User login

Tender Papules on the Bilateral Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

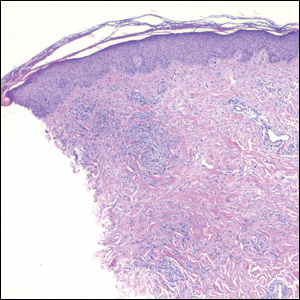

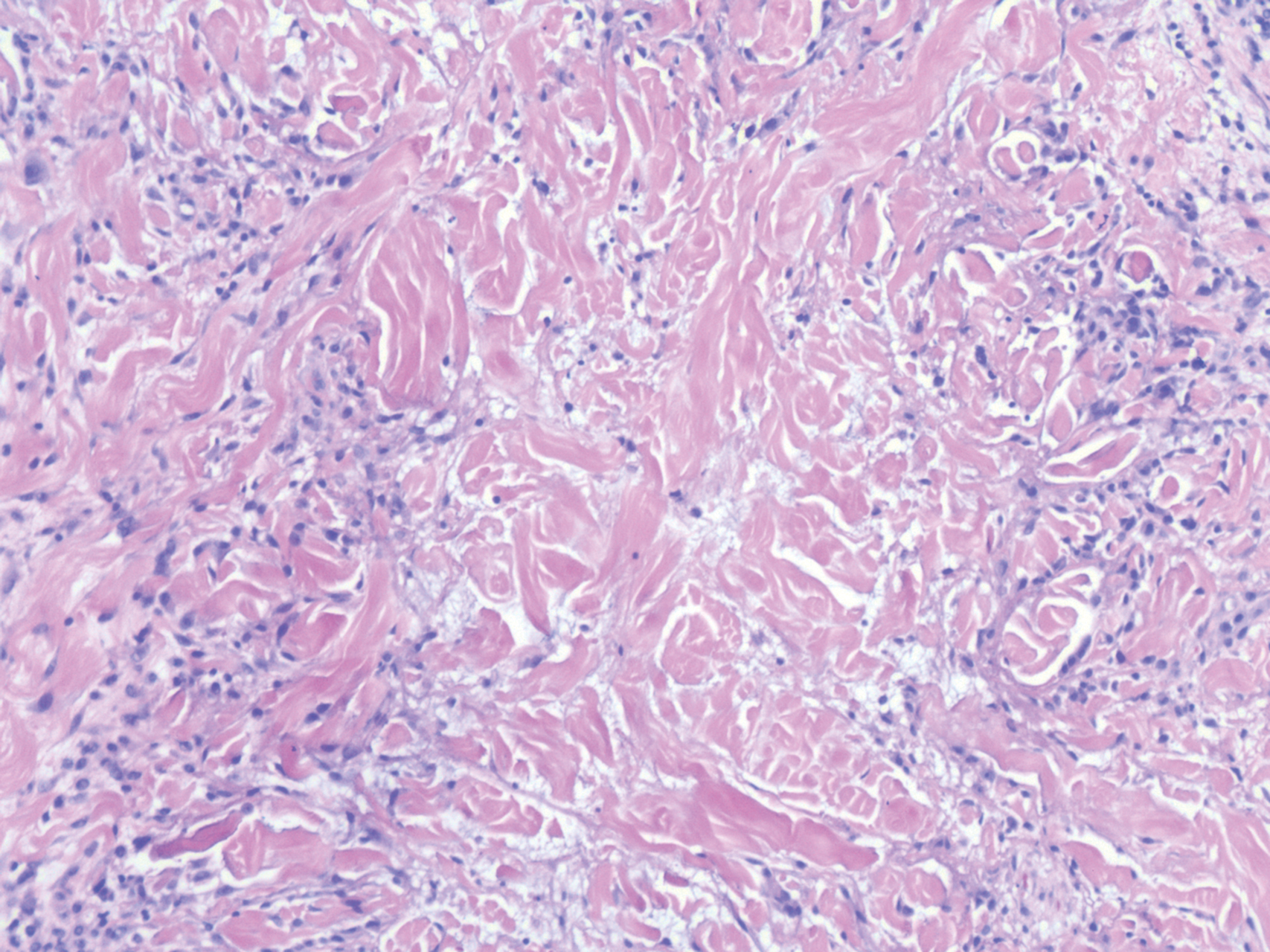

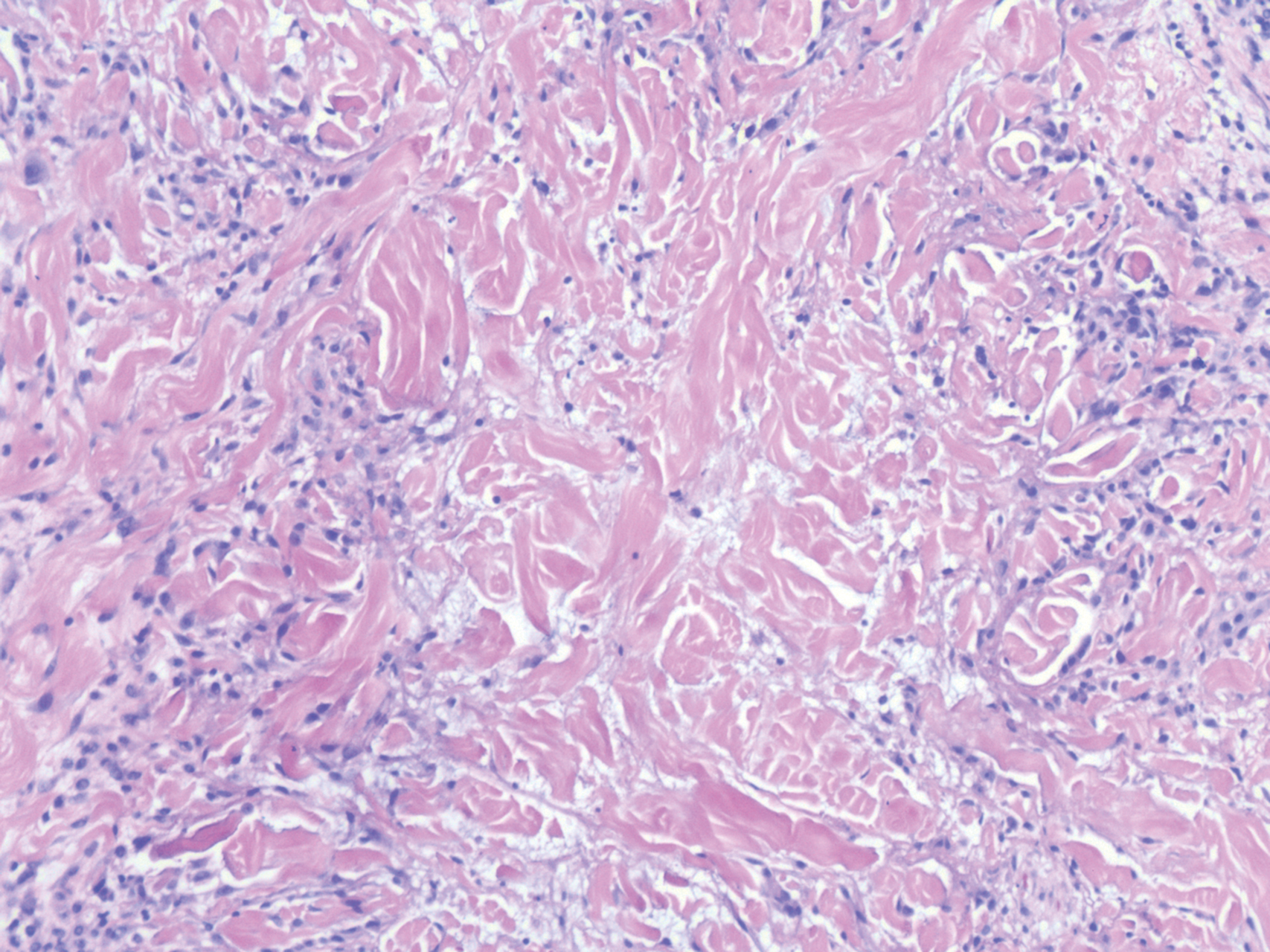

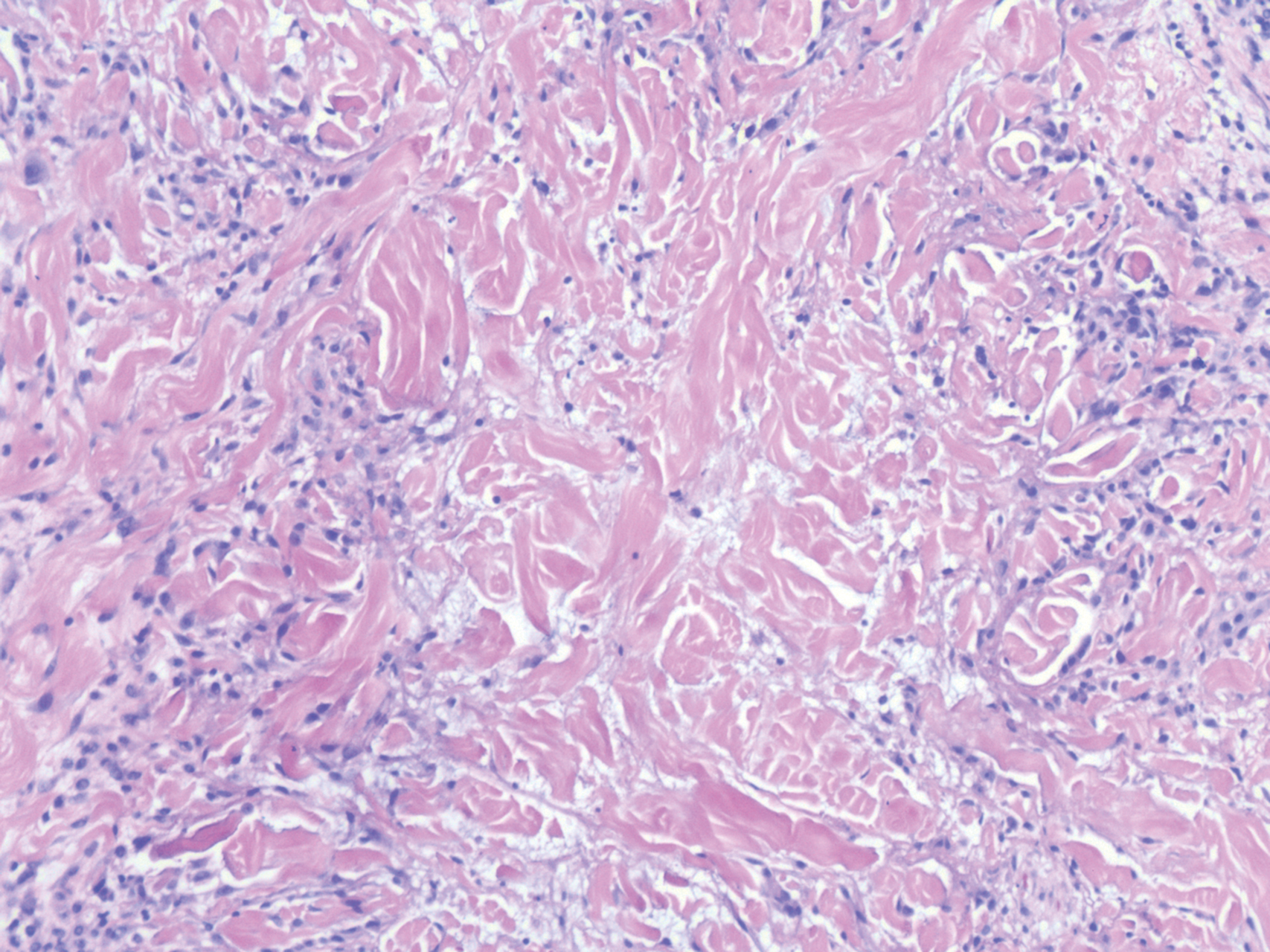

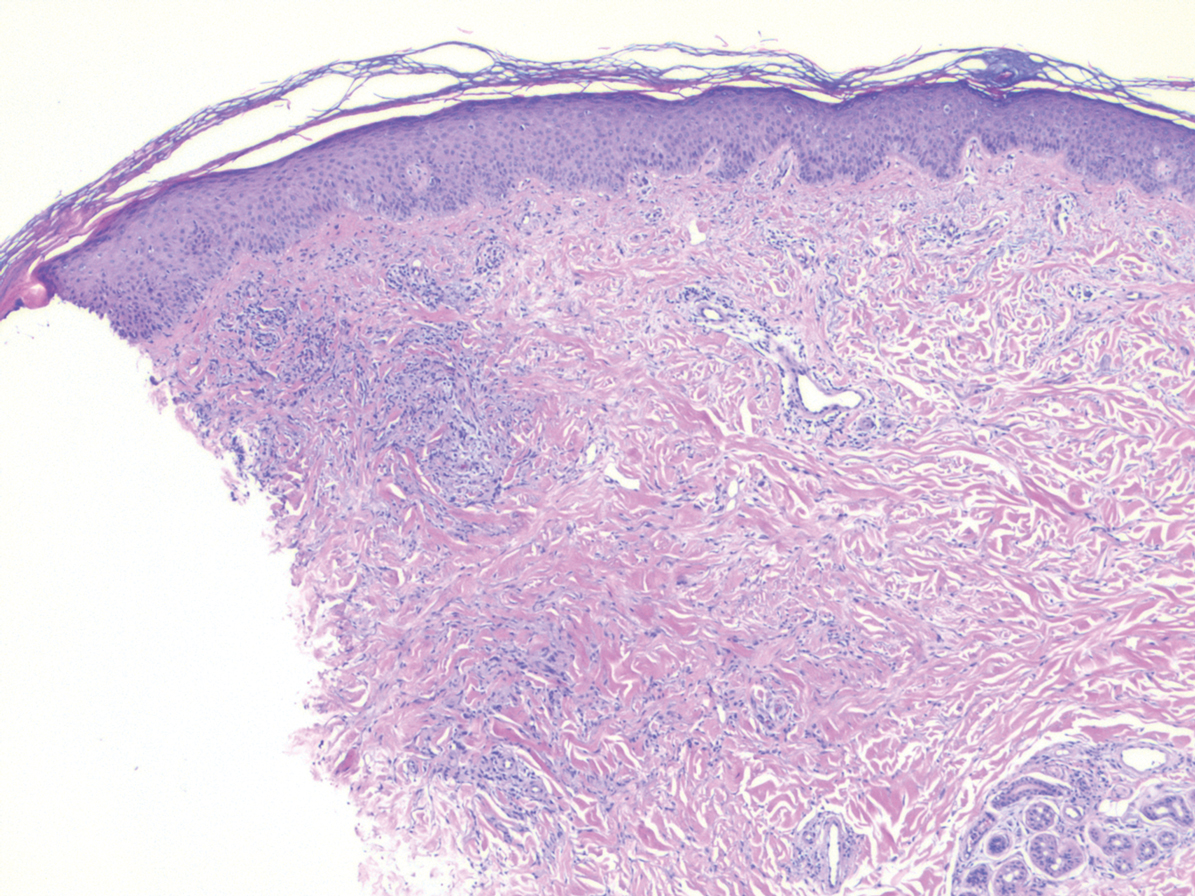

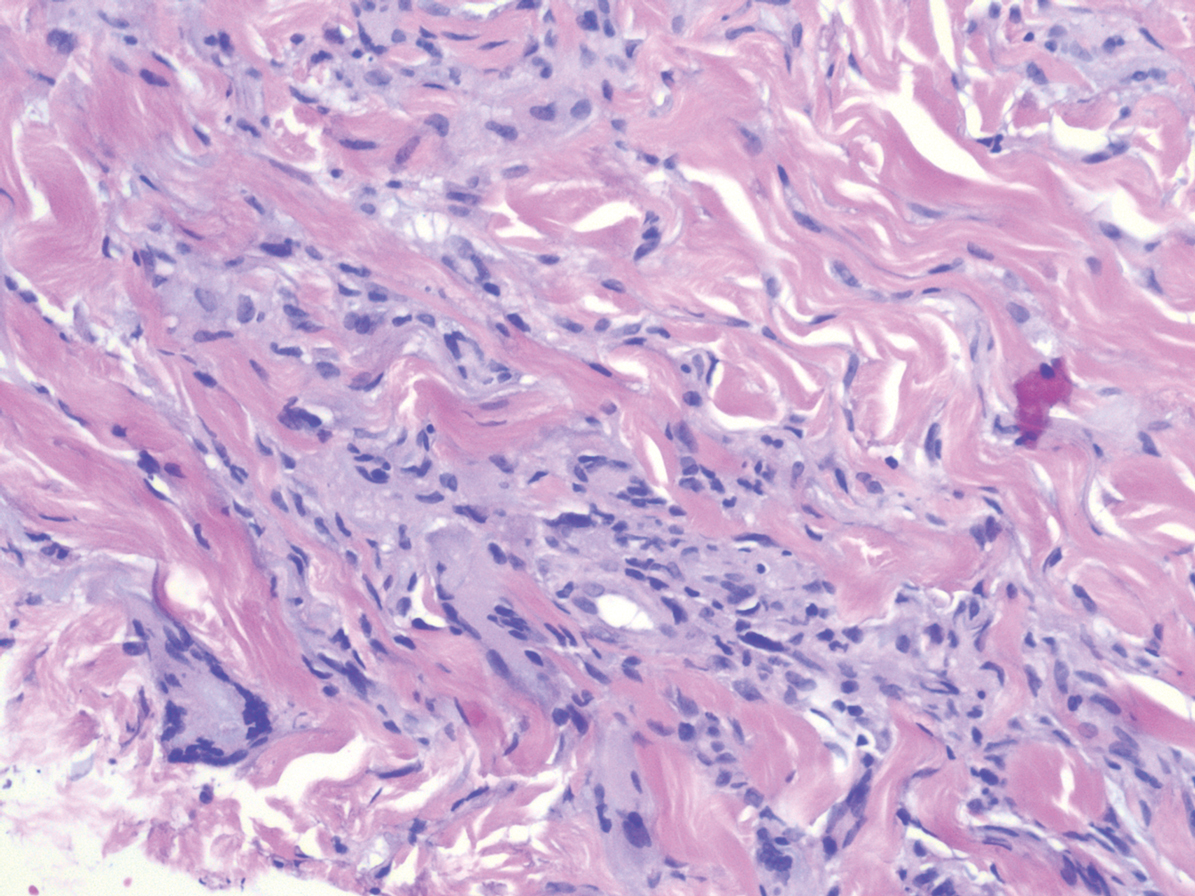

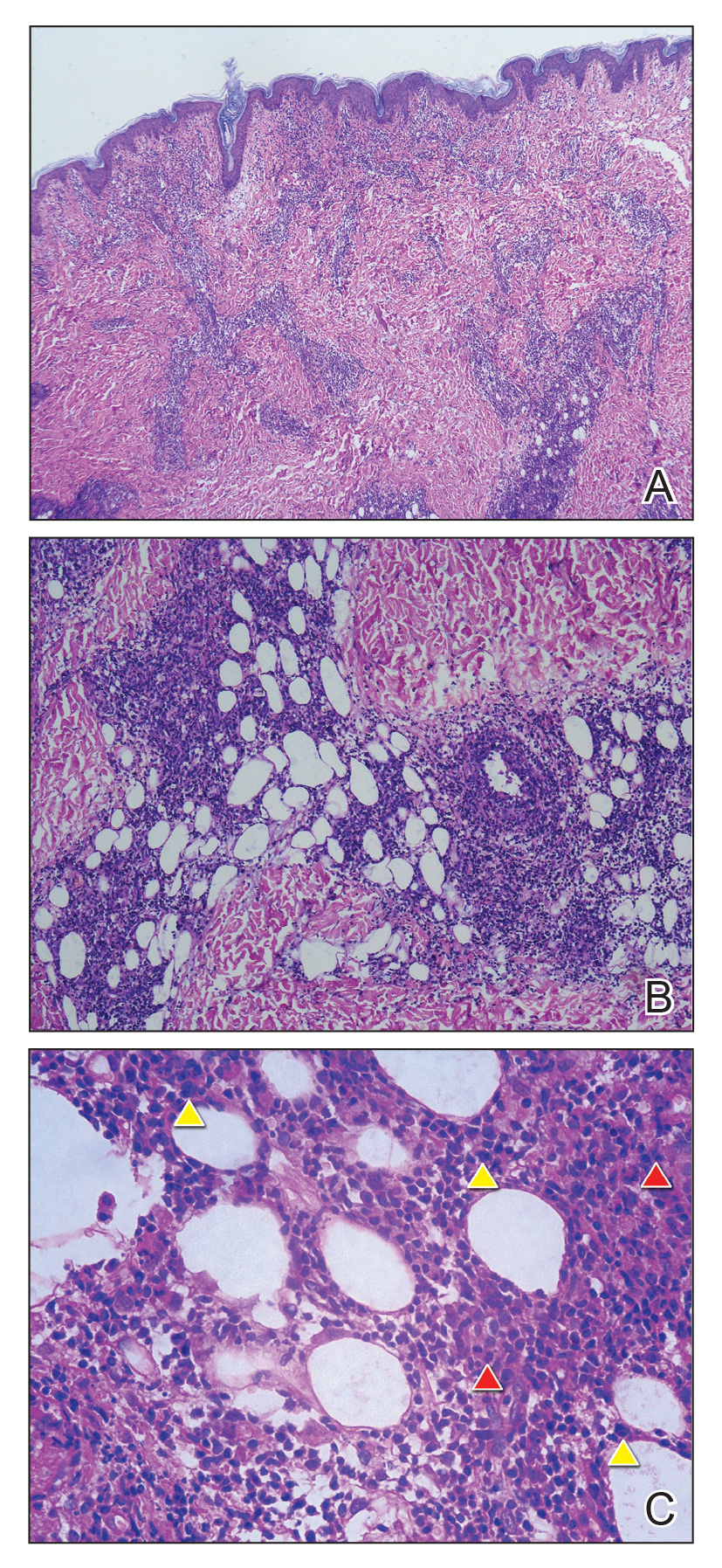

