User login

Subungual Onycholemmal Cyst of the Toenail Mimicking Subungual Melanoma

Case Report

A 23-year-old woman presented with a horizontal split along the midline of the right great toenail associated with some tenderness of 2 to 3 months’ duration. Approximately 5 years prior, she noticed a bluish-colored area under the nail that had been steadily increasing in size. She denied a history of trauma, drainage, or bleeding. There was no history of other nail abnormalities. Her medications and personal, family, and social history were noncontributory.

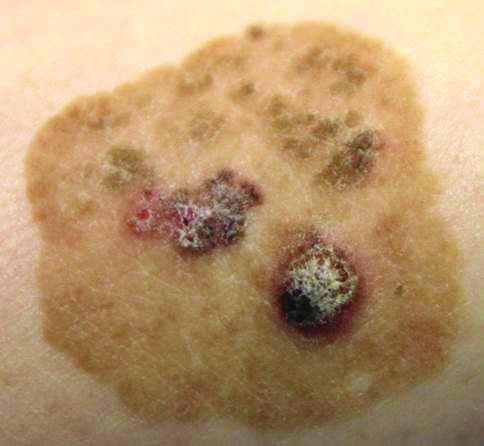

Physical examination of the right great toenail revealed a horizontal split of the nail plate with a bluish hue visible under the nail plate (Figure 1A). The remaining toenails and fingernails were normal. A punch biopsy of the nail bed was performed with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of subungual melanoma versus melanocytic nevus versus cyst (Figure 1B). Nail plate avulsion revealed a blackened nail bed dotted with areas of bluish color and a red friable nodule present focally. Upon further inspection, extension was apparent into the distal matrix.

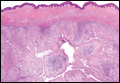

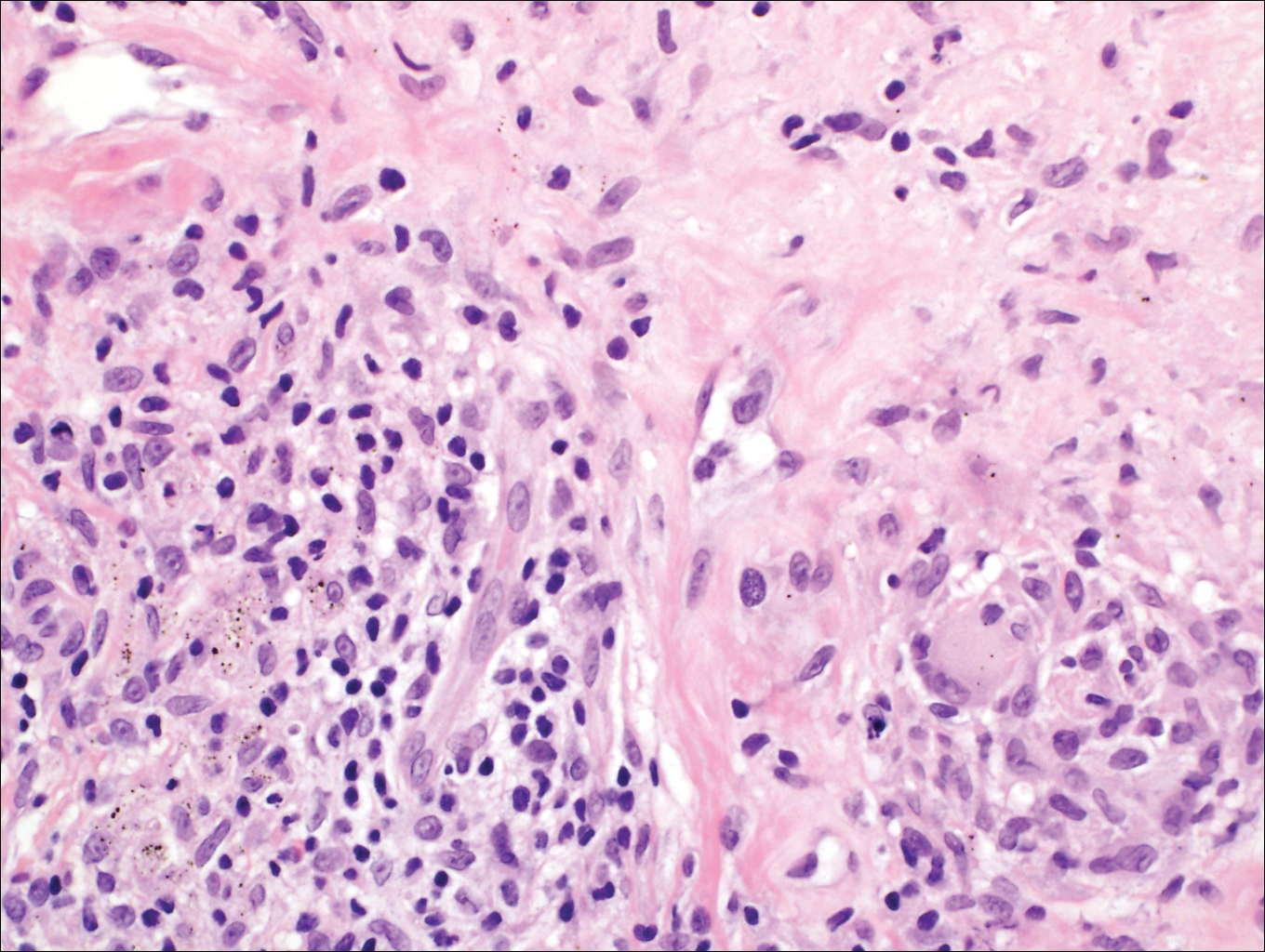

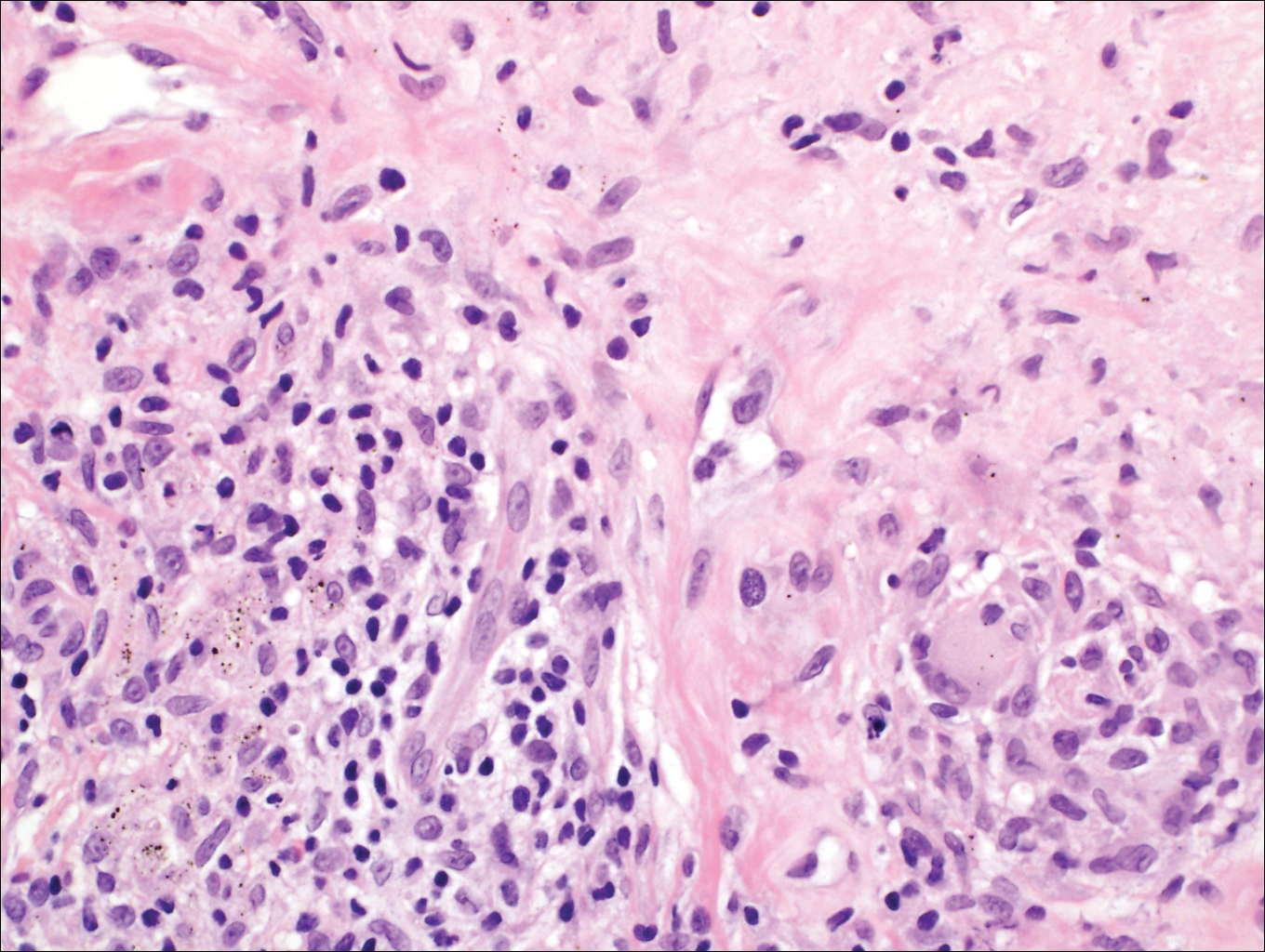

Histopathologic examination revealed a cystic structure with an epithelial lining mostly reminiscent of an isthmus catagen cyst admixed with the presence of both an intermittent focal granular layer and an eosinophilic cuticle surrounding pink laminated keratin, most consistent with a diagnosis of subungual onycholemmal cyst (SOC)(Figure 2). A reexcision was performed with removal of half of the nail bed, including a portion of the distal matrix extending inferiorly to the bone. Variably sized, epithelium-lined, keratin-filled cystic structures emanated from the nail bed epithelium. There were foci of hemorrhage and granulation tissue secondary to cyst rupture (Figure 3). The defect healed by secondary intention. No clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 6-month follow-up.

