User login

Flesh-Colored Papular Eruption

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

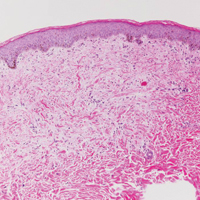

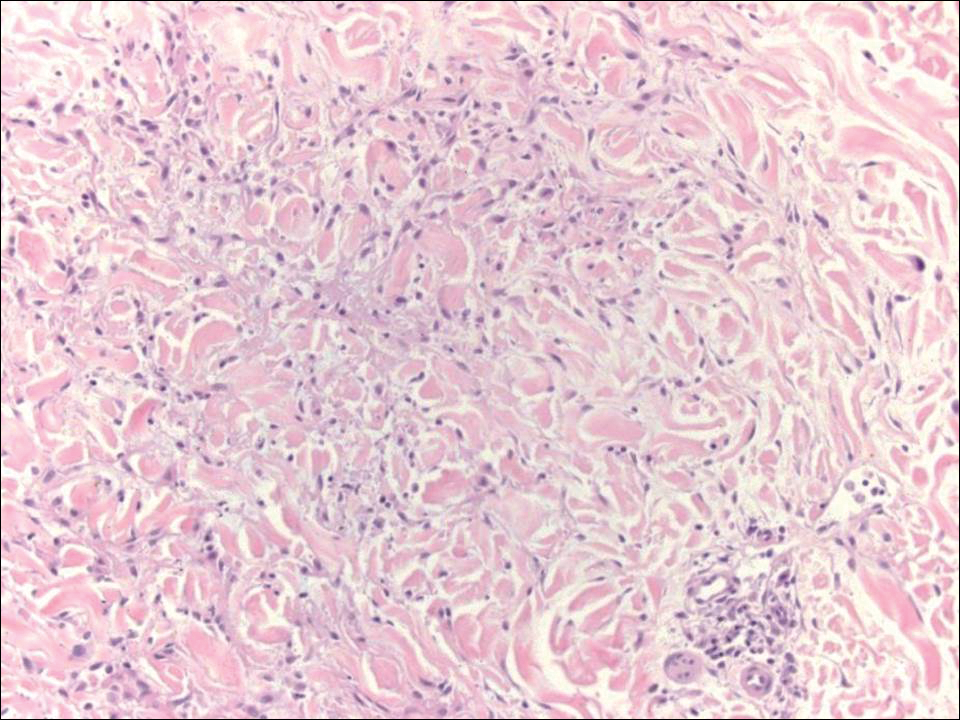

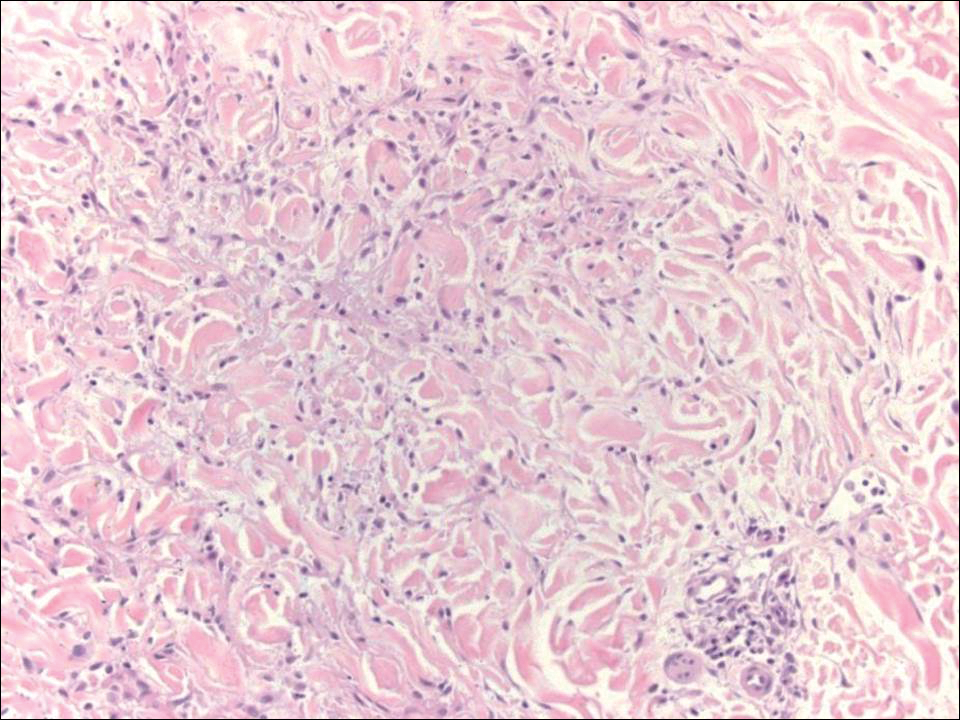

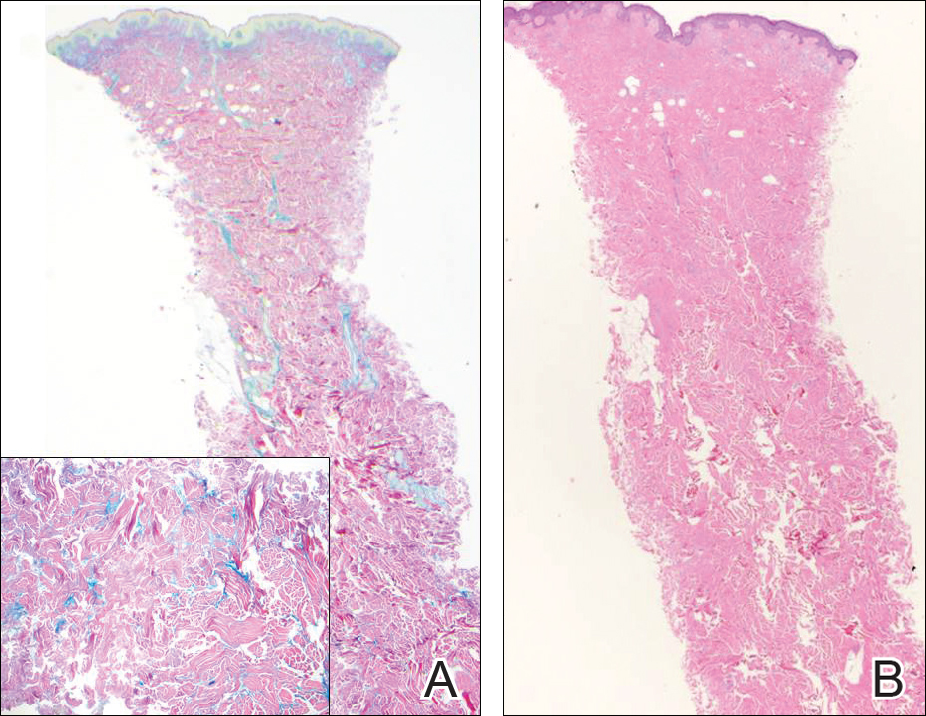

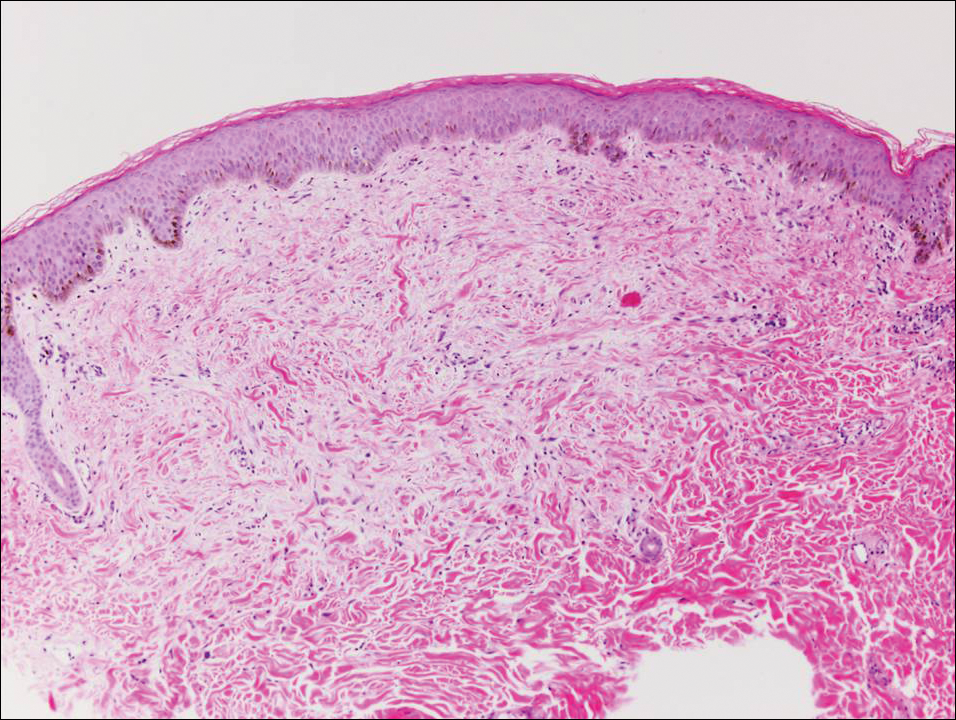

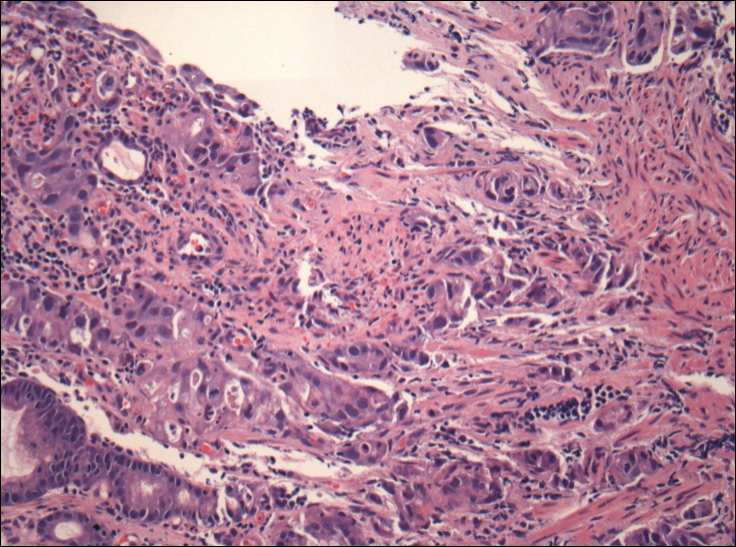

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

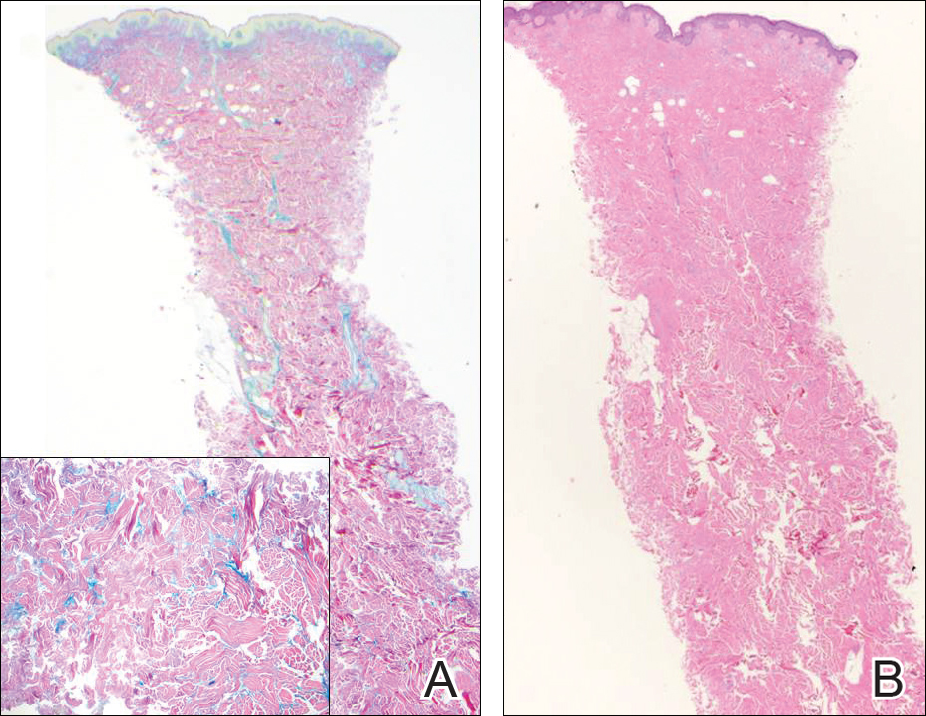

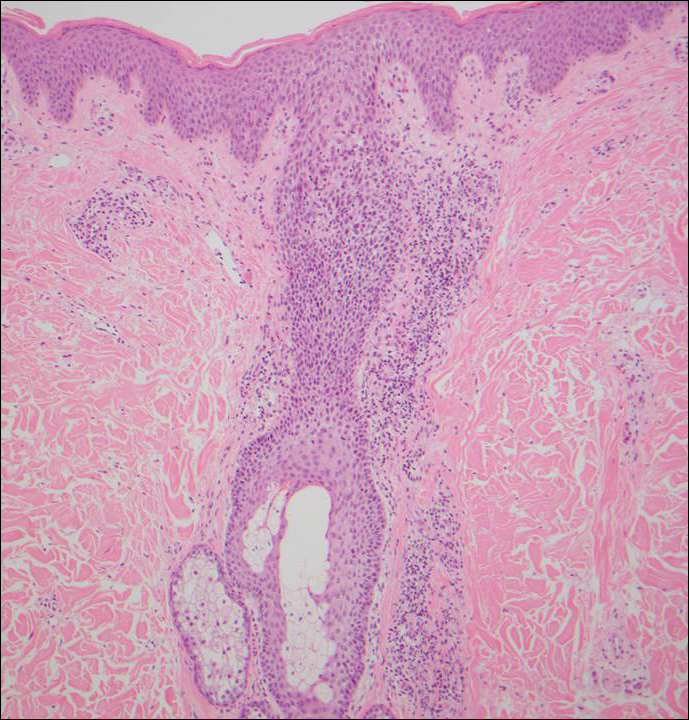

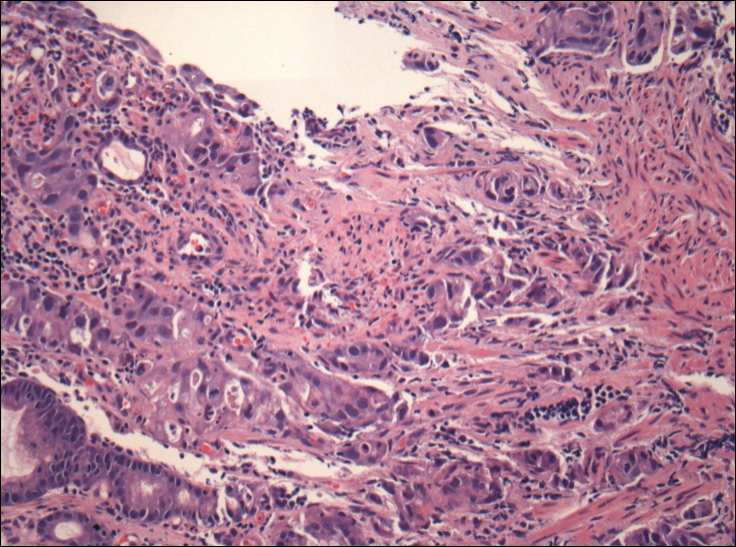