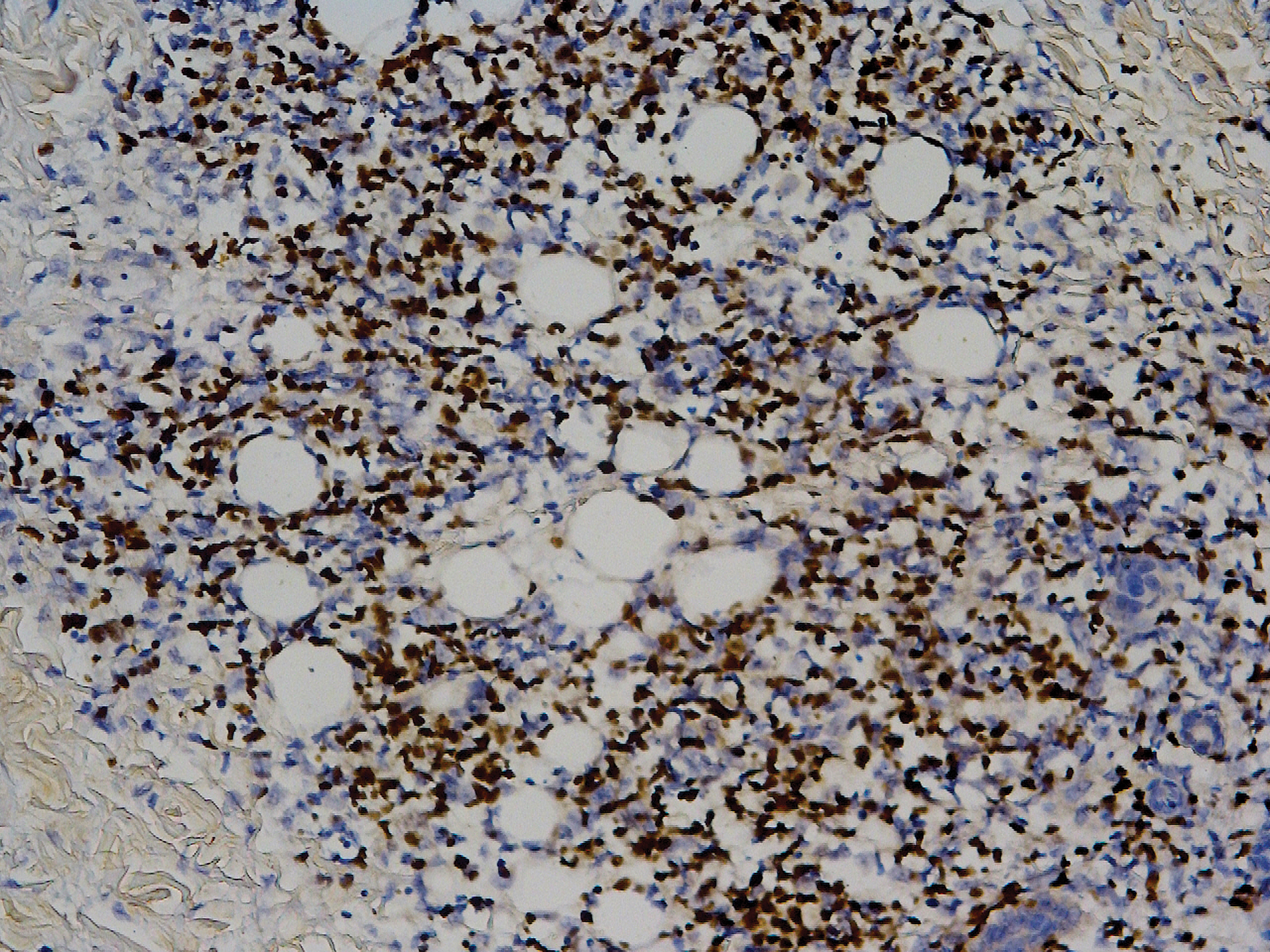

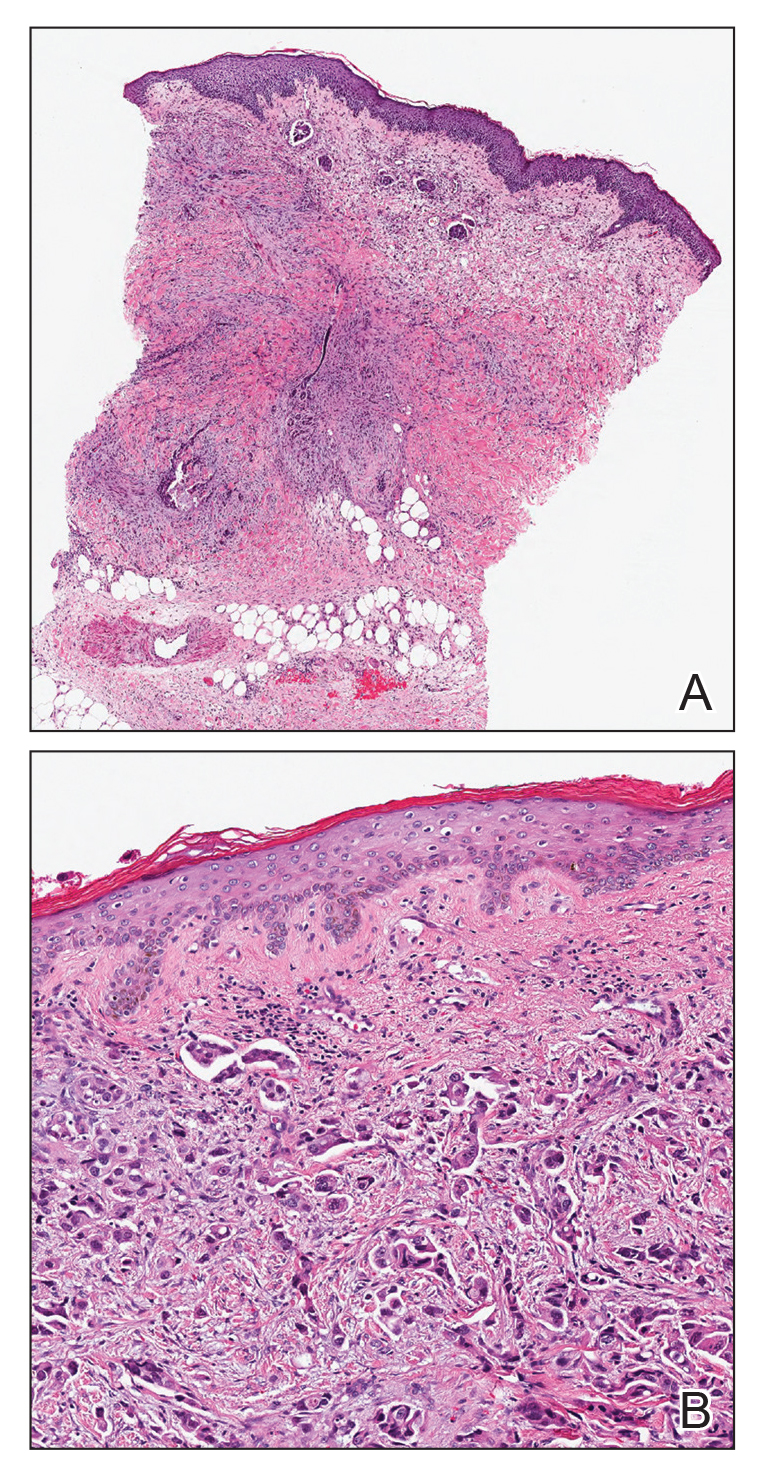

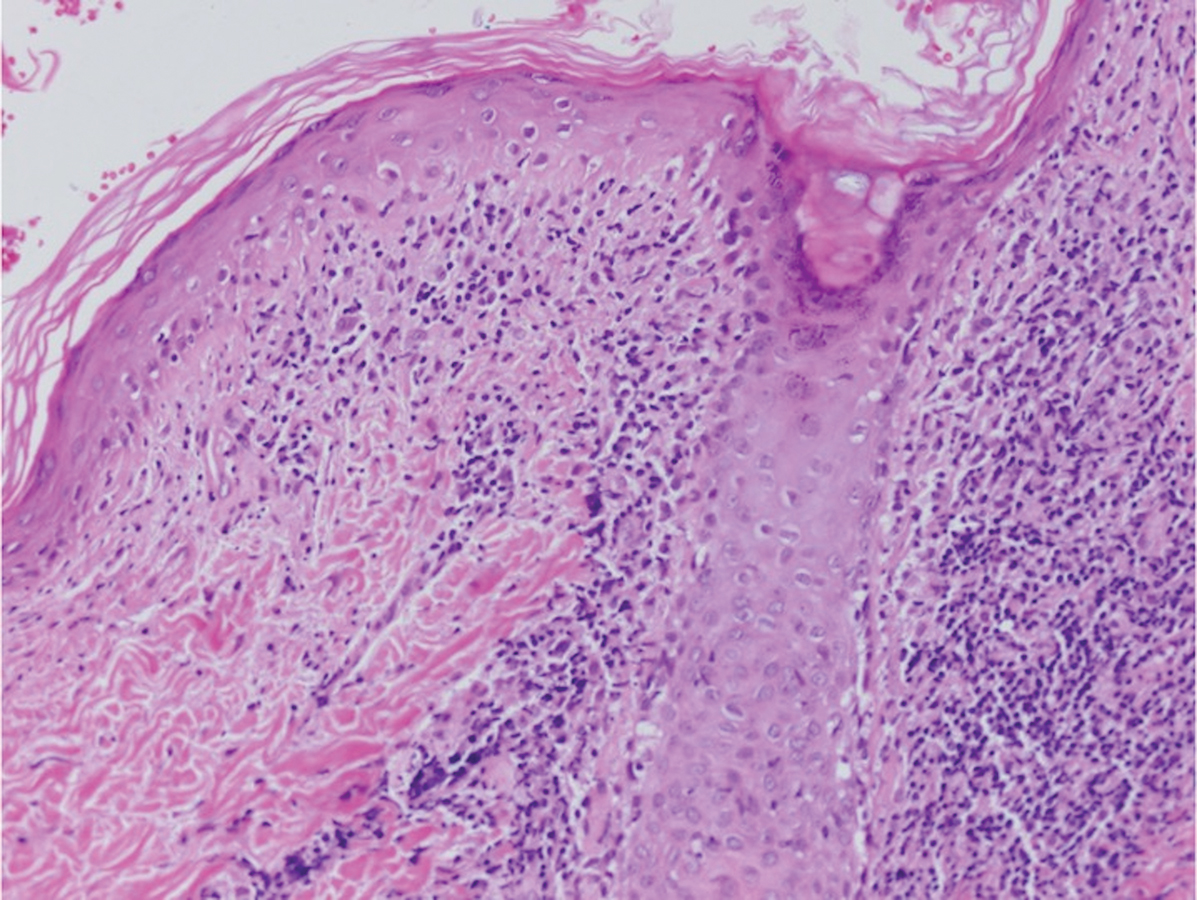

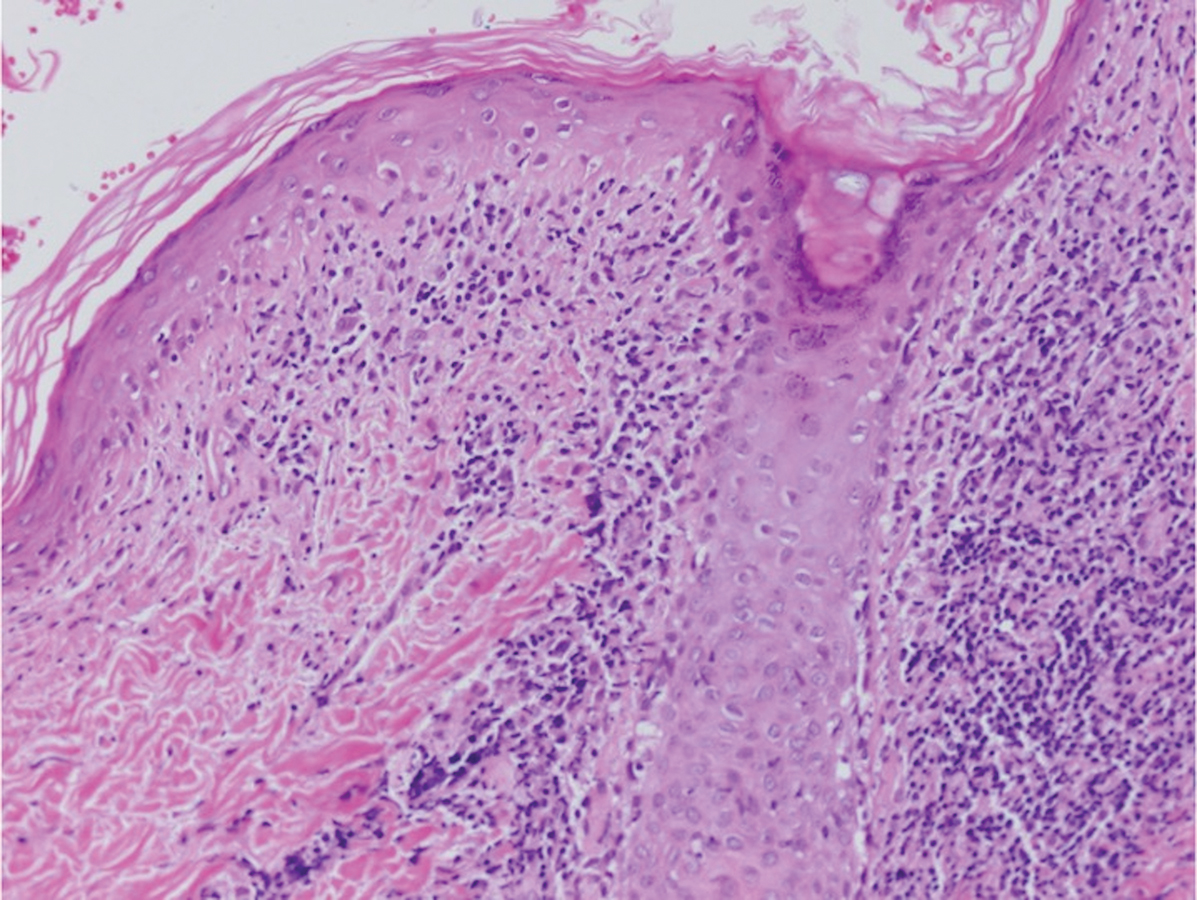

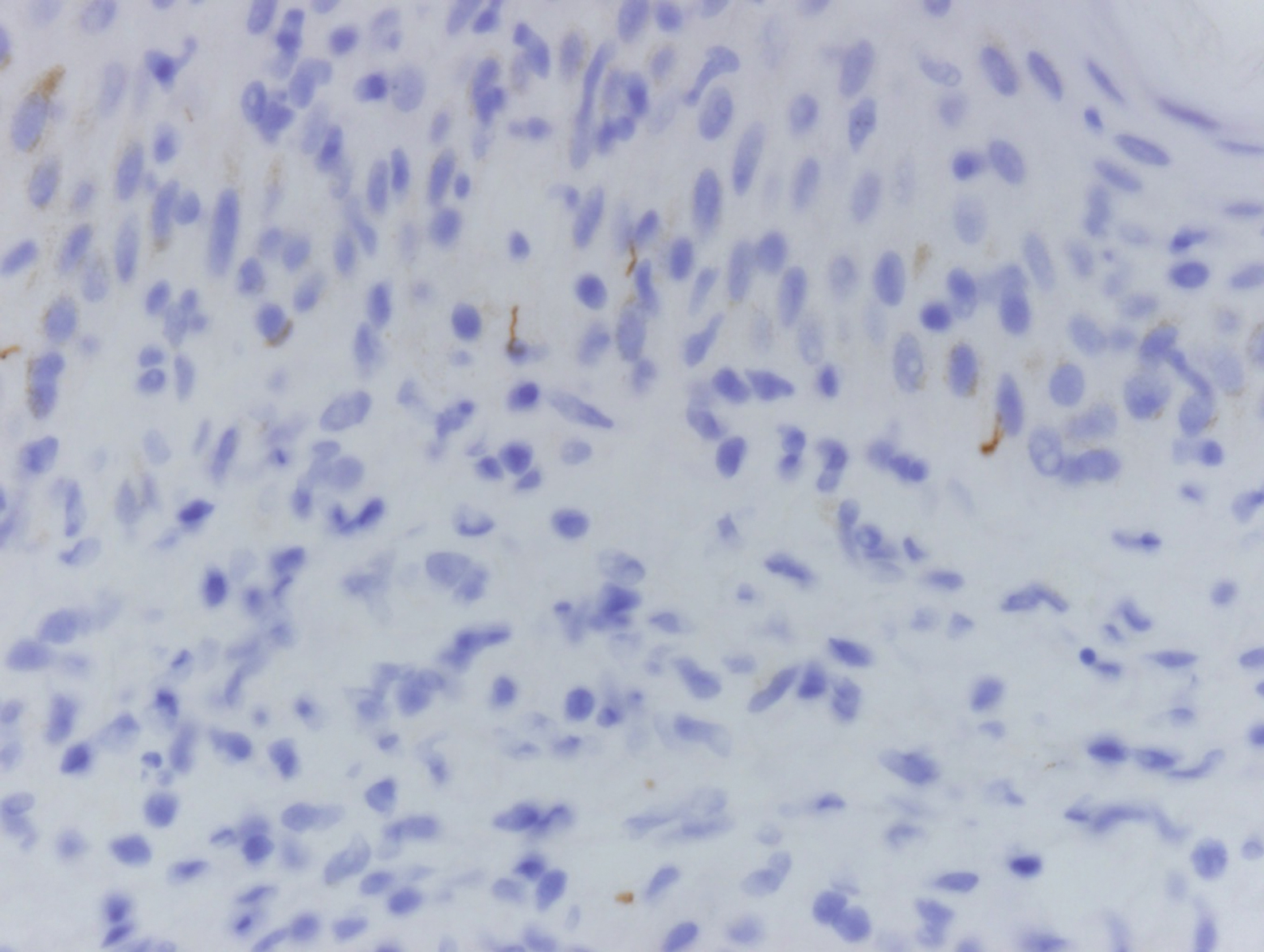

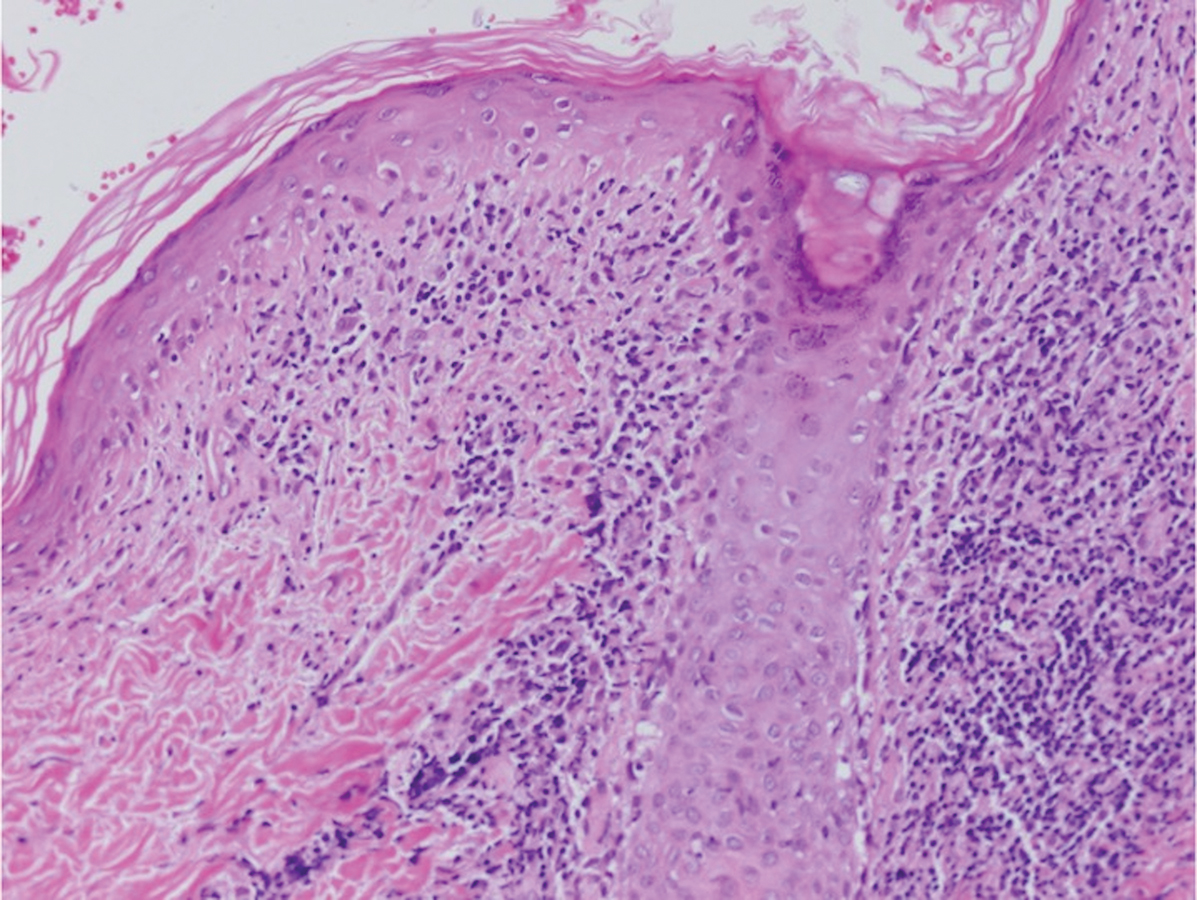

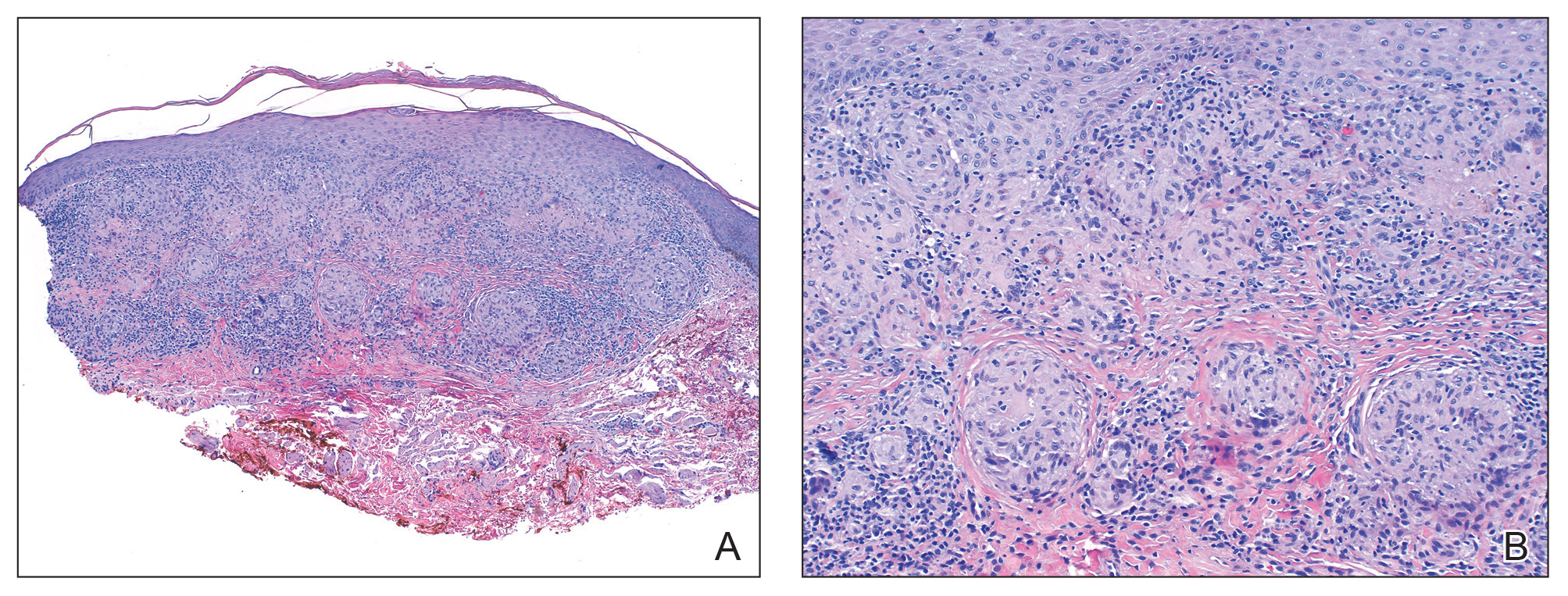

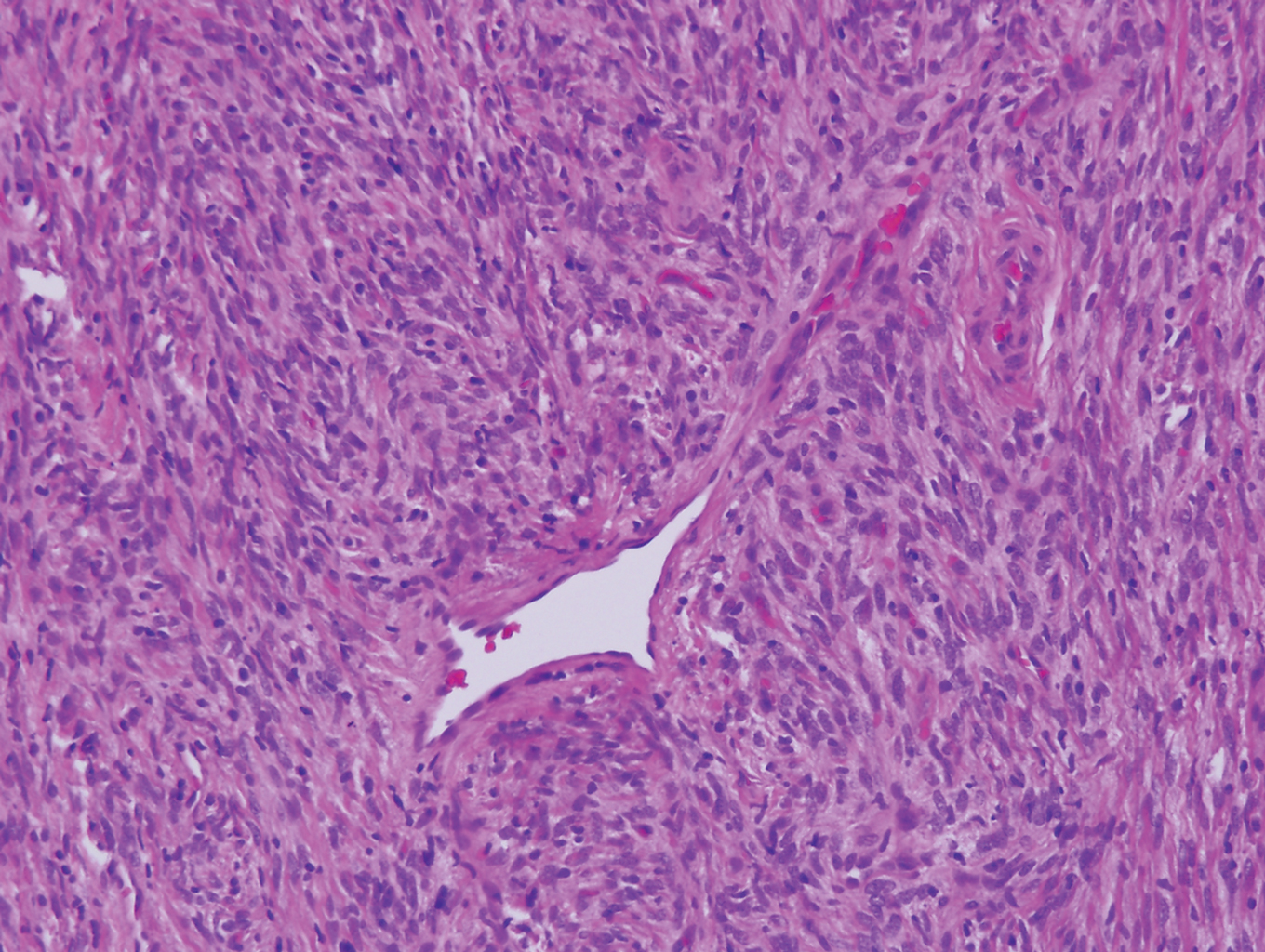

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

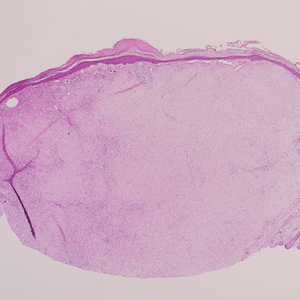