Subungual onycholemmal cysts, also known as subungual epidermoid cysts or subungual epidermoid inclusions, are rare and distinctive nail abnormalities occurring in the dermis of the nail bed. We present a case of an SOC in a toenail mimicking subungual malignant melanoma.

Originally described by Samman1 in 1959, SOCs were attributed to trauma to the nail with resultant implantation of the epidermis into the deeper tissue. Lewin2,3 examined 90 postmortem fingernail and nail bed samples and found 8 subungual epidermoid cysts associated with clubbing of the fingernails. He postulated that the early pathogenesis of clubbing involved dermal fibroblast proliferation in the nail bed, leading to sequestration of nail bed epithelium into the dermis with resultant cyst formation. Microscopic subungual cysts also were identified in normal-appearing nails without evidence of trauma, thought to have arisen from the tips of the nail bed rete ridges by a process of bulbous proliferation rather than sequestration. These findings in normal nails suggest that SOCs may represent a more common entity than previously recognized.

It is imperative to recognize the presence of nail unit tumors early because of the risk for permanent nail plate dystrophy and the possibility of a malignant tumor.4,5 Subungual onycholemmal cysts may present with a wide spectrum of clinical findings including marked subungual hyperkeratosis, onychodystrophy, ridging, nail bed pigmentation, clubbing, thickening, or less often a normal-appearing nail. Based on reported cases, several trends are evident. Although nail dystrophy is most often asymptomatic, pain is not uncommon.5,6 It most commonly involves single digits, predominantly thumbs and great toenails.7,8 This predilection suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Of note, trauma to the nail may occur years before the development of the lesions or it may not be recalled at all.

Diagnosis requires a degree of clinical suspicion and a nail bed biopsy with partial or total nail plate avulsion to visualize the pathologic portion of the nail bed. Because surgical intervention may lead to the implantation of epithelium, recurrences after nail biopsy or excision may occur.

In contrast to epidermal inclusion cysts arising in the skin, most SOCs do not have a granular layer.9 Hair and nails represent analogous differentiation products of the ectoderm. The nail matrix is homologous to portions of the hair matrix, while the nail bed epithelium is comparable to the outer root sheath of the hair follicle.7 Subungual onycholemmal cysts originate from the nail bed epithelium, which keratinizes in the absence of a granular layer, similar to the follicular isthmus outer root sheath. Thus, SOCs are comparable to the outer root sheath–derived isthmus-catagen cysts because of their abrupt central keratinization.8

Subungual onycholemmal cysts also must be distinguished from slowly growing malignant tumors of the nail bed epithelium, referred to as onycholemmal carcinomas by Alessi et al.10 This entity characteristically presents in elderly patients as a slowly growing, circumscribed, subungual discoloration that may ulcerate, destroying the nail apparatus and penetrating the phalangeal bone. On histopathology, it is characterized by small cysts filled with eosinophilic keratin devoid of a granular layer and lined by atypical squamous epithelium accompanied by solid nests and strands of atypical keratinocytes within the dermis.11 When a cystic component and clear cells predominate, the designation of malignant proliferating onycholemmal cyst has been applied. Its infiltrative growth pattern with destruction of the underlying bone makes it an important entity to exclude when considering the differential diagnosis of tumors of the nail bed.

Subungual melanomas comprise only 1% to 3% of malignant melanomas and 85% are initially misdiagnosed due to their rarity and nonspecific variable presentation. Aside from clinical evidence of Hutchinson sign in the early stages in almost all cases, accurate diagnosis of subungual melanoma and differentiation from SOCs relies on histopathology. A biopsy is necessary to make the diagnosis, but even microscopic findings may be nonspecific during the early stages.

Conclusion

We report a case of a 23-year-old woman with horizontal ridging and tenderness of the right great toenail associated with pigmentation of 5 years’ duration due to an SOC. The etiology of these subungual cysts, with or without nail abnormalities, still remains unclear. Its predilection for the thumbs and great toenails suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Because of the rarity of this entity, there are no guidelines for surgical treatment. Subungual onycholemmal cysts may be an underrecognized and more common entity that must be considered when discussing tumors of the nail unit.

- Samman PD. The human toe nail. its genesis and blood supply. Br J Dermatol. 1959;71:296-302.

- Lewin K. The normal fingernail. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:421-430.

- Lewin K. Subungual epidermoid inclusions. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:671-675.

- Dominguez-Cherit J, Chanussot-Deprez C, Maria-Sarti H, et al. Nail unit tumors: a study of 234 patients in the dermatology department of the “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital in Mexico City. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1363-1371.

- Sáez-de-Ocariz MM, Domínguez-Cherit J, García-Corona C. Subungual epidermoid cysts. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:524-526.

- Molly DO, Herbert K. Subungual epidermoid cyst. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:345.

- Telang GH, Jellinek N. Multiple calcified subungual epidermoid inclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:336-339.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A. Subungual epidermoid inclusions: report of 8 cases. Dermatologica. 1989;178:209-212.

- Takiyoshi N, Nakano H, Matsuzaki T, et al. An eclipse in the subungual space: a diagnostic sign for a subungual epidermal cyst? Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:962-963.

- Alessi E, Coggi A, Gianotti R, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:397-402.

- Inaoki M, Makino E, Adachi M, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:577-580.

Case Report

A 23-year-old woman presented with a horizontal split along the midline of the right great toenail associated with some tenderness of 2 to 3 months’ duration. Approximately 5 years prior, she noticed a bluish-colored area under the nail that had been steadily increasing in size. She denied a history of trauma, drainage, or bleeding. There was no history of other nail abnormalities. Her medications and personal, family, and social history were noncontributory.

Physical examination of the right great toenail revealed a horizontal split of the nail plate with a bluish hue visible under the nail plate (Figure 1A). The remaining toenails and fingernails were normal. A punch biopsy of the nail bed was performed with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of subungual melanoma versus melanocytic nevus versus cyst (Figure 1B). Nail plate avulsion revealed a blackened nail bed dotted with areas of bluish color and a red friable nodule present focally. Upon further inspection, extension was apparent into the distal matrix.

Histopathologic examination revealed a cystic structure with an epithelial lining mostly reminiscent of an isthmus catagen cyst admixed with the presence of both an intermittent focal granular layer and an eosinophilic cuticle surrounding pink laminated keratin, most consistent with a diagnosis of subungual onycholemmal cyst (SOC)(Figure 2). A reexcision was performed with removal of half of the nail bed, including a portion of the distal matrix extending inferiorly to the bone. Variably sized, epithelium-lined, keratin-filled cystic structures emanated from the nail bed epithelium. There were foci of hemorrhage and granulation tissue secondary to cyst rupture (Figure 3). The defect healed by secondary intention. No clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 6-month follow-up.

Subungual onycholemmal cysts, also known as subungual epidermoid cysts or subungual epidermoid inclusions, are rare and distinctive nail abnormalities occurring in the dermis of the nail bed. We present a case of an SOC in a toenail mimicking subungual malignant melanoma.

Originally described by Samman1 in 1959, SOCs were attributed to trauma to the nail with resultant implantation of the epidermis into the deeper tissue. Lewin2,3 examined 90 postmortem fingernail and nail bed samples and found 8 subungual epidermoid cysts associated with clubbing of the fingernails. He postulated that the early pathogenesis of clubbing involved dermal fibroblast proliferation in the nail bed, leading to sequestration of nail bed epithelium into the dermis with resultant cyst formation. Microscopic subungual cysts also were identified in normal-appearing nails without evidence of trauma, thought to have arisen from the tips of the nail bed rete ridges by a process of bulbous proliferation rather than sequestration. These findings in normal nails suggest that SOCs may represent a more common entity than previously recognized.

It is imperative to recognize the presence of nail unit tumors early because of the risk for permanent nail plate dystrophy and the possibility of a malignant tumor.4,5 Subungual onycholemmal cysts may present with a wide spectrum of clinical findings including marked subungual hyperkeratosis, onychodystrophy, ridging, nail bed pigmentation, clubbing, thickening, or less often a normal-appearing nail. Based on reported cases, several trends are evident. Although nail dystrophy is most often asymptomatic, pain is not uncommon.5,6 It most commonly involves single digits, predominantly thumbs and great toenails.7,8 This predilection suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Of note, trauma to the nail may occur years before the development of the lesions or it may not be recalled at all.

Diagnosis requires a degree of clinical suspicion and a nail bed biopsy with partial or total nail plate avulsion to visualize the pathologic portion of the nail bed. Because surgical intervention may lead to the implantation of epithelium, recurrences after nail biopsy or excision may occur.

In contrast to epidermal inclusion cysts arising in the skin, most SOCs do not have a granular layer.9 Hair and nails represent analogous differentiation products of the ectoderm. The nail matrix is homologous to portions of the hair matrix, while the nail bed epithelium is comparable to the outer root sheath of the hair follicle.7 Subungual onycholemmal cysts originate from the nail bed epithelium, which keratinizes in the absence of a granular layer, similar to the follicular isthmus outer root sheath. Thus, SOCs are comparable to the outer root sheath–derived isthmus-catagen cysts because of their abrupt central keratinization.8

Subungual onycholemmal cysts also must be distinguished from slowly growing malignant tumors of the nail bed epithelium, referred to as onycholemmal carcinomas by Alessi et al.10 This entity characteristically presents in elderly patients as a slowly growing, circumscribed, subungual discoloration that may ulcerate, destroying the nail apparatus and penetrating the phalangeal bone. On histopathology, it is characterized by small cysts filled with eosinophilic keratin devoid of a granular layer and lined by atypical squamous epithelium accompanied by solid nests and strands of atypical keratinocytes within the dermis.11 When a cystic component and clear cells predominate, the designation of malignant proliferating onycholemmal cyst has been applied. Its infiltrative growth pattern with destruction of the underlying bone makes it an important entity to exclude when considering the differential diagnosis of tumors of the nail bed.