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

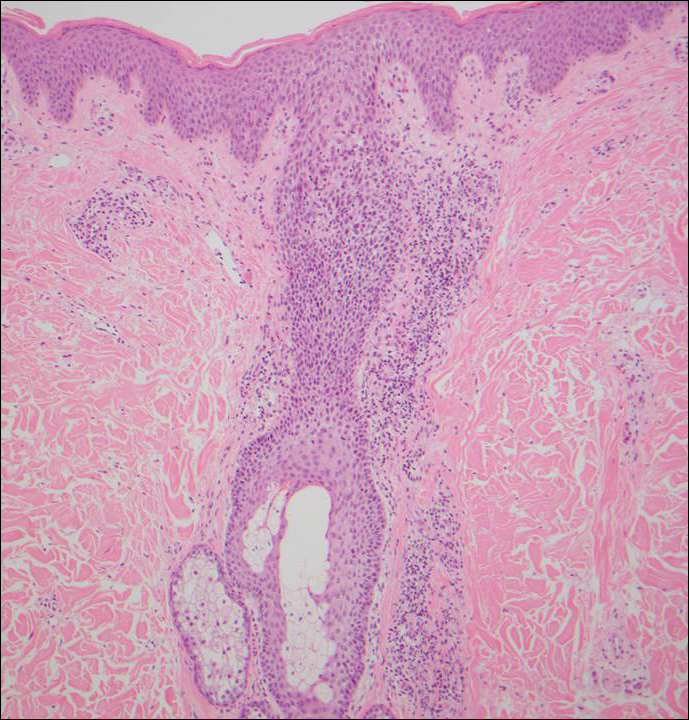

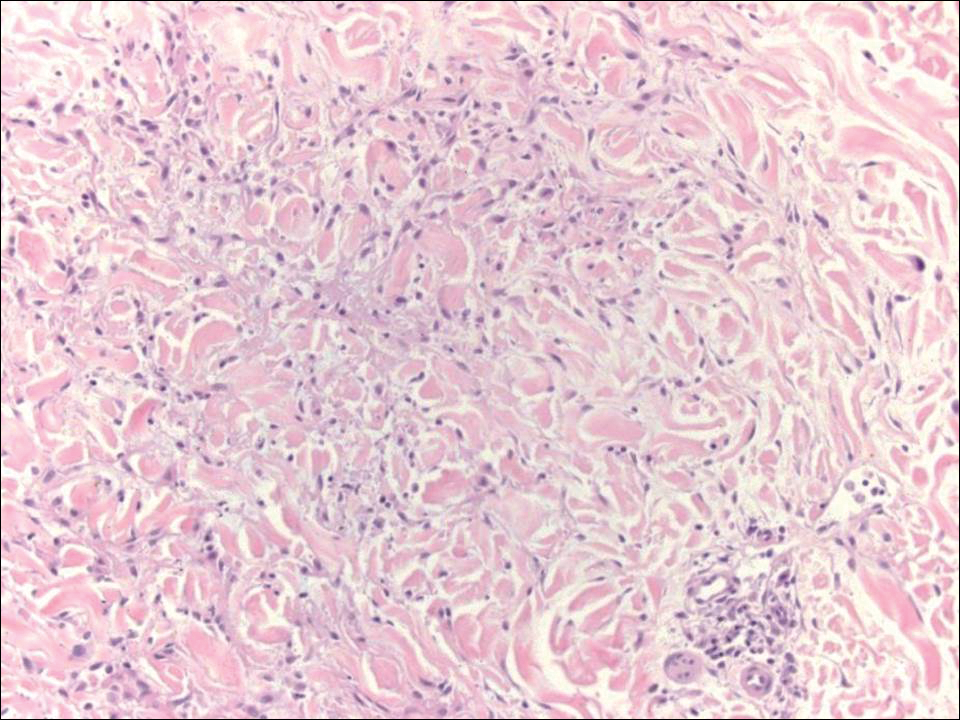

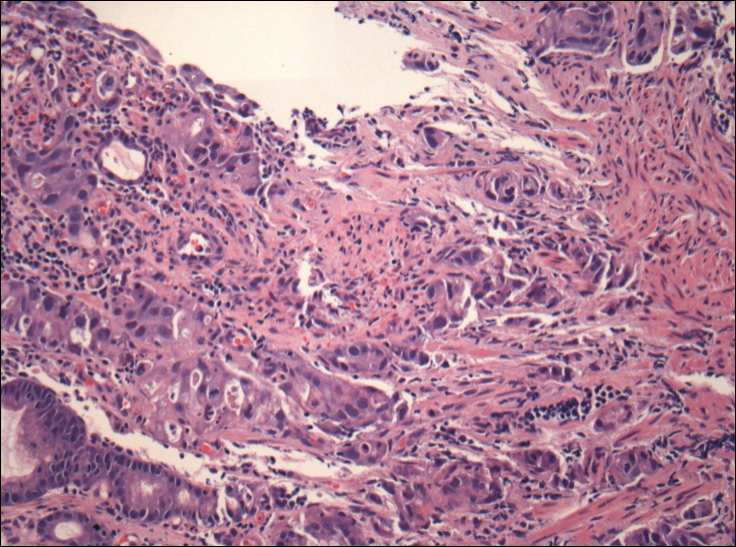

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

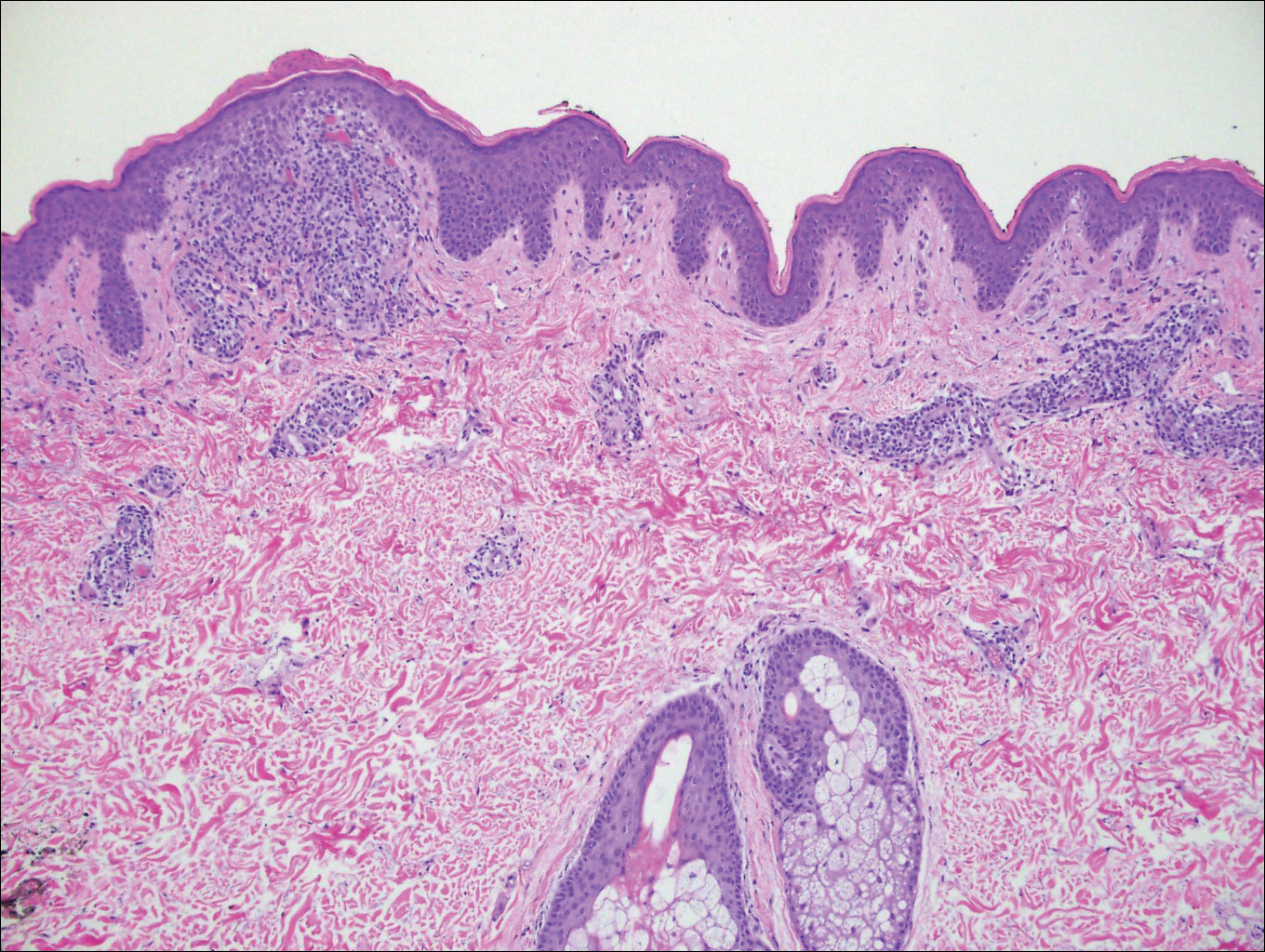

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

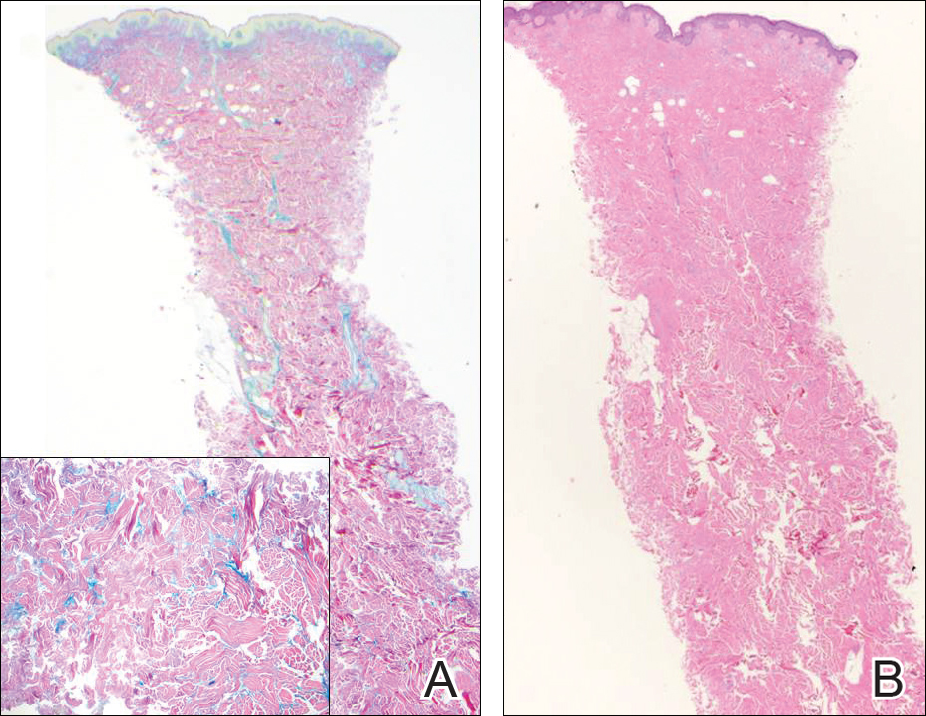

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

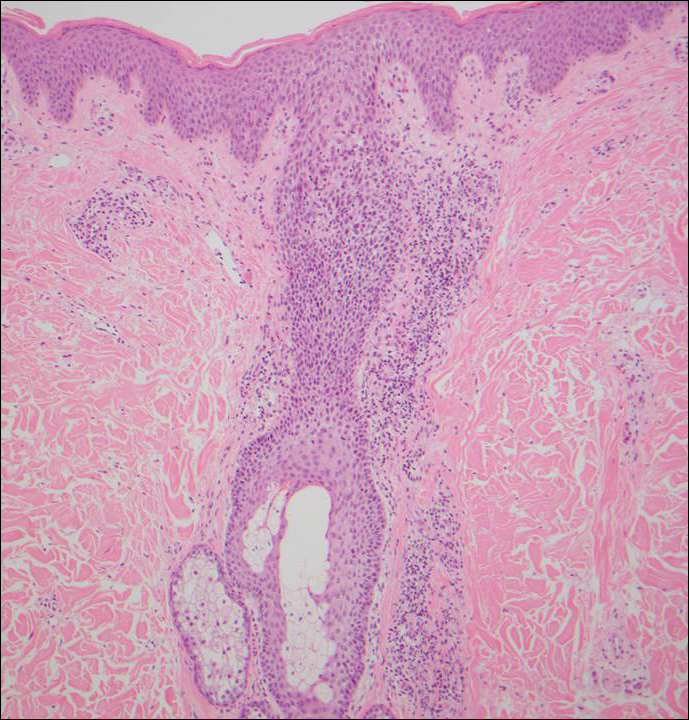

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

A 48-year-old black man presented with a rash of 7 months' duration that started on the face and spread to the body. He had extreme pruritus, increased stiffness in the hands and joints, and paresthesia. Physical examination revealed an eruption of 2- to 4-mm, flesh-colored papules with follicular accentuation on the face, neck, bilateral upper extremities, back, and thighs.

Sarcoidosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Connection Documented in a Case Series of 3 Patients