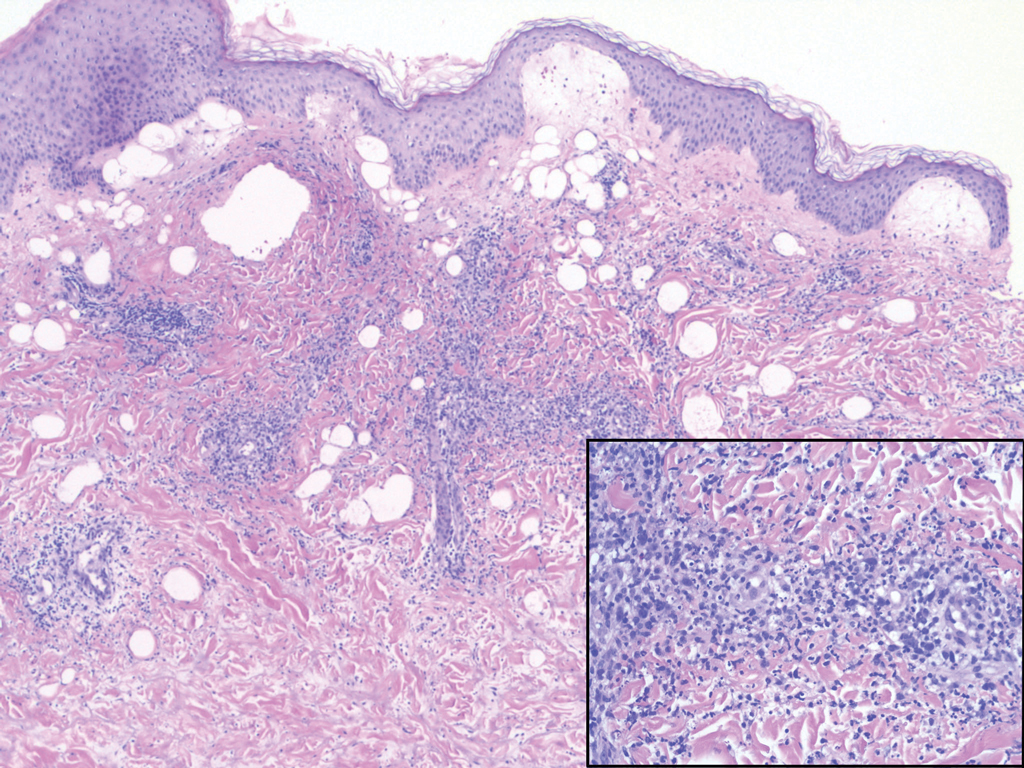

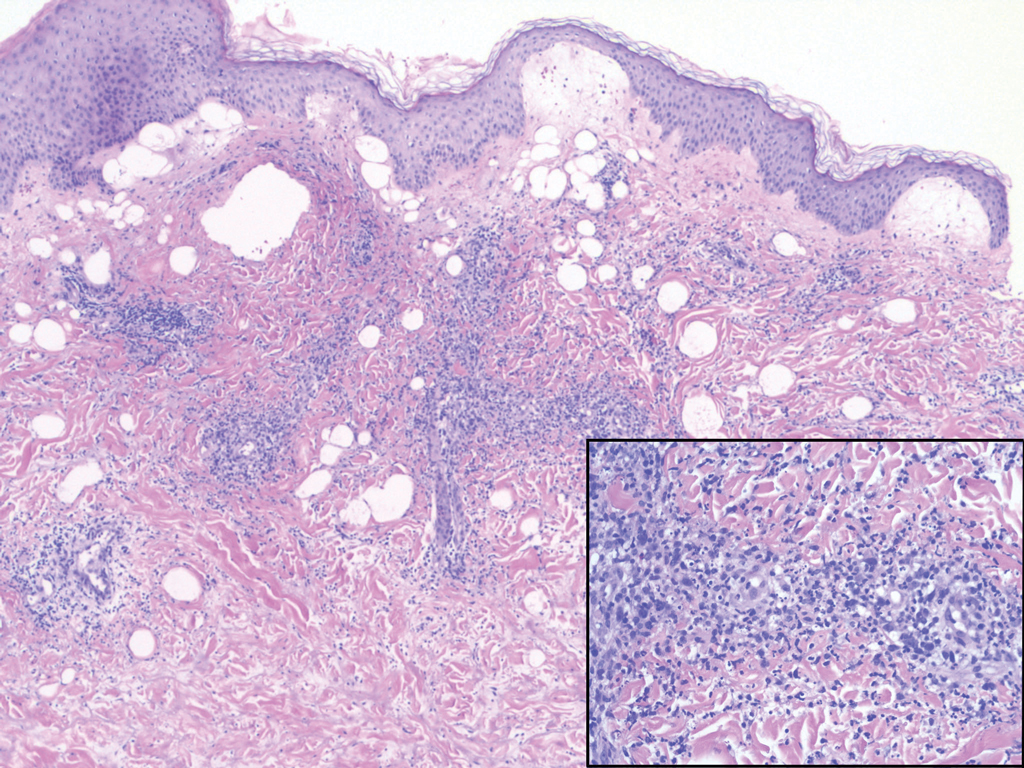

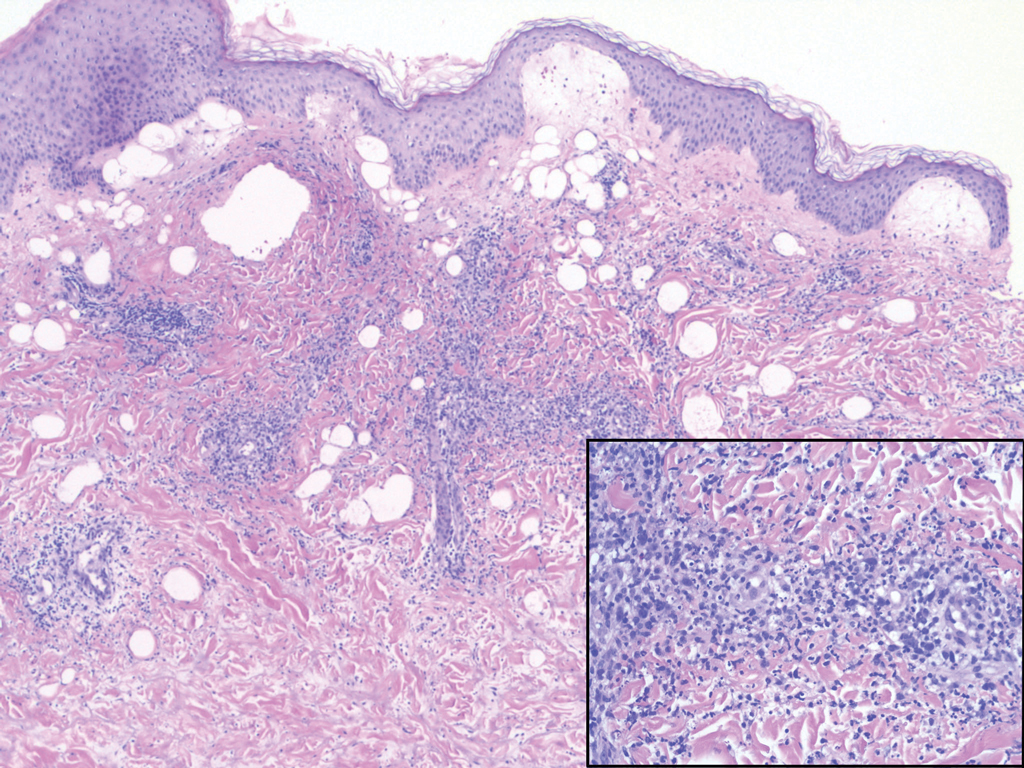

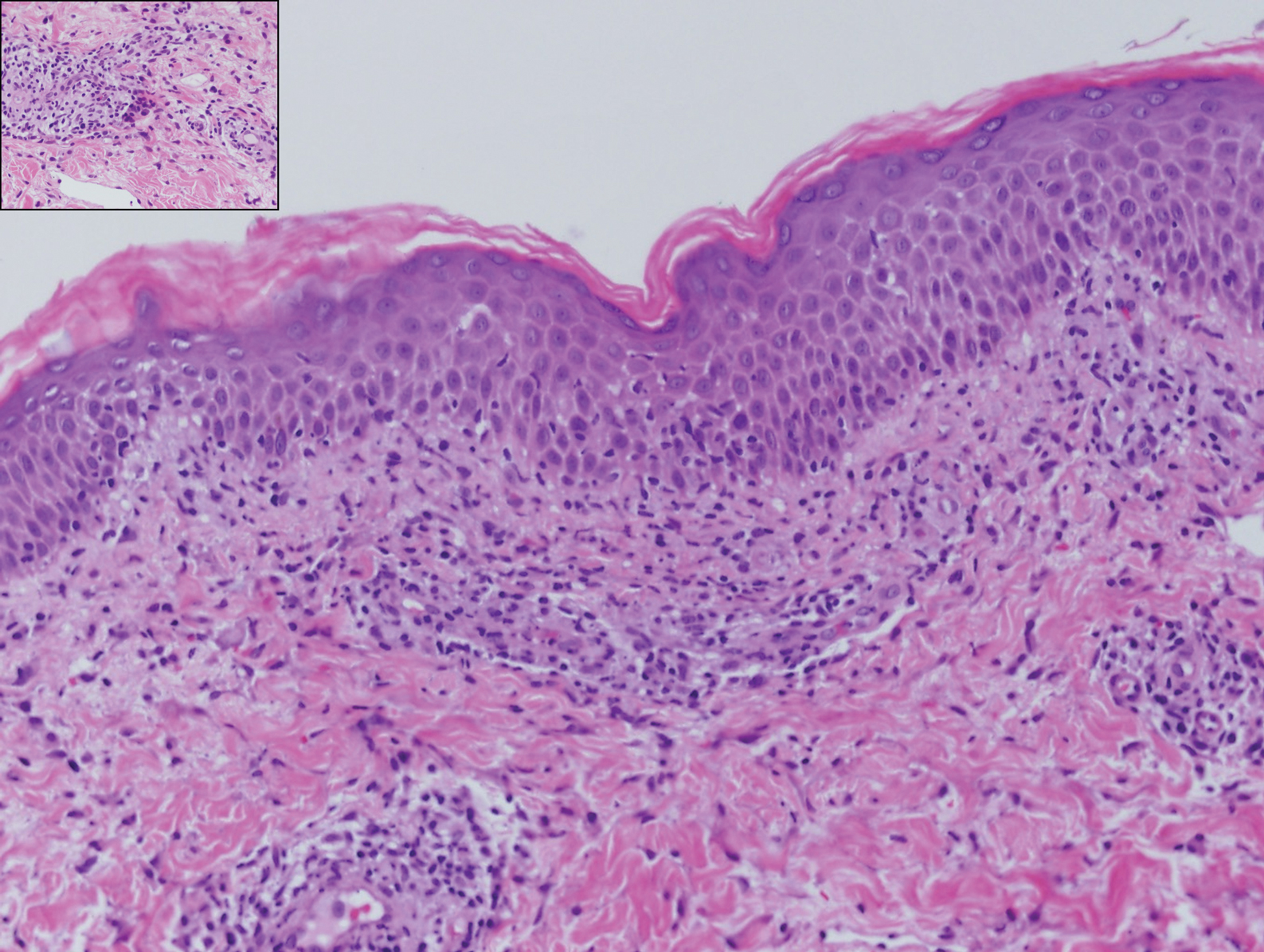

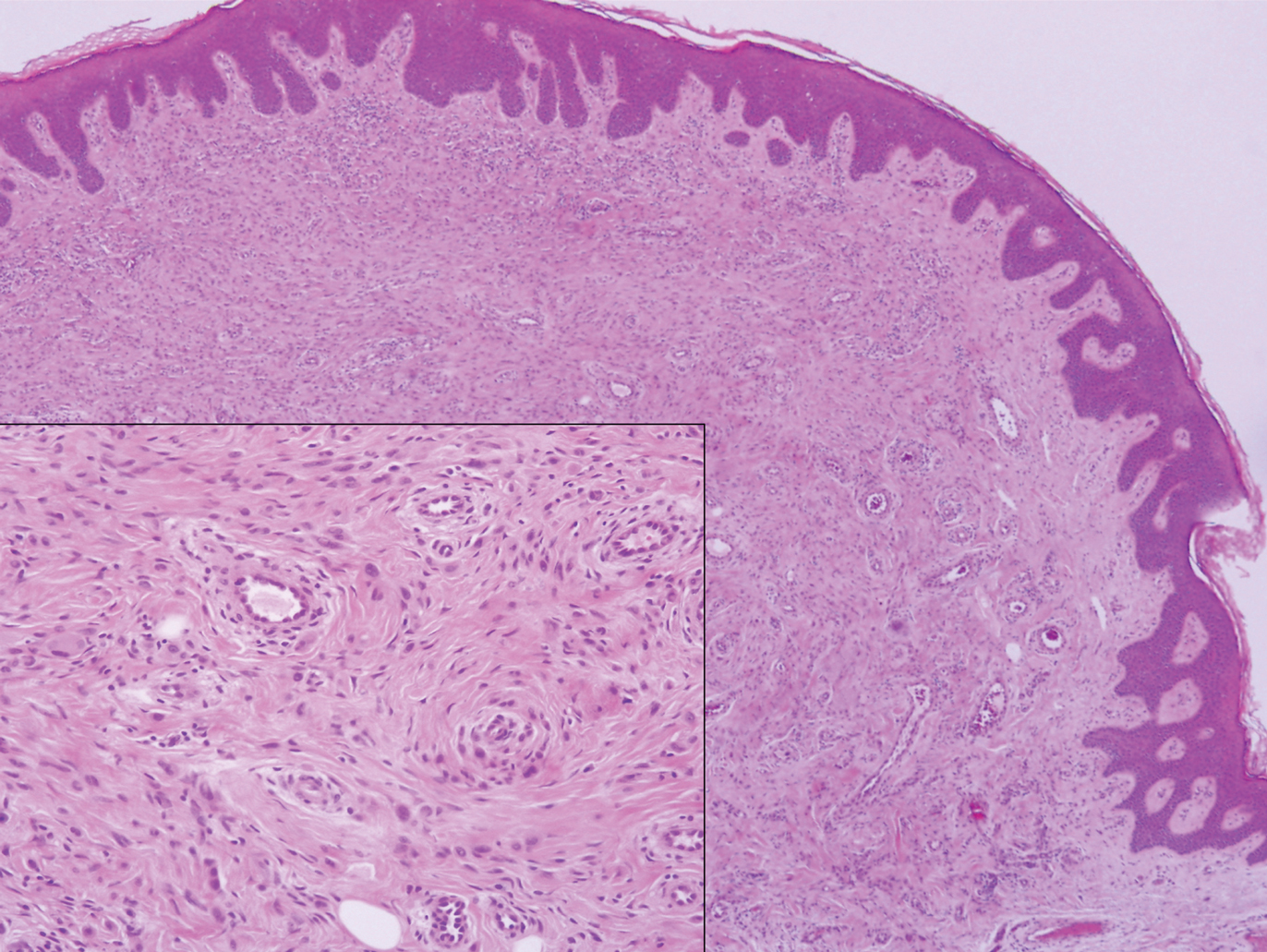

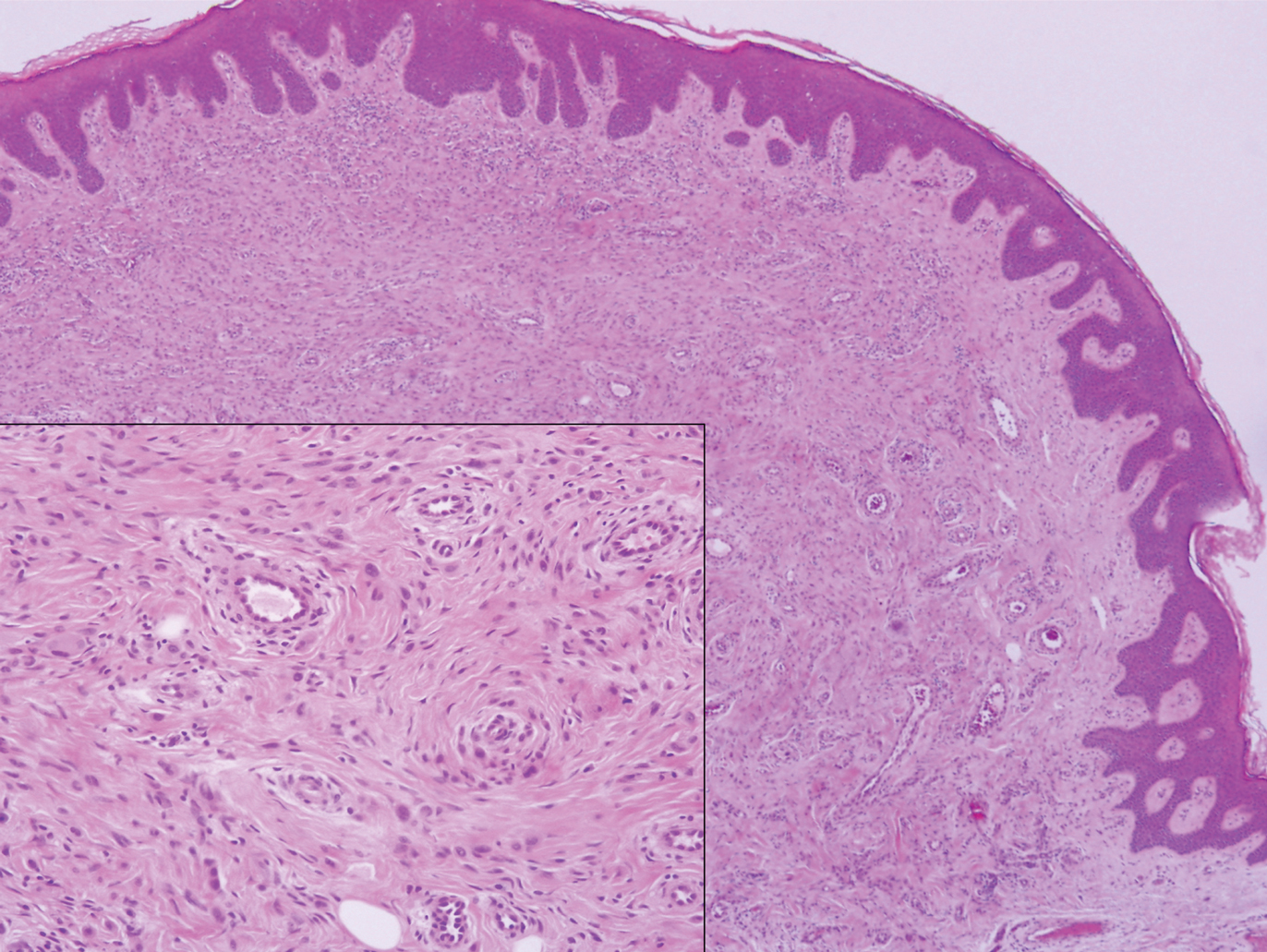

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

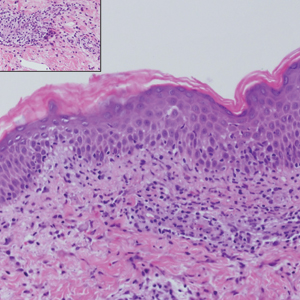

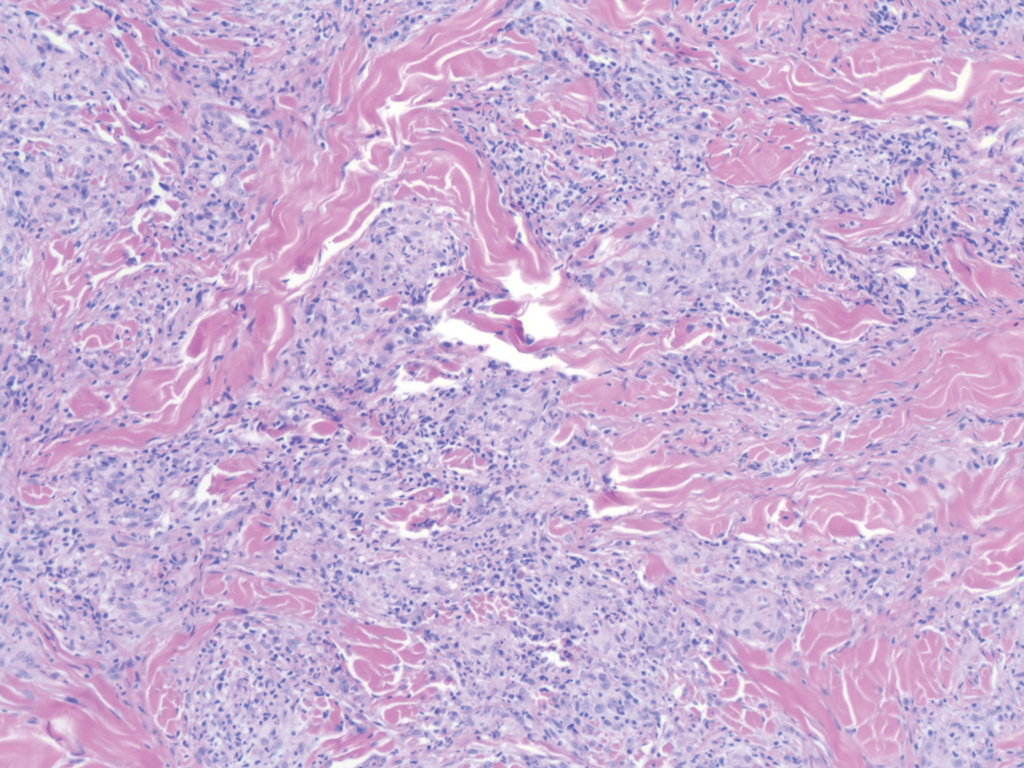

