial component is stress: If your brain is stressed, you have a lot of adrenaline around that can tighten those smooth muscles and cause you to lose an erection.

So, what are these treatments? I’ll start with lifestyle. A healthy heart means a healthy penis, so, all of the things you already recommend for lifestyle changes can really help with ED. Sleep is important. Does your patient need a sleep study? Do they have sleep apnea? Are they exercising? Recent data show that exercise may be just as effective, if not more effective, than Viagra. How about a good diet? The Mediterranean diet seems to be the most helpful. So, encourage your patients to make dietary, exercise, sleep, and other lifestyle changes if they want to improve erectile function.

What about sex education? Most physicians didn’t get great education about sex in medical school, but it’s very important to our patients who likewise have had inadequate sex education. Ask questions, talk to them, explain what is normal.

I can’t stress enough how important mental health is to a great sex life. Everyone would benefit from sex therapy and becoming better at sex. We need to get better at communicating and educating patients and their partners to maximize their quality of life. If you need to refer to a specialist, we recommend going to psychologytoday.com or aasect.org to find a local sex therapist. Call them and use them in your referral networks.

In the “bio” component of the biopsychosocial approach, we can do a lot to treat ED with medications and hormones. Testosterone has been shown to help with low libido and erectile function. Checking the patient’s testosterone level can be very helpful. Pills — we are familiar with Viagra, Cialis, Levitra, and Stendra. The oral PDE-5 inhibitors have been around since the late 1990s and they work quite well for many people with ED. Viagra and Cialis are generic now and patients can get them fairly inexpensively with discount coupons from GoodRx or Cost Plus Drugs. They may not even have to worry about insurance coverage.

Pills relax the smooth muscle of the penis so that it fills with blood and becomes erect, but they don’t work for everybody. If pills stop working, we often talk about synergistic treatments — combining pills and devices. Devices for ED should be discussed more often, and clinicians should consider prescribing them. We commonly discuss eyeglasses and wheelchairs, but we don’t talk about the sexual health devices that could help patients have more success and fun in the bedroom.

What are the various types of devices for ED? One common device is a vacuum pump, which can be very effective. This is how they work: The penis is lubricated and placed into the pump. A button on the pump creates suction that brings blood into the penis. The patient then applies a constriction band around the base of the penis to hold that erection in place.

“Sex tech” has really expanded to help patients with ED with devices that vibrate and hold the erection in place. Vibrating devices allow for a better orgasm. We even have devices that monitor erectile fitness (like a Fitbit for the penis), gathering data to help patients understand the firmness of their erections.

Devices are helpful adjuncts, but they don’t always do enough to achieve an erect penis that’s hard enough for penetration. In those cases, we can recommend injections that increase smooth muscle relaxation of the penis. I know it sounds crazy. If the muscles, arteries, and nerves of the penis aren’t functioning well, additional smooth muscle relaxation can be achieved by injecting alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) directly into the penis. It’s a tiny needle. It doesn’t hurt. These injections can be quite helpful for our patients, and we often recommend them.

But what happens when your patient doesn’t even respond to injections or any of the synergistic treatments? They’ve tried everything. Urologists may suggest a surgical option, the penile implant. Penile implants contain a pump inside the scrotum that fills with fluid, allowing a rigid erection. Penile implants are wonderful for patients who can no longer get erections. Talking to a urologist about the pros and the cons and the risks and benefits of surgically placed implants is very important.

Finally, ED is a marker for cardiovascular disease. These patients may need a cardiology workup. They need to improve their general health. We have to ask our patients about their goals and what they care about, and find a toolbox that makes sense for each patient and couple to maximize their sexual health and quality of life. Don’t give up. If you have questions, let us know.

Rachel S. Rubin, MD, is Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Urology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC; Private practice, Rachel Rubin MD PLLC, North Bethesda, Maryland. She disclosed ties with Sprout, Maternal Medical, Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GSK, and Endo.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Report: CKD Severity Linked to Thinning of Retina, Choroid Layers

Changes in tissue thickness in the back of the eye can correlate with worsening or improvement of renal problems and could help predict who will have worsening of kidney function, a new analysis report finds.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, is the first to show an association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the thickness of the retinal and choroidal layers in the back of the eye as measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology commonly used to evaluate eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic eye disease, and retinal detachments.

“These are common scans that people get at the opticians and now in many hospitals,” said Neeraj Dhaun, MD, PhD, a professor of nephrology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. (Opticians in the United Kingdom are the equivalent of optometrists in North America.)

CKD Severity Equals Thinner Retinas

“We scanned the back of eye of healthy people as well as patients with various types and degrees of kidney disease, and we found that two layers in the back of eye, the retina and the choroid, were thinner in patients with kidney disease compared to people who are healthy, and that the extent of this thinning predicts whether kidney function would decline going forward over a period of 2 or 3 years,” Dr. Dhaun, the corresponding author of the new paper, said.

The publication is a report of four different studies. The first study measured OCT metrics in 112 patients with CKD, 92 patients with a functional kidney transplant, and 86 control volunteers. The researchers found the retina was 5% thinner in patients with CKD than in healthy controls. They also found that patients with CKD had reduced macular volume: 8.44 ± .44 mm3 vs 8.73 ± .36 mm3 (P < .001). The choroid was also found to be thinner at each of three macular locations measured in patients with CKD vs control volunteers. At baseline, CKD and transplant patients had significantly lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 55 ± 27 and 55 ± 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared with control volunteers at 97 ± 14 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The second study reported on OCT measurements and kidney histologic injury in 50 patients who had a kidney biopsy within 30 days of their OCT. It found that choroidal thinning at all three macular locations was independently associated with more extensive kidney scarring.