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

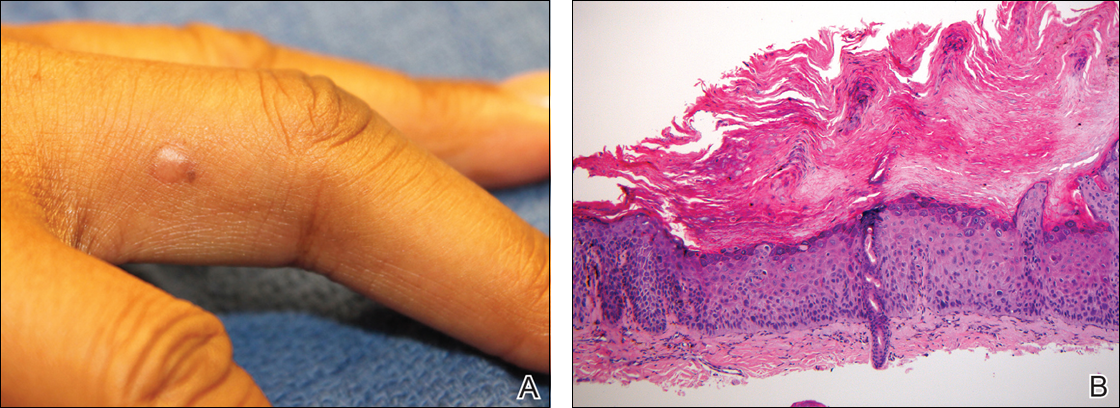

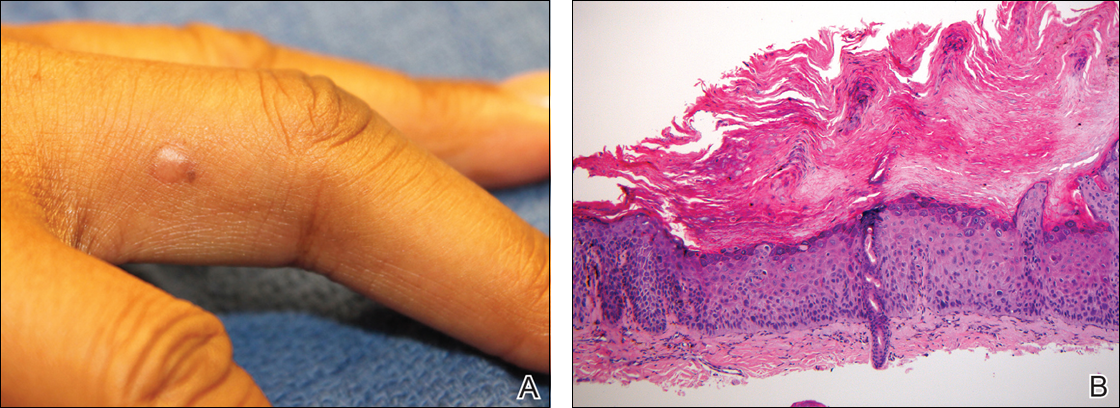

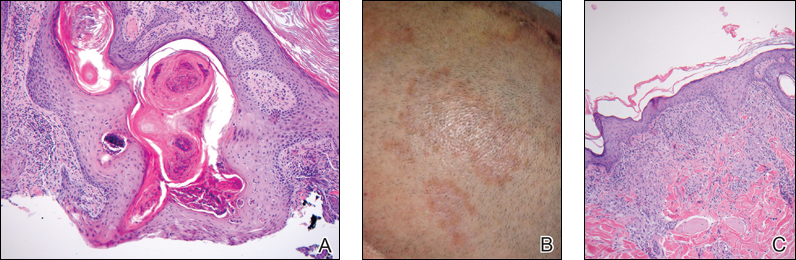

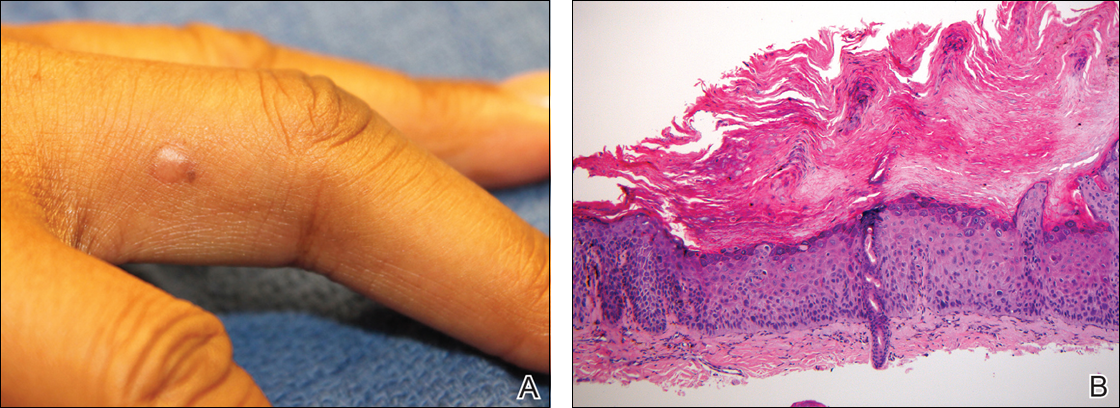

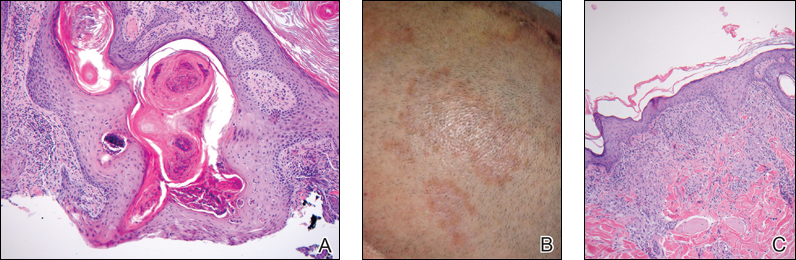

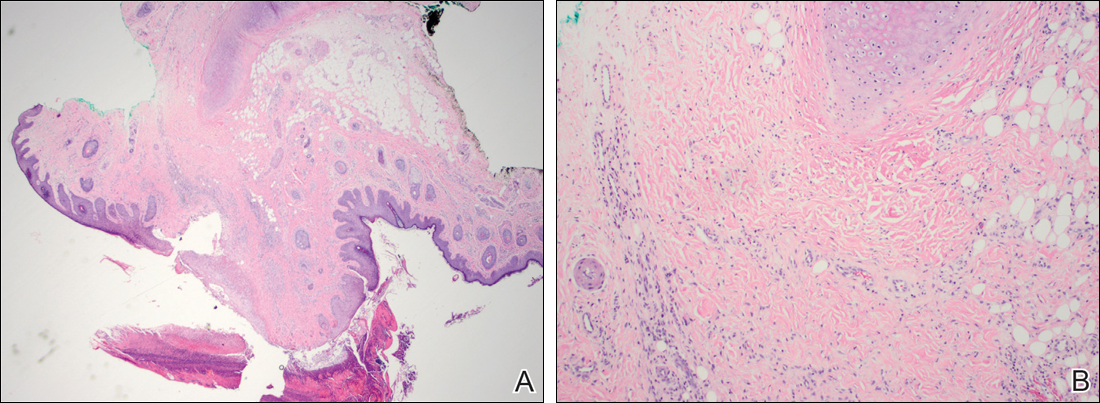

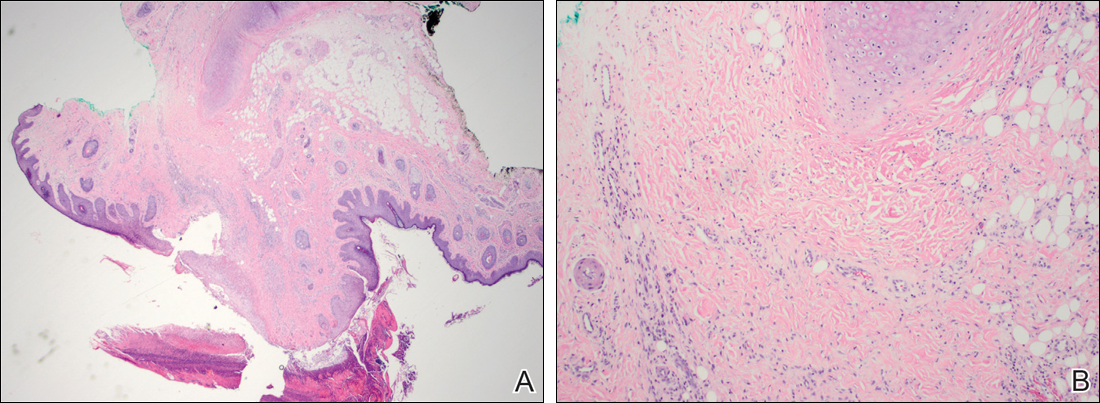

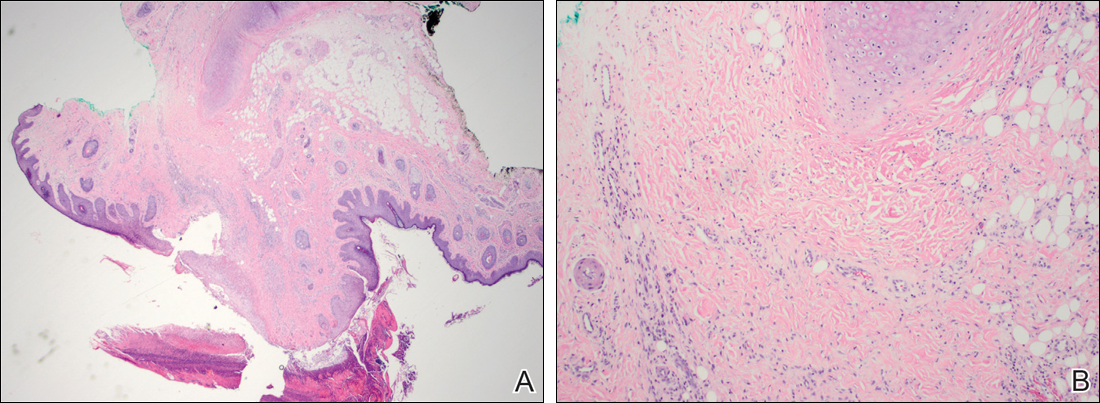

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

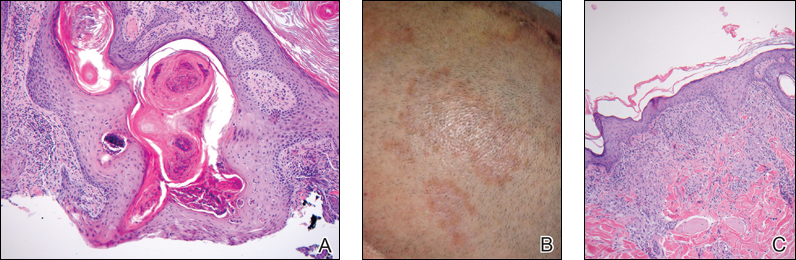

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Practice Points

- There may be an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with sarcoidosis.

- Sarcoidosis may present with multiple morphologies, including verrucous or hyperkeratotic lesions; superficial biopsy of this type of lesion may be mistaken for a squamous cell carcinoma.

- A biopsy diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in a black patient with sarcoidosis should be carefully reviewed for evidence of deeper granulomatous inflammation.

Low-dose IL-2 shows promise for refractory lupus

WASHINGTON – A novel biologic treatment strategy involving subcutaneous low-dose interleukin-2 therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) showed promise in a single-center, combined phase I/IIa trial.

In 12 patients with active and refractory SLE – that is, patients with SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) score of at least 6 who were on at least two different immunosuppressive therapies – low-dose IL-2 treatment led to an effective and cycle-dependent increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among regulatory T cells (Treg). The increase was statistically significant (P less than .001), Jens Humrich, MD, and his colleagues reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

However, a reduction in levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies was not observed, said Dr. Humrich of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Lubeck, Germany.

Treatment was safe; treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and transient, Dr. Humrich noted.

Study subjects received four treatment cycles each, with daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human IL-2 (aldesleukin) at single doses of 0.75, 1.5, or 3.0 million IU on 5 consecutive days. Cycles were separated by a washout period of 9-16 days. Subjects were then followed for 9 weeks.

IL-2 is crucial for the growth and survival of Treg (and thus for the control of autoimmunity). Prior studies demonstrated the significance of acquired IL-2 deficiency and related Treg defects in the pathogenesis of SLE – and that compensation for IL-2 deficiency with low-dose IL-2 can correct these defects, he explained.

In the current study, the primary aim was to show at least a twofold increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among CD3+CD4+Foxp3+CD127lo Treg cells after the fourth treatment cycle vs. baseline, and secondary aims included clinical responses assessed by SLEDAI and changes in serologic and other immunologic parameters, he said.

The findings suggest that low-dose IL-2 therapy can safely and selectively expand the Treg population and decrease disease activity in patients with active and refractory SLE.

“This study provides the basis for larger and placebo-controlled clinical studies aiming to prove the efficacy of this novel biologic treatment strategy,” the investigators concluded.