Subungual melanomas comprise only 1% to 3% of malignant melanomas and 85% are initially misdiagnosed due to their rarity and nonspecific variable presentation. Aside from clinical evidence of Hutchinson sign in the early stages in almost all cases, accurate diagnosis of subungual melanoma and differentiation from SOCs relies on histopathology. A biopsy is necessary to make the diagnosis, but even microscopic findings may be nonspecific during the early stages.

Conclusion

We report a case of a 23-year-old woman with horizontal ridging and tenderness of the right great toenail associated with pigmentation of 5 years’ duration due to an SOC. The etiology of these subungual cysts, with or without nail abnormalities, still remains unclear. Its predilection for the thumbs and great toenails suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Because of the rarity of this entity, there are no guidelines for surgical treatment. Subungual onycholemmal cysts may be an underrecognized and more common entity that must be considered when discussing tumors of the nail unit.

Case Report

A 23-year-old woman presented with a horizontal split along the midline of the right great toenail associated with some tenderness of 2 to 3 months’ duration. Approximately 5 years prior, she noticed a bluish-colored area under the nail that had been steadily increasing in size. She denied a history of trauma, drainage, or bleeding. There was no history of other nail abnormalities. Her medications and personal, family, and social history were noncontributory.

Physical examination of the right great toenail revealed a horizontal split of the nail plate with a bluish hue visible under the nail plate (Figure 1A). The remaining toenails and fingernails were normal. A punch biopsy of the nail bed was performed with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of subungual melanoma versus melanocytic nevus versus cyst (Figure 1B). Nail plate avulsion revealed a blackened nail bed dotted with areas of bluish color and a red friable nodule present focally. Upon further inspection, extension was apparent into the distal matrix.

Histopathologic examination revealed a cystic structure with an epithelial lining mostly reminiscent of an isthmus catagen cyst admixed with the presence of both an intermittent focal granular layer and an eosinophilic cuticle surrounding pink laminated keratin, most consistent with a diagnosis of subungual onycholemmal cyst (SOC)(Figure 2). A reexcision was performed with removal of half of the nail bed, including a portion of the distal matrix extending inferiorly to the bone. Variably sized, epithelium-lined, keratin-filled cystic structures emanated from the nail bed epithelium. There were foci of hemorrhage and granulation tissue secondary to cyst rupture (Figure 3). The defect healed by secondary intention. No clinical evidence of recurrence was seen at 6-month follow-up.

Subungual onycholemmal cysts, also known as subungual epidermoid cysts or subungual epidermoid inclusions, are rare and distinctive nail abnormalities occurring in the dermis of the nail bed. We present a case of an SOC in a toenail mimicking subungual malignant melanoma.

Originally described by Samman1 in 1959, SOCs were attributed to trauma to the nail with resultant implantation of the epidermis into the deeper tissue. Lewin2,3 examined 90 postmortem fingernail and nail bed samples and found 8 subungual epidermoid cysts associated with clubbing of the fingernails. He postulated that the early pathogenesis of clubbing involved dermal fibroblast proliferation in the nail bed, leading to sequestration of nail bed epithelium into the dermis with resultant cyst formation. Microscopic subungual cysts also were identified in normal-appearing nails without evidence of trauma, thought to have arisen from the tips of the nail bed rete ridges by a process of bulbous proliferation rather than sequestration. These findings in normal nails suggest that SOCs may represent a more common entity than previously recognized.

It is imperative to recognize the presence of nail unit tumors early because of the risk for permanent nail plate dystrophy and the possibility of a malignant tumor.4,5 Subungual onycholemmal cysts may present with a wide spectrum of clinical findings including marked subungual hyperkeratosis, onychodystrophy, ridging, nail bed pigmentation, clubbing, thickening, or less often a normal-appearing nail. Based on reported cases, several trends are evident. Although nail dystrophy is most often asymptomatic, pain is not uncommon.5,6 It most commonly involves single digits, predominantly thumbs and great toenails.7,8 This predilection suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Of note, trauma to the nail may occur years before the development of the lesions or it may not be recalled at all.

Diagnosis requires a degree of clinical suspicion and a nail bed biopsy with partial or total nail plate avulsion to visualize the pathologic portion of the nail bed. Because surgical intervention may lead to the implantation of epithelium, recurrences after nail biopsy or excision may occur.

In contrast to epidermal inclusion cysts arising in the skin, most SOCs do not have a granular layer.9 Hair and nails represent analogous differentiation products of the ectoderm. The nail matrix is homologous to portions of the hair matrix, while the nail bed epithelium is comparable to the outer root sheath of the hair follicle.7 Subungual onycholemmal cysts originate from the nail bed epithelium, which keratinizes in the absence of a granular layer, similar to the follicular isthmus outer root sheath. Thus, SOCs are comparable to the outer root sheath–derived isthmus-catagen cysts because of their abrupt central keratinization.8

Subungual onycholemmal cysts also must be distinguished from slowly growing malignant tumors of the nail bed epithelium, referred to as onycholemmal carcinomas by Alessi et al.10 This entity characteristically presents in elderly patients as a slowly growing, circumscribed, subungual discoloration that may ulcerate, destroying the nail apparatus and penetrating the phalangeal bone. On histopathology, it is characterized by small cysts filled with eosinophilic keratin devoid of a granular layer and lined by atypical squamous epithelium accompanied by solid nests and strands of atypical keratinocytes within the dermis.11 When a cystic component and clear cells predominate, the designation of malignant proliferating onycholemmal cyst has been applied. Its infiltrative growth pattern with destruction of the underlying bone makes it an important entity to exclude when considering the differential diagnosis of tumors of the nail bed.

Subungual melanomas comprise only 1% to 3% of malignant melanomas and 85% are initially misdiagnosed due to their rarity and nonspecific variable presentation. Aside from clinical evidence of Hutchinson sign in the early stages in almost all cases, accurate diagnosis of subungual melanoma and differentiation from SOCs relies on histopathology. A biopsy is necessary to make the diagnosis, but even microscopic findings may be nonspecific during the early stages.

Conclusion

We report a case of a 23-year-old woman with horizontal ridging and tenderness of the right great toenail associated with pigmentation of 5 years’ duration due to an SOC. The etiology of these subungual cysts, with or without nail abnormalities, still remains unclear. Its predilection for the thumbs and great toenails suggests that trauma or other local factors may be involved in its pathogenesis. Because of the rarity of this entity, there are no guidelines for surgical treatment. Subungual onycholemmal cysts may be an underrecognized and more common entity that must be considered when discussing tumors of the nail unit.

- Samman PD. The human toe nail. its genesis and blood supply. Br J Dermatol. 1959;71:296-302.

- Lewin K. The normal fingernail. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:421-430.

- Lewin K. Subungual epidermoid inclusions. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:671-675.

- Dominguez-Cherit J, Chanussot-Deprez C, Maria-Sarti H, et al. Nail unit tumors: a study of 234 patients in the dermatology department of the “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital in Mexico City. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1363-1371.

- Sáez-de-Ocariz MM, Domínguez-Cherit J, García-Corona C. Subungual epidermoid cysts. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:524-526.

- Molly DO, Herbert K. Subungual epidermoid cyst. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:345.

- Telang GH, Jellinek N. Multiple calcified subungual epidermoid inclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:336-339.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A. Subungual epidermoid inclusions: report of 8 cases. Dermatologica. 1989;178:209-212.

- Takiyoshi N, Nakano H, Matsuzaki T, et al. An eclipse in the subungual space: a diagnostic sign for a subungual epidermal cyst? Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:962-963.

- Alessi E, Coggi A, Gianotti R, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:397-402.

- Inaoki M, Makino E, Adachi M, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:577-580.

- Samman PD. The human toe nail. its genesis and blood supply. Br J Dermatol. 1959;71:296-302.

- Lewin K. The normal fingernail. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:421-430.

- Lewin K. Subungual epidermoid inclusions. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:671-675.

- Dominguez-Cherit J, Chanussot-Deprez C, Maria-Sarti H, et al. Nail unit tumors: a study of 234 patients in the dermatology department of the “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital in Mexico City. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1363-1371.

- Sáez-de-Ocariz MM, Domínguez-Cherit J, García-Corona C. Subungual epidermoid cysts. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:524-526.

- Molly DO, Herbert K. Subungual epidermoid cyst. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:345.

- Telang GH, Jellinek N. Multiple calcified subungual epidermoid inclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:336-339.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A. Subungual epidermoid inclusions: report of 8 cases. Dermatologica. 1989;178:209-212.

- Takiyoshi N, Nakano H, Matsuzaki T, et al. An eclipse in the subungual space: a diagnostic sign for a subungual epidermal cyst? Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:962-963.

- Alessi E, Coggi A, Gianotti R, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:397-402.

- Inaoki M, Makino E, Adachi M, et al. Onycholemmal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:577-580.

Practice Points

- Trauma to the nail may occur years before the development of subungual onycholemmal cysts or it may not be recalled at all.

- Diagnosis requires a degree of clinical suspicion and a nail bed biopsy.

- Subungual onycholemmal cysts must be distinguished from slowly growing malignant tumors of the nail bed epithelium.