The third study focused on 25 patients with kidney failure who had a kidney transplant. Their eGFR improved from 8 ± 3 to 58 ± 21 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the first week after the transplant. The choroid in these patients thickened about 5% at 1 week and by about 10% at 1 month posttransplant. OCT of 22 kidney donors showed thickening of the choroid a week after nephrectomy before a tendency to thinning over the next year.

The fourth study found that for patients with stable CKD, every 1 mm3 decrease in macular volume correlated to an increased odds of a decline in eGFR by more than 10% at 1 year (2.48; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .01) and by more than 20% at 2 years (3.75; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .004).

Exploring the Kidney-Eye Connection

The potential explanation for the correlation between retinal and choroidal thickness and kidney function is unclear, Dr. Dhaun said.

“We don’t know the exact mechanisms, and these are difficult to define from studies in patients, which is why we are doing more work in animal models of kidney disease to see if we can establish the pathways that lead to the changes in the eye,” he said.

“However,” Dr. Dhaun added, “what we do know is that kidney disease affects the whole body. For example, kidney disease can lead to high blood pressure and heart disease, as well as diseases in the brain, and it is these effects of kidney disease on the body as whole that we are probably picking up in the back of the eye.”

OCT has the potential to make the monitoring of patients with CKD and kidney transplant more convenient than it is now, Dr. Dhaun said. “These scanners are available in the community, and what would be ideal at some point in the future is to be able to do a patient’s kidney health check in the community potentially incorporating OCT scanning alongside blood-pressure monitoring and other healthcare measures,” he said.

“The findings provide an exciting example of how noninvasive retinal imaging using OCT can provide quantitative biomarkers of systemic disease,” Amir Kashani, MD, PhD, the Boone Pickens Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Engineering at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, told this news organization. “It is striking that their findings demonstrate some potential of reversible changes in choroidal perfusion after kidney transplantation.”

The finding that choroidal thickness changes in CKD are at least partly reversible with kidney transplantation is a revelation, Dr. Kashani said, and may point to a greater role for ophthalmologists in managing systemic disease.

“Ophthalmologists can and should use their unique experience and understanding of the eye to help monitor and manage systemic conditions in collaboration with our medicine colleagues,” he said. “There are many systemic diseases that can impact the eye and ophthalmologist are uniquely positioned to help interpret those findings.”

Dr. Kashani noted that a particular strength of the report was the comparison of choroidal measurements in patients who had kidney transplantation and those that had a nephrectomy. “The consistent direction of changes in these two groups suggests the study findings are real and meaningful,” he said.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Dhaun and co-authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kashani disclosed a financial relationship with Carl Zeiss Meditec.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Changes in tissue thickness in the back of the eye can correlate with worsening or improvement of renal problems and could help predict who will have worsening of kidney function, a new analysis report finds.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, is the first to show an association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the thickness of the retinal and choroidal layers in the back of the eye as measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology commonly used to evaluate eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic eye disease, and retinal detachments.

“These are common scans that people get at the opticians and now in many hospitals,” said Neeraj Dhaun, MD, PhD, a professor of nephrology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. (Opticians in the United Kingdom are the equivalent of optometrists in North America.)

CKD Severity Equals Thinner Retinas

“We scanned the back of eye of healthy people as well as patients with various types and degrees of kidney disease, and we found that two layers in the back of eye, the retina and the choroid, were thinner in patients with kidney disease compared to people who are healthy, and that the extent of this thinning predicts whether kidney function would decline going forward over a period of 2 or 3 years,” Dr. Dhaun, the corresponding author of the new paper, said.

The publication is a report of four different studies. The first study measured OCT metrics in 112 patients with CKD, 92 patients with a functional kidney transplant, and 86 control volunteers. The researchers found the retina was 5% thinner in patients with CKD than in healthy controls. They also found that patients with CKD had reduced macular volume: 8.44 ± .44 mm3 vs 8.73 ± .36 mm3 (P < .001). The choroid was also found to be thinner at each of three macular locations measured in patients with CKD vs control volunteers. At baseline, CKD and transplant patients had significantly lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 55 ± 27 and 55 ± 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared with control volunteers at 97 ± 14 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The second study reported on OCT measurements and kidney histologic injury in 50 patients who had a kidney biopsy within 30 days of their OCT. It found that choroidal thinning at all three macular locations was independently associated with more extensive kidney scarring.

The third study focused on 25 patients with kidney failure who had a kidney transplant. Their eGFR improved from 8 ± 3 to 58 ± 21 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the first week after the transplant. The choroid in these patients thickened about 5% at 1 week and by about 10% at 1 month posttransplant. OCT of 22 kidney donors showed thickening of the choroid a week after nephrectomy before a tendency to thinning over the next year.

The fourth study found that for patients with stable CKD, every 1 mm3 decrease in macular volume correlated to an increased odds of a decline in eGFR by more than 10% at 1 year (2.48; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .01) and by more than 20% at 2 years (3.75; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .004).

Exploring the Kidney-Eye Connection

The potential explanation for the correlation between retinal and choroidal thickness and kidney function is unclear, Dr. Dhaun said.

“We don’t know the exact mechanisms, and these are difficult to define from studies in patients, which is why we are doing more work in animal models of kidney disease to see if we can establish the pathways that lead to the changes in the eye,” he said.