Dr. Humrich reported having no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A novel biologic treatment strategy involving subcutaneous low-dose interleukin-2 therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) showed promise in a single-center, combined phase I/IIa trial.

In 12 patients with active and refractory SLE – that is, patients with SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) score of at least 6 who were on at least two different immunosuppressive therapies – low-dose IL-2 treatment led to an effective and cycle-dependent increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among regulatory T cells (Treg). The increase was statistically significant (P less than .001), Jens Humrich, MD, and his colleagues reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

However, a reduction in levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies was not observed, said Dr. Humrich of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Lubeck, Germany.

Treatment was safe; treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and transient, Dr. Humrich noted.

Study subjects received four treatment cycles each, with daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human IL-2 (aldesleukin) at single doses of 0.75, 1.5, or 3.0 million IU on 5 consecutive days. Cycles were separated by a washout period of 9-16 days. Subjects were then followed for 9 weeks.

IL-2 is crucial for the growth and survival of Treg (and thus for the control of autoimmunity). Prior studies demonstrated the significance of acquired IL-2 deficiency and related Treg defects in the pathogenesis of SLE – and that compensation for IL-2 deficiency with low-dose IL-2 can correct these defects, he explained.

In the current study, the primary aim was to show at least a twofold increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among CD3+CD4+Foxp3+CD127lo Treg cells after the fourth treatment cycle vs. baseline, and secondary aims included clinical responses assessed by SLEDAI and changes in serologic and other immunologic parameters, he said.

The findings suggest that low-dose IL-2 therapy can safely and selectively expand the Treg population and decrease disease activity in patients with active and refractory SLE.

“This study provides the basis for larger and placebo-controlled clinical studies aiming to prove the efficacy of this novel biologic treatment strategy,” the investigators concluded.

Dr. Humrich reported having no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A novel biologic treatment strategy involving subcutaneous low-dose interleukin-2 therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) showed promise in a single-center, combined phase I/IIa trial.

In 12 patients with active and refractory SLE – that is, patients with SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) score of at least 6 who were on at least two different immunosuppressive therapies – low-dose IL-2 treatment led to an effective and cycle-dependent increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among regulatory T cells (Treg). The increase was statistically significant (P less than .001), Jens Humrich, MD, and his colleagues reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

However, a reduction in levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies was not observed, said Dr. Humrich of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Lubeck, Germany.

Treatment was safe; treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and transient, Dr. Humrich noted.

Study subjects received four treatment cycles each, with daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human IL-2 (aldesleukin) at single doses of 0.75, 1.5, or 3.0 million IU on 5 consecutive days. Cycles were separated by a washout period of 9-16 days. Subjects were then followed for 9 weeks.

IL-2 is crucial for the growth and survival of Treg (and thus for the control of autoimmunity). Prior studies demonstrated the significance of acquired IL-2 deficiency and related Treg defects in the pathogenesis of SLE – and that compensation for IL-2 deficiency with low-dose IL-2 can correct these defects, he explained.

In the current study, the primary aim was to show at least a twofold increase in the percentage of CD25hi cells among CD3+CD4+Foxp3+CD127lo Treg cells after the fourth treatment cycle vs. baseline, and secondary aims included clinical responses assessed by SLEDAI and changes in serologic and other immunologic parameters, he said.

The findings suggest that low-dose IL-2 therapy can safely and selectively expand the Treg population and decrease disease activity in patients with active and refractory SLE.

“This study provides the basis for larger and placebo-controlled clinical studies aiming to prove the efficacy of this novel biologic treatment strategy,” the investigators concluded.

Dr. Humrich reported having no disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A reduction in SLEDAI was seen in 10 patients (83.3%), and a clinical response occurred in 8 (66.7%).

Data source: A combined phase I/IIa trial involving 12 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Humrich reported having no disclosures.

Verrucous Plaque on the Leg

Blastomycosis

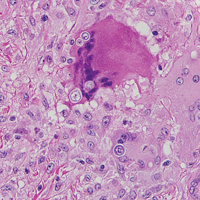

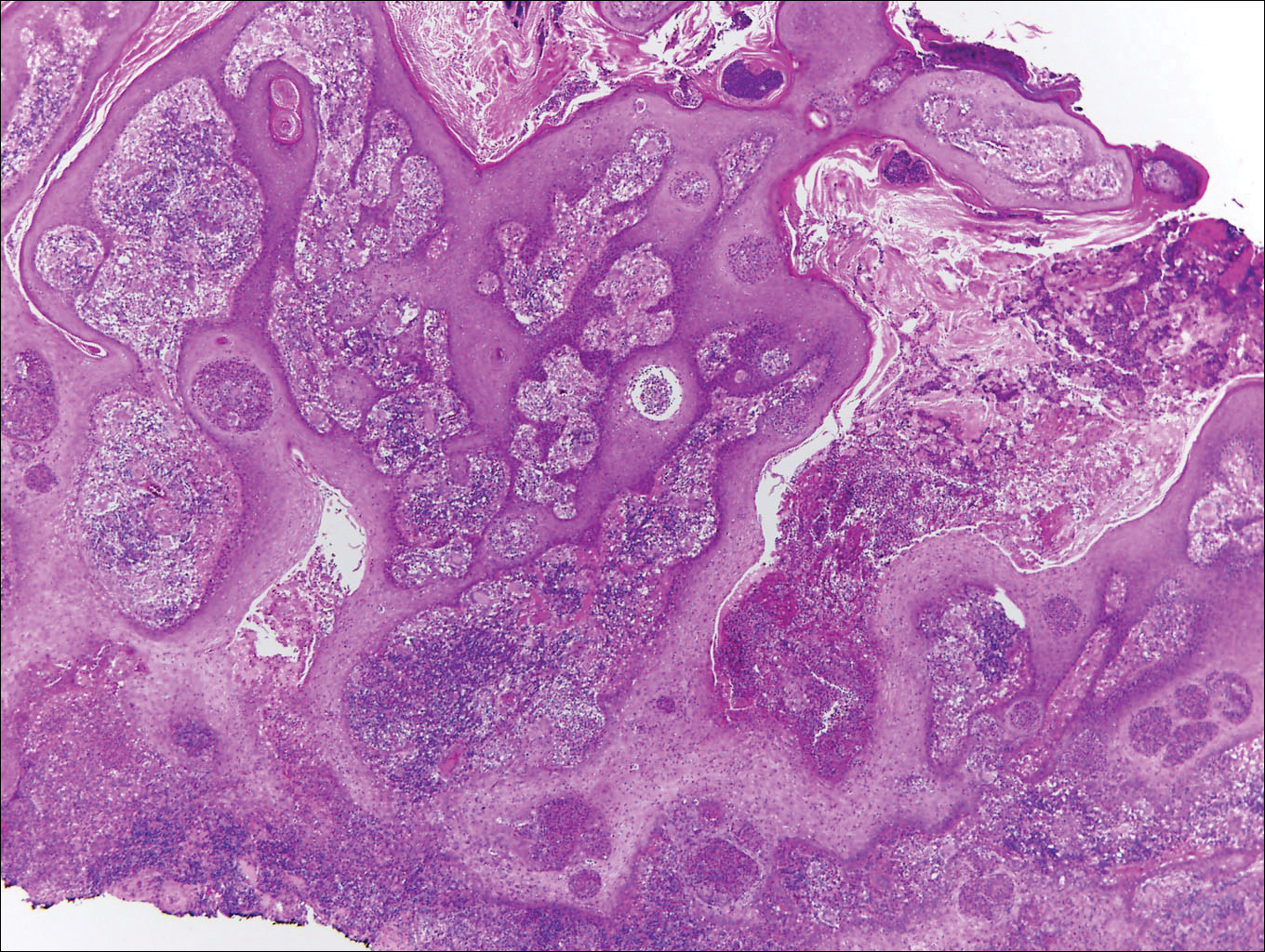

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Aquatic Antagonists: Cutaneous Sea Urchin Spine Injury

Sea urchin injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions near both warm and cold salt water with frequent recreational water activities or fishing. Sea urchins belong to the class Echinoidea with approximately 600 species, of which roughly 80 are poisonous to humans.1,2 When a human comes in contact with a sea urchin, the spines of the sea urchin (made of calcium carbonate) can penetrate the skin and break off from the sea urchin, becoming embedded in the skin. Injuries from sea urchin spines are most commonly seen on the hands and feet, as the likelihood of contact with a sea urchin is greater on these sites. The severity of sea urchin spine injuries can vary widely, from minimal local trauma and pain to arthritis, synovitis, and occasionally systemic illness.1,3 It is important to recognize the wide variety of responses to sea urchin spine injuries and the impact of prompt treatment. Many published reports on injuries from sea urchin spines describe arthritis and synovitis from spines in the joints.1,2,4-6 Fewer reports discuss nonjoint injuries and the dermatologic aspects of sea urchin spine injuries.3,7,8 We pre-sent a case of a patient with a puncture injury from sea urchin spines that resulted in painful granulomas.