Circumscribed Nodule in a Renal Transplant Patient

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

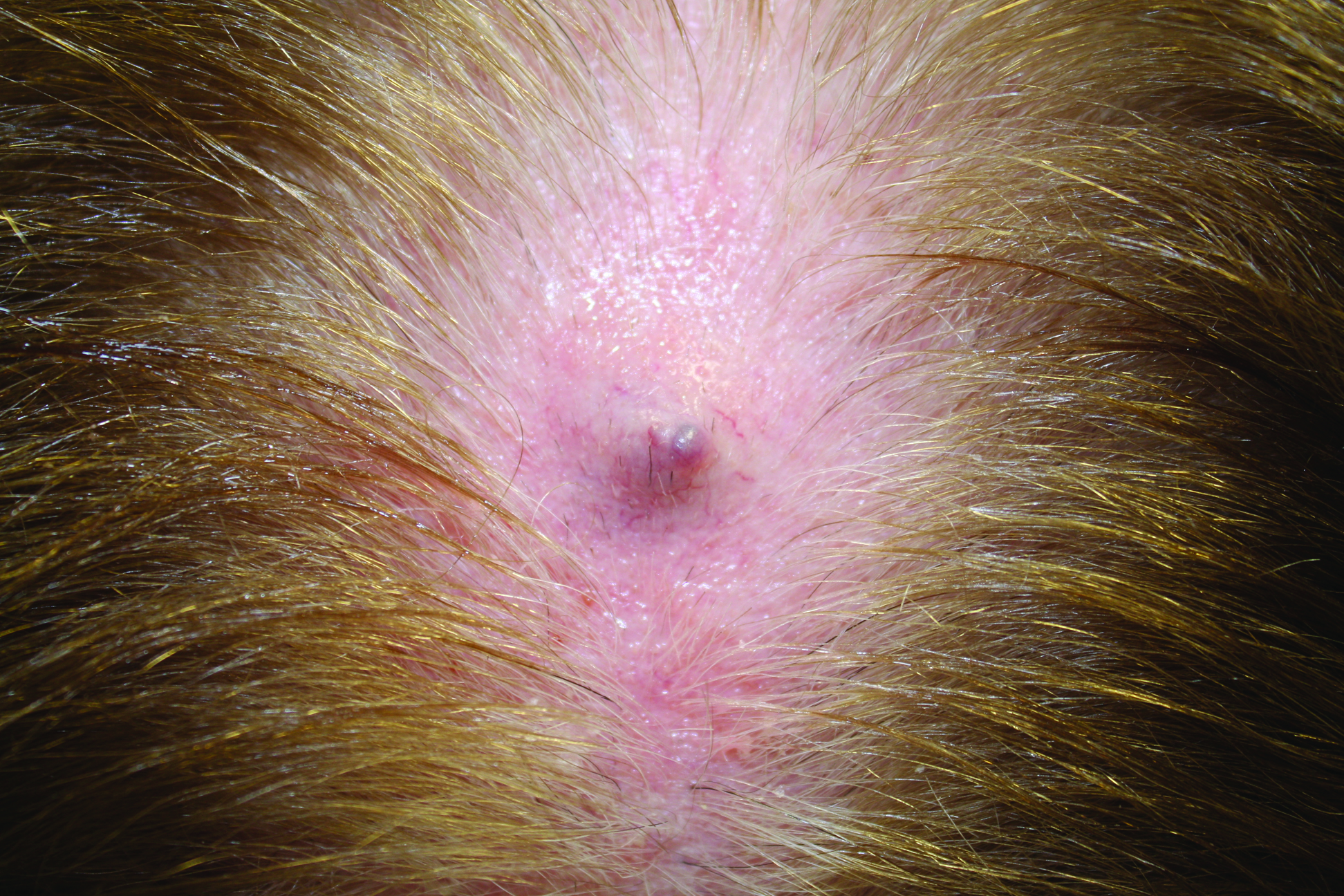

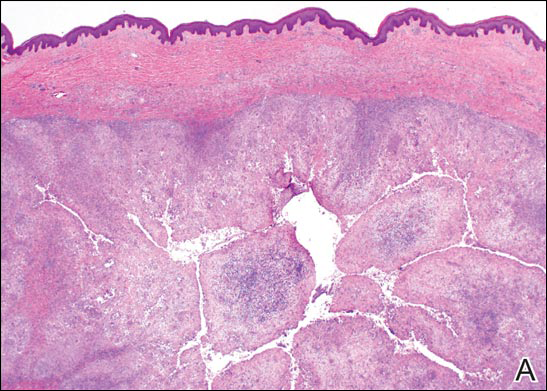

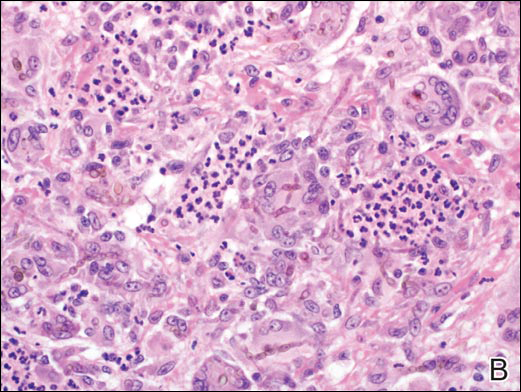

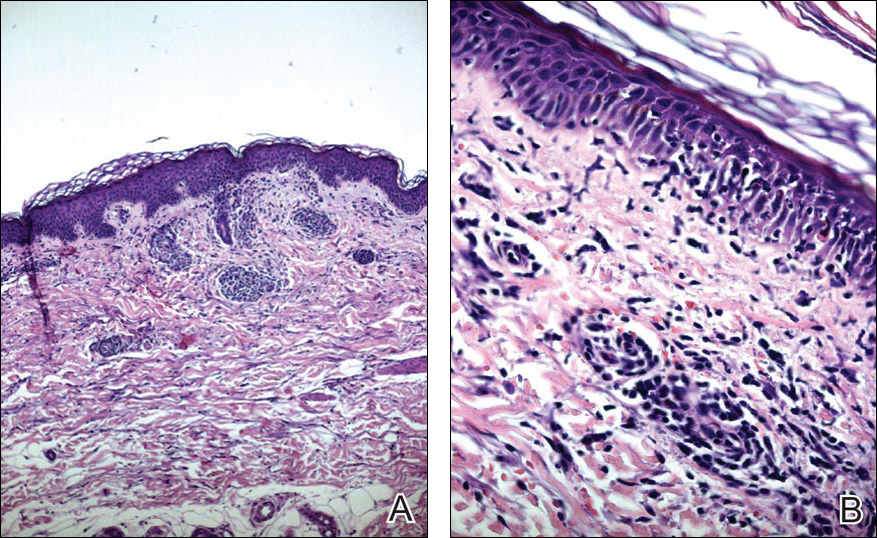

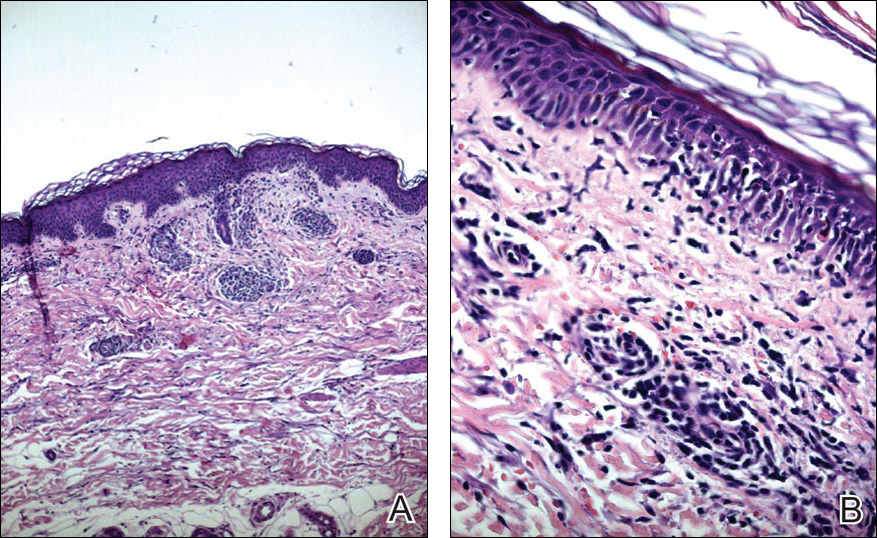

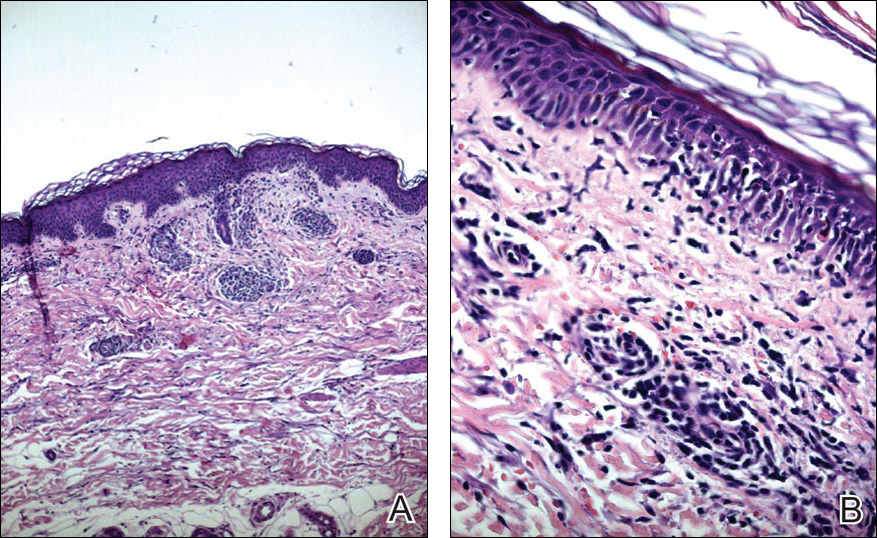

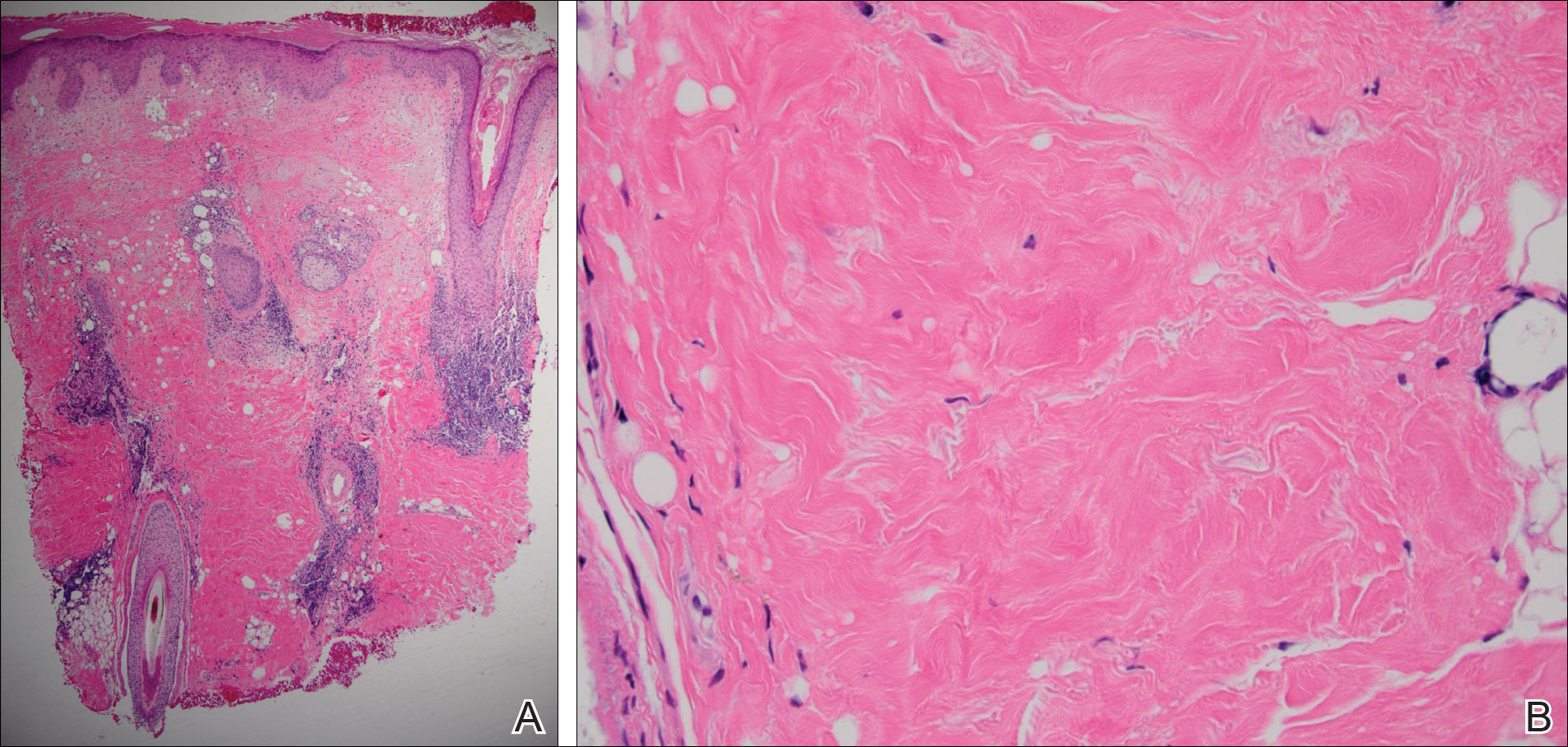