“However,” Dr. Dhaun added, “what we do know is that kidney disease affects the whole body. For example, kidney disease can lead to high blood pressure and heart disease, as well as diseases in the brain, and it is these effects of kidney disease on the body as whole that we are probably picking up in the back of the eye.”

OCT has the potential to make the monitoring of patients with CKD and kidney transplant more convenient than it is now, Dr. Dhaun said. “These scanners are available in the community, and what would be ideal at some point in the future is to be able to do a patient’s kidney health check in the community potentially incorporating OCT scanning alongside blood-pressure monitoring and other healthcare measures,” he said.

“The findings provide an exciting example of how noninvasive retinal imaging using OCT can provide quantitative biomarkers of systemic disease,” Amir Kashani, MD, PhD, the Boone Pickens Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Engineering at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, told this news organization. “It is striking that their findings demonstrate some potential of reversible changes in choroidal perfusion after kidney transplantation.”

The finding that choroidal thickness changes in CKD are at least partly reversible with kidney transplantation is a revelation, Dr. Kashani said, and may point to a greater role for ophthalmologists in managing systemic disease.

“Ophthalmologists can and should use their unique experience and understanding of the eye to help monitor and manage systemic conditions in collaboration with our medicine colleagues,” he said. “There are many systemic diseases that can impact the eye and ophthalmologist are uniquely positioned to help interpret those findings.”

Dr. Kashani noted that a particular strength of the report was the comparison of choroidal measurements in patients who had kidney transplantation and those that had a nephrectomy. “The consistent direction of changes in these two groups suggests the study findings are real and meaningful,” he said.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Dhaun and co-authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kashani disclosed a financial relationship with Carl Zeiss Meditec.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Changes in tissue thickness in the back of the eye can correlate with worsening or improvement of renal problems and could help predict who will have worsening of kidney function, a new analysis report finds.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, is the first to show an association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the thickness of the retinal and choroidal layers in the back of the eye as measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology commonly used to evaluate eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic eye disease, and retinal detachments.

“These are common scans that people get at the opticians and now in many hospitals,” said Neeraj Dhaun, MD, PhD, a professor of nephrology at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. (Opticians in the United Kingdom are the equivalent of optometrists in North America.)

CKD Severity Equals Thinner Retinas

“We scanned the back of eye of healthy people as well as patients with various types and degrees of kidney disease, and we found that two layers in the back of eye, the retina and the choroid, were thinner in patients with kidney disease compared to people who are healthy, and that the extent of this thinning predicts whether kidney function would decline going forward over a period of 2 or 3 years,” Dr. Dhaun, the corresponding author of the new paper, said.

The publication is a report of four different studies. The first study measured OCT metrics in 112 patients with CKD, 92 patients with a functional kidney transplant, and 86 control volunteers. The researchers found the retina was 5% thinner in patients with CKD than in healthy controls. They also found that patients with CKD had reduced macular volume: 8.44 ± .44 mm3 vs 8.73 ± .36 mm3 (P < .001). The choroid was also found to be thinner at each of three macular locations measured in patients with CKD vs control volunteers. At baseline, CKD and transplant patients had significantly lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 55 ± 27 and 55 ± 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared with control volunteers at 97 ± 14 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The second study reported on OCT measurements and kidney histologic injury in 50 patients who had a kidney biopsy within 30 days of their OCT. It found that choroidal thinning at all three macular locations was independently associated with more extensive kidney scarring.

The third study focused on 25 patients with kidney failure who had a kidney transplant. Their eGFR improved from 8 ± 3 to 58 ± 21 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the first week after the transplant. The choroid in these patients thickened about 5% at 1 week and by about 10% at 1 month posttransplant. OCT of 22 kidney donors showed thickening of the choroid a week after nephrectomy before a tendency to thinning over the next year.

The fourth study found that for patients with stable CKD, every 1 mm3 decrease in macular volume correlated to an increased odds of a decline in eGFR by more than 10% at 1 year (2.48; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .01) and by more than 20% at 2 years (3.75; 95% CI, 1.26-5.08; P = .004).

Exploring the Kidney-Eye Connection

The potential explanation for the correlation between retinal and choroidal thickness and kidney function is unclear, Dr. Dhaun said.

“We don’t know the exact mechanisms, and these are difficult to define from studies in patients, which is why we are doing more work in animal models of kidney disease to see if we can establish the pathways that lead to the changes in the eye,” he said.

“However,” Dr. Dhaun added, “what we do know is that kidney disease affects the whole body. For example, kidney disease can lead to high blood pressure and heart disease, as well as diseases in the brain, and it is these effects of kidney disease on the body as whole that we are probably picking up in the back of the eye.”

OCT has the potential to make the monitoring of patients with CKD and kidney transplant more convenient than it is now, Dr. Dhaun said. “These scanners are available in the community, and what would be ideal at some point in the future is to be able to do a patient’s kidney health check in the community potentially incorporating OCT scanning alongside blood-pressure monitoring and other healthcare measures,” he said.

“The findings provide an exciting example of how noninvasive retinal imaging using OCT can provide quantitative biomarkers of systemic disease,” Amir Kashani, MD, PhD, the Boone Pickens Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Engineering at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, told this news organization. “It is striking that their findings demonstrate some potential of reversible changes in choroidal perfusion after kidney transplantation.”

The finding that choroidal thickness changes in CKD are at least partly reversible with kidney transplantation is a revelation, Dr. Kashani said, and may point to a greater role for ophthalmologists in managing systemic disease.