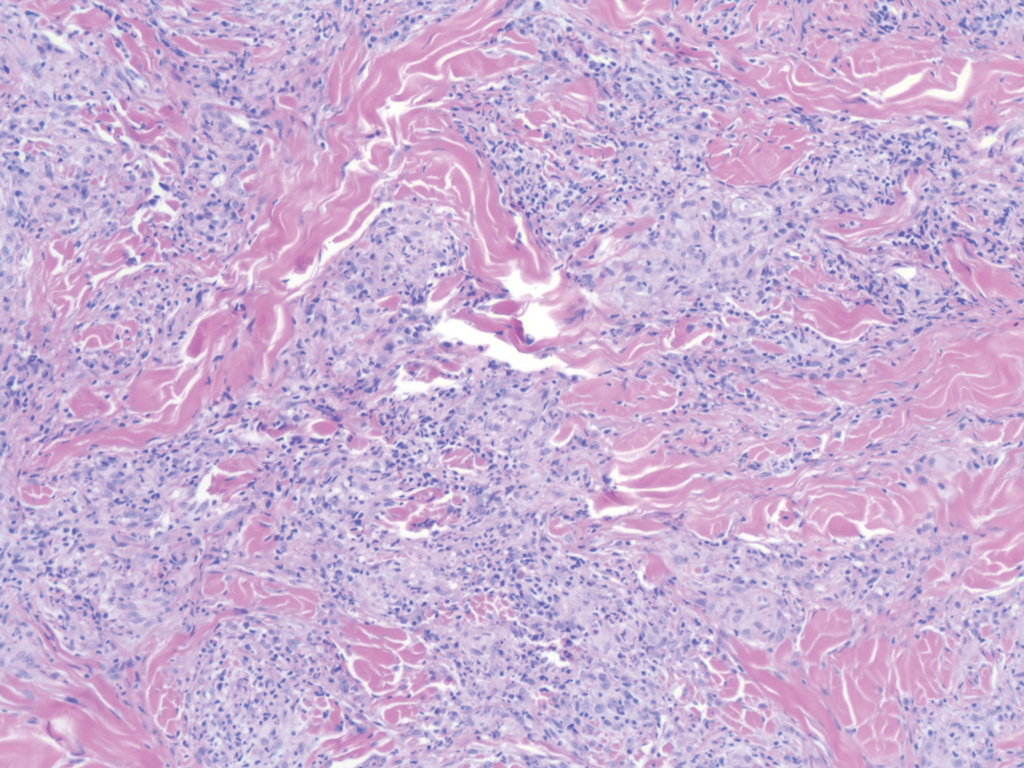

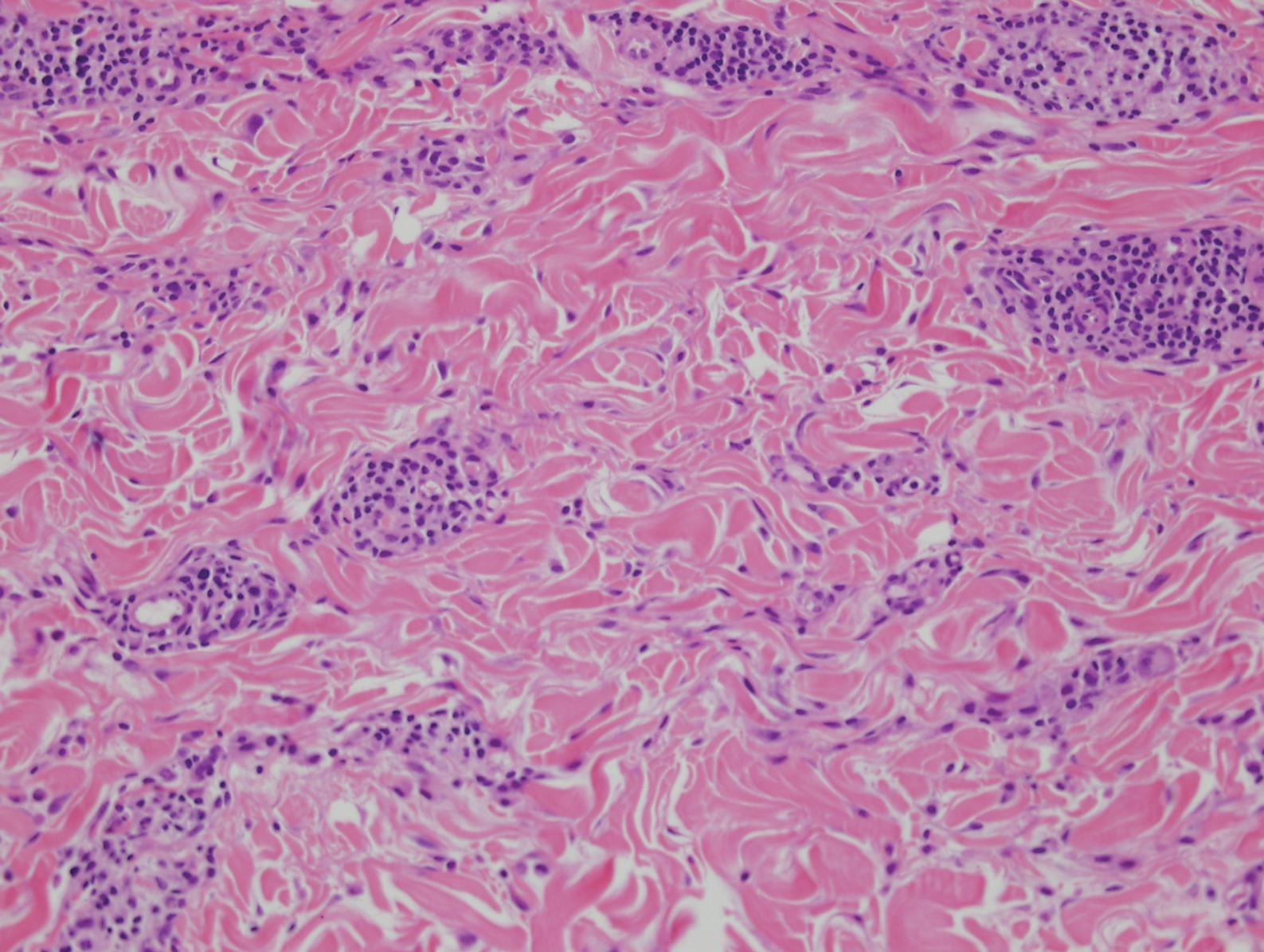

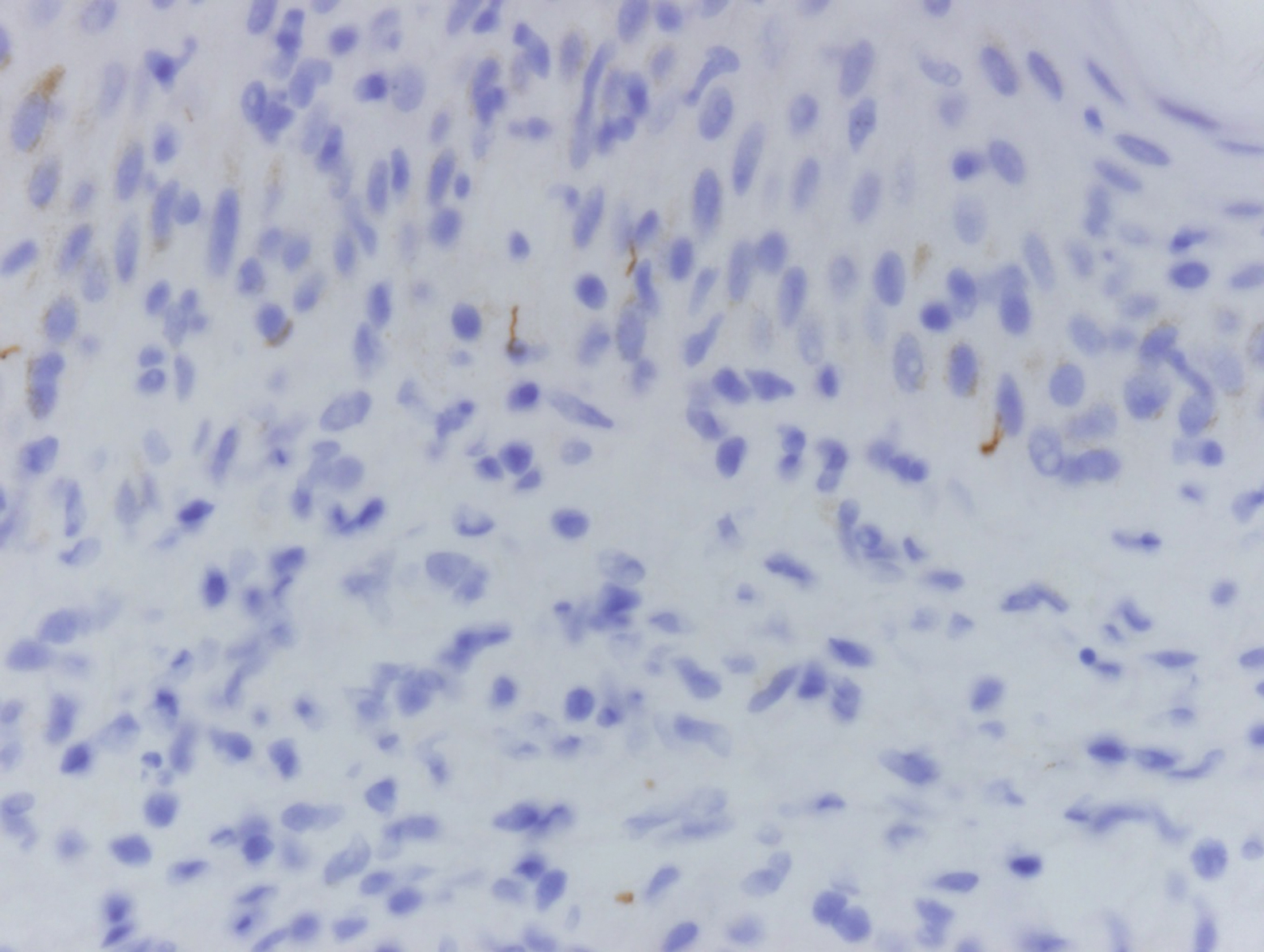

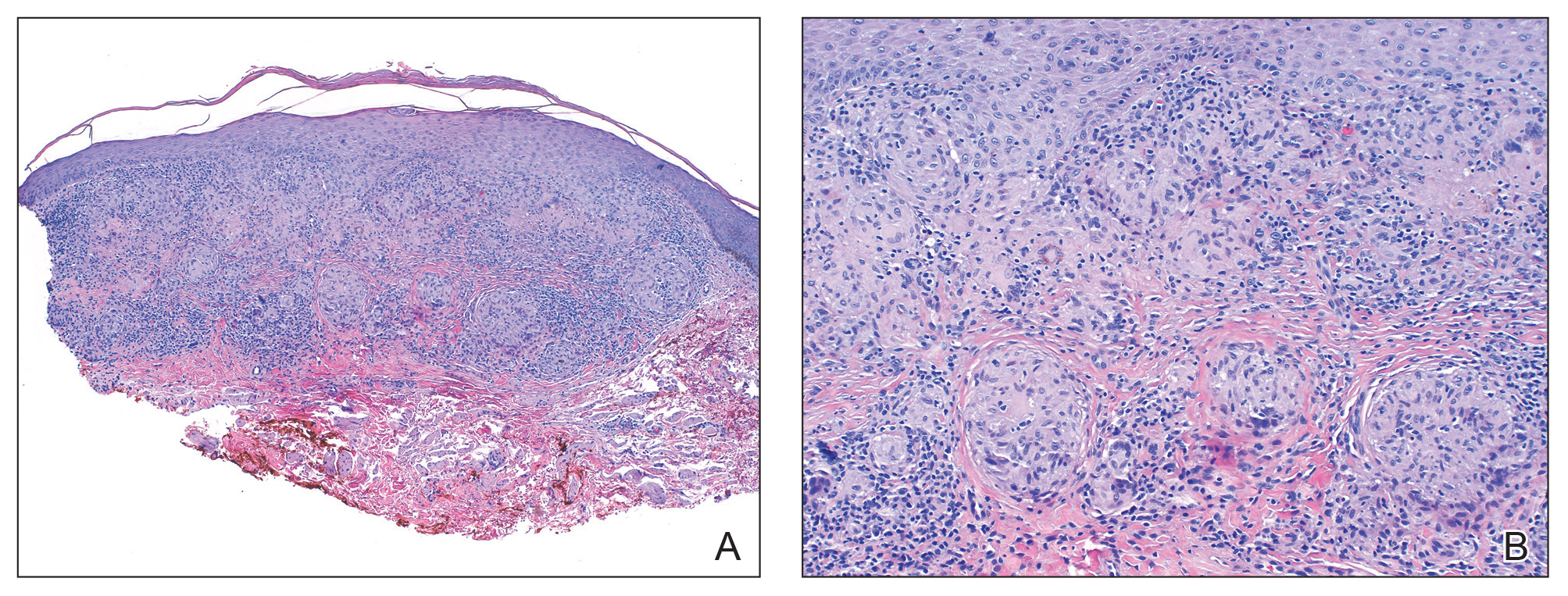

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

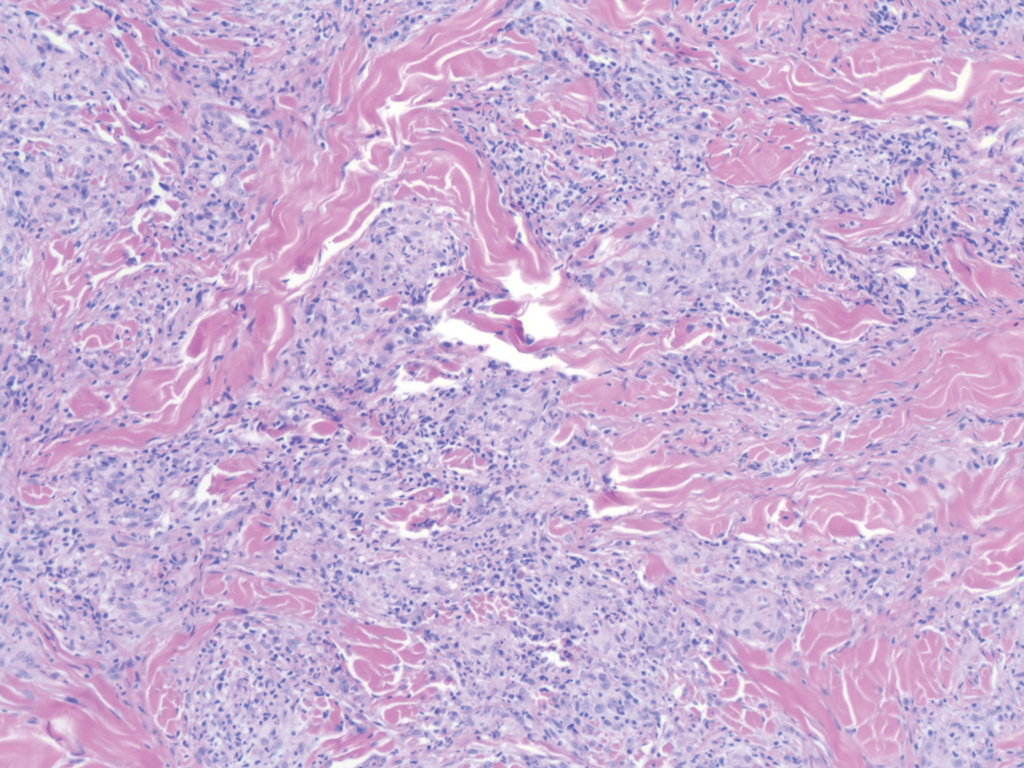

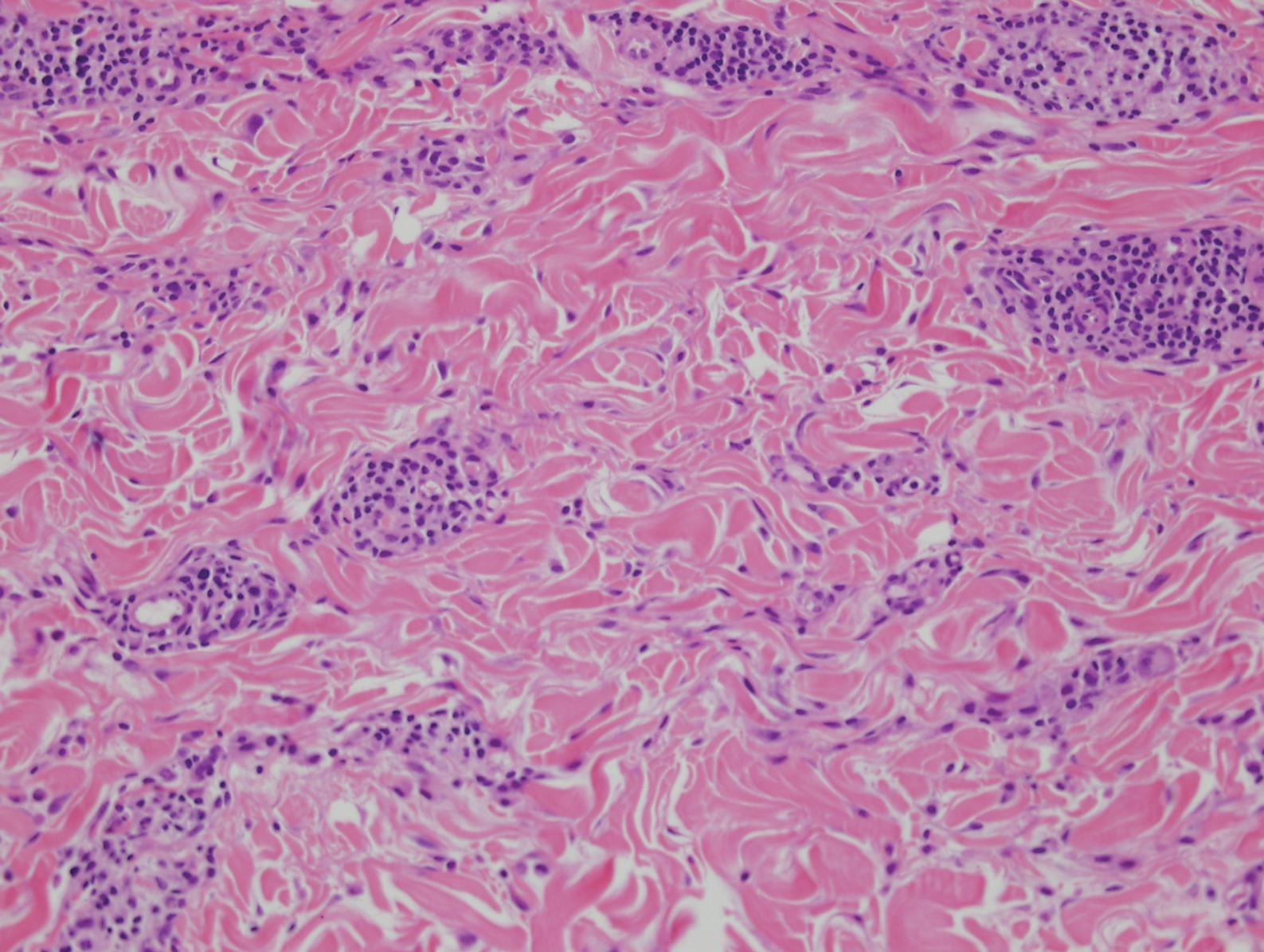

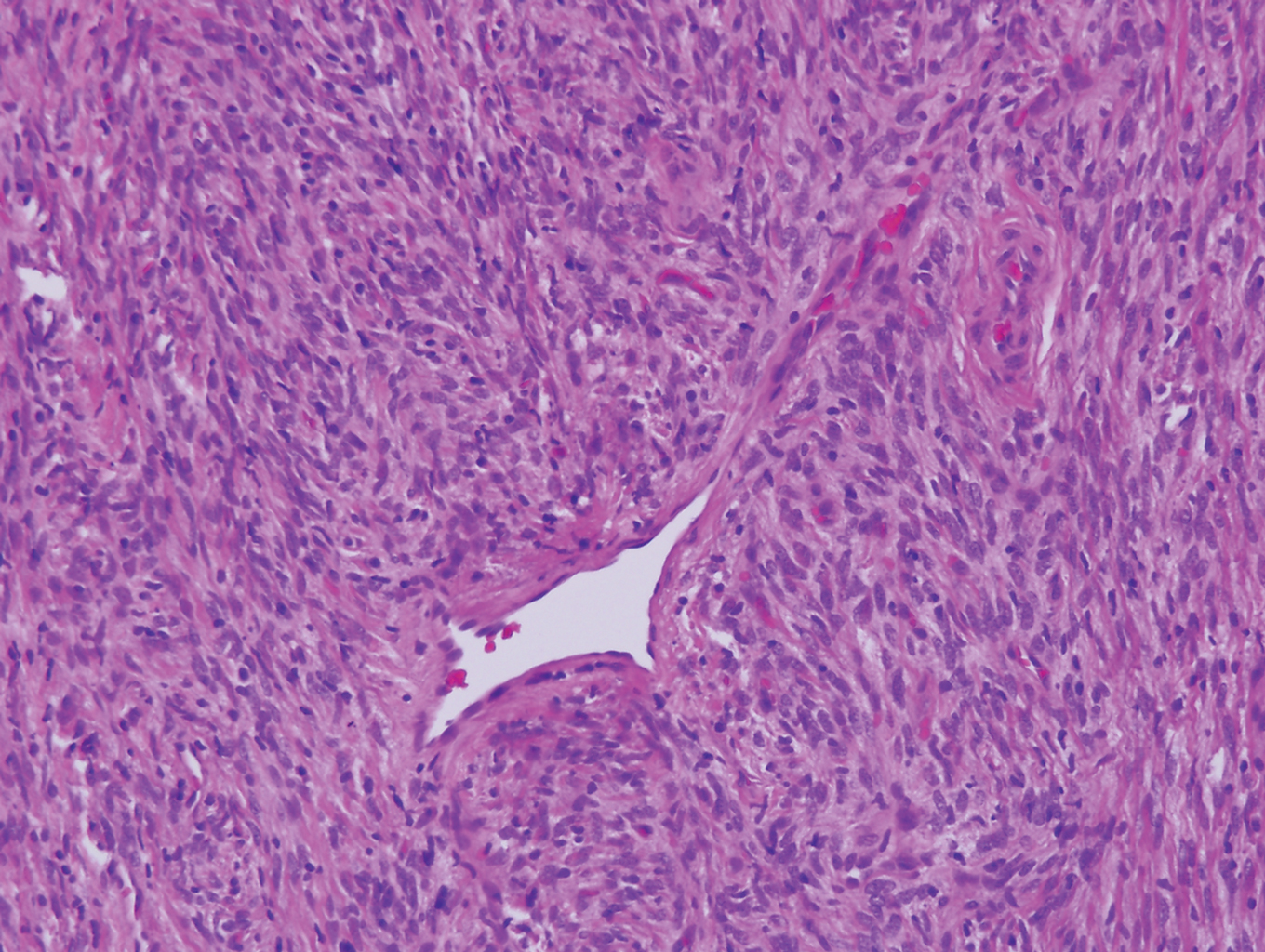

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

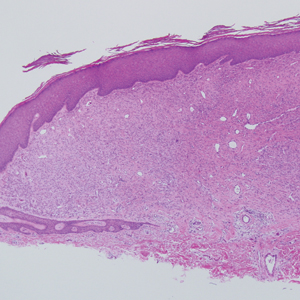