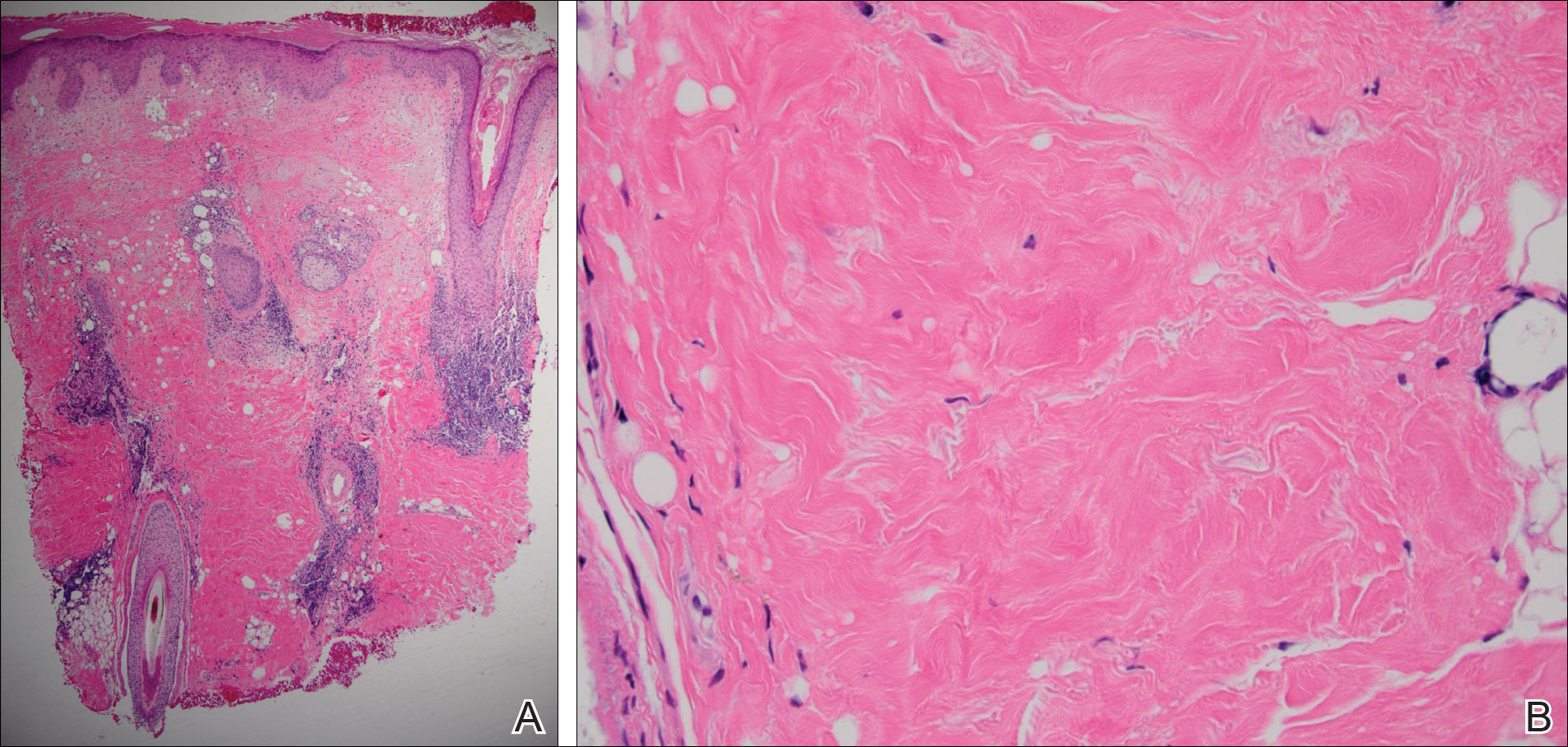

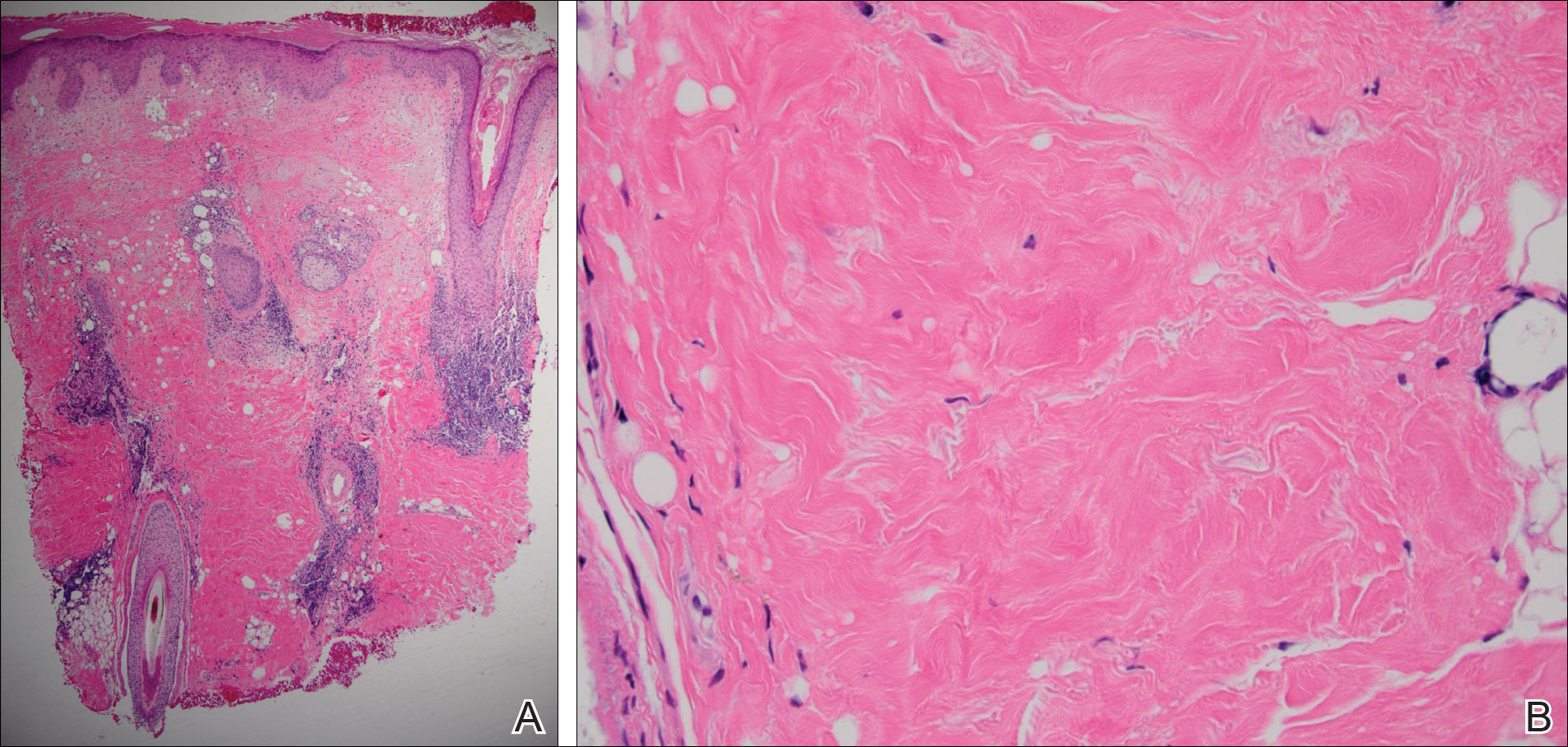

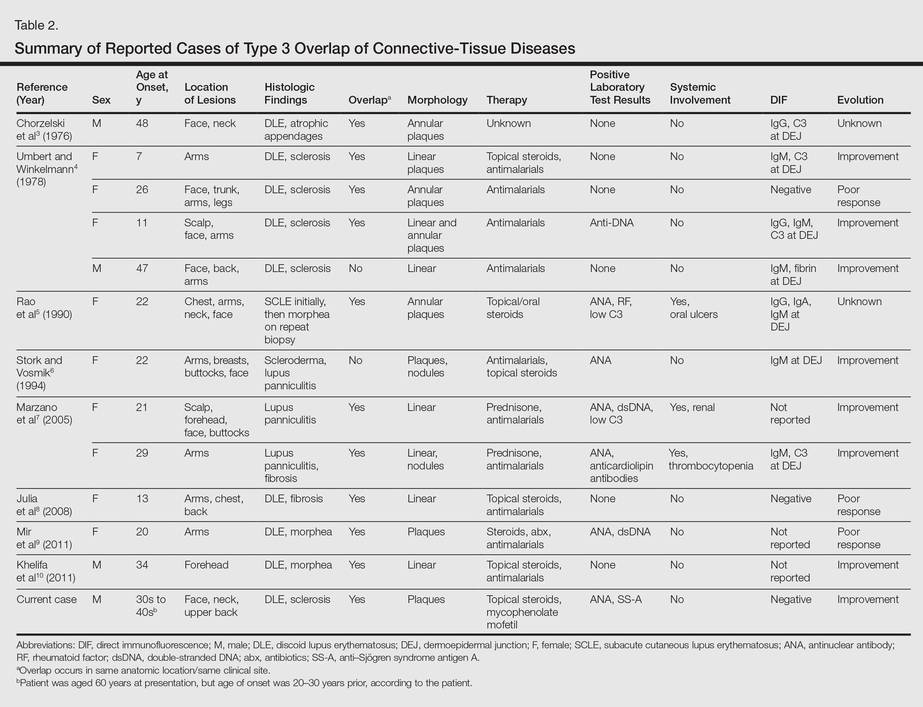

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

A 63-year-old man on immunosuppressive therapy following renal transplantation 5 years prior presented with a nontender circumscribed nodule above the left knee of 6 months’ duration. The patient denied any trauma or injury to the site.