“Ophthalmologists can and should use their unique experience and understanding of the eye to help monitor and manage systemic conditions in collaboration with our medicine colleagues,” he said. “There are many systemic diseases that can impact the eye and ophthalmologist are uniquely positioned to help interpret those findings.”

Dr. Kashani noted that a particular strength of the report was the comparison of choroidal measurements in patients who had kidney transplantation and those that had a nephrectomy. “The consistent direction of changes in these two groups suggests the study findings are real and meaningful,” he said.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Dhaun and co-authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kashani disclosed a financial relationship with Carl Zeiss Meditec.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

What if a single GLP-1 shot could last for months?

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL REPORTS MEDICINE

How to prescribe Zepbound

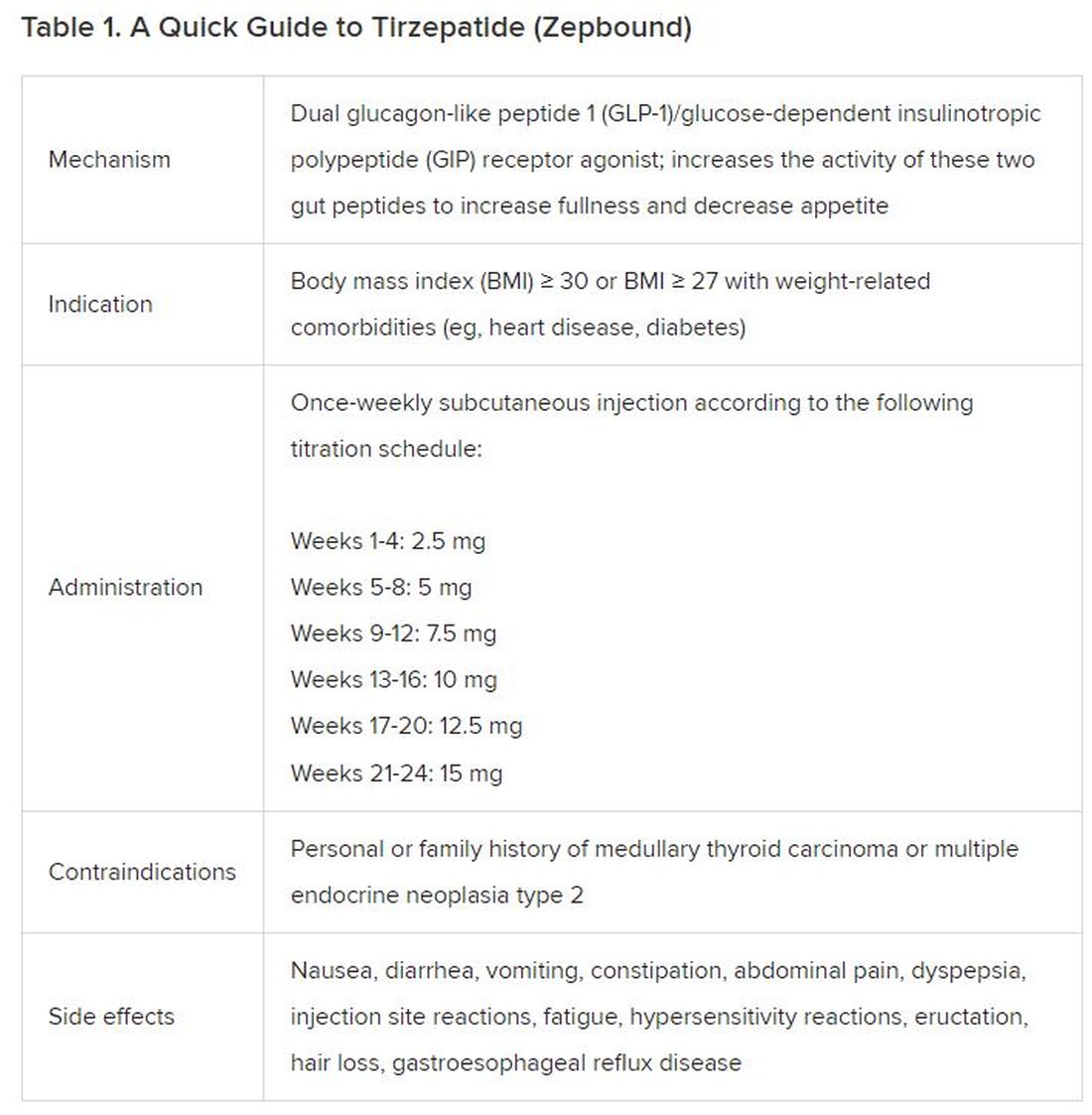

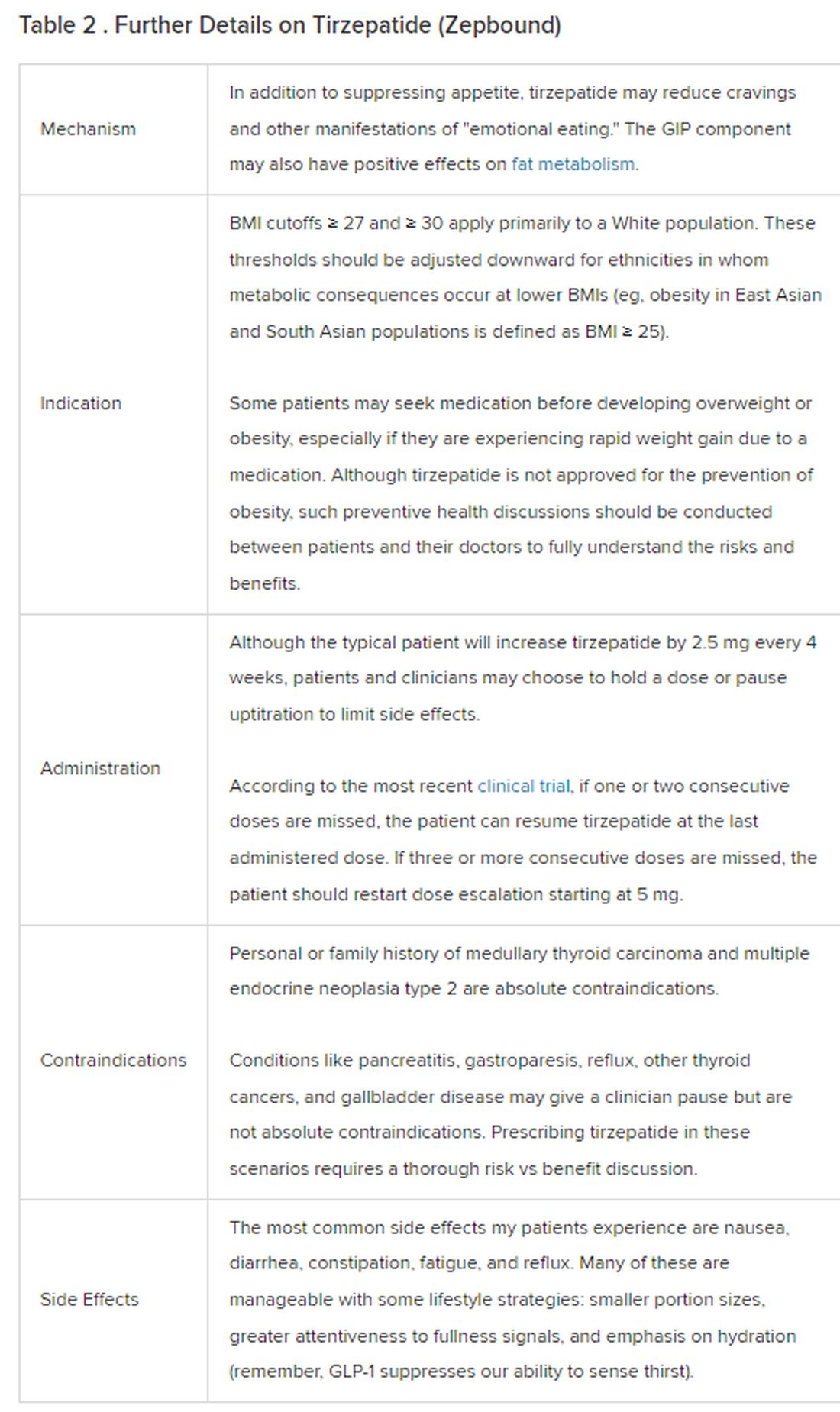

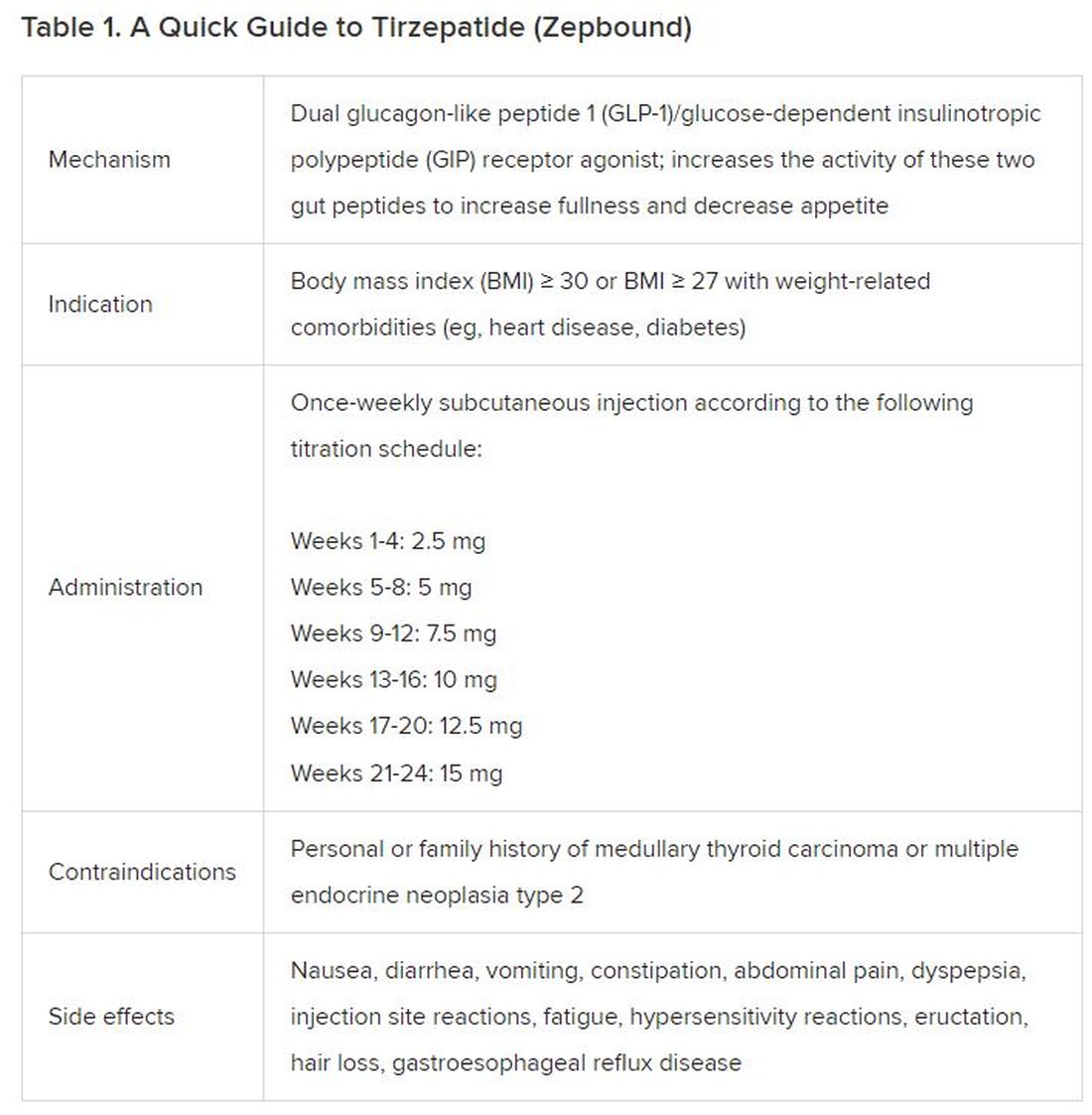

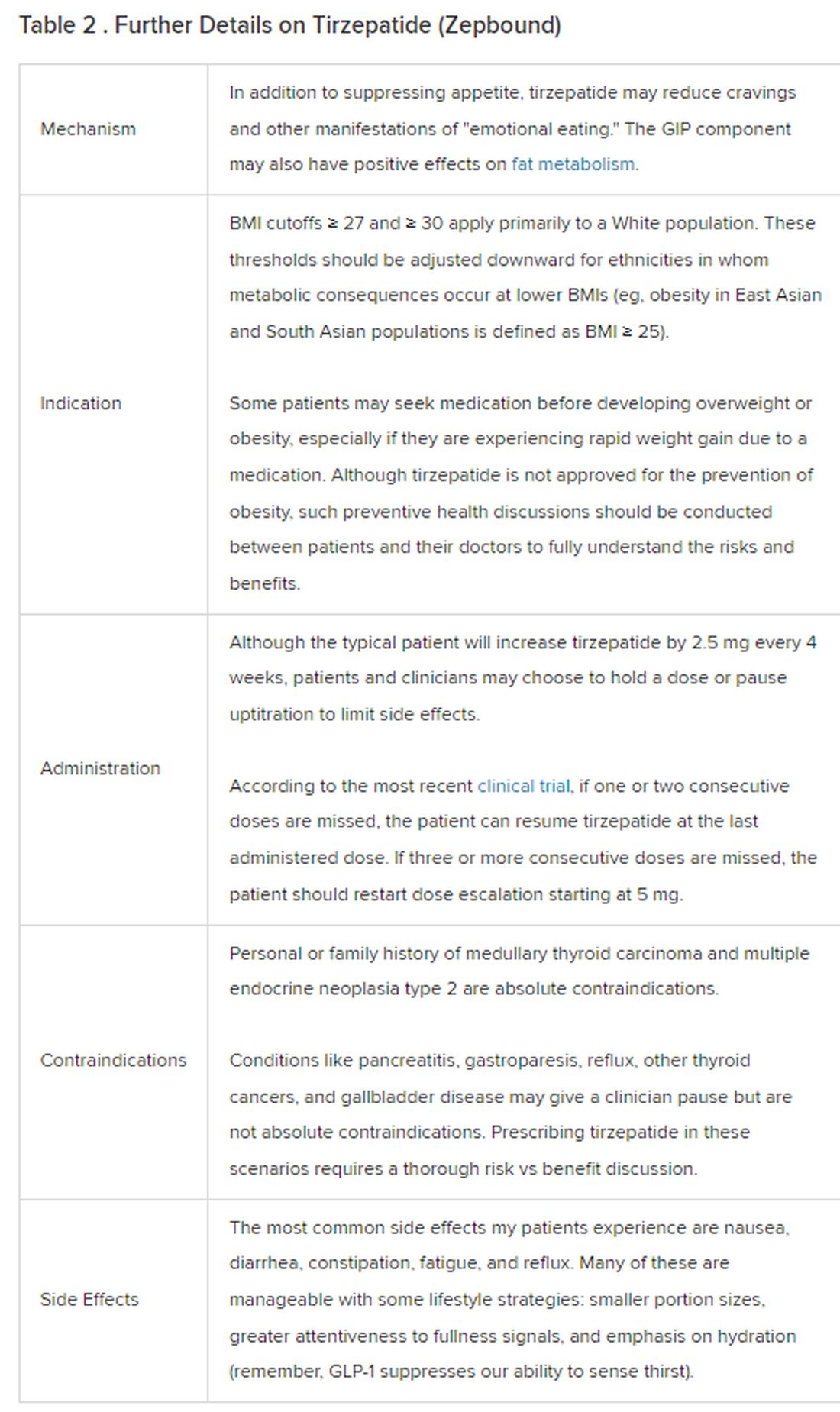

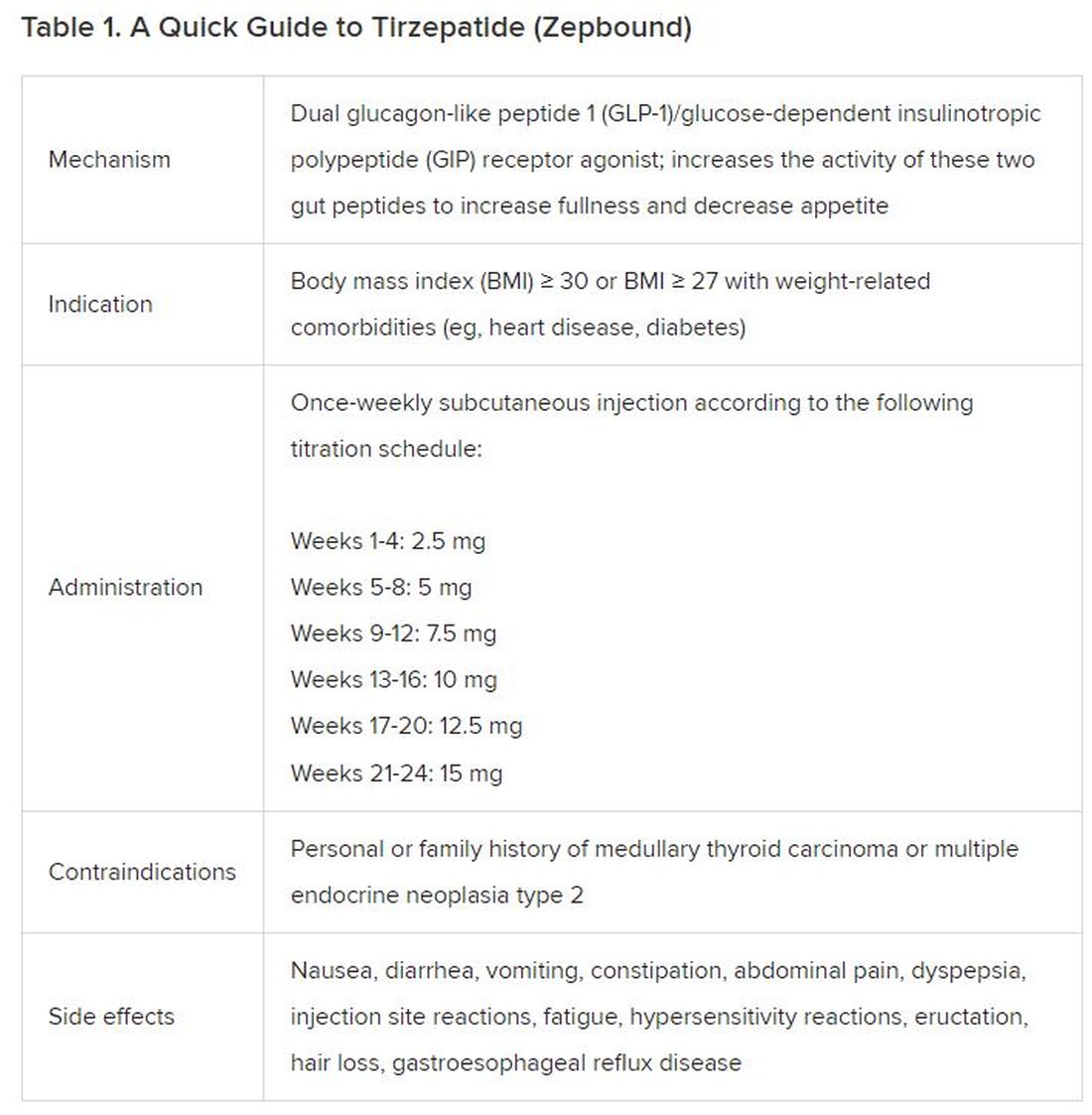

December marks the advent of the approval of tirzepatide (Zepbound) for on-label treatment of obesity. In November 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of obesity in adults.

In May 2022, the FDA approved Mounjaro, which is tirzepatide, for type 2 diabetes. Since then, many physicians, including myself, have prescribed it off-label for obesity. As an endocrinologist treating both obesity and diabetes,