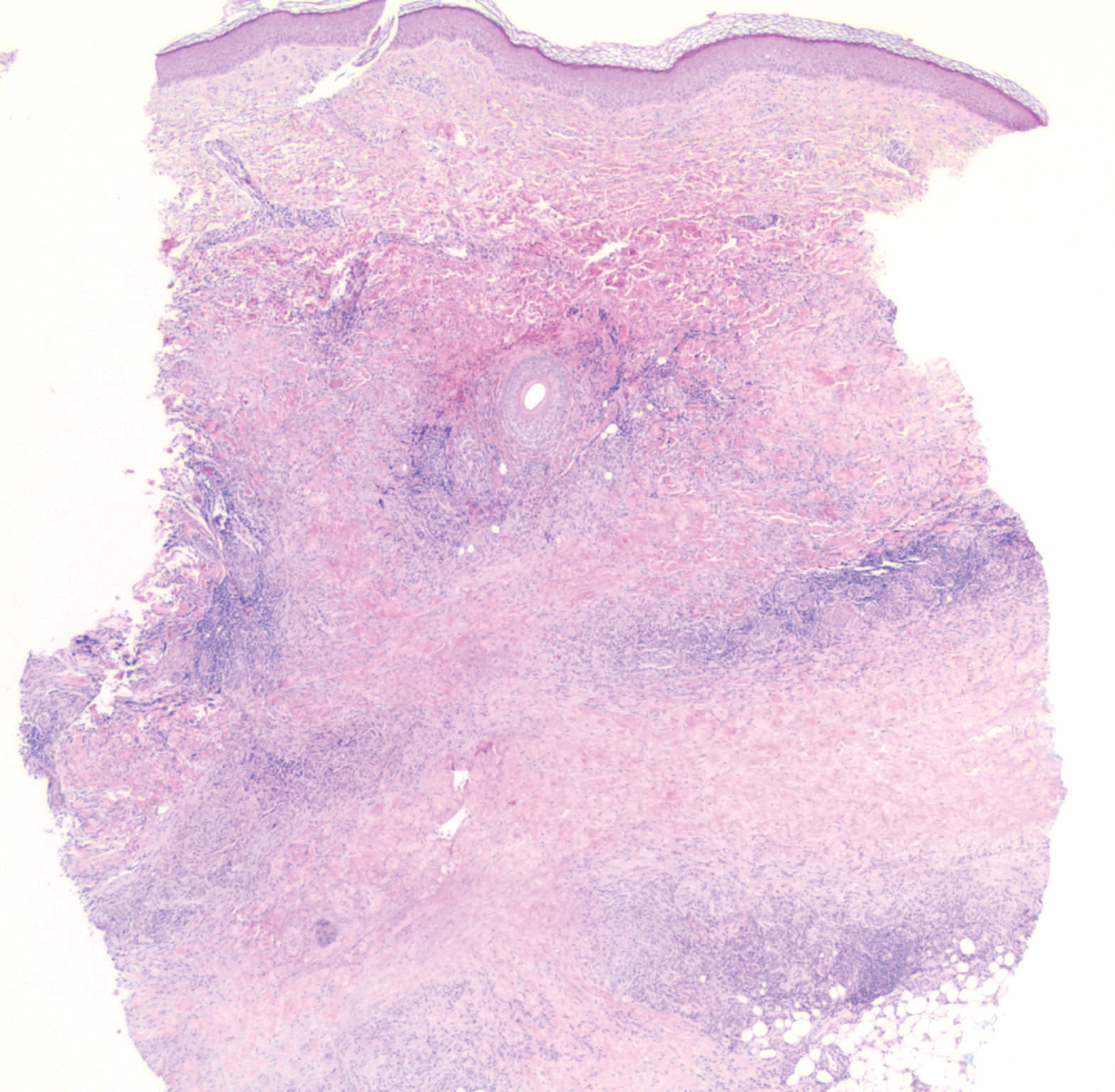

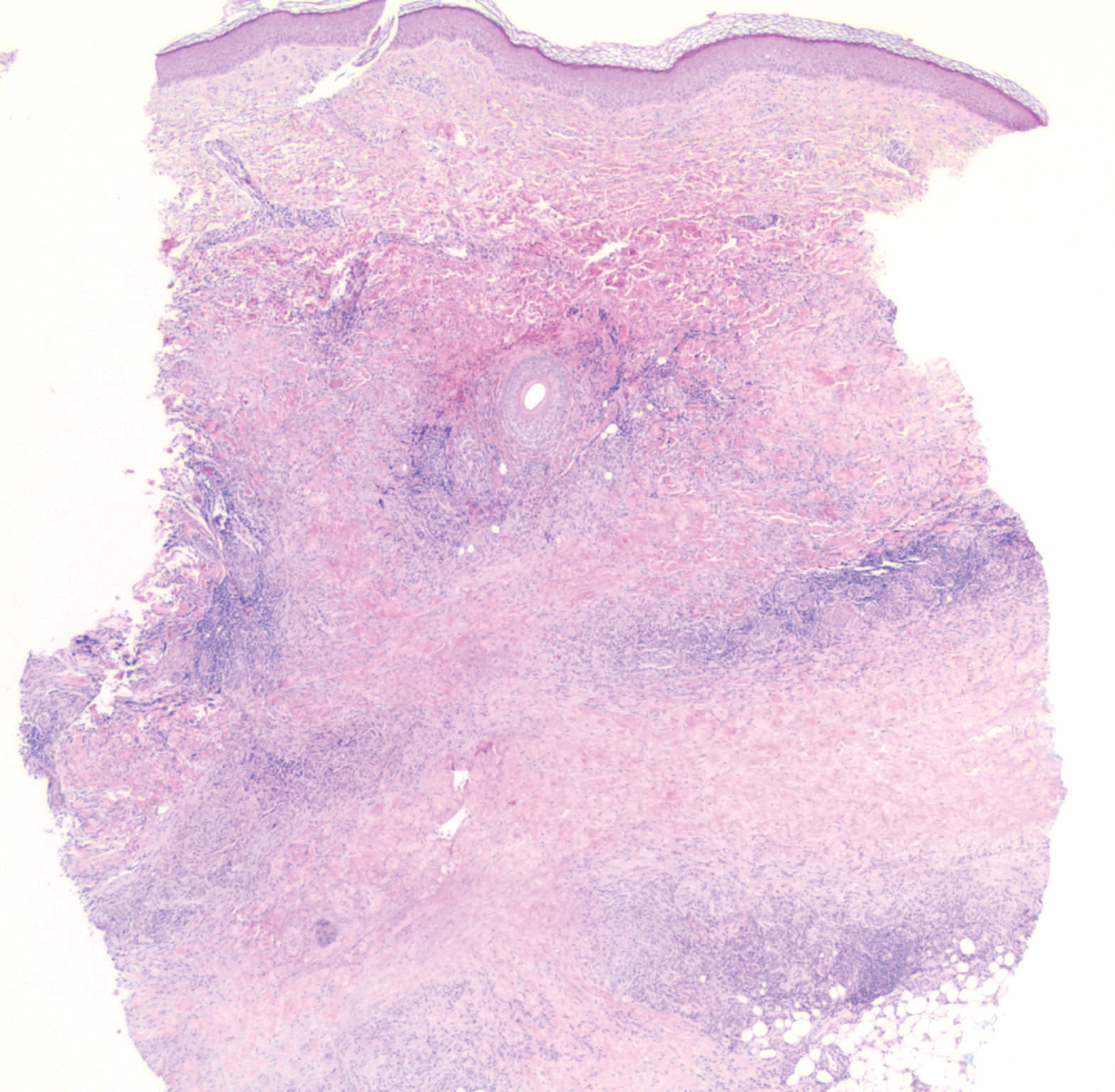

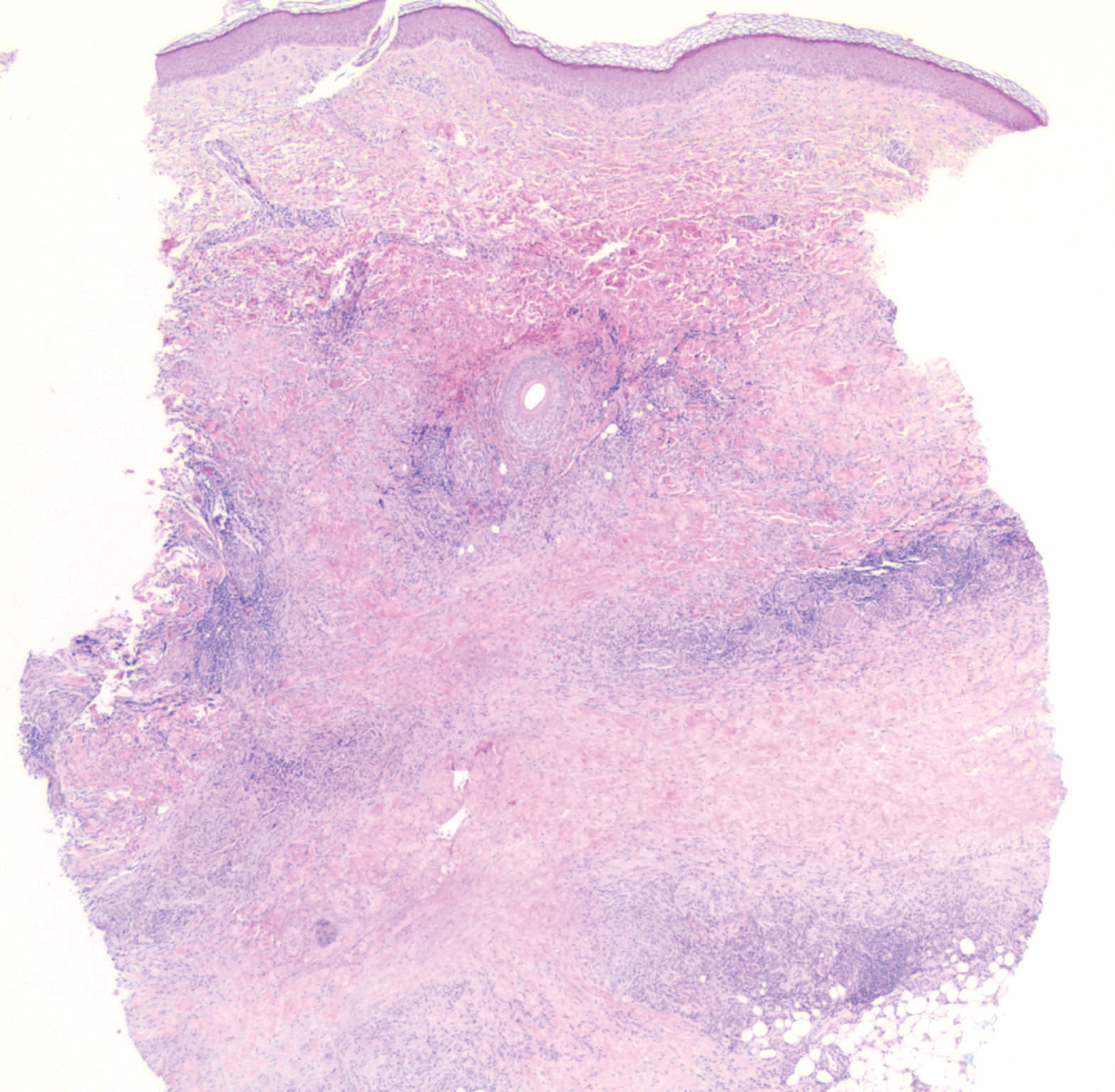

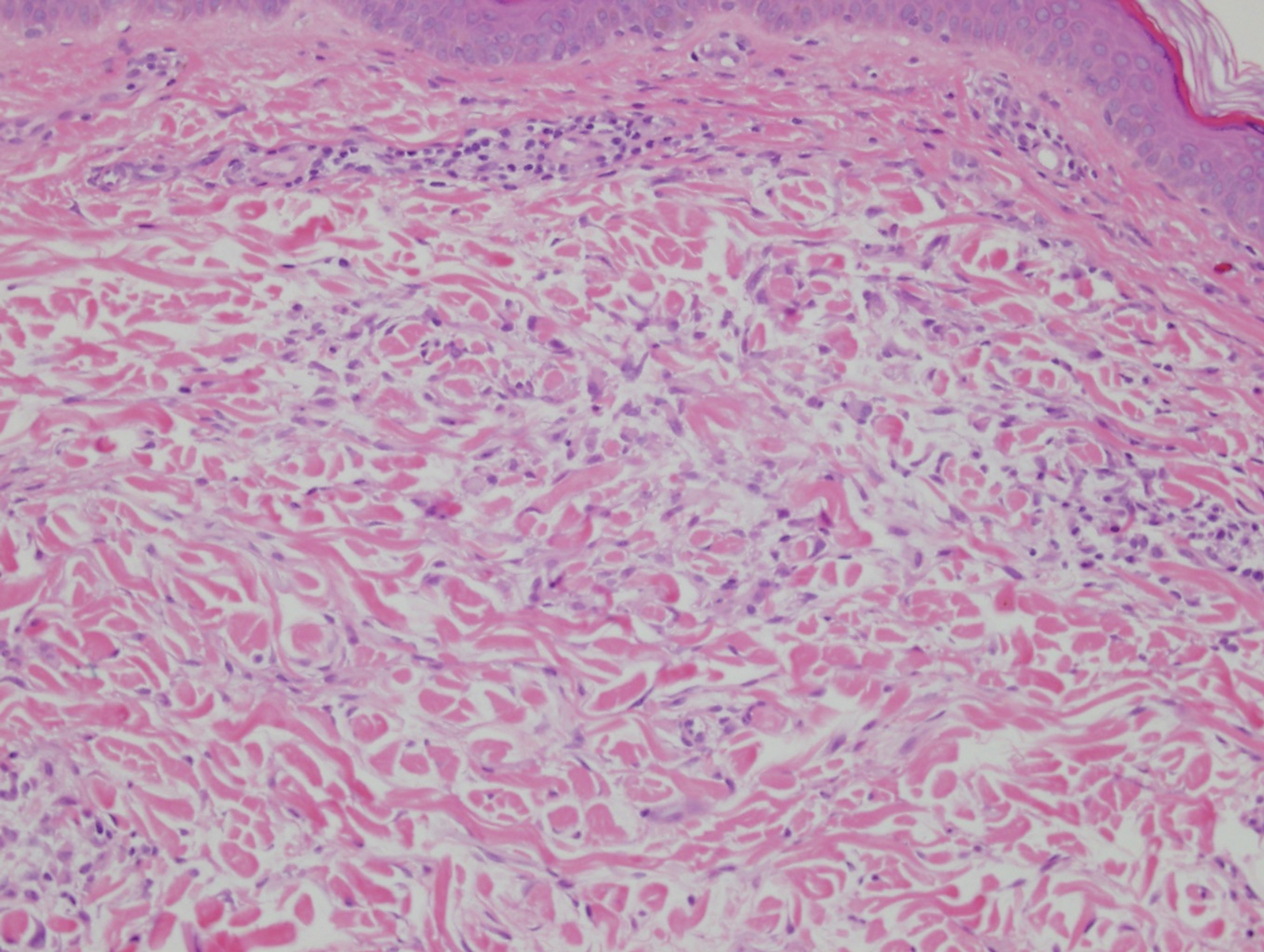

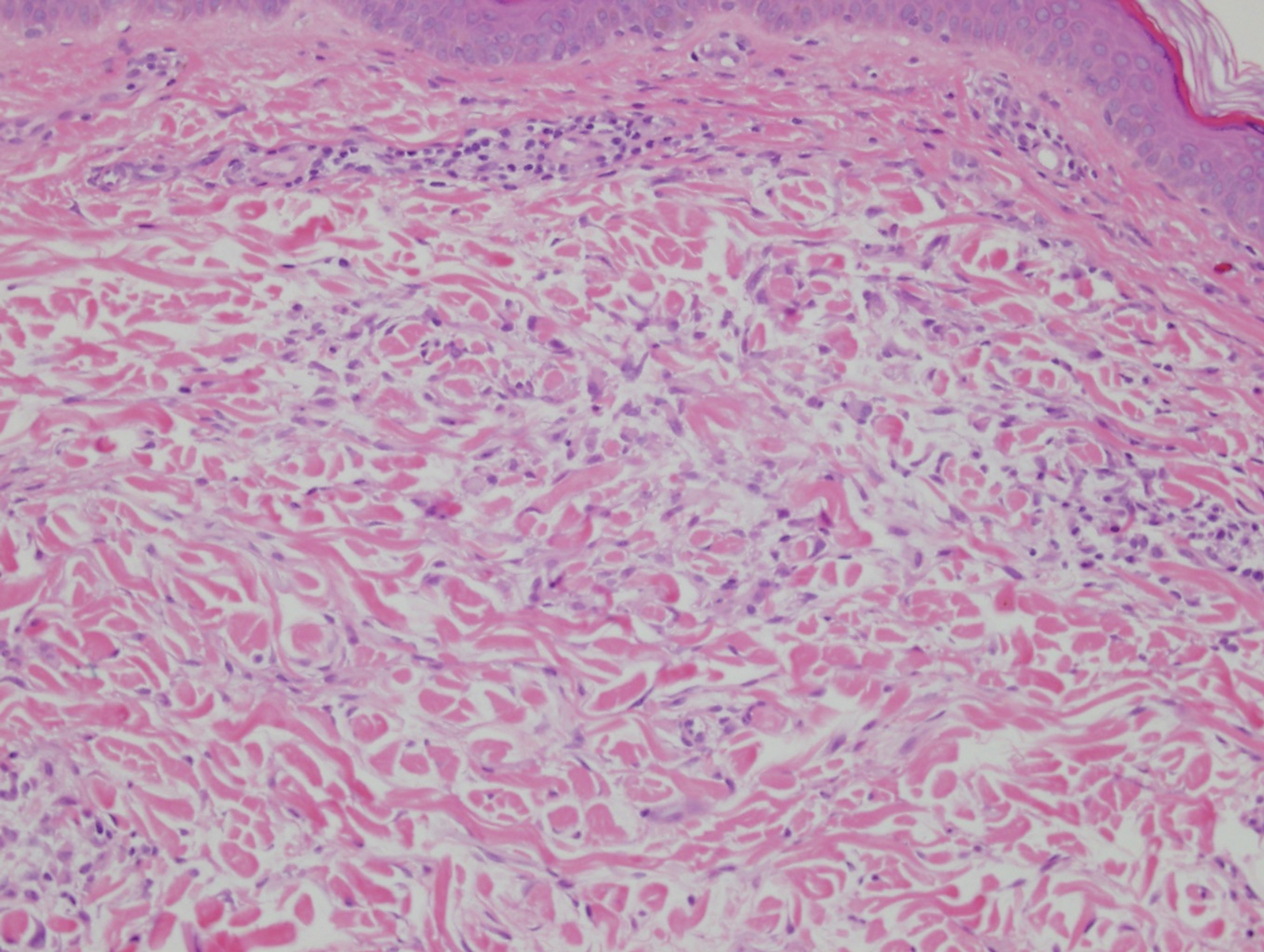

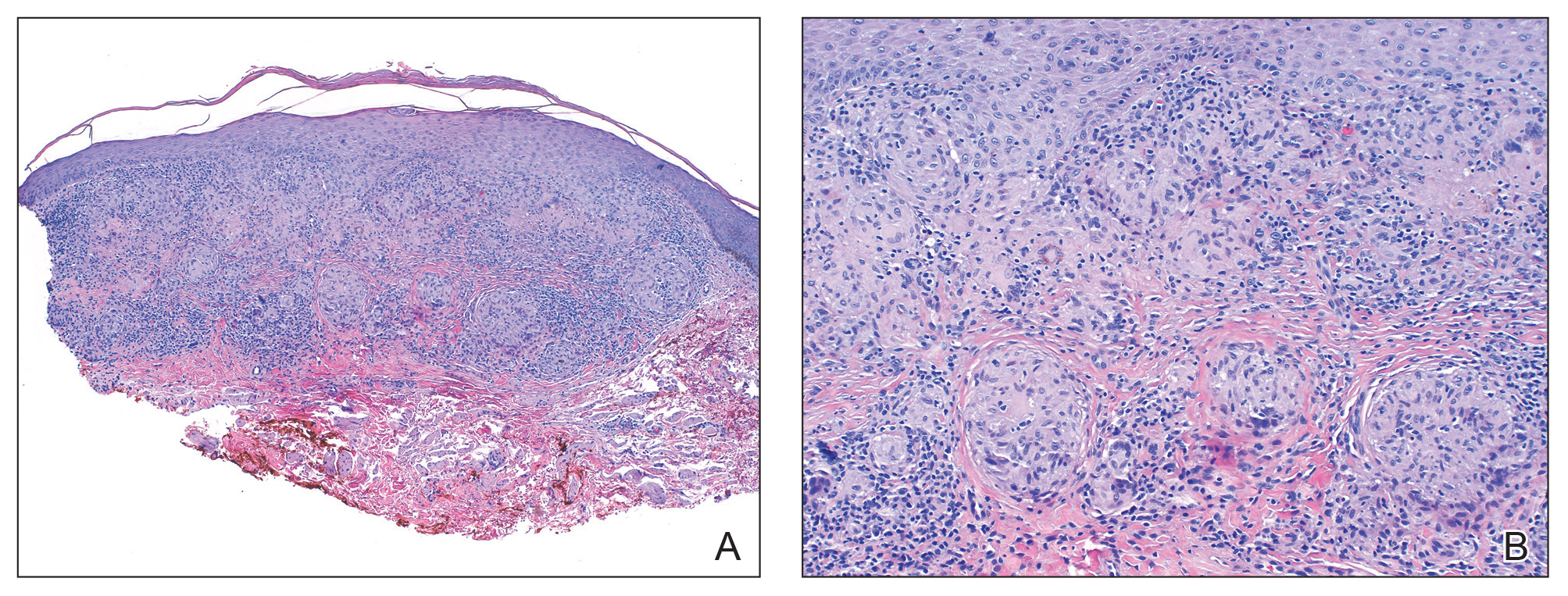

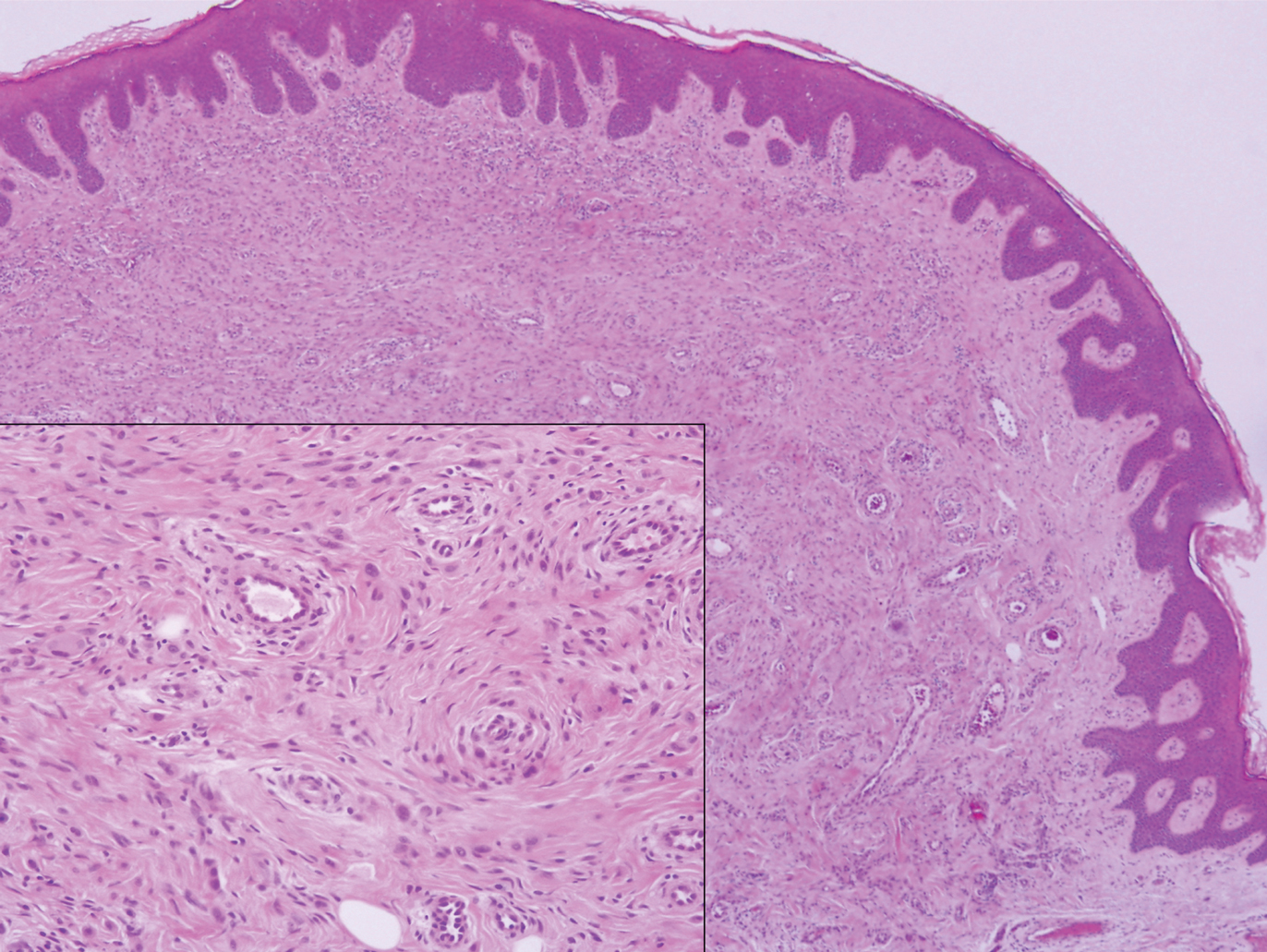

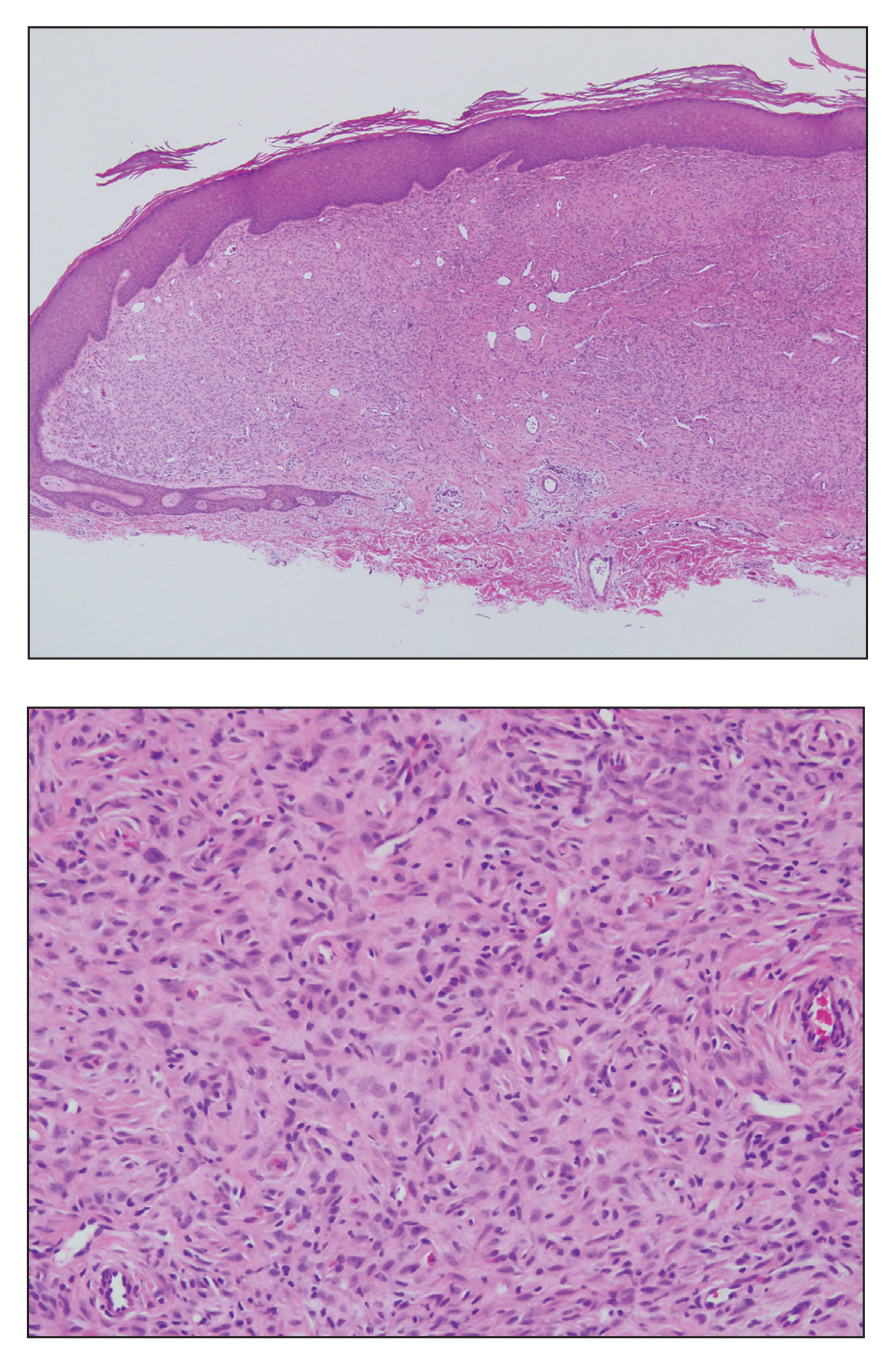

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