Primary Cutaneous Dermal Mucinosis on Herpes Zoster Scars

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

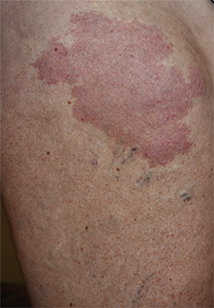

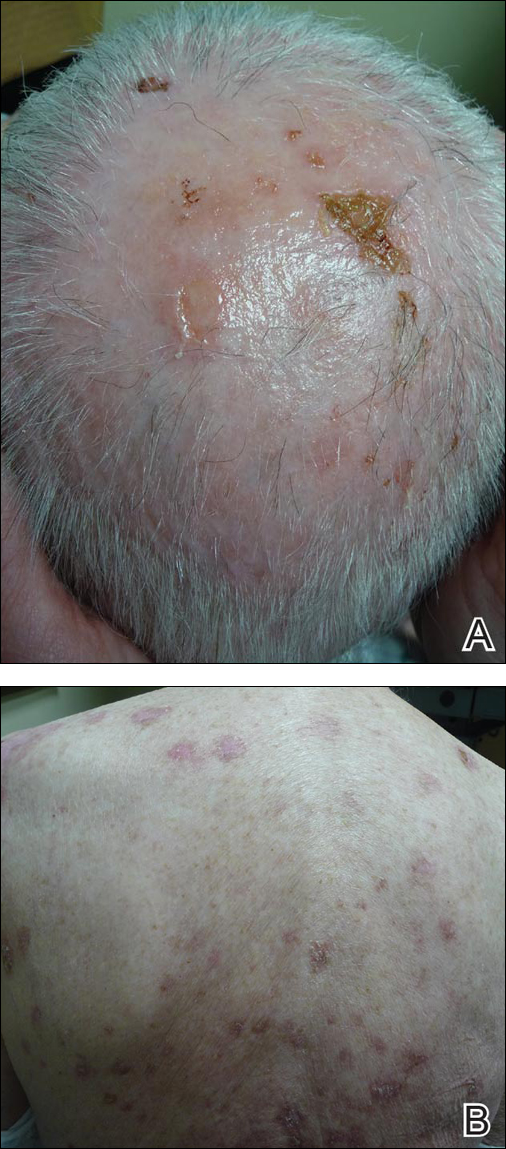

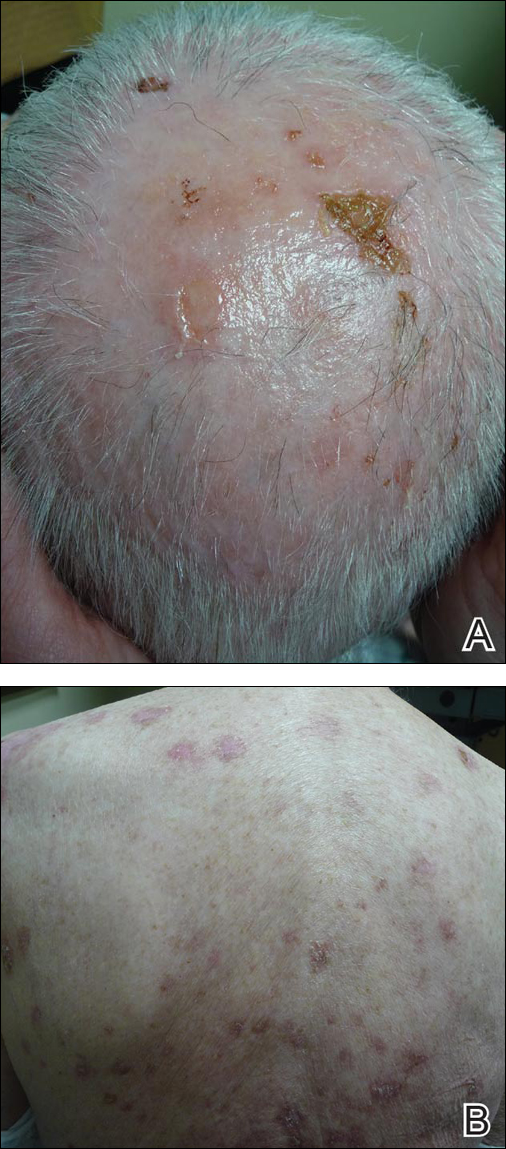

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

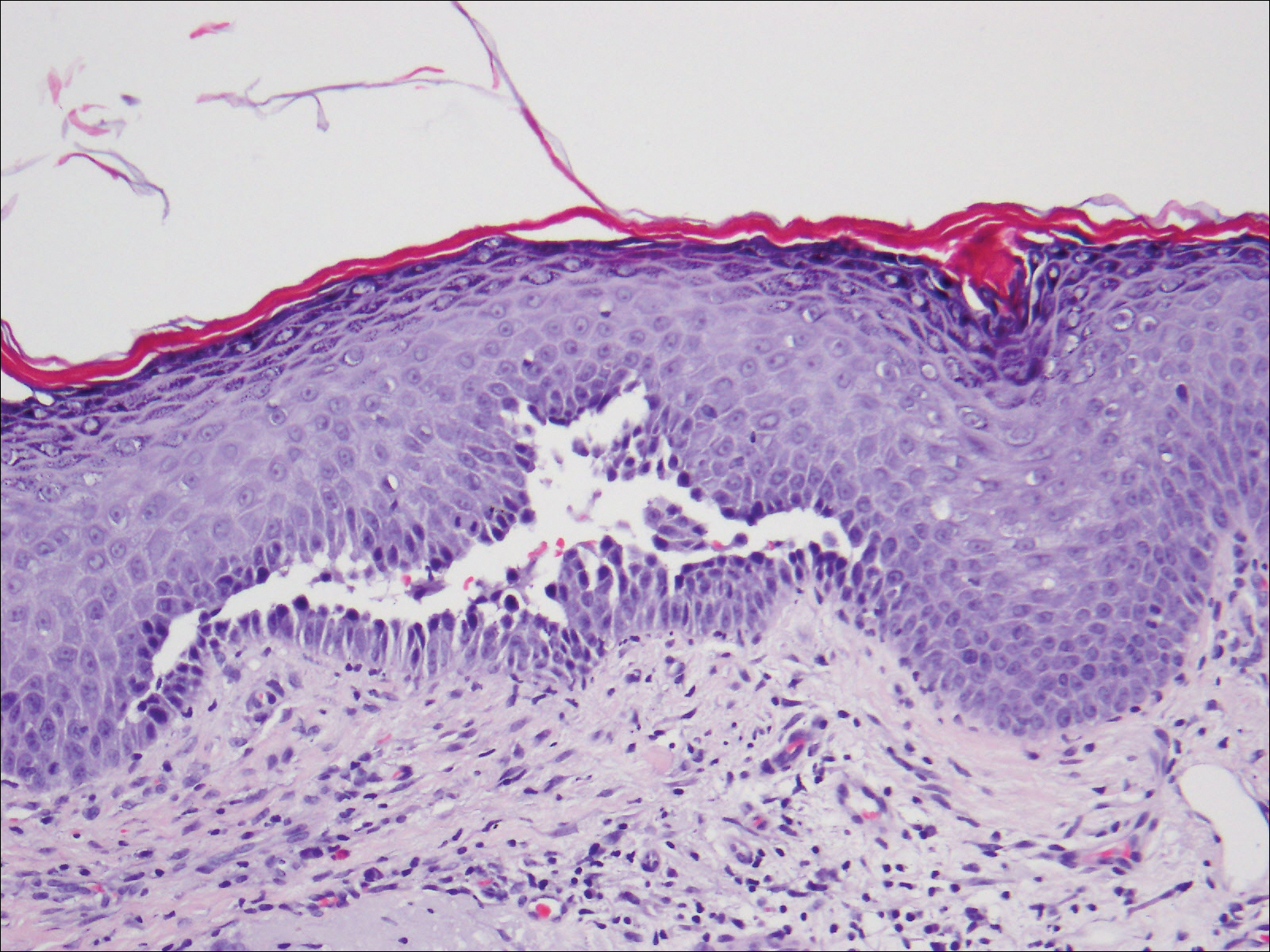

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.

Several benign and malignant disorders may occur at sites of resolved HZ lesions, including granulomatous dermatitis,6 granuloma annulare,7 fungal granuloma,8 fungal folliculitis,9 psoriasis,10 morphea,11 lichen sclerosus,12 Kaposi sarcoma,13 the lichenoid variant of chronic graft-versus-host disease,14 cutaneous sarcoidosis,15 granulomatous folliculitis,16 comedones,17 furuncles,18 erythema annulare centrifugum,19 eosinophilic dermatosis,20 cutaneous pseudolymphoma,21 granulomatous vasculitis,22 Rosai-Dorfman disease,12 xanthomatous changes,23 tuberculoid granulomas,24 acneform eruption,25 lichen planus,26 acquired reactive perforating collagenosis,27 lymphoma,28 leukemia,29 angiosarcoma,30 basal cell carcinoma,31 squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinoma.32 The interval between the acute HZ episode and presentation of the second disease is quite variable, ranging from days to several months. Postzoster isotopic response has been described in individuals with varying degrees of immune response, affecting both immunocompetent12 and immunocompromised patients.14 There is no predilection for age, sex, or race. It also seems that antiviral treatment during the active episode does not prevent the development of secondary reactions.Kim et al33 reported a 59-year-old woman who developed flesh-colored or erythematous papules on HZ scars over the area of the left T1 and T2 dermatomes 1 week after the active viral process. Histopathologic study demonstrated deposition of mucin between collagen bundles in the dermis. The authors established the diagnosis of secondary cutaneous mucinosis as an isotopic response.33 Nevertheless, we believe that based on the aforementioned classification of cutaneous mucinosis,2 both this case and our case are better considered as primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis, as the mucin deposition in the dermis was the main histologic finding resulting in a distinctive cutaneous disorder. In the case reported by Kim et al,33 a possible relationship between cutaneous mucinosis and postherpetic neuralgia was suggested based on the slow regression of skin lesions in accordance with the improvement of the neuralgic pain; however, our patient did not have postherpetic neuralgia and the lesions persisted unchanged several months after the acute HZ episode. In the literature, there are reports of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis associated with altered thyroid function34; autoimmune connective tissue diseases, mostly lupus erythematosus35; monoclonal gammopathy36; and human immunodeficiency virus infection,37 but these possibilities were ruled out in our patient by pertinent laboratory studies.

The pathogenesis of the postherpetic isotopic response remains unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. Some authors have suggested that postzoster dermatoses may represent isomorphic response of Köbner phenomenon.13,15 Although isomorphic and isotopic responses share some similarities, these terms describe 2 different phenomena: the first refers to the appearance of the same cutaneous disorder at a different site favored by trauma, while the second manifests a new and unrelated disease at the same location.38 Local anatomic changes such as altered microcirculation, collagen rearrangement, and an imperfect skin barrier may promote a prolonged local inflammatory response. Moreover, the destruction of nerve fibers by the varicella-zoster virus may indirectly influence the local immune system through the release of specific neuropeptides in the skin.39 It has been speculated that some secondary reactions may be the result of type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions40 to viral antigens or to tissue antigens modified by the virus, inducing either immune hypersensitivity or local immune suppression.41 Some authors have documented the presence of varicella-zoster DNA within early postzoster lesions6,7 by using polymerase chain reaction in early lesions but not in late-stage and residual lesions.12,22 Nikkels et al42 studied early granulomatous lesions by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques and concluded that major viral envelope glycoproteins (glycoproteins I and II) rather than complete viral particles could be responsible for delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. All these findings suggest that secondary reactions presenting on HZ scars are mainly the result of atypical immune reactions to local antigenic stimuli.