Case Report

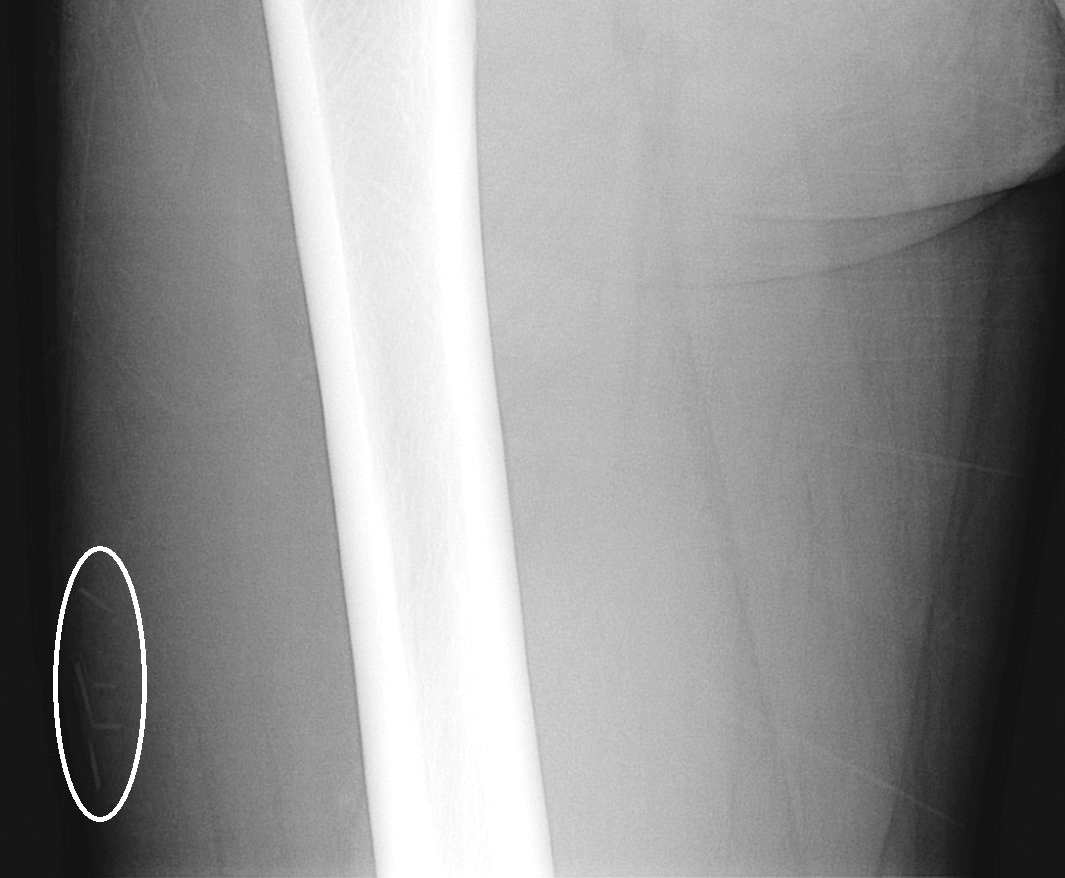

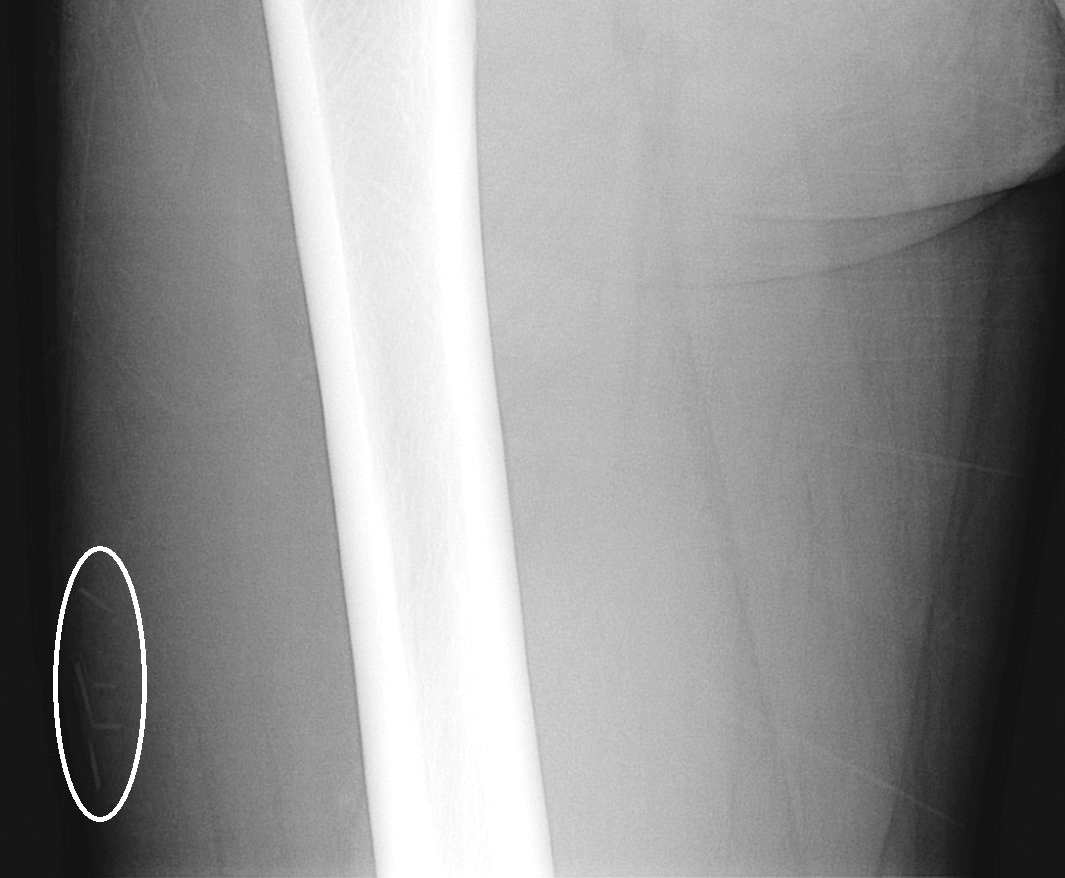

A 29-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to our dermatology clinic by the university student health center due to continued pain in the right thigh. Five weeks prior to presentation to the student health center, the patient had fallen on a sea urchin while snorkeling in Hawaii. Sea urchin spines became lodged in the right thigh, some of which were removed in a local medical clinic in Hawaii. He was given oral antibiotics prior to his return home. A plain film radiograph of the affected area ordered by the student health center showed several punctate and linear densities in the lateral aspect of the right mid thigh (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with sea urchin spines within the superficial soft tissues of the lateral thigh.

At the time of presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient reported sharp intermittent pain localized to the right thigh. The patient denied any fever, chills, or pain in the joints. On physical examination, there were several firm nodules on the right thigh, ranging from 4 to 20 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The nodules were tender to palpation with some surrounding edema. Drainage was not noted. Several scars were visible at sites of the original puncture injuries and removal of the spines.