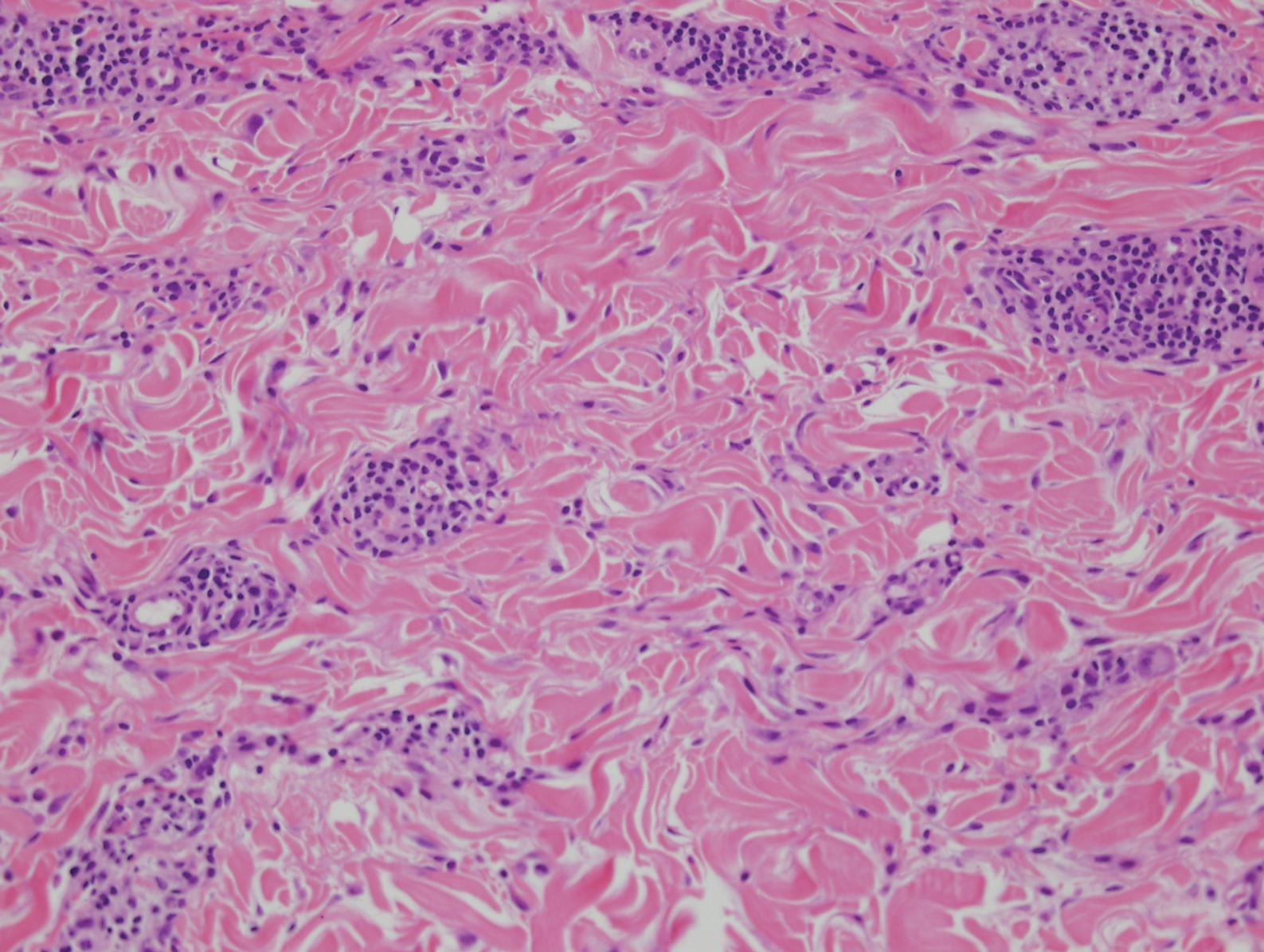

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

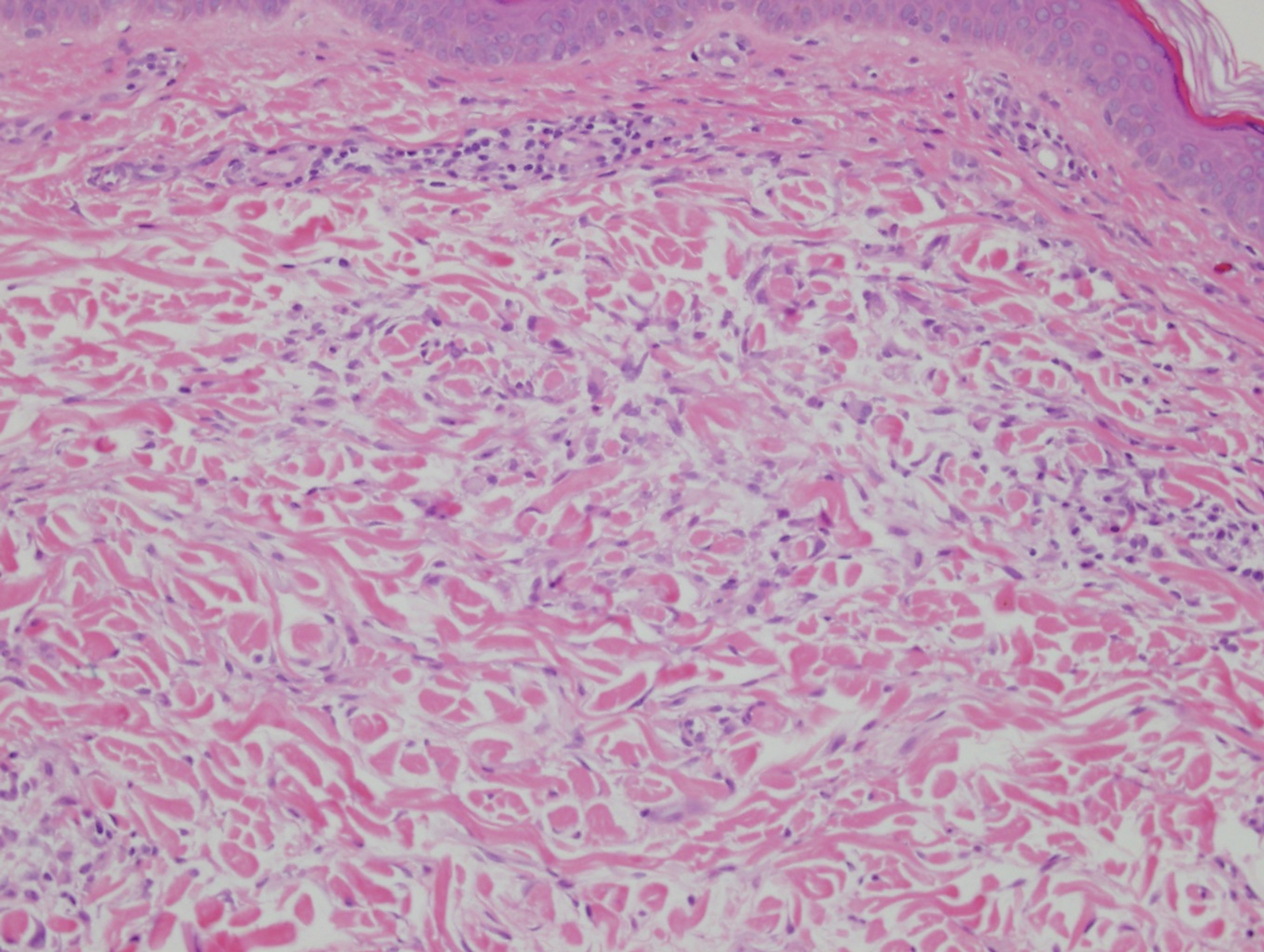

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

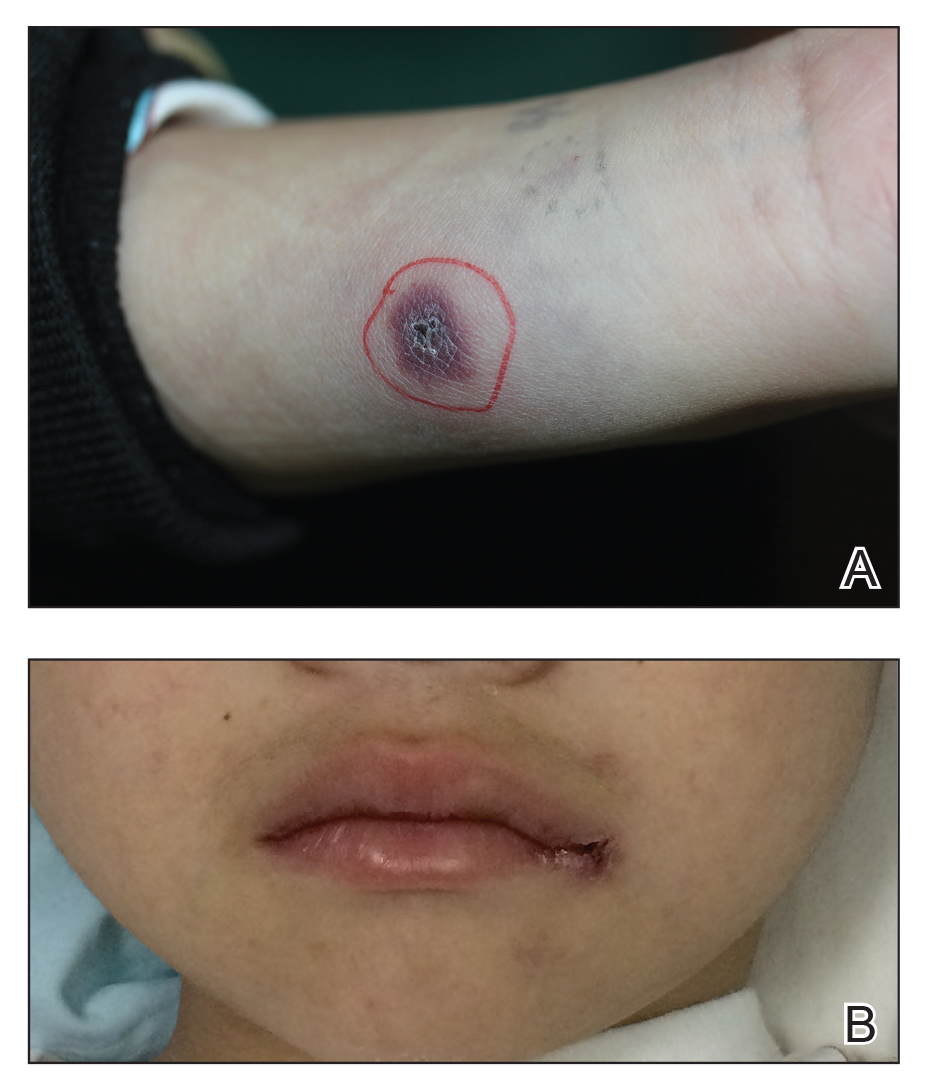

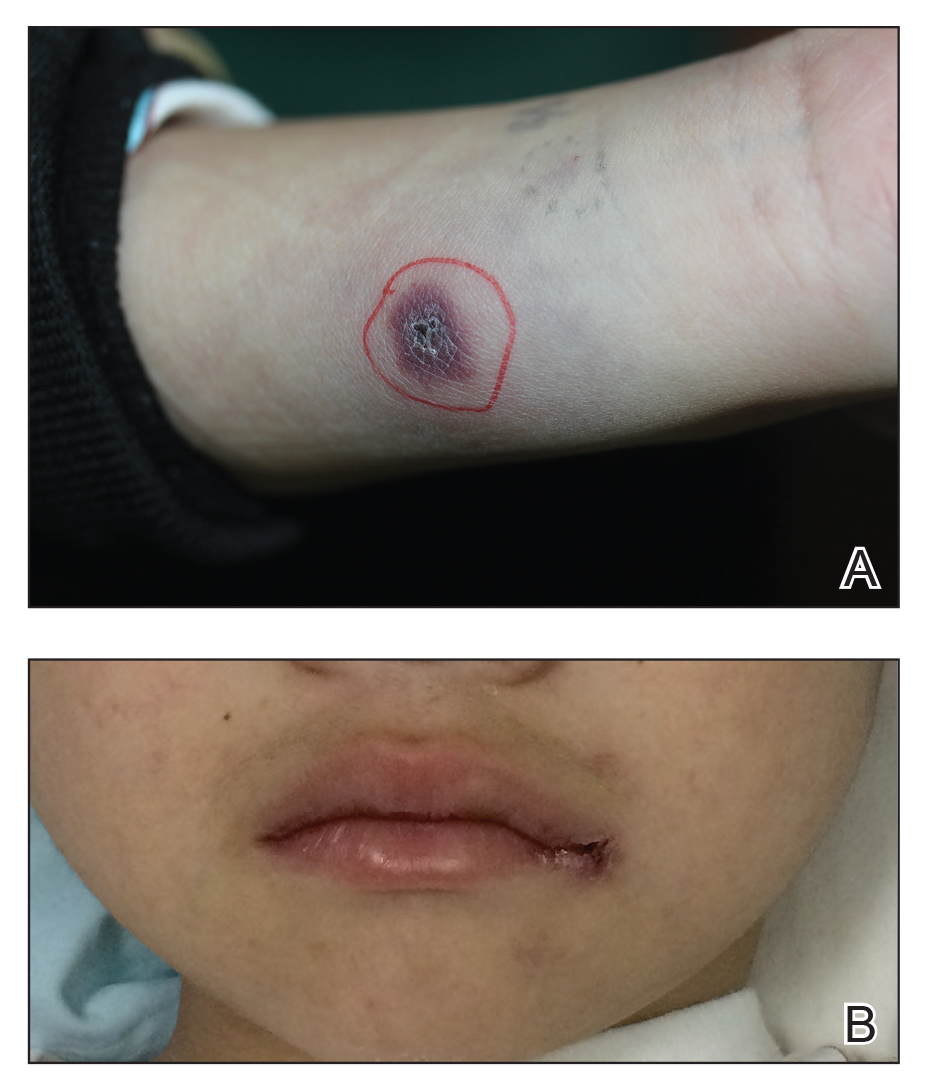

A 58-year-old woman with a medical history of asthma, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and hyperlipidemia presented with a painful rash of 10 days' duration. The rash was associated with fever at home (temperature, 38.5.2 °C), and a review of systems was positive for joint pain. Physical examination revealed numerous 8- to 10-mm, erythematous, discus-shaped papules on the bilateral dorsal hands, bilateral palms, right knee, and right dorsal foot with slight tenderness to palpation. A papule on the right dorsal hand was biopsied.