The pathogenesis of our case is unknown. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that varicella-zoster virus may induce fibroblastic proliferation and mucin production on HZ scars; however, if HZ is a frequent process and the virus may induce mucin production, then focal dermal mucinosis in an HZ scar should be a common finding. In our patient, there was no associated disease favoring the development of the cutaneous mucinosis. These localized variants of primary cutaneous mucinosis usually do not require therapy, and a wait-and-see approach is recommended. Topical applications of corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus, as well as oral isotretinoin, may have some benefit,43 but spontaneous resolution may occur.44 In our patient, topical corticosteroids were applied 2 months following initial presentation without any benefit and the cutaneous lesions gradually improved without any therapy during the subsequent 6 months. Focal dermal mucinosis should be added to the list of cutaneous reactions that may develop in HZ scars.

- Truhan AP, Roenigk HH Jr. The cutaneous mucinoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1-18.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:257-267.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. BMJ. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Ruocco E. Genital warts at the site of healed herpes progenitalis: the isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:705-706.

- Serfling U, Penneys NS, Zhu WY, et al. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in granulomatous skin lesions following herpes zoster. a study by the polymerase chain reaction. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:28-33.

- Gibney MD, Nahass GT, Leonardi CL. Cutaneous reactions following herpes zoster infections: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:504-509.

- Huang CW, Tu ME, Wu YH, et al. Isotopic response of fungal granuloma following facial herpes zoster infections-report of three cases. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1141-1145.

- Tüzün Y, Işçimen A, Göksügür N, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: Trichophyton rubrum folliculitis appearing on a herpes zoster scar. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:766-768.

- Allegue F, Fachal C, Romo M, et al. Psoriasis at the site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:576-578.

- Forschner A, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Morphea with features of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus at the site of a herpes zoster scar: another case of an isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:524-525.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Niedt GW, Prioleau PG. Kaposi’s sarcoma occurring in a dermatome previously involved by herpes zoster. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:448-451.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Cecchi R, Giomi A. Scar sarcoidosis following herpes zoster. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:280-282.

- Fernández-Redondo V, Amrouni B, Varela E, et al. Granulomatous folliculitis at sites of herpes zoster scars: Wolf’s isotopic response. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:628-630.

- Sanchez-Salas MP. Appearance of comedones at the site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:633-634.

- Ghorpade A. Wolf’s isotopic response—furuncles at the site of healed herpes zoster in an Indian male. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:105-107.

- Lee HW, Lee DK, Rhee DY, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum following herpes zoster infection: Wolf’s isotopic response? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1241-1243.

- Mitsuhashi Y, Kondo S. Post-zoster eosinophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:465-466.

- Roo E, Villegas C, Lopez-Bran E, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:661-663.

- Langenberg A, Yen TS, LeBoit PE. Granulomatous vasculitis occurring after cutaneous herpes zoster despite absence of viral genome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:429-433.

- Weidman F, Boston LN. Generalized xanthoma tuberosum with xantomathous changes in fresh scars of intercurrent zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1937;59:793-822.

- Olalquiaga J, Minaño R, Barrio J. Granuloma tuberculoide post-herpético en un paciente con leucemia linfocítica crónica. Med Cutan ILA. 1995;23:113-115.

- Stubbings JM, Goodfield MJ. An unusual distribution of an acneiform rash due to herpes zoster infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:92-93.

- Shemer A, Weiss G, Trau H. Wolf’s isotopic response: a case of zosteriform lichen planus on the site of healed herpes zoster. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:445-447.

- Bang SW, Kim YK, Whang KU. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: unilateral umbilicated papules along the lesions of herpes zoster. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:778-779.

- Paydaş S, Sahin B, Yavuz S, et al. Lymphomatous skin infiltration at the site of previous varicella zoster virus infection in a patient with T cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:229-232.