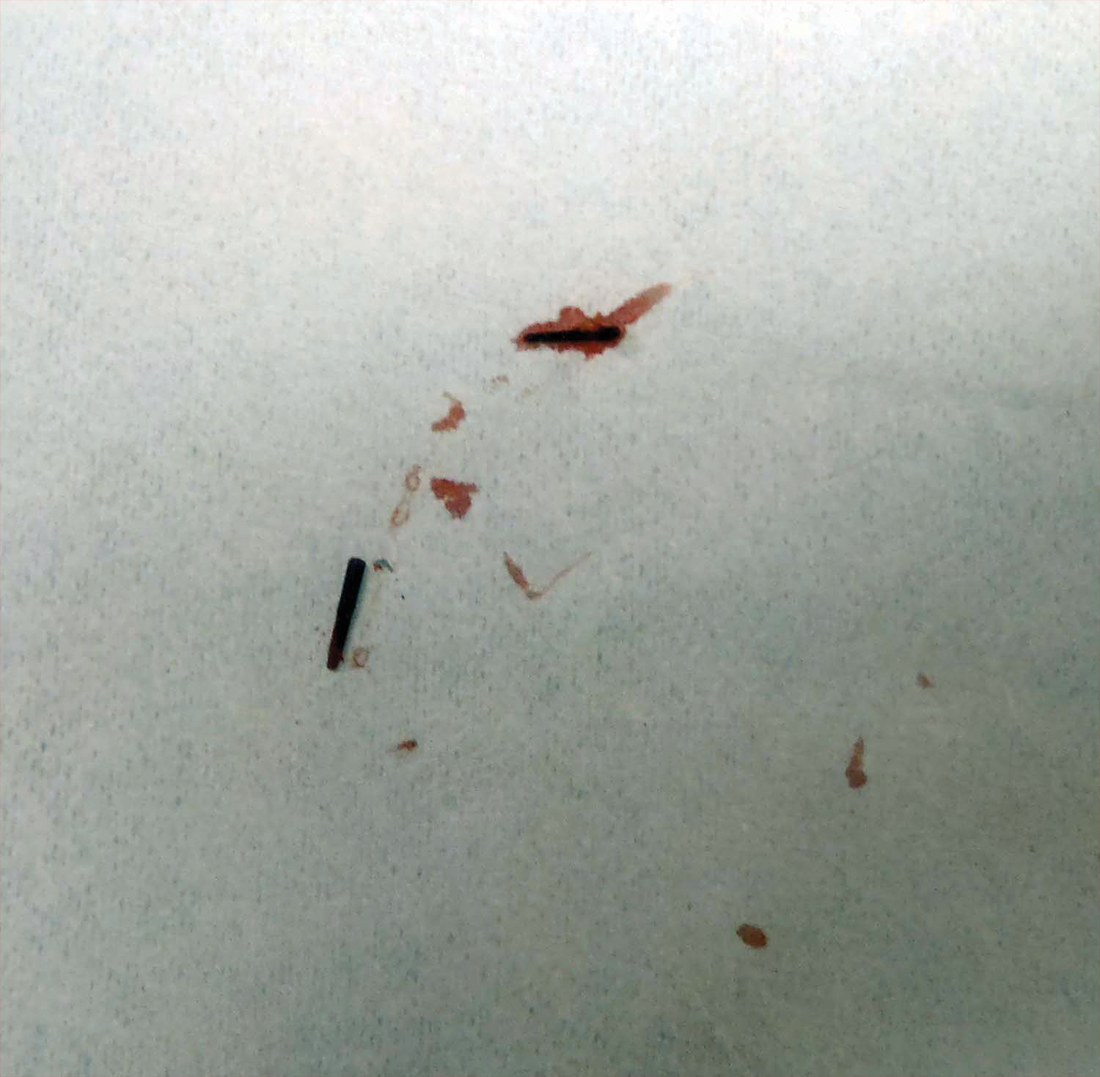

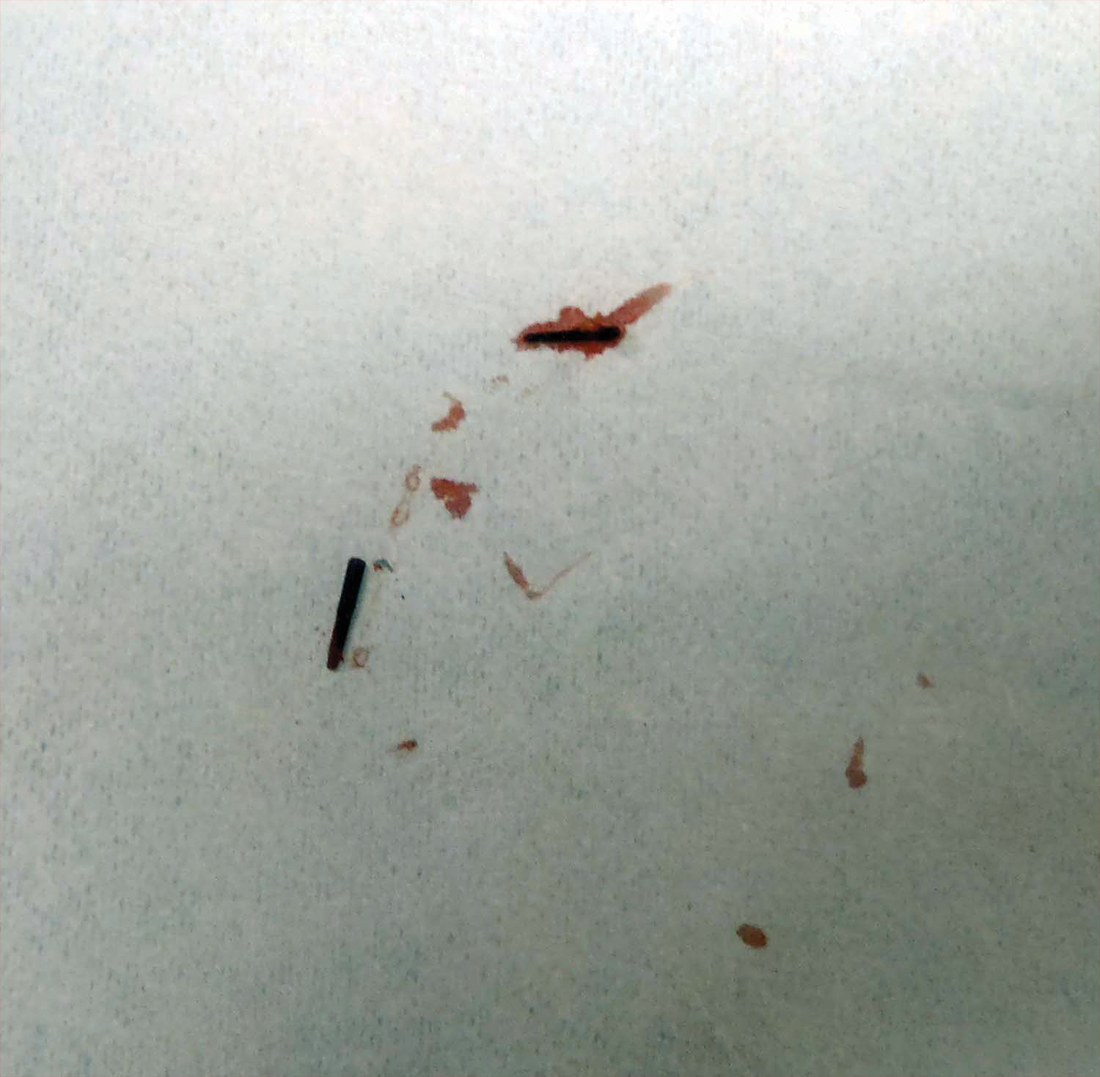

Two 6-mm punch biopsies were performed on representative nodules on the right thigh for histopathologic examination. Along with the biopsy tissue, firm, brown-black, linear foreign bodies consistent with sea urchin spines were extracted with forceps (Figure 3). Histopathologic examination revealed a dense, diffuse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis predominantly composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils. Proliferation of small vessels was noted. In one of the biopsies, small fragments of necrotic tissue were present. These findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation and granulation tissue due to a foreign body.

At the time of suture removal 2 weeks later, the biopsied areas were well healed with minimal erythema. The patient reported decreased pain in the involved areas. He was not seen in clinic again due to resolution of the nodules and associated pain.

Comment

Sea urchin spine injuries are commonly seen in coastal regions with frequent participation in recreational and occupational water activities. A wide variety of responses can be seen in sea urchin spine injuries. There generally are 2 types of cutaneous reaction patterns to sea urchin spines: a primary initial reaction and a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction. When the spines initially penetrate the skin, the primary initial reaction consists of sharp localized pain that worsens with applied pressure. In addition to pain, bleeding, erythema, edema, and myalgia can occur.3 These symptoms typically subside a few hours after complete removal of the spines from the skin.6 If some spines remain in the skin, a secondary delayed/granulomatous reaction can occur, which can lead to the formation of granulomas that can manifest as nodules or papules and can be diffuse.

Many patients may think their painful encounter with a sea urchin was just an unfortunate event, but depending on the location of the injury, more serious extracutaneous reactions and chronic symptoms may occur. Some cases have described the development of arthritis and synovitis from the implantation of spines into joints.1,2,4-6 Other extracutaneous complications include neuropathy and paresthesia, local bone destruction, radiating pain, muscular weakness, and hypotension.3