The Expertise

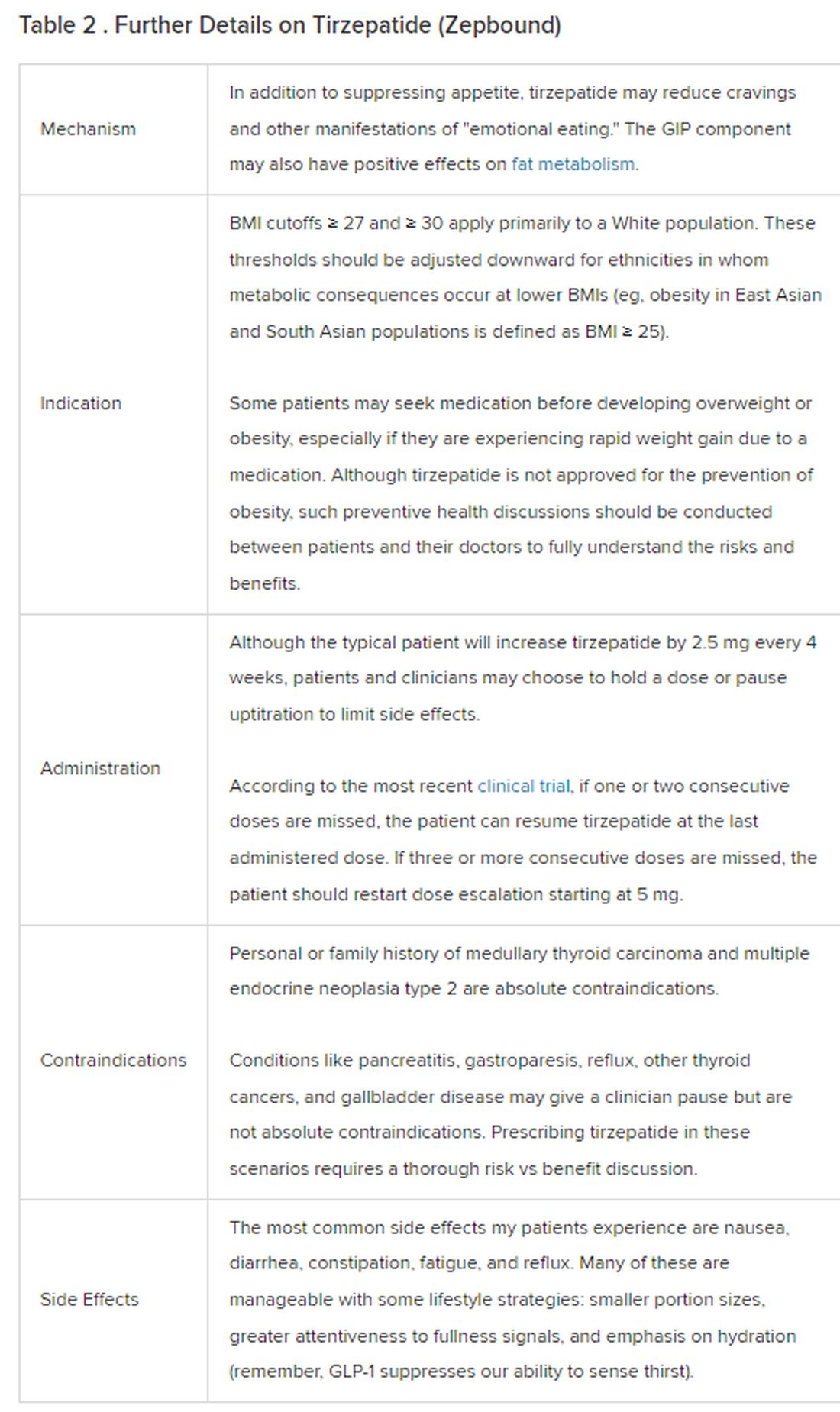

Because GLP-1 receptor agonists have been around since 2005, we’ve had over a decade of clinical experience with these medications. Table 2 provides more nuanced information on tirzepatide (as Zepbound, for obesity) based on our experiences with dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (as Mounjaro).

The Reality

In today’s increasingly complex healthcare system, the reality of providing high-quality obesity care is challenging. When discussing tirzepatide with patients, I use a 4 Cs schematic — comorbidities, cautions, costs, choices — to cover the most frequently asked questions.

Comorbidities

In trials, tirzepatide reduced A1c by about 2%. In one diabetes trial, tirzepatide reduced liver fat content significantly more than the comparator (insulin), and trials of tirzepatide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are ongoing. A prespecified meta-analysis of tirzepatide and cardiovascular disease estimated a 20% reduction in the risk for cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hospitalized unstable angina. Tirzepatide as well as other GLP-1 agonists may be beneficial in alcohol use disorder. Prescribing tirzepatide to patients who have or are at risk of developing such comorbidities is an ideal way to target multiple metabolic diseases with one agent.

Cautions

The first principle of medicine is “do no harm.” Tirzepatide may be a poor option for individuals with a history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Because tirzepatide may interfere with the efficacy of estrogen-containing contraceptives during its uptitration phase, women should speak with their doctors about appropriate birth control options (eg, progestin-only, barrier methods). In clinical trials of tirzepatide, male participants were also advised to use reliable contraception. If patients are family-planning, tirzepatide should be discontinued 2 months (for women) and 4 months (for men) before conception, because its effects on fertility or pregnancy are currently unknown.

Costs

At a retail price of $1279 per month, Zepbound is only slightly more affordable than its main competitor, Wegovy (semaglutide 2.4 mg). Complex pharmacy negotiations may reduce this cost, but even with rebates, coupons, and commercial insurance, these costs still place tirzepatide out of reach for many patients. For patients who cannot access tirzepatide, clinicians should discuss more cost-feasible, evidence-based alternatives: for example, phentermine, phentermine-topiramate, naltrexone-bupropion, metformin, bupropion, or topiramate.

Choices

Patient preference drives much of today’s clinical decision-making. Some patients may be switching from semaglutide to tirzepatide, whether by choice or on the basis of physician recommendation. Although no head-to-head obesity trial exists, data from SURPASS-2 and SUSTAIN-FORTE can inform therapeutic equivalence:

- Semaglutide 1.0 mg to tirzepatide 2.5 mg will be a step-down; 5 mg will be a step-up

- Semaglutide 2.0 or 2.4 mg to tirzepatide 5 mg is probably equivalent

The decision to switch therapeutics may depend on weight loss goals, side effect tolerability, or insurance coverage. As with all medications, the use of tirzepatide should progress with shared decision-making, thorough discussions of risks vs benefits, and individualized regimens tailored to each patient’s needs.

The newly approved Zepbound is a valuable addition to our toolbox of obesity treatments. Patients and providers alike are excited for its potential as a highly effective antiobesity medication that can cause a degree of weight loss necessary to reverse comorbidities. The medical management of obesity with agents like tirzepatide holds great promise in addressing today’s obesity epidemic.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed ties to Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.