- Cerroni L, Kerl H. Cutaneous localization of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia at the site of varicella/herpes virus eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:1022.

- Hudson CP, Hanno R, Callen JP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma in a site of healed herpes zoster. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:404-407.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Visceral lesions in herpes zoster. Br Med J. 1957;1:678-681.

- Caroti A. Metastasi cutanee di a adenocarcinoma papillifero ovarico in sede di herpes zoster. Chron Dermatol. 1987;18:769-773.

- Kim MB, Jwa SW, Ko HC, et al. A case of secondary cutaneous mucinosis following herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:212-214.

- Burman KD, McKinley-Grant L. Dermatologic aspects of thyroid disease. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:247-255.

- Shekari AM, Ghiasi M, Ghasemi E, et al. Papulonodular mucinosis indicating systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:558-560.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37-43.

- Rongioletti F, Ghigliotti G, De Marchi R, et al. Cutaneous mucinoses and HIV infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1077-1080.

- Krahl D, Hartschuh W, Tilgen W. Granuloma annulare perforans in herpes zoster scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:859-862.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- Fisher G, Jaworski R. Granuloma formation in herpes zoster scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1261-1263.

- Ruocco V, Grimaldi Filioli F. La risposta isotopica post-erpetica: possibile sequela di un locus minoris resistentiae acquisito. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1999;134:547-552.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, et al. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;5:530-532.

- Kwon OS, Moon SE, Kim JA, et al. Lichen myxodematosus with rapid spontaneous regression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:295-296.

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

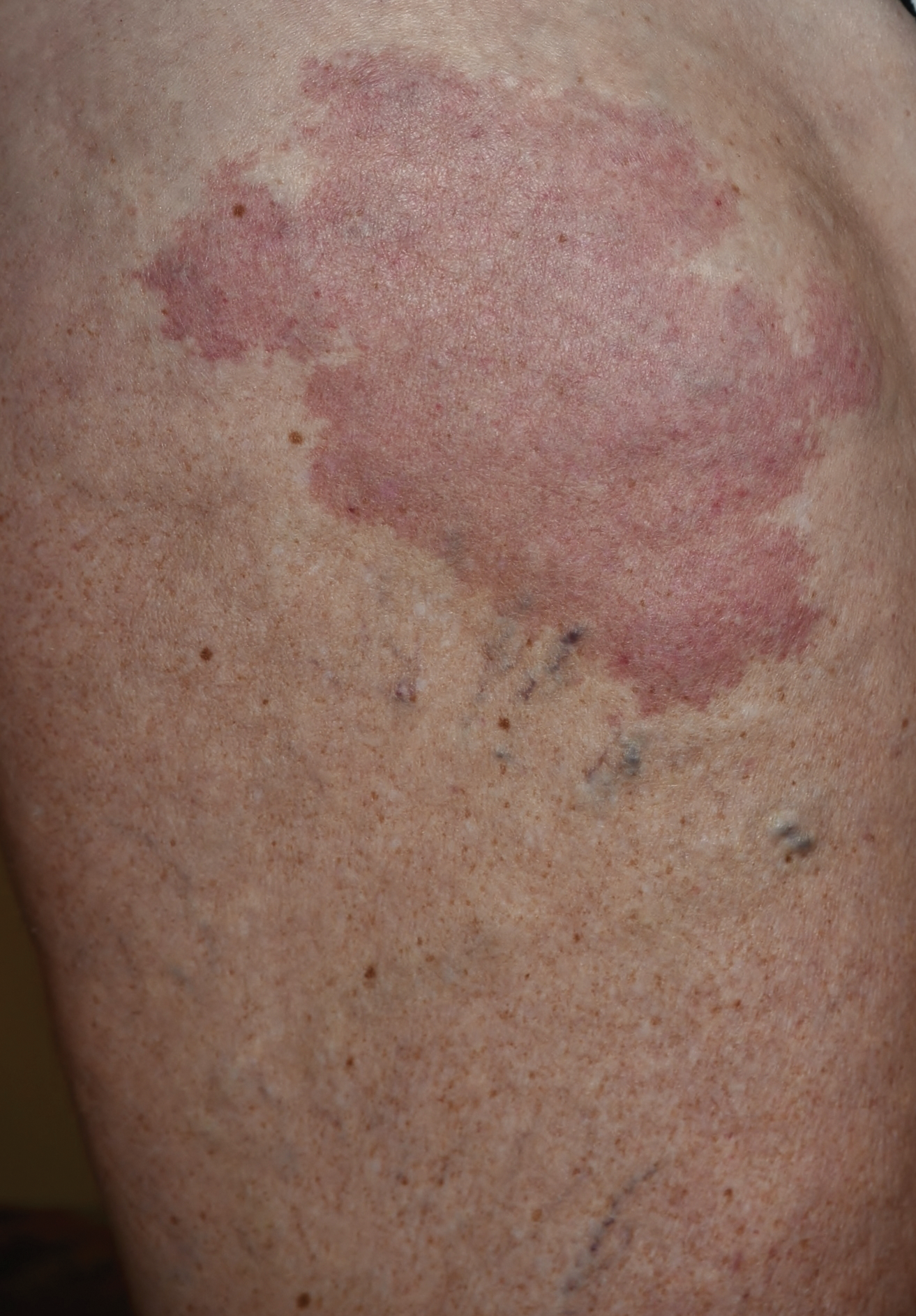

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.

Several benign and malignant disorders may occur at sites of resolved HZ lesions, including granulomatous dermatitis,6 granuloma annulare,7 fungal granuloma,8 fungal folliculitis,9 psoriasis,10 morphea,11 lichen sclerosus,12 Kaposi sarcoma,13 the lichenoid variant of chronic graft-versus-host disease,14 cutaneous sarcoidosis,15 granulomatous folliculitis,16 comedones,17 furuncles,18 erythema annulare centrifugum,19 eosinophilic dermatosis,20 cutaneous pseudolymphoma,21 granulomatous vasculitis,22 Rosai-Dorfman disease,12 xanthomatous changes,23 tuberculoid granulomas,24 acneform eruption,25 lichen planus,26 acquired reactive perforating collagenosis,27 lymphoma,28 leukemia,29 angiosarcoma,30 basal cell carcinoma,31 squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinoma.32 The interval between the acute HZ episode and presentation of the second disease is quite variable, ranging from days to several months. Postzoster isotopic response has been described in individuals with varying degrees of immune response, affecting both immunocompetent12 and immunocompromised patients.14 There is no predilection for age, sex, or race. It also seems that antiviral treatment during the active episode does not prevent the development of secondary reactions.Kim et al33 reported a 59-year-old woman who developed flesh-colored or erythematous papules on HZ scars over the area of the left T1 and T2 dermatomes 1 week after the active viral process. Histopathologic study demonstrated deposition of mucin between collagen bundles in the dermis. The authors established the diagnosis of secondary cutaneous mucinosis as an isotopic response.33 Nevertheless, we believe that based on the aforementioned classification of cutaneous mucinosis,2 both this case and our case are better considered as primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis, as the mucin deposition in the dermis was the main histologic finding resulting in a distinctive cutaneous disorder. In the case reported by Kim et al,33 a possible relationship between cutaneous mucinosis and postherpetic neuralgia was suggested based on the slow regression of skin lesions in accordance with the improvement of the neuralgic pain; however, our patient did not have postherpetic neuralgia and the lesions persisted unchanged several months after the acute HZ episode. In the literature, there are reports of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis associated with altered thyroid function34; autoimmune connective tissue diseases, mostly lupus erythematosus35; monoclonal gammopathy36; and human immunodeficiency virus infection,37 but these possibilities were ruled out in our patient by pertinent laboratory studies.

The pathogenesis of the postherpetic isotopic response remains unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. Some authors have suggested that postzoster dermatoses may represent isomorphic response of Köbner phenomenon.13,15 Although isomorphic and isotopic responses share some similarities, these terms describe 2 different phenomena: the first refers to the appearance of the same cutaneous disorder at a different site favored by trauma, while the second manifests a new and unrelated disease at the same location.38 Local anatomic changes such as altered microcirculation, collagen rearrangement, and an imperfect skin barrier may promote a prolonged local inflammatory response. Moreover, the destruction of nerve fibers by the varicella-zoster virus may indirectly influence the local immune system through the release of specific neuropeptides in the skin.39 It has been speculated that some secondary reactions may be the result of type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions40 to viral antigens or to tissue antigens modified by the virus, inducing either immune hypersensitivity or local immune suppression.41 Some authors have documented the presence of varicella-zoster DNA within early postzoster lesions6,7 by using polymerase chain reaction in early lesions but not in late-stage and residual lesions.12,22 Nikkels et al42 studied early granulomatous lesions by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques and concluded that major viral envelope glycoproteins (glycoproteins I and II) rather than complete viral particles could be responsible for delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. All these findings suggest that secondary reactions presenting on HZ scars are mainly the result of atypical immune reactions to local antigenic stimuli.

The pathogenesis of our case is unknown. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that varicella-zoster virus may induce fibroblastic proliferation and mucin production on HZ scars; however, if HZ is a frequent process and the virus may induce mucin production, then focal dermal mucinosis in an HZ scar should be a common finding. In our patient, there was no associated disease favoring the development of the cutaneous mucinosis. These localized variants of primary cutaneous mucinosis usually do not require therapy, and a wait-and-see approach is recommended. Topical applications of corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus, as well as oral isotretinoin, may have some benefit,43 but spontaneous resolution may occur.44 In our patient, topical corticosteroids were applied 2 months following initial presentation without any benefit and the cutaneous lesions gradually improved without any therapy during the subsequent 6 months. Focal dermal mucinosis should be added to the list of cutaneous reactions that may develop in HZ scars.

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.