Kaposi Sarcoma in a Patient With Postpolio Syndrome

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

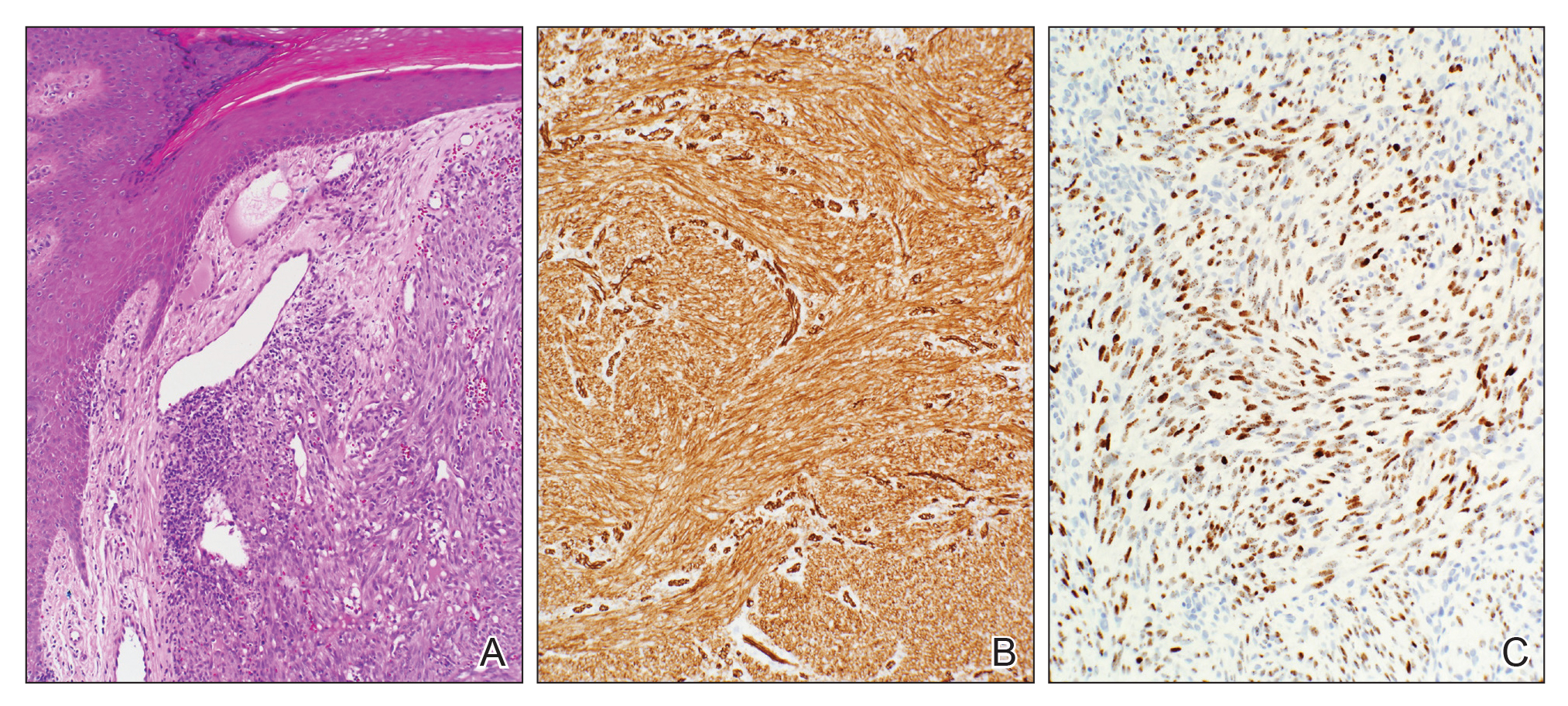

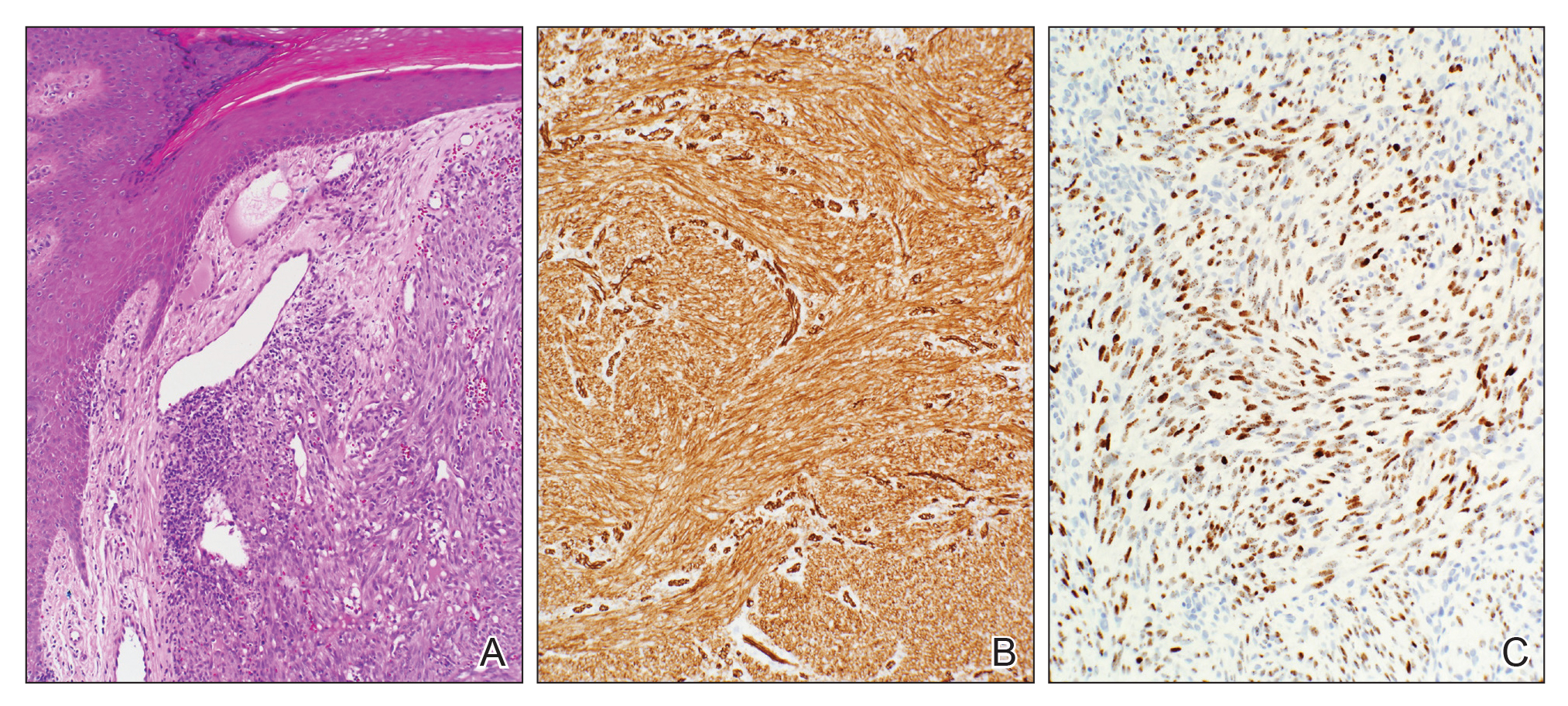

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990.

- Boyer FV, Tiffreau V, Rapin A, et al. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiological hypotheses, diagnosis criteria, drug therapy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:34-41.

- Bruno RL, Johnson JC, Berman WS. Vasomotor abnormalities as post-polio sequelae: functional and clinical implications. Orthopedics. 1985;8:865-869.

- Palmer B, Xia Y, Cho S, Lewis FS. Acroangiodermatitis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2010;86:239-240.

- Rotbart G. Kaposi's disease and venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 1978;31:439-443.

- Que SK, DeFelice T, Abdulla FR, et al. Non-HIV-related kaposi sarcoma in 2 Hispanic patients arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2015;95:E30-E33.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

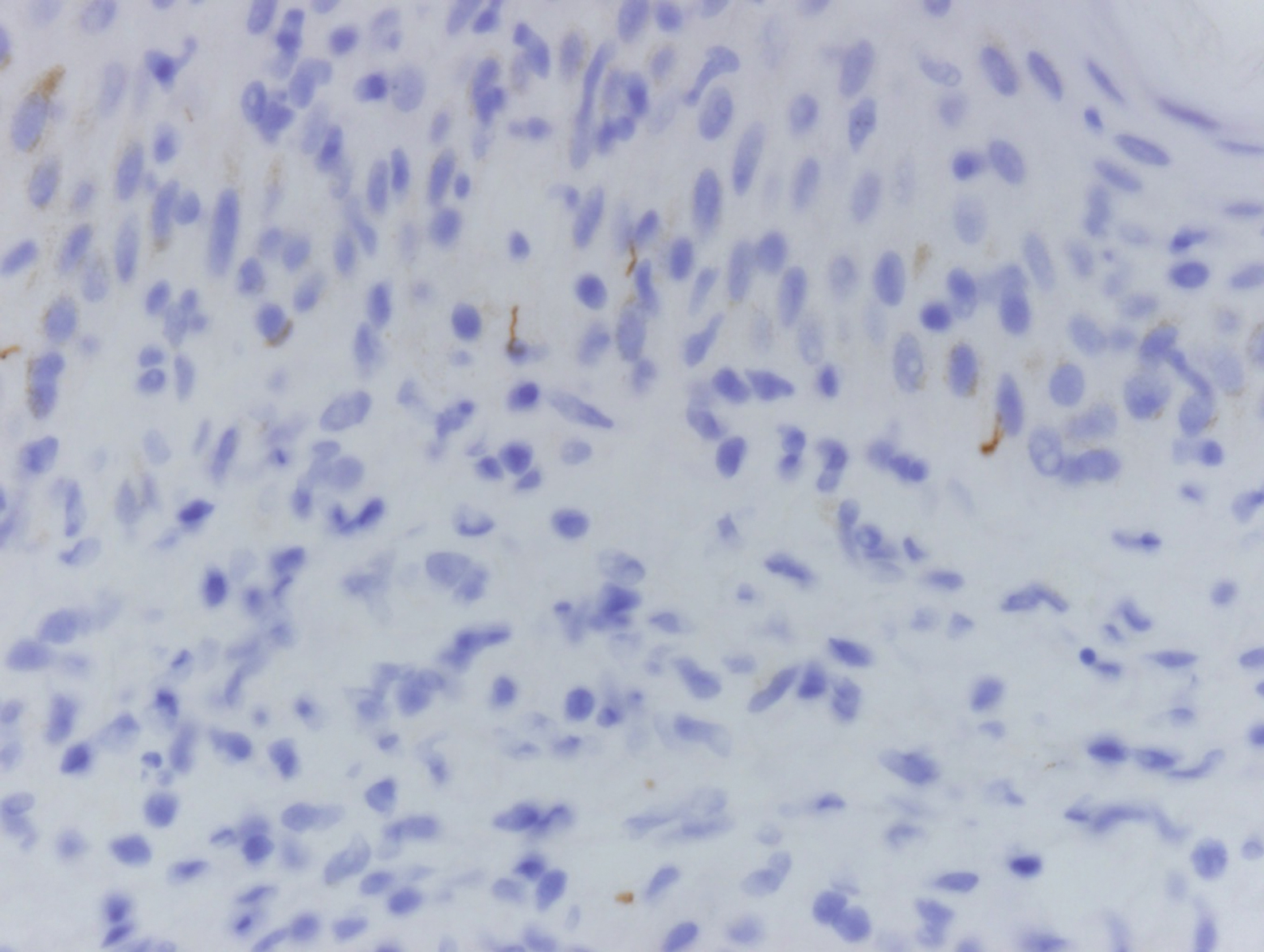

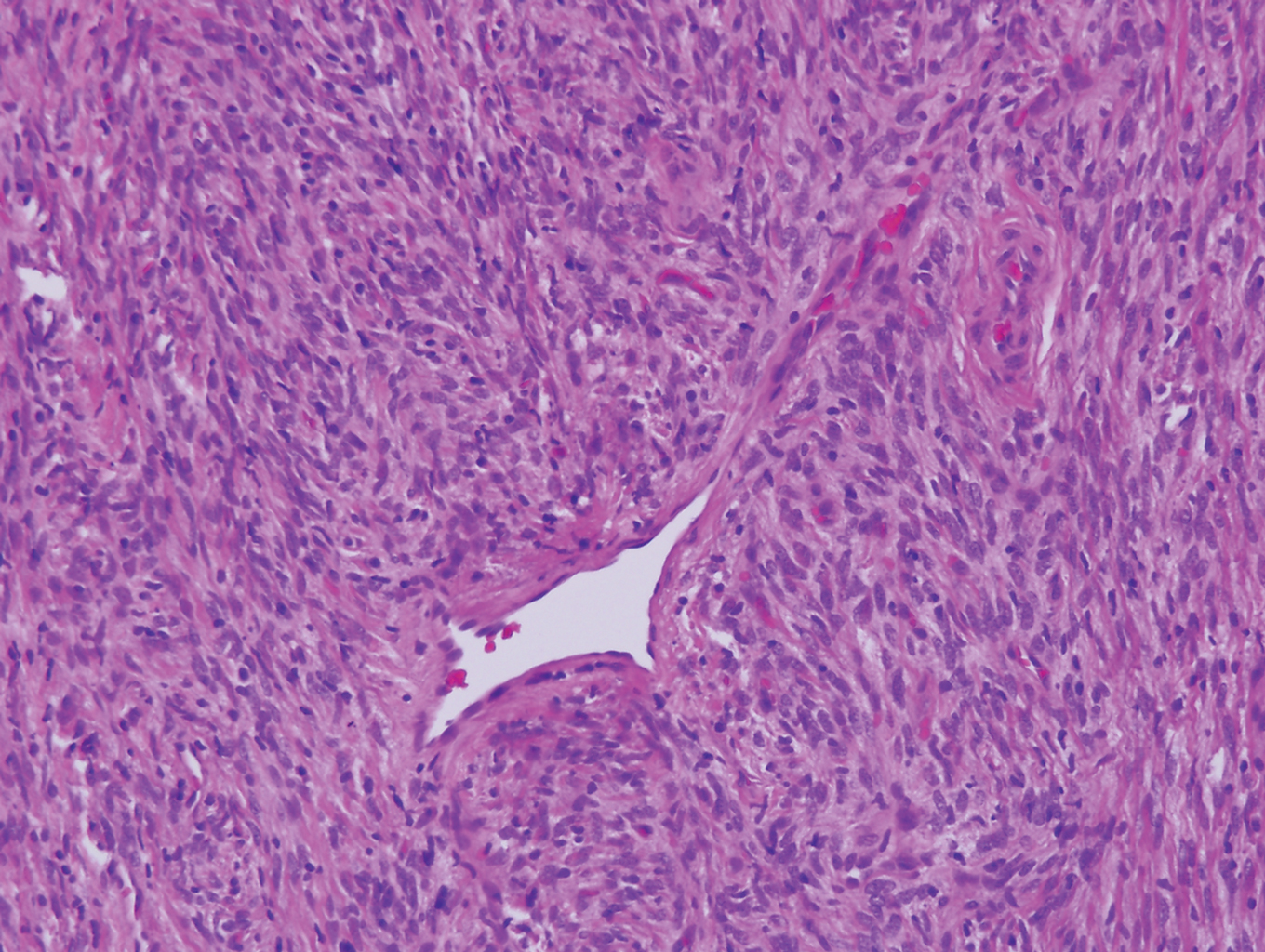

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990.

- Boyer FV, Tiffreau V, Rapin A, et al. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiological hypotheses, diagnosis criteria, drug therapy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:34-41.

- Bruno RL, Johnson JC, Berman WS. Vasomotor abnormalities as post-polio sequelae: functional and clinical implications. Orthopedics. 1985;8:865-869.

- Palmer B, Xia Y, Cho S, Lewis FS. Acroangiodermatitis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2010;86:239-240.

- Rotbart G. Kaposi's disease and venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 1978;31:439-443.

- Que SK, DeFelice T, Abdulla FR, et al. Non-HIV-related kaposi sarcoma in 2 Hispanic patients arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2015;95:E30-E33.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990.

- Boyer FV, Tiffreau V, Rapin A, et al. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiological hypotheses, diagnosis criteria, drug therapy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:34-41.

- Bruno RL, Johnson JC, Berman WS. Vasomotor abnormalities as post-polio sequelae: functional and clinical implications. Orthopedics. 1985;8:865-869.

- Palmer B, Xia Y, Cho S, Lewis FS. Acroangiodermatitis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2010;86:239-240.

- Rotbart G. Kaposi's disease and venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 1978;31:439-443.

- Que SK, DeFelice T, Abdulla FR, et al. Non-HIV-related kaposi sarcoma in 2 Hispanic patients arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2015;95:E30-E33.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a human herpesvirus 8–positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.

- In addition, patients with postpolio syndrome characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

- Kaposi sarcoma is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm, and radiation therapy can achieve local control.

Multiple Facial Papules

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

A 50-year-old man presented with facial papules on the cheeks that had appeared approximately 1.5 years prior and gradually spread over the face and neck. They were occasionally pruritic but otherwise were asymptomatic. His mother and brother reportedly had similar clinical findings. Family history was notable for a maternal uncle who had died in his 30s of an unknown type of renal cancer. Physical examination revealed innumerable white-gray papules that measured 1 to 5 mm and were scattered across the face and neck. Punch biopsies were obtained. Computed tomography of the chest showed multiple bibasilar pulmonary cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging was negative for renal tumors.

Unilateral Papules on the Face

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

An 18-year-old woman presented with a progressive appearance of firm, red-brown, asymptomatic, 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped papules on the right cheek that developed over the course of 2 years. She had 10 lesions that covered a 2.2 ×4-cm area on the right medial cheek. No similar-appearing lesions were detectable on a full-body skin examination, and no periungual tumors, café au lait macules, or shagreen patches were noted. A full-body skin examination using a Wood lamp revealed 1 small hypopigmented macule on the right second finger. The patient had a history of treatment-refractory migraines; magnetic resonance imaging 5 years prior to the current presentation revealed a nonspecific lesion in the left parietal gyrus. There was no personal or family history of seizures, cognitive delay, kidney disease, or ocular disease. Punch biopsy of a facial lesion was performed for histopathologic correlation.

Solitary Papule on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1